Decolonization

Encyclopedia

Decolonization refers to the undoing of colonialism

, the unequal relation of polities

whereby one people or nation establishes and maintains dependent Territory (courial governments) over another. It can be understood politically (attaining independence

, autonomous home rule, union with the metropole

or another state) or culturally (removal of pernicious colonial effects.) The term refers particularly to the dismantlement, in the years after World War II

, of the Neo-Imperial empires

established prior to World War I

throughout Africa

and Asia

.

The United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization has stated that in the process of decolonization there is no alternative to the colonizer's allowance of self-determination

, but in practice decolonization may involve peaceful

or violent resistance by the native population. It may be intramural or involve the intervention of foreign powers acting individually or through international bodies such as the United Nations

. Although examples of decolonization can be found as early as the writings of Thucydides

, there have been several particularly active periods of decolonization in modern times. These are the breakup of the Spanish Empire in the nineteenth century; of the German

, Austro-Hungarian

, Ottoman

, and Russian Empire

s following World War I; of the British

, French

, Dutch, and Italian colonial empires following World War II; of the Russian Empire successor union

following the Cold War

; and others.

, sometimes following a revolution. More often, there is a dynamic cycle where negotiations fail, minor disturbances ensue resulting in suppression by the police and military forces, escalating into more violent revolts that lead to further negotiations until independence is granted. In rare cases, the actions of the native population are characterized by nonviolence

, with the Indian independence movement

led by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi being one of the most notable examples, and the violence comes as active suppression from the occupying forces or as political opposition from forces representing minority local communities who feel threatened by the prospect of independence. For example, there was a war of independence in French Indochina

, while in some countries in French West Africa

(excluding the Maghreb

countries) decolonization resulted from a combination of insurrection and negotiation. The process is only complete when the de facto government of the newly independent country is recognized as the de jure sovereign state

by the community of nations.

Independence is often difficult to achieve without the encouragement and practical support from one or more external parties. The motives for giving such aid are varied: nations of the same ethnic and/or religious stock may sympathize with oppressed groups, or a strong nation may attempt to destabilize a colony as a tactical move to weaken a rival or enemy colonizing power or to create space for its own sphere of influence; examples of this include British support of the Haitian Revolution

against France, and the Monroe Doctrine

of 1823, in which the United States warned the European powers not to interfere in the affairs of the newly independent states of the Western Hemisphere

.

As world opinion became more pro-emancipation following World War I

, there was an institutionalised collective effort to advance the cause of emancipation through the League of Nations

. Under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, a number of mandate

s were created. The expressed intention was to prepare these countries for self-government, but are often interpreted as a mere redistribution of control over the former colonies of the defeated powers, mainly Germany

and the Ottoman Empire

. This reassignment work continued through the United Nations

, with a similar system of trust territories

created to adjust control over both former colonies and mandated territories.

In referendums, some colonized populations have chosen to retain their colonial status, such as Gibraltar

and French Guiana

. There are even examples, such as the Falklands War

, in which an Imperial power goes to war to defend the right of a colony to continue to be a colony. Colonial powers have sometimes promoted decolonization in order to shed the financial, military and other burdens that tend to grow in those colonies where the colonial regimes have become more benign.

Decolonization is rarely achieved through a single historical act, but rather progresses through one or more stages of emancipation, each of which can be offered or fought for: these can include the introduction of elected representatives (advisory or voting; minority or majority or even exclusive), degrees of autonomy or self-rule. Thus, the final phase of decolonisation may in fact concern little more than handing over responsibility for foreign relations and security, and soliciting de jure recognition for the new sovereignty

. But, even following the recognition of statehood, a degree of continuity can be maintained through bilateral treaties between now equal governments involving practicalities such as military training, mutual protection pacts, or even a garrison and/or military bases.

There is some debate over whether or not the Americas

can be considered decolonized, as it was the colonist and their descendants who revolted and declared their independence instead of the indigenous peoples

, as is usually the case. Furthermore, included in this list of states where "decolonization" has not occurred as per the ideas reflected above are Australia, New Zealand.

s in the Balkans

) previously conquered by the Ottoman Empire

were able to achieve independence in the nineteenth century, a process that peaked at the time of the Ottoman defeat in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78.

and its subsequent expulsion in 1801, the commander of an Albanian regiment, Muhammad Ali

, was able to gain control of Egypt

. Although he was acknowledged by the Sultan

in Constantinople

in 1805 as his pasha

, Muhammad Ali was in reality monarch of a practically sovereign state.

occupation. Independence was secured by the intervention of the British and French navies

and the French

and Russian armies

, but Greece was limited to an area including perhaps only one-third of the Turkish Greeks. The war also ended many of the privileges of the Phanariot Greeks of Constantinople

and saw the Great Powers impose a foreign dynasty

over the previously self-proclaimed Hellenic Republic

.

in 1876, the subsequent Russo-Turkish war ended with the provisional Treaty of San Stefano

established a huge new realm of Bulgaria including most of Macedonia

and Thrace. The final 1878 Treaty of Berlin

allowed the other Great Powers to limit the size of the new Russian client state

and even briefly divided this rump state in two, Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia

, but the irredentist

claims from the first treaty would direct Bulgarian claims through the first

and second Balkan War

s and both World Wars.

, Romania was recognized as an independent

state by the Great Powers.

n independence from the Ottoman Empire at the Congress of Berlin

in 1878.

from the Ottoman Empire was recognized at the congress of Berlin

in 1878.

The New Imperialism period, with the scramble for Africa

The New Imperialism period, with the scramble for Africa

and the Opium Wars, marked the zenith of European colonization. It also marked the acceleration of the trends that would end it. The extraordinary material demands of the conflict had spread economic change across the world (notably inflation), and the associated social pressures of "war imperialism" created both peasant unrest and a burgeoning middle class.

Economic growth

created stakeholders with their own demands, while racial issues meant these people clearly stood apart from the colonial middle-class and had to form their own group. The start of mass nationalism

, as a concept and practice, would fatally undermine the ideologies of imperialism.

There were, naturally, other factors, from agrarian change (and disaster – French Indochina

), changes or developments in religion (Buddhism

in Burma, Islam

in the Dutch East Indies

, marginally people like John Chilembwe

in Nyasaland

), and the impact of the depression of the 1930s.

The Great Depression

, despite the concentration of its impact on the industrialized world, was also exceptionally damaging in the rural colonies. Agricultural prices fell much harder and faster than those of industrial goods. From around 1925 until World War II

, the colonies suffered. The colonial powers concentrated on domestic issues, protectionism

and tariffs, disregarding the damage done to international trade flows. The colonies, almost all primary "cash crop

" producers, lost the majority of their export income and were forced away from the "open" complementary colonial economies to "closed" systems. While some areas returned to subsistence farming (British Malaya

) others diversified (India, West Africa

), and some began to industrialise. These economies would not fit the colonial straitjacket when efforts were made to renew the links. Further, the European-owned and -run plantation

s proved more vulnerable to extended deflation

than native capitalist

s, reducing the dominance of "white" farmers in colonial economies and making the European government

s and investors of the 1930s co-opt indigenous

elites — despite the implications for the future.

The efforts at colonial reform also hastened their end — notably the move from non-interventionist collaborative systems towards directed, disruptive, direct management to drive economic change. The creation of genuine bureaucratic government boosted the formation of indigenous bourgeoisie

. This was especially true in the British Empire

, which seemed less capable (or less ruthless) in controlling political nationalism. Driven by pragmatic demands of budgets and manpower the British made deals with the nationalist elites. They dealt with the white dominion

s, retained strategic resources at the cost of reducing direct control in Egypt

, and made numerous reforms in the British Raj

, culminating in the Government of India Act

(1935).

Despite these efforts though, the British Government continued to slowly lose their control of the Raj. The end of World War II allowed India, in addition to various other European colonies, to take advantage of the postwar chaos that had began to exist in Europe during the mid 1940s. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, India's independence movement leader, realized the advantage in conducting a peaceful resistance to the British Empire's attempts to retake control of their "crown jewel". By becoming a symbol of both peace and opposition to British imperialism, many Indian citizens began to view the British as the cause of India's violence leading to a new found sense of nationalism

among its population. With this new wave of Indian nationalism, Gandhi was eventually able to garner the support needed to push back the British and create an independent India in 1947.

Tropical Africa was only fully drawn into the colonial system at the end of the 19th century. Nevertheless, the Union of South Africa

which, by introducing rigid racial segregation

from 1913 was already catalyzing the anti-colonial political agitation of half the continent. While, in the north-east the continued independence of the Empire of Ethiopia remained a beacon of hope. Colonial inequities ranged between extremes, from British Kenya's dispossession of local farmers, to Belgium's massacres in the Congo, from entrenched Portuguese racism to the looting of Benin City. However, with the resistance wars of the 1900s barely over, new modernising forms of African Nationalism began to gain strength in the early 20th-century with the emergence of Pan-Africanism, as advocated by the Jamaican journalist Marcus Garvey

(1887–1940) whose widely distributed newspapers demanded swift abolition of European imperialism, as well as republicanism in Egypt. Kwame Nkrumah

(1909–1972) who was inspired by the works of Garvey led Ghana to independence from colonial rule, while the republican Nasser led Egypt to resist British occupation.

approached imperialism differently from the Great Powers and Japan. Much of its energy and rapidly expanding population was directed westward across the North America

n continent against American Indians

, Spain

, and Mexico

. With eventual assistance from the British Navy, its Monroe Doctrine

reserved the Americas as its sphere of interest, prohibiting other states (particularly Spain) from recolonizing the recently freed polities of Latin America

. Economic and political pressure, as well as assaults by filibusters

, were brought to bear, but Northern fears of the expansion of slavery into new territories restrained the United States from early expansion into Cuba

or Central America

. America's only African colony, Liberia

, was formed privately and achieved independence early. While the United States had few qualms about opening the markets of Japan, Korea, and China

by military force, it advocated an Open Door Policy

and opposed the direct division and colonization of those states.

Following the Civil War

and particularly during and after the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt

, direct intervention in Latin America and elsewhere expanded. The United States purchased Russian America from the tsar and accepted the offer of Hawaii

from rebel expatriates and seized several colonies from Spain

in 1898. Barred from annexing Cuba

outright by the Teller Amendment

, the U.S. established it as a client state

with obligations including the perpetual lease of Guantánamo Bay to the U.S. Navy. The attempt of the first governor to void the island's constitution and remain in power past the end of his term provoked a rebellion that provoked a reoccupation between 1906 and 1909, but this was again followed by devolution. Similarly, the McKinley administration, despite prosecuting the Philippine–American War against a native republic, set out that the Territory of the Philippine Islands was eventually granted independence.

Britain's 1895 attempt to reject the Monroe Doctrine during the Venezuela Crisis of 1895

, the Venezuela Crisis of 1902–1903

, and the establishment of the client state of Panama

in 1903 via gunboat diplomacy

, however, all necessitated the maintenance of Puerto Rico

as a naval base to secure shipping lanes to the Caribbean and the new canal zone

. In 1917, "Puerto Ricans were collectively made U.S. citizens" via the Jones Act

, and in 1952 the US Congress turned the territory into a commonwealth after ratifying the Constitution

born out of United States Public Law 600. The US government then declared the territory was no longer a colony and stopped transmitting information about Puerto Rico to the United Nations Decolonization Committee. As a result, the UN General Assembly removed Puerto Rico from the U.N. list of non-self-governing territories

. Dissatisfied with their new political status, Puerto Ricans turned to political referendums to let make their opinions known. Several internal plebiscites, non-binding upon the United States, proposing statehood

or independence for the island did not garnish a majority in 1967, 1993, and 1998. As a result of the UN not applying the full set of criteria which was enunciated in 1960 when it took favorable note of the cessation of transmission of information regarding the non-self-governing status of Puerto Rico, the nature of Puerto Rico's relationship with the U.S. continues to be the subject of ongoing debate in Puerto Rican politics, the United States Congress

, and the United Nations

.

The Monroe Doctrine received the Roosevelt Corollary

in 1904, providing that the United States had a right and obligation to intervene "in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence" that a nation in the Western Hemisphere became vulnerable to European control. In practice, this meant that the United States was led to act as a collections agent for European creditors by administering customs duties in the Dominican Republic

(1905–1941), Haiti

(1915–1934), and elsewhere. The intrusiveness and bad relations this engendered were somewhat checked by the Clark Memorandum

and renounced by President Franklin D. Roosevelt

's "Good Neighbor Policy

." The end of World War II saw America producing 46% of the world's GDP, but pouring billions of dollars into the Marshall Plan

and restoring independent (if anti-Communist) democracies in Japan

and West Germany

. The post-war period also saw America push hard to accelerate decolonialization and bring an end to the colonial empires of its Western allies, most importantly during the 1956 Suez Crisis

, but American military bases were established around the world and direct and indirect interventions continued in Korea

, Indochina

, Latin America (inter alia, the 1965 occupation of the Dominican Republic,) Africa, and the Middle East to oppose Communist invasions and insurgencies. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the United States has been far less active in the Americas, but invaded Afghanistan

and Iraq following the September 11 attacks in 2001, establishing army and air bases in Central Asia

.

and Korea

. Pursuing a colonial policy comparable to those of European powers, Japan settled significant populations of ethnic Japanese in its colonies while simultaneously suppressing indigenous ethnic populations by enforcing the learning and use of the Japanese language

in schools. Other methods such as public interaction, and attempts to eradicate the use of Korean

, Hokkien, and Hakka among the indigenous peoples, were seen to be used.

Japan also set up the Imperial university

in Korea (Keijo Imperial University

) and Taiwan (Taihoku University) to compel education.

World War II gave the Japanese Empire occasion to conquer vast swaths of Asia, sweeping into China

and seizing the Western colonies of Vietnam

, Hong Kong

, the Philippines

, Burma, Malaya

, Timor

and Indonesia

among others, albeit only for the duration of the war. An estimated 20 million Chinese died during the Second Sino-Japanese War

(1931–1945). Following its surrender to the Allies

in 1945, Japan was deprived of all its colonies. Japan further claims that the southern Kuril Islands

are a small portion of its own national territory, colonized by the Soviet Union

.

the Great Mosque of Paris was constructed as recognition of these efforts, the French state had no intention to allow self-rule, let alone grant independence

to the colonized people. Thus, nationalism

in the colonies became stronger in between the two wars, leading to Abd el-Krim's Rif War

(1921–1925) in Morocco

and to the creation of Messali Hadj

's Star of North Africa in Algeria

in 1925. However, these movements would gain full potential only after World War II. The October 27, 1946 Constitution creating the Fourth Republic

substituted the French Union

to the colonial empire. On the night of March 29, 1947, a nationalist uprising in Madagascar

led the French government headed by Paul Ramadier

(Socialist

) to violent repression: one year of bitter fighting, in which 90,000 to 100,000 Malagasy died. On May 8, 1945, the Sétif massacre

took place in Algeria.

In 1946, the states of French Indochina

withdrew from the Union, leading to the Indochina War

(1946–54) against Ho Chi Minh

, who had been a co-founder of the French Communist Party

in 1920 and had founded the Vietminh in 1941. In 1956, Morocco and Tunisia

gained their independence, while the Algerian War

was raging (1954–1962). Similarly, a decade earlier, Laos

and Cambodia

achieved independence in order for the French to focus to keeping Vietnam

. With Charles de Gaulle

's return to power in 1958 amidst turmoil and threats of a right-wing coups d'état to protect "French Algeria", the decolonization was completed with the independence of Sub-Saharan Africa's colonies in 1960 and the March 19, 1962 Evian Accords

, which put an end to the Algerian war. The OAS

movement unsuccessfully tried to block the accords with a series of bombings, including an attempted assassination against Charles de Gaulle.

To this day, the Algerian war — officially called until the 1990s a "public order operation" — remains a trauma for both France and Algeria. Philosopher Paul Ricœur has spoken of the necessity of a "decolonization of memory", starting with the recognition of the 1961 Paris massacre during the Algerian war and the recognition of the decisive role of African and especially North African immigrant manpower in the Trente Glorieuses

post–World War II economic growth period. In the 1960s, due to economic needs for post-war reconstruction and rapid economic growth, French employers actively sought to recruit manpower from the colonies, explaining today's multiethnic population

.

under the influence of the Soviet Union, either by direct subversion of Western-leaning or -controlled governments or indirectly by influence of political leadership and support. Many of the revolutions of this time period were inspired or influenced in this way. The conflicts in Vietnam

, Nicaragua

, Congo

, and Sudan

, among others, have been characterized as such.

Most Soviet leaders expressed the Marxist-Leninist

view that imperialism

was the height of capitalism

, and generated a class-stratified society. It followed, then, that Soviet leadership would encourage independence movements in colonized territories, especially as the Cold War

progressed. Though this was the view expressed by their leaders, such interventions can be interpreted as the expansion of Soviet interests, not just as aiding the oppressed peoples of the world. Because so many of these wars of independence expanded into general Cold War conflicts, the United States also supported several such independence movements in opposition to Soviet interests.

Nikita Khrushchev

's famous shoe-banging incident

occurred in the context of a United Nations

debate on colonialism in 1960. After Khrushchev had decried western colonialism, Filipino delegate Lorenzo Sumulong

accused him of hypocrisy, claiming that the Soviet Union was at that time doing exactly the same thing to the countries of Eastern Europe

. Khrushchev then reportedly became enraged and theatrically banged his shoe on the table while berating Sumulong as a "toady of imperialism," though accounts of the incident differ.

During the Vietnam War, Communist countries supported anti-colonialist movements in various countries still under colonial administration through propaganda, developmental and economic assistance, and in some cases military aid. Notably among these were the support of armed rebel movements by Cuba

in Angola

, and the Soviet Union (as well as the People's Republic of China

) in Vietnam

.

The term "Third World

The term "Third World

" was coined by French demographer Alfred Sauvy

in 1952, on the model of the Third Estate, which, according to the Abbé Sieyès

, represented everything, but was nothing: "...because at the end this ignored, exploited, scorned Third World like the Third Estate, wants to become something too" (Sauvy). The emergence of this new political entity, in the frame of the Cold War

, was complex and painful. Several tentatives were made to organize newly independent states in order to oppose a common front towards both the US's and the USSR's influence on them, with the consequences of the Sino-Soviet split

already at works. Thus, the Non-Aligned Movement

constituted itself, around the main figures of Jawaharlal Nehru

, the leader of India, Sukarno

, the Indonesia

n president, Josip Broz Tito

the Communist leader of Yugoslavia

, and Gamal Abdel Nasser

, head of Egypt

who successfully opposed the French and British imperial powers during the 1956 Suez crisis

. After the 1954 Geneva Conference

which put an end to the French war against Ho Chi Minh

in Vietnam

, the 1955 Bandung Conference gathered Nasser, Nehru, Tito, Sukarno

, the leader of Indonesia

, and Zhou Enlai

, Premier of the People's Republic of China

. In 1960, the UN General Assembly voted the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples

. The next year, the Non-Aligned Movement was officially created in Belgrade

(1961), and was followed in 1964 by the creation of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development

(UNCTAD) which tried to promote a New International Economic Order

(NIEO). The NIEO was opposed to the 1944 Bretton Woods system

, which had benefited the leading states which had created it, and remained in force until 1971 after the United States' suspension of convertibility from dollars to gold. The main tenets of the NIEO were:

The UNCTAD however wasn't very effective in implementing this New International Economic Order (NIEO), and social and economic inequalities between industrialized countries and the Third World kept on growing through-out the 1960s until the 21st century. The 1973 oil crisis

The UNCTAD however wasn't very effective in implementing this New International Economic Order (NIEO), and social and economic inequalities between industrialized countries and the Third World kept on growing through-out the 1960s until the 21st century. The 1973 oil crisis

which followed the Yom Kippur War

(October 1973) was triggered by the OPEC which decided an embargo against the US and Western countries, causing a fourfold increase in the price of oil, which lasted five months, starting on October 17, 1973, and ending on March 18, 1974. OPEC nations then agreed, on January 7, 1975, to raise crude oil prices by 10%. At that time, OPEC nations — including many who had recently nationalised their oil industries — joined the call for a New International Economic Order to be initiated by coalitions of primary producers. Concluding the First OPEC Summit in Algiers they called for stable and just commodity prices, an international food and agriculture program, technology transfer from North to South, and the democratization of the economic system. But industrialized countries quickly began to look for substitutes to OPEC petroleum, with the oil companies investing the majority of their research capital in the US and European countries or others, politically sure countries. The OPEC lost more and more influence on the world prices of oil.

The second oil crisis

occurred in the wake of the 1979 Iranian Revolution

. Then, the 1982 Latin American debt crisis

exploded in Mexico

first, then Argentina

and Brazil

, which proved unable to pay back their debts, jeopardizing the existence of the international economic system.

The 1990s were characterized by the prevalence of the Washington consensus

on neoliberal

policies, "structural adjustment

" and "shock therapies

" for the former Communist states.

Though the term "decolonization" is not well received among donors in international development

today, the root of the emerging emphasis on projects to promote "democracy, governance and human rights" by international donors and to promote "institution building" and a "human rights based approach

" to development is the same concept to achieve decolonization.

Weak Parliaments and Ministerial governments (where Ministries issue their own edicts and write laws rather than the Parliament) are holdovers of colonialism since political decisions were made outside the country, Parliament were at most for show, and the executive branch (then, foreign Governor Generals and foreign civil servants) held local power. Similarly, militaries are strong and civil control over them is weak; a holdover of military control exercised by a foreign military. In some cases, the governing systems in post-colonial countries could be viewed as ruling elites who succeeded in coup d'etats against the foreign colonial regime but never gave up the system of control.

Often the impact of colonialism is more subtle, with preferences for clothes (such as "blue" shirts of French officials and pith helmets), drugs (alcohol and tobacco that colonial governments introduced, often as a way to tax locals) and other cultural attributes remain.

Some experts in development, such as David Lempert, have suggested an opening of dialogues from the colonial powers on the systems they introduced and the harms that continue as a way of decolonizing in rights policy documents for the UN system and for Europe. First World countries often seem reluctant to engage in this form of decolonization, however, since they may benefit from the legacies of colonialism that they created, in contemporary trade and political relations.

Many of these assassinations are still unsolved cases as of 2010, but foreign power interference is undeniable in many of these cases — although others were for internal matters. To take only one case, the investigation concerning Mehdi Ben Barka is continuing to this day, and both France and the United States have refused to declassify files they acknowledge having in their possession The Phoenix Program

, a CIA program of assassination

during the Vietnam War

, should also be named.

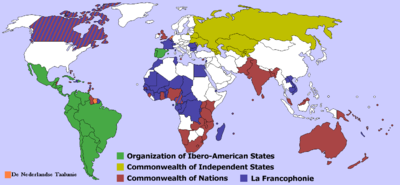

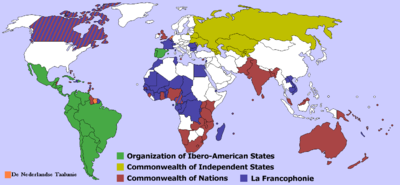

Due to a common history and culture, former colonial powers created institutions which more loosely associated their former colonies. Membership is voluntary, and in some cases can be revoked if a member state loses some objective criteria (usually a requirement for democratic governance). The organizations serve cultural, economic, and political purposes between the associated countries, although no such organization has become politically prominent as an entity in its own right.

Due to a common history and culture, former colonial powers created institutions which more loosely associated their former colonies. Membership is voluntary, and in some cases can be revoked if a member state loses some objective criteria (usually a requirement for democratic governance). The organizations serve cultural, economic, and political purposes between the associated countries, although no such organization has become politically prominent as an entity in its own right.

argues that the post–World War II decolonization was brought about for economic reasons. In A Journey Through Economic Time, he writes, "The engine of economic well-being was now within and between the advanced industrial countries. Domestic economic growth

— as now measured and much discussed — came to be seen as far more important than the erstwhile colonial trade.... The economic effect in the United States

from the granting of independence to the Philippines

was unnoticeable, partly due to the Bell Trade Act

, which allowed American monopoly in the economy of the Philippines. The departure of India and Pakistan made small economic difference in the United Kingdom

. Dutch

economists calculated that the economic effect from the loss of the great Dutch empire in Indonesia

was compensated for by a couple of years or so of domestic post-war economic growth. The end of the colonial era is celebrated in the history books as a triumph of national aspiration in the former colonies and of benign good sense on the part of the colonial powers. Lurking beneath, as so often happens, was a strong current of economic interest — or in this case, disinterest."

In general, the release of the colonized caused little economic loss to the colonizers. Part of the reason for this was that major costs were eliminated while major benefits were obtained by alternate means. Decolonization allowed the colonizer to disclaim responsibility for the colonized. The colonizer no longer had the burden of obligation, financial or otherwise, to their colony. However, the colonizer continued to be able to obtain cheap goods and labor as well as economic benefits (see Suez Canal Crisis) from the former colonies. Financial, political and military pressure could still be used to achieve goals desired by the colonizer. Thus decolonization allowed the goals of colonization to be largely achieved, but without its burdens.

by France was particularly uneasy due to the large European and Sephardic Jewish population (see also pied noir), which largely evacuated to France when Algeria became independent. In Zimbabwe

, former Rhodesia

, president Robert Mugabe

has, starting in the 1990s, targeted white farmers and forcibly seized their property. In some cases, decolonisation is hardly possible or impossible because of the importance of the settler population or where the indigenous population is now in the minority; such is the case of the British population of the Cayman Islands

, the Russian population of Kazakhstan

, and the immigrant communities of the Americas.

Furthermore, note that some cases have been included that were not strictly colonized but rather protectorate, co-dominium, lease.... Changes subsequent to decolonization are usually not included; nor is the dissolution of the Soviet Union

.

Colonialism

Colonialism is the establishment, maintenance, acquisition and expansion of colonies in one territory by people from another territory. It is a process whereby the metropole claims sovereignty over the colony and the social structure, government, and economics of the colony are changed by...

, the unequal relation of polities

Polity

Polity is a form of government Aristotle developed in his search for a government that could be most easily incorporated and used by the largest amount of people groups, or states...

whereby one people or nation establishes and maintains dependent Territory (courial governments) over another. It can be understood politically (attaining independence

Independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state in which its residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory....

, autonomous home rule, union with the metropole

Metropole

The metropole, from the Greek Metropolis 'mother city' was the name given to the British metropolitan centre of the British Empire, i.e. the United Kingdom itself...

or another state) or culturally (removal of pernicious colonial effects.) The term refers particularly to the dismantlement, in the years after World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, of the Neo-Imperial empires

New Imperialism

New Imperialism refers to the colonial expansion adopted by Europe's powers and, later, Japan and the United States, during the 19th and early 20th centuries; expansion took place from the French conquest of Algeria until World War I: approximately 1830 to 1914...

established prior to World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

throughout Africa

Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also known as the Race for Africa or Partition of Africa was a process of invasion, occupation, colonization and annexation of African territory by European powers during the New Imperialism period, between 1881 and World War I in 1914...

and Asia

Imperialism in Asia

Imperialism in Asia traces its roots back to the late 15th century with a series of voyages that sought a sea passage to India in the hope of establishing direct trade between Europe and Asia in spices. Before 1500 European economies were largely self-sufficient, only supplemented by minor trade...

.

The United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization has stated that in the process of decolonization there is no alternative to the colonizer's allowance of self-determination

Self-determination

Self-determination is the principle in international law that nations have the right to freely choose their sovereignty and international political status with no external compulsion or external interference...

, but in practice decolonization may involve peaceful

Nonviolent revolution

A nonviolent revolution is a revolution using mostly campaigns of civil resistance, including various forms of nonviolent protest, to bring about the departure of governments seen as entrenched and authoritarian...

or violent resistance by the native population. It may be intramural or involve the intervention of foreign powers acting individually or through international bodies such as the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

. Although examples of decolonization can be found as early as the writings of Thucydides

Thucydides

Thucydides was a Greek historian and author from Alimos. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC...

, there have been several particularly active periods of decolonization in modern times. These are the breakup of the Spanish Empire in the nineteenth century; of the German

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

, Austro-Hungarian

Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary , more formally known as the Kingdoms and Lands Represented in the Imperial Council and the Lands of the Holy Hungarian Crown of Saint Stephen, was a constitutional monarchic union between the crowns of the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary in...

, Ottoman

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

, and Russian Empire

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

s following World War I; of the British

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

, French

French colonial empire

The French colonial empire was the set of territories outside Europe that were under French rule primarily from the 17th century to the late 1960s. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the colonial empire of France was the second-largest in the world behind the British Empire. The French colonial empire...

, Dutch, and Italian colonial empires following World War II; of the Russian Empire successor union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

following the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

; and others.

Methods and stages

Decolonization is a political process, frequently involving violence. In extreme circumstances, there is a war of independenceWar of Independence

A war of independence is a conflict occurring over a territory that has declared independence. Once the state that previously held the territory sends in military forces to assert its sovereignty or the native population clashes with the former occupier, a separatist rebellion has begun...

, sometimes following a revolution. More often, there is a dynamic cycle where negotiations fail, minor disturbances ensue resulting in suppression by the police and military forces, escalating into more violent revolts that lead to further negotiations until independence is granted. In rare cases, the actions of the native population are characterized by nonviolence

Nonviolence

Nonviolence has two meanings. It can refer, first, to a general philosophy of abstention from violence because of moral or religious principle It can refer to the behaviour of people using nonviolent action Nonviolence has two (closely related) meanings. (1) It can refer, first, to a general...

, with the Indian independence movement

Indian independence movement

The term Indian independence movement encompasses a wide area of political organisations, philosophies, and movements which had the common aim of ending first British East India Company rule, and then British imperial authority, in parts of South Asia...

led by Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi being one of the most notable examples, and the violence comes as active suppression from the occupying forces or as political opposition from forces representing minority local communities who feel threatened by the prospect of independence. For example, there was a war of independence in French Indochina

French Indochina

French Indochina was part of the French colonial empire in southeast Asia. A federation of the three Vietnamese regions, Tonkin , Annam , and Cochinchina , as well as Cambodia, was formed in 1887....

, while in some countries in French West Africa

French West Africa

French West Africa was a federation of eight French colonial territories in Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan , French Guinea , Côte d'Ivoire , Upper Volta , Dahomey and Niger...

(excluding the Maghreb

Maghreb

The Maghreb is the region of Northwest Africa, west of Egypt. It includes five countries: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Mauritania and the disputed territory of Western Sahara...

countries) decolonization resulted from a combination of insurrection and negotiation. The process is only complete when the de facto government of the newly independent country is recognized as the de jure sovereign state

Sovereign state

A sovereign state, or simply, state, is a state with a defined territory on which it exercises internal and external sovereignty, a permanent population, a government, and the capacity to enter into relations with other sovereign states. It is also normally understood to be a state which is neither...

by the community of nations.

Independence is often difficult to achieve without the encouragement and practical support from one or more external parties. The motives for giving such aid are varied: nations of the same ethnic and/or religious stock may sympathize with oppressed groups, or a strong nation may attempt to destabilize a colony as a tactical move to weaken a rival or enemy colonizing power or to create space for its own sphere of influence; examples of this include British support of the Haitian Revolution

Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution was a period of conflict in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, which culminated in the elimination of slavery there and the founding of the Haitian republic...

against France, and the Monroe Doctrine

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a policy of the United States introduced on December 2, 1823. It stated that further efforts by European nations to colonize land or interfere with states in North or South America would be viewed as acts of aggression requiring U.S. intervention...

of 1823, in which the United States warned the European powers not to interfere in the affairs of the newly independent states of the Western Hemisphere

Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere or western hemisphere is mainly used as a geographical term for the half of the Earth that lies west of the Prime Meridian and east of the Antimeridian , the other half being called the Eastern Hemisphere.In this sense, the western hemisphere consists of the western portions...

.

As world opinion became more pro-emancipation following World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, there was an institutionalised collective effort to advance the cause of emancipation through the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

. Under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, a number of mandate

League of Nations mandate

A League of Nations mandate was a legal status for certain territories transferred from the control of one country to another following World War I, or the legal instruments that contained the internationally agreed-upon terms for administering the territory on behalf of the League...

s were created. The expressed intention was to prepare these countries for self-government, but are often interpreted as a mere redistribution of control over the former colonies of the defeated powers, mainly Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

and the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

. This reassignment work continued through the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

, with a similar system of trust territories

United Nations Trust Territories

United Nations trust territories were the successors of the remaining League of Nations mandates and came into being when the League of Nations ceased to exist in 1946. All of the trust territories were administered through the UN Trusteeship Council...

created to adjust control over both former colonies and mandated territories.

In referendums, some colonized populations have chosen to retain their colonial status, such as Gibraltar

Gibraltar

Gibraltar is a British overseas territory located on the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula at the entrance of the Mediterranean. A peninsula with an area of , it has a northern border with Andalusia, Spain. The Rock of Gibraltar is the major landmark of the region...

and French Guiana

French Guiana

French Guiana is an overseas region of France, consisting of a single overseas department located on the northern Atlantic coast of South America. It has borders with two nations, Brazil to the east and south, and Suriname to the west...

. There are even examples, such as the Falklands War

Falklands War

The Falklands War , also called the Falklands Conflict or Falklands Crisis, was fought in 1982 between Argentina and the United Kingdom over the disputed Falkland Islands and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands...

, in which an Imperial power goes to war to defend the right of a colony to continue to be a colony. Colonial powers have sometimes promoted decolonization in order to shed the financial, military and other burdens that tend to grow in those colonies where the colonial regimes have become more benign.

Decolonization is rarely achieved through a single historical act, but rather progresses through one or more stages of emancipation, each of which can be offered or fought for: these can include the introduction of elected representatives (advisory or voting; minority or majority or even exclusive), degrees of autonomy or self-rule. Thus, the final phase of decolonisation may in fact concern little more than handing over responsibility for foreign relations and security, and soliciting de jure recognition for the new sovereignty

Sovereignty

Sovereignty is the quality of having supreme, independent authority over a geographic area, such as a territory. It can be found in a power to rule and make law that rests on a political fact for which no purely legal explanation can be provided...

. But, even following the recognition of statehood, a degree of continuity can be maintained through bilateral treaties between now equal governments involving practicalities such as military training, mutual protection pacts, or even a garrison and/or military bases.

There is some debate over whether or not the Americas

Americas

The Americas, or America , are lands in the Western hemisphere, also known as the New World. In English, the plural form the Americas is often used to refer to the landmasses of North America and South America with their associated islands and regions, while the singular form America is primarily...

can be considered decolonized, as it was the colonist and their descendants who revolted and declared their independence instead of the indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of North and South America, their descendants and other ethnic groups who are identified with those peoples. Indigenous peoples are known in Canada as Aboriginal peoples, and in the United States as Native Americans...

, as is usually the case. Furthermore, included in this list of states where "decolonization" has not occurred as per the ideas reflected above are Australia, New Zealand.

Decolonization of the Spanish Americas

Decolonization of the Ottoman Empire

A number of peoples (mainly ChristianChristian

A Christian is a person who adheres to Christianity, an Abrahamic, monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth as recorded in the Canonical gospels and the letters of the New Testament...

s in the Balkans

Balkans

The Balkans is a geopolitical and cultural region of southeastern Europe...

) previously conquered by the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

were able to achieve independence in the nineteenth century, a process that peaked at the time of the Ottoman defeat in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78.

Egypt

In the wake of the 1798 French Invasion of EgyptFrench Invasion of Egypt

The Egyptian Campaign was Napoleon Bonaparte's campaign in "The Orient", ostensibly to protect French trade interests, undermine Britain's access to India, and to establish scientific enterprise in the region...

and its subsequent expulsion in 1801, the commander of an Albanian regiment, Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali of Egypt

Muhammad Ali Pasha al-Mas'ud ibn Agha was a commander in the Ottoman army, who became Wāli, and self-declared Khedive of Egypt and Sudan...

, was able to gain control of Egypt

Egypt Province, Ottoman Empire

Egypt was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1517, following the Ottoman–Mamluk War and the loss of Syria to the Ottomans in 1516. Egypt was administrated as an eyalet of the Ottoman Empire from 1517 until 1867, with an interruption during the French occupation of 1798 to 1801.Egypt was always a...

. Although he was acknowledged by the Sultan

Selim III

Selim III was the reform-minded Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1789 to 1807. The Janissaries eventually deposed and imprisoned him, and placed his cousin Mustafa on the throne as Mustafa IV...

in Constantinople

Istanbul

Istanbul , historically known as Byzantium and Constantinople , is the largest city of Turkey. Istanbul metropolitan province had 13.26 million people living in it as of December, 2010, which is 18% of Turkey's population and the 3rd largest metropolitan area in Europe after London and...

in 1805 as his pasha

Pasha

Pasha or pascha, formerly bashaw, was a high rank in the Ottoman Empire political system, typically granted to governors, generals and dignitaries. As an honorary title, Pasha, in one of its various ranks, is equivalent to the British title of Lord, and was also one of the highest titles in...

, Muhammad Ali was in reality monarch of a practically sovereign state.

Greece

The Greek War of Independence (1821—1829) was fought to liberate Greece from a centuries-long OttomanOttoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

occupation. Independence was secured by the intervention of the British and French navies

French Navy

The French Navy, officially the Marine nationale and often called La Royale is the maritime arm of the French military. It includes a full range of fighting vessels, from patrol boats to a nuclear powered aircraft carrier and 10 nuclear-powered submarines, four of which are capable of launching...

and the French

French Army

The French Army, officially the Armée de Terre , is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces.As of 2010, the army employs 123,100 regulars, 18,350 part-time reservists and 7,700 Legionnaires. All soldiers are professionals, following the suspension of conscription, voted in...

and Russian armies

Imperial Russian Army

The Imperial Russian Army was the land armed force of the Russian Empire, active from around 1721 to the Russian Revolution of 1917. In the early 1850s, the Russian army consisted of around 938,731 regular soldiers and 245,850 irregulars . Until the time of military reform of Dmitry Milyutin in...

, but Greece was limited to an area including perhaps only one-third of the Turkish Greeks. The war also ended many of the privileges of the Phanariot Greeks of Constantinople

Istanbul

Istanbul , historically known as Byzantium and Constantinople , is the largest city of Turkey. Istanbul metropolitan province had 13.26 million people living in it as of December, 2010, which is 18% of Turkey's population and the 3rd largest metropolitan area in Europe after London and...

and saw the Great Powers impose a foreign dynasty

Otto of Greece

Otto, Prince of Bavaria, then Othon, King of Greece was made the first modern King of Greece in 1832 under the Convention of London, whereby Greece became a new independent kingdom under the protection of the Great Powers .The second son of the philhellene King Ludwig I of Bavaria, Otto ascended...

over the previously self-proclaimed Hellenic Republic

First Hellenic Republic

The First Hellenic Republic is a name used to refer to the provisional Greek state during the Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire...

.

Bulgaria

Following a failed Bulgarian revoltApril Uprising

The April Uprising was an insurrection organised by the Bulgarians in the Ottoman Empire from April to May 1876, which indirectly resulted in the re-establishment of Bulgaria as an autonomous nation in 1878...

in 1876, the subsequent Russo-Turkish war ended with the provisional Treaty of San Stefano

Treaty of San Stefano

The Preliminary Treaty of San Stefano was a treaty between Russia and the Ottoman Empire signed at the end of the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–78...

established a huge new realm of Bulgaria including most of Macedonia

Macedonia (region)

Macedonia is a geographical and historical region of the Balkan peninsula in southeastern Europe. Its boundaries have changed considerably over time, but nowadays the region is considered to include parts of five Balkan countries: Greece, the Republic of Macedonia, Bulgaria, Albania, Serbia, as...

and Thrace. The final 1878 Treaty of Berlin

Treaty of Berlin, 1878

The Treaty of Berlin was the final act of the Congress of Berlin , by which the United Kingdom, Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Russia and the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Abdul Hamid II revised the Treaty of San Stefano signed on March 3 of the same year...

allowed the other Great Powers to limit the size of the new Russian client state

Client state

Client state is one of several terms used to describe the economic, political and/or military subordination of one state to a more powerful state in international affairs...

and even briefly divided this rump state in two, Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia

Eastern Rumelia

Eastern Rumelia or Eastern Roumelia was an administratively autonomous province in the Ottoman Empire and Principality of Bulgaria from 1878 to 1908. It was under full Bulgarian control from 1885 on, when it willingly united with the tributary Principality of Bulgaria after a bloodless revolution...

, but the irredentist

Irredentism

Irredentism is any position advocating annexation of territories administered by another state on the grounds of common ethnicity or prior historical possession, actual or alleged. Some of these movements are also called pan-nationalist movements. It is a feature of identity politics and cultural...

claims from the first treaty would direct Bulgarian claims through the first

First Balkan War

The First Balkan War, which lasted from October 1912 to May 1913, pitted the Balkan League against the Ottoman Empire. The combined armies of the Balkan states overcame the numerically inferior and strategically disadvantaged Ottoman armies and achieved rapid success...

and second Balkan War

Second Balkan War

The Second Balkan War was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 29 June 1913. Bulgaria had a prewar agreement about the division of region of Macedonia...

s and both World Wars.

Romania

Romania fought on the Russian side in the Russo-Turkish War and in the 1878 Treaty of BerlinTreaty of Berlin, 1878

The Treaty of Berlin was the final act of the Congress of Berlin , by which the United Kingdom, Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Russia and the Ottoman Empire under Sultan Abdul Hamid II revised the Treaty of San Stefano signed on March 3 of the same year...

, Romania was recognized as an independent

Romanian War of Independence

The Romanian War of Independence is the name used in Romanian historiography to refer to the 1877-1878 Russo-Turkish war, following which Romania, fighting on the Russian side, gained independence from the Ottoman Empire...

state by the Great Powers.

Serbia

Decades of armed and unarmed struggle ended with the recognition of SerbiaSerbia

Serbia , officially the Republic of Serbia , is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeast Europe, covering the southern part of the Carpathian basin and the central part of the Balkans...

n independence from the Ottoman Empire at the Congress of Berlin

Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin was a meeting of the European Great Powers' and the Ottoman Empire's leading statesmen in Berlin in 1878. In the wake of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, the meeting's aim was to reorganize the countries of the Balkans...

in 1878.

Montenegro

The independence of the Principality of MontenegroPrincipality of Montenegro

The Principality of Montenegro was a former realm in Southeastern Europe. It existed from 13 March 1852 to 28 August 1910. It was then proclaimed a kingdom by Knjaz Nikola, who then became king....

from the Ottoman Empire was recognized at the congress of Berlin

Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin was a meeting of the European Great Powers' and the Ottoman Empire's leading statesmen in Berlin in 1878. In the wake of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78, the meeting's aim was to reorganize the countries of the Balkans...

in 1878.

Western European colonial powers

Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also known as the Race for Africa or Partition of Africa was a process of invasion, occupation, colonization and annexation of African territory by European powers during the New Imperialism period, between 1881 and World War I in 1914...

and the Opium Wars, marked the zenith of European colonization. It also marked the acceleration of the trends that would end it. The extraordinary material demands of the conflict had spread economic change across the world (notably inflation), and the associated social pressures of "war imperialism" created both peasant unrest and a burgeoning middle class.

Economic growth

Economic growth

In economics, economic growth is defined as the increasing capacity of the economy to satisfy the wants of goods and services of the members of society. Economic growth is enabled by increases in productivity, which lowers the inputs for a given amount of output. Lowered costs increase demand...

created stakeholders with their own demands, while racial issues meant these people clearly stood apart from the colonial middle-class and had to form their own group. The start of mass nationalism

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

, as a concept and practice, would fatally undermine the ideologies of imperialism.

There were, naturally, other factors, from agrarian change (and disaster – French Indochina

French Indochina

French Indochina was part of the French colonial empire in southeast Asia. A federation of the three Vietnamese regions, Tonkin , Annam , and Cochinchina , as well as Cambodia, was formed in 1887....

), changes or developments in religion (Buddhism

Buddhism

Buddhism is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha . The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th...

in Burma, Islam

Islam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

in the Dutch East Indies

Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies was a Dutch colony that became modern Indonesia following World War II. It was formed from the nationalised colonies of the Dutch East India Company, which came under the administration of the Netherlands government in 1800....

, marginally people like John Chilembwe

John Chilembwe

Reverend John Chilembwe was a Baptist educator and an early figure in resistance to colonialism in Nyasaland, now Malawi. Today John Chilembwe is celebrated as a hero for independence, and John Chilembwe Day is observed annually on January 15 in Malawi.-Early Life and Education:Chilembwe attended...

in Nyasaland

Malawi

The Republic of Malawi is a landlocked country in southeast Africa that was formerly known as Nyasaland. It is bordered by Zambia to the northwest, Tanzania to the northeast, and Mozambique on the east, south and west. The country is separated from Tanzania and Mozambique by Lake Malawi. Its size...

), and the impact of the depression of the 1930s.

The Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

, despite the concentration of its impact on the industrialized world, was also exceptionally damaging in the rural colonies. Agricultural prices fell much harder and faster than those of industrial goods. From around 1925 until World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, the colonies suffered. The colonial powers concentrated on domestic issues, protectionism

Protectionism

Protectionism is the economic policy of restraining trade between states through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, restrictive quotas, and a variety of other government regulations designed to allow "fair competition" between imports and goods and services produced domestically.This...

and tariffs, disregarding the damage done to international trade flows. The colonies, almost all primary "cash crop

Cash crop

In agriculture, a cash crop is a crop which is grown for profit.The term is used to differentiate from subsistence crops, which are those fed to the producer's own livestock or grown as food for the producer's family...

" producers, lost the majority of their export income and were forced away from the "open" complementary colonial economies to "closed" systems. While some areas returned to subsistence farming (British Malaya

British Malaya

British Malaya loosely described a set of states on the Malay Peninsula and the Island of Singapore that were brought under British control between the 18th and the 20th centuries...

) others diversified (India, West Africa

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of the African continent. Geopolitically, the UN definition of Western Africa includes the following 16 countries and an area of approximately 5 million square km:-Flags of West Africa:...

), and some began to industrialise. These economies would not fit the colonial straitjacket when efforts were made to renew the links. Further, the European-owned and -run plantation

Plantation

A plantation is a long artificially established forest, farm or estate, where crops are grown for sale, often in distant markets rather than for local on-site consumption...

s proved more vulnerable to extended deflation

Deflation (economics)

In economics, deflation is a decrease in the general price level of goods and services. Deflation occurs when the inflation rate falls below 0% . This should not be confused with disinflation, a slow-down in the inflation rate...

than native capitalist

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

s, reducing the dominance of "white" farmers in colonial economies and making the European government

Government

Government refers to the legislators, administrators, and arbitrators in the administrative bureaucracy who control a state at a given time, and to the system of government by which they are organized...

s and investors of the 1930s co-opt indigenous

Indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are ethnic groups that are defined as indigenous according to one of the various definitions of the term, there is no universally accepted definition but most of which carry connotations of being the "original inhabitants" of a territory....

elites — despite the implications for the future.

The efforts at colonial reform also hastened their end — notably the move from non-interventionist collaborative systems towards directed, disruptive, direct management to drive economic change. The creation of genuine bureaucratic government boosted the formation of indigenous bourgeoisie

Bourgeoisie

In sociology and political science, bourgeoisie describes a range of groups across history. In the Western world, between the late 18th century and the present day, the bourgeoisie is a social class "characterized by their ownership of capital and their related culture." A member of the...

. This was especially true in the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

, which seemed less capable (or less ruthless) in controlling political nationalism. Driven by pragmatic demands of budgets and manpower the British made deals with the nationalist elites. They dealt with the white dominion

Dominion

A dominion, often Dominion, refers to one of a group of autonomous polities that were nominally under British sovereignty, constituting the British Empire and British Commonwealth, beginning in the latter part of the 19th century. They have included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland,...

s, retained strategic resources at the cost of reducing direct control in Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

, and made numerous reforms in the British Raj

British Raj

British Raj was the British rule in the Indian subcontinent between 1858 and 1947; The term can also refer to the period of dominion...

, culminating in the Government of India Act

Government of India Act 1935

The Government of India Act 1935 was originally passed in August 1935 , and is said to have been the longest Act of Parliament ever enacted by that time. Because of its length, the Act was retroactively split by the Government of India Act 1935 into two separate Acts:# The Government of India...

(1935).

Despite these efforts though, the British Government continued to slowly lose their control of the Raj. The end of World War II allowed India, in addition to various other European colonies, to take advantage of the postwar chaos that had began to exist in Europe during the mid 1940s. Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, India's independence movement leader, realized the advantage in conducting a peaceful resistance to the British Empire's attempts to retake control of their "crown jewel". By becoming a symbol of both peace and opposition to British imperialism, many Indian citizens began to view the British as the cause of India's violence leading to a new found sense of nationalism

Nationalist Movements in India

The Nationalist Movements in India were organised mass movements emphasising and raising questions concerning the interests of the people of India. In most of these movements, people were themselves encouraged to take action. Due to several factors, these movements failed to win Independence for...

among its population. With this new wave of Indian nationalism, Gandhi was eventually able to garner the support needed to push back the British and create an independent India in 1947.

Tropical Africa was only fully drawn into the colonial system at the end of the 19th century. Nevertheless, the Union of South Africa

Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa is the historic predecessor to the present-day Republic of South Africa. It came into being on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the previously separate colonies of the Cape, Natal, Transvaal and the Orange Free State...

which, by introducing rigid racial segregation

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

from 1913 was already catalyzing the anti-colonial political agitation of half the continent. While, in the north-east the continued independence of the Empire of Ethiopia remained a beacon of hope. Colonial inequities ranged between extremes, from British Kenya's dispossession of local farmers, to Belgium's massacres in the Congo, from entrenched Portuguese racism to the looting of Benin City. However, with the resistance wars of the 1900s barely over, new modernising forms of African Nationalism began to gain strength in the early 20th-century with the emergence of Pan-Africanism, as advocated by the Jamaican journalist Marcus Garvey

Marcus Garvey

Marcus Mosiah Garvey, Jr., ONH was a Jamaican publisher, journalist, entrepreneur, and orator who was a staunch proponent of the Black Nationalism and Pan-Africanism movements, to which end he founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League...

(1887–1940) whose widely distributed newspapers demanded swift abolition of European imperialism, as well as republicanism in Egypt. Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah

Kwame Nkrumah was the leader of Ghana and its predecessor state, the Gold Coast, from 1952 to 1966. Overseeing the nation's independence from British colonial rule in 1957, Nkrumah was the first President of Ghana and the first Prime Minister of Ghana...

(1909–1972) who was inspired by the works of Garvey led Ghana to independence from colonial rule, while the republican Nasser led Egypt to resist British occupation.

United States

A former colony itself, the United StatesUnited States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

approached imperialism differently from the Great Powers and Japan. Much of its energy and rapidly expanding population was directed westward across the North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

n continent against American Indians

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of North and South America, their descendants and other ethnic groups who are identified with those peoples. Indigenous peoples are known in Canada as Aboriginal peoples, and in the United States as Native Americans...

, Spain

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire comprised territories and colonies administered directly by Spain in Europe, in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was therefore one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs, Spain reached the peak of its world power....

, and Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

. With eventual assistance from the British Navy, its Monroe Doctrine

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a policy of the United States introduced on December 2, 1823. It stated that further efforts by European nations to colonize land or interfere with states in North or South America would be viewed as acts of aggression requiring U.S. intervention...

reserved the Americas as its sphere of interest, prohibiting other states (particularly Spain) from recolonizing the recently freed polities of Latin America

Latin America

Latin America is a region of the Americas where Romance languages – particularly Spanish and Portuguese, and variably French – are primarily spoken. Latin America has an area of approximately 21,069,500 km² , almost 3.9% of the Earth's surface or 14.1% of its land surface area...

. Economic and political pressure, as well as assaults by filibusters

Filibuster (military)

A filibuster, or freebooter, is someone who engages in an unauthorized military expedition into a foreign country to foment or support a revolution...