History of Africa

Encyclopedia

Prehistory

Prehistory is the span of time before recorded history. Prehistory can refer to the period of human existence before the availability of those written records with which recorded history begins. More broadly, it refers to all the time preceding human existence and the invention of writing...

of Africa

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

and the emergence of Homo sapiens

Archaic Homo sapiens

Archaic Homo sapiens is a loosely defined term used to describe a number of varieties of Homo, as opposed to anatomically modern humans , in the period beginning 500,000 years ago....

in East Africa

East Africa

East Africa or Eastern Africa is the easterly region of the African continent, variably defined by geography or geopolitics. In the UN scheme of geographic regions, 19 territories constitute Eastern Africa:...

, continuing into the present as a patchwork of diverse and politically developing nation states. Agriculture began about 10,000 BCE and metallurgy in about 4000 BCE. The history

History

History is the discovery, collection, organization, and presentation of information about past events. History can also mean the period of time after writing was invented. Scholars who write about history are called historians...

of early civilization arose in Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

and later in the Maghreb

Maghreb

The Maghreb is the region of Northwest Africa, west of Egypt. It includes five countries: Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Mauritania and the disputed territory of Western Sahara...

and the Horn of Africa

Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa is a peninsula in East Africa that juts hundreds of kilometers into the Arabian Sea and lies along the southern side of the Gulf of Aden. It is the easternmost projection of the African continent...

. During the Middle Ages

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

, Islam

Islam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

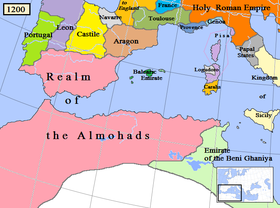

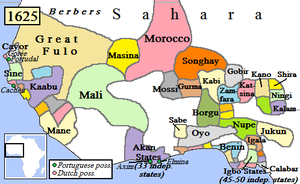

spread through the regions. Crossing the Maghreb and the Sahel

Sahel

The Sahel is the ecoclimatic and biogeographic zone of transition between the Sahara desert in the North and the Sudanian Savannas in the south.It stretches across the North African continent between the Atlantic Ocean and the Red Sea....

, a major centre of Muslim culture was at Timbuktu

Timbuktu

Timbuktu , formerly also spelled Timbuctoo, is a town in the West African nation of Mali situated north of the River Niger on the southern edge of the Sahara Desert. The town is the capital of the Timbuktu Region, one of the eight administrative regions of Mali...

. States and polities subsequently formed throughout the continent.

From the late 15th century, Europeans and Arabs took slaves from West

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of the African continent. Geopolitically, the UN definition of Western Africa includes the following 16 countries and an area of approximately 5 million square km:-Flags of West Africa:...

, Central

Central Africa

Central Africa is a core region of the African continent which includes Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Rwanda....

and Southeast Africa

East Africa

East Africa or Eastern Africa is the easterly region of the African continent, variably defined by geography or geopolitics. In the UN scheme of geographic regions, 19 territories constitute Eastern Africa:...

overseas in the African slave trade

African slave trade

Systems of servitude and slavery were common in many parts of Africa, as they were in much of the ancient world. In some African societies, the enslaved people were also indentured servants and fully integrated; in others, they were treated much worse...

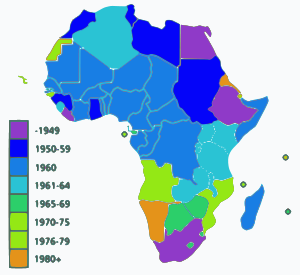

. European colonization of Africa developed rapidly in the Scramble for Africa

Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also known as the Race for Africa or Partition of Africa was a process of invasion, occupation, colonization and annexation of African territory by European powers during the New Imperialism period, between 1881 and World War I in 1914...

of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Following independence and struggles in many parts of the continent, decolonization

Decolonization

Decolonization refers to the undoing of colonialism, the unequal relation of polities whereby one people or nation establishes and maintains dependent Territory over another...

took place after the Second World War.

Africa's history has been challenging for researchers in the field of African studies

African studies

African studies is the study of Africa, especially the cultures and societies of Africa .The field includes the study of:Culture of Africa, History of Africa , Anthropology of Africa , Politics of Africa, Economy of Africa African studies is the study of Africa, especially the cultures and...

because of the scarcity of written sources in large parts of sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa as a geographical term refers to the area of the African continent which lies south of the Sahara. A political definition of Sub-Saharan Africa, instead, covers all African countries which are fully or partially located south of the Sahara...

. Scholarly techniques such as the recording of oral history

Oral history

Oral history is the collection and study of historical information about individuals, families, important events, or everyday life using audiotapes, videotapes, or transcriptions of planned interviews...

, historical linguistics

Historical linguistics

Historical linguistics is the study of language change. It has five main concerns:* to describe and account for observed changes in particular languages...

, archaeology and genetics have been crucial.

Paleolithic

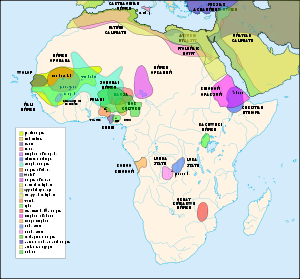

The first hominids evolved in Africa. According to paleontologyPaleontology

Paleontology "old, ancient", ὄν, ὀντ- "being, creature", and λόγος "speech, thought") is the study of prehistoric life. It includes the study of fossils to determine organisms' evolution and interactions with each other and their environments...

, the early hominids' skull anatomy was similar to the gorilla and chimpanzee, great apes

Great Apes

Great Apes may refer to*Great apes, species in the biological family Hominidae, including humans, chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans*Great Apes , a 1997 novel by Will Self...

that also evolved in Africa, but the hominids had adopted a biped

Biped

Bipedalism is a form of terrestrial locomotion where an organism moves by means of its two rear limbs, or legs. An animal or machine that usually moves in a bipedal manner is known as a biped , meaning "two feet"...

al locomotion and freed their hands. This gave them a crucial advantage, enabling them to live in both forested areas and on the open savanna

Savanna

A savanna, or savannah, is a grassland ecosystem characterized by the trees being sufficiently small or widely spaced so that the canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to reach the ground to support an unbroken herbaceous layer consisting primarily of C4 grasses.Some...

at a time when Africa was drying up and the savanna was encroaching on forested areas. This occurred 10 to 5 million years ago.

By 3 million years ago, several australopithecine

Australopithecus

Australopithecus is a genus of hominids that is now extinct. From the evidence gathered by palaeontologists and archaeologists, it appears that the Australopithecus genus evolved in eastern Africa around 4 million years ago before spreading throughout the continent and eventually becoming extinct...

hominid species had developed throughout southern

Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost region of the African continent, variably defined by geography or geopolitics. Within the region are numerous territories, including the Republic of South Africa ; nowadays, the simpler term South Africa is generally reserved for the country in English.-UN...

, eastern

East Africa

East Africa or Eastern Africa is the easterly region of the African continent, variably defined by geography or geopolitics. In the UN scheme of geographic regions, 19 territories constitute Eastern Africa:...

and central Africa

Central Africa

Central Africa is a core region of the African continent which includes Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Rwanda....

. They were tool users, not makers of tools. They scavenged for meat and were omnivores.

By approximately 2.3 million years ago, primitive stone tools were first used to scavenge kills made by other predators and to harvest carrion and marrow for their bones. In hunting, Homo habilis

Homo habilis

Homo habilis is a species of the genus Homo, which lived from approximately at the beginning of the Pleistocene period. The discovery and description of this species is credited to both Mary and Louis Leakey, who found fossils in Tanzania, East Africa, between 1962 and 1964. Homo habilis Homo...

was probably not capable of competing with large predators and was still more prey than hunter. H. habilis probably did steal eggs from nests and may have been able to catch small game

Game (food)

Game is any animal hunted for food or not normally domesticated. Game animals are also hunted for sport.The type and range of animals hunted for food varies in different parts of the world. This will be influenced by climate, animal diversity, local taste and locally accepted view about what can or...

and weakened larger prey (cubs and older animals). The tools were classed as Oldowan.

Around 1.8 million years ago Homo ergaster

Homo ergaster

Homo ergaster is an extinct chronospecies of Homo that lived in eastern and southern Africa during the early Pleistocene, about 2.5–1.7 million years ago.There is still disagreement on the subject of the classification, ancestry, and progeny of H...

first appeared in the fossil record in Africa. From Homo ergaster, Homo erectus

Homo erectus

Homo erectus is an extinct species of hominid that lived from the end of the Pliocene epoch to the later Pleistocene, about . The species originated in Africa and spread as far as India, China and Java. There is still disagreement on the subject of the classification, ancestry, and progeny of H...

evolved 1.5 million years ago. Some of the earlier representatives of this species were still fairly small-brained and used primitive stone tools, much like H. habilis. The brain later grew in size, and H. erectus eventually developed a more complex stone tool technology called the Acheulean

Acheulean

Acheulean is the name given to an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture associated with early humans during the Lower Palaeolithic era across Africa and much of West Asia, South Asia and Europe. Acheulean tools are typically found with Homo erectus remains...

. Possibly the first hunters, H. erectus mastered the art of making fire

Fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a material in the chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction products. Slower oxidative processes like rusting or digestion are not included by this definition....

and was the first hominid to leave Africa, colonizing most of the Old World

Old World

The Old World consists of those parts of the world known to classical antiquity and the European Middle Ages. It is used in the context of, and contrast with, the "New World" ....

and perhaps later giving rise to Homo floresiensis

Homo floresiensis

Homo floresiensis is a possible species, now extinct, in the genus Homo. The remains were discovered in 2003 on the island of Flores in Indonesia. Partial skeletons of nine individuals have been recovered, including one complete cranium...

. Although some recent writers suggest that Homo georgicus

Homo georgicus

Homo georgicus is a species of Homo that was suggested in 2002 to describe fossil skulls and jaws found in Dmanisi, Georgia in 1999 and 2001, which seem intermediate between Homo habilis and H. erectus. A partial skeleton was discovered in 2001. The fossils are about 1.8 million years old...

was the first and most primitive hominid to ever live outside Africa, many scientists consider H. georgicus to be an early and primitive member of the H. erectus species.

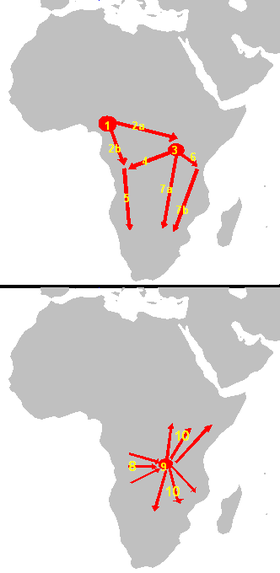

world. Their migration is traced by linguistic, cultural and genetic

Genetics

Genetics , a discipline of biology, is the science of genes, heredity, and variation in living organisms....

evidence.

Emergence of agriculture

Around 16,000 BCE, from the Red SeaRed Sea

The Red Sea is a seawater inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. The connection to the ocean is in the south through the Bab el Mandeb strait and the Gulf of Aden. In the north, there is the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Gulf of Suez...

hills to the northern Ethiopian Highlands

Ethiopian Highlands

The Ethiopian Highlands are a rugged mass of mountains in Ethiopia, Eritrea , and northern Somalia in the Horn of Africa...

, nuts, grasses and tubers were being collected for food. By 13,000 to 11,000 BCE, people began collecting wild grains. This spread to Western Asia, which domesticated its wild grains, wheat

Wheat

Wheat is a cereal grain, originally from the Levant region of the Near East, but now cultivated worldwide. In 2007 world production of wheat was 607 million tons, making it the third most-produced cereal after maize and rice...

and barley

Barley

Barley is a major cereal grain, a member of the grass family. It serves as a major animal fodder, as a base malt for beer and certain distilled beverages, and as a component of various health foods...

. Between 10,000 and 8000 BCE, northeast Africa was cultivating wheat and barley and raising sheep and cattle from southwest Asia. A wet climatic phase in Africa turned the Ethiopian Highlands into a mountain forest. Omotic speakers

Omotic languages

The Omotic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic family spoken in southwestern Ethiopia. The Ge'ez alphabet is used to write some Omotic languages, the Roman alphabet for some others. They are fairly agglutinative, and have complex tonal systems .-Language list:The North and South Omotic...

domesticated enset

Ensete

Ensete, or Enset, is a genus of plants, native to tropical regions of Africa and Asia. It is one of the three genera in the banana family, Musaceae.- Domesticated enset in Ethiopia :...

around 6500-5500 BCE. Around 7000 BCE, the settlers of the Ethiopian highlands domesticated donkeys, and by 4000 BCE domesticated donkeys had spread to southwest Asia. Cushitic speakers, partially turning away from cattle herding, domesticated teff

Teff

Eragrostis tef, known as teff, taf , or khak shir , is an annual grass, a species of lovegrass native to the northern Ethiopian Highlands of Northeast Africa....

and finger millet

Finger millet

Eleusine coracana, commonly Finger millet , also known as African millet or Ragi is an annual plant widely grown as a cereal in the arid areas of Africa and Asia. E...

between 5500 and 3500 BCE.

In the steppes and savannahs of the Sahara and Sahel, the Nilo-Saharan speakers

Nilo-Saharan languages

The Nilo-Saharan languages are a proposed family of African languages spoken by some 50 million people, mainly in the upper parts of the Chari and Nile rivers , including historic Nubia, north of where the two tributaries of Nile meet...

started to collect and domesticate wild millet and sorghum

Sorghum

Sorghum is a genus of numerous species of grasses, one of which is raised for grain and many of which are used as fodder plants either cultivated or as part of pasture. The plants are cultivated in warmer climates worldwide. Species are native to tropical and subtropical regions of all continents...

between 8000 and 6000 BCE. Later, gourds, watermelons, castor beans, and cotton

Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective capsule, around the seeds of cotton plants of the genus Gossypium. The fiber is almost pure cellulose. The botanical purpose of cotton fiber is to aid in seed dispersal....

were also collected and domesticated. The people started capturing wild cattle and holding them in circular thorn hedges, resulting in domestication. They also started making pottery. Fishing, using bone tipped harpoons, became a major activity in the numerous streams and lakes formed from the increased rains.

In West Africa, the wet phase ushered in expanding rainforest and wooded savannah from Senegal

Senegal

Senegal , officially the Republic of Senegal , is a country in western Africa. It owes its name to the Sénégal River that borders it to the east and north...

to Cameroon

Cameroon

Cameroon, officially the Republic of Cameroon , is a country in west Central Africa. It is bordered by Nigeria to the west; Chad to the northeast; the Central African Republic to the east; and Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the Republic of the Congo to the south. Cameroon's coastline lies on the...

. Between 9000 and 5000 BCE, Niger–Congo speakers

Niger–Congo languages

The Niger–Congo languages constitute one of the world's major language families, and Africa's largest in terms of geographical area, number of speakers, and number of distinct languages. They may constitute the world's largest language family in terms of distinct languages, although this question...

domesticated the oil palm

Oil palm

The oil palms comprise two species of the Arecaceae, or palm family. They are used in commercial agriculture in the production of palm oil. The African Oil Palm Elaeis guineensis is native to West Africa, occurring between Angola and Gambia, while the American Oil Palm Elaeis oleifera is native to...

and raffia palm

Raffia palm

The Raffia palms are a genus of twenty species of palms native to tropical regions of Africa, especially Madagascar, with one species also occurring in Central and South America. They grow up to 16 m tall and are remarkable for their compound pinnate leaves, the longest in the plant kingdom;...

. Two seed plants, black-eyed peas and voandzeia (African groundnuts) were domesticated, followed by okra

Okra

Okra is a flowering plant in the mallow family. It is valued for its edible green seed pods. The geographical origin of okra is disputed, with supporters of South Asian, Ethiopian and West African origins...

and kola nuts. Since most of the plants grew in the forest, the Niger–Congo speakers invented polished stone axes for clearing forest.

Most of southern Africa was occupied by pygmy peoples and Khoisan

Khoisan

Khoisan is a unifying name for two ethnic groups of Southern Africa, who share physical and putative linguistic characteristics distinct from the Bantu majority of the region. Culturally, the Khoisan are divided into the foraging San and the pastoral Khoi...

who engaged in hunting and gathering. Some of the oldest rock art was produced by them.

Just prior to Sahara

Sahara

The Sahara is the world's second largest desert, after Antarctica. At over , it covers most of Northern Africa, making it almost as large as Europe or the United States. The Sahara stretches from the Red Sea, including parts of the Mediterranean coasts, to the outskirts of the Atlantic Ocean...

n desertification, the communities that developed south of Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

in what is now modern day Sudan

Sudan

Sudan , officially the Republic of the Sudan , is a country in North Africa, sometimes considered part of the Middle East politically. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the...

were full participants in the Neolithic revolution

Neolithic Revolution

The Neolithic Revolution was the first agricultural revolution. It was the transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture and settlement. Archaeological data indicates that various forms of plants and animal domestication evolved independently in 6 separate locations worldwide circa...

and lived a settled to semi-nomadic lifestyle, with domesticated plants and animals. It has been suggested that megalith

Megalith

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. Megalithic describes structures made of such large stones, utilizing an interlocking system without the use of mortar or cement.The word 'megalith' comes from the Ancient...

s found at Nabta Playa

Nabta Playa

Nabta Playa was once a large basin in the Nubian Desert, located approximately 800 kilometers south of modern day Cairo or about 100 kilometers west of Abu Simbel in southern Egypt, 22° 32' north, 30° 42' east...

are examples of the world's first known archaeoastronomical

Archaeoastronomy

Archaeoastronomy is the study of how people in the past "have understood the phenomena in the sky how they used phenomena in the sky and what role the sky played in their cultures." Clive Ruggles argues it is misleading to consider archaeoastronomy to be the study of ancient astronomy, as modern...

devices, predating Stonehenge

Stonehenge

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument located in the English county of Wiltshire, about west of Amesbury and north of Salisbury. One of the most famous sites in the world, Stonehenge is composed of a circular setting of large standing stones set within earthworks...

by some 1,000 years. The sociocultural complexity observed at Nabta Playa and expressed by different levels of authority within the society there has been suggested as forming the basis for the structure of both the Neolithic society at Nabta and the Old Kingdom

Old Kingdom

Old Kingdom is the name given to the period in the 3rd millennium BC when Egypt attained its first continuous peak of civilization in complexity and achievement – the first of three so-called "Kingdom" periods, which mark the high points of civilization in the lower Nile Valley .The term itself was...

of Egypt.

By 5000 BCE, Africa entered a dry phase, and the climate of the Sahara region gradually became drier. The population trekked out of the Sahara region in all directions, including towards the Nile Valley below the Second Cataract, where they made permanent or semipermanent settlements. A major climatic recession occurred, lessening the heavy and persistent rains in central and eastern Africa. Since then, dry conditions have prevailed in eastern Africa.

Metallurgy

The first metals to be smelted in Africa were leadLead

Lead is a main-group element in the carbon group with the symbol Pb and atomic number 82. Lead is a soft, malleable poor metal. It is also counted as one of the heavy metals. Metallic lead has a bluish-white color after being freshly cut, but it soon tarnishes to a dull grayish color when exposed...

, copper

Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. Pure copper is soft and malleable; an exposed surface has a reddish-orange tarnish...

, and bronze

Bronze

Bronze is a metal alloy consisting primarily of copper, usually with tin as the main additive. It is hard and brittle, and it was particularly significant in antiquity, so much so that the Bronze Age was named after the metal...

in the fourth millennium BCE.

Copper was smelted in Egypt during the predynastic period

Predynastic Egypt

The Prehistory of Egypt spans the period of earliest human settlement to the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt in ca. 3100 BC, starting with King Menes/Narmer....

, and bronze came into use not long after 3000 BCE at the latest in Egypt and Nubia

Nubia

Nubia is a region along the Nile river, which is located in northern Sudan and southern Egypt.There were a number of small Nubian kingdoms throughout the Middle Ages, the last of which collapsed in 1504, when Nubia became divided between Egypt and the Sennar sultanate resulting in the Arabization...

. Nubia was a major source of copper as well as gold

Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and an atomic number of 79. Gold is a dense, soft, shiny, malleable and ductile metal. Pure gold has a bright yellow color and luster traditionally considered attractive, which it maintains without oxidizing in air or water. Chemically, gold is a...

. The use of gold and silver

Silver

Silver is a metallic chemical element with the chemical symbol Ag and atomic number 47. A soft, white, lustrous transition metal, it has the highest electrical conductivity of any element and the highest thermal conductivity of any metal...

in Egypt dates back to the predynastic period.

In the Aïr Mountains

Aïr Mountains

The Aïr Mountains is a triangular massif, located in northern Niger, within the Sahara desert...

, present-day Niger

Niger

Niger , officially named the Republic of Niger, is a landlocked country in Western Africa, named after the Niger River. It borders Nigeria and Benin to the south, Burkina Faso and Mali to the west, Algeria and Libya to the north and Chad to the east...

, copper was smelted independently of developments in the Nile valley between 3000 and 2500 BCE. The process used was not well developed, indicating that it was not brought from outside the region; it became more mature by about 1500 BCE.

By the 1st millennium BCE, iron working had been introduced in northwestern Africa, Egypt, and Nubia. In 670 BCE, Nubians were pushed out of Egypt by Assyrians

Assyrian people

The Assyrian people are a distinct ethnic group whose origins lie in ancient Mesopotamia...

using iron weapons, after which the use of iron in the Nile valley became widespread.

The theory of iron

Iron

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal in the first transition series. It is the most common element forming the planet Earth as a whole, forming much of Earth's outer and inner core. It is the fourth most common element in the Earth's crust...

spreading to sub-Saharan Africa via the Nubian city of Meroe

Meroë

Meroë Meroitic: Medewi or Bedewi; Arabic: and Meruwi) is an ancient city on the east bank of the Nile about 6 km north-east of the Kabushiya station near Shendi, Sudan, approximately 200 km north-east of Khartoum. Near the site are a group of villages called Bagrawiyah...

is no longer widely accepted. Metalworking

Metalworking

Metalworking is the process of working with metals to create individual parts, assemblies, or large scale structures. The term covers a wide range of work from large ships and bridges to precise engine parts and delicate jewelry. It therefore includes a correspondingly wide range of skills,...

in West Africa

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of the African continent. Geopolitically, the UN definition of Western Africa includes the following 16 countries and an area of approximately 5 million square km:-Flags of West Africa:...

has been dated as early as 2500 BCE at Egaro west of the Termit

Termit Massif

The Termit Massif is a mountainous region in southeastern Niger. Just to the south of the dunes of Tenere desert and the Erg of Bilma, the northern areas of the Termit, called the Gossololom consists of black volcanic peaks which jut from surrounding sand seas...

in Niger, and iron working was practiced there by 1500 BCE.

Iron smelting was developed in the area between Lake Chad

Lake Chad

Lake Chad is a historically large, shallow, endorheic lake in Africa, whose size has varied over the centuries. According to the Global Resource Information Database of the United Nations Environment Programme, it shrank as much as 95% from about 1963 to 1998; yet it also states that "the 2007 ...

and the African Great Lakes

African Great Lakes

The African Great Lakes are a series of lakes and the Rift Valley lakes in and around the geographic Great Rift Valley formed by the action of the tectonic East African Rift on the continent of Africa...

between 1000 and 600 BCE, long before it reached Egypt. Before 500 BCE, the Nok culture in the Jos Plateau

Jos Plateau

The Jos Plateau is a plateau located near the center of Nigeria. It covers 8600 km² and is bounded by 300-600 meter escarpments around much of its circumference. With an average altitude of 1280 metres and its highest point is Shere Hills 1829 meters...

was already smelting iron.

Antiquity

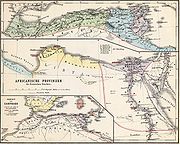

The ancient history of North AfricaNorth Africa

North Africa or Northern Africa is the northernmost region of the African continent, linked by the Sahara to Sub-Saharan Africa. Geopolitically, the United Nations definition of Northern Africa includes eight countries or territories; Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, and...

is inextricably linked to that of the Ancient Near East

Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia , ancient Egypt, ancient Iran The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia...

. This is particularly true of Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh...

, Nubia

Nubia

Nubia is a region along the Nile river, which is located in northern Sudan and southern Egypt.There were a number of small Nubian kingdoms throughout the Middle Ages, the last of which collapsed in 1504, when Nubia became divided between Egypt and the Sennar sultanate resulting in the Arabization...

and Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Ethiopia , officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is the second-most populous nation in Africa, with over 82 million inhabitants, and the tenth-largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2...

(Axumite Kingdom).

Phoenicia

Phoenicia

Phoenicia , was an ancient civilization in Canaan which covered most of the western, coastal part of the Fertile Crescent. Several major Phoenician cities were built on the coastline of the Mediterranean. It was an enterprising maritime trading culture that spread across the Mediterranean from 1550...

n cities such as Carthage

Carthage

Carthage , implying it was a 'new Tyre') is a major urban centre that has existed for nearly 3,000 years on the Gulf of Tunis, developing from a Phoenician colony of the 1st millennium BC...

were part of the Mediterranean Iron Age

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the archaeological period generally occurring after the Bronze Age, marked by the prevalent use of iron. The early period of the age is characterized by the widespread use of iron or steel. The adoption of such material coincided with other changes in society, including differing...

and Classical Antiquity

Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity is a broad term for a long period of cultural history centered on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient Rome, collectively known as the Greco-Roman world...

.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa as a geographical term refers to the area of the African continent which lies south of the Sahara. A political definition of Sub-Saharan Africa, instead, covers all African countries which are fully or partially located south of the Sahara...

developed more or less independently in those times.

Ancient Egypt

Desertification

Desertification is the degradation of land in drylands. Caused by a variety of factors, such as climate change and human activities, desertification is one of the most significant global environmental problems.-Definitions:...

of the Sahara, settlement became concentrated in the Nile Valley, where numerous sacral chiefdoms appeared. The regions with the largest population pressure were in the delta region of Lower Egypt

Lower Egypt

Lower Egypt is the northern-most section of Egypt. It refers to the fertile Nile Delta region, which stretches from the area between El-Aiyat and Zawyet Dahshur, south of modern-day Cairo, and the Mediterranean Sea....

, in Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt

Upper Egypt is the strip of land, on both sides of the Nile valley, that extends from the cataract boundaries of modern-day Aswan north to the area between El-Ayait and Zawyet Dahshur . The northern section of Upper Egypt, between El-Ayait and Sohag is sometimes known as Middle Egypt...

, and also along the second and third cataracts

Cataracts of the Nile

The cataracts of the Nile are shallow lengths of the Nile between Aswan and Khartoum where the surface of the water is broken by many small boulders and stones protruding out of the river bed, as well as many rocky islets. Aswan is also the Southern boundary of Upper Egypt...

of the Dongola

Dongola

Dongola , also spelled Dunqulah, and formerly known as Al 'Urdi, is the capital of the state of Northern in Sudan, on the banks of the Nile. It should not be confused with Old Dongola, an ancient city located 80 km upstream on the opposite bank....

reach of the Nile in Nubia. This population pressure and growth was brought about by the cultivation of southwest Asian crops, including wheat and barley, and the raising of sheep, goats, and cattle. Population growth led to competition for farm land and the need to regulate farming. Regulation was established by the formation of bureaucracies among sacral chiefdoms. The first and most powerful of the chiefdoms was Ta-Seti

Ta-Seti

Ta-Seti was one of 42 nomoi in Ancient Egypt. Ta-Seti also marked the border area towards Nubia.-Geography:Ta-Seti was the earliest Nubian Kingdom, dated 3,700 BCE...

, founded around 3500 BCE. The idea of sacral chiefdom spread throughout upper and lower Egypt.

Narmer

Narmer was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the Early Dynastic Period . He is thought to be the successor to the Protodynastic pharaohs Scorpion and/or Ka, and he is considered by some to be the unifier of Egypt and founder of the First Dynasty, and therefore the first pharaoh of unified Egypt.The...

(Menes) in 3100 BCE. Instead being viewed as a sacral chief, he became a divine king

Imperial cult

An imperial cult is a form of state religion in which an emperor, or a dynasty of emperors , are worshipped as messiahs, demigods or deities. "Cult" here is used to mean "worship", not in the modern pejorative sense...

. The henotheism

Henotheism

Henotheism is the belief and worship of a single god while accepting the existence or possible existence of other deities...

, or worship of a single god within a polytheistic system, practiced in the sacral chiefdoms along upper and lower Egypt, became the polytheistic religion of ancient Egypt. Bureaucracies became more centralized under the pharaohs, run by viziers, governors, tax collectors, generals, artists, and technicians. They engaged in tax collecting, organizing of labor for major public works, and building irrigation systems, pyramid

Pyramid

A pyramid is a structure whose outer surfaces are triangular and converge at a single point. The base of a pyramid can be trilateral, quadrilateral, or any polygon shape, meaning that a pyramid has at least three triangular surfaces...

s, temples, and canals. During the Fourth Dynasty

Fourth dynasty of Egypt

The fourth dynasty of ancient Egypt is characterized as a "golden age" of the Old Kingdom. Dynasty IV lasted from ca. 2613 to 2494 BC...

(2620-2480

BCE), long distance trade was developed, with the Levant

Levant

The Levant or ) is the geographic region and culture zone of the "eastern Mediterranean littoral between Anatolia and Egypt" . The Levant includes most of modern Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, the Palestinian territories, and sometimes parts of Turkey and Iraq, and corresponds roughly to the...

for timber, with Nubia for gold and skins, with Punt

Land of Punt

The Land of Punt, also called Pwenet, or Pwene by the ancient Egyptians, was a trading partner known for producing and exporting gold, aromatic resins, African blackwood, ebony, ivory, slaves and wild animals...

for frankincense

Frankincense

Frankincense, also called olibanum , is an aromatic resin obtained from trees of the genus Boswellia, particularly Boswellia sacra, B. carteri, B. thurifera, B. frereana, and B. bhaw-dajiana...

, and also with the western Libyan territories. For most of the Old Kingdom

Old Kingdom

Old Kingdom is the name given to the period in the 3rd millennium BC when Egypt attained its first continuous peak of civilization in complexity and achievement – the first of three so-called "Kingdom" periods, which mark the high points of civilization in the lower Nile Valley .The term itself was...

, Egypt developed her fundamental systems, institutions and culture, always through the central bureaucracy and by the divinity of the Pharaoh

Pharaoh

Pharaoh is a title used in many modern discussions of the ancient Egyptian rulers of all periods. The title originates in the term "pr-aa" which means "great house" and describes the royal palace...

.

After the third millennium BCE, Egypt started to extend direct military and political control over her southern and western neighbors. By 2200 BCE, the Old Kingdom's stability was undermined by rivalry among the governors of the nomes

Nome (Egypt)

A nome was a subnational administrative division of ancient Egypt. Today's use of the Greek nome rather than the Egyptian term sepat came about during the Ptolemaic period. Fascinated with Egypt, Greeks created many historical records about the country...

who challenged the power of pharaohs and by invasions of Asiatics into the delta. The First Intermediate Period had begun, a time of political division and uncertainty.

By 2130, the period of stagnation was ended by Mentuhotep

Mentuhotep I

Mentuhotep I was a local Egyptian prince at Thebes during the First Intermediate Period. He became the first openly acknowledged ruler of the Eleventh dynasty by assuming the title of first "supreme chief of Upper Egypt" and, later, declaring himself king over all Egypt. He is named as a nomarch in...

, the first Pharaoh of the 11th dynasty, and the emergence of the Middle Kingdom

Middle Kingdom of Egypt

The Middle Kingdom of Egypt is the period in the history of ancient Egypt stretching from the establishment of the Eleventh Dynasty to the end of the Fourteenth Dynasty, between 2055 BC and 1650 BC, although some writers include the Thirteenth and Fourteenth dynasties in the Second Intermediate...

. Pyramid building resumed, long-distance trade re-emerged, and the center of power moved from Memphis

Memphis, Egypt

Memphis was the ancient capital of Aneb-Hetch, the first nome of Lower Egypt. Its ruins are located near the town of Helwan, south of Cairo.According to legend related by Manetho, the city was founded by the pharaoh Menes around 3000 BC. Capital of Egypt during the Old Kingdom, it remained an...

to Thebes

Thebes, Egypt

Thebes is the Greek name for a city in Ancient Egypt located about 800 km south of the Mediterranean, on the east bank of the river Nile within the modern city of Luxor. The Theban Necropolis is situated nearby on the west bank of the Nile.-History:...

. Connections with the southern regions of Kush

Kingdom of Kush

The native name of the Kingdom was likely kaš, recorded in Egyptian as .The name Kash is probably connected to Cush in the Hebrew Bible , son of Ham ....

, Wawat and Irthet at the second cataract were made stronger. Then came the Second Intermediate Period, with the invasion of the Hyksos

Hyksos

The Hyksos were an Asiatic people who took over the eastern Nile Delta during the twelfth dynasty, initiating the Second Intermediate Period of ancient Egypt....

on horse-drawn chariots and utilizing bronze weapons, a technology heretofore unseen in Egypt. Horse-drawn chariots soon spread to the west in the inhabitable Sahara and North Africa

North Africa

North Africa or Northern Africa is the northernmost region of the African continent, linked by the Sahara to Sub-Saharan Africa. Geopolitically, the United Nations definition of Northern Africa includes eight countries or territories; Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, and...

. The Hyksos failed to hold on to their Egyptian territories and were absorbed by Egyptian society. This eventually led to one of Egypt's most powerful phases, the New Kingdom

New Kingdom

The New Kingdom of Egypt, also referred to as the Egyptian Empire is the period in ancient Egyptian history between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC, covering the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth Dynasties of Egypt....

(1580–1080 BCE), with the Eighteenth Dynasty. Egypt became a superpower controlling Nubia and Palestine

Palestine

Palestine is a conventional name, among others, used to describe the geographic region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, and various adjoining lands....

while exerting political influence on the Libyans to the West and on the Mediterranean.

As before, the New Kingdom ended with invasion from the west by Libyan princes, leading to the Third Intermediate Period. Beginning with Shoshenq I

Shoshenq I

Hedjkheperre Setepenre Shoshenq I , , also known as Sheshonk or Sheshonq I , was a Meshwesh Berber king of Egypt—of Libyan ancestry—and the founder of the Twenty-second Dynasty...

, the Twenty-second Dynasty

Twenty-second dynasty of Egypt

The Twenty-First, Twenty-Second, Twenty-Third, Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Fifth Dynasties of ancient Egypt are often combined under the group title, Third Intermediate Period.-Rulers:...

was established. It ruled for two centuries.

To the south, Nubian independence and strength was being reasserted. This reassertion led to the conquest of Egypt by Nubia, begun by Kashta

Kashta

Kashta was a king of the Kushite Dynasty and the successor of Alara. His name translates literally as "The Kushite".-Family:Kashta is thought to be a brother of his predecessor Alara. Both Alara and Kashta were thought to have married their sisters...

and completed by Piye

Piye

Piye, was a Kushite king and founder of the Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt who ruled Egypt from 747 BCE to 716 BCE according to Peter Clayton. He ruled from the city of Napata, located deep in Nubia, Sudan...

(Pianhky, 751-730 BCE) and Shabaka

Shabaka

Shabaka or Shabaka Neferkare, 'Beautiful is the Soul of Re', was a Kushite pharaoh of the Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt, between according to Peter Clayton .-Family:...

(716-695 BCE). This was the birth of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty

Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt

The twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt, known as the Nubian Dynasty or the Kushite Empire, was the last dynasty of the Third Intermediate Period of Ancient Egypt....

of Egypt. The Nubians tried to re-establish Egyptian traditions and customs. They ruled Egypt for a hundred years. This was ended by an Assyrian invasion, with Taharqa

Taharqa

Taharqa was a pharaoh of the Ancient Egyptian 25th dynasty and king of the Kingdom of Kush, which was located in Northern Sudan.Taharqa was the son of Piye, the Nubian king of Napata who had first conquered Egypt. Taharqa was also the cousin and successor of Shebitku. The successful campaigns of...

experiencing the full might of Assyrian iron weapons. The Nubian pharaoh Tantamani

Tantamani

Tantamani or Tanwetamani or Tementhes was a Pharaoh of Egypt and the Kingdom of Kush located in Northern Sudan and a member of the Nubian or Twenty-fifth dynasty of Egypt...

was the last of the Twenty-fifth dynasty.

When the Assyrians and Nubians left, a new Twenty-sixth Dynasty

Twenty-sixth dynasty of Egypt

The Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt was the last native dynasty to rule Egypt before the Persian conquest in 525 BC . The Dynasty's reign The Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt (also written Dynasty XXVI or Dynasty 26) was the last native dynasty to rule Egypt before the Persian conquest in 525 BC...

emerged from Sais

Sais, Egypt

Sais or Sa el-Hagar was an ancient Egyptian town in the Western Nile Delta on the Canopic branch of the Nile. It was the provincial capital of Sap-Meh, the fifth nome of Lower Egypt and became the seat of power during the Twenty-fourth dynasty of Egypt and the Saite Twenty-sixth dynasty of Egypt ...

. It lasted until 525 BCE, when Egypt was invaded by the Persians

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire , sometimes known as First Persian Empire and/or Persian Empire, was founded in the 6th century BCE by Cyrus the Great who overthrew the Median confederation...

. Unlike the Assyrians, the Persians stayed. In 332, Egypt was conquered by Alexander the Great. This was the beginning of the Ptolemaic dynasty

Ptolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty, was a Macedonian Greek royal family which ruled the Ptolemaic Empire in Egypt during the Hellenistic period. Their rule lasted for 275 years, from 305 BC to 30 BC...

, which ended with Roman conquest in 30 BCE. Pharaonic Egypt had come to an end.

Ancient Greek influence

Greeks founded the city of CyreneCyrene, Libya

Cyrene was an ancient Greek colony and then a Roman city in present-day Shahhat, Libya, the oldest and most important of the five Greek cities in the region. It gave eastern Libya the classical name Cyrenaica that it has retained to modern times.Cyrene lies in a lush valley in the Jebel Akhdar...

in Ancient Libya

Ancient Libya

The Latin name Libya referred to the region west of the Nile Valley, generally corresponding to modern Northwest Africa. Climate changes affected the locations of the settlements....

around 631 BC. Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica is the eastern coastal region of Libya.Also known as Pentapolis in antiquity, it was part of the Creta et Cyrenaica province during the Roman period, later divided in Libia Pentapolis and Libia Sicca...

became a flourishing colony, though being hemmed in on all sides by absolute desert it had little or no influence on inner Africa. The Greeks, however, exerted a powerful influence in Egypt. To Alexander the Great the city of Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

owes its foundation (332 BC

332 BC

Year 332 BC was a year of the pre-Julian Roman calendar. At the time, it was known as the Year of the Consulship of Calvinus and Arvina...

), and under the Hellenistic dynasty of the Ptolemies

Ptolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty, was a Macedonian Greek royal family which ruled the Ptolemaic Empire in Egypt during the Hellenistic period. Their rule lasted for 275 years, from 305 BC to 30 BC...

attempts were made to penetrate southward, and in this way was obtained some knowledge of Ethiopia.

Nubia

Ebony

Ebony is a dense black wood, most commonly yielded by several species in the genus Diospyros, but ebony may also refer to other heavy, black woods from unrelated species. Ebony is dense enough to sink in water. Its fine texture, and very smooth finish when polished, make it valuable as an...

and ivory

Ivory trade

The ivory trade is the commercial, often illegal trade in the ivory tusks of the hippopotamus, walrus, narwhal, mammoth, and most commonly, Asian and African elephants....

to the Old Kingdom

Old Kingdom

Old Kingdom is the name given to the period in the 3rd millennium BC when Egypt attained its first continuous peak of civilization in complexity and achievement – the first of three so-called "Kingdom" periods, which mark the high points of civilization in the lower Nile Valley .The term itself was...

. By the 32nd century BCE, Ta-Seti was in decline. After the unification of Egypt by Narmer

Narmer

Narmer was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh of the Early Dynastic Period . He is thought to be the successor to the Protodynastic pharaohs Scorpion and/or Ka, and he is considered by some to be the unifier of Egypt and founder of the First Dynasty, and therefore the first pharaoh of unified Egypt.The...

in 3100 BCE, Ta-Seti was invaded by the Pharaoh Hor-Aha

Hor-Aha

Hor-Aha is considered the second pharaoh of the first dynasty of ancient Egypt in current Egyptology. He lived around the thirty-first century BC.- Name :...

of the First Dynasty, destroying the final remnants of the kingdom. Ta-Seti is affiliated with A-Group

A-group

A-Group is the designation for a distinct culture that arose between the First and Second Cataracts of the Nile in Nubia betweenthe Egyptian 1st dynasty and the 3rd millennium BC.The A-Group settled on very poor land with scarce natural resources, yet...

culture known to archaeology.

Small sacral kingdoms continued to dot the Nubian portion of the Nile for centuries after 3000 BCE. Around the latter part of the third millennium, there was further consolidation of the sacral kingdoms. Two kingdoms in particular emerged: the Sai kingdom, immediately south of Egypt, and Kingdom of Kerma

Kingdom of Kerma

The Kerma culture is a prehistoric culture which flourished from around 2500 BCE to about 1520 BCE in what is now Sudan, centered at Kerma.It emerged as a major centre during the Middle Kingdom period of Ancient Egypt....

at the third cataract. Sometime around the 18th century BCE, the Kingdom of Kerma conquered the Kingdom of Sai, becoming a serious rival to Egypt. Kerma occupied a territory from the first cataract to the confluences of the Blue Nile

Blue Nile

The Blue Nile is a river originating at Lake Tana in Ethiopia. With the White Nile, the river is one of the two major tributaries of the Nile...

, White Nile

White Nile

The White Nile is a river of Africa, one of the two main tributaries of the Nile from Egypt, the other being the Blue Nile. In the strict meaning, "White Nile" refers to the river formed at Lake No at the confluence of the Bahr al Jabal and Bahr el Ghazal rivers...

, and River Atbara. About 1575 to 1550 BCE, during the latter part of the Seventeenth Dynasty

Seventeenth dynasty of Egypt

The Fifteenth, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Dynasties of ancient Egypt are often combined under the group title, Second Intermediate Period. The Seventeenth Dynasty dates approximately from 1580 to 1550 BC.-Rulers:...

, the Kingdom of Kerma invaded Egypt. The Kingdom of Kerma allied itself with the Hyksos

Hyksos

The Hyksos were an Asiatic people who took over the eastern Nile Delta during the twelfth dynasty, initiating the Second Intermediate Period of ancient Egypt....

invasion of Egypt.

Egypt eventually re-energized under the Eighteenth Dynasty

Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt

The eighteenth dynasty of ancient Egypt is perhaps the best known of all the dynasties of ancient Egypt...

and conquered the Kingdom of Kerma or Kush

Kingdom of Kush

The native name of the Kingdom was likely kaš, recorded in Egyptian as .The name Kash is probably connected to Cush in the Hebrew Bible , son of Ham ....

, ruling it for almost 500 years. The Kushites were Egyptianized during this period. By 1100 BCE, the Egyptians had withdrawn from Kush. The region regained independence and reasserted its culture. Kush built a new religion around Amun

Amun

Amun, reconstructed Egyptian Yamānu , was a god in Egyptian mythology who in the form of Amun-Ra became the focus of the most complex system of theology in Ancient Egypt...

and made Napata

Napata

Napata was a city-state of ancient Nubia on the west bank of the Nile River, at the site of modern Karima, Northern Sudan.During the 8th to 7th centuries BC, Napata was the capital of the Nubian kingdom of Kush, whence the 25th, or Nubian Dynasty conquered Egypt...

its spiritual center. In 730 BCE, the Kingdom of Kush invaded Egypt, taking over Thebes

Thebes, Egypt

Thebes is the Greek name for a city in Ancient Egypt located about 800 km south of the Mediterranean, on the east bank of the river Nile within the modern city of Luxor. The Theban Necropolis is situated nearby on the west bank of the Nile.-History:...

and beginning the Nubian Empire. The empire extended from Palestine to the confluences of the Blue Nile, the White Nile, and River Atbara.

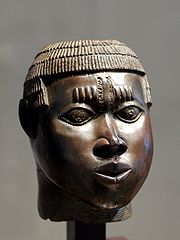

In 760 BCE, the Kushites were expelled from Egypt by iron-wielding Assyrians. Later, the administrative capital was moved from Napata to Meröe

Meroë

Meroë Meroitic: Medewi or Bedewi; Arabic: and Meruwi) is an ancient city on the east bank of the Nile about 6 km north-east of the Kabushiya station near Shendi, Sudan, approximately 200 km north-east of Khartoum. Near the site are a group of villages called Bagrawiyah...

, developing into a new Nubian culture. Initially Meroites were highly Egyptianized, but they subsequently began to take on distinctive features. Nubia became a center of iron-making and cotton cloth manufacturing. Egyptian writing was replaced by the Meroitic alphabet. The lion god Apedemak

Apedemak

Apedemak, alt Apademak, was a lion-headed warrior god worshiped in Nubia by Meroitic peoples. A number of Meroitic temples dedicated to Apedemak are known from the Butana region: Naqa, Meroe, and Musawwarat es-Sufra, which seems to be his chief cult place...

was added to the Egyptian pantheon of gods. Trade links to the Red Sea

Red Sea

The Red Sea is a seawater inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. The connection to the ocean is in the south through the Bab el Mandeb strait and the Gulf of Aden. In the north, there is the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and the Gulf of Suez...

increased, linking Nubia with Mediterranean Greece

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

. Its architecture and art became more unique, with pictures of lions, ostriches, giraffes, and elephants. Eventually with the rise of Aksum, Nubia's trade links were broken and it suffered environmental degradation from the tree cutting required for iron production. In 350 CE, the Aksumite king Ezana brought Meröe to an end.

Carthage

Berber people

Berbers are the indigenous peoples of North Africa west of the Nile Valley. They are continuously distributed from the Atlantic to the Siwa oasis, in Egypt, and from the Mediterranean to the Niger River. Historically they spoke the Berber language or varieties of it, which together form a branch...

, as Libyans

Ancient Libya

The Latin name Libya referred to the region west of the Nile Valley, generally corresponding to modern Northwest Africa. Climate changes affected the locations of the settlements....

. The Libyans were agriculturalists like the Mauri

Mauri (people)

The Mauri were an ancient Berber people inhabiting the territory of modern Algeria and Morocco. Much of that territory was annexed to the Roman empire in 44 AD, as the province of Mauretania...

of Morocco

Morocco

Morocco , officially the Kingdom of Morocco , is a country located in North Africa. It has a population of more than 32 million and an area of 710,850 km², and also primarily administers the disputed region of the Western Sahara...

and the Numidians

Numidians

The Numidians were Berber tribes who lived in Numidia, in Algeria east of Constantine and in part of Tunisia. The Numidians were one of the earliest natives to trade with the settlers of Carthage. As Carthage grew, the relationship with the Numidians blossomed. Carthage's military used the Numidian...

of central and eastern Algeria

Algeria

Algeria , officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria , also formally referred to as the Democratic and Popular Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of Northwest Africa with Algiers as its capital.In terms of land area, it is the largest country in Africa and the Arab...

and Tunis

Tunis

Tunis is the capital of both the Tunisian Republic and the Tunis Governorate. It is Tunisia's largest city, with a population of 728,453 as of 2004; the greater metropolitan area holds some 2,412,500 inhabitants....

. They were also nomadic, having the horse, and occupied the arid pastures and desert, like the Gaetuli

Gaetuli

Gaetuli was the Romanised name of an ancient Berber tribe inhabiting Getulia, covering the desert region south of the Atlas Mountains, bordering the Sahara. Other sources place Getulia in pre-Roman times along the Mediterranean coasts of what is now Algeria and Tunisia, and north of the Atlas...

. Berber desert nomads were typically in conflict with Berber coastal agriculturalists.

The Phoenicians were seamen of the Mediterranean. They were in constant search for valuable metals like copper, gold, tin, and lead. Soon they began to populate the North African coast with settlements, trading and mixing with the native Berber population. In 814 BCE, Phoenicians from Tyre established the city of Carthage

Carthage

Carthage , implying it was a 'new Tyre') is a major urban centre that has existed for nearly 3,000 years on the Gulf of Tunis, developing from a Phoenician colony of the 1st millennium BC...

. By 600 BCE, Carthage had become a major trading entity and power in the Mediterranean, largely through trade with tropical Africa. Carthage's prosperity fostered the growth of the Berber kingdoms, Numidia

Numidia

Numidia was an ancient Berber kingdom in part of present-day Eastern Algeria and Western Tunisia in North Africa. It is known today as the Chawi-land, the land of the Chawi people , the direct descendants of the historical Numidians or the Massyles The kingdom began as a sovereign state and later...

and Mauretania

Mauretania

Mauretania is a part of the historical Ancient Libyan land in North Africa. It corresponds to present day Morocco and a part of western Algeria...

. Around 500 BCE, Carthage provided a strong impetus for trade with sub-Saharan Africa. Berber middlemen, who had maintained contacts with sub-Saharan Africa since the desert had desiccated, utilized pack animals to transfer products from oasis to oasis. Danger lurked from the Garamantes

Garamantes

The Garamantes were a Saharan people who used an elaborate underground irrigation system, and founded a prosperous Berber kingdom in the Fezzan area of modern-day Libya, in the Sahara desert. They were a local power in the Sahara between 500 BC and 700 AD.There is little textual information about...

of Fez

Fes

Fes or Fez is the second largest city of Morocco, after Casablanca, with a population of approximately 1 million . It is the capital of the Fès-Boulemane region....

, who raided caravans. Salt and metal goods were traded for gold, slaves, beads, and ivory.

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

and Romans

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

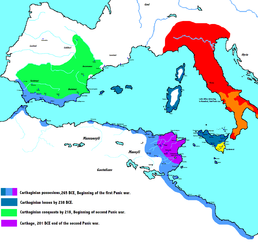

. Carthage fought three wars with Rome: the First Punic War

First Punic War

The First Punic War was the first of three wars fought between Ancient Carthage and the Roman Republic. For 23 years, the two powers struggled for supremacy in the western Mediterranean Sea, primarily on the Mediterranean island of Sicily and its surrounding waters but also to a lesser extent in...

(264 to 241 BCE), over Sicily

Sicily

Sicily is a region of Italy, and is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Along with the surrounding minor islands, it constitutes an autonomous region of Italy, the Regione Autonoma Siciliana Sicily has a rich and unique culture, especially with regard to the arts, music, literature,...

; the Second Punic War

Second Punic War

The Second Punic War, also referred to as The Hannibalic War and The War Against Hannibal, lasted from 218 to 201 BC and involved combatants in the western and eastern Mediterranean. This was the second major war between Carthage and the Roman Republic, with the participation of the Berbers on...

(218 to 201 BCE), in which Hannibal invaded Europe; and the Third Punic War

Third Punic War

The Third Punic War was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between the former Phoenician colony of Carthage, and the Roman Republic...

(149 to 146 BCE). Carthage lost the first two wars, and in the third it was destroyed, becoming the Roman province of Africa, with the Berber Kingdom of Numidia assisting Rome. The Roman province of Africa became a major agricultural supplier of wheat, olives, and olive oil

Olive oil

Olive oil is an oil obtained from the olive , a traditional tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin. It is commonly used in cooking, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and soaps and as a fuel for traditional oil lamps...

to imperial Rome via exorbitant taxation. Two centuries later, Rome brought the Berber kingdoms of Numidia and Mauretania under its authority. In the 420s CE, Vandals

Vandals

The Vandals were an East Germanic tribe that entered the late Roman Empire during the 5th century. The Vandals under king Genseric entered Africa in 429 and by 439 established a kingdom which included the Roman Africa province, besides the islands of Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia and the Balearics....

invaded North Africa and Rome lost her territories. The Berber kingdoms subsequently regained their independence.

Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

gained a foothold in Africa at Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

in the 1st century CE and spread to northwest Africa. By 313 CE, with the Edict of Milan

Edict of Milan

The Edict of Milan was a letter signed by emperors Constantine I and Licinius that proclaimed religious toleration in the Roman Empire...

, all of Roman North Africa

North Africa

North Africa or Northern Africa is the northernmost region of the African continent, linked by the Sahara to Sub-Saharan Africa. Geopolitically, the United Nations definition of Northern Africa includes eight countries or territories; Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, South Sudan, Sudan, Tunisia, and...

was Christian. Egyptians adopted Monophysite Christianity and formed the independent Coptic Church. Berbers adopted Donatist

Donatist

Donatism was a Christian sect within the Roman province of Africa that flourished in the fourth and fifth centuries. It had its roots in the social pressures among the long-established Christian community of Roman North Africa , during the persecutions of Christians under Diocletian...

Christianity. Both groups refused to accept the authority of the Roman Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

.

Role of the Berbers

As Carthaginian power grew; its impact on the indigenous population increased dramatically. BerberBerber people

Berbers are the indigenous peoples of North Africa west of the Nile Valley. They are continuously distributed from the Atlantic to the Siwa oasis, in Egypt, and from the Mediterranean to the Niger River. Historically they spoke the Berber language or varieties of it, which together form a branch...

civilization was already at a stage in which agriculture

Agriculture

Agriculture is the cultivation of animals, plants, fungi and other life forms for food, fiber, and other products used to sustain life. Agriculture was the key implement in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that nurtured the...

, manufacturing, trade, and political organization supported several states. Trade links between Carthage and the Berbers in the interior grew, but territorial expansion also resulted in the enslavement or military recruitment of some Berbers and in the extraction of tribute from others. By the early 4th century BC, Berbers formed one of the largest element, with Gauls, of the Carthaginian army. In the Revolt of the Mercenaries, Berber soldiers participated from 241 to 238 BC after being unpaid following the defeat of Carthage in the First Punic War

First Punic War

The First Punic War was the first of three wars fought between Ancient Carthage and the Roman Republic. For 23 years, the two powers struggled for supremacy in the western Mediterranean Sea, primarily on the Mediterranean island of Sicily and its surrounding waters but also to a lesser extent in...

. Berbers succeeded in obtaining control of much of Carthage's North African territory, and they minted coins bearing the name Libyan, used in Greek to describe natives of North Africa. The Carthaginian state declined because of successive defeats by the Romans in the Punic Wars

Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage from 264 B.C.E. to 146 B.C.E. At the time, they were probably the largest wars that had ever taken place...

; in 146 BC the city of Carthage was destroyed. As Carthaginian power waned, the influence of Berber leaders in the hinterland grew. By the 2nd century BC, several large but loosely administered Berber kingdoms had emerged. Two of them were established in Numidia

Numidia

Numidia was an ancient Berber kingdom in part of present-day Eastern Algeria and Western Tunisia in North Africa. It is known today as the Chawi-land, the land of the Chawi people , the direct descendants of the historical Numidians or the Massyles The kingdom began as a sovereign state and later...

, behind the coastal areas controlled by Carthage. West of Numidia lay Mauretania, which extended across the Moulouya River

Moulouya River

The Moulouya River is a 520 km-long river in Morocco. Its sources are located in the Middle Atlas. It empties into the Mediterranean Sea near Saidia, in Northeast Morocco at about . Water level in the river often fluctuates. The river is used for irrigation...

in Morocco to the Atlantic Ocean. The high point of Berber civilization, unequaled until the coming of the Almohad

Almohad

The Almohad Dynasty , was a Moroccan Berber-Muslim dynasty founded in the 12th century that established a Berber state in Tinmel in the Atlas Mountains in roughly 1120.The movement was started by Ibn Tumart in the Masmuda tribe, followed by Abd al-Mu'min al-Gumi between 1130 and his...

s and Almoravids more than a millennium later, was reached during the reign of Masinissa

Masinissa

Masinissa — also spelled Massinissa and Massena — was the first King of Numidia, an ancient North African nation of ancient Libyan tribes. As a successful general, Masinissa fought in the Second Punic War , first against the Romans as an ally of Carthage an later switching sides when he saw which...

in the 2nd century BC. After Masinissa's death in 148 BC, the Berber kingdoms were divided and reunited several times. Masinissa's line survived until AD 24, when the remaining Berber territory was annexed to the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

.

Somalia

Somali people

Somalis are an ethnic group located in the Horn of Africa, also known as the Somali Peninsula. The overwhelming majority of Somalis speak the Somali language, which is part of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family...

were an important link in the Horn of Africa

Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa is a peninsula in East Africa that juts hundreds of kilometers into the Arabian Sea and lies along the southern side of the Gulf of Aden. It is the easternmost projection of the African continent...

connecting the region's commerce with the rest of the ancient world. Somali sailors and merchants were the main suppliers of frankincense

Frankincense

Frankincense, also called olibanum , is an aromatic resin obtained from trees of the genus Boswellia, particularly Boswellia sacra, B. carteri, B. thurifera, B. frereana, and B. bhaw-dajiana...

, myrrh

Myrrh

Myrrh is the aromatic oleoresin of a number of small, thorny tree species of the genus Commiphora, which grow in dry, stony soil. An oleoresin is a natural blend of an essential oil and a resin. Myrrh resin is a natural gum....

and spices, all of which were valuable luxuries to the Ancient Egyptians, Phoenicians, Mycenaeans

Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean Greece was a cultural period of Bronze Age Greece taking its name from the archaeological site of Mycenae in northeastern Argolis, in the Peloponnese of southern Greece. Athens, Pylos, Thebes, and Tiryns are also important Mycenaean sites...

and Babylonians.

In the classical era

Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity is a broad term for a long period of cultural history centered on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient Rome, collectively known as the Greco-Roman world...

, several flourishing Somali city-states such as Opone, Mosyllon

Cape Guardafui

Cape Guardafui , also known as Ras Asir and historically as Aromata promontorium, is a headland in the northeastern Bari province of Somalia. Located in the autonomous Puntland region, it forms the geographical apex of the region commonly referred to as the Horn of Africa.-Location:Cape Guardafui...

and Malao

Berbera

Berbera is a city and seat of Berbera District in Somaliland, a self-proclaimed Independent Republic with de facto control over its own territory, which is recognized by the international community and the Somali Government as a part of Somalia...

competed with the Sabaeans, Parthia

Parthia

Parthia is a region of north-eastern Iran, best known for having been the political and cultural base of the Arsacid dynasty, rulers of the Parthian Empire....

ns and Axumites for the rich Indo

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

-Greco-Roman trade.

Roman North Africa

Trajan

Trajan , was Roman Emperor from 98 to 117 AD. Born into a non-patrician family in the province of Hispania Baetica, in Spain Trajan rose to prominence during the reign of emperor Domitian. Serving as a legatus legionis in Hispania Tarraconensis, in Spain, in 89 Trajan supported the emperor against...

established a frontier in the south by encircling the Aurès and Nemencha mountains and building a line of forts from Vescera (modern Biskra

Biskra

Biskra is the capital city of Biskra province, Algeria. In 2007, its population was recorded as 207,987.During Roman times the town was called Vescera, though this may have been simply a Latin transliteration of the native name. Around 200 AD under Septimius Severus' reign, it was seized by the...

) to Ad Majores (Hennchir Besseriani, southeast of Biskra). The defensive line extended at least as far as Castellum Dimmidi (modern Messaad, southwest of Biskra), Roman Algeria's southernmost fort. Romans settled and developed the area around Sitifis (modern Sétif

Sétif

Sétif |Colonia]]) is a town in northeastern Algeria. It is the capital of Sétif Province and it has a population of 239,195 inhabitants as of the 1998 census. Setif is located to the east of Algiers and is the second most important Wilaya after the country's capital. It is 1,096 meters above sea...

) in the 2nd century, but farther west the influence of Rome did not extend beyond the coast and principal military roads until much later.

The Roman military presence of North Africa was relatively small, consisting of about 28,000 troops and auxiliaries in Numidia

Numidia

Numidia was an ancient Berber kingdom in part of present-day Eastern Algeria and Western Tunisia in North Africa. It is known today as the Chawi-land, the land of the Chawi people , the direct descendants of the historical Numidians or the Massyles The kingdom began as a sovereign state and later...

and the two Mauretania

Mauretania

Mauretania is a part of the historical Ancient Libyan land in North Africa. It corresponds to present day Morocco and a part of western Algeria...

n provinces. Starting in the 2nd century AD, these garrisons were manned mostly by local inhabitants.

Aside from Carthage, urbanization in North Africa came in part with the establishment of settlements of veterans under the Roman emperors Claudius

Claudius

Claudius , was Roman Emperor from 41 to 54. A member of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, he was the son of Drusus and Antonia Minor. He was born at Lugdunum in Gaul and was the first Roman Emperor to be born outside Italy...

, Nerva, and Trajan. In Algeria such settlements included Tipasa

Tipasa

Tipaza is a Berber-speaking town on the coast of Algeria, capital of the Tipaza province. The modern town, founded in 1857, is remarkable chiefly for its sandy beach, and ancient ruins.-Ancient history:...

, Cuicul or Curculum (modern Djemila

Djemila

Djémila is a mountain village in Algeria, near the northern coast east of Algiers, where some of the best preserved Berbero-Roman ruins in North Africa are found...

, northeast of Sétif), Thamugadi (modern Timgad

Timgad

Timgad , called Thamugas or Tamugadi in old Berber) was a Roman colonial town in the Aures mountain- numidia Algeria founded by the Emperor Trajan around 100 AD. The full name of the town was Colonia Marciana Ulpia Traiana Thamugadi...

, southeast of Sétif), and Sitifis (modern Setif

Sétif

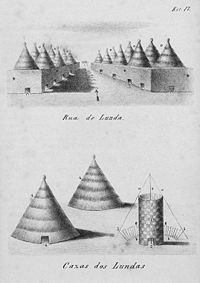

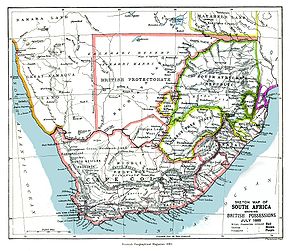

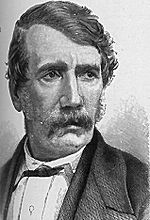

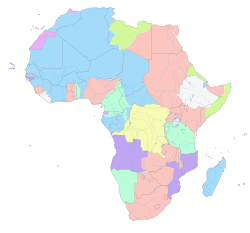

Sétif |Colonia]]) is a town in northeastern Algeria. It is the capital of Sétif Province and it has a population of 239,195 inhabitants as of the 1998 census. Setif is located to the east of Algiers and is the second most important Wilaya after the country's capital. It is 1,096 meters above sea...