Battle of Ulundi

Encyclopedia

The Battle of Ulundi took place at the Zulu

capital of Ulundi on 4 July 1879 and was the last major battle of the Anglo-Zulu War

. The British army finally broke the military power of the Zulu nation

by defeating the main Zulu army and immediately afterwards capturing and razing the capital of Zululand, the royal kraal of Ulundi.

in January over Chelmsford's main column and the consequent defeat of the first invasion of Zululand, the British found themselves forced to launch a new invasion of Zululand

. In April 1879 despite recent battles at Kambula

and Gingindlovu

which had resulted in serious losses for the Zulus the British were back at their starting point. News of the defeat at Isandlwana

had hit Britain hard. In response, a flood of reinforcements had arrived in Natal with which Chelmsford prepared a second invasion of Zululand. Lord Chelmsford was aware by mid June that Sir Garnet Wolseley had superseded his command of the British forces. Chelmsford was ordered by Her Majesty's Government to "...submit and subordinate your plans to his control." Chelmsford ignored this and various peace offers from Cetshwayo in order to strike while the Zulu were still recovering from their defeats and to attempt to regain his reputation before Wolseley could remove him from command of the army.

For his renewed offensive Chelmsford's overall strength was increased to 25,000. However, the very size of the force overwhelmed the supply and transport capacity of Natal and Chelmsford would have to utilize a number of troops that could be sustained in the field. In the event, for his main column, he fielded 2 cavalry regiments, 5 batteries of artillery and 12 infantry battalions, amounting to 1,000 regular cavalry, 9,000 regular infantry and a further 7,000 men with 24 guns, including the first ever British Army Gatling battery. The lumbering supply train consisted of 600 wagons, 8,000 oxen and 1,000 mules. The structure of the force was reorganised; Colonel Evelyn Wood’s No. 4 column became the flying column

, Colonel Charles Pearson was relieved of command by Major General Henry Crealock and his No.1 column became the 1st Division and Major General Newdigate was given command of the new 2nd Division, accompanied by Lord Chelmsford himself.

All through April and May there was much to and fro maneuvering by the British particularly with supply and transport. Eventually, on 3 June, the main thrust of the second invasion began its slow advance on Ulundi. The 1st division was to advance along the coast belt supporting 2nd division, which with Wood's flying column, an independent unit, was to march on Ulundi from Rorke’s Drift and Kambula. Still hoping for an end to hostilities, Cetshwayo refrained from attacking the extended and vulnerable supply lines and the British advance was unopposed. As the force advanced Cetshwayo

All through April and May there was much to and fro maneuvering by the British particularly with supply and transport. Eventually, on 3 June, the main thrust of the second invasion began its slow advance on Ulundi. The 1st division was to advance along the coast belt supporting 2nd division, which with Wood's flying column, an independent unit, was to march on Ulundi from Rorke’s Drift and Kambula. Still hoping for an end to hostilities, Cetshwayo refrained from attacking the extended and vulnerable supply lines and the British advance was unopposed. As the force advanced Cetshwayo

dispatched envoys from Ulundi to the British. These envoys reached Chelmsford on 4 June with the message that Cetshwayo wished to know what terms would be acceptable to cease hostilities. Chelmsford sent a Zulu-speaking Dutch trader back with their terms in writing.

On the evening of 6 June jittery British troops and artillery in laager at Fort Newdigate opened fire on an arriving piquet company of Royal Engineers commanded by Lt. Chard, wounding one and killing two horses. By the 16th the slow advance was quickened by the news that Wolseley was on his way to Natal to take command. On the 17th a depot named Fort Marshall was established - not far from Isandlhwana. On 28 June Chelmsford’s column was a mere 17 miles away from Ulundi and had established the supply depots of Fort Newdigate, Fort Napoleon and Port Durnford when Sir Garnet Wolseley arrived in Cape Town. Wolseley had cabled Chelmsford ordering him not to undertake any serious actions on the 23rd but the message was only received through a galloper on this day. Chelmsford had no intention of letting Wolseley stop him from making a last effort to restore his reputation and did not reply. A second message was sent on the 30th reading:

"Concentrate your force immediately and keep it concentrated. Undertake no serious operations with detached bodies of troops. Acknowledge receipt of this message at once and flash back your latest moves. I am astonished at not hearing from you"

Wolseley, straining to assert command over Chelmsford, tried to join 1st Division, lagging along the coast behind the main advance. A final message was sent to Chelmsford explaining that he would be joining 1st Division, and that their location was where Chelmsford should retreat if he was compelled to. High seas prevented Wolseley landing at Port Durnford and he had to take the road. At the very time Wolseley was riding north from Durban, Chelmsford was preparing to engage the enemy. Wolseley's efforts to reach the front had been in vain.

On the same day the first cable was received, Cetshwayo’s representatives again appeared. A previous reply to Chelmsford’s demands had apparently never reached the British force, but now these envoys bore some of what the British commander had demanded – oxen, a promise of guns and gift of elephant

On the same day the first cable was received, Cetshwayo’s representatives again appeared. A previous reply to Chelmsford’s demands had apparently never reached the British force, but now these envoys bore some of what the British commander had demanded – oxen, a promise of guns and gift of elephant

tusks. The peace was rejected as the terms had not been fully met and Chelmsford turned the envoys away without accepting the elephant tusks and informed them that the advance would only be delayed one day to allow the Zulus to surrender one regiment of their army. The redcoats were now visible from the Royal Kraal and a dismayed Cetshwayo was desperate to end the hostilities. With the invading enemy in sight, he knew no Zulu regiment would surrender so Cetshwayo sent a further hundred white oxen from his own herd along with Prince Napoleon’s

sword, which the Zulu had taken 1 June, 1879 in the skirmish in which the Prince was killed. The Zulu

umCijo regiment, guarding the approaches to the White Umfolozi River

where the British were camped, refused to let the oxen pass deeming it a useless gesture, saying, as it was impossible to meet all Chelmsford's demands, fighting was inevitable. The irate telegram from Wolseley issued on 30 June now reached Chelmsford, and with only 5 miles between him and a redemptive victory, it was ignored.

on the opposite bank. This incident had placed the entire reconnaissance in grave danger, but Buller’s alertness and leadership saved them from annihilation. Chelmsford was now convinced the Zulus wanted to fight and replied to Wolseley’s third message, informing him that he would indeed retreat to 1st division if the need arose, and that he would be attacking the Zulus the next day.

That evening Chelmsford issued his orders. The British, having learned a bitter lesson at Isandlwana, would take no chances meeting the Zulu army in the open with their normal line of battle such as the 'Thin Red Line

' of fame. Their advance would begin at first light, prior to forming his infantry into a large hollow square

, with mounted troops covering the sides and rear. Neither wagon laagers nor trenches would be used, to convince both the Zulus and critics that a British square could “beat them fairly in the open”.

At 6 a.m. Buller led out an advance guard of mounted troops and South African irregulars, which after Buller had secured upper drift was followed by the infantry being led by the experienced Flying Column battalions. By 7:30 a.m. the column had cleared the rough ground on the other side of the riverbank and their square (in reality a rectangular shape) was formed. At 8:45 a.m.the Zulu engaged the cavalry on the right and left which slowly retired and passed into the square. The leading face was made up of five companies of the 80th Regiment in four ranks, with two Gatling gun

s in the centres, two 9-pounders on the left flank and two 7-pounders on the right. The 90th Light Infantry

with four companies of the 94th Regiment

made up the left face with two more 7-pounders. On the right face were the 1st Battalion of the 13th Light Infantry, four companies of the 58th Regiment

, two 7-pounders and two 9-pounders. The rear face was composed of two companies of the 94th Regiment, two companies of the 2nd Battalion of the 21st Regiment (Royal Scots Fusiliers). Within the square were headquarters staff, No. 5 company of the Royal Engineers (led by Lieutenant John Chard

, of Rorke's Drift

fame), the 2nd Native Natal Contingent, fifty wagons and carts with reserve ammunition and hospital wagons. Buller’s horsemen protected the front and both flanks of the square. A rearguard of two squadrons of the 17th Lancers

and a troop of Natal Native Horse followed.

Battalions with Regimental Colours now uncased them; the band of 13th Light Infantry struck up and the 5,317-man strong ‘living laager’ began its measured advance across the plain. No Zulus in any numbers had been sighted by 8 a.m., so the Frontier Light Horse

were sent forth to provoke the enemy. As they rode across the Mbilane stream, the entire Zulu inGobamkhosi regiment rose out of the grass in front of them, followed by regiment after regiment rising up all around them. The Zulu Army under the command of umNtwana Ziwedu kaMpande, around 12,000 to 15,000 strong, now stood in horseshoe encircling the north, east and southern sides of the square. A Zulu reserve force was also poised to complete the circle. The Zulu ranks stood hammering the ground with their feet and drumming shield with assegai

, made up both of veterans and novices with varying degrees of confidence. The mounted troops by the stream opened fire from the saddle in an attempt to trigger a premature charge before wheeling back to gallop through the gaps made in the infantry lines for them. As the cavalry cleared their front at about 9 a.m., the four ranks of the infantry with front two kneeling, opened fire at 2,000 yards into the advancing Zulu ranks. The pace of the advance quickened and the range closed between the British lines and the Zulus. The British were ready and the Zulu troops faced concentrated fire. Zulu regiments had to charge forward directly into massed rifle fire, non-stop fire from the Gatling guns and the artillery

firing canister shot

at point-blank range.

Charges were made by the Zulus, in an attempt to get within close range, but they could not prevail against the British fire. There were a number of casualties within the square to Zulu marksmen, but the British firing did not waver and no warrior was able to get within 30 yards of the British ranks. The Zulu reserve force now rose and charged against the south-west corner of the square. Nine-pounders ploughed chunks out of this body while the infantry opened fire. The speed of the charge made it seem as if the Zulu reserves would get close enough to engage in hand-to-hand combat but no warrior reached the British ranks. Chelmsford ordered the cavalry to mount, and the 17th Lancers

, 1st King’s Dragoon Guards

, colonial cavalry, Native Horse and 2nd Natal Native Contingent

charged the now fleeing Zulus. Towards the high ground the Zulus fled with cavalry at their heels and shells falling ahead of them. The Lancers were checked at the Mbilane stream by the fire of a concealed party of Zulus, causing several casualties before the Lancers overcame the resistance. The pursuit continued until not a live Zulu remained on the Mahlabatini plain, with members of the Natal Native Horse, Natal Native Contingent and Wood's Irregulars slaughtering the Zulu wounded, a vengeance for the bloodshed at Isandlwana.

After half an hour of concentrated fire from the artillery, the Gatling Guns and the thousands of British rifles, Zulu military power was broken. British casualties were ten killed and eighty-seven wounded, while nearly five hundred Zulu dead were counted around the square, with another 1000 or more wounded. Chelmsford ordered the Royal Kraal of Ulundi to be burnt – the capital of Zululand burned for days. Chelmsford turned over command to Wolseley on 15 July at the fort at St. Paul's leaving for home on the 17th. Chelmsford had partially salvaged his reputation and received a Knight Grand Cross of Bath, largely because of Ulundi, however, he was severely criticized by the Horse Guards investigation and he would never serve in the field again.

After half an hour of concentrated fire from the artillery, the Gatling Guns and the thousands of British rifles, Zulu military power was broken. British casualties were ten killed and eighty-seven wounded, while nearly five hundred Zulu dead were counted around the square, with another 1000 or more wounded. Chelmsford ordered the Royal Kraal of Ulundi to be burnt – the capital of Zululand burned for days. Chelmsford turned over command to Wolseley on 15 July at the fort at St. Paul's leaving for home on the 17th. Chelmsford had partially salvaged his reputation and received a Knight Grand Cross of Bath, largely because of Ulundi, however, he was severely criticized by the Horse Guards investigation and he would never serve in the field again.

Cetshwayo had been sheltered in a village since 3 July and fled upon hearing news of the defeat at Ulundi. The British forces were dispersed around Zululand in the hunt for Cetshwayo, burning numerous kraals in a vain attempt to get his Zulu subjects to give him up and fighting the final small battle to defeat the remaining hostile battalions. He was finally captured on 28 August by soldiers under Wolseley's command at kraal in the middle of Ngome forest. He was exiled to London, where he would be held prisoner for three years. Wolseley, having replaced both Chelmsford and Bartle Frere, swiftly divided up Zululand into thirteen districts, installing compliant chiefs in each so that the kingdom could no longer unite under one rule. Cetshwayo was restored to the throne of the partitioned Zulu kingdom in January 1883 shortly before his death in 1884.

Zulu Kingdom

The Zulu Kingdom, sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire or, rather imprecisely, Zululand, was a monarchy in Southern Africa that extended along the coast of the Indian Ocean from the Tugela River in the south to Pongola River in the north....

capital of Ulundi on 4 July 1879 and was the last major battle of the Anglo-Zulu War

Anglo-Zulu War

The Anglo-Zulu War was fought in 1879 between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom.Following the imperialist scheme by which Lord Carnarvon had successfully brought about federation in Canada, it was thought that a similar plan might succeed with the various African kingdoms, tribal areas and...

. The British army finally broke the military power of the Zulu nation

Zulu Kingdom

The Zulu Kingdom, sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire or, rather imprecisely, Zululand, was a monarchy in Southern Africa that extended along the coast of the Indian Ocean from the Tugela River in the south to Pongola River in the north....

by defeating the main Zulu army and immediately afterwards capturing and razing the capital of Zululand, the royal kraal of Ulundi.

Prelude

As a result of the decisive Zulu victory at the battle of IsandlwanaBattle of Isandlwana

The Battle of Isandlwana on 22 January 1879 was the first major encounter in the Anglo-Zulu War between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom...

in January over Chelmsford's main column and the consequent defeat of the first invasion of Zululand, the British found themselves forced to launch a new invasion of Zululand

Zulu Kingdom

The Zulu Kingdom, sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire or, rather imprecisely, Zululand, was a monarchy in Southern Africa that extended along the coast of the Indian Ocean from the Tugela River in the south to Pongola River in the north....

. In April 1879 despite recent battles at Kambula

Battle of Kambula

Battle of Kambula took place in 1879, during the Anglo-Zulu War when a Zulu Army attacked the British camp at Kambula. It resulted in a decisive Zulu defeat and is considered to be the turning point of the Anglo-Zulu War.-Prelude:...

and Gingindlovu

Battle of Gingindlovu

The Battle of Gingindlovu was fought on 2 April 1879 between a British relief column sent to break the Siege of Eshowe and a Zulu impi of king Cetshwayo.-Prelude:...

which had resulted in serious losses for the Zulus the British were back at their starting point. News of the defeat at Isandlwana

Battle of Isandlwana

The Battle of Isandlwana on 22 January 1879 was the first major encounter in the Anglo-Zulu War between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom...

had hit Britain hard. In response, a flood of reinforcements had arrived in Natal with which Chelmsford prepared a second invasion of Zululand. Lord Chelmsford was aware by mid June that Sir Garnet Wolseley had superseded his command of the British forces. Chelmsford was ordered by Her Majesty's Government to "...submit and subordinate your plans to his control." Chelmsford ignored this and various peace offers from Cetshwayo in order to strike while the Zulu were still recovering from their defeats and to attempt to regain his reputation before Wolseley could remove him from command of the army.

For his renewed offensive Chelmsford's overall strength was increased to 25,000. However, the very size of the force overwhelmed the supply and transport capacity of Natal and Chelmsford would have to utilize a number of troops that could be sustained in the field. In the event, for his main column, he fielded 2 cavalry regiments, 5 batteries of artillery and 12 infantry battalions, amounting to 1,000 regular cavalry, 9,000 regular infantry and a further 7,000 men with 24 guns, including the first ever British Army Gatling battery. The lumbering supply train consisted of 600 wagons, 8,000 oxen and 1,000 mules. The structure of the force was reorganised; Colonel Evelyn Wood’s No. 4 column became the flying column

Flying column

A flying column is a small, independent, military land unit capable of rapid mobility and usually composed of all arms. It is often an ad hoc unit, formed during the course of operations....

, Colonel Charles Pearson was relieved of command by Major General Henry Crealock and his No.1 column became the 1st Division and Major General Newdigate was given command of the new 2nd Division, accompanied by Lord Chelmsford himself.

Invasion

Cetshwayo

Cetshwayo kaMpande was the King of the Zulu Kingdom from 1872 to 1879 and their leader during the Anglo-Zulu War . His name has been transliterated as Cetawayo, Cetewayo, Cetywajo and Ketchwayo.- Early life :...

dispatched envoys from Ulundi to the British. These envoys reached Chelmsford on 4 June with the message that Cetshwayo wished to know what terms would be acceptable to cease hostilities. Chelmsford sent a Zulu-speaking Dutch trader back with their terms in writing.

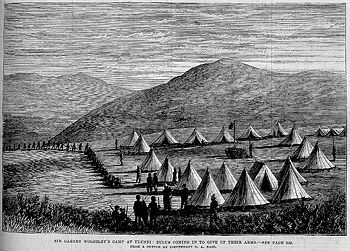

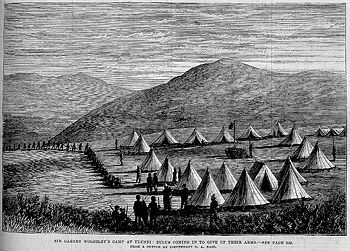

On the evening of 6 June jittery British troops and artillery in laager at Fort Newdigate opened fire on an arriving piquet company of Royal Engineers commanded by Lt. Chard, wounding one and killing two horses. By the 16th the slow advance was quickened by the news that Wolseley was on his way to Natal to take command. On the 17th a depot named Fort Marshall was established - not far from Isandlhwana. On 28 June Chelmsford’s column was a mere 17 miles away from Ulundi and had established the supply depots of Fort Newdigate, Fort Napoleon and Port Durnford when Sir Garnet Wolseley arrived in Cape Town. Wolseley had cabled Chelmsford ordering him not to undertake any serious actions on the 23rd but the message was only received through a galloper on this day. Chelmsford had no intention of letting Wolseley stop him from making a last effort to restore his reputation and did not reply. A second message was sent on the 30th reading:

"Concentrate your force immediately and keep it concentrated. Undertake no serious operations with detached bodies of troops. Acknowledge receipt of this message at once and flash back your latest moves. I am astonished at not hearing from you"

Wolseley, straining to assert command over Chelmsford, tried to join 1st Division, lagging along the coast behind the main advance. A final message was sent to Chelmsford explaining that he would be joining 1st Division, and that their location was where Chelmsford should retreat if he was compelled to. High seas prevented Wolseley landing at Port Durnford and he had to take the road. At the very time Wolseley was riding north from Durban, Chelmsford was preparing to engage the enemy. Wolseley's efforts to reach the front had been in vain.

Elephant

Elephants are large land mammals in two extant genera of the family Elephantidae: Elephas and Loxodonta, with the third genus Mammuthus extinct...

tusks. The peace was rejected as the terms had not been fully met and Chelmsford turned the envoys away without accepting the elephant tusks and informed them that the advance would only be delayed one day to allow the Zulus to surrender one regiment of their army. The redcoats were now visible from the Royal Kraal and a dismayed Cetshwayo was desperate to end the hostilities. With the invading enemy in sight, he knew no Zulu regiment would surrender so Cetshwayo sent a further hundred white oxen from his own herd along with Prince Napoleon’s

Napoléon Eugène, Prince Imperial

Napoléon, Prince Imperial, , Prince Imperial, Fils de France, was the only child of Emperor Napoleon III of France and his Empress consort Eugénie de Montijo...

sword, which the Zulu had taken 1 June, 1879 in the skirmish in which the Prince was killed. The Zulu

Zulu Kingdom

The Zulu Kingdom, sometimes referred to as the Zulu Empire or, rather imprecisely, Zululand, was a monarchy in Southern Africa that extended along the coast of the Indian Ocean from the Tugela River in the south to Pongola River in the north....

umCijo regiment, guarding the approaches to the White Umfolozi River

White Umfolozi River

The White Umfolozi River originates just south of Vryheid, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa and joins the Black Umfolozi River at to form the Umfolozi River, before it flows east towards the Indian Ocean.- See also :* List of rivers of South Africa...

where the British were camped, refused to let the oxen pass deeming it a useless gesture, saying, as it was impossible to meet all Chelmsford's demands, fighting was inevitable. The irate telegram from Wolseley issued on 30 June now reached Chelmsford, and with only 5 miles between him and a redemptive victory, it was ignored.

The battle

On 3 July, with negotiations having broken down, Colonel Buller led a cavalry force across the river to reconnoitre the ground beyond the river. A party of Zulus were seen herding goats near the Mbilane stream and troopers moved to round them up. On a hunch, Buller bellowed an order for them to stop and prepare to fire from the saddle. His instinct proved right, for 3,000 Zulus rose from the long grass at that moment and fired a fusillade, before charging forth. Three troopers were shot dead and Buller ordered his men to retire. As they dashed back to the river, Baker’s Horse who had been scouting further across took up position and gave covering fire for the river crossing. Their crossing in turn was covered by the Transvaal RangersTransvaal Rangers

Raafs Horse was an irregular unit raised by Pieter Raaf with a strength of approximately 140. The Transvaal Rangers enlisted both European and Coloured personnel in its ranks, and recruited large numbers from the Kimberley diamond fields...

on the opposite bank. This incident had placed the entire reconnaissance in grave danger, but Buller’s alertness and leadership saved them from annihilation. Chelmsford was now convinced the Zulus wanted to fight and replied to Wolseley’s third message, informing him that he would indeed retreat to 1st division if the need arose, and that he would be attacking the Zulus the next day.

That evening Chelmsford issued his orders. The British, having learned a bitter lesson at Isandlwana, would take no chances meeting the Zulu army in the open with their normal line of battle such as the 'Thin Red Line

The Thin Red Line (Battle of Balaclava)

The Thin Red Line was a military action by the Sutherland Highlanders red-coated 93rd Regiment at the Battle of Balaclava on October 25, 1854, during the Crimean War. In this incident the 93rd aided by a small force of Royal Marines and some Turkish infantrymen, led by Sir Colin Campbell, routed a...

' of fame. Their advance would begin at first light, prior to forming his infantry into a large hollow square

Infantry square

An infantry square is a combat formation an infantry unit forms in close order when threatened with cavalry attack.-Very early history:The formation was described by Plutarch and used by the Romans, and was developed from an earlier circular formation...

, with mounted troops covering the sides and rear. Neither wagon laagers nor trenches would be used, to convince both the Zulus and critics that a British square could “beat them fairly in the open”.

At 6 a.m. Buller led out an advance guard of mounted troops and South African irregulars, which after Buller had secured upper drift was followed by the infantry being led by the experienced Flying Column battalions. By 7:30 a.m. the column had cleared the rough ground on the other side of the riverbank and their square (in reality a rectangular shape) was formed. At 8:45 a.m.the Zulu engaged the cavalry on the right and left which slowly retired and passed into the square. The leading face was made up of five companies of the 80th Regiment in four ranks, with two Gatling gun

Gatling gun

The Gatling gun is one of the best known early rapid-fire weapons and a forerunner of the modern machine gun. It is well known for its use by the Union forces during the American Civil War in the 1860s, which was the first time it was employed in combat...

s in the centres, two 9-pounders on the left flank and two 7-pounders on the right. The 90th Light Infantry

90th Regiment of Foot

Three regiments of the British Army have been numbered the 90th Regiment of Foot:*90th Regiment of Foot , raised in 1759*90th Regiment of Foot , raised in 1779*90th Regiment of Foot , raised in 1794...

with four companies of the 94th Regiment

94th Regiment of Foot

The 94th Regiment of Foot was a British Army line infantry regiment. Originally formed as the 'Scots Brigade' in 1568, for service in the Netherlands. The regiment was brought onto the English establishment, in October 1794, as the 'Scotch Brigade', renumbered as the 94th Regiment of Foot in...

made up the left face with two more 7-pounders. On the right face were the 1st Battalion of the 13th Light Infantry, four companies of the 58th Regiment

58th Regiment of Foot

Three regiments of the British Army have been numbered the 58th Regiment of Foot:* 47th Regiment of Foot, 58th Regiment of Foot, numbered as the 58th Foot in 1747 and renumbered as the 47th in 1751...

, two 7-pounders and two 9-pounders. The rear face was composed of two companies of the 94th Regiment, two companies of the 2nd Battalion of the 21st Regiment (Royal Scots Fusiliers). Within the square were headquarters staff, No. 5 company of the Royal Engineers (led by Lieutenant John Chard

John Rouse Merriott Chard

Colonel John Rouse Merriott Chard VC was a British Army officer who received the Victoria Cross for his role in the defence of Rorke's Drift in 1879....

, of Rorke's Drift

Rorke's Drift

The Battle of Rorke's Drift, also known as the Defence of Rorke's Drift, was a battle in the Anglo-Zulu War. The defence of the mission station of Rorke's Drift, under the command of Lieutenant John Chard of the Royal Engineers, immediately followed the British Army's defeat at the Battle of...

fame), the 2nd Native Natal Contingent, fifty wagons and carts with reserve ammunition and hospital wagons. Buller’s horsemen protected the front and both flanks of the square. A rearguard of two squadrons of the 17th Lancers

17th Lancers

The 17th Lancers was a cavalry regiment of the British Army, notable for its participation in the Charge of the Light Brigade in the Crimean War...

and a troop of Natal Native Horse followed.

Battalions with Regimental Colours now uncased them; the band of 13th Light Infantry struck up and the 5,317-man strong ‘living laager’ began its measured advance across the plain. No Zulus in any numbers had been sighted by 8 a.m., so the Frontier Light Horse

Frontier Light Horse

The Frontier Light Horse, a mounted unit, was raised at King William's Town, Eastern Cape Colony in 1877 by Lieutenant Frederick Carrington. It is often referred to as the Cape Frontier Light Horse.-Military service:...

were sent forth to provoke the enemy. As they rode across the Mbilane stream, the entire Zulu inGobamkhosi regiment rose out of the grass in front of them, followed by regiment after regiment rising up all around them. The Zulu Army under the command of umNtwana Ziwedu kaMpande, around 12,000 to 15,000 strong, now stood in horseshoe encircling the north, east and southern sides of the square. A Zulu reserve force was also poised to complete the circle. The Zulu ranks stood hammering the ground with their feet and drumming shield with assegai

Assegai

An assegai or assagai is a pole weapon used for throwing or hurling, usually a light spear or javelin made of wood and pointed with iron.-Iklwa:...

, made up both of veterans and novices with varying degrees of confidence. The mounted troops by the stream opened fire from the saddle in an attempt to trigger a premature charge before wheeling back to gallop through the gaps made in the infantry lines for them. As the cavalry cleared their front at about 9 a.m., the four ranks of the infantry with front two kneeling, opened fire at 2,000 yards into the advancing Zulu ranks. The pace of the advance quickened and the range closed between the British lines and the Zulus. The British were ready and the Zulu troops faced concentrated fire. Zulu regiments had to charge forward directly into massed rifle fire, non-stop fire from the Gatling guns and the artillery

Artillery

Originally applied to any group of infantry primarily armed with projectile weapons, artillery has over time become limited in meaning to refer only to those engines of war that operate by projection of munitions far beyond the range of effect of personal weapons...

firing canister shot

Canister shot

Canister shot is a kind of anti-personnel ammunition used in cannons. It was similar to the naval grapeshot, but fired smaller and more numerous balls, which did not have to punch through the wooden hull of a ship...

at point-blank range.

Charges were made by the Zulus, in an attempt to get within close range, but they could not prevail against the British fire. There were a number of casualties within the square to Zulu marksmen, but the British firing did not waver and no warrior was able to get within 30 yards of the British ranks. The Zulu reserve force now rose and charged against the south-west corner of the square. Nine-pounders ploughed chunks out of this body while the infantry opened fire. The speed of the charge made it seem as if the Zulu reserves would get close enough to engage in hand-to-hand combat but no warrior reached the British ranks. Chelmsford ordered the cavalry to mount, and the 17th Lancers

17th Lancers

The 17th Lancers was a cavalry regiment of the British Army, notable for its participation in the Charge of the Light Brigade in the Crimean War...

, 1st King’s Dragoon Guards

1st King's Dragoon Guards

The 1st King's Dragoon Guards was a cavalry regiment in the British Army. The regiment was formed in 1685 as The Queen's Regiment of Horse, named in honour of Queen Mary, consort of King James II. It was renamed The King's Own Regiment of Horse in 1714 in honour of George I...

, colonial cavalry, Native Horse and 2nd Natal Native Contingent

Natal Native Contingent

The Natal Native Contingent was a large force of auxiliary soldiers in British South Africa, forming a large portion of the defence forces of the British colony of Natal, and saw action during the 1879 Anglo-Zulu War. The NNC was originally created in 1878 out of the local black population in order...

charged the now fleeing Zulus. Towards the high ground the Zulus fled with cavalry at their heels and shells falling ahead of them. The Lancers were checked at the Mbilane stream by the fire of a concealed party of Zulus, causing several casualties before the Lancers overcame the resistance. The pursuit continued until not a live Zulu remained on the Mahlabatini plain, with members of the Natal Native Horse, Natal Native Contingent and Wood's Irregulars slaughtering the Zulu wounded, a vengeance for the bloodshed at Isandlwana.

Aftermath

Cetshwayo had been sheltered in a village since 3 July and fled upon hearing news of the defeat at Ulundi. The British forces were dispersed around Zululand in the hunt for Cetshwayo, burning numerous kraals in a vain attempt to get his Zulu subjects to give him up and fighting the final small battle to defeat the remaining hostile battalions. He was finally captured on 28 August by soldiers under Wolseley's command at kraal in the middle of Ngome forest. He was exiled to London, where he would be held prisoner for three years. Wolseley, having replaced both Chelmsford and Bartle Frere, swiftly divided up Zululand into thirteen districts, installing compliant chiefs in each so that the kingdom could no longer unite under one rule. Cetshwayo was restored to the throne of the partitioned Zulu kingdom in January 1883 shortly before his death in 1884.

External links

- http://www.britishbattles.com/zulu-war/ulundi.htm

- http://www.rorkesdriftvc.com/ulundi/

- http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_ulundi.html

- Travellers Impressions