Timeline of the American Civil Rights Movement

Encyclopedia

This is a timeline of African-American Civil Rights Movement

.

1565

1640

1654

1662

1676

1712

1739

1760

1770

1773

1774

1775

1776–1783 American Revolution

1777

1780

1787

1788

1790–1810 Manumission of slaves

1791

1793

1794

1800

1807

1808

1816

1820

1821

1822

1829

1830

1831

1833

1837

1839

1840

1842

1843

1847

1849

1850

1852

1853

1855

1856

1857

1859

1862

1863–1877 Reconstruction

1863

1864

1865

1866

1867

1868

1870

1871

1872

1873

1874

1876

1877

1879

1880

1881

1882

1884

1886

1887

1888

1890

1892

1895

1896

1898

1899

1901

1903

1904

1905

1906

1907

1908

1909

1910

1913

1914

1915

1916

1917

1918

1919

1920

1921

1923

1924

1926

1928

1929

1930

1931

1932

1934

1935

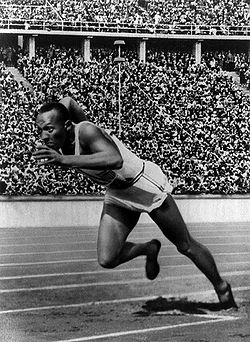

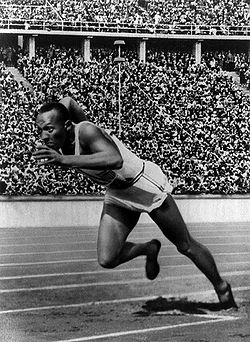

1936

1936

1937

1938

1939

1940s to 1970

1940

1941

1942

1943

1944

1945–1975 Second Reconstruction

/American Civil Rights Movement

1945

1946

1947

1948

1950

1951

1952

1953

1954

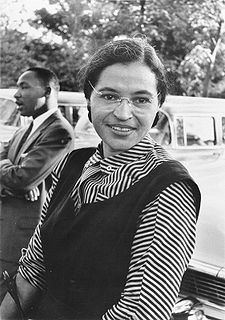

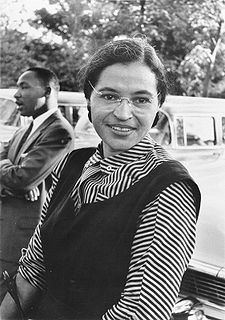

1955

1956

1957

1958

1959

1960

1961

1962

1963

1964

1965

1965

1966

1967

1968

1969

1971

1972

1973

1974

1975

1976

1977

1978

1979

1982

1983

1984

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1994

1995

1997

1998

2000

2003

2005

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

January 14 - Michael Steele, the first African-American Chairman of the RNC

lost his bid for re-election; Reince Priebus

was the winner of the election.

African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)

The African-American Civil Rights Movement refers to the movements in the United States aimed at outlawing racial discrimination against African Americans and restoring voting rights to them. This article covers the phase of the movement between 1955 and 1968, particularly in the South...

.

Pre-17th century

(Information in this section primarily taken from Slavery in Colonial United States.)1565

- unknown – The colony of St. AugustineSt. Augustine, FloridaSt. Augustine is a city in the northeast section of Florida and the county seat of St. Johns County, Florida, United States. Founded in 1565 by Spanish explorer and admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, it is the oldest continuously occupied European-established city and port in the continental United...

in FloridaFloridaFlorida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

became the first permanent European settlement in what would become the US, and included an unknown number of African slaves.

17th century

1619- unknown – The first record of African slavery in English Colonial America.

1640

- unknown – John Punch, a black indentured servant, ran away with two white indentured servants, James Gregory and Victor. After the three were captured, the white men were sentenced to four more years of servitude but Punch was required to serve Virginia planter Hugh Gym for life. It is one of the first cases in which lifetime indentured servitude was based on race.

1654

- unknown – John CasorJohn CasorJohn Casor , a servant in Northampton County in the Virginia Colony, in 1654 became the first person of African descent in the Thirteen Colonies to be declared by the county court a slave for life. In one of the earliest freedom suits, Casor argued that he was an indentured servant who had been...

, a black man, became the first legally-recognized slave-for-life in the Virginia colony.

1662

- unknown – Virginia law defined that children of enslaved mothers followed the status of their mothers and were considered slaves, regardless of their father's status.

1676

- unknown – Both free and enslaved African Americans fought in Bacon's RebellionBacon's RebellionBacon's Rebellion was an uprising in 1676 in the Virginia Colony in North America, led by a 29-year-old planter, Nathaniel Bacon.About a thousand Virginians rose because they resented Virginia Governor William Berkeley's friendly policies towards the Native Americans...

along with English colonists.

18th century

1705- unknown – The Virginia Slave codesSlave codesSlave codes were laws each US state, which defined the status of slaves and the rights of masters. These codes gave slave-owners absolute power over the African slaves.-Definition of "slaves":Virginia, 1650:“Act XI...

defines as slaves all those servants brought into the colony who were not Christian in their original countries, as well as those Indians sold to colonists by other Indians.

1712

- April 6 – The New York Slave Revolt of 1712, one of the first of many such rebellions (see the article).

1739

- September 9 – In the Stono RebellionStono RebellionThe Stono Rebellion was a slave rebellion that commenced on 9 September 1739, in the colony of South Carolina...

, South Carolina slaves gather at the Stono RiverStono RiverThe Stono River is a tidal channel in southeast South Carolina, located southwest of Charleston. The channel runs southwest to northeast between the mainland and Wadmalaw Island and Johns Island, from north Edisto River between Johns and James Island. The Intracoastal Waterway runs through...

to plan an armed march for freedom.

1760

- unknown – Jupiter HammonJupiter HammonJupiter Hammon was a Black poet who became the first African-American published writer in America when a poem appeared in print in 1760. He was a slave his entire life, and the date of his death is unknown. He was living in 1790 at the age of 79, and died by 1806...

has a poem printed, becoming the first published African-American poet.

1770

- March 5 – Crispus AttucksCrispus AttucksCrispus Attucks was a dockworker of Wampanoag and African descent. He was the first person shot to death by British redcoats during the Boston Massacre, in Boston, Massachusetts...

is killed by British soldiers in the Boston MassacreBoston MassacreThe Boston Massacre, called the Boston Riot by the British, was an incident on March 5, 1770, in which British Army soldiers killed five civilian men. British troops had been stationed in Boston, capital of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, since 1768 in order to protect and support...

, a precursor to the American RevolutionAmerican RevolutionThe American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

.

1773

- unknown – Phillis WheatleyPhillis WheatleyPhillis Wheatley was the first African American poet and first African-American woman whose writings were published. Born in Gambia, Senegal, she was sold into slavery at age seven...

has her book Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral published.

1774

- – The first black Baptist congregations are organized in the SouthSouthern United StatesThe Southern United States—commonly referred to as the American South, Dixie, or simply the South—constitutes a large distinctive area in the southeastern and south-central United States...

: Silver Bluff Baptist ChurchSilver Bluff Baptist ChurchThe Silver Bluff Baptist Church in Aiken County, South Carolina, was founded by several enslaved African Americans who organized under elder David George in 1773-1775....

in South Carolina, and First African Baptist Church near Petersburg, VirginiaPetersburg, VirginiaPetersburg is an independent city in Virginia, United States located on the Appomattox River and south of the state capital city of Richmond. The city's population was 32,420 as of 2010, predominantly of African-American ethnicity...

.

1775

- April 14 – The Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully held in Bondage holds four meetings. Re-formed in 1784 as the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, Benjamin FranklinBenjamin FranklinDr. Benjamin Franklin was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. A noted polymath, Franklin was a leading author, printer, political theorist, politician, postmaster, scientist, musician, inventor, satirist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat...

would later be its president.

1776–1783 American Revolution

- Thousands of enslaved African Americans in the South escape to BritishGreat BritainGreat Britain or Britain is an island situated to the northwest of Continental Europe. It is the ninth largest island in the world, and the largest European island, as well as the largest of the British Isles...

or LoyalistLoyalist (American Revolution)Loyalists were American colonists who remained loyal to the Kingdom of Great Britain during the American Revolutionary War. At the time they were often called Tories, Royalists, or King's Men. They were opposed by the Patriots, those who supported the revolution...

lines, as they were promised freedom if they fought with the British. In South CarolinaSouth CarolinaSouth Carolina is a state in the Deep South of the United States that borders Georgia to the south, North Carolina to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Originally part of the Province of Carolina, the Province of South Carolina was one of the 13 colonies that declared independence...

, 25,000 enslaved African Americans, one-quarter of those held, escape to the British. After the war, many African Americans leave with the British for EnglandEnglandEngland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

; others go with other Loyalists to CanadaCanadaCanada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

and settle in Nova ScotiaNova ScotiaNova Scotia is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the most populous province in Atlantic Canada. The name of the province is Latin for "New Scotland," but "Nova Scotia" is the recognized, English-language name of the province. The provincial capital is Halifax. Nova Scotia is the...

and New BrunswickNew BrunswickNew Brunswick is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the only province in the federation that is constitutionally bilingual . The provincial capital is Fredericton and Saint John is the most populous city. Greater Moncton is the largest Census Metropolitan Area...

. Still others go to JamaicaJamaicaJamaica is an island nation of the Greater Antilles, in length, up to in width and 10,990 square kilometres in area. It is situated in the Caribbean Sea, about south of Cuba, and west of Hispaniola, the island harbouring the nation-states Haiti and the Dominican Republic...

and the West Indies. - Many free blacks in the North fight with the colonists for the rebellion.

1777

- July 8 – The Vermont RepublicVermont RepublicThe term Vermont Republic has been used by later historians for the government of what became modern Vermont from 1777 to 1791. In July 1777 delegates from 28 towns met and declared independence from jurisdictions and land claims of British colonies in New Hampshire and New York. They also...

(a sovereign nation at the time) abolishes slavery, the first future state to do so.

1780

- PennsylvaniaPennsylvaniaThe Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is a U.S. state that is located in the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The state borders Delaware and Maryland to the south, West Virginia to the southwest, Ohio to the west, New York and Ontario, Canada, to the north, and New Jersey to...

becomes the first then-U.S.-state to abolish slavery.

1787

- July 13 – The Northwest OrdinanceNorthwest OrdinanceThe Northwest Ordinance was an act of the Congress of the Confederation of the United States, passed July 13, 1787...

bans the expansion of slavery into U.S. territories north of the Ohio RiverOhio RiverThe Ohio River is the largest tributary, by volume, of the Mississippi River. At the confluence, the Ohio is even bigger than the Mississippi and, thus, is hydrologically the main stream of the whole river system, including the Allegheny River further upstream...

and east of the Mississippi RiverMississippi RiverThe Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

.

1788

- – The First African Baptist Church of Savannah, GeorgiaSavannah, GeorgiaSavannah is the largest city and the county seat of Chatham County, in the U.S. state of Georgia. Established in 1733, the city of Savannah was the colonial capital of the Province of Georgia and later the first state capital of Georgia. Today Savannah is an industrial center and an important...

is organized under Andrew Bryan.

1790–1810 Manumission of slaves

- – Following the Revolution, numerous slaveholders in the Upper South freeManumissionManumission is the act of a slave owner freeing his or her slaves. In the United States before the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which abolished most slavery, this often happened upon the death of the owner, under conditions in his will.-Motivations:The...

their slaves; the percentage of free blacks rises from less than one to 10 percent. By 1810, 75 percent of all blacks in DelawareDelawareDelaware is a U.S. state located on the Atlantic Coast in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It is bordered to the south and west by Maryland, and to the north by Pennsylvania...

are free, and 7.2 percent of blacks in VirginiaVirginiaThe Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

are free.

1791

- February – Major Andrew EllicottAndrew EllicottAndrew Ellicott was a U.S. surveyor who helped map many of the territories west of the Appalachians, surveyed the boundaries of the District of Columbia, continued and completed Pierre Charles L'Enfant's work on the plan for Washington, D.C., and served as a teacher in survey methods for...

hires Benjamin BannekerBenjamin BannekerBenjamin Banneker was a free African American astronomer, mathematician, surveyor, almanac author and farmer.-Family history and early life:It is difficult to verify much of Benjamin Banneker's family history...

to assist in a survey of the boundaries of the 100 square miles (259 km²) federal district that would later become the District of Columbia.

1793

- February 12 – The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793Fugitive Slave Act of 1793The Fugitive Slave Clause of the U.S. Constitution guaranteed the right of a slaveholder to recover an escaped slave...

is passed. (See also Fugitive slave lawsFugitive slave lawsThe fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of slaves who escaped from one state into another state or territory.-Pre-colonial and Colonial eras:...

.)

1794

- March 14 – Eli WhitneyEli WhitneyEli Whitney was an American inventor best known for inventing the cotton gin. This was one of the key inventions of the Industrial Revolution and shaped the economy of the Antebellum South...

is granted a patent on the cotton ginCotton ginA cotton gin is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, a job formerly performed painstakingly by hand...

. This enables the widespread cultivation and processing of short-staple cotton, dramatically increasing the need for enslaved labor, and leading to the development of King CottonKing CottonKing Cotton was a slogan used by southerners to support secession from the United States by arguing cotton exports would make an independent Confederacy economically prosperous, and—more important—would force Great Britain and France to support the Confederacy because their industrial economy...

in the Deep SouthDeep SouthThe Deep South is a descriptive category of the cultural and geographic subregions in the American South. Historically, it is differentiated from the "Upper South" as being the states which were most dependent on plantation type agriculture during the pre-Civil War period...

. It leads to the forced migrationForced migrationForced migration refers to the coerced movement of a person or persons away from their home or home region...

of one million slaves to the area in the antebellum period, mostly by internal slave trade. - July – Two independent black churches open in Philadelphia: the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, with Absalom JonesAbsalom JonesAbsalom Jones was an African-American abolitionist and clergyman. After founding a black congregation in 1794, in 1804 he was the first African-American ordained as a priest in the Episcopal Church of the United States...

, and the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal ChurchMother Bethel A.M.E. ChurchThe Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church was founded in 1794 by Richard Allen, an African-American Methodist minister. The church has been located at the corner of Sixth and Lombard Streets in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, since that time, making it the oldest church property continuously...

, with Richard Allen, the first church of what would become a new black denomination in 1816.

1800–1859

Early 19th century- unknown – first Black Codes enacted.

1800

- August 30 – Gabriel ProsserGabriel ProsserGabriel , today commonly – if incorrectly – known as Gabriel Prosser, was a literate enslaved blacksmith who planned to lead a large slave rebellion in the Richmond area in the summer of 1800. However, information regarding the revolt was leaked prior to its execution, thus Gabriel's plans were...

's attempt to lead a slave rebellionSlave rebellionA slave rebellion is an armed uprising by slaves. Slave rebellions have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery, and are amongst the most feared events for slaveholders...

in Richmond, VirginiaRichmond, VirginiaRichmond is the capital of the Commonwealth of Virginia, in the United States. It is an independent city and not part of any county. Richmond is the center of the Richmond Metropolitan Statistical Area and the Greater Richmond area...

is suppressed.

1807

- unknown – Act Prohibiting Importation of SlavesAct Prohibiting Importation of SlavesThe Act Prohibiting Importation of Slaves of 1807 is a United States federal law that stated, in accordance with the Constitution of the United States, that no new slaves were permitted to be imported into the United States. This act ended the legality of the U.S.-based transatlantic slave trade...

1808

- January 1 – The importation of slaves into the United StatesUnited StatesThe United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

is banned; this is also the earliest day under the United States ConstitutionUnited States ConstitutionThe Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It is the framework for the organization of the United States government and for the relationship of the federal government with the states, citizens, and all people within the United States.The first three...

that an amendment could be made restricting slavery.

1816

- unknown – The first separate black denomination of the African Methodist Episcopal ChurchAfrican Methodist Episcopal ChurchThe African Methodist Episcopal Church, usually called the A.M.E. Church, is a predominantly African American Methodist denomination based in the United States. It was founded by the Rev. Richard Allen in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1816 from several black Methodist congregations in the...

(AME) is founded by Richard Allen, who is elected its first bishop. - unknown – The American Colonization SocietyAmerican Colonization SocietyThe American Colonization Society , founded in 1816, was the primary vehicle to support the "return" of free African Americans to what was considered greater freedom in Africa. It helped to found the colony of Liberia in 1821–22 as a place for freedmen...

is begun by Robert FinleyRobert FinleyRobert Finley was briefly the president of the University of Georgia. Finley was born in Princeton, New Jersey, and graduated from College of New Jersey at the age of 15.-Early life:Finley was born to James Finley and Ann Angrest, James was born 1737 in Glasgow, Scotland where he...

, to send free African Americans to what is to become LiberiaLiberiaLiberia , officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Sierra Leone on the west, Guinea on the north and Côte d'Ivoire on the east. Liberia's coastline is composed of mostly mangrove forests while the more sparsely populated inland consists of forests that open...

in Africa.

1820

- March 6 – The Missouri CompromiseMissouri CompromiseThe Missouri Compromise was an agreement passed in 1820 between the pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions in the United States Congress, involving primarily the regulation of slavery in the western territories. It prohibited slavery in the former Louisiana Territory north of the parallel 36°30'...

allows for the entry as states of MaineMaineMaine is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the east and south, New Hampshire to the west, and the Canadian provinces of Quebec to the northwest and New Brunswick to the northeast. Maine is both the northernmost and easternmost...

and MissouriMissouriMissouri is a US state located in the Midwestern United States, bordered by Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With a 2010 population of 5,988,927, Missouri is the 18th most populous state in the nation and the fifth most populous in the Midwest. It...

, and decides which future states slavery would be allowed in. - unknown – The British West Africa SquadronWest Africa SquadronThe Royal Navy established the West Africa Squadron at substantial expense in 1808 after Parliament passed the Slave Trade Act of 1807. The squadron's task was to suppress the Atlantic slave trade by patrolling the coast of West Africa...

's slave trade suppression activities are assisted by forces from the United States NavyUnited States NavyThe United States Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the seven uniformed services of the United States. The U.S. Navy is the largest in the world; its battle fleet tonnage is greater than that of the next 13 largest navies combined. The U.S...

, starting in 1820 with the USS Cyane. With the Webster–Ashburton Treaty of 1842, the relationship is formalised and they jointly run the Africa SquadronAfrica SquadronThe Africa Squadron was a unit of the United States Navy that operated from 1819 to 1861 to suppress the slave trade along the coast of West Africa...

.

1821

- unknown – The African Methodist Episcopal Zion ChurchAfrican Methodist Episcopal Zion ChurchThe African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, or AME Zion Church, is a historically African-American Christian denomination. It was officially formed in 1821, but operated for a number of years before then....

is officially formed.

1822

- July 14 – Denmark VeseyDenmark VeseyDenmark Vesey originally Telemaque, was an African American slave brought to the United States from the Caribbean of Coromantee background. After purchasing his freedom, he planned what would have been one of the largest slave rebellions in the United States...

's slave rebellion in Charleston, South CarolinaCharleston, South CarolinaCharleston is the second largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. It was made the county seat of Charleston County in 1901 when Charleston County was founded. The city's original name was Charles Towne in 1670, and it moved to its present location from a location on the west bank of the...

is suppressed.

1829

- September – David WalkerDavid Walker (abolitionist)David Walker was an outspoken African American activist who demanded the immediate end of slavery in the new nation...

begins publication of the abolitionist pamphlet Walker's Appeal.

1830

- October 28 - Josiah HensonJosiah HensonJosiah Henson was an author, abolitionist, and minister. Born into slavery in Charles County, Maryland, he escaped to Ontario, Canada in 1830, and founded a settlement and laborer's school for other fugitive slaves at Dawn, near Dresden in Kent County...

, a slave who fled and arrived in Canada, is an author, abolitionist, minister and the inspiration behind the book Uncle Tom's CabinUncle Tom's CabinUncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in 1852, the novel "helped lay the groundwork for the Civil War", according to Will Kaufman....

.

1831

- unknown – William Lloyd GarrisonWilliam Lloyd GarrisonWilliam Lloyd Garrison was a prominent American abolitionist, journalist, and social reformer. He is best known as the editor of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator, and as one of the founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society, he promoted "immediate emancipation" of slaves in the United...

begins publication of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator. - August – Nat TurnerNat TurnerNathaniel "Nat" Turner was an American slave who led a slave rebellion in Virginia on August 21, 1831 that resulted in 60 white deaths and at least 100 black deaths, the largest number of fatalities to occur in one uprising prior to the American Civil War in the southern United States. He gathered...

leads the most successful slave rebellion in U.S. history. The rebellion is suppressed, but only after many deaths.

1833

- unknown – The American Anti-Slavery SocietyAmerican Anti-Slavery SocietyThe American Anti-Slavery Society was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass was a key leader of this society and often spoke at its meetings. William Wells Brown was another freed slave who often spoke at meetings. By 1838, the society had...

, an abolitionistAbolitionismAbolitionism is a movement to end slavery.In western Europe and the Americas abolitionism was a movement to end the slave trade and set slaves free. At the behest of Dominican priest Bartolomé de las Casas who was shocked at the treatment of natives in the New World, Spain enacted the first...

society, is founded by William Lloyd GarrisonWilliam Lloyd GarrisonWilliam Lloyd Garrison was a prominent American abolitionist, journalist, and social reformer. He is best known as the editor of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator, and as one of the founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society, he promoted "immediate emancipation" of slaves in the United...

and Arthur TappanArthur TappanArthur Tappan was an American abolitionist. He was the brother of Senator Benjamin Tappan, and abolitionist Lewis Tappan.-Biography:...

. Frederick DouglassFrederick DouglassFrederick Douglass was an American social reformer, orator, writer and statesman. After escaping from slavery, he became a leader of the abolitionist movement, gaining note for his dazzling oratory and incisive antislavery writing...

becomes a key leader of the society.

1837

- February - The first Institute of Higher Education for Afican-Americans is founded. Founded as the African Institute in February 1837 and renamed the Institute of Coloured Youth (ICY) in April 1837 and now known as Cheyney University of PennsylvaniaCheyney University of PennsylvaniaCheyney University of Pennsylvania is a public, co-educational historically black university that is a part of the Pennsylvania State System of Higher Education. Cheyney University has a campus that is located in the Cheyney community within Thornbury Township, Chester County and Thornbury...

.

1839

- July 2 – Slaves revolt on the La AmistadLa AmistadLa Amistad was a ship notable as the scene of a revolt by African captives being transported from Havana to Puerto Principe, Cuba. It was a 19th-century two-masted schooner built in Spain and owned by a Spaniard living in Cuba...

, resulting in a Supreme Court case (see Amistad (1841)Amistad (1841)The Amistad, also known as United States v. Libellants and Claimants of the Schooner Amistad, 40 U.S. 518 , was a United States Supreme Court case resulting from the rebellion of slaves on board the Spanish schooner Amistad in 1839...

).

1840

- unknown – The Liberty Party breaks away from the American Anti-Slavery SocietyAmerican Anti-Slavery SocietyThe American Anti-Slavery Society was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass was a key leader of this society and often spoke at its meetings. William Wells Brown was another freed slave who often spoke at meetings. By 1838, the society had...

due to grievances with William Lloyd GarrisonWilliam Lloyd GarrisonWilliam Lloyd Garrison was a prominent American abolitionist, journalist, and social reformer. He is best known as the editor of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator, and as one of the founders of the American Anti-Slavery Society, he promoted "immediate emancipation" of slaves in the United...

's leadership.

1842

- unknown – The U.S. Supreme CourtSupreme Court of the United StatesThe Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

rules, in Prigg v. PennsylvaniaPrigg v. PennsylvaniaPrigg v. Pennsylvania, , was a United States Supreme Court case in which the court held that the Federal Fugitive Slave Act precluded a Pennsylvania state law that gave procedural protections to suspected escaped slaves, and overturned the conviction of Edward Prigg as a result.-Federal Law:In June...

(1842), that states do not have to offer aid in the hunting or recapture of slaves, greatly weakening the fugitive slave law of 1793.

1843

- June 1 – Isabella Baumfree, a former slave, changes her name to Sojourner TruthSojourner TruthSojourner Truth was the self-given name, from 1843 onward, of Isabella Baumfree, an African-American abolitionist and women's rights activist. Truth was born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, but escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826. After going to court to recover her son, she...

and begins to preach for the abolition of slavery. - August – Henry Highland GarnetHenry Highland GarnetHenry Highland Garnet was an African American abolitionist and orator. An advocate of militant abolitionism, Garnet was a prominent member of the abolition movement that led against moral suasion toward more political action. Renowned for his skills as a public speaker, he urged blacks to take...

delivers his famous speech Call to Rebellion.

1847

- unknown – Frederick DouglassFrederick DouglassFrederick Douglass was an American social reformer, orator, writer and statesman. After escaping from slavery, he became a leader of the abolitionist movement, gaining note for his dazzling oratory and incisive antislavery writing...

begins publication of the abolitionist newspaper the North Star. - unknown – Joseph Jenkins RobertsJoseph Jenkins RobertsJoseph Jenkins Roberts was the first and seventh President of Liberia. Born free in Norfolk, Virginia, USA, Roberts emigrated to Liberia in 1829 as a young man. He opened a trading store in Monrovia, and later engaged in politics...

of Virginia becomes the first president of LiberiaLiberiaLiberia , officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Sierra Leone on the west, Guinea on the north and Côte d'Ivoire on the east. Liberia's coastline is composed of mostly mangrove forests while the more sparsely populated inland consists of forests that open...

.

1849

- unknown – Roberts v. BostonRoberts v. BostonRoberts v. Boston, 59 Mass. 198 , was a lawsuit seeking to end racial discrimination in Boston public schools. The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in favor of Boston, finding no constitutional basis for the suit. The case was later cited by the US Supreme Court in Plessy v...

seeks to end racial discrimination in BostonBostonBoston is the capital of and largest city in Massachusetts, and is one of the oldest cities in the United States. The largest city in New England, Boston is regarded as the unofficial "Capital of New England" for its economic and cultural impact on the entire New England region. The city proper had...

public schools. - unknown – Harriet TubmanHarriet TubmanHarriet Tubman Harriet Tubman Harriet Tubman (born Araminta Harriet Ross; (1820 – 1913) was an African-American abolitionist, humanitarian, and Union spy during the American Civil War. After escaping from slavery, into which she was born, she made thirteen missions to rescue more than 70 slaves...

escapes from slavery to Philadelphia, and begins helping other slaves to escape via the Underground RailroadUnderground RailroadThe Underground Railroad was an informal network of secret routes and safe houses used by 19th-century black slaves in the United States to escape to free states and Canada with the aid of abolitionists and allies who were sympathetic to their cause. The term is also applied to the abolitionists,...

.

1850

- September 18 – As part of the Compromise of 1850Compromise of 1850The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five bills, passed in September 1850, which defused a four-year confrontation between the slave states of the South and the free states of the North regarding the status of territories acquired during the Mexican-American War...

, Congress passes the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 which requires any federal official to arrest anyone suspected of being a runaway slave.

1852

- March 20 – Uncle Tom's CabinUncle Tom's CabinUncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in 1852, the novel "helped lay the groundwork for the Civil War", according to Will Kaufman....

by Harriet Beecher StoweHarriet Beecher StoweHarriet Beecher Stowe was an American abolitionist and author. Her novel Uncle Tom's Cabin was a depiction of life for African-Americans under slavery; it reached millions as a novel and play, and became influential in the United States and United Kingdom...

is published.

1853

- December – Clotel; or, The President's DaughterClotelClotel; or, The President's Daughter is an 1853 novel by U.S. author and playwright William Wells Brown, an escaped slave from Kentucky who was active on the anti-slavery circuit...

is the first novel published by an African-American.

1855

- unknown – John Mercer LangstonJohn Mercer LangstonJohn Mercer Langston was an American abolitionist, attorney, educator, and political activist. He was the first dean of the law school at Howard University and helped create the department. He was the first president of what is now Virginia State University. In 1888 he was the first African...

is one of the first African Americans elected to public office when elected as a town clerk in OhioOhioOhio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus...

.

1856

- May 21 – The Sacking of LawrenceSacking of LawrenceIn the northern spring of 1856, the Sacking of Lawrence helped ratchet up the guerrilla war in Kansas Territory that became known as Bleeding Kansas.-Background:...

in Bleeding KansasBleeding KansasBleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas or the Border War, was a series of violent events, involving anti-slavery Free-Staters and pro-slavery "Border Ruffian" elements, that took place in the Kansas Territory and the western frontier towns of the U.S. state of Missouri roughly between 1854 and 1858...

. - May 25 – John BrownJohn Brown (abolitionist)John Brown was an American revolutionary abolitionist, who in the 1850s advocated and practiced armed insurrection as a means to abolish slavery in the United States. He led the Pottawatomie Massacre during which five men were killed, in 1856 in Bleeding Kansas, and made his name in the...

, whom Abraham Lincoln called a "misguided fanatic", retaliates for Lawrence's sacking in the Pottawatomie MassacrePottawatomie MassacreThe Pottawatomie Massacre occurred during the night of May 24 and the morning of May 25, 1856. In reaction to the sacking of Lawrence by pro-slavery forces, John Brown and a band of abolitionist settlers killed five settlers north of Pottawatomie Creek in Franklin County, Kansas...

. - unknown – Wilberforce UniversityWilberforce UniversityWilberforce University is a private, coed, liberal arts historically black university located in Wilberforce, Ohio. Affiliated with the African Methodist Episcopal Church, it was the first college to be owned and operated by African Americans...

is founded by collaboration between Methodist Episcopal and African Methodist Episcopal representatives.

1857

- March 6 – In Dred Scott v. SandfordDred Scott v. SandfordDred Scott v. Sandford, , also known as the Dred Scott Decision, was a ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court that people of African descent brought into the United States and held as slaves were not protected by the Constitution and could never be U.S...

, the Supreme CourtSupreme Court of the United StatesThe Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

upholds slaverySlaverySlavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

. This decision is regarded as a key cause of the American Civil WarAmerican Civil WarThe American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

.

1859

- unknown – Harriet E. WilsonHarriet E. WilsonHarriet E. Wilson is traditionally considered the first female African-American novelist as well as the first African American of any gender to publish a novel on the North American continent...

writes the autobiographical novel Our NigOur NigOur Nig: Sketches from the Life of a Free Black is an autobiographical slave narrative by Harriet E. Wilson. It was published in 1859 and rediscovered in 1982 by professor Henry Louis Gates, Jr.. It is considered the first novel published by an African-American on the North American...

. - unknown – In Ableman v. BoothAbleman v. BoothAbleman v. Booth, , is a case in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that state courts cannot issue rulings that contradict the decisions of federal courts, overturning a decision by the Supreme Court of Wisconsin....

the Supreme Court of the United States holds that state courts cannot issue rulings that contradict the decisions of federal courts, thus upholding the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

1860–1874

1861- April 12 – The American Civil WarAmerican Civil WarThe American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

begins (secessions began in December, 1860), and lasts until April 9, 1865. Tens of thousands of enslaved African Americans of all ages escaped to UnionUnion (American Civil War)During the American Civil War, the Union was a name used to refer to the federal government of the United States, which was supported by the twenty free states and five border slave states. It was opposed by 11 southern slave states that had declared a secession to join together to form the...

lines for freedom. Contraband camps were set up in some areas, where blacks started learning to read and write. Others traveled with the Union ArmyUnion ArmyThe Union Army was the land force that fought for the Union during the American Civil War. It was also known as the Federal Army, the U.S. Army, the Northern Army and the National Army...

. By the end of the war, more than 180,000 African Americans, mostly from the South, fought with the Union Army and Navy as members of the US Colored TroopsUnited States Colored TroopsThe United States Colored Troops were regiments of the United States Army during the American Civil War that were composed of African American soldiers. First recruited in 1863, by the end of the Civil War, the men of the 175 regiments of the USCT constituted approximately one-tenth of the Union...

and sailors. - May 2 – The first North American military unit with African-American officers is the 1st Louisiana Native Guard1st Louisiana Native Guard (CSA)The 1st Louisiana Native Guard was a Confederate Louisiana militia of "free persons of color" formed in 1861 in New Orleans, Louisiana. It was disbanded in February 1862; some of the members joined the Union Army's 1st Louisiana Native Guard regiment The 1st Louisiana Native Guard (CSA) was a...

of the Confederate Army (disbanded in February 1862). - August 6 – The first of the Confiscation ActsConfiscation ActsThe Confiscation Acts were laws passed by the United States Congress during the Civil War with the intention of freeing the slaves still held by the Confederate forces in the South....

authorizes the confiscation of any Confederate property, including all slaves who fought or worked for the Confederate military. The second act in mid-1862 extends this.

1862

- March 13 – Act Prohibiting the Return of SlavesAct Prohibiting the Return of SlavesThe Act Prohibiting the Return of Slaves was a law passed by the United States Congress during the American Civil War forbidding the military to return escaped slaves to their owners. As Union armies entered Southern territory during the early years of the War, emboldened slaves began fleeing...

- September 22 – Announcement of the Emancipation ProclamationEmancipation ProclamationThe Emancipation Proclamation is an executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War using his war powers. It proclaimed the freedom of 3.1 million of the nation's 4 million slaves, and immediately freed 50,000 of them, with nearly...

, after the Battle of AntietamBattle of AntietamThe Battle of Antietam , fought on September 17, 1862, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, and Antietam Creek, as part of the Maryland Campaign, was the first major battle in the American Civil War to take place on Northern soil. It was the bloodiest single-day battle in American history, with about 23,000...

, to go into effect January 1, 1863.

1863–1877 Reconstruction

1863

- January 1 – The Emancipation ProclamationEmancipation ProclamationThe Emancipation Proclamation is an executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War using his war powers. It proclaimed the freedom of 3.1 million of the nation's 4 million slaves, and immediately freed 50,000 of them, with nearly...

goes into effect. - January 31 – U.S. Army commissions the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, a combat unit made up of escaped slaves.

- May 22 – U.S. Army recruits United States Colored TroopsUnited States Colored TroopsThe United States Colored Troops were regiments of the United States Army during the American Civil War that were composed of African American soldiers. First recruited in 1863, by the end of the Civil War, the men of the 175 regiments of the USCT constituted approximately one-tenth of the Union...

. (The 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment54th Massachusetts Volunteer RegimentThe 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment is a regiment of the Massachusetts Army National Guard. It is a descendent of the famous 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry.-History:...

would be featured in the 1989 film Glory.) - July – Irish ethnic protests against the draft in New York CityNew York CityNew York is the most populous city in the United States and the center of the New York Metropolitan Area, one of the most populous metropolitan areas in the world. New York exerts a significant impact upon global commerce, finance, media, art, fashion, research, technology, education, and...

turn into riots against blacks – the so-called New York Draft RiotsNew York Draft RiotsThe New York City draft riots were violent disturbances in New York City that were the culmination of discontent with new laws passed by Congress to draft men to fight in the ongoing American Civil War. The riots were the largest civil insurrection in American history apart from the Civil War itself...

.

1864

- April 12 – The Battle of Fort PillowBattle of Fort PillowThe Battle of Fort Pillow, also known as the Fort Pillow Massacre, was fought on April 12, 1864, at Fort Pillow on the Mississippi River in Henning, Tennessee, during the American Civil War. The battle ended with a massacre of surrendered Federal black troops by soldiers under the command of...

, which results in controversy about whether a massacre of surrendered African-American troops was conducted or condoned.

1865

- March 3 – Congress passes the bill that forms the Freedman's BureauBureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned LandsThe Freedmen's Bureau, was a U.S. federal government agency that aided distressed freedmen in 1865–1869, during the Reconstruction era of the United States....

. - December 18 – The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States ConstitutionThirteenth Amendment to the United States ConstitutionThe Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution officially abolished and continues to prohibit slavery and involuntary servitude, except as punishment for a crime. It was passed by the Senate on April 8, 1864, passed by the House on January 31, 1865, and adopted on December 6, 1865. On...

abolishes slaverySlaverySlavery is a system under which people are treated as property to be bought and sold, and are forced to work. Slaves can be held against their will from the time of their capture, purchase or birth, and deprived of the right to leave, to refuse to work, or to demand compensation...

in the U.S. - unknown – Shaw InstituteShaw UniversityShaw University, founded as Raleigh Institute, is a private liberal arts institution and historically black university in Raleigh, North Carolina, United States. Founded in 1865, it is the oldest HBCU in the Southern United States....

is founded in Raleigh, North CarolinaRaleigh, North CarolinaRaleigh is the capital and the second largest city in the state of North Carolina as well as the seat of Wake County. Raleigh is known as the "City of Oaks" for its many oak trees. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city's 2010 population was 403,892, over an area of , making Raleigh...

, as the first black collegeHistorically Black Colleges and UniversitiesHistorically black colleges and universities are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before 1964 with the intention of serving the black community....

in the South. - unknown – Atlanta CollegeClark Atlanta UniversityClark Atlanta University is a private, historically black university in Atlanta, Georgia. It was formed in 1988 with the consolidation of Clark College and Atlanta University...

is founded. - unknown – Every southern state passes Black Codes that restrict the freedmen, who were emancipated but not yet full citizens.

1866

- April 9 – The Civil Rights Act of 1866Civil Rights Act of 1866The Civil Rights Act of 1866, , enacted April 9, 1866, is a federal law in the United States that was mainly intended to protect the civil rights of African-Americans, in the wake of the American Civil War...

is passed by Congress over Johnson's presidential vetoVetoA veto, Latin for "I forbid", is the power of an officer of the state to unilaterally stop an official action, especially enactment of a piece of legislation...

. All persons born in the United StatesUnited StatesThe United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

are now citizens. - unknown – The Ku Klux KlanKu Klux KlanKu Klux Klan, often abbreviated KKK and informally known as the Klan, is the name of three distinct past and present far-right organizations in the United States, which have advocated extremist reactionary currents such as white supremacy, white nationalism, and anti-immigration, historically...

is formed in Pulaski, TennesseePulaski, TennesseePulaski is a city in Giles County, Tennessee, United States. The population was 7,870 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Giles County. It was named to honor the Polish-born American Revolutionary War hero Kazimierz Pułaski...

, made up of white Confederate veterans; it becomes a paramilitaryParamilitaryA paramilitary is a force whose function and organization are similar to those of a professional military, but which is not considered part of a state's formal armed forces....

insurgent group to enforce white supremacy. - July – New Orleans white citizens riot against blacks.

- September 21 – The U.S. Army regiment of Buffalo SoldierBuffalo SoldierBuffalo Soldiers originally were members of the U.S. 10th Cavalry Regiment of the United States Army, formed on September 21, 1866 at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas....

s (African Americans) is formed. - unknown – The Second Freedmen's Bureau Act would have provided longer enforcement of rights for freedmen, but it is vetoed by President Andrew JohnsonAndrew JohnsonAndrew Johnson was the 17th President of the United States . As Vice-President of the United States in 1865, he succeeded Abraham Lincoln following the latter's assassination. Johnson then presided over the initial and contentious Reconstruction era of the United States following the American...

.

1867

- March 2 – Howard UniversityHoward UniversityHoward University is a federally chartered, non-profit, private, coeducational, nonsectarian, historically black university located in Washington, D.C., United States...

is founded in Washington, D.C.

1868

- April 1 – Hampton InstituteHampton UniversityHampton University is a historically black university located in Hampton, Virginia, United States. It was founded by black and white leaders of the American Missionary Association after the American Civil War to provide education to freedmen.-History:...

is founded in Hampton, VirginiaHampton, VirginiaHampton is an independent city that is not part of any county in Southeast Virginia. Its population is 137,436. As one of the seven major cities that compose the Hampton Roads metropolitan area, it is on the southeastern end of the Virginia Peninsula. Located on the Hampton Roads Beltway, it hosts...

. - July 9 – The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States ConstitutionFourteenth Amendment to the United States ConstitutionThe Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments.Its Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship that overruled the Dred Scott v...

's Section 1 requires due processDue processDue process is the legal code that the state must venerate all of the legal rights that are owed to a person under the principle. Due process balances the power of the state law of the land and thus protects individual persons from it...

and equal protection. - unknown – Through 1877, whites attack black and white Republicans to suppress voting. Every election cycle is accompanied by violence, increasing in the 1870s.

- unknown – Elizabeth KecklyElizabeth KecklyElizabeth Hobbs Keckley was a former slave turned successful seamstress who is most notably known as being Mary Todd Lincoln's personal modiste and confidante, and the author of her autobiography, Behind the Scenes Or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House. Mrs...

publishes Behind the Scenes (or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House).

1870

- February 3 – The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States ConstitutionFifteenth Amendment to the United States ConstitutionThe Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits each government in the United States from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude"...

guarantees the right of male citizens of the United States to vote regardless of race, color or previous condition of servitude. - February 25 – Hiram Rhodes RevelsHiram Rhodes RevelsHiram Rhodes Revels was the first African American to serve in the United States Senate. Because he preceded any African American in the House, he was the first African American in the U.S. Congress as well. He represented Mississippi in 1870 and 1871 during Reconstruction...

becomes the first black member of the SenateUnited States SenateThe United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

(see African Americans in the United States CongressAfrican Americans in the United States CongressAfrican Americans began serving in greater numbers in the United States Congress during the Reconstruction Era following the American Civil War after slaves were emancipated and granted citizenship rights. Freedmen gained political representation in the Southern United States for the first time...

). - unknown – Christian Methodist Episcopal ChurchChristian Methodist Episcopal ChurchThe Christian Methodist Episcopal Church is a historically black denomination within the broader context of Methodism. The group was organized in 1870 when several black ministers, with the full support of their white counterparts in the former Methodist Episcopal Church, South, met to form an...

founded.

1871

- October 10 – Octavius CattoOctavius CattoOctavius Valentine Catto was a black educator, intellectual, and civil rights activist. He was also known for being a cricket and baseball player in 19th-century Philadelphia, Pennsylvania...

, a civil rights activist, is murdered during harassment of blacks on Election Day in Philadelphia. - unknown – US Civil Rights Act of 1871Civil Rights Act of 1871The Civil Rights Act of 1871, , enacted April 20, 1871, is a federal law in force in the United States. The Act was originally enacted a few years after the American Civil War, along with the 1870 Force Act. One of the chief reasons for its passage was to protect southern blacks from the Ku Klux...

passed, also known as the Klan Act.

1872

- December 11 – P. B. S. PinchbackP. B. S. PinchbackPinckney Benton Stewart Pinchback was the first non-white and first person of African American descent to become governor of a U.S. state...

is sworn in as the first black member of the U.S. House of Representatives. - Disputed gubernatorial election in LouisianaLouisianaLouisiana is a state located in the southern region of the United States of America. Its capital is Baton Rouge and largest city is New Orleans. Louisiana is the only state in the U.S. with political subdivisions termed parishes, which are local governments equivalent to counties...

cause political violence for more than two years. Both Republican and Democratic governors hold inaugurations and certify local officials.

1873

- April 14 – In the Slaughter-House Cases the Supreme Court votes 5–4 for a narrow reading of the Fourteenth AmendmentFourteenth Amendment to the United States ConstitutionThe Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments.Its Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship that overruled the Dred Scott v...

. The court also discusses dual citizenship: State citizens and U.S. citizens. - Easter, the Colfax MassacreColfax massacreThe Colfax massacre or Colfax Riot occurred on Easter Sunday, April 13, 1873, in Colfax, Louisiana, the seat of Grant Parish, during Reconstruction, when white militia attacked freedmen at the Colfax courthouse...

– More than 100 blacks in the Red RiverRed River Parish, LouisianaRed River Parish is a parish located in the U.S. state of Louisiana. Its seat is Coushatta. It was one of the newer parishes created in 1871 by the state legislature under Reconstruction...

area of Louisiana are killed when attacked by white militia after defending Republicans in local office – continuing controversy from gubernatorial election. - Coushatta MassacreCoushatta massacreThe Coushatta Massacre was the result of an attack by the White League, a paramilitary organization composed of white Southern Democrats, on Republican officeholders and freedmen in Coushatta, the parish seat of Red River Parish, Louisiana...

– Republican officeholders are run out of town and murdered by white militia before leaving the state – four of six were relatives of a Louisiana state senator, a northerner who had settled in the South, married into a local family and established a plantation. Five to twenty black witnesses are also killed.

1874

- Founding of paramilitaryParamilitaryA paramilitary is a force whose function and organization are similar to those of a professional military, but which is not considered part of a state's formal armed forces....

groups that act as the "military arm of the Democratic Party": the White LeagueWhite LeagueThe White League was a white paramilitary group started in 1874 that operated to turn Republicans out of office and intimidate freedmen from voting and political organizing. Its first chapter in Grant Parish, Louisiana was made up of many of the Confederate veterans who had participated in the...

in Louisiana and the Red Shirts in Mississippi, and North and South Carolina. They terrorize blacks and Republicans, turning them out of office, killing some, disrupting rallies, and suppressing voting. - September – In New Orleans, continuing political violence erupts related to the still-contested gubernatorial election of 1872. Thousands of the White League armed militia march into New Orleans, then the seat of government, where they outnumber the integrated city police and black state militia forces. They defeat Republican forces and demand that Gov. Kellogg leave office. The Democratic candidate McEnery is installed and White Leaguers occupy the capitol, state house and arsenal. This was called the "Battle of Liberty Place". The White League and McEnery withdraw after three days in advance of federal troops arriving to reinforce the Republican state government.

1875–1899

1875- March 1 – Civil Rights Act of 1875Civil Rights Act of 1875The Civil Rights Act of 1875 was a United States federal law proposed by Senator Charles Sumner and Representative Benjamin F. Butler in 1870...

signed. - unknown – The Mississippi PlanMississippi PlanThe Mississippi Plan of 1875 was devised by the Democratic Party to overthrow the Republican Party in the state of Mississippi by means of organized threats of violence and suppression or purchase of the black vote, in order to regain political control of the legislature and governor's office...

to intimidate blacks and suppress black voter registration and voting.

1876

- July 8 – The Hamburg MassacreHamburg MassacreThe Hamburg Massacre was a key event of South Carolina Reconstruction. Beginning with a dispute over free passage on a public road, this racially motivated incident concluded with the death of seven men...

occurs when local people riot against African Americans who were trying to celebrate the Fourth of July. - varied – White Democrats regain power in many southern state legislatures and pass the first Jim Crow lawsJim Crow lawsThe Jim Crow laws were state and local laws in the United States enacted between 1876 and 1965. They mandated de jure racial segregation in all public facilities, with a supposedly "separate but equal" status for black Americans...

.

1877

- unknown – With the Compromise of 1877Compromise of 1877The Compromise of 1877, also known as the Corrupt Bargain, refers to a purported informal, unwritten deal that settled the disputed 1876 U.S. Presidential election and ended Congressional Reconstruction. Through it, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was awarded the White House over Democrat Samuel J...

, Republican Rutherford B. HayesRutherford B. HayesRutherford Birchard Hayes was the 19th President of the United States . As president, he oversaw the end of Reconstruction and the United States' entry into the Second Industrial Revolution...

withdraws federal troops from the South in exchange for being elected President of the United States, causing the collapse of the last three remaining Republican state governments. The compromise formally ends the Reconstruction era of the United States.

1879

- spring – Thousands of African Americans refuse to live under segregation in the South and migrate to KansasKansasKansas is a US state located in the Midwestern United States. It is named after the Kansas River which flows through it, which in turn was named after the Kansa Native American tribe, which inhabited the area. The tribe's name is often said to mean "people of the wind" or "people of the south...

. They become known as ExodustersExodustersExodusters was a name given to African Americans who fled the Southern United States for Kansas in 1879 and 1880. After the end of Reconstruction, racial oppression and rumors of the reinstitution of slavery led many freedmen to seek a new place to live....

.

1880

- unknown – In Strauder v. West VirginiaStrauder v. West VirginiaStrauder v. West Virginia, , was a United States Supreme Court case about racial discrimination.-Background:At the time, West Virginia excluded African-Americans from juries. Strauder was a Black man who, at trial, had been convicted of murder by an all-white jury...

, the Supreme CourtSupreme Court of the United StatesThe Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

rules that African Americans could not be excluded from juries. - During the 1880s, African Americans in the South reach a peak of numbers in being elected and holding local offices, even while white Democrats are working to assert control at state level.

1881

- April 11 – Spelman Seminary is founded as the Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary.

- July 4 – Booker T. WashingtonBooker T. WashingtonBooker Taliaferro Washington was an American educator, author, orator, and political leader. He was the dominant figure in the African-American community in the United States from 1890 to 1915...

opens the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial InstituteTuskegee UniversityTuskegee University is a private, historically black university located in Tuskegee, Alabama, United States. It is a member school of the Thurgood Marshall Scholarship Fund...

in Tuskegee, AlabamaTuskegee, AlabamaTuskegee is a city in Macon County, Alabama, United States. At the 2000 census the population was 11,846 and is designated a Micropolitan Statistical Area. Tuskegee has been an important site in various stages of African American history....

.

1882

- A biracial populist coalition achieves power in VirginiaVirginiaThe Commonwealth of Virginia , is a U.S. state on the Atlantic Coast of the Southern United States. Virginia is nicknamed the "Old Dominion" and sometimes the "Mother of Presidents" after the eight U.S. presidents born there...

(briefly). The legislature founds the first public college for African Americans, Virginia Normal and Collegiate InstituteVirginia State UniversityVirginia State University is a historically black and land-grant university located north of the Appomattox River in Chesterfield, in the Richmond area. Founded on , Virginia State was the United States's first fully state-supported four-year institution of higher learning for black Americans...

, as well as the first mental hospital for African Americans, both near Petersburg, VirginiaPetersburg, VirginiaPetersburg is an independent city in Virginia, United States located on the Appomattox River and south of the state capital city of Richmond. The city's population was 32,420 as of 2010, predominantly of African-American ethnicity...

. The hospital was established in December 1869, at Howard's Grove Hospital, a former Confederate unit, but is moved to a new campus in 1882.

1884

- unknown – Mark TwainMark TwainSamuel Langhorne Clemens , better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American author and humorist...

's Adventures of Huckleberry FinnAdventures of Huckleberry FinnAdventures of Huckleberry Finn is a novel by Mark Twain, first published in England in December 1884 and in the United States in February 1885. Commonly named among the Great American Novels, the work is among the first in major American literature to be written in the vernacular, characterized by...

is published, featuring the admirable African-American character Jim. - unknown – Judy W. Reed, of Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C.Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly referred to as Washington, "the District", or simply D.C., is the capital of the United States. On July 16, 1790, the United States Congress approved the creation of a permanent national capital as permitted by the U.S. Constitution....

, and Sarah E. Goode, of ChicagoChicagoChicago is the largest city in the US state of Illinois. With nearly 2.7 million residents, it is the most populous city in the Midwestern United States and the third most populous in the US, after New York City and Los Angeles...

, are the first African-American women inventors to receive patents. Signed with an "X", Reed's patent no. 305,474, granted September 23, 1884, is for a dough kneader and roller. Goode's patent for a cabinet bed, patent no. 322,177, is issued on July 14, 1885. Goode, the owner of a Chicago furniture store, invented a folding bed that could be formed into a desk when not in use. - unknown – Ida B. WellsIda B. WellsIda Bell Wells-Barnett was an African American journalist, newspaper editor and, with her husband, newspaper owner Ferdinand L. Barnett, an early leader in the civil rights movement. She documented lynching in the United States, showing how it was often a way to control or punish blacks who...

sues the Chesapeake, Ohio & South Western Railroad Company for its use of segregated "Jim Crow" cars.

1886

- Norris Wright CuneyNorris Wright CuneyNorris Wright Cuney, or simply Wright Cuney, was an American politician, union leader, and African American activist in Texas in the United States. He became active in Galveston politics serving as an alderman and a national Republican delegate...

becomes the chairman of the Texas Republican Party, the most powerful role held by any African American in the South during the 19th century.

1887

- October 3 – The State Normal School for Colored Students, which would become Florida A&M UniversityFlorida A&M UniversityFlorida Agricultural and Mechanical University, commonly known as Florida A&M or FAMU, is a historically black university located in Tallahassee, Florida, United States, the state capital, and is one of eleven member institutions of the State University System of Florida...

, is founded.

1888

- October 16 – In Civil Rights CasesCivil Rights CasesThe Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 , were a group of five similar cases consolidated into one issue for the United States Supreme Court to review...

, the United States Supreme Court strikes down the Civil Rights Act of 1875 as unconstitutional.

1890

- MississippiMississippiMississippi is a U.S. state located in the Southern United States. Jackson is the state capital and largest city. The name of the state derives from the Mississippi River, which flows along its western boundary, whose name comes from the Ojibwe word misi-ziibi...

, with a white Democrat-dominated legislature, passes a new constitution that effectively disfranchises most blacks through voter registration and electoral requirements, e.g., poll taxPoll taxA poll tax is a tax of a portioned, fixed amount per individual in accordance with the census . When a corvée is commuted for cash payment, in effect it becomes a poll tax...

es, residency tests and literacy testLiteracy testA literacy test, in the context of United States political history, refers to the government practice of testing the literacy of potential citizens at the federal level, and potential voters at the state level. The federal government first employed literacy tests as part of the immigration process...

s. This shuts them out of the political process, including service on juries and in local offices. - By 1900 two-thirds of the farmers in the bottomlands of the Mississippi DeltaMississippi DeltaThe Mississippi Delta is the distinctive northwest section of the U.S. state of Mississippi that lies between the Mississippi and Yazoo Rivers. The region has been called "The Most Southern Place on Earth" because of its unique racial, cultural, and economic history...

are African Americans who cleared and bought land after the Civil War.

1892

- unknown – Ida B. WellsIda B. WellsIda Bell Wells-Barnett was an African American journalist, newspaper editor and, with her husband, newspaper owner Ferdinand L. Barnett, an early leader in the civil rights movement. She documented lynching in the United States, showing how it was often a way to control or punish blacks who...

publishes her pamphlet Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.

1895

- September 18 – Booker T. WashingtonBooker T. WashingtonBooker Taliaferro Washington was an American educator, author, orator, and political leader. He was the dominant figure in the African-American community in the United States from 1890 to 1915...

delivers his Atlanta CompromiseAtlanta CompromiseThe Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition Speech was an address on the topic of race relations given by Booker T. Washington on September 18, 1895...

address at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, Georgia. - unknown – * W. E. B. Du Bois is the first African-American to be awarded a Ph.D by Harvard UniversityHarvard UniversityHarvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

.

1896

- May 18 – In Plessy v. FergusonPlessy v. FergusonPlessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 , is a landmark United States Supreme Court decision in the jurisprudence of the United States, upholding the constitutionality of state laws requiring racial segregation in private businesses , under the doctrine of "separate but equal".The decision was handed...

, the Supreme CourtSupreme Court of the United StatesThe Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

upholds de jureDe jureDe jure is an expression that means "concerning law", as contrasted with de facto, which means "concerning fact".De jure = 'Legally', De facto = 'In fact'....

racial segregationRacial segregationRacial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

of "separate but equalSeparate but equalSeparate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law that justified systems of segregation. Under this doctrine, services, facilities and public accommodations were allowed to be separated by race, on the condition that the quality of each group's public facilities was to...

" facilities. (see Jim Crow lawsJim Crow lawsThe Jim Crow laws were state and local laws in the United States enacted between 1876 and 1965. They mandated de jure racial segregation in all public facilities, with a supposedly "separate but equal" status for black Americans...

for historical discussion). - unknown – The National Association of Colored WomenNational Association of Colored WomenThe National Association of Colored Women Clubs was established in Washington, D.C., USA, by the merger in 1896 of the National Federation of Afro-American Women, the Women's Era Club of Boston, and the National League of Colored Women of Washington, DC, as well as smaller organizations that had...

is formed by the merger of smaller groups. - unknown – As one of the earliest Black Hebrew IsraelitesBlack Hebrew IsraelitesBlack Hebrew Israelites are groups of people mostly of Black African ancestry situated mainly in the United States who believe they are descendants of the ancient Israelites. Black Hebrews adhere in varying degrees to the religious beliefs and practices of mainstream Judaism...

in the United States, William Saunders CrowdyWilliam Saunders CrowdyWilliam Saunders Crowdy was an American soldier, preacher, entrepreneur, theologian, and pastor. As one of the earliest Black Hebrew Israelites in the United States, he established the Church of God and Saints of Christ in 1896.-Early life:In 1847, William Saunders Crowdy was born into slavery at...

re-establishes the Church of God and Saints of ChristChurch of God and Saints of ChristThe Church of God and Saints of Christ is a Hebrew Israelite religious group established in Lawrence, Kansas, by William Saunders Crowdy in 1896. William Crowdy began congregations in several cities in the Midwestern and Eastern United States, and sent an emissary to organize locations in at least...

. - unknown – George Washington CarverGeorge Washington CarverGeorge Washington Carver , was an American scientist, botanist, educator, and inventor. The exact day and year of his birth are unknown; he is believed to have been born into slavery in Missouri in January 1864....

is invited by Booker T. Washington to head the Agricultural Department at what would become Tuskegee UniversityTuskegee UniversityTuskegee University is a private, historically black university located in Tuskegee, Alabama, United States. It is a member school of the Thurgood Marshall Scholarship Fund...

. His work would revolutionize farming – he found about 300 uses for peanuts.

1898

- unknown – LouisianaLouisianaLouisiana is a state located in the southern region of the United States of America. Its capital is Baton Rouge and largest city is New Orleans. Louisiana is the only state in the U.S. with political subdivisions termed parishes, which are local governments equivalent to counties...

enacts the first state-wide grandfather clauseGrandfather clauseGrandfather clause is a legal term used to describe a situation in which an old rule continues to apply to some existing situations, while a new rule will apply to all future situations. It is often used as a verb: to grandfather means to grant such an exemption...

that provides exemption for illiterate whites to voter registration literacy test requirements. - unknown – In Williams v. MississippiWilliams v. MississippiWilliams v. Mississippi, 170 U.S. 213 is a United States Supreme Court case that reviewed provisions of the state constitution that set requirements for voter registration...

the Supreme CourtSupreme Court of the United StatesThe Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...