Gebhart v. Belton

Encyclopedia

Gebhart v. Belton, 33 Del. Ch. 144, 87 A.2d 862 (Del. Ch. 1952), aff'd, 91 A.2d 137 (Del. 1952)

, was a case decided by the Delaware Court of Chancery

in 1952 and affirmed by the Delaware Supreme Court

in the same year. Gebhart was one of the five cases combined into Brown v. Board of Education

, the 1954 decision of the United States Supreme Court which found unconstitutional racial segregation

in United States public school

s.

Gebhart is unique among the four Brown cases in that the trial court ordered that African-American children be admitted to the state's segregated whites-only schools, and the state Supreme Court

affirmed the trial court's decision. In the remaining Brown cases, the state courts found segregation lawful.

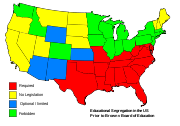

The unusual status of Gebhart arose in large part because of Delaware's unique legal and historical position. At the time of the litigation, Delaware was one of 17 states with a segregated school system. Even though Delaware is nominally a northern state, and was mostly aligned with the Union during the American Civil War

The unusual status of Gebhart arose in large part because of Delaware's unique legal and historical position. At the time of the litigation, Delaware was one of 17 states with a segregated school system. Even though Delaware is nominally a northern state, and was mostly aligned with the Union during the American Civil War

, it nonetheless was de facto and de jure segregated; Jim Crow laws

persisted in the state well into the 1940s, and its educational system was segregated by operation of law. In fact, Delaware's segregation was literally written into the state constitution, which, while providing at Article X, Section 2, that "no distinction shall be made on account of race or color", nonetheless required that "separate schools for white and colored children shall be maintained." Furthermore, a 1935 state education law required:

Despite this optimistic language, African-American schools in Delaware were generally decrepit, with poor facilities, substandard curricula, and shoddy construction. Without substantial financial support provided by Wilmington's Du Pont family

Despite this optimistic language, African-American schools in Delaware were generally decrepit, with poor facilities, substandard curricula, and shoddy construction. Without substantial financial support provided by Wilmington's Du Pont family

of chemical fame, segregated schools would likely have been in even worse shape.

At the same time, as a remnant of its days as one of the original thirteen former British colonies

, Delaware had developed a judicial system which included a separate Court of Chancery

, hearing matters arising in equity rather than in law

. As opposed to legal remedies, which usually involve awarding money as damages

, equity—as expressed in the maxims of equity

, "regards as done that which ought to be done." As a result, cases brought in equity generally seek relief which cannot be awarded as a sum of money, but rather "that which ought to be done".

. Despite the existence of a well-maintained, spacious high school in Claymont, segregation forced the parents to send their children on a public bus to attend the run-down Howard High School

in downtown Wilmington

. Howard High School was Delaware's sole business and college-preparatory school for African-American students, and served the entire state of Delaware. Related concerns involved class size, teacher qualifications, and curriculum; indeed, Howard students interested in vocational training were required to walk several blocks to a nearby annex to attend classes offered only after the conclusion of the normal school day.

. Mrs. Bulah's daughter, Shirley, had been denied admission to the modern, whites-only Hockessin School No. 29, and instead was compelled to attend a one-room "colored" school, Hockessin School No. 107, which, though very near School No. 29, had vastly inferior facilities and construction. Moreover, Shirley Bulah was required to walk to school every day, even though a school bus serving the nearby whites-only school passed by her house every day. Mrs. Bulah had attempted to obtain transportation for Shirley on that bus, but she was told they would never transport an African-American student.

by lawyer

s Jack Greenberg

and Louis L. Redding

under a strategy formulated by Robert L. Carter

of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Redding was the first African-American attorney in the history of Delaware and had developed a notable civil-rights practice in his years before the bar. Frequently, he would be sought out by families unable to afford his services, offering his assistance anyway. Over the years, Redding had developed a reputation as a skilled advocate for racial equality, most notably in Parker v. University of Delaware, 75 A.2d 225 (Del. Ch. 1950), which resulted in a ruling from the Court of Chancery that segregation at the University of Delaware

was unconstitutional. The prospect of Southern-style segregation being adjudicated by a court of equity which had previously expressed an opinion prohibiting racial segregation was clearly attractive to Greenberg and Redding.

Presiding over the Gebhart trial was Chancellor Collins J. Seitz

, who had issued the Parker opinion the prior year. In 1946, at the age of 35, Seitz had been appointed to the Court of Chancery, making him the youngest judge in the history of Delaware. Just prior to the Gebhart litigation, Seitz had given a graduation speech at a local Catholic boys' high school, in which he discussed the courage that would be required to address "a subject that was one of Delaware's great taboos -- the subjugated state of its Negroes. How can we say that we deeply revere the principles of our Declaration [of Independence] and our Constitution and yet refuse to recognize these principles when they are applied to the American Negro in a down-to-earth fashion?"

The plaintiffs presented evidence throughout the course of the trial demonstrating the patently inferior conditions of the Wilmington and Hockessin schools, consisting of testimony and documentary evidence of the schools' infrastructures. In addition, the plaintiffs offered expert testimony from psychologist

s, psychiatrist

s, anthropologists

, and sociologists

-- none of which was rebutted by the defense—demonstrating that the inadequate educational facilities and curricula found in segregated schools were harmful to the mental health of African-American children.

Dramatically illustrating the disparate conditions in the schools were fire insurance valuations prepared by the State of Delaware in 1941, which featured photographs of all Delaware public schools as well as their assessed value. For example, the "colored" school in Hockessin was valued at only $6,250.00, while the whites-only Hockessin school was valued almost seven times higher. The most powerful evidence, however, probably came from the plaintiffs themselves, who described the conditions in their segregated schools and the hardship they were forced to endure to attend those schools in lieu of the much nicer, and more convenient, whites-only schools.

In summary, the plaintiffs argued that:

law had already been adopted by the United States Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson

, and that he did not feel able, as a judge of an inferior court, to "reject a principle of United States constitutional law which has been adopted by fair implication by the highest court of the land." For this reason, the Court refused to find that the segregated schools violated the Fourteenth Amendment, but not by any means on the merits of the system; as the Court observed, "I believe the 'separate but equal' doctrine in education should be rejected, but I also believe its rejection must come from [the U.S. Supreme] [C]ourt."

That, however, did not end the Court's analysis. The Court found that the separate "colored" facilities were in no way equal to the whites-only facilities, and, exercising the broad powers of a court of equity, ordered that African-American students be immediately integrated.

Chancellor Seitz decried the inequal conditions of the plaintiffs' schools in strong terms:

With regard to the Hockessin schools at issue in Bulah, the Court noted similar disparities demonstrating a lack of equal treatment:

Despite the decision made by Chancellor Seitz and upheld by the Delaware Supreme Court, the two schools of Hockessin Elementary and Claymont High School would not have integrated in 1952 because the State Board of Education did not give these schools an official mandate to do so. The Claymont High Board of Education met on September 3, 1952 and decided they would enroll the black students even without a mandate. At the last minute the State Board of Education called and gave a verbal mandate for the children to attend. On the morning of September 4, 1952, eleven black students got on their bus and came to Claymont High School and there were no incidents. The next day, Delaware Attorney Young called and told Claymont Superintendent Stahl to "send the children home" because the cases were being appealed and eventually became part of the Brown v. Board case. Superintendent Stahl and the School Board refused to send the children home, because they wanted the school to be integrated and had worked hard to have integration occur through the court systems. After many meetings, the State School Board agreed to allow the students remain in Claymont, Hockessin and Arden. No other public schools in Delaware were permitted to integrate until after the Brown v. Board decision was decided.

After the Brown decision, a sea change occurred in American and Delaware politics

After the Brown decision, a sea change occurred in American and Delaware politics

and society

. In Delaware, most were willing to accept the Supreme Court's mandate, but some holdouts were to be found in the southern portion of the state. The state Department of Public Instruction agreed to integrate all Delaware schools in light of the Supreme Court's order. However, on September 27, 1954, as African-American students were preparing to enroll at the previously all-white Milford High School in Milford, Delaware

, unrest from angry townspeople was feared to be imminent. In response, Louis Redding issued an urgent telegram to Delaware Governor J. Caleb Boggs

requesting the presence of state police officers "adequate to assure personal safety of eleven children whose admittance to that school last night was confirmed by state board of education." Redding closed his telegram with an optimistic line: "Hope also no occasion for powers of the police will arise."

The end result of the Gebhart and Brown litigation was that Delaware—a state which by no means had suffered the intense vagaries of segregation like some states in the South—became fully integrated, albeit with time and much effort. Unfortunately, some argue that while the state of race relations was dramatically improving post-Brown, any progress was destroyed in the wake of the riot

ing which broke out in Wilmington in April 1968 in the wake of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis

. Delaware's response to the Wilmington riots was notoriously heavy-handed, involving the virtual occupation of the city for over one year by the Delaware National Guard

.

For his efforts in defeating segregation, Louis Redding was honored with a life-size bronze statue of him embracing a young African-American schoolboy and a young white schoolgirl outside the City-County government complex, also named for him, in downtown Wilmington.

Case citation

Case citation is the system used in many countries to identify the decisions in past court cases, either in special series of books called reporters or law reports, or in a 'neutral' form which will identify a decision wherever it was reported...

, was a case decided by the Delaware Court of Chancery

Delaware Court of Chancery

The Delaware Court of Chancery is a court of equity in the American state of Delaware. It is one of Delaware's three constitutional courts, along with the Supreme Court and Superior Court.-Jurisdiction:...

in 1952 and affirmed by the Delaware Supreme Court

Delaware Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of Delaware is the sole appellate court in the United States' state of Delaware. Because Delaware is a popular haven for corporations, the Court has developed a worldwide reputation as a respected source of corporate law decisions, particularly in the area of mergers and...

in the same year. Gebhart was one of the five cases combined into Brown v. Board of Education

Brown v. Board of Education

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 , was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students unconstitutional. The decision overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 which...

, the 1954 decision of the United States Supreme Court which found unconstitutional racial segregation

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

in United States public school

Public education

State schools, also known in the United States and Canada as public schools,In much of the Commonwealth, including Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United Kingdom, the terms 'public education', 'public school' and 'independent school' are used for private schools, that is, schools...

s.

Gebhart is unique among the four Brown cases in that the trial court ordered that African-American children be admitted to the state's segregated whites-only schools, and the state Supreme Court

State supreme court

In the United States, the state supreme court is the highest state court in the state court system ....

affirmed the trial court's decision. In the remaining Brown cases, the state courts found segregation lawful.

Background

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

, it nonetheless was de facto and de jure segregated; Jim Crow laws

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws in the United States enacted between 1876 and 1965. They mandated de jure racial segregation in all public facilities, with a supposedly "separate but equal" status for black Americans...

persisted in the state well into the 1940s, and its educational system was segregated by operation of law. In fact, Delaware's segregation was literally written into the state constitution, which, while providing at Article X, Section 2, that "no distinction shall be made on account of race or color", nonetheless required that "separate schools for white and colored children shall be maintained." Furthermore, a 1935 state education law required:

The schools provided shall be of two kinds; those for white children and those for colored children. The schools for white children shall be free for all white children between the ages of six and twenty-one years, inclusive; and the schools for colored children shall be free to all colored children between the ages of six and twenty-one years, inclusive. ... The State Board of Education shall establish schools for children of people called Moors or Indians.

Du Pont family

The Du Pont family is an American family descended from Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours . The son of a Paris watchmaker and a member of a Burgundian noble family, he and his sons, Victor Marie du Pont and Eleuthère Irénée du Pont, emigrated to the United States in 1800 and used the resources of...

of chemical fame, segregated schools would likely have been in even worse shape.

At the same time, as a remnant of its days as one of the original thirteen former British colonies

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were English and later British colonies established on the Atlantic coast of North America between 1607 and 1733. They declared their independence in the American Revolution and formed the United States of America...

, Delaware had developed a judicial system which included a separate Court of Chancery

Court of Chancery

The Court of Chancery was a court of equity in England and Wales that followed a set of loose rules to avoid the slow pace of change and possible harshness of the common law. The Chancery had jurisdiction over all matters of equity, including trusts, land law, the administration of the estates of...

, hearing matters arising in equity rather than in law

Law

Law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social institutions to govern behavior, wherever possible. It shapes politics, economics and society in numerous ways and serves as a social mediator of relations between people. Contract law regulates everything from buying a bus...

. As opposed to legal remedies, which usually involve awarding money as damages

Damages

In law, damages is an award, typically of money, to be paid to a person as compensation for loss or injury; grammatically, it is a singular noun, not plural.- Compensatory damages :...

, equity—as expressed in the maxims of equity

Maxims of equity

The maxims of equity evolved, in Latin and eventually translated into English, as the principles applied by courts of equity in deciding cases before them.Among the traditional maxims are:-Equity regards done what ought to be done:...

, "regards as done that which ought to be done." As a result, cases brought in equity generally seek relief which cannot be awarded as a sum of money, but rather "that which ought to be done".

The disputes

Gebhart involved two separate actions which were consolidated for the purposes of trial.Belton v. Gebhart

Belton v. Gebhart was brought by Ethel Belton and six other parents of eight African-American high-school students who lived in Claymont, DelawareClaymont, Delaware

Claymont is a census-designated place in New Castle County, Delaware, United States. The population was 9,220 at the 2000 census.-History:...

. Despite the existence of a well-maintained, spacious high school in Claymont, segregation forced the parents to send their children on a public bus to attend the run-down Howard High School

Howard High School of Technology

Howard High School of Technology is a vocational-technical high school in Wilmington, Delaware and is the oldest of four high schools within the New Castle County Vocational-Technical School District, which includes Delcastle Technical High School in Newport, Hodgson Vo-Tech High School in Glasgow,...

in downtown Wilmington

Wilmington, Delaware

Wilmington is the largest city in the state of Delaware, United States, and is located at the confluence of the Christina River and Brandywine Creek, near where the Christina flows into the Delaware River. It is the county seat of New Castle County and one of the major cities in the Delaware Valley...

. Howard High School was Delaware's sole business and college-preparatory school for African-American students, and served the entire state of Delaware. Related concerns involved class size, teacher qualifications, and curriculum; indeed, Howard students interested in vocational training were required to walk several blocks to a nearby annex to attend classes offered only after the conclusion of the normal school day.

Bulah v. Gebhart

Bulah v. Gebhart was brought by Sarah Bulah, a resident of the rural town of Hockessin, DelawareHockessin, Delaware

Hockessin is a census-designated place in New Castle County, Delaware, United States. The population was 12,902 at the 2000 census. The place name may be derived from the Lenape word "hòkèsa" meaning "pieces of bark" or from a misspelling of "occasion," as pronounced by the Quakers who settled...

. Mrs. Bulah's daughter, Shirley, had been denied admission to the modern, whites-only Hockessin School No. 29, and instead was compelled to attend a one-room "colored" school, Hockessin School No. 107, which, though very near School No. 29, had vastly inferior facilities and construction. Moreover, Shirley Bulah was required to walk to school every day, even though a school bus serving the nearby whites-only school passed by her house every day. Mrs. Bulah had attempted to obtain transportation for Shirley on that bus, but she was told they would never transport an African-American student.

The trial

Gebhart was filed in 1951 in the Delaware Court of ChanceryDelaware Court of Chancery

The Delaware Court of Chancery is a court of equity in the American state of Delaware. It is one of Delaware's three constitutional courts, along with the Supreme Court and Superior Court.-Jurisdiction:...

by lawyer

Lawyer

A lawyer, according to Black's Law Dictionary, is "a person learned in the law; as an attorney, counsel or solicitor; a person who is practicing law." Law is the system of rules of conduct established by the sovereign government of a society to correct wrongs, maintain the stability of political...

s Jack Greenberg

Jack Greenberg (lawyer)

Jack Greenberg is an American attorney and legal scholar. He was the Director-Counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund from 1961 to 1984, succeeding Thurgood Marshall....

and Louis L. Redding

Louis L. Redding

Louis Lorenzo Redding was a prominent lawyer and civil rights advocate from Wilmington, Delaware. Redding, the first African American to be admitted to the Delaware bar, was part of the NAACP legal team that challenged school segregation in the Brown v. Board of Education case in front of the U.S...

under a strategy formulated by Robert L. Carter

Robert L. Carter

Robert Lee Carter is a U.S. civil rights activist and judge.-Personal history and early life:Robert Lee Carter was born on March 11, 1917, in Careyville, Florida. While still very young, his mother moved north to Newark, New Jersey, where he was raised...

of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Redding was the first African-American attorney in the history of Delaware and had developed a notable civil-rights practice in his years before the bar. Frequently, he would be sought out by families unable to afford his services, offering his assistance anyway. Over the years, Redding had developed a reputation as a skilled advocate for racial equality, most notably in Parker v. University of Delaware, 75 A.2d 225 (Del. Ch. 1950), which resulted in a ruling from the Court of Chancery that segregation at the University of Delaware

University of Delaware

The university is organized into seven colleges:* College of Agriculture and Natural Resources* College of Arts and Sciences* Alfred Lerner College of Business and Economics* College of Earth, Ocean and Environment* College of Education and Human Development...

was unconstitutional. The prospect of Southern-style segregation being adjudicated by a court of equity which had previously expressed an opinion prohibiting racial segregation was clearly attractive to Greenberg and Redding.

Presiding over the Gebhart trial was Chancellor Collins J. Seitz

Collins J. Seitz

Collins Jacques Seitz was a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit from 1966 until his death in 1998....

, who had issued the Parker opinion the prior year. In 1946, at the age of 35, Seitz had been appointed to the Court of Chancery, making him the youngest judge in the history of Delaware. Just prior to the Gebhart litigation, Seitz had given a graduation speech at a local Catholic boys' high school, in which he discussed the courage that would be required to address "a subject that was one of Delaware's great taboos -- the subjugated state of its Negroes. How can we say that we deeply revere the principles of our Declaration [of Independence] and our Constitution and yet refuse to recognize these principles when they are applied to the American Negro in a down-to-earth fashion?"

The plaintiffs presented evidence throughout the course of the trial demonstrating the patently inferior conditions of the Wilmington and Hockessin schools, consisting of testimony and documentary evidence of the schools' infrastructures. In addition, the plaintiffs offered expert testimony from psychologist

Psychologist

Psychologist is a professional or academic title used by individuals who are either:* Clinical professionals who work with patients in a variety of therapeutic contexts .* Scientists conducting psychological research or teaching psychology in a college...

s, psychiatrist

Psychiatrist

A psychiatrist is a physician who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders. All psychiatrists are trained in diagnostic evaluation and in psychotherapy...

s, anthropologists

Anthropology

Anthropology is the study of humanity. It has origins in the humanities, the natural sciences, and the social sciences. The term "anthropology" is from the Greek anthrōpos , "man", understood to mean mankind or humanity, and -logia , "discourse" or "study", and was first used in 1501 by German...

, and sociologists

Sociology

Sociology is the study of society. It is a social science—a term with which it is sometimes synonymous—which uses various methods of empirical investigation and critical analysis to develop a body of knowledge about human social activity...

-- none of which was rebutted by the defense—demonstrating that the inadequate educational facilities and curricula found in segregated schools were harmful to the mental health of African-American children.

Dramatically illustrating the disparate conditions in the schools were fire insurance valuations prepared by the State of Delaware in 1941, which featured photographs of all Delaware public schools as well as their assessed value. For example, the "colored" school in Hockessin was valued at only $6,250.00, while the whites-only Hockessin school was valued almost seven times higher. The most powerful evidence, however, probably came from the plaintiffs themselves, who described the conditions in their segregated schools and the hardship they were forced to endure to attend those schools in lieu of the much nicer, and more convenient, whites-only schools.

In summary, the plaintiffs argued that:

- Segregated schools violated the Fourteenth AmendmentFourteenth Amendment to the United States ConstitutionThe Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments.Its Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship that overruled the Dred Scott v...

of the United States ConstitutionUnited States ConstitutionThe Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It is the framework for the organization of the United States government and for the relationship of the federal government with the states, citizens, and all people within the United States.The first three...

, in that they did not offer African-American children equal protection of the law; but, if not, then: - The separate facilities and educational opportunities offered to African-American children were not equal to those furnished to white children similarly situated.

The decision

Initially, Chancellor Seitz noted that the separate but equalSeparate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law that justified systems of segregation. Under this doctrine, services, facilities and public accommodations were allowed to be separated by race, on the condition that the quality of each group's public facilities was to...

law had already been adopted by the United States Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson

Plessy v. Ferguson

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 , is a landmark United States Supreme Court decision in the jurisprudence of the United States, upholding the constitutionality of state laws requiring racial segregation in private businesses , under the doctrine of "separate but equal".The decision was handed...

, and that he did not feel able, as a judge of an inferior court, to "reject a principle of United States constitutional law which has been adopted by fair implication by the highest court of the land." For this reason, the Court refused to find that the segregated schools violated the Fourteenth Amendment, but not by any means on the merits of the system; as the Court observed, "I believe the 'separate but equal' doctrine in education should be rejected, but I also believe its rejection must come from [the U.S. Supreme] [C]ourt."

That, however, did not end the Court's analysis. The Court found that the separate "colored" facilities were in no way equal to the whites-only facilities, and, exercising the broad powers of a court of equity, ordered that African-American students be immediately integrated.

Chancellor Seitz decried the inequal conditions of the plaintiffs' schools in strong terms:

I now consider whether the facilities of the [Claymont and Howard] institutions are separate but equal, within the requirements of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Are the separate facilities and educational opportunities offered to these Negro plaintiffs, and those similarly situated, "equal" in the constitutional sense, to those available at Claymont High to white children, similarly situated? The answer to this question is often much more difficult than appears, because many of the factors to be compared are just not susceptible of mathematical evaluation, e. g., aesthetic considerations. Moreover, and of real importance, the United States Supreme Court has not decided what should be done if a Negro school being compared with a white school is inferior in some respects and superior in others. It is easy, as some courts do, to talk about the necessity for finding substantial equality. But, under this approach, how is one to deal with a situation where, as here, the mental and physical health services at the Negro school are superior to those offered at the white school while the teacher load at the Negro school is not only substantially heavier than that at the white school, but often exceeds the State announced educationally desirable maximum teacher-pupil ratio. The answer, it seems to me is this: Where the facilities or educational opportunities available to the Negro are, as to any substantial factor, inferior to those available to white children similarly situated, the constitutional principle of "separate but equal" is violated, even though the State may point to other factors as to which the Negro school is superior. I reach this conclusion because I do not believe a court can say that the substantial factor as to which the Negro school is inferior will not adversely affect the educational progress of at least some of those concerned. Moreover, evaluating unlike factors is unrealistic. If this be a harsh test, then I answer that a State which divides its citizens should pay the price.

With regard to the Hockessin schools at issue in Bulah, the Court noted similar disparities demonstrating a lack of equal treatment:

Another factor connected with these two schools demands separate attention, because it is a consequence of segregation so outlandish that the Attorney General, with commendable candor, has in effect refused to defend it. I refer to the fact that school bus transportation is provided those attending No. 29 who, except for color, are in the same situation as this infant plaintiff. Yet neither school bus transportation, nor its equivalent is provided this plaintiff even to attend No. 107. In fact, the State Board of Education refused to authorize the transportation of this then seven year old plaintiff to the Negro school, even though the bus for white children went right past her home, and even though the two schools are no more than a mile apart. Moreover, there is no public transportation available from or near plaintiff's home to or near the Negro school. The State Board ruled that because of the State constitutional provision for separate schools, a Negro child may not ride in a bus serving a white school. If we assume that this is so, then this practice in and of itself, is another reason why the facilities offered this plaintiff at No. 107 are inferior to those provided at No. 29. To suggest, under the facts here presented, that there are not enough Negroes to warrant the cost of a school bus for them is only another way of saying that they are not entitled to equal services because they are Negroes. Such an excuse will not do here.

I conclude that the facilities and educational opportunities at No. 107 are substantially inferior in a constitutional sense, to those at No. 29. For the reasons stated in connection with Claymont I do not believe the relief should merely be an order to make equal. An injunction will issue preventing the defendants and their agents from refusing these plaintiffs, and those similarly situated, admission to School No. 29 because of their color.

Despite the decision made by Chancellor Seitz and upheld by the Delaware Supreme Court, the two schools of Hockessin Elementary and Claymont High School would not have integrated in 1952 because the State Board of Education did not give these schools an official mandate to do so. The Claymont High Board of Education met on September 3, 1952 and decided they would enroll the black students even without a mandate. At the last minute the State Board of Education called and gave a verbal mandate for the children to attend. On the morning of September 4, 1952, eleven black students got on their bus and came to Claymont High School and there were no incidents. The next day, Delaware Attorney Young called and told Claymont Superintendent Stahl to "send the children home" because the cases were being appealed and eventually became part of the Brown v. Board case. Superintendent Stahl and the School Board refused to send the children home, because they wanted the school to be integrated and had worked hard to have integration occur through the court systems. After many meetings, the State School Board agreed to allow the students remain in Claymont, Hockessin and Arden. No other public schools in Delaware were permitted to integrate until after the Brown v. Board decision was decided.

The aftermath

The State Attorney General appealed Chancellor Seitz' decision in Gebhart to the Delaware Supreme Court. The plaintiffs, believing the Court of Chancery had not gone far enough in overturning the concept of "separate but equal", cross-appealed. The Supreme Court affirmed the decision in a relatively short opinion. From there, the school-district defendants appealed to the United States Supreme Court, where the consolidation with Brown occurred.

Politics

Politics is a process by which groups of people make collective decisions. The term is generally applied to the art or science of running governmental or state affairs, including behavior within civil governments, but also applies to institutions, fields, and special interest groups such as the...

and society

Society

A society, or a human society, is a group of people related to each other through persistent relations, or a large social grouping sharing the same geographical or virtual territory, subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations...

. In Delaware, most were willing to accept the Supreme Court's mandate, but some holdouts were to be found in the southern portion of the state. The state Department of Public Instruction agreed to integrate all Delaware schools in light of the Supreme Court's order. However, on September 27, 1954, as African-American students were preparing to enroll at the previously all-white Milford High School in Milford, Delaware

Milford, Delaware

Milford is a city in Kent and Sussex counties in the U.S. state of Delaware. According to the 2010 census, the population of the city is 9,559....

, unrest from angry townspeople was feared to be imminent. In response, Louis Redding issued an urgent telegram to Delaware Governor J. Caleb Boggs

J. Caleb Boggs

James Caleb "Cale" Boggs was an American lawyer and politician from Claymont, in New Castle County, Delaware. He was a veteran of World War II, and a member of the Republican Party, who served three terms as U.S. Representative from Delaware, two terms as Governor of Delaware, and two terms as...

requesting the presence of state police officers "adequate to assure personal safety of eleven children whose admittance to that school last night was confirmed by state board of education." Redding closed his telegram with an optimistic line: "Hope also no occasion for powers of the police will arise."

The end result of the Gebhart and Brown litigation was that Delaware—a state which by no means had suffered the intense vagaries of segregation like some states in the South—became fully integrated, albeit with time and much effort. Unfortunately, some argue that while the state of race relations was dramatically improving post-Brown, any progress was destroyed in the wake of the riot

Riot

A riot is a form of civil disorder characterized often by what is thought of as disorganized groups lashing out in a sudden and intense rash of violence against authority, property or people. While individuals may attempt to lead or control a riot, riots are thought to be typically chaotic and...

ing which broke out in Wilmington in April 1968 in the wake of the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis

Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the southwestern corner of the U.S. state of Tennessee, and the county seat of Shelby County. The city is located on the 4th Chickasaw Bluff, south of the confluence of the Wolf and Mississippi rivers....

. Delaware's response to the Wilmington riots was notoriously heavy-handed, involving the virtual occupation of the city for over one year by the Delaware National Guard

Delaware National Guard

The Delaware National Guard consists of the:*Delaware Army National Guard*Delaware Air National Guard-External links:* compiled by the United States Army Center of Military History*...

.

For his efforts in defeating segregation, Louis Redding was honored with a life-size bronze statue of him embracing a young African-American schoolboy and a young white schoolgirl outside the City-County government complex, also named for him, in downtown Wilmington.