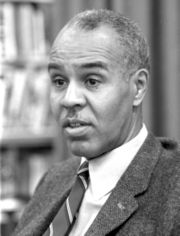

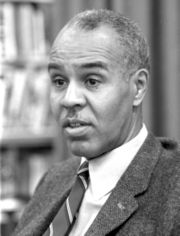

Roy Wilkins

Encyclopedia

Roy Wilkins was a prominent civil rights

activist in the United States

from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins' most notable role was in his leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

, Wilkins graduated from the University of Minnesota

with a degree in sociology

in 1923. He worked as a journalist

at The Minnesota Daily and became editor of St. Paul Appeal, an African-American

newspaper

. After he graduated he became the editor of the The Call (Kansas City)

. In 1929, he married social worker Aminda "Minnie" Badeau; the couple had no children.

Between 1931 and 1934, Wilkins was assistant NAACP secretary under Walter Francis White

. When W. E. B. Du Bois left the organization in 1934, he replaced him as editor of The Crisis

, the official magazine of the NAACP. From 1949–50 Wilkins chaired the National Emergency Civil Rights Mobilization, which comprised more than 100 local and national groups.

In 1950, Wilkins—along with A. Philip Randolph

http://www.civilrights.org/about/lccr/founders.html, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

, and Arnold Aronson

http://www.civilrights.org/about/lccr/founders.html, a leader of the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council—founded the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights

(LCCR). LCCR has become the premier civil rights coalition, and has coordinated the national legislative campaign on behalf of every major civil rights law since 1957.

In 1955, Roy Wilkins was chosen to be the executive secretary of the NAACP and in 1964 he became its executive director. He had an excellent reputation as an articulate spokesperson for the civil rights movement. One of his first actions was to provide support to civil rights activists in Mississippi

In 1955, Roy Wilkins was chosen to be the executive secretary of the NAACP and in 1964 he became its executive director. He had an excellent reputation as an articulate spokesperson for the civil rights movement. One of his first actions was to provide support to civil rights activists in Mississippi

who were being subject to a "credit squeeze" by members of the White Citizens Councils.

Wilkins backed a proposal suggested by Dr. T.R.M. Howard of Mound Bayou, Mississippi

, who headed the Regional Council of Negro Leadership

, a leading civil rights organization in the state. Under the plan, black businesses and voluntary associations shifted their accounts to the black-owned Tri-State Bank of Memphis, Tennessee. By the end of 1955, about $280,000 had been deposited in Tri-State for this purpose. The money enabled Tri-State to extend loans to credit-worthy blacks who were denied loans by white banks. Wilkins participated in the March on Washington (August 1963) which he helped organize, the Selma to Montgomery marches

(1965), and the March Against Fear

(1966).

He believed in achieving reform by legislative means, testified before many Congressional

hearings and conferred with Presidents Kennedy

, Johnson, Nixon

, Ford

, and Carter

. Wilkins strongly opposed militancy in the movement for civil rights as represented by the "black power

" movement. He was a strong critic of racism in any form regardless of its creed, color or political motivation, and also espoused the principles of nonviolence

.

Wilkins was also a member of Omega Psi Phi

, a fraternity with a civil rights focus, and one of the intercollegiate Greek-letter fraternities established for African Americans.

In 1967, Wilkins was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom

by Lyndon Johnson. During his tenure, the NAACP played a pivotal role in leading the nation into the Civil Rights movement and spearheaded the efforts that led to significant civil rights victories, including Brown v. Board of Education

, the Civil Rights Act of 1964

, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In 1968, Wilkins also served as chair of the U.S. delegation to the International Conference on Human Rights.

In 1976, Wilkins got into a dispute with undisclosed board members at the NAACP national convention in Memphis

, Tennessee

. He announced that he was postponing his planned retirement by one year because the package offered was insufficient for his needs. Board member Emmitt Douglas

of Louisiana

demanded that Wilkins disclose the offenders and not impugn the board as a whole. Wilkins merely said that the offenders had "vilified" his reputation and questioned his health and integrity.

In 1977, at the age of seventy-six, Wilkins retired from the NAACP and was succeeded by Benjamin Hooks

. He was honored with the title Director Emeritus of the NAACP

in the same year. Roy Wilkins died on September 8, 1981 in New York City of heart problems related to a pacemaker implanted on him in 1979 due to his irregular heartbeat. In 1982, his autobiography Standing Fast: The Autobiography of Roy Wilkins was published posthumously.

and proponent of American values during the Cold War

, and denounced suspected and actual communists within the civil rights

movement. He has been criticized by some, on the left of the civil rights movement, such as Daisy Bates

, Paul Robeson

, W. E. B. Du Bois, Robert F. Williams

, and Fred Shuttlesworth

, for his cautious approach, his suspicion of grassroots

organizations, and his conciliatory attitude towards white anticommunism.

and the state department, in collusion with the NAACP and Wilkins (then editor of The Crisis

, the official magazine of the NAACP), arranged for a ghost-written leaflet to be printed and distributed in Africa.The purpose of the leaflet was to spread negative press and views about the Black political radical and entertainer Paul Robeson

throughout Africa. Roger P. Ross a State Department public affairs officer working in Africa, issued three pages of detailed guidelines including the following instructions:

The finished article published by the NAACP was called Paul Robeson: Lost Shepherd, penned under the false name of "Robert Alan", whom the NAACP claimed was a "well known New York journalist." Another article by Roy Wilkins, called "Stalin's Greatest Defeat", denounced Robeson as well as the Communist Party of the USA in terms consistent with the FBI's information.:

At the time of Robeson's widely misquoted declaration at The Paris Peace Conference

in 1949, that African Americans would not support the United States in a war with the Soviet Union because of their continued lynchings and second-class citizen

status under law following World War II, Roy Wilkins stated that regardless of the number of lynchings that were occurring or would occur, Black America would always serve in the armed forces. Wilkins also threatened to cancel a charter of an NAACP youth group in 1952 if they did not cancel their planned Robeson concert.

mentioned Wilkins in his most famous spoken word song "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised

" with this lyric: "There will be no slow motion or still life of Roy Wilkins strolling through Watts in a red, black and green liberation jumpsuit that he has been saving for just the proper occasion."

During his later life Wilkins was frequently referred to as the 'Senior Statesman' of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement.

The Roy Wilkins Centre for Human Relations and Human Justice was established in the University of Minnesota

's Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs in 1992.

In 2002, Molefi Kete Asante

listed Roy Wilkins on his list of the 100 Greatest African Americans

.

African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)

The African-American Civil Rights Movement refers to the movements in the United States aimed at outlawing racial discrimination against African Americans and restoring voting rights to them. This article covers the phase of the movement between 1955 and 1968, particularly in the South...

activist in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

from the 1930s to the 1970s. Wilkins' most notable role was in his leadership of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Early career

Born in St. Louis, MissouriSt. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis is an independent city on the eastern border of Missouri, United States. With a population of 319,294, it was the 58th-largest U.S. city at the 2010 U.S. Census. The Greater St...

, Wilkins graduated from the University of Minnesota

University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, Twin Cities is a public research university located in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, United States. It is the oldest and largest part of the University of Minnesota system and has the fourth-largest main campus student body in the United States, with 52,557...

with a degree in sociology

Sociology

Sociology is the study of society. It is a social science—a term with which it is sometimes synonymous—which uses various methods of empirical investigation and critical analysis to develop a body of knowledge about human social activity...

in 1923. He worked as a journalist

Journalist

A journalist collects and distributes news and other information. A journalist's work is referred to as journalism.A reporter is a type of journalist who researchs, writes, and reports on information to be presented in mass media, including print media , electronic media , and digital media A...

at The Minnesota Daily and became editor of St. Paul Appeal, an African-American

African American

African Americans are citizens or residents of the United States who have at least partial ancestry from any of the native populations of Sub-Saharan Africa and are the direct descendants of enslaved Africans within the boundaries of the present United States...

newspaper

Newspaper

A newspaper is a scheduled publication containing news of current events, informative articles, diverse features and advertising. It usually is printed on relatively inexpensive, low-grade paper such as newsprint. By 2007, there were 6580 daily newspapers in the world selling 395 million copies a...

. After he graduated he became the editor of the The Call (Kansas City)

The Call (Kansas City)

Kansas City The Call, or The Call is an African-American newspaper founded in 1919 by Chester A. Franklin. It serves the black community of Kansas City, Missouri and Kansas City, Kansas.-Founder :...

. In 1929, he married social worker Aminda "Minnie" Badeau; the couple had no children.

Between 1931 and 1934, Wilkins was assistant NAACP secretary under Walter Francis White

Walter Francis White

Walter Francis White was a civil rights activist who led the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for almost a quarter of a century and directed a broad program of legal challenges to segregation and disfranchisement. He was also a journalist, novelist, and essayist...

. When W. E. B. Du Bois left the organization in 1934, he replaced him as editor of The Crisis

The Crisis

The Crisis is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People , and was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois , Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Miller, W.S. Braithwaite, M. D. Maclean.The original title of the journal was...

, the official magazine of the NAACP. From 1949–50 Wilkins chaired the National Emergency Civil Rights Mobilization, which comprised more than 100 local and national groups.

In 1950, Wilkins—along with A. Philip Randolph

A. Philip Randolph

Asa Philip Randolph was a leader in the African American civil-rights movement and the American labor movement. He organized and led the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first predominantly Negro labor union. In the early civil-rights movement, Randolph led the March on Washington...

http://www.civilrights.org/about/lccr/founders.html, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was, in 1925, the first labor organization led by blacks to receive a charter in the American Federation of Labor . It merged in 1978 with the Brotherhood of Railway and Airline Clerks , now known as the Transportation Communications International Union.The...

, and Arnold Aronson

Arnold Aronson

Arnold Aronson was a founder of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights and served as its executive secretary from 1950 to 1980. In 1941 he worked with A. Philip Randolph to pressure President Franklin D. Roosevelt to issue Executive Order 8002, opening jobs in the federal bureaucracy and in...

http://www.civilrights.org/about/lccr/founders.html, a leader of the National Jewish Community Relations Advisory Council—founded the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights

Leadership Conference on Civil Rights

The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights , formerly called The Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, is an umbrella group of American civil rights interest groups.-Organizational history:...

(LCCR). LCCR has become the premier civil rights coalition, and has coordinated the national legislative campaign on behalf of every major civil rights law since 1957.

Leading the NAACP

Mississippi

Mississippi is a U.S. state located in the Southern United States. Jackson is the state capital and largest city. The name of the state derives from the Mississippi River, which flows along its western boundary, whose name comes from the Ojibwe word misi-ziibi...

who were being subject to a "credit squeeze" by members of the White Citizens Councils.

Wilkins backed a proposal suggested by Dr. T.R.M. Howard of Mound Bayou, Mississippi

Mound Bayou, Mississippi

Mound Bayou is a city in Bolivar County, Mississippi. The population was 2,102 at the 2000 census. It is notable for having been founded as an independent black community in 1887 by former slaves led by Isaiah Montgomery. By percentage, its 98.4 percent African-American majority population is one...

, who headed the Regional Council of Negro Leadership

Regional Council of Negro Leadership

The Regional Council of Negro Leadership was a society in Mississippi founded by T. R. M. Howard in 1951 to promote a program of civil rights, self-help, and business ownership...

, a leading civil rights organization in the state. Under the plan, black businesses and voluntary associations shifted their accounts to the black-owned Tri-State Bank of Memphis, Tennessee. By the end of 1955, about $280,000 had been deposited in Tri-State for this purpose. The money enabled Tri-State to extend loans to credit-worthy blacks who were denied loans by white banks. Wilkins participated in the March on Washington (August 1963) which he helped organize, the Selma to Montgomery marches

Selma to Montgomery marches

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three marches in 1965 that marked the political and emotional peak of the American civil rights movement. They grew out of the voting rights movement in Selma, Alabama, launched by local African-Americans who formed the Dallas County Voters League...

(1965), and the March Against Fear

March Against Fear

On June 6, 1966, James Meredith started a solitary March Against Fear for 220 miles from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi, to protest against racism. Soon after starting his march he was shot by a sniper with birdshot, injuring him...

(1966).

He believed in achieving reform by legislative means, testified before many Congressional

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

hearings and conferred with Presidents Kennedy

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

, Johnson, Nixon

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961 under...

, Ford

Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph "Jerry" Ford, Jr. was the 38th President of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977, and the 40th Vice President of the United States serving from 1973 to 1974...

, and Carter

Jimmy Carter

James Earl "Jimmy" Carter, Jr. is an American politician who served as the 39th President of the United States and was the recipient of the 2002 Nobel Peace Prize, the only U.S. President to have received the Prize after leaving office...

. Wilkins strongly opposed militancy in the movement for civil rights as represented by the "black power

Black Power

Black Power is a political slogan and a name for various associated ideologies. It is used in the movement among people of Black African descent throughout the world, though primarily by African Americans in the United States...

" movement. He was a strong critic of racism in any form regardless of its creed, color or political motivation, and also espoused the principles of nonviolence

Nonviolence

Nonviolence has two meanings. It can refer, first, to a general philosophy of abstention from violence because of moral or religious principle It can refer to the behaviour of people using nonviolent action Nonviolence has two (closely related) meanings. (1) It can refer, first, to a general...

.

Wilkins was also a member of Omega Psi Phi

Omega Psi Phi

Omega Psi Phi is a fraternity and is the first African-American national fraternal organization to be founded at a historically black college. Omega Psi Phi was founded on November 17, 1911, at Howard University in Washington, D.C.. The founders were three Howard University juniors, Edgar Amos...

, a fraternity with a civil rights focus, and one of the intercollegiate Greek-letter fraternities established for African Americans.

In 1967, Wilkins was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom

Presidential Medal of Freedom

The Presidential Medal of Freedom is an award bestowed by the President of the United States and is—along with thecomparable Congressional Gold Medal bestowed by an act of U.S. Congress—the highest civilian award in the United States...

by Lyndon Johnson. During his tenure, the NAACP played a pivotal role in leading the nation into the Civil Rights movement and spearheaded the efforts that led to significant civil rights victories, including Brown v. Board of Education

Brown v. Board of Education

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 , was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students unconstitutional. The decision overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896 which...

, the Civil Rights Act of 1964

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was a landmark piece of legislation in the United States that outlawed major forms of discrimination against African Americans and women, including racial segregation...

, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In 1968, Wilkins also served as chair of the U.S. delegation to the International Conference on Human Rights.

In 1976, Wilkins got into a dispute with undisclosed board members at the NAACP national convention in Memphis

Memphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in the southwestern corner of the U.S. state of Tennessee, and the county seat of Shelby County. The city is located on the 4th Chickasaw Bluff, south of the confluence of the Wolf and Mississippi rivers....

, Tennessee

Tennessee

Tennessee is a U.S. state located in the Southeastern United States. It has a population of 6,346,105, making it the nation's 17th-largest state by population, and covers , making it the 36th-largest by total land area...

. He announced that he was postponing his planned retirement by one year because the package offered was insufficient for his needs. Board member Emmitt Douglas

Emmitt Douglas

Emmitt James Douglas was an African-American businessman from New Roads, Louisiana, who served as president of his state's National Association for the Advancement of Colored People from 1966 until his death....

of Louisiana

Louisiana

Louisiana is a state located in the southern region of the United States of America. Its capital is Baton Rouge and largest city is New Orleans. Louisiana is the only state in the U.S. with political subdivisions termed parishes, which are local governments equivalent to counties...

demanded that Wilkins disclose the offenders and not impugn the board as a whole. Wilkins merely said that the offenders had "vilified" his reputation and questioned his health and integrity.

In 1977, at the age of seventy-six, Wilkins retired from the NAACP and was succeeded by Benjamin Hooks

Benjamin Hooks

Benjamin Lawson Hooks was an American civil rights leader. A Baptist minister and practicing attorney, he served as executive director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People from 1977 to 1992, and throughout his career was a vocal campaigner for civil rights in the...

. He was honored with the title Director Emeritus of the NAACP

Emeritus

Emeritus is a post-positive adjective that is used to designate a retired professor, bishop, or other professional or as a title. The female equivalent emerita is also sometimes used.-History:...

in the same year. Roy Wilkins died on September 8, 1981 in New York City of heart problems related to a pacemaker implanted on him in 1979 due to his irregular heartbeat. In 1982, his autobiography Standing Fast: The Autobiography of Roy Wilkins was published posthumously.

Views

Wilkins was a staunch liberalLiberalism

Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,...

and proponent of American values during the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

, and denounced suspected and actual communists within the civil rights

Civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from unwarranted infringement by governments and private organizations, and ensure one's ability to participate in the civil and political life of the state without discrimination or repression.Civil rights include...

movement. He has been criticized by some, on the left of the civil rights movement, such as Daisy Bates

Daisy Bates

-People:* Daisy May Bates , Australian journalist, author, amateur anthropologist and lifelong student of Indigenous Australian culture and society...

, Paul Robeson

Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson was an American concert singer , recording artist, actor, athlete, scholar who was an advocate for the Civil Rights Movement in the first half of the twentieth century...

, W. E. B. Du Bois, Robert F. Williams

Robert F. Williams

Robert Franklin Williams was a civil rights leader, the president of the Monroe, North Carolina NAACP chapter in the 1950s and early 1960s, and author. At a time when racial tension was high and official abuses were rampant, Williams was a key figure in promoting both integration and armed black...

, and Fred Shuttlesworth

Fred Shuttlesworth

Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, born Freddie Lee Robinson, was a U.S. civil rights activist who led the fight against segregation and other forms of racism as a minister in Birmingham, Alabama...

, for his cautious approach, his suspicion of grassroots

Grassroots

A grassroots movement is one driven by the politics of a community. The term implies that the creation of the movement and the group supporting it are natural and spontaneous, highlighting the differences between this and a movement that is orchestrated by traditional power structures...

organizations, and his conciliatory attitude towards white anticommunism.

Paul Robeson "Lost Shepherd"

In 1951, J. Edgar HooverJ. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover was the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation of the United States. Appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation—predecessor to the FBI—in 1924, he was instrumental in founding the FBI in 1935, where he remained director until his death in 1972...

and the state department, in collusion with the NAACP and Wilkins (then editor of The Crisis

The Crisis

The Crisis is the official magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People , and was founded in 1910 by W. E. B. Du Bois , Oswald Garrison Villard, J. Max Barber, Charles Edward Russell, Kelly Miller, W.S. Braithwaite, M. D. Maclean.The original title of the journal was...

, the official magazine of the NAACP), arranged for a ghost-written leaflet to be printed and distributed in Africa.The purpose of the leaflet was to spread negative press and views about the Black political radical and entertainer Paul Robeson

Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson was an American concert singer , recording artist, actor, athlete, scholar who was an advocate for the Civil Rights Movement in the first half of the twentieth century...

throughout Africa. Roger P. Ross a State Department public affairs officer working in Africa, issued three pages of detailed guidelines including the following instructions:

"USIE in the Gold Coast, and I suspect everywhere else in Africa, badly needs a through-going, sympathetic and regretful but straight talking treatment of the whole Robeson episode...there's no way the Communists score on us more easily and more effectively out here, than on the US. Negro problem in general, and on the Robeson case in particular. And, answering the latter, we go a long way toward answering the former."

The finished article published by the NAACP was called Paul Robeson: Lost Shepherd, penned under the false name of "Robert Alan", whom the NAACP claimed was a "well known New York journalist." Another article by Roy Wilkins, called "Stalin's Greatest Defeat", denounced Robeson as well as the Communist Party of the USA in terms consistent with the FBI's information.:

At the time of Robeson's widely misquoted declaration at The Paris Peace Conference

Paris Peace Treaties, 1947

The Paris Peace Conference resulted in the Paris Peace Treaties signed on February 10, 1947. The victorious wartime Allied powers negotiated the details of treaties with Italy, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Finland .The...

in 1949, that African Americans would not support the United States in a war with the Soviet Union because of their continued lynchings and second-class citizen

Second-class citizen

Second-class citizen is an informal term used to describe a person who is systematically discriminated against within a state or other political jurisdiction, despite their nominal status as a citizen or legal resident there...

status under law following World War II, Roy Wilkins stated that regardless of the number of lynchings that were occurring or would occur, Black America would always serve in the armed forces. Wilkins also threatened to cancel a charter of an NAACP youth group in 1952 if they did not cancel their planned Robeson concert.

Legacy

Gil Scott-HeronGil Scott-Heron

Gilbert "Gil" Scott-Heron was an American soul and jazz poet, musician, and author known primarily for his work as a spoken word performer in the 1970s and '80s...

mentioned Wilkins in his most famous spoken word song "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised

The Revolution Will Not Be Televised

"The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" is a poem and song by Gil Scott-Heron. Scott-Heron first recorded it for his 1970 album Small Talk at 125th and Lenox, on which he recited the lyrics, accompanied by congas and bongo drums...

" with this lyric: "There will be no slow motion or still life of Roy Wilkins strolling through Watts in a red, black and green liberation jumpsuit that he has been saving for just the proper occasion."

During his later life Wilkins was frequently referred to as the 'Senior Statesman' of the U.S. Civil Rights Movement.

The Roy Wilkins Centre for Human Relations and Human Justice was established in the University of Minnesota

University of Minnesota

The University of Minnesota, Twin Cities is a public research university located in Minneapolis and St. Paul, Minnesota, United States. It is the oldest and largest part of the University of Minnesota system and has the fourth-largest main campus student body in the United States, with 52,557...

's Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs in 1992.

In 2002, Molefi Kete Asante

Molefi Kete Asante

Molefi Kete Asante is an African-American scholar, historian, and philosopher. He is a leading figure in the fields of African American studies, African Studies and Communication Studies...

listed Roy Wilkins on his list of the 100 Greatest African Americans

100 Greatest African Americans

100 Greatest African Americans is a biographical dictionary of the one hundred historically greatest African Americans , as assessed by Molefi Kete Asante in 2002.-Criteria:...

.

See also

- American Civil Rights Movement (1896-1954)American Civil Rights Movement (1896-1954)The Civil Rights Movement in the United States was a long, primarily nonviolent struggle to bring full civil rights and equality under the law to all Americans...

- African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)African-American Civil Rights Movement (1955-1968)The African-American Civil Rights Movement refers to the movements in the United States aimed at outlawing racial discrimination against African Americans and restoring voting rights to them. This article covers the phase of the movement between 1955 and 1968, particularly in the South...

- Leadership Conference on Civil RightsLeadership Conference on Civil RightsThe Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights , formerly called The Leadership Conference on Civil Rights, is an umbrella group of American civil rights interest groups.-Organizational history:...

- Roger WilkinsRoger WilkinsRoger Wilkins is an African American civil rights leader, professor of history, and journalist.-Biography:Wilkins was born in Kansas City, Missouri, and grew up in Michigan...

, nephew of Roy, also a prominent Civil Rights activist - Roy Wilkins AuditoriumRoy Wilkins AuditoriumThe Roy Wilkins Auditorium is a 5,000-seat multi-purpose arena in St. Paul, Minnesota. Designed by renowned African American municipal architect Clarence W. Wigington, it was built in 1932 as the St. Paul Auditorium, and was renamed for Roy Wilkins in 1985...

, an arena in Saint Paul, MinnesotaSaint Paul, MinnesotaSaint Paul is the capital and second-most populous city of the U.S. state of Minnesota. The city lies mostly on the east bank of the Mississippi River in the area surrounding its point of confluence with the Minnesota River, and adjoins Minneapolis, the state's largest city... - Timeline of the American Civil Rights MovementTimeline of the American Civil Rights MovementThis is a timeline of African-American Civil Rights Movement.-Pre-17th century:1565*unknown – The colony of St...

- Thurgood MarshallThurgood MarshallThurgood Marshall was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, serving from October 1967 until October 1991...

, Wilkins colleague at the NAACP and U.S. Supreme Court JusticeSupreme Court of the United StatesThe Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

External links

- The Roy Wilkins Memorial in St. Paul, Minnesota: a virtual tour.

- The Leadership Conference on Civil Rights

- Oral History Interview with Roy Wilkins, from the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library