Military history of the Netherlands

Encyclopedia

The Dutch-speaking people have a long history; the Netherlands as a nation-state

dates from 1568. Belgium (a country with a Dutch-like-speaking majority) became an independent state in 1830 when it seceded from the Netherlands.

During the ancient

and early medieval

periods, the Germanic tribes had no written language. What we know about their early military history comes from accounts written in Latin

and from archaeology. This causes significant gaps in the historic timeline. Germanic wars

against the Romans

are fairly well documented from the Roman perspective; however, Germanic wars against the early Celts remain mysterious because neither side recorded the events. Wars between the Germanic tribes in Northern Belgium

and the present day Netherlands, and various Celtic tribes that bordered their lands, are likely due to their geographical proximity.

in northern Germany and southern Scandinavia

. The tribes spread south, possibly motivated by the deteriorating climate of that area. They crossed the River Elbe

, most likely overrunning territories formerly occupied by Celtic people. In the East, other tribes, such as Goths

, Rugians

and Vandals

, settled along the shores of the Baltic Sea

pushing southward and eventually settling as far away as Ukraine

. The Angles

and Saxons

migrated to England. The Germanic peoples often had unsettled relationships with their neighbours and each other, leading to a period of over two millennia of military conflict over various territorial, religious, ideological and economic issues.

, reported by Tacitus to have lived around the Rhine delta, in the area which is currently the Netherlands, "an uninhabited district on the extremity of the coast of Gaul, and also of a neighbouring island, surrounded by the ocean in front, and by the river Rhine in the rear and on either side" (Tacitus, Histories iv). This led to the Latin

name of Batavia for the area. The same name is used for several military units, originally raised among the Batavi.

They were mentioned by Julius Caesar

in his commentary Gallic Wars

, as living on an island formed by the Meuse River

after it is joined by the Waal, 80 Roman mile

s from the mouth of the river. He said there were many other islands formed by branches of the Rhine, inhabited by a "savage, barbarous nation", some of whom were supposed to live on fish and the eggs of sea-fowl.

Tacitus named the Mattiaci

as a similar tribe under homage, but on the other side of the Rhine. The areas inhabited by the Batavians were never occupied by the Romans

, as the Batavians were allies.

The Batavians incorrectly became regarded as the sole and eponymous ancestors of the Dutch

people. The Netherlands were briefly known as the Batavian Republic

. Moreover, during the time Indonesia

was a Dutch colony (the Dutch East Indies

), the capital (now Jakarta

) was named Batavia. If the ancestry of most native Dutch people were traced back to Germanic tribes, most would lead to the Franks

. Dutch

is in fact a Low Frankish language, and is the only language (together with Afrikaans

, which descends from Dutch itself) to be a direct descendant of Old Frankish

, the language of the Franks

.

Later, Tacitus described the Batavians as the bravest of the tribes of the area, hardened in the Germanic border wars, with cohorts under their own noble commanders transferred to Britannia

Later, Tacitus described the Batavians as the bravest of the tribes of the area, hardened in the Germanic border wars, with cohorts under their own noble commanders transferred to Britannia

. He said they retained the honour of the ancient association with the Romans, not required to pay tribute or taxes and used by the Romans only for war: "They furnished to the Empire nothing but men and arms", Tacitus remarked. Well regarded for their skills in horsemanship and swimming — for men and horses could cross the Rhine without losing formation, according to Tacitus. Dio Cassius

describes this surprise tactic employed by Aulus Plautius

against the "barbarians" — the British Celts — at the battle of the River Medway

, 43:

The Batavians also provided a contingent for the Emperor's Imperial Horse Guard

.

(notably at Castlecary

and Carrawburgh

), in Germany, Yugoslavia

, Hungary, Romania

and Austria. After the 3rd century, however, the Batavians are no longer mentioned, and they are assumed to have merged with the neighbouring Frisian

and Frankish

people.

Until the Franks

Until the Franks

defeated and pushed them back the Romans established two provinces in the area of the present-day Belgium and a part of the Netherlands. Both were outposts, especially above the Meuse

and apart from a few Roman legions sent there to protect the Empires borders, the Roman presence was limited. The provinces were called Gallia Belgica

named after the Belgae

, a group of Celtic tribes conquered by the Romans, and Germania Inferior

(inferior meaning 'low' in Latin

, and Germania referring to the area occupied by the Germanic tribes).

During the Batavian rebellion, which took place in the Roman province

of Germania Inferior

between 69 and 70 AD, the rebels led by Civilis

managed to destroy four legions

and inflict humiliating defeats on the Roman army. After their initial successes, a massive Roman army led by Quintus Petillius Cerialis

eventually defeated them. Following peace talks, the situation was normalized, but Batavia had to cope with humiliating conditions and a legion stationed permanently within her lands.

For more information see: The Batavian rebellion

. The confederation was formed out of Germanic tribes: Salians

, Sugambri, Chamavi

, Tencteri, Chattuarii

, Bructeri

, Usipetes, Ampsivarii

, Chatti

. They entered the late Roman Empire

from the present day Netherlands and northern Germany and conquered northern Gaul

where they were accepted as a foederati

and established a lasting realm

(sometimes referred to as Francia) in an area that covers most of modern-day France and the western regions of Germany (Franconia

, Rhineland

, Hesse

) and the whole of the Low Countries

, forming the historic kernel of the two modern countries. The conversion to Christianity

of the pagan Frankish king Clovis

was a crucial event in the history of Europe. Like the French and Germans, the Dutch also claim the military history of the Franks as their own.

Battle of Soissons

(486)

Battle of Tolbiac

(496)

Battle of Vouillé

(507)

Battle of Tours

(732)

Battle of Pavia

(773)

Saxon Campaigns

(773-804)

Siege of Paris

(885-886)

, from the 5th to the 10th centuries, from 481 ruled by Clovis I

of the Merovingian Dynasty

, the first king of all the Franks. From 751, under the Carolingian Dynasty, it is known as the Carolingian Empire

. After the Treaty of Verdun

of 843 it was split into East, West and Middle Francia

. East Francia gave rise to the Holy Roman Empire

with Otto I the Great in 962.

Since the term "Empire" properly applies only to times after the coronation of Charlemagne

in 800, and since the unified kingdom was repeatedly split and re-united, most historians prefer to use the term Frankish Kingdoms or Frankish Realm to refer to the entirety of Frankish rule from the 5th to the 9th century.

The Frankish realm underwent many partitions and repartitions, since the Franks divided their property among surviving sons, and lacking a broad sense of a res publica

The Frankish realm underwent many partitions and repartitions, since the Franks divided their property among surviving sons, and lacking a broad sense of a res publica

, they conceived of the realm as a large extent of private property

. This practice explains in part the difficulty of describing precisely the dates and physical boundaries of any of the Frankish kingdoms and who ruled the various sections. The contraction of literacy

while the Franks ruled compounds the problem: they produced few written records. In essence, however, two dynasties

of leaders succeeded each other; first the Merovingians and then the Carolingians.

The Holy Roman Empire was a political conglomeration of land

The Holy Roman Empire was a political conglomeration of land

s in Central Europe

and Western Europe

in the Middle Ages

and the early modern period. Emerging from the eastern part of the Frankish Empire

after its division in the Treaty of Verdun

(843), it lasted almost a millennium until its dissolution in 1806. By the 18th century, it still consisted of the larger part of modern Germany, Bohemia

(now Czech Republic

), Austria, Liechtenstein

, Slovenia

, Belgium, and Luxembourg

, as well as large parts of modern Poland and small parts of the Netherlands and Croatia

. Previously, it had included all of the Netherlands and Switzerland, parts of modern France and Italy. By the middle of the 18th century the Empire had been greatly reduced in power.

The Eighty Years' War, or Dutch Revolt, was the war of secession

The Eighty Years' War, or Dutch Revolt, was the war of secession

between the Netherlands and the Spanish king, that lasted from 1568 to 1648. The war resulted in the Seven United Provinces

being recognized as an independent state. The region now known as Belgium and Luxembourg

also became established as the Southern Netherlands

, part of the Seventeen Provinces

that remained under royal Habsburg

rule.

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, or the Dutch Republic, became a world power, through its merchant shipping and huge naval power, and experienced a period of economic, scientific and cultural growth. In the late 16th century military reform by Maurice of Orange laid the foundation for early modern battlefield tactics. The Dutch army between 1600 and 1648 was one of the most powerful in Europe, together with the English and French.

(Dutch: Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC), chartered in 1602, concentrated Dutch trade efforts under one directorate with a unified policy. In 1605 armed Dutch merchantmen captured the Portuguese

fort at Amboyna

in the Moluccas

, which was developed into the first secure base of the VOC. The Twelve Years' Truce

signed in Antwerp in 1609 called a halt to formal hostilities between Spain (which controlled Portugal and its territories at the time) and the United Provinces

. In the Indies, the foundation of Batavia formed the permanent center from which Dutch enterprises, more mercantile than colonial, could be coordinated. From it "the Dutch wove the immense web of traffic and exchange which would eventually make up their empire, a fragile and flexible one built, like the Portuguese empire, 'on the Phoenician model

'." (Braudel 1984, p. 215)

Over the next decades the Dutch captured the major trading ports of the East Indies: Malacca

in 1641; Achem (Aceh

) in the native kingdom of Sumatra

, 1667; Macassar

, 1669; and Bantam

itself, in 1682. At the same time connections in the ports of India provided the printed cotton

s that the Dutch traded for pepper

, the staple of the spice trade

.

The greatest source of wealth in the East Indies, Fernand Braudel

has noted, was the trade within the archipelago, what the Dutch called inlandse handel ('native trade'), where one commodity was exchanged for another, with profit at each turn, as silver

from the Americas was more desirable in the East than in Europe.

By concentrating on monopolies in the fine spices, Dutch policy encouraged monoculture

: Amboyna

for clove

s, Timor

for sandalwood

, the Bandas

for mace and nutmeg

, Ceylon for cinnamon

. Monoculture linked island economies to the mercantile system to provide the missing necessities of life.

The Dutch East India company's army was defeated by a Chinese Ming dynasty

army led by Koxinga

at the Siege of Fort Zeelandia

on Taiwan

. The Chinese used ships and naval bombardment with cannon to force a surrender. The expulsion of the Dutch ended their colonial rule over Taiwan.

The Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden/Provinciën; also Dutch Republic or United Provinces in short) was a European republic

The Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden/Provinciën; also Dutch Republic or United Provinces in short) was a European republic

between 1581 (but was formally recognised in 1648) and 1795, which is now known as the Netherlands. From an economic and military perspective, the Republic of the United Provinces was extremely successful. This time period is known in the Netherlands as the Golden Age

. The free trade spirit of the time received a strong augmentation through the development of a modern stock market

in the Low Countries. At first the Dutch had a very strong standing field army and large garrisons in their numerous fortified cities. From 1648 on however the Army was neglected; and for a few years even the Navy fell into neglect— until rivalry with England forced a large extension of naval forces.

The Anglo-Dutch Wars were fought in the 17th and 18th centuries between Britain

and the United Provinces for control over the seas and trade routes. They are known as the Dutch Wars in England and as the English Wars in the Netherlands.

against the Commonwealth of England

declared by the Rump Parliament

) was the Isles of Scilly

, off Cornwall. From these islands, governed by Sir John Grenville, and from other friendly ports, a section of the Royal Navy

that had mutinied to Charles' side operated in a piratical

way against shipping in the English channel.

The Dutch declared war against the Scillies as a legal fiction

which would cover a hostile response to the Royalist fleet. In July 1651, soon after the declaration of war, the Parliamentarian forces under Admiral Robert Blake

forced the Royalist fleet to surrender. The Netherlands fleet, no longer under threat, left without firing a shot. However, due to the obscurity of one nation's declaration of war against a small part of another, the Dutch forgot to officially declare peace.

In 1985, the historian

and Chairman of the Isles of Scilly Council Roy Duncan, wrote to the Dutch Embassy in London to dispose of the "myth" that the islands were still at war. But embassy staff found the myth to be accurate and Duncan invited Ambassador

Jonkheer

Rein Huydecoper to visit the islands and sign a peace treaty

. Peace was declared on April 17, 1986, a stunning 335 years after the war began.

in 1648 meant that the colonial possessions of the Portuguese

and Spanish Empire

s were effectively up for grabs. This brought the Commonwealth of England

and the United Provinces

of the Netherlands, former allies in the Thirty Years' War

, into conflict. The Dutch had the largest mercantile fleet of Europe, and a dominant position in European trade. They had annexed most of Portugal's territory in the East Indies

giving them control over the enormously profitable trade in spice

s. They were even gaining significant influence over England's maritime trade with her North American colonies

, profiting from the turmoil that resulted from the English Civil War

. However, the Dutch navy had been neglected during this time period, while Cromwell

had built a strong fleet.

In order to protect its position in North America and damage Dutch trade, in 1651 the Parliament

of the Commonwealth of England

passed the first of the Navigation Acts

, which mandated that all goods from her American colonies must be carried by English ships. In a period of growing mercantilism

this was the spark that ignited the first Anglo-Dutch war, the British seeking a pretext to start a war which led to sporadic naval engagements across the globe.

The English were initially successful, Admiral Robert Blake

defeating the Dutch Admiral Witte de With in the Battle of the Kentish Knock

in 1652. Believing that the war was all but over, the English divided their forces and in 1653 were routed by the fleet of Dutch Admiral Maarten Tromp

at the Battle of Dungeness

in the English Channel

. The Dutch were also victorious at the Battle of Leghorn

and had effective control of both the Mediterranean and the English Channel

. Blake, recovering from an injury, rethought, together with George Monck

, the whole system of naval tactics, and in mid 1653 used the Dutch line of battle

method to drive the Dutch navy back to its ports in the battles of Portland

and the Gabbard

. In the final Battle of Scheveningen

on August 10, 1653 Tromp was killed, a blow to Dutch morale, but the British were forced to end their blockade of the Dutch coast. As both nations were by now exhausted, peace negotiations were started.

The war ended on 1654-04-05 with the signing of the Treaty of Westminster

, but the commercial rivalry was not resolved, the British having failed to replace the Dutch as the world's dominant trade nation.

. When Charles X of Sweden had been unable to continue his hold on Poland — partly because the Dutch fleet relieved the besieged city of Danzig in 1656 — he turned his attention on Denmark, invading that country from what is now Germany. He broke a new agreement with Frederick III of Denmark

and laid siege to Copenhagen

. To the Dutch the Baltic trade was vital, both in quantity and quality. The Dutch had been able to convince Denmark, by threat of force, to keep the Sound

tolls at a low level but they feared a strong Swedish empire would not be so complying. In 1658 they sent an expedition fleet of 75 ships, 3,000 cannon and 15000 troops; in the Battle of the Sound

it defeated the Swedish

fleet and relieved Copenhagen. In 1659 the Dutch liberated the other Danish Isles and the essential supply of grain, wood and iron from the Baltic was guaranteed once more.

After the English Restoration

After the English Restoration

, Charles II

tried to serve his dynastic interests by attempting to make Prince William III of Orange

, his nephew, stadtholder

of The Republic, using military pressure. This led to a surge of patriotism in England, the country being, as Samuel Pepys

put it, "mad for war".

This war, deliberately provoked by the English in 1664, witnessed several significant English victories in battle, (but also some Dutch ones such as the capture of the HMS Prince Royal during the Four Days Battle

in 1666 which was the subject of a famous painting by Willem van de Velde). However, the Raid on the Medway

(entailing the burning of part of the English fleet whilst docked at Chatham in June 1667 when a flotilla of ships led by Admiral de Ruyter

broke through the defensive chains guarding the Medway

and wrought havoc on the English ships as well as the capture of the Royal Navy

's flagship

HMS Royal Charles

) saw the war ended with a Dutch victory. For several years the greatly expanded Dutch Navy

was the most powerful navy in the world. The Republic was at the zenith of its power.

Franco-Dutch War (1672–1678) was a war fought between France and a quadruple alliance

Franco-Dutch War (1672–1678) was a war fought between France and a quadruple alliance

consisting of Brandenburg

, the Holy Roman Empire

, Spain, and the United Provinces

. The war ended with the Treaty of Nijmegen (1678); this granted France control of the Franche-Comté

(from Spain).

France led a coalition including Münster

and Great Britain. Louis XIV

was annoyed by the Dutch refusal to cooperate in the destruction and division of the Spanish Netherlands. As the Dutch army had been neglected, the French had no trouble by-passing the fortress of Maastricht

and then marching to the heart of the Republic, taking Utrecht

. Prince William III of Orange

is assumed to have had the leading Dutch politician Johan de Witt

deposed and murdered, and was acclaimed stadtholder

. The French were halted by inundations, the Dutch Water Line, after Louis tarried too much in conquering the whole of the Republic. He had promised the major Dutch cities to the British and tried to extort huge sums from the Dutch in exchange for a separate peace. The bishop of Münster laid siege to Groningen

but failed. 1672 is known as the rampjaar

("disaster year") in Dutch history, in which the country only nearly survived the combined English-French-German assault.

Soon after the second Anglo-Dutch War, the English navy was rebuilt. After the embarrassing events in the previous war, English public opinion was unenthusiastic about starting a new one. Bound by the secret Treaty of Dover Charles II was however obliged to assist Louis XIV

in his attack on The Republic in the Franco-Dutch War

. This he did willingly, having manipulated the French and Dutch into war. The French army being halted by inundations, and an attempt was made to invade The Republic by sea. Admiral Michiel de Ruyter

, gaining four strategic victories against the Anglo-French fleet, prevented invasion. After these failures the English parliament forced Charles to sign a peace in 1674.

Already, allies had joined the Dutch — the Elector

of Brandenburg

, the Emperor

, and Charles II of Spain

. Louis, despite the successful Siege of Maastricht

in 1673, was forced to abandon his plans of conquering the Dutch and revert to a slow, cautious war of attrition around the French frontiers. By 1678, he had managed to break apart his opponents' coalition, and managed to gain considerable territories by the terms of the Treaty of Nijmegen. Most notably, the French acquired the Franche-Comté

and various territories in the Netherlands from the Spanish. Nevertheless the Dutch had thwarted the ambitions of two of the major royal dynasties of the time: the Stuarts and the Bourbons.

repulsed a French force attempting to recapture the island of Tobago

. Heavy losses were suffered on both sides: one of the Dutch supply ships caught fire and exploded. The fire then quickly spread in the narrow bay causing several ships, among them the French flagship 'Glorieux', to catch fire and explode in turn which resulted in great loss of life on both sides. The French under d'Estrees retreated.

from 1688 to 1697, between France and the League of Augsburg — which, by 1689, was known as the "Grand Alliance

". The war was fought to resist French expansionism along the Rhine, as well as, on the part of England, to safeguard the results of the Glorious Revolution

from a possible French-backed restoration of James II

. In North America the war was known as King William's War

.

, and various of the German princes (including the Palatinate, Bavaria

, and Brandenburg

) to resist French expansionism in Germany. The alliance was joined by Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Provinces

.

France had expected a benevolent neutrality on the part of James II's England, but after James's deposition and replacement by his son-in-law William of Orange

, Louis's inveterate enemy, England declared war on France in May 1689, and the League of Augsburg became known as the "Grand Alliance", with England, Portugal, Spain, the United Provinces, and most of the German states joined together to fight France.

in August 1689, in which the French were defeated by an allied army under Prince Georg Friedrich of Waldeck, the French under Marshal Luxembourg were successful at the Battle of Fleurus

in 1690, but Louis prevented Luxembourg from following up on his victory. The French were also successful in the Alps in 1690, with Marshal Catinat defeating the Duke of Savoy at the Battle of Staffarda

and occupying Savoy. The Turkish recapture of Belgrade

in October of the same year proved a boon to the French, preventing the Emperor from making peace with the Turks and sending his full forces west. The French were also successful at sea, defeating the Anglo-Dutch fleet at Beachy Head

, but failed to follow up on the victory by sending aid to the Jacobite forces in Ireland or pursuing control of the Channel.

The French followed up on their success in 1691 with Luxembourg's capture of Mons

and Halle

and his defeat of Waldeck at the Battle of Leuze

, while Marshal Catinat continued his advance into Italy, and another French army advanced into Catalonia, and in 1692 Namur

was captured by a French army under the direct command of the King, and the French beat back an allied offensive under William of Orange at the Battle of Steenkerque

.

was still suffering from the disorders of the reign of King Charles II

, which had been only in part corrected during the short reign of James II. The first squadrons were sent out late and in insufficient strength. The Dutch, crushed by the obligation to maintain a great army, found an increasing difficulty in preparing their fleet for action early. Louis XIV, with as yet inexhausted resources, had it within his power to strike first.

, and gained a success over the combined British and Dutch fleets on July 10, 1690 in the Battle of Beachy Head

, which was not followed up by vigorous action. During the following year, while James's cause was finally ruined in Ireland, the main French fleet was cruising in the Bay of Biscay

, principally for the purpose of avoiding battle. During the whole of 1689, 1690 and 1691, British squadrons were active on the Irish coast -helping to win the Williamite war in Ireland

for the allies. One raised the siege of Derry

in July 1689, and another convoyed the first British and Dutch forces sent over under the Duke of Schomberg

. Immediately after Beachy Head in 1690, a part of the Channel fleet carried out an expedition under the Earl of Marlborough

, which took Cork

and reduced a large part of the south of the island. William of Orange himself arrived in Ireland in 1690 with veteran Dutch and allied troops, defeating the James II

at the battle of the Boyne

-an engagement largely decided by Dutch infantry. The war was ended in Anglo-Dutch favour in 1691, when Dutch general Ginkel destroyed the Franco-Irish army at the Battle of Aughrim

.

In 1691, the French did little more than help to carry away the wreckage of their allies and their own detachments. In 1692 a vigorous but tardy attempt was made to employ their fleet to cover an invasion of England at the Battle of La Hougue. It ended in defeat, and the allies remained masters of the Channel. The defeat of La Hougue did not do so much harm to Louis's naval power, and in the next year, 1693, he was able to strike a severe blow at the Allies.

In this instance, the arrangements of the allied governments and admirals were not good. They made no effort to blockade Brest, nor did they take effective steps to discover whether or not the French fleet had left the port. The convoy was seen beyond the Scilly Isles

by the main fleet. But as the French admiral Tourville

had left Brest for the Straits of Gibraltar with a powerful force and had been joined by a squadron from Toulon

, the whole convoy was scattered or taken by him, in the latter days of June, near Lagos Bay

. Although this success was a very fair equivalent for the defeat at La Hogue, it was the last serious effort made by the navy of Louis XIV in this war. Want of money compelled him to lay his fleet up.

The allies were now free to make full use of their own, to harass the French coast, to intercept French commerce, and to cooperate with the armies acting against France. Some of the operations undertaken by them were more remarkable for the violence of the effort than for the magnitude of the results. The numerous bombardments of French Channel ports, and the attempts to destroy St Malo, the great nursery of the active French privateer

s, by infernal machines, did little harm. A British attack on Brest in June 1694 was beaten off with heavy loss, the scheme having been betrayed by Jacobite

correspondents. Yet the inability of the French king to avert these enterprises showed the weakness of his navy and the limitations of his power. The protection of British and Dutch commerce was never complete, for the French privateers were active to the end, but French commerce was wholly ruined.

of 1688 was the last successful invasion of England and ended the conflict by placing Prince William III of Orange

on the English throne as co-ruler with his wife Mary

. Though this was in fact a military conflict between Great Britain and The Republic, William invading the British Isles with a Dutch fleet and army, in English histories it is never described as such because he had strong support in England and was partly serving the dynastic interests of his wife.

The regime change

was a major contributing factor in the economic decline of the Dutch Republic. The Dutch merchant elite immediately began to use London as a new operational base. Dutch economic growth slowed. William ordered that any Anglo-Dutch fleet be under British command, with the Dutch navy having 60% of the strength of the British. From about 1720 Dutch wealth declined. Between 1740 and 1770 the Dutch Navy was neglected. Around 1780 the per capita gross national product of the Kingdom of Great Britain

surpassed that of the Dutch Republic.

The Dutch Republic, nominally neutral, had been trading with the Americans during the American Revolutionary War

, exchanging Dutch arms and munitions for American colonial wares (in contravention of the British Navigation Acts

), primarily through activity based in St. Eustatius, before the French formally entered the war. The British considered this trade to include contraband military supplies and had attempted to stop it, at first diplomatically by appealing to previous treaty obligations, interpretation of whose terms the two nations disagreed on, and then by searching and seizing Dutch merchant ships. The situation escalated when the British seized a Dutch merchant convoy sailing under Dutch naval escort

in December 1779, prompting the Dutch to join the League of Armed Neutrality

. Britain responded to this decision by declaring war on the Dutch in December 1780, sparking the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War

.

The Dutch navy was by now only a shadow of its former self, having only about twenty ships of the line, so there were no large fleet battles. The English tried to reduce the Republic to the status of a British protectorate

, using Prussia

n military pressure and gaining factual control over most of the Dutch colonies, those conquered during the war given back at war's end. The Dutch then still held some key positions in the European trade with Asia, such as the Cape, Ceylon and Malacca

. The war sparked a new round of Dutch ship building (95 warships in the last quarter of the 18th century), but the British kept their absolute numerical superiority by doubling their fleet in the same time.

Against this background it is less surprising that, after the French Revolution

, when Napoleon invaded and occupied the Netherlands in 1795, the French encountered so little united resistance. William V of Orange fled to England. The Patriots proclaimed the short-lived Batavian Republic

, but government was soon returned to stabler and more experienced hands. In 1806 Napoleon restyled the Netherlands (along with a small part of what is now Germany) into the Kingdom of Holland

, with his brother Louis (Lodewijk) Bonaparte as king. This too was short-lived, however. Napoleon incorporated the Netherlands into the French empire

after his brother put Dutch interests ahead of those of the French. The French occupation of the Netherlands ended in 1813 after Napoleon was defeated, a defeat in which William V of Orange played a prominent role.

) designated the Netherlands as a republic

modeled after the French Republic, to which it was a vassal state

.

The Batavian Republic was proclaimed on January 19, 1795, a day after stadtholder

William V of Orange fled to England. The invading French revolutionary army

, however, found quite a few allies in Holland. Eight years before, the Orange faction had won the upper hand in a small, but nasty civil war only thanks to the military intervention of the King of Prussia

, brother-in-law of the stadtholder.

Many of the revolutionaries (see: Patriots (faction)

) had fled to France and now returned eager to realize their ideals.

In contrast to events in France, revolutionary changes in the Netherlands occurred comparatively peacefully. The country had been a republic

for two centuries and had a limited nobility. The guillotine

proved unnecessary to the new state. The old Republic had been a very archaic and ineffective political construction, still largely based on old feudal

institutions. Decision-making had proceeded very slowly and sometimes did not happen at all. The individual provinces had possessed so much power that they blocked many sensible innovations. The Batavian Republic marked the transition to a more centralised and functional government, from a loose confederation

of (at least nominally) independent provinces to a true unitary state

. Many of its innovations were retained in later times, such as the first official spelling standard of the Dutch language

by Siegenbeek (1804). Jews, Lutherans and Roman Catholics were given equal rights

. A Bill of Rights

was drafted.

The new Republic took its name from the Batavi, a Germanic tribe who had lived in the area of the Netherlands in Roman

times and who were then romantically regarded as the ancestors of the Dutch nation.

Again in contrast to France, the new Republic did not experience a reign of terror or become a dictatorship. Changes were imposed from outside after Napoleon Bonaparte's rise to power. In 1805 Napoleon installed the shrewd politician Schimmelpenninck

as raadspensionaris ("Grand Pensionary

", i.e. president of the republic) to strengthen the executive branch. In 1806 Napoleon forced Schimmelpenninck to resign and declared his brother Louis Bonaparte

king

of the new Kingdom of Holland

.

The only signs of political instability were three coups d'état

. The first occurred in 1798, when the unitarian democrats were annoyed by the slow pace of democratic reforms. A few months later a second coup put an end to the dictatorship of the unitarians. The National Assembly, which had been convened in 1796, was divided by a struggle among the factions. The third coup occurred in 1801, when a French commander, backed by Napoleon, staged a conservative coup reversing the changes made after the 1798 coup. The Batavian government was more popular among the Dutch population than was the prince of Orange. This was apparent during the British-Russian invasion of 1799.

As a French vassal state, the Batavian Republic was an ally of France in its wars against Great Britain. This led to the loss of most of the Dutch colonial empire and a defeat of the Dutch fleet in the Battle of Camperdown

(Camperduin) in 1797. The collapse of Dutch trade caused a series of economic crises. Only in the second half of the 19th century would Dutch wealth be restored to its previous level.

continued from 1794 between France and the First coalition

.

The year opened with French forces in the process of attacking Holland in the middle of winter. The Dutch people were rather indifferent to the French call for revolution, as they had already been a republic for two centuries, nevertheless city after city was occupied by the French. The Dutch fleet was captured, and the stadtholder

fled to be replaced by the Batavian Republic

, and, as a vassal state of France, supported the French cause and signed the treaty of Paris, ceding the territories of Brabant

and Maastricht

to France on May 16.

With the Netherlands falling, Prussia

also decided to leave the coalition, signing the Peace of Basle on April 6, ceding the left bank of the Rhine to France. This freed Prussia to finish the occupation of Poland.

, Royaume de Hollande in French

) was set up by Napoleon Bonaparte

as a puppet kingdom

for his third brother, Louis Bonaparte

, in order to better control the Netherlands. The name of the leading province

, Holland, was now taken for the whole country. Louis did not perform to Napoleon's expectations - he tried to serve Dutch interests instead of his brother's - and the kingdom was dissolved in 1810 after which the Netherlands were annexed

by France until 1813 when the French were defeated.

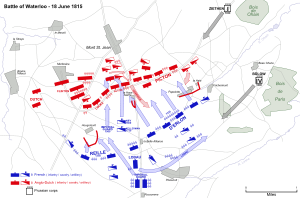

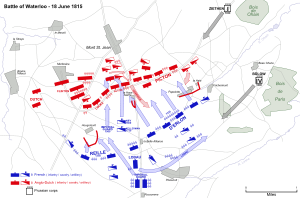

, Brunswick, and the Netherlands

and Nassau were about 67,000 men strong. (Of the 26 infantry brigade

s in Wellington's army, nine were British; of the 12 cavalry brigades, 7 were British. Half the 29 batteries

of guns were Hanoverian or Dutch).

At Waterloo, Wellington had the reinforced Hougomont farm, anchoring his right flank, and several other farms on his left. Napoleon faced his first major problem even before the battle began. Unsure of the Prussian Army's position since its flight from Ligny two days previously, Napoleon was all too aware of the need to begin the assault on Wellington's positions. The battle commenced at about 10:00 with an attack upon Hougoumont, but the main attack, with the most feared weapon of the era, the French field artillery

, was delayed for hours until the sodden ground from the previous night's downpour had dried out sufficiently to take the weight of the French ordnance. The mud also hindered infantry and cavalry as they trudged into position. When the French artillery eventually opened fire on Wellington's ridge at around 11:35, the expected impact on the Allied troops was diminished by the soft terrain that absorbed the impact of many of the cannon balls.

A crucial element of the French plan of battle was the expectation that Wellington would move his reserve to his right flank in defense of Hougomont. At one point, the French succeeded in breaking into the farm's courtyard before being repulsed, but their attacks on the farm were eventually unsuccessful, and Wellington did not need to use his reserve. Hougomont became a battle within a battle and, throughout that day, its defence continued to draw thousands of valuable French troops, under the command of Jérôme Bonaparte, into a fruitless attack while all but a few of Wellington's reserves remained in his centre.

At about 13:30, after receiving news of the Prussian advance to his right, Napoleon ordered Marshal Ney to send d'Erlon's infantry forward against the allied flank near La Haye Sainte

At about 13:30, after receiving news of the Prussian advance to his right, Napoleon ordered Marshal Ney to send d'Erlon's infantry forward against the allied flank near La Haye Sainte

. The attack centred on the Dutch 1st Brigade commanded by Major-General Willem Frederik van Bylandt

, which was one of the few units placed on the forward slope of the ridge. After suffering an intense artillery bombardment and exchanging volleys with d'Erlon's leading elements for some nine minutes, van Bylandt's outnumbered soldiers were forced to retreat over the ridge and through the lines of General Thomas Picton

's division. Picton's division moved forward over the ridgeline to engage d'Erlon. The British and Dutchmen were likewise mauled by volley-fire and close-quarter attacks, but Picton's soldiers stood firm, eventually breaking up the attack by charging the French columns.

Meanwhile, the Prussians began to appear on the field. Napoleon sent his reserve, Lobau's VI corps and 2 cavalry divisions, some 15,000 troops, to hold them back. With this, Napoleon had committed all of his infantry reserves, except the Guard.

Lacking an infantry reserve, as Napoleon was unwilling to commit the Guard at this stage of the battle, all that Ney could do was to try to break Wellington's centre with his cavalry. It struggled up the slope to the fore of Wellington's centre, where squares of Allied infantry awaited them.

The cavalry attacks were repeatedly repelled by the solid Allied infantry squares (four ranks deep with fixed bayonets - vulnerable to artillery or infantry, but deadly to cavalry), the harrying fire of British artillery as the French cavalry recoiled down the slopes to regroup, and the decisive counter-charges of the Allied Light Cavalry regiments and the Dutch Heavy Cavalry Brigade. After numerous fruitless attacks on the Allied ridge, the French cavalry was exhausted.

The Prussians were already engaging the Imperial Army's right flank when La Haye Sainte

fell to French combined arms (infantry, artillery and cavalry), because the defending King's German Legion

had run out of ammunition in the early evening. The Prussians had driven Lobau out of Plancenoit, which was on the extreme (Allied) left of the battle field. Therefore Napoleon sent his 10 battalion strong Young Guard to beat the Prussians back. But after very hard fighting the Young Guard was beaten back. Napoleon sent 2 battalions of Old Guard and after ferocious fighting they beat the Prussians out. But the Prussians had not been forced away far enough. Approximately 30,000 Prussians attacked Plancenoit again. The place was defended by 20,000 Frenchmen in and around the village. The Old Guard and other supporting troops were able to hold on for about one hour before a massive Prussian counter-attack kicked them out after some bloody street fighting lasting more than a half hour. The last to flee was the Old Guard who defended the church and cemetery. The French casualties at the end of the day were horrible.

With Wellington's centre exposed by the French taking La Haye Sainte

, Napoleon committed his last reserve, the undefeated Imperial Guard. After marching through a blizzard of shell and shrapnel, the already outnumbered 5 battalions of middle guard defeated the allied first line, including British, Brunswick and Nassau troops.

Meanwhile, to the west, 1,500 British Guards under Maitland

were lying down to protect themselves from the French artillery. They rose as one, and devastated the shocked Imperial Guard with volleys of fire at point-blank range. The French chasseurs deployed to answer the fire. After 10 minutes of exchanging musketry the outnumbered French began wavering. This was the sign for a bayonet charge. But then a fresh French chasseur battalion appeared on the scene. The British guard retired with the French in pursuit - though the French in their turn were attacked by fresh British troops of Adam's brigade.

The Imperial Guard fell back in disarray and chaos. A ripple of panic passed through the French lines - "La garde recule. Sauve qui peut!" ("The Guard retreats. Save yourself if you can!"). Wellington, judging that the retreat by the Imperial Guard had unnerved all the French soldiers who saw it, stood up in the stirrups of Copenhagen (his favourite horse), and waved his hat in the air, signalling a general advance. The long-suffering Anglo-Dutch infantry rushed forward from the lines where they had been shelled all day, and threw themselves upon the retreating French.

.

The governor-general of the Dutch East Indies

, Herman Willem Daendels

(1762–1818), fortified the island of Java against possible British attack. In 1810 a strong British East India Company

expedition under Gilbert Elliot, first earl of Minto, governor-general of India, conquered the French islands of Bourbon (Réunion

) and Mauritius

in the Indian Ocean

and the Dutch East Indian possessions of Ambon

and the Molucca Islands. Afterward it moved against Java, captured the port city of Batavia (Jakarta

) in August 1811, and forced the Dutch to surrender at Semarang

on September 17, 1811. Java, Palembang

(in Sumatra

), Macassar

(Makasar, Celebes

), and Timor

were ceded to the British. Appointed lieutenant governor of Java, Thomas Stamford Raffles (1781–1826) ended Dutch administrative methods, liberalized the system of land tenure, and extended trade. In 1816, the British returned Java and other East Indian possessions to the Dutch as part of the accord ending the Napoleonic Wars

.

troops from 1821 to 1837 in West Sumatra

, Indonesia

.

In the 1820s, the Dutch were yet to consolidate their possessions in some parts of the Dutch East Indies (later Indonesia) after re-acquiring it from the British. At the same time, a conflict broke out in West Sumatra between the so called adat and padri factions. Although both Minangkabaus and Muslims, they differ in values: the Adats were Minangkabau traditionalists while the Padris were Islamist-reformists. The Padris sought to reform un-Islamic traditions, such as cockfighting and gambling.

led by the illustrious Prince Diponegoro

. The trigger was the Dutch decision to build a road across a piece of his property that contained his own parent's tomb. Among its causes was a sense of betrayal by the Dutch felt by members of the Javanese aristocratic families, as they were no longer able to rent land at high prices. There were also some problems with the succession of the throne in Yogyakarta: Diponegoro was the oldest son, but as his mother was not the queen, he did not have any right to succeed his father.

The troops of Prince Diponegoro were very successful in the beginning, controlling the middle of Java and besieging Yogyakarta. Furthermore the Javenese population was supportive of Prince Diponegoro's cause, whereas the Dutch colonial authorities were initially very indecisive.

However, as the Java war prolonged, Prince Diponegoro had difficulties in maintaining the numbers of his troops.

The Dutch colonial army however was able to fill its ranks with troops from Sulawesi

and later on with troops from the Netherlands. The Dutch commander, general De Cock, was able to end the siege of Yogyakarta on September 25, 1825.

Prince Diponegoro started a fierce guerilla war and it was not until 1827 that the Dutch army gained the upper hand.

It is estimated that 200,000 died over the course of the conflict, 8,000 being Dutch. The rebellion finally ended in 1830, after Prince Diponegoro was tricked into entering Dutch custody near Magelang

, believing he was there for negotiations for a possible cease-fire, and exiled to Manado

on the island of Sulawesi

.

that began with a riot in Brussels

in August 1830 and eventually led to the establishment of an independent, Catholic and neutral Belgium (William I

, king of the Netherlands, would refuse to recognize a Belgian state until 1839, when he had to yield under pressure by the Treaty of London

).

and Leuven

. Only the appearance of a French army under Marshal Gérard

caused the Dutch to retreat. The victorious initial campaign gave the Dutch an advantageous position in subsequent negotiations. William stubbornly pursued the war, bungled, ineffectual and expensive as its desultory campaigns were, until 1839.

on Aceh on March 26, 1873; the apparent immediate trigger for their invasion was discussions between representatives of Aceh and the United States in Singapore

during early 1873. An expedition under Major General Köhler was sent out in 1874, which was able to occupy most of the coastal areas. It was the intention of the Dutch to attack and take the Sultan's palace, which would also lead to the occupation of the entire country. The Sultan requested and possibly received military aid from Italy and the United Kingdom in Singapore: in any case the Aceh army was rapidly modernized, and Aceh soldiers managed to kill Köhler (a monument of this achievement has been built inside Grand Mosque of Banda Aceh). Köhler made some grave tactical errors and the reputation of the Dutch was severely harmed.

A second expedition led by General Van Swieten managed to capture the kraton (sultan's palace

): the Sultan had however been warned, and had escaped capture. Intermittent guerrilla warfare continued in the region for ten years, with many victims on both sides. Around 1880 the Dutch strategy changed, and rather than continuing the war, they now concentrated on defending areas they already controlled, which were mostly limited to the capital city (modern Banda Aceh

), and the harbour town of Ulee Lheue. On October 13, 1880 the colonial government declared the war as over, but continued spending heavily to maintain control over the areas it occupied.

War began again in 1883, when the British ship Nisero was stranded in Aceh, in an area where the Dutch had little influence. A local leader asked for ransom

from both the Dutch and the British, and under British pressure the Dutch were forced to attempt to liberate the sailors. After a failed Dutch attempt to rescue the hostage

s, where the local leader Teuku Umar

was asked for help but he refused, the Dutch together with the British invaded the territory. The Sultan gave up the hostages, and received a large amount in cash in exchange.

The Dutch Minister of Warfare Weitzel now again declared open war on Aceh, and warfare continued, with little success, as before. The Dutch now also tried to enlist local leaders: the aforementioned Umar was bought with cash, opium

, and weapons. Umar received the title panglima prang besar (upper warlord

of the government).

Umar called himself rather Teuku Djohan Pahlawan (Johan the heroic). On January 1, 1894 Umar even received Dutch aid to build an army. However, two years later Umar attacked the Dutch with his new army, rather than aiding the Dutch in subjugating inner Aceh. This is recorded in Dutch history as "Het verraad van Teukoe Oemar" (the treason

Umar called himself rather Teuku Djohan Pahlawan (Johan the heroic). On January 1, 1894 Umar even received Dutch aid to build an army. However, two years later Umar attacked the Dutch with his new army, rather than aiding the Dutch in subjugating inner Aceh. This is recorded in Dutch history as "Het verraad van Teukoe Oemar" (the treason

of Teuku Umar).

In 1892 and 1893, Aceh remained independent, despite the Dutch efforts. Major J.B. van Heutsz, a colonial military leader, then wrote a series of articles on Aceh. He was supported by Dr Snouck Hurgronje of the University of Leiden, then the leading Dutch expert on Islam. Hurgronje managed to get the confidence of many Aceh leaders and gathered valuable intelligence

for the Dutch government. His works remained an official secret for many years. In Hurgronje's analysis of Acehnese society, he minimised the role of the Sultan and argued that attention should be paid to the hereditary chiefs, the Ulee Balang, who he felt could be trusted as local administrators. However, he argued, Aceh's religious leaders, the ulema

, could not be trusted or persuaded to cooperate, and must be destroyed.

This advice was followed: in 1898 Van Heutsz was proclaimed governor

of Aceh, and with his lieutenant, later Dutch Prime Minister

Hendrikus Colijn

, would finally conquer most of Aceh. They followed Hurgronje's suggestions, finding cooperative uleebelang that would support them in the countryside. Van Heutsz charged Colonel Van Daalen with breaking remaining resistance. Van Daalen destroyed several villages, killing at least 2,900 Acehnese, among which were 1,150 women and children. Dutch losses numbered just 26, and Van Daalen was replaced by Colonel Swart. By 1904 most of Aceh was under Dutch control, and had an indigenous government that cooperated with the colonial state. Estimated total casualties on the Aceh side range from 50,000 to 100,000 dead, and over a million wounded.

were more prepared for the previous than the present war, for the Dutch not even that was true. Of all the major participants they were by far the most poorly equipped, not even attaining World War I standards. However, the German invaders in May 1940 adjusted their forces accordingly, and the Dutch army in the Battle of the Netherlands

was largely intact when it surrendered on May 14 — after just five days of fighting — to save the major Dutch cities from further bombardment.

The Dutch empire continued the fight, but the Netherlands East Indies (later Indonesia) was invaded by Japan in 1942. In the climactic Battle of the Java Sea

, the larger part of the Dutch navy was destroyed. The Dutch contribution to the war effort was then limited to the merchant fleet (providing the bulk of allied merchant shipping in the Pacific war), several aircraft squadrons, some naval vessels and a motorised infantry brigade raised by enlisting Dutch emigrants.

. As a result the home forces were much neglected and had to rearm by begging for (or simply taking) surplus allied equipment, as the RAM tank

. In 1949 Bernard Montgomery judged the Royal Netherlands Army

as simply "unfit for battle".

In the early fifties however, the Dutch fully participated in the NATO build-up of conventional forces. US financial support paying half of the equipment budget made it possible to create a modern defence force. Afraid that the USA might give up Europe immediately after a Soviet attack, the Dutch strongly reinforced the Rhine position by means of the traditional Dutch defensive weapon: water. Preparations were made to completely dam the major Rhine effluent

rivers, forcing the water into the northern IJssel

branch and thereby creating an impassable mudbarrier between Lake IJssel

and the Ruhr Area

. The Dutch navy was also expanded with an aircraft carrier

, two cruisers, twelve destroyers and eight submarines.

In the sixties, the Navy again began to produce modern vessels of its own design and expanded slowly, however nuclear propulsion was refused by the USA. The Army replaced most of its motorised units by mechanised ones, introducing thousands of AFV

s into the Infantry and the Artillery. Conventional firepower was neglected however as it was intended to engage in nuclear war immediately.

In the seventies, it was hoped that the strategy of flexible response

would allow for a purely conventional defence. Digital modelling by the Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research

showed that successful conventional defence was feasible and indeed likely, provided that conventional firepower would be improved. Whereas the British, French, Belgians and Canadians reduced their forces in this decade, the Dutch government therefore decided to go along with the German and American policy of force enlargement. As a result in the mid-eighties the Dutch heavy units equalled the British in number and the Dutch Corps sector at the Elbe

was the only one to have its own reserve division; it was conceived as to be able to hold an attack by nine reinforced Soviet divisions, or about 10,000 AFVs including materiel reserves. These facts were obscured somewhat by international press attention to the relaxation of discipline, part of a deliberate policy to better integrate the forces into the larger society. At the same time the Navy had over thirty capital vessels and the Air Force about 200 tactical planes.

When the Warsaw Pact

and the Soviet Union itself collapsed, the Dutch reduced their forces considerably and integrated their army with the German; but also created a new airborne brigade, replaced the conscript army by a fully professional one and bought hundreds of light AFVs for use in peace missions. Modernising of naval and air forces, less drastically reduced, continues.

recognized the opportunity presenting itself and declared independence from Dutch colonial rule. With the assistance of indigenous army units created by the Japanese, an independent Republic of Indonesia with Sukarno as its president was proclaimed on August 17, 1945.

The Netherlands, only very recently freed from German occupation itself, initially lacked the means to respond, allowing Republican forces to establish de facto

control over parts of the huge archipelago, particularly in Java and Sumatra

. On the other, in the less densely populated outer islands, no effective control was established by either party, leading at times to chaotic conditions.

, was killed as he pushed for an ultimatum stipulating that the Indonesians surrender their weapons or face a major assault. In retaliation, 10 November 1945, Surabaya was attacked by British forces, leading to a bloody street-to-street battle.

Lasting three weeks, the battle of Surabaya

was the bloodiest single engagement in the war and demonstrated the determination of the Indonesian nationalist forces. It made the British reluctant to be drawn into another when their resources in southeast Asia were stretched following the Japanese surrender.

, in which the 'United States of Indonesia' were proclaimed, a semi-autonomous federal state keeping as its head the Queen of the Netherlands.

Both sides increasingly accused each other of violating the agreement, and as consequence the hawkish forces soon won out on both sides. A major point of concern for the Dutch side was the fate of members of the Dutch minority in Indonesia, most of whom had been held under deplorable conditions in concentration camps by the Japanese. The Indonesians were accused (and guilty) of not cooperating in liberating these prisoners.

' to downplay the extent of the operations. There were atrocities and violations of human rights

in many forms by both sides in the conflict. Some 6,000 Dutch and 150,000 Indonesians are estimated to have been killed.

Although the Dutch and their indigenous allies managed to defeat the Republican Army in almost all major engagements and during the second campaign even to arrest Sukarno himself, Indonesian forces continued to wage a major guerrilla war under the leadership of General Sudirman who had escaped the Dutch onslaught.

A few months before the second Dutch offensive, communist elements within the independence movement had staged a failed coup, known as Madiun Affair

, with the goal of seizing control of the republican forces.

funds, which were vital to the Dutch rebuild after the Second World War, the Netherlands government was forced back into negotiations, and after the Round Table conference in The Hague, the Dutch finally recognised Indonesian independence on December 27, 1949. An exception was made for Netherlands New Guinea

(currently known as West Irian Jaya), which remained under Dutch control. In 1962, in an attempt to increase pressure on the Dutch, Indonesia launched a campaign of infiltration by commandos coming in by sea and air, which were all beaten back by the Dutch forces, although these were not serious invasions. After large pressure from mainly the United States (again about the Marshall Plan) the Dutch finally gave custody over New Guinea to the UN, which in 1963 gave New Guinea to Indonesia.

In the following decades, a diplomatic row between the governments of Indonesia and the Netherlands persisted over the officially recognized date of Indonesian independence. Indonesians commemorate the anniversary of Sukarno's proclamation (August 17, 1945) as their official holiday.

The Netherlands, having taken in a number of loyalist exiles who (for various reasons) viewed Sukarno's government as illegitimate, would only recognize the date of the final Dutch capitulation to Indonesia on December 27, 1949. This changed in 2005 when the Dutch Foreign Minister

, Bernard Bot, made several well-publicized goodwill gestures: officially accepting Indonesian independence as beginning on August 17, 1945; expressing regret for suffering caused by the fighting during the war; and attending the 60th anniversary commemoration of Sukarno's independence proclamation, part of the first Dutch delegation to do so.

and South Korea

. When it began, North and South Korea existed as provisional governments competing for control over the Korean peninsula, due to the division of Korea

. The war was one of the first major armed clashes of the Cold War

. The principal combatants were North Korea, supported by the People's Republic of China

, and later combat advisors, aircraft pilots, and weapons from the Soviet Union; against South Korea, supported principally by the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, the Philippines

and many other nations sent troops under the aegis of the United Nations

(UN), including the Netherlands, who sent over 3,000 troops.

The Netherlands Detachment United Nations was established on October 15, 1950 and out of a total number of 16,225 volunteers, 3,418 men were accepted and sent to Korea. Most Netherlands army troops were assigned to the "Netherlands Battalion", attached to the 38th Infantry Regiment

of the U.S. 2nd Infantry Division. Dutch casualties included 116 men killed in action, 3 missing in action and 1 who died as a prisoner of war.

Several vessels of the Royal Netherlands Navy

were deployed to Korean waters including the destroyers Evertsen, Van Galen and Piet Hein

and the frigates Johan Maurits van Nassau, Dubois

and van Zijll (not all at the same time). Their duties included patrolling Korean waters, escorting other ships and supporting ground troops with naval artillery

fire.

The war in Bosnia and Herzegovina

The war in Bosnia and Herzegovina

was an armed conflict that took place between March 1992 and November 1995. The war involved several ethnically defined factions within Bosnia and Herzegovina, each of which claimed to represent one of the country's constitutive peoples.

The United Nations Protection Force

(UNPROFOR) was the primary UN peacekeeping force in Croatia

and in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Yugoslav wars

. They served between February 1992 and March 1995. The Dutch Army contribution was known as ‘Dutchbat’. UNPROFOR was replaced by a NATO-led multinational force, IFOR

in December 1995.

The Royal Netherlands Air Force

deployed 12 F-16s as part of Operation Deny Flight

, NATO's enforcement of the Bosnian no-fly zone between April 1993 and December 1995 http://www.afsouth.nato.int/operations/denyflight/DenyFlightFactSheet.htm. The Royal Netherlands Air Force also deployed 18 F-16s as part of Operation Deliberate Force, a NATO air campaign conducted to undermine the military capability of Bosnian Serbs who threatened or attacked UN-designated "safe areas" in Bosnia http://www.afsouth.nato.int/factsheets/DeliberateForceFactSheet.htm.

One of the most controversial chapters of the Bosnian war and the Netherlands's involvement in the conflict was the Srebrenica massacre

that took place in July 1995, where at least 7,000 Muslim men and boys were murdered after the town of Srebrenica fell to Bosnian Serb forces.

Srebrenica was supposed to be a UN-designated safe area, and Dutch troops under the command of Colonel Thom Karremans

were tasked to protect Srebrenica's safe haven status. From the outset, both parties to the conflict violated the 'safe area' agreement. Dutchbat troops had arrived in January 1995 and watched the situation deteriorate rapidly in the months after their arrival. The already meagre resources of the civilian population dwindled further and even the UN forces started running dangerously low on food, medicine, fuel and ammunition. Eventually, the UN peacekeepers had so little fuel that they were forced to start patrolling the enclave on foot; Dutchbat soldiers who went out of the area on leave were not allowed to return and their number dropped from 600 to 400 men. With only machinegun-equipped, light armor (Dutch parliament refused to deploy tanks), UNHQ's refusal to commit air support when it was needed, a passive, politically motivated Dutch high command and malfunctioning US supplied anti tank weapons (they would kill the operator on launch), the Dutchbat soldiers present could only wait and watch. Bosnian Serb forces soon took over the town and the massacre soon followed. One Dutch soldier was killed by a grenade lobbed from a column of a retreating Bosniak soldiers; he was the only fatal Dutch casaulty in Srebrenica.

Thom Karremans, the UN, the Netherlands army and the Dutch government soon came under fierce criticism for their handling of the crisis. In 2002, a report by the Nederlands Instituut voor Oorlogsdocumentatie

concluded that the "humanitarian motivation and political ambitions drove the Netherlands to undertake an ill-conceived and virtually impossible peace mission" and that Dutchbat was ill-equipped to carry out such a mission. The report led to the resignation of the Second cabinet of Wim Kok

. The report did not satisfy those that believed the Netherlands bore greater responsibility in not preventing the massacre. http://www.un.org/News/ossg/srebrenica.pdf http://www.iwpr.net/?p=tri&s=f&o=165055&apc_state=henitri2004 http://service.spiegel.de/cache/international/spiegel/0,1518,327526,00.html http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/1923884.stm

and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation between March 24 and June 10, 1999 as a result of the breakdown of security and deteriorating human rights situation in Kosovo

. The Netherlands contributed several ships and aircraft to the NATO force in the region. On March 26, 1999, a Yugoslav MiG-29 was shot down by a Royal Netherlands Air Force F-16. At its height in 1999, the Netherlands provided 2,000 troops for KFOR, that entered Kosovo to establish and maintain a secure environment.

. The ‘War on Terrorism’ (in its current context) is the name given by the George W. Bush administration

to the efforts launched in response to the September 11, 2001 attacks

on New York

and Washington, D.C. by al-Qaeda

.

, also known as the 'Coalition' or 'US-led coalition', refers to the nations whose governments have military personnel in Iraq. The first Balkenende cabinet

supported the USA and the UK in the 2003 invasion of Iraq

. An independent contingent of 1,345 troops (including 650 Dutch Marines

, CH-47 Chinook

helicopters, military police, a logistics team, a commando squad, and a field hospital and Royal Netherlands Air Force AH-64 attack helicopters in support) based in Samawah

(Southern Iraq), that started deploying in 2003 after the initial invasion, left Iraq in June 2005. Netherlands lost two soldiers in separate insurgent attacks.

In January 2010, PM Balkenende found himself in dire straits after the publication of the final report of the 10 months inquiry by the Davids Commission.

Willibrord Davids was the chairman of this special committee of inquiry, charged by the Dutch government in 2009 with investigating the decision-making by the Dutch government in 2003 on the political support for the war in Iraq, which was supported then by the Dutch government following intelligence from Britain and the US. This was the first ever independent legal assessment of the invasion decision. The commissioners included the former president of the Hoge Raad (Dutch supreme court), a former judge of the European Court of Justice

, and two legal academics. Balkenende had so far resisted calls for a formal parliamentary inquiry

into the decision to back the war.

According to the report, the Dutch cabinet had failed to fully inform the Dutch House of Representatives about its support that the military action of the allies against Iraq "had no sound mandate under international law" and that the United Kingdom was instrumental in influencing the Dutch decision to back the war.

It also emerged that the British government had refused to disclose a key document requested by the Dutch panel, a letter to Balkenende from Tony Blair

in which was asked for the support. This letter was said to be handed over in a "breach of diplomatic protocol" and on the basis that it was for Balkenende's eyes only.

The letter was not sent as a note verbale

as is the normal procedure – instead it was a personal message from Blair to Balkenende, and had to be returned and not stored in the Dutch archives.

The details of the Dutch inquiry's findings and the refusal of the British government to disclose the letter were likely to increase international scrutiny on the Chilcot inquiry.

Balkenende reacted that he had fully informed of the lower house of parliament with regard to support for the invasion and that the repeated refusal by Saddam Hussain to respect UN resolutions and to co-operate with UN weapons inspectors had justified the invasion.

The Partij van de Arbeid (Dutch Labour Party), part of Balkenende's ruling coalition, demanded a new statement from the PM.

as well as Dutch naval frigates to police the waters of the Middle East/Indian Ocean

. Starting in 2006, the Netherlands deployed further troops and helicopters to Afghanistan as part of a new security operation in the south of the country. Dutch ground and air forces totalled almost 2,000 personnel during 2006, taking part in combat operations alongside British and Canadian forces as part of NATO's ISAF

force in the south. Most of the troops operated in the Uruzgan Province as part of a 3-D strategy (defense, development, diplomacy).

On November 1, 2006 Dutch Major-General Ton Van Loon took over NATO Regional Command South in Afghanistan for a six months period from the Canadians. http://www.army.forces.gc.ca/lf/English/6_1_1.asp?id=1275 See the Coalition combat operations in Afghanistan in 2006

and Battle of Chora

articles for further details. The Royal Netherlands Army

Commando

Captain Marco Kroon

was the first individual recipient of the Military William Order (the highest Dutch award for valour under fire, comparable to the Victoria Cross

and the Medal of Honor

) since 1955 for actions in Uruzgan, Afghanistan

.

Domestically, the participation was unpopular and controversial leading the government in 2007 to announce their withdrawal set for 2010. In response to requests of the American government to continue to stay in Afghanistan in 2009, the Dutch government was reported to explore new missions in Afghanistan, however, this action led to disagreements within the government culminating in its collapse in February 2010. On August 1, 2010 the Dutch military formally declared its withdrawal from its four-year mission in Afghanistan; all 1,950 soldiers are expected to be back in the Netherlands by September.

, The Dutch

: Battle of Lowestoft

). At the end the Dutch naval onslaught proved to be too strong for the English. Dutch naval dominance, together with the Great fire of London

and the spread of the black death

, eventually led to the Glorious Revolution

in which the English monarch was replaced by the Dutchman William of Orange

who had landed together with a Dutch army on English soil; it was to be the last successful invasion

of England. In the end however, this seemingly ultimate victory would prove to mark the downfall of Dutch naval power. William III made London the new major trading city of the world, and he placed the combined Anglo-Dutch fleet under English command (even though the Dutch fleet was numerically almost equal and better trained). This was to be the beginning of English worldwide naval dominance.

Despite all this rivalry, it should be remembered that England and the Netherlands had most of their conflicts in a rather limited period of time, between 1652 and 1688, and that for most of their history they were allies against Spain and France.

. Traditionally however there had never been much conflict between France and the Northern Netherlands. At first France and The Republic were allies against Spain. This changed in 1668 and between 1672 and 1713 there was a period of very intense warfare. In the early 18th century both nations were financially exhausted, to the benefit of England. They were careful not to repeat that mistake and, apart from the events in 1747, kept their peace. Nevertheless before the French revolution, the Netherlands were a source of much irritation to the Kings of France. For example: The Netherlands were a republic at that time, something which was unheard of in the 16th and 17th century, when all but a few countries in the entire world were ruled by nobility. Louis XIV had a personal antipathy against the egalitarian Dutch; on the other hand both peoples felt a mutual admiration: the Dutch for French culture; the French for Dutch trade and industry. When revolutionary French troops smashed the old Dutch regime in 1794, many Dutch welcomed this as a liberation from outdated institutions. Imperial France briefly annexed the Netherlands for a period of nearly three years during the Napoleontic wars, only to find themselves facing Dutch troops at the battle of Waterloo.

. In fact the army of 18th century Prussia was modeled after that of the Dutch republic. Though the Dutch stayed neutral during World War I, they leaned somewhat to the German side (also due to the fact that The Netherlands was caught in the British blockade of Germany

). This was shown when after the war had ended, the Dutch granted asylum to Wilhelm II, the German emperor, despite appeals to extradite him by the Allies. However it were the Allies who had plans to invade the Netherlands. That was not only because of the Dutch trade with Germany during that period of war (they also traded with the Allies), but another important factor was that the Allies saw a way to get behind the German lines and end the war more quickly. But when the Netherlands fell to the Blitzkrieg of 1940 this all changed. The Netherlands, unable to offer heavy resistance except in some isolated spots, were quickly occupied by the numerically and technically superior German army for a period of five years.

There are also other reasons why the Dutch wanted to stay neutral against Germany. Not only was there intensive trade between the two countries for over centuries even before the actual country of Germany began to exist in 1871, the Dutch also had a long history with Germany. In fact, the Dutch William of Orange-Nassau was born in Germany, and the Dutch royal family always had good connections with the elite German families. An example of this can be seen in the husbands of Queen Wilhelmina's husband Prince Hendrik, Queen Juliana's Prince Bernhard and Queen Beatrix's Prince Claus were all Germans.

, the Habsburg ruler who was Lord of the Netherlands but foremost King of Spain, so for a period of 80 years Spain was the main opponent. The Dutch made most of their colonial conquest against the Portuguese though, Portugal also being under Spanish rule. The war resulted in a Dutch victory — though also in a division of the Low Countries. The Netherlands were officially recognised and as the Spanish Empire

was dangerously weakened, Dutch policy from 1648 was to prevent its total collapse by French and British attacks.

Nation-state

The nation state is a state that self-identifies as deriving its political legitimacy from serving as a sovereign entity for a nation as a sovereign territorial unit. The state is a political and geopolitical entity; the nation is a cultural and/or ethnic entity...

dates from 1568. Belgium (a country with a Dutch-like-speaking majority) became an independent state in 1830 when it seceded from the Netherlands.

During the ancient

Migration Period

The Migration Period, also called the Barbarian Invasions , was a period of intensified human migration in Europe that occurred from c. 400 to 800 CE. This period marked the transition from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages...

and early medieval

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages was the period of European history lasting from the 5th century to approximately 1000. The Early Middle Ages followed the decline of the Western Roman Empire and preceded the High Middle Ages...

periods, the Germanic tribes had no written language. What we know about their early military history comes from accounts written in Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

and from archaeology. This causes significant gaps in the historic timeline. Germanic wars

Germanic Wars

The Germanic Wars is a name given to a series of wars between the Romans and various Germanic tribes between 113 BCE and 439 CE. The nature of these wars varied through time between Roman conquest, Germanic uprisings and later Germanic invasions in the Roman Empire that started in the late 2nd...

against the Romans

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

are fairly well documented from the Roman perspective; however, Germanic wars against the early Celts remain mysterious because neither side recorded the events. Wars between the Germanic tribes in Northern Belgium

Flanders