University of Cambridge

Encyclopedia

The University of Cambridge (informally Cambridge University or Cambridge) is a public

research university located in Cambridge

, United Kingdom

. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world (after the University of Oxford

), and the seventh-oldest globally. In post-nominals

the university's name is abbreviated as Cantab, a shortened form of Cantabrigiensis (an adjective derived from Cantabrigia, the Latinised

form of Cambridge).

The university grew out of an association of scholars in the city of Cambridge that was formed in 1209, early records suggest, by scholars leaving Oxford

after a dispute with townsfolk. The two "ancient universities" have many common features and are often jointly referred to as Oxbridge

. In addition to cultural and practical associations as a historic part of British society, they have a long history of rivalry

with each other.

Academically Cambridge ranks as one of the top universities in the world: first in the world in both the 2010 and 2011 QS World University Rankings

, sixth in the world in the 2011 Times Higher Education World University Rankings

, and fifth in the world (and first in Europe) in the 2011 Academic Ranking of World Universities

. Cambridge regularly contends with Oxford for first place in UK league tables

. In the most recently published ranking of UK universities, published by The Guardian

newspaper, Cambridge was ranked first.

Graduates of the University have won a total of 61 Nobel Prizes, the most of any university in the world. In 2009, the marketing consultancy World Brand Lab rated Cambridge University as the 50th most influential brand in the world, and the 4th most influential university brand, behind only Harvard

, MIT

and Stanford University

, while in 2011, Cambridge ranked third, after Harvard and MIT, in The Times Higher Education World Reputation Rankings, which reflect the reputation of universities for educational and research excellence based on a survey of academics worldwide.

Cambridge is a member of the Coimbra Group

, the G5

, the International Alliance of Research Universities

, the League of European Research Universities

and the Russell Group

of research-led British universities

. It forms part of the 'Golden Triangle'

of British universities.

which awarded the ius non trahi extra (a right to discipline its own members) plus some exemption from taxes, and a bull

in 1233 from Pope Gregory IX

that gave graduates from Cambridge the right to teach everywhere in Christendom.

After Cambridge was described as a studium generale

in a letter by Pope Nicholas IV

in 1290, and confirmed as such in a bull by Pope John XXII

in 1318, it became common for researchers from other European medieval universities to come and visit Cambridge to study or to give lecture

courses.

Hugh Balsham, Bishop of Ely

, founded Peterhouse

in 1284, Cambridge's first college. Many colleges were founded during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, but colleges continued to be established throughout the centuries to modern times, although there was a gap of 204 years between the founding of Sidney Sussex

in 1596 and Downing

in 1800. The most recently established college is Robinson

, built in the late 1970s. However, Homerton College

only achieved full university college status in March 2010, making it the newest full college (it was previously an "Approved Society" affiliated with the university).

In medieval times, many colleges were founded so that their members would pray

for the soul

s of the founders, and were often associated with chapels or abbey

s. A change in the colleges’ focus occurred in 1536 with the Dissolution of the Monasteries

. King Henry VIII

ordered the university to disband its Faculty of Canon Law and to stop teaching "scholastic philosophy". In response, colleges changed their curricula away from canon law and towards the classics

, the Bible, and mathematics

.

As Cambridge moved away from Canon Law so too did it move away from Catholicism. As early as the 1520s, the continental rumblings of Lutheranism

and what was to become more broadly known as the Protestant Reformation

were making their presence felt in the intellectual discourse of the university. Among the intellectuals involved was the theologically influential Thomas Cranmer

, later to become Archbishop of Canterbury

. As it became convenient to Henry VIII in the 1530s, the King looked to Cranmer and others (within and without Cambridge) to craft a new religious path that was different from Catholicism yet also different from what Martin Luther had in mind.

Nearly a century later, the university was at the centre of another Christian schism. Many nobles, intellectuals and even common folk saw the ways of the Church of England

as being all too similar to the Catholic Church and moreover that it was used by the crown to usurp the rightful powers of the counties. East Anglia

was the centre of what became the Puritan

movement and at Cambridge, it was particularly strong at Emmanuel, St Catharine's Hall, Sidney Sussex and Christ's College. They produced many "non-conformist" graduates who greatly influenced, by social position or pulpit, the approximately 20,000 Puritans who left for New England and especially the Massachusetts Bay Colony

during the Great Migration

decade of the 1630s. Oliver Cromwell

, Parliamentary commander during the English Civil War and head of the English Commonwealth (1649–1660), attended Sidney Sussex.

in the later 17th century until the mid-19th century, the university maintained a strong emphasis on applied mathematics

, particularly mathematical physics. Study of this subject was compulsory for graduation, and students were required to take an exam for the Bachelor of Arts degree, the main first degree at Cambridge in both arts and science subjects. This exam is known as a Tripos

. Students awarded first-class honours

after completing the mathematics Tripos were named wranglers. The Cambridge Mathematical Tripos

was competitive and helped produce some of the most famous names in British science, including James Clerk Maxwell

, Lord Kelvin

, and Lord Rayleigh

. However, some famous students, such as G. H. Hardy

, disliked the system, feeling that people were too interested in accumulating marks in exams and not interested in the subject itself.

Pure mathematics at Cambridge in the 19th century had great achievements but also missed out on substantial developments in French and German mathematics. Pure mathematical research at Cambridge finally reached the highest international standard in the early 20th century, thanks above all to G. H. Hardy

and his collaborator, J. E. Littlewood. In geometry, W. V. D. Hodge

brought Cambridge into the international mainstream in the 1930s.

Although diversified in its research and teaching interests, Cambridge today maintains its strength in mathematics. Cambridge alumni have won six Fields Medal

s and one Abel Prize

for mathematics, while individuals representing Cambridge have won four Fields Medals. The University also runs a special

Master of Advanced Study course in mathematics.

(founded by Emily Davies

) in 1869 and Newnham College

in 1872 (founded by Anne Clough

and Henry Sidgwick

), followed by Hughes Hall

in 1885 (founded by Elizabeth Phillips Hughes

as the Cambridge Teaching College for Women), New Hall (later renamed Murray Edwards College) in 1954, and Lucy Cavendish College

. The first women students were examined in 1882 but attempts to make women full members of the university did not succeed until 1947. Women were allowed to study courses, sit examinations, and have their results recorded from 1881; for a brief period after the turn of the twentieth century, this allowed the "steamboat ladies

" to receive ad eundem degrees from the University of Dublin

.

From 1921 women were awarded diplomas which "conferred the Title of the Degree of Bachelor of Arts". As they were not "admitted to the Degree of Bachelor of Arts" they were excluded from the governing of the university. Since students must belong to a college, and since established colleges remained closed to women, women found admissions restricted to colleges established only for women. Starting with Churchill College, all of the men's colleges began to admit women between 1972 and 1988. One women's college, Girton, also began to admit male students from 1979, but the other women's colleges did not follow suit. As a result of St Hilda's College, Oxford

, ending its ban on male students in 2008, Cambridge is now the only remaining United Kingdom University with colleges which refuse to admit males, with three such institutions (Newnham, Murray Edwards and Lucy Cavendish). In the academic year 2004–5, the university's student gender ratio, including post-graduates, was male 52%: female 48%.

A discontinued tradition is that of the wooden spoon

, the ‘prize’ awarded to the student with the lowest passing grade in the final examinations of the Mathematical Tripos. The last of these spoons was awarded in 1909 to Cuthbert Lempriere Holthouse, an oarsman of the Lady Margaret Boat Club of St John's College

. It was over one metre in length and had an oar blade for a handle. It can now be seen outside the Senior Combination Room of St John's. Since 1909, results were published alphabetically within class rather than score order. This made it harder to ascertain who the winner of the spoon was (unless there was only one person in the third class), and so the practice was abandoned.

Each Christmas Eve, BBC radio and television broadcasts The Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols

by the Choir of King's College, Cambridge

. The radio broadcast has been a national Christmas tradition since it was first transmitted in 1928 (though the festival has existed since 1918). The radio broadcast is carried worldwide by the BBC World Service

and is also syndicated to hundreds of radio stations in the USA. The first television broadcast of the festival was in 1954.

Cambridge is a collegiate university

Cambridge is a collegiate university

, meaning that it is made up of self-governing and independent colleges, each with its own property and income. Most colleges bring together academics and students from a broad range of disciplines, and within each faculty, school or department within the university, academics from many different colleges will be found.

The faculties are responsible for ensuring that lectures are given, arranging seminars, performing research and determining the syllabi for teaching, overseen by the General Board. Together with the central administration headed by the Vice-Chancellor, they make up the entire Cambridge University. Facilities such as libraries are provided on all these levels: by the University (the Cambridge University Library

), by the Faculties (Faculty libraries such as the Squire Law Library), and by the individual colleges (all of which maintain a multi-discipline library, generally aimed mainly at their undergraduates).

s, who are also members of a university department. The colleges also decide which undergraduates to admit to the university, in accordance with university regulations.

Cambridge has 31 colleges, of which three, Murray Edwards, Newnham

and Lucy Cavendish

, admit women only. The other colleges are mixed, though most were originally all-male. Darwin

was the first college to admit both men and women, while Churchill

, Clare, and King's

were the first previously all-male colleges to admit female undergraduates, in 1972. In 1988 Magdalene

became the last all-male college to accept women. Clare Hall

and Darwin

admit only postgraduates, and Hughes Hall

, Lucy Cavendish

, St Edmund's

and Wolfson

admit only mature (i.e. 21 years or older on date of matriculation) students, including graduate students. All other colleges admit both undergraduate and postgraduate students with no age restrictions.

Colleges are not required to admit students in all subjects, with some colleges choosing not to offer subjects such as architecture, history of art or theology, but most offer close to the complete range. Some colleges maintain a bias towards certain subjects, for example with Churchill leaning towards the sciences and engineering, while others such as St Catharine's

aim for a balanced intake. Costs to students (accommodation and food prices) vary considerably from college to college. Others maintain much more informal reputations, such as for the students of King's College to hold left-wing political views, or Robinson College and Churchill College's attempts to minimise its environmental impact.

There are also several theological colleges in Cambridge, separate from Cambridge University, including Westcott House

, Westminster College

and Ridley Hall Theological College

, that are, to a lesser degree, affiliated to the university and are members of the Cambridge Theological Federation

.

The concept of grading students' work quantitatively was developed by a tutor named William Farish

at the University of Cambridge in 1792.

A "School" in the University of Cambridge is a broad administrative grouping of related faculties and other units. Each has an elected supervisory body—the "Council" of the school—comprising representatives of the constituent bodies. There are six schools:

Teaching and research in Cambridge is organised by faculties. The faculties have different organisational sub-structures which partly reflect their history and partly their operational needs, which may include a number of departments and other institutions. In addition, a small number of bodies entitled 'Syndicates' have responsibilities for teaching and research, e.g. Cambridge Assessment

, the University Press

, and the University Library

.

lasts from October to December; Lent Term

from January to March; and Easter Term

from April to June.

Within these terms undergraduate teaching takes place within eight-week periods called Full Term

s. These terms are shorter than those of many other British universities. Undergraduates are also expected to prepare heavily in the three holidays (known as the Christmas, Easter and Long Vacations).

, following the retirement of the Duke of Edinburgh

on his 90th birthday in June, 2011. Lord Sainsbury was nominated by the official Nomination Board to succeed him, and Abdul Arain, owner of a local grocery store, Brian Blessed

and Michael Mansfield

were also nominated. The election

took place on 14 and 15 October 2011. David Sainsbury won the election taking 2,893 of the 5,888 votes cast, winning on the first count.

The current Vice-Chancellor is Leszek Borysiewicz

. While the Chancellor's office is ceremonial, the Vice-Chancellor is the de facto principal administrative officer of the University. The university's internal governance is carried out almost entirely by its own members, with very little external representation on its governing body, the Regent House (though there is external representation on the Audit Committee, and there are four external members on the University's Council

, who are the only external members of the Regent House).

was abolished in 1950. Prior to 1926, it was the University's governing body, fulfilling the functions that the Regent House

fulfils today. The Regent House is the University's governing body, a direct democracy comprising all resident senior members of the University and the Colleges, together with the Chancellor, the High Steward

, the Deputy High Steward, and the Commissary. The public representatives of the Regent House are the two Proctor

s, elected to serve for one year, on the nomination of the Colleges.

is the principal executive and policy-making body of the University, therefore, it must report and be accountable to the Regent House

through a variety of checks and balances. It has the right of reporting to the University, and is obliged to advise the Regent House on matters of general concern to the University. It does both of these by causing notices to be published by authority in the Cambridge University Reporter

, the official journal of the University. Since January 2005, the membership of the Council has included two external members, and the Regent House voted for an increase from two to four in the number of external members in March 2008, and this was approved by Her Majesty the Queen in July 2008.

The General Board of the Faculties is responsible for the academic and educational policy of the University, and is accountable to the Council for its management of these affairs.

Faculty Boards are responsible to the General Board; other Boards and Syndicates are responsible either to the General Board (if primarily for academic purposes) or to the Council. In this way, the various arms of the University are kept under the supervision of the central administration, and thus the Regent House.

Each college is an independent charitable institution with its own endowment, separate from that of the central university endowment.

If ranked on a US university endowment table on most recent figures, Cambridge would rank fourth in a ranking compared with the eight Ivy League institutions (subject to market fluctuations).

Comparisons between Cambridge's endowment and those of other top US universities are, however, inaccurate because being a state-funded public university (although the status of Cambridge as a public university can not be compared with US or European public universities as, for example, the state do not "own" the university), Cambridge receives a major portion of its income through education and research grants from the British Government. In 2006-7, it was reported that approximately one third of Cambridge's income comes from UK government funding for teaching and research, with another third coming from other research grants. Endowment income contributes around £130 million. The University also receives a significant income in annual transfers from the Cambridge University Press

, which is the oldest, and second largest university press in the world.

of Microsoft

donated US$210 million through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to endow the Gates Scholarships for students from outside the UK seeking postgraduate study at Cambridge. The University of Cambridge Computer Laboratory

, which taught the world's first computing course in 1953, is housed in a building partly funded by Gates and named after his father, William Gates.

In 2005, the Cambridge 800th Anniversary Campaign was launched, aimed at raising £1 billion by 2012—the first US-style university fund-raising campaign in Europe. This aim was reached in the financial year 2009-2010, with raising £1.037 billion.

is the central research library, which holds over 8 million volumes and, in contrast with the Bodleian or the British Library, many of its books are available on open shelves, and most books are borrowable. It is a legal deposit library, therefore it is entitled to request a free copy of every book published in the UK and Ireland. It receives around 80,000 books every year, not counting the books donated to the library. In addition to the University Library and its dependent libraries, every faculty has a specialised library, which, on average, holds from 30,000 to 150,000 books; for example the History Faculty's Seeley Historical Library

posess more than 100.000 books. Also, every college has a library as well, partially for the purposes of undergraduate teaching, and the older colleges often possess many early books and manuscripts in a separate library. For example Trinity College's Wren Library, Cambridge

has more than 200,000 books printed before 1800, while the Parker Library, Corpus Christi College posess one of the greatest early medieval Anglo-Saxon manuscript collections in the World, with over 600 manuscripts. The total number of books owned by the university is about 12 million.

Cambridge University operates eight arts, cultural, and scientific museums, and a botanic garden:

Cambridge is a member of the Russell Group

, a network of research-led British universities; the Coimbra Group

, an association of leading European universities; the League of European Research Universities

; and the International Alliance of Research Universities

. It is also considered part of the "Golden Triangle"

, a geographical concentration of UK university research.

Building on its reputation for enterprise, science and technology, Cambridge has a partnership with MIT in the United States, the Cambridge–MIT Institute.

How applicants perform in the interview process is an important factor in determining which students are accepted. Most applicants are expected to be predicted at least three A-grade A-level qualifications relevant to their chosen undergraduate course, or equivalent overseas qualifications, such as getting at least 7,7,6 for higher-level subjects at IB. The A* A-level grade (introduced in 2010) now plays a part in the acceptance of applications, with the university's standard offer for all courses being set at A*AA. Due to a very high proportion of applicants receiving the highest school grades, the interview process is crucial for distinguishing between the most able candidates. In 2006, 5,228 students who were rejected went on to get 3 A levels or more at grade A, representing about 63% of all applicants rejected. The interview is performed by College Fellows, who evaluate candidates on unexamined factors such as potential for original thinking and creativity. For exceptional candidates, a Matriculation Offer is sometimes offered, requiring only two A-levels at grade E or above—Christ's College

is unusual in making this offer to about one-third of successful candidates, in order to relieve very able candidates of some pressure in their final year.

Applicants who are not successful at their college interview may be placed in the Winter Pool

which is a process where strong applicants can be offered places by other colleges.

Graduate admission is first decided by the faculty or department relating to the applicant's subject. This effectively guarantees admission to a college—though not necessarily the applicant's preferred choice.

's reputation for many years, and the University has encouraged pupils from state schools to apply for Cambridge to help redress the imbalance. Others counter that government pressure to increase state school admissions constitutes inappropriate social engineering

. The proportion of undergraduates drawn from independent schools has dropped over the years, and such applicants now form only a significant minority (43%) of the intake. In 2005, 32% of the 3599 applicants from independent schools were admitted to Cambridge, as opposed to 24% of the 6674 applications from state schools. In 2008 the University of Cambridge received a gift of £4m to improve its accessibility to candidates from maintained schools. Cambridge, together with Oxford and Durham

, is among those universities that have adopted formulae that gives a rating to the GCSE

performance of every school in the country to "weight" the scores of university applicants.

Both the University's central Student Union, and individual college student unions (JCRs) run student led Access schemes aimed at encouraging applications to the University from students at schools with little or no history of Oxbridge applications, and from students from families with little or no history of participation in university education.

In the last two British Government Research Assessment Exercise

In the last two British Government Research Assessment Exercise

in 2001 and 2008 respectively, Cambridge was ranked first in the country. In 2005, it was reported that Cambridge produces more PhDs per year than any other British university (over 30% more than second placed Oxford). In 2006, a Thomson Scientific

study showed that Cambridge has the highest research paper output of any British university, and is also the top research producer (as assessed by total paper citation count) in 10 out of 21 major British research fields analysed. Another study published the same year by Evidence showed that Cambridge won a larger proportion (6.6%) of total British research grants and contracts than any other university (coming first in three out of four broad discipline fields).

The university is also closely linked with the development of the high-tech business cluster

in and around Cambridge, which forms the area known as Silicon Fen

or sometimes the "Cambridge Phenomenon". In 2004, it was reported that Silicon Fen was the second largest venture capital

market in the world, after Silicon Valley

. Estimates reported in February 2006 suggest that there were about 250 active startup companies

directly linked with the university, worth around US$6 billion.

In 2011, Cambridge was ranked sixth in the world by the Times Higher Education World University Rankings

. In 2011 it came first, for a second time, in both the QS World University Rankings

and the annual World's Best Universities by U.S. News & World Report

. In 2010, according to University Ranking by Academic Performance (URAP), it is the 2nd university in UK and 11th university in the world. In the 2009 Times Higher Education-QS World University Rankings (in 2010 Times Higher Education World University Rankings

and QS World University Rankings

parted ways to produce separate rankings), Cambridge was ranked 2nd amongst world universities, behind Harvard

. It came in first in the international academic reputation peer review, first in the natural science

s, second in biomedicine

, third in the arts & humanities

, fourth in the social sciences

, and fourth in technology. The Independent Complete University Guide ranked Cambridge 2nd to Oxford in the United Kingdom. In the 2011 Academic Ranking of World Universities

compiled by Shanghai Jiao Tong University

, Cambridge was placed 5th amongst world universities and was ranked 1st in Europe. A 2006 Newsweek

ranking which combined elements of the THES-QS and ARWU rankings with other factors that purportedly evaluated an institution's global "openness and diversity" suggested that Cambridge was ranked 6th in the world overall.

In the 2008 Sunday Times University Guide, Cambridge was ranked first for the 11th straight year since the guide's first publication in 1998. In the 2008 Times Good University Guide, Cambridge topped 37 of the guide's 61 subject tables, including Law, Medicine, Economics, Mathematics

, Engineering, Physics

, and Chemistry

and has the best record on research, entry standards and graduate destinations amongst UK universities. Cambridge was also awarded the University of the Year award.

In the 2009 The Times Good University Guide Subject Rankings, Cambridge was ranked top (or joint top) in 34 out of the 42 subjects which it offers. The overall ranking placed Cambridge in 2nd behind Oxford. The 2009 Guardian University Guide Rankings also placed Cambridge 2nd in the UK behind Oxford.

In the Guardian

newspaper's 2012 rankings, Cambridge pulled ahead of Oxford to secure 1st place in the league table. Cambridge had overtaken Oxford in philosophy, law, politics, theology, maths, classics, anthropology and modern languages in the Guardian subject rankings.

, is the oldest printer and publisher in the world, and it is the second largest university press in the world.

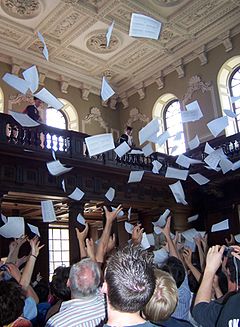

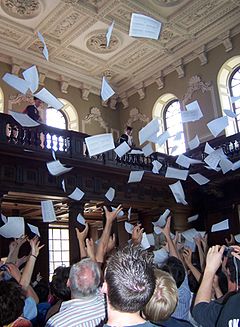

, and must be voted on as with any other act. A formal meeting of the Regent House, known as a Congregation

, is held for this purpose.

Graduates receiving an undergraduate degree wear the academical dress that they were entitled to before graduating: for example, most students becoming Bachelors of Arts wear undergraduate gowns and not BA gowns. Graduates receiving a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD or Master's) wear the academical dress that they were entitled to before graduating, only if their first degree was also from the University of Cambridge; if their first degree is from another university, they wear the academical dress of the degree that they are about to receive, the BA gown without the strings if they are under 24 years of age, or the MA gown without strings if they are 24 and over.

Graduands are presented in the Senate House college by college, in order of foundation or recognition by the university (except for the royal colleges), as follows.

During the congregation, graduands are brought forth by the Praelector of their college, who takes them by the right hand, and presents them to the vice-chancellor for the degree they are about to take. The Praelector presents male graduands with the following Latin statement, substituting "____" with the name of the degree:

During the congregation, graduands are brought forth by the Praelector of their college, who takes them by the right hand, and presents them to the vice-chancellor for the degree they are about to take. The Praelector presents male graduands with the following Latin statement, substituting "____" with the name of the degree:

and female graduands with the following:

After presentation, the graduand is called by name and kneels before the vice-chancellor and proffers their hands to the vice-chancellor, who clasps them and then confers the degree through the following Latin statement—the Trinitarian formula (in italics) may be omitted at the request of the graduand:

The now-graduate then rises, bows and leaves the Senate House through the Doctor's door, where he or she receives his or her certificate, into Senate House passage.

is a particularly popular sport at Cambridge, and there are competitions between colleges, notably the bumps race

s, and against Oxford, the Boat Race. There are also Varsity match

es against Oxford in many other sports, ranging from cricket

and rugby

, to chess

and tiddlywinks

. Athletes representing the university in certain sports entitle them to apply for a Cambridge Blue at the discretion of the Blues Committee, consisting of the captains of the thirteen most prestigious sports. There is also the self-described "unashamedly elite" Hawks’ Club

, which is for men only, whose membership is usually restricted to Cambridge Full Blues and Half Blues.

and the comedy club Footlights

, which are known for producing well-known show-business personalities. Student newspapers include the long-established Varsity and its younger rival, The Cambridge Student

. In the last year, both have been challenged by the emergence of The Tab

, Cambridge's first student tabloid. The student-run radio station, Cam FM, provides members with an opportunity to produce and host weekly radio shows and promotes broadcast journalism, sports coverage, comedy and drama.

The Cambridge University Chamber Orchestra explores a range of programmes, from popular symphonies to lesser known works. Membership of the orchestra is composed of students of the university and it has also attracted a variety of conductors and soloists, including Wayne Marshall, Jane Glover

, and Nicholas Cleobury

. Cambridge is also home to a number of recreational outdoor societies, such as the Cambridge University Punting Society

.

s, more than any other institution according to some counts. Former undergraduates of the university have won a grand total of 61 Nobel prizes, 13 more than the undergraduates of any other university. Cambridge academics have also won 8 Fields Medal

s and 2 Abel Prize

s (since the award was first distributed in 2003).

Perhaps most of all, the university is renowned for a long and distinguished tradition in mathematics and the sciences.

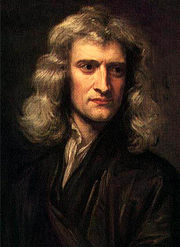

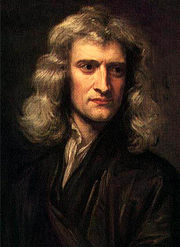

Among the most famous of Cambridge natural philosophers is Sir Isaac Newton, who spent the majority of his life at the university and conducted many of his now famous experiments within the grounds of Trinity College. Sir Francis Bacon, responsible for the development of the Scientific Method

, entered the university when he was just twelve, and pioneering mathematicians John Dee

and Brook Taylor

soon followed.

Other ground-breaking mathematicians to have studied at the university include Hardy

, Littlewood

and De Morgan

, three of the most renowned pure mathematicians

in modern history; Sir Michael Atiyah, one of the most important mathematicians of the last half-century; William Oughtred

, the inventor of the logarithmic scale

; John Wallis, the inventor of modern calculus

; Srinivasa Ramanujan

, the self-taught genius who made incomparable contributions to mathematical analysis

, number theory

, infinite series and continued fractions; and, perhaps most importantly of all, James Clerk Maxwell

, who is considered to have brought about the second great unification of Physics (the first being accredited to Newton) with his classical electromagnetic theory. In biology, Charles Darwin

In biology, Charles Darwin

, famous for developing the theory of natural selection

, was a Cambridge man. Subsequent Cambridge biologists include Francis Crick

and James Watson

, who worked out a model for the three-dimensional structure of DNA

whilst working at the university's Cavendish Laboratory

along with leading X-ray crystallographer Maurice Wilkins

and Rosalind Franklin

. More recently, Sir Ian Wilmut

, the man who was responsible for the first cloning of a mammal with Dolly the Sheep

in 1996, was a graduate student at Darwin College. Famous naturalist and broadcaster David Attenborough

graduated from the university, while the ethologist Jane Goodall

, the world's foremost expert on chimpanzees did a PhD in Cambridge without having a first degree.

The university can be considered the birthplace of the computer, with mathematician Charles Babbage

having designed the world's first computing system as early as the mid-1800s. Alan Turing

went on to devise what is essentially the basis for modern computing and Maurice Wilkes later created the first programmable computer. The webcam

was also invented at Cambridge University, as a means for scientists to avoid interrupting their research and going all the way down to the laboratory dining room only to be disappointed by an empty coffee pot.

Lord Rutherford

Lord Rutherford

, generally regarded as the father of nuclear physics

, spent much of his life at the university, where he worked closely with the likes of Niels Bohr

, a major contributor to the understanding of the structure and function of the atom

, J. J. Thompson, discoverer of the electron

, Sir James Chadwick, discoverer of the neutron

, and Sir John Cockcroft

and Ernest Walton

, the partnership responsible for first splitting the atom. J. Robert Oppenheimer, leader of the Manhattan Project

that developed the atomic bomb, also studied at Cambridge under Rutherford and Thompson.

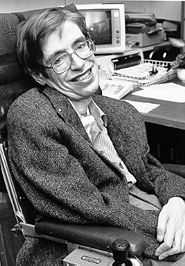

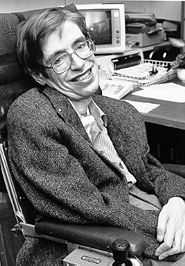

Astronomers Sir John Herschel and Sir Arthur Eddington both spent much of their careers at Cambridge, as did Paul Dirac

, the discoverer of antimatter

and one of the pioneers of Quantum Mechanics

; Stephen Hawking

, the founding father of the study of singularities

and the university's long-serving Lucasian Professor of Mathematics; and Lord Martin Rees

, the current Astronomer Royal

and Master of Trinity College.

Other significant Cambridge scientists include Henry Cavendish

Other significant Cambridge scientists include Henry Cavendish

, the discoverer of Hydrogen

; Frank Whittle

, co-inventor of the jet engine; Lord Kelvin, who formulated the original Laws of Thermodynamics

; William Fox Talbot

, who invented the camera, Alfred North Whitehead

, Einstein's major opponent; Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose, the man dubbed "the father of radio science"; Lord Rayleigh, one of the most pre-eminent physicists of the 20th century; Georges Lemaître

, who first proposed the Big Bang

Theory; and Frederick Sanger

, the last man to win two Nobel prizes.

In the humanities, Greek studies were inaugurated at Cambridge in the early sixteenth century by Desiderius Erasmus

during the few years he held a professorship there; seminal contributions to them were made by Richard Bentley

and Richard Porson

. John Chadwick

was associated with Michael Ventris

in the decipherment of Linear B. The eminent Latinist A. E. Housman

taught at Cambridge but is more widely known as a poet. Simon Ockley

made a significant contribution to Arabic studies.

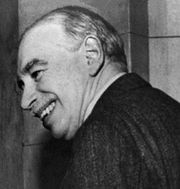

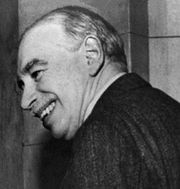

Distinguished Cambridge academics in other fields include economists such as John Maynard Keynes

, Thomas Malthus

, Alfred Marshall

, Milton Friedman

, Joan Robinson

, Piero Sraffa

, and Amartya Sen

, another former Master of Trinity College. Philosophers Sir Francis Bacon, Bertrand Russell

, Ludwig Wittgenstein

, Leo Strauss

, George Santayana

, G. E. M. Anscombe

, Sir Karl Popper

, Sir Bernard Williams

, Allama Iqbal and G. E. Moore were all Cambridge scholars, as were historians such as Thomas Babington Macaulay, Frederic William Maitland

, Lord Acton, Joseph Needham

, Dom David Knowles

, E. H. Carr, Hugh Trevor-Roper, E. P. Thompson

, Eric Hobsbawm

, Niall Ferguson

, Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr and lawyers Glanville Williams, Sir James Fitzjames Stephen

, and Sir Edward Coke.

Religious figures at the university have included Rowan Williams

, the current Archbishop of Canterbury

and many of his predecessors; William Tyndale

, the pioneer biblical translator; Thomas Cranmer

, Hugh Latimer

, and Nicholas Ridley

, all Cambridge men, known as the "Oxford martyrs" from the place of their execution; Benjamin Whichcote

, the Cambridge Platonist; William Paley

, the Christian philosopher known primarily for formulating the teleological argument

for the existence of God; William Wilberforce

and Thomas Clarkson

, largely responsible for the abolition

of the slave trade; leading Evangelical churchman Charles Simeon

; John William Colenso

, bishop of Natal, who developed views on the interpretation of Scripture and relations with native peoples that seemed dangerously radical at the time; John Bainbridge Webster

and David F. Ford

, theologians of significant repute; and six winners of the prestigious Templeton Prize

, the highest accolade for the study of religion since its foundation in 1972.

Composers Ralph Vaughan Williams

, Sir Charles Villiers Stanford, William Sterndale Bennett

, Orlando Gibbons

and, more recently, Alexander Goehr

, Thomas Adès

and John Rutter

were all at Cambridge. The university has also produced members of contemporary bands such as Radiohead

, Hot Chip

, Procol Harum

, Henry Cow

, and the singer-songwriter Nick Drake

.

Artists Quentin Blake

, Roger Fry

and Julian Trevelyan

also attended as undergraduates, as did sculptors Antony Gormley

, Marc Quinn

and Sir Anthony Caro

, and photographers Antony Armstrong-Jones, Sir Cecil Beaton

and Mick Rock

.

Acclaimed writers such as E. M. Forster

, Samuel Pepys

, Charles Kingsley

, C. S. Lewis

, Christopher Marlowe

, Vladmir Nabokov, Christopher Isherwood

, Samuel Butler

, W. M. Thackeray, Lawrence Sterne, Eudora Welty

, Sir Kingsley Amis, C. P. Snow

, J. G. Ballard

, Malcolm Lowry

, E. R. Braithwaite

, Iris Murdoch

, J. B. Priestley

, Patrick White

, M. R. James

and A. A. Milne

were all at Cambridge.

More recently A. S. Byatt

, Margaret Drabble, Douglas Adams

, Sir Salman Rushdie, Nick Hornby

, Zadie Smith

, Howard Jacobson

, Robert Harris

, Jin Yong, Michael Crichton

, Sebastian Faulks

, Julian Fellowes

, Stephen Poliakoff

, Michael Frayn

, Alan Bennett

and Sir Peter Shaffer

were all at the university.

Poets A. E. Housman

, Robert Herrick

, William Wordsworth

, John Donne

, Alfred Tennyson, Lord Byron, Rupert Brooke

, John Dryden

, Siegfried Sassoon

, Ted Hughes

, Sylvia Plath

, John Milton

, George Herbert

, Samuel Taylor Coleridge

, Thomas Gray

, Edmund Spenser

, Cecil Day-Lewis

and Sir Muhammad Iqbal

are all associated with Cambridge, as are renowned literary critics F. R. Leavis

, Sir William Empson, Lytton Strachey

, I. A. Richards

, Raymond Williams

, Harold Bloom

, Terry Eagleton

, Stephen Greenblatt

and Peter Ackroyd

. Furthermore, at least nine of the Poet Laureate

s graduated from Cambridge.

Actors and directors such as Sir Ian McKellen

, Sir Derek Jacobi

, Sir Michael Redgrave

, James Mason

, Emma Thompson

, Stephen Fry

, Hugh Laurie

, John Cleese

, Eric Idle

, Graham Chapman

, Simon Russell Beale

, Tilda Swinton

, Thandie Newton

, Rachel Weisz

, Sacha Baron Cohen

, Eddie Redmayne

and David Mitchell

all studied at the university, as did recently acclaimed directors such as Mike Newell

, Sam Mendes

, Stephen Frears

, Paul Greengrass

and John Madden

.

The University is also known for its prodigious sporting reputation and has produced many fine athletes, including more than 50 Olympic medalists (6 in 2008 alone); the legendary Chinese six-time world table tennis champion Deng Yaping

The University is also known for its prodigious sporting reputation and has produced many fine athletes, including more than 50 Olympic medalists (6 in 2008 alone); the legendary Chinese six-time world table tennis champion Deng Yaping

; the sprinter and athletics hero Harold Abrahams

; the inventors of the modern game of Football, Winton and Thring

; and George Mallory

, the famed mountaineer and possibly the first man ever to reach the summit of Mount Everest

.

Notable educationalists to have attended the university include the founders and early professors of Harvard University

, including John Harvard

himself; Emily Davies

, founder of Girton College, the first residential higher education institution for women, and John Haden Badley

, founder of the first mixed-sex school in England.

Cambridge also has a strong reputation in the fields of politics and governance, having educated:

Public university

A public university is a university that is predominantly funded by public means through a national or subnational government, as opposed to private universities. A national university may or may not be considered a public university, depending on regions...

research university located in Cambridge

Cambridge

The city of Cambridge is a university town and the administrative centre of the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It lies in East Anglia about north of London. Cambridge is at the heart of the high-technology centre known as Silicon Fen – a play on Silicon Valley and the fens surrounding the...

, United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world (after the University of Oxford

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

), and the seventh-oldest globally. In post-nominals

Post-nominal letters

Post-nominal letters, also called post-nominal initials, post-nominal titles or designatory letters, are letters placed after the name of a person to indicate that the individual holds a position, educational degree, accreditation, office, or honour. An individual may use several different sets of...

the university's name is abbreviated as Cantab, a shortened form of Cantabrigiensis (an adjective derived from Cantabrigia, the Latinised

Latinisation (literature)

Latinisation is the practice of rendering a non-Latin name in a Latin style. It is commonly met with for historical personal names, with toponyms, or for the standard binomial nomenclature of the life sciences. It goes further than Romanisation, which is the writing of a word in the Latin alphabet...

form of Cambridge).

The university grew out of an association of scholars in the city of Cambridge that was formed in 1209, early records suggest, by scholars leaving Oxford

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

after a dispute with townsfolk. The two "ancient universities" have many common features and are often jointly referred to as Oxbridge

Oxbridge

Oxbridge is a portmanteau of the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge in England, and the term is now used to refer to them collectively, often with implications of perceived superior social status...

. In addition to cultural and practical associations as a historic part of British society, they have a long history of rivalry

Oxbridge rivalry

Rivalry between the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge is a phenomenon going back many centuries. During most of that time, the two were the only universities in England and Wales, making the rivalry more intense than it is now....

with each other.

Academically Cambridge ranks as one of the top universities in the world: first in the world in both the 2010 and 2011 QS World University Rankings

QS World University Rankings

The QS World University Rankings is a ranking of the world’s top 500 universities by Quacquarelli Symonds using a method that has published annually since 2004....

, sixth in the world in the 2011 Times Higher Education World University Rankings

Times Higher Education World University Rankings

The Times Higher Education World University Rankings is an international ranking of universities published by the British magazine Times Higher Education in partnership with Thomson Reuters, which provided citation database information...

, and fifth in the world (and first in Europe) in the 2011 Academic Ranking of World Universities

Academic Ranking of World Universities

The Academic Ranking of World Universities , commonly known as the Shanghai ranking, is a publication that was founded and compiled by the Shanghai Jiaotong University to rank universities globally. The rankings have been conducted since 2003 and updated annually...

. Cambridge regularly contends with Oxford for first place in UK league tables

League tables of British universities

Rankings of universities in the United Kingdom are published annually by The Guardian, The Independent, The Sunday Times and The Times...

. In the most recently published ranking of UK universities, published by The Guardian

The Guardian

The Guardian, formerly known as The Manchester Guardian , is a British national daily newspaper in the Berliner format...

newspaper, Cambridge was ranked first.

Graduates of the University have won a total of 61 Nobel Prizes, the most of any university in the world. In 2009, the marketing consultancy World Brand Lab rated Cambridge University as the 50th most influential brand in the world, and the 4th most influential university brand, behind only Harvard

Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States, established in 1636 by the Massachusetts legislature. Harvard is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States and the first corporation chartered in the country...

, MIT

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology is a private research university located in Cambridge, Massachusetts. MIT has five schools and one college, containing a total of 32 academic departments, with a strong emphasis on scientific and technological education and research.Founded in 1861 in...

and Stanford University

Stanford University

The Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University or Stanford, is a private research university on an campus located near Palo Alto, California. It is situated in the northwestern Santa Clara Valley on the San Francisco Peninsula, approximately northwest of San...

, while in 2011, Cambridge ranked third, after Harvard and MIT, in The Times Higher Education World Reputation Rankings, which reflect the reputation of universities for educational and research excellence based on a survey of academics worldwide.

Cambridge is a member of the Coimbra Group

Coimbra Group

The Coimbra Group is a network of 40 European universities, some among the oldest and most prestigious in Europe. It was founded in 1985 and formally constituted by charter in 1987....

, the G5

G5 (education)

The G5 is an informal grouping of five British universities first identified by Times Higher Education in 2004. According to Times Higher Education, the five members are the University of Cambridge, Imperial College London, the London School of Economics, the University of Oxford and University...

, the International Alliance of Research Universities

International Alliance of Research Universities

The International Alliance of Research Universities was launched on 14 January 2006 as a co-operative network of 10 leading, international research-intensive universities who share similar visions for higher education, in particular the education of future leaders...

, the League of European Research Universities

League of European Research Universities

The League of European Research Universities is a consortium of Europe's most prominent and renowned research universities.-History and Overview:...

and the Russell Group

Russell Group

The Russell Group is a collaboration of twenty UK universities that together receive two-thirds of research grant and contract funding in the United Kingdom. It was established in 1994 to represent their interests to the government, parliament and other similar bodies...

of research-led British universities

British universities

Universities in the United Kingdom have generally been instituted by Royal Charter, Papal Bull, Act of Parliament or an instrument of government under the Education Reform Act 1988; in any case generally with the approval of the Privy Council, and only such recognised bodies can award degrees of...

. It forms part of the 'Golden Triangle'

Golden Triangle (UK universities)

The "Golden Triangle" is a term used to describe a number of leading British research universities based in Cambridge, London and Oxford.The city of Cambridge, represented by the University of Cambridge, and the city of Oxford, represented by the University of Oxford, form two corners of the triangle...

of British universities.

History

Cambridge's status was enhanced by a charter in 1231 from King Henry III of EnglandHenry III of England

Henry III was the son and successor of John as King of England, reigning for 56 years from 1216 until his death. His contemporaries knew him as Henry of Winchester. He was the first child king in England since the reign of Æthelred the Unready...

which awarded the ius non trahi extra (a right to discipline its own members) plus some exemption from taxes, and a bull

Papal bull

A Papal bull is a particular type of letters patent or charter issued by a Pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the bulla that was appended to the end in order to authenticate it....

in 1233 from Pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX, born Ugolino di Conti, was pope from March 19, 1227 to August 22, 1241.The successor of Pope Honorius III , he fully inherited the traditions of Pope Gregory VII and of his uncle Pope Innocent III , and zealously continued their policy of Papal supremacy.-Early life:Ugolino was...

that gave graduates from Cambridge the right to teach everywhere in Christendom.

After Cambridge was described as a studium generale

Studium Generale

Studium generale is the old customary name for a Medieval university.- Definition :There is no clear official definition of what constituted a Studium generale...

in a letter by Pope Nicholas IV

Pope Nicholas IV

Pope Nicholas IV , born Girolamo Masci, was Pope from February 22, 1288 to April 4, 1292. A Franciscan friar, he had been legate to the Greeks under Pope Gregory X in 1272, succeeded Bonaventure as Minister General of his religious order in 1274, was made Cardinal Priest of Santa Prassede and...

in 1290, and confirmed as such in a bull by Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII

Pope John XXII , born Jacques Duèze , was pope from 1316 to 1334. He was the second Pope of the Avignon Papacy , elected by a conclave in Lyon assembled by Philip V of France...

in 1318, it became common for researchers from other European medieval universities to come and visit Cambridge to study or to give lecture

Lecture

thumb|A lecture on [[linear algebra]] at the [[Helsinki University of Technology]]A lecture is an oral presentation intended to present information or teach people about a particular subject, for example by a university or college teacher. Lectures are used to convey critical information, history,...

courses.

Foundation of the colleges

Cambridge's colleges were originally an incidental feature of the system. No college is as old as the university itself. The colleges were endowed fellowships of scholars. There were also institutions without endowments, called hostels. The hostels were gradually absorbed by the colleges over the centuries, but they have left some indicators of their time, such as the name of Garret Hostel Lane.Hugh Balsham, Bishop of Ely

Bishop of Ely

The Bishop of Ely is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Ely in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese roughly covers the county of Cambridgeshire , together with a section of north-west Norfolk and has its see in the City of Ely, Cambridgeshire, where the seat is located at the...

, founded Peterhouse

Peterhouse, Cambridge

Peterhouse is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. It is the oldest college of the University, having been founded in 1284 by Hugo de Balsham, Bishop of Ely...

in 1284, Cambridge's first college. Many colleges were founded during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, but colleges continued to be established throughout the centuries to modern times, although there was a gap of 204 years between the founding of Sidney Sussex

Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge

Sidney Sussex College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England.The college was founded in 1596 and named after its foundress, Frances Sidney, Countess of Sussex. It was from its inception an avowedly Puritan foundation: some good and godlie moniment for the mainteynance...

in 1596 and Downing

Downing College, Cambridge

Downing College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1800 and currently has around 650 students.- History :...

in 1800. The most recently established college is Robinson

Robinson College, Cambridge

Robinson College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge.Robinson is the newest of the Cambridge colleges, and is unique in being the only one to have been intended, from its inception, for both undergraduate and graduate students of either sex.- History :The college was founded...

, built in the late 1970s. However, Homerton College

Homerton College, Cambridge

Homerton College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England.With around 1,200 students, Homerton has more students than any other Cambridge college, although less than half of these live in the college. The college has a long and complex history dating back to the...

only achieved full university college status in March 2010, making it the newest full college (it was previously an "Approved Society" affiliated with the university).

In medieval times, many colleges were founded so that their members would pray

Prayer

Prayer is a form of religious practice that seeks to activate a volitional rapport to a deity through deliberate practice. Prayer may be either individual or communal and take place in public or in private. It may involve the use of words or song. When language is used, prayer may take the form of...

for the soul

Soul

A soul in certain spiritual, philosophical, and psychological traditions is the incorporeal essence of a person or living thing or object. Many philosophical and spiritual systems teach that humans have souls, and others teach that all living things and even inanimate objects have souls. The...

s of the founders, and were often associated with chapels or abbey

Abbey

An abbey is a Catholic monastery or convent, under the authority of an Abbot or an Abbess, who serves as the spiritual father or mother of the community.The term can also refer to an establishment which has long ceased to function as an abbey,...

s. A change in the colleges’ focus occurred in 1536 with the Dissolution of the Monasteries

Dissolution of the Monasteries

The Dissolution of the Monasteries, sometimes referred to as the Suppression of the Monasteries, was the set of administrative and legal processes between 1536 and 1541 by which Henry VIII disbanded monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England, Wales and Ireland; appropriated their...

. King Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

ordered the university to disband its Faculty of Canon Law and to stop teaching "scholastic philosophy". In response, colleges changed their curricula away from canon law and towards the classics

Classics

Classics is the branch of the Humanities comprising the languages, literature, philosophy, history, art, archaeology and other culture of the ancient Mediterranean world ; especially Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome during Classical Antiquity Classics (sometimes encompassing Classical Studies or...

, the Bible, and mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

.

As Cambridge moved away from Canon Law so too did it move away from Catholicism. As early as the 1520s, the continental rumblings of Lutheranism

Lutheranism

Lutheranism is a major branch of Western Christianity that identifies with the theology of Martin Luther, a German reformer. Luther's efforts to reform the theology and practice of the church launched the Protestant Reformation...

and what was to become more broadly known as the Protestant Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

were making their presence felt in the intellectual discourse of the university. Among the intellectuals involved was the theologically influential Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build a favourable case for Henry's divorce from Catherine of Aragon which resulted in the separation of the English Church from...

, later to become Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

. As it became convenient to Henry VIII in the 1530s, the King looked to Cranmer and others (within and without Cambridge) to craft a new religious path that was different from Catholicism yet also different from what Martin Luther had in mind.

Nearly a century later, the university was at the centre of another Christian schism. Many nobles, intellectuals and even common folk saw the ways of the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

as being all too similar to the Catholic Church and moreover that it was used by the crown to usurp the rightful powers of the counties. East Anglia

East Anglia

East Anglia is a traditional name for a region of eastern England, named after an ancient Anglo-Saxon kingdom, the Kingdom of the East Angles. The Angles took their name from their homeland Angeln, in northern Germany. East Anglia initially consisted of Norfolk and Suffolk, but upon the marriage of...

was the centre of what became the Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

movement and at Cambridge, it was particularly strong at Emmanuel, St Catharine's Hall, Sidney Sussex and Christ's College. They produced many "non-conformist" graduates who greatly influenced, by social position or pulpit, the approximately 20,000 Puritans who left for New England and especially the Massachusetts Bay Colony

Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was an English settlement on the east coast of North America in the 17th century, in New England, situated around the present-day cities of Salem and Boston. The territory administered by the colony included much of present-day central New England, including portions...

during the Great Migration

Great Migration (Puritan)

The Puritan migration to New England was marked in its effects in the two decades from 1620 to 1640, after which it declined sharply for a while. The term Great Migration usually refers to the migration in this period of English settlers, primarily Puritans to Massachusetts and the warm islands of...

decade of the 1630s. Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

, Parliamentary commander during the English Civil War and head of the English Commonwealth (1649–1660), attended Sidney Sussex.

Mathematics

From the time of Isaac NewtonIsaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."...

in the later 17th century until the mid-19th century, the university maintained a strong emphasis on applied mathematics

Applied mathematics

Applied mathematics is a branch of mathematics that concerns itself with mathematical methods that are typically used in science, engineering, business, and industry. Thus, "applied mathematics" is a mathematical science with specialized knowledge...

, particularly mathematical physics. Study of this subject was compulsory for graduation, and students were required to take an exam for the Bachelor of Arts degree, the main first degree at Cambridge in both arts and science subjects. This exam is known as a Tripos

Tripos

The University of Cambridge, England, divides the different kinds of honours bachelor's degree by Tripos , plural Triposes. The word has an obscure etymology, but may be traced to the three-legged stool candidates once used to sit on when taking oral examinations...

. Students awarded first-class honours

British undergraduate degree classification

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading scheme for undergraduate degrees in the United Kingdom...

after completing the mathematics Tripos were named wranglers. The Cambridge Mathematical Tripos

Cambridge Mathematical Tripos

The Mathematical Tripos is the taught mathematics course at the University of Cambridge. It is the oldest Tripos that is examined in Cambridge.-Origin:...

was competitive and helped produce some of the most famous names in British science, including James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell of Glenlair was a Scottish physicist and mathematician. His most prominent achievement was formulating classical electromagnetic theory. This united all previously unrelated observations, experiments and equations of electricity, magnetism and optics into a consistent theory...

, Lord Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin

William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin OM, GCVO, PC, PRS, PRSE, was a mathematical physicist and engineer. At the University of Glasgow he did important work in the mathematical analysis of electricity and formulation of the first and second laws of thermodynamics, and did much to unify the emerging...

, and Lord Rayleigh

John Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh

John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh, OM was an English physicist who, with William Ramsay, discovered the element argon, an achievement for which he earned the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1904...

. However, some famous students, such as G. H. Hardy

G. H. Hardy

Godfrey Harold “G. H.” Hardy FRS was a prominent English mathematician, known for his achievements in number theory and mathematical analysis....

, disliked the system, feeling that people were too interested in accumulating marks in exams and not interested in the subject itself.

Pure mathematics at Cambridge in the 19th century had great achievements but also missed out on substantial developments in French and German mathematics. Pure mathematical research at Cambridge finally reached the highest international standard in the early 20th century, thanks above all to G. H. Hardy

G. H. Hardy

Godfrey Harold “G. H.” Hardy FRS was a prominent English mathematician, known for his achievements in number theory and mathematical analysis....

and his collaborator, J. E. Littlewood. In geometry, W. V. D. Hodge

W. V. D. Hodge

William Vallance Douglas Hodge FRS was a Scottish mathematician, specifically a geometer.His discovery of far-reaching topological relations between algebraic geometry and differential geometry—an area now called Hodge theory and pertaining more generally to Kähler manifolds—has been a major...

brought Cambridge into the international mainstream in the 1930s.

Although diversified in its research and teaching interests, Cambridge today maintains its strength in mathematics. Cambridge alumni have won six Fields Medal

Fields Medal

The Fields Medal, officially known as International Medal for Outstanding Discoveries in Mathematics, is a prize awarded to two, three, or four mathematicians not over 40 years of age at each International Congress of the International Mathematical Union , a meeting that takes place every four...

s and one Abel Prize

Abel Prize

The Abel Prize is an international prize presented annually by the King of Norway to one or more outstanding mathematicians. The prize is named after Norwegian mathematician Niels Henrik Abel . It has often been described as the "mathematician's Nobel prize" and is among the most prestigious...

for mathematics, while individuals representing Cambridge have won four Fields Medals. The University also runs a special

Master of Advanced Study course in mathematics.

Contributions to the advancement of science

Many of the most important scientific discoveries and revolutions were made by Cambridge alumni. These include:- Understanding the scientific methodScientific methodScientific method refers to a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge. To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry must be based on gathering empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of...

, by Francis BaconFrancis BaconFrancis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Albans, KC was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, lawyer, jurist, author and pioneer of the scientific method. He served both as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England... - The laws of motionNewton's laws of motionNewton's laws of motion are three physical laws that form the basis for classical mechanics. They describe the relationship between the forces acting on a body and its motion due to those forces...

and the development of calculusCalculusCalculus is a branch of mathematics focused on limits, functions, derivatives, integrals, and infinite series. This subject constitutes a major part of modern mathematics education. It has two major branches, differential calculus and integral calculus, which are related by the fundamental theorem...

, by Sir Isaac Newton - The development of thermodynamics, by Lord Kelvin

- The discovery of the electron, by J. J. ThomsonJ. J. ThomsonSir Joseph John "J. J." Thomson, OM, FRS was a British physicist and Nobel laureate. He is credited for the discovery of the electron and of isotopes, and the invention of the mass spectrometer...

- The splitting of the atomAtomic nucleusThe nucleus is the very dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom. It was discovered in 1911, as a result of Ernest Rutherford's interpretation of the famous 1909 Rutherford experiment performed by Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, under the direction of Rutherford. The...

, by Ernest RutherfordErnest RutherfordErnest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson OM, FRS was a New Zealand-born British chemist and physicist who became known as the father of nuclear physics...

and of the nucleus by Sir John Cockcroft and Ernest WaltonErnest WaltonErnest Thomas Sinton Walton was an Irish physicist and Nobel laureate for his work with John Cockcroft with "atom-smashing" experiments done at Cambridge University in the early 1930s, and so became the first person in history to artificially split the atom, thus ushering the nuclear age... - The unification of electromagnetism, by James Clerk MaxwellJames Clerk MaxwellJames Clerk Maxwell of Glenlair was a Scottish physicist and mathematician. His most prominent achievement was formulating classical electromagnetic theory. This united all previously unrelated observations, experiments and equations of electricity, magnetism and optics into a consistent theory...

- The discovery of hydrogen, by Henry CavendishHenry CavendishHenry Cavendish FRS was a British scientist noted for his discovery of hydrogen or what he called "inflammable air". He described the density of inflammable air, which formed water on combustion, in a 1766 paper "On Factitious Airs". Antoine Lavoisier later reproduced Cavendish's experiment and...

- Theory of Evolution by natural selection, by Charles DarwinCharles DarwinCharles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

- Mathematical synthesis of Darwinian selection with Mendelian genetics, by Ronald FisherRonald FisherSir Ronald Aylmer Fisher FRS was an English statistician, evolutionary biologist, eugenicist and geneticist. Among other things, Fisher is well known for his contributions to statistics by creating Fisher's exact test and Fisher's equation...

- The Turing machineTuring machineA Turing machine is a theoretical device that manipulates symbols on a strip of tape according to a table of rules. Despite its simplicity, a Turing machine can be adapted to simulate the logic of any computer algorithm, and is particularly useful in explaining the functions of a CPU inside a...

, a basic model for computationTheory of computationIn theoretical computer science, the theory of computation is the branch that deals with whether and how efficiently problems can be solved on a model of computation, using an algorithm...

, by Alan TuringAlan TuringAlan Mathison Turing, OBE, FRS , was an English mathematician, logician, cryptanalyst, and computer scientist. He was highly influential in the development of computer science, providing a formalisation of the concepts of "algorithm" and "computation" with the Turing machine, which played a... - The structure of DNADNADeoxyribonucleic acid is a nucleic acid that contains the genetic instructions used in the development and functioning of all known living organisms . The DNA segments that carry this genetic information are called genes, but other DNA sequences have structural purposes, or are involved in...

, by Rosalind FranklinRosalind FranklinRosalind Elsie Franklin was a British biophysicist and X-ray crystallographer who made critical contributions to the understanding of the fine molecular structures of DNA, RNA, viruses, coal and graphite...

, Francis CrickFrancis CrickFrancis Harry Compton Crick OM FRS was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist, and most noted for being one of two co-discoverers of the structure of the DNA molecule in 1953, together with James D. Watson...

, James D. WatsonJames D. WatsonJames Dewey Watson is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist, best known as one of the co-discoverers of the structure of DNA in 1953 with Francis Crick...

and Maurice WilkinsMaurice WilkinsMaurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins CBE FRS was a New Zealand-born English physicist and molecular biologist, and Nobel Laureate whose research contributed to the scientific understanding of phosphorescence, isotope separation, optical microscopy and X-ray diffraction, and to the development of radar...

, the later three awarded the Nobel Prize.(Rosalind Franklin didn't receive the Nobel Prize as it was not given posthumously) - Pioneering quantum mechanicsQuantum mechanicsQuantum mechanics, also known as quantum physics or quantum theory, is a branch of physics providing a mathematical description of much of the dual particle-like and wave-like behavior and interactions of energy and matter. It departs from classical mechanics primarily at the atomic and subatomic...

, by Paul DiracPaul DiracPaul Adrien Maurice Dirac, OM, FRS was an English theoretical physicist who made fundamental contributions to the early development of both quantum mechanics and quantum electrodynamics...

Women's education

Initially, only male students were enrolled into the university. The first colleges for women were Girton CollegeGirton College, Cambridge

Girton College is one of the 31 constituent colleges of the University of Cambridge. It was England's first residential women's college, established in 1869 by Emily Davies and Barbara Bodichon. The full college status was only received in 1948 and marked the official admittance of women to the...

(founded by Emily Davies

Emily Davies

Sarah Emily Davies was an English feminist, suffragist and a pioneering campaigners fore women's rights to university access. She was born in Southampton, England to an evangelical clergyman and a teacher in 1830, although she spent most of her youth in Gateshead...

) in 1869 and Newnham College

Newnham College, Cambridge

Newnham College is a women-only constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England.The college was founded in 1871 by Henry Sidgwick, and was the second Cambridge college to admit women after Girton College...

in 1872 (founded by Anne Clough

Anne Clough