Christianity in the 16th century

Encyclopedia

Age of Discovery

During the Age of DiscoveryAge of Discovery

The Age of Discovery, also known as the Age of Exploration and the Great Navigations , was a period in history starting in the early 15th century and continuing into the early 17th century during which Europeans engaged in intensive exploration of the world, establishing direct contacts with...

, the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

established a number of Missions

Mission (Christian)

Christian missionary activities often involve sending individuals and groups , to foreign countries and to places in their own homeland. This has frequently involved not only evangelization , but also humanitarian work, especially among the poor and disadvantaged...

in the Americas and other colonies in order to spread Christianity in the New World and to convert the indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of North and South America, their descendants and other ethnic groups who are identified with those peoples. Indigenous peoples are known in Canada as Aboriginal peoples, and in the United States as Native Americans...

. At the same time, missionaries such as Francis Xavier

Francis Xavier

Francis Xavier, born Francisco de Jasso y Azpilicueta was a pioneering Roman Catholic missionary born in the Kingdom of Navarre and co-founder of the Society of Jesus. He was a student of Saint Ignatius of Loyola and one of the first seven Jesuits, dedicated at Montmartre in 1534...

as well as other Jesuits

Society of Jesus

The Society of Jesus is a Catholic male religious order that follows the teachings of the Catholic Church. The members are called Jesuits, and are also known colloquially as "God's Army" and as "The Company," these being references to founder Ignatius of Loyola's military background and a...

, Augustinians

Augustinians

The term Augustinians, named after Saint Augustine of Hippo , applies to two separate and unrelated types of Catholic religious orders:...

, Franciscans and Dominicans

Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers , after the 15th century more commonly known as the Dominican Order or Dominicans, is a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Dominic and approved by Pope Honorius III on 22 December 1216 in France...

were moving into Asia and the Far East. Under the Padroado

Padroado

The Padroado , was an arrangement between the Holy See and the kingdom of Portugal, affirmed by a series of treaties, by which the Vatican delegated to the kings of Spain and Portugal the administration of the local Churches...

treaty (Portuguese: "patronage") with the Holy See, by which the Vatican delegated to the kings the administration of the local Churches, the Portuguese sent missions into Africa, Brasil and Asia. While some of these missions were associated with imperialism and oppression, others (notably Matteo Ricci

Matteo Ricci

Matteo Ricci, SJ was an Italian Jesuit priest, and one of the founding figures of the Jesuit China Mission, as it existed in the 17th-18th centuries. His current title is Servant of God....

's Jesuit China missions

Jesuit China missions

The history of the missions of the Jesuits in China is part of the history of relations between China and the Western world. The missionary efforts and other work of the Society of Jesus, or Jesuits, between the 16th and 17th century played a significant role in continuing the transmission of...

were relatively peaceful and focused on integration rather than cultural imperialism

Cultural imperialism

Cultural imperialism is the domination of one culture over another. Cultural imperialism can take the form of a general attitude or an active, formal and deliberate policy, including military action. Economic or technological factors may also play a role...

.

The expansion of the Catholic

Catholic

The word catholic comes from the Greek phrase , meaning "on the whole," "according to the whole" or "in general", and is a combination of the Greek words meaning "about" and meaning "whole"...

Portuguese Empire

Portuguese Empire

The Portuguese Empire , also known as the Portuguese Overseas Empire or the Portuguese Colonial Empire , was the first global empire in history...

and Spanish Empire

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire comprised territories and colonies administered directly by Spain in Europe, in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was therefore one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs, Spain reached the peak of its world power....

with a significant roled played by the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

led to the Christianization of the indigenous populations of the Americas such as the Aztec

Aztec

The Aztec people were certain ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, a period referred to as the late post-classic period in Mesoamerican chronology.Aztec is the...

s and Incas. Later waves of colonial expansion such as the Scramble for Africa

Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa, also known as the Race for Africa or Partition of Africa was a process of invasion, occupation, colonization and annexation of African territory by European powers during the New Imperialism period, between 1881 and World War I in 1914...

or the struggle for India, by the Dutch

Netherlands

The Netherlands is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, located mainly in North-West Europe and with several islands in the Caribbean. Mainland Netherlands borders the North Sea to the north and west, Belgium to the south, and Germany to the east, and shares maritime borders...

, England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

and Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

led to Christianization of other native populations across the globe such as the American Indians

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of North and South America, their descendants and other ethnic groups who are identified with those peoples. Indigenous peoples are known in Canada as Aboriginal peoples, and in the United States as Native Americans...

, Filipinos

Filipino people

The Filipino people or Filipinos are an Austronesian ethnic group native to the islands of the Philippines. There are about 92 million Filipinos in the Philippines, and about 11 million living outside the Philippines ....

, India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

ns and Africa

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

ns led to the expansion of Christianity eclipsing that of the Roman period and making it a truly global religion.

Protestant Reformation (1521–1579)

The RenaissanceRenaissance

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. The term is also used more loosely to refer to the historical era, but since the changes of the Renaissance were not...

yielded scholars the ability to read the scriptures in their original languages and this in part stimulated the Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

. Martin Luther

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

, a Doctor in Bible at the University of Wittenburg, began to teach that salvation

Salvation

Within religion salvation is the phenomenon of being saved from the undesirable condition of bondage or suffering experienced by the psyche or soul that has arisen as a result of unskillful or immoral actions generically referred to as sins. Salvation may also be called "deliverance" or...

is a gift of God's grace

Sola gratia

Sola gratia is one of the five solas propounded to summarise the Reformers' basic beliefs during the Protestant Reformation; it is a Latin term meaning grace alone...

, attainable only through faith

Sola fide

Sola fide , also historically known as the doctrine of justification by faith alone, is a Christian theological doctrine that distinguishes most Protestant denominations from Catholicism, Eastern Christianity, and some in the Restoration Movement.The doctrine of sola fide or "by faith alone"...

in Jesus, who in humility

Theology of the Cross

The Theology of the Cross is a term coined by the theologian Martin Luther to refer to theology that posits the cross as the only source of knowledge concerning who God is and how God saves...

paid for sin. "This one and firm rock, which we call the doctrine of justification

Justification (theology)

Rising out of the Protestant Reformation, Justification is the chief article of faith describing God's act of declaring or making a sinner righteous through Christ's atoning sacrifice....

," insisted Martin Luther

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

, "is the chief article of the whole Christian doctrine, which comprehends the understanding of all godliness." Along with the doctrine of justification, the Reformation promoted a higher view of the Bible. As Martin Luther said, "The true rule is this: God's Word shall establish articles of faith, and no one else, not even an angel can do so."

. These two ideas in turn promoted the concept of the priesthood of all believers

Priesthood of all believers

The universal priesthood or the priesthood of all believers, as it would come to be known in the present day, is a Christian doctrine believed to be derived from several passages of the New Testament...

. Other important reformers were John Calvin

John Calvin

John Calvin was an influential French theologian and pastor during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of Christian theology later called Calvinism. Originally trained as a humanist lawyer, he broke from the Roman Catholic Church around 1530...

, Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych Zwingli

Ulrich Zwingli was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland. Born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system, he attended the University of Vienna and the University of Basel, a scholarly centre of humanism...

, Philipp Melanchthon

Philipp Melanchthon

Philipp Melanchthon , born Philipp Schwartzerdt, was a German reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lutheran Reformation, and an influential designer of educational systems...

, Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer was a Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg who influenced Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican doctrines and practices. Bucer was originally a member of the Dominican Order, but after meeting and being influenced by Martin Luther in 1518 he arranged for his monastic vows to be annulled...

and the Anabaptist

Anabaptist

Anabaptists are Protestant Christians of the Radical Reformation of 16th-century Europe, and their direct descendants, particularly the Amish, Brethren, Hutterites, and Mennonites....

s. Their theology was modified by successors such as Theodore Beza

Theodore Beza

Theodore Beza was a French Protestant Christian theologian and scholar who played an important role in the Reformation...

, the English Puritans and Francis Turretin

Francis Turretin

Francis Turretin was a Swiss-Italian Protestant theologian.Turretin is especially known as a zealous opponent of the theology of the Academy of Saumur , as an earnest defender of the Calvinistic orthodoxy represented by the Synod of Dort, and as one of the authors of the Helvetic...

.

In the early 16th century, movements were begun by two theologians, Martin Luther

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

and Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych Zwingli

Ulrich Zwingli was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland. Born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system, he attended the University of Vienna and the University of Basel, a scholarly centre of humanism...

, that aimed to reform the Church; these reformers are distinguished from previous ones in that they considered the root of corruptions to be doctrinal (rather than simply a matter of moral weakness or lack of ecclesiastical discipline) and thus they aimed to change contemporary doctrines to accord with what they perceived to be the "true gospel." The word Protestant is derived from the Latin protestatio meaning declaration which refers to the letter of protestation

Protestation at Speyer

On April 19, 1529 six Fürsten and 14 Imperial Free Cities, representing the Protestant minority, petitioned the Reichstag at Speyer against the Reichsacht against Martin Luther, as well as the proscription of his works and teachings, and called for the unhindered spread of the "evangelical" On...

by Lutheran princes against the decision of the Diet of Speyer

Second Diet of Speyer

The Diet of Speyer or the Diet of Spires was a diet of the Holy Roman Empire in 1529 in the Imperial City of Speyer . The diet condemned the results of the Diet of Speyer of 1526 and prohibited future reformation...

in 1529, which reaffirmed the edict of the Diet of Worms

Diet of Worms

The Diet of Worms 1521 was a diet that took place in Worms, Germany, and is most memorable for the Edict of Worms , which addressed Martin Luther and the effects of the Protestant Reformation.It was conducted from 28 January to 25 May 1521, with Emperor Charles V presiding.Other Imperial diets at...

against the Reformation. Since that time, the term has been used in many different senses, but most often as a general term refers to Western Christianity

Western Christianity

Western Christianity is a term used to include the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church and groups historically derivative thereof, including the churches of the Anglican and Protestant traditions, which share common attributes that can be traced back to their medieval heritage...

that is not subject to papal authority. The term "Protestant" was not originally used by Reformation era leaders; instead, they called themselves "evangelical", emphasising the "return to the true gospel (Greek: euangelion)."

The beginning of the Protestant Reformation is generally identified with Martin Luther

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

and the posting of the 95 Theses on the castle church in Wittenberg, Germany. Early protest was against corruptions such as simony

Simony

Simony is the act of paying for sacraments and consequently for holy offices or for positions in the hierarchy of a church, named after Simon Magus , who appears in the Acts of the Apostles 8:9-24...

, episcopal vacancies, and the sale of indulgence

Indulgence

In Catholic theology, an indulgence is the full or partial remission of temporal punishment due for sins which have already been forgiven. The indulgence is granted by the Catholic Church after the sinner has confessed and received absolution...

s. The Protestant position, however, would come to incorporate doctrinal changes such as sola scriptura

Sola scriptura

Sola scriptura is the doctrine that the Bible contains all knowledge necessary for salvation and holiness. Consequently, sola scriptura demands that only those doctrines are to be admitted or confessed that are found directly within or indirectly by using valid logical deduction or valid...

and sola fide

Sola fide

Sola fide , also historically known as the doctrine of justification by faith alone, is a Christian theological doctrine that distinguishes most Protestant denominations from Catholicism, Eastern Christianity, and some in the Restoration Movement.The doctrine of sola fide or "by faith alone"...

. The three most important traditions to emerge directly from the Protestant Reformation were the Lutheran

Lutheranism

Lutheranism is a major branch of Western Christianity that identifies with the theology of Martin Luther, a German reformer. Luther's efforts to reform the theology and practice of the church launched the Protestant Reformation...

, Reformed

Reformed churches

The Reformed churches are a group of Protestant denominations characterized by Calvinist doctrines. They are descended from the Swiss Reformation inaugurated by Huldrych Zwingli but developed more coherently by Martin Bucer, Heinrich Bullinger and especially John Calvin...

(Calvinist, Presbyterian, etc.), and Anglican

Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a tradition within Christianity comprising churches with historical connections to the Church of England or similar beliefs, worship and church structures. The word Anglican originates in ecclesia anglicana, a medieval Latin phrase dating to at least 1246 that means the English...

traditions, though the latter group identifies as both "Reformed" and "Catholic", and some subgroups reject the classification as "Protestant."

The Protestant Reformation may be divided into two distinct but basically simultaneous movements, the Magisterial Reformation

Magisterial Reformation

The Magisterial Reformation is a phrase that "draws attention to the manner in which the Lutheran and Calvinist reformers related to secular authorities, such as princes, magistrates, or city councils", i.e. "the magistracy"...

and the Radical Reformation

Radical Reformation

The Radical Reformation was a 16th century response to what was believed to be both the corruption in the Roman Catholic Church and the expanding Magisterial Protestant movement led by Martin Luther and many others. Beginning in Germany and Switzerland, the Radical Reformation birthed many radical...

. The Magisterial Reformation involved the alliance of certain theological teachers (Latin: magistri) such as Luther, Zwingli, Calvin, Cranmer, etc. with secular magistrates who cooperated in the reformation of Christendom. Radical Reformers, besides forming communities outside state sanction, often employed more extreme doctrinal change, such as the rejection of tenants of the Councils of Nicaea and Chalcedon. Often the division between magisterial and radical reformers was as or more violent than the general Catholic and Protestant hostilities.

The Protestant Reformation spread almost entirely within the confines of Northern Europe, but did not take hold in certain northern areas such as Ireland and parts of Germany. By far the magisterial reformers were more successful and their changes more widespread than the radical reformers. The Catholic response to the Protestant Reformation is known as the Counter Reformation, or Catholic Reformation, which resulted in a reassertion of traditional doctrines and the emergence of new religious orders aimed at both moral reform and new missionary activity. The Counter Reformation reconverted approximately 33% of Northern Europe to Catholicism and initiated missions in South and Central America, Africa, Asia, and even China and Japan. Protestant expansion outside of Europe occurred on a smaller scale through colonisation of North America and areas of Africa.

Protestants generally trace their separation from the Catholic Church to the 16th century. The origin of mainstream Protestantism is sometimes called the Magisterial Reformation because the movement received support from the magistrates, the ruling authorities (as opposed to the Radical Reformation

Radical Reformation

The Radical Reformation was a 16th century response to what was believed to be both the corruption in the Roman Catholic Church and the expanding Magisterial Protestant movement led by Martin Luther and many others. Beginning in Germany and Switzerland, the Radical Reformation birthed many radical...

, which had no state sponsorship). In Germany, a hundred years later, the protests erupted in many places at once, during a time of threatened Islamic Ottoman

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

invasion

Ottoman wars in Europe

The wars of the Ottoman Empire in Europe are also sometimes referred to as the Ottoman Wars or as Turkish Wars, particularly in older, European texts.- Rise :...

¹ which distracted German princes in particular. To some degree, the protest can be explained by the events of the previous two centuries in Europe and particularly in Bohemia.

Zürich

Zurich is the largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is located in central Switzerland at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich...

and Geneva

Geneva

Geneva In the national languages of Switzerland the city is known as Genf , Ginevra and Genevra is the second-most-populous city in Switzerland and is the most populous city of Romandie, the French-speaking part of Switzerland...

. Since the term "magister" also means "teacher", the Magisterial Reformation is also characterized by an emphasis on the authority of a teacher. This is made evident in the prominence of Luther, Calvin, and Zwingli as leaders of the reform movements in their respective areas of ministry. Because of their authority, they were often criticized by Radical Reformers

Radical Reformation

The Radical Reformation was a 16th century response to what was believed to be both the corruption in the Roman Catholic Church and the expanding Magisterial Protestant movement led by Martin Luther and many others. Beginning in Germany and Switzerland, the Radical Reformation birthed many radical...

as being too much like the Roman Popes. For example, Radical Reformer Andreas von Bodenstein Karlstadt referred to the Wittenberg theologians as the "new papists".

Martin Luther and Lutheranism

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

, an Augustinian monk and professor at the university of Wittenberg

Wittenberg

Wittenberg, officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg, is a city in Germany in the Bundesland Saxony-Anhalt, on the river Elbe. It has a population of about 50,000....

, called in 1517 for a reopening of the debate on the sale of indulgence

Indulgence

In Catholic theology, an indulgence is the full or partial remission of temporal punishment due for sins which have already been forgiven. The indulgence is granted by the Catholic Church after the sinner has confessed and received absolution...

s. Luther's dissent marked a sudden outbreak of a new and irresistible force of discontent which had been pushed underground but not resolved. The quick spread of discontent occurred to a large degree because of the printing press

Printing press

A printing press is a device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium , thereby transferring the ink...

and the resulting swift movement of both ideas and documents, including the 95 Theses

95 Theses

The Ninety-Five Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences , commonly known as , was written by Martin Luther, 1517 and is widely regarded as the primary catalyst for the Protestant Reformation...

. Information was also widely disseminated in manuscript form, as well as by cheap prints and woodcuts amongst the poorer sections of society.

Parallel to events in Germany, a movement began in Switzerland under the leadership of Ulrich Zwingli. These two movements quickly agreed on most issues, as the recently introduced printing press

Printing press

A printing press is a device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium , thereby transferring the ink...

spread ideas rapidly from place to place, but some unresolved differences kept them separate. Some followers of Zwingli believed that the Reformation was too conservative, and moved independently toward more radical positions, some of which survive among modern day Anabaptist

Anabaptist

Anabaptists are Protestant Christians of the Radical Reformation of 16th-century Europe, and their direct descendants, particularly the Amish, Brethren, Hutterites, and Mennonites....

s. Other Protestant movements grew up along lines of mysticism or humanism (cf.

Cf.

cf., an abbreviation for the Latin word confer , literally meaning "bring together", is used to refer to other material or ideas which may provide similar or different information or arguments. It is mainly used in scholarly contexts, such as in academic or legal texts...

Erasmus), sometimes breaking from Rome or from the Protestants, or forming outside of the churches.

After this first stage of the Reformation, following the excommunication

Excommunication

Excommunication is a religious censure used to deprive, suspend or limit membership in a religious community. The word means putting [someone] out of communion. In some religions, excommunication includes spiritual condemnation of the member or group...

of Luther and condemnation of the Reformation by the Pope, the work and writings of John Calvin

John Calvin

John Calvin was an influential French theologian and pastor during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of Christian theology later called Calvinism. Originally trained as a humanist lawyer, he broke from the Roman Catholic Church around 1530...

were influential in establishing a loose consensus among various groups in Switzerland, Scotland

Scotland

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Occupying the northern third of the island of Great Britain, it shares a border with England to the south and is bounded by the North Sea to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the north and west, and the North Channel and Irish Sea to the...

, Hungary, Germany and elsewhere.

95 Theses

The Ninety-Five Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences , commonly known as , was written by Martin Luther, 1517 and is widely regarded as the primary catalyst for the Protestant Reformation...

, or points to be debated, concerning the illicitness of selling indulgences. Luther had a particular disdain for Aristotelian philosophy, and as he began developing his own theology, he increasingly came into conflict with Thomistic

Thomism

Thomism is the philosophical school that arose as a legacy of the work and thought of St. Thomas Aquinas, philosopher, theologian, and Doctor of the Church. In philosophy, his commentaries on Aristotle are his most lasting contribution...

scholars, most notably Cardinal Cajetan

Thomas Cajetan

Thomas Cajetan , also known as Gaetanus, commonly Tommaso de Vio , was an Italian cardinal. He is perhaps best known among Protestants for his opposition to the teachings of Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation while he was the Pope's Legate in Wittenberg, and perhaps best known among...

. Soon, Luther had begun to develop his theology of justification

Justification (theology)

Rising out of the Protestant Reformation, Justification is the chief article of faith describing God's act of declaring or making a sinner righteous through Christ's atoning sacrifice....

, or process by which one is "made right" (righteous) in the eyes of God. In Catholic theology, one is made righteous by a progressive infusion of grace accepted through faith and cooperated with through good works. Luther's doctrine of justification differed from Catholic theology in that justification rather meant "the declaring of one to be righteous", where God imputes the merits of Christ upon one who remains without inherent merit. In this process, good works are more of an unessential byproduct that contribute nothing to one's own state of righteousness. Conflict between Luther and leading theologians lead to his gradual rejection of authority of the Church hierarchy. In 1520, he was condemned for heresy by the papal bull Exsurge Domine

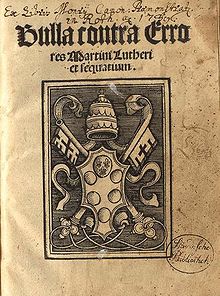

Exsurge Domine

220px|thumb|Title page of first printed edition of Exsurge DomineExsurge Domine is a papal bull issued on 15 June 1520 by Pope Leo X in response to the teachings of Martin Luther in his 95 theses and subsequent writings which opposed the views of the papacy...

, which he burned at Wittenberg along with books of canon law

Canon law

Canon law is the body of laws & regulations made or adopted by ecclesiastical authority, for the government of the Christian organization and its members. It is the internal ecclesiastical law governing the Catholic Church , the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox churches, and the Anglican Communion of...

.

Lutheranism

Lutheranism

Lutheranism is a major branch of Western Christianity that identifies with the theology of Martin Luther, a German reformer. Luther's efforts to reform the theology and practice of the church launched the Protestant Reformation...

is a major branch of Western Christianity

Western Christianity

Western Christianity is a term used to include the Latin Rite of the Catholic Church and groups historically derivative thereof, including the churches of the Anglican and Protestant traditions, which share common attributes that can be traced back to their medieval heritage...

that identifies with the teachings of the 16th-century German

Germans

The Germans are a Germanic ethnic group native to Central Europe. The English term Germans has referred to the German-speaking population of the Holy Roman Empire since the Late Middle Ages....

reformer Martin Luther

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

. Luther's efforts to reform the theology and practice of the church launched The Reformation. As a result of the reactions of his contemporaries, Christianity was divided.

Luther's insights are generally held to have been a major foundation of the Protestant movement

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

. The relationship between Lutheranism and the Protestant tradition is, however, ambiguous: some Lutherans consider Lutheranism to be outside the Protestant tradition, while some see it as part of this tradition.

Humanism to Protestantism

The frustrated reformism of the humanists, ushered in by the RenaissanceRenaissance

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. The term is also used more loosely to refer to the historical era, but since the changes of the Renaissance were not...

, contributed to a growing impatience among reformers. Erasmus and later figures like Martin Luther and Zwingli would emerge from this debate and eventually contribute to another major schism of Christendom. The crisis of theology beginning with William of Ockham

William of Ockham

William of Ockham was an English Franciscan friar and scholastic philosopher, who is believed to have been born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey. He is considered to be one of the major figures of medieval thought and was at the centre of the major intellectual and political controversies of...

in the 14th century was occurring in conjunction with the new burgher

Bourgeoisie

In sociology and political science, bourgeoisie describes a range of groups across history. In the Western world, between the late 18th century and the present day, the bourgeoisie is a social class "characterized by their ownership of capital and their related culture." A member of the...

discontent. Since the breakdown of the philosophical

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

foundations of scholasticism

Scholasticism

Scholasticism is a method of critical thought which dominated teaching by the academics of medieval universities in Europe from about 1100–1500, and a program of employing that method in articulating and defending orthodoxy in an increasingly pluralistic context...

, the new nominalism

Nominalism

Nominalism is a metaphysical view in philosophy according to which general or abstract terms and predicates exist, while universals or abstract objects, which are sometimes thought to correspond to these terms, do not exist. Thus, there are at least two main versions of nominalism...

did not bode well for an institutional church legitimized as an intermediary between man and God. New thinking favored the notion that no religious doctrine

Doctrine

Doctrine is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the body of teachings in a branch of knowledge or belief system...

can be supported by philosophical arguments, eroding the old alliance between reason

Reason

Reason is a term that refers to the capacity human beings have to make sense of things, to establish and verify facts, and to change or justify practices, institutions, and beliefs. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, language, ...

and faith

Faith

Faith is confidence or trust in a person or thing, or a belief that is not based on proof. In religion, faith is a belief in a transcendent reality, a religious teacher, a set of teachings or a Supreme Being. Generally speaking, it is offered as a means by which the truth of the proposition,...

of the medieval period laid out by Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, O.P. , also Thomas of Aquin or Aquino, was an Italian Dominican priest of the Catholic Church, and an immensely influential philosopher and theologian in the tradition of scholasticism, known as Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Communis, or Doctor Universalis...

.

Humanism

Humanism is an approach in study, philosophy, world view or practice that focuses on human values and concerns. In philosophy and social science, humanism is a perspective which affirms some notion of human nature, and is contrasted with anti-humanism....

, devotionalism, (see for example, the Brothers of the Common Life and Jan Standonck

Jan Standonck

Jan Standonck was a Dutch priest, Scholastic, and reformer.He was part of the great movement for reform in the 15th century French church. His approach was to reform the recruitment and education of the clergy, along very ascetic lines, heavily influenced by the hermit saint Francis of Paola...

) and the observatine tradition. In Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, "the modern way" or devotionalism caught on in the universities, requiring a redefinition of God, who was no longer a rational governing principle but an arbitrary, unknowable will that cannot be limited. God was now a ruler, and religion would be more fervent and emotional. Thus, the ensuing revival of Augustinian theology, stating that man cannot be saved by his own efforts but only by the grace of God, would erode the legitimacy of the rigid institutions of the church meant to provide a channel for man to do good works and get into heaven

Heaven

Heaven, the Heavens or Seven Heavens, is a common religious cosmological or metaphysical term for the physical or transcendent place from which heavenly beings originate, are enthroned or inhabit...

. Humanism, however, was more of an educational reform movement with origins in the Renaissance

Renaissance

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. The term is also used more loosely to refer to the historical era, but since the changes of the Renaissance were not...

's revival of classical learning

Classical education movement

The Classical education movement advocates a form of education based in the traditions of Western culture, with a particular focus on education as understood and taught in the Middle Ages. The curricula and pedagogy of classical education was first developed during the Middle Ages by Martianus...

and thought. A revolt against Aristotelian

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

logic, it placed great emphasis on reforming individuals through eloquence as opposed to reason. The European Renaissance laid the foundation for the Northern humanists in its reinforcement of the traditional use of Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

as the great unifying cultural language.

The polarization of the scholarly community in Germany over the Reuchlin (1455–1522) affair, attacked by the elite clergy for his study of Hebrew

Biblical Hebrew language

Biblical Hebrew , also called Classical Hebrew , is the archaic form of the Hebrew language, a Canaanite Semitic language spoken in the area known as Canaan between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. Biblical Hebrew is attested from about the 10th century BCE, and persisted through...

and Jewish texts, brought Luther fully in line with the humanist educational reforms who favored academic freedom

Academic freedom

Academic freedom is the belief that the freedom of inquiry by students and faculty members is essential to the mission of the academy, and that scholars should have freedom to teach or communicate ideas or facts without being targeted for repression, job loss, or imprisonment.Academic freedom is a...

. At the same time, the impact of the Renaissance would soon backfire against traditional Catholicism, ushering in an age of reform and a repudiation of much of medieval Latin tradition. Led by Erasmus, the humanists condemned various forms of corruption within the Church, forms of corruption that might not have been any more prevalent than during the medieval zenith of the church. Erasmus held that true religion was a matter of inward devotion rather than outward symbols of ceremony and ritual. Going back to ancient texts, scriptures, from this viewpoint the greatest culmination of the ancient tradition, are the guides to life. Favoring moral

Morality

Morality is the differentiation among intentions, decisions, and actions between those that are good and bad . A moral code is a system of morality and a moral is any one practice or teaching within a moral code...

reforms and de-emphasizing didactic ritual, Erasmus laid the groundwork for Luther.

Humanism's intellectual anti-clericalism

Anti-clericalism

Anti-clericalism is a historical movement that opposes religious institutional power and influence, real or alleged, in all aspects of public and political life, and the involvement of religion in the everyday life of the citizen...

would profoundly influence Luther. The increasingly well-educated middle

Middle class

The middle class is any class of people in the middle of a societal hierarchy. In Weberian socio-economic terms, the middle class is the broad group of people in contemporary society who fall socio-economically between the working class and upper class....

sectors of Northern Germany, namely the educated community and city dwellers would turn to Luther's rethinking of religion to conceptualize their discontent according to the cultural medium of the era. The great rise of the burghers, the desire to run their new businesses free of institutional barriers or outmoded cultural practices, contributed to the appeal of humanist individualism

Individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, or social outlook that stresses "the moral worth of the individual". Individualists promote the exercise of one's goals and desires and so value independence and self-reliance while opposing most external interference upon one's own...

. To many, papal

Pope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

institutions were rigid, especially regarding their views on just price and usury

Usury

Usury Originally, when the charging of interest was still banned by Christian churches, usury simply meant the charging of interest at any rate . In countries where the charging of interest became acceptable, the term came to be used for interest above the rate allowed by law...

. In the North, burghers and monarchs were united in their frustration for not paying any tax

Tax

To tax is to impose a financial charge or other levy upon a taxpayer by a state or the functional equivalent of a state such that failure to pay is punishable by law. Taxes are also imposed by many subnational entities...

es to the nation, but collecting taxes from subjects

Citizenship

Citizenship is the state of being a citizen of a particular social, political, national, or human resource community. Citizenship status, under social contract theory, carries with it both rights and responsibilities...

and sending the revenues disproportionately to the Pope in Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

.

These trends heightened demands for significant reform and revitalization along with anticlericalism. New thinkers began noticing the divide between the priests and the flock. The clergy, for instance, were not always well-educated. Parish priests often did not know Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

and rural parishes often did not have great opportunities for theological education for many at the time. Due to its large landholdings and institutional rigidity, a rigidity to which the excessively large ranks of the clergy contributed, many bishop

Bishop

A bishop is an ordained or consecrated member of the Christian clergy who is generally entrusted with a position of authority and oversight. Within the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox Churches, in the Assyrian Church of the East, in the Independent Catholic Churches, and in the...

s studied law

Law

Law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social institutions to govern behavior, wherever possible. It shapes politics, economics and society in numerous ways and serves as a social mediator of relations between people. Contract law regulates everything from buying a bus...

, not theology, being relegated to the role of property managers trained in administration. While priests emphasized works of religiosity, the respectability of the church began diminishing, especially among well educated urbanites, and especially considering the recent strings of political humiliation, such as the apprehension of Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII

Pope Boniface VIII , born Benedetto Gaetani, was Pope of the Catholic Church from 1294 to 1303. Today, Boniface VIII is probably best remembered for his feuds with Dante, who placed him in the Eighth circle of Hell in his Divina Commedia, among the Simonists.- Biography :Gaetani was born in 1235 in...

by Philip IV of France

Philip IV of France

Philip the Fair was, as Philip IV, King of France from 1285 until his death. He was the husband of Joan I of Navarre, by virtue of which he was, as Philip I, King of Navarre and Count of Champagne from 1284 to 1305.-Youth:A member of the House of Capet, Philip was born at the Palace of...

, the "Babylonian Captivity", the Great Schism, and the failure of Conciliar reformism. In a sense, the campaign by Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X , born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, was the Pope from 1513 to his death in 1521. He was the last non-priest to be elected Pope. He is known for granting indulgences for those who donated to reconstruct St. Peter's Basilica and his challenging of Martin Luther's 95 Theses...

to raise funds to rebuild St. Peter's Basilica was too much of an excess by the secular Renaissance

Renaissance

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. The term is also used more loosely to refer to the historical era, but since the changes of the Renaissance were not...

church, prompting high-pressure indulgences that rendered the clergy establishments even more disliked in the cities.

Luther borrowed from the humanists the sense of individualism, that each man can be his own priest (an attitude likely to find popular support considering the rapid rise of an educated urban middle class in the North), and that the only true authority is the Bible

Bible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

, echoing the reformist zeal of the Conciliar movement and opening up the debate once again on limiting the authority of the Pope. While his ideas called for the sharp redefinition of the dividing lines between the laity

Laity

In religious organizations, the laity comprises all people who are not in the clergy. A person who is a member of a religious order who is not ordained legitimate clergy is considered as a member of the laity, even though they are members of a religious order .In the past in Christian cultures, the...

and the clergy, his ideas were still, by this point, reformist in nature. Luther's contention that the human will was incapable of following good, however, resulted in his rift with Erasmus finally distinguishing Lutheran reformism from humanism

Humanism

Humanism is an approach in study, philosophy, world view or practice that focuses on human values and concerns. In philosophy and social science, humanism is a perspective which affirms some notion of human nature, and is contrasted with anti-humanism....

.

Lutheranism adopted by the German princes

Luther affirmed a theology of the EucharistEucharist

The Eucharist , also called Holy Communion, the Sacrament of the Altar, the Blessed Sacrament, the Lord's Supper, and other names, is a Christian sacrament or ordinance...

called Real Presence

Real Presence

Real Presence is a term used in various Christian traditions to express belief that in the Eucharist, Jesus Christ is really present in what was previously just bread and wine, and not merely present in symbol, a figure of speech , or by his power .Not all Christian traditions accept this dogma...

, a doctrine of the presence of Christ in the Eucharist which affirms the real presence yet upholding that the bread and wine are not "changed" into the body and blood; rather the divine elements adhere "in, with, and under" the earthly elements. He took this understanding of Christ's presence in the Eucharist to be more harmonious with the Church's teaching on the Incarnation. Just as Christ is the union of the fully human and the fully divine (cf. Council of Chalcedon) so to the Eucharist is a union of Bread and Body, Wine and Blood. According to the doctrine of real presence, the substances of the body and the blood of Christ and of the bread and the wine were held to coexist together in the consecrated Host during the communion service. While Luther seemed to maintain the perpetual consecration of the elements, other Lutherans argued that any consecrated bread or wine left over would revert to its former state the moment the service ended. Most Lutherans accept the latter.

Luther, along with his colleague Philipp Melanchthon

Philipp Melanchthon

Philipp Melanchthon , born Philipp Schwartzerdt, was a German reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lutheran Reformation, and an influential designer of educational systems...

, emphasized this point in his plea for the Reformation at the Reichstag

Reichstag (Holy Roman Empire)

The Imperial Diet was the Diet, or general assembly, of the Imperial Estates of the Holy Roman Empire.During the period of the Empire, which lasted formally until 1806, the Diet was not a parliament in today's sense; instead, it was an assembly of the various estates of the realm...

in 1529 amid charges of heresy

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

. But the changes he proposed were of such a fundamental nature that by their own logic they would automatically overthrow the old order; neither the Emperor nor the Church could possibly accept them, as Luther well knew. As was only to be expected, the edict by the Diet of Worms

Diet of Worms

The Diet of Worms 1521 was a diet that took place in Worms, Germany, and is most memorable for the Edict of Worms , which addressed Martin Luther and the effects of the Protestant Reformation.It was conducted from 28 January to 25 May 1521, with Emperor Charles V presiding.Other Imperial diets at...

(1521) prohibited all innovations. Meanwhile, in these efforts to retain the guise of a Catholic reformer as opposed to a heretical revolutionary, and to appeal to German princes with his religious condemnation of the peasant revolts backed up by the Doctrine of the Two Kingdoms

Doctrine of the two kingdoms

Martin Luther's doctrine of the two kingdoms of God teaches that God is the ruler of the whole world and that he rules in two ways....

, Luther's growing conservatism would provoke more radical reformers.

At a religious conference with the Zwinglians in 1529, Melanchthon joined with Luther in opposing a union with Zwingli. There would finally be a schism in the reform movement due to Luther's belief in real presence

Real Presence

Real Presence is a term used in various Christian traditions to express belief that in the Eucharist, Jesus Christ is really present in what was previously just bread and wine, and not merely present in symbol, a figure of speech , or by his power .Not all Christian traditions accept this dogma...

—the real (as opposed to symbolic) presence of Christ at the Eucharist. His original intention was not schism, but with the Reichstag

Reichstag (Holy Roman Empire)

The Imperial Diet was the Diet, or general assembly, of the Imperial Estates of the Holy Roman Empire.During the period of the Empire, which lasted formally until 1806, the Diet was not a parliament in today's sense; instead, it was an assembly of the various estates of the realm...

of Augsburg (1530) and its rejection of the Lutheran "Augsburg Confession", a separate Lutheran church finally emerged. In a sense, Luther would take theology further in its deviation from established Catholic dogma, forcing a rift between the humanist Erasmus and Luther. Similarly, Zwingli would further repudiate ritualism, and break with the increasingly conservative Luther.

Usury

Usury Originally, when the charging of interest was still banned by Christian churches, usury simply meant the charging of interest at any rate . In countries where the charging of interest became acceptable, the term came to be used for interest above the rate allowed by law...

. In the North, burghers and monarchs were united in their frustration for not paying any taxes to the nation, but collecting taxes from subjects and sending the revenues disproportionately to Italy. In northern Europe, Luther appealed to the growing national consciousness of the German states because he denounced the Pope for involvement in politics as well as religion. Moreover, he backed the nobility, which was now justified to crush the Great Peasant Revolt of 1525 and to confiscate church property by Luther's Doctrine of the Two Kingdoms

Doctrine of the two kingdoms

Martin Luther's doctrine of the two kingdoms of God teaches that God is the ruler of the whole world and that he rules in two ways....

. This explains the attraction of some territorial princes to Lutheranism, especially its Doctrine of the Two Kingdoms. However, the Elector of Brandenburg, Joachim I, blamed Lutheranism for the revolt and so did others. In Brandenburg, it was only under his successor Joachim II that Lutheranism was established, and the old religion was not formally extinct in Brandenburg until the death of the last Catholic bishop there, Georg von Blumenthal, who was Bishop of Lebus and sovereign Prince-Bishop of Ratzeburg.

With the church subordinate to and the agent of civil authority and peasant rebellions condemned on strict religious terms, Lutheranism and German nationalist sentiment were ideally suited to coincide.

Though Charles V

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V was ruler of the Holy Roman Empire from 1519 and, as Charles I, of the Spanish Empire from 1516 until his voluntary retirement and abdication in favor of his younger brother Ferdinand I and his son Philip II in 1556.As...

fought the Reformation, it is no coincidence either that the reign of his nationalistic predecessor Maximilian I

Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor

Maximilian I , the son of Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor and Eleanor of Portugal, was King of the Romans from 1486 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1493 until his death, though he was never in fact crowned by the Pope, the journey to Rome always being too risky...

saw the beginning of the movement. While the centralized states of western Europe had reached accords with the Vatican permitting them to draw on the rich property of the church for government expenditures, enabling them to form state churches that were greatly autonomous of Rome, similar moves on behalf of the Reich were unsuccessful so long as princes and prince bishops fought reforms to drop the pretension of the secular universal empire.

Germany

Germans

The Germans are a Germanic ethnic group native to Central Europe. The English term Germans has referred to the German-speaking population of the Holy Roman Empire since the Late Middle Ages....

monk

Monk

A monk is a person who practices religious asceticism, living either alone or with any number of monks, while always maintaining some degree of physical separation from those not sharing the same purpose...

, theologian

Theology

Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

, university professor, priest, father of Protestantism

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

, and church reformer

Protestant Reformers

Protestant Reformers were those theologians, churchmen, and statesmen whose careers, works, and actions brought about the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century...

whose ideas started the Protestant Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

.

Luther taught that salvation is a free gift of God and received only through true faith

Faith

Faith is confidence or trust in a person or thing, or a belief that is not based on proof. In religion, faith is a belief in a transcendent reality, a religious teacher, a set of teachings or a Supreme Being. Generally speaking, it is offered as a means by which the truth of the proposition,...

in Jesus

Jesus

Jesus of Nazareth , commonly referred to as Jesus Christ or simply as Jesus or Christ, is the central figure of Christianity...

as redeemer from sin. His theology

Theology of Martin Luther

The theology of Martin Luther was instrumental in influencing the Protestant Reformation, specifically topics dealing with Justification by Faith, the relationship between the Law and the Gospel , and various other theological ideas. Although Luther never wrote a "systematic theology" or a...

challenged the authority

Authority

The word Authority is derived mainly from the Latin word auctoritas, meaning invention, advice, opinion, influence, or command. In English, the word 'authority' can be used to mean power given by the state or by academic knowledge of an area .-Authority in Philosophy:In...

of the papacy

Pope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

by adducing the Bible

Bible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

as the only infallible source of Christian

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

doctrine

Doctrine

Doctrine is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the body of teachings in a branch of knowledge or belief system...

and countering "sacerdotalism

Sacerdotalism

Sacerdotalism is the idea that a propitiatory sacrifice for sin must be offered by the intervention of an order of men separated to the priesthood...

" in the doctrine that all baptized

Baptism

In Christianity, baptism is for the majority the rite of admission , almost invariably with the use of water, into the Christian Church generally and also membership of a particular church tradition...

Christians are a universal priesthood

Priesthood of all believers

The universal priesthood or the priesthood of all believers, as it would come to be known in the present day, is a Christian doctrine believed to be derived from several passages of the New Testament...

.

Luther's refusal to retract his writings in confrontation with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V was ruler of the Holy Roman Empire from 1519 and, as Charles I, of the Spanish Empire from 1516 until his voluntary retirement and abdication in favor of his younger brother Ferdinand I and his son Philip II in 1556.As...

at the Diet of Worms

Diet of Worms

The Diet of Worms 1521 was a diet that took place in Worms, Germany, and is most memorable for the Edict of Worms , which addressed Martin Luther and the effects of the Protestant Reformation.It was conducted from 28 January to 25 May 1521, with Emperor Charles V presiding.Other Imperial diets at...

in 1521 resulted in his excommunication

Excommunication

Excommunication is a religious censure used to deprive, suspend or limit membership in a religious community. The word means putting [someone] out of communion. In some religions, excommunication includes spiritual condemnation of the member or group...

by Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X , born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, was the Pope from 1513 to his death in 1521. He was the last non-priest to be elected Pope. He is known for granting indulgences for those who donated to reconstruct St. Peter's Basilica and his challenging of Martin Luther's 95 Theses...

and declaration as an outlaw

Outlaw

In historical legal systems, an outlaw is declared as outside the protection of the law. In pre-modern societies, this takes the burden of active prosecution of a criminal from the authorities. Instead, the criminal is withdrawn all legal protection, so that anyone is legally empowered to persecute...

. His translation of the Bible

Luther Bible

The Luther Bible is a German Bible translation by Martin Luther, first printed with both testaments in 1534. This translation became a force in shaping the Modern High German language. The project absorbed Luther's later years. The new translation was very widely disseminated thanks to the printing...

into the language of the people made the Scriptures more accessible, causing a tremendous impact on the church and on German culture. It fostered the development of a standard version of the German language

German language

German is a West Germanic language, related to and classified alongside English and Dutch. With an estimated 90 – 98 million native speakers, German is one of the world's major languages and is the most widely-spoken first language in the European Union....

, added several principles to the art of translation, and influenced the translation of the King James Bible. His hymn

Hymn

A hymn is a type of song, usually religious, specifically written for the purpose of praise, adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification...

s inspired the development of congregational singing within Christianity. His marriage to Katharina von Bora

Katharina von Bora

Katharina von Bora, referred to as "die Lutherin", was the wife of Martin Luther, Germanleader of the Protestant Reformation. Beyond what is found in the writings of Luther and some of his contemporaries, little is known about her...

set a model for the practice of clerical marriage

Clerical marriage

Clerical marriage is the practice of allowing clergy to marry. Churches such as the Eastern Orthodox and the Oriental Orthodox exclude this practice for their priests, while accepting already married men for ordination to priesthood...

within Protestantism.

Johann Tetzel

Johann Tetzel was a German Dominican preacher known for selling indulgences.-Life:Tetzel was born in Pirna, Saxony, and studied theology and philosophy at the university of his native city...

, a Dominican friar and papal commissioner for indulgences, was sent to Germany by the Roman Catholic Church to sell indulgences to raise money to rebuild St Peter's Basilica in Rome. Roman Catholic theology stated that faith alone, whether fiduciary or dogmatic, cannot justify man; and that only such faith as is active in charity and good works (fides caritate formata) can justify man. These good works could be obtained by donating money to the church.

On 31 October 1517, Luther wrote to Albrecht, Archbishop of Mainz and Magdeburg, protesting the sale of indulgences. He enclosed in his letter a copy of his "Disputation of Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences," which came to be known as The 95 Theses.

Luther objected to a saying attributed to Johann Tetzel that "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs," insisting that, since forgiveness was God's alone to grant, those who claimed that indulgences absolved buyers from all punishments and granted them salvation were in error. Christians, he said, must not slacken in following Christ on account of such false assurances.

Philipp Melanchthon

Philipp Melanchthon , born Philipp Schwartzerdt, was a German reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lutheran Reformation, and an influential designer of educational systems...

, writing in 1546, Luther nailed a copy of the 95 Theses

95 Theses

The Ninety-Five Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences , commonly known as , was written by Martin Luther, 1517 and is widely regarded as the primary catalyst for the Protestant Reformation...

to the door of the Castle Church

All Saints' Church, Wittenberg

All Saints' Church, commonly referred to as Schlosskirche, meaning "Castle Church" — to distinguish it from the "town church", the Stadtkirche of St. Mary — and sometimes known as the Reformation Memorial Church, is a Lutheran church in Lutherstadt Wittenberg, Germany...

in Wittenberg

Wittenberg

Wittenberg, officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg, is a city in Germany in the Bundesland Saxony-Anhalt, on the river Elbe. It has a population of about 50,000....

that same day — church doors acting as the bulletin boards of his time — an event now seen as sparking the Protestant Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

, and celebrated each year on 31 October as Reformation Day

Reformation Day

Reformation Day is a religious holiday celebrated on October 31 in remembrance of the Reformation, particularly by Lutheran and some Reformed church communities...

. The 95 Theses

95 Theses

The Ninety-Five Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences , commonly known as , was written by Martin Luther, 1517 and is widely regarded as the primary catalyst for the Protestant Reformation...

were quickly translated from Latin into German, printed, and widely copied, making the controversy one of the first in history to be aided by the printing press

Printing press

A printing press is a device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium , thereby transferring the ink...

. Within two weeks, the theses had spread throughout Germany; within two months throughout Europe. In contrast to the speed with which the theses were distributed, the response of the papacy was painstakingly slow. After three years of debate and negotiations involving Luther, government, and church officials, on 15 June 1520, the Pope warned Luther with the papal bull

Papal bull

A Papal bull is a particular type of letters patent or charter issued by a Pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the bulla that was appended to the end in order to authenticate it....

(edict) Exsurge Domine

Exsurge Domine

220px|thumb|Title page of first printed edition of Exsurge DomineExsurge Domine is a papal bull issued on 15 June 1520 by Pope Leo X in response to the teachings of Martin Luther in his 95 theses and subsequent writings which opposed the views of the papacy...

that he risked excommunication

Excommunication

Excommunication is a religious censure used to deprive, suspend or limit membership in a religious community. The word means putting [someone] out of communion. In some religions, excommunication includes spiritual condemnation of the member or group...

unless he recanted 41 sentences drawn from his writings, including the 95 Theses

95 Theses

The Ninety-Five Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences , commonly known as , was written by Martin Luther, 1517 and is widely regarded as the primary catalyst for the Protestant Reformation...

, within 60 days.

That autumn, Johann Eck

Johann Eck

Dr. Johann Maier von Eck was a German Scholastic theologian and defender of Catholicism during the Protestant Reformation. It was Eck who argued that the beliefs of Martin Luther and Jan Hus were similar.-Life:...

proclaimed the bull in Meissen and other towns. Karl von Miltitz

Karl von Miltitz

Karl von Miltitz was a papal nuncio and a Mainz Cathedral canon.-Biography:He was born in Rabenau near Meißen and Dresden, his family stemming from the lesser Saxon nobility. He studied at Mainz, Trier, Cologne , and Bologna , but his deficient Latin reveals that he was not especially learned...

, a papal nuncio

Nuncio

Nuncio is an ecclesiastical diplomatic title, derived from the ancient Latin word, Nuntius, meaning "envoy." This article addresses this title as well as derived similar titles, all within the structure of the Roman Catholic Church...

, attempted to broker a solution, but Luther, who had sent the Pope a copy of his concilatory On the Freedom of a Christian (which the Pope refused to read) in October, publicly set fire to the bull and decretal

Decretal

Decretals is the name that is given in Canon law to those letters of the pope which formulate decisions in ecclesiastical law.They are generally given in answer to consultations, but are sometimes due to the initiative of the popes...

s at Wittenberg on 10 December 1520, an act he defended in Why the Pope and his Recent Book are Burned and Assertions Concerning All Articles.

As a consequence, Luther was excommunicated by Leo X

Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X , born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, was the Pope from 1513 to his death in 1521. He was the last non-priest to be elected Pope. He is known for granting indulgences for those who donated to reconstruct St. Peter's Basilica and his challenging of Martin Luther's 95 Theses...

on 3 January 1521, in the bull Decet Romanum Pontificem

Decet Romanum Pontificem

Decet Romanum Pontificem is the papal bull excommunicating Martin Luther, bearing the title of the first three Latin words of the text. It was issued on January 3, 1521, by Pope Leo X to effect the excommunication threatened in his earlier papal bull Exsurge Domine since Luther failed to recant...

.

The start of the Reformation

Johann Tetzel

Johann Tetzel was a German Dominican preacher known for selling indulgences.-Life:Tetzel was born in Pirna, Saxony, and studied theology and philosophy at the university of his native city...

, a Dominican friar and papal commissioner for indulgences, was sent to Germany by the Roman Catholic Church to sell indulgences to raise money to rebuild St Peter's Basilica in Rome. Roman Catholic theology stated that faith alone, whether fiduciary or dogmatic, cannot justify man; and that only such faith as is active in charity and good works (fides caritate formata) can justify man. These good works could be obtained by donating money to the church.

On 31 October 1517, Luther wrote to Albrecht, Archbishop of Mainz and Magdeburg, protesting the sale of indulgences. He enclosed in his letter a copy of his "Disputation of Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences," which came to be known as The 95 Theses. Hans Hillerbrand writes that Luther had no intention of confronting the church, but saw his disputation as a scholarly objection to church practices, and the tone of the writing is accordingly "searching, rather than doctrinaire." Hillerbrand writes that there is nevertheless an undercurrent of challenge in several of the theses, particularly in Thesis 86, which asks: "Why does the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with the money of poor believers rather than with his own money?"

The primacy of the Roman Pontiff was again challenged in 1517 when Martin Luther

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

began preaching against several practices in the Catholic Church, including some itinerant friars' abuses involving indulgences. When Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X , born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, was the Pope from 1513 to his death in 1521. He was the last non-priest to be elected Pope. He is known for granting indulgences for those who donated to reconstruct St. Peter's Basilica and his challenging of Martin Luther's 95 Theses...