Philipp Melanchthon

Encyclopedia

Philipp Melanchthon born Philipp Schwartzerdt, was a German reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther

, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation

, intellectual leader of the Lutheran Reformation, and an influential designer of educational systems. He stands next to Luther and Calvin

as a reformer, theologian, and molder of Protestantism. As much as Luther, he is the primary founder of Lutheranism

. They both denounced what they claimed was the exaggerated cult of the saints, justification by works, and the coercion of the conscience in the sacrament of penance that nevertheless could not offer certainty of salvation.

Melanchthon made the distinction between law and gospel the central formula for Lutheran evangelical insight. By the "law" he meant God's requirements both in Old and New Testament; the "gospel" meant the free gift of grace through faith in Jesus Christ.

, near Karlsruhe

, where his father Georg Schwarzerdt was armorer to Philip, Count Palatine of the Rhine. His birthplace was demolished in 1689 and the town's Melanchthonhaus

built on its site in 1897.

In 1507 he was sent to the Latin school at Pforzheim

, where the rector, Georg Simler of Wimpfen, introduced him to the Latin and Greek poets and Aristotle

. He was influenced by his great-uncle Johann Reuchlin

, brother of his maternal grandmother, a representative humanist

. It was Reuchlin who suggested the change from Schwarzerdt (literally Black-earth), into the Greek equivalent Melanchthon (Μελάγχθων).

Still young, he entered in 1509 the University of Heidelberg where he studied philosophy

, rhetoric

, and astronomy

/astrology

, and was known as a good Greek scholar. On being refused the degree of master in 1512 on account of his youth, he went to Tübingen, where he continued humanistic studies, but also worked on jurisprudence

, mathematics

, and medicine

. While there, he was taught the technical aspects of astrology by Johannes Stöffler

.

Having taken the degree of master in 1516, he began to study theology

. Under the influence of men like Reuchlin and Erasmus he became convinced that true Christianity

was something different from scholastic theology

as it was taught at the university. He became conventor (repentant) in the contubernium and instructed younger scholars. He also lectured on oratory, on Virgil

and Livy

.

His first publications were an edition of Terence

(1516) and his Greek grammar (1518), but he had written previously the preface to the Epistolae clarorum virorum of Reuchlin (1514).

. He studied Scripture

, especially of Paul

, and Evangelical

doctrine. He was present at the disputation of Leipzig (1519) as a spectator, but participated by his comments. Johann Eck

having attacked his views, Melanchthon replied based on the authority of Scripture in his Defensio contra Johannem Eckium (Wittenberg, 1519).

After lectures on the Gospel of Matthew

and the Epistle to the Romans

, together with his investigations into the doctrines of Paul, he was granted the degree of bachelor of theology

, and was transferred to the theological faculty. He married Katharina Krapp, daughter of Wittenberg's mayor

, on 25 November 1520.

and ecclesiastical practises which were at variance with Scripture. But while Luther was absent at Wartburg Castle

, during the disturbances caused by the Zwickau prophets

, Melanchthon wavered.

The appearance of Melanchthon's Loci communes rerum theologicarum seu hypotyposes theologicae

(Wittenberg and Basel

, 1521) was of subsequent importance for Reformation. Melanchthon presented the new doctrine of Christianity under the form of a discussion of the "leading thoughts" of the Epistle to the Romans. Loci communes began the gradual rise of the Lutheran scholastic

tradition, and the later theologians Martin Chemnitz

, Mathias Haffenreffer

, and Leonhard Hutter

expanded upon it. Melanchthon continued to lecture on the classics.

On a journey in 1524 to his native town, he encountered the papal legate

, Cardinal

Lorenzo Campeggio who tried to draw him from Luther's cause. In his Unterricht der Visitatorn an die Pfarherrn im Kurfürstentum zu Sachssen (1528) Melanchthon presented the evangelical doctrine of salvation as well as regulations for churches and schools.

In 1529 he accompanied the elector

to the Diet of Speyer

. His hopes of inducing the Imperial

party to a recognition of the Reformation were not fulfilled. A friendly attitude towards the Swiss

at the Diet was something he later changed, calling Zwingli

's doctrine of the Lord's Supper

"an impious dogma

".

The composition now known as the Augsburg Confession

The composition now known as the Augsburg Confession

was laid before the Diet of Augsburg

in 1530, and would come to be considered perhaps the most significant document of the Protestant Reformation

. While the confession was based on Luther's Marburg

and Schwabach

articles, it was mainly the work of Melanchthon. Although commonly thought of as a unified statement of doctrine by the two reformers, Luther did not conceal his dissatisfaction with the irenic tone of the confession. Indeed, some would criticize Melanchthon's conduct at the Diet as unbecoming of the principle he promoted, implying that faith in the truth of his cause would logically have inspired Melanchthon to a more firm and dignified posture. Others point out that he had not sought the part of a political leader, suggesting that he seemed to lack the requisite energy and decision for such a role and may simply have been a lackluster judge of human nature. Melanchthon's subsequent Apology of the Augsburg Confession

reveals further doctrinal strains with Luther.

Melanchthon then settled into the comparative quiet of his academic and literary labors. His most important theological work of this period was the Commentarii in Epistolam Pauli ad Romanos (Wittenberg, 1532), noteworthy for introducing the idea that "to be justified" means "to be accounted just," whereas the Apology had placed side by side the meanings of "to be made just" and "to be accounted just." Melanchthon's increasing fame gave occasion for several honorable calls to Tübingen (Sept., 1534), to France

, and to England

, but consideration of the elector caused him to refuse them.

sent by Bucer

to Wittenberg, and at the instigation of the Landgrave of Hesse

discussed the question with Bucer in Kassel

, at the end of 1534. He eagerly labored for an agreement, for his patristic studies and the Dialogue (1530) of Œcolampadius

had made him doubt the correctness of Luther's doctrine. Moreover, after the death of Zwingli and the change of the political situation his earlier scruples in regard to a union lost their weight. Bucer did not go so far as to believe with Luther that the true body of Christ in the Lord's Supper is bitten by the teeth, but admitted the offering of the body and blood in the symbols of bread and wine. Melanchthon discussed Bucer's views with the most prominent adherents of Luther; but Luther himself would not agree to a mere veiling of the dispute. Melanchthon's relation to Luther was not disturbed by his work as a mediator, although Luther for a time suspected that Melanchthon was "almost of the opinion of Zwingli"; nevertheless he desired to "share his heart with him."

During his sojourn in Tübingen in 1536 Melanchthon was severely attacked by Cordatus, preacher

in Niemeck, because he had taught that works are necessary for salvation. In the second edition of his Loci (1535) he abandoned his earlier strict doctrine of determinism which went even beyond that of Augustine

, and in its place taught more clearly his so-called Synergism. He repulsed the attack of Cordatus in a letter to Luther and his other colleagues by stating that he had never departed from their common teachings on this subject, and in the Antinomian Controversy of 1537 Melanchthon was in harmony with Luther.

(1547). It is true, Melanchthon rejected the Augsburg Interim

, which the emperor

tried to force upon the defeated Protestants; but in the negotiations concerning the so-called Leipzig Interim

he made concessions which many feel can in no way be justified, even if one considers his difficult position, opposed as he was to the elector and the emperor.

In agreeing to various Roman usages, Melanchthon started from the opinion that they are adiaphora

if nothing is changed in the pure doctrine and the sacraments which Jesus

instituted, but he disregarded the position that concessions made under such circumstances have to be regarded as a denial of Evangelical convictions.

Melanchthon himself perceived his faults in the course of time and repented of them, perhaps having to suffer more than was just in the displeasure of his friends and the hatred of his enemies. From now on until his death he was full of trouble and suffering. After Luther's death he became the "theological leader of the German Reformation," not indisputably, however; for the Lutherans with Matthias Flacius

at their head accused him and his followers of heresy

and apostasy

. Melanchthon bore all accusations and calumnies with admirable patience

, dignity

, and self-control.

In his controversy on justification with Andreas Osiander

In his controversy on justification with Andreas Osiander

Melanchthon satisfied all parties. Melanchthon took part also in a controversy with Stancari, who held that Christ was our justification

only according to his human nature.

He was also still a strong opponent of the Roman Catholics, for it was by his advice that the elector of Saxony declared himself ready to send deputies to a council to be convened at Trent

, but only under the condition that the Protestants should have a share in the discussions, and that the Pope

should not be considered as the presiding officer and judge. As it was agreed upon to send a confession to Trent, Melanchthon drew up the Confessio Saxonica which is a repetition of the Augsburg Confession, discussing, however, in greater detail, but with moderation, the points of controversy with Rome

. Melanchthon on his way to Trent at Dresden

saw the military preparations of Maurice of Saxony

, and after proceeding as far as Nuremberg

, returned to Wittenberg in March 1552, for Maurice had turned against the emperor. Owing to his act, the condition of the Protestants became more favorable and were still more so at the Peace of Augsburg

(1555), but Melanchthon's labors and sufferings increased from that time.

The last years of his life were embittered by the disputes over the Interim and the freshly started controversy on the Lord's Supper. As the statement "good works are necessary for salvation" appeared in the Leipzig Interim, its Lutheran opponents attacked in 1551 Georg Major

, the friend and disciple of Melanchthon, so Melanchthon dropped the formula altogether, seeing how easily it could be misunderstood.

But all his caution and reservation did not hinder his opponents from continually working against him, accusing him of synergism and Zwinglianism. At the Colloquy of Worms

in 1557 which he attended only reluctantly, the adherents of Flacius and the Saxon theologians tried to avenge themselves by thoroughly humiliating Melanchthon, in agreement with the malicious desire of the Roman Catholics to condemn all heretics

, especially those who had departed from the Augsburg Confession, before the beginning of the conference. As this was directed against Melanchthon himself, he protested, so that his opponents left, greatly to the satisfaction of the Roman Catholics who now broke off the colloquy, throwing all blame upon the Protestants. The Reformation in the sixteenth century did not experience a greater insult, as Nietzsche says.

Nevertheless, Melanchthon persevered in his efforts for the peace of the Church, suggesting a synod

of the Evangelical party and drawing up for the same purpose the Frankfurt Recess, which he defended later against the attacks of his enemies.

More than anything else the controversies on the Lord's Supper embittered the last years of his life. The renewal of this dispute was due to the victory in the Reformed Church of the Calvinistic

doctrine and its influence upon Germany. To its tenets Melanchthon never gave his assent, nor did he use its characteristic formulas. The personal presence and self-impartation of Christ in the Lord's Supper were especially important for Melanchthon; but he did not definitely state how body and blood are related to this. Although rejecting the physical act of mastication

, he nevertheless assumed the real presence of the body of Christ and therefore also a real self-impartation. Melanchthon differed from Calvin

also in emphasizing the relation of the Lord's Supper to justification.

s rather critically but developed positive commentaries about Mary. In his Annotations in Evangelia commenting on Lk 2,52, he discusses the faith of Mary, “she kept all things in her heart” which to Melanchton is a call to the Church to follow her example. During the marriage at Cana

, Melanchton points out that Mary went too far, asking for more wine, misusing her position. But she was not upset, when Jesus gently scolded her. Mary was negligent, when she lost her son in the temple, but she did not sin. Mary was conceived with original sin like every other human being, but she was spared the consequences of it. Consequently, Melanchton opposed the feast of the Immaculate Conception

, which in his days, although not dogma, was celebrated in several cities and had been approved at the Council of Basel in 1439. He declared that the Immaculate Conception was an invention of monks. Mary is a representation (Typus) of the Church and in the Magnificat

, Mary spoke for the whole Church. Standing under the cross, Mary suffered like no other human being. Consequently Christians have to unite with her under the Cross, in order to become Christ-like.

The only care that occupied him until his last moment was the desolate condition of the Church. He strengthened himself in almost uninterrupted prayer, and in listening to passages of Scripture. Especially significant did the words seem to him, "His own received him not; but as many as received him, to them gave he power to become the sons of God." When Caspar Peucer

, his son in-law, asked him if he wanted anything, he replied, "Nothing but heaven." His body was laid beside Luther's in the Schloßkirche in Wittenberg.

He is commemorated in the Calendar of Saints

of the Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod

on February 16 and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

on June 25 (The LCMS commemorates him on his date of birth, and the ELCA on the date of the presentation of the Augsburg Confession

).

Both men had a clear consciousness of their mutual position and the divine necessity of their common calling. Melanchthon wrote in 1520, "I would rather die than be separated from Luther," whom he afterward compared to Elijah, and called "the man full of the Holy Ghost

." In spite of the strained relations between them in the last years of Luther's life, Melanchthon exclaimed at Luther's death, "Dead is the horseman and chariot of Israel who ruled the Church in this last age of the world!"

On the other hand, Luther wrote of Melanchthon, in the preface to Melanchthon's Commentary on the Galatians (1529), "I had to fight with rabble and devil

s, for which reason my books are very warlike. I am the rough pioneer who must break the road; but Master Philipp comes along softly and gently, sows and waters heartily, since God has richly endowed him with gifts." Luther also did justice to Melanchthon's teachings, praising one year before his death in the preface to his own writings Melanchthon's revised Loci above them and calling Melanchthon "a divine instrument which has achieved the very best in the department of theology to the great rage of the devil and his scabby tribe." It is remarkable that Luther, who vehemently attacked men like Erasmus and Bucer, when he thought that truth was at stake, never spoke directly against Melanchthon, and even during his melancholy last years conquered his temper.

The strained relation between these two men never came from external things, such as human rank and fame, much less from other advantages, but always from matters of Church and doctrine, and chiefly from the fundamental difference of their individualities; they repelled and attracted each other "because nature had not formed out of them one man." However, it can not be denied that Luther was the more magnanimous, for however much he was at times dissatisfied with Melanchthon's actions, he never uttered a word against his private character; but Melanchthon, on the other hand, sometimes evinced a lack of confidence in Luther. In a letter to Carlowitz he complained that Luther on account of his polemical nature exercised a personally humiliating pressure upon him.

Melanchthon was not said to lack personal courage, but rather he was said to be less of an aggressive than of a passive nature. When he was reminded how much power and strength Luther drew from his trust in God

, he answered, "If I myself do not do my part, I can not expect anything from God in prayer." His nature was seen to be inclined to suffer with faith

in God that he would be released from every evil

rather than to act valiantly with his aid.

The distinction between Luther and Melanchthon is well brought out in Luther's letters to the latter (June, 1530): "To your great anxiety by which you are made weak, I am a cordial foe; for the cause is not ours. It is your philosophy, and not your theology, which tortures you so,-- as though you could accomplish anything by your useless anxieties. So far as the public cause is concerned, I am well content and satisfied; for I know that it is right and true, and, what is more, it is the cause of Christ and God himself. For that reason, I am merely a spectator. If we fall, Christ will likewise fall; and if he fall, I would rather fall with Christ than stand with the emperor."

Another trait of his character was his love of peace. He had an innate aversion to quarrels and discord; yet, often he was very irritable. His irenical character often led him to adapt himself to the views of others, as may be seen from his correspondence with Erasmus and from his public attitude from the Diet of Augsburg to the Interim. It was said not to be merely a personal desire for peace, but his conservative religious nature that guided him in his acts of conciliation. He never could forget that his father on his death-bed had besought his family "never to leave the Church." He stood toward the history of the Church in an attitude of piety and reverence that made it much more difficult for him than for Luther to be content with the thought of the impossibility of a reconciliation with the Roman Catholic Church. He laid stress upon the authority of the Fathers, not only of Augustine

, but also of the Greeks

.

His attitude in matters of worship was conservative

, and in the Leipsic Interim he was said by Cordatus and Schenk even to be Crypto-Catholic. He never strove for a reconciliation with Roman Catholicism at the price of pure doctrine. He attributed more value to the external appearance and organization of the Church than Luther did, as can be seen from his whole treatment of the "doctrine of the Church." The ideal conception of the Church, which the Reformers opposed to the organization of the Roman Church, which was expressed in his Loci of 1535, lost for him after 1537 its former prominence, when he began to emphasize the conception of the true visible Church as it may be found among the Evangelicals.

The relation of the Church to God he found in the divinely ordered office, the ministry of the Gospel. The universal priesthood was for Melanchthon as for Luther no principle of an ecclesiastical constitution, but a purely religious principle. In accordance with this idea Melanchthon tried to keep the traditional church constitution and government, including the bishops. He did not want, however, a church altogether independent of the State, but rather, in agreement with Luther, he believed it the duty of the secular authorities to protect religion and the Church. He looked upon the consistories as ecclesiastical courts which therefore should be composed of spiritual and secular judges, for to him the official authority of the Church did not lie in a special class of priests, but rather in the whole congregation, to be represented therefore not only by ecclesiastics, but also by laymen. Melanchthon in advocating church union did not overlook differences in doctrine for the sake of common practical tasks.

The older he grew, the less he distinguished between the Gospel as the announcement of the will of God, and right doctrine as the human knowledge of it. Therefore he took pains to safeguard unity in doctrine by theological formulas of union, but these were made as broad as possible and were restricted to the needs of practical religion.

Knowledge had for him no purpose of its own; it existed only for the service of moral and religious education, and so the teacher of Germany prepared the way for the religious thoughts of the Reformation. He is the father of Christian humanism

, which has exerted a lasting influence upon scientific life in Germany. [But it is Erasmus who is called, "The Prince of the Humanists.]

His works were not always new and original, but they were clear, intelligible, and answered their purpose. His style is natural and plain, better, however, in Latin and Greek than in German. He was not without natural eloquence, although his voice was weak.

The fundamental difference between Luther and Melanchthon lies not so much in the latter's ethical conception, as in his humanistic

mode of thought which formed the basis of his theology and made him ready not only to acknowledge moral and religious truths outside of Christianity, but also to bring Christian truth into closer contact with them, and thus to mediate between Christian revelation and ancient philosophy

.

Melanchthon's views differed from Luther's only in some modifications of ideas. Melanchthon looked upon the law as not only the correlate of the Gospel, by which its effect of salvation is prepared, but as the unchangeable order of the spiritual world which has its basis in God himself. He furthermore reduced Luther's much richer view of redemption to that of legal satisfaction. He did not draw from the vein of mysticism running through Luther's theology, but emphasized the ethical and intellectual elements.

After giving up determinism and absolute predestination and ascribing to man a certain moral freedom, he tried to ascertain the share of free will

in conversion, naming three causes as concurring in the work of conversion, the Word, the Spirit, and the human will, not passive, but resisting its own weakness. Since 1548 he used the definition of freedom formulated by Erasmus, "the capability of applying oneself to grace

."

His definition of faith lacks the mystical depth of Luther. In dividing faith into knowledge, assent, and trust, he made the participation of the heart subsequent to that of the intellect, and so gave rise to the view of the later orthodoxy that the establishment and acceptation of pure doctrine should precede the personal attitude of faith. To his intellectual conception of faith corresponded also his view that the Church also is only the communion of those who adhere to the true belief and that her visible existence depends upon the consent of her unregenerated members to her teachings.

Finally, Melanchthon's doctrine of the Lord's Supper, lacking the profound mysticism of faith by which Luther united the sensual elements and supersensual realities, demanded at least their formal distinction.

The development of Melanchthon's beliefs may be seen from the history of the Loci. In the beginning Melanchthon intended only a development of the leading ideas representing the Evangelical conception of salvation, while the later editions approach more and more the plan of a text-book of dogma. At first he uncompromisingly insisted on the necessity of every event, energetically rejected the philosophy of Aristotle

, and had not fully developed his doctrine of the sacraments.

In 1535 he treated for the first time the doctrine of God and that of the Trinity

; rejected the doctrine of the necessity of every event and named free will as a concurring cause in conversion. The doctrine of justification received its forensic form and the necessity of good works was emphasized in the interest of moral discipline. The last editions are distinguished from the earlier ones by the prominence given to the theoretical and rational element.

. His principal works in this line were Prolegomena to Cicero's De officiis (1525); Enarrationes librorum Ethicorum Aristotelis (1529); Epitome philosophiae moralis (1538); and Ethicae doctrinae elementa (1550).

In his Epitome philosophiae moralis Melanchthon treats first the relation of philosophy to the law of God and the Gospel. Moral philosophy, it is true, does not know anything of the promise of grace as revealed in the Gospel, but it is the development of the natural law implanted by God in the heart of man, and therefore representing a part of the divine law. The revealed law, necessitated because of sin

, is distinguished from natural law only by its greater completeness and clearness. The fundamental order of moral life can be grasped also by reason; therefore the development of moral philosophy from natural principles must not be neglected. Melanchthon therefore made no sharp distinction between natural and revealed morals.

His contribution to Christian ethics in the proper sense must be sought in the Augsburg Confession and its Apology as well as in his Loci, where he followed Luther in depicting the Evangelical ideal of life, the free realization of the divine law by a personality blessed in faith and filled with the spirit of God.

ian, and finally a witness." By "grammarian" he meant the philologist

in the modern sense who is master of history

, archaeology

, and ancient geography

. As to the method of interpretation, he insisted with great emphasis upon the unity of the sense, upon the literal sense in contrast to the four senses of the scholastics. He further stated that whatever is looked for in the words of Scripture, outside of the literal sense, is only dogmatic or practical application.

His commentaries, however, are not grammatical, but are full of theological and practical matter, confirming the doctrines of the Reformation, and edifying believers. The most important of them are those on Genesis, Proverbs

, Daniel

, the Psalms

, and especially those on the New Testament

, on Romans

(edited in 1522 against his will by Luther), Colossians (1527), and John

(1523). Melanchthon was the constant assistant of Luther in his translation of the Bible, and both the books of the Maccabees

in Luther's Bible are ascribed to him. A Latin

Bible published in 1529 at Wittenberg is designated as a common work of Melanchthon and Luther.

. His was the first Protestant attempt at a history of dogma, Sententiae veterum aliquot patrum de caena domini (1530) and especially De ecclesia et auctoritate verbi Dei (1539).

Melanchthon exerted a wide influence in the department of homiletics, and has been regarded as the author, in the Protestant Church, of the methodical style of preaching. He himself keeps entirely aloof from all mere dogmatizing or rhetoric

in the Annotationes in Evangelia (1544), the Conciones in Evangelium Matthaei (1558), and in his German

sermons prepared for George of Anhalt. He never preached from the pulpit; and his Latin sermons (Postilla) were prepared for the Hungarian

students at Wittenberg who did not understand German. In this connection may be mentioned also his Catechesis puerilis (1532), a religious manual for younger students, and a German catechism

(1549), following closely Luther's arrangement.

From Melanchthon came also the first Protestant work on the method of theological study, so that it may safely be said that by his influence every department of theology was advanced even if he was not always a pioneer.

, Wimpheling

, and Rodolphus Agricola

, who represented an ethical conception of the humanities

. The liberal arts

and a classical education

were for him only a means to an ethical and religious end. The ancient classics were for him in the first place the sources of a purer knowledge, but they were also the best means of educating the youth both by their beauty of form and by their ethical content. By his organizing activity in the sphere of educational institutions and by his compilations of Latin and Greek grammar

s and commentaries, Melanchthon became the founder of the learned schools of Evangelical Germany, a combination of humanistic and Christian ideals. In philosophy also Melanchthon was the teacher of the whole German Protestant world. The influence of his philosophical compendia ended only with the rule of the Leibniz-Wolff school.

He started from scholasticism

; but with the contempt of an enthusiastic Humanist he turned away from it and came to Wittenberg with the plan of editing the complete works of Aristotle. Under the dominating religious influence of Luther his interest abated for a time, but in 1519 he edited the "Rhetoric" and in 1520 the "Dialectic."

The relation of philosophy to theology is characterized, according to him, by the distinction between law and Gospel. The former, as a light of nature, is innate; it also contains the elements of the natural knowledge of God which, however, have been obscured and weakened by sin. Therefore, renewed promulgation of the law by revelation became necessary and was furnished in the Decalogue; and all law, including that in the scientific form of philosophy, contains only demands, shadowings; its fulfilment is given only in the Gospel, the object of certainty in theology, by which also the philosophical elements of knowledge—experience, principles of reason, and syllogism

-- receive only their final confirmation. As the law is a divinely ordered pedagogue that leads to Christ, philosophy, its interpreter, is subject to revealed truth as the principal standard of opinions and life.

Besides Aristotle's "Rhetoric" and "Dialectic" he published

De dialecta libri iv (1528);

Erotemata dialectices (1547);

Liber de anima (1540);

Initia doctrinae physicae (1549); and

Ethicae doctrinae elementa (1550).

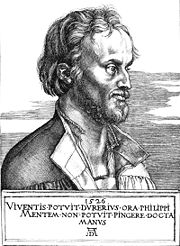

in various versions, one of them in the Royal Gallery of Hanover

, by Albrecht Dürer

(made in 1526, meant to convey a spiritual rather than physical likeness and said to be eminently successful in doing so), and by Lucas Cranach

.

Melanchthon was dwarfish, misshapen, and physically weak, although he is said to have had a bright and sparkling eye, which kept its color till the day of his death. He was never in perfectly sound health, and managed to perform as much work as he did only by reason of the extraordinary regularity of his habits and his great temperance. He set no great value on money and possessions; his liberality and hospitality were often misused in such a way that his old faithful Swabia

n servant had sometimes difficulty in managing the household.

His domestic life was happy. He called his home "a little church of God," always found peace there, and showed a tender solicitude for his wife and children. To his great astonishment a French scholar found him rocking the cradle with one hand, and holding a book in the other.

His noble soul showed itself also in his friendship for many of his contemporaries; "there is nothing sweeter nor lovelier than mutual intercourse with friends," he used to say. His most intimate friend was Joachim Camerarius

, whom he called the half of his soul. His extensive correspondence was for him not only a duty, but a need and an enjoyment. His letters form a valuable commentary on his whole life, as he spoke out his mind in them more unreservedly than he was wont to do in public life. A peculiar example of his sacrificing friendship is furnished by the fact that he wrote speeches and scientific treatises for others, permitting them to use their own signature. But in the kindness of his heart he was said to be ready to serve and assist not only his friends, but everybody.

He was an enemy to jealousy

, envy

, slander, and sarcasm

. His whole nature adapted him especially to the intercourse with scholars and men of higher rank, while it was more difficult for him to deal with the people of lower station. He never allowed himself or others to exceed the bounds of nobility, honesty, and decency. He was very sincere in the judgment of his own person, acknowledging his faults even to opponents like Flacius

, and was open to the criticism even of such as stood far below him. In his public career he sought not honor or fame, but earnestly endeavored to serve the Church and the cause of truth.

His humility and modesty had their root in his personal piety. He laid great stress upon prayer, daily meditation on the Word, and attendance of public service. In Melanchthon is found not a great, impressive personality, winning its way by massive strength of resolution and energy, but a noble character hard to study without loving and respecting.

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

, intellectual leader of the Lutheran Reformation, and an influential designer of educational systems. He stands next to Luther and Calvin

John Calvin

John Calvin was an influential French theologian and pastor during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of Christian theology later called Calvinism. Originally trained as a humanist lawyer, he broke from the Roman Catholic Church around 1530...

as a reformer, theologian, and molder of Protestantism. As much as Luther, he is the primary founder of Lutheranism

Lutheranism

Lutheranism is a major branch of Western Christianity that identifies with the theology of Martin Luther, a German reformer. Luther's efforts to reform the theology and practice of the church launched the Protestant Reformation...

. They both denounced what they claimed was the exaggerated cult of the saints, justification by works, and the coercion of the conscience in the sacrament of penance that nevertheless could not offer certainty of salvation.

Melanchthon made the distinction between law and gospel the central formula for Lutheran evangelical insight. By the "law" he meant God's requirements both in Old and New Testament; the "gospel" meant the free gift of grace through faith in Jesus Christ.

Early life and education

He was born Philipp Schwartzerdt (of which "Melanchthon" is a Greek translation) on 16 February 1497, at BrettenBretten

Bretten is a town in the state of Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is located on Bertha Benz Memorial Route.-Geography:Bretten lies in the centre of a rectangle that is formed by Heidelberg, Karlsruhe, Heilbronn and Stuttgart as corners. It has a population of approximately 28,000. The centre of...

, near Karlsruhe

Karlsruhe

The City of Karlsruhe is a city in the southwest of Germany, in the state of Baden-Württemberg, located near the French-German border.Karlsruhe was founded in 1715 as Karlsruhe Palace, when Germany was a series of principalities and city states...

, where his father Georg Schwarzerdt was armorer to Philip, Count Palatine of the Rhine. His birthplace was demolished in 1689 and the town's Melanchthonhaus

Melanchthonhaus (Bretten)

The Melanchthonhaus is a museum and research facility of the Protestant Reformation in Bretten, particularly on the life of Philipp Melanchthon...

built on its site in 1897.

In 1507 he was sent to the Latin school at Pforzheim

Pforzheim

Pforzheim is a town of nearly 119,000 inhabitants in the state of Baden-Württemberg, southwest Germany at the gate to the Black Forest. It is world-famous for its jewelry and watch-making industry. Until 1565 it was the home to the Margraves of Baden. Because of that it gained the nickname...

, where the rector, Georg Simler of Wimpfen, introduced him to the Latin and Greek poets and Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

. He was influenced by his great-uncle Johann Reuchlin

Johann Reuchlin

Johann Reuchlin was a German humanist and a scholar of Greek and Hebrew. For much of his life, he was the real centre of all Greek and Hebrew teaching in Germany.-Early life:...

, brother of his maternal grandmother, a representative humanist

Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanism was an activity of cultural and educational reform engaged by scholars, writers, and civic leaders who are today known as Renaissance humanists. It developed during the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth centuries, and was a response to the challenge of Mediæval...

. It was Reuchlin who suggested the change from Schwarzerdt (literally Black-earth), into the Greek equivalent Melanchthon (Μελάγχθων).

Still young, he entered in 1509 the University of Heidelberg where he studied philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

, rhetoric

Rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of discourse, an art that aims to improve the facility of speakers or writers who attempt to inform, persuade, or motivate particular audiences in specific situations. As a subject of formal study and a productive civic practice, rhetoric has played a central role in the Western...

, and astronomy

Astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that deals with the study of celestial objects and phenomena that originate outside the atmosphere of Earth...

/astrology

Astrology

Astrology consists of a number of belief systems which hold that there is a relationship between astronomical phenomena and events in the human world...

, and was known as a good Greek scholar. On being refused the degree of master in 1512 on account of his youth, he went to Tübingen, where he continued humanistic studies, but also worked on jurisprudence

Jurisprudence

Jurisprudence is the theory and philosophy of law. Scholars of jurisprudence, or legal theorists , hope to obtain a deeper understanding of the nature of law, of legal reasoning, legal systems and of legal institutions...

, mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

, and medicine

Medicine

Medicine is the science and art of healing. It encompasses a variety of health care practices evolved to maintain and restore health by the prevention and treatment of illness....

. While there, he was taught the technical aspects of astrology by Johannes Stöffler

Johannes Stöffler

Johannes Stöffler was a German mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, priest, maker of astronomical instruments and professor at the University of Tübingen.-Life:...

.

Having taken the degree of master in 1516, he began to study theology

Theology

Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

. Under the influence of men like Reuchlin and Erasmus he became convinced that true Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

was something different from scholastic theology

Scholasticism

Scholasticism is a method of critical thought which dominated teaching by the academics of medieval universities in Europe from about 1100–1500, and a program of employing that method in articulating and defending orthodoxy in an increasingly pluralistic context...

as it was taught at the university. He became conventor (repentant) in the contubernium and instructed younger scholars. He also lectured on oratory, on Virgil

Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro, usually called Virgil or Vergil in English , was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He is known for three major works of Latin literature, the Eclogues , the Georgics, and the epic Aeneid...

and Livy

Livy

Titus Livius — known as Livy in English — was a Roman historian who wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people. Ab Urbe Condita Libri, "Chapters from the Foundation of the City," covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome well before the traditional foundation in 753 BC...

.

His first publications were an edition of Terence

Terence

Publius Terentius Afer , better known in English as Terence, was a playwright of the Roman Republic, of North African descent. His comedies were performed for the first time around 170–160 BC. Terentius Lucanus, a Roman senator, brought Terence to Rome as a slave, educated him and later on,...

(1516) and his Greek grammar (1518), but he had written previously the preface to the Epistolae clarorum virorum of Reuchlin (1514).

Professor at Wittenberg

Opposed as a reformer at Tübingen, he accepted a call to the University of Wittenberg by Martin LutherMartin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

. He studied Scripture

Bible

The Bible refers to any one of the collections of the primary religious texts of Judaism and Christianity. There is no common version of the Bible, as the individual books , their contents and their order vary among denominations...

, especially of Paul

Paul of Tarsus

Paul the Apostle , also known as Saul of Tarsus, is described in the Christian New Testament as one of the most influential early Christian missionaries, with the writings ascribed to him by the church forming a considerable portion of the New Testament...

, and Evangelical

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

doctrine. He was present at the disputation of Leipzig (1519) as a spectator, but participated by his comments. Johann Eck

Johann Eck

Dr. Johann Maier von Eck was a German Scholastic theologian and defender of Catholicism during the Protestant Reformation. It was Eck who argued that the beliefs of Martin Luther and Jan Hus were similar.-Life:...

having attacked his views, Melanchthon replied based on the authority of Scripture in his Defensio contra Johannem Eckium (Wittenberg, 1519).

After lectures on the Gospel of Matthew

Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel According to Matthew is one of the four canonical gospels, one of the three synoptic gospels, and the first book of the New Testament. It tells of the life, ministry, death, and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth...

and the Epistle to the Romans

Epistle to the Romans

The Epistle of Paul to the Romans, often shortened to Romans, is the sixth book in the New Testament. Biblical scholars agree that it was composed by the Apostle Paul to explain that Salvation is offered through the Gospel of Jesus Christ...

, together with his investigations into the doctrines of Paul, he was granted the degree of bachelor of theology

Bachelor of Theology

The Bachelor of Theology is a three to five year undergraduate degree in theological disciplines. Candidates for this degree typically must complete course work in Greek or Hebrew, as well as systematic theology, biblical theology, ethics, homiletics and Christian ministry...

, and was transferred to the theological faculty. He married Katharina Krapp, daughter of Wittenberg's mayor

Mayor

In many countries, a Mayor is the highest ranking officer in the municipal government of a town or a large urban city....

, on 25 November 1520.

Theological disputes

In the beginning of 1521 in his Didymi Faventini versus Thomam Placentinum pro M. Luthero oratio (Wittenberg, n.d.), he defended Luther. He argued that Luther rejected only papalPope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

and ecclesiastical practises which were at variance with Scripture. But while Luther was absent at Wartburg Castle

Wartburg Castle

The Wartburg is a castle situated on a 1230-foot precipice to the southwest of, and overlooking the town of Eisenach, in the state of Thuringia, Germany...

, during the disturbances caused by the Zwickau prophets

Zwickau prophets

The Zwickau Prophets were three men from Zwickau of the Radical Reformation who were possibly involved in a disturbance in nearby Wittenberg and its reformation in early 1522....

, Melanchthon wavered.

The appearance of Melanchthon's Loci communes rerum theologicarum seu hypotyposes theologicae

Loci Communes

Loci Communes or Loci communes rerum theologicarum seu hypotyposes theologicae was a work by the Lutheran theologian Philipp Melancthon published in 1521...

(Wittenberg and Basel

Basel

Basel or Basle In the national languages of Switzerland the city is also known as Bâle , Basilea and Basilea is Switzerland's third most populous city with about 166,000 inhabitants. Located where the Swiss, French and German borders meet, Basel also has suburbs in France and Germany...

, 1521) was of subsequent importance for Reformation. Melanchthon presented the new doctrine of Christianity under the form of a discussion of the "leading thoughts" of the Epistle to the Romans. Loci communes began the gradual rise of the Lutheran scholastic

Lutheran scholasticism

Lutheran scholasticism was a theological method that gradually developed during the era of Lutheran Orthodoxy. Theologians used the neo-Aristotelian form of presentation, already popular in academia, in their writings and lectures...

tradition, and the later theologians Martin Chemnitz

Martin Chemnitz

Martin Chemnitz was an eminent second-generation Lutheran theologian, reformer, churchman, and confessor...

, Mathias Haffenreffer

Mathias Haffenreffer

Matthias Hafenreffer was a German orthodox Lutheran theologian in the Lutheran scholastic tradition. Born at Lorch , he was professor at Tübingen from 1592 until his death in 1617. He was a motivating teacher with a charismatic influence upon his students. He combined strict faithfulness to the...

, and Leonhard Hutter

Leonhard Hutter

Leonhard Hutter was a German Lutheran theologian.-Life:He was born at Nellingen near Ulm. From 1581 he studied at the universities of Strasbourg, Leipzig, Heidelberg and Jena...

expanded upon it. Melanchthon continued to lecture on the classics.

On a journey in 1524 to his native town, he encountered the papal legate

Papal legate

A papal legate – from the Latin, authentic Roman title Legatus – is a personal representative of the pope to foreign nations, or to some part of the Catholic Church. He is empowered on matters of Catholic Faith and for the settlement of ecclesiastical matters....

, Cardinal

Cardinal (Catholicism)

A cardinal is a senior ecclesiastical official, usually an ordained bishop, and ecclesiastical prince of the Catholic Church. They are collectively known as the College of Cardinals, which as a body elects a new pope. The duties of the cardinals include attending the meetings of the College and...

Lorenzo Campeggio who tried to draw him from Luther's cause. In his Unterricht der Visitatorn an die Pfarherrn im Kurfürstentum zu Sachssen (1528) Melanchthon presented the evangelical doctrine of salvation as well as regulations for churches and schools.

In 1529 he accompanied the elector

Prince-elector

The Prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire were the members of the electoral college of the Holy Roman Empire, having the function of electing the Roman king or, from the middle of the 16th century onwards, directly the Holy Roman Emperor.The heir-apparent to a prince-elector was known as an...

to the Diet of Speyer

Second Diet of Speyer

The Diet of Speyer or the Diet of Spires was a diet of the Holy Roman Empire in 1529 in the Imperial City of Speyer . The diet condemned the results of the Diet of Speyer of 1526 and prohibited future reformation...

. His hopes of inducing the Imperial

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

party to a recognition of the Reformation were not fulfilled. A friendly attitude towards the Swiss

Switzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

at the Diet was something he later changed, calling Zwingli

Huldrych Zwingli

Ulrich Zwingli was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland. Born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system, he attended the University of Vienna and the University of Basel, a scholarly centre of humanism...

's doctrine of the Lord's Supper

Eucharist

The Eucharist , also called Holy Communion, the Sacrament of the Altar, the Blessed Sacrament, the Lord's Supper, and other names, is a Christian sacrament or ordinance...

"an impious dogma

Dogma

Dogma is the established belief or doctrine held by a religion, or a particular group or organization. It is authoritative and not to be disputed, doubted, or diverged from, by the practitioners or believers...

".

Augsburg Confession

Augsburg Confession

The Augsburg Confession, also known as the "Augustana" from its Latin name, Confessio Augustana, is the primary confession of faith of the Lutheran Church and one of the most important documents of the Lutheran reformation...

was laid before the Diet of Augsburg

Diet of Augsburg

The Diet of Augsburg were the meetings of the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire in the German city of Augsburg. There were many such sessions, but the three meetings during the Reformation and the ensuing religious wars between the Roman Catholic emperor Charles V and the Protestant...

in 1530, and would come to be considered perhaps the most significant document of the Protestant Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

. While the confession was based on Luther's Marburg

Marburg

Marburg is a city in the state of Hesse, Germany, on the River Lahn. It is the main town of the Marburg-Biedenkopf district and its population, as of March 2010, was 79,911.- Founding and early history :...

and Schwabach

Schwabach

Schwabach is a German town of about 40,000 inhabitants near Nuremberg, in the center of the region of Franconia in the North of Bavaria. The city is an autonomous administrative district . Schwabach is also the name of a river which runs through the city prior joining the Rednitz.Schwabach is...

articles, it was mainly the work of Melanchthon. Although commonly thought of as a unified statement of doctrine by the two reformers, Luther did not conceal his dissatisfaction with the irenic tone of the confession. Indeed, some would criticize Melanchthon's conduct at the Diet as unbecoming of the principle he promoted, implying that faith in the truth of his cause would logically have inspired Melanchthon to a more firm and dignified posture. Others point out that he had not sought the part of a political leader, suggesting that he seemed to lack the requisite energy and decision for such a role and may simply have been a lackluster judge of human nature. Melanchthon's subsequent Apology of the Augsburg Confession

Apology of the Augsburg Confession

The Apology of the Augsburg Confession was written by Philipp Melanchthon during and after the 1530 Diet of Augsburg as a response to the Pontifical Confutation of the Augsburg Confession, Charles V's commissioned official Roman Catholic response to the Lutheran Augsburg Confession of June 25, 1530...

reveals further doctrinal strains with Luther.

Melanchthon then settled into the comparative quiet of his academic and literary labors. His most important theological work of this period was the Commentarii in Epistolam Pauli ad Romanos (Wittenberg, 1532), noteworthy for introducing the idea that "to be justified" means "to be accounted just," whereas the Apology had placed side by side the meanings of "to be made just" and "to be accounted just." Melanchthon's increasing fame gave occasion for several honorable calls to Tübingen (Sept., 1534), to France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, and to England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

, but consideration of the elector caused him to refuse them.

Discussions on Lord's Supper and Justification

He took an important part in the discussions concerning the Lord's Supper which began in 1531. He approved fully of the Wittenberg ConcordWittenberg Concord

Wittenberg Concord , is a religious concordat signed by Reformed and Lutheran theologians and churchmen on May 29, 1536 as an attempted resolution of their differences with respect to the Real Presence of Christ's body and blood in the Eucharist...

sent by Bucer

Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer was a Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg who influenced Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican doctrines and practices. Bucer was originally a member of the Dominican Order, but after meeting and being influenced by Martin Luther in 1518 he arranged for his monastic vows to be annulled...

to Wittenberg, and at the instigation of the Landgrave of Hesse

Hesse

Hesse or Hessia is both a cultural region of Germany and the name of an individual German state.* The cultural region of Hesse includes both the State of Hesse and the area known as Rhenish Hesse in the neighbouring Rhineland-Palatinate state...

discussed the question with Bucer in Kassel

Kassel

Kassel is a town located on the Fulda River in northern Hesse, Germany. It is the administrative seat of the Kassel Regierungsbezirk and the Kreis of the same name and has approximately 195,000 inhabitants.- History :...

, at the end of 1534. He eagerly labored for an agreement, for his patristic studies and the Dialogue (1530) of Œcolampadius

Johannes Oecolampadius

Johannes Œcolampadius was a German religious reformer. His real name was Hussgen or Heussgen .-Life:He was born in Weinsberg, then part of the Electoral Palatinate...

had made him doubt the correctness of Luther's doctrine. Moreover, after the death of Zwingli and the change of the political situation his earlier scruples in regard to a union lost their weight. Bucer did not go so far as to believe with Luther that the true body of Christ in the Lord's Supper is bitten by the teeth, but admitted the offering of the body and blood in the symbols of bread and wine. Melanchthon discussed Bucer's views with the most prominent adherents of Luther; but Luther himself would not agree to a mere veiling of the dispute. Melanchthon's relation to Luther was not disturbed by his work as a mediator, although Luther for a time suspected that Melanchthon was "almost of the opinion of Zwingli"; nevertheless he desired to "share his heart with him."

During his sojourn in Tübingen in 1536 Melanchthon was severely attacked by Cordatus, preacher

Preacher

Preacher is a term for someone who preaches sermons or gives homilies. A preacher is distinct from a theologian by focusing on the communication rather than the development of doctrine. Others see preaching and theology as being intertwined...

in Niemeck, because he had taught that works are necessary for salvation. In the second edition of his Loci (1535) he abandoned his earlier strict doctrine of determinism which went even beyond that of Augustine

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo , also known as Augustine, St. Augustine, St. Austin, St. Augoustinos, Blessed Augustine, or St. Augustine the Blessed, was Bishop of Hippo Regius . He was a Latin-speaking philosopher and theologian who lived in the Roman Africa Province...

, and in its place taught more clearly his so-called Synergism. He repulsed the attack of Cordatus in a letter to Luther and his other colleagues by stating that he had never departed from their common teachings on this subject, and in the Antinomian Controversy of 1537 Melanchthon was in harmony with Luther.

Controversies with Flacius

The last eventful and sorrowful period of his life began with controversies over the Interims and the AdiaphoraAdiaphora

Adiaphoron is a concept of Stoic philosophy that indicates things outside of moral law—that is, actions that morality neither mandates nor forbids....

(1547). It is true, Melanchthon rejected the Augsburg Interim

Augsburg Interim

The Augsburg Interim is the general term given to an imperial decree ordered on May 15, 1548, at the 1548 Diet of Augsburg, after Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, had defeated the forces of the Schmalkaldic League in the Schmalkaldic War of 1546/47...

, which the emperor

Emperor

An emperor is a monarch, usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife or a woman who rules in her own right...

tried to force upon the defeated Protestants; but in the negotiations concerning the so-called Leipzig Interim

Leipzig Interim

The Leipzig Interim was a temporary settlement of 1548 AD in matters of religion, entered into by the Emperor Charles V with the Protestants.The Augsburg Interim of 1548 met with strong opposition. In order to make it less objectionable, a modification was introduced by Melanchthon and other...

he made concessions which many feel can in no way be justified, even if one considers his difficult position, opposed as he was to the elector and the emperor.

In agreeing to various Roman usages, Melanchthon started from the opinion that they are adiaphora

Adiaphora

Adiaphoron is a concept of Stoic philosophy that indicates things outside of moral law—that is, actions that morality neither mandates nor forbids....

if nothing is changed in the pure doctrine and the sacraments which Jesus

Jesus

Jesus of Nazareth , commonly referred to as Jesus Christ or simply as Jesus or Christ, is the central figure of Christianity...

instituted, but he disregarded the position that concessions made under such circumstances have to be regarded as a denial of Evangelical convictions.

Melanchthon himself perceived his faults in the course of time and repented of them, perhaps having to suffer more than was just in the displeasure of his friends and the hatred of his enemies. From now on until his death he was full of trouble and suffering. After Luther's death he became the "theological leader of the German Reformation," not indisputably, however; for the Lutherans with Matthias Flacius

Matthias Flacius

Matthias Flacius Illyricus was a Lutheran reformer.He was born in Carpano, a part of Albona in Istria, son of Andrea Vlacich alias Francovich and Jacobea Luciani, daughter of a wealthy and powerful Albonian family...

at their head accused him and his followers of heresy

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

and apostasy

Apostasy

Apostasy , 'a defection or revolt', from ἀπό, apo, 'away, apart', στάσις, stasis, 'stand, 'standing') is the formal disaffiliation from or abandonment or renunciation of a religion by a person. One who commits apostasy is known as an apostate. These terms have a pejorative implication in everyday...

. Melanchthon bore all accusations and calumnies with admirable patience

Patience

Patience is the state of endurance under difficult circumstances, which can mean persevering in the face of delay or provocation without acting on annoyance/anger in a negative way; or exhibiting forbearance when under strain, especially when faced with longer-term difficulties. Patience is the...

, dignity

Dignity

Dignity is a term used in moral, ethical, and political discussions to signify that a being has an innate right to respect and ethical treatment. It is an extension of the Enlightenment-era concepts of inherent, inalienable rights...

, and self-control.

Disputes with Osiander and Flacius

Andreas Osiander

Andreas Osiander was a German Lutheran theologian.- Career :Born at Gunzenhausen in Franconia, Osiander studied at the University of Ingolstadt before being ordained as a priest in 1520. In the same year he began work at an Augustinian convent in Nuremberg as a Hebrew tutor. In 1522, he was...

Melanchthon satisfied all parties. Melanchthon took part also in a controversy with Stancari, who held that Christ was our justification

Justification (theology)

Rising out of the Protestant Reformation, Justification is the chief article of faith describing God's act of declaring or making a sinner righteous through Christ's atoning sacrifice....

only according to his human nature.

He was also still a strong opponent of the Roman Catholics, for it was by his advice that the elector of Saxony declared himself ready to send deputies to a council to be convened at Trent

Trento

Trento is an Italian city located in the Adige River valley in Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol. It is the capital of Trentino...

, but only under the condition that the Protestants should have a share in the discussions, and that the Pope

Pope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

should not be considered as the presiding officer and judge. As it was agreed upon to send a confession to Trent, Melanchthon drew up the Confessio Saxonica which is a repetition of the Augsburg Confession, discussing, however, in greater detail, but with moderation, the points of controversy with Rome

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

. Melanchthon on his way to Trent at Dresden

Dresden

Dresden is the capital city of the Free State of Saxony in Germany. It is situated in a valley on the River Elbe, near the Czech border. The Dresden conurbation is part of the Saxon Triangle metropolitan area....

saw the military preparations of Maurice of Saxony

Maurice, Elector of Saxony

Maurice was Duke and later Elector of Saxony. His clever manipulation of alliances and disputes gained the Albertine branch of the Wettin dynasty extensive lands and the electoral dignity....

, and after proceeding as far as Nuremberg

Nuremberg

Nuremberg[p] is a city in the German state of Bavaria, in the administrative region of Middle Franconia. Situated on the Pegnitz river and the Rhine–Main–Danube Canal, it is located about north of Munich and is Franconia's largest city. The population is 505,664...

, returned to Wittenberg in March 1552, for Maurice had turned against the emperor. Owing to his act, the condition of the Protestants became more favorable and were still more so at the Peace of Augsburg

Peace of Augsburg

The Peace of Augsburg, also called the Augsburg Settlement, was a treaty between Charles V and the forces of the Schmalkaldic League, an alliance of Lutheran princes, on September 25, 1555, at the imperial city of Augsburg, now in present-day Bavaria, Germany.It officially ended the religious...

(1555), but Melanchthon's labors and sufferings increased from that time.

The last years of his life were embittered by the disputes over the Interim and the freshly started controversy on the Lord's Supper. As the statement "good works are necessary for salvation" appeared in the Leipzig Interim, its Lutheran opponents attacked in 1551 Georg Major

Georg Major

George Major was a Lutheran theologian of the Protestant Reformation. He was born in Nuremberg and died at Wittenberg.-Life:...

, the friend and disciple of Melanchthon, so Melanchthon dropped the formula altogether, seeing how easily it could be misunderstood.

But all his caution and reservation did not hinder his opponents from continually working against him, accusing him of synergism and Zwinglianism. At the Colloquy of Worms

Colloquy of Worms

The Colloquy of Worms was the last colloquy in the 16th century on an imperial level, held in Worms from September 11 to October 8, 1557. At the Diet of Augsburg in 1555 it had been agreed that the dialog on controversial religious issues should be continued. A resolution was passed at Regensburg...

in 1557 which he attended only reluctantly, the adherents of Flacius and the Saxon theologians tried to avenge themselves by thoroughly humiliating Melanchthon, in agreement with the malicious desire of the Roman Catholics to condemn all heretics

Heresy

Heresy is a controversial or novel change to a system of beliefs, especially a religion, that conflicts with established dogma. It is distinct from apostasy, which is the formal denunciation of one's religion, principles or cause, and blasphemy, which is irreverence toward religion...

, especially those who had departed from the Augsburg Confession, before the beginning of the conference. As this was directed against Melanchthon himself, he protested, so that his opponents left, greatly to the satisfaction of the Roman Catholics who now broke off the colloquy, throwing all blame upon the Protestants. The Reformation in the sixteenth century did not experience a greater insult, as Nietzsche says.

Nevertheless, Melanchthon persevered in his efforts for the peace of the Church, suggesting a synod

Synod

A synod historically is a council of a church, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. In modern usage, the word often refers to the governing body of a particular church, whether its members are meeting or not...

of the Evangelical party and drawing up for the same purpose the Frankfurt Recess, which he defended later against the attacks of his enemies.

More than anything else the controversies on the Lord's Supper embittered the last years of his life. The renewal of this dispute was due to the victory in the Reformed Church of the Calvinistic

Calvinism

Calvinism is a Protestant theological system and an approach to the Christian life...

doctrine and its influence upon Germany. To its tenets Melanchthon never gave his assent, nor did he use its characteristic formulas. The personal presence and self-impartation of Christ in the Lord's Supper were especially important for Melanchthon; but he did not definitely state how body and blood are related to this. Although rejecting the physical act of mastication

Mastication

Mastication or chewing is the process by which food is crushed and ground by teeth. It is the first step of digestion and it increases the surface area of foods to allow more efficient break down by enzymes. During the mastication process, the food is positioned between the teeth for grinding by...

, he nevertheless assumed the real presence of the body of Christ and therefore also a real self-impartation. Melanchthon differed from Calvin

John Calvin

John Calvin was an influential French theologian and pastor during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of Christian theology later called Calvinism. Originally trained as a humanist lawyer, he broke from the Roman Catholic Church around 1530...

also in emphasizing the relation of the Lord's Supper to justification.

Marian views

Melanchthon viewed any veneration of saintSaint

A saint is a holy person. In various religions, saints are people who are believed to have exceptional holiness.In Christian usage, "saint" refers to any believer who is "in Christ", and in whom Christ dwells, whether in heaven or in earth...

s rather critically but developed positive commentaries about Mary. In his Annotations in Evangelia commenting on Lk 2,52, he discusses the faith of Mary, “she kept all things in her heart” which to Melanchton is a call to the Church to follow her example. During the marriage at Cana

Marriage at Cana

In Christianity, the transformation of water into wine at the Marriage at Cana or Wedding at Cana is the first miracle of Jesus in the Gospel of John....

, Melanchton points out that Mary went too far, asking for more wine, misusing her position. But she was not upset, when Jesus gently scolded her. Mary was negligent, when she lost her son in the temple, but she did not sin. Mary was conceived with original sin like every other human being, but she was spared the consequences of it. Consequently, Melanchton opposed the feast of the Immaculate Conception

Immaculate Conception

The Immaculate Conception of Mary is a dogma of the Roman Catholic Church, according to which the Virgin Mary was conceived without any stain of original sin. It is one of the four dogmata in Roman Catholic Mariology...

, which in his days, although not dogma, was celebrated in several cities and had been approved at the Council of Basel in 1439. He declared that the Immaculate Conception was an invention of monks. Mary is a representation (Typus) of the Church and in the Magnificat

Magnificat

The Magnificat — also known as the Song of Mary or the Canticle of Mary — is a canticle frequently sung liturgically in Christian church services. It is one of the eight most ancient Christian hymns and perhaps the earliest Marian hymn...

, Mary spoke for the whole Church. Standing under the cross, Mary suffered like no other human being. Consequently Christians have to unite with her under the Cross, in order to become Christ-like.

Death

But before these and other theological dissensions were ended, he died; a few days before this event he committed to writing his reasons for not fearing it. On the left were the words, "Thou shalt be delivered from sins, and be freed from the acrimony and fury of theologians"; on the right, "Thou shalt go to the light, see God, look upon his Son, learn those wonderful mysteries which thou hast not been able to understand in this life." The immediate cause of death was a severe cold which he had contracted on a journey to Leipzig in March, 1560, followed by a fever that consumed his strength, weakened by many sufferings.The only care that occupied him until his last moment was the desolate condition of the Church. He strengthened himself in almost uninterrupted prayer, and in listening to passages of Scripture. Especially significant did the words seem to him, "His own received him not; but as many as received him, to them gave he power to become the sons of God." When Caspar Peucer

Caspar Peucer

Caspar Peucer was a German reformer, physician, and scholar.-Biography:Born in Bautzen, Peucer studied mathematics, astronomy, and medicine at the University of Wittenberg from 1540...

, his son in-law, asked him if he wanted anything, he replied, "Nothing but heaven." His body was laid beside Luther's in the Schloßkirche in Wittenberg.

He is commemorated in the Calendar of Saints

Calendar of Saints (Lutheran)

The Lutheran Calendar of Saints is a listing which details the primary annual festivals and events that are celebrated liturgically by some Lutheran Churches in the United States. The calendars of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America and the Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod are from the...

of the Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod

Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod

The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod is a traditional, confessional Lutheran denomination in the United States. With 2.3 million members, it is both the eighth largest Protestant denomination and the second-largest Lutheran body in the U.S. after the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. The Synod...

on February 16 and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America is a mainline Protestant denomination headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. The ELCA officially came into existence on January 1, 1988, by the merging of three churches. As of December 31, 2009, it had 4,543,037 baptized members, with 2,527,941 of them...

on June 25 (The LCMS commemorates him on his date of birth, and the ELCA on the date of the presentation of the Augsburg Confession

Augsburg Confession

The Augsburg Confession, also known as the "Augustana" from its Latin name, Confessio Augustana, is the primary confession of faith of the Lutheran Church and one of the most important documents of the Lutheran reformation...

).

Estimation of his works and character

Melanchthon's importance for the Reformation lay essentially in the fact that he systematized Luther's ideas, defended them in public, and made them the basis of a religious education. These two, by complementing each other, could be said to have harmoniously achieved the results of the Reformation. Melanchthon was impelled by Luther to work for the Reformation; his own inclinations would have kept him a student. Without Luther's influence Melanchthon would have been "a second Erasmus," although his heart was filled with a deep religious interest in the Reformation. While Luther scattered the sparks among the people, Melanchthon by his humanistic studies won the sympathy of educated people and scholars for the Reformation. Besides Luther's strength of faith, Melanchthon's many-sidedness and calmness, as well as his temperance and love of peace, had a share in the success of the movement.Both men had a clear consciousness of their mutual position and the divine necessity of their common calling. Melanchthon wrote in 1520, "I would rather die than be separated from Luther," whom he afterward compared to Elijah, and called "the man full of the Holy Ghost

Holy Spirit