Martin Bucer

Encyclopedia

Martin Bucer (11 November 1491 – 28 February 1551) was a Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg

who influenced Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican doctrines and practices. Bucer was originally a member of the Dominican Order

, but after meeting and being influenced by Martin Luther

in 1518 he arranged for his monastic vows to be annulled. He then began to work for the Reformation

, with the support of Franz von Sickingen

.

Bucer's efforts to reform the church in Wissembourg

resulted in his excommunication

from the Roman Catholic Church

, and he was forced to flee to Strasbourg. There he joined a team of reformers which included Matthew Zell, Wolfgang Capito, and Caspar Hedio

. He acted as a mediator between the two leading reformers, Martin Luther and Huldrych Zwingli

, who differed on the doctrine of the eucharist

. Later, Bucer sought agreement on common articles of faith such as the Tetrapolitan Confession

and the Wittenberg Concord

, working closely with Philipp Melanchthon

on the latter.

Bucer believed that the Catholics in the Holy Roman Empire

could be convinced to join the Reformation. Through a series of conferences organised by Charles V

, he tried to unite Protestants and Catholics to create a German national church separate from Rome. He did not achieve this, as political events led to the Schmalkaldic War

and the retreat of Protestantism within the Empire. In 1548, Bucer was persuaded, under duress, to sign the Augsburg Interim

, which imposed certain forms of Catholic worship. However, he continued to promote reforms until the city of Strasbourg accepted the Interim, and forced him to leave.

In 1549, Bucer was exiled to England, where, under the guidance of Thomas Cranmer

, he was able to influence the second revision of the Book of Common Prayer

. He died in Cambridge, England, at the age of 59. Although his ministry did not lead to the formation of a new denomination, many Protestant denominations have claimed him as one of their own. He is remembered as an early pioneer of ecumenism

.

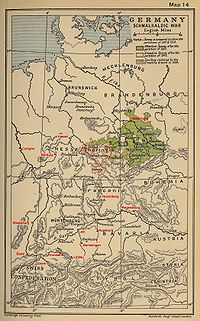

In the 16th century, the Holy Roman Empire

In the 16th century, the Holy Roman Empire

was a centralised state in name only. The Empire was divided into many princely and city states that provided a powerful check on the rule of the Holy Roman Emperor

. The division of power between the emperor and the various states made the Reformation

in Germany possible, as individual states defended reformers within their territories. In the Electorate of Saxony

, Martin Luther

was supported by the elector Frederick III

and his successors John

and John Frederick. Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse

—whose lands lay midway between Saxony and the Rhine—also supported the Reformation, and he figured prominently in the lives of both Luther and Bucer. The Emperor Charles V

had to balance the demands of his imperial subjects. At the same time, he was often distracted by war with France and the Ottoman Empire

and in Italy. The political rivalry among all the players greatly influenced the ecclesiastical developments within the Empire.

In addition to the princely states, free imperial cities

, nominally under the control of the Emperor but really ruled by councils that acted like sovereign governments, were scattered throughout the Empire. As the Reformation took root, clashes broke out in many cities between local reformers and conservative city magistrates. It was in a free imperial city, Strasbourg

, that Martin Bucer began his work. Located on the western frontier of the Empire, Strasbourg was closely allied with the Swiss cities that had thrown off the imperial yoke. Some had adopted a reformed religion distinct from Lutheranism, in which humanist

social concepts and the communal ethic played a greater role. Along with a group of free imperial cities in the south and west of the German lands, Strasbourg followed this pattern of Reformation. It was ruled by a complex local government largely under the control of a few powerful families and wealthy guildsmen. In Bucer's time, social unrest was growing as lower-level artisan

s resented their social immobility and the widening income gap. The citizens may not have planned revolution, but they were receptive to new ideas that might transform their lives.

(Schlettstadt), Alsace

, a free imperial city

of the Holy Roman Empire. His father and grandfather, both named Claus Butzer, were coopers

(barrelmakers) by trade. Almost nothing is known about Bucer's mother. Bucer likely attended Sélestat's prestigious Latin school

, where artisans sent their children. He completed his studies in the summer of 1507 and joined the Dominican order

as a novice

. Bucer later claimed his grandfather had forced him into the order. After a year, he was consecrated as an acolyte

in the Strasbourg church

of the Williamites

, and he took his vows as a full Dominican friar

. In 1510, he was consecrated as a deacon

.

By 1515, Bucer was studying theology in the Dominican monastery in Heidelberg

. The following year, he took a course in dogmatics in Mainz

, where he was ordained

a priest, returning to Heidelberg in January 1517 to enroll in the university. Around this time, he became influenced by humanism

, and he started buying books published by Johannes Froben, some by the great humanist Erasmus

. A 1518 inventory of Bucer's books includes the major works of Thomas Aquinas

, leader of medieval scholasticism

in the Dominican order.

In April 1518, Johannes von Staupitz, the vicar-general of the Augustinians

, invited the Wittenberg

reformer Martin Luther

to argue his theology at the Heidelberg Disputation

. Here Bucer met Luther for the first time. In a long letter to his mentor, Beatus Rhenanus

, Bucer recounted what he learned, and he commented on several of Luther's Ninety-Five Theses. He largely agreed with them and perceived the ideas of Luther and Erasmus to be in concordance. Because meeting Luther posed certain risks, he asked Rhenanus to ensure his letter did not fall into the wrong hands. He also wrote his will, which contains the inventory of his books. In early 1519, Bucer received the baccalaureus degree, and that summer he stated his theological views in a disputation before the faculty at Heidelberg, revealing his break with Aquinas and scholasticism.

The events that caused Bucer to leave the Dominican order arose from his embrace of new ideas and his growing contact with other humanists and reformers. A fellow Dominican, Jacob van Hoogstraaten

The events that caused Bucer to leave the Dominican order arose from his embrace of new ideas and his growing contact with other humanists and reformers. A fellow Dominican, Jacob van Hoogstraaten

, the grand inquisitor

of Cologne

, tried to prosecute Johann Reuchlin

, a humanist scholar. Other humanists, including the nobles Ulrich von Hutten

and imperial knight

Franz von Sickingen

, took Reuchlin's side. Hoogstraten was thwarted, but he now planned to target Bucer. On 11 November 1520, Bucer told the reformer Wolfgang Capito in a letter that Hoogstraaten was threatening to make an example of him as a follower of Luther. To escape Dominican jurisdiction, Bucer needed to be freed of his monastic vows. Capito and others were able to expedite the annulment of his vows, and on 29 April 1521 he was formally released from the Dominican order.

For the next two years, Bucer was protected by Sickingen and Hutten. He also worked for a time at the court of Ludwig V, Elector Palatine

, as chaplain to Ludwig's younger brother Frederick. Sickingen was a senior figure at Ludwig's court. This appointment enabled Bucer to live in Nuremberg

, the most powerful city of the Empire, whose governing officials were strongly reformist. There he met many people who shared his viewpoint, including the humanist Willibald Pirckheimer

and the future Nuremberg reformer Andreas Osiander

. In September 1521, Bucer accepted Sickingen's offer of the position of pastor at Landstuhl

, where Sickingen had a castle, and Bucer moved to the town in May 1522. In summer 1522, he met and married Elisabeth Silbereisen, a former nun.

Sickingen also offered to pay for Bucer to study in Wittenberg. On his way, Bucer stopped in the town of Wissembourg

, whose leading reformer, Heinrich Motherer, asked him to become his chaplain. Bucer agreed to interrupt his journey and went to work immediately, preaching daily sermons in which he attacked traditional church practices and monastic orders. On the basis of his belief that the Bible was the sole source for knowledge to attain salvation (sola scriptura

), he preached that the mass should not be considered as the recrucifying of Christ, but rather the reception of God's gift of salvation through Christ. He accused the monks of creating additional rules above what is contained in the Bible. He summarised his convictions in six theses, and called for a public disputation. His opponents, the local Franciscans and Dominicans, ignored him, but his sermons incited the townspeople to threaten the town's monasteries. The bishop of Speyer

reacted by excommunicating

Bucer, and although the town council continued to support him, events beyond Wissembourg left Bucer in danger. His leading benefactor, Franz von Sickingen, was defeated and killed during the Knight's Revolt, and Ulrich von Hutten became a fugitive. The Wissembourg council urged Bucer and Motherer to leave, and on 13 May 1523 they fled to nearby Strasbourg.

reformer, Huldrych Zwingli

, pleading for a safe post in Switzerland. Fortunately for Bucer, the Strasbourg council was under the influence of the reformer, Matthew Zell; during Bucer's first few months in the city he worked as Zell's unofficial chaplain and was able to give classes on books of the Bible. The largest guild in Strasbourg, the Gärtner or Gardeners, appointed him as its pastor on 24 August 1523. A month later the council accepted his application for citizenship.

In Strasbourg, Bucer joined a team of notable reformers: Zell, who took the role of the preacher to the masses; Wolfgang Capito, the most influential theologian in the city; and Caspar Hedio

In Strasbourg, Bucer joined a team of notable reformers: Zell, who took the role of the preacher to the masses; Wolfgang Capito, the most influential theologian in the city; and Caspar Hedio

, the cathedral preacher. One of Bucer's first actions in the cause of reform was to debate with Thomas Murner

, a monk who had attacked Luther in satires. While the city council vacillated on religious issues, the number of people supporting the Reformation and hostile towards the traditional clergy had grown.

The hostility reached a boiling point when Conrad Treger, the prior provincial

of the Augustinians

, denounced the reformist preachers and the burghers

of Strasbourg as heretics. On 5 September 1524, angry mobs broke into the monasteries, looting and destroying religious images. Many opponents of the Reformation were arrested, including Treger. After the council requested an official statement from the reformers, Bucer drafted twelve articles summarising the teachings of the Reformation, including justification by faith (sola fide). He rejected the mass

and Catholic

concepts such as monastic vows, veneration

of saints, and purgatory

. He refused to recognise the authority of the pope and instead emphasised obedience to the government. Treger was released on 12 October and left Strasbourg. With his departure, overt opposition to the Reformation ended in the city.

The reformers' first goal was the creation of a new order of service

—at this time the Strasbourg reformers followed Zwingli's liturgy. They presented proposals for a common order of service for the entire Reformation movement to the theologians of Wittenberg and Zürich. In Bucer's booklet Grund und Ursach (Basis and Cause), published in December 1524, he attacked the idea of the mass as a sacrifice, and rejected liturgical garments

, the altar

, and any form of ritual. By May 1525, reforms had been implemented in Strasbourg's parish churches, but the city council decided to allow masses to continue in the cathedral

and in the collegiate church

es St Thomas'

, Young St Peter's

, and Old St Peter's.

. In this dispute, he attempted to mediate between Martin Luther and Huldrych Zwingli. The two theologians disagreed on whether the body and blood of Christ were truly present within the elements of bread and wine during the celebration of the Lord's Supper. Luther believed in the real presence

of Christ; and Zwingli believed in a symbolic presence. By late 1524, Bucer had abandoned the idea of the real presence and, after some exegetical

studies, accepted Zwingli's interpretation. However, he did not believe the Reformation depended on either position but on faith in Christ, other matters being secondary. In this respect he differed from Zwingli.

In March 1526, Bucer published Apologia, defending his views. He proposed a formula that he hoped would satisfy both sides: different understandings of scripture were acceptable, and church unity was assured so long as both sides had a "child-like faith in God". Bucer stated that his and Zwingli's interpretation on the eucharist was the correct one, but while he considered the Wittenberg theologians to be in error, he accepted them as brethren as they agreed on the fundamentals of faith. He also published two translations of works by Luther and Johannes Bugenhagen

In March 1526, Bucer published Apologia, defending his views. He proposed a formula that he hoped would satisfy both sides: different understandings of scripture were acceptable, and church unity was assured so long as both sides had a "child-like faith in God". Bucer stated that his and Zwingli's interpretation on the eucharist was the correct one, but while he considered the Wittenberg theologians to be in error, he accepted them as brethren as they agreed on the fundamentals of faith. He also published two translations of works by Luther and Johannes Bugenhagen

, interpolating his own interpretation of the Lord's Supper into the text. This outraged the Wittenberg theologians and damaged their relations with Bucer. In 1528, when Luther published Vom Abendmahl Christi, Bekenntnis (Confession Concerning Christ's Supper

), detailing Luther's concept of the sacramental union

, Bucer responded with a treatise

of his own, Vergleichnung D. Luthers, und seins gegentheyls, vom Abendmal Christi (Conciliation between Dr. Luther and His Opponents Regarding Christ's Supper). It took the form of a dialogue between two merchants, one from Nuremberg who supported Luther and the other from Strasbourg who supported Bucer, with the latter winning over his opponent. Bucer noted that as Luther had rejected impanation

, the idea that Christ was "made into bread", there was no disagreement between Luther and Zwingli; both believed in a spiritual presence of Christ in the eucharist. Luther harshly rejected Bucer's interpretation.

During this time, Bucer and Zwingli remained in close touch, discussing other aspects of theology and practice such as the use of religious images and the liturgy. Bucer did not hesitate to disagree with Zwingli on occasion, although unity between Strasbourg and the Swiss churches took priority over such differences. In 1527, Bucer and Capito attended a disputation in Bern to decide whether the city should accept reformed doctrines and practices. Bucer provided strong support for Zwingli's leading role in the disputation, which finally brought the Reformation to Bern.

The last meeting between Zwingli and Luther was at the Marburg Colloquy

of October 1529, organised by Philip of Hesse and attended by various leading reformers, including Bucer. Luther and Zwingli agreed on 13 of the 14 topics discussed, but Zwingli did not accept the doctrine of the real presence, on which Luther would not compromise. After the discussion broke down between the two, Bucer tried to salvage the situation, but Luther noted, "It is obvious that we do not have one and the same spirit." The meeting ended in failure. The following year, Bucer wrote of his disappointment at doctrinal inflexibility:

Charles V

asked them to present their views to him in 1530 at the Diet of Augsburg

. Philipp Melanchthon

, the main delegate from Wittenberg, quickly prepared the draft that eventually became the Augsburg Confession

. The Wittenberg theologians rejected attempts by Strasbourg to adopt it without the article on the Lord's Supper. In response, Bucer wrote a new confession, the Confessio Tetrapolitana (Tetrapolitan Confession

), so named because only four cities adopted it, Strasbourg and three other southern German cities, Konstanz

, Memmingen

, and Lindau

. A copy of Melanchthon's draft was used as the starting point and the only major change was the wording on the article on the eucharist.

Charles, however, decreed on 22 September that all reformers must reconcile with the Catholic faith, or he would use military force to suppress them. This prompted Melanchthon to call a meeting with Bucer and after lengthy discussions they agreed on nine theses, which they sent to Luther and to Strasbourg. The Strasbourg magistrates forwarded them to Basel

and Zürich. Bucer met Luther in Coburg

on 26–28 September. Luther still rejected Bucer's theses, but he encouraged him to continue the search for unity. Bucer then travelled to several southern German cities, including Ulm

, Isny, Konstanz, Memmingen, and Lindau, and to the Swiss cities of Basel and Zürich. In Zurich on 12 October, he presented the articles to Zwingli, who neither opposed him nor agreed with him.

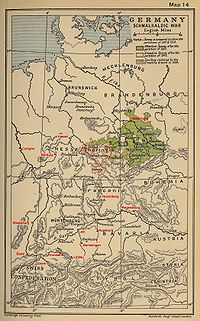

In February 1531, the evangelical princes and cities of the empire set up the Protestant Schmalkaldic League

to defend the reformed religion. Strasbourg's Jakob Sturm

negotiated the city's inclusion on the basis of the Tetrapolitan Confession. By this time, Bucer's relationship with Zwingli was deteriorating. Strasbourg's political ties with the Elector of Saxony, and Bucer's partial theological support of Luther, became too much for Zwingli, and on 21 February 1531, he wrote to Bucer ending their friendship. When representatives of the southern German cities convened in Ulm on 23–24 March 1532 to discuss their alliance with the Schmalkaldic League, Bucer advised them to sign the Augsburg Confession, if they were being pressured to do so. For Bucer to recommend the rival confession over his own version surprised the Swiss cities. Luther continued his polemical attacks on Bucer, but Bucer was unperturbed: "In any case, we must seek unity and love in our relationships with everyone," he wrote, "regardless of how they behave toward us." In April and May 1533, he again toured the southern German cities and Swiss cities. The latter remained unconvinced and did not join the Protestant alliance.

(Christian Federation), the council systematically removed images and side altars from the churches. Bucer had at first tolerated images in places of worship as long as they were not venerated. He later came to believe they should be removed because of their potential for abuse, and he advocated in a treatise for their orderly removal. First the authority of the magistrates should be obtained, and then the people instructed on abandoning devotion to images.

Bucer's priority in Strasbourg was to instil moral discipline in the church. To this end, special wardens (Kirchenpfleger), chosen from among the laity, were assigned to each congregation to supervise both doctrine and practice. His concerns were motivated by the effects of a rapidly rising refugee population, attracted by Strasbourg's tolerant asylum policies. Influxes of refugees, particularly after 1528, had brought a series of revolutionary preachers into Strasbourg. These men were inspired by a variety of apocalyptic

and mystical doctrines, and in some cases by hostility towards the social order and the notion of an official church. Significant numbers of refugees were Anabaptists and spiritualists, such as the followers of Melchior Hoffman

, Caspar Schwenckfeld, and Clemens Ziegler. Bucer personally took responsibility for attacking these and other popular preachers to minimise their influence and secure their expulsion and that of their followers. On 30 November 1532, the pastors and wardens of the church petitioned the council to enforce ethical standards, officially sanction the reformed faith, and refute the "sectarian" doctrines. The ruling authorities, who had allowed sectarian congregations to thrive among the refugees and lower orders, would only expel the obvious troublemakers. Bucer insisted that the council urgently take control of all Christian worship in the city for the common good.

In response to the petition, the council set up a commission that proposed a city synod

. For this gathering, Bucer provided a draft document of sixteen articles on church doctrine. The synod convened on 3 June 1533 at the Church of the Penitent Magdalens

to debate Bucer's text, eventually accepting it in full. Sectarian leaders were brought before the synod and questioned by Bucer. Ziegler was dismissed and allowed to stay in Strasbourg; Hoffmann was imprisoned as a danger to the state; and Schwenckfeld left Strasbourg of his own accord.

Following the synod, the city council dragged its heels for several months. The synod commission, which included Bucer and Capito, decided to take the initiative and produced a draft ordinance for the regulation of the church. It proposed that the council assume almost complete control of the church, with responsibility for supervising doctrine, appointing church wardens, and maintaining moral standards. Still the council delayed, driving the pastors to the brink of resignation. Only when Hoffman's followers seized power in Münster, in the Münster Rebellion

, did the council act, fearing a similar incident in Strasbourg. On 4 March 1534, the council announced that Bucer's Tetrapolitan Confession and his sixteen articles on church doctrine were now official church statements of faith. All Anabaptists should either subscribe to these documents or leave the city. The decision established a new church in Strasbourg, with Capito declaring, "Bucer is the bishop of our church."

By 1534, Bucer was a key figure in the German Reformation. He repeatedly led initiatives to secure doctrinal agreement between Wittenberg, the south German cities, and Switzerland. In December 1534, Bucer and Melanchthon held productive talks in Kassel

By 1534, Bucer was a key figure in the German Reformation. He repeatedly led initiatives to secure doctrinal agreement between Wittenberg, the south German cities, and Switzerland. In December 1534, Bucer and Melanchthon held productive talks in Kassel

, and Bucer then drafted ten theses that the Wittenberg theologians accepted. In October 1535, Luther suggested a meeting in Eisenach

to conclude a full agreement among the Protestant factions. Bucer persuaded the south Germans to attend, but the Swiss, led by Zwingli's successor Heinrich Bullinger

, were skeptical of his intentions. Instead they met in Basel on 1 February 1536 to draft their own confession of faith. Bucer and Capito attended and urged the Swiss to adopt a compromise wording on the eucharist that would not offend the Lutherans. The true presence of Christ was acknowledged while a natural or local union between Christ and the elements was denied. The result was the First Helvetic Confession, the success of which raised Bucer's hopes for the upcoming meeting with Luther.

The meeting, moved to Wittenberg because Luther was ill, began on 21 May 1536. To the surprise of the south Germans, Luther began by attacking them, demanding that they recant their false understanding of the eucharist. Capito intervened to calm matters, and Bucer claimed that Luther had misunderstood their views on the issue. The Lutherans insisted that unbelievers who partake of the eucharist truly receive the body and blood of Christ. Bucer and the south Germans believed that they receive only the elements of the bread and the wine. Johannes Bugenhagen

formulated a compromise, approved by Luther, that distinguished between the unworthy (indigni) and the unbelievers (impii). The south Germans accepted that the unworthy receive Christ, and the question of what unbelievers receive was left unanswered. The two sides then worked fruitfully on other issues and on 28 May signed the Wittenberg Concord

. Strasbourg quickly endorsed the document, but much coaxing from Bucer was required before he managed to convince all the south German cities. The Swiss cities were resistant, Zürich in particular. They rejected even a mild statement suggesting a union of Christ with the elements of the eucharist. Bucer advised the Swiss to hold a national synod to decide on the matter, hoping he could at least persuade Bern and Basel. The synod met in Zürich from 28 May to 4 April 1538, but Bucer failed to win over a single city. The Swiss never accepted or rejected the Wittenberg Concord.

Bucer's influence on the Swiss was eventually felt indirectly. In summer 1538, he invited John Calvin

, the future reformer of Geneva

, to lead a French refugee congregation in Strasbourg. Bucer and Calvin had much in common theologically and maintained a long friendship. The extent to which Bucer influenced Calvin is an open question among modern scholars, but many of the reforms that Calvin later implemented in Geneva, including the liturgy and the church organisation, were originally developed in Strasbourg.

In November 1539, Philip asked Bucer to produce a theological defence of bigamy, since he had decided to contract a bigamous

marriage. Bucer reluctantly agreed, on condition the marriage be kept secret. Bucer consulted Luther and Melanchthon, and the three reformers presented Philip with a statement of advice (Wittenberger Ratschlag); later, Bucer produced his own arguments for and against bigamy. Although the document specified that bigamy could be sanctioned only under rare conditions, Philip took it as approval for his marriage to a lady-in-waiting

of his sister. When rumours of the marriage spread, Luther told Philip to deny it, while Bucer advised him to hide his second wife and conceal the truth. Some scholars have noted a possible motivation for this notorious advice: the theologians believed they had advised Philip as a pastor would his parishioner, and that a lie was justified to guard the privacy of their confessional counsel. The scandal that followed the marriage caused Philip to lose political influence, and the Reformation within the Empire was severely compromised.

was convened in Leipzig

to discuss potential reforms within the Duchy. Electoral Saxony sent Melanchthon, and Philip of Hesse sent Bucer. The Duchy itself was represented by Georg Witzel

, a former Lutheran who had reconverted to Catholicism. In discussions from 2 to 7 January 1539, Bucer and Witzel agreed to defer controversial points of doctrine, but Melanchthon withdrew, feeling that doctrinal unity was a prerequisite of a reform plan. Bucer and Witzel agreed on fifteen articles covering various issues of church life. Bucer, however, made no doctrinal concessions: he remained silent on critical matters such as the mass and the papacy. His ecumenical approach provoked harsh criticism from other reformers.

In the Truce of Frankfurt

In the Truce of Frankfurt

of 1539, Charles and the leaders of the Schmalkaldic League agreed on a major colloquy to settle all religious issues within the Empire. Bucer placed great hopes on this meeting: he believed it would be possible to convince most German Catholics to accept the doctrine of sola fide

as the basis for discussions on all other issues. Under various pseudonyms, he published tracts promoting a German national church. A conference in Haguenau

began on 12 June 1540, but during a month's discussion the two sides failed to agree on a common starting point. They decided to reconvene in Worms

. Melanchthon led the Protestants, with Bucer a major influence behind the scenes. When the colloquy again made no progress, the imperial chancellor, Nicholas Perrenot de Granvelle, called for secret negotiations. Bucer then began working with Johannes Gropper, a delegate of the archbishop of Cologne, Hermann von Wied. Aware of the risks of such apparent collusion, he was determined to forge unity among the German churches. The two agreed on twenty-three articles in which Bucer conceded some issues toward the Catholic position. These included justification, the sacraments, and the organisation of the church. Four disputed issues were left undecided: veneration of the saints, private masses

, auricular confession

, and transubstantiation

. The results were published in the "Worms Book", which they confidentially presented to a prince on each side of the religious divide: Philip of Hesse and Joachim II, Elector of Brandenburg.

The Worms Book laid the groundwork for final negotiations at the Diet of Regensburg in 1541. Charles created a small committee, consisting of Johannes Eck

, Gropper, and Julius Pflug on the Catholic side and Melanchthon, Bucer, and Johannes Pistorius on the Protestant side. The basis for discussion was the "Regensburg Book"—essentially the Worms Book with modifications by the papal legate

, Gasparo Contarini

, and other Catholic theologians. The two sides made a promising start, reaching agreement over the issue of justification by faith. But they could not agree on the teaching authority of the Church, the Protestants insisting it was the Bible, the Catholics the magisterium

—in other words, the pope and his bishops. Into the article on the mass and the Lord's Supper, Contarini had inserted the concept of transubstantiation, which was also unacceptable to the Protestants. As a result, the colloquy became deadlocked. To salvage some of the agreements reached, Charles and Granvelle had the Regensburg Book reprinted with additional articles in which the Protestants were allowed to present their views. However, Luther in Wittenberg and the papal court in Rome had by this time seen the book, and they both publicly rejected the article on justification by faith. The failure of the conference was a major setback for Bucer.

After Bucer's return from Regensburg, the city of Strasbourg was struck by the plague

. First, Bucer's friend and colleague Wolfgang Capito succumbed to the disease; then Bucer's wife Elisabeth died on 16 November 1541. How many children Elisabeth had borne is unknown; several died during child-birth or at a young age. One son, Nathanael, although mentally and physically handicapped, survived to adulthood and remained with the Bucer family throughout his life. During Elisabeth's final hours, she urged Bucer to marry Capito's widow, Wibrandis Rosenblatt

, after her death. He married Rosenblatt on 16 April 1542, as her fourth husband—she had outlived Ludwig Keller, Johannes Oecolampadius

, and Wolfgang Capito. She brought with her four children from her previous marriages. The new couple produced a daughter, whom they named Elisabeth.

, archbishop-elector of Cologne, to discuss the introduction of church reform in his archdiocese. As one of the seven electors of the Holy Roman Empire, the archbishop of Cologne was a key political figure for both the emperor and the reformers. After consulting the territorial diet

, the archbishop enlisted Bucer to lead the reform, and on 14 December Bucer moved to Bonn

, the capital of the electorate. His selection caused consternation in the Cologne cathedral chapter

, the clerics assisting the archbishop. The hostility of the clergy soon caused a rift between Bucer and Gropper. On 19 December, the chapter lodged a formal protest against Bucer's appointment, but von Wied supported his new protégé and Bucer was allowed to stay. He led a small congregation at Bonn cathedral

, where he preached three times a week, although his main responsibility was to plan reform.

In January 1543, Bucer began work on a major document for von Wied, Einfältiges Bedenken, worauf eine christliche, im Worte Gottes gegründete Reformation ... anzurichten sei (Simple Consideration Concerning the Establishment of a Christian Reformation Founded upon God's Word). Melanchthon joined him in Bonn in May, and Caspar Hedio a month later, to help draft the document. At the beginning of July, Bucer discussed the draft with the archbishop, who, after studying it, submitted the document to the territorial diet on 23 July. Although the cathedral chapter flatly rejected it, the diet ruled in favour of the reform programme. The final document was over three hundred pages and covered a number of subjects on doctrine, church law, and liturgy. Some of the principles proposed include justification by faith, the acceptance of baptism and the Lord's Supper as the only valid sacraments, the offering of the cup to the laity, the holding of worship services in the vernacular, and the authorisation of priests to marry.

These first steps toward reform were halted on 17 August 1543 when Charles V and his troops entered Bonn. The emperor was engaged in a harsh campaign to assert his claim over lands contested by Wilhelm, Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg

. Bucer was forced to return to Strasbourg shortly afterwards. When the anti-reformist Cologne cathedral chapter and the University of Cologne

appealed to both emperor and pope for protection against their archbishop, Charles took their side. Bucer wrote several treatises defending von Wied's reformation plan, including a six-hundred-page book, Beständige Verantwortung (Steadfast Defence), but he was unable to influence the course of events. Von Wied was excommunicated on 16 April 1546, and he formally surrendered his electoral titles on 25 February 1547. Bucer's congregation in Bonn wrote to him in dismay at this disaster. Bucer reassured them that Christians who humble themselves before God eventually receive his protection.

in 1546, Protestants began a gradual retreat within the Empire. On 21 March 1547, Strasbourg surrendered to the imperial army, and the following month the decisive imperial victory at the Battle of Mühlberg

ended most Protestant resistance. In Strasbourg, Bucer and his colleagues, including Matthew Zell, Paul Fagius

and Johannes Marbach, continued to press the council to bring more discipline and independence to the church. Charles V overruled their efforts at the Diet of Augsburg

, which sat from September 1547 to May 1548. The Diet produced an imperial decree, the provisional Augsburg Interim

, which imposed Catholic rites and ceremonies throughout the Empire, with a few concessions to the Reformation. To make the document acceptable to the Protestants, Charles needed a leading figure among the reformers to endorse it, and he selected Bucer.

Bucer arrived in Augsburg on 30 March 1548 of his own volition. On 2 April, after he was shown the document, he announced his willingness to ratify it if certain changes were made; but the time for negotiations had passed, and Charles insisted on his signature. When he refused, he was placed under house arrest on 13 April, and shortly afterwards in close confinement. On 20 April, he signed the Interim and was immediately freed.

Despite this capitulation, Bucer continued to fight. On his return to Strasbourg, he stepped up his attacks on Catholic rites and ceremonies, and on 2 July published the Ein Summarischer vergriff der Christlichen Lehre und Religion (Concise Summary of Christian Doctrine and Religion), a confessional statement calling on Strasbourg to repent and to defend reformed principles outlined in twenty-nine articles. Charles ordered all copies destroyed. Tension grew in Strasbourg, as Bucer's opponents feared he was leading the city to disaster. Many Strasbourg merchants left to avoid a potential clash with imperial forces. On 30 August, the guild officials voted overwhelmingly to begin negotiations to introduce the Interim. Bucer stood firm; even after the city of Konstanz surrendered and accepted the Interim, he called for Strasbourg to reject it unconditionally. In January 1549, with plans underway for the implementation of the Interim in Strasbourg, Bucer and his colleagues continued to attack it, producing a memorandum on how to preserve the Protestant faith under its directives. With no significant support left, Bucer and Fagius were finally relieved of their positions and dismissed on 1 March 1549. Bucer left Strasbourg on 5 April a refugee, as he had arrived twenty-five years earlier.

Bucer received several offers of sanctuary, including Melanchthon's from Wittenberg and Calvin's from Geneva. He accepted Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

Bucer received several offers of sanctuary, including Melanchthon's from Wittenberg and Calvin's from Geneva. He accepted Archbishop Thomas Cranmer

's invitation to come to England; from his correspondence with several notable Englishmen, he believed that the English Reformation

had advanced with some success. On 25 April 1549 Bucer, Fagius, and others arrived in London, where Cranmer received them with full honours. A few days later, Bucer and Fagius were introduced to Edward VI

and his court. Bucer's wife Wibrandis and his stepdaughter Agnes Capito (daughter of Wolfgang Capito) joined him in September. The following year, Wibrandis arranged for the rest of her children and her elderly mother to come to England.

Bucer took the position of Regius Professor of Divinity

at the University of Cambridge

. In June he entered a controversy when Peter Martyr

, another refugee who had taken the equivalent Regius Professor position at Oxford University

, debated with Catholic colleagues over the issue of the Lord's Supper. Martyr asked Bucer for his support, but Bucer did not totally agree with Martyr's position and thought that exposure of differences would not assist the cause of reform. Unwilling to see the eucharist conflict repeat itself in England, he told Martyr he did not take sides, Catholic, Lutheran, or Zwinglian. He said, "We must aspire with the utmost zeal to edify as many people as we possibly can in faith and in the love of Christ—and to offend no one."

In 1550, another conflict arose when John Hooper

, the new bishop of Gloucester

, refused to don the traditional clothes for his consecration. The vestments controversy

pitted Cranmer, who supported the wearing of clerical garments, against Hooper, Martyr and Jan Laski

, the pastor of the Stranger church in London. As it was known that Bucer had reformed the church services in Strasbourg to emulate the simplicity of the early church, Hooper expected Bucer's support. However, Bucer tried to stay out of the fray, arguing that there were more important issues to deal with—lack of pastors and pastoral care, the need for catechismal instruction, and the implementation of church discipline. Hooper refused to be swayed, and was imprisoned in the Tower of London

until he accepted Cranmer's demand.

Bucer had ambitious goals in diffusing the Reformation throughout England. He was disappointed, therefore, when those in power failed to consult him in bringing about change. On learning about the custom of presenting a memorandum to the king every new year, he worked on a major treatise which he gave as a draft to his friend John Cheke

Bucer had ambitious goals in diffusing the Reformation throughout England. He was disappointed, therefore, when those in power failed to consult him in bringing about change. On learning about the custom of presenting a memorandum to the king every new year, he worked on a major treatise which he gave as a draft to his friend John Cheke

on 21 October 1550. The De Regno Christi (On the Kingdom of Christ) was the culmination of Bucer's many years of experience, a summary of his thought and theology that he described as his legacy. In it he urged Edward VI to take control of the English Reformation, and proposed that Parliament introduce fourteen laws of reform, covering both ecclesiastical and civil matters. In his view the Reformation was not only concerned with the church, but in all areas of life. Noting the difficult social conditions in England, he promoted the role of deacons to care for the poor and needy. He described marriage as a social contract rather than a sacrament, hence he permitted divorce, a modern idea that was considered too advanced for its time. He advocated the restructuring of economic and administrative systems with suggestions for improving industry, agriculture, and education. His ideal society was distinctively authoritarian, with a strong emphasis on Christian discipline. The De Regno Christi was never to be the charter of the English Reformation that Bucer intended: it was finally printed not in England but in Basel, in 1557.

Bucer's last major contribution to the English Reformation was a treatise on the original 1549 edition of the Book of Common Prayer

. Cranmer had requested his opinion on how the book should be revised, and Bucer submitted his response on 5 January 1551. He called for the simplification of the liturgy, noting non-essential elements: certain holidays in the liturgical calendar, actions of piety

such as genuflections, and ceremonies such as private masses. He focused on the congregation and how the people would worship and be taught. How far Bucer's critique influenced the 1552 second edition of the Prayer Book is unknown. Scholars agree that although Bucer's impact on the Church of England should not be overestimated, he exercised his greatest influence on the revision of the Prayer Book.

and Matthew Parker

as executors, commended his loved ones to Thomas Cranmer, and thanked his stepdaughter Agnes Capito for taking care of him. On 28 February, after encouraging those near him to do all they could to realise his vision as expressed in De Regno Christi, he died at the age of 59. He was buried in the church of Great St Mary's in Cambridge

before a large crowd of university professors and students.

In a letter to Peter Martyr, John Cheke wrote a fitting eulogy:

Bucer left his wife Wibrandis a significant inheritance consisting mainly of the household and his large collection of books. She eventually returned to Basel, where she died on 1 November 1564 at the age of 60.

When Mary I

came to the throne, she had Bucer and Fagius tried posthumously for heresy as part of her efforts to restore Catholicism in England. Their caskets were disinterred and their remains burned, along with copies of their books. On 22 July 1560, Elizabeth I

formally rehabilitated both reformers. A brass plaque on the floor of Great St Mary's marks the original location of Bucer's grave.

After Bucer's death, his writings continued to be translated, reprinted, and disseminated throughout Europe. No "Buceran" denomination, however, emerged from his ministry, probably because he never developed a systematic theology as Melanchthon had for the Lutheran church and Calvin for the Reformed churches

. Several groups, including Anglicans, Puritans, Lutherans, and Calvinists, claimed him as one of their own. The adaptability of his theology to each confessional point-of-view also led polemicists to criticise it as too accommodating. His theology could be best summarised as being practical and pastoral rather than theoretical. Bucer was not so concerned about staking a doctrinal claim per se, but rather he took a standpoint in order to discuss and to win over his opponents. At the same time his theological stand was grounded in the conditions of his time where he envisioned the ideal society to be one that was led by an enlightened, God-centred government with all the people united under Christian fellowship. Martin Bucer is chiefly remembered for his promotion of doctrinal unity, or ecumenism

, and his lifelong struggle to create an inclusive church.

Strasbourg

Strasbourg is the capital and principal city of the Alsace region in eastern France and is the official seat of the European Parliament. Located close to the border with Germany, it is the capital of the Bas-Rhin département. The city and the region of Alsace are historically German-speaking,...

who influenced Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican doctrines and practices. Bucer was originally a member of the Dominican Order

Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers , after the 15th century more commonly known as the Dominican Order or Dominicans, is a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Dominic and approved by Pope Honorius III on 22 December 1216 in France...

, but after meeting and being influenced by Martin Luther

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

in 1518 he arranged for his monastic vows to be annulled. He then began to work for the Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

, with the support of Franz von Sickingen

Franz von Sickingen

Franz von Sickingen was a German knight, one of the most notable figures of the first period of the Reformation.-Biography:He was born at Ebernburg near Bad Kreuznach...

.

Bucer's efforts to reform the church in Wissembourg

Wissembourg

Wissembourg is a commune in the Bas-Rhin department in Alsace in northeastern France.It is situated on the little River Lauter close to the border between France and Germany approximately north of Strasbourg and west of Karlsruhe. Wissembourg is a sub-prefecture of the department...

resulted in his excommunication

Excommunication

Excommunication is a religious censure used to deprive, suspend or limit membership in a religious community. The word means putting [someone] out of communion. In some religions, excommunication includes spiritual condemnation of the member or group...

from the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

, and he was forced to flee to Strasbourg. There he joined a team of reformers which included Matthew Zell, Wolfgang Capito, and Caspar Hedio

Caspar Hedio

Caspar Hedio, was a historian and Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg.- References :...

. He acted as a mediator between the two leading reformers, Martin Luther and Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych Zwingli

Ulrich Zwingli was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland. Born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system, he attended the University of Vienna and the University of Basel, a scholarly centre of humanism...

, who differed on the doctrine of the eucharist

Eucharist

The Eucharist , also called Holy Communion, the Sacrament of the Altar, the Blessed Sacrament, the Lord's Supper, and other names, is a Christian sacrament or ordinance...

. Later, Bucer sought agreement on common articles of faith such as the Tetrapolitan Confession

Tetrapolitan Confession

The Tetrapolitan Confession, also called the Confessio Tetrapolitana, Strasbourg Confession, or Swabian Confession, was the official confession of the followers of Huldrych Zwingli and the first confession of the reformed church...

and the Wittenberg Concord

Wittenberg Concord

Wittenberg Concord , is a religious concordat signed by Reformed and Lutheran theologians and churchmen on May 29, 1536 as an attempted resolution of their differences with respect to the Real Presence of Christ's body and blood in the Eucharist...

, working closely with Philipp Melanchthon

Philipp Melanchthon

Philipp Melanchthon , born Philipp Schwartzerdt, was a German reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, intellectual leader of the Lutheran Reformation, and an influential designer of educational systems...

on the latter.

Bucer believed that the Catholics in the Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

could be convinced to join the Reformation. Through a series of conferences organised by Charles V

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V was ruler of the Holy Roman Empire from 1519 and, as Charles I, of the Spanish Empire from 1516 until his voluntary retirement and abdication in favor of his younger brother Ferdinand I and his son Philip II in 1556.As...

, he tried to unite Protestants and Catholics to create a German national church separate from Rome. He did not achieve this, as political events led to the Schmalkaldic War

Schmalkaldic War

The Schmalkaldic War refers to the short period of violence from 1546 until 1547 between the forces of Emperor Charles I of Spain and V of the Holy Roman Empire, commanded by Don Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, Duke of Alba, and the Lutheran Schmalkaldic League within the domains of the Holy Roman...

and the retreat of Protestantism within the Empire. In 1548, Bucer was persuaded, under duress, to sign the Augsburg Interim

Augsburg Interim

The Augsburg Interim is the general term given to an imperial decree ordered on May 15, 1548, at the 1548 Diet of Augsburg, after Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, had defeated the forces of the Schmalkaldic League in the Schmalkaldic War of 1546/47...

, which imposed certain forms of Catholic worship. However, he continued to promote reforms until the city of Strasbourg accepted the Interim, and forced him to leave.

In 1549, Bucer was exiled to England, where, under the guidance of Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer was a leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He helped build a favourable case for Henry's divorce from Catherine of Aragon which resulted in the separation of the English Church from...

, he was able to influence the second revision of the Book of Common Prayer

Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer is the short title of a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion, as well as by the Continuing Anglican, "Anglican realignment" and other Anglican churches. The original book, published in 1549 , in the reign of Edward VI, was a product of the English...

. He died in Cambridge, England, at the age of 59. Although his ministry did not lead to the formation of a new denomination, many Protestant denominations have claimed him as one of their own. He is remembered as an early pioneer of ecumenism

Ecumenism

Ecumenism or oecumenism mainly refers to initiatives aimed at greater Christian unity or cooperation. It is used predominantly by and with reference to Christian denominations and Christian Churches separated by doctrine, history, and practice...

.

Historical context

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

was a centralised state in name only. The Empire was divided into many princely and city states that provided a powerful check on the rule of the Holy Roman Emperor

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor is a term used by historians to denote a medieval ruler who, as German King, had also received the title of "Emperor of the Romans" from the Pope...

. The division of power between the emperor and the various states made the Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

in Germany possible, as individual states defended reformers within their territories. In the Electorate of Saxony

Electorate of Saxony

The Electorate of Saxony , sometimes referred to as Upper Saxony, was a State of the Holy Roman Empire. It was established when Emperor Charles IV raised the Ascanian duchy of Saxe-Wittenberg to the status of an Electorate by the Golden Bull of 1356...

, Martin Luther

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

was supported by the elector Frederick III

Frederick III, Elector of Saxony

Frederick III of Saxony , also known as Frederick the Wise , was Elector of Saxony from 1486 to his death. Frederick was the son of Ernest, Elector of Saxony and his wife Elisabeth, daughter of Albert III, Duke of Bavaria...

and his successors John

John, Elector of Saxony

John of Saxony , known as John the Steadfast or John the Constant, was Elector of Saxony from 1525 until 1532...

and John Frederick. Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse

Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse

Philip I of Hesse, , nicknamed der Großmütige was a leading champion of the Protestant Reformation and one of the most important of the early Protestant rulers in Germany....

—whose lands lay midway between Saxony and the Rhine—also supported the Reformation, and he figured prominently in the lives of both Luther and Bucer. The Emperor Charles V

Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V was ruler of the Holy Roman Empire from 1519 and, as Charles I, of the Spanish Empire from 1516 until his voluntary retirement and abdication in favor of his younger brother Ferdinand I and his son Philip II in 1556.As...

had to balance the demands of his imperial subjects. At the same time, he was often distracted by war with France and the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

and in Italy. The political rivalry among all the players greatly influenced the ecclesiastical developments within the Empire.

In addition to the princely states, free imperial cities

Free Imperial City

In the Holy Roman Empire, a free imperial city was a city formally ruled by the emperor only — as opposed to the majority of cities in the Empire, which were governed by one of the many princes of the Empire, such as dukes or prince-bishops...

, nominally under the control of the Emperor but really ruled by councils that acted like sovereign governments, were scattered throughout the Empire. As the Reformation took root, clashes broke out in many cities between local reformers and conservative city magistrates. It was in a free imperial city, Strasbourg

Strasbourg

Strasbourg is the capital and principal city of the Alsace region in eastern France and is the official seat of the European Parliament. Located close to the border with Germany, it is the capital of the Bas-Rhin département. The city and the region of Alsace are historically German-speaking,...

, that Martin Bucer began his work. Located on the western frontier of the Empire, Strasbourg was closely allied with the Swiss cities that had thrown off the imperial yoke. Some had adopted a reformed religion distinct from Lutheranism, in which humanist

Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanism was an activity of cultural and educational reform engaged by scholars, writers, and civic leaders who are today known as Renaissance humanists. It developed during the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth centuries, and was a response to the challenge of Mediæval...

social concepts and the communal ethic played a greater role. Along with a group of free imperial cities in the south and west of the German lands, Strasbourg followed this pattern of Reformation. It was ruled by a complex local government largely under the control of a few powerful families and wealthy guildsmen. In Bucer's time, social unrest was growing as lower-level artisan

Artisan

An artisan is a skilled manual worker who makes items that may be functional or strictly decorative, including furniture, clothing, jewellery, household items, and tools...

s resented their social immobility and the widening income gap. The citizens may not have planned revolution, but they were receptive to new ideas that might transform their lives.

Early years (1491–1523)

Martin Bucer was born in SélestatSélestat

Sélestat is a commune in the Bas-Rhin department in Alsace in north-eastern France.In 2006, Sélestat had a total population of 19,459. The Communauté de communes de Sélestat et environs had a total population of 35,397.-Geography:...

(Schlettstadt), Alsace

Alsace

Alsace is the fifth-smallest of the 27 regions of France in land area , and the smallest in metropolitan France. It is also the seventh-most densely populated region in France and third most densely populated region in metropolitan France, with ca. 220 inhabitants per km²...

, a free imperial city

Free Imperial City

In the Holy Roman Empire, a free imperial city was a city formally ruled by the emperor only — as opposed to the majority of cities in the Empire, which were governed by one of the many princes of the Empire, such as dukes or prince-bishops...

of the Holy Roman Empire. His father and grandfather, both named Claus Butzer, were coopers

Cooper (profession)

Traditionally, a cooper is someone who makes wooden staved vessels of a conical form, of greater length than breadth, bound together with hoops and possessing flat ends or heads...

(barrelmakers) by trade. Almost nothing is known about Bucer's mother. Bucer likely attended Sélestat's prestigious Latin school

Latin School

Latin School may refer to:* Latin schools of Medieval Europe* These schools in the United States:** Boston Latin School, Boston, MA** Brooklyn Latin School, New York, NY** Brother Joseph C. Fox Latin School, Long Island, NY...

, where artisans sent their children. He completed his studies in the summer of 1507 and joined the Dominican order

Dominican Order

The Order of Preachers , after the 15th century more commonly known as the Dominican Order or Dominicans, is a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Dominic and approved by Pope Honorius III on 22 December 1216 in France...

as a novice

Novice

A novice is a person or creature who is new to a field or activity. The term is most commonly applied in religion and sports.-Buddhism:In many Buddhist orders, a man or woman who intends to take ordination must first become a novice, adopting part of the monastic code indicated in the vinaya and...

. Bucer later claimed his grandfather had forced him into the order. After a year, he was consecrated as an acolyte

Acolyte

In many Christian denominations, an acolyte is anyone who performs ceremonial duties such as lighting altar candles. In other Christian Churches, the term is more specifically used for one who wishes to attain clergyhood.-Etymology:...

in the Strasbourg church

Saint William's Church, Strasbourg

Saint William's Church is a gothic church presently of the Lutheran branch of Christianity located in Strasbourg, France...

of the Williamites

Hermits of Saint William

The Hermits of Saint William was a monastic order founded by Albert, companion and biographer of William of Maleval, and Renaldus, a physician who had settled at Maleval shortly before the saint's death...

, and he took his vows as a full Dominican friar

Friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders.-Friars and monks:...

. In 1510, he was consecrated as a deacon

Deacon

Deacon is a ministry in the Christian Church that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions...

.

By 1515, Bucer was studying theology in the Dominican monastery in Heidelberg

Heidelberg

-Early history:Between 600,000 and 200,000 years ago, "Heidelberg Man" died at nearby Mauer. His jaw bone was discovered in 1907; with scientific dating, his remains were determined to be the earliest evidence of human life in Europe. In the 5th century BC, a Celtic fortress of refuge and place of...

. The following year, he took a course in dogmatics in Mainz

Mainz

Mainz under the Holy Roman Empire, and previously was a Roman fort city which commanded the west bank of the Rhine and formed part of the northernmost frontier of the Roman Empire...

, where he was ordained

Ordination

In general religious use, ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart as clergy to perform various religious rites and ceremonies. The process and ceremonies of ordination itself varies by religion and denomination. One who is in preparation for, or who is...

a priest, returning to Heidelberg in January 1517 to enroll in the university. Around this time, he became influenced by humanism

Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanism was an activity of cultural and educational reform engaged by scholars, writers, and civic leaders who are today known as Renaissance humanists. It developed during the fourteenth and the beginning of the fifteenth centuries, and was a response to the challenge of Mediæval...

, and he started buying books published by Johannes Froben, some by the great humanist Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus , known as Erasmus of Rotterdam, was a Dutch Renaissance humanist, Catholic priest, and a theologian....

. A 1518 inventory of Bucer's books includes the major works of Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, O.P. , also Thomas of Aquin or Aquino, was an Italian Dominican priest of the Catholic Church, and an immensely influential philosopher and theologian in the tradition of scholasticism, known as Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Communis, or Doctor Universalis...

, leader of medieval scholasticism

Scholasticism

Scholasticism is a method of critical thought which dominated teaching by the academics of medieval universities in Europe from about 1100–1500, and a program of employing that method in articulating and defending orthodoxy in an increasingly pluralistic context...

in the Dominican order.

In April 1518, Johannes von Staupitz, the vicar-general of the Augustinians

Augustinians

The term Augustinians, named after Saint Augustine of Hippo , applies to two separate and unrelated types of Catholic religious orders:...

, invited the Wittenberg

Wittenberg

Wittenberg, officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg, is a city in Germany in the Bundesland Saxony-Anhalt, on the river Elbe. It has a population of about 50,000....

reformer Martin Luther

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517...

to argue his theology at the Heidelberg Disputation

Heidelberg Disputation

The Heidelberg Disputation was held at the Meeting of the Augustianian order on April 26, 1518. It was here that Martin Luther, as a delegate for his order, began to have occasion to articulate his views. In the defense of his theses, Luther defended the doctrine of the depravity of man and the...

. Here Bucer met Luther for the first time. In a long letter to his mentor, Beatus Rhenanus

Beatus Rhenanus

Beatus Rhenanus , also known as Beatus Bild, was an Alsatian humanist, religious reformer, and classical scholar....

, Bucer recounted what he learned, and he commented on several of Luther's Ninety-Five Theses. He largely agreed with them and perceived the ideas of Luther and Erasmus to be in concordance. Because meeting Luther posed certain risks, he asked Rhenanus to ensure his letter did not fall into the wrong hands. He also wrote his will, which contains the inventory of his books. In early 1519, Bucer received the baccalaureus degree, and that summer he stated his theological views in a disputation before the faculty at Heidelberg, revealing his break with Aquinas and scholasticism.

Jacob van Hoogstraaten

Jacob van Hoogstraten was a theologian and controversialist, born about 1460, in Hoogstraeten, Belgium; died in Cologne, 24 January 1527.- Education, professor :...

, the grand inquisitor

Grand Inquisitor

Grand Inquisitor is the lead official of an Inquisition. The most famous Inquisitor General is the Spanish Dominican Tomás de Torquemada, who spearheaded the Spanish Inquisition.-List of Spanish Grand Inquisitors:-Castile:-Aragon:...

of Cologne

Cologne

Cologne is Germany's fourth-largest city , and is the largest city both in the Germany Federal State of North Rhine-Westphalia and within the Rhine-Ruhr Metropolitan Area, one of the major European metropolitan areas with more than ten million inhabitants.Cologne is located on both sides of the...

, tried to prosecute Johann Reuchlin

Johann Reuchlin

Johann Reuchlin was a German humanist and a scholar of Greek and Hebrew. For much of his life, he was the real centre of all Greek and Hebrew teaching in Germany.-Early life:...

, a humanist scholar. Other humanists, including the nobles Ulrich von Hutten

Ulrich von Hutten

Ulrich von Hutten was a German scholar, poet and reformer. He was an outspoken critic of the Roman Catholic Church and a bridge between the humanists and the Lutheran Reformation...

and imperial knight

Imperial Knight

The Free Imperial Knights, or the Knights of the Empire was an organisation of free nobles of the Holy Roman Empire, whose direct overlord was the Emperor, remnants of the medieval free nobility and the ministeriales...

Franz von Sickingen

Franz von Sickingen

Franz von Sickingen was a German knight, one of the most notable figures of the first period of the Reformation.-Biography:He was born at Ebernburg near Bad Kreuznach...

, took Reuchlin's side. Hoogstraten was thwarted, but he now planned to target Bucer. On 11 November 1520, Bucer told the reformer Wolfgang Capito in a letter that Hoogstraaten was threatening to make an example of him as a follower of Luther. To escape Dominican jurisdiction, Bucer needed to be freed of his monastic vows. Capito and others were able to expedite the annulment of his vows, and on 29 April 1521 he was formally released from the Dominican order.

For the next two years, Bucer was protected by Sickingen and Hutten. He also worked for a time at the court of Ludwig V, Elector Palatine

Louis V, Elector Palatine

Louis V, Count Palatine of the Rhine ; a member of the Wittelsbach dynasty was prince elector of the Palatinate....

, as chaplain to Ludwig's younger brother Frederick. Sickingen was a senior figure at Ludwig's court. This appointment enabled Bucer to live in Nuremberg

Nuremberg

Nuremberg[p] is a city in the German state of Bavaria, in the administrative region of Middle Franconia. Situated on the Pegnitz river and the Rhine–Main–Danube Canal, it is located about north of Munich and is Franconia's largest city. The population is 505,664...

, the most powerful city of the Empire, whose governing officials were strongly reformist. There he met many people who shared his viewpoint, including the humanist Willibald Pirckheimer

Willibald Pirckheimer

Willibald Pirckheimer was a German Renaissance lawyer, author and Renaissance humanist, a wealthy and prominent figure in Nuremberg in the 16th century, and a member of the governing City Council for two periods...

and the future Nuremberg reformer Andreas Osiander

Andreas Osiander

Andreas Osiander was a German Lutheran theologian.- Career :Born at Gunzenhausen in Franconia, Osiander studied at the University of Ingolstadt before being ordained as a priest in 1520. In the same year he began work at an Augustinian convent in Nuremberg as a Hebrew tutor. In 1522, he was...

. In September 1521, Bucer accepted Sickingen's offer of the position of pastor at Landstuhl

Landstuhl

Landstuhl , literally translating as "country-throne", is a municipality of over 9,000 people in southwestern Germany. It is part of the district of Kaiserslautern, in the Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, and is home to the Sickinger Schloss, a small castle. It is situated on the north-western edge...

, where Sickingen had a castle, and Bucer moved to the town in May 1522. In summer 1522, he met and married Elisabeth Silbereisen, a former nun.

Sickingen also offered to pay for Bucer to study in Wittenberg. On his way, Bucer stopped in the town of Wissembourg

Wissembourg

Wissembourg is a commune in the Bas-Rhin department in Alsace in northeastern France.It is situated on the little River Lauter close to the border between France and Germany approximately north of Strasbourg and west of Karlsruhe. Wissembourg is a sub-prefecture of the department...

, whose leading reformer, Heinrich Motherer, asked him to become his chaplain. Bucer agreed to interrupt his journey and went to work immediately, preaching daily sermons in which he attacked traditional church practices and monastic orders. On the basis of his belief that the Bible was the sole source for knowledge to attain salvation (sola scriptura

Sola scriptura

Sola scriptura is the doctrine that the Bible contains all knowledge necessary for salvation and holiness. Consequently, sola scriptura demands that only those doctrines are to be admitted or confessed that are found directly within or indirectly by using valid logical deduction or valid...

), he preached that the mass should not be considered as the recrucifying of Christ, but rather the reception of God's gift of salvation through Christ. He accused the monks of creating additional rules above what is contained in the Bible. He summarised his convictions in six theses, and called for a public disputation. His opponents, the local Franciscans and Dominicans, ignored him, but his sermons incited the townspeople to threaten the town's monasteries. The bishop of Speyer

Speyer

Speyer is a city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany with approximately 50,000 inhabitants. Located beside the river Rhine, Speyer is 25 km south of Ludwigshafen and Mannheim. Founded by the Romans, it is one of Germany's oldest cities...

reacted by excommunicating

Excommunication

Excommunication is a religious censure used to deprive, suspend or limit membership in a religious community. The word means putting [someone] out of communion. In some religions, excommunication includes spiritual condemnation of the member or group...

Bucer, and although the town council continued to support him, events beyond Wissembourg left Bucer in danger. His leading benefactor, Franz von Sickingen, was defeated and killed during the Knight's Revolt, and Ulrich von Hutten became a fugitive. The Wissembourg council urged Bucer and Motherer to leave, and on 13 May 1523 they fled to nearby Strasbourg.

Reformer in Strasbourg (1523–1525)

Bucer, excommunicated and without means of subsistence, was in a precarious situation when he arrived in Strasbourg. He was not a citizen of the city, a status that afforded protection, and on 9 June 1523 he wrote an urgent letter to the ZürichZürich

Zurich is the largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is located in central Switzerland at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich...

reformer, Huldrych Zwingli

Huldrych Zwingli

Ulrich Zwingli was a leader of the Reformation in Switzerland. Born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swiss mercenary system, he attended the University of Vienna and the University of Basel, a scholarly centre of humanism...

, pleading for a safe post in Switzerland. Fortunately for Bucer, the Strasbourg council was under the influence of the reformer, Matthew Zell; during Bucer's first few months in the city he worked as Zell's unofficial chaplain and was able to give classes on books of the Bible. The largest guild in Strasbourg, the Gärtner or Gardeners, appointed him as its pastor on 24 August 1523. A month later the council accepted his application for citizenship.

Caspar Hedio

Caspar Hedio, was a historian and Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg.- References :...

, the cathedral preacher. One of Bucer's first actions in the cause of reform was to debate with Thomas Murner

Thomas Murner

Thomas Murner was a German satirist, poet and translator.He was born at Oberehnheim near Strasbourg. In 1490 he entered the Franciscan order, and in 1495 began travelling, studying and then teaching and preaching in Freiburg-im-Breisgau, Paris, Kraków and Strasbourg itself...

, a monk who had attacked Luther in satires. While the city council vacillated on religious issues, the number of people supporting the Reformation and hostile towards the traditional clergy had grown.

The hostility reached a boiling point when Conrad Treger, the prior provincial

Provincial superior

A Provincial Superior is a major superior of a religious order acting under the order's Superior General and exercising a general supervision over all the members of that order in a territorial division of the order called a province--similar to but not to be confused with an ecclesiastical...

of the Augustinians

Augustinians

The term Augustinians, named after Saint Augustine of Hippo , applies to two separate and unrelated types of Catholic religious orders:...

, denounced the reformist preachers and the burghers

Bourgeoisie

In sociology and political science, bourgeoisie describes a range of groups across history. In the Western world, between the late 18th century and the present day, the bourgeoisie is a social class "characterized by their ownership of capital and their related culture." A member of the...

of Strasbourg as heretics. On 5 September 1524, angry mobs broke into the monasteries, looting and destroying religious images. Many opponents of the Reformation were arrested, including Treger. After the council requested an official statement from the reformers, Bucer drafted twelve articles summarising the teachings of the Reformation, including justification by faith (sola fide). He rejected the mass

Mass (liturgy)

"Mass" is one of the names by which the sacrament of the Eucharist is called in the Roman Catholic Church: others are "Eucharist", the "Lord's Supper", the "Breaking of Bread", the "Eucharistic assembly ", the "memorial of the Lord's Passion and Resurrection", the "Holy Sacrifice", the "Holy and...

and Catholic

Catholic

The word catholic comes from the Greek phrase , meaning "on the whole," "according to the whole" or "in general", and is a combination of the Greek words meaning "about" and meaning "whole"...

concepts such as monastic vows, veneration

Veneration

Veneration , or veneration of saints, is a special act of honoring a saint: an angel, or a dead person who has been identified by a church committee as singular in the traditions of the religion. It is practiced by the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Roman Catholic, and Eastern Catholic Churches...

of saints, and purgatory

Purgatory

Purgatory is the condition or process of purification or temporary punishment in which, it is believed, the souls of those who die in a state of grace are made ready for Heaven...

. He refused to recognise the authority of the pope and instead emphasised obedience to the government. Treger was released on 12 October and left Strasbourg. With his departure, overt opposition to the Reformation ended in the city.

The reformers' first goal was the creation of a new order of service

Church service

In Christianity, a church service is a term used to describe a formalized period of communal worship, often but not exclusively occurring on Sunday, or Saturday in the case of those churches practicing seventh-day Sabbatarianism. The church service is the gathering together of Christians to be...

—at this time the Strasbourg reformers followed Zwingli's liturgy. They presented proposals for a common order of service for the entire Reformation movement to the theologians of Wittenberg and Zürich. In Bucer's booklet Grund und Ursach (Basis and Cause), published in December 1524, he attacked the idea of the mass as a sacrifice, and rejected liturgical garments

Vestment