History of Christian theology

Encyclopedia

The doctrine of the Trinity

, considered the core of Christian theology

by Trinitarians, is the result of continuous exploration by the church of the biblical data, thrashed out in debate and treatises, eventually formulated at the First Council of Nicaea

in 325 AD in a way they believe is consistent with the biblical witness, and further refined in later councils

and writings. The most widely recognized Biblical foundations for the doctrine's formulation are in the Gospel of John

.

Nontrinitarianism

is any of several Christian beliefs that reject the Trinitarian doctrine

that God is three distinct persons in one being. Modern nontrinitarian groups views differ widely on the nature of God

, Jesus

, and the Holy Spirit

.

is a field of study within Christian theology which is concerned with the nature of Jesus the Christ

, particularly with how the divine and human are related in his person. Christology is generally less concerned with the details of Jesus' life than with how the human

and divine

co-exist in one person. Although this study of the inter-relationship of these two natures is the foundation of Christology, some essential sub-topics within the field of Christology include:

Christology is related to questions concerning the nature of God like the Trinity, Unitarianism

or Binitarianism

. However, from a Christian perspective, these questions are concerned with how the divine persons relate to one another, whereas Christology is concerned with the meeting of the human (Son of Man

) and divine (God the Son

) in the person of Jesus.

Throughout the history of Christianity

, Christological questions have been very important in the life of the church. Christology was a fundamental concern from the First Council of Nicaea (325) until the Third Council of Constantinople

(680) (or the Second Council of Nicaea

[787]). In this time period (see also First seven Ecumenical Councils

), the Christological views of various groups within the broader Christian community led to accusations of heresy

, and, infrequently, subsequent religious persecution

. In some cases, a sect's unique Christology is its chief distinctive feature; in these cases it is common for the sect to be known by the name given to its Christology.

_-_the_madonna_of_the_roses_(1903).jpg) Mariology is the area of Christian theology concerned with Mary, the Mother of Jesus. It not only deals with her life but her veneration mainly through Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy

Mariology is the area of Christian theology concerned with Mary, the Mother of Jesus. It not only deals with her life but her veneration mainly through Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy

, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Assyrian Church of the East

and Anglicanism

, and her aspect in modern and ancient Christianity.

St. Irenaeus

of Lyons called Mary the "second Eve

" because through Mary and her willing acceptance of God's choice, God undid the harm that was done through Eve's choice to eat the forbidden fruit

in the Garden of Eden

.

The Third Ecumenical Council debated whether she should be referred to as Theotokos

or Christotokos. Theotokos means "God-bearer" or "Mother of God"; its use implies that Jesus, to whom Mary gave birth, is God. Nestorians preferred Christotokos meaning "Christ-bearer" or "Mother of the Messiah" not because they denied Jesus' divinity, but because they believed that God the Son or Logos existed before time and before Mary, and that Jesus took divinity from God the Father and humanity from his mother, so calling her "Mother of God" was confusing and potentially heretical. Others at the council believed that denying the Theotokos title would carry with it the implication that Jesus was not divine. Ultimately, the council affirmed the use of the term "Theotokos" and by doing so affirmed Jesus' undivided divinity and humanity. Thus, while the debate was over the proper title for Mary, it was also a Christological question about the nature of Jesus Christ, a question which would return at the Fourth Ecumenical Council. Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox and Anglican theological teaching affirms the "Mother of God" title, while some other Christians give no such title to her.

The belief, held by most Christians, that Mary was a virgin when she gave birth to Jesus, is called the doctrine of the Virgin Birth

. Theologians disagree over whether she remained a virgin, as the written Scripture names four brothers of Jesus, notably James the Just

, and states that Jesus also had sisters. Roman Catholics and Eastern Orthodox view these siblings as relatives, but not children of Mary, using arguments about Aramaic language. Roman Catholic dogma asserts the perpetual virginity of Mary

(as does Islam and most Eastern Orthodox theologians), and since the writing of the apocryphal

Protevangelium of James, various beliefs have circulated concerning Mary's conception, which eventually led to the dogma, formally established in the 19th century, of the Immaculate Conception

in the Roman Catholic Church, which exempts her from original sin

.

Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox teaching also extends to the end of Mary's life ending with the Assumption of Mary

(formally established as dogma in 1950) and the Dormition of the Theotokos

respectively.

Some Protestants accuse Roman Catholics of having developed an un-Christian adoration and worship of Mary, described as Marianism or Mariolatry, and of inventing non-scriptual doctrines which give Mary a semi-divine status by seeking to duplicate in the life of Mary events similar to those in the life of Jesus. They also attack titles such as Queen of Heaven

, Our Mother in Heaven, Queen of the World, or Mediatrix. Roman Catholics respond by stating that Mary was human and so is not worshipped, but is special before other saints, and therefore worthy of particular veneration.

The Biblical canon is the set of books Christians regard as divinely inspired and thus constituting the Christian Bible. Though the early church

The Biblical canon is the set of books Christians regard as divinely inspired and thus constituting the Christian Bible. Though the early church

used the Old Testament according to the canon of the Septuagint (LXX), the apostles did not otherwise leave a defined set of new scriptures; instead the New Testament

developed over time.

The writings attributed to the apostles circulated amongst the earliest Christian communities. The Pauline epistles

were circulating in collected form by the end of the 1st century AD. The Bryennios list is an early Christian canon found in Codex Hierosolymitanus

and dated to around 100. Justin Martyr, in the early 2nd century, mentions the "memoirs of the apostles", but his references are not detailed. Around 160 Irenaeus

of Lyons argued for only four Gospels (the Tetramorph), and argued that it would be illogical to reject Acts of the Apostles but accept the Gospel of Luke, as both were from the same author. By the early 200's, Origen

may have been using the same 27 books as in the modern New Testament, though there were still disputes over the canonicity of Hebrews, James, II Peter, II and III John, and Revelation, see Antilegomena

. Likewise by 200 the Muratorian fragment

shows that there existed a set of Christian writings somewhat similar to what is now the 27-book New Testament.

In his Easter letter of 367, Athanasius, Bishop of Alexandria, gave a list exactly the same in number and order with what would become the New Testament canon and be accepted by the Greek church. The African Synod of Hippo

, in 393, approved the New Testament, as it stands today, together with the Septuagint books, a decision that was repeated by Councils of Carthage

in 397 and 419. Pope Damasus I

's Council of Rome

in 382, only if the Decretum Gelasianum

is correctly associated with it, issued a biblical canon identical to that mentioned above. In 405, Pope Innocent I

sent a list of the sacred books to a Gallic bishop, Exsuperius of Toulouse

. Nonetheless, a full dogmatic articulation of the canon was not made until the Council of Trent

in the 16th century.

over the Hebraic faith

of Jesus and the early disciples. The early African theologian Tertullian

, for instance, complained that the ‘Athens’ of philosophy was corrupting the ‘Jerusalem

’ of faith. More recent discussions have qualified and nuanced this picture.

contains evidence of some of the earliest forms of reflection upon the meanings and implications of Christian faith, mostly in the form of guidance offered to Christian congregations on how to live a life consistent with their convictions – most notably in the Sermon on the Mount

, the Pauline epistles

and the Johannine corpus

.

). The Council of Ephesus condemned Nestorianism

and affirmed the Blessed Virgin Mary to be Theotokos

("God-bearer" or "Mother of God"). Perhaps the most significant council was the Council of Chalcedon

that affirmed that Christ had two natures, fully God and fully man, distinct yet always in perfect union. This was based largely on Pope Leo the Great's Tome. Thus, it condemned Monophysitism

and would be influential in refuting Monothelitism

.

. Notable early Fathers include Justin Martyr

, Irenaeus, Tertullian

, Clement of Alexandria

, Origen

, etc.

A huge quantity of theological reflection emerged in the early centuries of the Christian church – in a wide variety of genres, in a variety of contexts, and in several languages – much of it the product of attempts to discuss how Christian faith should be lived in cultures very different from the one in which it was born. So, for instance, a good deal of the Greek language

literature can be read as an attempt to come to terms with Hellenistic culture. The period sees the slow emergence of orthodoxy

(the idea of which seems to emerge out of the conflicts between catholic

Christianity and Gnostic

Christianity), the establishment of a Biblical canon

, debates about the doctrine of the Trinity (most notably between the councils of Nicaea

in 325 and Constantinople

in 381), about Christology

(most notably between the councils of Constantinople in 381 and Chalcedon

in 451), about the purity of the Church (for instance in the debates surrounding the Donatist

s), and about grace

, free will

and predestination

(for instance in the debate between Augustine of Hippo

and Pelagius

).

Influential texts and writers between c.200 and 325 (the First Council of Nicaea) include:

(in present-day Turkey

), convoked by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in 325, was the first ecumenical

conference of bishop

s of the Catholic Church (Catholic as in 'universal', not just Roman) and most significantly resulted in the first declaration of a uniform Christian doctrine, called the Nicene Creed

. With the creation of the creed, a precedent was established for subsequent 'general (ecumenical) councils of Bishops' (Synod

s) to create statements of belief and canon

s of doctrinal orthodoxy— the intent being to define unity of beliefs for the whole of Christendom

.

The purpose of the council was to resolve disagreements in the Church of Alexandria over the nature of Jesus in relationship to the Father; in particular, whether Jesus was of the same substance

as God the Father

or merely of similar substance. St. Alexander of Alexandria and Athanasius took the first position; the popular presbyter

Arius, from whom the term Arian controversy

comes, took the second. The council decided against the Arians

overwhelmingly (of the estimated 250-318 attendees, all but 2 voted

against Arius). Another result of the council was an agreement on the date of the Christian Passover (Pascha in Greek; Easter

in modern English), the most important feast of the ecclesiastical calendar. The council decided in favour of celebrating the resurrection on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the vernal equinox, independently of the Bible

's Hebrew Calendar

(see also Quartodecimanism

), and authorized the Bishop of Alexandria (presumably using the Alexandrian calendar) to announce annually the exact date to his fellow bishops.

The Council of Nicaea was historically significant because it was the first effort to attain consensus

in the church through an assembly

representing all of Christendom. "It was the first occasion for the development of technical Christology." Further, "Constantine in convoking and presiding over the council signaled a measure of imperial control over the church." With the creation of the Nicene Creed, a precedent was established for subsequent general councils to create a statement of belief

and canons

which were intended to become guidelines for doctrinal orthodoxy and a source of unity for the whole of Christendom — a momentous event in the history of the church and subsequent history of Europe.

, addresses some aspect that had been under passionate discussion and closes the books on the argument, with the weight of the agreement of the over 300 bishops in attendance. [Constantine had invited all 1800 bishops of the Christian church (about 1000 in the east and 800 in the west). The number of participating bishops cannot be accurately stated; Socrates Scholasticus and Epiphanius of Salamis counted 318; Eusebius of Caesarea, only 250.] In spite of the agreement reached at the council of 325 the Arians who had been defeated dominated most of the church for the greater part of the 4th century, often with the aid of Roman emperors who favored them. In the East, the successful party of Cyril

cast out Nestorius

and his followers as heretics and collected and burned his writings

.

Late antique Christianity produced a great many renowned church fathers

Late antique Christianity produced a great many renowned church fathers

who wrote volumes of theological texts, including SS. Augustine

, Gregory Nazianzus

, Cyril of Jerusalem

, Ambrose of Milan

, Jerome

, and others. What resulted was a golden age of literary and scholarly activity unmatched since the days of Virgil and Horace. Some of these fathers, such as John Chrysostom

and Athanasius

, suffered exile, persecution, or martyrdom from heretical Byzantine Emperors. Many of their writings are translated into English in the compilations of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers

.

Influential texts and writers between 325 AD and c.500 AD include:

Texts from patristic authors after 325 AD are collected in the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers. Important theological debates also surrounded the various Ecumenical Councils

– Nicaea in 325, Constantinople in 381, Ephesus in 431 and Chalcedon in 451.

developed over time. This is Roman doctrine and rejected by most if not all Reformed churches. As a bishopric, its origin is consistent with the development of an episcopal structure in the 1st century. The origins of papal primacy concept are historically obscure; theologically, it is based on three ancient Christian traditions: (1) that the apostle Peter was preeminent among the apostles

, (2) that Peter ordained his successors as Bishop of Rome

, and (3) that the bishops are the successors of the apostles

. As long as the Papal See also happened to be the capital of the Western Empire, prestige of the Bishop of Rome could be taken for granted without the need of sophisticated theological argumentation beyond these points; after its shift to Milan and then Ravenna, however, more detailed arguments were developed based on etc. Nonetheless, in antiquity the Petrine and Apostolic quality, as well as a "primacy of respect", concerning the Roman See went unchallenged by emperors, eastern patriarchs, and the Eastern Church alike. The Ecumenical Council of Constantinople in 381 affirmed Rome as "first among equals". By the close of antiquity, the doctrinal clarification and theological arguments on the primacy of Rome were developed. Just what exactly was entailed in this primacy, and its being exercised, would become a matter of controversy at certain later times.

itself speaks of the importance of maintaining orthodox doctrine and refuting heresies, showing the antiquity of the concern. The development of doctrine, the position of orthodoxy, and the relationship between the early Church and early heretical groups is a matter of academic debate. Some scholars, drawing upon distinctions between Jewish Christians

, Gentile Christians, and other groups such as Gnostics

, see Early Christianity as fragmented and with contemporaneous competing orthodoxies.

The process of establishing orthodox Christianity was set in motion by a succession of different interpretations of the teachings of Christ being taught after the crucifixion

. Though Christ himself is noted to have spoken out against false prophet

s and false christs within the gospels themselves Mark 13:22 (some will arise and distort the truth in order to draw away disciples), Matthew 7:5-20, Matthew 24:4, Matthew 24:11 Matthew 24:24 (For false christs and false prophets will arise). On many occasions in Paul's epistles, he defends his own apostleship, and urges Christians in various places to beware of false teachers, or of anything contrary to what was handed to them by him. The epistles of John and Jude also warn of false teachers and prophet

s, as does the writer of the Book of Revelation

and 1 Jn. 4:1, as did the Apostle Peter warn in 2 Pt. 2:1-3:.

One of the roles of bishops, and the purpose of many Christian writings, was to refute heresies

. The earliest of these were generally Christological

in nature, that is, they denied either Christ's (eternal) divinity or humanity. For example, Docetism

held that Jesus' humanity was merely an illusion, thus denying the incarnation; whereas Arianism

held that Jesus was not eternally divine. Many groups were dualistic, maintaining that reality was composed into two radically opposing parts: matter, usually seen as evil, and spirit, seen as good. Orthodox Christianity, on the other hand, held that both the material and spiritual worlds were created by God and were therefore both good, and that this was represented in the unified divine and human natures of Christ.

Irenaeus

(c. 130–202) was the first to argue that his "proto-orthodox" position was the same faith that Jesus gave to the apostles, and that the identity of the apostles, their successors, and the teachings of the same were all well-known public knowledge. This was therefore an early argument supported by apostolic succession

. Irenaeus first established the doctrine of four gospels and no more, with the synoptic gospels interpreted in the light of John

. Irenaeus' opponents, however, claimed to have received secret teachings from Jesus via other apostles which were not publicly known. Gnosticism

is predicated on the existence of such hidden knowledge, but brief references to private teachings of Jesus have also survived in the canonic Scripture as did warning by the Christ that there would be false prophets or false teachers. Irenaeus' opponents also claimed that the wellsprings of divine inspiration were not dried up, which is the doctrine of continuing revelation.

In the middle of the 2nd century, three groups of Christians adhered to a range of doctrines that divided the Christian communities of Rome: the teacher Marcion, the pentecostal outpourings of ecstatic Christian prophets of a continuing revelation, in a movement that was called "Montanism

" because it had been initiated by Montanus and his female disciples, and the gnostic

teachings of Valentinus. Early attacks upon alleged heresies formed the matter of Tertullian

's Prescription Against Heretics (in 44 chapters, written from Rome), and of Irenaeus' Against Heresies (ca 180, in five volumes), written in Lyons after his return from a visit to Rome. The letters of Ignatius of Antioch

and Polycarp of Smyrna to various churches warned against false teachers, and the Epistle of Barnabas

accepted by many Christians as part of Scripture in the 2nd century, warned about mixing Judaism with Christianity, as did other writers, leading to decisions reached in the first ecumenical council, which was convoked by the Emperor Constantine at Nicaea in 325, in response to further disruptive polemical controversy within the Christian community, in that case Arian

disputes over the nature of the Trinity.

During those first three centuries, Christianity was effectively outlawed by requirements to venerate the Roman emperor and Roman gods. Consequently, when the Church labelled its enemies as heretics and cast them out of its congregations or severed ties with dissident churches, it remained without the power to persecute them. However, those called "heretics" were also called a number of other things (e.g. "fools," "wild dogs," "servants of Satan"), so the word "heretic" had negative associations from the beginning, and intentionally so.

Before 325 AD, the "heretical" nature of some beliefs was a matter of much debate within the churches. After 325 AD, some opinion was formulated as dogma through the canons promulgated by the councils.

that took place from October 8 to November 1, 451, at Chalcedon

(a city of Bithynia

in Asia Minor

).

It is the fourth of the first seven ecumenical councils in Christianity

, and is therefore recognized as infallible in its dogmatic definition

s by the Roman Catholic

and Eastern Orthodox churches. It repudiated the Eutychian

doctrine of monophysitism

, and set forth the Chalcedonian Creed

, which describes the "full humanity and full divinity" of Jesus, the second person of the Holy Trinity

.

A thorough understanding of the Iconoclastic Period in Byzantium is complicated by the fact that most of the surviving sources were written by the ultimate victors in the controversy, the iconodules

. It is thus difficult to obtain a complete, objective, balanced, and reliably accurate account of events and various aspects of the controversy.

As with other doctrinal issues in the Byzantine period, the controversy was by no means restricted to the clergy, or to arguments from theology. The continuing cultural confrontation with, and military threat from, the Islam

probably had a bearing on the attitudes of both sides. Iconoclasm seems to have been supported by many from the East of the Empire, and refugees from the provinces taken over by the Muslims. It has been suggested that their strength in the army at the start of the period, and the growing influence of Balkan forces in the army (generally considered to lack strong iconoclast feelings) over the period may have been important factors in both beginning and ending imperial support for iconoclasm.

and Cassiodorus

was different from the vigorous Frankish

Christianity documented by Gregory of Tours

which was different again from the Christianity that flourished in Ireland

and Northumbria

in the 7th and 8th centuries. Throughout this period, theology tended to be a more monastic

affair, flourishing in monastic havens where the conditions and resources for theological learning could be maintained.

Important writers include:

saw an explosion of theological inquiry, and theological controversy. Controversy flared, for instance, around 'Spanish Adoptionism

, around the views on predestination of Gottschalk

, or around the eucharistic views of Ratramnus

.

Important writers include:

in the 9th century or Chartres

in the 11th. Intellectual influences from the Arabic world (including works of classical authors preserved by Islamic scholars) percolated into the Christian West via Spain, influencing such theologians as Gerbert of Aurillac, who went on to become Pope Sylvester II and mentor to Otto III. (Otto was the fourth ruler of the Germanic Ottonian

Holy Roman Empire

, successor to the Carolingian Empire). With hindsight, one might say that a new note was struck when a controversy about the meaning of the eucharist blew up around Berengar of Tours

in the 11th century: hints of a new confidence in the intellectual investigation of the faith that perhaps foreshadowed the explosion of theological argument that was to take place in the 12th century.

Notable authors include:

word scholasticus, which means "that [which] belongs to the school", and was a method of learning taught by the academics (or schoolmen) of medieval universities

c. 1100–1500. Scholasticism originally began to reconcile the philosophy

of the ancient classical philosophers with medieval Christian theology. It is not a philosophy or theology in itself, but a tool and method for learning which puts emphasis on dialectical reasoning. The primary purpose of scholasticism was to find the answer to a question or resolve a contradiction. It is most well known in its application in medieval theology, but was eventually applied to classical philosophy and many other fields of study.

is sometimes misleadingly called the 'Father of Scholasticism' because of the prominent place that reason has in his theology; instead of establishing his points by appeal to authority, he presents arguments to demonstrate why it is that the things he believes on authority must be so. His particular approach, however, was not very influential in his time, and he kept his distance from the sathedral schools. We should look instead to the production of the gloss

on Scripture associated with Anselm of Laon

, the rise to prominence of dialectic

(middle subject of the medieval trivium) in the work of Abelard, and the production by Peter Lombard

of a collection of Sentences

or opinions of the Church Fathers and other authorities. Scholasticism proper can be thought of as the kind of theology that emerges when, in the sathedral schools and their successors, the tools of dialectic are pressed into use to comment upon, explain, and develop the gloss and the sentences.

Notable authors include:

and the associated rise of the mendicant orders

(notably the Franciscan

s and Dominicans

), in part intended as a form of orthodox alternative to the heretical groups. Those two orders quickly became contexts for some of the most intense scholatsic theologizing, producing such 'high scholastic' theologians as Alexander of Hales

(Franciscan) and Thomas Aquinas

(Dominican), or the rather less obviously scholastic Bonaventure

(Franciscan). The century also saw a flourishing of mystical theology

, with women such as Mechthild of Magdeburg

playing a prominent role. In addition, the century can be seen as period in which the study of natural philosophy that could anachronistically be called 'science' began once again to flourish in theological soil, in the hands of such men as Robert Grosseteste

and Roger Bacon

.

Notable authors include:

or voluntarist theologies of men like William of Ockham

. The 14th century was also a time in which movements of widely varying character worked for the reform of the institutional church, such as conciliarism

, Lollardy

and the Hussite

s. Spiritual movements such as the Devotio Moderna

also flourished.

Notable authors include:

yielded scholars the ability to read the scriptures in their original languages and this in part stimulated the Reformation

. Martin Luther

, a Doctor in Bible at the University of Wittenburg, began to teach that salvation

is a gift of God's grace

, attainable only through faith

in Jesus, who in humility

paid for sin. "This one and firm rock, which we call the doctrine of justification

," insisted Martin Luther, "is the chief article of the whole Christian doctrine, which comprehends the understanding of all godliness." Along with the doctrine of justification, the Reformation promoted a higher view of the Bible. As Martin Luther said, "The true rule is this: God's Word shall establish articles of faith, and no one else, not even an angel can do so.". These two ideas in turn promoted the concept of the priesthood of all believers

. Other important reformers were John Calvin

, Huldrych Zwingli

, Philipp Melanchthon

, Martin Bucer

and the Anabaptist

s. Their theology was modified by successors such as Theodore Beza

, the English Puritans and Francis Turretin

.

is a major branch of Western Christianity

that identifies with the teachings of the 16th-century German

reformer Martin Luther. Luther's efforts to reform the theology and practice of the church launched The Reformation. As a result of the reactions of his contemporaries, Christianity was divided. Luther's insights were a major foundation of the Protestant movement

.

In 1516-17, Johann Tetzel

In 1516-17, Johann Tetzel

, a Dominican friar and papal commissioner for indulgences, was sent to Germany by the Roman Catholic Church to sell indulgences to raise money to rebuild St Peter's Basilica in Rome. Roman Catholic theology stated that faith alone, whether fiduciary or dogmatic, cannot justify man; and that only such faith as is active in charity and good works (fides caritate formata) can justify man. These good works could be obtained by donating money to the church.

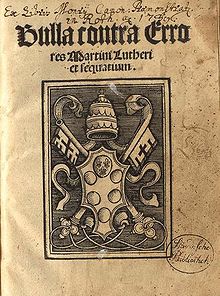

On 31 October 1517, Luther wrote to Albrecht, Archbishop of Mainz and Magdeburg, protesting the sale of indulgences. He enclosed in his letter a copy of his "Disputation of Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences," which came to be known as The 95 Theses. Hans Hillerbrand writes that Luther had no intention of confronting the church, but saw his disputation as a scholarly objection to church practices, and the tone of the writing is accordingly "searching, rather than doctrinaire." Hillerbrand writes that there is nevertheless an undercurrent of challenge in several of the theses, particularly in Thesis 86, which asks: "Why does the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with the money of poor believers rather than with his own money?"

Luther objected to a saying attributed to Johann Tetzel that "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs," insisting that, since forgiveness was God's alone to grant, those who claimed that indulgences absolved buyers from all punishments and granted them salvation were in error. Christians, he said, must not slacken in following Christ on account of such false assurances.

According to Philipp Melanchthon, writing in 1546, Luther nailed a copy of the 95 Theses

to the door of the Castle Church

in Wittenberg

that same day — church doors acting as the bulletin boards of his time — an event now seen as sparking the Protestant Reformation

, and celebrated each year on 31 October as Reformation Day

. Some scholars have questioned the accuracy of Melanchthon's account, noting that no contemporaneous evidence exists for it. Others have countered that no such evidence is necessary, because this was the customary way of advertising an event on a university campus in Luther's day.

The 95 Theses

were quickly translated from Latin into German, printed, and widely copied, making the controversy one of the first in history to be aided by the printing press

. Within two weeks, the theses had spread throughout Germany; within two months throughout Europe.

From 1510 to 1520, Luther lectured on the Psalms, the books of Hebrews, Romans, and Galatians. As he studied these portions of the Bible, he came to view the use of terms such as penance

and righteousness

by the Roman Catholic Church in new ways. He became convinced that the church was corrupt in their ways and had lost sight of what he saw as several of the central truths of Christianity, the most important of which, for Luther, was the doctrine of justification — God's act of declaring a sinner righteous — by faith alone through God's grace. He began to teach that salvation or redemption is a gift of God's grace

, attainable only through faith in Jesus as the messiah

.

Luther came to understand justification as entirely the work of God. Against the teaching of his day that the righteous acts of believers are performed in cooperation with God, Luther wrote that Christians receive such righteousness entirely from outside themselves; that righteousness not only comes from Christ but actually is the righteousness of Christ, imputed to Christians (rather than infused into them) through faith. "That is why faith alone makes someone just and fulfills the law," he wrote. "Faith is that which brings the Holy Spirit through the merits of Christ." Faith, for Luther, was a gift from God. He explained his concept of "justification" in the Smalcald Articles:

In contrast to the speed with which the theses were distributed, the response of the papacy was painstakingly slow.

In contrast to the speed with which the theses were distributed, the response of the papacy was painstakingly slow.

Cardinal Albrecht of Hohenzollern, Archbishop of Mainz and Magdeburg, with the consent of Pope Leo X

, was using part of the indulgence income to pay his bribery debts, and did not reply to Luther’s letter; instead, he had the theses checked for heresy and forwarded to Rome.

Leo responded over the next three years, "with great care as is proper," by deploying a series of papal theologians and envoys against Luther. Perhaps he hoped the matter would die down of its own accord, because in 1518 he dismissed Luther as "a drunken German" who "when sober will change his mind".

Luther's writings circulated widely, reaching France, England, and Italy as early as 1519, and students thronged to Wittenberg to hear him speak. He published a short commentary on Galatians

and his Work on the Psalms. At the same time, he received deputations from Italy and from the Utraquists of Bohemia; Ulrich von Hutten

and Franz von Sickingen

offered to place Luther under their protection.

This early portion of Luther's career was one of his most creative and productive. Three of his best known works were published in 1520: To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation

, On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church

, and On the Freedom of a Christian

.

Finally on 30 May 1519, when the Pope demanded an explanation, Luther wrote a summary and explanation of his theses to the Pope. While the Pope may have conceded some of the points, he did not like the challenge to his authority so he summoned Luther to Rome to answer these. At that point Frederick the Wise, the Saxon Elector, intervened. He did not want one of his subjects to be sent to Rome to be judged by the Catholic clergy

so he prevailed on the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who needed Frederick's support, to arrange a compromise.

An arrangement was effected, however, whereby that summons was cancelled, and Luther went to Augsburg in October 1518 to meet the papal legate, Cardinal Thomas Cajetan

. The argument was long but nothing was resolved.

On 15 June 1520, the Pope warned Luther with the papal bull

(edict) Exsurge Domine

that he risked excommunication

unless he recanted 41 sentences drawn from his writings, including the 95 Theses

, within 60 days.

That autumn, Johann Eck

proclaimed the bull in Meissen and other towns. Karl von Miltitz

, a papal nuncio

, attempted to broker a solution, but Luther, who had sent the Pope a copy of On the Freedom of a Christian in October, publicly set fire to the bull and decretal

s at Wittenberg on 10 December 1520, an act he defended in Why the Pope and his Recent Book are Burned and Assertions Concerning All Articles.

As a consequence, Luther was excommunicated by Leo X

on 3 January 1521, in the bull Decet Romanum Pontificem

.

, France, the Italian Pope, their territories and other allies. The conflict would erupt into a religious war after Luther's death, fueled by the political climate of the Holy Roman Empire

and strong personalities on both sides.

In 1526, at the First Diet of Speyer

, it was decided that, until a General Council could meet and settle the theological issues raised by Martin Luther, the Edict of Worms would not be enforced and each Prince could decide if Lutheran teachings and worship would be allowed in his territories. In 1529, at the Second Diet of Speyer

, the decision the previous Diet of Speyer was reversed — despite the strong protests of the Lutheran princes, free cities and some Zwinglian territories. These states quickly became known as Protestants. At first, this term Protestant was used politically for the states that resisted the Edict of Worms. Over time, however, this term came to be used for the religious movements that opposed the Roman Catholic tradition in the 16th century.

Lutheranism would become known as a separate movement after the 1530 Diet of Augsburg

, which was convened by Charles V to try to stop the growing Protestant movement. At the Diet, Philipp Melanchthon presented a written summary of Lutheran beliefs called the Augsburg Confession

. Several of the German princes (and later, kings and princes of other countries) signed the document to define "Lutheran" territories. These princes would ally to create the Schmalkaldic League

in 1531, which lead to the Schmalkald War, 1547, a year after Luther's death, that pitted the Lutheran princes of the Schmalkaldic League against the Catholic forces of Charles V.

After the conclusion of the Schmalkald War, Charles V attempted to impose Catholic religious doctrine on the territories that he had defeated. However, the Lutheran movement was far from defeated. In 1577, the next generation of Lutheran theologians gathered the work of the previous generation to define the doctrine of the persisting Lutheran church. This document is known as the Formula of Concord

. In 1580, it was published with the Augsburg Confession, the Apology of the Augsburg Confession

, the Large

and Small Catechisms

of Martin Luther, the Smalcald Articles and the Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope

. Together they were distributed in a volume entitled The Book of Concord. This book is still used today.

. Following the Counter-Reformation, Catholic Austria and Bavaria, together with the electoral archbishops of Mainz, Cologne, and Trier consolidated the Catholic position on the German speaking section of the European continent. Because Luther sparked this mass movement, he is known as the father of the Protestant Reformation, and the father of Protestantism in general.

is a system of Christian theology and an approach to Christian life and thought within the Protestant tradition articulated by John Calvin, a Protestant Reformer

in the 16th century, and subsequently by successors, associates, followers and admirers of Calvin, his interpretation of scripture, and perspective on Christian life and theology. Calvin's system of theology and Christian life forms the basis of the reformed tradition, a term roughly equivalent to Calvinism.

The reformed tradition was originally advanced by stalwarts such as Martin Bucer, Heinrich Bullinger

and Peter Martyr Vermigli, and also influenced English reformers such as Thomas Cranmer

and John Jewel

. However, because of Calvin's great influence and role in the confessional and ecclesiastical debates throughout the 17th century, this reformed movement generally became known as Calvinism. Today, this term also refers to the doctrines and practices of the Reformed churches

, of which Calvin was an early leader, and the system is perhaps best known for its doctrines of predestination

and election

.

is a school of soteriological

thought in Protestant Christian theology founded by the Dutch

theologian Jacobus Arminius

. Its acceptance stretches through much of mainstream Protestantism

. Due to the influence of John Wesley

, Arminianism is perhaps most prominent in the Methodist movement

.

Arminianism holds to the following tenets:

Arminianism is most accurately used to define those who affirm the original beliefs of Jacobus Arminius himself, but the term can also be understood as an umbrella for a larger grouping of ideas including those of Hugo Grotius

, John Wesley, Clark Pinnock

, and others. There are two primary perspectives on how the system is applied in detail: Classical Arminianism, which sees Arminius as its figurehead, and Wesleyan Arminianism, which (as the name suggests) sees John Wesley as its figurehead. Wesleyan Arminianism is sometimes synonymous with Methodism.

Within the broad scope of church history

, Arminianism is closely related to Calvinism (or Reformed theology), and the two systems share both history and many doctrines in common. Nonetheless, they are often viewed as archrivals within Evangelicalism because of their disagreement over the doctrines of predestination

and salvation.

doctrine during the English reformation

in the 16th and 17th centuries. The first strand is the Catholic

doctrine taught by the established church in England

in the early 16th century. The second strand is a range of Protestant reformed teachings brought to England from neighbouring countries in the same period, notably Calvinism and Lutheranism.

The Church of England was the national branch of the Catholic Church

. The formal doctrines had been documented in canon law

over the centuries, and the Church of England still follows an unbroken tradition of canon law . The English Reformation

did not dispense of all previous doctrines. The church not only retained the core Catholic beliefs common to reformed doctrine in general, such as the Trinity, the Virgin Birth

of Jesus, the nature of Jesus as fully human and fully God, the resurrection of Jesus, original sin

, and excommunication (as affirmed by the Thirty-Nine Articles

), but also retained some Catholic teachings which were rejected by true Protestants, such as the three orders of ministry

and the apostolic succession

of bishops.

in the East, 1453, led to a significant shift of gravity to the rising state of Russia

, the "Third Rome". The Renaissance would also stimulate a program of reforms by patriarchs of prayer books. A movement called the "Old believers

" consequently resulted and influenced Russian Orthodox Theology in the direction of conservatism

and Erastianism.

, the establishment of seminaries for the proper training of priests, renewed worldwide missionary activity, and the development of new yet orthodox forms of spirituality, such as that of the Spanish mystics

and the French school of spirituality

. The entire process was spearheaded by the Council of Trent

, which clarified and reasserted doctrine, issued dogmatic definitions, and produced the Roman Catechism

.

The Roman Catholic counter-reformation

spearheaded by the Jesuits under Ignatius Loyola took their theology from the decisions of the Council of Trent, and developed Second Scholasticism

, which they pitted against Lutheran Scholasticism

. The overall result of the Reformation was therefore to highlight distinctions of belief that had previously co-existed uneasily.

Though Ireland, Spain, France, and elsewhere featured significantly in the Counter-Reformation, its heart was Italy and the various popes of the time, who established the Index Librorum Prohibitorum

, or simply the "Index", a list of prohibited books, and the Roman Inquisition

, a system of juridical tribunals that prosecuted heresy and related offences. The Papacy of St. Pius V

(1566–1572) was known not only for its focus on halting heresy and worldly abuses within the Church, but also for its focus on improving popular piety in a determined effort to stem the appeal of Protestantism. Pius began his pontificate by giving large alms to the poor, charity, and hospitals, and the pontiff was known for consoling the poor and sick, and supporting missionaries. The activities of these pontiffs coincided with a rediscovery of the ancient Christian catacombs in Rome. As Diarmaid MacCulloch

stated, "Just as these ancient martyrs were revealed once more, Catholics were beginning to be martyred afresh, both in mission fields overseas and in the struggle to win back Protestant northern Europe: the catacombs proved to be an inspiration for many to action and to heroism."

The Council of Trent (1545–1563), initiated by Pope Paul III

The Council of Trent (1545–1563), initiated by Pope Paul III

(1534–1549) addressed issues of certain ecclesiastical corruptions such as simony

, absenteeism

, nepotism

, and other abuses, as well as the reassertion of traditional practices and the dogmatic articulation of the traditional doctrines of the Church, such as the episcopal structure, clerical celebacy, the seven sacraments, transubstantiation

(the belief that during mass the consecrated bread and wine truly become the body and blood of Christ), the veneration of relics, icons, and saints (especially the Blessed Virgin Mary), the necessity of both faith and good works for salvation, the existence of purgatory and the issuance (but not the sale) of indulgences, etc. The Council also fostered an interest in education for parish priests to increase pastoral care. Milan

's Archbishop St. Carlo Borromeo (1538–1584) set an example by visiting the remotest parishes and instilling high standards.

The Calvinist

and Wesleyan revival, called the Great Awakening

, established the Congregationalist

, Presbyterian, Baptist

, and new Methodist churches on competitive footing for social influence in North America. However, as that great "revival of religion" began to wane, a new era of secularism began to overwhelm the social gains that had been experienced by evangelical churches. Furthermore, that revival had popularized the strong opinion that evangelical religions were weakened and divided, primarily due to unreasonable loyalty to creeds and doctrines which made salvation, and Christian unity, seem unattainable. This sentiment gave rise to sestorationism.

was a wave of religious enthusiasm among Protestants that swept the American colonies in the 1730s and 1740s, leaving a permanent impact on American religion. It resulted from powerful preaching that deeply affected listeners (already church members) with a deep sense of personal guilt and salvation by Christ. Pulling away from ritual and ceremony, the Great Awakening made religion intensely personal to the average person by creating a deep sense of spiritual guilt and redemption. Historian Sydney E. Ahlstrom sees it as part of a "great international Protestant upheaval" that also created pietism

in Germany

, the evangelical revival

and Methodism

in England

. It brought Christianity to the slaves and was an apocalyptic event in New England

that challenged established authority. It incited rancor and division between the old traditionalists who insisted on ritual and doctrine and the new revivalists. It had a major impact in reshaping the Congregational

, Presbyterian

, Dutch Reformed

, and German Reformed denominations, and strengthened the small Baptist and Methodist

denominations. It had little impact on Anglicans

and Quakers

. Unlike the Second Great Awakening

that began about 1800 and which reached out to the unchurched, the First Great Awakening focused on people who were already church members. It changed their rituals, their piety, and their self awareness.

The new style of sermons and the way people practiced their faith breathed new life into religion in America

. People became passionately and emotionally involved in their religion, rather than passively listening to intellectual discourse in a detached manner. Ministers who used this new style of preaching were generally called "new lights", while the preachers of old were called "old lights". People began to study the Bible at home, which effectively decentralized the means of informing the public on religious manners and was akin to the individualistic trends present in Europe during the Protestant Reformation

.

history and consisted of renewed personal salvation experienced in revival meetings. Major leaders included Charles Grandison Finney

, Lyman Beecher

, Barton Stone. Peter Cartwright and James B. Finley.

In New England, the renewed interest in religion inspired a wave of social activism. In western New York

, the spirit of revival encouraged the emergence of the Restoration Movement

, Latter Day Saint movement

, Adventism and the Holiness movement. In the west especially—at Cane Ridge, Kentucky

and in Tennessee

—the revival strengthened the Methodists

and the Baptists and introduced into America a new form of religious expression—the Scottish camp meeting

.

started with John Nelson Darby

at this time, a result of disillusionment with denominationalism and clerical hierarchy.

) began from 1857 onwards in Canada and spread throughout the world including America and Australia. Significant names include Dwight L. Moody

, Ira D. Sankey

, William Booth

and Catherine Booth (founders of the Salvation Army

), Charles Spurgeon

and James Caughey. Hudson Taylor

began the China Inland Mission

and Thomas John Barnardo

founded his famous orphanages. The Keswick Convention

movement began out of the British Holiness movement

, encouraging a lifestyle of holiness

, unity and prayer.

in North America, Andrew Murray

in South Africa, and John McNeil in Australia. The Faith Mission

began in 1886.

Torrey and Alexander were involved in the beginnings of the great Welsh revival

(1904) which led Jessie Penn-Lewis

to witness the working of Satan during times of revival, and write her book "War on the Saints". In 1906 the modern Pentecostal movement was born in Azusa Street

, in Los Angeles.

of the early 19th century. The movement sought to reform the church and unite Christians. Barton W. Stone

and Alexander Campbell

each independently developed similar approaches to the Christian faith, seeking to restore the whole Christian church, on the pattern set forth in the New Testament

. Both groups believed that creeds kept Christianity divided. They joined in fellowship in 1832 with a handshake.

They were united, among other things, in the belief that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, that churches celebrate the Lord's Supper

on the first day of each week

, and that baptism of adult believers

, by immersion in water, is a necessary condition for Salvation

.

The Restoration Movement began as two separate threads, each of which initially developed without the knowledge of the other, during the Second Great Awakening in the early 19th century. The first, led by Barton W. Stone began at Cane Ridge, Bourbon County, Kentucky. The group called themselves simply Christians. The second, began in western Pennsylvania and Virginia (now West Virginia), led by Thomas Campbell and his son, Alexander Campbell. Because the founders wanted to abandon all denominational labels, they used the biblical names for the followers of Jesus that they found in the Bible. Both groups promoted a return to the purposes of the 1st century churches as described in the New Testament. One historian of the movement has argued that it was primarily a unity movement, with the restoration motif playing a subordinate role.

The Restoration Movement has seen several divisions, resulting in multiple separate groups. Three modern groups claim the Stone Campbell movement as their roots: Churches of Christ, Christian churches and churches of Christ, and the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)

. Some see divisions in the movement as the result of the tension between the goals of restoration and ecumenism, with the Churches of Christ and Christian churches and churches of Christ resolving the tension by stressing restoration while the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) resolved the tension by stressing ecumenism.

Although restorationists have some basic similarities, their doctrine and practices vary significantly. Restorationists do not usually describe themselves as "reforming" a Christian church continuously existing from the time of Jesus, but as restoring the Church that they believe was lost at some point. The name Restorationism is also used to describe the Latter Day Saint movement

. These movements have a briefly overlapping history. Other groups are also called restorationists because of their comparable goal to re-establish Christianity in its original form, such as some anti-denominational "Restorationists"

who arose in the 1970s, in Britain, and others.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with 12 million members, and Jehovah’s Witnesses with 6.6 million members.

and Chalcedonian Creed

. these included Unitarians

and Universalists. A major issue for Protestants became the degree to which Man contributes to his salvation. The debate is often viewied as synergism

versus monergism

, though the labels Calvinist and Arminian are more frequently used, referring to the conclusion of the Synod of Dort

.

The 19th century saw the rise of biblical criticism

, new knowledge of religious diversity in other continents and above all the growth of science. This led many church men to espouse a form of Deism

. This, along with concepts such as the brotherhood of man and a rejection of miracle

s led to what is called "Classic Liberalism

". Immensely influential in its day, classic liberalism suffered badly as a result of the two world wars and fell prey to the criticisms of postmodernism

.

Vladimir Lossky

is a famous Eastern Orthodox theologian writing in the 20th century for the Greek church.

as being "A Christian heresy", on the grounds that Muslims accept many of the tenets of Christianity but deny the godhood of Jesus (see Hilaire Belloc#On Islam).

However, in the second half of the century - and especially in the wake of Vatican II - the Catholic Church, in the spirit of ecumenism, tends not to refer to Protestantism

as a heresy nowadays, even if the teachings of Protestantism are indeed heretical from a Catholic perspective. Modern usage favors referring to Protestants as "separated brethren" rather than "heretics", although the latter is still on occasion used vis-a-vis Catholics who abandon their church to join a Protestant denomination. Many Catholics consider Protestantism to be material rather than formal heresy, and thus non-culpable.

Some of the doctrines of Protestantism that the Catholic Church considers heretical are the belief that the Bible

is the only source and rule of faith ("sola scriptura

"), that faith alone can lead to salvation ("sola fide

") and that there is no sacramental, ministerial priesthood attained by ordination, but only a universal priesthood of all believers.

is an understanding of Christianity that is closely associated with the body of writings known as postmodern philosophy

. Although it is a relatively recent development in the Christian

religion

, many Christian postmodernists are quick to assert that their style of thought has an affinity with foundational Christian thinkers such as Augustine of Hippo

and Thomas Aquinas

and famed Christian mystics

such as Meister Eckhart

and Angelus Silesius

.

In addition to Christian theology, postmodern Christianity has its roots in post-Heideggerian continental philosophy

, particularly the thought of Jacques Derrida. Postmodern Christianity first emerged in the early 1980s with the publication of major books about Derrida and theology authored by Carl Raschke, Mark C. Taylor, and Charles Winquist. Many people prefer to eschew the label "postmodern Christianity" because the idea of postmodernity has almost no determinate meaning and, in the United States

, serves largely to symbolize an emotionally charged battle of ideologies. Moreover, such alleged postmodern heavyweights as Jacques Derrida

and Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe

have refused to operate under a so-called postmodern rubric, preferring instead to specifically embrace a single project stemming from the Europe

an Enlightenment

and its precursors. Nevertheless, postmodern Christianity and its constituent schools of thought continue to be relevant.

Postmodern theology seeks to respond to the challenges of post modern and deconstructionist thought, and has included the death of God movement, process theology

, feminist theology

and Queer Theology and most importantly neo-orthodox Theology. Karl Barth

, Rudolf Bultmann

and Reinhold Niebuhr

were neo-orthodoxies main representatives. In particular Barth labeled his theology "dialectical theology", a reference to existentialism

.

The predominance of Classic Liberalism resulted in many reactionary

movements amongst conservative believers. Evangelical theology, Pentecostal or renewal theology and fundamentalist theology, often combined with dispensationalism

, all moved from the fringe into the academy. Marxism

stimulated the significant rise of Liberation theology

which can be interpreted as a rejection of academic theology that fails to challenge the establishment

and help the poor.

From the late 19th century to the early twentieth groups established themselves that derived many of their beliefs from Protestant evangelical groups but significantly differed in doctrine. These include the Jehovah's Witnesses

, the Latter Day Saints and many so called "cult

s". Many of these groups use the Protestant version of the Bible and typically interpret it in a fundamentalist fashion, adding, however, special prophecy or scriptures, and typically denying the trinity and the full deity of Jesus Christ.

Ecumenical Theology sought to discover a common consensus on theological matters that could bring the many Christian denominations together. As a movement it was successful in helping to provide a basis for the establishment of the World Council of Churches

and for some reconciliation between more established denominations. But ecumenical theology was nearly always the concern of liberal theologians, often Protestant ones. The movement for ecumenism was opposed especially by fundamentalists and viewed as flawed by many neo-orthodox theologians.

-- sometimes called liberal theology -- has an affinity with certain current forms of postmodern Christianity, although postmodern thought was originally a reaction against mainstream Protestant liberalism. Liberal Christianity is an umbrella term covering diverse, philosophically informed movements and moods within 19th and 20th century Christianity.

Despite its name, liberal Christianity has always been thoroughly protean. The word "liberal" in liberal Christianity does not refer to a leftist political agenda but rather to insights developed during the Enlightenment. Generally speaking, Enlightenment-era liberalism

held that man is a political creature and that liberty

of thought and expression should be his highest value. The development of liberal Christianity owes a lot to the works of philosophers Immanuel Kant

and Friedrich Schleiermacher. As a whole, liberal Christianity is a product of a continuing philosophical dialogue.

Many 20th century liberal Christians have been influenced by philosophers Edmund Husserl

and Martin Heidegger

. Examples of important liberal Christian thinkers are Rudolf Bultmann and John A.T. Robinson

.

— and political activism, especially about social justice

, poverty

, and human rights

. The Theology's principal methodological innovation is seeing theology from the perspective of the poor and the oppressed (socially, politically, etc.); per Jon Sobrino

, S.J., the poor are a privileged channel of God's grace. According to Phillip Berryman

, liberation theology is "an interpretation of Christian faith through the poor's suffering, their struggle and hope, and a critique of society and the Catholic faith and Christianity through the eyes of the poor".

Liberation theologians base their social action upon the Bible

scriptures describing the mission of Jesus Christ, as but bringing a sword

(social unrest), e.g. , , — and not as bringing peace (social order

). This Biblical interpretation is a call to action against poverty, and the sin engendering it, and as a call to arms, to effect Jesus Christ's mission of justice in this world. In practice, the Theology includes the Marxist

concept of perpetual class struggle

, thus emphasizing the person's individual self-actualization as part of God's divine purpose for mankind.

Besides teaching at (some) Roman Catholic universities and seminaries, liberation theologians often may be found working in Protestant schools, often working directly with the poor. In this context, sacred text interpretation is Christian theological praxis

.

The issue is seriously confused by the problem of terminology. "Liberation theology" is used in a technical sense to describe a particular theology which uses specific Marxist concepts. It is also used, especially by non-specialists and the media, to refer to any approach which sees Christianity as requiring political activism on behalf of the poor. It is in the first sense that the Roman Catholic hierarchy has condemned "liberation theology", rejecting especially the idea that a violent class struggle is fundamental to history, and the reinterpretation of religious phenomena such as the Exodus and the Eucharist as essentially political. The broader sense is not condemned: "The mistake here is not in bringing attention to a political dimension of the readings of Scripture, but in making of this one dimension the principal or exclusive component."

The Instruction explicitly endorsed a "preferential option for the poor", stated that one could be neutral in the face of injustice, and referred to the "crimes" of colonialism and the "scandal" of the arms race. However, media reports tended to assume that the condemnation of "liberation theology" meant a rejection of such attitudes and an endorsement of conservative politics.

These tensions have probably been worsened by the fact that many liberation theologians regard their concepts of political liberation as the only meaningful ones, and thus see little advance in the official attitudes described.

Christian existentialism

is a form of liberal Christianity that draws extensively from the writings of Søren Kierkegaard

. Kierkegaard initiated the school of thought when he reacted against Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

's claims of universal knowledge and what he deemed to be the empty formalities of the 19th century church. Christian existentialism places an emphasis on the undecidability of faith, individual passion, and the subjectivity of knowledge.

Although Kierkegaard's writings weren't initially embraced, they became widely known at the beginning of the 20th century. Later Christian existentialists synthesized Kierkegaardian themes with the works of thinkers such as Friedrich Nietzsche

, Walter Benjamin

, and Martin Buber

.

Paul Tillich

and Gabriel Marcel

are examples of leading Christian existentialist writers.

's God Without Being and John D. Caputo

's The Prayers and Tears of Jacques Derrida ushered in the era of continental philosophical theology.

is a form of philosophical theology that has been influenced by the Nouvelle Theologie

, especially of Henri de Lubac

.

An ecumenical movement begun by John Milbank

and others at Cambridge, Radical Orthodoxy seeks to examine classic Christian writings and related neoplatonic texts in full dialogue with contemporary, philosophical

perspectives. The movement finds in writers such as Augustine of Hippo and Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite

, but also in certain non-Christian writers, valuable sources of insight and meaning relevant to the supposed impasse between theology and philosophy, faith and reason, the Church and the secular. Predominantly Anglican and Roman Catholic in orientation, it has received positive responses from high places in those communions: one of the movement's founders, Catherine Pickstock, received a letter of praise from Joseph Ratzinger

before he became Pope, while Rowan Williams

, the Archbishop of Canterbury

, has contributed to the movement's publications. A major hearth of Radical Orthodoxy remains the Centre of Theology and Philosophy http://theologyphilosophycentre.co.uk/ at the University of Nottingham

.

who exists outside the confines of the human imagination.

. It is consonant with postmodern Christianity to work within existing institutions, interrupting business as usual in order to make room for marginalized voices. In such a case, the goal would not be revolution but rather a call to reform and transform existing social structures in the direction of love, hospitality, and openness.

movement. The emerging church movement seeks to revitalize the Christian church beyond what it sees as the confines of Christian fundamentalism

so that it can effectively engage with people in contemporary society. Critics allege, however, that this movement's understanding of faith has led many of its adherents outside the bounds of traditional Christianity. Brian McLaren

is a well-known author and spokesperson for the emerging church movement.

Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity defines God as three divine persons : the Father, the Son , and the Holy Spirit. The three persons are distinct yet coexist in unity, and are co-equal, co-eternal and consubstantial . Put another way, the three persons of the Trinity are of one being...

, considered the core of Christian theology

Christian theology

- Divisions of Christian theology :There are many methods of categorizing different approaches to Christian theology. For a historical analysis, see the main article on the History of Christian theology.- Sub-disciplines :...

by Trinitarians, is the result of continuous exploration by the church of the biblical data, thrashed out in debate and treatises, eventually formulated at the First Council of Nicaea

First Council of Nicaea

The First Council of Nicaea was a council of Christian bishops convened in Nicaea in Bithynia by the Roman Emperor Constantine I in AD 325...

in 325 AD in a way they believe is consistent with the biblical witness, and further refined in later councils

First seven Ecumenical Councils

In the history of Christianity, the first seven Ecumenical Councils, from the First Council of Nicaea to the Second Council of Nicaea , represent an attempt to reach an orthodox consensus and to establish a unified Christendom as the State church of the Roman Empire...

and writings. The most widely recognized Biblical foundations for the doctrine's formulation are in the Gospel of John

Gospel of John

The Gospel According to John , commonly referred to as the Gospel of John or simply John, and often referred to in New Testament scholarship as the Fourth Gospel, is an account of the public ministry of Jesus...

.

Nontrinitarianism

Nontrinitarianism

Nontrinitarianism includes all Christian belief systems that disagree with the doctrine of the Trinity, namely, the teaching that God is three distinct hypostases and yet co-eternal, co-equal, and indivisibly united in one essence or ousia...

is any of several Christian beliefs that reject the Trinitarian doctrine

Doctrine

Doctrine is a codification of beliefs or a body of teachings or instructions, taught principles or positions, as the body of teachings in a branch of knowledge or belief system...

that God is three distinct persons in one being. Modern nontrinitarian groups views differ widely on the nature of God

God in Christianity

In Christianity, God is the eternal being that created and preserves the universe. God is believed by most Christians to be immanent , while others believe the plan of redemption show he will be immanent later...

, Jesus

Jesus

Jesus of Nazareth , commonly referred to as Jesus Christ or simply as Jesus or Christ, is the central figure of Christianity...

, and the Holy Spirit

Holy Spirit

Holy Spirit is a term introduced in English translations of the Hebrew Bible, but understood differently in the main Abrahamic religions.While the general concept of a "Spirit" that permeates the cosmos has been used in various religions Holy Spirit is a term introduced in English translations of...

.

Christology

ChristologyChristology

Christology is the field of study within Christian theology which is primarily concerned with the nature and person of Jesus Christ as recorded in the Canonical gospels and the letters of the New Testament. Primary considerations include the relationship of Jesus' nature and person with the nature...

is a field of study within Christian theology which is concerned with the nature of Jesus the Christ

Christ

Christ is the English term for the Greek meaning "the anointed one". It is a translation of the Hebrew , usually transliterated into English as Messiah or Mashiach...

, particularly with how the divine and human are related in his person. Christology is generally less concerned with the details of Jesus' life than with how the human

Human

Humans are the only living species in the Homo genus...

and divine

Divinity

Divinity and divine are broadly applied but loosely defined terms, used variously within different faiths and belief systems — and even by different individuals within a given faith — to refer to some transcendent or transcendental power or deity, or its attributes or manifestations in...

co-exist in one person. Although this study of the inter-relationship of these two natures is the foundation of Christology, some essential sub-topics within the field of Christology include:

- the IncarnationIncarnation (Christianity)The Incarnation in traditional Christianity is the belief that Jesus Christ the second person of the Trinity, also known as God the Son or the Logos , "became flesh" by being conceived in the womb of a woman, the Virgin Mary, also known as the Theotokos .The Incarnation is a fundamental theological...

, - the resurrectionResurrection of JesusThe Christian belief in the resurrection of Jesus states that Jesus returned to bodily life on the third day following his death by crucifixion. It is a key element of Christian faith and theology and part of the Nicene Creed: "On the third day he rose again in fulfillment of the Scriptures"...

, - and the salvific work of Jesus (known as soteriologySoteriologyThe branch of Christian theology that deals with salvation and redemption is called Soteriology. It is derived from the Greek sōtērion + English -logy....

).

Christology is related to questions concerning the nature of God like the Trinity, Unitarianism

Unitarianism

Unitarianism is a Christian theological movement, named for its understanding of God as one person, in direct contrast to Trinitarianism which defines God as three persons coexisting consubstantially as one in being....

or Binitarianism

Binitarianism

Binitarianism is a Christian theology of two personae, two individuals, or two aspects in one Godhead . Classically, binitarianism is understood as strict monotheism — that is, that God is an absolutely single being; and yet with binitarianism there is a "twoness" in God...

. However, from a Christian perspective, these questions are concerned with how the divine persons relate to one another, whereas Christology is concerned with the meeting of the human (Son of Man

Son of man

The phrase son of man is a primarily Semitic idiom that originated in Ancient Mesopotamia, used to denote humanity or self. The phrase is also used in Judaism and Christianity. The phrase used in the Greek, translated as Son of man is ὁ υἱὸς τοὺ ἀνθρώπου...

) and divine (God the Son

God the Son

God the Son is the second person of the Trinity in Christian theology. The doctrine of the Trinity identifies Jesus of Nazareth as God the Son, united in essence but distinct in person with regard to God the Father and God the Holy Spirit...

) in the person of Jesus.

Throughout the history of Christianity

History of Christianity

The history of Christianity concerns the Christian religion, its followers and the Church with its various denominations, from the first century to the present. Christianity was founded in the 1st century by the followers of Jesus of Nazareth who they believed to be the Christ or chosen one of God...

, Christological questions have been very important in the life of the church. Christology was a fundamental concern from the First Council of Nicaea (325) until the Third Council of Constantinople

Third Council of Constantinople

The Third Council of Constantinople, counted as the Sixth Ecumenical Council by the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches and other Christian groups, met in 680/681 and condemned monoenergism and monothelitism as heretical and defined Jesus Christ as having two energies and two wills...

(680) (or the Second Council of Nicaea

Second Council of Nicaea

The Second Council of Nicaea is regarded as the Seventh Ecumenical Council by Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Eastern Catholic Churches and various other Western Christian groups...

[787]). In this time period (see also First seven Ecumenical Councils

First seven Ecumenical Councils

In the history of Christianity, the first seven Ecumenical Councils, from the First Council of Nicaea to the Second Council of Nicaea , represent an attempt to reach an orthodox consensus and to establish a unified Christendom as the State church of the Roman Empire...

), the Christological views of various groups within the broader Christian community led to accusations of heresy

Christian heresy

Christian heresy refers to non-orthodox practices and beliefs that were deemed to be heretical by one or more of the Christian churches. In Western Christianity, the term "heresy" most commonly refers to those beliefs which were declared to be anathema by the Catholic Church prior to the schism of...

, and, infrequently, subsequent religious persecution

Religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group of individuals as a response to their religious beliefs or affiliations or lack thereof....

. In some cases, a sect's unique Christology is its chief distinctive feature; in these cases it is common for the sect to be known by the name given to its Christology.

Mariology

_-_the_madonna_of_the_roses_(1903).jpg)

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Orthodox Church, officially called the Orthodox Catholic Church and commonly referred to as the Eastern Orthodox Church, is the second largest Christian denomination in the world, with an estimated 300 million adherents mainly in the countries of Belarus, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Georgia, Greece,...

, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Assyrian Church of the East

Assyrian Church of the East

The Assyrian Church of the East, officially the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East ʻIttā Qaddishtā w-Shlikhāitā Qattoliqi d-Madnĕkhā d-Āturāyē), is a Syriac Church historically centered in Mesopotamia. It is one of the churches that claim continuity with the historical...

and Anglicanism

Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a tradition within Christianity comprising churches with historical connections to the Church of England or similar beliefs, worship and church structures. The word Anglican originates in ecclesia anglicana, a medieval Latin phrase dating to at least 1246 that means the English...

, and her aspect in modern and ancient Christianity.

St. Irenaeus

Irenaeus

Saint Irenaeus , was Bishop of Lugdunum in Gaul, then a part of the Roman Empire . He was an early church father and apologist, and his writings were formative in the early development of Christian theology...

of Lyons called Mary the "second Eve

Eve

Eve is the first woman created by God in the Book of Genesis.Eve may also refer to:-People:*Eve , a common given name and surname*Eve , American recording artist and actress-Places:...

" because through Mary and her willing acceptance of God's choice, God undid the harm that was done through Eve's choice to eat the forbidden fruit

Forbidden fruit

Forbidden fruit is any object of desire whose appeal is a direct result of knowledge that cannot or should not be obtained or something that someone may want but is forbidden to have....

in the Garden of Eden

Garden of Eden

The Garden of Eden is in the Bible's Book of Genesis as being the place where the first man, Adam, and his wife, Eve, lived after they were created by God. Literally, the Bible speaks about a garden in Eden...

.

The Third Ecumenical Council debated whether she should be referred to as Theotokos

Theotokos