History of nuclear weapons

Encyclopedia

The history of nuclear weapons chronicles the development of nuclear weapons. Nuclear weapons possess enormous destructive potential derived from nuclear fission

or nuclear fusion

reactions. Starting with scientific breakthroughs of the 1930s

that made their development possible, and continuing through the nuclear arms race

and nuclear testing

of the Cold War

, the issues of proliferation

and possible use for terrorism still remain in the early 21st century.

The first fission weapons were developed jointly by the United States

, Britain

and Canada

during World War II

in what was called the Manhattan Project

to counter the assumed Nazi German atomic bomb project

. In August 1945 two were dropped on Japan

ending the Pacific War

. An international team was dispatched to help work on the project. The Soviet Union

started development shortly thereafter with their own atomic bomb project

, and not long after that both countries developed even more powerful fusion weapons called "hydrogen bombs."

During the Cold War

, the Soviet Union and United States each acquired nuclear weapons arsenals numbering in the thousands, placing many of them onto rocket

s that could hit targets anywhere in the world. Currently there are at least nine countries with functional nuclear weapons. A considerable amount of international negotiating has focused on the threat of nuclear warfare

and the proliferation

of nuclear weapons to new nations or groups.

There have been (at least) four major false alarms, the most recent in 1995, that resulted in the activation of either the US's or Russia's nuclear attack early warning protocols.

In the first decades of the twentieth century, physics

In the first decades of the twentieth century, physics

was revolutionised with developments in the understanding of the nature of atom

s. In 1898, French physicist Pierre Curie

had discovered that pitchblende

, an ore of uranium

, contained a substance—which they named radium

—that emitted large amounts of radioactivity. This raised hopes among scientists and laymen that the elements around us could contain tremendous amounts of unseen energy, waiting to be harnessed.

Experiments by Ernest Rutherford

in 1911 indicated that the vast majority of an atom's mass

was contained in a very small nucleus

at its core, made up of proton

s, surrounded by a web of electron

s. In 1932, James Chadwick

discovered that the nucleus contained another particle, the neutron

, and in the same year John Cockcroft

and Ernest Walton

"split the atom" for the first time, the first occasion on which an atomic nucleus of one element had been successfully changed to a different nucleus by artificial means.

In 1934 the idea of chain reaction via neutron was proposed by Leó Szilárd

, who patented the idea of the atomic bomb. The patent was assigned by him to the Admiralty

(the controlling organisation for Britain's Royal Navy

) in 1936, this 'sleight of hand' being necessary to prevent wider publication of the idea, as an Admiralty patent could be covered by the Official Secrets Act. In a very real sense, Szilárd was the father of the atomic bomb academically.

In 1934, French physicists Irène

and Frédéric Joliot-Curie

discovered that artificial radioactivity could be induced in stable elements by bombarding them with alpha particle

s, and in the same year Italian physicist Enrico Fermi

reported similar results when bombarding uranium with neutrons.

In December 1938, the German chemists Otto Hahn

and Fritz Strassmann

sent a manuscript to Naturwissenschaften

reporting they had detected the element barium

after bombarding uranium

with neutrons; Lise Meitner

and her nephew Otto Robert Frisch

correctly interpreted these results as being nuclear fission

. Frisch confirmed this experimentally on January 13, 1939.

Even before it was published, Meitner’s and Frisch’s interpretation of the work of Hahn and Strassmann crossed the Atlantic Ocean with Niels Bohr

, who was to lecture at Princeton University

. Isidor Isaac Rabi

and Willis Lamb

, two Columbia University

physicists working at Princeton, heard the news and carried it back to Columbia. Rabi said he told Fermi; Fermi gave credit to Lamb. Bohr soon thereafter went from Princeton to Columbia to see Fermi. Not finding Fermi in his office, Bohr went down to the cyclotron area and found Herbert Anderson. Bohr grabbed him by the shoulder and said: “Young man, let me explain to you about something new and exciting in physics.”

It was clear to a number of scientists at Columbia that they should try to detect the energy released in the nuclear fission of uranium from neutron bombardment. On January 25, 1939 an experimental team at Columbia University conducted the first nuclear fission experiment in the United States in the basement of Pupin Hall

. The team members were Herbert L. Anderson

, Eugene T. Booth

, John R. Dunning

, Enrico Fermi

, G. Norris Glasoe

, and Francis G. Slack

.

As Germany

occupied Czechoslovakia

in 1938 and then the German army marched into Poland

in 1939, beginning World War II

, many of Europe's top physicists had already begun to flee from the imminent conflict. Scientists on both sides of the conflict were well aware of the possibility of utilizing nuclear fission as a weapon, but at the time no one was quite sure how it could be done. In the early years of the war, physicists abruptly stopped publishing on the topic of fission, an act of self-censorship to keep the opposing side from gaining any advantage.

By the beginning of World War II, scientists of the Allied

By the beginning of World War II, scientists of the Allied

nations were concerned that Germany might have its own project

to develop fission-based weapons. Organized research first began in Britain as part of the "Tube Alloys

" project, and in the United States a small amount of funding was given for research into uranium weapons, starting in 1939 with the Uranium Committee under Lyman James Briggs

.

At the urging of British scientists who had made crucial calculations indicating that a fission weapon could be completed within only a few years, by 1941 the project had been wrested into better bureaucratic hands, and in 1942 came under the auspices of a Military Policy Committee led by General Leslie Groves

. This was known as the Manhattan Project

.

Its scientific team led by the American physicist Robert Oppenheimer

, the project brought together the top scientific minds of the day, including many exiles from Europe, with the production power of American industry for the goal of producing fission-based explosive devices before Germany. Britain and the U.S. agreed to pool their resources and information for the project, but the other Allied power—the Soviet Union

—was not informed.

A massive industrial and scientific undertaking, the Manhattan Project involved many of the world's leading physicists in the scientific and development aspects. The U.S. made an unprecedented investment in the project, spread across more than 30 sites in the U.S. and Canada. They centralized scientific development at Los Alamos

, a secret laboratory that was previously a small ranch school near Santa Fe

, New Mexico

.

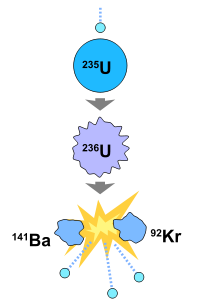

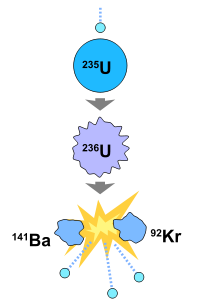

Uranium appears in nature primarily in two isotopes: uranium-238

and uranium-235

. When the nucleus of uranium-235 absorbs a neutron, it undergoes nuclear fission, splitting into two "fission products" and releasing energy and, on average, 2.5 neutrons. Uranium-238, on the other hand, absorbs neutrons but does not split, effectively putting a stop to any ongoing fission reaction.

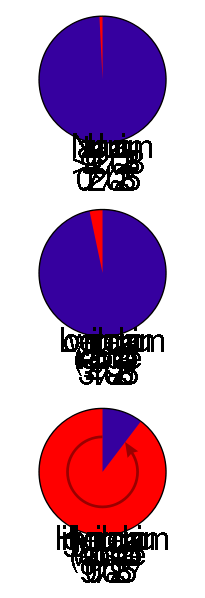

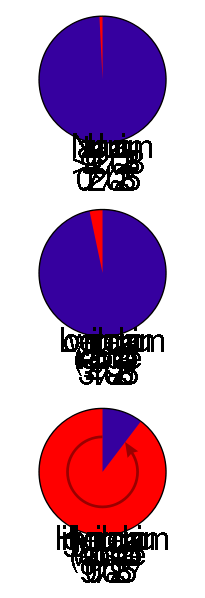

Scientists discovered that an atomic bomb based on uranium would require at least 80% pure uranium-235, otherwise the presence of uranium-238 would quickly curtail the nuclear chain reaction

. The team of scientists working at the Manhattan Project quickly realized that one of the largest problems was how to remove uranium-235 from natural uranium, which was composed of 99.3% uranium-238.

They developed two methods during the wartime project, which both took advantage of the fact that uranium-238 has a slightly greater atomic mass than uranium-235: electromagnetic separation and gaseous diffusion

—methods that separated isotopes based on their differing weights. Another secret site was erected at rural Oak Ridge, Tennessee

, for the large-scale production and purification of the rare isotope, which required considerable investment. At the time, K-25

, one of the Oak Ridge facilities, was the world's largest factory under one roof. The Oak Ridge site employed tens of thousands of employees at its peak, most of whom had no idea what they were working on.

Although uranium-238 cannot be used for the initial stage of an atomic bomb, when U-238 absorbs a neutron, it transforms first into an unstable element, uranium-239, and then decays into neptunium

Although uranium-238 cannot be used for the initial stage of an atomic bomb, when U-238 absorbs a neutron, it transforms first into an unstable element, uranium-239, and then decays into neptunium

-239, and finally the relatively stable plutonium

-239, an element that does not exist in nature. Plutonium is also fissile

and can be used to create a fission reaction, and after Enrico Fermi

achieved the world's first sustained and controlled nuclear chain reaction in the creation of the first "atomic pile"—a primitive nuclear reactor

—in a basement at the University of Chicago

, massive reactors were secretly created at what is now known as Hanford Site

in Washington State – using water from the Columbia River

in the cooling process – to transform uranium-238 into plutonium for a bomb.

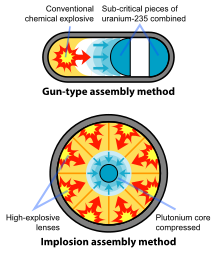

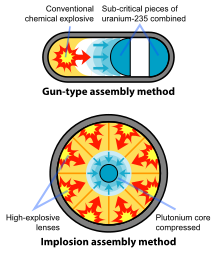

For a fission weapon to operate, there must be a critical mass—the amount needed for a self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction—of fissile material bombarded with neutrons at any one time. The simplest form of nuclear weapon is a gun-type fission weapon

, where a sub-critical mass of fissile material (such as uranium-235) would be shot at another sub-critical mass of fissile material. The result would be a super-critical mass that, when bombarded with neutrons, would undergo fission at a rapid rate and create the desired explosion. The weapons envisaged in 1942 were the two gun-type weapons, Little Boy

(uranium

) and Thin Man

(plutonium

), and the Fat Man

plutonium implosion bomb.

In early 1943 Oppenheimer determined that two projects should proceed forwards: the "Thin Man" project (plutonium gun) and the "Fat Man" project (plutonium implosion). The plutonium gun was to receive the bulk of the research effort, as it was the project with the most uncertainty involved. It was assumed that the uranium gun-type bomb could then be adapted from it.

But in April 1944 it was found by Emilio Segrè that the plutonium produced by the Hanford reactors had too high a level of background neutron radiation, and underwent spontaneous fission

But in April 1944 it was found by Emilio Segrè that the plutonium produced by the Hanford reactors had too high a level of background neutron radiation, and underwent spontaneous fission

to a very small extent, due to the presence of impurities of the Pu-240 isotope. If such plutonium were used in a "gun assembly," the chain reaction would start in the split seconds before the critical mass was assembled, blowing the weapon apart before it would have any great effect (this is known as a fizzle).

As a result, development of Fat Man

(the implosion bomb) was given high priority. Chemical explosives were used to implode a sub-critical sphere of plutonium, thus increasing its density and making it into a critical mass. The difficulties with implosion centered on the problem of making the chemical explosives deliver a perfectly uniform shock wave upon the plutonium sphere— if it were even slightly asymmetric, the weapon would fizzle (which would be expensive, messy, and not a very effective military device). This problem was circumvented by the use of hydrodynamic "lenses"—explosive materials of differing densities—which would focus the blast waves inside the imploding sphere, akin to the way in which an optical lens focuses light rays.

After D-Day

, General Groves ordered a team of scientists—Project Alsos

—to follow eastward-moving victorious Allied troops into Europe to assess the status of the German nuclear program (and to prevent the westward-moving Russians from gaining any materials or scientific manpower). They concluded that, while Germany had an atomic bomb program headed by Werner Heisenberg

, the government had not made a significant investment in the project, and it had been nowhere near success.

Historians claim to have found a rough schematic showing a Nazi nuclear bomb. Research was conducted in the German nuclear energy project

. In March 1945, a German scientific team was directed by the physicist Kurt Diebner

to develop a primitive nuclear device in Ohrdruf

, Thuringia

. Last ditch research was conducted in an experimental nuclear reactor at Haigerloch

.

At the time of the unconditional surrender of Germany on May 8, 1945, the Manhattan Project was still months away from producing a working weapon. That April, after the death of American President Franklin D. Roosevelt

, former Vice-President Harry S. Truman

was told about the secret wartime project for the first time.

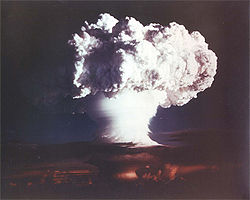

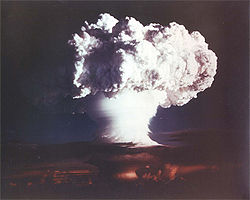

Because of the difficulties in making a working plutonium bomb

, it was decided that there should be a test of the weapon, and Truman wanted to know for certain if it would work before his meeting with Stalin

at an upcoming conference

on the future of postwar Europe. On July 16, 1945, in the desert north of Alamogordo, New Mexico

, the first nuclear test took place, code-named "Trinity

," using a device nicknamed "the Gadget." The test, a plutonium implosion type device, released the equivalent of 19 kilotons of TNT

, far more powerful than any weapon ever used before. The news of the test's success was rushed to Truman, who used it as leverage at the Potsdam conference, held near Berlin

.

After hearing arguments from scientists and military officers over the possible uses of the weapons against Japan (though some recommended using them as "demonstrations" in unpopulated areas, most recommended using them against "built up" targets, a euphemistic

After hearing arguments from scientists and military officers over the possible uses of the weapons against Japan (though some recommended using them as "demonstrations" in unpopulated areas, most recommended using them against "built up" targets, a euphemistic

term for populated cities), Truman ordered the use of the weapons on Japanese cities, hoping it would send a strong message that would end in the capitulation of the Japanese leadership and avoid a lengthy invasion of the islands.

There were suggestions to drop the atomic bomb on Tokyo

, the capital of Japan, but concerns about Tokyo's cultural heritage forced a reconsideration of this plan. On May 10–11, 1945, the Target Committee at Los Alamos, led by Oppenheimer, recommended Kyoto, Hiroshima, Yokohama, and the arsenal at Kokura as possible targets. On August 6, 1945, a uranium-based weapon, "Little Boy

," was detonated above the Japanese city of Hiroshima

. Three days later, a plutonium-based weapon, "Fat Man

," was detonated above the city of Nagasaki. The atomic bombs killed at least one hundred thousand

Japanese outright, most of them civilians, with the heat, radiation, and blast effects.

Many tens of thousands would later die of radiation sickness and related cancers. Truman promised a "rain of ruin" if Japan did not surrender immediately, threatening to eliminate Japanese cities, one by one; Japan surrendered on August 15. Truman's threat was in fact a bluff

, since the US had but one remaining uranium-gun type bomb completed.

The Soviet Union

was not invited to share in the new weapons developed by the United States and the other Allies. During the war, information had been pouring in from a number of volunteer spies involved with the Manhattan Project (known in Soviet cables under the code-name of Enormoz), and the Soviet nuclear physicist Igor Kurchatov

was carefully watching the Allied weapons development. It came as no surprise to Stalin when Truman had informed him at the Potsdam conference that he had a "powerful new weapon." Truman was shocked at Stalin's lack of interest.

The Soviet spies in the U.S. project were all volunteers and none were Russians. One of the most valuable, Klaus Fuchs

, was a German émigré theoretical physicist who had been a part in the early British nuclear efforts and had been part of the UK mission to Los Alamos during the war. Fuchs had been intimately involved in the development of the implosion weapon, and passed on detailed cross-sections of the "Trinity" device to his Soviet contacts. Other Los Alamos spies—none of whom knew each other—included Theodore Hall

and David Greenglass

. The information was kept but not acted upon, as Russia was still too busy fighting the war in Europe to devote resources to this new project.

In the years immediately after World War II, the issue of who should control atomic weapons became a major international point of contention. Many of the Los Alamos scientists who had built the bomb began to call for "international control of atomic energy," often calling for either control by transnational organizations or the purposeful distribution of weapons information to all superpowers, but due to a deep distrust of the intentions of the Soviet Union, both in postwar Europe and in general, the policy-makers of the United States worked to attempt to secure an American nuclear monopoly.

A half-hearted plan for international control was proposed at the newly formed United Nations

by Bernard Baruch

("The Baruch Plan

"), but it was clear both to American commentators—and to the Soviets—that it was an attempt primarily to stymie Russian nuclear efforts. The Soviets vetoed the plan, effectively ending any immediate postwar negotiations on atomic energy, and made overtures towards banning the use of atomic weapons in general.

All the while, the Soviets had put their full industrial and manpower might into the development of their own atomic weapons. The initial problem for the Soviets was primarily one of resources—they had not scouted out uranium resources in the Soviet Union and the U.S. had made deals to monopolise the largest known (and high purity) reserves in the Belgian Congo

. The USSR used penal labour

to mine the old deposits in Czechoslovakia

—now an area under their control—and searched for other domestic deposits (which were eventually found).

Two days after the bombing of Nagasaki, the U.S. government released an official technical history of the Manhattan Project, authored by Princeton physicist Henry DeWolf Smyth

, known colloquially as the Smyth Report

. The sanitized summary of the wartime effort focused primarily on the production facilities and scale of investment, written in part to justify the wartime expenditure to the American public.

The Soviet program, under the suspicious watch of former NKVD

chief Lavrenty Beria (a participant and victor in Stalin's Great Purge

of the 1930s), would use the Report as a blueprint, seeking to duplicate as much as possible the American effort. The "secret cities" used for the Soviet equivalents of Hanford and Oak Ridge literally vanished from the maps for decades to come.

At the Soviet equivalent of Los Alamos, Arzamas-16

, physicist Yuli Khariton led the scientific effort to develop the weapon. Beria distrusted his scientists, however, and he distrusted the carefully collected espionage information. As such, Beria assigned multiple teams of scientists to the same task without informing each team of the other's existence. If they arrived at different conclusions, Beria would bring them together for the first time and have them debate with their newfound counterparts. Beria used the espionage information as a way to double-check the progress of his scientists, and in his effort for duplication of the American project even rejected more efficient bomb designs in favor of ones that more closely mimicked the tried-and-true "Fat Man

" bomb used by the U.S. against Nagasaki.

Working under a stubborn and scientifically ignorant administrator, the Soviet scientists struggled on. On August 29, 1949, the effort brought its results, when the USSR tested its first fission bomb, dubbed "Joe-1" by the U.S., years ahead of American predictions. The news of the first Soviet bomb was announced to the world first by the United States, which had detected the nuclear fallout

it generated from its test site in Kazakhstan

.

The loss of the American monopoly on nuclear weapons marked the first tit-for-tat of the nuclear arms race

. The response in the U.S. was one of apprehension, fear, and scapegoating, which would lead eventually into the Red-baiting tactics of McCarthyism

. Yet recent information from unclassified Venona intercepts and the opening of the KGB archives after the fall of the Soviet Union show that the USSR had useful spies that helped their program, although none were identified by McCarthy. Before this, though, President Truman announced a decision to begin a crash program that would develop a far more powerful weapon than those the U.S. used against Japan: the hydrogen bomb.

can be dated back to 1942. At the first major theoretical conference on the development of an atomic bomb hosted by J. Robert Oppenheimer at the University of California, Berkeley

, participant Edward Teller

directed the majority of the discussion towards Enrico Fermi

's idea of a "Super" bomb that would use the same reactions that powered the Sun

itself.

It was thought at the time that a fission weapon would be quite simple to develop and that perhaps work on a hydrogen bomb would be possible to complete before the end of the Second World War. However, in reality the problem of a "regular" atomic bomb was large enough to preoccupy the scientists for the next few years, much less the more speculative "Super." Only Teller continued working on the project—against the will of project leaders Oppenheimer and Hans Bethe

.

After the atomic bombings of Japan, many scientists at Los Alamos

rebelled against the notion of creating a weapon thousands of times more powerful than the first atomic bombs. For the scientists the question was in part technical—the weapon design was still quite uncertain and unworkable—and in part moral: such a weapon, they argued, could only be used against large civilian populations, and could thus only be used as a weapon of genocide.

Many scientists, such as Bethe, urged that the United States should not develop such weapons and set an example towards the Soviet Union. Promoters of the weapon, including Teller, Ernest Lawrence

, and Luis Alvarez

, argued that such a development was inevitable, and to deny such protection to the people of the United States—especially when the Soviet Union was likely to create such a weapon themselves—was itself an immoral and unwise act.

Oppenheimer, who was now head of the General Advisory Committee of the successor to the Manhattan Project, the Atomic Energy Commission

, presided over a recommendation against the development of the weapon. The reasons were in part because the success of the technology seemed limited at the time (and not worth the investment of resources to confirm whether this was so), and because Oppenheimer believed that the atomic forces of the United States would be more effective if they consisted of many large fission weapons (of which multiple bombs could be dropped on the same targets) rather than the large and unwieldy predictions of massive super bombs, for which there were a relatively limited amounts of targets of the size to warrant such a development.

Furthermore, were such weapons developed by both the U.S. and the USSR, they would be more effectively used against the U.S. than by it, as the U.S. had far more regions of dense industrial and civilian activity as targets for large weapons than the Soviet Union.

In the end, President Truman made the final decision, looking for a proper response to the first Soviet atomic bomb test in 1949. On January 31, 1950, Truman announced a crash program to develop the hydrogen (fusion) bomb. At this point, however, the exact mechanism was still not known: the "classical" hydrogen bomb, whereby the heat of the fission bomb would be used to ignite the fusion material, seemed highly unworkable. However, an insight by Los Alamos mathematician Stanislaw Ulam showed that the fission bomb and the fusion fuel could be in separate parts of the bomb, and that radiation of the fission bomb could first work in a way to compress the fusion material before igniting it.

In the end, President Truman made the final decision, looking for a proper response to the first Soviet atomic bomb test in 1949. On January 31, 1950, Truman announced a crash program to develop the hydrogen (fusion) bomb. At this point, however, the exact mechanism was still not known: the "classical" hydrogen bomb, whereby the heat of the fission bomb would be used to ignite the fusion material, seemed highly unworkable. However, an insight by Los Alamos mathematician Stanislaw Ulam showed that the fission bomb and the fusion fuel could be in separate parts of the bomb, and that radiation of the fission bomb could first work in a way to compress the fusion material before igniting it.

Teller pushed the notion further, and used the results of the boosted-fission "George

" test (a boosted-fission device using a small amount of fusion fuel to boost the yield of a fission bomb) to confirm the fusion of heavy hydrogen elements before preparing for their first true multi-stage, Teller-Ulam hydrogen bomb

test. Many scientists initially against the weapon, such as Oppenheimer and Bethe, changed their previous opinions, seeing the development as being unstoppable.

The first fusion bomb was tested by the United States in Operation Ivy

on November 1, 1952, on Elugelab Island in the Enewetak (or Eniwetok) Atoll of the Marshall Islands

, code-named "Mike

." "Mike" used liquid deuterium

as its fusion fuel and a large fission weapon as its trigger. The device was a prototype design and not a deliverable weapon: standing over 20 ft (6 m) high and weighing at least 140,000 lb (64 t) (its refrigeration equipment added an additional 24000 lb (10,886.2 kg) as well), it could not have been dropped from even the largest planes.

Its explosion yielded 10.4 megatons

of energy—over 450 times the power of the bomb dropped onto Nagasaki— and obliterated Elugelab

, leaving an underwater crater 6240 ft (1.9 km) wide and 164 ft (50 m) deep where the island had once been. Truman had initially tried to create a media blackout about the test—hoping it would not become an issue in the upcoming presidential election—but on January 7, 1953, Truman announced the development of the hydrogen bomb to the world as hints and speculations of it were already beginning to emerge in the press.

Not to be outdone, the Soviet Union exploded its first thermonuclear device, designed by the physicist Andrei Sakharov

, on August 12, 1953, labeled "Joe-4" by the West. This created concern within the U.S. government and military, because, unlike "Mike," the Soviet device was a deliverable weapon, which the U.S. did not yet have. This first device though was arguably not a "true" hydrogen bomb, and could only reach explosive yields in the hundreds of kilotons (never reaching the megaton range of a "staged" weapon). Still, it was a powerful propaganda tool for the Soviet Union, and the technical differences were fairly oblique to the American public and politicians.

Following the "Mike" blast by less than a year, "Joe-4" seemed to validate claims that the bombs were inevitable and vindicate those who had supported the development of the fusion program. Coming during the height of McCarthyism

, the effect was most pronounced by the security hearings in early 1954, which revoked former Los Alamos director Robert Oppenheimer's security clearance on the grounds that he was unreliable, had not supported the American hydrogen bomb program, and had made long-standing left-wing ties in the 1930s. Edward Teller participated in the hearing as the only major scientist to testify against Oppenheimer, resulting in his virtual expulsion from the physics community.

On February 28, 1954, the U.S. detonated its first deliverable thermonuclear weapon (which used isotopes of lithium

as its fusion fuel), known as the "Shrimp" device of the "Castle Bravo

" test, at Bikini Atoll

, Marshall Islands

. The device yielded 15 megatons of energy, three times its expected yield, and became the worst radiological disaster in U.S. history. The combination of the unexpectedly large blast and poor weather conditions caused a cloud of radioactive nuclear fallout

to contaminate over 7000 square miles (18,129.9 km²), including Marshall Island natives and the crew of a Japanese fishing boat, as a snow-like mist. The contaminated islands were evacuated (and are still uninhabitable), but the natives received enough of a radioactive dose that they suffered far elevated levels of cancer

and birth defects in the years to come.

The crew of the Japanese fishing boat, Lucky Dragon 5, returned to port suffering from radiation sickness

and skin burns. Their cargo, many tons of contaminated fish, managed to enter into the market before the cause of their illness was determined. When a crew member died from the sickness and the full results of the contamination were made public by the U.S., Japanese concerns were reignited about the hazards of radiation and resulted in a boycott on eating fish (a main staple of the island country) for some weeks.

.jpg) The hydrogen bomb age had a profound effect on the thoughts of nuclear war

The hydrogen bomb age had a profound effect on the thoughts of nuclear war

in the popular and military mind. With only fission bombs, nuclear war was something that possibly could be "limited." Dropped by planes and only able to destroy the most built up areas of major cities, it was possible for many to look at fission bombs as a technological extension of large-scale conventional bombing—such as the extensive firebombing

against Japan and Germany during World War II). Proponents brushed aside as grave exaggeration claims that such weapons could lead to worldwide death or harm.

Even in the decades before fission weapons, there had been speculation about the possibility for human beings to end all life on the planet, either by accident or purposeful maliciousness—but technology had not provided the capacity for such action. The great power of hydrogen bombs made world-wide annihilation possible.

The "Castle Bravo" incident itself raised a number of questions about the survivability of a nuclear war. Government scientists in both the U.S. and the USSR had insisted that fusion weapons, unlike fission weapons, were "cleaner," as fusion reactions did not produce the dangerously radioactive by-products of fission reactions. While technically true, this hid a more gruesome point: the last stage of a multi-staged hydrogen bomb often used the neutrons produced by the fusion reactions to induce fissioning in a jacket of natural uranium, and provided around half of the yield of the device itself.

This fission stage made fusion weapons considerably more "dirty" than they were made out to be. This was evident in the towering cloud of deadly fallout that followed the Bravo test. When the Soviet Union tested its first megaton device in 1955, the possibility of a limited nuclear war seemed even more remote in the public and political mind. Even cities and countries that were not direct targets would suffer fallout contamination. Extremely harmful fission products would disperse via normal weather patterns and embed in soil and water around the planet.

Speculation began to run towards what fallout and dust from a full-scale nuclear exchange would do to the world as a whole, rather than just cities and countries directly involved. In this way, the fate of the world was now tied to the fate of the bomb-wielding superpowers.

Throughout the 1950s

Throughout the 1950s

and the early 1960s

a number of trends were enacted between the U.S. and the USSR as they both endeavored in a tit-for-tat approach to disallow the other power from acquiring nuclear supremacy. This took form in a number of ways, both technologically and politically, and had massive political and cultural effects during the Cold War

.

The first atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were large, custom-made devices, requiring highly trained personnel for their arming and deployment. They could be dropped only from the largest bomber planes—at the time the B-29 Superfortress

—and each plane could only hold a single bomb in its hold.

The first hydrogen bombs were similarly massive and complicated. This ratio of one plane to one bomb was still fairly impressive in comparison with conventional, non-nuclear weapons, but against other nuclear-armed countries it was considered a grave danger. In the immediate postwar years, the U.S. expended much effort on making the bombs "G.I.-proof"—capable of being used and deployed by members of the U.S. Army, rather than Nobel Prize–winning scientists. In the 1950s, the U.S. undertook a nuclear testing

program to improve the nuclear arsenal.

Starting in 1951, the Nevada Test Site

(in the Nevada

desert) became the primary location for all U.S. nuclear testing (in the USSR, Semipalatinsk Test Site

in Kazakhstan

served a similar role). Tests were divided into two primary categories: "weapons related" (verifying that a new weapon worked or looking at exactly how it worked) and "weapons effects" (looking at how weapons behaved under various conditions or how structures behaved when subjected to weapons).

In the beginning, almost all nuclear tests were either "atmospheric" (conducted above ground, in the atmosphere

) or "underwater" (such as some of the tests done in the Marshall Islands

). Testing was used as a sign of both national and technological strength, but also raised questions about the safety of the tests, which released nuclear fallout

into the atmosphere (most dramatically with the Castle Bravo

test in 1954, but in more limited amounts with almost all atmospheric nuclear testing).

Because testing was seen as a sign of technological development (the ability to design usable weapons without some form of testing was considered dubious), halts on testing were often called for as stand-ins for halts in the nuclear arms race

itself, and many prominent scientists and statesmen lobbied for a ban on nuclear testing. In 1958, the U.S., USSR, and the United Kingdom

(a new nuclear power) declared a temporary testing moratorium for both political and health reasons, but by 1961 the Soviet Union had broken the moratorium and both the USSR and the U.S. began testing with great frequency.

As a show of political strength, the Soviet Union tested the largest-ever nuclear weapon in October 1961, the massive Tsar Bomba

, which was tested in a reduced state with a yield of around 50 megatons

—in its full state it was estimated to have been around 100 Mt. The weapon was largely impractical for actual military use, but was hot enough to induce third-degree burns at a distance of 62 mi (100 km) away. In its full, "dirty" design, it would have increased the amount of worldwide fallout since 1945 by 25%.

In 1963, all nuclear and many non-nuclear states signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty, pledging to refrain from testing nuclear weapons in the atmosphere, underwater, or in outer space. The treaty permitted underground tests.

Most tests were considerably more modest, and worked for direct technical purposes as well as their potential political overtones. Weapons improvements took on two primary forms. One was an increase in efficiency and power, and within only a few years fission bombs were developed that were many times more powerful than the ones created during World War II. The other was a program of miniaturization, reducing the size of the nuclear weapons.

Smaller bombs meant that bombers could carry more of them, and also that they could be carried on the new generation of rocket

s in development in the 1950s and 1960s. U.S. rocket science received a large boost in the postwar years, largely with the help of engineers acquired from the Nazi rocketry program. These included scientists such as Wernher von Braun

, who had helped design the V-2 rocket

s the Nazis launched across the English Channel

. An American program, Project Paperclip, had endeavored to move German scientists into American hands (and away from Soviet hands) and put them to work for the U.S.

, first deployed by the U.S. in 1953—were surface-to-surface missiles with relatively short ranges (around 15 mi/25 km maximum) and yields around twice the size of the first fission weapons. The limited range meant they could only be used in certain types of military situations. U.S. rockets could not, for example, threaten Moscow

with an immediate strike, and could only be used as "tactical" weapons (that is, for small-scale military situations).

"Strategic" weapons—weapons that could threaten an entire country—relied, for the time being, on long-range bombers that could penetrate deep into enemy territory. In the U.S., this requirement led, in 1946, to creation of the Strategic Air Command

"Strategic" weapons—weapons that could threaten an entire country—relied, for the time being, on long-range bombers that could penetrate deep into enemy territory. In the U.S., this requirement led, in 1946, to creation of the Strategic Air Command

—a system of bomber

s headed by General Curtis LeMay

(who previously presided over the firebombing of Japan

during WWII). In operations like Chrome Dome

, SAC kept nuclear-armed planes in the air 24 hours a day, ready for an order to attack Moscow.

These technological possibilities enabled nuclear strategy

to develop a logic considerably different than previous military thinking allowed. Because the threat of nuclear warfare

was so awful, it was first thought that it might make any war of the future impossible. President Dwight D. Eisenhower

's doctrine of "massive retaliation" in the early years of the Cold War was a message to the USSR, saying that if the Red Army

attempted to invade the parts of Europe not given to the Eastern bloc

during the Potsdam Conference (such as West Germany

), nuclear weapons would be used against the Soviet troops and potentially the Soviet leaders.

With the development of more rapid-response technologies (such as rockets and long-range bombers), this policy began to shift. If the Soviet Union also had nuclear weapons and a policy of "massive retaliation" was carried out, it was reasoned, then any Soviet forces not killed in the initial attack, or launched while the attack was ongoing, would be able to serve their own form of nuclear "retaliation" against the U.S. Recognizing that this was an undesirable outcome, military officers and game theorists

at the RAND

think tank

developed a nuclear warfare strategy that was eventually called Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD).

MAD divided potential nuclear war into two stages: first strike

MAD divided potential nuclear war into two stages: first strike

and second strike

. First strike meant the first use of nuclear weapons by one nuclear-equipped nation against another nuclear-equipped nation. If the attacking nation did not prevent the attacked nation from a nuclear response, the attacked nation would respond with a second strike against the attacking nation. In this situation, whether the U.S. first attacked the USSR or the USSR first attacked the U.S., the end result would be that both nations would be damaged to the point of utter social collapse.

According to game theory, because starting a nuclear war was suicidal, no logical country would "shoot first." However, if a country could launch a first strike that utterly destroyed the target country's ability to respond, that might give that country the confidence to initiate a nuclear war. The object of a country operating by the MAD doctrine is to deny the opposing country this first strike capability.

MAD played on two seemingly opposed modes of thought: cold logic and emotional fear. The English phrase MAD was often known by , "nuclear deterrence," was translated by the French as "dissuasion," and "terrorization" by the Russians. This apparent paradox of nuclear war was summed up by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill

as "the worse things get, the better they are"—the greater the threat of mutual destruction, the safer the world would be.

This philosophy made a number of technological and political demands on participating nations. For one thing, it said that it should always be assumed that an enemy nation may be trying to acquire first strike capability, which must always be avoided. In American politics this translated into demands to avoid "bomber gap

s" and "missile gap

s" where the Soviet Union could potentially "out shoot" the Americans. It also encouraged the production of thousands of nuclear weapons by both the U.S. and the USSR, far more than needed to simply destroy the major civilian and military infrastructures of the opposing country.

These policies and strategies were satirized in the 1964 Stanley Kubrick

film Dr. Strangelove, in which the Soviets, unable to keep up with the US's first strike capability, instead plan for MAD by building a Doomsday Machine

, and thus, after a (literally) mad US General orders a nuclear attack on the USSR, the end of the world is brought about.

The policy also encouraged the development of the first early warning systems. Conventional war, even at its fastest, was fought over days and weeks. With long-range bombers, from the start of an attack to its conclusion was mere hours. Rockets could reduce a conflict to minutes. Planners reasoned that conventional command and control

The policy also encouraged the development of the first early warning systems. Conventional war, even at its fastest, was fought over days and weeks. With long-range bombers, from the start of an attack to its conclusion was mere hours. Rockets could reduce a conflict to minutes. Planners reasoned that conventional command and control

systems could not adequately react to a nuclear attack, so great lengths were taken to develop computer

s that could look for enemy attacks and direct rapid responses.

The U.S., poured massive funding into development of SAGE

, a system that could track and intercept enemy bomber aircraft using information from remote radar

stations. It was the first computer system to feature real-time

processing, multiplexing

, and display device

s. It was the first "general" computing machine, and a direct predecessor of modern computers.

, both the United States and the Soviet Union had developed intercontinental ballistic missile

s, which could be launched from extremely remote areas far away from their target. They had also developed submarine-launched ballistic missile

s, which had less range but could be launched from submarines very close to the target without any radar warning. This made any national protection from nuclear missiles increasingly impractical.

The military realities made for a precarious diplomatic situation. The international politics of brinkmanship

led leaders to exclaim their willingness to participate in a nuclear war rather than concede any advantage to their opponents, feeding public fears that their generation may be the last. Civil defense

programs undertaken by both superpowers, exemplified by the construction of fallout shelters and urging civilians about the "survivability" of nuclear war, did little to ease public concerns.

The climax of brinksmanship came in early 1962, when an American U-2

The climax of brinksmanship came in early 1962, when an American U-2

spy plane photographed a series of launch sites for medium-range ballistic missiles being constructed on the island of Cuba

, just off the coast of the southern United States, beginning what became known as the Cuban Missile Crisis

. The U.S. administration of John F. Kennedy

concluded that the Soviet Union, then led by Nikita Khrushchev

, was planning to station Russian nuclear missiles on the island, which was under the control of Communist Fidel Castro

. On October 22, Kennedy announced the discoveries in a televised address. He announced a naval blockade

around Cuba that would turn back Soviet nuclear shipments, and warned that the military was prepared "for any eventualities." The missiles had 2,400 mile (4,000 km) range, and would allow the Soviet Union to quickly destroy many major American cities on the Eastern Seaboard

if a nuclear war began.

The leaders of the two superpowers stood nose to nose, seemingly poised over the beginnings of a third world war

. Khrushchev's ambitions for putting the weapons on the island were motivated in part by the fact that the U.S. had stationed similar weapons in Britain

, Italy

, and nearby Turkey

, and had previously attempted to sponsor an invasion of Cuba the year before in the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion

. On October 26, Khrushchev sent a message to Kennedy offering to withdraw all missiles if Kennedy committed to a policy of no future invasions of Cuba. Khrushchev worded the threat of assured destruction eloquently:

A day later, however, the Russians sent another message, this time demanding that the U.S. remove its missiles from Turkey before any missiles were withdrawn from Cuba. On the same day, a U-2 plane was shot down over Cuba and another almost intercepted over Russia, as Soviet merchant ships neared the quarantine zone. Kennedy responded by accepting the first deal publicly, and sending his brother Robert to the Soviet embassy to accept the second deal privately.

On October 28, the Soviet ships stopped at the quarantine line and, after some hesitation, turned back towards the Soviet Union. Khrushchev announced that he had ordered the removal of all missiles in Cuba, and U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk

was moved to comment, "We went eyeball to eyeball, and the other fellow just blinked."

The Crisis was later seen as the closest the U.S. and the USSR ever came to nuclear war and had been narrowly averted by last-minute compromise by both superpowers. Fears of communication difficulties led to the installment of the first hotline

, a direct link between the superpowers that allowed them to more easily discuss future military activities and political maneuverings. It had been made clear that missiles, bombers, submarines, and computerized firing systems made escalating any situation to Armageddon far more easy than anybody desired.

After stepping so close to the brink, both the U.S. and the USSR worked to reduce their nuclear tensions in the years immediately following. The most immediate culmination of this work was the signing of the Partial Test Ban Treaty

in 1963, in which the U.S. and USSR agreed to no longer test nuclear weapons in the atmosphere, underwater, or in outer space. Testing underground continued, allowing for further weapons development, but the worldwide fallout risks were purposefully reduced, and the era of using massive nuclear tests as a form of saber-rattling ended.

In December 1979, NATO decided to deploy cruise and Pershing II missiles in Western Europe in response to Soviet deployment of intermediate range mobile missiles, and in the early 1980s, a "dangerous Soviet-US nuclear confrontation" arose. In New York on June 12, 1982, one million people gathered to protest nuclear weapons, and to support the second UN Special Session on Disarmament. As the nuclear abolitionist movement grew, there were many protests at the Nevada Test Site

. For example, on February 6, 1987, nearly 2,000 demonstrators, including six members of Congress, protested against nuclear weapons testing and more than 400 people were arrested. Four of the significant groups organizing this renewal of anti-nuclear activism

were Greenpeace

, The American Peace Test, The Western Shoshone, and Nevada Desert Experience

.

The United Kingdom had been an integral part of the Manhattan Project

following the Quebec Agreement

in 1943. The passing of the McMahon Act by the United States in 1946 unilaterally broke this partnership and prevented the passage of any further information to the United Kingdom. The British Government, under Clement Attlee

, determined that a British Bomb was essential. Because of British involvement in the Manhattan Project, Britain had extensive knowledge in some areas, but not in others.

An improved version of 'Fat Man' was developed, and on 26 February 1952, Prime Minister Winston Churchill

announced that the United Kingdom also had an atomic bomb and a successful test

took place on the 3rd October 1952. At first these were free-fall bombs, intended for use by the V Force

of jet bombers. A Vickers Valiant

dropped the first UK nuclear weapon on 11 October 1956 at Maralinga, South Australia

. Later came a missile, Blue Steel

, intended for carriage by the V Force bombers, and then the Blue Streak

medium-range ballistic missile

(later canceled). Anglo-American cooperation on Nuclear weapons was restored by the 1958 US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement

. As a result of this and the Polaris Sales Agreement

, the United Kingdom has bought United States designs for submarine missiles and fitted its own warheads. It retains full independent control over the use of the missiles. It no longer possesses any free-fall bombs.

France had been heavily involved in nuclear research before World War II

through the work of the Joliot-Curie

s. This was discontinued after the war because of the instability of the Fourth Republic

and lack of finances. However, in the 1950s, France launched a civil nuclear research program, which produced plutonium as a byproduct.

In 1956, France formed a secret Committee for the Military Applications of Atomic Energy and a development program for delivery vehicles. With the return of Charles de Gaulle

to the French presidency in 1958, final decisions to build a bomb were made, which led to a successful test in 1960. Since then, France has developed and maintained its own nuclear deterrent

.

In 1951, China and the Soviet Union signed an agreement whereby China supplied uranium ore in exchange for technical assistance in producing nuclear weapons. In 1953, China established a research program under the guise of civilian nuclear energy. Throughout the 1950s the Soviet Union provided large amounts of equipment. But as the relations between the two countries worsened the Soviets reduced the amount of assistance and, in 1959, refused to donate a bomb for copying purposes. Despite this, the Chinese made rapid progress and tested an atomic bomb on the October 16, 1964 at Lop Nur

. They tested a nuclear missile on October 25, 1966, and a hydrogen bomb on June 14, 1967.

Chinese nuclear warheads were produced from 1968 and thermonuclear warheads from 1974. It is also thought that Chinese warheads have been successfully miniaturised from 2200 kg to 700 kg through the use of designs obtained by espionage

from the United States. The current number of weapons is unknown owing to strict secrecy, but it is thought that up to 2000 warheads may have been produced, though far fewer may be available for use. China is the only nuclear weapons state to have guaranteed the non-first use of nuclear weapons.

After World War II, the balance of power

After World War II, the balance of power

between the Eastern and Western blocs and the fear of global destruction prevented the further military use of atomic bombs. This fear was even a central part of Cold War

strategy, referred to as the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction ("MAD" for short). So important was this balance to international political stability that a treaty, the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty

(or ABM treaty), was signed by the U.S. and the USSR

in 1972 to curtail the development of defenses against nuclear weapons and the ballistic missile

s that carry them. This doctrine resulted in a large increase in the number of nuclear weapons, as each side sought to ensure it possessed the firepower to destroy the opposition in all possible scenarios and against all perceived threats.

Early delivery systems for nuclear devices were primarily bombers like the United States B-29 Superfortress

and Convair B-36

, and later the B-52 Stratofortress

. Ballistic missile systems, based on Wernher von Braun

's World War II designs (specifically the V2 rocket), were developed by both United States and Soviet Union teams (in the case of the U.S., effort was directed by the German scientists and engineers although the Soviet Union also made extensive use of captured German scientists, engineers, and technical data).

These systems were used to launch satellites, such as Sputnik, and to propel the Space Race

, but they were primarily developed to create Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) that could deliver nuclear weapons anywhere on the globe. Development of these systems continued throughout the Cold War

—though plans and treaties, beginning with the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT I), restricted deployment of these systems until, after the fall of the Soviet Union, system development essentially halted, and many weapons were disabled and destroyed (see nuclear disarmament

).

There have been a number of potential nuclear disasters. Following air accidents U.S. nuclear weapons have been lost near Atlantic City, New Jersey

(1957); Savannah, Georgia

(1958) (see Tybee Bomb

); Goldsboro, North Carolina

(1961); off the coast of Okinawa (1965); in the sea near Palomares

, Spain

(1966) (see 1966 Palomares B-52 crash); and near Thule, Greenland (1968) (see 1968 Thule Air Base B-52 crash). Most of the lost weapons were recovered, the Spanish device after three months' effort by the DSV Alvin

and DSV Aluminaut

.

The Soviet Union was less forthcoming about such incidents, but the environmental group Greenpeace

believes that there are around forty non-U.S. nuclear devices that have been lost and not recovered, compared to eleven lost by America, mostly in submarine disasters. The U.S. has tried to recover Soviet devices, notably in the 1974 Operation Jennifer using the specialist salvage vessel Hughes Glomar Explorer.

On January 27, 1967, more than 60 nations signed the Outer Space Treaty

, banning nuclear weapons in space.

The end of the Cold War

failed to end the threat of nuclear weapon use, although global fears of nuclear war

reduced substantially.

In a major move of symbolic de-escalation, Boris Yeltsin

, on January 26, 1992, announced that Russia

planned to stop targeting United States

cities with nuclear weapons.

, the second nuclear age—proliferation of nuclear weapons

among lesser powers and for reasons other than the American-Soviet rivalry—really began with the end of the Cold War.

After the collapse of Eastern Military High Command

and the disintegration

of Pakistan as a result of 1971 Winter war

, Bhutto

of Pakistan launched and embarked the scientific research on nuclear weapons. This programme was delegated to Munir Ahmad Khan

, Abdul Qadeer Khan

, and Salam

who later go on to win the Nobel Prize

. India's first atomic-test explosion was in 1974 with Smiling Buddha

, which it described as a "peaceful nuclear explosion". The Indian test caused Pakistan to spurred its programme, and with Dr. A. Q. Khan, the ISI conduct successful espionage operations in the Netherlands, while also developing the programme ingeniously on the other side. India

tested fission and perhaps fusion devices in 1998 (See Shakti), and Pakistan successfully tested fission devices that same year (See Chagai-I

), raising concerns that they would use nuclear weapons on each other. All of the former Soviet bloc countries with nuclear weapons (Belarus

, Ukraine

, and Kazakhstan

) returned their warheads to Russia

by 1996.

In January 2004, metallurgist and top weapon scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan confessed to having been a part of an international proliferation

network of materials, knowledge, and machines from Pakistan to Libya

, Iran

, and North Korea

.

South Africa

also had an active program to develop uranium-based nuclear weapons, but dismantled its nuclear weapon program in the 1990s

. Experts do not believe it actually tested such a weapon, though it later claimed it constructed several crude devices that it eventually dismantled. In the late 1970s

American spy satellites detected a "brief, intense, double flash of light near the southern tip of Africa." Known as the Vela Incident

, it was speculated to have been a South African or possibly Israeli nuclear weapons test, though some feel that it may have been caused by natural events or a detector malfunction.

Israel

is widely believed to possess an arsenal of potentially up to several hundred nuclear warheads, but this has never been officially confirmed or denied (though the existence of their Dimona nuclear facility

was confirmed by Mordechai Vanunu

in 1986).

North Korea announced in 2003 that it also had several nuclear explosives though it has not been confirmed and the validity of this has been a subject of scrutiny amongst weapons experts. The first detonation of a nuclear weapon

by the Democratic People's Republic of Korea was the 2006 North Korean nuclear test

, conducted on October 9, 2006. On May 25, 2009 North Korea continued nuclear testing, violating United Nations Security Council Resolution 1718

.

In Iran

, Ayatollah

Ali Khamenei

issued a fatwa

forbidding the production, stockpiling and use of nuclear weapons on August 9, 2005. The full text of the fatwa was released in an official statement at the meeting of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in Vienna. Despite this, however, there is mounting concern in many nations about Iran's refusal to halt its nuclear power program, which many (including some members of the US government) fear is a cover for weapons development. (See Iran and weapons of mass destruction

.)

Nuclear fission

In nuclear physics and nuclear chemistry, nuclear fission is a nuclear reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into smaller parts , often producing free neutrons and photons , and releasing a tremendous amount of energy...

or nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion is the process by which two or more atomic nuclei join together, or "fuse", to form a single heavier nucleus. This is usually accompanied by the release or absorption of large quantities of energy...

reactions. Starting with scientific breakthroughs of the 1930s

1930s

File:1930s decade montage.png|From left, clockwise: Dorothea Lange's photo of the homeless Florence Thompson show the effects of the Great Depression; Due to the economic collapse, the farms become dry and the Dust Bowl spreads through America; The Battle of Wuhan during the Second Sino-Japanese...

that made their development possible, and continuing through the nuclear arms race

Nuclear arms race

The nuclear arms race was a competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War...

and nuclear testing

Nuclear testing

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine the effectiveness, yield and explosive capability of nuclear weapons. Throughout the twentieth century, most nations that have developed nuclear weapons have tested them...

of the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

, the issues of proliferation

Nuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is a term now used to describe the spread of nuclear weapons, fissile material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information, to nations which are not recognized as "Nuclear Weapon States" by the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons, also known as the...

and possible use for terrorism still remain in the early 21st century.

The first fission weapons were developed jointly by the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, Britain

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

and Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

in what was called the Manhattan Project

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program, led by the United States with participation from the United Kingdom and Canada, that produced the first atomic bomb during World War II. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army...

to counter the assumed Nazi German atomic bomb project

German nuclear energy project

The German nuclear energy project, , was an attempted clandestine scientific effort led by Germany to develop and produce the atomic weapons during the events involving the World War II...

. In August 1945 two were dropped on Japan

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

During the final stages of World War II in 1945, the United States conducted two atomic bombings against the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, the first on August 6, 1945, and the second on August 9, 1945. These two events are the only use of nuclear weapons in war to date.For six months...

ending the Pacific War

Pacific War

The Pacific War, also sometimes called the Asia-Pacific War refers broadly to the parts of World War II that took place in the Pacific Ocean, its islands, and in East Asia, then called the Far East...

. An international team was dispatched to help work on the project. The Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

started development shortly thereafter with their own atomic bomb project

Soviet atomic bomb project

The Soviet project to develop an atomic bomb , was a clandestine research and development program began during and post-World War II, in the wake of the Soviet Union's discovery of the United States' nuclear project...

, and not long after that both countries developed even more powerful fusion weapons called "hydrogen bombs."

During the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

, the Soviet Union and United States each acquired nuclear weapons arsenals numbering in the thousands, placing many of them onto rocket

Rocket

A rocket is a missile, spacecraft, aircraft or other vehicle which obtains thrust from a rocket engine. In all rockets, the exhaust is formed entirely from propellants carried within the rocket before use. Rocket engines work by action and reaction...

s that could hit targets anywhere in the world. Currently there are at least nine countries with functional nuclear weapons. A considerable amount of international negotiating has focused on the threat of nuclear warfare

Nuclear warfare

Nuclear warfare, or atomic warfare, is a military conflict or political strategy in which nuclear weaponry is detonated on an opponent. Compared to conventional warfare, nuclear warfare can be vastly more destructive in range and extent of damage...

and the proliferation

Nuclear proliferation

Nuclear proliferation is a term now used to describe the spread of nuclear weapons, fissile material, and weapons-applicable nuclear technology and information, to nations which are not recognized as "Nuclear Weapon States" by the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons, also known as the...

of nuclear weapons to new nations or groups.

There have been (at least) four major false alarms, the most recent in 1995, that resulted in the activation of either the US's or Russia's nuclear attack early warning protocols.

Physics and politics in the 1930s

- See the main articles at History of physicsHistory of physicsAs forms of science historically developed out of philosophy, physics was originally referred to as natural philosophy, a term describing a field of study concerned with "the workings of nature".-Early history:...

, Nazi GermanyNazi GermanyNazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

and World War IIWorld War IIWorld War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

.

Physics

Physics is a natural science that involves the study of matter and its motion through spacetime, along with related concepts such as energy and force. More broadly, it is the general analysis of nature, conducted in order to understand how the universe behaves.Physics is one of the oldest academic...

was revolutionised with developments in the understanding of the nature of atom

Atom

The atom is a basic unit of matter that consists of a dense central nucleus surrounded by a cloud of negatively charged electrons. The atomic nucleus contains a mix of positively charged protons and electrically neutral neutrons...

s. In 1898, French physicist Pierre Curie

Pierre Curie

Pierre Curie was a French physicist, a pioneer in crystallography, magnetism, piezoelectricity and radioactivity, and Nobel laureate. He was the son of Dr. Eugène Curie and Sophie-Claire Depouilly Curie ...

had discovered that pitchblende

Uraninite

Uraninite is a radioactive, uranium-rich mineral and ore with a chemical composition that is largely UO2, but also contains UO3 and oxides of lead, thorium, and rare earth elements...

, an ore of uranium

Uranium

Uranium is a silvery-white metallic chemical element in the actinide series of the periodic table, with atomic number 92. It is assigned the chemical symbol U. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons...

, contained a substance—which they named radium

Radium

Radium is a chemical element with atomic number 88, represented by the symbol Ra. Radium is an almost pure-white alkaline earth metal, but it readily oxidizes on exposure to air, becoming black in color. All isotopes of radium are highly radioactive, with the most stable isotope being radium-226,...

—that emitted large amounts of radioactivity. This raised hopes among scientists and laymen that the elements around us could contain tremendous amounts of unseen energy, waiting to be harnessed.

Experiments by Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson OM, FRS was a New Zealand-born British chemist and physicist who became known as the father of nuclear physics...

in 1911 indicated that the vast majority of an atom's mass

Atomic mass

The atomic mass is the mass of a specific isotope, most often expressed in unified atomic mass units. The atomic mass is the total mass of protons, neutrons and electrons in a single atom....

was contained in a very small nucleus

Atomic nucleus

The nucleus is the very dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom. It was discovered in 1911, as a result of Ernest Rutherford's interpretation of the famous 1909 Rutherford experiment performed by Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, under the direction of Rutherford. The...

at its core, made up of proton

Proton

The proton is a subatomic particle with the symbol or and a positive electric charge of 1 elementary charge. One or more protons are present in the nucleus of each atom, along with neutrons. The number of protons in each atom is its atomic number....

s, surrounded by a web of electron

Electron

The electron is a subatomic particle with a negative elementary electric charge. It has no known components or substructure; in other words, it is generally thought to be an elementary particle. An electron has a mass that is approximately 1/1836 that of the proton...

s. In 1932, James Chadwick

James Chadwick

Sir James Chadwick CH FRS was an English Nobel laureate in physics awarded for his discovery of the neutron....

discovered that the nucleus contained another particle, the neutron

Neutron

The neutron is a subatomic hadron particle which has the symbol or , no net electric charge and a mass slightly larger than that of a proton. With the exception of hydrogen, nuclei of atoms consist of protons and neutrons, which are therefore collectively referred to as nucleons. The number of...

, and in the same year John Cockcroft

John Cockcroft

Sir John Douglas Cockcroft OM KCB CBE FRS was a British physicist. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physics for splitting the atomic nucleus with Ernest Walton, and was instrumental in the development of nuclear power....

and Ernest Walton

Ernest Walton

Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton was an Irish physicist and Nobel laureate for his work with John Cockcroft with "atom-smashing" experiments done at Cambridge University in the early 1930s, and so became the first person in history to artificially split the atom, thus ushering the nuclear age...

"split the atom" for the first time, the first occasion on which an atomic nucleus of one element had been successfully changed to a different nucleus by artificial means.

In 1934 the idea of chain reaction via neutron was proposed by Leó Szilárd

Leó Szilárd

Leó Szilárd was an Austro-Hungarian physicist and inventor who conceived the nuclear chain reaction in 1933, patented the idea of a nuclear reactor with Enrico Fermi, and in late 1939 wrote the letter for Albert Einstein's signature that resulted in the Manhattan Project that built the atomic bomb...

, who patented the idea of the atomic bomb. The patent was assigned by him to the Admiralty

Admiralty

The Admiralty was formerly the authority in the Kingdom of England, and later in the United Kingdom, responsible for the command of the Royal Navy...

(the controlling organisation for Britain's Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

) in 1936, this 'sleight of hand' being necessary to prevent wider publication of the idea, as an Admiralty patent could be covered by the Official Secrets Act. In a very real sense, Szilárd was the father of the atomic bomb academically.

In 1934, French physicists Irène

Irène Joliot-Curie

Irène Joliot-Curie was a French scientist, the daughter of Marie Skłodowska-Curie and Pierre Curie and the wife of Frédéric Joliot-Curie. Jointly with her husband, Joliot-Curie was awarded the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1935 for their discovery of artificial radioactivity. This made the Curies...

and Frédéric Joliot-Curie

Frédéric Joliot-Curie

Jean Frédéric Joliot-Curie , born Jean Frédéric Joliot, was a French physicist and Nobel laureate.-Early years:...

discovered that artificial radioactivity could be induced in stable elements by bombarding them with alpha particle

Alpha particle

Alpha particles consist of two protons and two neutrons bound together into a particle identical to a helium nucleus, which is classically produced in the process of alpha decay, but may be produced also in other ways and given the same name...

s, and in the same year Italian physicist Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi was an Italian-born, naturalized American physicist particularly known for his work on the development of the first nuclear reactor, Chicago Pile-1, and for his contributions to the development of quantum theory, nuclear and particle physics, and statistical mechanics...

reported similar results when bombarding uranium with neutrons.

In December 1938, the German chemists Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn

Otto Hahn FRS was a German chemist and Nobel laureate, a pioneer in the fields of radioactivity and radiochemistry. He is regarded as "the father of nuclear chemistry". Hahn was a courageous opposer of Jewish persecution by the Nazis and after World War II he became a passionate campaigner...

and Fritz Strassmann

Fritz Strassmann

Friedrich Wilhelm "Fritz" Strassmann was a German chemist who, with Otto Hahn in 1938, identified barium in the residue after bombarding uranium with neutrons, which led to the interpretation of their results as being from nuclear fission...

sent a manuscript to Naturwissenschaften

Die Naturwissenschaften

Naturwissenschaften is a monthly peer-reviewed scientific journal published by Springer on behalf of several learned societies.- History :...

reporting they had detected the element barium

Barium

Barium is a chemical element with the symbol Ba and atomic number 56. It is the fifth element in Group 2, a soft silvery metallic alkaline earth metal. Barium is never found in nature in its pure form due to its reactivity with air. Its oxide is historically known as baryta but it reacts with...

after bombarding uranium

Uranium

Uranium is a silvery-white metallic chemical element in the actinide series of the periodic table, with atomic number 92. It is assigned the chemical symbol U. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons...

with neutrons; Lise Meitner

Lise Meitner

Lise Meitner FRS was an Austrian-born, later Swedish, physicist who worked on radioactivity and nuclear physics. Meitner was part of the team that discovered nuclear fission, an achievement for which her colleague Otto Hahn was awarded the Nobel Prize...

and her nephew Otto Robert Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch

Otto Robert Frisch , Austrian-British physicist. With his collaborator Rudolf Peierls he designed the first theoretical mechanism for the detonation of an atomic bomb in 1940.- Overview :...

correctly interpreted these results as being nuclear fission

Nuclear fission

In nuclear physics and nuclear chemistry, nuclear fission is a nuclear reaction in which the nucleus of an atom splits into smaller parts , often producing free neutrons and photons , and releasing a tremendous amount of energy...

. Frisch confirmed this experimentally on January 13, 1939.

Even before it was published, Meitner’s and Frisch’s interpretation of the work of Hahn and Strassmann crossed the Atlantic Ocean with Niels Bohr

Niels Bohr

Niels Henrik David Bohr was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum mechanics, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922. Bohr mentored and collaborated with many of the top physicists of the century at his institute in...

, who was to lecture at Princeton University

Princeton University