History of Australia

Encyclopedia

The History of Australia refers to the history of the area and people of Commonwealth of Australia and its preceding Indigenous and colonial societies. Aboriginal Australians are believed to have first arrived on the Australian mainland by boat from the Indonesian archipelago between 40,000 to 60,000 years ago. They established among the longest surviving artistic, musical and spiritual traditions known on earth.

The first uncontested landing in Australia by Europeans was by Dutch

navigator Willem Janszoon

in 1606. European explorers followed intermittently until, in 1770, James Cook

charted the East Coast of Australia for Britain

and returned with accounts favouring colonisation at Botany Bay

(now in Sydney), New South Wales

. A First Fleet

of British ships arrived at Sydney in January 1788 to establish a penal colony

. Other colonies were established by Britain around the continent and European explorers

sent deep into the interior throughout the 19th century. Introduced disease and conflict with the British colonists greatly weakened Indigenous Australia throughout the period.

Gold rushes

and agricultural industries brought prosperity and autonomous Parliamentary democracies began to be established throughout the six British colonies from the mid-19th century. The colonies voted by referendum

to unite in a federation

in 1901, and modern Australia came into being. Australia fought on the side of Britain in the World Wars and became a long-standing ally of the United States

when threatened by Imperial Japan during World War II

. Trade with Asia increased and a post-war multicultural immigration program received more than 6.5 million migrants from every continent. The population tripled in the six decades to around 21 million in 2010, with people originating from 200 countries sustaining the 14th biggest economy in the world.

are believed to have arrived in Australia some 40,000 to 60,000 years ago, but possibly as early as 70,000 years ago. They developed a hunter-gatherer

lifestyle, established enduring spiritual

and artistic traditions and utilised stone technologies

. At the time of first Europe

an contact, it has been estimated the existing population was at least 350,000, while recent archaeological finds suggest that a population of 750,000 could have been sustained. People appear to have arrived by sea during a period of glaciation, when New Guinea

and Tasmania

were joined to the continent. The journey still required sea travel however, making them amongst the world’s earlier mariners.

The greatest population density developed in the southern and eastern regions, the River Murray valley in particular. Aborigines lived and utilised resources on the continent sustainably, agreeing to cease hunting and gathering at particular times to give populations and resources the chance to replenish. "Firestick farming" amongst northern Australian people was used to encourage plant growth that attracted animals. Aborigines were amongst the oldest, most sustainable and most isolated cultures on Earth prior to European settlement. The arrival of Australia's first people nevertheless affected the continent significantly, and, along with climate change, may have contributed to the extinction of Australia's megafauna

. The introduction of the dingo

dog by Aboriginal people around 3000–4000 years ago may, along with human hunting, have contributed to the extinction of the thylacine

, Tasmanian Devil

, and Tasmanian Native-hen

from mainland Australia.

The earliest human remains found to date are those found at Lake Mungo, a dry lake in the south west of New South Wales. Remains found at Mungo suggest one of the world's oldest known cremation

s, thus indicating early evidence for religious ritual among humans. According to Australian Aboriginal mythology

and the animist framework of the descendants of these early Australians, the Dreaming

is a sacred

era in which ancestral Totem

ic Spirit Beings formed The Creation. The Dreaming established the laws and structures of society and the ceremonies performed to ensure continuity of life and land. It was and remains a prominent feature of Australian Aboriginal art

.

Aboriginal art is believed to be the oldest continuing tradition of art in the world. Evidence of Aboriginal art can be traced back at least 30,000 years and is found throughout Australia (notably at Uluru

and Kakadu National Park

in the Northern Territory). In terms of age and abundance, cave art in Australia is comparable to that of Lascaux

and Altamira in Europe.

Despite considerable cultural continuity, life for Aborigines was not without significant changes. Some 10-12,000 years ago, Tasmania became isolated from the mainland, and some stone technologies failed to reach the Tasmanian people (such as the hafting of stone tools and the use of the Boomerang

). The land was not always kind; Aboriginal people of southeastern Australia endured "more than a dozen volcanic eruptions…(including) Mount Gambier

, a mere 1,400 years ago." There is evidence that when necessary, Aborigines could keep control of their population growth and in times of drought or arid areas were able to maintain reliable water supplies. In south eastern Australia, near present day Lake Condah, semi-permanent villages of beehive shaped shelters of stone developed, near bountiful food supplies. For centuries, Macassan

trade flourished with Aborigines on Australia's north coast, particularly with the Yolngu

people of northeast Arnhem Land

.

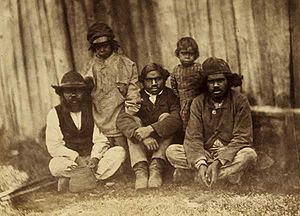

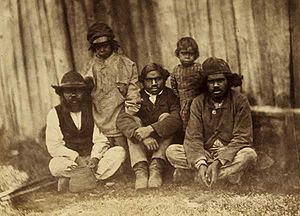

By 1788, the population existed as 250 individual nations, many of which were in alliance with one another, and within each nation there existed several clans, from as few as five or six to as many as 30 or 40. Each nation had its own language and a few had multiple, thus over 250 languages existed, around 200 of which are now extinct. "Intricate kinship rules ordered the social relations of the people and diplomatic messengers and meeting rituals smoothed relations between groups," keeping group fighting, sorcery and domestic disputes to a minimum.

The mode of life and material cultures varied greatly from nation to nation. Some early European observers like William Dampier

described the hunter-gatherer lifestyle of the Aborigines as arduous and "miserable". Captain Cook on the other hand, speculated in his journal that the "Natives of New Holland" might in fact be far happier than Europeans. Watkin Tench

, of the First Fleet

, wrote of an admiration for the Aborigines of Sydney as good natured and good humoured people, though he also reported violent hostility between the Eora

and Cammeraygal

peoples, and noted violent domestic altercations between his friend Bennelong

and his wife Barangaroo

. 19th century settlers like Edward Curr observed that Aborigines "suffered less and enjoyed life more than the majority of civilized(sic) men." Historian Geoffrey Blainey

wrote that the material standard of living for Aborigines was generally high, higher than that of many Europeans living at the time of the Dutch discovery of Australia.

Permanent European settlers arrived at Sydney in 1788 and came to control most of the continent by end of the 19th century. Bastions of largely unaltered Aboriginal societies survived, particularly in Northern and Western Australia into the 20th century, until finally, a group of Pintupi

people of the Gibson Desert

became the last people to be contacted by outsider ways in 1984. While much knowledge was lost, Aboriginal art, music and culture, often scorned by Europeans during the initial phases of contact, survived and in time came to be celebrated by the wider Australian community.

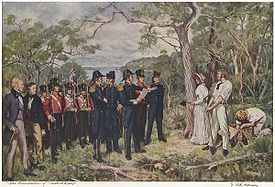

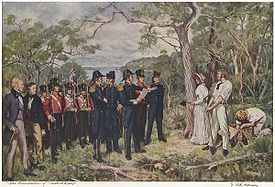

claimed the east coast of Australia for Britain in 1770, without conducting negotiations with the existing inhabitants. The first governor, Arthur Phillip

, was instructed explicitly to establish friendship and good relations with the Aborigines and interactions between the early newcomers and the ancient landowners varied considerably throughout the colonial period—from the mutual curiosity displayed by the early interlocutors Bennelong

and Bungaree

of Sydney, to the outright hostility of Pemulwuy

and Windradyne

of the Sydney region, and Yagan

around Perth. Bennelong and a companion became the first Australians to sail to Europe, where they met King George III. Bungaree accompanied the explorer Matthew Flinders

on the first circumnavigation of Australia. Pemulwuy was accused of the first killing of a white settler in 1790, and Windradyne resisted early British expansion beyond the Blue Mountains.

According to the historian Geoffrey Blainey

, in Australia during the colonial period: "In a thousand isolated places there were occasional shootings and spearings. Even worse, smallpox, measles, influenza and other new diseases swept from one Aboriginal camp to another ... The main conqueror of Aborigines was to be disease and its ally, demoralisation".

Even before the arrival of European settlers in local districts, European disease often preceded them. A smallpox epidemic was recorded in Sydney in 1789, which wiped out about half the Aborigines around Sydney." It then spread well beyond the then limits of European settlement, including much of southeastern Australia, reappearing in 1829–30, killing 40–60 percent of the Aboriginal population.

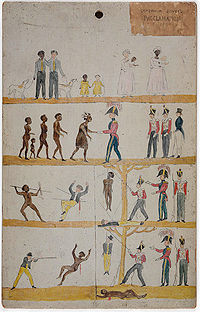

The impact of Europeans was profoundly disruptive to Aboriginal life and, though the extent of violence is debated, there was considerable conflict on the frontier. At the same time, some settlers were quite aware they were usurping the Aborigines place in Australia. In 1845, settler Charles Griffiths sought to justify this, writing; "The question comes to this; which has the better right – the savage, born in a country, which he runs over but can scarcely be said to occupy ... or the civilized man, who comes to introduce into this ... unproductive country, the industry which supports life."

From the 1960s, Australian writers began to re-assess European assumptions about Aboriginal Australia - with works including Alan Moorehead's

The Fatal Impact (1966) and Geoffrey Blainey's

landmark history Triumph of the Nomads (1975). In 1968, anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner

described the lack of historical accounts of relations between Europeans and Aborigines as "the great Australian silence." Historian Henry Reynolds

argues that there was a "historical neglect" of the Aborigines by historians until the late 1960s. Early commentaries often tended to describe Aborigines as doomed to extinction following the arrival of Europeans. William Westgarth’s 1864 book on the colony of Victoria observed; "the case of the Aborigines of Victoria confirms …it would seem almost an immutable law of nature that such inferior dark races should disappear." However, by the early 1970s historians like Lyndall Ryan, Henry Reynolds and Raymond Evans were trying to document and estimate the conflict and human toll on the frontier.

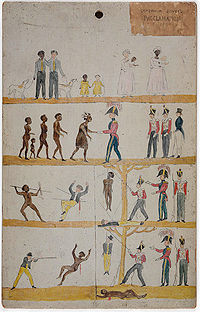

Many events illustrate violence and resistance as Aborigines sought to protect their lands from invasion and as settlers and pastoralists attempted to establish their presence. In May 1804, at Risdon Cove, Van Diemen's Land

Many events illustrate violence and resistance as Aborigines sought to protect their lands from invasion and as settlers and pastoralists attempted to establish their presence. In May 1804, at Risdon Cove, Van Diemen's Land

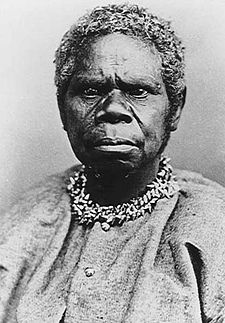

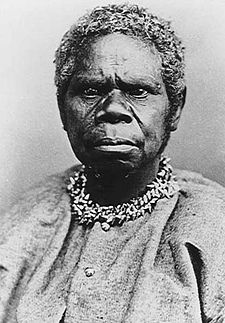

, perhaps 60 Aborigines were killed when they approached the town. The British established a new outpost in Van Diemen's Land

(Tasmania) in 1803. Although Tasmanian history is amongst the most contested by modern historians, conflict between colonists and Aborigines was referred to in some contemporary accounts as the Black War

. The combined effects of disease, dispossession, intermarriage and conflict saw a collapse of the Aboriginal population from a few thousand people when the British arrived, to a few hundred by the 1830s. Estimates of how many people were killed during the period begin at around 300, though verification of the true figure is now impossible. In 1830 Governor George Arthur

sent an armed party (the Black Line

) to push the Big River and Oyster Bay tribes out of the British settled districts. The effort failed and George Augustus Robinson

proposed to set out unarmed to mediate with the remaining tribespeople in 1833. With the assistance of Truganini

as guide and translator, Robinson convinced remaining tribesmen to surrender to an isolated new settlement at Flinders Island

, where most later died of disease.

In 1838, at least twenty-eight Aborigines were murdered at the Myall Creek

in New South Wales, resulting in the unprecedented conviction and hanging of seven white settlers by the colonial courts. Aborigines also attacked white settlers - in 1838 fourteen Europeans were killed at Broken River in Port Phillip District, by Aborigines of the Ovens River, almost certainly in revenge for the illicit use of Aboriginal women. Captain Hutton of Port Phillip District once told Chief Protector of Aborigines George Augustus Robinson

that "if a member of a tribe offend, destroy the whole." Queensland’s Colonial Secretary A.H. Palmer wrote in 1884 "the nature of the blacks was so treacherous that they were only guided by fear – in fact it was only possible to rule…the Australian Aboriginal…by brute force" The most recent massacre of Aborigines was at Coniston

in the Northern Territory in 1928. There are numerous other massacre sites in Australia, although supporting documentation varies.

From the 1830s, colonial governments established the now controversial offices of the Protector of Aborigines

in an effort to avoid mistreatment of Indigenous peoples and conduct government policy towards them. Christian churches in Australia

sought to convert Aborigines, and were often used by government to carry out welfare and assimilation policies. Colonial churchmen such as Sydney's first Catholic archbishop, John Bede Polding strongly advocated for Aboriginal rights and dignity and prominent Aboriginal activist Noel Pearson (born 1965), who was raised at a Lutheran mission in Cape York

, has written that Christian missions throughout Australia's colonial history "provided a haven from the hell of life on the Australian frontier while at the same time facilitating colonisation".

The Caledon Bay crisis

The Caledon Bay crisis

of 1932-4 saw one of the last incidents of violent interaction on the 'frontier' of indigenous and non-indigenous Australia, which began when the spearing of Japanese poachers who had been molesting Yolngu

women was followed by the killing of a policeman. As the crisis unfolded, national opinion swung behind the Aboriginal people involved, and the first appeal on behalf of an Indigenous Australian to the High Court of Australia

was launched. Following the crisis, the anthropologist Donald Thompson

was dispatched by the government to live among the Yolngu. Elsewhere around this time, activists like Sir Douglas Nicholls

were commencing their campaigns for Aboriginal rights within the established Australian political system and the age of frontier conflict closed.

Frontier encounters in Australia were not universally negative. Positive accounts of Aboriginal customs and encounters are also recorded in the journals of early European explorers, who often relied on Aboriginal guides and assistance: Charles Sturt

employed Aboriginal envoys to explore the Murray-Darling; the lone survivor of the Burke and Wills expedition was nursed by local Aborigines, and the famous Aboriginal explorer Jackey Jackey

loyally accompanied his ill-fated friend Edmund Kennedy

to Cape York

. Respectful studies were conducted by such as Walter Baldwin Spencer

and Frank Gillen in their renowned anthropological study The Native Tribes of Central Australia (1899); and by Donald Thompson

of Arnhem Land

(c.1935-1943). In inland Australia, the skills of Aboriginal stockmen became highly regarded and in the 20th century, Aboriginal stockmen like Vincent Lingiari

became national figures in their campagins for better pay and conditions.

The removal of indigenous children

, which the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission

argue constituted attempted genocide, had a major impact on the Indigenous population. Such interpretations of Aboriginal history are disputed by Keith Windschuttle

as being exaggerated or fabricated for political or ideological reasons. This debate is part of what is known within Australia as the History Wars

.

Several writers have tried to prove that Europeans visited Australia during the 16th century. Kenneth McIntyre

Several writers have tried to prove that Europeans visited Australia during the 16th century. Kenneth McIntyre

and others have argued that the Portuguese had secretly discovered Australia

in the 1520s. The presence of a landmass labelled "Jave la Grande

" on the Dieppe Maps

is often cited as evidence for a "Portuguese discovery". However, the Dieppe Maps also openly reflected the incomplete state of geographical knowledge at the time, both actual and theoretical. And it has been argued that Jave la Grande was a hypothetical notion, reflecting 16th century notions of cosmography

. Although theories of visits by Europeans, prior to the 17th century, continue to attract popular interest in Australia and elsewhere, they are generally regarded as contentious and lacking substantial evidence.

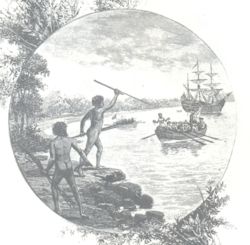

It is however, the crew of a Dutch ship, led by Willem Janszoon

, which is credited with the first authenticated European landing in Australia in 1606. That same year, a Spanish expedition sailing in nearby waters and led by Pedro Fernandez de Quiros had landed in the New Hebrides

and, believing them to be the fabled southern continent, named the land: Austrialis del Espiritu Santo Southern Land of the Holy Spirit. Later that year, De Quiros' deputy Luís Vaz de Torres

sailed through Australia's Torres Strait

and may have sighted Australia's northern coast.

In 1616, Dutch sea-captain Dirk Hartog

sailed too far whilst trying out Henderik Brouwer's recently discovered route from the Cape of Good Hope to Batavia, via the Roaring Forties. Reaching the western coast of Australia, he landed at Cape Inscription in Shark Bay on 25 October 1616. His is the first known record of a European visiting Western Australia's shores.

Although Abel Tasman

is best known for his voyage of 1642; in which he became the first known European to reach the islands of Van Diemen's Land

(later Tasmania

) and New Zealand

, and to sight the Fiji islands

, he also contributed significantly to the mapping of Australia proper. With three ships on his second voyage (Limmen, Zeemeeuw and the tender Braek) in 1644, he followed the south coast of New Guinea westward. He missed the Torres Strait

between New Guinea and Australia, but continued his voyage along the Australian coast and ended up mapping the north coast of Australia making observations on the land and its people.

By the 1650s, as a result of the Dutch discoveries, most of the Australian coast was charted reliably enough for the navigational standards of the day, and this was revealed for all to see in the map of the world inlaid into the floor of the Burgerzaal ("Burger's Hall") of the new Amsterdam Stadhuis ("Town Hall") in 1655. In 1664 the French geographer, Melchisedech Thévenot, published in Relations de Divers Voyages Curieux a map of New Holland drawn from the world map on the pavement of the Amsterdam Town Hall. Thévenot divided the continent in two, between Nova Hollandia to the west and Terre Australe to the east of a latitude staff running down the meridian equivalent to longitude 135 degrees East of Greenwich. Emanuel Bowen reproduced Thevenot's map in his Complete System of Geography (London, 1747), re-titling it A Complete Map of the Southern Continent and adding three inscriptions promoting the benefits of exploring and colonizing the country. One inscription said: "It is impossible to conceive a Country that promises fairer from its Situation than this of TERRA AUSTRALIS, no longer incognita, as this Map demonstrates, but the Southern Continent Discovered. It lies precisely in the richest climates of the World... and therefore whoever perfectly discovers and settles it will become infalliably possessed of Territories as Rich, as fruitful, and as capable of Improvement, as any that have hitherto been found out, either in the East Indies or the West." Bowen’s map was re-published in John Campbell’s editions of John Harris's Navigantium atque Itinerantium Bibliotheca, or Voyages and Travels (1744-1748, and 1764). This book also recommended a voyage be undertaken to explore the east coast of New Holland, with a view to a British colonization of the country: “The first Point, with respect to a Discovery, would be, to send a small Squadron on the Coast of Van Diemen's Land, and from thence round, in the same course taken by Captain Tasman, by the Coast of New Guiney; which might enable the Nations that attempted it, to come to an absolute Certainty with regard to its Commodities and Commerce... By this means all the back Coast of New Holland, and New Guiney, might be roughly examined; and we might know as well, and as certainly, as the Dutch, how far a Colony settled there might answer our Expectations.

Although various proposals for colonisation were made, notably by Pierre Purry from 1717 to 1744, none was officially attempted. Indigenous Australians

were less able to trade with Europeans than were the peoples of India, the East Indies

, China, and Japan. The Dutch East India Company

concluded that there was "no good to be done there". They turned down Purry’s scheme with the comment that, "There is no prospect of use or benefit to the Company in it, but rather very certain and heavy costs".

With the exception of further Dutch visits to the west, however, Australia remained largely unvisited by Europeans until the first British

explorations. John Callander put forward a proposal in 1766 for Britain to found a colony of banished convicts in the South Sea or in Terra Australis

to enable the mother country to exploit the riches of those regions. He said: "this world must present us with many things entirely new, as hitherto we have had little more knowledge of it, than if it had lain in another planet". In 1769, Lieutenant James Cook

in command of the HMS Endeavour

, traveled to Tahiti

to observe and record the transit of Venus

. Cook also carried secret Admiralty instructions to locate the supposed Southern Continent: "There is reason to imagine that a continent, or land of great extent, may be found to the southward of the track of former navigators." This continent was not found, as it only existed in the form of the yet to be discovered Antarctica, a much shrunken version of the Terra Australis

imagined by Alexander Dalrymple

and his fellow members of the Royal Society who had urged the Admiralty to undertake this mission. To save something useful from the expedition, Cook decided to survey the east coast of New Holland, the only major part of that continent that had not been charted in some form by Dutch navigators. On 19 April 1770, the crew of the Endeavour sighted the east coast of Australia and ten days later landed at Botany Bay

. Cook charted the east coast to its northern extent and, along with the ship's naturalist, Joseph Banks

, reported favourably on the possibilities of establishing a colony at Botany Bay. Cook formally took possession of the east coast of New Holland on 21/22 August 1770, and noted in his journal that he could, "land no more upon this Eastern coast of New Holland, and on the Western side I can make no new discovery the honour of which belongs to the Dutch Navigators and as such they may lay Claim to it as their property [italicised words crossed out in the original] but the Eastern Coast from the Latitude of 38 South down to this place I am confident was never seen or viseted by any European before us and therefore by the same Rule belongs to great Brittan [italicised words crossed out in the original]. Cook was careful therefore to take possession only of that part of the coastline not previously visited by Dutch navigators, i.e. from latitude 38ºS, Point Hicks, north of Van Diemens Land, to Cape York, East of Carpentaria.

In 1772, a French

expedition led by Louis Aleno de St Aloüarn

, became the first Europeans to formally claim sovereignty over the west coast of Australia

, but no attempt was made to follow this with colonisation.

The ambition of Sweden’s King Gustav III

to establish a colony for his country at the Swan River in 1786 remained stillborn. It was not until 1788 that economic, technological and political conditions in Great Britain made it possible and worthwhile for that country to make the large effort of sending the First Fleet

to New South Wales.

Seventeen years after Cook's landfall on the east coast of Australia, the British government decided to establish a colony at Botany Bay

Seventeen years after Cook's landfall on the east coast of Australia, the British government decided to establish a colony at Botany Bay

.

The American Revolutionary War

of (1775–1783) saw Britain lose most of its North American colonies and consider establishing replacement territories. In 1779 Sir Joseph Banks, the eminent scientist who had accompanied James Cook

on his 1770 voyage, recommended Botany Bay

as a suitable site for settlement. Under Banks’s guidance, the American Loyalist

James Matra, who had also travelled with Cook, produced "A Proposal for Establishing a Settlement in New South Wales" (23 August 1783), proposing the establishment of a colony composed of American Loyalists, Chinese and South Sea Islanders (but not convicts).

Matra reasoned that: the country was suitable for plantations of sugar, cotton and tobacco; New Zealand timber and hemp or flax could prove valuable commodities; it could form a base for Pacific trade; and it could be a suitable compensation for displaced American Loyalists. Following an interview with Secretary of State Lord Sydney in 1784, Matra amended his proposal to include convicts as settlers, considering that this would benefit both "Economy to the Publick, & Humanity to the Individual".

Matra’s plan provided the original blueprint for settlement.

Records show the government was considering it in 1784. The London newspapers announced in November 1784 that: “A plan has been presented to the [Prime] Minister, and is now before the Cabinet, for instituting a new colony in New Holland. In this vast tract of land….every sort of produce and improvement of which the various soils of the earth are capable, may be expected”. The Government also incorporated the settlement of Norfolk Island

into their plan, with its attractions of timber and flax, proposed by Banks’s Royal Society colleagues, Sir John Call and Sir George Young.

At the same time, humanitarians and reformers were campaigning in Britain against the appalling conditions in British prisons and hulks. In 1777 prison reformer John Howard wrote The State of Prisons in England and Wales, exposing the harsh conditions of the prison system to "genteel society"." Penal transportation

was already well established as a central plank of English criminal law and until the American Revolution

about a thousand criminals per year were sent to Maryland and Virginia. It served as a powerful deterrent to law-breaking. According to historian David Hill, "Europeans knew little about the geography of the globe" and to "convicts in England, transportation to Botany Bay

was a frightening prospect." Echoing John Callander, he said Australia "might as well have been another planet."

In 1933, Sir Ernest Scott, stated the traditional view of the reasons for colonisation: “It is clear that the only consideration which weighed seriously with the Pitt Government was the immediately pressing and practical one of finding a suitable place for a convict settlement ”. In the early 1960s, historian Geoffrey Blainey

questioned the traditional view of foundation purely as a convict dumping ground. His book The Tyranny of Distance suggested ensuring supplies of flax and timber after the loss of the American colonies may have also been motivations, and Norfolk Island

was the key to the British decision. A number of historians responded and debate brought to light a large amount of additional source material on the reasons for settlement.

The decision to settle was taken when it seemed the outbreak of civil war in the Netherlands might precipitate a war in which Britain would be again confronted with the alliance of the three naval Powers, France, Holland and Spain, which had brought her to defeat in 1783. Under these circumstances, the strategic advantages of a colony in New South Wales described in James Matra's proposal were attractive. Matra wrote that such a settlement could facilitate attacks upon the Spanish in South America and the Philippines, and against the Dutch East Indies

. In 1790, during the Nootka Crisis

, plans were made for naval expeditions against Spain’s possessions in the Americas and the Philippines, in which New South Wales was assigned the role of a base for “refreshment, communication and retreat”. On subsequent occasions into the early 19th century when war threatened or broke out between Britain and Spain, these plans were revived and only the short length of the period of hostilities in each case prevented them from being put into effect.

The German scientist and man of letters Georg Forster

, who had sailed under Captain James Cook in the voyage of the Resolution (1772–1775), wrote in 1786 on the future prospects of the English colony: "New Holland, an island of enormous extent or it might be said, a third continent, is the future homeland of a new civilized society which, however mean its beginning may seem to be, nevertheless promises within a short time to become very important." And the merchant adventurer and would-be colonizer of southwestern Australia under the Swedish flag, William Bolts, said to the Swedish Ambassador in Paris, Erik von Staël in December 1789, that the British had founded at Botany Bay, “a settlement which in time will become of the greatest importance to the Commerce of the Globe”.

The territory claimed by Britain included all of Australia eastward of the meridian of 135° East and all the islands in the Pacific Ocean between the latitudes of Cape York

The territory claimed by Britain included all of Australia eastward of the meridian of 135° East and all the islands in the Pacific Ocean between the latitudes of Cape York

and the southern tip of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania). The western limit of 135° East was set at the meridian dividing New Holland from Terra Australis shown on Emanuel Bowen's Complete Map of the Southern Continent, published in John Campbell’s editions of John Harris's Navigantium atque Itinerantium Bibliotheca, or Voyages and Travels (1744-1748, and 1764). It was a vast claim which elicited excitement at the time: the Dutch translator of First Fleet officer and author Watkin Tench

's A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay wrote: "a single province which, beyond all doubt, is the largest on the whole surface of the earth. From their definition it covers, in its greatest extent from East to West, virtually a fourth of the whole circumference of the Globe". Spanish naval commander Alessandro Malaspina

, who visited Sydney in March–April 1793 reported to his government that: “The transportation of the convicts constituted the means and not the object of the enterprise. The extension of dominion, mercantile speculations and the discovery of mines were the real object”. Frenchman François Péron

, of the Baudin expedition

visited Sydney in 1802 and reported to the French Government: “How can it be conceived that such a monstrous invasion was accomplished, with no complaint in Europe to protest against it? How can it be conceived that Spain, who had previously raised so many objections opposing the occupation of the Malouines (Falklands Islands), meekly allowed a formidable empire to arise to facing her richest possessions, an empire which must either invade or liberate them?

The colony included the current islands of New Zealand

. In 1817, the British government withdrew the extensive territorial claim over the South Pacific. In practice, the governors' writ had been shown not to run in the islands of the South Pacific. The Church Missionary Society had concerns over atrocities committed against the natives of the South Sea Islands, and the ineffectiveness of the New South Wales government to deal with the lawlessness. As a result, on 27 June 1817, Parliament passed an Act for the more effectual Punishment of Murders and Manslaughters committed in Places not within His Majesty's Dominions, which described Tahiti, New Zealand and other islands of the South Pacific as being not within His Majesty's dominions.

of 11 vessels under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip

in January 1788. It consisted of over a thousand settlers, including 778 convicts (192 women and 586 men). A few days after arrival at Botany Bay

the fleet moved to the more suitable Port Jackson

where a settlement was established at Sydney Cove

on 26 January 1788. This date later became Australia's national day, Australia Day

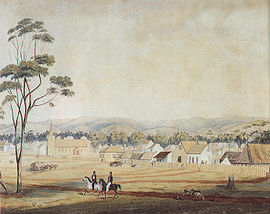

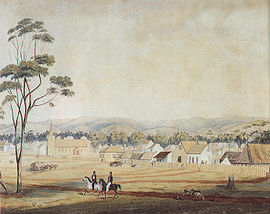

. The colony was formally proclaimed by Governor Phillip on 7 February 1788 at Sydney.

Sydney Cove offered a fresh water supply and a safe harbour, which Philip described as:

Governor Phillip was vested with complete authority over the inhabitants of the colony. Enlightened for his Age, Phillip's personal intent was to establish harmonious relations with local Aboriginal people and try to reform as well as discipline the convicts of the colony. Phillip and several of his officers - most notably Watkin Tench

- left behind journals and accounts of which tell of immense hardships during the first years of settlement. Often Phillip's officers despaired for the future of New South Wales. Early efforts at agriculture were fraught and supplies from overseas were scarce. Between 1788 and 1792 about 3546 male and 766 female convicts were landed at Sydney - many "professional criminals" with few of the skills required for the establishment of a colony. Many new arrivals were also sick or unfit for work and the conditions of healthy convicts only deteriorated with hard labour and poor sustenance in the settlement. The food situation reached crisis point in 1790 and the Second Fleet which finally arrived in June 1790 had lost a quarter of its 'passengers' through sickness, while the condition of the convicts of the Third Fleet appalled Phillip. from 1791 however, the more regular arrival of ships and the beginnings of trade lessened the feeling of isolation and improved supplies.

Phillip sent exploratory missions in search of better soils, fixed on the Parramatta region as a promising area for expansion, and moved many of the convicts from late 1788 to establish a small township, which became the main centre of the colony's economic life. This left Sydney Cove only as an important port and focus of social life. Poor equipment and unfamiliar soils and climate continued to hamper the expansion of farming from Farm Cove to Parramatta and Toongabbie, but a building programme, assisted by convict labour, advanced steadily. Between 1788-92, convicts and their gaolers made up the majority of the population - but after this, a population of emancipated convicts began to grow who could be granted land and these people pioneered a non-government private sector economy and were later joined by soldiers whose military service had expired - and finally, free settlers who began arriving from Britain. Governor Phillip departed the colony for England on 11 December 1792, with the new settlement having survived near starvation and immense isolation for four years

of the colonial government in Sydney, and a western half named New Holland

. The western boundary of 135° East of Greenwich was based on the Complete Map of the Southern Continent, published in Emanuel Bowen’s Complete System of Geography (London 1747), and reproduced in John Campbell’s editions of John Harris's Navigantium atque Itinerantium Bibliotheca, or Voyages and Travels (1744-48, and 1764). Bowen’s map was based on one by Melchisedec Thevenot and published in Relations des Divers Voyages (1663), which divided New Holland in the west from Terra Australis in the east by a latitude staff situated at 135° East. This division reproduced in Bowen’s map, provided a convenient western boundary for the British claim because, as Watkin Tench subsequently commented in A Narrative of the Expedition to Botany Bay, “By this partition, it may be fairly presumed, that every source of future litigation between the Dutch and us, will be for ever cut off, as the discoveries of English navigators only are comprized in this territory”. Thevenot said he copied his map from the one engraved in the floor of the Amsterdam Town Hall, but in that map there was no dividing line between New Holland and Terra Australis. Longitude 135° East reflected the line of division between the claims of Spain and Portugal established in the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494, which had formed the basis of many subsequent claims to colonial territory. An Historical Narrative of the Discovery of New Holland and New South Wales, published in November 1786, contained "A General Chart of New Holland, including New South Wales & Botany Bay, with The Adjacent Countries, and New Discovered Islands", which showed all the territory claimed under the jurisdiction of the Governor of New South Wales.

Romantic descriptions of the beauty, mild climate, and fertile soil of Norfolk Island

in the South Pacific led the British government to establish a subsidiary settlement of the New South Wales colony there in 1788. It was hoped that the giant Norfolk Island pine trees and flax plants growing wild on the island might provide the basis for a local industry which, particularly in the case of flax, would provide an alternative source of supply to Russia for an article which was essential for making cordage and sails for the ships of the British navy. However, the island had no safe harbor, which led the colony to be abandoned and the settlers evacuated to Tasmania in 1807. The island was subsequently re-settled as a penal settlement in 1824.

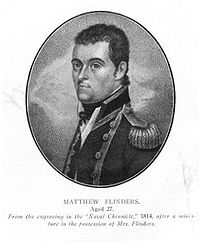

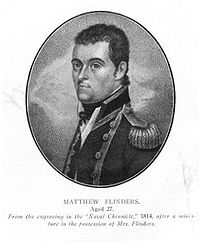

In 1798, George Bass

and Matthew Flinders

circumnavigated Van Diemen's Land, proving that it was an island. In 1802, Flinders successfully circumnavigated Australia for the first time.

Van Diemen's Land

, now known as Tasmania

, was settled in 1803, following a failed attempt to settle at Sullivan Bay

in what is now Victoria. Other British settlements followed, at various points around the continent, many of them unsuccessful. The East India Trade Committee recommended in 1823 that a settlement be established on the coast of northern Australia to forestall the Dutch, and Captain J.J.G.Bremer, RN, was commissioned to form a settlement between Bathurst Island and the Cobourg Peninsula

. Bremer fixed the site of his settlement at Fort Dundas

on Melville Island in 1824 and, because this was well to the west of the boundary proclaimed in 1788, proclaimed British sovereignty over all the territory as far west as Longitude 129˚ East.

The new boundary included Melville and Bathurst Islands, and the adjacent mainland. In 1826, the British claim was extended to the whole Australian continent when Major Edmund Lockyer

established a settlement on King George Sound

(the basis of the later town of Albany

), but the eastern border of Western Australia

remained unchanged at Longitude 129˚ East. In 1824, a penal colony was established near the mouth of the Brisbane River

(the basis of the later colony of Queensland

). In 1829, the Swan River Colony

and its capital of Perth

were founded on the west coast proper and also assumed control of King George Sound. Initially a free colony, Western Australia later accepted British convicts, because of an acute labour shortage.

Between 1788 and 1868, approximately 161,700 convicts (of whom 25,000 were women) were transported to the Australian colonies of New South Wales, Van Diemen’s land and Western Australia. Historian Lloyd Robson has estimated that perhaps two thirds were thieves from working class towns, particularly from the midlands and north of England. The majority were repeat offenders. Whether transportation managed to achieve its goal of reforming or not, some convicts were able to leave the prison system in Australia; after 1801 they could gain "tickets of leave" for good behaviour and be assigned to work for free men for wages. A few went on to have successful lives as emancipists, having been pardoned at the end of their sentence. Female convicts had fewer opportunities.

Between 1788 and 1868, approximately 161,700 convicts (of whom 25,000 were women) were transported to the Australian colonies of New South Wales, Van Diemen’s land and Western Australia. Historian Lloyd Robson has estimated that perhaps two thirds were thieves from working class towns, particularly from the midlands and north of England. The majority were repeat offenders. Whether transportation managed to achieve its goal of reforming or not, some convicts were able to leave the prison system in Australia; after 1801 they could gain "tickets of leave" for good behaviour and be assigned to work for free men for wages. A few went on to have successful lives as emancipists, having been pardoned at the end of their sentence. Female convicts had fewer opportunities.

Some convicts, particularly Irish convicts, had been transported to Australia for political crimes or social rebellion, so authorities were consequently suspicious of the Irish and restricted the practice of Catholicism in Australia. The Irish led Castle Hill Rebellion of 1804 served to increase suspicions and repression. Church of England

Some convicts, particularly Irish convicts, had been transported to Australia for political crimes or social rebellion, so authorities were consequently suspicious of the Irish and restricted the practice of Catholicism in Australia. The Irish led Castle Hill Rebellion of 1804 served to increase suspicions and repression. Church of England

clergy meanwhile worked closely with the governors

and Richard Johnson

, chaplain to the First Fleet

was charged by Governor Arthur Phillip

, with improving "public morality" in the colony and was also heavily involved in health and education. The Reverend Samuel Marsden

(1765–1838) had magisterial

duties, and so was equated with the authorities by the convicts, becoming known as the 'flogging parson' for the severity of his punishments

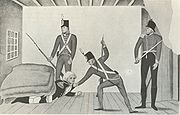

The New South Wales Corps

was formed in England in 1789 as a permanent regiment to relieve the marines who had accompanied the First Fleet

. Officers of the Corps soon became involved in the corrupt and lucrative rum trade in the colony. In the Rum Rebellion

of 1808, the Corps, working closely with the newly established wool trader John Macarthur

, staged the only successful armed takeover of government in Australian history, deposing Governor

William Bligh

and instigating a brief period of military rule in the colony prior to the arrival from Britain of Governor Lachlan Macquarie

in 1810.

Macquarie served as the last autocratic Governor of New South Wales, from 1810 to 1821 and had a leading role in the social and economic development of New South Wales which saw it transition from a penal colony

to a budding free society. He established public works, a bank

, churches, and charitable institutions and sought good relations with the Aborigines. In 1813 he sent Blaxland

, Wentworth

and Lawson across the Blue Mountains, where they found the great plains of the interior. Central, however to Macquarie's policy was his treatment of the emancipist

s, whom he decreed should be treated as social equals to free-settlers in the colony. Against opposition, he appointed emancipists to key government positions including Francis Greenway

as colonial architect and William Redfern

as a magistrate. London judged his public works to be too expensive and society was scandalised by his treatment of emancipists. Egalitarianism

would come to be considered a central virtue among Australians.

The first five Governors of New South Wales realised the urgent need to encourage free settlers, but the British government remained largely indifferent. As early as 1790, Governor Arthur Phillip wrote; "Your lordship will see by my…letters the little progress we have been able to make in cultivating the lands ... At present this settlement only affords one person that I can employ in cultivating the lands..." It was not until the 1820s that numbers of free settlers began to arrive and government schemes began to be introduced to encourage free settlers. Philanthropists Caroline Chisholm

and John Dunmore Lang

developed their own migration schemes. Land grants of crown land were made by Governors, and settlement schemes such as those of Edward Gibbon Wakefield

carried some weight in encouraging migrants to make the long voyage to Australia, as opposed to the United States or Canada.

Early colonial administrations were anxious to address the gender imbalance in the population brought about by the importation of large numbers of convict men. Between 1788 and 1792, around 3546 male to 766 female convicts were landed at Sydney. Women came to play an important role in education and welfare during colonial times. Governor Macquarie's wife, Elizabeth Macquarie

took an interest in convict women's welfare. Her contemporary Elizabeth Macarthur

was noted for her 'feminine strength' in assisting the establishment of the Australian merino wool industry during her husband John Macarthur

's enforced absence from the colony following the Rum Rebellion

. The Catholic Sisters of Charity

arriving in 1838 and set about pastoral care in a women's prison, visiting hospitals and schools and establishing employment for convict women. The sisters went on to establish hospitals in four of the eastern states, beginning with St Vincent's Hospital, Sydney

in 1857 as a free hospital for all people, but especially for the poor. Caroline Chisholm

(1808–1877) established a migrant women's shelter and worked for women's welfare in the colonies in the 1840s. Her humanitarian efforts later won her fame in England and great influence in achieving support for families in the colony. Sydney's first Catholic Bishop, John Bede Polding founded an Australian order of nuns - the Sisters of the Good Samaritan

- in 1857 to work in education and social work. The Sisters of St Joseph

, were founded in South Australia by Saint Mary MacKillop and Fr Julian Tenison Woods

in 1867. MacKillop travelled throughout Australasia

and established schools, convents and charitable institutions. She was canonised by Benedict XVI in 2010, becoming the first Australian to be so honoured by the Catholic Church.

From the 1820s, increasing numbers of squatters

occupied land beyond the fringes of European settlement. Often running sheep on large stations

with relatively few overheads, squatters could make considerable profits. By 1834, nearly 2 million kilograms of wool were being exported to Britain from Australia. By 1850, barely 2,000 squatters had gained 30 million hectares of land, and they formed a powerful and "respectable" interest group in several colonies.

In 1835, the British Colonial Office

issued the Proclamation of Governor Bourke

, implementing the legal doctrine of terra nullius

upon which British settlement was based, reinforcing the notion that the land belonged to no one prior to the British Crown taking possession of it and quashing any likelihood of treaties with Aboriginal peoples, including that signed by John Batman

. Its publication meant that from then, all people found occupying land without the authority of the government would be considered illegal trespassers.

Separate settlements and later, colonies, were created from parts of New South Wales: South Australia

in 1836, New Zealand

in 1840, Port Phillip District

in 1834, later becoming the colony of Victoria

in 1851, and Queensland

in 1859. The Northern Territory

was founded in 1863 as part of South Australia. The transportation of convicts to Australia was phased out between 1840 and 1868.

Massive areas of land were cleared for agriculture and various other purposes in the first 100 years of Europeans settlement. In addition to the obvious impacts this early clearing of land and importation of hard-hoofed animals had on the ecology of particular regions, it severely affected indigenous Australians, by reducing the resources they relied on for food, shelter and other essentials. This progressively forced them into smaller areas and reduced their numbers as the majority died of newly introduced diseases and lack of resources. Indigenous resistance

against the settlers was widespread, and prolonged fighting between 1788 and the 1920s led to the deaths of at least 20,000 Indigenous people and between 2,000 and 2,500 Europeans. During the mid-late 19th century, many indigenous Australians in south eastern Australia were relocated, often forcibly, to reserves and missions. The nature of many of these institutions enabled disease to spread quickly and many were closed as their populations fell.

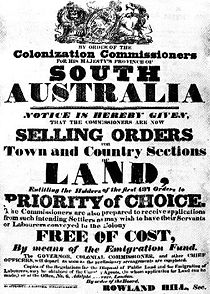

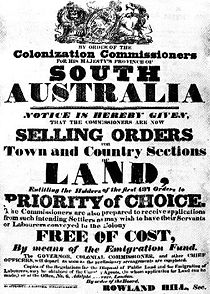

A group in Britain led by Edward Gibbon Wakefield

A group in Britain led by Edward Gibbon Wakefield

sought to start a colony based on free settlement rather than convict labour. In 1831 the South Australian Land Company was formed amid a campaign for a Royal Charter which would provide for the establishment of a privately financed "free" colony in Australia.

While New South Wales, Tasmania and (although not initially) Western Australia were established as convict settlements, the founders of South Australia had a vision of a colony with political and religious freedoms, together with opportunities for wealth through business and pastoral investments. The South Australia Act [1834], passed by the British Government which established the colony reflected these desires and included a promise of representative government when the population reached 50,000 people. South Australia thus became the only colony authorised by an Act of Parliament

, and which was intended to be developed at no cost to the British government. Transportation of convicts was forbidden, and 'poor Emigrants', assisted by an Emigration Fund, were required to bring their families with them. Significantly, the Letters Patent

enabling the South Australia Act 1834 included a guarantee of the rights of 'any Aboriginal Natives' and their descendants to lands they 'now actually occupied or enjoyed'.

In 1836, two ships of the South Australia Land Company left to establish the first settlement on Kangaroo Island

. The foundation of South Australia is now generally commemorated as Governor John Hindmarsh

's Proclamation of the new Province at Glenelg, on the mainland, on 28 December 1836. From 1843-1851, the Governor ruled with the assistance of an appointed Executive Council of paid officials. Land development and settlement was the basis of the Wakefield vision, so land law and regulations governing it were fundamental to the foundation of the Province and allowed for land to be be bought at a uniform price per acre (regardless of quality), with auctions for land desired by more than one buyer, and leases made available on unused land. Proceeds from land were to fund the Emigration Fund to assist poor settlers to come as tradesmen and labourers. Agitation for representative government quickly emerged. Most other colonies had been founded by Governors with near total authority, but in South Australia, power was initially divided between the Governor and the Resident Commissioner, so that government could not interfere with the business affairs or freedom of religion of the settlers. By 1851 the colony was experimenting with a partially elected council.

In 1798-9 George Bass

In 1798-9 George Bass

and Matthew Flinders

set out from Sydney in a sloop and circumnavigated Tasmania

, thus proving it to be an island. In 1801-02 Matthew Flinders in The Investigator lead the first circumnavigation of Australia. Aboard ship was the Aboriginal explorer Bungaree

, of the Sydney district, who became the first person born on the Australian continent to circumnavigate the Australian continent. Previously, the famous Bennelong

and a companion had become the first people born in the area of New South Wales to sail for Europe, when, in 1792 they accompanied Governor Phillip to England and were presented to King George III.

In 1813, Gregory Blaxland

, William Lawson and William Wentworth

succeeded in crossing the formidable barrier of forested gulleys and shere cliffs presented by the Blue Mountains, west of Sydney. At Mount Blaxland they looked out over "enough grass to support the stock of the colony for thirty years", and expansion of the British settlement into the interior could begin.

In 1824 the Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane

, commissioned Hamilton Hume

and former Royal Navy Captain William Hovell

to lead an expedition to find new grazing land in the south of the colony, and also to find an answer to the mystery of where New South Wales's western rivers flowed. Over 16 weeks in 1824-25, Hume and Hovell

journeyed to Port Phillip and back. They made many important discoveries including the Murray River

(which they named the Hume), many of its tributaries, and good agricultural and grazing lands between Gunning, New South Wales

and Corio Bay, Victoria.

Charles Sturt

led an expedition along the Macquarie River

in 1828 and discovered the Darling River

. A theory had developed that the inland rivers of New South Wales were draining into an inland sea. Leading a second expedition in 1829, Sturt followed the Murrumbidgee River

into a 'broad and noble river', the Murray River, which he named after Sir George Murray, secretary of state for the colonies. His party then followed this river to its junction with the Darling River

, facing two threatening encounters with local Aboriginal people along the way. Sturt continued down river on to Lake Alexandrina, where the Murray meets the sea in South Australia

. Suffering greatly, the party had to row hundreds of kilometres back upstream for the return journey.

Surveyor General Sir Thomas Mitchell conducted a series of expeditions from the 1830s to 'fill in the gaps' left by these previous expeditions. He was meticulous in seeking to record the original Aboriginal place names around the colony, for which reason the majority of place names to this day retain their Aboriginal titles.

The Polish scientist/explorer Count Paul Edmund Strzelecki conducted surveying work in the Australian Alps

in 1839 and became the first European to ascend Australia's highest peak, which he named Mount Kosciuszko

in honour of the Polish patriot Tadeusz Kosciuszko

.

European explorers made their last great, often arduous and sometimes tragic expeditions into the interior of Australia during the second half of the 19th century - some with the official sponsorship of the colonial authorities and others commissioned by private investors. By 1850, large areas of the inland were still unknown to Europeans. Trailblazers like Edmund Kennedy

and the Prussian naturalist Ludwig Leichhardt

, had met tragic ends attempting to fill in the gaps during the 1840s, but explorers remained ambitious to discover new lands for agriculture or answer scientific enquiries. Surveyors also acted as explorers and the colonies sent out expeditions to discover the best routes for lines of communication. The size of expeditions varied considerably from small parties of just two or three to large, well equipped teams led by gentlemen explorers assisted by smiths, carpenters, labourers and Aboriginal guides accompanied by horses, camels or bullocks.

In 1860, the ill fated Burke and Wills led the first north-south crossing of the continent from Melbourne to the Gulf of Carpentaria

. Lacking bushcraft and unwilling to learn from the local Aboriginal people, Burke and Wills died in 1861, having returned from the Gulf to their rendezvous point at Coopers Creek only to discover the rest of their party had departed the location only a matter of hours previously. Though an impressive feat of navigation, the expedition was an organisational disaster which continues to fascinate the Australian public.

In 1862, John McDouall Stuart

succeeded in traversing Central Australia from south to north. His expedition mapped out the route which was later followed by the Australian Overland Telegraph Line

.

Uluru

and Kata Tjuta

were first mapped by Europeans in 1872 during the expeditionary period made possible by the construction of the Australian Overland Telegraph Line

. In separate expeditions, Ernest Giles

and William Gosse

were the first European explorers to this area. While exploring the area in 1872, Giles sighted Kata Tjuta from a location near Kings Canyon

and called it Mount Olga, while the following year Gosse observed Uluru and named it Ayers Rock, in honor of the Chief Secretary of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayers. These barren dessert lands of Central Australia disappointed the Europeans as unpromising for pastoral expansion, but would later come to be appreciated as emblematic of Australia.

in Australia is traditionally attributed to Edward Hammond Hargraves, near Bathurst, New South Wales

, in February 1851 Traces of gold had nevertheless been found in Australia as early as 1823 by surveyor James McBrien. As by English law

all minerals belonged to the Crown, there was at first, "little to stimulate a search for really rich goldfields in a colony prospering under a pastoral economy." Richard Broome also argues that the California Gold Rush

at first overawed the Australian finds, until "the news of Mount Alexander

reached England in May 1852, followed shortly by six ships carrying eight tons of gold."

The gold rushes brought many immigrants to Australia from Great Britain, Ireland, continental Europe, North America and China. The Colony of Victoria

The gold rushes brought many immigrants to Australia from Great Britain, Ireland, continental Europe, North America and China. The Colony of Victoria

’s population grew rapidly, from 76,000 in 1850 to 530,000 by 1859. Discontent arose amongst diggers

almost immediately, particularly on the crowded Victorian fields. The causes of this were the colonial government’s administration of the diggings and the gold licence system. Following a number of protests and petitions for reform

, violence erupted at Ballarat

in late 1854.

Early on the morning of Sunday 3 December 1854, British soldiers and Police attacked a stockade built on the Eureka lead

holding some of the aggrieved diggers. In a short fight, at least 30 miners were killed and an unknown number wounded. O’Brien lists 5 soldiers of the 12th Regiment

and 40 Regiment

killed and 12 wounded Blinded by his fear of agitation with democratic overtones, local Commissioner Robert Rede had felt "it was absolutely necessary that a blow should be struck" against the miners.

But a few months later, a Royal commission made sweeping changes to the administration of Victoria’s goldfields. Its recommendations included the abolition of the licence, reforms to the police force and voting rights for miners holding a Miner’s Right. The Eureka flag

that was used to represent the Ballarat miners has been seriously considered by some as an alternative to the Australian flag

, because of its association with democratic developments.

In the 1890s, visiting author Mark Twain

characterised the battle at Eureka

as:

Later gold rushes occurred at the Palmer River

, Queensland

, in the 1870s, and Coolgardie

and Kalgoorlie

in Western Australia, in the 1890s. Confrontations between Chinese and European miners occurred on the Buckland River in Victoria and Lambing Flat

in New South Wales, in the late 1850s and early 1860s. Driven by European jealousy of the success of Chinese efforts as alluvial (surface) gold ran out, it fixed emerging Australian attitudes in favour of a White Australia policy

, according to historian Geoffrey Serle

.

New South Wales in 1855 was the first colony to gain responsible government

, managing most of its own affairs while remaining part of the British Empire. Victoria, Tasmania, and South Australia followed in 1856; Queensland, from its foundation in 1859; and Western Australia, in 1890. The Colonial Office in London retained control of some matters, notably foreign affairs, defence and international shipping.

The gold era led to a long period of prosperity, sometimes called "the long boom." This was fed by British investment and the continued growth of the pastoral and mining industries, in addition to the growth of efficient transport by rail

, river

and sea. By 1891, the sheep population of Australia was estimated at 100 million. Gold production had declined since the 1850s, but in the same year was still worth £5.2 million. Eventually the economic expansion ended; the 1890s were a period of economic depression, felt most strongly in Victoria, and its capital Melbourne

.

The late 19th century had however, seen a great growth in the cities of south eastern Australia. Australia's population (not including Aborigines, who were excluded from census calculations) in 1900 was 3.7 million, almost 1 million of whom lived in Melbourne

and Sydney

. More than two thirds of the population overall lived in cities and towns by the close of the century, making "Australia one of the most urbanised societies in the western world."

Bushrangers, originally referred to runaway convicts in the early years of the British settlement of Australia

Bushrangers, originally referred to runaway convicts in the early years of the British settlement of Australia

who had the survival skills necessary to use the Australia

n bush

as a refuge to hide from the authorities. The term "bushranger" then evolved to refer to those who abandoned social rights and privileges to take up "robbery under arms" as a way of life, using the bush as their base. These bushrangers were roughly analogous to British "highwaymen

" and American "Old West outlaws," and their crimes often included robbing small-town banks or coach services.

More than 2000 bushrangers are believed to have roamed the Australian countryside, beginning with the convict bolters and ending after Ned Kelly

's last stand at Glenrowan.

Bold Jack Donahue

is recorded as the last convict bushranger. He was reported in newspapers around 1827 as being responsible for an outbreak of bushranging on the road between Sydney

and Windsor

. Throughout the 1830s he was regarded as the most notorious bushranger in the colony. Leading a band of escaped convicts, Donahue became central to Australian folklore as the Wild Colonial Boy.

Bushranging was common on the mainland, but Van Diemen's Land

(Tasmania

) produced the most violent and serious outbreaks of convict bushrangers. Hundreds of convicts were at large in the bush, farms were abandoned and martial law was proclaimed. Indigenous outlaw Musquito

defied colonial law and led attacks on settlers.

The bushrangers' heyday was the Gold Rush

years of the 1850s and 1860s.

There was much bushranging activity in the Lachlan Valley

, around Forbes

, Yass

and Cowra

in News South Wales. Frank Gardiner

, John Gilbert

and Ben Hall led the most notorious gangs of the period. Other active bushrangers included Dan Morgan

, based in the Murray River

, and Captain Thunderbolt

, killed outside Uralla.

The increasing push of settlement, increased police efficiency, improvements in rail transport

and communications technology, such as telegraphy

, made it increasingly difficult for bushrangers to evade capture.

Among the last bushrangers were the Kelly Gang, led by Ned Kelly

, who were captured at Glenrowan in 1880, two years after they were outlawed. Kelly was born in Victoria

to an Irish convict

father, and as a young man he clashed with the Victoria Police

. Following an incident at his home in 1878, police parties searched for him in the bush. After he killed three policemen, the colony proclaimed Kelly and his gang wanted outlaw

s.

A final violent confrontation with police took place at Glenrowan

on 28 June 1880. Kelly, dressed in home-made plate metal armour

and helmet, was captured and sent to jail. He was hanged for murder at Old Melbourne Gaol in November 1880. His daring and notoriety made him an iconic

figure in Australian history, folklore, literature, art and film.

Some bushrangers, most notably Ned Kelly in his Jerilderie Letter

, and in his final raid on Glenrowan, explicitly represented themselves as political rebels. Attitudes to Kelly, by far the most well-known bushranger, exemplify the ambivalent views of Australians regarding bushranging.

Traditional Aboriginal society had been governed by councils of elders and a corporate decision making process, but the first European-style governments established after 1788 were autocratic and run by appointed governors

Traditional Aboriginal society had been governed by councils of elders and a corporate decision making process, but the first European-style governments established after 1788 were autocratic and run by appointed governors

- although English law was transplanted into the Australian colonies by virtue of the doctrine of reception

, thus notions of the rights and processes established by the Magna Carta

and the Bill of Rights 1689

were brought from Britain by the colonists. Agitation for representative government began soon after the settlement of the colonies.

The oldest legislative body in Australia, the New South Wales Legislative Council

, was created in 1825 as an appointed body to advise the Governor of New South Wales. William Wentworth

established the Australian Patriotic Association (Australia's first political party) in 1835 to demand democratic government for New South Wales. The reformist attorney general, John Plunkett

, sought to apply Enlightenment

principles to governance in the colony, pursuing the establishment of equality before the law, first by extending jury rights to emancipist

s, then by extending legal protections to convicts, assigned servants and Aborigines

. Plunkett twice charged the colonist perpetrators of the Myall Creek massacre

of Aborigines with murder, resulting in a conviction and his landmark Church Act of 1836 disestablished

the Church of England

and established legal equality between Anglicans

, Catholics, Presbyterians and later Methodists.

In 1840, the Adelaide City Council and the Sydney City Council were established. Men who possessed 1000 pounds worth of property were able to stand for election and wealthy landowners were permitted up to four votes each in elections. Australia's first parliamentary elections were conducted for the New South Wales Legislative Council

in 1843, again with voting rights (for males only) tied to property ownership or financial capacity. Voter rights were extended further in New South Wales in 1850 and elections for legislative councils were held in the colonies of Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania.

By the mid 19th century, there was a strong desire for representative and responsible government in the colonies of Australia, fed by the democratic spirit of the goldfields

evident at the Eureka Stockade

and the ideas of the great reform movements sweeping Europe

, the United States

and the British Empire. The end of convict transportation accelerated reform in the 1840s and 1850s. The Australian Colonies Government Act [1850] was a landmark development which granted representative constitutions to New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania and the colonies enthusiastically set about writing constitutions which produced democratically progressive parliaments - though the constitutions generally maintained the role of the colonial upper houses as representative of social and economic "interests" and all established Constitutional Monarchies

with the British monarch as the symbolic head of state.

In 1855, limited self government was granted by London to New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. An innovative secret ballot

was introduced in Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia in 1856, in which the government supplied voting paper containing the names of candidates and voters could select in private. This system was adopted around the world, becoming known as the "Australian Ballot". 1855 also saw the granting of the right to vote to all male British subjects 21 years or over in South Australia

. This right was extended to Victoria in 1857 and New South Wales the following year. The other colonies followed until, in 1896, Tasmania became the last colony to grant universal male suffrage.

Propertied women in the colony of South Australia were granted the vote in local elections (but not parliamentary elections) in 1861. Henrietta Dugdale

formed the first Australian women's suffrage society in Melbourne

, Victoria in 1884. Women became eligible to vote for the Parliament of South Australia

in 1895. This was the first legislation in the world permitting women also to stand for election to political office and, in 1897, Catherine Helen Spence

became the first female political candidate for political office, unsuccessfully standing for election as a delegate to the Federal Convention on Australian Federation. Western Australia

granted voting rights to women in 1899.

Legally, Indigenous Australian males generally gained the right to vote during this period when Victoria, New South Wales, Tasmania and South Australia gave voting rights to all male British subjects over 21 - only Queensland and Western Australia barred Aboriginal people from voting. Thus, Aboriginal men and women voted in some jurisdictions for the first Commonwealth Parliament in 1901. Early federal parliamentary reform and judicial interpretation however sought to limit Aboriginal voting in practice - a situation which endured until rights activists began campaigning in the 1940s.

Though the various parliaments of Australia have been constantly evolving, the key foundations for elected parliamentary government have maintained an historical continuity in Australia from the 1850s into the 21st century.

By the late 1880s, a majority of people living in the Australian colonies were native born, although over 90% were of British and Irish origin. Historian Don Gibb suggests that bushranger

By the late 1880s, a majority of people living in the Australian colonies were native born, although over 90% were of British and Irish origin. Historian Don Gibb suggests that bushranger

Ned Kelly

represented one dimension of the emerging attitudes of the native born population. Identifying strongly with family and mates

, Kelly was opposed to what he regarded as oppression by Police and powerful Squatters

. Almost mirroring the Australian stereotype later defined by historian Russel Ward, Kelly became "a skilled bushman, adept with guns, horses and fists and winning admiration from his peers in the district." Journalist Vance Palmer suggested although Kelly came to typify "the rebellious persona of the country for later generations, (he really) belonged...to another period."

The origins of distinctly Australian painting is often associated with this period and the Heidelberg School

The origins of distinctly Australian painting is often associated with this period and the Heidelberg School

of the 1880s-1890s. Artists such as Arthur Streeton

, Frederick McCubbin

and Tom Roberts

applied themselves to recreating in their art a truer sense of light and colour as seen in Australian landscape. Like the European Impressionists, they painted in the open air. These artists found inspiration in the unique light and colour which characterises the Australian bush. Their most recognised work involves scenes of pastoral and wild Australia, featuring the vibrant, even harsh colours of Australian summers.

Australian literature

was equally developing a distinct voice. The classic Australian writers Henry Lawson

, Banjo Paterson

, Miles Franklin

, Norman Lindsay

, Steele Rudd

, Mary Gilmore

, C J Dennis and Dorothea McKellar were all forged by - and indeed helped to forge - this period of growing national identity. Views of Australia at times conflicted - Lawson and Paterson contributed a series of verses to The Bulletin

magazine in which they engaged in a literary debate about the nature of life in Australia: Lawson (a republican socialist) derided Paterson as a romantic, while Paterson (a country born city lawyer) thought Lawson full of doom and gloom. Paterson wrote the lyrics of the much-loved folksong Waltzing Matilda

in 1895. The song has often been suggested as an Australia's national anthem and Advance Australia Fair

, the Australian national anthem since the late 1970s, itself was written in 1887. Dennis wrote of laconic heroes in the Australian vernacular, while McKellar rejected a love of England's pleasant pastures in favour of what she termed a "Sunburnt Country" in her iconic poem: My Country

(1903).

A common theme throughout the nationalist art, music and writing of late 19th century was the romantic rural or bush

myth, ironically produced by one of the most urbanised societies in the world. Paterson's well known poem Clancy of the Overflow

, written in 1889, evokes the romantic myth. While bush ballads evidenced distinctively Australian popular medium of music and of literature, Australian artists of a more classical mould - such as the opera singer Dame Nellie Melba

, and painters John Peter Russell

and Rupert Bunny

- prefigured the 20th century expatriate Australians who knew little of 'stockyard and rails' but would travel abroad to influence Western art and culture.

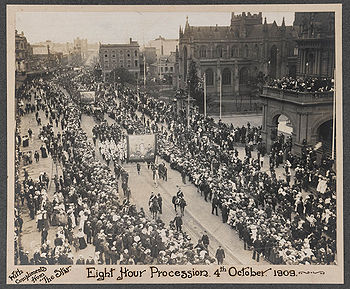

to the south eastern cities by telegraph in 1877, helped break down inter-colonial rivalries.

Amid calls from London for the establishment of an intercolonial Australian army, and with the various colonies independently constructing railway lines, New South Wales Premier Henry Parkes

addressed a rural audience in his 1889 Tenterfield Oration

, stating that the time had come to form a national executive government:

Parkes' vision called for a convention of Parliamentary representatives from the different colonies, to draft a constitution for the establishment of a national parliament, with two houses to legislate on "all great subjects". Though Parkes would not live to see it, each of these things would be achieved within a decade, and he is remembered as the "father of federation".

By 1895, powerful interests including various colonial politicians, the Australian Natives' Association and some newspapers were advocating Federation

. Increasing nationalism

, a growing sense of national identity amongst white colonial Australians, as well as a desire for a national immigration policy, (to become the white Australia policy

), combined with a recognition of the value of collective national defence also encouraged the Federation movement. The vision of most colonists was probably staunchly imperial however.

At a Federation Conference banquet in 1890, Henry Parkes spoke of blood-kinship linking the colonies:

Despite a more radical vision for a separate Australia by some colonists, including writer Henry Lawson

, trade unionist William Lane

and as found in the pages of the Sydney Bulletin

, by the end of 1899, and after much colonial debate, the citizens of five of the six Australian colonies had voted in referendums in favour of a constitution to form a Federation

. Western Australia

voted to join in July 1900. The "Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act (UK)" was passed on 5 July 1900 and given Royal Assent

by Queen Victoria

on 9 July 1900.

The Commonwealth of Australia came into being when the Federal Constitution

The Commonwealth of Australia came into being when the Federal Constitution

was proclaimed by the Governor General

, Lord Hopetoun

, on 1 January 1901. The first Federal elections

were held in March 1901 and resulted in a narrow majority for the Protectionist Party

over the Free Trade Party

with the Australian Labor Party

(ALP) polling third. Labor declared it would offer support to the party which offered concessions and Edmund Barton

's Protectionists formed a government, with Alfred Deakin

as Attorney General.