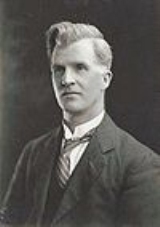

James Scullin

Encyclopedia

James Henry Scullin Australian Labor politician and the ninth Prime Minister of Australia

. Two days after he was sworn in as Prime Minister, the Wall Street Crash of 1929

occurred, marking the beginning of the Great Depression

and subsequent Great Depression in Australia

.

Scullin was born in the small town of Trawalla

Scullin was born in the small town of Trawalla

in Western Victoria

, the son of John Scullin, a railway worker, and Ann (née Logan), both of Irish Catholic descent from Derry

. He was educated at state primary schools and then worked as a grocer in Ballarat

while studying at night school and privately in public libraries and honing his public speaking skills in local debating clubs.

He joined the Labor Party

in 1903 and became an organiser for the Australian Workers' Union

. In 1913, he became editor of a Labor newspaper in Ballarat, the Evening Echo. He was a devout Roman Catholic, a non-drinker and a non-smoker all his life.

seat of Division of Ballarat

in 1906 against Alfred Deakin

, but lost. In 1910

he was elected to the House for the country seat of Corangamite

, but he was defeated in 1913

and went back to editing the Evening Echo.

He established a reputation as one of Labor's leading public speakers and experts on finance, and was a strong opponent of conscription

. After World War I he came close to outright pacifism

. In 1922 he won a by-election for the safe Labor seat of Yarra

in inner Melbourne, and in 1928 he was elected Labor leader following the resignation of Matthew Charlton

.

In 1929

In 1929

the conservative government of Stanley Bruce

fell when its industrial relations bill was defeated in the House of Representatives. In the subsequent elections Scullin campaigned as the defender of the industrial arbitration system and won a landslide victory, becoming Australia's first Roman Catholic Prime Minister. As this election was only for the House of Representatives

the conservatives

retained control of the Senate. Two days after Scullin took office on 22 October 1929, the New York stock market crashed and Australia became caught up in the worldwide Great Depression

.

The Depression hit Australia hard in 1930, with the collapse in export markets for Australia's agricultural products causing mass unemployment. Scullin's government, guided by orthodox economic advice, was unable to cope, and the Labor Party was rent by internal conflict over how to respond. The Treasurer (finance minister), Ted Theodore

, was an early advocate of Keynesian economic ideas, and advocated deficit financing as a means of reflating the economy, but his Cabinet colleagues Joseph Lyons

and James Fenton

strongly supported traditional deflationary economic policies.

In June 1930 the government suffered a heavy loss when Theodore was forced to resign after he was criticised by a Royal Commission inquiring into a scandal (the Mungana affair

) dating back to Theodore's time as Premier of Queensland

. Scullin took over the Treasury portfolio. Matters were made worse by Scullin's decision to travel to London to seek an emergency loan and to attend the Imperial Conference. While in London, Scullin succeeded in gaining loans for Australia at reduced interest. He also succeeded in having King George V

appoint Sir Isaac Isaacs

as the first Australian-born Governor-General

, despite the King's reluctance and the strong objections of both the British establishment and the conservative opposition in Australia, who attacked the appointment as tantamount to republicanism.

With Scullin out of the country for the whole second half of 1930, Fenton (as acting Prime Minister) and Lyons (as acting Treasurer) were left in charge. They insisted on pursuing deflationary policies, arousing great opposition in the Labor caucus. In regular contact with Fenton and Lyons in London through the awkward means of cables, Scullin felt he had no choice but to agree to the recommendations of advisers from the Bank of England

With Scullin out of the country for the whole second half of 1930, Fenton (as acting Prime Minister) and Lyons (as acting Treasurer) were left in charge. They insisted on pursuing deflationary policies, arousing great opposition in the Labor caucus. In regular contact with Fenton and Lyons in London through the awkward means of cables, Scullin felt he had no choice but to agree to the recommendations of advisers from the Bank of England

, supported by Lyons and Fenton, that government spending be heavily cut, despite the suffering this caused. These decisions led to furious infighting in the government and destroyed any semblance of party unity.

During 1931 the Scullin government disintegrated. In January, Scullin returned to Australia and decided to reinstate Theodore as Treasurer. Lyons, Fenton and their supporters resigned from the ministry in protest and soon joined up with the Nationalist

Opposition to form the United Australia Party

, led by Lyons. Meanwhile the Labor Premier of New South Wales

, Jack Lang was campaigning for economic policies much more left-wing than Theodore's, calling for Australia to repudiate its foreign debt and take other radical measures.

In March, Lang's supporters in the federal Parliament had split from the Labor Party, forming a "Lang Labor

" group, which, combined with the defections of Lyons and his supporters, had deprived the Scullin Government of its majority in the House of Representatives. However, the Government limped on until November, due to the reluctance of the Langite MPs to vote it down. Finally, however, on 25 November 1931, the Langite MPs, attacking the government with accusations of impropriety, voted with the Opposition to pass a motion of no confidence

, forcing an early election.

Labor was defeated in a massive landslide in 1931

Labor was defeated in a massive landslide in 1931

. The official Labor Party, which had won 46 seats out of 75 in the House of Representatives in 1929, was reduced to a mere 14 (Lang Labor won another 4), and Lyons became Prime Minister. Scullin felt traumatised by the experience of presiding over such a disastrous period, but stayed on as Labor leader.

After losing another election in 1934, he resigned the leadership. He remained in Parliament and became a trusted adviser to later Labor Prime Ministers John Curtin

and Ben Chifley

. He retired in 1949

and died in Melbourne in 1953 at the age of 76. Historians have judged him as a conscientious, well-meaning politician who was simply overwhelmed by events.

As Leader of the Opposition, Scullin had been a vocal opponent of the cost of The Lodge, the official residence of the Prime Minister. True to his word, he and his wife lived at the Hotel Canberra

during parliamentary sessions, and at their home in Melbourne at other times.

, he married Sarah Maria McNamara (1880–1962). The marriage was childless.

While no specific record of Sarah Scullin’s work as prime ministerial wife is available, a trace of her official, ceremonial and social duties can be gleaned from newspaper accounts of Scullin’s daily appointments. For instance, a three-day visit to Sydney soon after taking office involved Sarah Scullin’s participation in a wreath-laying ceremony at the Cenotaph, the silver jubilee banquet of the Labor women’s organising committee at Trades Hall in Sussex Street, and a lunch hosted by the New South Wales Institute of Journalists.

, a suburb of Canberra, is named after him, as is the Division of Scullin

, a House of Representatives electorate.

In 1975 he was honoured on a postage stamp bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post

.

Prime Minister of Australia

The Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Australia is the highest minister of the Crown, leader of the Cabinet and Head of Her Majesty's Australian Government, holding office on commission from the Governor-General of Australia. The office of Prime Minister is, in practice, the most powerful...

. Two days after he was sworn in as Prime Minister, the Wall Street Crash of 1929

Wall Street Crash of 1929

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 , also known as the Great Crash, and the Stock Market Crash of 1929, was the most devastating stock market crash in the history of the United States, taking into consideration the full extent and duration of its fallout...

occurred, marking the beginning of the Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

and subsequent Great Depression in Australia

Great Depression in Australia

Australia suffered badly during the period of the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Depression began with the Wall Street Crash of October, 1929 and rapidly spread worldwide. As in other nations, Australia suffered years of high unemployment, poverty, low profits, deflation, plunging incomes, and...

.

Early life

Trawalla, Victoria

Trawalla is a town in central Western Victoria, Australia, located on the Western Highway, 41 km west of Ballarat and 154 km west of Melbourne, in the Shire of Pyrenees. At the 2006 census, Trawalla and the surrounding agricultural area had a population of 224.Trawalla sits at the...

in Western Victoria

Victoria (Australia)

Victoria is the second most populous state in Australia. Geographically the smallest mainland state, Victoria is bordered by New South Wales, South Australia, and Tasmania on Boundary Islet to the north, west and south respectively....

, the son of John Scullin, a railway worker, and Ann (née Logan), both of Irish Catholic descent from Derry

Derry

Derry or Londonderry is the second-biggest city in Northern Ireland and the fourth-biggest city on the island of Ireland. The name Derry is an anglicisation of the Irish name Doire or Doire Cholmcille meaning "oak-wood of Colmcille"...

. He was educated at state primary schools and then worked as a grocer in Ballarat

Ballarat, Victoria

Ballarat is a city in the state of Victoria, Australia, approximately west-north-west of the state capital Melbourne situated on the lower plains of the Great Dividing Range and the Yarrowee River catchment. It is the largest inland centre and third most populous city in the state and the fifth...

while studying at night school and privately in public libraries and honing his public speaking skills in local debating clubs.

He joined the Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

in 1903 and became an organiser for the Australian Workers' Union

Australian Workers' Union

The Australian Workers' Union is one of Australia's largest and oldest trade unions. It traces its origins to unions founded in the pastoral and mining industries in the 1880s, and currently has approximately 135,000 members...

. In 1913, he became editor of a Labor newspaper in Ballarat, the Evening Echo. He was a devout Roman Catholic, a non-drinker and a non-smoker all his life.

Early political career

Scullin stood for the House of RepresentativesAustralian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is one of the two houses of the Parliament of Australia; it is the lower house; the upper house is the Senate. Members of Parliament serve for terms of approximately three years....

seat of Division of Ballarat

Division of Ballarat

The Division of Ballarat is an Australian Electoral Division in Victoria. The division was one of the original 75 divisions contested at the first federal election. It is named for the provincial city of Ballarat....

in 1906 against Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin , Australian politician, was a leader of the movement for Australian federation and later the second Prime Minister of Australia. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Deakin was a major contributor to the establishment of liberal reforms in the colony of Victoria, including the...

, but lost. In 1910

Australian federal election, 1910

Federal elections were held in Australia on 13 April 1910. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives, and 18 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election...

he was elected to the House for the country seat of Corangamite

Division of Corangamite

The Division of Corangamite is an Australian Electoral Division in Victoria. The division was one of the original 75 divisions contested at the first federal election...

, but he was defeated in 1913

Australian federal election, 1913

Federal elections were held in Australia on 31 May 1913. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives, and 18 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election. The incumbent Australian Labor Party led by Prime Minister of Australia Andrew Fisher was defeated by the opposition Commonwealth Liberal...

and went back to editing the Evening Echo.

He established a reputation as one of Labor's leading public speakers and experts on finance, and was a strong opponent of conscription

Conscription

Conscription is the compulsory enlistment of people in some sort of national service, most often military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and continues in some countries to the present day under various names...

. After World War I he came close to outright pacifism

Pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war and violence. The term "pacifism" was coined by the French peace campaignerÉmile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress inGlasgow in 1901.- Definition :...

. In 1922 he won a by-election for the safe Labor seat of Yarra

Division of Yarra

The Division of Yarra was an Australian Electoral Division in the state of Victoria. It was located in inner eastern suburban Melbourne, and was named after the Yarra River, which originally formed the eastern border of the Division, and eventually ran through it. It originally covered the suburbs...

in inner Melbourne, and in 1928 he was elected Labor leader following the resignation of Matthew Charlton

Matthew Charlton

Matthew Charlton was an Australian Labor Party politician.Charlton was born at Linton in rural Victoria but moved to Lambton, New South Wales at the age of five. He worked as a coal miner after only a primary education and then married Martha Rollings in 1889...

.

Prime Minister 1929–32

Australian federal election, 1929

Federal elections were held in Australia on 12 October 1929. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives were up for election, with no Senate seats up for election, as a result of Billy Hughes and other rebel backbenchers crossing the floor over industrial relations legislation, depriving the...

the conservative government of Stanley Bruce

Stanley Bruce

Stanley Melbourne Bruce, 1st Viscount Bruce of Melbourne, CH, MC, FRS, PC , was an Australian politician and diplomat, and the eighth Prime Minister of Australia. He was the second Australian granted an hereditary peerage of the United Kingdom, but the first whose peerage was formally created...

fell when its industrial relations bill was defeated in the House of Representatives. In the subsequent elections Scullin campaigned as the defender of the industrial arbitration system and won a landslide victory, becoming Australia's first Roman Catholic Prime Minister. As this election was only for the House of Representatives

Australian House of Representatives

The House of Representatives is one of the two houses of the Parliament of Australia; it is the lower house; the upper house is the Senate. Members of Parliament serve for terms of approximately three years....

the conservatives

Nationalist Party of Australia

The Nationalist Party of Australia was an Australian political party. It was formed on 17 February 1917 from a merger between the conservative Commonwealth Liberal Party and the National Labor Party, the name given to the pro-conscription defectors from the Australian Labor Party led by Prime...

retained control of the Senate. Two days after Scullin took office on 22 October 1929, the New York stock market crashed and Australia became caught up in the worldwide Great Depression

Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe worldwide economic depression in the decade preceding World War II. The timing of the Great Depression varied across nations, but in most countries it started in about 1929 and lasted until the late 1930s or early 1940s...

.

The Depression hit Australia hard in 1930, with the collapse in export markets for Australia's agricultural products causing mass unemployment. Scullin's government, guided by orthodox economic advice, was unable to cope, and the Labor Party was rent by internal conflict over how to respond. The Treasurer (finance minister), Ted Theodore

Ted Theodore

Edward Granville Theodore was an Australian politician. He was Premier of Queensland 1919–25, a federal politician representing a New South Wales seat 1927–31, and Federal Treasurer 1929–30.-Early life:...

, was an early advocate of Keynesian economic ideas, and advocated deficit financing as a means of reflating the economy, but his Cabinet colleagues Joseph Lyons

Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons, CH was an Australian politician. He was Labor Premier of Tasmania from 1923 to 1928 and a Minister in the James Scullin government from 1929 until his resignation from the Labor Party in March 1931...

and James Fenton

James Fenton (Australian politician)

James Edward Fenton CMG was an Australian politician. He is notable for having been appointed a cabinet minister by two governments of different political complexions, but resigning from both governments on matters of principle.Born at Nette Yallock, near Avoca, Victoria, Fenton was educated at a...

strongly supported traditional deflationary economic policies.

In June 1930 the government suffered a heavy loss when Theodore was forced to resign after he was criticised by a Royal Commission inquiring into a scandal (the Mungana affair

Mungana affair

The Mungana Affair involved the selling of some mining properties in the Chillagoe-Mungana districts of northern Queensland, Australia to the Queensland government, at a grossly inflated price...

) dating back to Theodore's time as Premier of Queensland

Queensland

Queensland is a state of Australia, occupying the north-eastern section of the mainland continent. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Australia and New South Wales to the west, south-west and south respectively. To the east, Queensland is bordered by the Coral Sea and Pacific Ocean...

. Scullin took over the Treasury portfolio. Matters were made worse by Scullin's decision to travel to London to seek an emergency loan and to attend the Imperial Conference. While in London, Scullin succeeded in gaining loans for Australia at reduced interest. He also succeeded in having King George V

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

appoint Sir Isaac Isaacs

Isaac Isaacs

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs GCB GCMG KC was an Australian judge and politician, was the third Chief Justice of Australia, ninth Governor-General of Australia and the first born in Australia to occupy that post. He is the only person ever to have held both positions of Chief Justice of Australia and...

as the first Australian-born Governor-General

Governor-General of Australia

The Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia is the representative in Australia at federal/national level of the Australian monarch . He or she exercises the supreme executive power of the Commonwealth...

, despite the King's reluctance and the strong objections of both the British establishment and the conservative opposition in Australia, who attacked the appointment as tantamount to republicanism.

Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694, it is the second oldest central bank in the world...

, supported by Lyons and Fenton, that government spending be heavily cut, despite the suffering this caused. These decisions led to furious infighting in the government and destroyed any semblance of party unity.

During 1931 the Scullin government disintegrated. In January, Scullin returned to Australia and decided to reinstate Theodore as Treasurer. Lyons, Fenton and their supporters resigned from the ministry in protest and soon joined up with the Nationalist

Nationalist Party of Australia

The Nationalist Party of Australia was an Australian political party. It was formed on 17 February 1917 from a merger between the conservative Commonwealth Liberal Party and the National Labor Party, the name given to the pro-conscription defectors from the Australian Labor Party led by Prime...

Opposition to form the United Australia Party

United Australia Party

The United Australia Party was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. It was the political successor to the Nationalist Party of Australia and predecessor to the Liberal Party of Australia...

, led by Lyons. Meanwhile the Labor Premier of New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

, Jack Lang was campaigning for economic policies much more left-wing than Theodore's, calling for Australia to repudiate its foreign debt and take other radical measures.

In March, Lang's supporters in the federal Parliament had split from the Labor Party, forming a "Lang Labor

Lang Labor

Lang Labor was the name commonly used to describe three successive break-away sections of the Australian Labor Party, all led by the New South Wales Labor leader Jack Lang premier of NSW .-Initial opposition to Lang's leadership:...

" group, which, combined with the defections of Lyons and his supporters, had deprived the Scullin Government of its majority in the House of Representatives. However, the Government limped on until November, due to the reluctance of the Langite MPs to vote it down. Finally, however, on 25 November 1931, the Langite MPs, attacking the government with accusations of impropriety, voted with the Opposition to pass a motion of no confidence

Motion of no confidence

A motion of no confidence is a parliamentary motion whose passing would demonstrate to the head of state that the elected parliament no longer has confidence in the appointed government.-Overview:Typically, when a parliament passes a vote of no...

, forcing an early election.

Australian federal election, 1931

Federal elections were held in Australia on 19 December 1931. All 75 seats in the House of Representatives, and 18 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election...

. The official Labor Party, which had won 46 seats out of 75 in the House of Representatives in 1929, was reduced to a mere 14 (Lang Labor won another 4), and Lyons became Prime Minister. Scullin felt traumatised by the experience of presiding over such a disastrous period, but stayed on as Labor leader.

After losing another election in 1934, he resigned the leadership. He remained in Parliament and became a trusted adviser to later Labor Prime Ministers John Curtin

John Curtin

John Joseph Curtin , Australian politician, served as the 14th Prime Minister of Australia. Labor under Curtin formed a minority government in 1941 after the crossbench consisting of two independent MPs crossed the floor in the House of Representatives, bringing down the Coalition minority...

and Ben Chifley

Ben Chifley

Joseph Benedict Chifley , Australian politician, was the 16th Prime Minister of Australia. He took over the Australian Labor Party leadership and Prime Ministership after the death of John Curtin in 1945, and went on to retain government at the 1946 election, before being defeated at the 1949...

. He retired in 1949

Australian federal election, 1949

Federal elections were held in Australia on 10 December 1949. All 121 seats in the House of Representatives, and 42 of the 60 seats in the Senate were up for election, where the single transferable vote was introduced...

and died in Melbourne in 1953 at the age of 76. Historians have judged him as a conscientious, well-meaning politician who was simply overwhelmed by events.

As Leader of the Opposition, Scullin had been a vocal opponent of the cost of The Lodge, the official residence of the Prime Minister. True to his word, he and his wife lived at the Hotel Canberra

Hotel Canberra

The Hotel Canberra, also known as Hyatt Hotel Canberra is in Yarralumla, near Lake Burley Griffin and Parliament House, in Canberra. It was built to house politicians when the Federal Parliament moved to Canberra. It was constructed by the contractor John Howie between 1922-1925. Originally...

during parliamentary sessions, and at their home in Melbourne at other times.

Sarah Scullin

On 11 November 1907, in Ballarat, VictoriaBallarat, Victoria

Ballarat is a city in the state of Victoria, Australia, approximately west-north-west of the state capital Melbourne situated on the lower plains of the Great Dividing Range and the Yarrowee River catchment. It is the largest inland centre and third most populous city in the state and the fifth...

, he married Sarah Maria McNamara (1880–1962). The marriage was childless.

While no specific record of Sarah Scullin’s work as prime ministerial wife is available, a trace of her official, ceremonial and social duties can be gleaned from newspaper accounts of Scullin’s daily appointments. For instance, a three-day visit to Sydney soon after taking office involved Sarah Scullin’s participation in a wreath-laying ceremony at the Cenotaph, the silver jubilee banquet of the Labor women’s organising committee at Trades Hall in Sussex Street, and a lunch hosted by the New South Wales Institute of Journalists.

Honours

Scullin, Australian Capital TerritoryScullin, Australian Capital Territory

Scullin is a suburb in the Canberra district of Belconnen. The postcode is 2614. The suburb is named after Prime Minister James Henry Scullin. It was gazetted on 6 June 1968. Streets are named after aviators....

, a suburb of Canberra, is named after him, as is the Division of Scullin

Division of Scullin

The Division of Scullin is an Australian Electoral Division in the state of Victoria. It is located in the northern suburbs of Melbourne, including Epping, Lalor, Bundoora, Mill Park and Plenty....

, a House of Representatives electorate.

In 1975 he was honoured on a postage stamp bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post

Australia Post

Australia Post is the trading name of the Australian Government-owned Australian Postal Corporation .-History:...

.

Further reading

- Denning, Warren (1937), Caucus Crisis: the Rise and Fall of the Scullin Government, Parramatta (NSW).

- Hughes, Colin AColin HughesColin Anfield Hughes is an Australian academic specializing in electoral politics and government.He received his B.A. and M.A. degrees from Columbia University and his Ph.D from the London School of Economics. In 1966, along with John S...

(1976), Mr Prime Minister. Australian Prime Ministers 1901–1972, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, Victoria, Ch.10. ISBN 0 19 550471 2 - Robertson, John (1974), J.H. Scullin. A Political Biography, University of Western Australia Press, Nedlands (WA).