Australian frontier wars

Encyclopedia

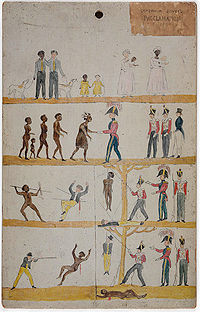

The Australian frontier wars were a series of conflicts fought between Indigenous Australians

and European settlers. The first fighting took place in May 1788 and the last clashes occurred in the early 1930s. Indigenous fatalities from the fighting have been estimated as at least 20,000 and European deaths as between 2,000 and 2,500. Far more devastating, however, was the effect of disease which significantly reduced the Indigenous population by the beginning of the 20th century and may have limited their ability to resist.

made the first voyage by Europeans along the Australian east coast. On 29 April Cook and a small landing party fired on a group of Tharawal people

who threatened them when they attempted to come ashore at Botany Bay

. Two Tharawal men threw spears at the British, before fleeing in alarm after being fired on again. Cook did not make further contact with the Tharawal, but later established a peaceful relationship with the Kokobujundji people when his ship, HM Bark Endeavour

, had to be repaired at present-day Cooktown

.

Cook, in his voyage up the east coast of Australia, observed no signs of European-style agriculture or other development by its inhabitants. Some historians argue that the prevailing European law was such land was deemed terra nullius

or land belonging to nobody or land 'empty of inhabitants' (as defined by Emerich de Vattel

). Cook claimed the east coast of the continent for Britain on 23 August 1770.

The British Government decided to establish a prison colony in Australia in 1786. Some historians argue that Britain took possession of Australia under the European legal doctrine that it was terra nullius

. Under this classification Indigenous Australians' were not recognised as having property rights and territory could be acquired through 'original occupation' rather than conquest or consent. The colony's Governor

, Captain Arthur Phillip

, was instructed to "live in amity and kindness" with Indigenous Australians, however and sought to avoid conflict.

However, other historians argue as an inhabited land annexed by Britain, colonists could be granted the right to occupy such areas of the annexed land that did not appear to be under cultivation or some other kind of development (such as a village or town) but were generally expected to respect the property rights of the original inhabitants. These historians contend that as, in European terms, property rights were principally exercised by the cultivation of land, the marking of boundaries and by the building of permanent buildings and settlements, the settlers did not believe that Indigenous Australians claimed property rights to the lands they roamed over. Instead, nomadic hunter-gatherers seemed, to the Europeans, to be concerned only with the right to hunt and kill the wild game, which was their principal source of food. Many of the violent incidents between white settlers and Aborigines seem to have occurred when Aborigines objected to settlers hunting wild game, rather than because the settlers were 'occupying' Aboriginal territory.

established Sydney

on 26 January 1788. The local Indigenous people became suspicious when the British began to clear land and catch fish, and in May 1788 five convicts were killed and an Indigenous man was wounded. The British grew increasingly concerned when groups of up to three hundred Indigenous people were sighted at the outskirts of the settlement in June. Despite this, Phillip attempted to avoid conflict, and forbade reprisals after being speared in 1790. He did, however, authorise two punitive expeditions in December 1790 after his huntsman was killed by an Indigenous warrior named Pemulwuy

, but neither was successful.

During the 1790s and early 19th century the British established small settlements along the Australian coastline. These settlements initially occupied small amounts of land, and there was little conflict between the settlers and Indigenous peoples. Fighting broke out when the settlements expanded however, disrupting traditional Indigenous food-gathering activities, and subsequently followed the pattern of European settlement in Australia for the next 150 years. Indeed whilst the reactions of the Aboriginal inhabitants to the sudden arrival of British settlers were varied, they became inevitably hostile when their presence led to competition over resources, and to the occupation of their lands. European diseases decimated Indigeous populations, and the occupation or destruction of lands and food resources sometimes led to starvation. By and large neither the Europeans nor the Indigenous peoples approached the conflict in an organised sense, with the conflict more one between groups of settlers and individual tribes rather than systematic warfare, even if at times it did involve British soldiers and later formed mounted police units. Not all Indigenous Australians resisted white encroachment on their lands either, whilst many also served in mounted police units and were involved in attacks on other tribes. Regardless a pattern of frontier warfare emerges, with Indigenous resistance beginning in the 18th century and continuing into the early 20th century, belying the "myth" of peaceful settlement in Australia. Settlers in turn often reacted with violence, resulting in a number of indiscriminate massacre

s.

It is wrong, however, to depict the conflict as one sided and mainly perpetrated by Europeans on Indigenous Australians. Although many more died than Europeans, some cases of mass killing were not massacres but military defeats, and this may have had more to do with the technological and logistic advantages enjoyed by Europeans. Indigenous tactics varied, but were mainly based on pre-existing hunting and fighting practices—utilising spears, clubs and other primitive weapons. Unlike the indigenous peoples of New Zealand and North America

, on the main they failed to adapt to meet the challenge of the Europeans, and although there were some instances of individuals and groups acquiring and using firearms, this was not widespread. In reality the Indigenous peoples were never a serious military threat, regardless of how much the settlers may have feared them. On occasions large groups attacked Europeans in open terrain and a conventional battle ensued, during which the Aborigines would attempt to use superior numbers to their advantage. This could sometimes be effective, with reports of them advancing in crescent formation in an attempt to outflank and surround their opponents, waiting out the first volley of shots and then hurling their spears whilst the settlers reloaded. Usually however such open warfare proved more costly for the Indigenous Australians than the Europeans.

Central to the success of the Europeans was the use of firearms, however the advantages this afforded have often been overstated. Prior to the mid-19th century, firearms were cumbersome muzzle-loading, smooth-bore, single shot weapons with flint-lock mechanisms. Such weapons produced a low rate of fire, whilst suffering from a high rate of failure and were only accurate within 50 metres (164 ft). These deficiencies may have given the Aborigines some advantages, allowing them to move in close and engage with spears or war clubs. However by the 1850s-60s significant advances in firearms gave the Europeans a distinct advantage, with the six-shot Colt revolver, the Snider single shot breech-loading rifle

and later the Martini-Henry rifle as well as rapid-fire rifles such as the Winchester rifle

, becoming available. These weapons, when used on open ground and combined with the superior mobility provided by horses to surround and engage groups of Indigenous Australians, often proved successful. The Europeans also had to adapt their tactics to fight their fast-moving, often hidden enemies. Strategies employed included mounted parties, dawn attacks, and attacking from several directions simultaneously.

Fighting between Indigenous Australians and European settlers was localised as Indigenous groups did not form confederations capable of sustained resistance. As a result, there was not a single conventional war, but rather a series of isolated violent engagements across the continent, most of it low level and resulting in few casualties.

According to the historian Geoffrey Blainey

, in Australia during the colonial period: "In a thousand isolated places there were occasional shootings and spearings. Even worse, smallpox, measles, influenza and other new diseases swept from one Aboriginal camp to another ... The main conqueror of Aborigines was to be disease and it ally, demoralisation".

The Caledon Bay crisis

of 1932-4 saw one of the last incidents of violent interaction on the 'frontier' of indigenous and non-indigenous Australia, which began when the spearing of Japanese poachers who had been molesting Yolngu

women was followed by the killing of a policeman. As the crisis unfolded, national opinion swung behind the Aboriginal people involved, and the first appeal on behalf of an Indigenous Australian to the High Court of Australia

was launched. Following the crisis, the anthropologist Donald Thompson

was despatched by the government to live among the Yolngu. Elsewhere around this time, activists like Sir Douglas Nicholls

were commencing their campaigns for Aboriginal rights within the established Australian political system and the age of frontier conflict closed.

Frontier encounters in Australia were not universally negative. Positive accounts of Aboriginal customs and encounters are also recorded in the journals of early European explorers, who often relied on Aboriginal guides and assistance: Charles Sturt

employed Aboriginal envoys to explore the Murray-Darling; the lone survivor of the Burke and Wills expedition was nursed by local Aborigines, and the famous Aboriginal explorer Jackey Jackey

loyally accompanied his ill-fated friend Edmund Kennedy

to Cape York

. Respectful studies were conducted by such as Walter Baldwin Spencer

and Frank Gillen in their renowned anthropological study The Native Tribes of Central Australia (1899); and by Donald Thompson

of Arnhem Land

(c.1935-1943). In inland Australia, the skills of Aboriginal stockmen became highly regarded and in the 20th century, Aboriginal stockmen like Vincent Lingiari

became national figures in their campagins for better pay and conditions.

west of Sydney. Some of these settlements were established by soldiers as a means of providing security to the region. The local Darug people

raided farms until Governor Macquarie

dispatched troops from the British Army

46th Regiment

in 1816. These troops patrolled the Hawkesbury Valley and ended the conflict by killing 14 Indigenous Australians in a raid on their campsite. Indigenous Australians led by Pemulwuy also conducted raids around Parramatta

during the period between 1795 and 1802. These attacks led Governor Philip Gidley King

to issue an order in 1801 which authorised settlers to shoot Indigenous Australians on sight in Parramatta, Georges River

and Prospect

areas.

Conflict began again when the British expanded into inland New South Wales

. The settlers who crossed the Blue Mountains were harassed by Wiradjuri

warriors, who killed or wounded stock-keepers and stock and were subjected to retaliatory killings. In response, Governor Brisbane

proclaimed martial law

on 14 August 1824 to end "...the Slaughter of Black Women and Children, and unoffending White Men...". It remained in force until 11 December 1824, when it was proclaimed that "...the judicious and humane Measures pursued by the Magistrates assembled at Bathurst have restored Tranquillity without Bloodshed...". There is a display of the weaponry and history of this conflict at the National Museum of Australia

. This includes a commendation by Governor Brisbane

of the deployment of the troops under Major Morisset

: "I felt it necessary to augment the Detachment at Bathurst to 75 men who were divided into various small parties, each headed by a Magistrate who proceeded in different directions in towards the interior of the Country ... This system of keeping these unfortunate People in a constant state of alarm soon brought them to a sense of their Duty, and ... Saturday

their great and most warlike Chieftain has been with me to receive his pardon and that He, with most of His Tribe, attended the annual conference held here on the 28th Novr...."

Brisbane

also established the New South Wales Mounted Police, who began as mounted infantry from the 3rd Regiment, and were first deployed against bushrangers around Bathurst in 1825. Later they were deployed to the upper Hunter Valley

in 1826 after fighting broke out there between Wonnarua

and Kamilaroi

people and settlers.

The British established a settlement in Van Diemen's Land

The British established a settlement in Van Diemen's Land

(modern Tasmania

) in 1803. Relations with the local Indigenous people were generally peaceful until the mid-1820s when pastoral

expansion caused conflict over land. This led to sustained frontier warfare (the 'Black War

'), and in some districts farmers were forced to fortify their houses. Over 50 British were killed between 1828 and 1830 in what was the "most successful Aboriginal resistance in Australia's history".

In 1830 Lieutenant-Governor

Arthur

attempted to end the 'Black War' through a massive offensive. In an operation which became known as the 'Black Line

' ten percent of the colony's male civilian population were mobilised and marched across the settled districts in company with police and soldiers in an attempt to clear Indigenous Australians from the area. While few Indigenous people were captured, the operation discouraged the Indigenous raiding parties, and they gradually agreed to leave their land for a reservation which had been established at Flinders Island

.

. The initial settlement at Fort Dundas

on Melville Island was established in 1824 but was abandoned in 1829 due to attacks from the local Tiwi people

. Some fighting also took place near Fort Wellington on the Cobourg Peninsula

between its establishment in 1827 and abandonment in 1829. The third British settlement, Fort Victoria, was also established on the Cobourg Peninsula in 1838 but was abandoned in 1845.

was established by the British Army at Albany

in 1826. Relations between the garrison and the local Minang people were generally good. Open conflict between Noongar

and European settlers broke out in Western Australia in the 1830s as the Swan River Colony

expanded from Perth

. The Battle of Pinjarra

is the best known single event, it was fought on 28 October 1833 between a party of British soldiers and mounted police led by Governor

Stirling

attacked an Indigenous campsite on the banks of the Murray River

.

The Noongar people forced from traditional hunting grounds and denied access to sacred sites turned to stealing settlers crops and killing livestock to supplement their food supply. In 1831 a Noongar person was killed taking potatoes this resulted in Yagan

killing a servant of the household as was the response permitted under tribal law. In 1832 Yagan and two others were arrested and sentenced to death, settler Robert Menli Lyon argued that Yagan was defending his land from invasion as such he should be treated as a prisoner of war. The argument was successful and the three men were exiled to Carnac Island

under the supervision of Lyon and two soldiers, the group later escaped from the island.

Fighting continued on into the 1840s along the Avon River

near York

.

The discovery of gold near Coolgardie

in 1892 brought thousands of prospectors onto Wangkathaa

land, causing sporadic fighting.

, with 16 British and up to 500 Indigenous Australians being killed between 1832 and 1838. The fighting in this region included several massacres of Indigenous people including as the Waterloo Creek massacre

and Myall Creek massacre

s in 1838 and did not end until 1843. Further fighting took place in the New England

region during the early 1840s.

Fighting also took place in Victoria

after it was settled by British in 1834. A clash at Benalla

in 1838 marked the beginning of frontier conflict in the colony which lasted for fifteen years. The Indigenous groups in Victoria concentrated on economic warfare

, killing tens of thousands of sheep. Large numbers of British settlers arrived in Victoria during the 1840s, and rapidly outnumbered the Indigenous population. By the late 1840s frontier conflict was limited to the Wimmera

and Gippsland

. Considerable fighting also took place in South Australia

between 1839 and 1841.

The frontier wars on the eastern Australian plains were particularly bitter in south-east and central Queensland

. British settlers reached the Darling Downs in 1840, leading to widespread fighting and heavy loss of life. The conflict later spread north to the Wide Bay-Hervey Bay region, and at one stage the settlement of Maryborough

was virtually under siege. Both sides committed atrocities, with settlers on the Darling Downs poisoning Indigenous people in 1842 and Indigenous warriors killing 19 settlers during the Cullin-La-Ringo massacre

on 17 October 1861.

held settlers out of Western Queensland for ten years until September 1884 when they attacked a force of settlers and native police at Battle Mountain near modern Cloncurry

. The subsequent Battle of Battle Mountain

ended in disaster for the Kalkadoon, who suffered heavy losses. Fighting continued in north Queensland

, however, with Indigenous raiders attacking sheep and cattle while native police mounted punitive expeditions. Overall, the fighting in north Queensland was the most significant of the frontier wars, with Indigenous warriors killing at least 470 settlers and native police and at least 4,000 Indigenous people being killed after 1860.

Continued European expansion in Western Australia led to further frontier conflict, Banuba raiders also attacked European settlements during the 1890s until their leader was killed in 1897. Sporadic conflict continued in northern Western Australia until the 1920s, with a Royal Commission held in 1926 finding that at least eleven Indigenous Australians had been killed in the Forrest River massacre

by a police expedition in retaliation for the death of a European.

. A permanent settlement was established at modern-day Darwin

in 1869 and attempts by pastoralists to occupy Indigenous land led to conflict. This fighting continued into the 20th century, and was driven by reprisals against European deaths and the pastoralists' desire to secure their land. At least 31 Indigenous men were killed by police in the Coniston massacre

in 1928 and further reprisal expeditions were conducted in 1932 and 1933.

W.E.H. Stanner

wrote that historians' failure to include Indigenous Australians in histories of Australia or acknowledge widespread frontier conflict constituted a 'great Australian silence'. Works which discussed the conflicts began to appear during the 1970s and 1980s, and the first history of the Australian frontier told from an Indigenous perspective, Henry Reynolds

' The Other Side of the Frontier

, was published in 1982.

Between 2000 and 2002 Keith Windschuttle

published a series of articles in the magazine Quadrant

and the book The Fabrication of Aboriginal History. These works argued that there had not been prolonged frontier warfare in Australia, and that historians had in some instances fabricated evidence of fighting. Windschuttle's claims led to the so-called 'History wars

' in which historians debated the extent of the conflict between Indigenous Australians and European settlers.

The frontier wars are not commemorated at the Australian War Memorial

in Canberra

. The Memorial argues that the Australian frontier fighting is outside its charter as it did not involve Australian military forces. This position is supported by the Returned and Services League of Australia

but is opposed by many historians, including Geoffrey Blainey

, Gordon Briscoe, John Coates

, John Connor, Ken Inglis

, Michael McKernan and Peter Stanley

. These historians argue that the fighting should be commemorated at the Memorial as it involved large numbers of Indigenous Australians and paramilitary Australian units.

Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians are the original inhabitants of the Australian continent and nearby islands. The Aboriginal Indigenous Australians migrated from the Indian continent around 75,000 to 100,000 years ago....

and European settlers. The first fighting took place in May 1788 and the last clashes occurred in the early 1930s. Indigenous fatalities from the fighting have been estimated as at least 20,000 and European deaths as between 2,000 and 2,500. Far more devastating, however, was the effect of disease which significantly reduced the Indigenous population by the beginning of the 20th century and may have limited their ability to resist.

Background

In 1770 a British expedition under the command of then-Lieutenant James CookJames Cook

Captain James Cook, FRS, RN was a British explorer, navigator and cartographer who ultimately rose to the rank of captain in the Royal Navy...

made the first voyage by Europeans along the Australian east coast. On 29 April Cook and a small landing party fired on a group of Tharawal people

Tharawal people

The Tharawal people were the Aboriginal inhabitants of southern Sydney and the Illawarra region in 1788, when the first European colonists arrived. The Tharawal people lived in the areas from south side of Botany Bay, around Port Hacking to north of the Shoalhaven River and inland to Campbelltown...

who threatened them when they attempted to come ashore at Botany Bay

Botany Bay

Botany Bay is a bay in Sydney, New South Wales, a few kilometres south of the Sydney central business district. The Cooks River and the Georges River are the two major tributaries that flow into the bay...

. Two Tharawal men threw spears at the British, before fleeing in alarm after being fired on again. Cook did not make further contact with the Tharawal, but later established a peaceful relationship with the Kokobujundji people when his ship, HM Bark Endeavour

HM Bark Endeavour

HMS Endeavour, also known as HM Bark Endeavour, was a British Royal Navy research vessel commanded by Lieutenant James Cook on his first voyage of discovery, to Australia and New Zealand from 1769 to 1771....

, had to be repaired at present-day Cooktown

Cooktown, Queensland

Cooktown is a small town located at the mouth of the Endeavour River, on Cape York Peninsula in Far North Queensland where James Cook beached his ship, the Endeavour, for repairs in 1770. At the 2006 census, Cooktown had a population of 1,336...

.

Cook, in his voyage up the east coast of Australia, observed no signs of European-style agriculture or other development by its inhabitants. Some historians argue that the prevailing European law was such land was deemed terra nullius

Terra nullius

Terra nullius is a Latin expression deriving from Roman law meaning "land belonging to no one" , which is used in international law to describe territory which has never been subject to the sovereignty of any state, or over which any prior sovereign has expressly or implicitly relinquished...

or land belonging to nobody or land 'empty of inhabitants' (as defined by Emerich de Vattel

Emerich de Vattel

Emer de Vattel was a Swiss philosopher, diplomat, and legal expert whose theories laid the foundation of modern international law and political philosophy. He was born in Couvet in Neuchatel, Switzerland in 1714 and died in 1767 of edema...

). Cook claimed the east coast of the continent for Britain on 23 August 1770.

The British Government decided to establish a prison colony in Australia in 1786. Some historians argue that Britain took possession of Australia under the European legal doctrine that it was terra nullius

Terra nullius

Terra nullius is a Latin expression deriving from Roman law meaning "land belonging to no one" , which is used in international law to describe territory which has never been subject to the sovereignty of any state, or over which any prior sovereign has expressly or implicitly relinquished...

. Under this classification Indigenous Australians' were not recognised as having property rights and territory could be acquired through 'original occupation' rather than conquest or consent. The colony's Governor

Governors of New South Wales

The Governor of New South Wales is the state viceregal representative of the Australian monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, who is equally shared with 15 other sovereign nations in a form of personal union, as well as with the eleven other jurisdictions of Australia, and resides predominantly in her...

, Captain Arthur Phillip

Arthur Phillip

Admiral Arthur Phillip RN was a British admiral and colonial administrator. Phillip was appointed Governor of New South Wales, the first European colony on the Australian continent, and was the founder of the settlement which is now the city of Sydney.-Early life and naval career:Arthur Phillip...

, was instructed to "live in amity and kindness" with Indigenous Australians, however and sought to avoid conflict.

However, other historians argue as an inhabited land annexed by Britain, colonists could be granted the right to occupy such areas of the annexed land that did not appear to be under cultivation or some other kind of development (such as a village or town) but were generally expected to respect the property rights of the original inhabitants. These historians contend that as, in European terms, property rights were principally exercised by the cultivation of land, the marking of boundaries and by the building of permanent buildings and settlements, the settlers did not believe that Indigenous Australians claimed property rights to the lands they roamed over. Instead, nomadic hunter-gatherers seemed, to the Europeans, to be concerned only with the right to hunt and kill the wild game, which was their principal source of food. Many of the violent incidents between white settlers and Aborigines seem to have occurred when Aborigines objected to settlers hunting wild game, rather than because the settlers were 'occupying' Aboriginal territory.

History

Violence between Indigenous Australians and Europeans began several months after the First FleetFirst Fleet

The First Fleet is the name given to the eleven ships which sailed from Great Britain on 13 May 1787 with about 1,487 people, including 778 convicts , to establish the first European colony in Australia, in the region which Captain Cook had named New South Wales. The fleet was led by Captain ...

established Sydney

Sydney

Sydney is the most populous city in Australia and the state capital of New South Wales. Sydney is located on Australia's south-east coast of the Tasman Sea. As of June 2010, the greater metropolitan area had an approximate population of 4.6 million people...

on 26 January 1788. The local Indigenous people became suspicious when the British began to clear land and catch fish, and in May 1788 five convicts were killed and an Indigenous man was wounded. The British grew increasingly concerned when groups of up to three hundred Indigenous people were sighted at the outskirts of the settlement in June. Despite this, Phillip attempted to avoid conflict, and forbade reprisals after being speared in 1790. He did, however, authorise two punitive expeditions in December 1790 after his huntsman was killed by an Indigenous warrior named Pemulwuy

Pemulwuy

Pemulwuy was an Aboriginal Australian man born around 1750 in the area of Botany Bay in New South Wales. He is noted for his resistance to the European settlement of Australia which began with the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788. He is believed to have been a member of the Bidjigal clan of...

, but neither was successful.

During the 1790s and early 19th century the British established small settlements along the Australian coastline. These settlements initially occupied small amounts of land, and there was little conflict between the settlers and Indigenous peoples. Fighting broke out when the settlements expanded however, disrupting traditional Indigenous food-gathering activities, and subsequently followed the pattern of European settlement in Australia for the next 150 years. Indeed whilst the reactions of the Aboriginal inhabitants to the sudden arrival of British settlers were varied, they became inevitably hostile when their presence led to competition over resources, and to the occupation of their lands. European diseases decimated Indigeous populations, and the occupation or destruction of lands and food resources sometimes led to starvation. By and large neither the Europeans nor the Indigenous peoples approached the conflict in an organised sense, with the conflict more one between groups of settlers and individual tribes rather than systematic warfare, even if at times it did involve British soldiers and later formed mounted police units. Not all Indigenous Australians resisted white encroachment on their lands either, whilst many also served in mounted police units and were involved in attacks on other tribes. Regardless a pattern of frontier warfare emerges, with Indigenous resistance beginning in the 18th century and continuing into the early 20th century, belying the "myth" of peaceful settlement in Australia. Settlers in turn often reacted with violence, resulting in a number of indiscriminate massacre

Massacre

A massacre is an event with a heavy death toll.Massacre may also refer to:-Entertainment:*Massacre , a DC Comics villain*Massacre , a 1932 drama film starring Richard Barthelmess*Massacre, a 1956 Western starring Dane Clark...

s.

It is wrong, however, to depict the conflict as one sided and mainly perpetrated by Europeans on Indigenous Australians. Although many more died than Europeans, some cases of mass killing were not massacres but military defeats, and this may have had more to do with the technological and logistic advantages enjoyed by Europeans. Indigenous tactics varied, but were mainly based on pre-existing hunting and fighting practices—utilising spears, clubs and other primitive weapons. Unlike the indigenous peoples of New Zealand and North America

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of North and South America, their descendants and other ethnic groups who are identified with those peoples. Indigenous peoples are known in Canada as Aboriginal peoples, and in the United States as Native Americans...

, on the main they failed to adapt to meet the challenge of the Europeans, and although there were some instances of individuals and groups acquiring and using firearms, this was not widespread. In reality the Indigenous peoples were never a serious military threat, regardless of how much the settlers may have feared them. On occasions large groups attacked Europeans in open terrain and a conventional battle ensued, during which the Aborigines would attempt to use superior numbers to their advantage. This could sometimes be effective, with reports of them advancing in crescent formation in an attempt to outflank and surround their opponents, waiting out the first volley of shots and then hurling their spears whilst the settlers reloaded. Usually however such open warfare proved more costly for the Indigenous Australians than the Europeans.

Central to the success of the Europeans was the use of firearms, however the advantages this afforded have often been overstated. Prior to the mid-19th century, firearms were cumbersome muzzle-loading, smooth-bore, single shot weapons with flint-lock mechanisms. Such weapons produced a low rate of fire, whilst suffering from a high rate of failure and were only accurate within 50 metres (164 ft). These deficiencies may have given the Aborigines some advantages, allowing them to move in close and engage with spears or war clubs. However by the 1850s-60s significant advances in firearms gave the Europeans a distinct advantage, with the six-shot Colt revolver, the Snider single shot breech-loading rifle

Snider-Enfield

The British .577 Snider-Enfield was a type of breech loading rifle. The firearm action was invented by the American Jacob Snider, and the Snider-Enfield was one of the most widely used of the Snider varieties. It was adopted by British Army as a conversion system for its ubiquitous Pattern 1853...

and later the Martini-Henry rifle as well as rapid-fire rifles such as the Winchester rifle

Winchester rifle

In common usage, Winchester rifle usually means any of the lever-action rifles manufactured by the Winchester Repeating Arms Company, though the company has also manufactured many rifles of other action types...

, becoming available. These weapons, when used on open ground and combined with the superior mobility provided by horses to surround and engage groups of Indigenous Australians, often proved successful. The Europeans also had to adapt their tactics to fight their fast-moving, often hidden enemies. Strategies employed included mounted parties, dawn attacks, and attacking from several directions simultaneously.

Fighting between Indigenous Australians and European settlers was localised as Indigenous groups did not form confederations capable of sustained resistance. As a result, there was not a single conventional war, but rather a series of isolated violent engagements across the continent, most of it low level and resulting in few casualties.

According to the historian Geoffrey Blainey

Geoffrey Blainey

Geoffrey Norman Blainey AC , is a prominent Australian historian.Blainey was born in Melbourne and raised in a series of Victorian country towns before attending Wesley College and the University of Melbourne. While at university he was editor of Farrago, the newspaper of the University of...

, in Australia during the colonial period: "In a thousand isolated places there were occasional shootings and spearings. Even worse, smallpox, measles, influenza and other new diseases swept from one Aboriginal camp to another ... The main conqueror of Aborigines was to be disease and it ally, demoralisation".

The Caledon Bay crisis

Caledon Bay crisis

The Caledon Bay crisis refers to a series of killings at Caledon Bay in the Northern Territory of Australia during 1932–34. These events are widely seen as a turning point in relations between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians....

of 1932-4 saw one of the last incidents of violent interaction on the 'frontier' of indigenous and non-indigenous Australia, which began when the spearing of Japanese poachers who had been molesting Yolngu

Yolngu

The Yolngu or Yolŋu are an Indigenous Australian people inhabiting north-eastern Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia. Yolngu means “person” in the Yolŋu languages.-Yolŋu law:...

women was followed by the killing of a policeman. As the crisis unfolded, national opinion swung behind the Aboriginal people involved, and the first appeal on behalf of an Indigenous Australian to the High Court of Australia

High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the supreme court in the Australian court hierarchy and the final court of appeal in Australia. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction, has the power of judicial review over laws passed by the Parliament of Australia and the parliaments of the States, and...

was launched. Following the crisis, the anthropologist Donald Thompson

Donald Thompson

Sir Donald Thompson was a British Conservative Party politician. He was a Member of Parliament from 1979 until 1997.Thompson attended Holy Trinity School, Halifax, and Hipperholme Grammar School...

was despatched by the government to live among the Yolngu. Elsewhere around this time, activists like Sir Douglas Nicholls

Douglas Nicholls

Sir Douglas Ralph "Doug" Nicholls KCVO, OBE, was a prominent Aboriginal Australian from the Yorta Yorta people. He was a professional athlete, Churches of Christ pastor and church planter, ceremonial officer and a pioneering campaigner for reconciliation.Nicholls was the first Aboriginal person to...

were commencing their campaigns for Aboriginal rights within the established Australian political system and the age of frontier conflict closed.

Frontier encounters in Australia were not universally negative. Positive accounts of Aboriginal customs and encounters are also recorded in the journals of early European explorers, who often relied on Aboriginal guides and assistance: Charles Sturt

Charles Sturt

Captain Charles Napier Sturt was an English explorer of Australia, and part of the European Exploration of Australia. He led several expeditions into the interior of the continent, starting from both Sydney and later from Adelaide. His expeditions traced several of the westward-flowing rivers,...

employed Aboriginal envoys to explore the Murray-Darling; the lone survivor of the Burke and Wills expedition was nursed by local Aborigines, and the famous Aboriginal explorer Jackey Jackey

Jackey Jackey

William Westwood was often referred to as a "gentleman bushranger" because of his dress and respect for his victims. He got the name 'Jackey Jackey' from the aboriginal people...

loyally accompanied his ill-fated friend Edmund Kennedy

Edmund Kennedy

Edmund Besley Court Kennedy was an explorer in Australia in the mid nineteenth century. He was the Assistant-Surveyor of New South Wales, working with Sir Thomas Mitchell...

to Cape York

Cape York Peninsula

Cape York Peninsula is a large remote peninsula located in Far North Queensland at the tip of the state of Queensland, Australia, the largest unspoilt wilderness in northern Australia and one of the last remaining wilderness areas on Earth...

. Respectful studies were conducted by such as Walter Baldwin Spencer

Walter Baldwin Spencer

Sir Walter Baldwin Spencer KCMG was a British-Australian biologist and anthropologist.Baldwin was born in Stretford, Lancashire. His father, Reuben Spencer, who had come from Derbyshire in his youth, obtained a position with Rylands and Sons, cotton manufacturers, and rose to be chairman of its...

and Frank Gillen in their renowned anthropological study The Native Tribes of Central Australia (1899); and by Donald Thompson

Donald Thompson

Sir Donald Thompson was a British Conservative Party politician. He was a Member of Parliament from 1979 until 1997.Thompson attended Holy Trinity School, Halifax, and Hipperholme Grammar School...

of Arnhem Land

Arnhem Land

The Arnhem Land Region is one of the five regions of the Northern Territory of Australia. It is located in the north-eastern corner of the territory and is around 500 km from the territory capital Darwin. The region has an area of 97,000 km² which also covers the area of Kakadu National...

(c.1935-1943). In inland Australia, the skills of Aboriginal stockmen became highly regarded and in the 20th century, Aboriginal stockmen like Vincent Lingiari

Vincent Lingiari

Vincent Lingiarri, AM , was an Aboriginal rights activist who was appointed as a Member of the Order of Australia for his services to the Aboriginal people. Lingiarri was a member of the Gurindji people. In Vincent's earlier life he worked as a stockman at Wave Hill Cattle Station. He also played...

became national figures in their campagins for better pay and conditions.

New South Wales

The first frontier war began in 1795 when the British established farms along the Hawkesbury RiverHawkesbury River

The Hawkesbury River, also known as Deerubbun, is one of the major rivers of the coastal region of New South Wales, Australia. The Hawkesbury River and its tributaries virtually encircle the metropolitan region of Sydney.-Geography:-Course:...

west of Sydney. Some of these settlements were established by soldiers as a means of providing security to the region. The local Darug people

Darug people

The Darug people are a language group of Indigenous Australians, who are traditional custodians of much of what is modern day Sydney. There is some dispute about the extent of the Darug nation. Some historians believe the coastal Eora people were a separate tribe to the Darug...

raided farms until Governor Macquarie

Lachlan Macquarie

Major-General Lachlan Macquarie CB , was a British military officer and colonial administrator. He served as the last autocratic Governor of New South Wales, Australia from 1810 to 1821 and had a leading role in the social, economic and architectural development of the colony...

dispatched troops from the British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

46th Regiment

46th (South Devonshire) Regiment of Foot

The 46th Regiment of Foot was an infantry regiment of the British Army, created in 1741 and amalgamated into the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry in 1881.-History:...

in 1816. These troops patrolled the Hawkesbury Valley and ended the conflict by killing 14 Indigenous Australians in a raid on their campsite. Indigenous Australians led by Pemulwuy also conducted raids around Parramatta

Parramatta, New South Wales

Parramatta is a suburb of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. It is located in Greater Western Sydney west of the Sydney central business district on the banks of the Parramatta River. Parramatta is the administrative seat of the Local Government Area of the City of Parramatta...

during the period between 1795 and 1802. These attacks led Governor Philip Gidley King

Philip Gidley King

Captain Philip Gidley King RN was a British naval officer and colonial administrator. He is best known as the official founder of the first European settlement on Norfolk Island and as the third Governor of New South Wales.-Early years and establishment of Norfolk Island settlement:King was born...

to issue an order in 1801 which authorised settlers to shoot Indigenous Australians on sight in Parramatta, Georges River

Georges River

The Georges River is a waterway in the state of New South Wales in Australia. It rises to the south-west of Sydney near the coal mining town of Appin, and then flows north past Campbelltown, roughly parallel to the Main South Railway...

and Prospect

Prospect, New South Wales

Prospect is a suburb of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Prospect is located 32 kilometres west of the Sydney central business district in the local government area of the City of Blacktown and is part of the Greater Western Sydney region....

areas.

Conflict began again when the British expanded into inland New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

. The settlers who crossed the Blue Mountains were harassed by Wiradjuri

Wiradjuri

The Wiradjuri are an Indigenous Australian group of central New South Wales.In the 21st century, major Wiradjuri groups live in Condobolin, Peak Hill, Narrandera and Griffith...

warriors, who killed or wounded stock-keepers and stock and were subjected to retaliatory killings. In response, Governor Brisbane

Thomas Brisbane

Major-General Sir Thomas Makdougall Brisbane, 1st Baronet GCH, GCB, FRS, FRSE was a British soldier, colonial Governor and astronomer.-Early life:...

proclaimed martial law

Martial law

Martial law is the imposition of military rule by military authorities over designated regions on an emergency basis— only temporary—when the civilian government or civilian authorities fail to function effectively , when there are extensive riots and protests, or when the disobedience of the law...

on 14 August 1824 to end "...the Slaughter of Black Women and Children, and unoffending White Men...". It remained in force until 11 December 1824, when it was proclaimed that "...the judicious and humane Measures pursued by the Magistrates assembled at Bathurst have restored Tranquillity without Bloodshed...". There is a display of the weaponry and history of this conflict at the National Museum of Australia

National Museum of Australia

The National Museum of Australia was formally established by the National Museum of Australia Act 1980. The National Museum preserves and interprets Australia's social history, exploring the key issues, people and events that have shaped the nation....

. This includes a commendation by Governor Brisbane

Thomas Brisbane

Major-General Sir Thomas Makdougall Brisbane, 1st Baronet GCH, GCB, FRS, FRSE was a British soldier, colonial Governor and astronomer.-Early life:...

of the deployment of the troops under Major Morisset

James Thomas Morisset

Lieutenant-Colonel James Thomas Morisset , penal administrator, was commandant of the second convict settlement at Norfolk Island, from 29 June 1829 to 1834....

: "I felt it necessary to augment the Detachment at Bathurst to 75 men who were divided into various small parties, each headed by a Magistrate who proceeded in different directions in towards the interior of the Country ... This system of keeping these unfortunate People in a constant state of alarm soon brought them to a sense of their Duty, and ... Saturday

Windradyne

Windradyne was an Aboriginal warrior and resistance leader of the Wiradjuri nation, in what is now central-western New South Wales, Australia; he was also known to the British settlers as Saturday...

their great and most warlike Chieftain has been with me to receive his pardon and that He, with most of His Tribe, attended the annual conference held here on the 28th Novr...."

Brisbane

Thomas Brisbane

Major-General Sir Thomas Makdougall Brisbane, 1st Baronet GCH, GCB, FRS, FRSE was a British soldier, colonial Governor and astronomer.-Early life:...

also established the New South Wales Mounted Police, who began as mounted infantry from the 3rd Regiment, and were first deployed against bushrangers around Bathurst in 1825. Later they were deployed to the upper Hunter Valley

Hunter Valley

The Hunter Region, more commonly known as the Hunter Valley, is a region of New South Wales, Australia, extending from approximately to north of Sydney with an approximate population of 645,395 people. Most of the population of the Hunter Region lives within of the coast, with 55% of the entire...

in 1826 after fighting broke out there between Wonnarua

Wonnarua

The Wonnarua people are an Aboriginal Australian people whose territory is located in the Hunter Valley of Australia.-External links:* Accessed 15 May 2010* Accessed 15 May 2010* Accessed 16 May 2010...

and Kamilaroi

Kamilaroi

The Kamilaroi or Gamilaraay are an Indigenous Australian people who are from the area between Tamworth and Goondiwindi, and west to Narrabri, Walgett and Lightning Ridge, in northern New South Wales...

people and settlers.

Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the original name used by most Europeans for the island of Tasmania, now part of Australia. The Dutch explorer Abel Tasman was the first European to land on the shores of Tasmania...

(modern Tasmania

Tasmania

Tasmania is an Australian island and state. It is south of the continent, separated by Bass Strait. The state includes the island of Tasmania—the 26th largest island in the world—and the surrounding islands. The state has a population of 507,626 , of whom almost half reside in the greater Hobart...

) in 1803. Relations with the local Indigenous people were generally peaceful until the mid-1820s when pastoral

Pastoralism

Pastoralism or pastoral farming is the branch of agriculture concerned with the raising of livestock. It is animal husbandry: the care, tending and use of animals such as camels, goats, cattle, yaks, llamas, and sheep. It may have a mobile aspect, moving the herds in search of fresh pasture and...

expansion caused conflict over land. This led to sustained frontier warfare (the 'Black War

Black War

The Black War is a term used to describe a period of conflict between British colonists and Tasmanian Aborigines in the early nineteenth century...

'), and in some districts farmers were forced to fortify their houses. Over 50 British were killed between 1828 and 1830 in what was the "most successful Aboriginal resistance in Australia's history".

In 1830 Lieutenant-Governor

Governors of Tasmania

The Governor of Tasmania is the representative in the Australian state of Tasmania of Elizabeth II, Queen of Australia. The Governor performs the same constitutional and ceremonial functions at the state level as the Governor-General of Australia does at the national level.In accordance with the...

Arthur

George Arthur

Lieutenant-General Sir George Arthur, 1st Baronet KCH PC was Lieutenant Governor of British Honduras , Van Diemen's Land and Upper Canada . He also served as Governor of Bombay .-Early life:George Arthur was born in Plymouth, England...

attempted to end the 'Black War' through a massive offensive. In an operation which became known as the 'Black Line

Black Line

The Black Line was an event that occurred in 1830 in Tasmania, or Van Diemen's Land as it was then known. After many years of conflict between British colonists and the Aborigines known as the Black War, Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur decided to remove all Aborigines from the settled areas in...

' ten percent of the colony's male civilian population were mobilised and marched across the settled districts in company with police and soldiers in an attempt to clear Indigenous Australians from the area. While few Indigenous people were captured, the operation discouraged the Indigenous raiding parties, and they gradually agreed to leave their land for a reservation which had been established at Flinders Island

Flinders Island

Flinders Island may refer to:In Australia:* Flinders Island , in the Furneaux Group, is the largest and best known* Flinders Island * Flinders Island , in the Investigator Group* Flinders Island...

.

Northern Australia

The British made three attempts to establish military outposts in northern AustraliaNorthern Australia

The term northern Australia is generally known to include two State and Territories, being Queensland and the Northern Territory . The part of Western Australia north of latitude 26° south—a definition widely used in law and State government policy—is also usually included...

. The initial settlement at Fort Dundas

Fort Dundas

Fort Dundas was a short lived British settlement on Melville Island between 1824 and 1828 in what is now the Northern Territory of Australia. The establishment of the settlement caused the border of New South Wales to be moved west from the 135th meridian to the Western Australia border .The...

on Melville Island was established in 1824 but was abandoned in 1829 due to attacks from the local Tiwi people

Tiwi people

The Tiwi people are one of the many Indigenous groups of Australia. Nearly 2,500 Tiwi live in the Bathurst and Melville Islands, which make up the Tiwi Islands....

. Some fighting also took place near Fort Wellington on the Cobourg Peninsula

Cobourg Peninsula

The Cobourg Peninsula is located 350 kilometres east of Darwin in the Northern Territory, Australia. It is deeply indented with coves and bays, covers a land area of about 2,100 km², and is virtually uninhabited with a population ranging from about 20 to 30 in five family outstations, but...

between its establishment in 1827 and abandonment in 1829. The third British settlement, Fort Victoria, was also established on the Cobourg Peninsula in 1838 but was abandoned in 1845.

Western Australia

The first British settlement in Western AustraliaWestern Australia

Western Australia is a state of Australia, occupying the entire western third of the Australian continent. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Great Australian Bight and Indian Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east and South Australia to the south-east...

was established by the British Army at Albany

Albany, Western Australia

Albany is a port city in the Great Southern region of Western Australia, some 418 km SE of Perth, the state capital. As of 2009, Albany's population was estimated at 33,600, making it the 6th-largest city in the state....

in 1826. Relations between the garrison and the local Minang people were generally good. Open conflict between Noongar

Noongar

The Noongar are an indigenous Australian people who live in the south-west corner of Western Australia from Geraldton on the west coast to Esperance on the south coast...

and European settlers broke out in Western Australia in the 1830s as the Swan River Colony

Swan River Colony

The Swan River Colony was a British settlement established in 1829 on the Swan River, in Western Australia. The name was a pars pro toto for Western Australia. In 1832, the colony was officially renamed Western Australia, when the colony's founding Lieutenant-Governor, Captain James Stirling,...

expanded from Perth

Perth, Western Australia

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia and the fourth most populous city in Australia. The Perth metropolitan area has an estimated population of almost 1,700,000....

. The Battle of Pinjarra

Battle of Pinjarra

The Battle of Pinjarra or Pinjarra Massacre was a conflict that occurred in Pinjarra, Western Australia between a group of 60 to 80 Australian Aborigines and a detachment of 25 soldiers and policemen led by Governor James Stirling in 1834...

is the best known single event, it was fought on 28 October 1833 between a party of British soldiers and mounted police led by Governor

Governor of Western Australia

The Governor of Western Australia is the representative in Western Australia of Australia's Monarch, Queen Elizabeth II. The Governor performs important constitutional, ceremonial and community functions, including:* presiding over the Executive Council;...

Stirling

James Stirling (Australian governor)

Admiral Sir James Stirling RN was a British naval officer and colonial administrator. His enthusiasm and persistence persuaded the British Government to establish the Swan River Colony and he became the first Governor and Commander-in-Chief of Western Australia...

attacked an Indigenous campsite on the banks of the Murray River

Murray River (Western Australia)

The Murray River is a river in the southwest of Western Australia which played a significant part in the expansion of Aboriginal settlement in the area south of Perth after the arrival of British settlers at the Swan River Colony in 1829....

.

The Noongar people forced from traditional hunting grounds and denied access to sacred sites turned to stealing settlers crops and killing livestock to supplement their food supply. In 1831 a Noongar person was killed taking potatoes this resulted in Yagan

Yagan

Yagan was an Australian Aboriginal warrior from the Noongar tribe who played a key part in early indigenous Australian resistance to British settlement and rule in the area of Perth, Western Australia. After he led a series of burglaries and robberies across the countryside, in which white...

killing a servant of the household as was the response permitted under tribal law. In 1832 Yagan and two others were arrested and sentenced to death, settler Robert Menli Lyon argued that Yagan was defending his land from invasion as such he should be treated as a prisoner of war. The argument was successful and the three men were exiled to Carnac Island

Carnac Island

Carnac Island is a 19 ha, A Class, island nature reserve about 10 km south-west of Fremantle in Western Australia.-History:In 1803, French explorer Louis de Freycinet, captain of the Casuarina, named the island Île Pelée . It was also known as Île Lévilian and later Île Berthelot...

under the supervision of Lyon and two soldiers, the group later escaped from the island.

Fighting continued on into the 1840s along the Avon River

Avon River (Western Australia)

The Avon River is a river in Western Australia. It is a tributary of the Swan River totalling 280 kilometres in length, with a catchment area of 125,000 square kilometres.-Catchment area:...

near York

York, Western Australia

York is the oldest inland town in Western Australia, situated 97 km east of Perth in the Avon Valley near Northam, and is the seat of the Shire of York...

.

The discovery of gold near Coolgardie

Coolgardie, Western Australia

Coolgardie is a small town in the Australian state of Western Australia, east of the state capital, Perth. It has a population of approximately 800 people....

in 1892 brought thousands of prospectors onto Wangkathaa

Wangai

Wangai, Wongai or Wankai is the name given by themselves to the 26 Aboriginal groups of the Goldfields of Western Australia. It comes from the word meaning "Speaker"...

land, causing sporadic fighting.

Wars on the plains

From the 1830s British settlement spread rapidly through inland eastern Australia, leading to widespread conflict. Fighting took place across the Liverpool PlainsLiverpool Plains

The Liverpool Plains is a geographical area and Local Government Area in the North West Slopes, New South Wales.The Shire was formed on 17 March 2004 by the amalgamation of Quirindi Shire with parts of three other shires: Parry, Murrurundi and Gunnedah.- Main towns :* Quirindi* Ardglen*...

, with 16 British and up to 500 Indigenous Australians being killed between 1832 and 1838. The fighting in this region included several massacres of Indigenous people including as the Waterloo Creek massacre

Waterloo Creek massacre

The Waterloo Creek Massacre is the title commonly given to a conflict between mounted police and indigenous Australians in January 1838. The events have been subject to much dispute due to conflicting accounts of what took place and specifically the number of fatalities...

and Myall Creek massacre

Myall Creek massacre

Myall Creek Massacre involved the killing of up to 30 unarmed Australian Aborigines by European settlers on 10 June 1838 at the Myall Creek near Bingara in northern New South Wales...

s in 1838 and did not end until 1843. Further fighting took place in the New England

New England (Australia)

New England or New England North West is the name given to a generally undefined region about 60 kilometres inland, that includes the Northern Tablelands and the North West Slopes regions in the north of the state of New South Wales, Australia.-History:The region has been occupied by Indigenous...

region during the early 1840s.

Fighting also took place in Victoria

Victoria (Australia)

Victoria is the second most populous state in Australia. Geographically the smallest mainland state, Victoria is bordered by New South Wales, South Australia, and Tasmania on Boundary Islet to the north, west and south respectively....

after it was settled by British in 1834. A clash at Benalla

Benalla, Victoria

Benalla is a city of just over 9,000 people located just off the Hume Freeway in north-eastern Victoria, Australia, about southwest of Wangaratta. Its Local Government Area is the Rural City of Benalla.- Overview :...

in 1838 marked the beginning of frontier conflict in the colony which lasted for fifteen years. The Indigenous groups in Victoria concentrated on economic warfare

Economic warfare

Economic warfare is the term for economic policies followed as a part of military operations during wartime.The purpose of economic warfare is to capture critical economic resources so that the military can operate at full efficiency and/or deprive the enemy forces of those resources so that they...

, killing tens of thousands of sheep. Large numbers of British settlers arrived in Victoria during the 1840s, and rapidly outnumbered the Indigenous population. By the late 1840s frontier conflict was limited to the Wimmera

Wimmera

The Wimmera is a region in the west of the Australian state of Victoria.It covers the dryland farming area south of the range of Mallee scrub, east of the South Australia border and north of the Great Dividing Range...

and Gippsland

Gippsland

Gippsland is a large rural region in Victoria, Australia. It begins immediately east of the suburbs of Melbourne and stretches to the New South Wales border, lying between the Great Dividing Range to the north and Bass Strait to the south...

. Considerable fighting also took place in South Australia

South Australia

South Australia is a state of Australia in the southern central part of the country. It covers some of the most arid parts of the continent; with a total land area of , it is the fourth largest of Australia's six states and two territories.South Australia shares borders with all of the mainland...

between 1839 and 1841.

The frontier wars on the eastern Australian plains were particularly bitter in south-east and central Queensland

Queensland

Queensland is a state of Australia, occupying the north-eastern section of the mainland continent. It is bordered by the Northern Territory, South Australia and New South Wales to the west, south-west and south respectively. To the east, Queensland is bordered by the Coral Sea and Pacific Ocean...

. British settlers reached the Darling Downs in 1840, leading to widespread fighting and heavy loss of life. The conflict later spread north to the Wide Bay-Hervey Bay region, and at one stage the settlement of Maryborough

Maryborough, Queensland

Maryborough is a city located on the Mary River in South East Queensland, Australia, approximately north of the state capital, Brisbane. The city is serviced by the Bruce Highway, and has a population of approximately 22,000 . It is closely tied to its neighbour city Hervey Bay which is...

was virtually under siege. Both sides committed atrocities, with settlers on the Darling Downs poisoning Indigenous people in 1842 and Indigenous warriors killing 19 settlers during the Cullin-La-Ringo massacre

Cullin-La-Ringo massacre

The Cullin-La-Ringo massacre, which occurred in central Queensland on 17 October 1861, was the largest massacre of white settlers by Aborigines in Australia....

on 17 October 1861.

Western and north Queensland and northern Western Australia

In the 1870s most conflict took place in western and north Queensland and northern Western Australia. Raids conducted by the KalkadoonKalkadoon

Kalkadoon, Indigenous Australian tribe living in the Mount Isa region of Queensland. In 1884 they were massacred at "Battle Mountain", in a fight against police....

held settlers out of Western Queensland for ten years until September 1884 when they attacked a force of settlers and native police at Battle Mountain near modern Cloncurry

Cloncurry, Queensland

-Notable residents:*Writer Alexis Wright grew up in Cloncurry.*Association Footballer Kasey Wehrman was born in Cloncurry . He went on to play domestically and in Scandinavia. His achievements include winning a NSL Championship in 1996-1997 with the Brisbane Strikers and being capped several times...

. The subsequent Battle of Battle Mountain

Battle of Battle Mountain

The Battle of Battle Mountain was an engagement between United Nations and North Korean forces early in the Korean War from August 15 to September 19, 1950, on and around the Sobuk-san mountain area in South Korea. It was one of several large engagements fought simultaneously during the Battle of...

ended in disaster for the Kalkadoon, who suffered heavy losses. Fighting continued in north Queensland

North Queensland

North Queensland or the Northern Region is the northern part of the state of Queensland in Australia. Queensland is a massive state, larger than most countries, and the tropical northern part of it has been historically remote and undeveloped, resulting in a distinctive regional character and...

, however, with Indigenous raiders attacking sheep and cattle while native police mounted punitive expeditions. Overall, the fighting in north Queensland was the most significant of the frontier wars, with Indigenous warriors killing at least 470 settlers and native police and at least 4,000 Indigenous people being killed after 1860.

Continued European expansion in Western Australia led to further frontier conflict, Banuba raiders also attacked European settlements during the 1890s until their leader was killed in 1897. Sporadic conflict continued in northern Western Australia until the 1920s, with a Royal Commission held in 1926 finding that at least eleven Indigenous Australians had been killed in the Forrest River massacre

Forrest River massacre

The Forrest River massacre, or Oombulgurri massacre, was a massacre of Indigenous Australian people by a law enforcement party in the wake of the killing of a pastoralist, which took place in the Kimberley region of Western Australia in 1926. The massacre was investigated by a Royal Commission in...

by a police expedition in retaliation for the death of a European.

Northern Territory

The final battles of the Australian frontier wars took place in the Northern TerritoryNorthern Territory

The Northern Territory is a federal territory of Australia, occupying much of the centre of the mainland continent, as well as the central northern regions...

. A permanent settlement was established at modern-day Darwin

Darwin, Northern Territory

Darwin is the capital city of the Northern Territory, Australia. Situated on the Timor Sea, Darwin has a population of 127,500, making it by far the largest and most populated city in the sparsely populated Northern Territory, but the least populous of all Australia's capital cities...

in 1869 and attempts by pastoralists to occupy Indigenous land led to conflict. This fighting continued into the 20th century, and was driven by reprisals against European deaths and the pastoralists' desire to secure their land. At least 31 Indigenous men were killed by police in the Coniston massacre

Coniston massacre

The Coniston massacre, which took place from 14 August to 18 October 1928 near the Coniston cattle station, Northern Territory, Australia, was the last known massacre of Indigenous Australians. People of the Warlpiri, Anmatyerre and Kaytetye groups were killed...

in 1928 and further reprisal expeditions were conducted in 1932 and 1933.

Historiography

The existence of armed resistance to white settlement was generally not acknowledged by historians until the 1970s. In 1968 anthropologistAnthropology

Anthropology is the study of humanity. It has origins in the humanities, the natural sciences, and the social sciences. The term "anthropology" is from the Greek anthrōpos , "man", understood to mean mankind or humanity, and -logia , "discourse" or "study", and was first used in 1501 by German...

W.E.H. Stanner

Bill Stanner

W.E.H. Stanner was an Australian anthropologist who worked extensively with Indigenous Australians. Stanner had a varied career that also included journalism in the 1930s, military service in World War II, and political advice on colonial policy in Africa and the South Pacific in the post-war...

wrote that historians' failure to include Indigenous Australians in histories of Australia or acknowledge widespread frontier conflict constituted a 'great Australian silence'. Works which discussed the conflicts began to appear during the 1970s and 1980s, and the first history of the Australian frontier told from an Indigenous perspective, Henry Reynolds

Henry Reynolds (historian)

Henry Reynolds is an eminent Australian historian whose primary work has focused on the frontier conflict between European settlement of Australia and indigenous Australians.-Education and career:...

' The Other Side of the Frontier

The Other Side of the Frontier

The Other Side of the Frontier: Aboriginal Resistance to the European invasion of Australia is a history book published in 1981 by Australian historian Henry Reynolds...

, was published in 1982.

Between 2000 and 2002 Keith Windschuttle

Keith Windschuttle

Keith Windschuttle is an Australian writer, historian, and ABC board member, who has authored several books from the 1970s onwards. These include Unemployment, , which analysed the economic causes and social consequences of unemployment in Australia and advocated a socialist response; The Media: a...

published a series of articles in the magazine Quadrant

Quadrant (magazine)

Quadrant is an Australian literary and cultural journal. The magazine takes a conservative position on political and social issues, describing itself as sceptical of 'unthinking Leftism, or political correctness, and its "smelly little orthodoxies"'. Quadrant reviews literature, as well as...

and the book The Fabrication of Aboriginal History. These works argued that there had not been prolonged frontier warfare in Australia, and that historians had in some instances fabricated evidence of fighting. Windschuttle's claims led to the so-called 'History wars

History wars

The history wars in Australia are an ongoing public debate over the interpretation of the history of the British colonisation of Australia and development of contemporary Australian society...

' in which historians debated the extent of the conflict between Indigenous Australians and European settlers.

The frontier wars are not commemorated at the Australian War Memorial

Australian War Memorial

The Australian War Memorial is Australia's national memorial to the members of all its armed forces and supporting organisations who have died or participated in the wars of the Commonwealth of Australia...

in Canberra

Canberra

Canberra is the capital city of Australia. With a population of over 345,000, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The city is located at the northern end of the Australian Capital Territory , south-west of Sydney, and north-east of Melbourne...

. The Memorial argues that the Australian frontier fighting is outside its charter as it did not involve Australian military forces. This position is supported by the Returned and Services League of Australia

Returned and Services League of Australia

The Returned and Services League of Australia is a support organisation for men and women who have served or are serving in the Australian Defence Force ....

but is opposed by many historians, including Geoffrey Blainey

Geoffrey Blainey

Geoffrey Norman Blainey AC , is a prominent Australian historian.Blainey was born in Melbourne and raised in a series of Victorian country towns before attending Wesley College and the University of Melbourne. While at university he was editor of Farrago, the newspaper of the University of...

, Gordon Briscoe, John Coates

John Coates (general)

Lieutenant General Henry John Coates AC, MBE is a former senior officer in the Australian Army who served as Chief of the General Staff...

, John Connor, Ken Inglis

Ken Inglis

Kenneth Stanley Inglis is an Australian historian.Inglis completed his Master's degree at the University of Melbourne and his doctorate at the University of Oxford. In 1956 he was appointed as a lecturer to the University of Adelaide...

, Michael McKernan and Peter Stanley

Peter Stanley

Dr Peter Stanley is an Australian historian. He is Head of the Centre for Historical Research at the National Museum of Australia. Between 1980 and 2007 he was an historian and curator at the Australian War Memorial, including as head of the Historical Research Section and Principal Historian...

. These historians argue that the fighting should be commemorated at the Memorial as it involved large numbers of Indigenous Australians and paramilitary Australian units.

See also

- List of massacres of Indigenous Australians

- American Indian Wars, comparable events in U.S. historyHistory of the United StatesThe history of the United States traditionally starts with the Declaration of Independence in the year 1776, although its territory was inhabited by Native Americans since prehistoric times and then by European colonists who followed the voyages of Christopher Columbus starting in 1492. The...

- Arauco WarArauco WarThe Arauco War was a conflict between colonial Spaniards and the Mapuche people in what is now the Araucanía and Biobío regions of modern Chile...

and Conquest of the DesertConquest of the DesertThe Conquest of the Desert was a military campaign directed mainly by General Julio Argentino Roca in the 1870s, which established Argentine dominance over Patagonia, which was inhabited by indigenous peoples...

, comparable events in Chile and Argentina