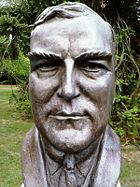

Robert Menzies

Encyclopedia

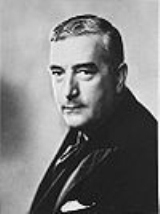

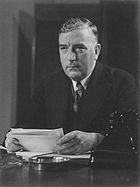

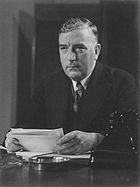

Sir Robert Gordon Menzies, (20 December 1894 – 15 May 1978), Australian politician, was the 12th and longest-serving Prime Minister of Australia

.

His first term as Prime Minister commenced in 1939, after the death in office of the United Australia Party

leader Joseph Lyons

and a short-term interim premiership by Sir Earle Page

. His party narrowly won the 1940 election

, which produced a hung parliament

, with the support of independent MPs in the House. A year later, his government was brought down by those same MPs crossing the floor

. He spent eight years in opposition, during which he founded the Liberal Party of Australia

. He again became Prime Minister at the 1949 election

, and he then dominated Australian politics until his retirement in 1966.

Menzies was renowned as a brilliant speaker, both on the floor of Parliament and on the hustings; his speech "The Forgotten People

" is an example of his oratorical skills. Throughout his life and career, Menzies held strong beliefs in the Monarchy and in traditional ties with Britain. In 1963 Menzies was invested as the first and only Australian Knight of the Order of the Thistle

. Menzies is regarded highly in Prime Ministerial opinion polls and is very highly regarded in Australian society for his tenures as Prime Minister.

, a town in the Wimmera

region of western Victoria

, on 20 December 1894. His father James was a storekeeper, the son of Scottish

crofters who had immigrated to Australia in the mid-1850s in the wake of the Victorian gold rush

. His maternal grandfather, John Sampson, was a Cornish

miner from Penzance

who also came to seek his fortune on the goldfields, in Ballarat

. Menzies was proud of his mother's origin, Cornish author A.L. Rowse tells us that 'When Menzies visited us [at All Souls College, Oxford] he told me that he was a Cornish Sampson on his mother's side.' His father and one of his uncles had been members of the Victorian Parliament, while another uncle had represented Wimmera in the House of Representatives. He was proud of his Highland

ancestry his enduring nickname, Ming, came from ˈmɪŋəs, the Scots

– and his own preferred – pronunciation of Menzies. His middle name, Gordon, was given to him in honour and memory of Charles George Gordon

, a British army officer killed in Khartoum

in 1885.

Menzies was first educated at a one-room school, then later at private schools in Ballarat and Melbourne (Wesley College

), and studied law at the University of Melbourne

graduating in 1916.

When World War I began, Menzies was 19 years old and held a commission in the university's militia unit. Menzies resigned his commission at the very time others of his age and class clamoured to be allowed to enlist. It was later stated that, since the family had made enough of a sacrifice to the war with the enlistment of two of three eligible brothers, Menzies should stay to finish his studies. Menzies himself never explained the reason why he chose not to enlist. Subsequently he was prominent in undergraduate activities and won academic prizes and declared himself to be a patriotic supporter of the war and conscription. Menzies was admitted to the Victorian Bar and to the High Court of Australia in 1918 and soon became one of Melbourne's leading lawyers after establishing his own practice. In 1920 he married Pattie Leckie

, the daughter of federal Nationalist

, and later Liberal, MP, John Leckie

.

from East Yarra Province

, representing the Nationalist Party of Australia

. His candidacy was nearly defeated when a group of ex-servicemen attacked him in the press for not having enlisted, but he survived this crisis. The following year he shifted to the Legislative Assembly

as the member for Nunawading

. Before the election, he founded the Young Nationalists as his party's youth wing and served as its first president. He was Deputy Premier of Victoria

from May 1932 until July 1934.

Menzies transferred to federal politics in 1934, representing the United Australia Party

(UAP—the Nationalists had merged with other non-Labor groups to form the UAP during his tenure as a state parliamentarian) in the upper-class Melbourne electorate of Kooyong

. He was immediately appointed Attorney-General and Minister for Industry in the Lyons government. In 1937 he was appointed a Privy Councillor

.

In late 1934 and early 1935 Menzies unsuccessfully prosecuted the Lyons government's case for the attempted exclusion from Australia of Egon Kisch

, a Czech Jewish communist. Because of this, some accused Menzies of being pro-Nazi, whilst others saw it as an early example of his strong opposition to communism. Following the outbreak of World War II Menzies found it necessary to distance himself from the controversy by claiming Interior Minister Thomas Paterson

was responsible since he made the initial order to exclude Kisch.

Animosity developed between Earle Page

and Menzies which was aggravated when Page became Acting Prime Minister during Lyons' illness after October 1938. Menzies and Page attacked each other publicly. He later became deputy leader of the UAP. His supporters said he was Lyons's natural successor; his critics accused Menzies of wanting to push Lyons out, a charge he denied. In 1938 his enemies ridiculed him as "Pig Iron Bob", the result of his industrial battle with waterside workers who refused to load scrap iron being sold to Imperial Japan. In 1939, however, he resigned from the Cabinet in protest at postponement of the national insurance scheme. With Lyons' sudden death on 7 April 1939, Page became acting Prime Minister until the UAP could elect a leader.

On 18 April, Menzies was elected Leader of the UAP and was sworn in as Prime Minister eight days later. A crisis arose almost immediately, however, when Page refused to serve under him. In an extraordinary personal attack in the House, Page accused Menzies of cowardice for not having enlisted in the War, and of treachery to Lyons. Menzies then formed a minority government

On 18 April, Menzies was elected Leader of the UAP and was sworn in as Prime Minister eight days later. A crisis arose almost immediately, however, when Page refused to serve under him. In an extraordinary personal attack in the House, Page accused Menzies of cowardice for not having enlisted in the War, and of treachery to Lyons. Menzies then formed a minority government

. When Page was deposed as Country Party leader a few months later, Menzies reformed the Coalition with Page's successor, Archie Cameron

.

– Menzies radio broadcast to the nation on 3 September 1939 informing Australia that the country was at war with Germany and her allies

.

In September 1939, Menzies found himself a wartime leader of a small nation of 7 million people that depended on Britain for defence against the looming threat of the Japanese Empire, with 100 million people, a very powerful military, and an aggressive foreign policy that looked south. He did his best to rally the country, but the bitter memories of the disillusionment which followed the First World War made this difficult. Added to this was the fact that Menzies had not served in that war, and that as Attorney-General and Deputy Prime Minister, Menzies had made an official visit to Germany in 1938, and like his Opposition at the time, supported Neville Chamberlain

's policy of Appeasement

. At the 1940 election, the UAP was nearly defeated, and Menzies' government survived only thanks to the support of two independent MPs, Arthur Coles

and Alex Wilson

. The Australian Labor Party

(ALP), under John Curtin

, refused Menzies' offer to form a war coalition, and also opposed using the Australian army for a European war, preferring to keep it at home to defend Australia. The ALP did agree to participate in the Advisory War Council

, however. Menzies sent the bulk of the army to help the British in the Middle East and Singapore, and told Winston Churchill

the Royal Navy should strengthen its Far Eastern forces.

In 1941 Menzies spent months in Britain discussing war strategy with Churchill and other leaders, while his position at home deteriorated. The Australian historian David Day

has suggested that Menzies hoped to replace Churchill as British Prime Minister, and that he had some support in Britain for this. Other Australian writers, such as Gerard Henderson

, have rejected this theory. When Menzies came home, he found he had lost all support, and was forced to resign as Prime Minister. However, the UAP was so bereft of leadership that it was forced to allow the Country Party leader, Arthur Fadden

, to become Prime Minister even though the Country Party was the junior partner in the Coalition. Menzies was very bitter about what he saw as this betrayal by his colleagues, and almost left politics. However, he was prevailed upon to remain UAP leader and Minister for Defence Co-ordination

in Fadden's government.

, Robert Menzies, 22 May 1942;

Fadden's government was defeated in Parliament later in 1941, and Labor formed a government under John Curtin. Menzies argued that he should become Leader of the Opposition, but most of his colleagues favoured Fadden. Menzies resigned the leadership in disgust and was succeeded by Billy Hughes

. However, Menzies remained an opposition frontbencher under Fadden.

In 1943 Curtin won a huge election victory. Hughes resigned as UAP leader, and Menzies returned to the leadership. Fadden yielded the post of Opposition Leader back to Menzies as well. During 1944 Menzies held a series of meetings at 'Ravenscraig' an old homestead in Aspley to discuss forming a new anti-Labor party to replace the moribund UAP. This was the Liberal Party, which was launched in early 1945 with Menzies as leader. But Labor was firmly entrenched in power and in 1946 Curtin's successor, Ben Chifley

, was comfortably re-elected. Comments that "we can't win with Menzies" began to circulate in the conservative press.

Over the next few years, however, the anti-communist atmosphere of the early Cold War

began to erode Labor's support. In 1947, Chifley announced that he intended to nationalise Australia's private banks, arousing intense middle-class opposition which Menzies successfully exploited. The 1949 coal strike

, engineered by the Communist Party

, also played into Menzies' hands. In the December 1949 election

, Menzies won power for the second time in a massive landslide. He picked up 48 seats in a House of Representatives that had been expanded to 121 members, while Labor picked up only four. The net 44-seat swing is still the largest defeat of a sitting government at the federal level in Australia. In 1950 Menzies was awarded the Legion of Merit

(Chief Commander) by U.S. President Harry S. Truman

for "exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services 1941–1944 and December 1949 – July 1950". Although Menzies had a comfortable majority in the House, the ALP-controlled Senate made life very difficult for him. In 1951 Menzies introduced legislation to ban the Communist Party, hoping that the Senate would reject it and give him an excuse for a double dissolution

Although Menzies had a comfortable majority in the House, the ALP-controlled Senate made life very difficult for him. In 1951 Menzies introduced legislation to ban the Communist Party, hoping that the Senate would reject it and give him an excuse for a double dissolution

election, but Labor let the bill pass. It was subsequently ruled unconstitutional

by the High Court

. But when the Senate rejected his banking bill, he called a double dissolution

. While he won a slightly reduced majority in the House (the Coalition suffered a five-seat swing), he won six seats in the Senate to win control of both chambers.

Later in 1951 Menzies decided to hold a referendum

on the question of changing the Constitution to permit the parliament to make laws in respect of Communists and Communism where he said this was necessary for the security of the Commonwealth. If passed, this would have given a government the power to introduce a bill proposing to ban the Communist Party (although whether it would have passed the Senate is an open question). The new Labor leader, Dr H. V. Evatt

, campaigned against the referendum on civil liberties grounds, and it was narrowly defeated. This was one of Menzies' few electoral miscalculations. He sent Australian troops to the Korean War

and maintained a close alliance with the United States.

Economic conditions, however, deteriorated, and Evatt was confident of winning the 1954 elections. Shortly before the elections, Menzies announced that a Soviet

diplomat in Australia Vladimir Petrov

, had defected, and that there was evidence of a Soviet spy ring in Australia, including members of Evatt's staff. Evatt felt compelled to state on the floor of Parliament that he'd personally written Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov

, who assured him there were no Soviet spy rings in Australia. This Cold War

scare enabled Menzies to win the election; although Labor won a majority of the two-party-preferred vote

, it came up eight seats short of toppling the Coalition. Evatt accused Menzies of arranging Petrov's defection, but this has since been disproved: he had simply taken advantage of it.

The aftermath of the 1954 election caused a split in the Labor Party, with several anti-Communist members from Victoria

defecting to form the Australian Labor Party (Anti-Communist)

. The new party directed its preferences to the Liberals, and Menzies was comfortably re-elected over Evatt in 1955. Menzies was reelected almost as easily in 1958, again with the help of preferences from what had become the Democratic Labor Party

. By this time the post-war economic recovery was in full swing, fuelled by massive immigration and the growth in housing and manufacturing that this produced. Prices for Australia's agricultural exports were also high, ensuring rising incomes.

Labor's new leader, Arthur Calwell

, gave Menzies a scare after an ill-judged squeeze on credit an effort to restrain inflation caused a rise in unemployment. At the 1961 election

Menzies was returned with a majority of only two seats. But Menzies was able to exploit Labor's divisions over the Cold War and the American alliance, and win an increased majority in the 1963 election.

An incident in which Calwell was photographed standing outside a South Canberra hotel while the ALP Federal Executive

(dubbed by Menzies the "36 faceless men") was determining policy also contributed to the 1963 victory. This was the first "television election," and Menzies, although nearly 70, proved a master of the new medium. Menzies' policy speech was televised on 12 November 1963, a method that "had never before been used in Australia". The effect of this form of political communication was studied by Colin Hughes

and John Western

, who published their findings in 1966. This was itself the first such detailed study in Australia.

In 1963, Menzies was appointed a Knight of the Order of the Thistle

(KT), the order being chosen in recognition of his Scottish heritage. He is the only Australian ever appointed to this order, although three British governors-general of Australia

(Lord Hopetoun

; Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson, later Lord Novar; and Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

) were members. He was the second of only two Australian prime ministers to be knighted during their term of office (the first prime minister Edmund Barton

was knighted during his term in 1902). In 1965, Menzies committed Australian troops to the Vietnam War

In 1965, Menzies committed Australian troops to the Vietnam War

, and also to reintroduce conscription

. These moves were initially popular, but later became a problem for his successors.

Despite his pragmatic acceptance of the new power balance in the Pacific after World War II and his strong support for the American alliance, he publicly professed continued admiration for links with Britain, exemplified by his admiration for Queen Elizabeth II, and famously described himself as "British to the bootstraps". Over the decade, Australia's ardour for Britain and the monarchy faded somewhat, but Menzies' had not. At a function attended by the Queen at Parliament House, Canberra, in 1963, Menzies quoted the Elizabethan

poet Thomas Ford

, "I did but see her passing by, and yet I love her till I die".

Menzies retired on Australia Day

Menzies retired on Australia Day

1966, ending 38 years as an elected official. To date, he is the last Australian Prime Minister to leave office on his own terms. He was succeeded as Liberal Party leader and Prime Minister by his former Treasurer, Harold Holt

. Although the coalition remained in power for almost another seven years (until the 1972 Federal election

), it did so under four different Prime Ministers.

On his retirement he became the thirteenth Chancellor of his old University of Melbourne, and remained the head of the University from March 1967 until March 1972. Much earlier in 1942, he had received the first honorary degree of Doctor of Laws of Melbourne University. His responsibility for the revival and growth of university life in Australia was widely acknowledged by the award of honorary degrees in the Universities of Queensland, Adelaide, Tasmania, New South Wales, and the Australian National University and by thirteen universities in Canada, the U.S.A. and Britain, including Oxford and Cambridge. Many learned institutions, including the Royal College of Surgeons

(Hon. FRCS) and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians

(Hon. FRACP), elected him to Honorary Fellowships, and the Australian Academy of Science

, for which he supported its establishment in 1954, made him a fellow (FAAS) in 1958.

In July 1966 the Queen appointed Menzies to the ancient office of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports

and Constable of Dover Castle

, taking official residence at Walmer Castle

during his annual visits to Britain. He toured the United States giving lectures, and he published two volumes of memoirs. At the end of 1966 Menzies took up a scholar-in-residence position at the University of Virginia

. Menzies encountered some public tribulation in retirement; however, when he suffered strokes in 1968 and 1971, he faded from public view.

Menzies died from a heart attack in Melbourne in 1978 and was accorded a state funeral, held in Scots' Church, Melbourne

, at which Prince Charles represented Queen Elizabeth II.

Menzies was Prime Minister for a total of 18 years, five months, and 12 days, by far the longest term of any Australian Prime Minister, and during his second term he dominated Australian politics as no one else has ever done. He managed to live down the failures of his first term in office, and to rebuild the conservative side of politics from the nadir it hit in 1943. Menzies also did much to develop higher education in Australia, and he also made the increasing development of Canberra

one of his big projects.

However, it can also be noted that while retaining government on each occasion, Menzies lost the two-party-preferred vote

in 1940

, 1954

, and 1961

.

He was the only Australian Prime Minister to recommend the appointment of four governors-general (Sir William Slim

, and Lords Dunrossil

, De L'Isle

, and Casey

). Only two other Prime Ministers have ever chosen more than one governor-general. (Malcolm Fraser

chose Sir Zelman Cowen

and Sir Ninian Stephen

; and John Howard

chose Peter Hollingworth

and Michael Jeffery

.)

The Menzies era saw Australia

become an increasingly affluent society, with average weekly earnings in 1965 50% higher in real terms than in 1945. The increased prosperity enjoyed by most Australians during this period was accompanied by a general increase in leisure time, with the five-day workweek becoming the norm by the mid-Sixties, together with three weeks of paid annual leave.

Critics say that Menzies' success was mainly due to the good luck of the long post-war boom and his manipulation of the anti-communist fears of the Cold War years, both of which he exploited with great skill. He was also crucially aided by the crippling dissent within the Labor Party in the 1950s and especially by the ALP split of 1954.

Several books have been filled with anecdotes about him and with his many witty remarks. While he was speaking in Williamstown, Victoria

, in 1954, a heckler shouted, "I wouldn’t vote for you if you were the Archangel Gabriel

" to which Menzies coolly replied "If I were the Archangel Gabriel, I’m afraid you wouldn't be in my constituency."

Planning for an official biography of Menzies began soon after his death, but it was long delayed by Dame Pattie Menzies' protection of her husband's reputation and her refusal to co-operate with the appointed biographer, Frances McNicoll. In 1991, the Menzies family appointed Professor A.W. Martin to write a biography, which appeared in two volumes, in 1993 and 1999.

The National Museum of Australia

in Canberra holds a significant collection of memorabilia relating to Robert Menzies, including a range of medals and civil awards received by Sir Robert such as his Jubilee and Coronation medals, Order of Australia, Companion of Honour and US Legion of Merit. There are also a number of special presentation items including a walking stick, cigar boxes, silver gravy boats from the Kooyong electorate and a silver inkstand presented by Queen Elizabeth II.

and titles Menzies Menzies held held from birth until death, in chronological order:

Prime Minister of Australia

The Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Australia is the highest minister of the Crown, leader of the Cabinet and Head of Her Majesty's Australian Government, holding office on commission from the Governor-General of Australia. The office of Prime Minister is, in practice, the most powerful...

.

His first term as Prime Minister commenced in 1939, after the death in office of the United Australia Party

United Australia Party

The United Australia Party was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. It was the political successor to the Nationalist Party of Australia and predecessor to the Liberal Party of Australia...

leader Joseph Lyons

Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons, CH was an Australian politician. He was Labor Premier of Tasmania from 1923 to 1928 and a Minister in the James Scullin government from 1929 until his resignation from the Labor Party in March 1931...

and a short-term interim premiership by Sir Earle Page

Earle Page

Sir Earle Christmas Grafton Page, GCMG, CH was the 11th Prime Minister of Australia, and is to date the second-longest serving federal parliamentarian in Australian history, with 41 years, 361 days in Parliament.-Early life:...

. His party narrowly won the 1940 election

Australian federal election, 1940

Federal elections were held in Australia on 21 September 1940. All 74 seats in the House of Representatives, and 19 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election...

, which produced a hung parliament

Hung parliament

In a two-party parliamentary system of government, a hung parliament occurs when neither major political party has an absolute majority of seats in the parliament . It is also less commonly known as a balanced parliament or a legislature under no overall control...

, with the support of independent MPs in the House. A year later, his government was brought down by those same MPs crossing the floor

Crossing the floor

In politics, crossing the floor has two meanings referring to a change of allegiance in a Westminster system parliament.The term originates from the British House of Commons, which is configured with the Government and Opposition facing each other on rows of benches...

. He spent eight years in opposition, during which he founded the Liberal Party of Australia

Liberal Party of Australia

The Liberal Party of Australia is an Australian political party.Founded a year after the 1943 federal election to replace the United Australia Party, the centre-right Liberal Party typically competes with the centre-left Australian Labor Party for political office...

. He again became Prime Minister at the 1949 election

Australian federal election, 1949

Federal elections were held in Australia on 10 December 1949. All 121 seats in the House of Representatives, and 42 of the 60 seats in the Senate were up for election, where the single transferable vote was introduced...

, and he then dominated Australian politics until his retirement in 1966.

Menzies was renowned as a brilliant speaker, both on the floor of Parliament and on the hustings; his speech "The Forgotten People

The forgotten people

"The Forgotten People" is the name given to a 1942 speech delivered by Robert Menzies, an Australian politician who went on to become the longest-serving Prime Minister of Australia.-Overview:...

" is an example of his oratorical skills. Throughout his life and career, Menzies held strong beliefs in the Monarchy and in traditional ties with Britain. In 1963 Menzies was invested as the first and only Australian Knight of the Order of the Thistle

Order of the Thistle

The Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle is an order of chivalry associated with Scotland. The current version of the Order was founded in 1687 by King James VII of Scotland who asserted that he was reviving an earlier Order...

. Menzies is regarded highly in Prime Ministerial opinion polls and is very highly regarded in Australian society for his tenures as Prime Minister.

Early life

Robert Gordon Menzies was born to James Menzies and Kate Menzies (née Sampson) in JeparitJeparit, Victoria

Jeparit is situated on the Wimmera River in Western Victoria, Australia, 370 kilometres north west of Melbourne. At the 2006 census Jeparit had a population of 582.-History:...

, a town in the Wimmera

Wimmera

The Wimmera is a region in the west of the Australian state of Victoria.It covers the dryland farming area south of the range of Mallee scrub, east of the South Australia border and north of the Great Dividing Range...

region of western Victoria

Victoria (Australia)

Victoria is the second most populous state in Australia. Geographically the smallest mainland state, Victoria is bordered by New South Wales, South Australia, and Tasmania on Boundary Islet to the north, west and south respectively....

, on 20 December 1894. His father James was a storekeeper, the son of Scottish

Scottish people

The Scottish people , or Scots, are a nation and ethnic group native to Scotland. Historically they emerged from an amalgamation of the Picts and Gaels, incorporating neighbouring Britons to the south as well as invading Germanic peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons and the Norse.In modern use,...

crofters who had immigrated to Australia in the mid-1850s in the wake of the Victorian gold rush

Victorian gold rush

The Victorian gold rush was a period in the history of Victoria, Australia approximately between 1851 and the late 1860s. In 10 years the Australian population nearly tripled.- Overview :During this era Victoria dominated the world's gold output...

. His maternal grandfather, John Sampson, was a Cornish

Cornish people

The Cornish are a people associated with Cornwall, a county and Duchy in the south-west of the United Kingdom that is seen in some respects as distinct from England, having more in common with the other Celtic parts of the United Kingdom such as Wales, as well as with other Celtic nations in Europe...

miner from Penzance

Penzance

Penzance is a town, civil parish, and port in Cornwall, England, in the United Kingdom. It is the most westerly major town in Cornwall and is approximately 75 miles west of Plymouth and 300 miles west-southwest of London...

who also came to seek his fortune on the goldfields, in Ballarat

Ballarat, Victoria

Ballarat is a city in the state of Victoria, Australia, approximately west-north-west of the state capital Melbourne situated on the lower plains of the Great Dividing Range and the Yarrowee River catchment. It is the largest inland centre and third most populous city in the state and the fifth...

. Menzies was proud of his mother's origin, Cornish author A.L. Rowse tells us that 'When Menzies visited us [at All Souls College, Oxford] he told me that he was a Cornish Sampson on his mother's side.' His father and one of his uncles had been members of the Victorian Parliament, while another uncle had represented Wimmera in the House of Representatives. He was proud of his Highland

Scottish Highlands

The Highlands is an historic region of Scotland. The area is sometimes referred to as the "Scottish Highlands". It was culturally distinguishable from the Lowlands from the later Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Scots replaced Scottish Gaelic throughout most of the Lowlands...

ancestry his enduring nickname, Ming, came from ˈmɪŋəs, the Scots

Scots language

Scots is the Germanic language variety spoken in Lowland Scotland and parts of Ulster . It is sometimes called Lowland Scots to distinguish it from Scottish Gaelic, the Celtic language variety spoken in most of the western Highlands and in the Hebrides.Since there are no universally accepted...

– and his own preferred – pronunciation of Menzies. His middle name, Gordon, was given to him in honour and memory of Charles George Gordon

Charles George Gordon

Major-General Charles George Gordon, CB , known as "Chinese" Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British army officer and administrator....

, a British army officer killed in Khartoum

Khartoum

Khartoum is the capital and largest city of Sudan and of Khartoum State. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile flowing north from Lake Victoria, and the Blue Nile flowing west from Ethiopia. The location where the two Niles meet is known as "al-Mogran"...

in 1885.

Menzies was first educated at a one-room school, then later at private schools in Ballarat and Melbourne (Wesley College

Wesley College, Melbourne

Wesley College, Melbourne is an independent, co-educational, Christian day school in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Established in 1866, the college is a school of the Uniting Church in Australia. Wesley is the largest school in Australia by enrolment, with 3,511 students and 564 full-time staff...

), and studied law at the University of Melbourne

University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne is a public university located in Melbourne, Victoria. Founded in 1853, it is the second oldest university in Australia and the oldest in Victoria...

graduating in 1916.

When World War I began, Menzies was 19 years old and held a commission in the university's militia unit. Menzies resigned his commission at the very time others of his age and class clamoured to be allowed to enlist. It was later stated that, since the family had made enough of a sacrifice to the war with the enlistment of two of three eligible brothers, Menzies should stay to finish his studies. Menzies himself never explained the reason why he chose not to enlist. Subsequently he was prominent in undergraduate activities and won academic prizes and declared himself to be a patriotic supporter of the war and conscription. Menzies was admitted to the Victorian Bar and to the High Court of Australia in 1918 and soon became one of Melbourne's leading lawyers after establishing his own practice. In 1920 he married Pattie Leckie

Pattie Menzies

Dame Pattie Maie Menzies GBE was the wife of Australia’s longest-serving Prime Minister, Sir Robert Menzies.-Biography:...

, the daughter of federal Nationalist

Nationalist Party of Australia

The Nationalist Party of Australia was an Australian political party. It was formed on 17 February 1917 from a merger between the conservative Commonwealth Liberal Party and the National Labor Party, the name given to the pro-conscription defectors from the Australian Labor Party led by Prime...

, and later Liberal, MP, John Leckie

John Leckie (Australian politician)

John William Leckie was an Australian farmer turned politician.Leckie was born at Alexandra, Victoria and educated at Scotch College, Melbourne. He played Australian rules football for Fitzroy Football Club in 1895...

.

Rise to power

In 1928, Menzies gave up his law practice to enter state parliament as a member of the Victorian Legislative CouncilVictorian Legislative Council

The Victorian Legislative Council, is the upper of the two houses of the Parliament of Victoria, Australia; the lower house being the Legislative Assembly. Both houses sit in Parliament House in Spring Street, Melbourne. The Legislative Council serves as a house of review, in a similar fashion to...

from East Yarra Province

East Yarra Province

East Yarra Province was an electorate of the Victorian Legislative Council until 2006. It was abolished from the 2006 state election in the wake of the Bracks Labor government's reform of the Legislative Council.-Members for East Yarra Province:...

, representing the Nationalist Party of Australia

Nationalist Party of Australia

The Nationalist Party of Australia was an Australian political party. It was formed on 17 February 1917 from a merger between the conservative Commonwealth Liberal Party and the National Labor Party, the name given to the pro-conscription defectors from the Australian Labor Party led by Prime...

. His candidacy was nearly defeated when a group of ex-servicemen attacked him in the press for not having enlisted, but he survived this crisis. The following year he shifted to the Legislative Assembly

Victorian Legislative Assembly

The Victorian Legislative Assembly is the lower house of the Parliament of Victoria in Australia. Together with the Victorian Legislative Council, the upper house, it sits in Parliament House in the state capital, Melbourne.-History:...

as the member for Nunawading

Electoral district of Nunawading

The electoral district of Nunawading was an electoral district of the Legislative Assembly in the Australian state of Victoria.-Members for Nunawading:...

. Before the election, he founded the Young Nationalists as his party's youth wing and served as its first president. He was Deputy Premier of Victoria

Deputy Premier of Victoria

The Deputy Premier of Victoria is the second-most senior officer in the Government of Victoria. The Deputy Premiership has been a ministerial portfolio since , and the Deputy Premier is appointed by the Governor on the advice of the Premier....

from May 1932 until July 1934.

Menzies transferred to federal politics in 1934, representing the United Australia Party

United Australia Party

The United Australia Party was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. It was the political successor to the Nationalist Party of Australia and predecessor to the Liberal Party of Australia...

(UAP—the Nationalists had merged with other non-Labor groups to form the UAP during his tenure as a state parliamentarian) in the upper-class Melbourne electorate of Kooyong

Division of Kooyong

The Division of Kooyong is an Australian Electoral Division in the state of Victoria. It is located in the inner eastern suburbs of Melbourne, and encompasses the suburbs of Kew, Hawthorn, Hawthorn East, Balwyn, Canterbury, Camberwell and Surrey Hills. The Division was proclaimed in 1900, and was...

. He was immediately appointed Attorney-General and Minister for Industry in the Lyons government. In 1937 he was appointed a Privy Councillor

Privy Council of the United Kingdom

Her Majesty's Most Honourable Privy Council, usually known simply as the Privy Council, is a formal body of advisers to the Sovereign in the United Kingdom...

.

In late 1934 and early 1935 Menzies unsuccessfully prosecuted the Lyons government's case for the attempted exclusion from Australia of Egon Kisch

Egon Erwin Kisch

Egon Erwin Kisch was a Czechoslovak writer and journalist, who wrote in German. Known as the The raging reporter from Prague, Kisch was noted for his development of literary reportage and his opposition to Adolf Hitler's Nazi regime.- Biography :Kisch was born into a wealthy, German-speaking...

, a Czech Jewish communist. Because of this, some accused Menzies of being pro-Nazi, whilst others saw it as an early example of his strong opposition to communism. Following the outbreak of World War II Menzies found it necessary to distance himself from the controversy by claiming Interior Minister Thomas Paterson

Thomas Paterson

Thomas Paterson was an Australian farmer and politician.Paterson was born in Aston, near Birmingham, England and educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham and Ayr Grammar School. He became a shoe salesman in 1897 and later a branch manager, but resigned in 1908 to study farming...

was responsible since he made the initial order to exclude Kisch.

Animosity developed between Earle Page

Earle Page

Sir Earle Christmas Grafton Page, GCMG, CH was the 11th Prime Minister of Australia, and is to date the second-longest serving federal parliamentarian in Australian history, with 41 years, 361 days in Parliament.-Early life:...

and Menzies which was aggravated when Page became Acting Prime Minister during Lyons' illness after October 1938. Menzies and Page attacked each other publicly. He later became deputy leader of the UAP. His supporters said he was Lyons's natural successor; his critics accused Menzies of wanting to push Lyons out, a charge he denied. In 1938 his enemies ridiculed him as "Pig Iron Bob", the result of his industrial battle with waterside workers who refused to load scrap iron being sold to Imperial Japan. In 1939, however, he resigned from the Cabinet in protest at postponement of the national insurance scheme. With Lyons' sudden death on 7 April 1939, Page became acting Prime Minister until the UAP could elect a leader.

First term as Prime Minister

Minority government

A minority government or a minority cabinet is a cabinet of a parliamentary system formed when a political party or coalition of parties does not have a majority of overall seats in the parliament but is sworn into government to break a Hung Parliament election result. It is also known as a...

. When Page was deposed as Country Party leader a few months later, Menzies reformed the Coalition with Page's successor, Archie Cameron

Archie Cameron

Archie Galbraith Cameron , was an Australian politician. He was Leader of the Country Party 1939-40, and Speaker of the House of Representatives 1950-56.-Biography:...

.

– Menzies radio broadcast to the nation on 3 September 1939 informing Australia that the country was at war with Germany and her allies

Axis Powers

The Axis powers , also known as the Axis alliance, Axis nations, Axis countries, or just the Axis, was an alignment of great powers during the mid-20th century that fought World War II against the Allies. It began in 1936 with treaties of friendship between Germany and Italy and between Germany and...

.

In September 1939, Menzies found himself a wartime leader of a small nation of 7 million people that depended on Britain for defence against the looming threat of the Japanese Empire, with 100 million people, a very powerful military, and an aggressive foreign policy that looked south. He did his best to rally the country, but the bitter memories of the disillusionment which followed the First World War made this difficult. Added to this was the fact that Menzies had not served in that war, and that as Attorney-General and Deputy Prime Minister, Menzies had made an official visit to Germany in 1938, and like his Opposition at the time, supported Neville Chamberlain

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain FRS was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. Chamberlain is best known for his appeasement foreign policy, and in particular for his signing of the Munich Agreement in 1938, conceding the...

's policy of Appeasement

Appeasement

The term appeasement is commonly understood to refer to a diplomatic policy aimed at avoiding war by making concessions to another power. Historian Paul Kennedy defines it as "the policy of settling international quarrels by admitting and satisfying grievances through rational negotiation and...

. At the 1940 election, the UAP was nearly defeated, and Menzies' government survived only thanks to the support of two independent MPs, Arthur Coles

Arthur Coles

Sir Arthur William Coles was a prominent Australian businessman and philanthropist.With his brothers Coles founded the Coles Variety Stores in the 1920s, which were to become one of the two largest supermarket chains in Australia now known as Coles Group...

and Alex Wilson

Alexander Wilson (Australian politician)

Alexander Wilson was an Australian wheat farmer and politician.-Biography:Born in County Down, Ireland, he was educated at Belfast and migrated to Australia in 1908, becoming a farmer at Ultima, Victoria. He was prominent as a leader of Victorian wheatgrowers...

. The Australian Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

(ALP), under John Curtin

John Curtin

John Joseph Curtin , Australian politician, served as the 14th Prime Minister of Australia. Labor under Curtin formed a minority government in 1941 after the crossbench consisting of two independent MPs crossed the floor in the House of Representatives, bringing down the Coalition minority...

, refused Menzies' offer to form a war coalition, and also opposed using the Australian army for a European war, preferring to keep it at home to defend Australia. The ALP did agree to participate in the Advisory War Council

Advisory War Council (Australia)

The Advisory War Council was an Australian Government body during World War II. The AWC was established on 28 October 1940 to draw all the major political parties in the Parliament of Australia into the process of making decisions on Australia's war effort and was disbanded on 30 August...

, however. Menzies sent the bulk of the army to help the British in the Middle East and Singapore, and told Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

the Royal Navy should strengthen its Far Eastern forces.

In 1941 Menzies spent months in Britain discussing war strategy with Churchill and other leaders, while his position at home deteriorated. The Australian historian David Day

David Day (historian)

David Day is an Australian historian.David Day graduated with first-class Honours in History and Political Science from the University of Melbourne and was awarded a PhD from the University of Cambridge...

has suggested that Menzies hoped to replace Churchill as British Prime Minister, and that he had some support in Britain for this. Other Australian writers, such as Gerard Henderson

Gerard Henderson

Gerard Henderson is a conservative Australian newspaper columnist for The Sydney Morning Herald.. He is also Executive Director of the Sydney Institute, a privately funded current affairs forum. His wife Anne Henderson is Deputy Director.-Education:Henderson attended the Jesuit Xavier College in...

, have rejected this theory. When Menzies came home, he found he had lost all support, and was forced to resign as Prime Minister. However, the UAP was so bereft of leadership that it was forced to allow the Country Party leader, Arthur Fadden

Arthur Fadden

Sir Arthur William Fadden, GCMG was an Australian politician and, briefly, the 13th Prime Minister of Australia.-Introduction:...

, to become Prime Minister even though the Country Party was the junior partner in the Coalition. Menzies was very bitter about what he saw as this betrayal by his colleagues, and almost left politics. However, he was prevailed upon to remain UAP leader and Minister for Defence Co-ordination

Minister for Defence (Australia)

The Minister for Defence of Australia administers his portfolio through the Australian Defence Organisation, which comprises the Department of Defence and the Australian Defence Force. Stephen Smith is the current Minister.-Ministers for Defence:...

in Fadden's government.

Return to power

Extract; The Forgotten PeopleThe forgotten people

"The Forgotten People" is the name given to a 1942 speech delivered by Robert Menzies, an Australian politician who went on to become the longest-serving Prime Minister of Australia.-Overview:...

, Robert Menzies, 22 May 1942;

Fadden's government was defeated in Parliament later in 1941, and Labor formed a government under John Curtin. Menzies argued that he should become Leader of the Opposition, but most of his colleagues favoured Fadden. Menzies resigned the leadership in disgust and was succeeded by Billy Hughes

Billy Hughes

William Morris "Billy" Hughes, CH, KC, MHR , Australian politician, was the seventh Prime Minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923....

. However, Menzies remained an opposition frontbencher under Fadden.

In 1943 Curtin won a huge election victory. Hughes resigned as UAP leader, and Menzies returned to the leadership. Fadden yielded the post of Opposition Leader back to Menzies as well. During 1944 Menzies held a series of meetings at 'Ravenscraig' an old homestead in Aspley to discuss forming a new anti-Labor party to replace the moribund UAP. This was the Liberal Party, which was launched in early 1945 with Menzies as leader. But Labor was firmly entrenched in power and in 1946 Curtin's successor, Ben Chifley

Ben Chifley

Joseph Benedict Chifley , Australian politician, was the 16th Prime Minister of Australia. He took over the Australian Labor Party leadership and Prime Ministership after the death of John Curtin in 1945, and went on to retain government at the 1946 election, before being defeated at the 1949...

, was comfortably re-elected. Comments that "we can't win with Menzies" began to circulate in the conservative press.

Over the next few years, however, the anti-communist atmosphere of the early Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

began to erode Labor's support. In 1947, Chifley announced that he intended to nationalise Australia's private banks, arousing intense middle-class opposition which Menzies successfully exploited. The 1949 coal strike

1949 Australian coal strike

The 1949 Australian coal strike is the first time that Australian military forces were used during peacetime to break a Trade union strike. The strike by 23,000 coal miners lasted for seven weeks, from 27 June 1949 to 15 August 1949, with troops being sent in by the Ben Chifley Federal Labor...

, engineered by the Communist Party

Communist Party of Australia

The Communist Party of Australia was founded in 1920 and dissolved in 1991; it was succeeded by the Socialist Party of Australia, which then renamed itself, becoming the current Communist Party of Australia. The CPA achieved its greatest political strength in the 1940s and faced an attempted...

, also played into Menzies' hands. In the December 1949 election

Australian federal election, 1949

Federal elections were held in Australia on 10 December 1949. All 121 seats in the House of Representatives, and 42 of the 60 seats in the Senate were up for election, where the single transferable vote was introduced...

, Menzies won power for the second time in a massive landslide. He picked up 48 seats in a House of Representatives that had been expanded to 121 members, while Labor picked up only four. The net 44-seat swing is still the largest defeat of a sitting government at the federal level in Australia. In 1950 Menzies was awarded the Legion of Merit

Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit is a military decoration of the United States armed forces that is awarded for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements...

(Chief Commander) by U.S. President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

for "exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services 1941–1944 and December 1949 – July 1950".

Double dissolution

A double dissolution is a procedure permitted under the Australian Constitution to resolve deadlocks between the House of Representatives and the Senate....

election, but Labor let the bill pass. It was subsequently ruled unconstitutional

Australian Communist Party v Commonwealth

Australian Communist Party v The Commonwealth 83 CLR 1, also known as the Communist Party Case, was a legal case in the High Court of Australia described as "undoubtedly one of the High Court's most important decisions."- Background :...

by the High Court

High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the supreme court in the Australian court hierarchy and the final court of appeal in Australia. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction, has the power of judicial review over laws passed by the Parliament of Australia and the parliaments of the States, and...

. But when the Senate rejected his banking bill, he called a double dissolution

Australian federal election, 1951

Federal elections were held in Australia on 28 April 1951. All 121 seats in the House of Representatives, and all 60 seats in the Senate were up for election, due to a double dissolution called after the Senate rejected the Commonwealth Bank Bill...

. While he won a slightly reduced majority in the House (the Coalition suffered a five-seat swing), he won six seats in the Senate to win control of both chambers.

Later in 1951 Menzies decided to hold a referendum

Australian referendum, 1951

The 1951 Australian Referendum was held on 22 September 1951 and sought approval for the federal government to ban the Communist Party of Australia. It was not carried.-Background:...

on the question of changing the Constitution to permit the parliament to make laws in respect of Communists and Communism where he said this was necessary for the security of the Commonwealth. If passed, this would have given a government the power to introduce a bill proposing to ban the Communist Party (although whether it would have passed the Senate is an open question). The new Labor leader, Dr H. V. Evatt

H. V. Evatt

Herbert Vere Evatt, QC KStJ , was an Australian jurist, politician and writer. He was President of the United Nations General Assembly in 1948–49 and helped draft the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights...

, campaigned against the referendum on civil liberties grounds, and it was narrowly defeated. This was one of Menzies' few electoral miscalculations. He sent Australian troops to the Korean War

Korean War

The Korean War was a conventional war between South Korea, supported by the United Nations, and North Korea, supported by the People's Republic of China , with military material aid from the Soviet Union...

and maintained a close alliance with the United States.

Economic conditions, however, deteriorated, and Evatt was confident of winning the 1954 elections. Shortly before the elections, Menzies announced that a Soviet

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

diplomat in Australia Vladimir Petrov

Vladimir Mikhaylovich Petrov (diplomat)

Vladimir Mikhaylovich Petrov was a member of the Soviet Union's clandestine services who became famous in 1954 for his defection to Australia.-Early life:...

, had defected, and that there was evidence of a Soviet spy ring in Australia, including members of Evatt's staff. Evatt felt compelled to state on the floor of Parliament that he'd personally written Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov was a Soviet politician and diplomat, an Old Bolshevik and a leading figure in the Soviet government from the 1920s, when he rose to power as a protégé of Joseph Stalin, to 1957, when he was dismissed from the Presidium of the Central Committee by Nikita Khrushchev...

, who assured him there were no Soviet spy rings in Australia. This Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

scare enabled Menzies to win the election; although Labor won a majority of the two-party-preferred vote

Two-party-preferred vote

In politics, the two-party-preferred vote , or two-candidate-preferred vote , in an election or opinion poll uses preferential voting to express the electoral result after the distribution of preferences...

, it came up eight seats short of toppling the Coalition. Evatt accused Menzies of arranging Petrov's defection, but this has since been disproved: he had simply taken advantage of it.

The aftermath of the 1954 election caused a split in the Labor Party, with several anti-Communist members from Victoria

Victoria (Australia)

Victoria is the second most populous state in Australia. Geographically the smallest mainland state, Victoria is bordered by New South Wales, South Australia, and Tasmania on Boundary Islet to the north, west and south respectively....

defecting to form the Australian Labor Party (Anti-Communist)

Australian Labor Party (Anti-Communist)

The Australian Labor Party was the name initially used by the right-wing group which split away from the Australian Labor Party in 1955, and which later became the Democratic Labor Party in 1957....

. The new party directed its preferences to the Liberals, and Menzies was comfortably re-elected over Evatt in 1955. Menzies was reelected almost as easily in 1958, again with the help of preferences from what had become the Democratic Labor Party

Democratic Labor Party (historical)

The Democratic Labor Party was an Australian political party that existed from 1955 until 1978.-History:The DLP was formed as a result of a split in the Australian Labor Party that began in 1954. The split was between the party's national leadership, under the then party leader Dr H.V...

. By this time the post-war economic recovery was in full swing, fuelled by massive immigration and the growth in housing and manufacturing that this produced. Prices for Australia's agricultural exports were also high, ensuring rising incomes.

Labor's new leader, Arthur Calwell

Arthur Calwell

Arthur Augustus Calwell Australian politician, was a member of the Australian House of Representatives for 32 years from 1940 to 1972, Immigration Minister in the government of Ben Chifley from 1945 to 1949 and Leader of the Australian Labor Party from 1960 to 1967.-Early life:Calwell was born in...

, gave Menzies a scare after an ill-judged squeeze on credit an effort to restrain inflation caused a rise in unemployment. At the 1961 election

Australian federal election, 1961

Federal elections were held in Australia on 9 December 1961. All 122 seats in the House of Representatives, and 31 of the 60 seats in the Senate were up for election...

Menzies was returned with a majority of only two seats. But Menzies was able to exploit Labor's divisions over the Cold War and the American alliance, and win an increased majority in the 1963 election.

An incident in which Calwell was photographed standing outside a South Canberra hotel while the ALP Federal Executive

Australian Labor Party National Executive

The National Executive is the highest elected body of the Australian Labor Party, one of the major political parties in Australia. The Executive is elected by the party's National Conference, held every three years, and represents the party's state and territory branches. Many of its members are...

(dubbed by Menzies the "36 faceless men") was determining policy also contributed to the 1963 victory. This was the first "television election," and Menzies, although nearly 70, proved a master of the new medium. Menzies' policy speech was televised on 12 November 1963, a method that "had never before been used in Australia". The effect of this form of political communication was studied by Colin Hughes

Colin Hughes

Colin Anfield Hughes is an Australian academic specializing in electoral politics and government.He received his B.A. and M.A. degrees from Columbia University and his Ph.D from the London School of Economics. In 1966, along with John S...

and John Western

John Western

John Stuart Western was an Australian academic and author.He received his B.A. and M.A. and his Diploma of Social Studies from the University of Melbourne, and his Ph.D from Columbia University in 1959. In 1966, along with Colin A...

, who published their findings in 1966. This was itself the first such detailed study in Australia.

In 1963, Menzies was appointed a Knight of the Order of the Thistle

Order of the Thistle

The Most Ancient and Most Noble Order of the Thistle is an order of chivalry associated with Scotland. The current version of the Order was founded in 1687 by King James VII of Scotland who asserted that he was reviving an earlier Order...

(KT), the order being chosen in recognition of his Scottish heritage. He is the only Australian ever appointed to this order, although three British governors-general of Australia

Governor-General of Australia

The Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia is the representative in Australia at federal/national level of the Australian monarch . He or she exercises the supreme executive power of the Commonwealth...

(Lord Hopetoun

John Hope, 1st Marquess of Linlithgow

John Adrian Louis Hope, 1st Marquess of Linlithgow KT, GCMG, GCVO, PC , also known as Viscount Aithrie before 1873 and as The 7th Earl of Hopetoun between 1873 and 1902, was a Scottish aristocrat, politician and colonial administrator. He is best known for his brief and controversial tenure as the...

; Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson, later Lord Novar; and Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

The Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester was a soldier and member of the British Royal Family, the third son of George V of the United Kingdom and Queen Mary....

) were members. He was the second of only two Australian prime ministers to be knighted during their term of office (the first prime minister Edmund Barton

Edmund Barton

Sir Edmund Barton, GCMG, KC , Australian politician and judge, was the first Prime Minister of Australia and a founding justice of the High Court of Australia....

was knighted during his term in 1902).

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War was a Cold War-era military conflict that occurred in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. This war followed the First Indochina War and was fought between North Vietnam, supported by its communist allies, and the government of...

, and also to reintroduce conscription

Conscription

Conscription is the compulsory enlistment of people in some sort of national service, most often military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and continues in some countries to the present day under various names...

. These moves were initially popular, but later became a problem for his successors.

Despite his pragmatic acceptance of the new power balance in the Pacific after World War II and his strong support for the American alliance, he publicly professed continued admiration for links with Britain, exemplified by his admiration for Queen Elizabeth II, and famously described himself as "British to the bootstraps". Over the decade, Australia's ardour for Britain and the monarchy faded somewhat, but Menzies' had not. At a function attended by the Queen at Parliament House, Canberra, in 1963, Menzies quoted the Elizabethan

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I was queen regnant of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death. Sometimes called The Virgin Queen, Gloriana, or Good Queen Bess, Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudor dynasty...

poet Thomas Ford

Thomas Ford (composer)

Thomas Ford was an English composer, lutenist, viol player and poet.He was attached to the court of Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, son of James I, who died in 1612...

, "I did but see her passing by, and yet I love her till I die".

Retirement and legacy

Australia Day

Australia Day is the official national day of Australia...

1966, ending 38 years as an elected official. To date, he is the last Australian Prime Minister to leave office on his own terms. He was succeeded as Liberal Party leader and Prime Minister by his former Treasurer, Harold Holt

Harold Holt

Harold Edward Holt, CH was an Australian politician and the 17th Prime Minister of Australia.His term as Prime Minister was brought to an early and dramatic end in December 1967 when he disappeared while swimming at Cheviot Beach near Portsea, Victoria, and was presumed drowned.Holt spent 32 years...

. Although the coalition remained in power for almost another seven years (until the 1972 Federal election

Australian federal election, 1972

Federal elections were held in Australia on 2 December 1972. All 125 seats in the House of Representatives were up for election. The Liberal Party of Australia had been in power since 1949, under Prime Minister of Australia William McMahon since March 1971 with coalition partner the Country Party...

), it did so under four different Prime Ministers.

On his retirement he became the thirteenth Chancellor of his old University of Melbourne, and remained the head of the University from March 1967 until March 1972. Much earlier in 1942, he had received the first honorary degree of Doctor of Laws of Melbourne University. His responsibility for the revival and growth of university life in Australia was widely acknowledged by the award of honorary degrees in the Universities of Queensland, Adelaide, Tasmania, New South Wales, and the Australian National University and by thirteen universities in Canada, the U.S.A. and Britain, including Oxford and Cambridge. Many learned institutions, including the Royal College of Surgeons

Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons

Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons is a professional qualification to practise as a surgeon in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland...

(Hon. FRCS) and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Royal Australasian College of Physicians

The Royal Australasian College of Physicians, or RACP, is the organisation responsible for training, educating, and representing over 9,000 physicians and paediatricians in Australia and New Zealand. It was founded in 1938....

(Hon. FRACP), elected him to Honorary Fellowships, and the Australian Academy of Science

Australian Academy of Science

The Australian Academy of Science was founded in 1954 by a group of distinguished Australians, including Australian Fellows of the Royal Society of London. The first president was Sir Mark Oliphant. The Academy is modelled after the Royal Society and operates under a Royal Charter; as such it is...

, for which he supported its establishment in 1954, made him a fellow (FAAS) in 1958.

In July 1966 the Queen appointed Menzies to the ancient office of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports

Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports

The Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports is a ceremonial official in the United Kingdom. The post dates from at least the 12th century but may be older. The Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports was originally in charge of the Cinque Ports, a group of five port towns on the southeast coast of England...

and Constable of Dover Castle

Dover Castle

Dover Castle is a medieval castle in the town of the same name in the English county of Kent. It was founded in the 12th century and has been described as the "Key to England" due to its defensive significance throughout history...

, taking official residence at Walmer Castle

Walmer Castle

Walmer Castle was built by Henry VIII in 1539–1540 as an artillery fortress to counter the threat of invasion from Catholic France and Spain. It was part of his programme to create a chain of coastal defences along England's coast known as the Device Forts or as Henrician Castles...

during his annual visits to Britain. He toured the United States giving lectures, and he published two volumes of memoirs. At the end of 1966 Menzies took up a scholar-in-residence position at the University of Virginia

University of Virginia

The University of Virginia is a public research university located in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States, founded by Thomas Jefferson...

. Menzies encountered some public tribulation in retirement; however, when he suffered strokes in 1968 and 1971, he faded from public view.

Menzies died from a heart attack in Melbourne in 1978 and was accorded a state funeral, held in Scots' Church, Melbourne

Scots' Church, Melbourne

The Scots' Church, a Presbyterian church in Melbourne, Australia, was the first Presbyterian Church to be built in the Port Phillip District . It is located in Collins Street and is a congregation of the Presbyterian Church of Australia...

, at which Prince Charles represented Queen Elizabeth II.

Menzies was Prime Minister for a total of 18 years, five months, and 12 days, by far the longest term of any Australian Prime Minister, and during his second term he dominated Australian politics as no one else has ever done. He managed to live down the failures of his first term in office, and to rebuild the conservative side of politics from the nadir it hit in 1943. Menzies also did much to develop higher education in Australia, and he also made the increasing development of Canberra

Canberra

Canberra is the capital city of Australia. With a population of over 345,000, it is Australia's largest inland city and the eighth-largest city overall. The city is located at the northern end of the Australian Capital Territory , south-west of Sydney, and north-east of Melbourne...

one of his big projects.

However, it can also be noted that while retaining government on each occasion, Menzies lost the two-party-preferred vote

Two-party-preferred vote

In politics, the two-party-preferred vote , or two-candidate-preferred vote , in an election or opinion poll uses preferential voting to express the electoral result after the distribution of preferences...

in 1940

Australian federal election, 1940

Federal elections were held in Australia on 21 September 1940. All 74 seats in the House of Representatives, and 19 of the 36 seats in the Senate were up for election...

, 1954

Australian federal election, 1954

Federal elections were held in Australia on 29 May 1954. All 121 seats in the House of Representatives were up for election, no Senate election took place...

, and 1961

Australian federal election, 1961

Federal elections were held in Australia on 9 December 1961. All 122 seats in the House of Representatives, and 31 of the 60 seats in the Senate were up for election...

.

He was the only Australian Prime Minister to recommend the appointment of four governors-general (Sir William Slim

William Slim, 1st Viscount Slim

Field Marshal William Joseph "Bill"'Slim, 1st Viscount Slim, KG, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE, DSO, MC, KStJ was a British military commander and the 13th Governor-General of Australia....

, and Lords Dunrossil

William Morrison, 1st Viscount Dunrossil

William Shepherd Morrison, 1st Viscount Dunrossil, GCMG, MC, KStJ, PC, QC , the 14th Governor-General of Australia, was born in Scotland and educated at George Watson's College and the University of Edinburgh. He joined the British Army in the First World War and served with an artillery regiment...

, De L'Isle

William Sidney, 1st Viscount De L'Isle

William Philip Sidney, 1st Viscount De L'Isle and 6th Baron De L'Isle and Dudley VC KG GCMG GCVO KStJ PC , was the 15th Governor-General of Australia and the final non-Australian to hold the office...

, and Casey

Richard Casey, Baron Casey

Richard Gardiner Casey, Baron Casey KG GCMG CH DSO MC KStJ PC was an Australian politician, diplomat and the 16th Governor-General of Australia.-Early life:...

). Only two other Prime Ministers have ever chosen more than one governor-general. (Malcolm Fraser

Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser AC, CH, GCL, PC is a former Australian Liberal Party politician who was the 22nd Prime Minister of Australia. He came to power in the 1975 election following the dismissal of the Whitlam Labor government, in which he played a key role...

chose Sir Zelman Cowen

Zelman Cowen

Sir Zelman Cowen, was the 19th Governor-General of Australia. He is currently the oldest living former Governor-General of Australia.-Early life:...

and Sir Ninian Stephen

Ninian Stephen

Sir Ninian Martin Stephen, is a retired politician and judge, who served as the 20th Governor-General of Australia and as a Justice in the High Court of Australia.-Early life:...

; and John Howard

John Howard

John Winston Howard AC, SSI, was the 25th Prime Minister of Australia, from 11 March 1996 to 3 December 2007. He was the second-longest serving Australian Prime Minister after Sir Robert Menzies....

chose Peter Hollingworth

Peter Hollingworth

Peter John Hollingworth AC, OBE is an Australian Anglican bishop. He served as the Archbishop of Brisbane for 11 years before becoming the 23rd Governor-General of Australia from 2001 until 2003....

and Michael Jeffery

Michael Jeffery

Major General Philip Michael Jeffery AC, CVO, MC was the 24th Governor-General of Australia , the first Australian career soldier to be appointed governor-general...

.)

The Menzies era saw Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

become an increasingly affluent society, with average weekly earnings in 1965 50% higher in real terms than in 1945. The increased prosperity enjoyed by most Australians during this period was accompanied by a general increase in leisure time, with the five-day workweek becoming the norm by the mid-Sixties, together with three weeks of paid annual leave.

Critics say that Menzies' success was mainly due to the good luck of the long post-war boom and his manipulation of the anti-communist fears of the Cold War years, both of which he exploited with great skill. He was also crucially aided by the crippling dissent within the Labor Party in the 1950s and especially by the ALP split of 1954.

Several books have been filled with anecdotes about him and with his many witty remarks. While he was speaking in Williamstown, Victoria

Williamstown, Victoria

Williamstown is a suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 8 km south-west from Melbourne's central business district. Its Local Government Area is the City of Hobsons Bay. At the 2006 Census, Williamstown had a population of 12,733....

, in 1954, a heckler shouted, "I wouldn’t vote for you if you were the Archangel Gabriel

Gabriel

In Abrahamic religions, Gabriel is an Archangel who typically serves as a messenger to humans from God.He first appears in the Book of Daniel, delivering explanations of Daniel's visions. In the Gospel of Luke Gabriel foretells the births of both John the Baptist and of Jesus...

" to which Menzies coolly replied "If I were the Archangel Gabriel, I’m afraid you wouldn't be in my constituency."

Planning for an official biography of Menzies began soon after his death, but it was long delayed by Dame Pattie Menzies' protection of her husband's reputation and her refusal to co-operate with the appointed biographer, Frances McNicoll. In 1991, the Menzies family appointed Professor A.W. Martin to write a biography, which appeared in two volumes, in 1993 and 1999.

The National Museum of Australia

National Museum of Australia

The National Museum of Australia was formally established by the National Museum of Australia Act 1980. The National Museum preserves and interprets Australia's social history, exploring the key issues, people and events that have shaped the nation....

in Canberra holds a significant collection of memorabilia relating to Robert Menzies, including a range of medals and civil awards received by Sir Robert such as his Jubilee and Coronation medals, Order of Australia, Companion of Honour and US Legion of Merit. There are also a number of special presentation items including a walking stick, cigar boxes, silver gravy boats from the Kooyong electorate and a silver inkstand presented by Queen Elizabeth II.

Titles and honours

- On 1 January 1951 he was appointed to the Order of the Companions of HonourOrder of the Companions of HonourThe Order of the Companions of Honour is an order of the Commonwealth realms. It was founded by King George V in June 1917, as a reward for outstanding achievements in the arts, literature, music, science, politics, industry or religion....

(CH)

- On 29 August 1952, the University of SydneyUniversity of SydneyThe University of Sydney is a public university located in Sydney, New South Wales. The main campus spreads across the suburbs of Camperdown and Darlington on the southwestern outskirts of the Sydney CBD. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and Oceania...

conferred the degree of Doctor of Laws (honoris causa) on Menzies. He was likewise awarded an Honorary Doctor of Laws by the Universities of BristolUniversity of BristolThe University of Bristol is a public research university located in Bristol, United Kingdom. One of the so-called "red brick" universities, it received its Royal Charter in 1909, although its predecessor institution, University College, Bristol, had been in existence since 1876.The University is...

, Belfast, MelbourneUniversity of MelbourneThe University of Melbourne is a public university located in Melbourne, Victoria. Founded in 1853, it is the second oldest university in Australia and the oldest in Victoria...

, British ColumbiaUniversity of British ColumbiaThe University of British Columbia is a public research university. UBC’s two main campuses are situated in Vancouver and in Kelowna in the Okanagan Valley...

, McGillMcGill UniversityMohammed Fathy is a public research university located in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. The university bears the name of James McGill, a prominent Montreal merchant from Glasgow, Scotland, whose bequest formed the beginning of the university...

, MontrealUniversité de MontréalThe Université de Montréal is a public francophone research university in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. It comprises thirteen faculties, more than sixty departments and two affiliated schools: the École Polytechnique and HEC Montréal...

, Royal University of MaltaUniversity of MaltaThe University of Malta is the highest educational institution in Malta Europe and is one of the most respected universities in Europe. The University offers undergraduate Bachelor's Degrees, postgraduate Master's Degrees and postgraduate Doctorates .-History:The University of Malta was founded in...

, LavalUniversité LavalLaval University is the oldest centre of education in Canada and was the first institution in North America to offer higher education in French...

, QuebecUniversité du QuébecThe University of Quebec is a system of ten provincially-run public universities in Quebec, Canada. Its headquarters are in Quebec City. The university coordinates university programs for more than 87,000 students. It offers more than 300 programs...