Edmund Barton

Encyclopedia

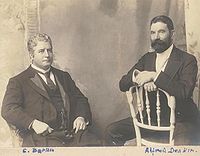

Sir Edmund Barton, GCMG

, KC

(18 January 1849 – 7 January 1920), Australian politician and judge, was the first Prime Minister of Australia

and a founding justice of the High Court of Australia

.

Barton's greatest contribution to Australian history was his management of the federation movement through the 1890s. Elected at the inaugural 1901 federal election, he led the Protectionist party and government with the support of the Australian Labor Party

. Barton resigned from the position of Prime Minister of Australia in 1903 and became a judge of Australia's High Court. He is one of only three Australian prime ministers who left the position at a time of their own choosing.

He was born in the suburb of Glebe

He was born in the suburb of Glebe

, the ninth child of English

parents William Barton, a stockbroker, and Mary Louise Barton. He was educated at Fort Street High School

and Sydney Grammar School

, where he was twice dux

and School Captain

and met his life-long friend and later fellow Justice of the High Court of Australia, Richard O'Connor. He graduated with first class honours and the University Medal

in classics from the University of Sydney

, where he also demonstrated considerable skill at batting (but not in fielding) in cricket

. Barton became a barrister in 1871. On a cricket trip to Newcastle

in 1870, he met Jane Mason Ross, whom he married in 1877.

In 1879, Barton umpired

a cricket game at Sydney Cricket Ground

between New South Wales

and an English touring side captained by Lord Harris

. After a controversial decision by Barton's colleague George Coulthard

against the home side, the crowd spilled onto the pitch and assaulted some of the English players, leading to international cricket's first riot

. The publicity that attended the young Barton's presence of mind in defusing that situation reputedly helped him take his first step towards becoming Australia's first prime minister, winning a state lower house seat later that year.

in the poll of the graduates of the University of Sydney

(who were required to wear gowns for the occasion), but was beaten by William Charles Windeyer

49 votes to 43. He was defeated again for the same seat in 1877, but won in August 1879. When it was abolished in 1880, he became the member for Wellington, from November 1880 to 1882, and East Sydney

, from November 1882 to January 1887. At this stage he considered it "almost unnecessary" to point out his support for free trade.

In 1882, he became Speaker of the Assembly and, in 1884, was elected President of the University of Sydney Union

. In 1887, Barton was appointed to the Legislative Council

at the instigation of Sir Henry Parkes

. In January 1889, he agreed to being appointed Attorney-General in George Dibbs

's Protectionist

government, despite his previous support for free trade. This government only lasted until March, when Parkes formed government again.

Edmund Barton was an early supporter of federation, which became a serious political agenda after Henry Parkes

Edmund Barton was an early supporter of federation, which became a serious political agenda after Henry Parkes

' Tenterfield Oration

, and was a delegate to the March 1891 National Australasian Convention. At the convention he made clear his support for the principle that "trade and intercourse … shall be absolutely free" in a federal Australia. He also advocated that, not just the lower house, but the upper house should be representative and that appeals to the Privy Council

should be abolished. He also took part in producing a draft constitution, which was substantially similar to the Australian Constitution

enacted in 1900.

Nevertheless, the protectionists were lukewarm supporters of federation and in June 1891, Barton resigned from the Council and stood for election to East Sydney and announced that "so long as Protection meant a Ministry of enemies to Federation, they would get no vote from him". He topped the poll and subsequently voted with Parkes, but refused to take a position in his minority government. After the Labor Party

withdrew support and the government fell in October 1891, Parkes persuaded him to take over the leadership of the Federal movement in New South Wales.

government and Barton agreed to be Attorney-General with the right of carry out private practice as a lawyer. His agreement was based on Dibbs agreeing to support federal resolutions in the coming parliamentary session. His attempt to draft the federal resolutions was delayed by a period as acting premier

, when he had to deal with the 1892 Broken Hill miners' strike

, and his carriage of a complex electoral reform bill. He introduced the federal resolutions into the House on 22 November 1892 but was unable to get them considered in committee.

Meanwhile, he began a campaign to spread support for federation to the people with meetings in Corowa

and Albury

in December 1892. Although he finally managed to get the federal resolutions considered in committee in October 1893, he then could not get them listed for debate by the House. In December, he and Richard O'Connor, the Minister for Justice, were questioned about their agreement to act as private lawyers against the government in Proudfoot v. the Railway Commissioners. While Barton resigned the brief, he lost a motion on the right of ministers to act in their professional capacity as lawyers in actions against the government, and immediately resigned as Attorney-General.

In July 1894, Barton stood for re-election for Randwick

(the multi-member electorate of East Sydney had been abolished) and lost. He did not stand for election in the 1895 elections, because of the need to support his large family during a period when parliamentarians were not paid. However, he continued to campaign for federation and during the period between January 1893 to February 1897, Barton addressed nearly 300 meetings in New South Wales, including in the Sydney suburb of Ashfield

where he declared that "For the first time in history, we have a nation for a continent and a continent for a nation". By March 1897 he was considered "the acknowledged leader of the federal movement in all Australia".

which developed a constitution for the proposed federation. Although Sir Samuel Griffith

wrote most of the text of the Constitution, Barton was the political leader who carried it through the Convention.

In May 1897 Barton was appointed for the second time to the Legislative Council on Reid's recommendations to take charge of the federation bill in the Upper House. This gave Reid's Attorney-General, John Henry Want

a free hand to oppose the bill. In September 1897 the convention met in Sydney to consider 286 proposed amendments from the colonies. It finalised its draft constitution in March 1898 and Barton went back to New South Wales to lead the campaign for a yes vote in the June referendum. Although it gained majority support, it only achieved 71,595 of the minimum 80,000 required to pass.

In July 1898 Barton resigned from the Upper House to stand against Reid for election to the Legislative Assembly, but narrowly lost. In September, he won a by-election for Hastings and Macleay

and was immediately elected leader of the opposition, which consisted of a mixture of pro-federation and anti-federation protectionists. In January 1899 Reid gained significant concessions from the other states and he joined Barton in campaigning for the second referendum in June 1899, with Barton campaigning all over the state. It passed 107,420 votes to 82,741.

In August 1899 when it became clear that the Labor Party

could be maneuvered into bringing down the Reid Government, Barton resigned as leader of the opposition, as he was unacceptable to Labor, and William Lyne

took his place. He refused an offer to become Attorney-General again. He resigned from Parliament in February 1900 so that he could travel to London

with Alfred Deakin

and Charles Kingston

to explain the federation bill to the British Government. The British Government was adamant in its opposition to the abolition of appeals to the Privy Council as incorporated in the draft constitution—eventually Barton agreed that constitutional (inter se

) matters would be finalised in the High Court

, but other matters could be appealed to the Privy Council.

Few people doubted that Barton, as the leading federalist in the oldest state, deserved to be the first Prime Minister of the new federation. However, since no federal Parliament had yet been established, the usual convention of appointing the leader of the largest party in the lower house could not apply. The newly arrived Governor-General

Few people doubted that Barton, as the leading federalist in the oldest state, deserved to be the first Prime Minister of the new federation. However, since no federal Parliament had yet been established, the usual convention of appointing the leader of the largest party in the lower house could not apply. The newly arrived Governor-General

, Lord Hopetoun

, instead invited Sir William Lyne

, the premier of New South Wales, to form a government.

Hopetoun's decision, known as the Hopetoun Blunder

, can be defended on grounds that Lyne had seniority. Still, Lyne's long massive opposition to federation until he changed his mind at the last minute caused him to be unacceptable to prominent federalists such as Deakin, who refused to serve under him. After tense negotiations, Barton was appointed Prime Minister and he and his ministry were sworn in on 1 January 1901.

Barton's government consisted of himself as Prime Minister and Minister for External Affairs, Alfred Deakin

as Attorney-General, Sir William Lyne as Minister for Home Affairs, Sir George Turner as Treasurer, Charles Kingston

as Minister for Trade and Customs, Sir James Dickson

as Minister for Defence, and Sir John Forrest

as Postmaster-General. Richard O'Connor was made Vice-President of the Executive Council and Elliott Lewis

was appointed Minister without Portfolio. Only ten days into the life of the government, Sir James Dickson died suddenly; he was replaced on 17 January as Minister for Defence by John Forrest, and James Drake

was brought into the ministry as Postmaster-General on 5 February.

The main task of Barton's ministry

was to organise the conduct of the first federal elections, which were held in March 1901. Barton was elected unopposed to the seat of Hunter

in the new Parliament (although he never lived in that electorate) and his Protectionist Party won enough seats to form a government with the support of the Labor Party

. All his ministers were elected, except for Elliott Lewis, who did not stand for election and was replaced by Sir Philip Fysh

.

An early piece of legislation of the Barton government was the Immigration Restriction Act 1901

, which put the White Australia policy

into law. The Labor Party required legislation to limit immigration from Asia as part of its agreement to support the government, although in fact Barton had promised the introduction of the White Australia Policy in his election campaign. Barton stated "The doctrine of the equality of man was never intended to apply to the equality of the Englishman and the Chinaman". One notable reform was the introduction of women's suffrage for federal elections in 1902.

Barton was a moderate conservative, and advanced liberals in his party disliked his relaxed attitude to political life. A large, handsome, jovial man, he was fond of long dinners and good wine and was given the nickname "Toby Tosspot" by the Bulletin

.

For much of 1902 Barton was in England

for the coronation of King Edward VII

. This trip was also used to negotiate the replacement of the naval agreements between the Australian colonies and the United Kingdom (under which Australia funded Royal Navy

protection from foreign naval threats) by an agreement between the Commonwealth and the United Kingdom. Deakin disliked this arrangement and discontinued it and moved to substantially expand Australia's own navy

in 1908.

In September 1903, Sir Edmund Barton left Parliament to become one of the founding justices of the High Court of Australia

. He was succeeded as Prime Minister by Deakin on 24 September.

Barton was one of only eight justices of the High Court to have served in the Parliament of Australia

Barton was one of only eight justices of the High Court to have served in the Parliament of Australia

prior to his appointment to the Court; the others were Richard O'Connor, Isaac Isaacs

, H. B. Higgins

, Edward McTiernan

, John Latham, Garfield Barwick

, and Lionel Murphy

. Barton was also one of six justices to have served in the Parliament of New South Wales

, along with O'Connor, Albert Piddington

, Adrian Knox

, McTiernan, and H. V. Evatt

.

On the bench Sir Edmund was considered a good and "scrupulously impartial" judge and adopted the same position of moderate conservatism he had taken in politics. Along with his colleagues Griffith

and O'Connor, he attempted to preserve the autonomy of the States and developed a doctrine of "implied immunity of instrumentalities", which prevented the States from taxing Commonwealth officers, and also prevented the Commonwealth from arbitrating industrial disputes in the States' railways. They also narrowly interpreted the Federal Government's powers in commercial and industrial matters.

After 1906, Sir Edmund increasingly clashed with Isaac Isaacs

and H. B. Higgins

, the two advanced liberals appointed to the court by Deakin. Like Sir Samuel Griffith

, Barton was several times consulted by Governors-General of Australia on the exercise of the reserve powers. In 1919, although ill, he was extremely disappointed to be passed over for the position of Chief Justice on the retirement of Griffith.

, Medlow Bath, New South Wales

. He was interred in South Head General Cemetery in the Sydney suburb of Vaucluse

(see Waverley Cemetery

). He was survived by his wife and six children:

in 1902. He received an honorary LL.D. from the University of Cambridge

in 1900.

In 1905, the Japanese government conferred the Grand Cordon, Order of the Rising Sun

, and Sir Edmund was granted permission to retain and wear the insignia. The honour was presented in acknowledgement of his personal role in resolving a conflict concerning the Commonwealth's Pacific Island Labourers Act and the Queensland protocol to the Anglo-Japanese Treaty.

In 1951 and again in 1969, Sir Edmund was honoured on postage stamp

s bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post

.

Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is an order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince Regent, later George IV of the United Kingdom, while he was acting as Prince Regent for his father, George III....

, KC

Queen's Counsel

Queen's Counsel , known as King's Counsel during the reign of a male sovereign, are lawyers appointed by letters patent to be one of Her [or His] Majesty's Counsel learned in the law...

(18 January 1849 – 7 January 1920), Australian politician and judge, was the first Prime Minister of Australia

Prime Minister of Australia

The Prime Minister of the Commonwealth of Australia is the highest minister of the Crown, leader of the Cabinet and Head of Her Majesty's Australian Government, holding office on commission from the Governor-General of Australia. The office of Prime Minister is, in practice, the most powerful...

and a founding justice of the High Court of Australia

High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the supreme court in the Australian court hierarchy and the final court of appeal in Australia. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction, has the power of judicial review over laws passed by the Parliament of Australia and the parliaments of the States, and...

.

Barton's greatest contribution to Australian history was his management of the federation movement through the 1890s. Elected at the inaugural 1901 federal election, he led the Protectionist party and government with the support of the Australian Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

. Barton resigned from the position of Prime Minister of Australia in 1903 and became a judge of Australia's High Court. He is one of only three Australian prime ministers who left the position at a time of their own choosing.

Early life

Glebe, New South Wales

Glebe is an inner-city suburb of Sydney. Glebe is located 3 km south-west of the Sydney central business district and is part of the local government area of the City of Sydney, in the Inner West region....

, the ninth child of English

English people

The English are a nation and ethnic group native to England, who speak English. The English identity is of early mediaeval origin, when they were known in Old English as the Anglecynn. England is now a country of the United Kingdom, and the majority of English people in England are British Citizens...

parents William Barton, a stockbroker, and Mary Louise Barton. He was educated at Fort Street High School

Fort Street High School

Fort Street High School is a co-educational, academically selective, public high school currently located at Petersham, an inner western suburb of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia....

and Sydney Grammar School

Sydney Grammar School

Sydney Grammar School is an independent, non-denominational, selective, day school for boys, located in Darlinghurst, Edgecliff and St Ives, all suburbs of Sydney, New South Wales, Australia....

, where he was twice dux

Dux

Dux is Latin for leader and later for Duke and its variant forms ....

and School Captain

School Captain

School Captain is a student appointed or elected to represent the school.This student, usually in the senior year, in their final year of attending that school...

and met his life-long friend and later fellow Justice of the High Court of Australia, Richard O'Connor. He graduated with first class honours and the University Medal

University Medal

A University Medal is one of several different types of awards, bestowed by universities upon outstanding students or members of staff. The usage and status of university medals differ between countries.-As award on graduation:...

in classics from the University of Sydney

University of Sydney

The University of Sydney is a public university located in Sydney, New South Wales. The main campus spreads across the suburbs of Camperdown and Darlington on the southwestern outskirts of the Sydney CBD. Founded in 1850, it is the oldest university in Australia and Oceania...

, where he also demonstrated considerable skill at batting (but not in fielding) in cricket

Cricket

Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of 11 players on an oval-shaped field, at the centre of which is a rectangular 22-yard long pitch. One team bats, trying to score as many runs as possible while the other team bowls and fields, trying to dismiss the batsmen and thus limit the...

. Barton became a barrister in 1871. On a cricket trip to Newcastle

Newcastle, New South Wales

The Newcastle metropolitan area is the second most populated area in the Australian state of New South Wales and includes most of the Newcastle and Lake Macquarie Local Government Areas...

in 1870, he met Jane Mason Ross, whom he married in 1877.

In 1879, Barton umpired

Umpire (cricket)

In cricket, an umpire is a person who has the authority to make judgements on the cricket field, according to the Laws of Cricket...

a cricket game at Sydney Cricket Ground

Sydney Cricket Ground

The Sydney Cricket Ground is a sports stadium in Sydney in Australia. It is used for Australian football, Test cricket, One Day International cricket, some rugby league and rugby union matches and is the home ground for the New South Wales Blues cricket team and the Sydney Swans of the Australian...

between New South Wales

New South Wales

New South Wales is a state of :Australia, located in the east of the country. It is bordered by Queensland, Victoria and South Australia to the north, south and west respectively. To the east, the state is bordered by the Tasman Sea, which forms part of the Pacific Ocean. New South Wales...

and an English touring side captained by Lord Harris

George Harris, 4th Baron Harris

George Robert Canning Harris, 4th Baron Harris, GCSI, GCIE was a British politician, cricketer and cricket administrator...

. After a controversial decision by Barton's colleague George Coulthard

George Coulthard

George Coulthard was a star Australian rules footballer who played for Carlton. He was also a notable cricketer who played for the Melbourne Cricket Club and briefly for Australia. As a cricketer he played only six first-class matches, five for Victoria and a Test match for Australia...

against the home side, the crowd spilled onto the pitch and assaulted some of the English players, leading to international cricket's first riot

Sydney Riot of 1879

The Sydney Riot of 1879 was a civil disorder that occurred at an early international cricket match. It took place in Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, at the Association Ground, Moore Park, now known as the Sydney Cricket Ground, during a match between a touring English team captained by Lord...

. The publicity that attended the young Barton's presence of mind in defusing that situation reputedly helped him take his first step towards becoming Australia's first prime minister, winning a state lower house seat later that year.

Federal Campaign

In 1876 Barton stood for the Legislative AssemblyNew South Wales Legislative Assembly

The Legislative Assembly, or lower house, is one of the two chambers of the Parliament of New South Wales, an Australian state. The other chamber is the Legislative Council. Both the Assembly and Council sit at Parliament House in the state capital, Sydney...

in the poll of the graduates of the University of Sydney

Electoral district of University of Sydney

University of Sydney was a former electoral district of the Legislative Assembly in the Australian state of New South Wales from 1876 to 1880. It was established in the 1858 redistribution to be elected by graduates of the University of Sydney once there were 100 eligible electors...

(who were required to wear gowns for the occasion), but was beaten by William Charles Windeyer

William Charles Windeyer

Sir William Charles Windeyer was an Australian politician and judge.As a New South Wales politician he was responsible for the creation of Belmore Park , Lang Park , Observatory Park Sir William Charles Windeyer (29 September 1834 – 11 September 1897) was an Australian politician and judge.As a...

49 votes to 43. He was defeated again for the same seat in 1877, but won in August 1879. When it was abolished in 1880, he became the member for Wellington, from November 1880 to 1882, and East Sydney

Electoral district of East Sydney

East Sydney was an electoral district for the Legislative Assembly in the Australian State of New South Wales created in 1859 from part of the electoral district of Sydney, covering the eastern part of the current Sydney central business district, Woolloomooloo, Potts Point, Elizabeth Bay and...

, from November 1882 to January 1887. At this stage he considered it "almost unnecessary" to point out his support for free trade.

In 1882, he became Speaker of the Assembly and, in 1884, was elected President of the University of Sydney Union

University of Sydney Union

The University of Sydney Union is the student-run services and amenities provider at the University of Sydney. The Union's key services include the provision of food and beverages, live music and other entertainment, the Verge Arts Festival and other cultural activities, Orientation week and...

. In 1887, Barton was appointed to the Legislative Council

New South Wales Legislative Council

The New South Wales Legislative Council, or upper house, is one of the two chambers of the parliament of New South Wales in Australia. The other is the Legislative Assembly. Both sit at Parliament House in the state capital, Sydney. The Assembly is referred to as the lower house and the Council as...

at the instigation of Sir Henry Parkes

Henry Parkes

Sir Henry Parkes, GCMG was an Australian statesman, the "Father of Federation." As the earliest advocate of a Federal Council of the colonies of Australia, a precursor to the Federation of Australia, he was the most prominent of the Australian Founding Fathers.Parkes was described during his...

. In January 1889, he agreed to being appointed Attorney-General in George Dibbs

George Dibbs

Sir George Richard Dibbs KCMG was an Australian politician who was Premier of New South Wales on three occasions.-Early years:Dibbs was born in Sydney, son of Captain John Dibbs, who disappeared in the same year...

's Protectionist

Protectionist Party

The Protectionist Party was an Australian political party, formally organised from 1889 until 1909, with policies centred on protectionism. It argued that Australia needed protective tariffs to allow Australian industry to grow and provide employment. It had its greatest strength in Victoria and in...

government, despite his previous support for free trade. This government only lasted until March, when Parkes formed government again.

1891 National Australasian Convention

Henry Parkes

Sir Henry Parkes, GCMG was an Australian statesman, the "Father of Federation." As the earliest advocate of a Federal Council of the colonies of Australia, a precursor to the Federation of Australia, he was the most prominent of the Australian Founding Fathers.Parkes was described during his...

' Tenterfield Oration

Tenterfield Oration

The Tenterfield Oration was a speech given by Sir Henry Parkes at the Tenterfield School of Arts, New South Wales, Australia on 24 October 1889 asking for the Federation of the six Australian colonies, which were at the time self-governed but under the distant central authority of the British...

, and was a delegate to the March 1891 National Australasian Convention. At the convention he made clear his support for the principle that "trade and intercourse … shall be absolutely free" in a federal Australia. He also advocated that, not just the lower house, but the upper house should be representative and that appeals to the Privy Council

Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council is one of the highest courts in the United Kingdom. Established by the Judicial Committee Act 1833 to hear appeals formerly heard by the King in Council The Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) is one of the highest courts in the United...

should be abolished. He also took part in producing a draft constitution, which was substantially similar to the Australian Constitution

Constitution of Australia

The Constitution of Australia is the supreme law under which the Australian Commonwealth Government operates. It consists of several documents. The most important is the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia...

enacted in 1900.

Nevertheless, the protectionists were lukewarm supporters of federation and in June 1891, Barton resigned from the Council and stood for election to East Sydney and announced that "so long as Protection meant a Ministry of enemies to Federation, they would get no vote from him". He topped the poll and subsequently voted with Parkes, but refused to take a position in his minority government. After the Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

withdrew support and the government fell in October 1891, Parkes persuaded him to take over the leadership of the Federal movement in New South Wales.

Attorney-General for the second time

Dibbs formed a ProtectionistProtectionist Party

The Protectionist Party was an Australian political party, formally organised from 1889 until 1909, with policies centred on protectionism. It argued that Australia needed protective tariffs to allow Australian industry to grow and provide employment. It had its greatest strength in Victoria and in...

government and Barton agreed to be Attorney-General with the right of carry out private practice as a lawyer. His agreement was based on Dibbs agreeing to support federal resolutions in the coming parliamentary session. His attempt to draft the federal resolutions was delayed by a period as acting premier

Premiers of New South Wales

The Premier of New South Wales is the head of government in the state of New South Wales, Australia. The Government of New South Wales follows the Westminster system, with a Parliament of New South Wales acting as the legislature...

, when he had to deal with the 1892 Broken Hill miners' strike

1892 Broken Hill miners' strike

The 1892 Broken Hill miners' strike was a sixteen week strike which was one of four major strikes that took place between 1889 and 1920 in Broken Hill, NSW, Australia....

, and his carriage of a complex electoral reform bill. He introduced the federal resolutions into the House on 22 November 1892 but was unable to get them considered in committee.

Meanwhile, he began a campaign to spread support for federation to the people with meetings in Corowa

Corowa, New South Wales

Corowa is a town in the state of New South Wales in Australia. It is on the bank of the Murray River, the border between New South Wales and Victoria, opposite the Victorian town of Wahgunyah. Corowa is the administrative centre of Corowa Shire...

and Albury

Albury, New South Wales

Albury is a major regional city in New South Wales, Australia, located on the Hume Highway on the northern side of the Murray River. It is located wholly within the boundaries of the City of Albury Local Government Area...

in December 1892. Although he finally managed to get the federal resolutions considered in committee in October 1893, he then could not get them listed for debate by the House. In December, he and Richard O'Connor, the Minister for Justice, were questioned about their agreement to act as private lawyers against the government in Proudfoot v. the Railway Commissioners. While Barton resigned the brief, he lost a motion on the right of ministers to act in their professional capacity as lawyers in actions against the government, and immediately resigned as Attorney-General.

In July 1894, Barton stood for re-election for Randwick

Electoral district of Randwick

Randwick was an Australian electoral district of the Legislative Assembly in the Australian state of New South Wales, originally created with the abolition of multi-member constituencies in 1894 from part of Paddington, along with Waverley and Woollahra. It was named after and including the Sydney...

(the multi-member electorate of East Sydney had been abolished) and lost. He did not stand for election in the 1895 elections, because of the need to support his large family during a period when parliamentarians were not paid. However, he continued to campaign for federation and during the period between January 1893 to February 1897, Barton addressed nearly 300 meetings in New South Wales, including in the Sydney suburb of Ashfield

Ashfield, New South Wales

Ashfield is a suburb in the inner-west of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Ashfield is about 9 kilometres south-west of the Sydney central business district and is the administrative centre for the local government area of the Municipality of Ashfield.The official name for the...

where he declared that "For the first time in history, we have a nation for a continent and a continent for a nation". By March 1897 he was considered "the acknowledged leader of the federal movement in all Australia".

Australasian Federal Convention and referendum

In 1897 Edmund Barton topped the poll of the delegates elected from New South Wales to the Constitutional ConventionConstitutional Convention (Australia)

In Australian history, the term Constitutional Convention refers to four distinct gatherings.-1891 convention:The 1891 Constitutional Convention was held in Sydney in March 1891 to consider a draft Constitution for the proposed federation of the British colonies in Australia and New Zealand. There...

which developed a constitution for the proposed federation. Although Sir Samuel Griffith

Samuel Griffith

Sir Samuel Walker Griffith GCMG QC, was an Australian politician, Premier of Queensland, Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia and a principal author of the Constitution of Australia.-Early life:...

wrote most of the text of the Constitution, Barton was the political leader who carried it through the Convention.

In May 1897 Barton was appointed for the second time to the Legislative Council on Reid's recommendations to take charge of the federation bill in the Upper House. This gave Reid's Attorney-General, John Henry Want

John Henry Want

John Henry Want was an Australian barrister and politician, as well as the 19th Attorney-General of New South Wales.-Early life:...

a free hand to oppose the bill. In September 1897 the convention met in Sydney to consider 286 proposed amendments from the colonies. It finalised its draft constitution in March 1898 and Barton went back to New South Wales to lead the campaign for a yes vote in the June referendum. Although it gained majority support, it only achieved 71,595 of the minimum 80,000 required to pass.

In July 1898 Barton resigned from the Upper House to stand against Reid for election to the Legislative Assembly, but narrowly lost. In September, he won a by-election for Hastings and Macleay

Electoral district of Hastings and Macleay

Hastings and Macleay was an electoral district of the Legislative Assembly in the Australian state of New South Wales from 1894 to 1920. It was created with the division of the two-member electorate of Hastings and Manning. In 1920 proportional representation was introduced and Hastings and Macleay...

and was immediately elected leader of the opposition, which consisted of a mixture of pro-federation and anti-federation protectionists. In January 1899 Reid gained significant concessions from the other states and he joined Barton in campaigning for the second referendum in June 1899, with Barton campaigning all over the state. It passed 107,420 votes to 82,741.

In August 1899 when it became clear that the Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

could be maneuvered into bringing down the Reid Government, Barton resigned as leader of the opposition, as he was unacceptable to Labor, and William Lyne

William Lyne

Sir William John Lyne KCMG , Australian politician, was Premier of New South Wales and a member of the first federal ministry.-Early life:...

took his place. He refused an offer to become Attorney-General again. He resigned from Parliament in February 1900 so that he could travel to London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

with Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin , Australian politician, was a leader of the movement for Australian federation and later the second Prime Minister of Australia. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Deakin was a major contributor to the establishment of liberal reforms in the colony of Victoria, including the...

and Charles Kingston

Charles Kingston

Charles Cameron Kingston, Australian politician, was an early liberal Premier of South Australia serving from 1893 to 1899 with the support of Labor led by John McPherson from 1893 and Lee Batchelor from 1897 in the House of Assembly, winning the 1893, 1896, and 1899 state elections against the...

to explain the federation bill to the British Government. The British Government was adamant in its opposition to the abolition of appeals to the Privy Council as incorporated in the draft constitution—eventually Barton agreed that constitutional (inter se

Inter se

Inter se is a Legal Latin phrase meaning "between or amongst themselves". For example;In Australian constitutional law, it refers to matters concerning a dispute between the Commonwealth and one or more of the States concerning the extents of their respective powers....

) matters would be finalised in the High Court

High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the supreme court in the Australian court hierarchy and the final court of appeal in Australia. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction, has the power of judicial review over laws passed by the Parliament of Australia and the parliaments of the States, and...

, but other matters could be appealed to the Privy Council.

First Prime Minister

Governor-General of Australia

The Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia is the representative in Australia at federal/national level of the Australian monarch . He or she exercises the supreme executive power of the Commonwealth...

, Lord Hopetoun

John Hope, 1st Marquess of Linlithgow

John Adrian Louis Hope, 1st Marquess of Linlithgow KT, GCMG, GCVO, PC , also known as Viscount Aithrie before 1873 and as The 7th Earl of Hopetoun between 1873 and 1902, was a Scottish aristocrat, politician and colonial administrator. He is best known for his brief and controversial tenure as the...

, instead invited Sir William Lyne

William Lyne

Sir William John Lyne KCMG , Australian politician, was Premier of New South Wales and a member of the first federal ministry.-Early life:...

, the premier of New South Wales, to form a government.

Hopetoun's decision, known as the Hopetoun Blunder

Hopetoun Blunder

The Hopetoun Blunder was a political event immediately prior to the Federation of the British colonies in Australia.Federation was scheduled to occur on 1 January 1901, but since the general election for the first Parliament of Australia was not to be held until March of that year, it was not...

, can be defended on grounds that Lyne had seniority. Still, Lyne's long massive opposition to federation until he changed his mind at the last minute caused him to be unacceptable to prominent federalists such as Deakin, who refused to serve under him. After tense negotiations, Barton was appointed Prime Minister and he and his ministry were sworn in on 1 January 1901.

Barton's government consisted of himself as Prime Minister and Minister for External Affairs, Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin

Alfred Deakin , Australian politician, was a leader of the movement for Australian federation and later the second Prime Minister of Australia. In the last quarter of the 19th century, Deakin was a major contributor to the establishment of liberal reforms in the colony of Victoria, including the...

as Attorney-General, Sir William Lyne as Minister for Home Affairs, Sir George Turner as Treasurer, Charles Kingston

Charles Kingston

Charles Cameron Kingston, Australian politician, was an early liberal Premier of South Australia serving from 1893 to 1899 with the support of Labor led by John McPherson from 1893 and Lee Batchelor from 1897 in the House of Assembly, winning the 1893, 1896, and 1899 state elections against the...

as Minister for Trade and Customs, Sir James Dickson

James Dickson

Sir James Robert Dickson, KCMG was an Australian politician and businessman, the 13th Premier of Queensland and a member of the first federal ministry....

as Minister for Defence, and Sir John Forrest

John Forrest

Sir John Forrest GCMG was an Australian explorer, the first Premier of Western Australia and a cabinet minister in Australia's first federal parliament....

as Postmaster-General. Richard O'Connor was made Vice-President of the Executive Council and Elliott Lewis

Elliott Lewis

Sir Neil Elliott Lewis, KCMG , Australian politician, was Premier of Tasmania on three occasions. He was also a member of the first Australian federal ministry, led by Edmund Barton....

was appointed Minister without Portfolio. Only ten days into the life of the government, Sir James Dickson died suddenly; he was replaced on 17 January as Minister for Defence by John Forrest, and James Drake

James Drake

James George Drake , Australian politician, was a member of the first federal ministry.Drake was born in London and educated at King's College School, and migrated to Australia in 1873, working as a storekeeper and journalist in Queensland...

was brought into the ministry as Postmaster-General on 5 February.

The main task of Barton's ministry

Barton Ministry

The Barton Ministry was the first Australian Commonwealth ministry, and ran from 1 January 1901 to 24 September 1903. The ministry was made up of Protectionist Party members....

was to organise the conduct of the first federal elections, which were held in March 1901. Barton was elected unopposed to the seat of Hunter

Division of Hunter

The Division of Hunter is an Australian Electoral Division in the state of New South Wales. It is located in northern rural New South Wales, and encompasses much of the Hunter Valley region, including the towns of Singleton, Maitland, Muswellbrook, Cessnock and Denman...

in the new Parliament (although he never lived in that electorate) and his Protectionist Party won enough seats to form a government with the support of the Labor Party

Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party is an Australian political party. It has been the governing party of the Commonwealth of Australia since the 2007 federal election. Julia Gillard is the party's federal parliamentary leader and Prime Minister of Australia...

. All his ministers were elected, except for Elliott Lewis, who did not stand for election and was replaced by Sir Philip Fysh

Philip Fysh

Sir Philip Oakley Fysh, KCMG was an Australian politician, Premier of Tasmania and a member of the first federal ministry....

.

An early piece of legislation of the Barton government was the Immigration Restriction Act 1901

Immigration Restriction Act 1901

The Immigration Restriction Act 1901 was an Act of the Parliament of Australia which limited immigration to Australia and formed the basis of the White Australia policy. It also provided for illegal immigrants to be deported. It granted immigration officers a wide degree of discretion to prevent...

, which put the White Australia policy

White Australia policy

The White Australia policy comprises various historical policies that intentionally restricted "non-white" immigration to Australia. From origins at Federation in 1901, the polices were progressively dismantled between 1949-1973....

into law. The Labor Party required legislation to limit immigration from Asia as part of its agreement to support the government, although in fact Barton had promised the introduction of the White Australia Policy in his election campaign. Barton stated "The doctrine of the equality of man was never intended to apply to the equality of the Englishman and the Chinaman". One notable reform was the introduction of women's suffrage for federal elections in 1902.

Barton was a moderate conservative, and advanced liberals in his party disliked his relaxed attitude to political life. A large, handsome, jovial man, he was fond of long dinners and good wine and was given the nickname "Toby Tosspot" by the Bulletin

The Bulletin

The Bulletin was an Australian weekly magazine that was published in Sydney from 1880 until January 2008. It was influential in Australian culture and politics from about 1890 until World War I, the period when it was identified with the "Bulletin school" of Australian literature. Its influence...

.

For much of 1902 Barton was in England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

for the coronation of King Edward VII

Edward VII of the United Kingdom

Edward VII was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions and Emperor of India from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910...

. This trip was also used to negotiate the replacement of the naval agreements between the Australian colonies and the United Kingdom (under which Australia funded Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

protection from foreign naval threats) by an agreement between the Commonwealth and the United Kingdom. Deakin disliked this arrangement and discontinued it and moved to substantially expand Australia's own navy

Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy is the naval branch of the Australian Defence Force. Following the Federation of Australia in 1901, the ships and resources of the separate colonial navies were integrated into a national force: the Commonwealth Naval Forces...

in 1908.

In September 1903, Sir Edmund Barton left Parliament to become one of the founding justices of the High Court of Australia

High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the supreme court in the Australian court hierarchy and the final court of appeal in Australia. It has both original and appellate jurisdiction, has the power of judicial review over laws passed by the Parliament of Australia and the parliaments of the States, and...

. He was succeeded as Prime Minister by Deakin on 24 September.

Judicial career

Parliament of Australia

The Parliament of Australia, also known as the Commonwealth Parliament or Federal Parliament, is the legislative branch of the government of Australia. It is bicameral, largely modelled in the Westminster tradition, but with some influences from the United States Congress...

prior to his appointment to the Court; the others were Richard O'Connor, Isaac Isaacs

Isaac Isaacs

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs GCB GCMG KC was an Australian judge and politician, was the third Chief Justice of Australia, ninth Governor-General of Australia and the first born in Australia to occupy that post. He is the only person ever to have held both positions of Chief Justice of Australia and...

, H. B. Higgins

H. B. Higgins

Henry Bournes Higgins , Australian politician and judge, always known in his lifetime as H. B. Higgins, was a highly influential figure in Australian politics and law.-Career:...

, Edward McTiernan

Edward McTiernan

Sir Edward Aloysius McTiernan, KBE , was an Australian jurist, lawyer and politician. He served as an Australian Labor Party member of both the New South Wales Legislative Assembly and federal House of Representatives before being appointed to the High Court of Australia in 1930...

, John Latham, Garfield Barwick

Garfield Barwick

Sir Garfield Edward John Barwick, was the Attorney-General of Australia , Minister for External Affairs and the seventh and longest serving Chief Justice of Australia...

, and Lionel Murphy

Lionel Murphy

Lionel Keith Murphy, QC was an Australian politician and jurist who served as Attorney-General in the government of Gough Whitlam and as a Justice of the High Court of Australia from 1975 until his death.- Personal life :...

. Barton was also one of six justices to have served in the Parliament of New South Wales

Parliament of New South Wales

The Parliament of New South Wales, located in Parliament House on Macquarie Street, Sydney, is the main legislative body in the Australian state of New South Wales . It is a bicameral parliament elected by the people of the state in general elections. The parliament shares law making powers with...

, along with O'Connor, Albert Piddington

Albert Piddington

Albert Bathurst Piddington was the shortest serving Justice of the High Court of Australia, never actually sitting at the bench. Appointed on 6 March 1913, he resigned on 5 April after opponents questioned his independence.-Early life:Piddington was born in 1862 in Bathurst, New South Wales...

, Adrian Knox

Adrian Knox

Sir Adrian Knox KCMG, KC , Australian judge, was the second Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia, sitting on the bench of the High Court from 1919 to 1930.-Education:...

, McTiernan, and H. V. Evatt

H. V. Evatt

Herbert Vere Evatt, QC KStJ , was an Australian jurist, politician and writer. He was President of the United Nations General Assembly in 1948–49 and helped draft the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights...

.

On the bench Sir Edmund was considered a good and "scrupulously impartial" judge and adopted the same position of moderate conservatism he had taken in politics. Along with his colleagues Griffith

Samuel Griffith

Sir Samuel Walker Griffith GCMG QC, was an Australian politician, Premier of Queensland, Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia and a principal author of the Constitution of Australia.-Early life:...

and O'Connor, he attempted to preserve the autonomy of the States and developed a doctrine of "implied immunity of instrumentalities", which prevented the States from taxing Commonwealth officers, and also prevented the Commonwealth from arbitrating industrial disputes in the States' railways. They also narrowly interpreted the Federal Government's powers in commercial and industrial matters.

After 1906, Sir Edmund increasingly clashed with Isaac Isaacs

Isaac Isaacs

Sir Isaac Alfred Isaacs GCB GCMG KC was an Australian judge and politician, was the third Chief Justice of Australia, ninth Governor-General of Australia and the first born in Australia to occupy that post. He is the only person ever to have held both positions of Chief Justice of Australia and...

and H. B. Higgins

H. B. Higgins

Henry Bournes Higgins , Australian politician and judge, always known in his lifetime as H. B. Higgins, was a highly influential figure in Australian politics and law.-Career:...

, the two advanced liberals appointed to the court by Deakin. Like Sir Samuel Griffith

Samuel Griffith

Sir Samuel Walker Griffith GCMG QC, was an Australian politician, Premier of Queensland, Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia and a principal author of the Constitution of Australia.-Early life:...

, Barton was several times consulted by Governors-General of Australia on the exercise of the reserve powers. In 1919, although ill, he was extremely disappointed to be passed over for the position of Chief Justice on the retirement of Griffith.

Death and family

Sir Edmund Barton died from heart failure at the Hydro Majestic HotelHydro Majestic Hotel

The Hydro Majestic Hotel is located in Medlow Bath, New South Wales, Australia. The hotel is located on a clifftop overlooking the Megalong Valley on the western side of the Great Western Highway....

, Medlow Bath, New South Wales

Medlow Bath, New South Wales

Medlow Bath is an Australian small town located near the highest point of the Blue Mountains, between Katoomba and Blackheath. It has an approximate altitude of 1050m and is located approximately 115 kilometres west north west of Sydney and 5 kilometres north west of Katoomba...

. He was interred in South Head General Cemetery in the Sydney suburb of Vaucluse

Vaucluse, New South Wales

Vaucluse is an eastern suburb of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Vaucluse is located north-east of the Sydney central business district, in the local government areas of Waverley Council and the Municipality of Woollahra....

(see Waverley Cemetery

Waverley Cemetery

The Waverley Cemetery opened in 1877 and is a cemetery located on top of the cliffs at Bronte in the eastern suburbs of Sydney. It is noted for its largely intact Victorian and Edwardian monuments. The cemetery contains the graves of many significant Australians including the poet Henry Lawson and...

). He was survived by his wife and six children:

- Edmund Alfred (29 May 1879 – 13 November 1949), a New South Wales judge

- Wilfrid Alexander (1880–1953), first NSW Rhodes ScholarRhodes ScholarshipThe Rhodes Scholarship, named after Cecil Rhodes, is an international postgraduate award for study at the University of Oxford. It was the first large-scale programme of international scholarships, and is widely considered the "world's most prestigious scholarship" by many public sources such as...

(1904) - Jean Alice (1882–1957), married Sir David Maughan (1873–1955) in 1909

- Arnold Hubert (3 January 1884-1948), married Jane Hungerford in Sydney 1907; he later emigrated to Canada

- Oswald (8 January 1888 – 6 February 1956), medical doctor

- Leila Stephanie (1892–1976), married Robert Christopher Churchill Scot-Skirving in London 1915

Honours

Barton refused knighthoods in 1887, 1891 and 1899, but agreed to be made a Knight Grand Cross of St Michael and St GeorgeOrder of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is an order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince Regent, later George IV of the United Kingdom, while he was acting as Prince Regent for his father, George III....

in 1902. He received an honorary LL.D. from the University of Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

in 1900.

In 1905, the Japanese government conferred the Grand Cordon, Order of the Rising Sun

Order of the Rising Sun

The is a Japanese order, established in 1875 by Emperor Meiji of Japan. The Order was the first national decoration awarded by the Japanese Government, created on April 10, 1875 by decree of the Council of State. The badge features rays of sunlight from the rising sun...

, and Sir Edmund was granted permission to retain and wear the insignia. The honour was presented in acknowledgement of his personal role in resolving a conflict concerning the Commonwealth's Pacific Island Labourers Act and the Queensland protocol to the Anglo-Japanese Treaty.

In 1951 and again in 1969, Sir Edmund was honoured on postage stamp

Postage stamp

A postage stamp is a small piece of paper that is purchased and displayed on an item of mail as evidence of payment of postage. Typically, stamps are made from special paper, with a national designation and denomination on the face, and a gum adhesive on the reverse side...

s bearing his portrait issued by Australia Post

Australia Post

Australia Post is the trading name of the Australian Government-owned Australian Postal Corporation .-History:...

.