Evidence of evolution

Encyclopedia

of living things has been discovered by scientists working in a variety of fields over many years. This evidence has demonstrated and verified the occurrence of evolution

and provided a wealth of information on the natural processes by which the variety and diversity of life on Earth developed. This evidence supports the modern evolutionary synthesis

, the current scientific theory

that explains how and why life changes over time. Evolutionary biologists document the fact of common descent

: making testable predictions, testing hypotheses, and developing theories that illustrate and describe its causes.

Comparison of the genetic sequence

of organisms has revealed that organisms that are phylogenetically

close have a higher degree of sequence similarity than organisms that are phylogenetically distant. Further evidence for common descent comes from genetic detritus such as pseudogene

s, regions of DNA

that are orthologous to a gene in a related organism

, but are no longer active and appear to be undergoing a steady process of degeneration.

Fossils are important for estimating when various lineages developed in geologic time. As fossilization is an uncommon occurrence, usually requiring hard body parts and death near a site where sediment

s are being deposited, the fossil record only provides sparse and intermittent information about the evolution of life. Evidence

of organisms prior to the development of hard body parts such as shells, bones and teeth is especially scarce, but exists in the form of ancient microfossils, as well as impressions of various soft-bodied organisms. The comparative study of the anatomy

of groups of animals shows structural features that are fundamentally similar or homologous, demonstrating phylogenetic and ancestral relationships with other organism, most especially when compared with fossils of ancient extinct

organisms. Vestigial structures and comparisons in embryonic development

are largely a contributing factor in anatomical resemblance in concordance with common descent. Since metabolic

processes do not leave fossils, research into the evolution of the basic cellular processes is done largely by comparison of existing organisms’ physiology

and biochemistry

. Many lineages diverged at different stages of development, so it is possible to determine when certain metabolic processes appeared by comparing the traits of the descendants of a common ancestor. Universal biochemical organization and molecular variance patterns in all organisms also show a direct correlation with common descent.

Further evidence comes from the field of biogeography

because evolution with common descent provides the best and most thorough explanation for a variety of facts concerning the geographical distribution of plants and animals across the world. This is especially obvious in the field of island biogeography

. Combined with the theory of plate tectonics

common descent provides a way to combine facts about the current distribution of species with evidence from the fossil record to provide a logically consistent explanation of how the distribution of living organisms has changed over time.

The development and spread of antibiotic resistant

bacteria, like the spread of pesticide resistant forms of plants and insects provides evidence that evolution due to natural selection

is an ongoing process in the natural world. Alongside this, are observed instances of the separation of populations of species into sets of new species (speciation

). Speciation has been observed directly and indirectly in the lab and in nature. Multiple forms of such have been described and documented as examples for individual modes of speciation. Furthermore, evidence of common descent extends from direct laboratory experimentation with the artificial selection of organisms—historically and currently—and other controlled experiments involving many of the topics in the article. This article explains the different types of evidence for evolution with common descent along with many specialized examples of each.

One of the strongest evidences for common descent comes from the study of gene sequences. Comparative sequence analysis

One of the strongest evidences for common descent comes from the study of gene sequences. Comparative sequence analysis

examines the relationship between the DNA sequences of different species, producing several lines of evidence that confirm Darwin's original hypothesis of common descent. If the hypothesis of common descent is true, then species that share a common ancestor will have inherited that ancestor's DNA sequence. They will have inherited mutations unique to that ancestor. More closely related species will have a greater fraction of identical sequence and will have shared substitutions when compared to more distantly related species.

The simplest and most powerful evidence is provided by phylogenetic reconstruction

. Such reconstructions, especially when done using slowly evolving protein sequences, are often quite robust and can be used to reconstruct a great deal of the evolutionary history of modern organisms (and even in some instances such as the recovered gene sequences of mammoth

s, Neanderthal

s or T. rex

, the evolutionary history of extinct organisms). These reconstructed phylogenies recapitulate the relationships established through morphological and biochemical studies. The most detailed reconstructions have been performed on the basis of the mitochondrial genomes shared by all eukaryotic

organisms, which are short and easy to sequence; the broadest reconstructions have been performed either using the sequences of a few very ancient proteins or by using ribosomal RNA

sequence.

Phylogenetic relationships also extend to a wide variety of nonfunctional sequence elements, including repeats, transposons, pseudogenes, and mutations in protein-coding sequences that do not result in changes in amino-acid sequence. While a minority of these elements might later be found to harbor function, in aggregate they demonstrate that identity must be the product of common descent rather than common function.

, or RNA

for viruses), transcribed into RNA

, then translated into protein

s (that is, polymers of amino acid

s) by highly conserved ribosome

s. Perhaps most tellingly, the Genetic Code

(the "translation table" between DNA and amino acids) is the same for almost every organism, meaning that a piece of DNA

in a bacterium

codes for the same amino acid as in a human cell

. ATP

is used as energy currency by all extant life. A deeper understanding of developmental biology

shows that common morphology is, in fact, the product of shared genetic elements. For example, although camera-like eyes are believed to have evolved independently on many separate occasions, they share a common set of light-sensing proteins (opsin

s), suggesting a common point of origin for all sighted creatures. Another noteworthy example is the familiar vertebrate body plan, whose structure is controlled by the homeobox (Hox) family of genes.

trees are typically congruent with traditional taxonomy

, and are often used to strengthen or correct taxonomic classifications. Sequence comparison is considered a measure robust enough to be used to correct erroneous assumptions in the phylogenetic tree in instances where other evidence is scarce. For example, neutral human DNA sequences are approximately 1.2% divergent (based on substitutions) from those of their nearest genetic relative, the chimpanzee

, 1.6% from gorilla

s, and 6.6% from baboon

s. Genetic sequence evidence thus allows inference and quantification of genetic relatedness between humans and other ape

s. The sequence of the 16S ribosomal RNA

gene, a vital gene encoding a part of the ribosome

, was used to find the broad phylogenetic relationships between all extant life. The analysis, originally done by Carl Woese

, resulted in the three-domain system

, arguing for two major splits in the early evolution of life. The first split led to modern Bacteria

and the subsequent split led to modern Archaea

and Eukaryotes.

es (or ERVs) are remnant sequences in the genome left from ancient viral infections in an organism. The retroviruses (or virogenes) are always passed on

to the next generation of that organism which received the infection. This leaves the virogene left in the genome. Because this event is rare and random, finding identical chromosomal positions of a virogene in two different species suggests common ancestry. See examples of humans and cats below.

evidence also supports the universal ancestry of life. Vital protein

s, such as the ribosome

, DNA polymerase

, and RNA polymerase

, are found in everything from the most primitive bacteria to the most complex mammals. The core part of the protein is conserved across all lineages of life, serving similar functions. Higher organisms have evolved additional protein subunit

s, largely affecting the regulation and protein-protein interaction

of the core. Other overarching similarities between all lineages of extant organisms, such as DNA

, RNA

, amino acids, and the lipid bilayer

, give support to the theory of common descent. Phylogenetic analyses of protein sequences from various organisms produce similar trees of relationship between all organisms. The chirality

of DNA, RNA, and amino acids is conserved across all known life. As there is no functional advantage to right- or left-handed molecular chirality, the simplest hypothesis is that the choice was made randomly by early organisms and passed on to all extant life through common descent. Further evidence for reconstructing ancestral lineages comes from junk DNA such as pseudogene

s, "dead" genes which steadily accumulate mutations.

, are extra DNA in a genome that do not get transcribed into RNA to synthesize proteins. Some of this noncoding DNA has known functions, but much of it has no known function and is called "Junk DNA". This is an example of a vestige since replicating these genes uses energy, making it a waste in many cases. Pseudogenes make up 99% of the human genome (1% working DNA). A pseudogene can be produced when a coding gene accumulates mutations that prevent it from being transcribed, making it non-functional. But since it is not transcribed, it may disappear without affecting fitness, unless it has provided some new beneficial function as non-coding DNA. Non-functional pseudogenes may be passed on to later species, thereby labeling the later species as descended from the earlier species.

and gene duplication

, which facilitates rapid evolution by providing substantial quantities of genetic material under weak or no selective constraints; horizontal gene transfer

, the process of transferring genetic material to another cell that is not an organism's offspring, allowing for species to acquire beneficial genes from each other; and recombination

, capable of reassorting large numbers of different allele

s and of establishing reproductive isolation

. The Endosymbiotic theory

explains the origin of mitochondria

and plastid

s (e.g. chloroplast

s), which are organelle

s of eukaryotic cells, as the incorporation of an ancient prokaryotic

cell into ancient eukaryotic

cell. Rather than evolving eukaryotic

organelle

s slowly, this theory offers a mechanism for a sudden evolutionary leap by incorporating the genetic material and biochemical composition of a separate species. Evidence supporting this mechanism has been found in the protist

Hatena

: as a predator it engulfs a green algae

cell, which subsequently behaves as an endosymbiont

, nourishing Hatena, which in turn loses its feeding apparatus and behaves as an autotroph

.

Since metabolic

processes do not leave fossils, research into the evolution of the basic cellular processes is done largely by comparison of existing organisms. Many lineages diverged when new metabolic processes appeared, and it is theoretically possible to determine when certain metabolic processes appeared by comparing the traits of the descendants of a common ancestor or by detecting their physical manifestations. As an example, the appearance of oxygen

in the earth's atmosphere

is linked to the evolution of photosynthesis

.

) present another example of virogene sequences in common descent. The standard phylogenetic tree for Felidae have smaller cats (Felis chaus, Felis silvestris, Felis nigripes, and Felis catus) diverging from larger cats such as the subfamily Pantherinae

and other carnivores

. The small cats have an ERV where the larger cats do not suggesting that the gene was inserted into the ancestor of the small cats after the larger cats had diverged.

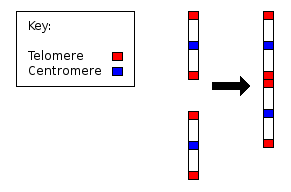

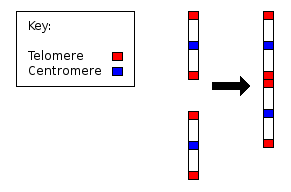

Evidence for the evolution of Homo sapiens from a common ancestor with chimpanzees is found in the number of chromosomes in humans as compared to all other members of Hominidae

Evidence for the evolution of Homo sapiens from a common ancestor with chimpanzees is found in the number of chromosomes in humans as compared to all other members of Hominidae

. All Hominidae (with the exception of humans) have 24 pairs of chromosomes. Humans have only 23 pairs. Human chromosome 2 is a result of an end-to-end fusion of two ancestral chromosomes.

The evidence for this includes:

Chromosome 2 thus presents very strong evidence in favour of the common descent of humans and other ape

s. According to J. W. IJdo, "We conclude that the locus cloned in cosmids c8.1 and c29B is the relic of an ancient telomere-telomere fusion and marks the point at which two ancestral ape chromosomes fused to give rise to human chromosome 2."

Cytochrome c

in living cells. The variance of cytochrome c of different organisms is measured in the number of differing amino acids, each differing amino acid being a result of a base pair

substitution, a mutation

. If each differing amino acid is assumed to be the result of one base pair substitution, it can be calculated how long ago the two species diverged by multiplying the number of base pair substitutions by the estimated time it takes for a substituted base pair of the cytochrome c gene to be successfully passed on. For example, if the average time it takes for a base pair of the cytochrome c gene to mutate is N years, the number of amino acids making up the cytochrome c protein in monkeys differ by one from that of humans, this leads to the conclusion that the two species diverged N years ago.

The primary structure of cytochrome c consists of a chain of about 100 amino acid

s. Many higher order organisms possess a chain of 104 amino acids.

The cytochrome c molecule has been extensively studied for the glimpse it gives into evolutionary biology. Both chicken

and turkey

s have identical sequence homology (amino acid for amino acid), as do pig

s, cows and sheep. Both human

s and chimpanzee

s share the identical molecule, while rhesus monkeys share all but one of the amino acids: the 66th amino acid is isoleucine

in the former and threonine

in the latter.

What makes these homologous similarities particularly suggestive of common ancestry in the case of cytochrome C, in addition to the fact that the phylogenies derived from them match other phylogenies very well, is the high degree of functional redundancy of the cytochrome C molecule. The different existing configurations of amino acids do not significantly affect the functionality of the protein, which indicates that the base pair substitutions are not part of a directed design, but the result of random mutations that aren't subject to selection.

, Ronald Fisher

and J. B. S. Haldane

and extended via diffusion theory by Motoo Kimura

, allow predictions about the genetic structure of evolving populations. Direct examination of the genetic structure of modern populations via DNA sequencing has allowed verification of many of these predictions. For example, the Out of Africa theory of human origins, which states that modern humans developed in Africa and a small sub-population migrated out (undergoing a population bottleneck

), implies that modern populations should show the signatures of this migration pattern. Specifically, post-bottleneck populations (Europeans and Asians) should show lower overall genetic diversity and a more uniform distribution of allele frequencies compared to the African population. Both of these predictions are borne out by actual data from a number of studies.

of groups of animals or plants reveals that certain structural features are basically similar. For example, the basic structure of all flower

s consists of sepal

s, petal

s, stigma, style and ovary

; yet the size, colour, number

of parts and specific structure are different for each individual species.

s that do not even reach the ground, chicken's teeth, reemergence of sexual reproduction

in Hieracium pilosella and Crotoniidae

; and humans with tails, extra nipple

s, and large canine teeth

.

) during human development; the appearance of transitions from fish to amphibians to reptiles and then to mammals in all mammal embryos; development and degeneration of a yolk sac

; terrestrial frogs and salamanders passing through the larval stage within the egg—with features of typically aquatic larvae—but hatch ready for life on land; and the appearance of gill-like structures (pharyngeal arch) in vertebrate embryo development. Note that in fish the arches become gills while in humans, for example, they become the pharynx

.

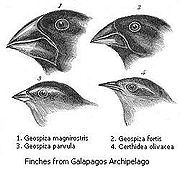

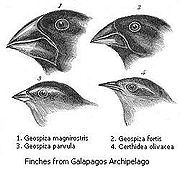

When a group of organisms share a homologous structure which is specialized to perform a variety of functions in order to adapt different environmental conditions and modes of life are called adaptive radiation

. The gradual spreading of organisms with adaptive radiation is known as divergent evolution

.

is based on the fact that all organisms are related to each other in nested hierarchies based on shared characteristics. Most existing species can be organized rather easily in a nested hierarchical classification. This is evident from the Linnaean classification scheme. Based on shared derived characters, closely related organisms can be placed in one group (such as a genus), several genera can be grouped together into one family, several families can be grouped together into an order, etc. The existence of these nested hierarchies was recognized by many biologists before Darwin, but he showed that his theory of evolution with its branching pattern of common descent could explain them. Darwin described how common descent could provide a logical basis for classification:

s) of flies

and mosquitos, wings of flightless birds such as ostrich

es, and the leaves

of some xerophyte

s (e.g. cactus

) and parasitic plant

s (e.g. dodder

). However, vestigial structures may have their original function replaced with another. For example, the halteres

in dipterist

s help balance the insect while in flight and the wings of ostriches are used in mating

rituals.

s possess internally reduced hind parts such as the pelvis and hind legs (Fig. 5a). Occasionally, the genes that code for longer extremities cause a modern whale to develop miniature legs. On October 28, 2006, a four-finned bottlenose dolphin was caught and studied due to its extra set of hind limbs. These legged Cetacea

display an example of an atavism predicted from their common ancestry.

s, a hypopharynx

(floor of mouth), a pair of maxillae, and a labium. (Fig. 5b) Evolution has caused enlargement and modification of these structures in some species, while it has caused the reduction and loss of them in other species. The modifications enable the insects to exploit a variety of food materials:

s: The anterior pair of legs may be modified as analogues of antennae, particularly in whip scorpions

, which walk on six legs. These developments provide support for the theory that complex modifications often arise by duplication of components, with the duplicates modified in different directions.

and ornithischia

. They are classified as one or the other in accordance with what the fossils demonstrate. Figure 5c, shows that early saurischians resembled early ornithischians. The pattern of the pelvis

in all species of dinosaurs is an example of homologous structures. Each order of dinosaur has slightly differing pelvis bones providing evidence of common descent. Additionally, modern birds show a similarity to ancient saurischian pelvic structures indicating the evolution of birds from dinosaurs. This can also be seen in Figure 5c as the Aves branch off the Theropoda

suborder.

s (i.e. from amphibian

s to mammal

s). It can even be traced back to the fin

s of certain fossil fishes from which the first amphibians evolved such as tiktaalik

. The limb has a single proximal bone (humerus

), two distal bones (radius

and ulna

), a series of carpals (wrist

bones), followed by five series of metacarpals (palm

bones) and phalanges (digits). Throughout the tetrapods, the fundamental structures of pentadactyl limbs are the same, indicating that they originated from a common ancestor. But in the course of evolution, these fundamental structures have been modified. They have become superficially different and unrelated structures to serve different functions in adaptation to different environments and modes of life. This phenomenon is shown in the forelimbs of mammals. For example:

is a fourth branch of the vagus nerve

, which is a cranial nerve. In mammals, its path is unusually long. As a part of the vagus nerve, it comes from the brain, passes through the neck down to heart, rounds the dorsal aorta

and returns up to the larynx

, again through the neck. (Fig. 5e)

This path is suboptimal even for humans, but for giraffes it becomes even more suboptimal. Due to the lengths of their necks, the recurrent laryngeal nerve may be up to 4m long (13 ft), despite its optimal route being a distance of just several inches.

The indirect route of this nerve is the result of evolution of mammals from fish, which had no neck and had a relatively short nerve that innervated one gill slit and passed near the gill arch. Since then, gills have evolved into lungs and the gill arch has become the dorsal aorta in mammals.

is part of the male anatomy of many vertebrates; it transports sperm from the epididymis

in anticipation of ejaculation

. In humans, the vas deferens routes up from the testicle

, looping over the ureter

, and back down to the urethra

and penis

. It has been suggested that this is due to the descent of the testicles during the course of human evolution—likely associated with temperature. As the testicles descended, the vas deferens lengthened to accommodate the accidental “hook” over the ureter.

.jpg) When organisms die, they often decompose

When organisms die, they often decompose

rapidly or are consumed by scavenger

s, leaving no permanent evidences of their existence. However, occasionally, some organisms are preserved. The remains or traces

of organisms from a past geologic age

embedded in rocks

by natural processes are called fossil

s. They are extremely important for understanding the evolutionary history of life

on Earth, as they provide direct evidence of evolution and detailed information on the ancestry of organisms. Paleontology

is the study of past life based on fossil records and their relations to different geologic time periods.

For fossilization to take place, the traces and remains of organisms must be quickly buried so that weathering

and decomposition do not occur. Skeletal structures or other hard parts of the organisms are the most commonly occurring form of fossilized remains (Paul, 1998), (Behrensmeyer, 1980) and (Martin, 1999). There are also some trace "fossils" showing moulds

, cast or imprints of some previous organisms.

As an animal dies, the organic materials gradually decay, such that the bone

s become porous. If the animal is subsequently buried in mud

, mineral

salts will infiltrate into the bones and gradually fill up the pores. The bones will harden into stones and be preserved as fossils. This process is known as petrification

. If dead animals are covered by wind-blown sand

, and if the sand is subsequently turned into mud by heavy rain

or flood

s, the same process of mineral infiltration may occur. Apart from petrification, the dead bodies of organisms may be well preserved in ice

, in hardened resin

of coniferous

trees (amber

), in tar, or in anaerobic, acid

ic peat

. Fossilization can sometimes be a trace, an impression of a form. Examples include leaves and footprints, the fossils of which are made in layers that then harden.

. Sedimentary rock is formed by layers of silt

or mud on top of each other; thus, the resulting rock contains a series of horizontal layers, or strata

. Each layer contains fossils which are typical for a specific time period during which they were made. The lowest strata contain the oldest rock and the earliest fossils, while the highest strata contain the youngest rock and more recent fossils.

A succession

of animals and plants can also be seen from fossil discoveries. By studying the number and complexity of different fossils at different stratigraphic

levels, it has been shown that older fossil-bearing rocks contain fewer types of fossilized organisms, and they all have a simpler structure, whereas younger rocks contain a greater variety of fossils, often with increasingly complex structures.

For many years, geologists could only roughly estimate the ages of various strata and the fossils found. They did so, for instance, by estimating the time for the formation of sedimentary rock layer by layer. Today, by measuring the proportions of radioactive

and stable elements

in a given rock, the ages of fossils can be more precisely dated by scientists. This technique is known as radiometric dating

.

Throughout the fossil record, many species that appear at an early stratigraphic level disappear at a later level. This is interpreted in evolutionary terms as indicating the times at which species originated and became extinct. Geographical regions and climatic conditions have varied throughout the Earth's history

. Since organisms are adapted to particular environments, the constantly changing conditions favoured species which adapted to new environments through the mechanism of natural selection

.

Despite the relative rarity of suitable conditions for fossilization, approximately 250,000 fossil species are known. The number of individual fossils this represents varies greatly from species to species, but many millions of fossils have been recovered: for instance, more than three million fossils from the last Ice Age

Despite the relative rarity of suitable conditions for fossilization, approximately 250,000 fossil species are known. The number of individual fossils this represents varies greatly from species to species, but many millions of fossils have been recovered: for instance, more than three million fossils from the last Ice Age

have been recovered from the La Brea Tar Pits

in Los Angeles. Many more fossils are still in the ground, in various geological formations known to contain a high fossil density, allowing estimates of the total fossil content of the formation to be made. An example of this occurs in South Africa's Beaufort Formation (part of the Karoo Supergroup

, which covers most of South Africa), which is rich in vertebrate fossils, including therapsids (reptile/mammal transitional forms

). It has been estimated that this formation contains 800 billion vertebrate fossils.

s are found that show intermediate forms in what had previously been a gap in knowledge, they are often popularly referred to as "missing links".

There is a gap of about 100 million years between the beginning of the Cambrian

period and the end of the Ordovician

period. The early Cambrian period was the period from which numerous fossils of sponges, cnidaria

ns (e.g., jellyfish

), echinoderm

s (e.g., eocrinoids), molluscs

(e.g., snail

s) and arthropod

s (e.g., trilobite

s) are found. The first animal that possessed the typical features of vertebrate

s, the Arandaspis

, was dated to have existed in the later Ordovician period. Thus few, if any, fossils of an intermediate type between invertebrate

s and vertebrates have been found, although likely candidates include the Burgess Shale

animal, Pikaia gracilens, and its Maotianshan shales

relatives, Myllokunmingia

, Yunnanozoon

, Haikouella lanceolata, and Haikouichthys

.

Some of the reasons for the incompleteness of fossil records are:

Due to an almost-complete fossil record found in North America

Due to an almost-complete fossil record found in North America

n sedimentary deposits from the early Eocene

to the present, the horse

provides one of the best examples of evolutionary history (phylogeny).

This evolutionary sequence starts with a small animal called Hyracotherium

(commonly referred to as Eohippus) which lived in North America about 54 million years ago, then spread across to Europe

and Asia

. Fossil remains of Hyracotherium show it to have differed from the modern horse in three important respects: it was a small animal (the size of a fox

), lightly built and adapted for running; the limbs were short and slender, and the feet elongated so that the digits were almost vertical, with four digits in the forelimb

s and three digits in the hindlimbs; and the incisor

s were small, the molar

s having low crowns with rounded cusp

s covered in enamel

.

The probable course of development of horses from Hyracotherium to Equus (the modern horse) involved at least 12 genera

and several hundred species

. The major trends seen in the development of the horse to changing environmental conditions may be summarized as follows:

Fossilized plants found in different strata show that the marsh

y, wooded country in which Hyracotherium lived became gradually drier. Survival now depended on the head being in an elevated position for gaining a good view of the surrounding countryside, and on a high turn of speed for escape from predators

, hence the increase in size and the replacement of the splayed-out foot by the hoofed foot. The drier, harder ground would make the original splayed-out foot unnecessary for support. The changes in the teeth can be explained by assuming that the diet changed from soft vegetation

to grass

. A dominant genus from each geological period has been selected to show the slow alteration of the horse lineage from its ancestral to its modern form.

s and island

s (biogeography

) can provide evidence of common descent and shed light on patterns of speciation

.

are capable of supporting a particular species in one geographic area, then one might assume that the same species would be found in a similar habitat in a similar geographic area, e.g. in Africa

and South America

. This is not the case. Plant and animal species are discontinuously distributed throughout the world:

Even greater differences can be found if Australia

is taken into consideration, though it occupies the same latitude

as much of South America and Africa. Marsupial

s like kangaroo

s, bandicoots, and quoll

s make up about half of Australia's indigenous mammal species. By contrast, marsupials are today totally absent from Africa and form a smaller portion of the mammalian fauna of South America, where opossums, shrew opossum

s, and the monito del monte

occur. The only living representatives of primitive egg-laying mammals (monotreme

s) are the echidna

s and the platypus

. The short-beaked echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) and its subspecies populate Australia, Tasmania

, New Guinea

, and Kangaroo Island

while the long-beaked echidna (Zaglossus bruijni) lives only in New Guinea. The platypus lives in the waters of eastern Australia. They have been introduced to Tasmania, King Island, and Kangaroo Island. These Monotremes are totally absent in the rest of the world. On the other hand, Australia is missing many groups of placental mammals that are common on other continents (carnivora

ns, artiodactyls, shrew

s, squirrel

s, lagomorphs), although it does have indigenous bat

s and murine

rodents; many other placentals, such as rabbit

s and fox

es, have been introduced there by humans.

Other animal distribution examples include bear

s, located on all continents excluding Africa, Australia and Antarctica, and the polar bear only located solely in the Arctic Circle and adjacent land masses. Penguins are located only around the South Pole despite similar weather conditions at the North Pole. Families of sirenians are distributed exclusively around the earth’s waters, where manatees are located in western Africa waters, northern South American waters, and West Indian waters only while the related family, the Dugong

s, are located only in Oceanic

waters north of Australia, and the coasts surrounding the Indian Ocean

Additionally, the now extinct Steller's Sea Cow

resided in the Bering Sea

.

The same kinds of fossils are found from areas known to be adjacent to one another in the past but which, through the process of continental drift

, are now in widely divergent geographic locations. For example, fossils of the same types of ancient amphibians, arthropods and ferns are found in South America, Africa, India, Australia and Antarctica, which can be dated to the Paleozoic

Era, at which time these regions were united as a single landmass called Gondwana

. Sometimes the descendants of these organisms can be identified and show unmistakable similarity to each other, even though they now inhabit very different regions and climates.

has played an important and historic role in the development of evolutionary biology. For purposes of biogeography

, islands are divided into two classes. Continental islands are islands like Great Britain

, and Japan

that have at one time or another been part of a continent. Oceanic islands, like the Hawaiian islands

, the Galapagos islands

and St. Helena, on the other hand are islands that have formed in the ocean and never been part of any continent. Oceanic islands have distributions of native plants and animals that are unbalanced in ways that make them distinct from the biota

s found on continents or continental islands. Oceanic islands do not have native terrestrial mammals (they do sometimes have bats and seals), amphibians, or fresh water fish. In some cases they have terrestrial reptiles (such as the iguanas and giant tortoises of the Galapagos islands) but often (for example Hawaii) they do not. This despite the fact that when species such as rats, goats, pigs, cats, mice, and cane toad

s, are introduced to such islands by humans they often thrive. Starting with Charles Darwin

, many scientists have conducted experiments and made observations that have shown that the types of animals and plants found, and not found, on such islands are consistent with the theory that these islands were colonized accidentally by plants and animals that were able to reach them. Such accidental colonization could occur by air, such as plant seeds carried by migratory birds, or bats and insects being blown out over the sea by the wind, or by floating from a continent or other island by sea, as for example by some kinds of plant seeds like coconuts that can survive immersion in salt water, and reptiles that can survive for extended periods on rafts of vegetation carried to sea by storms.

, lemurs of Madagascar

, the Komodo dragon

of Komodo

, the Dragon’s blood tree of Socotra

, Tuatara

of New Zealand, and others. However many such endemic species are related to species found on other nearby islands or continents; the relationship of the animals found on the Galapagos Islands to those found in South America is a well-known example. All of these facts, the types of plants and animals found on oceanic islands, the large number of endemic species found on oceanic islands, and the relationship of such species to those living on the nearest continents, are most easily explained if the islands were colonized by species from nearby continents that evolved into the endemic species now found there.

Other types of endemism do not have to include, in the strict sense, islands. Islands can mean isolated lakes or remote and isolated areas. Examples of these would include the highlands of Ethiopia

, Lake Baikal

, Fynbos

of South Africa

, forests of New Caledonia

, and others. Examples of endemic organisms living in isolated areas include the Kagu

of New Caledonia, cloud rat

s of the Luzon tropical pine forests

of the Philippines

, the boojum tree (Fouquieria columnaris) of the Baja California peninsula

, the Baikal Seal and the omul

of Lake Baikal.

s, members of the sunflower family on the Juan Fernandez Archipelago and wood weevils on St. Helena are called adaptive radiations because they are best explained by a single species colonizing an island (or group of islands) and then diversifying to fill available ecological niches. Such radiations can be spectacular; 800 species of the fruit fly family Drosophila

, nearly half the world's total, are endemic to the Hawaiian islands. Another illustrative example from Hawaii is the Silversword alliance

, which is a group of thirty species found only on those islands. Members range from the Silverswords that flower spectacularly on high volcanic slopes to trees, shrubs, vines and mats that occur at various elevations from mountain top to sea level, and in Hawaiian habitats that vary from deserts to rainforests. Their closest relatives outside Hawaii, based on molecular studies, are tarweeds found on the west coast of North America. These tarweeds have sticky seeds that facilitate distribution by migrant birds. Additionally, nearly all of the species on the island can be crossed and the hybrids are often fertile, and they have been hybridized experimentally with two of the west coast tarweed species as well. Continental islands have less distinct biota, but those that have been long separated from any continent also have endemic species and adaptive radiations, such as the 75 lemur

species of Madagascar

, and the eleven extinct moa

species of New Zealand

.

is an extinct species of seed fern plants from the Permian

. Glossopteris appears in the fossil record around the beginning of the Permian on the ancient continent of Gondwana

. Continental drift explains the current biogeography of the tree. Present day Glossopteris fossils are found in Permian strata in southeast South America, southeast Africa, all of Madagascar, northern India, all of Australia, all of New Zealand, and scattered on the southern and northern edges of Antarctica. During the Permian, these continents were connected as Gondwana (see figure 6a) in agreement with magnetic striping, other fossil distributions, and glacial scratches pointing away from the temperate climate of the South Pole during the Permian.

and that they were connected by land that is now part of Antarctica. Therefore combining the two theories scientists predicted that marsupials migrated from what is now South America across what is now Antarctica to what is now Australia between 40 and 30 million years ago. This hypothesis led paleontologists to Antarctica to look for marsupial fossils of the appropriate age. After years of searching they found, starting in 1982, fossils on Seymour Island

off the coast of the Antarctic Peninsula

of more than a dozen marsupial species that lived 35-40 million years ago.

provides an example of how fossil evidence can be used to reconstruct migration and subsequent evolution. The fossil record indicates that the evolution of camelid

s started in North America (see figure 6c), from which 6 million years ago they migrated across the Bering Strait into Asia and then to Africa, and 3.5 million years ago through the Isthmus of Panama into South America. Once isolated, they evolved along their own lines, giving rise to the Bactrian camel

and Dromedary

in Asia and Africa and the llama and its relatives

in South America. Camelids then went extinct in North America at the end of the last ice age

.

in the field and the laboratory. Scientists have observed and documented a multitude of events where natural selection is in action. The most well known examples are antibiotic resistance in the medical field along with better-known laboratory experiments documenting evolution's occurrence. Natural selection is tantamount to common descent in the fact that long-term occurrence and selection pressures can lead to the diversity of life on earth as found today. All adaptations—documented and undocumented changes concerned—are caused by natural selection (and a few other minor processes). The examples below are only a small fraction of the actual experiments and observations.

, like the spread of pesticide

resistant forms of plants and insects is evidence for evolution of species, and of change within species. Thus the appearance of vancomycin

resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and the danger it poses to hospital patients is a direct result of evolution through natural selection. The rise of Shigella

strains resistant to the synthetic antibiotic class of sulfonamides also demonstrates the generation of new information as an evolutionary process. Similarly, the appearance of DDT

resistance in various forms of Anopheles

mosquitoes, and the appearance of myxomatosis

resistance in breeding rabbit populations in Australia, are all evidence of the existence of evolution in situations of evolutionary selection pressure in species in which generations occur rapidly.

set up an experiment shortly before 1880, subjecting microbes to heat with the aim of forcing adaptive changes. His experiment ran for around seven years, and his published results were acclaimed, but he did not resume the experiment after the apparatus failed.

The E. coli long-term evolution experiment that began in 1988 under the leadership of Richard Lenski

is still in progress, and has shown adaptations including the evolution of a strain of E. coli that was able to grow on citric acid in the growth media.

has significant over-representation of an immune variant of the prion protein gene G127V versus non-immune alleles. Scientists postulate one of the reasons for the rapid selection of this genetic variant is the lethality of the disease in non-immune persons. Other reported evolutionary trends in other populations include a lengthening of the reproductive period, reduction in cholesterol levels, blood glucose and blood pressure.

is the inability to metabolize

lactose

, because of a lack of the required enzyme lactase

in the digestive system. The normal mammalian condition is for the young of a species to experience reduced lactase

production at the end of the weaning

period (a species-specific length of time). In humans, in non-dairy consuming societies, lactase production usually drops about 90% during the first four years of life, although the exact drop over time varies widely. However, certain human populations have a mutation on chromosome 2 which eliminates the shutdown in lactase production, making it possible for members of these populations to continue consumption of raw milk and other fresh and fermented dairy products throughout their lives without difficulty. This appears to be an evolutionarily recent adaptation to dairy consumption, and has occurred independently in both northern Europe and east Africa in populations with a historically pastoral lifestyle.

are a strain of Flavobacterium

that is capable of digesting certain byproducts of nylon 6

manufacture. There is scientific consensus that the capacity to synthesize nylonase most probably developed as a single-step mutation that survived because it improved the fitness of the bacteria possessing the mutation. This is seen as a good example of evolution through mutation and natural selection that has been observed as it occurs.

dumped polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in the Hudson River

from 1947 through 1976, tomcods living in the river were found to have evolved an increased resistance to the compound's toxic effects. At first the tomcod population was devastated, but it recovered. Scientists identified the genetic mutation that conferred the resistance. The mutated form was found to be present in 99 per cent of the surviving tomcods in the river, compared to fewer than 10 percent of the tomcods from other waters.

in England.

to convert gamma radiation into chemical energy for growth and were first discovered in 2007 as black molds growing inside and around the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant

. Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine

showed that three melanin-containing fungi, Cladosporium sphaerospermum, Wangiella dermatitidis, and Cryptococcus neoformans

, increased in biomass

and accumulated acetate

faster in an environment in which the radiation

level was 500 times higher than in the normal environment.

is wildlife

that is able to live or thrive in urban

environments. These types of environments can exert selection pressures on organism, often leading to new adaptations. For example, the weed Crepis sancta

, found in France, has two types of seed, heavy and fluffy. The heavy ones land nearby to the parent plant, whereas the fluffy seeds float further away on the wind. In urban environments, seeds that float far will often land on infertile concrete. Within about 5-12 generations, the weed has been found to evolve to produce significantly more heavy seeds than its rural relatives do. Other examples of urban wildlife are rock pigeon

s and species of crows adapting to city environments around the world; African penguins in Simons Town; baboon

s in South Africa

; and a variety of insects living in human habitations.

is the evolutionary process by which new biological species arise. Speciation can occur from a variety of different causes and are classified in various forms (e.g. allopatric, sympatric, polyploidization, etc.). Scientists have observed numerous examples of speciation in the laboratory and in nature, however, evolution has produced far more species than an observer would consider necessary. For example, there are well over 350,000 described species of beetles. Great examples of observed speciation come from the observations of island biogeography and the process of adaptive radiation, both explained in an earlier section. The examples shown below provide strong evidence for common descent and are only a small fraction of the instances observed.

, commonly referred to as Blackcaps, lives in Germany and flies southwest to Spain while a smaller group flies northwest to Great Britain during the winter. Gregor Rolshausen from the University of Freiburg

found that the genetic separation of the two populations is already in progress. The differences found have arisen in about 30 generations. With DNA sequencing, the individuals can be assigned to a correct group with an 85% accuracy. Stuart Bearhop from the University of Exeter

reported that birds wintering in England tend to mate only among themselves, and not usually with those wintering in the Mediterranean. It is still inference to say that the populations will become two different species, but researchers expect it due to the continued genetic and geographic separation.

.jpg) William R. Rice and George W. Salt found experimental evidence of sympatric speciation

William R. Rice and George W. Salt found experimental evidence of sympatric speciation

in the common fruit fly

. They collected a population of Drosophila melanogaster from Davis, California

and placed the pupae into a habitat maze. Newborn flies had to investigate the maze to find food. The flies had three choices to take in finding food. Light and dark (phototaxis

), up and down (geotaxis), and the scent of acetaldehyde

and the scent of ethanol (chemotaxis

) were the three options. This eventually divided the flies into 42 spatio-temporal habitats.

They then cultured two strains that chose opposite habitats. One of the strains emerged early, immediately flying upward in the dark attracted to the acetaldehyde

. The other strain emerged late and immediately flew downward, attracted to light and ethanol. Pupae from the two strains were then placed together in the maze and allowed to mate at the food site. They then were collected. A selective penalty was imposed on the female flies that switched habitats. This entailed that none of their gametes would pass on to the next generation. After 25 generations of this mating test, it showed reproductive isolation between the two strains. They repeated the experiment again without creating the penalty against habitat switching and the result was the same; reproductive isolation was produced.

. Different populations of hawthorn fly feed on different fruits. A distinct population emerged in North America in the 19th century some time after apple

s, a non-native species, were introduced. This apple-feeding population normally feeds only on apples and not on the historically preferred fruit of hawthorns

. The current hawthorn feeding population does not normally feed on apples. Some evidence, such as the fact that six out of thirteen allozyme

loci are different, that hawthorn flies mature later in the season and take longer to mature than apple flies; and that there is little evidence of interbreeding (researchers have documented a 4-6% hybridization rate) suggests that speciation is occurring.

is a species of mosquito

in the genus Culex

found in the London Underground

. It evolved from the overground species Culex pipiens.

This mosquito, although first discovered in the London Underground system, has been found in underground systems around the world. It is suggested that it may have adapted to human-made underground systems since the last century from local above-ground Culex pipiens, although more recent evidence suggests that it is a southern mosquito variety related to Culex pipiens that has adapted to the warm underground spaces of northern cities.

The species have very different behaviours, are extremely difficult to mate, and with different allele frequency, consistent with genetic drift during a founder event. More specifically, this mosquito, Culex pipiens molestus, breeds all-year round, is cold intolerant, and bites rats, mice, and humans, in contrast to the above ground species Culex pipiens that is cold tolerant, hibernates in the winter, and bites only birds. When the two varieties were cross-bred the eggs were infertile suggesting reproductive isolation.

The fundamental results still stands: the genetic data indicate that the molestus form in the London Underground mosquito appeared to have a common ancestry, rather than the population at each station being related to the nearest above-ground population (i.e. the pipiens form). Byrne and Nichols' working hypothesis was that adaptation to the underground environment had occurred locally in London once only.

These widely separated populations are distinguished by very minor genetic differences, which suggest that the molestus form developed: a single mtDNA difference shared among the underground populations of ten Russian cities; a single fixed microsatellite difference in populations spanning Europe, Japan, Australia, the middle East and Atlantic islands.

—is a small fish that lives in the Sulfur Caves

of Mexico. Michael Tobler from the Texas A&M University

has studied the fish for years and found that two distinct populations of mollies—the dark interior fish and the bright surface water fish—are becoming more genetically divergent. The populations have no obvious barrier separating the two; however, it was found that the mollies are hunted by a large water bug (Belostoma spp). Tobler collected the bug and both types of mollies, placed them in large plastic bottles, and put them back in the cave. After a day, it was found that, in the light, the cave-adapted fish endured the most damage, with four out of every five stab-wounds from the water bugs sharp mouthparts. In the dark, the situation was the opposite. The mollies’ senses can detect a predator’s threat in their own habitats, but not in the other ones. Moving from one habitat to the other significantly increases the risk of dying. Tobler plans on further experiments, but believes that it is a good example of the rise of a new species.

Kirsten Bomblies

Kirsten Bomblies

et al. from the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology

discovered that two genes passed down by each parent of the thale cress plant, Arabidopsis thaliana

. When the genes are passed down, it ignites a reaction in the hybrid plant that turns its own immune system against it. In the parents, the genes were not detrimental, but they evolved separately to react defectively when combined.

To test this, Bomblies crossed 280 genetically different strains of Arabidopsis in 861 distinct ways and found that 2 per cent of the resulting hybrids were necrotic. Along with allocating the same indicators, the 20 plants also shared a comparable collection of genetic activity in a group of 1,080 genes. In almost all of the cases, Bomblies discovered that only two genes were required to cause the autoimmune response. Bomblies looked at one hybrid in detail and found that one of the two genes belonged to the NB-LRR class

, a common group of disease resistance genes involved in recognizing new infections. When Bomblies removed the problematic gene, the hybrids developed normally.

Over successive generations, these incompatibilities could create divisions between different plant strains, reducing their chances of successful mating and turning distinct strains into separate species.

(Ursus maritimus). The polar bear is related to the brown bear

(Ursus arctos) but they can still interbreed and produce fertile offspring. However, it has acquired significant physiological differences from the brown bear. These differences allow the polar bear to comfortably survive in conditions that the brown bear could not including the ability to swim sixty miles or more at a time in freezing waters, to blend in with the snow, and to stay warm in the arctic environment. Additionally, the elongation of the neck makes it easier to keep their heads above water while swimming and the oversized webbed feet that act as paddles when swimming. The polar bear has also evolved small papillae and vacuole-like suction cups on the soles to make them less likely to slip on the ice; feet covered with heavy matting to protect the bottoms from intense cold and provide traction; smaller ears to reduce the loss of heat; eyelids that act like sunglasses; accommodations for their all-meat diet; a large stomach capacity to enable opportunistic feeding; and the ability to fast for up to nine months while recycling their urea.

includes all intergeneric hybrids between the genera Raphanus

(radish) and Brassica

(cabbages, etc.).

The Raphanobrassica is an allopolyploid cross between the radish

(Raphanus sativus) and cabbage

(Brassica oleracea). Plants of this parentage are now known as radicole. Two other fertile forms of Raphanobrassica are known. Raparadish, an allopolyploid hybrid between Raphanus sativus and Brassica rapa is grown as a fodder crop. "Raphanofortii" is the allopolyploid hybrid between Brassica tournefortii

and Raphanus caudatus.

The Raphanobrassica is a fascinating plant, because (in spite of its hybrid nature), it is not sterile. This has led some botanists to propose that the accidental hybridization of a flower by pollen of another species in nature could be a mechanism of speciation common in higher plants.

are one example where hybrid speciation

has been observed. In the early 20th century, humans introduced three species of goatsbeard into North America. These species, the western salsify (Tragopogon dubius), the meadow salsify (Tragopogon pratensis), and the oyster plant (Tragopogon porrifolius), are now common weeds in urban wastelands. In the 1950s, botanists found two new species in the regions of Idaho

and Washington, where the three already known species overlapped. One new species, Tragopogon miscellus, is a tetraploid hybrid of T. dubius and T. pratensis. The other new species, Tragopogon mirus, is also an allopolyploid, but its ancestors were T. dubius and T. porrifolius. These new species are usually referred to as "the Ownbey hybrids" after the botanist who first described them. The T. mirus population grows mainly by reproduction of its own members, but additional episodes of hybridization continue to add to the T. mirus population.

T. dubius and T. pratensis mated in Europe but were never able to hybridize. A study published in March 2011 found that when these two plants were introduced to North America in the 1920s, they mated and doubled the number of chromosomes in there hybrid Tragopogon miscellus allowing for a “reset” of its genes, which in turn, allows for greater genetic variation. Professor Doug Soltis of the University of Florida

said, “We caught evolution in the act…New and diverse patterns of gene expression may allow the new species to rapidly adapt in new environments”. This observable event of speciation through hybridization further advances the evidence for the common descent of organisms and the time frame in which the new species arose in its new environment. The hybridizations have been reproduced artificially in laboratories from 2004 to present day.

) grow alongside each other. Sometime in the early 20th century, an accidental doubling of the number of chromosomes in an S. × baxteri plant led to the formation of a new fertile species.

Senecio squalidus

(also known as Oxford ragwort) and the self-compatible Senecio vulgaris (also known as Common groundsel). Like S. vulgaris, S. eboracensis is self-compatible, however, it shows little or no natural crossing with its parent species, and is therefore reproductively isolated, indicating that strong breed barriers exist between this new hybrid and its parents.

It resulted from a backcrossing

of the F1 hybrid

of its parents to S. vulgaris. S. vulgaris is native to Britain, while S. squalidus was introduced from Sicily in the early 18th century; therefore, S. eboracensis has speciated from those two species within the last 300 years.

Other hybrids descended from the same two parents are known. Some are infertile, such as S. x baxteri. Other fertile hybrids are also known, including S. vulgaris var. hibernicus, now common in Britain, and the allohexaploid

S. cambrensis

, which according to molecular evidence probably originated independently at least three times in different locations. Morphological and genetic evidence support the status of S. eboracensis as separate from other known hybrids.

demonstrates the diversity that can exist among organisms that share a relatively recent common ancestor. In artificial selection, one species is bred selectively at each generation, allowing only those organisms that exhibit desired characteristics to reproduce. These characteristics become increasingly well developed in successive generations. Artificial selection was successful long before science discovered the genetic basis. Examples of artificial selection would be dog breeding

, genetically modified food

, flower breeding, cultivation of foods such as wild cabbage

, and others.

allows the iteration

of self changing complex system

s to be studied, allowing a mathematical understanding of the nature of the processes behind evolution; providing evidence for the hidden causes of known evolutionary events. The evolution of specific cellular mechanisms like spliceosome

s that can turn the cell's genome into a vast workshop of billions of interchangeable parts that can create tools that create tools that create tools that create us can be studied for the first time in an exact way.

"It has taken more than five decades, but the electronic computer is now powerful enough to simulate evolution" assisting bioinformatics

in its attempt to solve biological problems.

Computational evolutionary biology has enabled researchers to trace the evolution of a large number of organisms by measuring changes in their DNA, rather than through physical taxonomy or physiological observations alone. It has compared entire genomes permitting the study of more complex evolutionary events, such as gene duplication

, horizontal gene transfer

, and the prediction of factors important in speciation. It has also helped build complex computational models of populations to predict the outcome of the system over time and track and share information on an increasingly large number of species and organisms.

Future endeavors are to reconstruct a now more complex tree of life.

Christoph Adami, a professor at the Keck Graduate Institute made this point in Evolution of biological complexity:

David J. Earl and Michael W. Deem—professors at Rice University

made this point in Evolvability is a selectable trait:

"Computer simulations of the evolution of linear sequences have demonstrated the importance of recombination of blocks of sequence rather than point mutagenesis alone. Repeated cycles of point mutagenesis, recombination, and selection should allow in vitro molecular evolution of complex sequences, such as proteins." Evolutionary molecular engineering, also called directed evolution or in vitro molecular evolution involves the iterated cycle of mutation, multiplication with recombination, and selection of the fittest of individual molecules (proteins, DNA, and RNA). Natural evolution can be relived showing us possible paths from catalytic cycles based on proteins to based on RNA to based on DNA.

developed an artificial life

computer program with the ability to detail the evolution of complex systems. The system uses values set to determine random mutations and allows for the effect of natural selection to conserve beneficial traits. The program was dubbed Avida and starts with an artificial petri dish where organisms reproduce and perform mathematical calculations to acquire rewards of more computer time for replication. The program randomly adds mutations to copies of the artificial organisms to allow for natural selection. As the artificial life reproduced, different lines adapted and evolved depending on their set environments. The beneficial side to the program is that it parallels that of real life at rapid speeds.

Evolution

Evolution is any change across successive generations in the heritable characteristics of biological populations. Evolutionary processes give rise to diversity at every level of biological organisation, including species, individual organisms and molecules such as DNA and proteins.Life on Earth...

and provided a wealth of information on the natural processes by which the variety and diversity of life on Earth developed. This evidence supports the modern evolutionary synthesis

Modern evolutionary synthesis

The modern evolutionary synthesis is a union of ideas from several biological specialties which provides a widely accepted account of evolution...

, the current scientific theory

Scientific theory

A scientific theory comprises a collection of concepts, including abstractions of observable phenomena expressed as quantifiable properties, together with rules that express relationships between observations of such concepts...

that explains how and why life changes over time. Evolutionary biologists document the fact of common descent

Common descent

In evolutionary biology, a group of organisms share common descent if they have a common ancestor. There is strong quantitative support for the theory that all living organisms on Earth are descended from a common ancestor....

: making testable predictions, testing hypotheses, and developing theories that illustrate and describe its causes.

Comparison of the genetic sequence

DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing includes several methods and technologies that are used for determining the order of the nucleotide bases—adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine—in a molecule of DNA....

of organisms has revealed that organisms that are phylogenetically

Phylogenetics

In biology, phylogenetics is the study of evolutionary relatedness among groups of organisms , which is discovered through molecular sequencing data and morphological data matrices...

close have a higher degree of sequence similarity than organisms that are phylogenetically distant. Further evidence for common descent comes from genetic detritus such as pseudogene

Pseudogene

Pseudogenes are dysfunctional relatives of known genes that have lost their protein-coding ability or are otherwise no longer expressed in the cell...

s, regions of DNA

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a nucleic acid that contains the genetic instructions used in the development and functioning of all known living organisms . The DNA segments that carry this genetic information are called genes, but other DNA sequences have structural purposes, or are involved in...

that are orthologous to a gene in a related organism

Organism

In biology, an organism is any contiguous living system . In at least some form, all organisms are capable of response to stimuli, reproduction, growth and development, and maintenance of homoeostasis as a stable whole.An organism may either be unicellular or, as in the case of humans, comprise...

, but are no longer active and appear to be undergoing a steady process of degeneration.

Fossils are important for estimating when various lineages developed in geologic time. As fossilization is an uncommon occurrence, usually requiring hard body parts and death near a site where sediment

Sediment

Sediment is naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of fluids such as wind, water, or ice, and/or by the force of gravity acting on the particle itself....

s are being deposited, the fossil record only provides sparse and intermittent information about the evolution of life. Evidence

Scientific evidence

Scientific evidence has no universally accepted definition but generally refers to evidence which serves to either support or counter a scientific theory or hypothesis. Such evidence is generally expected to be empirical and properly documented in accordance with scientific method such as is...

of organisms prior to the development of hard body parts such as shells, bones and teeth is especially scarce, but exists in the form of ancient microfossils, as well as impressions of various soft-bodied organisms. The comparative study of the anatomy

Anatomy

Anatomy is a branch of biology and medicine that is the consideration of the structure of living things. It is a general term that includes human anatomy, animal anatomy , and plant anatomy...

of groups of animals shows structural features that are fundamentally similar or homologous, demonstrating phylogenetic and ancestral relationships with other organism, most especially when compared with fossils of ancient extinct

Extinction

In biology and ecology, extinction is the end of an organism or of a group of organisms , normally a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and recover may have been lost before this point...

organisms. Vestigial structures and comparisons in embryonic development

Embryogenesis

Embryogenesis is the process by which the embryo is formed and develops, until it develops into a fetus.Embryogenesis starts with the fertilization of the ovum by sperm. The fertilized ovum is referred to as a zygote...

are largely a contributing factor in anatomical resemblance in concordance with common descent. Since metabolic

Metabolism

Metabolism is the set of chemical reactions that happen in the cells of living organisms to sustain life. These processes allow organisms to grow and reproduce, maintain their structures, and respond to their environments. Metabolism is usually divided into two categories...

processes do not leave fossils, research into the evolution of the basic cellular processes is done largely by comparison of existing organisms’ physiology

Physiology

Physiology is the science of the function of living systems. This includes how organisms, organ systems, organs, cells, and bio-molecules carry out the chemical or physical functions that exist in a living system. The highest honor awarded in physiology is the Nobel Prize in Physiology or...

and biochemistry

Biochemistry

Biochemistry, sometimes called biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes in living organisms, including, but not limited to, living matter. Biochemistry governs all living organisms and living processes...

. Many lineages diverged at different stages of development, so it is possible to determine when certain metabolic processes appeared by comparing the traits of the descendants of a common ancestor. Universal biochemical organization and molecular variance patterns in all organisms also show a direct correlation with common descent.

Further evidence comes from the field of biogeography

Biogeography

Biogeography is the study of the distribution of species , organisms, and ecosystems in space and through geological time. Organisms and biological communities vary in a highly regular fashion along geographic gradients of latitude, elevation, isolation and habitat area...

because evolution with common descent provides the best and most thorough explanation for a variety of facts concerning the geographical distribution of plants and animals across the world. This is especially obvious in the field of island biogeography

Island biogeography

Island biogeography is a field within biogeography that attempts to establish and explain the factors that affect the species richness of natural communities. The theory was developed to explain species richness of actual islands...

. Combined with the theory of plate tectonics

Plate tectonics

Plate tectonics is a scientific theory that describes the large scale motions of Earth's lithosphere...

common descent provides a way to combine facts about the current distribution of species with evidence from the fossil record to provide a logically consistent explanation of how the distribution of living organisms has changed over time.

The development and spread of antibiotic resistant

Antibiotic resistance

Antibiotic resistance is a type of drug resistance where a microorganism is able to survive exposure to an antibiotic. While a spontaneous or induced genetic mutation in bacteria may confer resistance to antimicrobial drugs, genes that confer resistance can be transferred between bacteria in a...

bacteria, like the spread of pesticide resistant forms of plants and insects provides evidence that evolution due to natural selection

Natural selection

Natural selection is the nonrandom process by which biologic traits become either more or less common in a population as a function of differential reproduction of their bearers. It is a key mechanism of evolution....

is an ongoing process in the natural world. Alongside this, are observed instances of the separation of populations of species into sets of new species (speciation

Speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which new biological species arise. The biologist Orator F. Cook seems to have been the first to coin the term 'speciation' for the splitting of lineages or 'cladogenesis,' as opposed to 'anagenesis' or 'phyletic evolution' occurring within lineages...

). Speciation has been observed directly and indirectly in the lab and in nature. Multiple forms of such have been described and documented as examples for individual modes of speciation. Furthermore, evidence of common descent extends from direct laboratory experimentation with the artificial selection of organisms—historically and currently—and other controlled experiments involving many of the topics in the article. This article explains the different types of evidence for evolution with common descent along with many specialized examples of each.

Evidence from comparative physiology and biochemistry

Genetics

Sequence alignment

In bioinformatics, a sequence alignment is a way of arranging the sequences of DNA, RNA, or protein to identify regions of similarity that may be a consequence of functional, structural, or evolutionary relationships between the sequences. Aligned sequences of nucleotide or amino acid residues are...

examines the relationship between the DNA sequences of different species, producing several lines of evidence that confirm Darwin's original hypothesis of common descent. If the hypothesis of common descent is true, then species that share a common ancestor will have inherited that ancestor's DNA sequence. They will have inherited mutations unique to that ancestor. More closely related species will have a greater fraction of identical sequence and will have shared substitutions when compared to more distantly related species.

The simplest and most powerful evidence is provided by phylogenetic reconstruction

Computational phylogenetics

Computational phylogenetics is the application of computational algorithms, methods and programs to phylogenetic analyses. The goal is to assemble a phylogenetic tree representing a hypothesis about the evolutionary ancestry of a set of genes, species, or other taxa...

. Such reconstructions, especially when done using slowly evolving protein sequences, are often quite robust and can be used to reconstruct a great deal of the evolutionary history of modern organisms (and even in some instances such as the recovered gene sequences of mammoth

Mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct genus Mammuthus. These proboscideans are members of Elephantidae, the family of elephants and mammoths, and close relatives of modern elephants. They were often equipped with long curved tusks and, in northern species, a covering of long hair...

s, Neanderthal

Neanderthal

The Neanderthal is an extinct member of the Homo genus known from Pleistocene specimens found in Europe and parts of western and central Asia...

s or T. rex

Tyrannosaurus

Tyrannosaurus meaning "tyrant," and sauros meaning "lizard") is a genus of coelurosaurian theropod dinosaur. The species Tyrannosaurus rex , commonly abbreviated to T. rex, is a fixture in popular culture. It lived throughout what is now western North America, with a much wider range than other...

, the evolutionary history of extinct organisms). These reconstructed phylogenies recapitulate the relationships established through morphological and biochemical studies. The most detailed reconstructions have been performed on the basis of the mitochondrial genomes shared by all eukaryotic

Eukaryote

A eukaryote is an organism whose cells contain complex structures enclosed within membranes. Eukaryotes may more formally be referred to as the taxon Eukarya or Eukaryota. The defining membrane-bound structure that sets eukaryotic cells apart from prokaryotic cells is the nucleus, or nuclear...

organisms, which are short and easy to sequence; the broadest reconstructions have been performed either using the sequences of a few very ancient proteins or by using ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid is the RNA component of the ribosome, the enzyme that is the site of protein synthesis in all living cells. Ribosomal RNA provides a mechanism for decoding mRNA into amino acids and interacts with tRNAs during translation by providing peptidyl transferase activity...

sequence.

Phylogenetic relationships also extend to a wide variety of nonfunctional sequence elements, including repeats, transposons, pseudogenes, and mutations in protein-coding sequences that do not result in changes in amino-acid sequence. While a minority of these elements might later be found to harbor function, in aggregate they demonstrate that identity must be the product of common descent rather than common function.

Universal biochemical organisation and molecular variance patterns

All known extant organisms are based on the same fundamental biochemical organisation: genetic information encoded as nucleic acid (DNADNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid is a nucleic acid that contains the genetic instructions used in the development and functioning of all known living organisms . The DNA segments that carry this genetic information are called genes, but other DNA sequences have structural purposes, or are involved in...

, or RNA

RNA