History of democracy

Encyclopedia

The history of democracy traces back to Athens

to its re-emergence and rise from the 17th century to the present day. According to one definition, democracy

is a political system

in which all the members of the society have an equal share of formal political power

. In modern representative democracy

, this formal equality is embodied primarily in the right to vote.

Within this broad sense it is plausible to assume that democracy in one form or another arises naturally in any well-bonded group, such as a tribe

. This is tribalism

or primitive democracy. A primitive democracy is identified in small communities or villages when the following take place: face-to-face discussion in the village council or a headman whose decisions are supported by village elders or other cooperative modes of government.

Nevertheless, on larger scale sharper contrasts arise when the village and the city are examined as political communities. In urban governments, all other forms of rule – monarchy

, tyranny, aristocracy

, and oligarchy

– have flourished.

developed its complex social and political institutions long after the appearance of the earliest civilizations in Egypt

and the Near East

.

Thorkild Jacobsen

Thorkild Jacobsen

has studied the pre-Babylonian Mesopotamia and uses Sumer

ian epic, myth and historical records to identify what he calls primitive democracy. By this he means a government in which ultimate power rests with the mass of free male citizens, although "the various functions of government are as yet little specialized, the power structure is loose". In the early period of Sumer, kings such as Gilgamesh

did not hold the autocratic

power which later Mesopotamia rulers wielded. Rather, major city-state

s had a council of elders and a council of "young men" (likely to be comprised by free men bearing arms) that possessed the final political authority, and had to be consulted on all major issues such as war.

This pioneering work, while constantly cited, has invoked little serious discussion and less outright acceptance. The criticism from other scholars focuses on the use of the word "democracy", since the same evidence also can be interpreted convincingly to demonstrate a power struggle between primitive monarchs and the nobility, a struggle in which the common people act more as pawns than the sovereign authority. Jacobsen concedes that the vagueness of the evidence prohibits the separation between the Mesopotamian democracy from a primitive oligarchy.

s and gana

s, which existed as early as the sixth century BCE and persisted in some areas until the fourth century CE. The evidence is scattered and no pure historical source exists for that period. In addition, Diodorus (a Greek historian writing two centuries after the time of Alexander the Great's invasion of India), without offering any detail, mentions that independent and democratic states existed in India. However, modern scholars note that the word democracy at the third century BC and later had been degraded and could mean any autonomous state no matter how oligarchic it was.

The main characteristics of the gana seem to be a monarch, usually called raja

and a deliberative assembly. The assembly met regularly in which at least in some states attendance was open to all free men, and discussed all major state decisions. It had also full financial, administrative, and judicial authority. Other officers, who are rarely mentioned, obeyed the decisions of the assembly. The monarch was elected by the gana and apparently he always belonged to a family of the noble K'satriya

Varna. The monarch coordinated his activities with the assembly and in some states along with a council of other nobles. The Licchavis

had a primary governing body of 7,077 rajas, the heads of the most important families. On the other hand, the Shakya

s, the Gautama Buddha

's people, had the assembly open to all men, rich and poor.

Scholars differ over how to describe these governments and the vague, sporadic quality of the evidence allows for wide disagreements. Some emphasize the central role of the assemblies and thus tout them as democracies; other scholars focus on the upper class domination of the leadership and possible control of the assembly and see an oligarchy

or an aristocracy

. Despite the obvious power of the assembly, it has not yet been established if the composition and participation was truly popular. The first main obstacle is the lack of evidence describing the popular power of the assembly. This is reflected in the Artha' shastra

, an ancient handbook for monarchs on how to rule efficiently. It contains a chapter on dealing with the sangas, which includes injunctions on manipulating the noble leaders, yet it does not mention how to influence the mass of the citizens – a surprising omission if democratic bodies, not the aristocratic families, actively controlled the republican governments. Another issue is the persistence of the four-tiered Varna class system. The duties and privileges on the members of each particular caste – which were rigid enough to prohibit someone sharing a meal with those of another order – might have affected the role members were expected to play in the state, regardless of the formal institutions. The lack of the concept of citizen equality across caste system boundaries lead many scholars to believe that the true nature of ganas and sanghas would not be comparable to that of truly democratic institutions.

Ancient Greece, in its early period, was a loose collection of independent city states called poleis. Many of these poleis were oligarchies. The most prominent Greek oligarchy

Ancient Greece, in its early period, was a loose collection of independent city states called poleis. Many of these poleis were oligarchies. The most prominent Greek oligarchy

, and the state with which democratic Athens is most often and most fruitfully compared, was Sparta. Yet Sparta, in its rejection of private wealth as a primary social differentiator, was a peculiar kind of oligarchy and some scholars note its resemblance to democracy. In Spartan government, the political power was divided between four bodies: two Spartan Kings

(monarchy), gerousia

(Counsil of Gerontes (Elders), including the two kings), the ephors (representatives who oversaw the Kings) and the apella

(assembly of Spartans).

The two kings served as the head of the government. They ruled simultaneously but came from two separate lines. The dual kingship diluted the effective power of the executive office. The kings shared their judicial functions with other members of the gerousia. The members of the gerousia had to be over the age of 60 and were elected for life. In theory, any Spartan over that age could stand for election. However, in practice, they were selected from wealthy, aristocratic families. The gerousia possessed the crucial power of legislative initiative. Apella, the most democratic element, was the assembly where Spartans above the age of 30 elected the members of the gerousia and the ephors, and accepted or rejected gerousia's proposals. Finally, the five ephors were Spartans chosen in apella to oversee the actions of the kings and other public officials and, if necessary, depose them. They served for one year and could not be re-elected for a second time. Over the years the ephors held great influence into forming foreign policy and acted as the main executive body of state. Additionally, they had full responsibility of the Spartan educational system, which was essential for maintaining the high standards of the Spartan army. As Aristotle

noted, ephors were the most important key institution of state, but because often they were appointed from the whole social body it resulted in very poor men holding office, with the ensuing possibility that they could easily be bought.

The creator of the Spartan system of rule was the legendary lawgiver Lycurgus

. He is associated with the drastic reforms that were instituted in Sparta after the revolt of the helots

in the second half of the 7th century BC. In order to prevent another helot revolt, Lycurgus devised the highly militarized communal system that made Sparta unique among the city-states of Greece. All his reforms were directed towards the three Spartan virtues: equality (among citizens), military fitness and austerity. It is also probable that Lycurgus delineated the powers of the two traditional organs of the Spartan government, the gerousia

and the apella

.

The reforms of Lycurgus were written as a list of rules/laws called Great Rhetra

; making it the world's first written constitution. In the following centuries Sparta became a military superpower, and its system of rule was admired throughout the Greek world for its political stability. In particular, the concept of equality played an important role in Spartan society. The Spartans referred to themselves as όμοιοι (Homoioi, men of equal status). It was also reflected in the Spartan public educational system, agoge

, where all citizens irrespective of wealth or status had the same education. This was admired almost universally by contemporaries, from historians such as Herodotus

and Xenophon

to philosophers such as Plato

and Aristotle. In addition, the Spartan women, unlike elsewhere, enjoyed "every kind of luxury and intemperance" including elementary rights such as the right to inheritance, property ownership and public education. Overall the Spartans were remarkably free to criticize their kings and they were able to depose and exile them. However, despite these democratic elements in the Spartan constitution, there are two cardinal criticisms, classifying Sparta as an oligarchy. First, individual freedom was restricted, since as Plutarch

writes "no man was allowed to live as he wished", but as in a "military camp" all were engaged in the public service of their polis. And second, the gerousia effectively maintained the biggest share of power of the various governmental bodies.

The political stability of Sparta also meant that no significant changes in the constitution were made. The oligarchic elements of Sparta became even stronger, especially after the influx of gold and silver from the victories in the Persian Wars. In addition, Athens, after the Persian Wars, was becoming the hegemonic power in the Greek world and disagreements between Sparta and Athens over supremacy emerged. These lead to a series of armed conflicts known as the Peloponnesian War

, with Sparta prevailing in the end. However, the war exhausted both poleis and Sparta was in turn humbled by Thebes

at the Battle of Leuctra

in 371 BC. It was all brought to an end a few years later, when Philip II of Macedon

crushed what remained of the power of the factional city states to his South.

Athens emerged in the 7th century BC, like many other poleis, with a dominating powerful aristocracy. However, this domination led to exploitation causing significant economic, political, and social problems. These problems were enhanced early in the sixth century and as "the many were enslaved to few, the people rose against the notables". At the same period in the Greek world many traditional aristocracies were disrupted by popular revolutions, like Sparta in the second half of the 7th century BC. Sparta's constitutional reforms by Lycurgus introduced a hoplite

state and showed how inherited governments can be changed and lead to military victory. After a period of unrest between the rich and the poor, the Athenians of all classes turned to Solon

for acting as a mediator between rival factions, and reaching to a generally satisfactory solution of their problems.

poet and later a lawmaker; Plutarch placed him as one of the Seven Sages

of the ancient world. Solon attempted to satisfy all sides by alleviating the suffering of the poor majority without removing all the privileges of the rich minority.

Solon divided the Athenians, into four property classes, with different rights and duties for each. As the Rhetra did in the Lycurgian Sparta, Solon formalized the composition and functions of the governmental bodies. Now, all citizens were entitled to attend the Ecclesia

(Assembly) and vote. Ecclesia became, in principle, the sovereign body, entitled to pass laws and decrees, elect officials, and hear appeals from the most important decisions of the court

s. All but those in the poorest group might serve, a year at a time, on a new Boule of 400

, which was to prepare business for Ecclesia. The higher governmental posts, archons (magistrates), were reserved for citizens of the top two income groups. The retired archons were becoming members of Areopagus

(Council of the Hill of Ares), and like Gerousia in Sparta, it was able to check improper actions of the newly powerful Ecclesia. Solon created a mixed timocratic

and democratic

system of institutions.

Overall, the reforms of the lawgiver Solon in 594 BC, devised to avert the political, economic and moral decline in archaic Athens and gave Athens its first comprehensive code of law. The constitutional reforms eliminated enslavement of Athenians by Athenians, established rules for legal redress against over-reaching aristocratic archons, and assigned political privileges on the basis of productive wealth rather than noble birth. Some of his reforms failed in the short term, yet he is often credited with having laid the foundations for Athenian democracy.

became tyrant

of Athens three times and remained in power until his death in 527 BC. His sons Hippias

and Hipparchus

succeeded him.

After the fall of tyranny and before the year 508–507 was over, Cleisthenes

proposed a complete reform of the system of government, which later was approved by the popular Ecclesia

. Cleisthenes reorganized the population into ten tribes, with the aim to change the basis of political organization from the family loyalties to political ones, and improve the army's organization. He also introduced the principle of equality of rights for all, isonomia

, by expanding the access to power to more citizens. During this period, the word "democracy" (Greek

: δημοκρατία - "rule by the people") was first used by the Athenians to define their new system of government.

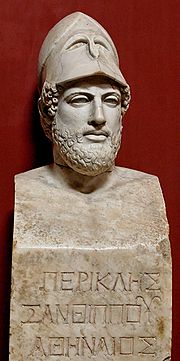

In the next generation, Athens entered in its Golden Age

by becoming a great center of literature

and art. The victories in Persian Wars encouraged the poorest Athenians (who participated in the military exhibitions) to demand a greater say in the running of their city. In the late 460s Ephialtes

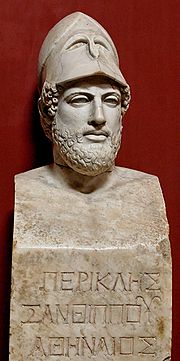

and Pericles

presided over a radicalization of power that shifted the balance decisively to the poorest sections of society, by passing laws, which severely limiting the powers of the Council of the Areopagus and allow thetes (Athenians without wealth) to occupy public office. Pericles was distinguished as its greatest democratic leader, even though he has been accused of running a political machine

. In the following passage, Thucydides

recorded Pericles, in the funeral oration, describing the Athenian system of rule:

The Athenian democracy of Cleisthenes and Pericles, was based on freedom, through the reforms of Solon, and equality (isonomia), introduced by Cleisthenes and later expanded by Ephialtes and Pericles. To preserve these principles the Athenians used lot

The Athenian democracy of Cleisthenes and Pericles, was based on freedom, through the reforms of Solon, and equality (isonomia), introduced by Cleisthenes and later expanded by Ephialtes and Pericles. To preserve these principles the Athenians used lot

for selecting officials. Lot's rationale was to ensure all citizens were "equally" qualified for office, and to avoid any corruption allotment machines were used. Moreover, in most positions chosen by lot, Athenian citizens could not be selected more than once; this rotation in office meant that no-one could build up a power base through staying in a particular position. Another important political institution in Athens was the courts; they were composed with large number of juries

, with no judge

s and they were selected by lot on a daily basis from an annual pool, also chosen by lot. The courts had unlimited power to control the other bodies of the government and its political leaders. Participation by the citizens selected was mandatory, and a modest financial compensation was given to citizens whose livelihood was affected by being "drafted" to office. The only officials chosen by elections, one from each tribe, were the strategoi (generals), where military knowledge was required, and the treasurers, who had to be wealthy, since any funds revealed to have been embezzled were recovered from a treasurer's private fortune. Debate was open to all present and decisions in all matters of policy were taken by majority

vote in Ecclesia (compare direct democracy

), in which all male citizens could participate (in some cases with a quorum of 6000). The decisions taken in Ecclesia were executed by Boule of 500

, which had already approved the agenda for Ecclesia. The Athenian Boule was elected by lot every year and no citizen could serve more than twice. Overall, the Athenian democracy was not only direct in the sense that decisions were made by the assembled people, but also directest in the sense that the people through the assembly, boule and courts of law controlled the entire political process and a large proportion of citizens were involved constantly in the public business. And even though the rights of the individual (probably) were not secured by the Athenian constitution in the modern sense, the Athenians enjoyed their liberties not in opposition to the government, but by living in a city that was not subject to another power and by not being subjects themselves to the rule of another person.

was the first to raise the question, and further expanded by his pupil Plato

, about what is the relation/position of an individual within a community. Aristotle continued the work of his teacher, Plato, and laid the foundations of political philosophy

. The political philosophy created in Athens was in words of Peter Hall, "in a form so complete that hardly added anyone of moment to it for over a millennium". Aristotle systematically analyzed the different systems of rule that the numerous Greek city-states had and categorized them into three categories based on how many ruled; the many (democracy/polity), the few (oligarchy/aristocracy), a single person (tyranny or today autocracy/monarchy). For Aristotle, the underlying principles of democracy are reflected in his work Politics

:

(in 404 BC). Both votes were under manipulation and pressure

, but democracy was recovered in less than a year in both cases. Athens restored again its democratic constitution, after the unification by force of Greece from Phillip II of Macedon and later Alexander the Great, but it was politically shadowed by the Hellenistic empires. Finally after the Roman

conquest of Greece in 146 BC, Athens was restricted to matters of local administration.

However, the decline of democracy was not only due to external powers, but from its citizens, such as Plato and his student Aristotle. Through their influential works, after the rediscovery of classics

during renaissance

, Sparta's political stability was praised, while the Periclean democracy was described as a system of rule, where either the less well-born, the mob (as a collective tyrant) or the poorer classes, were holding power. It was only centuries afterwards, with the publication of "A history of Greece" by George Grote

in 1846, that the Athenian democracy of Pericles started to be viewed positively by political thinkers. Over the last two decades scholars have re-examined the Athenian system of rule as a model of empowering citizens and a "post-modern" example for communities and organisations alike.

Rome was a city-state in Italy

Rome was a city-state in Italy

next to powerful neighbors; Etruscans had built city-states throughout central Italy since 13th century BC and in the south were Greek colonies. Similar to other city-states, Rome was ruled by king. However, social unrest and the pressure of external threats led in 510 BC the last king to be deposed by a group of aristocrats led by Lucius Junius Brutus

. A new constitution was crafted, but the conflict between the ruling families (patricians) and the rest of the population, the plebeians continued. The plebs were demanding for definite, written, and secular laws. The patrician priests, who were the recorders and interpreters of the statutes, by keeping their records secret used their monopoly against social change. After a long resistance to the new demands, the Senate in 454 BC sent a commission of three patricians to Greece to study and report on the legislation of Solon and other lawmakers. When they returned, the Assembly in 451 BC chose ten men - a decemviri - to formulate a new code, and gave them supreme governmental power in Rome for two years. This commission, under the supervision of a resolute reactionary, Appius Claudius, transformed the old customary law of Rome into Twelve Tables

and submitted them to the Assembly (which passed them with some changes) and they were displayed in the Forum

for all who would and could to read. The Twelve Tables recognised certain rights and by the 4th Century BC, the plebs were given the right to stand for consulship and other major offices of the state.

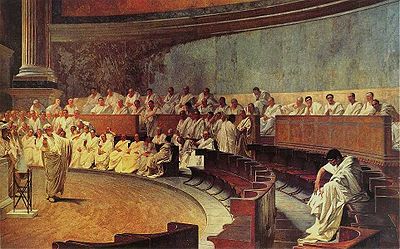

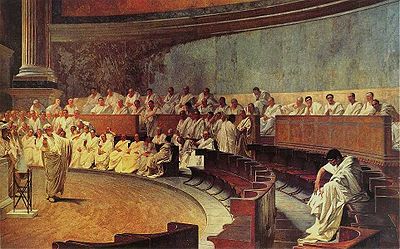

The political structure as outlined in the Roman constitution resembled a mixed constitution and its constituent parts were comparable to those of the Spartan constitution: two consuls, embodying the monarchic form; the Senate

, embodying the aristocratic form; and the people through the assemblies

. The consul was the highest ranking ordinary magistrate. Consuls had power in both civil and military matters. While in the city of Rome, the consuls were the head of the Roman government and they would preside over the Senate and the assemblies. While abroad, each consul would command an army. The Senate passed decrees, which were called senatus consultum and were official advices to a magistrate. However, in practice it was difficult for a magistrate to ignore the Senate's advice. The focus of the Roman Senate was directed towards foreign policy. Though it technically had no official role in the management of military conflict, the Senate ultimately was the force that oversaw such affairs. Also it managed Rome's civil administration. The requirements for becoming a senator included having at least 100,000 denarii

worth of land, being born of the patrician (noble aristocrats) class, and having held public office at least once before. New Senators had to be approved by the sitting members. The people of Rome through the assemblies had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of new laws, the carrying out of capital punishment, the declaration of war and peace, and the creation (or dissolution) of alliances. Despite the obvious power the assemblies had, in practice the assemblies were the least powerful of the other bodies of government. An assembly was legal only if summoned by a magistrate and it was restricted from any legislative initiative or the ability to debate. And even the candidates for public office as Livy

writes "levels were designed so that no one appeared to be excluded from an election and yet all of the clout resided with the leading men". Moreover the unequal weight of votes was making a rare practice for asking the lowest classes for their votes.

Roman stability, in Polybius

’ assessment, was owing to the checks each element put on the superiority of any other: a consul at war, for example, required the cooperation of the Senate and the people if he hoped to secure victory and glory, and could not be indifferent to their wishes. This was not to say that the balance was in every way even: Polybius observes that the superiority of the Roman to the Carthaginian

constitution (another mixed constitution) at the time of the Hannibalic War

was an effect of the latter’s greater inclination toward democracy than to aristocracy. Moreover, recent attempts to posit for Rome personal freedom in the Greek sense – eleutheria: living as you like – have fallen on stony ground, since eleutheria (which was an ideology and way of life in the democratic Athens) was anathema in the Roman eyes. Rome’s core values included order, hierarchy, discipline, and obedience. These values were enforced with laws regulating the private life of an individual. The laws were applied in particular to the upper classes, since the upper classes were the source of Roman moral examples.

Rome became the ruler of a great Mediterranean empire. The new provinces brought wealth to Italy, and fortunes were made through mineral concessions and enormous slave run estates. Slaves were imported to Italy and wealthy landowners soon began to buy up and displace the original peasant farmers. By the late 2nd Century this led to renewed conflict between the rich and poor and demands from the latter for reform of constitution. The background of social unease and the inability of the traditional republican constitutions to adapt to the needs of the growing empire led to the rise of a series of over-mighty generals, championing the cause of either the rich or the poor, in the last century BC.

Over the next few hundred years, various generals would bypass or overthrow the Senate for various reasons, mostly to address perceived injustices, either against themselves or against poorer citizens or soldiers. One of those generals was Julius Caesar

Over the next few hundred years, various generals would bypass or overthrow the Senate for various reasons, mostly to address perceived injustices, either against themselves or against poorer citizens or soldiers. One of those generals was Julius Caesar

, where he marched on Rome and took supreme power over the republic. Caesar's career was cut short by his assassination at Rome in 44 BC by a group of Senators including Marcus Junius Brutus

. In the power vacuum that followed Caesar's assassination, his friend and chief lieutenant, Marcus Antonius, and Caesar's grandnephew Octavian who also was the adopted son of Caesar, rose to prominence. Their combined strength gave the triumvirs absolute power. However, in 31 BC

war between the two broke out. The final confrontation occurred on 2 September 31 BC, at the naval Battle of Actium

where the fleet of Octavian under the command of Agrippa

routed Antony's fleet. Thereafter, there was no one left in the Roman Republic who wanted, or could stand against Octavian, as the adopted son of Caesar moved to take absolute control. Octavian left the majority of Republican institutions intact, though he influenced everything and ultimately, controlled the final decisions, and had the legions to back it up, if necessary. By 27 BC

the transition, though subtle and disguised, was complete. In that year, Octavian offered back all his powers to the Senate, and in a carefully staged way, the Senate refused and titled Octavian Augustus — "the revered one". He was always careful to avoid the title of rex — "king", and instead took on the titles of princeps — "first citizen" and imperator

, a title given by Roman troops to their victorious commanders. The Roman Empire

had been born. Once Octavian named Tiberius

as his heir, it was clear to everyone that even the hope of a restored Republic was dead. Most likely, by the time Augustus died, no one was old enough to know a time before an Emperor ruled Rome. The Roman Republic had been changed into a despotic

régime, which, underneath a competent and strong Emperor, could achieve military supremacy, economic prosperity, and a genuine peace, but under a weak or incompetent one saw its glory tarnished by cruelty, military defeats, revolts, and civil war.

The Roman Empire was eventually divided between the Western Roman Empire

which fell in 476

AD and the Eastern Roman Empire (also called the Byzantine Empire) which lasted until the fall of Constantinople

in 1453 AD.

Most of the procedures used by modern democracies are very old. Almost all cultures have at some time had their new leaders approved, or at least accepted, by the people; and have changed the laws only after consultation with the assembly of the people or their leaders. Such institutions existed since before the Iliad

Most of the procedures used by modern democracies are very old. Almost all cultures have at some time had their new leaders approved, or at least accepted, by the people; and have changed the laws only after consultation with the assembly of the people or their leaders. Such institutions existed since before the Iliad

or the Odyssey

, and modern democracies are often derived or inspired by them, or what remained of them. Nevertheless, the direct result of these institutions was not always a democracy. It was often a narrow oligarchy

, as in Venice

, or even an absolute monarchy

, as in Florence

, in renaissance period but during medieval period they were guild democracies

.

These early institutions include:

has argued that the ideas leading to the American Constitution

and democracy derived from various indigenous peoples of the Americas

including the Iroquois

. Weatherford claimed this democracy was founded between the years 1000-1450, and lasted several hundred years, and that the American democratic system was continually changed and improved by the influence of Native Americans throughout North America. Temple University

professor of anthropology and an authority on the culture and history of the Northern Iroquois Elizabeth Tooker has reviewed these claims and concluded they are myth rather than fact. The idea that North American Indians had a democratic culture is several decades old, but not usually expressed within historical literature. The relationship between the Iroquois League and the Constitution is based on a portion of a letter written by Benjamin Franklin

and a speech by the Iroquois chief Canasatego

in 1744. Tooker concluded that the documents only indicate that some groups of Iroquois and white settlers realized the advantages of a confederation, and that ultimately there is little evidence to support the idea that eighteenth century colonists were knowledgeable regarding the Iroquois system of governance. What little evidence there is regarding this system indicates chiefs of different tribes were permitted representation in the Iroquois League council, and this ability to represent the tribe was hereditary. The council itself did not practice representative government, and there were no elections; deceased chiefs' successors were selected by the most senior woman within the hereditary lineage in consultation with other women in the clan. Decision making occurred through lengthy discussion and decisions were unanimous, with topics discussed being introduced by a single tribe. Tooker concludes that "...there is virtually no evidence that the framers borrowed from the Iroquois" and that the myth that this was the case is the result of exaggerations and misunderstandings of a claim made by Iroquois linguist and ethnographer J.N.B. Hewitt

after his death in 1937.

The Aztecs also practiced elections, but the elected officials elected a supreme speaker, not a ruler.

The two earliest systems used were the Victorian method and the South Australian method. Both were introduced in 1856 to voters in Victoria

and South Australia

. The Victorian method involved voters crossing out all the candidates whom he did not approve of. The South Australian method, which is more similar to what most democracies use today, had voters put a mark in the preferred candidate's corresponding box. The Victorian voting system also was not completely secret, as it was traceable by a special number.

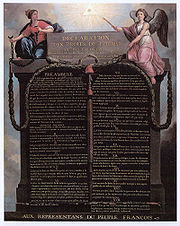

. Already in 1906 full modern democratic rights, universal suffrage

for all citizens was implemented constitutionally in Finland

as well as an proportional representation

, open list

system. Likewise, the February Revolution

in Russia

in 1917 inaugurated a few months of liberal democracy under Alexander Kerensky

until Lenin took over in October. The terrific economic impact of the Great Depression

hurt democratic forces in many countries. The 1930s became a decade of dictators in Europe

and Latin America

.

was ultimately a victory for democracy in Western Europe

, where representative governments were established that reflected the general will of their citizens. However, many countries of Central

and Eastern Europe

became undemocratic Soviet satellite state

s. In Southern Europe

, a number of right-wing authoritarian

dictatorships (most notably in Spain

and Portugal

) continued to exist.

Japan

had moved towards democracy during the Taishō period

during the 1920s, but it was under effective military rule in the years before and during World War II. The country adopted a new constitution during the postwar Allied occupation

, with initial elections in 1946.

in 1956, often cited as the last gasp of European colonialism.

The aftermath of World War II also resulted in the United Nations' decision to partition the British Mandate into two states, one Jewish and one Arab. On May 14, 1948 the state of Israel declared independence and thus was born the first full democracy in the Middle East. Israel is a representative democracy with a parliamentary system and universal suffrage.

India

became a Democratic Republic in 1950 after achieving independence from Great Britain

in 1947. After holding its first national elections in 1952, India

achieved the status of the world's largest liberal

democracy

with universal suffrage

which it continues to hold today. Most of the former British and French colonies were independent by 1965 and at least initially democratic. The process of decolonisation created much political upheaval in Africa and parts of Asia, with some countries experiencing often rapid changes to and from democratic and other forms of government.

In the United States of America, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act

enforced the 15th Amendment, and the 24th Amendment

ended poll tax

ing, removing all tax placed upon voting. Which was a technique which was commonly used to restrict the African American vote. The minimum voting age was reduced to 18 by the 26th Amendment

in 1971.

s in the USSR sphere of influence were also replaced with liberal democracies.

Much of Eastern Europe

, Latin America, East and Southeast Asia, and several Arab, central Asian and African states, and the not-yet-state that is the Palestinian Authority moved towards greater liberal democracy in the 1990s and 2000s.

An analysis by Freedom House

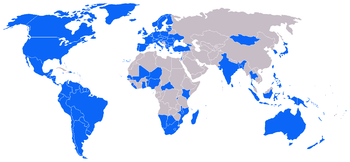

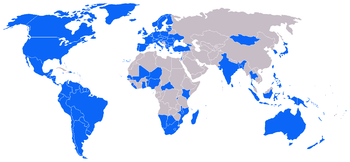

An analysis by Freedom House

shows that there was not a single liberal democracy with universal suffrage

in the world in 1900, but that in 2000, 120 of the world's 192 nations, or 62% were such democracies. They count 25 nations, or 13% of the world's nations with "restricted democratic practices" in 1900 and 16, or 8% of the world's nations today. They counted 19 constitutional monarchies in 1900, forming 14% of the world's nations, where a constitution limited the powers of the monarch, and with some power devolved to elected legislatures, and none in the present. Other nations had, and have, various forms of non-democratic rule. While the specifics may be open to debate (for example, New Zealand

actually enacted universal suffrage

in 1893, but is discounted due to a lack of complete sovereignty and certain restrictions on the Māori vote), the numbers are indicative of the expansion of democracy during the twentieth century.

In the Arab world

, an unprecedented series of major protests occurred with citizens of Egypt

, Tunisia

, Bahrain

, Yemen

, Jordan

, Syria

and other countries across the MENA region demanding democratic rights. This revolutionary wave

was given the term Tunisia Effect. The Palestinian Authority also took action to address democratic rights.

In Iran

, following a highly-disputed presidential vote wrought with fraud, Iranian citizens held a major series of protests calling for change and democratic rights (see: the 2009–2010 Iranian election protests and the 2011 Iranian protests

). The 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq

led to a toppling of Saddam Hussein

and a new constitution with free and open elections and democratic rights.

In Asia, the country of Burma (also known as Myanmar) had long been ruled by a military junta

, however in 2011, the government changed to allow certain voting rights and released democracy-leader Aung San Suu Kyi

from house arrest. However, Burma still will not allow Suu Kyi to run for election and still has major human rights problems and not full democratic rights. In Bhutan

, in December 2005, the 4th King Jigme Singye Wangchuck

announced to that the first general elections would be held in 2008, and that he would abdicate the throne in favor of his eldest son. Bhutan is currently undergoing further changes to allow for a constitutional monarchy

.

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

to its re-emergence and rise from the 17th century to the present day. According to one definition, democracy

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

is a political system

Political system

A political system is a system of politics and government. It is usually compared to the legal system, economic system, cultural system, and other social systems...

in which all the members of the society have an equal share of formal political power

Political power

Political power is a type of power held by a group in a society which allows administration of some or all of public resources, including labour, and wealth. There are many ways to obtain possession of such power. At the nation-state level political legitimacy for political power is held by the...

. In modern representative democracy

Representative democracy

Representative democracy is a form of government founded on the principle of elected individuals representing the people, as opposed to autocracy and direct democracy...

, this formal equality is embodied primarily in the right to vote.

Pre-historic origins

Although it is generally believed that the concepts of democracy and constitution were created in one particular place and time — identified as Ancient Athens circa 508 BC — there is evidence to suggest that democratic forms of government, in a broad sense, may have existed in several areas of the world well before the turn of the 5th century.Within this broad sense it is plausible to assume that democracy in one form or another arises naturally in any well-bonded group, such as a tribe

Tribe

A tribe, viewed historically or developmentally, consists of a social group existing before the development of, or outside of, states.Many anthropologists use the term tribal society to refer to societies organized largely on the basis of kinship, especially corporate descent groups .Some theorists...

. This is tribalism

Tribalism

The social structure of a tribe can vary greatly from case to case, but, due to the small size of tribes, it is always a relatively simple role structure, with few significant social distinctions between individuals....

or primitive democracy. A primitive democracy is identified in small communities or villages when the following take place: face-to-face discussion in the village council or a headman whose decisions are supported by village elders or other cooperative modes of government.

Nevertheless, on larger scale sharper contrasts arise when the village and the city are examined as political communities. In urban governments, all other forms of rule – monarchy

Monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which the office of head of state is usually held until death or abdication and is often hereditary and includes a royal house. In some cases, the monarch is elected...

, tyranny, aristocracy

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

, and oligarchy

Oligarchy

Oligarchy is a form of power structure in which power effectively rests with an elite class distinguished by royalty, wealth, family ties, commercial, and/or military legitimacy...

– have flourished.

Proto-democratic societies

In recent decades scholars have explored the possibility that advancements toward democratic government occurred somewhere else (i.e. other than Greece) first, as GreeceAncient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

developed its complex social and political institutions long after the appearance of the earliest civilizations in Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

and the Near East

Near East

The Near East is a geographical term that covers different countries for geographers, archeologists, and historians, on the one hand, and for political scientists, economists, and journalists, on the other...

.

Mesopotamia

Thorkild Jacobsen

Thorkild Jacobsen was a renowned historian specializing in Assyriology and Sumerian literature.He was one of the foremost scholars on the ancient Near East.-Biography:...

has studied the pre-Babylonian Mesopotamia and uses Sumer

Sumer

Sumer was a civilization and historical region in southern Mesopotamia, modern Iraq during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age....

ian epic, myth and historical records to identify what he calls primitive democracy. By this he means a government in which ultimate power rests with the mass of free male citizens, although "the various functions of government are as yet little specialized, the power structure is loose". In the early period of Sumer, kings such as Gilgamesh

Gilgamesh

Gilgamesh was the fifth king of Uruk, modern day Iraq , placing his reign ca. 2500 BC. According to the Sumerian king list he reigned for 126 years. In the Tummal Inscription, Gilgamesh, and his son Urlugal, rebuilt the sanctuary of the goddess Ninlil, in Tummal, a sacred quarter in her city of...

did not hold the autocratic

Autocracy

An autocracy is a form of government in which one person is the supreme power within the state. It is derived from the Greek : and , and may be translated as "one who rules by himself". It is distinct from oligarchy and democracy...

power which later Mesopotamia rulers wielded. Rather, major city-state

City-state

A city-state is an independent or autonomous entity whose territory consists of a city which is not administered as a part of another local government.-Historical city-states:...

s had a council of elders and a council of "young men" (likely to be comprised by free men bearing arms) that possessed the final political authority, and had to be consulted on all major issues such as war.

This pioneering work, while constantly cited, has invoked little serious discussion and less outright acceptance. The criticism from other scholars focuses on the use of the word "democracy", since the same evidence also can be interpreted convincingly to demonstrate a power struggle between primitive monarchs and the nobility, a struggle in which the common people act more as pawns than the sovereign authority. Jacobsen concedes that the vagueness of the evidence prohibits the separation between the Mesopotamian democracy from a primitive oligarchy.

India

A serious claim for early democratic institutions comes from the independent "republics" of India, sanghaSangha

Sangha is a word in Pali or Sanskrit that can be translated roughly as "association" or "assembly," "company" or "community" with common goal, vision or purpose...

s and gana

Gana

The word ' , in Sanskrit, means "flock, troop, multitude, number, tribe, series, class" . It can also be used to refer to a "body of attendants" and can refer to "a company, any assemblage or association of men formed for the attainment of the same aims".In Hinduism, the s are attendants of Shiva...

s, which existed as early as the sixth century BCE and persisted in some areas until the fourth century CE. The evidence is scattered and no pure historical source exists for that period. In addition, Diodorus (a Greek historian writing two centuries after the time of Alexander the Great's invasion of India), without offering any detail, mentions that independent and democratic states existed in India. However, modern scholars note that the word democracy at the third century BC and later had been degraded and could mean any autonomous state no matter how oligarchic it was.

The main characteristics of the gana seem to be a monarch, usually called raja

Raja

Raja is an Indian term for a monarch, or princely ruler of the Kshatriya varna...

and a deliberative assembly. The assembly met regularly in which at least in some states attendance was open to all free men, and discussed all major state decisions. It had also full financial, administrative, and judicial authority. Other officers, who are rarely mentioned, obeyed the decisions of the assembly. The monarch was elected by the gana and apparently he always belonged to a family of the noble K'satriya

Kshatriya

*For the Bollywood film of the same name see Kshatriya Kshatriya or Kashtriya, meaning warrior, is one of the four varnas in Hinduism...

Varna. The monarch coordinated his activities with the assembly and in some states along with a council of other nobles. The Licchavis

Licchavi (clan)

The Licchavis were the most famous clan amongst the ruling confederate clans of the Vajji mahajanapada of ancient India. Vaishali, the capital of the Licchavis, was the capital of the Vajji mahajanapada also. It was later occupied by Ajatashatru, who annexed the Vajji territory into his...

had a primary governing body of 7,077 rajas, the heads of the most important families. On the other hand, the Shakya

Shakya

Shakya was an ancient janapada of India in the 1st millennium BCE. In Buddhist texts the Shakyas, the inhabitants of Shakya janapada, are mentioned as a clan of Gotama gotra....

s, the Gautama Buddha

Gautama Buddha

Siddhārtha Gautama was a spiritual teacher from the Indian subcontinent, on whose teachings Buddhism was founded. In most Buddhist traditions, he is regarded as the Supreme Buddha Siddhārtha Gautama (Sanskrit: सिद्धार्थ गौतम; Pali: Siddhattha Gotama) was a spiritual teacher from the Indian...

's people, had the assembly open to all men, rich and poor.

Scholars differ over how to describe these governments and the vague, sporadic quality of the evidence allows for wide disagreements. Some emphasize the central role of the assemblies and thus tout them as democracies; other scholars focus on the upper class domination of the leadership and possible control of the assembly and see an oligarchy

Oligarchy

Oligarchy is a form of power structure in which power effectively rests with an elite class distinguished by royalty, wealth, family ties, commercial, and/or military legitimacy...

or an aristocracy

Aristocracy

Aristocracy , is a form of government in which a few elite citizens rule. The term derives from the Greek aristokratia, meaning "rule of the best". In origin in Ancient Greece, it was conceived of as rule by the best qualified citizens, and contrasted with monarchy...

. Despite the obvious power of the assembly, it has not yet been established if the composition and participation was truly popular. The first main obstacle is the lack of evidence describing the popular power of the assembly. This is reflected in the Artha' shastra

Arthashastra

The Arthashastra is an ancient Indian treatise on statecraft, economic policy and military strategy which identifies its author by the names Kautilya and , who are traditionally identified with The Arthashastra (IAST: Arthaśāstra) is an ancient Indian treatise on statecraft, economic policy and...

, an ancient handbook for monarchs on how to rule efficiently. It contains a chapter on dealing with the sangas, which includes injunctions on manipulating the noble leaders, yet it does not mention how to influence the mass of the citizens – a surprising omission if democratic bodies, not the aristocratic families, actively controlled the republican governments. Another issue is the persistence of the four-tiered Varna class system. The duties and privileges on the members of each particular caste – which were rigid enough to prohibit someone sharing a meal with those of another order – might have affected the role members were expected to play in the state, regardless of the formal institutions. The lack of the concept of citizen equality across caste system boundaries lead many scholars to believe that the true nature of ganas and sanghas would not be comparable to that of truly democratic institutions.

Sparta

Oligarchy

Oligarchy is a form of power structure in which power effectively rests with an elite class distinguished by royalty, wealth, family ties, commercial, and/or military legitimacy...

, and the state with which democratic Athens is most often and most fruitfully compared, was Sparta. Yet Sparta, in its rejection of private wealth as a primary social differentiator, was a peculiar kind of oligarchy and some scholars note its resemblance to democracy. In Spartan government, the political power was divided between four bodies: two Spartan Kings

Kings of Sparta

Sparta was an important Greek city-state in the Peloponnesus. It was unusual among Greek city-states in that it maintained its kingship past the Archaic age. It was even more unusual in that it had two kings simultaneously, coming from two separate lines...

(monarchy), gerousia

Gerousia

The Gerousia was the Spartan senate . It was made up of 60 year old Spartan males. It was created by the Spartan lawgiver Lycurgus in the seventh century BC, in his Great Rhetra...

(Counsil of Gerontes (Elders), including the two kings), the ephors (representatives who oversaw the Kings) and the apella

Apella

The Apella was the popular deliberative assembly in the Ancient Greek city-state of Sparta, corresponding to the ecclesia in most other Greek states...

(assembly of Spartans).

The two kings served as the head of the government. They ruled simultaneously but came from two separate lines. The dual kingship diluted the effective power of the executive office. The kings shared their judicial functions with other members of the gerousia. The members of the gerousia had to be over the age of 60 and were elected for life. In theory, any Spartan over that age could stand for election. However, in practice, they were selected from wealthy, aristocratic families. The gerousia possessed the crucial power of legislative initiative. Apella, the most democratic element, was the assembly where Spartans above the age of 30 elected the members of the gerousia and the ephors, and accepted or rejected gerousia's proposals. Finally, the five ephors were Spartans chosen in apella to oversee the actions of the kings and other public officials and, if necessary, depose them. They served for one year and could not be re-elected for a second time. Over the years the ephors held great influence into forming foreign policy and acted as the main executive body of state. Additionally, they had full responsibility of the Spartan educational system, which was essential for maintaining the high standards of the Spartan army. As Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

noted, ephors were the most important key institution of state, but because often they were appointed from the whole social body it resulted in very poor men holding office, with the ensuing possibility that they could easily be bought.

The creator of the Spartan system of rule was the legendary lawgiver Lycurgus

Lycurgus (Sparta)

Lycurgus was the legendary lawgiver of Sparta, who established the military-oriented reformation of Spartan society in accordance with the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi...

. He is associated with the drastic reforms that were instituted in Sparta after the revolt of the helots

Helots

The helots: / Heílôtes) were an unfree population group that formed the main population of Laconia and the whole of Messenia . Their exact status was already disputed in antiquity: according to Critias, they were "especially slaves" whereas to Pollux, they occupied a status "between free men and...

in the second half of the 7th century BC. In order to prevent another helot revolt, Lycurgus devised the highly militarized communal system that made Sparta unique among the city-states of Greece. All his reforms were directed towards the three Spartan virtues: equality (among citizens), military fitness and austerity. It is also probable that Lycurgus delineated the powers of the two traditional organs of the Spartan government, the gerousia

Gerousia

The Gerousia was the Spartan senate . It was made up of 60 year old Spartan males. It was created by the Spartan lawgiver Lycurgus in the seventh century BC, in his Great Rhetra...

and the apella

Apella

The Apella was the popular deliberative assembly in the Ancient Greek city-state of Sparta, corresponding to the ecclesia in most other Greek states...

.

The reforms of Lycurgus were written as a list of rules/laws called Great Rhetra

Great Rhetra

The Great Rhetra was used in two senses by the classical authors. On the one hand it was the Spartan Constitution, believed to have been formulated and established by the legendary lawgiver, Lycurgus. In the legend Lycurgus forbade any written constitution...

; making it the world's first written constitution. In the following centuries Sparta became a military superpower, and its system of rule was admired throughout the Greek world for its political stability. In particular, the concept of equality played an important role in Spartan society. The Spartans referred to themselves as όμοιοι (Homoioi, men of equal status). It was also reflected in the Spartan public educational system, agoge

Agoge

The agōgē was the rigorous education and training regimen mandated for all male Spartan citizens, except for the firstborn son in the ruling houses, Eurypontid and Agiad. The training involved learning stealth, cultivating loyalty to one's group, military training The agōgē (Greek: ἀγωγή in Attic...

, where all citizens irrespective of wealth or status had the same education. This was admired almost universally by contemporaries, from historians such as Herodotus

Herodotus

Herodotus was an ancient Greek historian who was born in Halicarnassus, Caria and lived in the 5th century BC . He has been called the "Father of History", and was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a...

and Xenophon

Xenophon

Xenophon , son of Gryllus, of the deme Erchia of Athens, also known as Xenophon of Athens, was a Greek historian, soldier, mercenary, philosopher and a contemporary and admirer of Socrates...

to philosophers such as Plato

Plato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

and Aristotle. In addition, the Spartan women, unlike elsewhere, enjoyed "every kind of luxury and intemperance" including elementary rights such as the right to inheritance, property ownership and public education. Overall the Spartans were remarkably free to criticize their kings and they were able to depose and exile them. However, despite these democratic elements in the Spartan constitution, there are two cardinal criticisms, classifying Sparta as an oligarchy. First, individual freedom was restricted, since as Plutarch

Plutarch

Plutarch then named, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus , c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia...

writes "no man was allowed to live as he wished", but as in a "military camp" all were engaged in the public service of their polis. And second, the gerousia effectively maintained the biggest share of power of the various governmental bodies.

The political stability of Sparta also meant that no significant changes in the constitution were made. The oligarchic elements of Sparta became even stronger, especially after the influx of gold and silver from the victories in the Persian Wars. In addition, Athens, after the Persian Wars, was becoming the hegemonic power in the Greek world and disagreements between Sparta and Athens over supremacy emerged. These lead to a series of armed conflicts known as the Peloponnesian War

Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War, 431 to 404 BC, was an ancient Greek war fought by Athens and its empire against the Peloponnesian League led by Sparta. Historians have traditionally divided the war into three phases...

, with Sparta prevailing in the end. However, the war exhausted both poleis and Sparta was in turn humbled by Thebes

Thebes, Greece

Thebes is a city in Greece, situated to the north of the Cithaeron range, which divides Boeotia from Attica, and on the southern edge of the Boeotian plain. It played an important role in Greek myth, as the site of the stories of Cadmus, Oedipus, Dionysus and others...

at the Battle of Leuctra

Battle of Leuctra

The Battle of Leuctra was a battle fought on July 6, 371 BC, between the Boeotians led by Thebans and the Spartans along with their allies amidst the post-Corinthian War conflict. The battle took place in the neighbourhood of Leuctra, a village in Boeotia in the territory of Thespiae...

in 371 BC. It was all brought to an end a few years later, when Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon "friend" + ἵππος "horse" — transliterated ; 382 – 336 BC), was a king of Macedon from 359 BC until his assassination in 336 BC. He was the father of Alexander the Great and Philip III.-Biography:...

crushed what remained of the power of the factional city states to his South.

Athens

Athens is regarded as the birthplace of democracy and it is considered an important reference point of democracy.Athens emerged in the 7th century BC, like many other poleis, with a dominating powerful aristocracy. However, this domination led to exploitation causing significant economic, political, and social problems. These problems were enhanced early in the sixth century and as "the many were enslaved to few, the people rose against the notables". At the same period in the Greek world many traditional aristocracies were disrupted by popular revolutions, like Sparta in the second half of the 7th century BC. Sparta's constitutional reforms by Lycurgus introduced a hoplite

Hoplite

A hoplite was a citizen-soldier of the Ancient Greek city-states. Hoplites were primarily armed as spearmen and fought in a phalanx formation. The word "hoplite" derives from "hoplon" , the type of the shield used by the soldiers, although, as a word, "hopla" could also denote weapons held or even...

state and showed how inherited governments can be changed and lead to military victory. After a period of unrest between the rich and the poor, the Athenians of all classes turned to Solon

Solon

Solon was an Athenian statesman, lawmaker, and poet. He is remembered particularly for his efforts to legislate against political, economic and moral decline in archaic Athens...

for acting as a mediator between rival factions, and reaching to a generally satisfactory solution of their problems.

Solon and the foundations of democracy

Solon, an Athenian (Greek) of noble descent but moderate means, was a LyricLyric poetry

Lyric poetry is a genre of poetry that expresses personal and emotional feelings. In the ancient world, lyric poems were those which were sung to the lyre. Lyric poems do not have to rhyme, and today do not need to be set to music or a beat...

poet and later a lawmaker; Plutarch placed him as one of the Seven Sages

Seven Sages of Greece

The Seven Sages or Seven Wise Men was the title given by ancient Greek tradition to seven early 6th century BC philosophers, statesmen and law-givers who were renowned in the following centuries for their wisdom.-The Seven Sages:Traditionally, each of the seven sages represents an aspect of worldly...

of the ancient world. Solon attempted to satisfy all sides by alleviating the suffering of the poor majority without removing all the privileges of the rich minority.

Solon divided the Athenians, into four property classes, with different rights and duties for each. As the Rhetra did in the Lycurgian Sparta, Solon formalized the composition and functions of the governmental bodies. Now, all citizens were entitled to attend the Ecclesia

Ecclesia (ancient Athens)

The ecclesia or ekklesia was the principal assembly of the democracy of ancient Athens during its "Golden Age" . It was the popular assembly, opened to all male citizens over the age of 30 with 2 years of military service by Solon in 594 BC meaning that all classes of citizens in Athens were able...

(Assembly) and vote. Ecclesia became, in principle, the sovereign body, entitled to pass laws and decrees, elect officials, and hear appeals from the most important decisions of the court

Court

A court is a form of tribunal, often a governmental institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordance with the rule of law...

s. All but those in the poorest group might serve, a year at a time, on a new Boule of 400

Boule (Ancient Greece)

In cities of ancient Greece, the boule meaning to will ) was a council of citizens appointed to run daily affairs of the city...

, which was to prepare business for Ecclesia. The higher governmental posts, archons (magistrates), were reserved for citizens of the top two income groups. The retired archons were becoming members of Areopagus

Areopagus

The Areopagus or Areios Pagos is the "Rock of Ares", north-west of the Acropolis, which in classical times functioned as the high Court of Appeal for criminal and civil cases in Athens. Ares was supposed to have been tried here by the gods for the murder of Poseidon's son Alirrothios .The origin...

(Council of the Hill of Ares), and like Gerousia in Sparta, it was able to check improper actions of the newly powerful Ecclesia. Solon created a mixed timocratic

Timocracy

Constitutional theory defines a timocracy as either:# a state where only property owners may participate in government# a government in which love of honor is the ruling principle...

and democratic

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

system of institutions.

Overall, the reforms of the lawgiver Solon in 594 BC, devised to avert the political, economic and moral decline in archaic Athens and gave Athens its first comprehensive code of law. The constitutional reforms eliminated enslavement of Athenians by Athenians, established rules for legal redress against over-reaching aristocratic archons, and assigned political privileges on the basis of productive wealth rather than noble birth. Some of his reforms failed in the short term, yet he is often credited with having laid the foundations for Athenian democracy.

Democracy under Cleisthenes and Pericles

Even though the Solonian reorganization of the constitution improved the economic position of the Athenian lower classes, it did not eliminate the bitter aristocratic contentions for control of the archonship, the chief executive post. PeisistratusPeisistratus

Peisistratos or Peisistratus or Pisistratus may refer to:*Peisistratos of Athens, tyrant at various times between 561 and 528 BC*Pisistratus the younger, r...

became tyrant

Tyrant

A tyrant was originally one who illegally seized and controlled a governmental power in a polis. Tyrants were a group of individuals who took over many Greek poleis during the uprising of the middle classes in the sixth and seventh centuries BC, ousting the aristocratic governments.Plato and...

of Athens three times and remained in power until his death in 527 BC. His sons Hippias

Hippias

Hippias of Elis was a Greek Sophist, and a contemporary of Socrates. With an assurance characteristic of the later sophists, he claimed to be regarded as an authority on all subjects, and lectured on poetry, grammar, history, politics, mathematics, and much else...

and Hipparchus

Hipparchus

Hipparchus, the common Latinization of the Greek Hipparkhos, can mean:* Hipparchus, the ancient Greek astronomer** Hipparchic cycle, an astronomical cycle he created** Hipparchus , a lunar crater named in his honour...

succeeded him.

After the fall of tyranny and before the year 508–507 was over, Cleisthenes

Cleisthenes

Cleisthenes was a noble Athenian of the Alcmaeonid family. He is credited with reforming the constitution of ancient Athens and setting it on a democratic footing in 508/7 BC...

proposed a complete reform of the system of government, which later was approved by the popular Ecclesia

Ecclesia (ancient Athens)

The ecclesia or ekklesia was the principal assembly of the democracy of ancient Athens during its "Golden Age" . It was the popular assembly, opened to all male citizens over the age of 30 with 2 years of military service by Solon in 594 BC meaning that all classes of citizens in Athens were able...

. Cleisthenes reorganized the population into ten tribes, with the aim to change the basis of political organization from the family loyalties to political ones, and improve the army's organization. He also introduced the principle of equality of rights for all, isonomia

Isonomia

Isonomia was a word used by Ancient Greek writers such as Herodotus and Thucydides to refer to some kind of popular government...

, by expanding the access to power to more citizens. During this period, the word "democracy" (Greek

Greek language

Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages. Native to the southern Balkans, it has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning 34 centuries of written records. Its writing system has been the Greek alphabet for the majority of its history;...

: δημοκρατία - "rule by the people") was first used by the Athenians to define their new system of government.

In the next generation, Athens entered in its Golden Age

Age of Pericles

Fifth-century Athens refers to the Greek city-state of Athens in the period of roughly 480 BC-404 BC. This was a period of Athenian political hegemony, economic growth and cultural flourishing formerly known as the Golden Age of Athens or The Age of Pericles. The period began in 480 BC when an...

by becoming a great center of literature

Ancient Greek literature

Ancient Greek literature refers to literature written in the Ancient Greek language until the 4th century.- Classical and Pre-Classical Antiquity :...

and art. The victories in Persian Wars encouraged the poorest Athenians (who participated in the military exhibitions) to demand a greater say in the running of their city. In the late 460s Ephialtes

Ephialtes of Athens

Ephialtes was an ancient Athenian politician and an early leader of the democratic movement there. In the late 460s BC, he oversaw reforms that diminished the power of the Areopagus, a traditional bastion of conservatism, and which are considered by many modern historians to mark the beginning of...

and Pericles

Pericles

Pericles was a prominent and influential statesman, orator, and general of Athens during the city's Golden Age—specifically, the time between the Persian and Peloponnesian wars...

presided over a radicalization of power that shifted the balance decisively to the poorest sections of society, by passing laws, which severely limiting the powers of the Council of the Areopagus and allow thetes (Athenians without wealth) to occupy public office. Pericles was distinguished as its greatest democratic leader, even though he has been accused of running a political machine

Political machine

A political machine is a political organization in which an authoritative boss or small group commands the support of a corps of supporters and businesses , who receive rewards for their efforts...

. In the following passage, Thucydides

Thucydides

Thucydides was a Greek historian and author from Alimos. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC...

recorded Pericles, in the funeral oration, describing the Athenian system of rule:

Sortition

In politics, sortition is the selection of decision makers by lottery. The decision-makers are chosen as a random sample from a larger pool of candidates....

for selecting officials. Lot's rationale was to ensure all citizens were "equally" qualified for office, and to avoid any corruption allotment machines were used. Moreover, in most positions chosen by lot, Athenian citizens could not be selected more than once; this rotation in office meant that no-one could build up a power base through staying in a particular position. Another important political institution in Athens was the courts; they were composed with large number of juries

Jury

A jury is a sworn body of people convened to render an impartial verdict officially submitted to them by a court, or to set a penalty or judgment. Modern juries tend to be found in courts to ascertain the guilt, or lack thereof, in a crime. In Anglophone jurisdictions, the verdict may be guilty,...

, with no judge

Judge

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as part of a panel of judges. The powers, functions, method of appointment, discipline, and training of judges vary widely across different jurisdictions. The judge is supposed to conduct the trial impartially and in an open...

s and they were selected by lot on a daily basis from an annual pool, also chosen by lot. The courts had unlimited power to control the other bodies of the government and its political leaders. Participation by the citizens selected was mandatory, and a modest financial compensation was given to citizens whose livelihood was affected by being "drafted" to office. The only officials chosen by elections, one from each tribe, were the strategoi (generals), where military knowledge was required, and the treasurers, who had to be wealthy, since any funds revealed to have been embezzled were recovered from a treasurer's private fortune. Debate was open to all present and decisions in all matters of policy were taken by majority

Majority

A majority is a subset of a group consisting of more than half of its members. This can be compared to a plurality, which is a subset larger than any other subset; i.e. a plurality is not necessarily a majority as the largest subset may consist of less than half the group's population...

vote in Ecclesia (compare direct democracy

Direct democracy

Direct democracy is a form of government in which people vote on policy initiatives directly, as opposed to a representative democracy in which people vote for representatives who then vote on policy initiatives. Direct democracy is classically termed "pure democracy"...

), in which all male citizens could participate (in some cases with a quorum of 6000). The decisions taken in Ecclesia were executed by Boule of 500

Boule (Ancient Greece)

In cities of ancient Greece, the boule meaning to will ) was a council of citizens appointed to run daily affairs of the city...

, which had already approved the agenda for Ecclesia. The Athenian Boule was elected by lot every year and no citizen could serve more than twice. Overall, the Athenian democracy was not only direct in the sense that decisions were made by the assembled people, but also directest in the sense that the people through the assembly, boule and courts of law controlled the entire political process and a large proportion of citizens were involved constantly in the public business. And even though the rights of the individual (probably) were not secured by the Athenian constitution in the modern sense, the Athenians enjoyed their liberties not in opposition to the government, but by living in a city that was not subject to another power and by not being subjects themselves to the rule of another person.

Birth of political philosophy

Within the Athenian democratic environment many philosophers from all over the Greek world gathered to develop their theories. SocratesSocrates

Socrates was a classical Greek Athenian philosopher. Credited as one of the founders of Western philosophy, he is an enigmatic figure known chiefly through the accounts of later classical writers, especially the writings of his students Plato and Xenophon, and the plays of his contemporary ...

was the first to raise the question, and further expanded by his pupil Plato

Plato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

, about what is the relation/position of an individual within a community. Aristotle continued the work of his teacher, Plato, and laid the foundations of political philosophy

Political philosophy

Political philosophy is the study of such topics as liberty, justice, property, rights, law, and the enforcement of a legal code by authority: what they are, why they are needed, what, if anything, makes a government legitimate, what rights and freedoms it should protect and why, what form it...

. The political philosophy created in Athens was in words of Peter Hall, "in a form so complete that hardly added anyone of moment to it for over a millennium". Aristotle systematically analyzed the different systems of rule that the numerous Greek city-states had and categorized them into three categories based on how many ruled; the many (democracy/polity), the few (oligarchy/aristocracy), a single person (tyranny or today autocracy/monarchy). For Aristotle, the underlying principles of democracy are reflected in his work Politics

Politics (Aristotle)

Aristotle's Politics is a work of political philosophy. The end of the Nicomachean Ethics declared that the inquiry into ethics necessarily follows into politics, and the two works are frequently considered to be parts of a larger treatise, or perhaps connected lectures, dealing with the...

:

The decline, its critics and revival

The Athenian democracy, in its two centuries of life-time, twice voted against its democratic constitution, both during the crisis at the end of the Pelopponesian War, creating first the Four Hundred (in 411 BC) and second Sparta's puppet régime of the Thirty TyrantsThirty Tyrants

The Thirty Tyrants were a pro-Spartan oligarchy installed in Athens after its defeat in the Peloponnesian War in 404 BC. Contemporary Athenians referred to them simply as "the oligarchy" or "the Thirty" ; the expression "Thirty Tyrants" is due to later historians...

(in 404 BC). Both votes were under manipulation and pressure

Demagogy

Demagogy or demagoguery is a strategy for gaining political power by appealing to the prejudices, emotions, fears, vanities and expectations of the public—typically via impassioned rhetoric and propaganda, and often using nationalist, populist or religious themes...