Parliament of England

Encyclopedia

The Parliament of England was the legislature

of the Kingdom of England

. In 1066, William of Normandy introduced a feudal system, by which he sought the advice of a council of tenants-in-chief

and ecclesiastics before making laws. In 1215, the tenants-in-chief secured Magna Carta

from King John

, which established that the king might not levy or collect any taxes (except the feudal taxes to which they were hitherto accustomed), save with the consent of his royal council, which gradually developed into a parliament.

Over the centuries, the English Parliament progressively limited the power of the English monarchy

which arguably culminated in the English Civil War

and the trial and execution of Charles I

in 1649. After the restoration of the monarchy under Charles II

, the supremacy of parliament was a settled principle and all future English and later British sovereigns were restricted to the role of constitutional monarchs with limited executive authority. The Act of Union 1707 merged the English Parliament with the Parliament of Scotland

to form the Parliament of Great Britain

. When the Parliament of Ireland

was abolished in 1801, its former members were merged into what was now called the Parliament of the United Kingdom

.

Hisovernment, the monarch usually must consult and seek a measure of acceptance for his policies if he is to enjoy the broad cooperation of his subjects. Early Kings of England had no standing army

or police

, and so depended on the support of powerful subjects. The monarchy had agents in every part of the country. However, under the feudal system that evolved in England following the Norman Conquest

of 1066, the laws of the Crown could not have been upheld without the support of the nobility

and the clergy

. The former had economic and military power bases of their own through major ownership of land and the feudal obligations of their tenants (some of whom held lands on condition of military service). The Church - then still part of the Roman Catholic Church

and so owing ultimate loyalty to Rome - was virtually a law unto itself in this period as it had its own system of religious law courts.

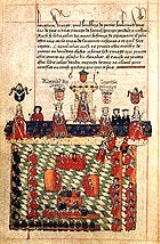

In order to seek consultation and consent from the nobility and the senior clergy on major decisions, post-1066 English monarchs called Great Councils. A typical Great Council would consist of archbishops, bishops, abbots, barons and earls, the pillars of the feudal system.

When this system of consultation and consent broke down it often became impossible for government to function effectively. The two most notorious examples of this prior to the reign of Henry III

are Thomas Becket

and King John.

Becket, who was Archbishop of Canterbury

between 1162 and 1170, was murdered following a long running dispute with Henry II

over the jurisdiction of the Church. John, who was king from 1199 to 1216, aroused such hostility from many leading nobles that they forced him to agree to Magna Carta

in 1215. John's refusal to adhere to this charter led to civil war (see First Barons' War

).

The Great Council evolved into the Parliament of England. The term itself came into use during the early 13th century, deriving from the Latin and French words for discussion and speaking. The word first appears in official documents in the 1230s. As a result of the work by historians G. O. Sayles and H. G. Richardson, it is widely believed that the early parliaments had a judicial as well as a legislative function.

During the 13th and 14th centuries, the Kings began to call Knights of the Shire

to meet when the monarch saw it as necessary. A notable example of this was in 1254 when sheriffs of counties were instructed to send Knights of the Shire to parliament to advise the king on finance

.

Initially, parliaments were mostly summoned when the king needed to raise money through taxes. Following Magna Carta this became a convention. This was due in no small part to the fact that King John died in 1216 and was succeeded by his infant son Henry III. Leading nobles and clergymen governed on Henry's behalf until he came of age, giving them a taste of power that they were not going to relinquish. Among other things, they ensured that Magna Carta was reissued by the young king.

was the last straw. In 1258, seven leading barons forced Henry to agree and swear an oath to the Provisions of Oxford

, which effectively abolished the absolutist Anglo-Norman monarchy, giving power to a council of fifteen barons to deal with the business of government and providing for a thrice-yearly meeting of parliament to monitor their performance. Parliament assembled six times between June 1258 and April 1260, its most notable gathering being the Oxford Parliament

of 1258.

The French-born noble Simon de Montfort

emerged as the leader of this characteristically English rebellion. In the following years, those supporting Montfort and those supporting the king grew more and more polarised. Henry obtained a papal bull

in 1263 exempting him from his oath and both sides began to raise armies. At the Battle of Lewes

on 14 May 1264, Henry was defeated and taken prisoner by Montfort's army. However, many of the nobles who had initially supported Montfort began to suspect that he had gone too far with his reforming zeal. His support amongst the nobility rapidly declined. So in 1264, Montfort summoned the first parliament in English history without any prior royal authorisation. The archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls and barons were summoned, as were two knights from each shire and two burgesses from each borough. Knights had been summoned to previous councils, but the representation of the boroughs was unprecedented. This was purely a move to consolidate Montfort's position as the legitimate governor of the kingdom, since he had captured Henry and his son Prince Edward (later Edward I

) at the Battle of Lewes.

A parliament consisting of representatives of the realm was the logical way for Montfort to establish his authority. In calling this parliament, in a bid to gain popular support, he summoned knights and burgesses from the emerging gentry

class, thus turning to his advantage the fact that most of the nobility had abandoned his movement. This parliament

was summoned on 14 December 1264. It first met on 20 January 1265 in Westminster Hall and was dissolved on 15 February 1265. It is not certain who actually turned up to this parliament. Nonetheless, Montfort's scheme was formally adopted by Edward I

in the so-called "Model Parliament

" of 1295. The attendance at parliament of knights and burgesses historically became known as the summoning of "the Commons", a term derived from the Norman French word "commune", literally translated as the "community of the realm".

Following Edward's escape from captivity, Montfort was defeated and killed at the Battle of Evesham

in 1265. Henry's authority was restored and the Provisions of Oxford were forgotten, but this was nonetheless a turning point in the history of the Parliament of England. Although he was not obliged by statute to do so, Henry summoned the Commons to parliament three times between September 1268 and April 1270. However, this was not a significant turning point in the history of parliamentary democracy. Subsequently, very little is known about how representatives were selected because, at this time, being sent to parliament was not a prestigious undertaking. But Montfort's decision to summon knights and burgesses to his parliament did mark the irreversible emergence of the gentry class as a force in politics. From then on, monarchs could not ignore them, which explains Henry's decision to summon the Commons to several of his post-1265 parliaments.

Even though many nobles who had supported the Provisions of Oxford remained active in English politics throughout Henry's reign, the conditions they had laid down for regular parliaments were largely forgotten, as if to symbolise the historical development of the English Parliament via convention rather than statutes and written constitutions.

As the number of petitions being submitted to parliament increased, they came to be dealt with, and often ignored, more and more by ministers of the Crown so as not to block the passage of government business through parliament. However the emergence of petitioning is significant because it is some of the earliest evidence of parliament being used as a forum to address the general grievances of ordinary people. Submitting a petition to parliament is a tradition that continues to this day in the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

These developments symbolise the fact that parliament and government were by no means the same thing by this point. If monarchs were going to impose their will on their kingdom, they would have to control parliament rather than be subservient to it.

From Edward's reign onwards, the authority of the English Parliament would depend on the strength or weakness of the incumbent monarch. When the king or queen was strong he or she would have enough influence to pass their legislation through parliament without much trouble. Some strong monarchs even bypassed it completely, although this was not often possible in the case of financial legislation due to the post-Magna Carta convention of parliament granting taxes. When weak monarchs governed, parliament often became the centre of opposition against them. Subsequently, the composition of parliaments in this period varied depending on the decisions that needed to be taken in them. The nobility and senior clergy were always summoned. From 1265 onwards, when the monarch needed to raise money through taxes, it was usual for knights and burgesses to be summoned too. However, when the king was merely seeking advice, he often only summoned the nobility and the clergy, sometimes with and sometimes without the knights of the shires. On some occasions the Commons were summoned and sent home again once the monarch was finished with them, allowing parliament to continue without them. It was not until the mid-14th century that summoning representatives of the shires and the boroughs became the norm for all parliaments.

One of the moments that marked the emergence of parliament as a true institution in England was the deposition of Edward II

. Even though it is debatable whether Edward II was deposed in parliament or by parliament, this remarkable sequence of events consolidated the importance of parliament in the English unwritten constitution. Parliament was also crucial in establishing the legitimacy of the king who replaced Edward II: his son Edward III

.

In 1341 the Commons met separately from the nobility and clergy for the first time, creating what was effectively an Upper Chamber and a Lower Chamber, with the knights and burgesses sitting in the latter. This Upper Chamber became known as the House of Lords

from 1544 onward, and the Lower Chamber became known as the House of Commons

, collectively known as the Houses of Parliament.

The authority of parliament grew under Edward III; it was established that no law could be made, nor any tax levied, without the consent of both Houses and the Sovereign. This development occurred during the reign of Edward III because he was involved in the Hundred Years' War

and needed finances. During his conduct of the war, Edward tried to circumvent parliament as much as possible, which caused this edict to be passed.

The Commons came to act with increasing boldness during this period. During the Good Parliament (1376), the Presiding Officer of the lower chamber, Sir Peter de la Mare

, complained of heavy taxes, demanded an accounting of the royal expenditures, and criticised the king's management of the military. The Commons even proceeded to impeach some of the king's ministers. The bold Speaker was imprisoned, but was soon released after the death of Edward III. During the reign of the next monarch, Richard II

, the Commons once again began to impeach errant ministers of the Crown. They insisted that they could not only control taxation, but also public expenditure. Despite such gains in authority, however, the Commons still remained much less powerful than the House of Lords and the Crown.

This period also saw the introduction of a franchise which limited the number of people who could vote in elections for the House of Commons. From 1430 onwards, the franchise was limited to Forty Shilling Freeholders

, that is men who owned freehold property worth forty shillings or more. The Parliament of England legislated the new uniform county franchise, in the statute 8 Hen. 6, c. 7. The Chronological Table of the Statutes does not mention such a 1430 law, as it was included in the Consolidated Statutes as a recital in the Electors of Knights of the Shire Act 1432 (10 Hen. 6, c. 2), which amended and re-enacted the 1430 law to make clear that the resident of a county had to have a forty shilling freehold in that county to be a voter there.

that the modern structure of the English Parliament began to be created. The Tudor monarchy was powerful and there were often periods of several years time when parliament did not sit at all. However the Tudor monarchs were astute enough to realise that they needed parliament to legitimise many of their decisions, mostly out of a need to raise money through taxation legitimately without causing discontent. Thus they consolidated the state of affairs whereby monarchs would call and close parliament as and when they needed it.

By the time Henry Tudor (Henry VII

) came to the throne in 1485 the monarch was not a member of either the Upper Chamber or the Lower Chamber. Consequently, the monarch would have to make his or her feelings known to Parliament through his or her supporters in both houses. Proceedings were regulated by the presiding officer in either chamber. From the 1540s the presiding officer in the House of Commons became formally known as the "Speaker

", having previously been referred to as the "prolocutor" or "parlour" (a semi-official position, often nominated by the monarch, that had existed ever since Peter de Montfort

had acted as the presiding officer of the Oxford Parliament of 1258). This was not an enviable job. When the House of Commons was unhappy it was the Speaker who had to deliver this news to the monarch. This began the tradition, that survives to this day, whereby the Speaker of the House of Commons is dragged to the Speaker's Chair by other members once elected.

A member of either chamber could present a "bill" to parliament. Bills supported by the monarch were often proposed by members of their Privy Council

who sat in parliament. In order for a bill to become law it would have to be approved by a majority of both Houses of Parliament before it passed to the monarch for royal assent

or veto

. The royal veto was applied several times during the 16th and 17th centuries and it is still the right of the monarch of the United Kingdom to veto legislation today, although it has not been exercised since 1707 (today such exercise would presumably precipitate a constitutional crisis

).

When a bill became law this process theoretically gave the bill the approval of each estate of the realm: the King, Lords, and Commons. In reality this was not accurate. The Parliament of England was far from being a democratically representative institution in this period. It was possible to assemble the entire nobility and senior clergy of the realm in one place to form the estate of the Upper Chamber. However, the voting franchise for the House of Commons was small; some historians estimate that it was as little as 3% of the adult male population. This meant that elections could sometimes be controlled by local grandees because in some boroughs the voters were in some way dependent on local nobles or alternatively they could be bought off with bribes or kickbacks. If these grandees were supporters of the incumbent monarch, this gave the Crown and its ministers considerable influence over the business of parliament. Many of the men elected to parliament did not relish the prospect of having to act in the interests of others. So a rule was enacted, still on the statute book today, whereby it became illegal for members of the House of Commons to resign their seat unless they were granted a position directly within the patronage of the monarchy (today this latter restriction leads to a legal fiction

allowing de facto resignation despite the prohibition). However, it must be emphasised that while several elections to parliament in this period were in some way corrupt by modern standards, many elections involved genuine contests between rival candidates, although the ballot was not secret.

It was in this period that the Palace of Westminster

was established as the seat of the English Parliament. In 1548, the House of Commons was granted a regular meeting place by the Crown, St Stephen's Chapel

. This had been a royal chapel. It was made into a debating chamber after Henry VIII

became the last monarch to use the Palace of Westminster as a place of residence and following the suppression of the college there. This room became the home of the House of Commons until it was destroyed by fire in 1834, although the interior was altered several times up until then. The structure of this room was pivotal in the development of the Parliament of England. While most modern legislatures sit in a circular chamber, the benches of the British Houses of Parliament are laid out in the form of choir stalls in a chapel, simply because this is the part of the original room that the members of the House of Commons utilised when they were granted use of St Stephen's Chapel. This structure took on a new significance with the emergence of political parties in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, as the tradition began whereby the members of the governing party would sit on the benches to the right of the Speaker and the opposition members on the benches to the left. It is said that the Speaker's chair was placed in front of the chapel's altar. As Members came and went they observed the custom of bowing to the altar and continued to do so, even when it had been taken away, thus then bowing to the Chair, as is still the custom today.

The numbers of the Lords Spiritual

diminished under Henry VIII, who commanded the Dissolution of the Monasteries

, thereby depriving the abbots and priors of their seats in the Upper House. For the first time, the Lords Temporal were more numerous than the Lords Spiritual. Currently, the Lords Spiritual consist of the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, the Bishops of London, Durham and Winchester, and twenty-one other English diocesan bishops in seniority of appointment to a diocese.

The Laws in Wales Acts of 1535–42 annexed Wales

as part of England and this brought Welsh representatives into the Parliament of England.

In 1628, alarmed by the arbitrary exercise of royal power, the House of Commons submitted to Charles I

the Petition of Right

, demanding the restoration of their liberties. Though he accepted the petition, Charles later dissolved parliament and ruled without them for eleven years. It was only after the financial disaster of the Scottish Bishops' Wars

(1639–1640) that he was forced to recall Parliament so that they could authorise new taxes. This resulted in the calling of the assemblies known historically as the Short Parliament

of 1640 and the Long Parliament

, which sat with several breaks and in various forms between 1640 and 1660.

The Long Parliament was characterised by the growing number of critics of the king who sat in it. The most prominent of these critics in the House of Commons was John Pym

. Tensions between the king and his parliament reached boiling point in January 1642 when Charles entered the House of Commons and tried, unsuccessfully, to arrest Pym and four other members for their alleged treason. The five members had been tipped off about this, and by the time Charles came into the chamber with a group of soldiers they had disappeared. Charles was further humiliated when he asked the Speaker, William Lenthall

, to give their whereabouts, which Lenthall famously refused to do.

From then on relations between the king and his parliament deteriorated further. When trouble started to brew in Ireland, both Charles and his parliament raised armies to quell the uprisings by native Catholics there. It was not long before it was clear that these forces would end up fighting each other, leading to the English Civil War

which began with the Battle of Edgehill

in October 1642: those supporting the cause of parliament were called Parliamentarians (or Roundhead

s).

The final victory of the parliamentary forces was a turning point in the history of the Parliament of England. This marked the point when parliament replaced the monarchy as the supreme source of power in England. Battles between Crown and Parliament would continue throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, but parliament was no longer subservient to the English monarchy. This change was symbolised in the execution of Charles I in January 1649. It is somewhat ironic that this event was not instigated by the elected representatives of the realm. In Pride's Purge

of December 1648, the New Model Army

(which by then had emerged as the leading force in the parliamentary alliance) purged Parliament of members that did not support them. The remaining "Rump Parliament

", as it was later referred to by critics, enacted legislation to put the king on trial for treason. This trial, the outcome of which was a foregone conclusion, led to the execution of the king and the start of an 11 year republic. The House of Lords was abolished and the purged House of Commons governed England until April 1653, when army chief Oliver Cromwell

dissolved it following disagreements over religious policy and how to carry out elections to parliament. Cromwell later convened a parliament of religious radicals in 1653, commonly known as the Barebone's Parliament, followed by the unicameral First Protectorate Parliament

that sat from September 1654 to January 1655 and the Second Protectorate Parliament

that sat in two sessions between 1656 and 1658, the first session was unicameral and the second session was bicameral.

Although it is easy to dismiss the English Republic of 1649-60 as nothing more than a Cromwellian military dictatorship, the events that took place in this decade were hugely important in determining the future of parliament. First, it was during the sitting of the first Rump Parliament that members of the House of Commons became known as "MPs" (Members of Parliament). Second, Cromwell gave a huge degree of freedom to his parliaments, although royalists were barred from sitting in all but a handful of cases. His vision of parliament appears to have been largely based on the example of the Elizabethan parliaments. However, he underestimated the extent to which Elizabeth I and her ministers had directly and indirectly influenced the decision-making process of her parliaments. He was thus always surprised when they became troublesome. He ended up dissolving each parliament that he convened. Yet it is worth noting that the structure of the second session of the Second Protectorate Parliament of 1658 was almost identical to the parliamentary structure consolidated in the Glorious Revolution

Settlement of 1689.

In 1653 Cromwell had been made head of state with the title Lord Protector of the Realm. The Second Protectorate Parliament offered him the crown. Cromwell rejected this offer, but the governmental structure embodied in the final version of the Humble Petition and Advice

was a basis for all future parliaments. It proposed an elected House of Commons as the Lower Chamber, a House of Lords containing peers of the realm as the Upper Chamber, and a constitutional monarchy, subservient to parliament and the laws of the nation, as the executive arm of the state at the top of the tree, assisted in carrying out their duties by a Privy Council. Oliver Cromwell had thus inadvertently presided over the creation of a basis for the future parliamentary government of England.

In terms of the evolution of parliament as an institution, by far the most important development during the republic was the sitting of the Rump Parliament between 1649 and 1653. This proved that parliament could survive without a monarchy and a House of Lords if it wanted to. Future English monarchs would never forget this. Charles I was the last English monarch ever to enter the House of Commons. Even to this day, a Member of the Parliament of the United Kingdom is sent to Buckingham Palace

as a ceremonial hostage during the State Opening of Parliament

, in order to ensure the safe return of the sovereign from a potentially hostile parliament. During the ceremony the monarch sits on the throne in the House of Lords and signals for the Lord Great Chamberlain

to summon the House of Commons to the Lords Chamber. The Lord Great Chamberlain then raises his wand of office to signal to the Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod, who has been waiting in the central lobby. Black Rod turns and, escorted by the doorkeeper of the House of Lords and an inspector of police, approaches the doors to the chamber of the Commons. The doors are slammed in his face – symbolising the right of the Commons to debate without the presence of the Queen's representative. He then strikes three times with his staff (the Black Rod), and he is admitted.

of the monarchy in 1660. Following the death of Oliver Cromwell in September 1658, his son Richard Cromwell

succeeded him as Lord Protector, summoning the Third Protectorate Parliament

in the process. When this parliament was dissolved following pressure from the army in April 1659, the Rump Parliament was recalled at the insistence of the surviving army grandees. This in turn was dissolved in a coup led by army general John Lambert

, leading to the formation of the Committee of Safety

, dominated by Lambert and his supporters. When the breakaway forces of George Monck invaded England from Scotland where they had been stationed — without Lambert's supporters putting up a fight — Monck temporarily recalled the Rump Parliament and reversed Pride's Purge by recalling the entirety of the Long Parliament. They then voted to dissolve themselves and call new elections, which were arguably the most democratic for 20 years although the franchise was still very small. This led to the calling of the Convention Parliament which was dominated by royalists. This parliament voted to reinstate the monarchy and the House of Lords. Charles II

returned to England as king in May 1660.

The Restoration began the tradition whereby all governments looked to parliament for legitimacy. In 1681 Charles II dissolved parliament and ruled without them for the last four years of his reign. This followed bitter disagreements between the king and parliament that had occurred between 1679 and 1681. Charles took a big gamble by doing this. He risked the possibility of a military showdown akin to that of 1642. However he rightly predicted that the nation did not want another civil war. Parliament disbanded without a fight. Events that followed ensured that this would be nothing but a temporary blip.

Charles II died in 1685 and he was succeeded by his brother James II

. During his lifetime Charles had always pledged loyalty to the Protestant Church of England, despite his private Catholic sympathies. James was openly Catholic. He attempted to lift restrictions on Catholics taking up public offices. This was bitterly opposed by Protestants in his kingdom. When civil war became an imminent prospect James fled the country. Parliament then offered the Crown to his Protestant daughter Mary

, instead of his son (James Francis Edward Stuart

). Mary II then ruled jointly with her husband, William III

. Parliament took this opportunity to approve the 1689 Bill of Rights

and later the 1701 Act of Settlement

. These were statutes that lawfully upheld the prominence of parliament for the first time in English history. These events marked the beginning of the English constitutional monarchy and its subservience to parliament.

created a new Kingdom of Great Britain

and dissolved both parliaments, replacing them with a new Parliament of Great Britain

based in the former home of the English parliament. The Parliament of Great Britain later became the Parliament of the United Kingdom

in 1801 when the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

was formed through the Act of Union 1800

.

, which came to the fore after devolutionary changes

to British parliaments. Before 1998, all political issues, even when only concerning parts of the United Kingdom, were decided by the British parliament at Westminster. After separate regional parliaments or assemblies were introduced in Scotland

, Wales

and Northern Ireland

in 1998, issues concerning only these parts of the United Kingdom were often decided by the respective devolved assemblies, while purely English issues were

decided by the entire British parliament, with MPs from Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland fully participating in debating and voting. The establishment of a devolved English parliament

, giving separate decision-making powers to representatives for voters in England, has thus become an issue in British politics.

The question of a devolved English parliament was considered a minor issue until the Conservative Party

announced policy proposals to ban Scottish MPs from voting on English issues, thus raising the profile of the problem. The political parties which are campaigning for an English Parliament are the British National Party

, the English Democrats, the Free England Party

and UKIP. The SNP and Plaid Cymru also call for an English parliament, although they feel the best way to achieve this is through a dissolution of Union, they will accept federation in the interim. Since 1997, the Campaign for an English Parliament

(CEP) has been campaigning for a referendum

on an English Parliament. Despite institutional opposition in Westminster to a Parliament for England, the CEP has had some success in bringing the issue to peoples' attention, particularly in political and academic circles.

Members of Parliament are elected simultaneously in general elections all over the United Kingdom. There are 529 English constituencies, which because of their large number, they form an inbuilt majority in the House of Commons

. However, there have been notable occasions - Foundation Hospitals, Top-up fees

and the new runway at Heathrow, for example - where MPs elected in England have been outvoted by MPs from the rest of the UK on English-only legislation that is devolved outside of England. As the British Government considered Scotland to be over-represented in relation to the other components of the United Kingdom, Clause 81 of the Scotland Act 1998

equalised the English

and Scottish electoral quota, and London alone now provides more MPs per capita than Scotland does.

Recent surveys of public opinion on the establishment of an English parliament have given widely varying conclusions. In the first five years of devolution for Scotland and Wales, support in England for the establishment of an English parliament was low at between 16 and 19 per cent, according to successive British Social Attitudes Survey

s. A report, also based on the British Social Attitudes Survey, published in December 2010 suggests that only 29 per cent of people in England support the establishment of an English parliament, though this figure had risen from 17 per cent in 2007.

One 2007 poll carried out for BBC Newsnight

, however, found that 61 per cent would support such a parliament being established. Krishan Kumar notes that support for measures to ensure that only English MPs can vote on legislation that applies only to England is generally higher than that for the establishment of an English parliament, although support for both varies depending on the timing of the opinion poll and the wording of the question. Kumar argues that "despite devolution and occasional bursts of English nationalism – more an expression of exasperation with the Scots or Northern Irish – the English remain on the whole satisfied with current constitutional arrangements".

Places where Parliament has been held other than London

Reading Abbey, 1453

Coventry

, 1459 (Parliament of Devils

)

See also

Sources

External links

Legislature

A legislature is a kind of deliberative assembly with the power to pass, amend, and repeal laws. The law created by a legislature is called legislation or statutory law. In addition to enacting laws, legislatures usually have exclusive authority to raise or lower taxes and adopt the budget and...

of the Kingdom of England

Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was, from 927 to 1707, a sovereign state to the northwest of continental Europe. At its height, the Kingdom of England spanned the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and several smaller outlying islands; what today comprises the legal jurisdiction of England...

. In 1066, William of Normandy introduced a feudal system, by which he sought the advice of a council of tenants-in-chief

Tenant-in-chief

In medieval and early modern European society the term tenant-in-chief, sometimes vassal-in-chief, denoted the nobles who held their lands as tenants directly from king or territorial prince to whom they did homage, as opposed to holding them from another nobleman or senior member of the clergy....

and ecclesiastics before making laws. In 1215, the tenants-in-chief secured Magna Carta

Magna Carta

Magna Carta is an English charter, originally issued in the year 1215 and reissued later in the 13th century in modified versions, which included the most direct challenges to the monarch's authority to date. The charter first passed into law in 1225...

from King John

John of England

John , also known as John Lackland , was King of England from 6 April 1199 until his death...

, which established that the king might not levy or collect any taxes (except the feudal taxes to which they were hitherto accustomed), save with the consent of his royal council, which gradually developed into a parliament.

Over the centuries, the English Parliament progressively limited the power of the English monarchy

Monarchy

A monarchy is a form of government in which the office of head of state is usually held until death or abdication and is often hereditary and includes a royal house. In some cases, the monarch is elected...

which arguably culminated in the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

and the trial and execution of Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

in 1649. After the restoration of the monarchy under Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

, the supremacy of parliament was a settled principle and all future English and later British sovereigns were restricted to the role of constitutional monarchs with limited executive authority. The Act of Union 1707 merged the English Parliament with the Parliament of Scotland

Parliament of Scotland

The Parliament of Scotland, officially the Estates of Parliament, was the legislature of the Kingdom of Scotland. The unicameral parliament of Scotland is first found on record during the early 13th century, with the first meeting for which a primary source survives at...

to form the Parliament of Great Britain

Parliament of Great Britain

The Parliament of Great Britain was formed in 1707 following the ratification of the Acts of Union by both the Parliament of England and Parliament of Scotland...

. When the Parliament of Ireland

Parliament of Ireland

The Parliament of Ireland was a legislature that existed in Dublin from 1297 until 1800. In its early mediaeval period during the Lordship of Ireland it consisted of either two or three chambers: the House of Commons, elected by a very restricted suffrage, the House of Lords in which the lords...

was abolished in 1801, its former members were merged into what was now called the Parliament of the United Kingdom

Parliament of the United Kingdom

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body in the United Kingdom, British Crown dependencies and British overseas territories, located in London...

.

Hisovernment, the monarch usually must consult and seek a measure of acceptance for his policies if he is to enjoy the broad cooperation of his subjects. Early Kings of England had no standing army

Standing army

A standing army is a professional permanent army. It is composed of full-time career soldiers and is not disbanded during times of peace. It differs from army reserves, who are activated only during wars or natural disasters...

or police

Police

The police is a personification of the state designated to put in practice the enforced law, protect property and reduce civil disorder in civilian matters. Their powers include the legitimized use of force...

, and so depended on the support of powerful subjects. The monarchy had agents in every part of the country. However, under the feudal system that evolved in England following the Norman Conquest

Norman conquest of England

The Norman conquest of England began on 28 September 1066 with the invasion of England by William, Duke of Normandy. William became known as William the Conqueror after his victory at the Battle of Hastings on 14 October 1066, defeating King Harold II of England...

of 1066, the laws of the Crown could not have been upheld without the support of the nobility

Nobility

Nobility is a social class which possesses more acknowledged privileges or eminence than members of most other classes in a society, membership therein typically being hereditary. The privileges associated with nobility may constitute substantial advantages over or relative to non-nobles, or may be...

and the clergy

Clergy

Clergy is the generic term used to describe the formal religious leadership within a given religion. A clergyman, churchman or cleric is a member of the clergy, especially one who is a priest, preacher, pastor, or other religious professional....

. The former had economic and military power bases of their own through major ownership of land and the feudal obligations of their tenants (some of whom held lands on condition of military service). The Church - then still part of the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

and so owing ultimate loyalty to Rome - was virtually a law unto itself in this period as it had its own system of religious law courts.

In order to seek consultation and consent from the nobility and the senior clergy on major decisions, post-1066 English monarchs called Great Councils. A typical Great Council would consist of archbishops, bishops, abbots, barons and earls, the pillars of the feudal system.

When this system of consultation and consent broke down it often became impossible for government to function effectively. The two most notorious examples of this prior to the reign of Henry III

Henry III of England

Henry III was the son and successor of John as King of England, reigning for 56 years from 1216 until his death. His contemporaries knew him as Henry of Winchester. He was the first child king in England since the reign of Æthelred the Unready...

are Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket

Thomas Becket was Archbishop of Canterbury from 1162 until his murder in 1170. He is venerated as a saint and martyr by both the Roman Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion...

and King John.

Becket, who was Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

between 1162 and 1170, was murdered following a long running dispute with Henry II

Henry II of England

Henry II ruled as King of England , Count of Anjou, Count of Maine, Duke of Normandy, Duke of Aquitaine, Duke of Gascony, Count of Nantes, Lord of Ireland and, at various times, controlled parts of Wales, Scotland and western France. Henry, the great-grandson of William the Conqueror, was the...

over the jurisdiction of the Church. John, who was king from 1199 to 1216, aroused such hostility from many leading nobles that they forced him to agree to Magna Carta

Magna Carta

Magna Carta is an English charter, originally issued in the year 1215 and reissued later in the 13th century in modified versions, which included the most direct challenges to the monarch's authority to date. The charter first passed into law in 1225...

in 1215. John's refusal to adhere to this charter led to civil war (see First Barons' War

First Barons' War

The First Barons' War was a civil war in the Kingdom of England, between a group of rebellious barons—led by Robert Fitzwalter and supported by a French army under the future Louis VIII of France—and King John of England...

).

The Great Council evolved into the Parliament of England. The term itself came into use during the early 13th century, deriving from the Latin and French words for discussion and speaking. The word first appears in official documents in the 1230s. As a result of the work by historians G. O. Sayles and H. G. Richardson, it is widely believed that the early parliaments had a judicial as well as a legislative function.

During the 13th and 14th centuries, the Kings began to call Knights of the Shire

Knights of the Shire

From the creation of the Parliament of England in mediaeval times until 1826 each county of England and Wales sent two Knights of the Shire as members of Parliament to represent the interests of the county, when the number of knights from Yorkshire was increased to four...

to meet when the monarch saw it as necessary. A notable example of this was in 1254 when sheriffs of counties were instructed to send Knights of the Shire to parliament to advise the king on finance

Taxation in medieval England

Taxation in medieval England was the system of raising money for royal and governmental expenses. During the Anglo-Saxon period, the main forms of taxation were land taxes, although custom duties and fees to mint coins were also imposed. The most important tax of the late Anglo-Saxon period was the...

.

Initially, parliaments were mostly summoned when the king needed to raise money through taxes. Following Magna Carta this became a convention. This was due in no small part to the fact that King John died in 1216 and was succeeded by his infant son Henry III. Leading nobles and clergymen governed on Henry's behalf until he came of age, giving them a taste of power that they were not going to relinquish. Among other things, they ensured that Magna Carta was reissued by the young king.

Parliament in the reign of Henry III

Once the infancy of Henry III ended and he took full control of the government of his kingdom, many leading nobles became increasingly concerned at his style of government, specifically his unwillingness to consult them on the decisions he took and his perceived willingness to bestow patronage upon his foreign relatives in preference to his native subjects. Henry's decision to support a disastrous papal invasion of SicilySicily

Sicily is a region of Italy, and is the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Along with the surrounding minor islands, it constitutes an autonomous region of Italy, the Regione Autonoma Siciliana Sicily has a rich and unique culture, especially with regard to the arts, music, literature,...

was the last straw. In 1258, seven leading barons forced Henry to agree and swear an oath to the Provisions of Oxford

Provisions of Oxford

The Provisions of Oxford are often regarded as England's first written constitution ....

, which effectively abolished the absolutist Anglo-Norman monarchy, giving power to a council of fifteen barons to deal with the business of government and providing for a thrice-yearly meeting of parliament to monitor their performance. Parliament assembled six times between June 1258 and April 1260, its most notable gathering being the Oxford Parliament

Oxford Parliament (1258)

The Oxford Parliament , also known as the "Mad Parliament" and the "First English Parliament", assembled during the reign of Henry III of England. It was established by Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester. The parlour or prolocutor was Peter de Montfort under the direction of Simon de Montfort...

of 1258.

The French-born noble Simon de Montfort

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester

Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester, 1st Earl of Chester , sometimes referred to as Simon V de Montfort to distinguish him from other Simon de Montforts, was an Anglo-Norman nobleman. He led the barons' rebellion against King Henry III of England during the Second Barons' War of 1263-4, and...

emerged as the leader of this characteristically English rebellion. In the following years, those supporting Montfort and those supporting the king grew more and more polarised. Henry obtained a papal bull

Papal bull

A Papal bull is a particular type of letters patent or charter issued by a Pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the bulla that was appended to the end in order to authenticate it....

in 1263 exempting him from his oath and both sides began to raise armies. At the Battle of Lewes

Battle of Lewes

The Battle of Lewes was one of two main battles of the conflict known as the Second Barons' War. It took place at Lewes in Sussex, on 14 May 1264...

on 14 May 1264, Henry was defeated and taken prisoner by Montfort's army. However, many of the nobles who had initially supported Montfort began to suspect that he had gone too far with his reforming zeal. His support amongst the nobility rapidly declined. So in 1264, Montfort summoned the first parliament in English history without any prior royal authorisation. The archbishops, bishops, abbots, earls and barons were summoned, as were two knights from each shire and two burgesses from each borough. Knights had been summoned to previous councils, but the representation of the boroughs was unprecedented. This was purely a move to consolidate Montfort's position as the legitimate governor of the kingdom, since he had captured Henry and his son Prince Edward (later Edward I

Edward I of England

Edward I , also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England from 1272 to 1307. The first son of Henry III, Edward was involved early in the political intrigues of his father's reign, which included an outright rebellion by the English barons...

) at the Battle of Lewes.

A parliament consisting of representatives of the realm was the logical way for Montfort to establish his authority. In calling this parliament, in a bid to gain popular support, he summoned knights and burgesses from the emerging gentry

Gentry

Gentry denotes "well-born and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past....

class, thus turning to his advantage the fact that most of the nobility had abandoned his movement. This parliament

Parliament

A parliament is a legislature, especially in those countries whose system of government is based on the Westminster system modeled after that of the United Kingdom. The name is derived from the French , the action of parler : a parlement is a discussion. The term came to mean a meeting at which...

was summoned on 14 December 1264. It first met on 20 January 1265 in Westminster Hall and was dissolved on 15 February 1265. It is not certain who actually turned up to this parliament. Nonetheless, Montfort's scheme was formally adopted by Edward I

Edward I of England

Edward I , also known as Edward Longshanks and the Hammer of the Scots, was King of England from 1272 to 1307. The first son of Henry III, Edward was involved early in the political intrigues of his father's reign, which included an outright rebellion by the English barons...

in the so-called "Model Parliament

Model Parliament

The Model Parliament is the term, attributed to Frederic William Maitland, used for the 1295 Parliament of England of King Edward I. This assembly included members of the clergy and the aristocracy, as well as representatives from the various counties and boroughs. Each county returned two knights,...

" of 1295. The attendance at parliament of knights and burgesses historically became known as the summoning of "the Commons", a term derived from the Norman French word "commune", literally translated as the "community of the realm".

Following Edward's escape from captivity, Montfort was defeated and killed at the Battle of Evesham

Battle of Evesham

The Battle of Evesham was one of the two main battles of 13th century England's Second Barons' War. It marked the defeat of Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, and the rebellious barons by Prince Edward – later King Edward I – who led the forces of his father, King Henry III...

in 1265. Henry's authority was restored and the Provisions of Oxford were forgotten, but this was nonetheless a turning point in the history of the Parliament of England. Although he was not obliged by statute to do so, Henry summoned the Commons to parliament three times between September 1268 and April 1270. However, this was not a significant turning point in the history of parliamentary democracy. Subsequently, very little is known about how representatives were selected because, at this time, being sent to parliament was not a prestigious undertaking. But Montfort's decision to summon knights and burgesses to his parliament did mark the irreversible emergence of the gentry class as a force in politics. From then on, monarchs could not ignore them, which explains Henry's decision to summon the Commons to several of his post-1265 parliaments.

Even though many nobles who had supported the Provisions of Oxford remained active in English politics throughout Henry's reign, the conditions they had laid down for regular parliaments were largely forgotten, as if to symbolise the historical development of the English Parliament via convention rather than statutes and written constitutions.

The emergence of parliament as an institution

During the reign of Edward I, which began in 1272, the role of Parliament in the government of the English kingdom increased due to Edward's determination to unite England, Wales and Scotland under his rule by force. He was also keen to unite his subjects in order to restore his authority and not face rebellion as was his father's fate. Edward therefore encouraged all sectors of society to submit petitions to parliament detailing their grievances in order for them to be sorted out. This seemingly gave all of Edward's subjects a potential role in government and this helped Edward assert his authority.As the number of petitions being submitted to parliament increased, they came to be dealt with, and often ignored, more and more by ministers of the Crown so as not to block the passage of government business through parliament. However the emergence of petitioning is significant because it is some of the earliest evidence of parliament being used as a forum to address the general grievances of ordinary people. Submitting a petition to parliament is a tradition that continues to this day in the Parliament of the United Kingdom.

These developments symbolise the fact that parliament and government were by no means the same thing by this point. If monarchs were going to impose their will on their kingdom, they would have to control parliament rather than be subservient to it.

From Edward's reign onwards, the authority of the English Parliament would depend on the strength or weakness of the incumbent monarch. When the king or queen was strong he or she would have enough influence to pass their legislation through parliament without much trouble. Some strong monarchs even bypassed it completely, although this was not often possible in the case of financial legislation due to the post-Magna Carta convention of parliament granting taxes. When weak monarchs governed, parliament often became the centre of opposition against them. Subsequently, the composition of parliaments in this period varied depending on the decisions that needed to be taken in them. The nobility and senior clergy were always summoned. From 1265 onwards, when the monarch needed to raise money through taxes, it was usual for knights and burgesses to be summoned too. However, when the king was merely seeking advice, he often only summoned the nobility and the clergy, sometimes with and sometimes without the knights of the shires. On some occasions the Commons were summoned and sent home again once the monarch was finished with them, allowing parliament to continue without them. It was not until the mid-14th century that summoning representatives of the shires and the boroughs became the norm for all parliaments.

One of the moments that marked the emergence of parliament as a true institution in England was the deposition of Edward II

Edward II of England

Edward II , called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England from 1307 until he was deposed by his wife Isabella in January 1327. He was the sixth Plantagenet king, in a line that began with the reign of Henry II...

. Even though it is debatable whether Edward II was deposed in parliament or by parliament, this remarkable sequence of events consolidated the importance of parliament in the English unwritten constitution. Parliament was also crucial in establishing the legitimacy of the king who replaced Edward II: his son Edward III

Edward III of England

Edward III was King of England from 1327 until his death and is noted for his military success. Restoring royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father, Edward II, Edward III went on to transform the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe...

.

In 1341 the Commons met separately from the nobility and clergy for the first time, creating what was effectively an Upper Chamber and a Lower Chamber, with the knights and burgesses sitting in the latter. This Upper Chamber became known as the House of Lords

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

from 1544 onward, and the Lower Chamber became known as the House of Commons

House of Commons of England

The House of Commons of England was the lower house of the Parliament of England from its development in the 14th century to the union of England and Scotland in 1707, when it was replaced by the House of Commons of Great Britain...

, collectively known as the Houses of Parliament.

The authority of parliament grew under Edward III; it was established that no law could be made, nor any tax levied, without the consent of both Houses and the Sovereign. This development occurred during the reign of Edward III because he was involved in the Hundred Years' War

Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War was a series of separate wars waged from 1337 to 1453 by the House of Valois and the House of Plantagenet, also known as the House of Anjou, for the French throne, which had become vacant upon the extinction of the senior Capetian line of French kings...

and needed finances. During his conduct of the war, Edward tried to circumvent parliament as much as possible, which caused this edict to be passed.

The Commons came to act with increasing boldness during this period. During the Good Parliament (1376), the Presiding Officer of the lower chamber, Sir Peter de la Mare

Peter de la Mare

Sir Peter de la Mare was an English politician and Presiding Officer of the House of Commons during the Good Parliament of 1376....

, complained of heavy taxes, demanded an accounting of the royal expenditures, and criticised the king's management of the military. The Commons even proceeded to impeach some of the king's ministers. The bold Speaker was imprisoned, but was soon released after the death of Edward III. During the reign of the next monarch, Richard II

Richard II of England

Richard II was King of England, a member of the House of Plantagenet and the last of its main-line kings. He ruled from 1377 until he was deposed in 1399. Richard was a son of Edward, the Black Prince, and was born during the reign of his grandfather, Edward III...

, the Commons once again began to impeach errant ministers of the Crown. They insisted that they could not only control taxation, but also public expenditure. Despite such gains in authority, however, the Commons still remained much less powerful than the House of Lords and the Crown.

This period also saw the introduction of a franchise which limited the number of people who could vote in elections for the House of Commons. From 1430 onwards, the franchise was limited to Forty Shilling Freeholders

Forty Shilling Freeholders

Forty shilling freeholders were a group of landowners who had the Parliamentary franchise to vote in county constituencies in various parts of the British Isles. In England it was the only such qualification from 1430 until 1832...

, that is men who owned freehold property worth forty shillings or more. The Parliament of England legislated the new uniform county franchise, in the statute 8 Hen. 6, c. 7. The Chronological Table of the Statutes does not mention such a 1430 law, as it was included in the Consolidated Statutes as a recital in the Electors of Knights of the Shire Act 1432 (10 Hen. 6, c. 2), which amended and re-enacted the 1430 law to make clear that the resident of a county had to have a forty shilling freehold in that county to be a voter there.

King, Lords, and Commons

It was during the reign of the Tudor monarchsTudor dynasty

The Tudor dynasty or House of Tudor was a European royal house of Welsh origin that ruled the Kingdom of England and its realms, including the Lordship of Ireland, later the Kingdom of Ireland, from 1485 until 1603. Its first monarch was Henry Tudor, a descendant through his mother of a legitimised...

that the modern structure of the English Parliament began to be created. The Tudor monarchy was powerful and there were often periods of several years time when parliament did not sit at all. However the Tudor monarchs were astute enough to realise that they needed parliament to legitimise many of their decisions, mostly out of a need to raise money through taxation legitimately without causing discontent. Thus they consolidated the state of affairs whereby monarchs would call and close parliament as and when they needed it.

By the time Henry Tudor (Henry VII

Henry VII of England

Henry VII was King of England and Lord of Ireland from his seizing the crown on 22 August 1485 until his death on 21 April 1509, as the first monarch of the House of Tudor....

) came to the throne in 1485 the monarch was not a member of either the Upper Chamber or the Lower Chamber. Consequently, the monarch would have to make his or her feelings known to Parliament through his or her supporters in both houses. Proceedings were regulated by the presiding officer in either chamber. From the 1540s the presiding officer in the House of Commons became formally known as the "Speaker

Speaker of the British House of Commons

The Speaker of the House of Commons is the presiding officer of the House of Commons, the United Kingdom's lower chamber of Parliament. The current Speaker is John Bercow, who was elected on 22 June 2009, following the resignation of Michael Martin...

", having previously been referred to as the "prolocutor" or "parlour" (a semi-official position, often nominated by the monarch, that had existed ever since Peter de Montfort

Peter de Montfort

Sir Peter de Montfort was an English parliamentarian.In 1257 he was High Sheriff of Staffordshire and Shropshire....

had acted as the presiding officer of the Oxford Parliament of 1258). This was not an enviable job. When the House of Commons was unhappy it was the Speaker who had to deliver this news to the monarch. This began the tradition, that survives to this day, whereby the Speaker of the House of Commons is dragged to the Speaker's Chair by other members once elected.

A member of either chamber could present a "bill" to parliament. Bills supported by the monarch were often proposed by members of their Privy Council

Privy council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a nation, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the monarch's closest advisors to give confidential advice on...

who sat in parliament. In order for a bill to become law it would have to be approved by a majority of both Houses of Parliament before it passed to the monarch for royal assent

Royal Assent

The granting of royal assent refers to the method by which any constitutional monarch formally approves and promulgates an act of his or her nation's parliament, thus making it a law...

or veto

Veto

A veto, Latin for "I forbid", is the power of an officer of the state to unilaterally stop an official action, especially enactment of a piece of legislation...

. The royal veto was applied several times during the 16th and 17th centuries and it is still the right of the monarch of the United Kingdom to veto legislation today, although it has not been exercised since 1707 (today such exercise would presumably precipitate a constitutional crisis

Constitutional crisis

A constitutional crisis is a situation that the legal system's constitution or other basic principles of operation appear unable to resolve; it often results in a breakdown in the orderly operation of government...

).

When a bill became law this process theoretically gave the bill the approval of each estate of the realm: the King, Lords, and Commons. In reality this was not accurate. The Parliament of England was far from being a democratically representative institution in this period. It was possible to assemble the entire nobility and senior clergy of the realm in one place to form the estate of the Upper Chamber. However, the voting franchise for the House of Commons was small; some historians estimate that it was as little as 3% of the adult male population. This meant that elections could sometimes be controlled by local grandees because in some boroughs the voters were in some way dependent on local nobles or alternatively they could be bought off with bribes or kickbacks. If these grandees were supporters of the incumbent monarch, this gave the Crown and its ministers considerable influence over the business of parliament. Many of the men elected to parliament did not relish the prospect of having to act in the interests of others. So a rule was enacted, still on the statute book today, whereby it became illegal for members of the House of Commons to resign their seat unless they were granted a position directly within the patronage of the monarchy (today this latter restriction leads to a legal fiction

Resignation from the British House of Commons

Members of Parliament sitting in the House of Commons in the United Kingdom are technically forbidden to resign. To circumvent this prohibition, a legal fiction is used...

allowing de facto resignation despite the prohibition). However, it must be emphasised that while several elections to parliament in this period were in some way corrupt by modern standards, many elections involved genuine contests between rival candidates, although the ballot was not secret.

It was in this period that the Palace of Westminster

Palace of Westminster

The Palace of Westminster, also known as the Houses of Parliament or Westminster Palace, is the meeting place of the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom—the House of Lords and the House of Commons...

was established as the seat of the English Parliament. In 1548, the House of Commons was granted a regular meeting place by the Crown, St Stephen's Chapel

St Stephen's Chapel

St Stephen's Chapel was a chapel in the old Palace of Westminster. It was largely lost in the fire of 1834, but the Chapel of St Mary Undercroft in the crypt survived...

. This had been a royal chapel. It was made into a debating chamber after Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

became the last monarch to use the Palace of Westminster as a place of residence and following the suppression of the college there. This room became the home of the House of Commons until it was destroyed by fire in 1834, although the interior was altered several times up until then. The structure of this room was pivotal in the development of the Parliament of England. While most modern legislatures sit in a circular chamber, the benches of the British Houses of Parliament are laid out in the form of choir stalls in a chapel, simply because this is the part of the original room that the members of the House of Commons utilised when they were granted use of St Stephen's Chapel. This structure took on a new significance with the emergence of political parties in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, as the tradition began whereby the members of the governing party would sit on the benches to the right of the Speaker and the opposition members on the benches to the left. It is said that the Speaker's chair was placed in front of the chapel's altar. As Members came and went they observed the custom of bowing to the altar and continued to do so, even when it had been taken away, thus then bowing to the Chair, as is still the custom today.

The numbers of the Lords Spiritual

Lords Spiritual

The Lords Spiritual of the United Kingdom, also called Spiritual Peers, are the 26 bishops of the established Church of England who serve in the House of Lords along with the Lords Temporal. The Church of Scotland, which is Presbyterian, is not represented by spiritual peers...

diminished under Henry VIII, who commanded the Dissolution of the Monasteries

Dissolution of the Monasteries

The Dissolution of the Monasteries, sometimes referred to as the Suppression of the Monasteries, was the set of administrative and legal processes between 1536 and 1541 by which Henry VIII disbanded monasteries, priories, convents and friaries in England, Wales and Ireland; appropriated their...

, thereby depriving the abbots and priors of their seats in the Upper House. For the first time, the Lords Temporal were more numerous than the Lords Spiritual. Currently, the Lords Spiritual consist of the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, the Bishops of London, Durham and Winchester, and twenty-one other English diocesan bishops in seniority of appointment to a diocese.

The Laws in Wales Acts of 1535–42 annexed Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

as part of England and this brought Welsh representatives into the Parliament of England.

Rebellion and Revolution

Parliament had not always submitted to the wishes of the Tudor monarchs. But parliamentary criticism of the monarchy reached new levels in the 17th century. When the last Tudor monarch, Elizabeth I, died in 1603, King James VI of Scotland came to power as King James I, founding the Stuart monarchy.In 1628, alarmed by the arbitrary exercise of royal power, the House of Commons submitted to Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

the Petition of Right

Petition of right

In English law, a petition of right was a remedy available to subjects to recover property from the Crown.Before the Crown Proceedings Act 1947, the British Crown could not be sued in contract...

, demanding the restoration of their liberties. Though he accepted the petition, Charles later dissolved parliament and ruled without them for eleven years. It was only after the financial disaster of the Scottish Bishops' Wars

Bishops' Wars

The Bishops' Wars , were conflicts, both political and military, which occurred in 1639 and 1640 centred around the nature of the governance of the Church of Scotland, and the rights and powers of the Crown...

(1639–1640) that he was forced to recall Parliament so that they could authorise new taxes. This resulted in the calling of the assemblies known historically as the Short Parliament

Short Parliament

The Short Parliament was a Parliament of England that sat from 13 April to 5 May 1640 during the reign of King Charles I of England, so called because it lasted only three weeks....

of 1640 and the Long Parliament

Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was made on 3 November 1640, following the Bishops' Wars. It received its name from the fact that through an Act of Parliament, it could only be dissolved with the agreement of the members, and those members did not agree to its dissolution until after the English Civil War and...

, which sat with several breaks and in various forms between 1640 and 1660.

The Long Parliament was characterised by the growing number of critics of the king who sat in it. The most prominent of these critics in the House of Commons was John Pym

John Pym

John Pym was an English parliamentarian, leader of the Long Parliament and a prominent critic of James I and then Charles I.- Early life and education :...

. Tensions between the king and his parliament reached boiling point in January 1642 when Charles entered the House of Commons and tried, unsuccessfully, to arrest Pym and four other members for their alleged treason. The five members had been tipped off about this, and by the time Charles came into the chamber with a group of soldiers they had disappeared. Charles was further humiliated when he asked the Speaker, William Lenthall

William Lenthall

William Lenthall was an English politician of the Civil War period. He served as Speaker of the House of Commons.-Early life:...

, to give their whereabouts, which Lenthall famously refused to do.

From then on relations between the king and his parliament deteriorated further. When trouble started to brew in Ireland, both Charles and his parliament raised armies to quell the uprisings by native Catholics there. It was not long before it was clear that these forces would end up fighting each other, leading to the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

which began with the Battle of Edgehill

Battle of Edgehill

The Battle of Edgehill was the first pitched battle of the First English Civil War. It was fought near Edge Hill and Kineton in southern Warwickshire on Sunday, 23 October 1642....

in October 1642: those supporting the cause of parliament were called Parliamentarians (or Roundhead

Roundhead

"Roundhead" was the nickname given to the supporters of the Parliament during the English Civil War. Also known as Parliamentarians, they fought against King Charles I and his supporters, the Cavaliers , who claimed absolute power and the divine right of kings...

s).

The final victory of the parliamentary forces was a turning point in the history of the Parliament of England. This marked the point when parliament replaced the monarchy as the supreme source of power in England. Battles between Crown and Parliament would continue throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, but parliament was no longer subservient to the English monarchy. This change was symbolised in the execution of Charles I in January 1649. It is somewhat ironic that this event was not instigated by the elected representatives of the realm. In Pride's Purge

Pride's Purge

Pride’s Purge is an event in December 1648, during the Second English Civil War, when troops under the command of Colonel Thomas Pride forcibly removed from the Long Parliament all those who were not supporters of the Grandees in the New Model Army and the Independents...

of December 1648, the New Model Army

New Model Army

The New Model Army of England was formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians in the English Civil War, and was disbanded in 1660 after the Restoration...

(which by then had emerged as the leading force in the parliamentary alliance) purged Parliament of members that did not support them. The remaining "Rump Parliament

Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament is the name of the English Parliament after Colonel Pride purged the Long Parliament on 6 December 1648 of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason....

", as it was later referred to by critics, enacted legislation to put the king on trial for treason. This trial, the outcome of which was a foregone conclusion, led to the execution of the king and the start of an 11 year republic. The House of Lords was abolished and the purged House of Commons governed England until April 1653, when army chief Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

dissolved it following disagreements over religious policy and how to carry out elections to parliament. Cromwell later convened a parliament of religious radicals in 1653, commonly known as the Barebone's Parliament, followed by the unicameral First Protectorate Parliament

First Protectorate Parliament

The First Protectorate Parliament was summoned by the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell under the terms of the Instrument of Government. It sat for one term from 3 September 1654 until 22 January 1655 with William Lenthall as the Speaker of the House....

that sat from September 1654 to January 1655 and the Second Protectorate Parliament

Second Protectorate Parliament

The Second Protectorate Parliament in England sat for two sessions from 17 September 1656 until 4 February 1658, with Thomas Widdrington as the Speaker of the House of Commons...

that sat in two sessions between 1656 and 1658, the first session was unicameral and the second session was bicameral.

Although it is easy to dismiss the English Republic of 1649-60 as nothing more than a Cromwellian military dictatorship, the events that took place in this decade were hugely important in determining the future of parliament. First, it was during the sitting of the first Rump Parliament that members of the House of Commons became known as "MPs" (Members of Parliament). Second, Cromwell gave a huge degree of freedom to his parliaments, although royalists were barred from sitting in all but a handful of cases. His vision of parliament appears to have been largely based on the example of the Elizabethan parliaments. However, he underestimated the extent to which Elizabeth I and her ministers had directly and indirectly influenced the decision-making process of her parliaments. He was thus always surprised when they became troublesome. He ended up dissolving each parliament that he convened. Yet it is worth noting that the structure of the second session of the Second Protectorate Parliament of 1658 was almost identical to the parliamentary structure consolidated in the Glorious Revolution

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also called the Revolution of 1688, is the overthrow of King James II of England by a union of English Parliamentarians with the Dutch stadtholder William III of Orange-Nassau...

Settlement of 1689.

In 1653 Cromwell had been made head of state with the title Lord Protector of the Realm. The Second Protectorate Parliament offered him the crown. Cromwell rejected this offer, but the governmental structure embodied in the final version of the Humble Petition and Advice

Humble Petition and Advice