Edward Hallett Carr

Encyclopedia

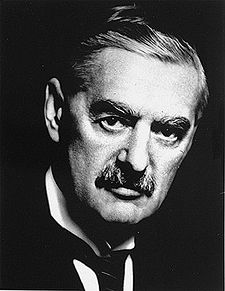

Edward Hallett "Ted" Carr CBE

(28 June 1892 – 3 November 1982) was a liberal and later Marxist British historian

, journalist and international relations

theorist, and an opponent of empiricism

within historiography

.

Carr was best known for his 14-volume history of the Soviet Union, in which he provided an account of Soviet history from 1917 to 1929, for his writings on international relations, and for his book What Is History?

, in which he laid out historiographical principles rejecting traditional historical methods and practices.

Educated at the Merchant Taylors' School

, London, and at Trinity College, Cambridge

, Carr began his career as a diplomat in 1916. Becoming increasingly preoccupied with the study of international relations and of the Soviet Union, he resigned from the Foreign Office in 1936 to begin an academic career. From 1941 to 1946, Carr worked as an assistant editor at The Times, where he was noted for his leaders (editorials) urging a socialist system and an Anglo-Soviet alliance as the basis of a post-war order. Afterwards, Carr worked on a massive 14-volume work on Soviet history entitled A History of Soviet Russia

, a project that he was still engaged on at the time of his death in 1982. In 1961, he delivered the G. M. Trevelyan lectures at the University of Cambridge

that became the basis of his book, What is History? Moving increasingly towards the left throughout his career, Carr saw his role as the theorist who would work out the basis of a new international order.

in London, and Trinity College, Cambridge

, where he was awarded a First Class Degree in Classics

in 1916. Carr's family had orginated in northern England, and the first mention of his ancestors was a George Carr who served as the Sheriff of Newcastle in 1450. Carr's parents were Francis Parker and Jesse (née Hallet) Carr. They were initially Conservatives

, but went over to supporting the Liberals

in 1903 over the free trade

issue. When Joseph Chamberlain

proclaimed his opposition to free trade and announced in favour of Imperial preference

, Carr's father, for whom all tariff

s were abhorrent, changed his political loyalties. Carr described the atmosphere at the Merchant Taylors School as:"...95% of my school fellows came from orthodox Conservative homes, and regarded Lloyd George as an incarnation of the devil. We Liberals were a tiny despised minority." From his parents, Carr inherited a strong belief in progress as an unstoppable force in world affairs, and throughout his life a recurring theme in Carr's thinking was that the world was getting progressively a better place. With his belief in progress was a tendency on Carr's part to decry pessimism as mere whining from those who could not appreciate the benefits of progress. In 1911, Carr won the Craven Scholarship to attend Trinity College at Cambridge. As an undergraduate at Cambridge, Carr was much impressed by hearing one of his professors lecture on how the Peloponnesian War

influenced Herodotus

in the writing of the Histories

. Carr found this to be a great discovery—the subjectivity of the historian's craft. This discovery was later to influence his 1961 book What is History?.

in 1916, resigning in 1936. Carr was excused from military service for medical reasons. Carr was at first assigned to the Contraband Department of the Foreign Office, which sought to enforce the blockade on Germany, and then in 1917 was assigned to the Northern Department, which amongst other areas dealt with relations with Russia. In 1918, Carr was involved in the negotiations to have the British diplomats imprisoned in Petrograd by the Bolsheviks released in exchange for the British releasing the Soviet diplomats imprisoned in London in retaliation. As a diplomat, Carr was later praised by the Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax

as someone who had "distinguished himself not only by sound learning and political understanding, but also in administrative ability". At first, Carr knew nothing about the Bolsheviks. Carr later recalled:

s were destined to win the Russian Civil War

, and approved of the Prime Minister David Lloyd George

's opposition to the anti-Bolshevik ideas of the War Secretary Winston Churchill

on the grounds of realpolitik

. In Carr's opinion, Churchill's support of the White Russian

movement was folly as Russia was destined to be a great power once more under the leadership of the Bolsheviks, and it was foolish for Britain to support the losing side of the Russian Civil War. Carr was to later to write that in the spring of 1919 he "was disappointed when he [Lloyd George] gave way (in part) on the Russian question in order to buy French consent to concessions to Germany on Upper Silesia, Danzig and reparations"

In 1919, Carr was part of the British delegation at the Paris Peace Conference

In 1919, Carr was part of the British delegation at the Paris Peace Conference

and was involved in the drafting of parts of the Treaty of Versailles

relating to the League of Nations

. During the peace conference, Carr was much offended at the Allied, especially French, treatment of the Germans, writing that the German delegation at the peace conference were "cheated over the "Fourteen Points", and subjected to every petty humiliation" Beside working on the sections of the Versailles treaty relating to the League of Nations, Carr was also involved in working out the borders between Germany and the newly reborn state of Poland. Initially, Carr favoured Poland, urging in a memo in February 1919 that Britain recognize Poland at once, and that the German city of Danzig (modern Gdańsk

, Poland) be ceded to Poland In March 1919, Carr fought against the idea of a Minorities Treaty

for Poland, arguing that the rights of ethnic and religious minorities in Poland would be best guaranteed by not involving the international community in Polish internal affairs By the spring of 1919, Carr's relations with the Polish delegation had declined to a state of mutual hostility. Carr's tendency to favour the claims of the Germans at the expense of the Poles led the British historian Adam Zamoyski

to note that Carr "…held views of the most extraordinary racial arrogance on all of the nations of Eastern Europe". Carr's biographer, Jonathan Haslam wrote in a 2000 essay that Carr grew up in a Germanophile household, in which German culture was deeply appreciated, which in turn always coloured Carr's views towards Germany throughout his life. As a result of his Germanophile

and anti-Polish views, Carr supported the territorial claims of the Reich against Poland. In a letter written in 1954 to his friend, Isaac Deutscher

, Carr described his attitude to Poland at the time:

After the peace conference, Carr was stationed at the British Embassy in Paris until 1921, and in 1920 was awarded a CBE

. At first, Carr had great faith in the League, which he believed would prevent both another world war and ensure a better post-war world. Carr later recalled:

before being sent to the British Embassy in Riga

, Latvia

, where he served as Second Secretary between 1925–29. In 1925, Carr married Anne Ward Howe, by whom he had one son. During his time in Riga (which at that time possessed a substantial Russian émigré community), Carr became increasing fascinated with Russian literature and culture and wrote several works on various aspects of Russian life. Carr's interests in Russia and Russians were further increased by his boredom with life in Riga. Carr described Riga as "...an intellectual desert". Carr learnt Russian

during his time in Riga in order to read Russian writers in the original. In 1927, Carr paid his first visit to Moscow. Carr was later to write that reading Alexander Herzen

, Fyodor Dostoevsky

and the work of other 19th century Russian intellectuals caused him to re-think his liberal

views. Carr wrote under the impact of reading various Russian writers he found:

, The Spectator

, the Times Literary Supplement and later towards the end of his life, the London Review of Books

. In particular, Carr emerged as the Times Literary Supplements Soviet expert in the early 1930s, a position he still held at the time of his death in 1982 Because of his status as a diplomat (until 1936), most of Carr's reviews in the period 1929–36 were published either anonymously or under the pseudonym "John Hallett". Between 1931 and 1937, Carr published many works on many historians and history, works that gave much fledgling discipline of international relations much vigour and discipline. In the summer of 1929, Carr began work on a biography of the Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky

, during which the course of researching Dostoevsky's life, Carr befriended Prince D. S. Mirsky

, a Russian émigré scholar living at that time in Britain.

Beside studies on international relations

, Carr's writings in the 1930s included biographies of Fyodor Dostoevsky

(1931), Karl Marx

(1934), and Mikhail Bakunin

(1937). An early sign of Carr's increasing admiration of the Soviet Union was a 1929 review of Baron Pyotr Wrangel

's memoirs where Carr wrote:

. Carr wrote:

In the early 1930s, Carr found the Great Depression

to be almost profoundly shocking as the First World War. In an article entitled "England Adrift" published in September 1930, Carr wrote:

Further increasing Carr's interest in a replacement ideology for liberalism was his reaction to hearing the debates in January 1931 at the General Assembly of the League of Nations in Geneva

, Switzerland, and especially the speeches on the merits of free trade between the Yugoslav Foreign Minister Vojislav Marinkovich and the British Foreign Secretary Arthur Henderson

. Carr wrote:

It was at this time that Carr started to admire the Soviet Union. Carr wrote in a book review in February 1931:

's extremely favourable assessment of the Soviet economy. Carr concluded that "as regards economic development, Professor Dobb is conclusive".

Beside writing on Soviet affairs, Carr also commented on other international events. In an essay published in February 1933 in the Fortnightly Review, Carr blamed what he regarded as a putative Versailles treaty for the recent accession to power of Adolf Hitler

Carr wrote that in the 1920s, German leaders like Gustav Stresemann

were unable to secure sufficient modifications of the Versailles treaty owning to the intractable attitude of the Western powers, especially France, and now the West had reaped what it had sowed in the form of the Nazi regime. However, despite some concerns about National Socialism, Carr ended his essay by writing that:

Initially, Carr's political outlook was anti-Marxist and liberal. In his 1934 biography of Karl Marx

, Carr presented his subject as highly intelligent man and a gifted writer, but one whose talents were devoted entirely for destruction. Carr argued that Marx's sole and only motivation was a mindless class hatred. Carr labelled dialectical materialism

gibberish, and the labour theory of value doctrinal and derivative. Carr wrote that:

In view of his later conversion to a sort of quasi-Marxism, Carr was to find the passages in Karl Marx: A Study in Fanaticism criticizing Marx to be highly embarrassing, and refused to allow the book to be republished. Carr was to later call his Marx biography his worst book, and complained that he had written it only because his publisher had made a Marx biography the precondition of publishing the biography of Mikhail Bakunin

that he was writing. In his books such as The Romantic Exiles and Dostoevsky, Carr was noted for his highly ironical treatment of his subjects, implying that their lives were of interest but not of great importance. In the mid-1930s, Carr was especially preoccupied with the life and ideas of Bakunin. During this period, Carr started writing a novel about the visit of a Bakunin-type Russian radical to Victorian Britain who proceeded to expose all of Carr regarded as the pretensions and hypocrisies of British bourgeois society. The novel was never finished or published.

As a diplomat in the 1930s, Carr took the view that great division of the world into rival trading blocs caused by the American Smoot Hawley Act

As a diplomat in the 1930s, Carr took the view that great division of the world into rival trading blocs caused by the American Smoot Hawley Act

of 1930 was the principal cause of German belligerence in foreign policy, as Germany was now unable to export finished goods or import raw materials cheaply. In Carr's opinion, if Germany could be given its own economic zone to dominate in Eastern Europe comparable to the British Imperial preference economic zone, the U.S. dollar zone in the Americas, the French gold bloc zone and the Japanese economic zone, then the peace of the would could be assured. In a memo written on January 30, 1936, Carr wrote:

, and played a role in Carr's resignation from the Foreign Office later in 1936 In an article entitled "An English Nationalist Abroad" published in May 1936 in the Spectator, Carr wrote "The methods of the Tudor sovereigns, when they were making the English nation, invite many comparisons with those of the Nazi regime in Germany" In this way, Carr argued that it was hypocritical for people in Britain to criticize the Nazi regime's human rights record Because of Carr's strong antagonism to the Treaty of Versailles

, which he viewed as unjust to Germany, Carr was very supportive of the Nazi regime's efforts to destroy Versailles through moves such as the Remilitarisation of the Rhineland in 1936 Carr later wrote of his views in the 1930s that "No doubt, I was very blind".

, and is particularly known for his contribution on international relations theory

. Carr's last words of advice as a diplomat was a memo urging that Britain accept the Balkans

as an exclusive zone of influence for Germany. Additionally in articles published in the Christian Science Monitor on December 2, 1936 and in the January 1937 edition of Fortnightly Review

, Carr argued that the Soviet Union and France were not working for collective security

, but rather "...a division of the Great Powers into two armored camps", supported non-intervention in the Spanish Civil War

, and asserted that King Leopold III

of Belgium had made a major step towards peace with his declaration of neutrality of October 14, 1936. Two major intellectual influences on Carr in the mid-1930s were Karl Mannheim

's 1936 book Ideology and Utopia, and the work of Reinhold Niebuhr

on the need to combine morality with realism.

Carr's appointment as the Woodrow Wilson Professor of International Politics caused a stir when he started to use his position to criticize the League of Nations, a viewpoint which caused much tension with his benefactor, Lord Davies

, who was a strong supporter of the League. Lord Davies had established the Wilson Chair in 1924 with the intention of increasing public support for his beloved League, which helps to explain his chagrin at Carr's anti-League lectures. In his first lecture on October 14, 1936 Carr stated the League was ineffective and that:

In 1937, Carr visited the Soviet Union for a second time, and was impressed by what he saw. During his visit to the Soviet Union, Carr may have inadvertently caused the death of his friend, Prince D. S. Mirsky

. Carr stumbled into Prince Mirsky on the streets of Leningrad

(modern Saint Petersburg

, Russia), and despite Prince Mirsky's best efforts to pretend not to know him, Carr persuaded his old friend to have lunch with him. Since this was at the height of the Yezhovshchina

, and any Soviet citizen who had any unauthorized contact with a foreigner was likely to be regarded as a spy, the NKVD

arrested and executed Prince Mirsky as a British spy. As part of the same trip that took Carr to the Soviet Union in 1937 was a visit to Germany. In a speech given on October 12, 1937 at the Chatham House

summarizing his impressions of those two countries, Carr reported that Germany was "…almost a free country". Unaware apparently of the fate of his friend, Carr spoke in his speech of the "strange behaviour" of his old friend, Prince Mirsky, who had at first gone to great lengths to try to pretend that he did not know Carr during their accidental meeting in Leningrad. Carr ended his speech by arguing that it was unfair for people in Britain to criticize either of the two dictatorships, who, Carr asserted, were only reacting to the problems of the Great Depression. Carr stated:

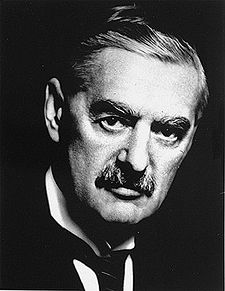

In the 1930s, Carr was a leading supporter of appeasement

. In the 1930s, Carr saw Germany as the victim of the Versailles treaty, and Hitler as a typical German leader, attempting like every other previous German leader since 1919 to overthrow that settlement. In his writings on international affairs in British newspapers, Carr criticized the Czechoslovak President Edvard Beneš

for clinging to the alliance with France, rather than accepting that it was his country's destiny to be in the German sphere of influence. At the same time, Carr strongly praised the Polish Foreign Minister Colonel Józef Beck

, who with his balancing act between France, Germany, and the Soviet Union as "a realist who grasped the fundamentals of the European situation" and argued that his polices were "from the Polish point of view...brilliantly successful". Starting in the late 1930s, Carr started to become even more sympathetic toward the Soviet Union, as Carr was much impressed by the apparent achievements of the Five-Year Plans, which stood in marked contrast to the seeming failures of capitalism in the Great Depression

.

His famous work The Twenty Years' Crisis

His famous work The Twenty Years' Crisis

was published in July 1939, which dealt with the subject of international relations between 1919 and 1939. In that book, Carr defended appeasement under the grounds that it was the only realistic policy option. At the time the book was published in the summer of 1939, Neville Chamberlain

had adopted his "containment" policy towards Germany, leading Carr to later ruefully comment that his book was dated even before it was published. In the spring and summer of 1939, Carr was very dubious about Chamberlain's "guarantee" of Polish independence issued on March 31, 1939, which he regarded as an act of folly and madness. In April 1939, Carr wrote in opposition to Chamberlain's "guarantee" of Poland that: "The use or threatened use of force to maintain the status quo may be morally more culpable than the use or threatened use of force to alter it".

In The Twenty Year's Crisis, Carr divided thinkers on international relations into two schools, which he labelled the realists and the utopians. Reflecting his own disillusion with the League of Nations, Carr attacked as "utopians" those like Norman Angell

who believed that a new and better international structure could be built around the League. In Carr's opinion, the entire international order constructed at Versailles was flawed and the League was a hopeless dream that could never do anything practical.

Carr argued against the view that the problems of the world in 1939 were the work of a clique of evil men and dismissed Arnold J. Toynbee

's view that "we are living in an exceptionally wicked age". Carr asserted that the problems of the world in 1939 were due to structural political-economic problems that transcended the importance of individual national leaders and argued that the focus on individuals as causal agents was equivalent to focusing on the trees rather the forest. Carr contended that the 19th century theory of a balance of interests amongst the powers was an erroneous belief and instead contended that international relations was an incessant struggle between the economically privileged "have" powers and the economically disadvantaged "have not" powers. In this economic understanding of international relations, "have" powers like the United States, Britain and France were inclined to avoid war because of their contented status whereas "have not" powers like Germany, Italy and Japan were inclined towards war as they had nothing to lose. In Carr's opinion, ideological differences between fascism and democracy were beside the point as he used as an example Japan, which Carr argued was not a fascist state but still a "have not" power. Carr attacked Adam Smith

for claiming there was a "harmony of interests" between the individual and their community, writing that "the doctrine of the harmony of interests was tenable only if you left out of account the interests of the weak who must be driven to the wall". Carr claimed after World War I, the American President Woodrow Wilson

had unfortunately created an international order based on the doctrine of "harmony of interests" through the "utopian" instrument of the League of Nations with disastrous results. Carr argued that the only way to make the League (which Carr otherwise held in complete contempt by 1939) an effective force for peace was to persuade Germany, Italy and Japan to return to the League by promising them that their economic grievances could and would be worked out at the League. Carr called The Twenty Year's Crisis:

and later adopted by Benito Mussolini

of the natural conflict between "proletarian" nations like Italy and "plutocratic" nations like Britain. In The Twenty Years' Crisis, Carr wrote:

In The Twenty Years' Crisis, Carr argued that the entire peace settlement of 1919 was flawed by the decisions of the British Prime Minister David Lloyd George

, the French Premier Georges Clemenceau

and above all the American President Woodrow Wilson

to impose a sterile international order in the post-war world. In particular, Carr claimed that what he saw as the basis of the post-1919 international order, namely the combination of 19th century style laissez-faire capitalism and the nationalism inspired by the principle of national self-determination

, made for a highly defective peace settlement, and hence a very dangerous world. Carr later wrote that:

In Carr's opinion, the repeated demands made by Adolf Hitler

for lebensraum

(living space) was merely a reflection of the fact that Germany was a "have not" power (like many in interwar Britain, Carr misunderstood the term lebensraum as referring to a zone of exclusive economic influence for Germany in Eastern Europe). In Carr's view, the belligerence of the fascist powers was the "natural cynical reaction" to the empty moralizing of the "have" powers, who refused to make any concessions until the state of international relations had been allowed to seriously deteriorate. Carr argued that on moral and practical grounds the Treaty of Versailles

had done a profound wrong to Germany and that the present state of world tensions in 1939 was caused by the inability and/or unwillingness of the other powers to readdress that wrong in a timely fashion. Carr defended the Munich Agreement

as the overdue recognition of changes in the balance of power. In The Twenty Years' Crisis, Carr was highly critical of Winston Churchill

, whom Carr described as a mere opportunist interested only in power for himself. Writing of Churchill's opposition to appeasement, Carr stated

In the same book, Carr described the opposition of realism and utopianism in international relations as a dialectic progress. Carr described realism as the acceptance that what exists is right and the belief that there is no reality or forces outside history such as God

. Carr argued that in realism there is no moral dimension and that what is successful is right and that what is unsuccessful is wrong. Carr argued that for realists there are no basis for moralizing about the past, present or the future and that "World history is the World Court". Carr rejected both utopianism and realism as the basis of a new international order and instead called a synthesis of the two. Carr wrote that:

Norman Angell

Norman Angell

, one of the "utopian" thinkers attacked by in The Twenty Years' Crisis called the book a "completely mischievous piece of sophisticated moral nihilism" In a review, Angell commented that Carr's claim that international law was only a device for allowing "have" nations to maintain their privileged position provided "aid and comfort in about equal degree to the followers of Marx and the followers of Hitler".Angell maintained that Carr's claim that "resistance to aggression" was only an empty slogan on the part of the "have" nations meant only for keeping down the "have not" nations was a "veritable gold mine for Dr. Goebbels". In response to The Twenty Years' Crisis, Angell wrote a book entitled Why Freedom Matters intended to rebut Carr. Another of the "utopian" thinkers attacked by Carr, Arnold J. Toynbee

wrote that reading The Twenty Years' Crisis left one "in a moral vacuum and at a political dead point". Another "utopian", the British historian R.W. Seton-Watson

wrote in response that it was "simply farcical" that Carr could write of morality in international politics without mentioning Christianity once in his book. In a 2004 speech, the American political scientist John Mearsheimer

praised the The Twenty Years' Crisis and argued that Carr was correct when he claimed that international relations was a struggle of all against all with states always placing their own interests first. Mearsheimer maintained that Carr’s points were still as relevant for 2004 as for 1939 and went on to deplore what he claimed was the dominance of “idealist” thinking about international relations among British academic life

Carr immediately followed up The Twenty Year's Crisis with Britain : A Study Of Foreign Policy From The Versailles Treaty To The Outbreak Of War, a study of British foreign policy in the inter-war period that featured a preface by the Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax

. Carr ended his support for appeasement, which had so vociferously expressed in The Twenty Year's Crisis in the late summer of 1939 with a favourable review of a book containing a collection of Churchill's speeches from 1936–38, which Carr wrote were "justifiably" alarmist about Germany. After 1939, Carr largely abandoned writing about international relations in favour of contemporary events and Soviet history. Carr was to write only three more books about international relations after 1939, namely The Future Of Nations; Independence Or Interdependence? (1941), German-Soviet Relations Between The Two World Wars, 1919–1939 (1951) and International Relations Between The Two World Wars, 1919–1939 (1955). After the outbreak of World War II, Carr stated that he was somewhat mistaken in his prewar views on Nazi Germany. In the 1946 revised edition of The Twenty Years' Crisis, Carr was more hostile in his appraisal of German foreign policy then he had been in the first edition in 1939. Through The Twenty Years' Crisis was published just months before World War II began, the Japanese historian Saho Matusumoto wrote that in a sense, Carr's book began the debate on the origins of World War II.

Some of the major themes of Carr's writings were change and the relationship between ideational and material forces in society. Carr saw a major theme of history was the growth of reason

as a social force. Carr argued that all major social changes had been caused by revolutions or wars, both of which Carr regarded as necessary but unpleasant means of accomplishing social change. Carr saw his major task in all of writings of finding a better way of working out social transformations. Carr maintained that every revolution starting with the French Revolution

had helped to move humanity in a progressive direction but had failed to complete their purpose because of the lack of the essential instruments to finish the revolutionary project. Carr asserted that social changes had to be linked with a realistic understanding of the limitations of social changes in order to build lasting institutions capable of maintaining social change. Carr claimed that in modern industrial society that a dialogue between various social forces was the best way of achieving a social transformation "toward goals which can be defined only as we advance towards them, and the validity of which can only be verified in a process of attaining them".

working as a clerk with the propaganda department of the Foreign Office. As Carr did not believe Britain could defeat Germany, the declaration of war on Germany on September 3, 1939 left him highly depressed.

In March 1940, Carr resigned from the Foreign Office to serve as the writer of leaders (editorials) for The Times

. In his second leader published on June 21, 1940 entitled "The German Dream", Carr wrote that Hitler was offering a "Europe united by conquest". Carr went on to write:

under the grounds that this was "not merely pressure from Moscow, but sincere recognition that this was a better alternative than absorption into a new Nazi Europe".

Carr served as the assistant editor of The Times

from 1941 to 1946, during which time he was well known for the pro-Soviet attitudes that he expressed in his leaders (editorials) he wrote. After June 1941, Carr' s already strong admiration for the Soviet Union was much increased by the Soviet Union's role in defeating Germany.

In one of his first leaders Carr for the Times, he declared:

, who felt that Carr was taking the Times in a too radical direction, which led Carr for a time being restricted only to writing on foreign policy. After Dawson's ouster in May 1941 and his replacement with Robert M'Gowan Barrington-Ward

, Carr was given a free rein to write on whatever he wished. In turn, Barrington-Ward was to find many of Carr's leaders on foreign affairs to be too radical for his liking.

Carr's leaders were noted for their advocacy of a socialist European economy under the control of an international planning board, and for his support for the idea of an Anglo-Soviet alliance as the basis of the post-war international order. In one of his leaders, Carr stated "The new order cannot be based on the preservation of privilege, whether the privilege be that of a country, of a class, or of an individual." Carr himself later described his attitude to the Soviets during his stint at the Times:

with Germany, and argued for a post-war reconstruction of Germany along socialist lines. In Carr's opinion, National Socialism was not the natural result of Deutschtum (Germanism), but rather of capitalism. Carr claimed that once capitalism was removed from German society, the social forces that gave birth to fascism

would wither away and die. On his leaders on foreign affairs, Carr was very consistent (and correct) in arguing after 1941 that once the war ended, it was the fate of Eastern Europe

to come into the Soviet sphere of influence, and claimed that any effort to the contrary was both vain and immoral. In a leader of August 1941 entitled "Peace and Power", Carr wrote that power in Eastern Europe:

(who had criticized Carr's views about the Baltic states) on January 16, 1942 Carr wrote:

Between 1942–45, Carr was the Chairman of a study group at the Royal Institute of International Affairs

concerned with Anglo-Soviet relations. Carr's study group concluded that Stalin had largely abandoned Communist ideology in favour of Russian nationalism, that the Soviet economy would provide a higher standard of living in the Soviet Union after the war, and it was both possible and desirable for Britain to reach a friendly understanding with the Soviets once the war had ended. In 1942, Carr published Conditions of Peace

followed by Nationalism and After

in 1945, in which he outlined his ideas about the post-war world should look like. In his books, and his Times leaders, Carr urged for the post-war world, the creation of a socialist European federation anchored by an Anglo-German partnership that would be aligned with, but not subordinated to the Soviet Union against the country that Carr saw as the principal post-war danger to world peace, namely the United States.

In his 1942 book Conditions of Peace, Carr argued that it was a flawed economic system that had caused World War II and that the only way of preventing another world war was for the Western powers to fundamentally change the economic basis of their societies by adopting socialism

. Carr argued that the post-war world required a European Planning Authority and a Bank of Europe that would control the currencies, trade, and investment of all the European economies. One of the main sources for ideas in Conditions of Peace was the 1940 book Dynamics of War and Revolution by the American Lawrence Dennis

In a review of Conditions of Peace, the British writer Rebecca West

criticised Carr for using Dennis as a source, commenting "It is as odd for a serious English writer to quote Sir Oswald Mosley" In a speech on June 2, 1942 in the House of Lords

, Viscount Elibank

attacked Carr as an "active danger" for his views in Conditions of Peace about a magnanimous peace with Germany and for suggesting that Britain turn over all of her colonies to an international commission after the war.

In a leader of March 10, 1943 Carr wrote that:

The next month, Carr's relations with the Polish government were further worsted by the storm caused by the discovery of the Katyn Forest massacre

The next month, Carr's relations with the Polish government were further worsted by the storm caused by the discovery of the Katyn Forest massacre

committed by the NKVD

in 1940. In a leader entitled "Russia and Poland" on April 28, 1943, Carr blasted the Polish government for accusing the Soviets of committing the Katyn Forest massacre, and for asking the Red Cross to investigate Carr wrote that:

In 1943, the Classicist Gilbert Murray

wrote a letter to Carr, who was still the Woodrow Wilson Professor of International Relations at Aberystwyth complaining on behalf of Lord Davies

that:

In December 1944, when fighting broke out in Athens

, Greece between the Greek Communist front organization ELAS and the British Army

, Carr in a Times leader sided with the Greek Communists, leading to Winston Churchill

to condemn him in a speech to the House of Commons. Churchill called Carr's leader defending E.L.A.S "a melancholy document" that in his opinion reflected the decline of British journalism. Carr claimed (correctly) that the Greek EAM was the "largest organised party or group of parties in Greece" that "appeared to exercise almost unchallengeable authority" and called for Britain to recognize the EAM as the legal Greek government. The Anglo-American historian Robert Conquest

accused Carr of hypocrisy in supporting the EAM/ELAS, noting Carr was violating his own "Might is Right" precepts of international power politics, in which the stronger power was always in the right, regardless of the facts of the case. Since Britain was a much stronger power in the world than the Greek Communists, Conquest argued that Carr by his own standards should have been on the British side during the fighting in Athens in December 1944.

In contrast to his support for E.A.M/E.L.A.S, Carr was strongly critical of the Polish government in exile and its Armia Krajowa

(Home Army) resistance organization. In his leaders of 1944 on Poland, Carr urged that Britain break diplomatic relations with the London government and recognize the Soviet sponsored Lublin government

as the lawful government of Poland. In a Times leader of February 10, 1945, Carr questioned whatever the Polish government in exile even had the right to speak on behalf of Poland Carr wrote that it was extremely doubtful about whatever the London government had "an exclusive title to speak for the people of Poland and a liberum veto

on any move towards a settlement of Polish affairs" Carr went to argue that "The legal credentials of this Government are certainly not beyond challenge if it were relevant to examine them: the obscure and tenuous thread of continuity leads back at best to a constitution deriving from a quasi-Fascist coup d'état" Carr ended his leader with the claim that "What Marshal Stalin desires to see in Warsaw is not a puppet government acting under Russian orders, but a friendly government which fully conscious of the supreme impotence of Russo-Polish concord, will frame its independent policies in that context."

In a May 1945 leader, Carr blasted those who felt that an Anglo-American "special relationship' would be the principal bulwark of peace, writing that:

(the price of the Daily Worker was one penny). Commenting on Carr's pro-Soviet leaders, the British writer George Orwell

wrote in 1942 that:

Carr was to elaborate on these ideas he had first advocated in Conditions of Peace in his 1945 book Nationalism and After. In that book, Carr wrote "The driving force behind any future international order must be a belief...in the value of individual human beings irrespective of national affinities or allegiance." Carr argued that just as the military was under civilian control, that likewise so should "the holders of economic power...be responsible to, and take their orders from, the community in exactly the same way". Carr claimed it was necessary to create "maximum social and economic opportunity" for all, and argued that this would be achieved via an international planning authority that would control the world economy, and provide for "increased consumption for social stability and equitable distribution for maximum production". Carr described his views at the time as:

In 1945 during a lecture series entitled The Soviet Impact on the Western World, which were published as a book in 1946, Carr argued that "The trend away from individualism and towards totalitarianism is everywhere unmistakable", that Marxism

In 1945 during a lecture series entitled The Soviet Impact on the Western World, which were published as a book in 1946, Carr argued that "The trend away from individualism and towards totalitarianism is everywhere unmistakable", that Marxism

was the by far the most successful type of totalitarianism

as proved by Soviet industrial growth and the Red Army

's role in defeating Germany and that only the "blind and incurable ignored these trends". During the same lectures, Carr called democracy

in the Western world a sham, which permitted a capitalist ruling class to exploit the majority, and praised the Soviet Union as offering real democracy. Carr claimed that Soviet social policies were far more progressive than Western social policies, and argued democracy was more about social equality than political rights. During the same series of lectures, Carr argued that:

In 1946, Carr started living with Joyce Marion Stock Forde, who was to remain his common law wife until 1964. In 1947, Carr was forced to resign from his position at Aberystwyth. The Marxist historian Christopher Hill

In 1946, Carr started living with Joyce Marion Stock Forde, who was to remain his common law wife until 1964. In 1947, Carr was forced to resign from his position at Aberystwyth. The Marxist historian Christopher Hill

wrote that in the late 1940s "it was thought, or pretended to be thought, that any irregularity in one's matrimonial position made it impossible for one to be a good scholar or teacher." In November 1946, Carr was involved in a radio debate with Arnold J. Toynbee

on Britain's position in the world. Through Carr expressed support for Toynbee's idea of British neutrality in the emerging Cold War, Carr rejected his idea that Britain "liquidate without too many qualms our political commitments and economic outposts in other continents". Carr declared that "The trouble about politics and economics is that if you run away from them they are apt to run after you-especially if you occupy as Britain does, a conspicuous and coveted and vulnerable position". In the late 1940s, Carr started to become increasingly influenced by Marxism

. His name was on Orwell's list

, a list of people which George Orwell

prepared in March 1949 for the Information Research Department

, a propaganda unit set up at the Foreign Office by the Labour government. Orwell considered these people to have pro-communist leanings and therefore to be inappropriate to write for the IRD.

In May–June 1951, Carr delivered a series of speeches on British radio entitled The New Society, attacked capitalism as a great social evil and advocated a planned economy with the British state controlling every aspect of British economic life. Carr was a reclusive man who few knew well, but some of his circle of close friends included Isaac Deutscher

, A. J. P. Taylor

, Harold Laski

and Karl Mannheim

. Carr was especially close to Deutscher. Deutscher's widow was later to write of the deep, if unlikely friendship that was stuck between:

In 1948, Carr condemned British acceptance of an American loan in 1946 as the marking the effective end of British independence. Carr wrote that:

Throughout the remainder of Carr's life after 1941, his outlook was basically sympathetic towards Communism and its achievements. In the early 1950s, when Carr sat on the editorial board of the Chatham House, he attempted to block the publication of the manuscript that eventually became The Origins of the Communist Autocracy by Leonard Schapiro

under the grounds that the subject of repression in the Soviet Union was not a serious topic for a historian. As interest in the subject in Communism grew, Carr largely abandoned international relations

as a field of study. In part, Carr's turn away from international relations was due to his increasing scepticism about the subject. In 1959, Carr wrote to his friend and protégé Arno J. Mayer

, shortly after he began teaching international relations at Harvard warning against attempts to turn international relations into a separate subject apart from history, which Carr viewed as a foolish attempt to sever a sub-discipline of history by turning it into a discipline of its own. In 1956, Carr did not comment about the Soviet suppression of the Hungarian Uprising while at the same time condemning the Suez War

.

In his few books about international relations after 1938, despite a change in emphasis, Carr's pro-German views regarding inter-war international relations continued. For an example, in his 1955 book International Relations Between the Two World Wars, 1919–1939, Carr claimed that the German default on timber reparations

in December 1922, which sparked the 1923 Ruhr crisis

, was very small and explained that the French reaction in occupying the Ruhr

was grossly disproportionate to the offence. As the American historian Sally Marks noted, even in 1955 this was a long-discredited pro-German "myth", and that in fact the German default was enormous, and Germany had been defaulting on a large scale and a frequent basis since 1921.

In 1966, Carr left Forde and married the historian Betty Behrens. That same year, Carr wrote in an essay that in India where "liberalism is professed and to some extent practised, millions of people would die without American charity. In China, where liberalism is rejected, people somehow get fed. Which is the more cruel and oppressive regime?" One of Carr's critics, the British historian Robert Conquest

, commented that Carr did not appear to be familiar with recent Chinese history, because, judging from that remark, Carr seemed to be ignorant of the millions of Chinese who had starved to death during the Great Leap Forward

. In 1961, Carr published an anonymous and very favourable review of his friend A. J. P. Taylor

's contentious book The Origins of the Second World War, which caused much controversy. In the late 1960s, Carr was one of the few British professors to be supportive of the New Left

student protestors, who, he hoped, might bring about a socialist revolution in Britain. In a 1969 introduction to the collection of essays, Heretics and Renegades and Other Essays by Carr's friend, Isaac Deutscher

, Carr endorsed Deutscher's attack on George Orwell

's novel Nineteen Eighty-Four

on the grounds that Nineteen Eighty-Four could not be an accurate picture of the Soviet Union as Orwell had never visited that state.

Carr exercised wide influence in the field of Soviet studies and international relations. The extent of Carr's influence could be seen in the 1974 festschrift

in his honour, entitled Essays In Honour of E.H. Carr ed. Chimen Abramsky

and Beryl Williams. The contributors included Sir Isaiah Berlin

, Arthur Lehning

, G.A. Cohen, Monica Partridge, Beryl Williams, Eleonore Breuning, D.C. Watt, Mary Holdsworth, Roger Morgan

, Alec Nove, John Erickson

, Michael Kaser, R.W. Davies, Moshe Lewin

, Maurice Dobb

, and Lionel Kochan

. The contributors examined such topics as the social views of Georges Sorel

, Alexander Herzen

and Mikhail Bakunin

; the impact of the Revolution of 1905 on Russian foreign policy, Count Ulrich von Brokdorff-Rantzau

and German-Soviet relations; and developments in the Soviet military, education, economy and agriculture in the 1920s–1930s. Another admirer of Carr is the American Marxist historian Arno J. Mayer

, who has stated that his work on international relations owes much to Carr.

During his last years, Carr continued to maintain his optimism in a better future, in spite of what he regarded as grave setbacks. In a 1978 interview in The New Left Review, Carr called capitalism a crazy economic system that was doomed to die. In the same interview, Carr complained about what he called "obsessive hatred and fear of Russia", stating "an outburst of national hysteria on this scale is surely the symptom of a sick society". In a 1980 letter to his friend, Tamara Deutscher, Carr wrote that he felt that the government of Margaret Thatcher

had forced "the forces of Socialism" in Britain into a "full retreat". In the same letter to Deutscher, Carr wrote that "Socialism cannot be obtained through reformism, i.e. through the machinery of bourgeois democracy". Carr went on to decry disunity on the Left, and wrote:

in China in the late 1970s as a regressive development, he saw opportunities, and wrote to his stock broker in 1978: "a lot of people, as well as the Japanese, are going to benefit from the opening up of trade with China. Have you any ideas?". In one of his last letters to Tamara Deutscher, shortly before his death in 1982, Carr expressed a great deal of dismay at the state of the world, writing that "The left is foolish and the right vicious." Carr wrote to Deutscher that the sort of socialism envisioned by Marx could never be achieved via the means of democracy, but complained that the working class in Britain were not capable of staging the revolution needed to destroy British capitalism. Carr criticized what he regarded as an excessive preoccupation in the West with the human rights situation in the Soviet Union, blasted the European Left for naïveté, and Eurocommunism

as a useless watered-down version of Communism. Carr wrote to Deutscher:

A latter day controversy concerning Carr surrounds the question of whether he was an anti-Semite. Carr's critics point to the fact that he was champion in succession of two anti-Semitic dictators, namely Hitler and Stalin, his opposition to Israel

, and to the fact that most of Carr's opponents such as Sir Geoffrey Elton, Leonard Schapiro

, Sir Karl Popper

, Bertram Wolfe

, Richard Pipes

, Adam Ulam

, Leopold Labedz

, Sir Isaiah Berlin

, and Walter Laqueur

were Jewish. Carr's defenders such as Jonathan Haslam have argued against the charge of anti-Semitism, noting that Carr had many Jewish friends (including such erstwhile intellectual sparring partners such as Berlin and Namier), that his last wife Betty Behrens was Jewish and that his support for Nazi Germany in the 1930s and the Soviet Union in the 1940s–50s was in spite rather than because of anti-Semitism in those states.

from 1953 to 1955 when he became a fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge

. In the 1950s, Carr was well known as an outspoken admirer of the Soviet Union. Carr's writings include his History of Soviet Russia (14 vol., 1950–78). During World War II, Carr was favourably impressed with what he regarded as the extraordinary heroic performance of the Soviet people, and towards the end of 1944 Carr decided to write a complete history of the Soviet Russia from 1917 comprising all aspects of social

, political

and economic history

in order to explain how the Soviet Union withstood the challenge of the German invasion. The resulting work was his 14 volume History of Soviet Russia, which took the story up to 1929. Carr initially intended the series to begin in 1923 with a long chapter summarizing the state of the Soviet Union just before Lenin's death. Carr found that the idea of one chapter on the situation in the Soviet Union in the year 1923 "proved on examination almost ludicrously inadequate to the magnitude of Lenin's achievement and of its influence on the future".

Carr's friend and close associate, the British historian R.W. Davies, was to write that Carr belonged to the anti-Cold-War school of history, which regarded the Soviet Union as the major progressive force in the world, the United States as the world's principal obstacle to the advancement of humanity, and the Cold War

as a case of American aggression against the Soviet Union. In 1950, Carr wrote in the defence of the Soviet Union that:

argument, Carr criticized those WASP historians who, he felt, had unfairly judged the Soviet Union by the cultural norms of Britain and the United States. In 1960, Carr wrote that:

Carr began his magnum opus by arguing that the 1917 October Revolution was a "proletarian revolution" forced on the Bolsheviks. Carr argued that:

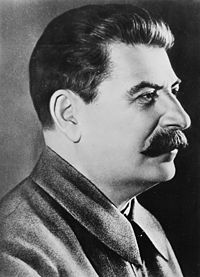

In Carr's view, Soviet history

went through three periods in the inter-war era and was personified by the change of leadership from Vladimir Lenin

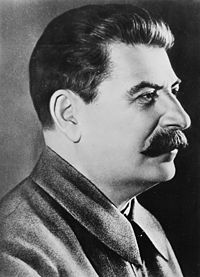

to Joseph Stalin

. After an initial period of chaos, Carr wrote that the dissolution of the Constituent Assemby

in January 1918 was the last "tearing asunder of the veil of bourgeois constitutionalism", and that henceforward, the Bolsheviks would rule Russia their own way. Carr, like many others, argued that the emergence of Russia from a backward peasant economy to a leading industrial power was the most important event of the 20th century. The first part of a History of Soviet Russia comprised three volumes entitled The Bolshevik Revolution, published in 1950, 1952, and 1953, and traced Soviet history from 1917 to 1922. During the writing of the first volumes of The History of Soviet Russia, Deutscher had much influence on Carr's understanding of the period. The second part was intended to comprise three volumes called The Struggle for Power, which was intended to cover the years 1922–28, but Carr instead to decided to publish a single volume labelled The Interregnum that covered the events of 1923–24, and another four volumes entitled Socialism In One Country, which took the story up to 1926. The final volumes in the series were entitled The Foundations of the Planned Economy, which covered the years until 1929. Originally, Carr had planned to take the series up to Operation Barbarossa

in 1941 and the Soviet victory of 1945, but his death in 1982 put an end to the project.

Carr argued that Soviet history went through three periods in the 1917–45 era. In the first phrase was the war communism

Carr argued that Soviet history went through three periods in the 1917–45 era. In the first phrase was the war communism

era (1917–21), which saw much rationing, economic production focused into huge centres of manufacturing, critical services and supplies being sold at either set prices or for free, and to a large extent a return to a barter economy. Carr contended that the problems in the agrarian sector forced the abandonment of war communism in 1921, and its replacement by the New Economic Policy

(NEP). During the same period saw what Carr called one of Lenin's "astonishing achievements", namely the gathering together of nearly all of the former territories of Imperial Russia (with the notable exceptions of Finland, Poland, Lithuania

, Latvia

and Estonia

) under the banner of the Soviet Union. In the NEP period (1921–28), Carr maintained that the Soviet economy became a mixed capitalist-socialist one with peasants after fulfilling quotas to the state being allowed to sell their surplus on the open market, and industrialists being permitted be allowed to produce and sell agricultural and light industrial goods. Carr contended that the post-Lenin succession struggle after 1924 was more about personal disputes than ideological quarrels. In Carr's opinion, "personalities rather than principles were at stake". Carr argued that the victory of Stalin over Leon Trotsky

in the succession struggle was inevitable because Stalin was better suited to the new order emerging in the Soviet Union in the 1920s than Trotsky. Carr stated "Trotsky was a hero of the revolution. He fell when the heroic age was over." Carr argued that Stalin had stumbled into the doctrine of "Socialism in One Country

" more by accident than by design in 1925, but argued that Stalin was swift to grasp how effective the doctrine was as a weapon to beat Trotsky with. Carr wrote

and the OGPU. Writing of the OGPU, Carr noted that since the Bolsheviks had eliminated all of their enemies outside of the Party by the mid-1920s: "The repressive powers of the OGPU were henceforth directed primarily against opposition in the party, which was the only effective form of opposition in the state." Reflecting his background as a diplomat and scholar on international relations, Carr provided very detailed treatment of foreign affairs with a focus on both the Narkomindel and the Comintern

. In particular, Carr examined the relationship between the Soviet Communist Party and the other Communist parties around the world, the Comintern's structure, the Soviet reaction to the Locarno Treaties

, and the early efforts (ultimately successful in 1949) to promote a revolution in China.

The third phrase was the period of the Five Year Plans beginning with the First Five-Year Plan

in 1928, which saw the Soviet state promoting the growth of heavy industry, eliminating private enterprise, collectivising agriculture, and of quotes for industrial production being set in Moscow. In Carr's opinion, the changes wrought by the First Five Year were a positive development. Carr argued that the economic system that existed during the N.E.P. period was highly inefficient, and that any economic system based on planning by the state was superior to what Carr saw as the disorganized chaos of capitalism. Carr accepted the Soviet claim that the so-called "kulak

s" existed as a distinct class, that they were a negative social force, and as such, the "dekulakisation" campaign that saw at least 2 million alleged "kulaks" deported to the Gulag

in 1930–32 was a necessary measure that improved the lives of the Soviet peasantry. R.W. Davies, Carr's associate and co-writer on the History of Soviet Russia expressed some doubts to Carr about whatever the "kulaks" actually existed, and thought the term was more an invention of Soviet propaganda than a reflection of the social conditions in the Soviet countryside.

Accompanying these social-economic changes were the changes in the leadership. Carr argued that Lenin saw himself as the leader of an elite band of revolutionaries who sought to give power to the people and wanted a world revolution. By contrast, Carr claimed that Stalin was a bureaucratic leader who concentrated power in his own hands, ruled in a ruthless fashion, carried a policy of "revolution from above", and by promoting a merger of Russian nationalism

and Communism

cared more for the interests of the Soviet Union than for the world Communist movement. However, Carr argued that Stalin's achievements in the making the Soviet Union a great industrial power by and large outweighed any of the actions for which he is commonly criticized for. Carr claimed that Stalin played both the roles of dictator and emancipator simultaneously, and argued that this reflected less than the man then the times and place in which he lived. Writing of Stalin, Carr claimed "Few great men have been so conspicuously as Stalin the product of the time and place in which they live." Carr claimed that if even Lenin had not died in 1924, history would still had worked out the same. In 1978, Carr claimed that if Lenin were still alive in 1928, he "would have faced exactly the same problems" as did Stalin, and had chosen the same solution, namely the "revolution from above". But Carr argued that Lenin would had been able to "minimize and mitigate the element of coercion" in the "revolution from above". As a result, Carr wrote that: "Stalin's personality, combined with the primitive and cruel traditions of the Russian bureaucracy, imparted to the revolution from above a particularly brutal quality."

A book that was not part of the History of Soviet Russia series, though closely related due to common research in the same archives was Carr's 1951 book German-Soviet Relations Between the Two World Wars, 1919–1939. In that book, Carr blamed the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain

for the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of 1939 Carr accused Chamberlain of deliberately snubbing Joseph Stalin

's offers of an alliance, and as such, the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

, which partitioned much of Eastern Europe

between Germany and the Soviet Union was under the circumstances the only policy the Soviets could have followed in the summer of 1939 Following the official interpretation of the reasons for the German-Soviet pact in the Soviet Union, Carr went to accuse Chamberlain of seeking to direct German aggression against the Soviet Union in 1939. Carr argued that Chamberlain was pursuing this alleged policy of seeking to provoke a German-Soviet war as a way of deflecting German attention from Western Europe and because of his supposed anti-Communist phobias. Carr argued that the British "guarantee" of Poland given on March 31, 1939 was a foolhardy move that indicated Chamberlain's preference for an alliance with Poland as opposed to an alliance with the Soviet Union. In Carr's opinion, the sacking of Maxim Litvinov

as Foreign Commissar on May 3, 1939 and his replacement with Vyacheslav Molotov

indicated not a change in Soviet foreign policy from the collective security approach that Litvinov had championed as many historians argue, but was rather Stalin's way of engaging in hard bargaining with Britain and France. Carr argued that the Anglo-French delegation sent to travel on Moscow on the slow ship City of Exeter in August 1939 to negotiate the "peace front" as the proposed revived Triple Entente

was called, were unimpressive diplomats and their unwillingness and inability to pressure the Poles to grant to transit rights to the Red Army

reflected a fundamental lack of interest in reaching an alliance with the Soviet Union. By contrast, Carr argued that the willingness of the German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop

to come to Moscow anytime via aero-plane with full powers to negotiate whatever was necessary to secure a German-Soviet alliance reflected the deep German interest in reaching an understanding with the Soviets in 1939. Carr defended the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact under the grounds that: "In return for 'non-intervention' Stalin secured a breathing space of immunity from German attack." According to Carr, the "bastion" created by means of the Pact, "was and could only be, a line of defence against potential German attack." An important advantage (projected by Carr) was that "if Soviet Russia had eventually to fight Hitler, the Western Powers would already be involved." In an implicit broadside against the idea of West German membership in NATO (a controversial subject in the early 1950s) and Atlanticism

, Carr concluded his book with the argument that ever since 1870 German foreign policy had always been successful when the Reich was aligned with Russia and unsuccessful when aligned against Russia, and expressed hope that the leaders of the then newly founded Federal Republic would understand the lessons of history.

In 1955, a major scandal that damaged Carr's reputation as a historian of the Soviet Union occurred when he wrote the introduction to Notes for a Journal, the supposed memoir of the former Soviet Foreign Commissar Maxim Litvinov

In 1955, a major scandal that damaged Carr's reputation as a historian of the Soviet Union occurred when he wrote the introduction to Notes for a Journal, the supposed memoir of the former Soviet Foreign Commissar Maxim Litvinov

that was shortly there afterwards was exposed as a forgery. Notes for a Journal was a KGB

forgery written in the early-1950s by a former Narkomindel official turned Chekist forger named Grigori Besedovsky specializing in forgeries designed to fool gullible Westerns. The American historian Barry Rubin

argued it can be easily be established that Notes for a Journal was an anti-Semitic forgery in that in the Notes Litvinov was portrayed as a proud Jew whereas the real Litvinov did not see himself as Jewish at all, and more importantly the Notes showed Litvinov together with other Soviet officials of Jewish origin working behind the scenes for Jewish interests in the Soviet Union. Rubin also noted other improbabilities in Notes for a Journal such having Litvinov meeting regularly with rabbis in order to further Jewish interests, describing Aaron Soltz

as the son of a rabbi whereas he was the son of a merchant and having those Soviet officials of Jewish origin be referred to by their patronyms

. Rubin argued that this portrayal of Litvinov reflected Soviet anti-Semitism, and that Carr was amiss in not recognizing Notes for a Journal as the anti-Semitic forgery it was.

The first volume of A History of Soviet Russia published in 1950 was criticized by some historians, most notably the British Marxist historian Isaac Deutscher

(who was a close friend) as being too concerned with institutional development of the Soviet state, and for being impersonal and dry, capturing little of the tremendous emotions of the times. Likewise, Carr was criticized from both left and right for his downplaying of the importance of ideology for the Bolsheviks, and his argument that the Bolsheviks thought in only in terms of Russia rather than the entire world. In a 1955 article, Deutscher argued that:

contended in 1955 that:

noted that Carr had a strong preference for Lenin the politician attempting to build a new order in Russia after 1917 vs. Lenin the revolutionary working to destroy the old order before 1917 The scope and scale of History of Soviet Russia was illustrated in a letter Carr wrote to Tamara Deutscher, where in one volume Carr wished to examine Soviet relations with all of the Western nations between 1926–29, relations between the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Western Communist parties; efforts to promote a "World Revolution"; the work and the "machinery" of the Comintern

and the Profintern

, Communist thinking on the "Negro Question" in the United States, and the history of Communist parties in China, Outer Mongolia

, Turkey

, Egypt

, Afghanistan

, and the Dutch East Indies

.

A recurring theme of Carr's writings on Soviet history was his hostility towards those who argued that Soviet history could have taken different courses from what it did. In a 1974 book review of the American historian Stephen F. Cohen's biography of Nikolai Bukharin

published in the Times Literary Supplement, Carr lashed out against Cohen for advocating the thesis that Bukharin represented a better alternative to Stalin. Carr dismissed Cohen's argument that the NEP was a viable alternative to the First Five Year Plan, and contemptuously labelled Bukharin a weak-willed and a rather pathetic figure who was both destined and deserved to lose to Stalin in the post-Lenin succession struggle. Carr ended his review by attacking Cohen as typical of the American left, who, Carr claimed, were a group of ineffective, woolly-headed idealists who, in a reference to the recent Watergate scandal

, could not even bring down Richard Nixon

, whom Carr charged had brought himself down while the American left did nothing useful to facilitate that event. Carr ended his review with the scornful remark that since the American left could produce nothing but "losers" like George McGovern

, so it was natural that an American leftist like Cohen would sympathize with Bukharin, whom Carr likewise regarded as a great "loser" of history.

Carr's last book, 1982's The Twilight of the Comintern, though not officially a part of the History of Soviet Russia series, was regarded by Carr as the completion of the series. In this book, Carr examined the response of the Comintern to fascism in the years 1930–1935. Carr claimed that the failure of the Austrian-German customs union project of 1931 due to intense French pressure, besides discrediting the German Chancellor Heinrich Brüning

Carr's last book, 1982's The Twilight of the Comintern, though not officially a part of the History of Soviet Russia series, was regarded by Carr as the completion of the series. In this book, Carr examined the response of the Comintern to fascism in the years 1930–1935. Carr claimed that the failure of the Austrian-German customs union project of 1931 due to intense French pressure, besides discrediting the German Chancellor Heinrich Brüning

, had left Germany open to Western economic domination due to the bank collapse of the Creditanstalt

followed by the rest of the Central European banking system, and thus led to the triumph of National Socialism in 1933. Carr praised the 1932 article written by his friend Isaac Deutscher

condemning the Third Period

of the Comintern and calling for a united front of socialists and Communists against fascism as an excellent analysis, which had it been followed might have spared the world Nazi Germany. In this same way, Carr praised the examination of fascism offered by Trotsky as being very astute and penetrating. Carr argued that Trotsky was correct in condemning the Comintern's social fascism

theory as doing more harm than good for the cause of the left, and contended that though the SPD

was basically a "bourgeois" party, it was not a fascist party as the Comintern claimed Carr maintained that the Comintern was divided into two fractions in the early 1930s. One fraction headed by the Hungarian Communist Béla Kun

preferred the Third Period policy of treating the non-communist left as "disguised fascists", whereas another fraction headed by the Bulgarian Communist Georgi Dimitrov

supported a policy of building popular fronts with socialists and liberals against fascism. Carr argued that the adoption of the Popular Front

policy in 1935 had been forced on Stalin by pressure from Communist parties abroad, especially the French Communist Party

Carr contended that the 7th Congress of the Comintern in 1935 was essentially the end of the Comintern since it marked the abandonment of world revolution as a goal, and instead subordinated the cause of Communism and world revolution towards the goal of building popular fronts against fascism Another related book that Carr was unable to complete before his death, and was published posthumously by Tamara Deutscher in 1984, was The Comintern and the Spanish Civil War.

The History of Soviet Russia volumes met with a mixed reception. The Encyclopaedia Britannia in 1970 described the History of Soviet Russia series as simply "magisterial". The British historian Chimen Abramsky

praised Carr as the world's foremost historian of the Soviet Union who displayed an astonishing knowledge of the subject. In a 1960 review of Socialism in One Country, the Anglo-Austrian Marxist scholar Rudolf Schlesinger praised Carr for his comprehensive treatment of Soviet history, writing that no other historian had ever covered Soviet history in such detail. The Canadian historian John Keep called the series "A towering scholarly monument; in its shadow the rest of us are but pygmies." Deutscher called A History of Soviet Russia "...a truly outstanding achievement". The left-wing British historian A. J. P. Taylor

called A History of Soviet Russia the most fair and best series of books ever written on Soviet history. Taylor was later to call Carr "an Olympian among historians, a Goethe in range and spirit". The American journalist Harrison Salisbury

called Carr "one of the half dozen greatest specialists in Soviet affairs and in Soviet-German relations". The British academic Michael Cox

praised the History of Soviet Russia series as "...an amazing construction: almost pyramid-like...in its architectural audacity" The British historian John Barber argued that History of Soviet Russia series through a scrupulous and detailed survey of the evidence "transformed" the study of Soviet history in the West. The British historian Hugh Seton-Watson

called Carr "an object of admiration and gratitude" for his work in Soviet studies The South African born British Marxist historian Hillel Ticktin praised Carr as an honest historian of the Soviet Union and accused all of his critics such as Norman Stone

, Richard Pipes

, and Leopold Labedz

of being "Cold War" historians who betoken to McCarthyism criticized Carr for being "for being on the side of the people". Ticktin went to label Carr's critics "...an entirely unsavory collection, not unconnected with serving the needs of official British and American foreign policy" who were "...closely identified with a discredited right-wing politics...". Ticktin described historians such as Pipes and Labedz as being "...never intellectuals but bureaucrats of knowledge, if not worse". Ticktin went to call all historians who were critical of the Soviet Union either rabidly right-wing "Cold Warriors" such as Richard Pipes

and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn

or "CIA intellectuals", and called Carr an "icon of the Left" who sought to honestly portray Soviet history. In 1983, four American historians, namely Geoff Eley

, W. Rosenberg, Moshe Lewin

and Ronald Suny

in a joint article in the London Review of Books wrote of the "grandeur" of Carr's work and his "extraordinary pioneering quality". The four went on to write:

wrote that the "…History of Soviet Russia constitutes, with Joseph Needham's Science and Civilisation in China, the most remarkable effort of single-handed historical scholarship undertaken in Britain within living memory". The American historian Peter Wiles called the History of Soviet Russia "one of the great historiographical enterprises of our day" and wrote of Carr's "immensely impressive" work The American Marxist historian Arno J. Mayer

wrote that "...the History of Soviet Russia...established E.H. Carr not only as the towering giant among Western specialists of recent Russian history, but certainly also as the leading British historian of his generation". Most unusually for a book by a Western historian, A History of Soviet Russia met with warily favourable reviews by Soviet historians. Normally, any works by Western historians, no matter how favourable to Communism, met with hostile reviews in the Soviet Union, and there was even a brand of polemical literature by Soviet historians attacking so-called "bourgeois historians" under the xenophobic grounds that only Soviet historians were capable of understanding the Soviet past".

The History of Soviet Russia series were not translated into Russian and published in the Soviet Union until 1990. A Soviet journal commented in 1991 that Carr was "almost unknown to a broad Soviet readership", through all Soviet historians were aware of his work, and most of them had considerable respect for Carr, through they had been unable to say so until Perestroika

. Those Soviet historians who specialized in rebutting the "bourgeois falsifiers" as Western historians were so labelled in the Soviet Union attacked Carr for writing that Soviet countryside was in chaos after 1917, but praised Carr as one of the "few bourgeois authors" who told the "truth" about Soviet economic achievements. Through right up until glasnost

period, Carr was considered a "bourgeois falsifier" in the Soviet Union, Carr was praised as a British historian who taken "certain steps" towards Marxism, and whose History of Soviet Russia was described as "fairly objective" and "one of the most fundamental works in bourgeois Sovietology". In a preface to the Soviet edition of The History of Soviet Russia in 1990, the Soviet historian Albert Nenarokov wrote in his lifetime Carr had been 'automatically been ranked with the falsifiers", but in fact The History of Soviet Russia was a "scrupulous, professionally conscientious work". Nenarokov called Carr a "honest, objective scholar, espousing liberal principles and attempting on the basis of an enormous documentary base to create a satisfactory picture of the epoch he was considering and those involved in it, to assist a sober and realistic perception of the USSR and a better understanding of the great social processes of the twentieth century". However, Nenarokov expressed some concern about Carr's use of Stalinist language such as calling Bukharin part of the "right deviation" in the Party without the use of the quotation marks. Nenarokov took the view that Carr had too narrowly reduced Soviet history after 1924 down to a choice of either Stalin or Trotsky, arguing that Bukharin was a better, more humane alternative to both Stalin and Trotsky.

The pro-Soviet slant in Carr's The History of Soviet Russia attracted some controversy. The American writer Max Eastman

in a 1950 review of the first volume of A History of Soviet Russia called Carr as "a mild-quiet-hearted bourgeois with a vicarious taste for revolutionary violence" In 1951, the Austrian journalist Franz Borkenau

wrote in the Der Monat newspaper:

accused Carr of systemically taking on Lenin's point of view in History of Soviet Russia volumes and of being unwilling to consider other perspectives on Russian history. In 1962 the British historian Hugh Trevor-Roper argued that Carr's identification with the "victors" of history meant that Carr saw Stalin as historically important, and that Carr had neither time nor sympathy for the millions of Stalin's victims. The Anglo-American historian Robert Conquest

argued that Carr took the official reasons for the launching of the First Five Year Plan too seriously, and argued that the "crisis" of the late 1920s was more the result of Soviet misunderstanding of economics than an "objective" economic crisis forced on Stalin. Furthermore, Conquest maintained that Carr's opponents such as Leonard Schapiro

, Adam Ulam

, Bertram Wolfe

, Robert C. Tucker

and Richard Pipes

had a far better understanding of Soviet history than did Carr. The Polish-born American historian Richard Pipes

wrote that the essential questions of Soviet history were: "Who were the Bolsheviks, what did they want, why did some follow them and others resist? What was the intellectual and moral atmosphere in which all these events occurred?", and went on to note that Carr failed to pose these questions, let alone answer them. Pipes was later to compare Carr's single paragraph dismissal in the History of Soviet Russia of the 1921 famine

as unimportant (because there were no sources for the death toll that Carr deemed trustworthy) with Holocaust denial

.

The Polish Kremlinologist Leopold Labedz

The Polish Kremlinologist Leopold Labedz

criticized Carr for taking the claims of the Soviet government too seriously. Labedz wrote that:

Labedz argued that:

argued that Carr was guilty of writing in a bland style meant to hide his pro-Soviet sympathies. Writing of a History of Soviet Russia in 1983, Stone commented that:

The American historian Walter Laqueur

argued that the History of Soviet Russia volumes were a dubious historical source that for the most part excluded mention of the more unpleasant aspects of Soviet life, reflecting Carr's pro-Soviet tendencies. Laqueur commented that Carr called Stalin a ruthless tyrant in his 1979 book The Russian Revolution, and noted that he almost totally refrained from expressing any criticism of Stalin in all 14 volumes of the History of Soviet Russia series. Likewise, Laqueur contended that Carr excelled at irony, and that writing panegyrics to the Soviet Union was not his forte. In Laqueur's opinion, if Carr is to be remembered by future generations, it will be for books like Dostoyevsky, The Romantic Exiles and Bakunin, and his History of Soviet Russia will besmirch the fine reputation created by those books. A major source of criticism of a History of Soviet Russia was Carr's decision to ignore the Russian Civil War

under the grounds it was unimportant, and likewise to his devoting only a few lines to the Kronstadt mutiny

of 1921 since Carr argued it only a minor event. Laqueur commented in his opinion that Carr's ignoring the Russian Civil War while paying an inordinate amount of attention to such subjects as the relations between the Swedish Communist Party and the Soviet Communist Party

and Soviet diplomatic relations with Outer Mongolia

in the 1920s left the History of Soviet Russia very unbalanced.

What Is History? Carr is also famous today for his work of historiography

, What is History?

(1961), a book based upon his series of G. M. Trevelyan

lectures, delivered at the University of Cambridge

between January–March 1961. In this work, Carr argued that he was presenting a middle-of-the-road position between the empirical

view of history and R. G. Collingwood

's idealism