Trinity College, Cambridge

Encyclopedia

Trinity College is a constituent college

of the University of Cambridge

. Trinity has more members than any other college in Cambridge or Oxford

, with around 700 undergraduates, 430 graduates, and over 170 Fellow

s (however, counting only the student body but not Fellows, Trinity has somewhat fewer students than Homerton College

). Trinity considers itself to be "a world-leading academic institution with an outstanding record of education, learning and research".

Like its sister college, Christ Church, Oxford

, it is traditionally considered the most aristocratic

college of its university, and has generally been the college of choice of the Royal Family

. (King Edward VII

, King George VI

, Prince Henry of Gloucester

, Prince William of Gloucester and Edinburgh

and Prince Charles

were all graduates) The Push Guide to Which University (2005) called it "arguably the grandest Cambridge college" and it has been called "the most magnificent collegiate institution in England". Like Christ Church, the college has been associated with Westminster School

since the school's refoundation in 1560 and the Master remains an ex officio member of the school's governing body.

The proportion of state school to private school pupils at Trinity is roughly 2:3. In 2006 it had the lowest state school intake (39%) of any Cambridge college, and on a rolling three-year average Trinity has admitted a smaller proportion of state school pupils (42%) than any other Oxbridge college. Trinity claims that its admissions policy is dictated solely by academic prospects, regardless of prior schooling. It first admitted women graduate students in 1976 and women undergraduates in 1978; and appointed its first female fellow in 1977.

Trinity has an international academic reputation, its members having won 32 (of the 88 Nobel Prizes awarded to members of Cambridge University), four Fields Medal

s and an Abel Prize

in mathematics and two Templeton Prize

s in religion. In 2008 it had the highest proportion of students gaining Firsts of any college.

Trinity has many notable alumni including six British prime ministers

and several heads of other nations, but its most distinguished include Isaac Newton

, Bertrand Russell

, George VI and Ludwig Wittgenstein

.

Amongst its many college societies, Trinity has the oldest mathematical university society in the United Kingdom

, the Trinity Mathematical Society

and its rowing

club the First and Third Trinity Boat Club

gives its name to Trinity's May Ball

, one of the largest of the University.

The first formalised rules of football, known as the Cambridge Rules, were drawn up at Trinity College in 1848 by Cambridge undergraduate representatives of fashionable schools such as Westminster.

The college was founded by Henry VIII

The college was founded by Henry VIII

in 1546, from the merger of two existing colleges: Michaelhouse

(founded by Hervey de Stanton

in 1324), and King’s Hall

(established by Edward II

in 1317 and refounded by Edward III

in 1337). At the time, Henry had been seizing church lands from abbeys and monasteries. The universities of Oxford

and Cambridge

, being both religious institutions and quite rich, expected to be next in line. The king duly passed an Act of Parliament

that allowed him to suppress (and confiscate the property of) any college he wished. The universities used their contacts to plead with his sixth wife, Catherine Parr

. The queen persuaded her husband not to close them down, but to create a new college. The king did not want to use royal funds, so he instead combined two colleges (King’s Hall

and Michaelhouse

) and seven hostels (Physwick (formerly part of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

), Gregory’s, Ovyng’s, Catherine’s, Garratt, Margaret’s, and Tyler’s) to form Trinity.

Contrary to popular belief, the monastic lands supplied by Henry VIII were alone insufficient to ensure Trinity's eventual rise. In terms of architecture and royal association, it was not until the Mastership of Thomas Nevile (1593–1615) that Trinity assumed both its spaciousness and courtly association with the governing class that distinguished it until the Civil War. In its infancy Trinity had owed a great deal to its neighbouring college of St John's

: in the exaggerated words of Roger Ascham Trinity was little more than a colonia deducta. Its first four Masters were educated at St John's, and it took until around 1575 for the two colleges' application numbers to draw even, a position in which they have remained since the Civil War. In terms of wealth, Trinity's current fortunes belie prior fluctuations; Nevile's building campaign drove the college into debt from which it only surfaced in the 1640s, and the mastership of Richard Bentley

(notorious for the construction of a hugely expensive staircase in the Master's Lodge, and Bentley's repeated refusals to step down despite pleas from the Fellowship) adversely affected applications and finances.

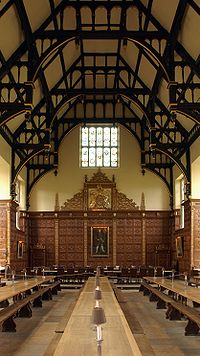

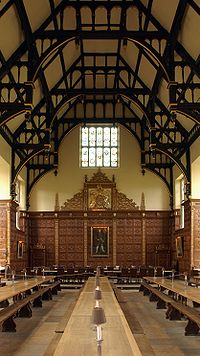

Most of the Trinity’s major buildings date from the 16th and 17th centuries. Thomas Nevile

, who became Master of Trinity in 1593, rebuilt and re-designed much of the college. This work included the enlargement and completion of Great Court

, and the construction of Nevile’s Court

between Great Court and the river Cam

. Nevile’s Court was completed in the late 17th century when the Wren Library

, designed by Sir Christopher Wren, was built.

In the 20th century, Trinity College, St John's College and King’s College

were for decades the main recruiting grounds for the Cambridge Apostles

, an elite, intellectual secret society.

The full name of the college is "The Master, Fellow

s and Scholars of the College

of the Most Holy and Undivided Trinity

in the Town

and University of Cambridge

".

King’s Hostel (1377–1416, various architects): Located to the north of Great Court, behind the Clock Tower, this is (along with the King’s Gate), the sole remaining building from King’s Hall

King’s Hostel (1377–1416, various architects): Located to the north of Great Court, behind the Clock Tower, this is (along with the King’s Gate), the sole remaining building from King’s Hall

.

Great Gate: The Great Gate is the main entrance to the college, leading to the Great Court

. A statue of the college founder, Henry VIII

, stands in a niche above the doorway. In his hand he holds a table leg instead of the original sword and myths abound as to how the switch was carried out and by whom. In 1704, the University’s first astronomical

observatory

was built on top of the gatehouse. Beneath the founder's statue are the coats of arms of Edward III

, the founder of King's Hall, and those of his five sons who survived to maturity, as well as William of Hatfield, whose shield is blank as he died as an infant, before being granted arms.

Great Court

Great Court

(principally 1599-1608, various architects): The brainchild of Thomas Nevile

, who demolished several existing buildings on this site, including almost the entirety of the former college of Michaelhouse

. The sole remaining building of Michaelhouse was replaced by the current Kitchens (designed by James Essex

) in 1770-1775. See 360° panorama of Great Court from the BBC. The Master's Lodge is the official residence of the Sovereign when in Cambridge.

Nevile’s Court

(1614, unknown architect): Located between Great Court and the river, this court was created by a bequest by the college’s master, Thomas Nevile

, originally ⅔ of its current length and without the Wren Library

. The appearance of the upper floor was remodelled slightly two centuries later.

Bishop’s Hostel (1671, Robert Minchin): A detached building to the southwest of Great Court, and named after John Hacket

, Bishop of Lichfield and Coventry. Additional buildings were built in 1878 by Arthur Blomfield.

Wren Library

(1676–1695, Christopher Wren

): Located at the west end of Nevile’s Court, the Wren is one of Cambridge’s most famous and well-endowed libraries. Among its notable possessions are two of Shakespeare’s

First Folios, a 14th-century manuscript of The Vision of Piers Plowman, and letters written by Sir Isaac Newton. Below the building are the pleasant Wren Library Cloisters, where students may enjoy a fine view of the Great Hall in front of them, and the river and Backs

directly behind.

New Court (or King’s Court; 1825, William Wilkins

): Located to the south of Nevile’s Court, and built in Tudor-Gothic style, this court is notable for the large tree in the centre. A myth is sometimes circulated that this was the tree from which the apple dropped onto Isaac Newton

; in fact Newton was at Woolsthorpe when he deduced his theory of gravity. Many other “New Courts” in the colleges were built at this time to accommodate the new influx of students.

Whewell’s Courts (1860 & 1868, Anthony Salvin

): Located across the street from Great Court, these two courts were entirely paid for by William Whewell

, the then master of the college. The north range was later remodelled by W.D. Caroe

. Note: Whewell is pronounced “Hugh-well”.

Angel Court (1957–1959, H. C. Husband): Located between Great Court and Trinity Street

.

Wolfson Building (1968–1972, Architects Co-Partnership): Located to the south of Whewell’s Court, on top of a podium above shops, this building resembles a brick-clad ziggurat, and is used exclusively for first-year accommodation. Having been renovated during the academic year 2005–06, it is once again in use.

Blue Boar Court (1989, MJP Architects and Wright): Located to the south of the Wolfson Building, on top of podium a floor up from ground level, and including the upper floors of several surrounding Georgian buildings on Trinity, Green and Sidney Street

.

Burrell's Field

(1995, MJP Architects): Located on a site to the west of the main College buildings, opposite the Cambridge University Library

.

There are also College rooms above shops in Bridge Street

and Jesus Lane

, behind Whewell’s Court, and graduate accommodation in Portugal Street and other roads around Cambridge.

Fellows’ Garden: Located on the west side of Queen's Road

, opposite the drive that leads to the Backs.

Fellows’ Bowling Green: Located behind the Master’s Lodge

Master’s Garden: Located behind the Master’s Lodge.

Old Fields: Located on the western side of Grange Road

, next to Burrell’s Field, with sports facilities.

The Great Court Run is an attempt to run round the 400-yard perimeter of Great Court

The Great Court Run is an attempt to run round the 400-yard perimeter of Great Court

(approximately 367 m), in the 43 seconds of the clock striking twelve. Students traditionally attempt to complete the circuit on the day of the Matriculation Dinner. It is a rather difficult challenge: one needs to be a fine sprinter to achieve it, but it is by no means necessary to be of Olympic standard, despite assertions made in the press.

It is widely believed that Sebastian Coe successfully completed the run when he beat Steve Cram

in a charity race in October 1988. Sebastian Coe's time on 29 October 1988 was reported by Norris McWhirter

to have been 45.52 seconds, but it was actually 46.0 seconds (confirmed by the video tape), while Cram's was 46.3 seconds. The clock on that day took 44.4 seconds (i.e. a "long" time, probably two days after the last winding) and the video film confirms that Coe was some 12 metres short of his finish line when the fateful final stroke occurred. The television commentators were more than a little disingenuous in suggesting that the dying sounds of the bell could be included in the striking time, thereby allowing Coe's run to be claimed as successful.

One reason Olympic runners Cram and Coe found the challenge so tough is that they started at the middle of one side of the Court, thereby having to negotiate four right-angle turns. In the days when students started at the corner, only three turns were needed.

Until the mid-1990s, the run was traditionally attempted by first year students, at midnight following their Matriculation Dinner. Following a number of accidents to drunk undergraduates running on slippery cobbles, the college now organises a more formal Great Court Run, at 12 noon: the challenge is only open to freshers, many of whom compete in fancy dress.

perform a short concert immediately after the clock strikes noon. Known as Singing from the Towers, half of the choir sings from the top of Great Gate, while the other half sings from the top of the Clock Tower (approximately 60 metres away), giving a strong antiphon

al effect. Midway through the concert, a brass band performs from the top of Queen’s Tower. Later that same day, the College Choir gives a second open-air concert, known as Singing on the River, where they perform madrigal

s (and arrangements of popular songs) from a raft of punts

on the river

. As a 'tradition', however, this latter event dates back only to the mid-1980s, when the College Choir first acquired female members. In the years immediately before this an annual concert on the river was given by the University Chamber Choir.

invisible except in winter, when the leaves had fallen, such bicycles tended to remain for several years before being removed

by the authorities. The students then inserted another bicycle.

Similarly, the sceptre held by the statue of Henry VIII mounted above the medieval Great Gate was replaced with a chair leg as a prank many years ago. It has remained there to this day: when in the 1980s students exchanged the chair leg for a bicycle pump, the College replaced the chair leg.

and John Cockcroft

, of Trinity and St John's respectively.

As with many other Cambridge colleges, the grassed courtyards are generally out of bounds for everyone except the Fellows. Only one of two meadows on "the Backs" (riverside area behind the college) is accessible to students, and other lawns are accessible to graduates in formal gowns.

If both of the two High Tables are in use then the following antiphonal formula is prefixed to the main grace:

Following the meal, the simple formula Benedicto benedicatur is pronounced.

In order of seniority:

Research Scholars receive funding for graduate studies. Typically one must graduate in the top ten percent of one's class and continue for graduate study at Trinity. They are given first preference in the assignment of college rooms and number approximately 25.

The Senior Scholars consist of those who attain a degree with First Class honours

or higher in any year after the first of an undergraduate tripos

, but also, those who obtain an extremely good First in their first year. The college pays them a stipend of £250 a year and also allows them to choose rooms directly following the research scholars. There are around 40 senior scholars at any one time.

The Junior Scholars are precisely those who are not senior scholars but still obtained a First in their first year. Their stipend is £175 a year. They are given preference in the room ballot over 2nd years who are not scholars.

These scholarships are tenable for the academic year following that in which the result was achieved. If a scholarship is awarded but the student does not continue at Trinity then only a quarter of the stipend is given. However all students who achieve a First are awarded an additional £200 prize upon announcement of the results.

All final year undergraduates who achieve first-class honours in their final exams are offered full financial support for proceeding with a Master’s

degree at Cambridge (this funding is also sometimes available for good students who achieved high second-class honours). Other support is available for PhD

degrees. The College also offers a number of other bursaries and studentships open to external applicants. The highly-regarded right to walk on the grass in the college courts is exclusive to Fellows of the college and their guests. Scholars do however have the right to walk on Scholar’s Lawn, but only in full academic dress.

Trinity College has a long-standing relationship with the Parish of St George’s, Camberwell

Trinity College has a long-standing relationship with the Parish of St George’s, Camberwell

, in South London. Students from the College have helped to run holiday schemes for children from the parish since 1966. The relationship was formalized in 1979 with the establishment of Trinity in Camberwell as a registered charity (Charity Commission no. 279447) which exists ‘to provide, promote, assist and encourage the advancement of education and relief of need and other charitable objects for the benefit of the community in the Parish of St George's, Camberwell

, and the neighbourhood thereof.’

, The Prelude (1850), Book Third, describing his view from St John's College, Cambridge

.

, graduate of King's College Cambridge, writes of Maurice Hall's search for homesexual love at Trinity College in his novel, Maurice

(completed 1914, published 1970).

describes her attempt at entry to the Wren, A Room of One's Own

(1929)

Many apocryphal stories have been told about the college's wealth. Trinity is sometimes suggested to be the second, third or fourth wealthiest landowner in the UK (or in England) — after the Crown Estate

Many apocryphal stories have been told about the college's wealth. Trinity is sometimes suggested to be the second, third or fourth wealthiest landowner in the UK (or in England) — after the Crown Estate

, the National Trust

and the Church of England

. (A variant of this legend is repeated in the Tom Sharpe

novel Porterhouse Blue

.) This story is frequently repeated by tour guides. In 2005, Trinity's annual rental income from its properties was reported to be in excess of £20 million.

A second legend is that it is possible to walk from Cambridge to Oxford

on land solely owned by Trinity. Several varieties of this legend exist — others refer to the combined land of Trinity College, Cambridge and Trinity College, Oxford

, of Trinity College, Cambridge and Christ Church, Oxford

, or St John's College, Oxford

and St John's College, Cambridge

. All are most certainly false.

Trinity is often cited as the inventor of an English, less sweet, version of crème brûlée

, known as "Trinity burnt cream", although the college chefs have sometimes been known to refer to it as "Trinity Creme Brulee". The burnt-cream, first introduced at Trinity High Table

in 1879, in fact differs quite markedly from French recipes, the earliest of which is from 1691.

|- style="background:#f7f7f7;"

!Name

!Field

!Year

|-

| Lord Rayleigh

|Physics

|1904

|-

| Sir Joseph John (J. J.) Thomson

|Physics

|1906

|-

|Lord Rutherford

|Chemistry

|1908

|-

|Sir William Bragg

|Physics

|1915

|-

|Sir Lawrence Bragg

|Physics

|1915

|-

|Charles Glover Barkla

|Physics

|1917

|-

|Niels Bohr

|Physics

|1922

|-

|Francis Aston

|Chemistry

|1922

|-

|Archibald V. Hill

|Physiology or Medicine

|1922

|-

|Sir Austen Chamberlain

|Peace

|1925

|-

|Owen Willans Richardson

|Physics

|1928

|-

|Sir Frederick Hopkins

|Physiology or Medicine

|1929

|-

|Edgar Douglas Adrian

|Physiology or Medicine

|1932

|-

|Sir Henry Dale

|Physiology or Medicine

|1936

|-

|George Paget Thomson

|Physics

|1937

|-

|Bertrand Russell

|Literature

|1950

|-

|Ernest Walton

|Physics

|1951

|-

|Richard Synge

|Chemistry

|1952

|-

|Sir John Kendrew

|Chemistry

|1962

|-

|Sir Alan Hodgkin

|Physiology or Medicine

|1963

|-

|Sir Andrew Huxley

|Physiology or Medicine

|1963

|-

|Brian David Josephson

|Physics

|1973

|-

|Sir Martin Ryle

|Physics

|1974

|-

|James Meade

|Economic Sciences

|1977

|-

|Pyotr Kapitsa

|Physics

|1978

|-

|Walter Gilbert

|Chemistry

|1980

|-

|Sir Aaron Klug

|Chemistry

|1982

|-

|Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar

|Physics

|1983

|-

|James Mirrlees

|Economic Sciences

|1996

|-

|John Pople

|Chemistry

|1998

|-

|Amartya Sen

|Economic Sciences

|1998

|-

|Venkatraman Ramakrishnan

|Chemistry

|2009

|}

{|{|border="2" cellpadding="1" cellspacing="0" style="margin: 1em 1em 1em 0; border: 1px #aaa solid; border-collapse: collapse; font-size: 95%;"

{|{|border="2" cellpadding="1" cellspacing="0" style="margin: 1em 1em 1em 0; border: 1px #aaa solid; border-collapse: collapse; font-size: 95%;"

|- style="background:#f7f7f7;"

!Name

!Party

!Year

|-

|Spencer Perceval

|Tory

|1809–1812

|-

|Earl Grey

|Whig

|1830–1834

|-

|Viscount Melbourne

|Whig

|1834–1841

|-

|Arthur Balfour

|Conservative

|1902–1905

|-

|Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman

|Liberal

|1905–1908

|-

|Stanley Baldwin

|Conservative

|1923-1924

1924-1929

1935-1937

|-

|}

Other Trinity politicians include Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

, courtier of Elizabeth I; William Waddington, Prime Minister of France; Erskine Hamilton Childers

, President of Ireland; Jawaharlal Nehru

, the first and longest serving Prime Minister of India

; Rajiv Gandhi

, Prime Minister of India; Lee Hsien Loong

, Prime Minister of Singapore; Samir Rifai

, Prime Minister of Jordan; Stanley Bruce

, the eighth Prime Minister of Australia and The Viscount Whitelaw

, Lady Thatcher's

Home Secretary and subsequent Deputy Prime Minister.

The head of Trinity College is the Master. The first Master was John Redman

The head of Trinity College is the Master. The first Master was John Redman

who was appointed in 1546. The role is a Crown appointment, made by the Monarch on the advice of the Prime Minister. Nowadays the Fellows of the College, and to a lesser extent the Government, choose the new Master and the Royal role is only nominal. In modern times the Master has customarily been of the highest academic distinction.

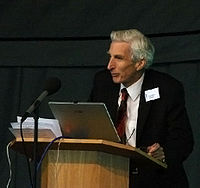

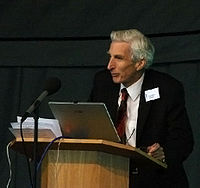

The last three Masters have all been fellows of the college. The current master is The Lord Rees of Ludlow, OM, PRS

.

For a full list, see List of Masters of Trinity College, Cambridge.

college with an independent financial endowment

of approximately £700 million (as of 2010).

Of this amount approx. £75 million is part of the college's Amalgamated Trust Funds, which is dedicated for specific purposes.

Trinity's land, including holdings in the Port of Felixstowe

and the Cambridge Science Park

, is insured for approx. £266.5 million (this does not include all fixed assets).

In 2009, Trinity acquired a stake in The O2 Arena

in London; under the terms of the deal the college receives rental and sales income from the venue.

Colleges of the University of Cambridge

This is a list of the colleges within the University of Cambridge. These colleges are the primary source of accommodation for undergraduates and graduates at the University and at the undergraduate level have responsibility for admitting students and organising their tuition. They also provide...

of the University of Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

. Trinity has more members than any other college in Cambridge or Oxford

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

, with around 700 undergraduates, 430 graduates, and over 170 Fellow

Fellow

A fellow in the broadest sense is someone who is an equal or a comrade. The term fellow is also used to describe a person, particularly by those in the upper social classes. It is most often used in an academic context: a fellow is often part of an elite group of learned people who are awarded...

s (however, counting only the student body but not Fellows, Trinity has somewhat fewer students than Homerton College

Homerton College, Cambridge

Homerton College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in England.With around 1,200 students, Homerton has more students than any other Cambridge college, although less than half of these live in the college. The college has a long and complex history dating back to the...

). Trinity considers itself to be "a world-leading academic institution with an outstanding record of education, learning and research".

Like its sister college, Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church or house of Christ, and thus sometimes known as The House), is one of the largest constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England...

, it is traditionally considered the most aristocratic

Aristocracy (class)

The aristocracy are people considered to be in the highest social class in a society which has or once had a political system of Aristocracy. Aristocrats possess hereditary titles granted by a monarch, which once granted them feudal or legal privileges, or deriving, as in Ancient Greece and India,...

college of its university, and has generally been the college of choice of the Royal Family

British Royal Family

The British Royal Family is the group of close relatives of the monarch of the United Kingdom. The term is also commonly applied to the same group of people as the relations of the monarch in her or his role as sovereign of any of the other Commonwealth realms, thus sometimes at variance with...

. (King Edward VII

Edward VII of the United Kingdom

Edward VII was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions and Emperor of India from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910...

, King George VI

George VI of the United Kingdom

George VI was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death...

, Prince Henry of Gloucester

Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester

The Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester was a soldier and member of the British Royal Family, the third son of George V of the United Kingdom and Queen Mary....

, Prince William of Gloucester and Edinburgh

Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh

Prince William, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh was a member of the British Royal Family, a great-grandson of George II and nephew of George III.-Early life:...

and Prince Charles

Charles, Prince of Wales

Prince Charles, Prince of Wales is the heir apparent and eldest son of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. Since 1958 his major title has been His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales. In Scotland he is additionally known as The Duke of Rothesay...

were all graduates) The Push Guide to Which University (2005) called it "arguably the grandest Cambridge college" and it has been called "the most magnificent collegiate institution in England". Like Christ Church, the college has been associated with Westminster School

Westminster School

The Royal College of St. Peter in Westminster, almost always known as Westminster School, is one of Britain's leading independent schools, with the highest Oxford and Cambridge acceptance rate of any secondary school or college in Britain...

since the school's refoundation in 1560 and the Master remains an ex officio member of the school's governing body.

The proportion of state school to private school pupils at Trinity is roughly 2:3. In 2006 it had the lowest state school intake (39%) of any Cambridge college, and on a rolling three-year average Trinity has admitted a smaller proportion of state school pupils (42%) than any other Oxbridge college. Trinity claims that its admissions policy is dictated solely by academic prospects, regardless of prior schooling. It first admitted women graduate students in 1976 and women undergraduates in 1978; and appointed its first female fellow in 1977.

Trinity has an international academic reputation, its members having won 32 (of the 88 Nobel Prizes awarded to members of Cambridge University), four Fields Medal

Fields Medal

The Fields Medal, officially known as International Medal for Outstanding Discoveries in Mathematics, is a prize awarded to two, three, or four mathematicians not over 40 years of age at each International Congress of the International Mathematical Union , a meeting that takes place every four...

s and an Abel Prize

Abel Prize

The Abel Prize is an international prize presented annually by the King of Norway to one or more outstanding mathematicians. The prize is named after Norwegian mathematician Niels Henrik Abel . It has often been described as the "mathematician's Nobel prize" and is among the most prestigious...

in mathematics and two Templeton Prize

Templeton Prize

The Templeton Prize is an annual award presented by the Templeton Foundation. Established in 1972, it is awarded to a living person who, in the estimation of the judges, "has made an exceptional contribution to affirming life's spiritual dimension, whether through insight, discovery, or practical...

s in religion. In 2008 it had the highest proportion of students gaining Firsts of any college.

Trinity has many notable alumni including six British prime ministers

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

and several heads of other nations, but its most distinguished include Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."...

, Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, OM, FRS was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, and social critic. At various points in his life he considered himself a liberal, a socialist, and a pacifist, but he also admitted that he had never been any of these things...

, George VI and Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Wittgenstein

Ludwig Josef Johann Wittgenstein was an Austrian philosopher who worked primarily in logic, the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. He was professor in philosophy at the University of Cambridge from 1939 until 1947...

.

Amongst its many college societies, Trinity has the oldest mathematical university society in the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, the Trinity Mathematical Society

Trinity Mathematical Society

right|thumb|The [[squared square]] upon which the Trinity Mathematical Society logo is based.The Trinity Mathematical Society, abbreviated TMS, was founded in Trinity College, Cambridge in 1919 by G. H. Hardy to "promote the discussion of subjects of mathematical interest"...

and its rowing

Sport rowing

Rowing is a sport in which athletes race against each other on rivers, on lakes or on the ocean, depending upon the type of race and the discipline. The boats are propelled by the reaction forces on the oar blades as they are pushed against the water...

club the First and Third Trinity Boat Club

First and Third Trinity Boat Club

The First and Third Trinity Boat Club is the rowing club of Trinity College in Cambridge, England. The club formally came into existence in 1946 when the First Trinity Boat Club and the Third Trinity Boat Club merged, although the 2 clubs had been rowing together for several years before that date...

gives its name to Trinity's May Ball

May Ball

A May Ball is a ball at the end of the academic year that happens at any one of the colleges of the University of Cambridge. They are formal affairs, requiring evening dress, with ticket prices of around £65 to £200 , with some colleges selling tickets only in pairs...

, one of the largest of the University.

The first formalised rules of football, known as the Cambridge Rules, were drawn up at Trinity College in 1848 by Cambridge undergraduate representatives of fashionable schools such as Westminster.

History

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

in 1546, from the merger of two existing colleges: Michaelhouse

Michaelhouse, Cambridge

Michaelhouse is the name of one of the former colleges of the University of Cambridge, that existed between 1323 and 1546, when it was merged with King's Hall to form Trinity College. Michaelhouse was the second residential college to be founded, after Peterhouse...

(founded by Hervey de Stanton

Hervey de Stanton

Hervey de Stanton was an English judge and Chancellor of the Exchequer.-Origins and early career:...

in 1324), and King’s Hall

King's Hall, Cambridge

King's Hall was once one of the constituent colleges of Cambridge, founded in 1317, the second after Peterhouse. King's Hall was established by King Edward II to provide chancery clerks for his administration, and was very rich compared to Michaelhouse, which occupied the southern area of what is...

(established by Edward II

Edward II of England

Edward II , called Edward of Caernarfon, was King of England from 1307 until he was deposed by his wife Isabella in January 1327. He was the sixth Plantagenet king, in a line that began with the reign of Henry II...

in 1317 and refounded by Edward III

Edward III of England

Edward III was King of England from 1327 until his death and is noted for his military success. Restoring royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father, Edward II, Edward III went on to transform the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe...

in 1337). At the time, Henry had been seizing church lands from abbeys and monasteries. The universities of Oxford

University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a university located in Oxford, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest surviving university in the world and the oldest in the English-speaking world. Although its exact date of foundation is unclear, there is evidence of teaching as far back as 1096...

and Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

, being both religious institutions and quite rich, expected to be next in line. The king duly passed an Act of Parliament

Act of Parliament

An Act of Parliament is a statute enacted as primary legislation by a national or sub-national parliament. In the Republic of Ireland the term Act of the Oireachtas is used, and in the United States the term Act of Congress is used.In Commonwealth countries, the term is used both in a narrow...

that allowed him to suppress (and confiscate the property of) any college he wished. The universities used their contacts to plead with his sixth wife, Catherine Parr

Catherine Parr

Catherine Parr ; 1512 – 5 September 1548) was Queen consort of England and Ireland and the last of the six wives of King Henry VIII of England. She married Henry VIII on 12 July 1543. She was the fourth commoner Henry had taken as his consort, and outlived him...

. The queen persuaded her husband not to close them down, but to create a new college. The king did not want to use royal funds, so he instead combined two colleges (King’s Hall

King's Hall, Cambridge

King's Hall was once one of the constituent colleges of Cambridge, founded in 1317, the second after Peterhouse. King's Hall was established by King Edward II to provide chancery clerks for his administration, and was very rich compared to Michaelhouse, which occupied the southern area of what is...

and Michaelhouse

Michaelhouse, Cambridge

Michaelhouse is the name of one of the former colleges of the University of Cambridge, that existed between 1323 and 1546, when it was merged with King's Hall to form Trinity College. Michaelhouse was the second residential college to be founded, after Peterhouse...

) and seven hostels (Physwick (formerly part of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

Gonville and Caius College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. The college is often referred to simply as "Caius" , after its second founder, John Keys, who fashionably latinised the spelling of his name after studying in Italy.- Outline :Gonville and...

), Gregory’s, Ovyng’s, Catherine’s, Garratt, Margaret’s, and Tyler’s) to form Trinity.

Contrary to popular belief, the monastic lands supplied by Henry VIII were alone insufficient to ensure Trinity's eventual rise. In terms of architecture and royal association, it was not until the Mastership of Thomas Nevile (1593–1615) that Trinity assumed both its spaciousness and courtly association with the governing class that distinguished it until the Civil War. In its infancy Trinity had owed a great deal to its neighbouring college of St John's

St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college's alumni include nine Nobel Prize winners, six Prime Ministers, three archbishops, at least two princes, and three Saints....

: in the exaggerated words of Roger Ascham Trinity was little more than a colonia deducta. Its first four Masters were educated at St John's, and it took until around 1575 for the two colleges' application numbers to draw even, a position in which they have remained since the Civil War. In terms of wealth, Trinity's current fortunes belie prior fluctuations; Nevile's building campaign drove the college into debt from which it only surfaced in the 1640s, and the mastership of Richard Bentley

Richard Bentley

Richard Bentley was an English classical scholar, critic, and theologian. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge....

(notorious for the construction of a hugely expensive staircase in the Master's Lodge, and Bentley's repeated refusals to step down despite pleas from the Fellowship) adversely affected applications and finances.

Most of the Trinity’s major buildings date from the 16th and 17th centuries. Thomas Nevile

Thomas Nevile

Thomas Nevile was an English clergyman and academic who was Dean of Peterborough and Dean of Canterbury , Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge , and Master of Trinity College, Cambridge ....

, who became Master of Trinity in 1593, rebuilt and re-designed much of the college. This work included the enlargement and completion of Great Court

Trinity Great Court

Great Court is the main court of Trinity College, Cambridge, and reputed to be the largest enclosed court in Europe.The court was completed by Thomas Nevile, master of the college, in the early years of the 17th century, when he rearranged the existing buildings to form a single...

, and the construction of Nevile’s Court

Nevile's Court, Trinity College, Cambridge

Nevile's Court is a court in Trinity College, Cambridge, England, created by a bequest by the college's master, Thomas Nevile.The east side is dominated by the college's Hall, and the north and south sides house college rooms for fellows raised above the cloisters...

between Great Court and the river Cam

River Cam

The River Cam is a tributary of the River Great Ouse in the east of England. The two rivers join to the south of Ely at Pope's Corner. The Great Ouse connects the Cam to England's canal system and to the North Sea at King's Lynn...

. Nevile’s Court was completed in the late 17th century when the Wren Library

Wren Library, Cambridge

The Wren Library is the library of Trinity College in Cambridge. It was designed by Christopher Wren in 1676 and completed in 1695.The library is a single large room built over an open colonnade on the ground floor of Nevile's Court...

, designed by Sir Christopher Wren, was built.

In the 20th century, Trinity College, St John's College and King’s College

King's College, Cambridge

King's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. The college's full name is "The King's College of our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge", but it is usually referred to simply as "King's" within the University....

were for decades the main recruiting grounds for the Cambridge Apostles

Cambridge Apostles

The Cambridge Apostles, also known as the Cambridge Conversazione Society, is an intellectual secret society at the University of Cambridge founded in 1820 by George Tomlinson, a Cambridge student who went on to become the first Bishop of Gibraltar....

, an elite, intellectual secret society.

The full name of the college is "The Master, Fellow

Fellow

A fellow in the broadest sense is someone who is an equal or a comrade. The term fellow is also used to describe a person, particularly by those in the upper social classes. It is most often used in an academic context: a fellow is often part of an elite group of learned people who are awarded...

s and Scholars of the College

College

A college is an educational institution or a constituent part of an educational institution. Usage varies in English-speaking nations...

of the Most Holy and Undivided Trinity

Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity defines God as three divine persons : the Father, the Son , and the Holy Spirit. The three persons are distinct yet coexist in unity, and are co-equal, co-eternal and consubstantial . Put another way, the three persons of the Trinity are of one being...

in the Town

Cambridge

The city of Cambridge is a university town and the administrative centre of the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It lies in East Anglia about north of London. Cambridge is at the heart of the high-technology centre known as Silicon Fen – a play on Silicon Valley and the fens surrounding the...

and University of Cambridge

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a public research university located in Cambridge, United Kingdom. It is the second-oldest university in both the United Kingdom and the English-speaking world , and the seventh-oldest globally...

".

Buildings and grounds

King's Hall, Cambridge

King's Hall was once one of the constituent colleges of Cambridge, founded in 1317, the second after Peterhouse. King's Hall was established by King Edward II to provide chancery clerks for his administration, and was very rich compared to Michaelhouse, which occupied the southern area of what is...

.

Great Gate: The Great Gate is the main entrance to the college, leading to the Great Court

Trinity Great Court

Great Court is the main court of Trinity College, Cambridge, and reputed to be the largest enclosed court in Europe.The court was completed by Thomas Nevile, master of the college, in the early years of the 17th century, when he rearranged the existing buildings to form a single...

. A statue of the college founder, Henry VIII

Henry VIII of England

Henry VIII was King of England from 21 April 1509 until his death. He was Lord, and later King, of Ireland, as well as continuing the nominal claim by the English monarchs to the Kingdom of France...

, stands in a niche above the doorway. In his hand he holds a table leg instead of the original sword and myths abound as to how the switch was carried out and by whom. In 1704, the University’s first astronomical

Astronomy departments in the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge has three large astronomy departments as follows:* The Institute of Astronomy, concentrating on theoretical astronomy and optical, infrared and x-ray observations...

observatory

Observatory

An observatory is a location used for observing terrestrial or celestial events. Astronomy, climatology/meteorology, geology, oceanography and volcanology are examples of disciplines for which observatories have been constructed...

was built on top of the gatehouse. Beneath the founder's statue are the coats of arms of Edward III

Edward III of England

Edward III was King of England from 1327 until his death and is noted for his military success. Restoring royal authority after the disastrous reign of his father, Edward II, Edward III went on to transform the Kingdom of England into one of the most formidable military powers in Europe...

, the founder of King's Hall, and those of his five sons who survived to maturity, as well as William of Hatfield, whose shield is blank as he died as an infant, before being granted arms.

Trinity Great Court

Great Court is the main court of Trinity College, Cambridge, and reputed to be the largest enclosed court in Europe.The court was completed by Thomas Nevile, master of the college, in the early years of the 17th century, when he rearranged the existing buildings to form a single...

(principally 1599-1608, various architects): The brainchild of Thomas Nevile

Thomas Nevile

Thomas Nevile was an English clergyman and academic who was Dean of Peterborough and Dean of Canterbury , Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge , and Master of Trinity College, Cambridge ....

, who demolished several existing buildings on this site, including almost the entirety of the former college of Michaelhouse

Michaelhouse, Cambridge

Michaelhouse is the name of one of the former colleges of the University of Cambridge, that existed between 1323 and 1546, when it was merged with King's Hall to form Trinity College. Michaelhouse was the second residential college to be founded, after Peterhouse...

. The sole remaining building of Michaelhouse was replaced by the current Kitchens (designed by James Essex

James Essex

-Professional life:Essex was the son of a builder who had fitted the sash windows and wainscot in the Senate House , under James Gibbs; and also worked on the hall of Queens' College, Cambridge . He died in February 1749....

) in 1770-1775. See 360° panorama of Great Court from the BBC. The Master's Lodge is the official residence of the Sovereign when in Cambridge.

Nevile’s Court

Nevile's Court, Trinity College, Cambridge

Nevile's Court is a court in Trinity College, Cambridge, England, created by a bequest by the college's master, Thomas Nevile.The east side is dominated by the college's Hall, and the north and south sides house college rooms for fellows raised above the cloisters...

(1614, unknown architect): Located between Great Court and the river, this court was created by a bequest by the college’s master, Thomas Nevile

Thomas Nevile

Thomas Nevile was an English clergyman and academic who was Dean of Peterborough and Dean of Canterbury , Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge , and Master of Trinity College, Cambridge ....

, originally ⅔ of its current length and without the Wren Library

Wren Library, Cambridge

The Wren Library is the library of Trinity College in Cambridge. It was designed by Christopher Wren in 1676 and completed in 1695.The library is a single large room built over an open colonnade on the ground floor of Nevile's Court...

. The appearance of the upper floor was remodelled slightly two centuries later.

Bishop’s Hostel (1671, Robert Minchin): A detached building to the southwest of Great Court, and named after John Hacket

John Hacket

John Hacket was an English churchman, Bishop of Lichfield and Coventry from 1661 until his death.-Life:He was born in London and educated at Westminster and Trinity College, Cambridge. On taking his degree he was elected a fellow of his college, and soon afterwards wrote the comedy, Loiola , which...

, Bishop of Lichfield and Coventry. Additional buildings were built in 1878 by Arthur Blomfield.

Wren Library

Wren Library, Cambridge

The Wren Library is the library of Trinity College in Cambridge. It was designed by Christopher Wren in 1676 and completed in 1695.The library is a single large room built over an open colonnade on the ground floor of Nevile's Court...

(1676–1695, Christopher Wren

Christopher Wren

Sir Christopher Wren FRS is one of the most highly acclaimed English architects in history.He used to be accorded responsibility for rebuilding 51 churches in the City of London after the Great Fire in 1666, including his masterpiece, St. Paul's Cathedral, on Ludgate Hill, completed in 1710...

): Located at the west end of Nevile’s Court, the Wren is one of Cambridge’s most famous and well-endowed libraries. Among its notable possessions are two of Shakespeare’s

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare was an English poet and playwright, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's national poet and the "Bard of Avon"...

First Folios, a 14th-century manuscript of The Vision of Piers Plowman, and letters written by Sir Isaac Newton. Below the building are the pleasant Wren Library Cloisters, where students may enjoy a fine view of the Great Hall in front of them, and the river and Backs

The Backs

The Backs is an area to the east of Queen's Road in the city of Cambridge, England, where several colleges of the University of Cambridge back on to the River Cam, their grounds covering both banks of the river. The name "the Backs" refers to the backs of the colleges...

directly behind.

New Court (or King’s Court; 1825, William Wilkins

William Wilkins (architect)

William Wilkins RA was an English architect, classical scholar and archaeologist. He designed the National Gallery and University College in London, and buildings for several Cambridge colleges.-Life:...

): Located to the south of Nevile’s Court, and built in Tudor-Gothic style, this court is notable for the large tree in the centre. A myth is sometimes circulated that this was the tree from which the apple dropped onto Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."...

; in fact Newton was at Woolsthorpe when he deduced his theory of gravity. Many other “New Courts” in the colleges were built at this time to accommodate the new influx of students.

Whewell’s Courts (1860 & 1868, Anthony Salvin

Anthony Salvin

Anthony Salvin was an English architect. He gained a reputation as an expert on medieval buildings and applied this expertise to his new buildings and his restorations...

): Located across the street from Great Court, these two courts were entirely paid for by William Whewell

William Whewell

William Whewell was an English polymath, scientist, Anglican priest, philosopher, theologian, and historian of science. He was Master of Trinity College, Cambridge.-Life and career:Whewell was born in Lancaster...

, the then master of the college. The north range was later remodelled by W.D. Caroe

W.D. Caroe

William Douglas Caroe was a British architect, particularly of churches. His sons were the architect A.D.R. Caroe, and Sir Olaf Caroe...

. Note: Whewell is pronounced “Hugh-well”.

Angel Court (1957–1959, H. C. Husband): Located between Great Court and Trinity Street

Trinity Street, Cambridge

Trinity Street is a historical street in central Cambridge, England. The street continues north as St John's Street and south as King's Parade and then Trumpington Street....

.

Wolfson Building (1968–1972, Architects Co-Partnership): Located to the south of Whewell’s Court, on top of a podium above shops, this building resembles a brick-clad ziggurat, and is used exclusively for first-year accommodation. Having been renovated during the academic year 2005–06, it is once again in use.

Blue Boar Court (1989, MJP Architects and Wright): Located to the south of the Wolfson Building, on top of podium a floor up from ground level, and including the upper floors of several surrounding Georgian buildings on Trinity, Green and Sidney Street

Sidney Street, Cambridge

Sidney Street is a major street in central Cambridge, England. It runs between Bridge Street at the junction with Jesus Lane to the northwest and St Andrew's Street at the junction with Hobson Street to the southeast....

.

Burrell's Field

Burrell's Field

Burrell's Field provides luxurious student accommodation as part of Trinity College, Cambridge, England. It is located between Queen's Road and Grange Road. It comprises three parts:# Four Edwardian houses, including Whewell House Burrell's Field provides luxurious student accommodation as part of...

(1995, MJP Architects): Located on a site to the west of the main College buildings, opposite the Cambridge University Library

Cambridge University Library

The Cambridge University Library is the centrally-administered library of Cambridge University in England. It comprises five separate libraries:* the University Library main building * the Medical Library...

.

There are also College rooms above shops in Bridge Street

Bridge Street, Cambridge

Bridge Street is a historic street in the north of central Cambridge, England. It runs between Magdalene Street at the junction with Thompson's Lane to the northwest and Sidney Street at the junction with Jesus Lane to the southeast...

and Jesus Lane

Jesus Lane

Jesus Lane is a historical street in central Cambridge, England. The street links with the junction of Bridge Street and Sidney Street to the west. To the east is a roundabout. To the south is King Street, running parallel with Jesus Lane and linking at the roundabout. The road continues east as...

, behind Whewell’s Court, and graduate accommodation in Portugal Street and other roads around Cambridge.

Fellows’ Garden: Located on the west side of Queen's Road

Queen's Road, Cambridge

Queen's Road is a major road to the west of central Cambridge, England. It links with Madingley Road and Northampton Street to the north with Sidgwick Avenue, Newnham Road and Silver Street to the south....

, opposite the drive that leads to the Backs.

Fellows’ Bowling Green: Located behind the Master’s Lodge

Master’s Garden: Located behind the Master’s Lodge.

Old Fields: Located on the western side of Grange Road

Grange Road, Cambridge

Grange Road is a long straight road in western Cambridge, England. It stretches north–south, meeting Madingley Road at a T-junction to the north and Barton Road to the south....

, next to Burrell’s Field, with sports facilities.

The Great Court Run

Trinity Great Court

Great Court is the main court of Trinity College, Cambridge, and reputed to be the largest enclosed court in Europe.The court was completed by Thomas Nevile, master of the college, in the early years of the 17th century, when he rearranged the existing buildings to form a single...

(approximately 367 m), in the 43 seconds of the clock striking twelve. Students traditionally attempt to complete the circuit on the day of the Matriculation Dinner. It is a rather difficult challenge: one needs to be a fine sprinter to achieve it, but it is by no means necessary to be of Olympic standard, despite assertions made in the press.

It is widely believed that Sebastian Coe successfully completed the run when he beat Steve Cram

Steve Cram

Stephen "Steve" Cram MBE is a British retired athlete. Along with fellow Britons Sebastian Coe and Steve Ovett, he was one of the world's dominant middle distance runners during the 1980s. Nicknamed "The Jarrow Arrow", Cram set world records in the 1500 metres, 2000 metres and the mile during a...

in a charity race in October 1988. Sebastian Coe's time on 29 October 1988 was reported by Norris McWhirter

Norris McWhirter

Norris Dewar McWhirter, CBE was a writer, political activist, co-founder of the Freedom Association, and a television presenter. He and his twin brother, Ross, were known internationally for the Guinness Book of Records, a book they wrote and annually updated together between 1955 and 1975...

to have been 45.52 seconds, but it was actually 46.0 seconds (confirmed by the video tape), while Cram's was 46.3 seconds. The clock on that day took 44.4 seconds (i.e. a "long" time, probably two days after the last winding) and the video film confirms that Coe was some 12 metres short of his finish line when the fateful final stroke occurred. The television commentators were more than a little disingenuous in suggesting that the dying sounds of the bell could be included in the striking time, thereby allowing Coe's run to be claimed as successful.

One reason Olympic runners Cram and Coe found the challenge so tough is that they started at the middle of one side of the Court, thereby having to negotiate four right-angle turns. In the days when students started at the corner, only three turns were needed.

Until the mid-1990s, the run was traditionally attempted by first year students, at midnight following their Matriculation Dinner. Following a number of accidents to drunk undergraduates running on slippery cobbles, the college now organises a more formal Great Court Run, at 12 noon: the challenge is only open to freshers, many of whom compete in fancy dress.

Open-Air Concerts

One Sunday each June (the exact date depends on the university term), the College ChoirChoir of Trinity College, Cambridge

The Choir of Trinity College, Cambridge is a mixed choir whose primary function is to sing choral services in the Tudor chapel of Trinity College, Cambridge...

perform a short concert immediately after the clock strikes noon. Known as Singing from the Towers, half of the choir sings from the top of Great Gate, while the other half sings from the top of the Clock Tower (approximately 60 metres away), giving a strong antiphon

Antiphon

An antiphon in Christian music and ritual, is a "responsory" by a choir or congregation, usually in Gregorian chant, to a psalm or other text in a religious service or musical work....

al effect. Midway through the concert, a brass band performs from the top of Queen’s Tower. Later that same day, the College Choir gives a second open-air concert, known as Singing on the River, where they perform madrigal

Madrigal (music)

A madrigal is a secular vocal music composition, usually a partsong, of the Renaissance and early Baroque eras. Traditionally, polyphonic madrigals are unaccompanied; the number of voices varies from two to eight, and most frequently from three to six....

s (and arrangements of popular songs) from a raft of punts

Punt (boat)

A punt is a flat-bottomed boat with a square-cut bow, designed for use in small rivers or other shallow water. Punting refers to boating in a punt. The punter generally propels the punt by pushing against the river bed with a pole...

on the river

River Cam

The River Cam is a tributary of the River Great Ouse in the east of England. The two rivers join to the south of Ely at Pope's Corner. The Great Ouse connects the Cam to England's canal system and to the North Sea at King's Lynn...

. As a 'tradition', however, this latter event dates back only to the mid-1980s, when the College Choir first acquired female members. In the years immediately before this an annual concert on the river was given by the University Chamber Choir.

Mallard

Another tradition relates to a duck known as the Mallard, which should reside in the rafters of the Great Hall. Students occasionally moved the duck from one rafter to another without permission from the college, being photographed with the Mallard as proof. This is considered difficult, access to the Hall outside meal-times is prohibited and the rafters are dangerously high, so it was not attempted for several years. During the Easter term of 2006, the Mallard was knocked off its rafter by one of the pigeons which enter the Hall through the pinnacle windows. It was found intact on the floor, and revealed to not be made out of wood as generally believed. It is currently held by the College and it is unknown whether it will be reinstated.Bicycles and chair legs

For many years it was the custom for students to place a bicycle high in branches of the tree in the centre of New Court. Usuallyinvisible except in winter, when the leaves had fallen, such bicycles tended to remain for several years before being removed

by the authorities. The students then inserted another bicycle.

Similarly, the sceptre held by the statue of Henry VIII mounted above the medieval Great Gate was replaced with a chair leg as a prank many years ago. It has remained there to this day: when in the 1980s students exchanged the chair leg for a bicycle pump, the College replaced the chair leg.

College Rivalry

The college remains a great rival of St John’s which is its main competitor in sports and academia (John’s is situated next to Trinity). This has given rise to a number of anecdotes and myths. It is often cited as the reason why the older courts of Trinity generally have no J staircases, despite including other letters in alphabetical order. A far more likely reason remains the absence of the letter J in the Roman alphabet, and it should be noted that St John’s College's older courts also lack J staircases. There are also two small muzzle-loading cannons on the bowling green pointing in the direction of John’s, though this orientation may be coincidental. Generally the colleges maintain a cordial relationship with one other, and Trinity's benefaction and association with her neighboring colleges has always far outweighed such rivalries; compatriotism led famously to the splitting of the atomic nucleus in 1932 by Ernest WaltonErnest Walton

Ernest Thomas Sinton Walton was an Irish physicist and Nobel laureate for his work with John Cockcroft with "atom-smashing" experiments done at Cambridge University in the early 1930s, and so became the first person in history to artificially split the atom, thus ushering the nuclear age...

and John Cockcroft

John Cockcroft

Sir John Douglas Cockcroft OM KCB CBE FRS was a British physicist. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physics for splitting the atomic nucleus with Ernest Walton, and was instrumental in the development of nuclear power....

, of Trinity and St John's respectively.

Minor traditions

Trinity College undergraduate gowns are dark blue, as opposed to the black favoured by most other Cambridge colleges.As with many other Cambridge colleges, the grassed courtyards are generally out of bounds for everyone except the Fellows. Only one of two meadows on "the Backs" (riverside area behind the college) is accessible to students, and other lawns are accessible to graduates in formal gowns.

College Grace

Each evening before dinner, grace is recited by the senior Fellow presiding. The simple grace is as follows:- Benedic, Domine, nos et dona tua, (Bless us, Lord, and these gifts)

- quae de largitate tua sumus sumpturi, (which, through your generosity, we are about to receive)

- et concede, ut illis salubriter nutriti (and grant that we, wholesomely nourished by them,)

- tibi debitum obsequium praestare valeamus, (may be able to offer you the service we owe)

- per Christum Dominum nostrum. (through Christ our Lord)

If both of the two High Tables are in use then the following antiphonal formula is prefixed to the main grace:

- A. Oculi omnium in te sperant Domine: (The eyes of all are on you, Lord)

- B. Et tu das escam illis in tempore. (and you give them their food, in due time.)

- A. Aperis tu manum tuam, (You open your hand)

- B. Et imples omne animal benedictione. (and bestow upon all living things your blessing.)

Following the meal, the simple formula Benedicto benedicatur is pronounced.

Scholarships and prizes

The Scholars, together with the Master and Fellows, make up the Foundation of the College.In order of seniority:

Research Scholars receive funding for graduate studies. Typically one must graduate in the top ten percent of one's class and continue for graduate study at Trinity. They are given first preference in the assignment of college rooms and number approximately 25.

The Senior Scholars consist of those who attain a degree with First Class honours

British undergraduate degree classification

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading scheme for undergraduate degrees in the United Kingdom...

or higher in any year after the first of an undergraduate tripos

Tripos

The University of Cambridge, England, divides the different kinds of honours bachelor's degree by Tripos , plural Triposes. The word has an obscure etymology, but may be traced to the three-legged stool candidates once used to sit on when taking oral examinations...

, but also, those who obtain an extremely good First in their first year. The college pays them a stipend of £250 a year and also allows them to choose rooms directly following the research scholars. There are around 40 senior scholars at any one time.

The Junior Scholars are precisely those who are not senior scholars but still obtained a First in their first year. Their stipend is £175 a year. They are given preference in the room ballot over 2nd years who are not scholars.

These scholarships are tenable for the academic year following that in which the result was achieved. If a scholarship is awarded but the student does not continue at Trinity then only a quarter of the stipend is given. However all students who achieve a First are awarded an additional £200 prize upon announcement of the results.

All final year undergraduates who achieve first-class honours in their final exams are offered full financial support for proceeding with a Master’s

Master's degree

A master's is an academic degree granted to individuals who have undergone study demonstrating a mastery or high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional practice...

degree at Cambridge (this funding is also sometimes available for good students who achieved high second-class honours). Other support is available for PhD

Doctorate

A doctorate is an academic degree or professional degree that in most countries refers to a class of degrees which qualify the holder to teach in a specific field, A doctorate is an academic degree or professional degree that in most countries refers to a class of degrees which qualify the holder...

degrees. The College also offers a number of other bursaries and studentships open to external applicants. The highly-regarded right to walk on the grass in the college courts is exclusive to Fellows of the college and their guests. Scholars do however have the right to walk on Scholar’s Lawn, but only in full academic dress.

Trinity in Camberwell

Camberwell

Camberwell is a district of south London, England, and forms part of the London Borough of Southwark. It is a built-up inner city district located southeast of Charing Cross. To the west it has a boundary with the London Borough of Lambeth.-Toponymy:...

, in South London. Students from the College have helped to run holiday schemes for children from the parish since 1966. The relationship was formalized in 1979 with the establishment of Trinity in Camberwell as a registered charity (Charity Commission no. 279447) which exists ‘to provide, promote, assist and encourage the advancement of education and relief of need and other charitable objects for the benefit of the community in the Parish of St George's, Camberwell

Camberwell

Camberwell is a district of south London, England, and forms part of the London Borough of Southwark. It is a built-up inner city district located southeast of Charing Cross. To the west it has a boundary with the London Borough of Lambeth.-Toponymy:...

, and the neighbourhood thereof.’

Trinity in Literature

— William Wordsworth

"Near me hung Trinity's loquacious clock,

Who never let the quarters, night or day,

Slip by him unproclaimed, and told the hours

Twice over with a male and female voice.

Her pealing organ was my neighbour too;

And from my pillow, looking forth by light

Of moon or favouring stars, I could behold

The antechapel where the statue stood

Of Newton with his prism and silent face,

The marble index of a mind for ever

Voyaging through strange seas of thought, alone."

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth was a major English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with the 1798 joint publication Lyrical Ballads....

, The Prelude (1850), Book Third, describing his view from St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college's alumni include nine Nobel Prize winners, six Prime Ministers, three archbishops, at least two princes, and three Saints....

.

— E. M. Forster

"One night, just before ten o'clock, he [Maurice] slipped into Trinity and waited in the Great Court until the gates were shut behind him. Looking up, he noticed the night. He was indifferent to beauty as a rule, but "what a show of stars!" he thought. And how the fountain splashed when the chimes died away, and the gates and doors all over Cambridge had been fastened up. Trinity men were around him — all of enormous intellect and culture. Maurice's set had laughed at Trinity, but they could not ignore its disdainful radiance, or deny the superiority it scarcely troubles to affirm. He had come to it without their knowledge, humbly, to ask its help. His witty speech faded in its atmosphere, and his heart beat violently."

E. M. Forster

Edward Morgan Forster OM, CH was an English novelist, short story writer, essayist and librettist. He is known best for his ironic and well-plotted novels examining class difference and hypocrisy in early 20th-century British society...

, graduate of King's College Cambridge, writes of Maurice Hall's search for homesexual love at Trinity College in his novel, Maurice

Maurice (novel)

Maurice is a novel by E. M. Forster. A tale of homosexual love in early 20th century England, it follows Maurice Hall from his schooldays, through university and beyond. It was written from 1913 onwards...

(completed 1914, published 1970).

'[B]ut here I was actually at the door which leads into the library itself. I must have opened it, for instantly there issued, like a guardian angel barring the way with a flutter of black gown instead of white wings, a deprecating, silvery, kindly gentleman, who regretted in a low voice as he waved me back that ladies are only admitted to the library if accompanied by a Fellow of the college or furnished with a letter of introduction.— Virginia Woolf

That a famous library has been cursed by a woman is a matter of complete indifference to a famous library. Venerable and calm, with all its treasures safe locked within its breast, it sleeps complacently and will, so far as I am concerned, so sleep for ever.'

Virginia Woolf

Adeline Virginia Woolf was an English author, essayist, publisher, and writer of short stories, regarded as one of the foremost modernist literary figures of the twentieth century....

describes her attempt at entry to the Wren, A Room of One's Own

A Room of One's Own

A Room of One's Own is an extended essay by Virginia Woolf. First published on 24 October 1929, the essay was based on a series of lectures she delivered at Newnham College and Girton College, two women's colleges at Cambridge University in October 1928...

(1929)

Legends

Crown land

In Commonwealth realms, Crown land is an area belonging to the monarch , the equivalent of an entailed estate that passed with the monarchy and could not be alienated from it....

, the National Trust

National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty

The National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, usually known as the National Trust, is a conservation organisation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland...

and the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

. (A variant of this legend is repeated in the Tom Sharpe

Tom Sharpe

Tom Sharpe is an English satirical author, best known for his Wilt series of novels.Sharpe was born in London and moved to South Africa in 1951, where he worked as a social worker and a teacher, before being deported for sedition in 1961...

novel Porterhouse Blue

Porterhouse Blue

Porterhouse Blue is a novel written by Tom Sharpe, first published in 1974. There was a Channel 4 TV series in 1987 based on the novel, adapted by Malcolm Bradbury...

.) This story is frequently repeated by tour guides. In 2005, Trinity's annual rental income from its properties was reported to be in excess of £20 million.

A second legend is that it is possible to walk from Cambridge to Oxford

Oxford

The city of Oxford is the county town of Oxfordshire, England. The city, made prominent by its medieval university, has a population of just under 165,000, with 153,900 living within the district boundary. It lies about 50 miles north-west of London. The rivers Cherwell and Thames run through...

on land solely owned by Trinity. Several varieties of this legend exist — others refer to the combined land of Trinity College, Cambridge and Trinity College, Oxford

Trinity College, Oxford

The College of the Holy and Undivided Trinity in the University of Oxford, of the foundation of Sir Thomas Pope , or Trinity College for short, is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. It stands on Broad Street, next door to Balliol College and Blackwells bookshop,...

, of Trinity College, Cambridge and Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church or house of Christ, and thus sometimes known as The House), is one of the largest constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England...

, or St John's College, Oxford

St John's College, Oxford

__FORCETOC__St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford, one of the larger Oxford colleges with approximately 390 undergraduates, 200 postgraduates and over 100 academic staff. It was founded by Sir Thomas White, a merchant, in 1555, whose heart is buried in the chapel of...

and St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college's alumni include nine Nobel Prize winners, six Prime Ministers, three archbishops, at least two princes, and three Saints....

. All are most certainly false.

Trinity is often cited as the inventor of an English, less sweet, version of crème brûlée

Crème brûlée

Crème brûlée , also known as burnt cream, crema catalana, or Trinity cream is a dessert consisting of a rich custard base topped with a contrasting layer of hard caramel...

, known as "Trinity burnt cream", although the college chefs have sometimes been known to refer to it as "Trinity Creme Brulee". The burnt-cream, first introduced at Trinity High Table

High Table

At Oxford, Cambridge and Durham colleges — and other, similarly traditional and prestigious UK academic institutions At Oxford, Cambridge and Durham colleges — and other, similarly traditional and prestigious UK academic institutions At Oxford, Cambridge and Durham colleges — and other, similarly...

in 1879, in fact differs quite markedly from French recipes, the earliest of which is from 1691.