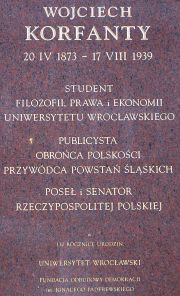

Wojciech Korfanty

Encyclopedia

Wojciech Korfanty born Adalbert Korfanty, was a Polish

nationalist

activist

, journalist

and politician

, serving as member of the German

parliaments Reichstag

and Prussian Landtag, and later on, in the Polish

Sejm

. Briefly, he also was a paramilitary

leader, known for organizing the Polish Silesian Uprisings

in Germany's Upper Silesia

.

He was known for his policies in the wake of World War I

which sought to join Silesia to Poland. He fought to protect Poles from discrimination

and against the policy

of Germanisation

in Upper Silesia before the war. Wojciech was one of the chief advocates of joining Upper Silesia to the new Polish state

after the war.

. From 1895 until 1901, he studied philosophy

, law

, and economics

, first at the Technical University in Charlottenburg (Berlin

) (1895) and at the University of Breslau, where Marxist Werner Sombart

was among his teachers and remained on friendly terms with him for many years.

In 1901, Korfanty became editor-in-chief of the Polish language

In 1901, Korfanty became editor-in-chief of the Polish language

paper

Górnoslązak (The Upper Silesian), in which he appealed to the national consciousness

of the region's Polish-speaking population

.

In 1903, Korfanty was elected

to the German Reichstag

and in 1904 also to the Prussian Landtag, where he represented the independent "Polish circle" (Polskie koło). This was a significant departure from tradition, as the Polish minority in Prussia had so far predominantly supported the Catholic

'Centre Party'

in elections. As the Catholic 'Centre Party' had refused to protect Polish rights

, the Poles distanced themselves from the party, seeking protection elsewhere. In a polemic

paper entitled Precz z Centrum ("Away with the Centre Party", 1901), Korfanty had urged the Catholic Polish-speaking minority

in Germany to overcome their national indifference and shift their political allegiance from supra-national Catholicism to the cause of the Polish nation. However, Korfanty retained his Christian Democratic convictions and later returned to them in domestic Polish politics.

, in 1918, a Kingdom of Poland was proclaimed by Germany, which was replaced by an independent

Polish state. In a Reichstag speech on October 25, 1918, Korfanty demanded that the provinces of West Prussia

(including Ermeland and the city of Danzig (Gdańsk)), the Province of Posen

, and parts of the province

s of East Prussia

(Masuria

) and Silesia

(Upper Silesia) be included in the Polish state.

After the war, during the Great Poland Uprising

, Korfanty became a member of the Naczelna Rada Ludowa (Supreme People's Council) in Poznań

(Posen), and a member of the Polish provisional parliament, the Constituanta-Sejm

. He was also the head of the Polish plebiscite committee

in Upper Silesia. He was one of the leaders of the Second Silesian Uprising in 1920 and the Third Silesian Uprising in 1921 — Polish insurrections, supported and financed by Warsaw, against German rule in Upper Silesia. The German authorities were forced to leave their positions by the League of Nations. Poland was allotted by the League of Nations

roughly half of the population and the most valuable mining districts, which were eventually attached to Poland. Korfanty was accused by Germans of organizing terrorism

against the German civilian

s of Upper Silesia. German propaganda newspapers also "smeared" him with ordering the murder

of Silesian politician Theofil Kupka

.

of the Silesian Voivodship, which he saw as an obstacle against its re-integration into Poland. However, Mr. Korfanty defended the rights of the German minority in Upper Silesia, because he believed that the prosperity

of minorities enriched the whole society

of a region

.

He briefly acted as vice-premier in the government

of Wincenty Witos

(October–December 1923). From 1924, he resumed with his journalist activities as editor-in-chief of the papers Rzeczpospolita ("The Republic

", not to be confused with the modern paper

of the same name) and Polonia. He opposed the May Coup of Józef Piłsudski and his subsequent establishment of Sanacja

-government from a Christian Democratic position. In 1930, he was arrest

ed and imprison

ed in the Brest-Litovsk fortress, together with other leaders of the Centrolew

, an alliance of left-wing and centrist

parties

in opposition to the ruling government.

, where from he participated in the "center-right" Morges Front group formed by émigrés Ignacy Paderewski and Władysław Sikorski. After the German

invasion

of Czechoslovakia

, Mr. Korfanty moved on to France. He returned to Poland in the April of 1939, after Nazi Germany had cancelled the Polish-German non-aggression pact of 1934, hoping that the renewed threat to Polish independence would help overcome the domestic political cleavage. He was arrested immediately upon arrival. In August, he was released as unfit for prison due to his bad health

, and died

shortly afterwards, two weeks before World War II

began with the German invasion of Poland

. Although his cause of death

remains unclear, it has been claimed that the treatment he received in prison may have caused his health to deteriorate.

as a national hero

due to his fight to protect the Polish population in Upper Silesia from discrimination, and his efforts to join the Polish population in Silesia to Poland. Today, many street

s, places and institution

s are named for him. When Opole Silesia became part of Poland in 1945, the town of Friedland in Oberschlesien

, inside German Upper Silesia

, was renamed Korfantów

in his honour

.

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

nationalist

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

activist

Activism

Activism consists of intentional efforts to bring about social, political, economic, or environmental change. Activism can take a wide range of forms from writing letters to newspapers or politicians, political campaigning, economic activism such as boycotts or preferentially patronizing...

, journalist

Journalist

A journalist collects and distributes news and other information. A journalist's work is referred to as journalism.A reporter is a type of journalist who researchs, writes, and reports on information to be presented in mass media, including print media , electronic media , and digital media A...

and politician

Politician

A politician, political leader, or political figure is an individual who is involved in influencing public policy and decision making...

, serving as member of the German

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

parliaments Reichstag

Reichstag (German Empire)

The Reichstag was the parliament of the North German Confederation , and of the German Reich ....

and Prussian Landtag, and later on, in the Polish

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

Sejm

Sejm

The Sejm is the lower house of the Polish parliament. The Sejm is made up of 460 deputies, or Poseł in Polish . It is elected by universal ballot and is presided over by a speaker called the Marshal of the Sejm ....

. Briefly, he also was a paramilitary

Paramilitary

A paramilitary is a force whose function and organization are similar to those of a professional military, but which is not considered part of a state's formal armed forces....

leader, known for organizing the Polish Silesian Uprisings

Silesian Uprisings

The Silesian Uprisings were a series of three armed uprisings of the Poles and Polish Silesians of Upper Silesia, from 1919–1921, against German rule; the resistance hoped to break away from Germany in order to join the Second Polish Republic, which had been established in the wake of World War I...

in Germany's Upper Silesia

Province of Upper Silesia

The Province of Upper Silesia was a province of the Free State of Prussia created in the aftermath of World War I. It comprised much of the region of Upper Silesia and was eventually divided into two administrative regions , Kattowitz and Oppeln...

.

He was known for his policies in the wake of World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

which sought to join Silesia to Poland. He fought to protect Poles from discrimination

Discrimination

Discrimination is the prejudicial treatment of an individual based on their membership in a certain group or category. It involves the actual behaviors towards groups such as excluding or restricting members of one group from opportunities that are available to another group. The term began to be...

and against the policy

Policy

A policy is typically described as a principle or rule to guide decisions and achieve rational outcome. The term is not normally used to denote what is actually done, this is normally referred to as either procedure or protocol...

of Germanisation

Germanisation

Germanisation is both the spread of the German language, people and culture either by force or assimilation, and the adaptation of a foreign word to the German language in linguistics, much like the Romanisation of many languages which do not use the Latin alphabet...

in Upper Silesia before the war. Wojciech was one of the chief advocates of joining Upper Silesia to the new Polish state

Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, Second Commonwealth of Poland or interwar Poland refers to Poland between the two world wars; a period in Polish history in which Poland was restored as an independent state. Officially known as the Republic of Poland or the Commonwealth of Poland , the Polish state was...

after the war.

Early life

Korfanty was born the son of a coal miner in Sadzawka, part of Siemianowice (at the time Laurahütte), in Prussian Silesia, then German EmpireGerman Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

. From 1895 until 1901, he studied philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

, law

Law

Law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social institutions to govern behavior, wherever possible. It shapes politics, economics and society in numerous ways and serves as a social mediator of relations between people. Contract law regulates everything from buying a bus...

, and economics

Economics

Economics is the social science that analyzes the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. The term economics comes from the Ancient Greek from + , hence "rules of the house"...

, first at the Technical University in Charlottenburg (Berlin

Berlin

Berlin is the capital city of Germany and is one of the 16 states of Germany. With a population of 3.45 million people, Berlin is Germany's largest city. It is the second most populous city proper and the seventh most populous urban area in the European Union...

) (1895) and at the University of Breslau, where Marxist Werner Sombart

Werner Sombart

Werner Sombart was a German economist and sociologist, the head of the “Youngest Historical School” and one of the leading Continental European social scientists during the first quarter of the 20th century....

was among his teachers and remained on friendly terms with him for many years.

Polish language

Polish is a language of the Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages, used throughout Poland and by Polish minorities in other countries...

paper

Newspaper

A newspaper is a scheduled publication containing news of current events, informative articles, diverse features and advertising. It usually is printed on relatively inexpensive, low-grade paper such as newsprint. By 2007, there were 6580 daily newspapers in the world selling 395 million copies a...

Górnoslązak (The Upper Silesian), in which he appealed to the national consciousness

Consciousness

Consciousness is a term that refers to the relationship between the mind and the world with which it interacts. It has been defined as: subjectivity, awareness, the ability to experience or to feel, wakefulness, having a sense of selfhood, and the executive control system of the mind...

of the region's Polish-speaking population

Population

A population is all the organisms that both belong to the same group or species and live in the same geographical area. The area that is used to define a sexual population is such that inter-breeding is possible between any pair within the area and more probable than cross-breeding with individuals...

.

In 1903, Korfanty was elected

Election

An election is a formal decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual to hold public office. Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy operates since the 17th century. Elections may fill offices in the legislature, sometimes in the...

to the German Reichstag

Reichstag (German Empire)

The Reichstag was the parliament of the North German Confederation , and of the German Reich ....

and in 1904 also to the Prussian Landtag, where he represented the independent "Polish circle" (Polskie koło). This was a significant departure from tradition, as the Polish minority in Prussia had so far predominantly supported the Catholic

Catholic

The word catholic comes from the Greek phrase , meaning "on the whole," "according to the whole" or "in general", and is a combination of the Greek words meaning "about" and meaning "whole"...

'Centre Party'

Centre Party (Germany)

The German Centre Party was a Catholic political party in Germany during the Kaiserreich and the Weimar Republic. Formed in 1870, it battled the Kulturkampf which the Prussian government launched to reduce the power of the Catholic Church...

in elections. As the Catholic 'Centre Party' had refused to protect Polish rights

Minority rights

The term Minority Rights embodies two separate concepts: first, normal individual rights as applied to members of racial, ethnic, class, religious, linguistic or sexual minorities, and second, collective rights accorded to minority groups...

, the Poles distanced themselves from the party, seeking protection elsewhere. In a polemic

Polemic

A polemic is a variety of arguments or controversies made against one opinion, doctrine, or person. Other variations of argument are debate and discussion...

paper entitled Precz z Centrum ("Away with the Centre Party", 1901), Korfanty had urged the Catholic Polish-speaking minority

Minority language

A minority language is a language spoken by a minority of the population of a territory. Such people are termed linguistic minorities or language minorities.-International politics:...

in Germany to overcome their national indifference and shift their political allegiance from supra-national Catholicism to the cause of the Polish nation. However, Korfanty retained his Christian Democratic convictions and later returned to them in domestic Polish politics.

Polish restoration

At the end of World War IWorld War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, in 1918, a Kingdom of Poland was proclaimed by Germany, which was replaced by an independent

Independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state in which its residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory....

Polish state. In a Reichstag speech on October 25, 1918, Korfanty demanded that the provinces of West Prussia

West Prussia

West Prussia was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773–1824 and 1878–1919/20 which was created out of the earlier Polish province of Royal Prussia...

(including Ermeland and the city of Danzig (Gdańsk)), the Province of Posen

Province of Posen

The Province of Posen was a province of Prussia from 1848–1918 and as such part of the German Empire from 1871 to 1918. The area was about 29,000 km2....

, and parts of the province

Province

A province is a territorial unit, almost always an administrative division, within a country or state.-Etymology:The English word "province" is attested since about 1330 and derives from the 13th-century Old French "province," which itself comes from the Latin word "provincia," which referred to...

s of East Prussia

East Prussia

East Prussia is the main part of the region of Prussia along the southeastern Baltic Coast from the 13th century to the end of World War II in May 1945. From 1772–1829 and 1878–1945, the Province of East Prussia was part of the German state of Prussia. The capital city was Königsberg.East Prussia...

(Masuria

Masuria

Masuria is an area in northeastern Poland famous for its 2,000 lakes. Geographically, Masuria is part of two adjacent lakeland districts, the Masurian Lake District and the Iława Lake District...

) and Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

(Upper Silesia) be included in the Polish state.

After the war, during the Great Poland Uprising

Greater Poland Uprising (1918–1919)

The Greater Poland Uprising of 1918–1919, or Wielkopolska Uprising of 1918–1919 or Posnanian War was a military insurrection of Poles in the Greater Poland region against Germany...

, Korfanty became a member of the Naczelna Rada Ludowa (Supreme People's Council) in Poznań

Poznan

Poznań is a city on the Warta river in west-central Poland, with a population of 556,022 in June 2009. It is among the oldest cities in Poland, and was one of the most important centres in the early Polish state, whose first rulers were buried at Poznań's cathedral. It is sometimes claimed to be...

(Posen), and a member of the Polish provisional parliament, the Constituanta-Sejm

Sejm

The Sejm is the lower house of the Polish parliament. The Sejm is made up of 460 deputies, or Poseł in Polish . It is elected by universal ballot and is presided over by a speaker called the Marshal of the Sejm ....

. He was also the head of the Polish plebiscite committee

Committee

A committee is a type of small deliberative assembly that is usually intended to remain subordinate to another, larger deliberative assembly—which when organized so that action on committee requires a vote by all its entitled members, is called the "Committee of the Whole"...

in Upper Silesia. He was one of the leaders of the Second Silesian Uprising in 1920 and the Third Silesian Uprising in 1921 — Polish insurrections, supported and financed by Warsaw, against German rule in Upper Silesia. The German authorities were forced to leave their positions by the League of Nations. Poland was allotted by the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

roughly half of the population and the most valuable mining districts, which were eventually attached to Poland. Korfanty was accused by Germans of organizing terrorism

Terrorism

Terrorism is the systematic use of terror, especially as a means of coercion. In the international community, however, terrorism has no universally agreed, legally binding, criminal law definition...

against the German civilian

Civilian

A civilian under international humanitarian law is a person who is not a member of his or her country's armed forces or other militia. Civilians are distinct from combatants. They are afforded a degree of legal protection from the effects of war and military occupation...

s of Upper Silesia. German propaganda newspapers also "smeared" him with ordering the murder

Murder

Murder is the unlawful killing, with malice aforethought, of another human being, and generally this state of mind distinguishes murder from other forms of unlawful homicide...

of Silesian politician Theofil Kupka

Theofil Kupka

Theofil Kupka was a Silesian politician.- Biography :...

.

Republican politics

Korfanty was a member of the national Sejm from 1922 to 1930, and in the Silesian Sejm (1922–1935), where he represented a Christian Democratic view-point. He opposed the autonomyAutonomy

Autonomy is a concept found in moral, political and bioethical philosophy. Within these contexts, it is the capacity of a rational individual to make an informed, un-coerced decision...

of the Silesian Voivodship, which he saw as an obstacle against its re-integration into Poland. However, Mr. Korfanty defended the rights of the German minority in Upper Silesia, because he believed that the prosperity

Prosperity

Prosperity is the state of flourishing, thriving, good fortune and/or successful social status. Prosperity often encompasses wealth but also includes others factors which are independent of wealth to varying degrees, such as happiness and health....

of minorities enriched the whole society

Society

A society, or a human society, is a group of people related to each other through persistent relations, or a large social grouping sharing the same geographical or virtual territory, subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations...

of a region

Region

Region is most commonly found as a term used in terrestrial and astrophysics sciences also an area, notably among the different sub-disciplines of geography, studied by regional geographers. Regions consist of subregions that contain clusters of like areas that are distinctive by their uniformity...

.

He briefly acted as vice-premier in the government

Government

Government refers to the legislators, administrators, and arbitrators in the administrative bureaucracy who control a state at a given time, and to the system of government by which they are organized...

of Wincenty Witos

Wincenty Witos

Wincenty Witos was a prominent member of the Polish People's Party from 1895, and leader of its "Piast" faction from 1913. He was a member of parliament in the Galician Sejm from 1908–1914, and an envoy to Reichsrat in Vienna from 1911 to 1918...

(October–December 1923). From 1924, he resumed with his journalist activities as editor-in-chief of the papers Rzeczpospolita ("The Republic

Rzeczpospolita

Rzeczpospolita is a traditional name of the Polish State, usually referred to as Rzeczpospolita Polska . It comes from the words: "rzecz" and "pospolita" , literally, a "common thing". It comes from latin word "respublica", meaning simply "republic"...

", not to be confused with the modern paper

Rzeczpospolita (newspaper)

Rzeczpospolita is a Polish national daily newspaper, with a circulation around of 160,000. Issued every day except Sunday. Rzeczpospolita was printed in broadsheet format, then switched to compact at October 16, 2007...

of the same name) and Polonia. He opposed the May Coup of Józef Piłsudski and his subsequent establishment of Sanacja

Sanacja

Sanation was a Polish political movement that came to power after Józef Piłsudski's May 1926 Coup d'État. Sanation took its name from his watchword—the moral "sanation" of the Polish body politic...

-government from a Christian Democratic position. In 1930, he was arrest

Arrest

An arrest is the act of depriving a person of his or her liberty usually in relation to the purported investigation and prevention of crime and presenting into the criminal justice system or harm to oneself or others...

ed and imprison

Prison

A prison is a place in which people are physically confined and, usually, deprived of a range of personal freedoms. Imprisonment or incarceration is a legal penalty that may be imposed by the state for the commission of a crime...

ed in the Brest-Litovsk fortress, together with other leaders of the Centrolew

Centrolew

The Centrolew was a coalition of several Polish political parties after the 1928 Sejm elections...

, an alliance of left-wing and centrist

Centrism

In politics, centrism is the ideal or the practice of promoting policies that lie different from the standard political left and political right. Most commonly, this is visualized as part of the one-dimensional political spectrum of left-right politics, with centrism landing in the middle between...

parties

Political party

A political party is a political organization that typically seeks to influence government policy, usually by nominating their own candidates and trying to seat them in political office. Parties participate in electoral campaigns, educational outreach or protest actions...

in opposition to the ruling government.

Exile

In 1935, he was forced to leave Poland and emigrated to CzechoslovakiaCzechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

, where from he participated in the "center-right" Morges Front group formed by émigrés Ignacy Paderewski and Władysław Sikorski. After the German

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

invasion

Fall Grün

Fall Grün was a pre-World War II German plan for an aggressive war against Czechoslovakia. The plan was first drafted late in 1937, then revised as the military situation and requirements changed...

of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

, Mr. Korfanty moved on to France. He returned to Poland in the April of 1939, after Nazi Germany had cancelled the Polish-German non-aggression pact of 1934, hoping that the renewed threat to Polish independence would help overcome the domestic political cleavage. He was arrested immediately upon arrival. In August, he was released as unfit for prison due to his bad health

Health

Health is the level of functional or metabolic efficiency of a living being. In humans, it is the general condition of a person's mind, body and spirit, usually meaning to be free from illness, injury or pain...

, and died

Death

Death is the permanent termination of the biological functions that sustain a living organism. Phenomena which commonly bring about death include old age, predation, malnutrition, disease, and accidents or trauma resulting in terminal injury....

shortly afterwards, two weeks before World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

began with the German invasion of Poland

Invasion of Poland (1939)

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign or 1939 Defensive War in Poland and the Poland Campaign in Germany, was an invasion of Poland by Germany, the Soviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the start of World War II in Europe...

. Although his cause of death

Cause of Death

Cause of Death is a 1990 album by American death metal band Obituary. Cause of Death is considered a classic album in the history of death metal. The artwork was done by artist Michael Whelan...

remains unclear, it has been claimed that the treatment he received in prison may have caused his health to deteriorate.

Ex Post Facto

After 1945, when the Polish communists sought legitimisation as the champions and guarantors of Polish independence, Korfanty was finally rehabilitatedPolitical rehabilitation

Political rehabilitation is the process by which a member of a political organization or government who has fallen into disgrace, is restored to public life. It is usually applied to leaders or other prominent individuals who regain their prominence after a period in which they have no influence or...

as a national hero

Hero

A hero , in Greek mythology and folklore, was originally a demigod, their cult being one of the most distinctive features of ancient Greek religion...

due to his fight to protect the Polish population in Upper Silesia from discrimination, and his efforts to join the Polish population in Silesia to Poland. Today, many street

Street

A street is a paved public thoroughfare in a built environment. It is a public parcel of land adjoining buildings in an urban context, on which people may freely assemble, interact, and move about. A street can be as simple as a level patch of dirt, but is more often paved with a hard, durable...

s, places and institution

Institution

An institution is any structure or mechanism of social order and cooperation governing the behavior of a set of individuals within a given human community...

s are named for him. When Opole Silesia became part of Poland in 1945, the town of Friedland in Oberschlesien

Korfantów

Korfantów is a town in the Opole Voivodeship of Poland. It has a population of approximately 1,860 inhabitants. It is named after Wojciech Korfanty....

, inside German Upper Silesia

Province of Upper Silesia

The Province of Upper Silesia was a province of the Free State of Prussia created in the aftermath of World War I. It comprised much of the region of Upper Silesia and was eventually divided into two administrative regions , Kattowitz and Oppeln...

, was renamed Korfantów

Korfantów

Korfantów is a town in the Opole Voivodeship of Poland. It has a population of approximately 1,860 inhabitants. It is named after Wojciech Korfanty....

in his honour

Honour

Honour or honor is an abstract concept entailing a perceived quality of worthiness and respectability that affects both the social standing and the self-evaluation of an individual or corporate body such as a family, school, regiment or nation...

.

Literature

- Sigmund Karski: Albert (Wojciech) Korfanty. Eine Biographie. Dülmen 1990. ISBN 3-87466-118-0

- Marian Orzechowski: Wojciech Korfanty. Breslau 1975.