Munich Agreement

Encyclopedia

The Munich Pact was an agreement permitting the Nazi German

annexation of Czechoslovakia

's Sudetenland

. The Sudetenland

were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich

, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without the presence of Czechoslovakia

. Today, it is widely regarded as a failed act of appeasement

toward Nazi Germany. The agreement was signed in the early hours of 30 September 1938 (but dated 29 September). The purpose of the conference was to discuss the future of the Sudetenland

in the face of territorial demands made by Adolf Hitler

. The agreement was signed by Nazi Germany

, France

, the United Kingdom

, and Italy. The Sudetenland

was of immense strategic importance to Czechoslovakia

, as most of its border defenses were situated there, and many of its banks were located there as well.

Because the state of Czechoslovakia

was not invited to the conference, Czechs and Slovaks

call the Munich Agreement the Munich Dictate . The phrase Munich Betrayal is also used because the military alliance Czechoslovakia had with France and United Kingdom was not honoured. Today the document is typically referred to simply as the Munich Pact (Mnichovská dohoda).

From 1918 to 1938, after the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, more than 3 million ethnic Germans were living in the Czech part

of the newly created state of Czechoslovakia

.

Sudeten German pro-Nazi leader Konrad Henlein

offered the Sudeten German Party (SdP) as the agent for Hitler's campaign. Henlein met with Hitler in Berlin on March 28, 1938, where he was instructed to raise demands unacceptable to the Czechoslovak government led by president Edvard Beneš

. On April 24, the SdP issued the Carlsbad Decrees, demanding autonomy

for the Sudetenland and the freedom to profess Nazi ideology

. If Henlein's demands were granted, the Sudetenland would then be able to align itself with Nazi Germany.

As the previous appeasement of Hitler had shown, the governments of both France

As the previous appeasement of Hitler had shown, the governments of both France

and the United Kingdom

were set on avoiding war at any cost. The French government did not wish to face Nazi Germany

alone and took its lead from the British government and its Prime Minister

Neville Chamberlain

. Chamberlain believed that Sudeten German grievances were justified and that Hitler's intentions were limited. Both Britain and France, therefore, advised Czechoslovakia to concede to the Nazi demands. Beneš resisted and on May 20 a partial mobilization

was underway in response to possible German invasion. Ten days later, Hitler signed a secret directive for war against Czechoslovakia to begin no later than October 1.

In the meantime, the British government demanded that Beneš request a mediator. Not wishing to sever his government's ties with Western Europe, Beneš reluctantly accepted. The British appointed Lord Runciman

and instructed him to persuade Beneš to agree to a plan acceptable to the Sudeten Germans. On September 2, Beneš submitted the Fourth Plan, granting nearly all the demands of the Munich Agreement. Intent on obstructing conciliation, however, the SdP held demonstrations that provoked police action in Ostrava

on September 7. The Sudeten Germans broke off negotiations on September 13, after violence and disruption ensued. As Czechoslovak troops attempted to restore order, Henlein flew to Germany and on September 15 issued a proclamation demanding the takeover of the Sudetenland by Germany

.

On the same day, Hitler met with Chamberlain and demanded the swift takeover of the Sudetenland by the Third Reich under threat of war. The Czechs, Hitler claimed, were slaughtering the Sudeten Germans. Chamberlain referred the demand to the British and French governments; both accepted. The Czechoslovak government resisted, arguing that Hitler's proposal would ruin the nation's economy and lead ultimately to German control of all of Czechoslovakia. The United Kingdom and France issued an ultimatum, making a French commitment to Czechoslovakia contingent upon acceptance. On September 21, Czechoslovakia capitulated. The next day, however, Hitler added new demands, insisting that the claims of ethnic Germans in Poland and Hungary also be satisfied.

The Czechoslovak capitulation precipitated an outburst of national indignation. In demonstrations and rallies, Czechs and Slovaks called for a strong military government to defend the integrity of the state. A new cabinet, under General Jan Syrový

, was installed and on September 23 a decree of general mobilization was issued. The Czechoslovak army, modern and possessing an excellent system of frontier fortifications

, was prepared to fight. The Soviet Union

announced its willingness to come to Czechoslovakia's assistance. Beneš, however, refused to go to war without the support of the Western powers.

On September 28, Chamberlain appealed to Hitler for a conference. Hitler met the next day, at Munich

, with the chiefs of governments of France, Italy

and the United Kingdom. The Czechoslovak government was neither invited nor consulted.

A deal was reached on 29 September, and at about 1:30am on 30 September 1938, Adolf Hitler

A deal was reached on 29 September, and at about 1:30am on 30 September 1938, Adolf Hitler

, Neville Chamberlain

, Benito Mussolini

and Édouard Daladier

signed the Munich Agreement. The agreement was officially introduced by Mussolini although in fact the so-called Italian plan had been prepared in the German Foreign Office. It was nearly identical to the Godesberg proposal: the German army was to complete the occupation of the Sudetenland by 10 October, and an international commission would decide the future of other disputed areas.

Czechoslovakia was informed by Britain and France that it could either resist Nazi Germany alone or submit to the prescribed annexations. The Czechoslovak government, realizing the hopelessness of fighting the Nazis alone, reluctantly capitulated (30 September) and agreed to abide by the agreement. The settlement gave Germany the Sudetenland starting 10 October, and de facto control over the rest of Czechoslovakia as long as Hitler promised to go no further. On September 30 after some rest, Chamberlain went to Hitler and asked him to sign a peace treaty between the United Kingdom and Germany. After Hitler's interpreter translated it for him, he happily agreed.

On 30 September, upon his return to Britain, Chamberlain delivered his famous "peace for our time" speech to delighted crowds in London.

On 30 September, upon his return to Britain, Chamberlain delivered his famous "peace for our time" speech to delighted crowds in London.

Joseph Stalin was also upset by the results of the Munich conference. The Soviets, who had a mutual military assistance treaty with Czechoslovakia, felt betrayed by France, which also had a mutual military assistance treaty with Czechoslovakia. The British and French, however, mostly used the Soviets as a threat to dangle over the Germans. Stalin concluded that the West had actively colluded with Hitler to hand over a Central European country to the Nazis, causing concern that they might do the same to the Soviet Union in the future, allowing the partition of the USSR between the western powers and the fascist Axis

. This belief led the Soviet Union to reorient its foreign policy towards a rapprochement with Germany, which eventually led to the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

in 1939.

The Czechoslovaks were greatly dismayed with the Munich settlement. With Sudetenland gone to Germany, Czecho-Slovakia (as the state was now renamed) lost its defensible border with Germany and its fortifications

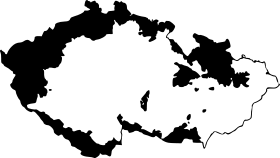

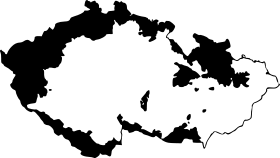

. Without them its independence became more nominal than real. In fact, Edvard Beneš

, the President of Czechoslovakia, had the military print the march orders for his army and put the press on standby for a declaration of war. Czechoslovakia also lost 70% of its iron/steel, 70% of its electrical power, 3.5 million citizens to Germany as a result of the settlement.

The Sudeten Germans celebrated what they saw as their liberation. The imminent war, it seemed, had been avoided.

In Germany, the decision preempted a potential revolt by senior Army officers against Hitler. Hitler's determination to go through with his plan for the invasion of all Czechoslovakia in 1938 had provoked a major crisis in the German command structure. The Chief of the General Staff, General Ludwig Beck

, protested in a lengthy series of memos that it would start a world war that Germany would lose, and urged Hitler to put off the projected war. Hitler called Beck's arguments against war "kindische Kräfteberechnungen" ("childish force calculations"). On August 4, 1938, a secret Army meeting was held. Beck read his lengthy report to the assembled officers. They all agreed something had to be done to prevent certain disaster. Beck hoped they would all resign together but no one resigned except Beck. However his replacement, General Franz Halder

, sympathised with Beck and together they conspired with several top generals, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris

(Chief of German Intelligence), and Graf von Helldorf

(Berlin's Police Chief) to arrest Hitler the moment he gave the invasion order. However, the plan would only work if both Britain and France made it known to the world that they would fight to preserve Czechoslovakia. This would help to convince the German people that certain defeat awaited Germany. Agents were therefore sent to England to tell Chamberlain that an attack on Czechoslovakia was planned and their intentions to overthrow Hitler if this occurred. However, the messengers were not taken seriously by the British. In September, Chamberlain and Daladier decided not to threaten a war over Czechoslovakia and so the planned removal of Hitler could not be justified. The Munich Agreement therefore preserved Hitler in power.

before he had presented the agreement to Parliament

. But there was opposition from the start; Clement Attlee

and the Labour Party opposed the agreement, in alliance with two Conservative MPs, Duff Cooper

and Vyvyan Adams

who had been seen, up to then as a die hard and reactionary

element in the Conservative Party.

In later years Chamberlain was excoriated for his role as one of the Men of Munich - perhaps most famously in the 1940 book Guilty Men

. A rare wartime defence of the Munich Agreement came in 1944 from Viscount Maugham

, who had been Lord Chancellor at the time. Maugham viewed the decision to establish a Czechoslovak state including substantial German and Hungarian minorities as a "dangerous experiment" in the light of previous disputes, and ascribed the Munich Agreement largely to France's need to extricate itself from its treaty obligations in the light of its unpreparedness for war.

Daladier

believed he saw Hitler's ultimate goals, but as a threat. He told the British in a late April 1938 meeting that Hitler's real aim was to eventually secure "a domination of the Continent in comparison with which the ambitions of Napoleon were feeble." He went on to say "Today it is the turn of Czechoslovakia. Tomorrow it will be the turn of Poland

and Romania

. When Germany has obtained the oil and wheat it needs, she will turn on the West. Certainly we must multiply our efforts to avoid war. But that will not be obtained unless Great Britain and France stick together, intervening in Prague for new concessions but declaring at the same time that they will safeguard the independence of Czechoslovakia. If, on the contrary, the Western Powers capitulate again they will only precipitate the war they wish to avoid.". Perhaps discouraged by the arguments of the military and civilian members of the French government regarding their unprepared military and weak financial situation, as well as traumatised by France's bloodbath in the First World War that he was personally a witness to, Daladier ultimately let Chamberlain have his way. On his return to Paris, Daladier, who was expecting a hostile crowd, was acclaimed. He then told his aide, Alexis Léger

: "Ah, les cons!" (Ah, the fools!).

In 1960, William Shirer in his classic - The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich

- took the view that although Hitler was not bluffing about his intention to invade, Czechoslovakia would have been able to offer significant resistance. He believed that Britain and France had sufficient air defences to avoid serious bombing of London and Paris and would have been able to pursue a rapid and successful war against Germany. He quotes Churchill as saying the Munich agreement meant that "Britain and France were in a much worse position compared to Hitler's Germany".

. Following the outbreak of World War II

, he would form a Czechoslovak government-in-exile

in London

.

, which was a result of the Munich agreement, Czechoslovakia (and later Slovakia) — after it had failed to reach a compromise with Hungary

and Poland

— was forced by Germany and Italy to cede southern Slovakia

(one third of Slovak territory) to Hungary, while Poland gained small territorial cessions shortly after.

As a result, Bohemia

, Moravia

and Silesia

lost about 38% of their combined area to Germany, with some 3.2 million German and 750,000 Czech

inhabitants. Hungary, in turn, received 11882 km² (4,587.7 sq mi) in southern Slovakia and southern Ruthenia

; according to a 1941 census, about 86.5% of the population in this territory was Hungarian. Meanwhile Poland annexed the town of Český Těšín

with the surrounding area

(some 906 km² (349.8 sq mi), some 250,000 inhabitants, Poles made about 36% of population) and two minor border areas in northern Slovakia, more precisely in the regions Spiš

and Orava

. (226 km² (87.3 sq mi), 4,280 inhabitants, only 0.3% Poles).

Soon after Munich, 115,000 Czechs and 30,000 Germans fled to the remaining rump of Czechoslovakia. According to the Institute for Refugee Assistance, the actual count of refugee

s on March 1, 1939 stood at almost 150,000.

On 4 December 1938, there were elections in Reichsgau Sudetenland, in which 97.32% of the adult population voted for NSDAP. About a half million Sudeten Germans joined the Nazi Party which was 17.34% of the German population in Sudetenland (the average NSDAP participation in Nazi Germany was 7.85%). This means the Sudetenland was the most "pro-Nazi" region in the Third Reich. Because of their knowledge of the Czech language, many Sudeten Germans were employed in the administration of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia as well as in Nazi organizations (Gestapo, etc.). The most notable was Karl Hermann Frank

: the SS and Police general and Secretary of State in the Protectorate.

Germany stated that the incorporation of Austria into the Reich resulted in borders with Czechoslovakia that were a great danger to German security, and that this allowed Germany to be encircled by the Western Powers. In 1937, the Wehrmacht

Germany stated that the incorporation of Austria into the Reich resulted in borders with Czechoslovakia that were a great danger to German security, and that this allowed Germany to be encircled by the Western Powers. In 1937, the Wehrmacht

had formulated a plan called Operation Green (Fall Grün

) for the invasion of Czechoslovakia which was implemented as Operation Southeast on 15 March 1939.

On 14 March Slovakia seceded from Czechoslovakia and became a separate pro-Nazi state

. On the following day, Carpathian Ruthenia proclaimed independence as well, but after three days was completely occupied by Hungary. Czechoslovak president Emil Hácha

traveled to Berlin and was forced to sign his acceptance of German occupation

of the remainder of Bohemia

and Moravia

. Churchill's prediction was fulfilled as German armies entered Prague

and proceeded to occupy the rest of the country, which was transformed into a protectorate of the Reich

.

Meanwhile concerns arose in Great Britain that Poland (now substantially encircled by German possessions) would become the next target of Nazi expansionism, which was made apparent by the dispute over the Polish Corridor

and the Free City of Danzig

. This resulted in the signing of an Anglo-Polish military alliance, and consequent refusal of the Polish government to German negotiation proposals over the Polish Corridor and the status of Danzig.

Prime Minister Chamberlain felt betrayed by the Nazi seizure of Czechoslovakia, realizing his policy of appeasement

towards Hitler had failed, and began to take a much harder line against the Nazis. Among other things he immediately began to mobilize the British Empire's armed forces on a war footing. France did the same. Italy saw itself threatened by the British and French fleets and started its own invasion of Albania

in April 1939. Although no immediate action followed, Hitler's invasion of Poland

on September 1 officially began World War II

.

Non-negligible industrial potential and military equipment of the former Czechoslovakia had been efficiently absorbed in to the Third Reich.

:

To which Masaryk replied as follows:

Following Allied victory and the surrender of the Third Reich in 1945, the Sudetenland was returned to Czechoslovakia, while the German speaking majority was expelled

, sometimes killed.

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

annexation of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

's Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

. The Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

were areas along Czech borders, mainly inhabited by ethnic Germans. The agreement was negotiated at a conference held in Munich

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

, Germany, among the major powers of Europe without the presence of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

. Today, it is widely regarded as a failed act of appeasement

Appeasement

The term appeasement is commonly understood to refer to a diplomatic policy aimed at avoiding war by making concessions to another power. Historian Paul Kennedy defines it as "the policy of settling international quarrels by admitting and satisfying grievances through rational negotiation and...

toward Nazi Germany. The agreement was signed in the early hours of 30 September 1938 (but dated 29 September). The purpose of the conference was to discuss the future of the Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

in the face of territorial demands made by Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

. The agreement was signed by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

, France

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic was the republican government of France from 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed due to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, to 1940, when France was overrun by Nazi Germany during World War II, resulting in the German and Italian occupations of France...

, the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, and Italy. The Sudetenland

Sudetenland

Sudetenland is the German name used in English in the first half of the 20th century for the northern, southwest and western regions of Czechoslovakia inhabited mostly by ethnic Germans, specifically the border areas of Bohemia, Moravia, and those parts of Silesia being within Czechoslovakia.The...

was of immense strategic importance to Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

, as most of its border defenses were situated there, and many of its banks were located there as well.

Because the state of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

was not invited to the conference, Czechs and Slovaks

Slovaks

The Slovaks, Slovak people, or Slovakians are a West Slavic people that primarily inhabit Slovakia and speak the Slovak language, which is closely related to the Czech language.Most Slovaks today live within the borders of the independent Slovakia...

call the Munich Agreement the Munich Dictate . The phrase Munich Betrayal is also used because the military alliance Czechoslovakia had with France and United Kingdom was not honoured. Today the document is typically referred to simply as the Munich Pact (Mnichovská dohoda).

Demands for Sudeten autonomy

From 1918 to 1938, after the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, more than 3 million ethnic Germans were living in the Czech part

Czech lands

Czech lands is an auxiliary term used mainly to describe the combination of Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia. Today, those three historic provinces compose the Czech Republic. The Czech lands had been settled by the Celts , then later by various Germanic tribes until the beginning of 7th...

of the newly created state of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia or Czecho-Slovakia was a sovereign state in Central Europe which existed from October 1918, when it declared its independence from the Austro-Hungarian Empire, until 1992...

.

Sudeten German pro-Nazi leader Konrad Henlein

Konrad Henlein

Konrad Ernst Eduard Henlein was a leading pro-Nazi ethnic German politician in Czechoslovakia and leader of Sudeten German separatists...

offered the Sudeten German Party (SdP) as the agent for Hitler's campaign. Henlein met with Hitler in Berlin on March 28, 1938, where he was instructed to raise demands unacceptable to the Czechoslovak government led by president Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš was a leader of the Czechoslovak independence movement, Minister of Foreign Affairs and the second President of Czechoslovakia. He was known to be a skilled diplomat.- Youth :...

. On April 24, the SdP issued the Carlsbad Decrees, demanding autonomy

Autonomy

Autonomy is a concept found in moral, political and bioethical philosophy. Within these contexts, it is the capacity of a rational individual to make an informed, un-coerced decision...

for the Sudetenland and the freedom to profess Nazi ideology

Nazism

Nazism, the common short form name of National Socialism was the ideology and practice of the Nazi Party and of Nazi Germany...

. If Henlein's demands were granted, the Sudetenland would then be able to align itself with Nazi Germany.

The Pressure on Czechoslovak government

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

were set on avoiding war at any cost. The French government did not wish to face Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

alone and took its lead from the British government and its Prime Minister

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the Head of Her Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. The Prime Minister and Cabinet are collectively accountable for their policies and actions to the Sovereign, to Parliament, to their political party and...

Neville Chamberlain

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain FRS was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. Chamberlain is best known for his appeasement foreign policy, and in particular for his signing of the Munich Agreement in 1938, conceding the...

. Chamberlain believed that Sudeten German grievances were justified and that Hitler's intentions were limited. Both Britain and France, therefore, advised Czechoslovakia to concede to the Nazi demands. Beneš resisted and on May 20 a partial mobilization

Mobilization

Mobilization is the act of assembling and making both troops and supplies ready for war. The word mobilization was first used, in a military context, in order to describe the preparation of the Prussian army during the 1850s and 1860s. Mobilization theories and techniques have continuously changed...

was underway in response to possible German invasion. Ten days later, Hitler signed a secret directive for war against Czechoslovakia to begin no later than October 1.

In the meantime, the British government demanded that Beneš request a mediator. Not wishing to sever his government's ties with Western Europe, Beneš reluctantly accepted. The British appointed Lord Runciman

Walter Runciman, 1st Viscount Runciman of Doxford

Walter Runciman, 1st Viscount Runciman of Doxford PC was a prominent Liberal, later National Liberal politician in the United Kingdom from the 1900s until the 1930s.-Background:...

and instructed him to persuade Beneš to agree to a plan acceptable to the Sudeten Germans. On September 2, Beneš submitted the Fourth Plan, granting nearly all the demands of the Munich Agreement. Intent on obstructing conciliation, however, the SdP held demonstrations that provoked police action in Ostrava

Ostrava

Ostrava is the third largest city in the Czech Republic and the second largest urban agglomeration after Prague. Located close to the Polish border, it is also the administrative center of the Moravian-Silesian Region and of the Municipality with Extended Competence. Ostrava was candidate for the...

on September 7. The Sudeten Germans broke off negotiations on September 13, after violence and disruption ensued. As Czechoslovak troops attempted to restore order, Henlein flew to Germany and on September 15 issued a proclamation demanding the takeover of the Sudetenland by Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

.

On the same day, Hitler met with Chamberlain and demanded the swift takeover of the Sudetenland by the Third Reich under threat of war. The Czechs, Hitler claimed, were slaughtering the Sudeten Germans. Chamberlain referred the demand to the British and French governments; both accepted. The Czechoslovak government resisted, arguing that Hitler's proposal would ruin the nation's economy and lead ultimately to German control of all of Czechoslovakia. The United Kingdom and France issued an ultimatum, making a French commitment to Czechoslovakia contingent upon acceptance. On September 21, Czechoslovakia capitulated. The next day, however, Hitler added new demands, insisting that the claims of ethnic Germans in Poland and Hungary also be satisfied.

The Czechoslovak capitulation precipitated an outburst of national indignation. In demonstrations and rallies, Czechs and Slovaks called for a strong military government to defend the integrity of the state. A new cabinet, under General Jan Syrový

Jan Syrový

Jan Syrový was a Czechoslovak Army four star general and the prime minister during the Munich Crisis.-Early life and military career:...

, was installed and on September 23 a decree of general mobilization was issued. The Czechoslovak army, modern and possessing an excellent system of frontier fortifications

Czechoslovak border fortifications

The Czechoslovak government built a system of border fortifications from 1935 to 1938 as a defensive countermeasure against the rising threat of Nazi Germany that later materialized in the German offensive plan called Fall Grün...

, was prepared to fight. The Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

announced its willingness to come to Czechoslovakia's assistance. Beneš, however, refused to go to war without the support of the Western powers.

On September 28, Chamberlain appealed to Hitler for a conference. Hitler met the next day, at Munich

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

, with the chiefs of governments of France, Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

and the United Kingdom. The Czechoslovak government was neither invited nor consulted.

Resolution

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party , commonly referred to as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state from 1934 to 1945...

, Neville Chamberlain

Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain FRS was a British Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. Chamberlain is best known for his appeasement foreign policy, and in particular for his signing of the Munich Agreement in 1938, conceding the...

, Benito Mussolini

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini was an Italian politician who led the National Fascist Party and is credited with being one of the key figures in the creation of Fascism....

and Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier was a French Radical politician and the Prime Minister of France at the start of the Second World War.-Career:Daladier was born in Carpentras, Vaucluse. Later, he would become known to many as "the bull of Vaucluse" because of his thick neck and large shoulders and determined...

signed the Munich Agreement. The agreement was officially introduced by Mussolini although in fact the so-called Italian plan had been prepared in the German Foreign Office. It was nearly identical to the Godesberg proposal: the German army was to complete the occupation of the Sudetenland by 10 October, and an international commission would decide the future of other disputed areas.

Czechoslovakia was informed by Britain and France that it could either resist Nazi Germany alone or submit to the prescribed annexations. The Czechoslovak government, realizing the hopelessness of fighting the Nazis alone, reluctantly capitulated (30 September) and agreed to abide by the agreement. The settlement gave Germany the Sudetenland starting 10 October, and de facto control over the rest of Czechoslovakia as long as Hitler promised to go no further. On September 30 after some rest, Chamberlain went to Hitler and asked him to sign a peace treaty between the United Kingdom and Germany. After Hitler's interpreter translated it for him, he happily agreed.

Reactions

Though the British and French were pleased, as were the Nazi military and German diplomatic leadership, Hitler was furious. He felt as though he had been forced into acting like a bourgeois politician by his diplomats and generals. He exclaimed furiously soon after the meeting with Chamberlain: "Gentlemen, this has been my first international conference and I can assure you that it will be my last". Hitler now regarded Chamberlain with utter contempt. A British diplomat in Berlin was informed by reliable sources that Hitler viewed Chamberlain as "an impertinent busybody who spoke the ridiculous jargon of an outmoded democracy. The umbrella, which to the ordinary German was the symbol of peace, was in Hitler's view only a subject of derision". Also, Hitler had been heard saying: "If ever that silly old man comes interfering here again with his umbrella, I'll kick him downstairs and jump on his stomach in front of the photographers". In one of his public speeches after Munich, Hitler declared: "Thank God we have no umbrella politicians in this country".Joseph Stalin was also upset by the results of the Munich conference. The Soviets, who had a mutual military assistance treaty with Czechoslovakia, felt betrayed by France, which also had a mutual military assistance treaty with Czechoslovakia. The British and French, however, mostly used the Soviets as a threat to dangle over the Germans. Stalin concluded that the West had actively colluded with Hitler to hand over a Central European country to the Nazis, causing concern that they might do the same to the Soviet Union in the future, allowing the partition of the USSR between the western powers and the fascist Axis

Axis Powers

The Axis powers , also known as the Axis alliance, Axis nations, Axis countries, or just the Axis, was an alignment of great powers during the mid-20th century that fought World War II against the Allies. It began in 1936 with treaties of friendship between Germany and Italy and between Germany and...

. This belief led the Soviet Union to reorient its foreign policy towards a rapprochement with Germany, which eventually led to the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, named after the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov and the German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, was an agreement officially titled the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Soviet Union and signed in Moscow in the late hours of 23 August 1939...

in 1939.

The Czechoslovaks were greatly dismayed with the Munich settlement. With Sudetenland gone to Germany, Czecho-Slovakia (as the state was now renamed) lost its defensible border with Germany and its fortifications

Czechoslovak border fortifications

The Czechoslovak government built a system of border fortifications from 1935 to 1938 as a defensive countermeasure against the rising threat of Nazi Germany that later materialized in the German offensive plan called Fall Grün...

. Without them its independence became more nominal than real. In fact, Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš

Edvard Beneš was a leader of the Czechoslovak independence movement, Minister of Foreign Affairs and the second President of Czechoslovakia. He was known to be a skilled diplomat.- Youth :...

, the President of Czechoslovakia, had the military print the march orders for his army and put the press on standby for a declaration of war. Czechoslovakia also lost 70% of its iron/steel, 70% of its electrical power, 3.5 million citizens to Germany as a result of the settlement.

The Sudeten Germans celebrated what they saw as their liberation. The imminent war, it seemed, had been avoided.

In Germany, the decision preempted a potential revolt by senior Army officers against Hitler. Hitler's determination to go through with his plan for the invasion of all Czechoslovakia in 1938 had provoked a major crisis in the German command structure. The Chief of the General Staff, General Ludwig Beck

Ludwig Beck

Generaloberst Ludwig August Theodor Beck was a German general and Chief of the German General Staff during the early years of the Nazi regime in Germany before World War II....

, protested in a lengthy series of memos that it would start a world war that Germany would lose, and urged Hitler to put off the projected war. Hitler called Beck's arguments against war "kindische Kräfteberechnungen" ("childish force calculations"). On August 4, 1938, a secret Army meeting was held. Beck read his lengthy report to the assembled officers. They all agreed something had to be done to prevent certain disaster. Beck hoped they would all resign together but no one resigned except Beck. However his replacement, General Franz Halder

Franz Halder

Franz Halder was a German General and the head of the Army General Staff from 1938 until September, 1942, when he was dismissed after frequent disagreements with Adolf Hitler.-Early life:...

, sympathised with Beck and together they conspired with several top generals, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris

Wilhelm Canaris

Wilhelm Franz Canaris was a German admiral, head of the Abwehr, the German military intelligence service, from 1935 to 1944 and member of the German Resistance.- Early life and World War I :...

(Chief of German Intelligence), and Graf von Helldorf

Wolf-Heinrich Graf von Helldorf

Wolf-Heinrich Graf von Helldorf was a leading figure in the Nazi regime.-Early life:Helldorf was born in Merseburg, a landowner's son, Helldorf served as a lieutenant from 1915 in the First World War, and from 1918 was a member of the Prussian state assembly.-Berlin chief of police:Already by...

(Berlin's Police Chief) to arrest Hitler the moment he gave the invasion order. However, the plan would only work if both Britain and France made it known to the world that they would fight to preserve Czechoslovakia. This would help to convince the German people that certain defeat awaited Germany. Agents were therefore sent to England to tell Chamberlain that an attack on Czechoslovakia was planned and their intentions to overthrow Hitler if this occurred. However, the messengers were not taken seriously by the British. In September, Chamberlain and Daladier decided not to threaten a war over Czechoslovakia and so the planned removal of Hitler could not be justified. The Munich Agreement therefore preserved Hitler in power.

Opinions about the agreement

The population had expected imminent war and the "statesman-like gesture" of Chamberlain was at first greeted with acclaim. This generally positive reaction, however, quickly soured. Despite royal patronage - Chamberlain was greeted as a hero by the royal family and invited on the balcony at Buckingham PalaceBuckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace, in London, is the principal residence and office of the British monarch. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is a setting for state occasions and royal hospitality...

before he had presented the agreement to Parliament

Parliament

A parliament is a legislature, especially in those countries whose system of government is based on the Westminster system modeled after that of the United Kingdom. The name is derived from the French , the action of parler : a parlement is a discussion. The term came to mean a meeting at which...

. But there was opposition from the start; Clement Attlee

Clement Attlee

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, KG, OM, CH, PC, FRS was a British Labour politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951, and as the Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955...

and the Labour Party opposed the agreement, in alliance with two Conservative MPs, Duff Cooper

Duff Cooper

Alfred Duff Cooper, 1st Viscount Norwich GCMG, DSO, PC , known as Duff Cooper, was a British Conservative Party politician, diplomat and author. He wrote six books, including an autobiography, Old Men Forget, and a biography of Talleyrand...

and Vyvyan Adams

Vyvyan Adams

Vyvyan Adams , full name Samuel Vyvyan Trerice Adams, was a British Conservative Party politician. He was the Member of Parliament for Leeds West from 1931 to 1945, when he was defeated by the swing to Labour. He stood unsuccessfully in the Fulham East constituency in 1947 and 1950...

who had been seen, up to then as a die hard and reactionary

Reactionary

The term reactionary refers to viewpoints that seek to return to a previous state in a society. The term is meant to describe one end of a political spectrum whose opposite pole is "radical". While it has not been generally considered a term of praise it has been adopted as a self-description by...

element in the Conservative Party.

In later years Chamberlain was excoriated for his role as one of the Men of Munich - perhaps most famously in the 1940 book Guilty Men

Guilty Men

Guilty Men was a book published in Great Britain in 1940 that attacked British public figures for their appeasement of Nazi Germany in the 1930s...

. A rare wartime defence of the Munich Agreement came in 1944 from Viscount Maugham

Frederic Maugham, 1st Viscount Maugham

Frederic Herbert Maugham, 1st Viscount Maugham PC, KC was a British lawyer and judge who served as Lord Chancellor from 1938 until 1939 despite having virtually no political career at all....

, who had been Lord Chancellor at the time. Maugham viewed the decision to establish a Czechoslovak state including substantial German and Hungarian minorities as a "dangerous experiment" in the light of previous disputes, and ascribed the Munich Agreement largely to France's need to extricate itself from its treaty obligations in the light of its unpreparedness for war.

Daladier

Édouard Daladier

Édouard Daladier was a French Radical politician and the Prime Minister of France at the start of the Second World War.-Career:Daladier was born in Carpentras, Vaucluse. Later, he would become known to many as "the bull of Vaucluse" because of his thick neck and large shoulders and determined...

believed he saw Hitler's ultimate goals, but as a threat. He told the British in a late April 1938 meeting that Hitler's real aim was to eventually secure "a domination of the Continent in comparison with which the ambitions of Napoleon were feeble." He went on to say "Today it is the turn of Czechoslovakia. Tomorrow it will be the turn of Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

and Romania

Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeastern Europe, on the Lower Danube, within and outside the Carpathian arch, bordering on the Black Sea...

. When Germany has obtained the oil and wheat it needs, she will turn on the West. Certainly we must multiply our efforts to avoid war. But that will not be obtained unless Great Britain and France stick together, intervening in Prague for new concessions but declaring at the same time that they will safeguard the independence of Czechoslovakia. If, on the contrary, the Western Powers capitulate again they will only precipitate the war they wish to avoid.". Perhaps discouraged by the arguments of the military and civilian members of the French government regarding their unprepared military and weak financial situation, as well as traumatised by France's bloodbath in the First World War that he was personally a witness to, Daladier ultimately let Chamberlain have his way. On his return to Paris, Daladier, who was expecting a hostile crowd, was acclaimed. He then told his aide, Alexis Léger

Saint-John Perse

Saint-John Perse was a French poet, awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1960 "for the soaring flight and evocative imagery of his poetry." He was also a major French diplomat from 1914 to 1940, after which he lived primarily in the USA until 1967.-Biography:Alexis Leger was...

: "Ah, les cons!" (Ah, the fools!).

In 1960, William Shirer in his classic - The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich

The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich

The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich is a 1960 non-fiction book by William L. Shirer chronicling the general history of Nazi Germany from 1933 to 1945...

- took the view that although Hitler was not bluffing about his intention to invade, Czechoslovakia would have been able to offer significant resistance. He believed that Britain and France had sufficient air defences to avoid serious bombing of London and Paris and would have been able to pursue a rapid and successful war against Germany. He quotes Churchill as saying the Munich agreement meant that "Britain and France were in a much worse position compared to Hitler's Germany".

Consequences of the Munich agreement

On October 5, Beneš resigned as President of Czechoslovakia, realising that the fall of Czechoslovakia was fait accompliFait Accompli

Fait accompli is a French phrase which means literally "an accomplished deed". It is commonly used to describe an action which is completed before those affected by it are in a position to query or reverse it...

. Following the outbreak of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, he would form a Czechoslovak government-in-exile

Czechoslovak government-in-exile

The Czechoslovak government-in-exile was an informal title conferred upon the Czechoslovak National Liberation Committee, initially by British diplomatic recognition. The name came to be used by other World War II Allies as they subsequently recognized it...

in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

.

The first Vienna Award

In early November 1938, under the first Vienna AwardVienna Awards

The Vienna Awards are two arbitral awards by which arbiters of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy sought to enforce peacefully the claims of Hungary on territory it had lost in 1920 when it signed the Treaty of Trianon...

, which was a result of the Munich agreement, Czechoslovakia (and later Slovakia) — after it had failed to reach a compromise with Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

and Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

— was forced by Germany and Italy to cede southern Slovakia

Slovakia

The Slovak Republic is a landlocked state in Central Europe. It has a population of over five million and an area of about . Slovakia is bordered by the Czech Republic and Austria to the west, Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east and Hungary to the south...

(one third of Slovak territory) to Hungary, while Poland gained small territorial cessions shortly after.

As a result, Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

, Moravia

Moravia

Moravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

and Silesia

Czech Silesia

Czech Silesia is an unofficial name of one of the three Czech lands and a section of the Silesian historical region. It is located in the north-east of the Czech Republic, predominantly in the Moravian-Silesian Region, with a section in the northern Olomouc Region...

lost about 38% of their combined area to Germany, with some 3.2 million German and 750,000 Czech

Czech people

Czechs, or Czech people are a western Slavic people of Central Europe, living predominantly in the Czech Republic. Small populations of Czechs also live in Slovakia, Austria, the United States, the United Kingdom, Chile, Argentina, Canada, Germany, Russia and other countries...

inhabitants. Hungary, in turn, received 11882 km² (4,587.7 sq mi) in southern Slovakia and southern Ruthenia

Ruthenia

Ruthenia is the Latin word used onwards from the 13th century, describing lands of the Ancient Rus in European manuscripts. Its geographic and culturo-ethnic name at that time was applied to the parts of Eastern Europe. Essentially, the word is a false Latin rendering of the ancient place name Rus...

; according to a 1941 census, about 86.5% of the population in this territory was Hungarian. Meanwhile Poland annexed the town of Český Těšín

Ceský Tešín

Český Těšín is a town in the Karviná District, Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. The town is commonly known in the region as just Těšín . It lies on the west bank of the Olza River, in the heart of the historical region of Cieszyn Silesia...

with the surrounding area

Zaolzie

Zaolzie is the Polish name for an area now in the Czech Republic which was disputed between interwar Poland and Czechoslovakia. The name means "lands beyond the Olza River"; it is also called Śląsk zaolziański, meaning "trans-Olza Silesia". Equivalent terms in other languages include Zaolší in...

(some 906 km² (349.8 sq mi), some 250,000 inhabitants, Poles made about 36% of population) and two minor border areas in northern Slovakia, more precisely in the regions Spiš

Spiš

Spiš is a region in north-eastern Slovakia, with a very small area in south-eastern Poland. Spiš is an informal designation of the territory , but it is also the name of one the 21 official tourism regions of Slovakia...

and Orava

Orava (county)

Árva is the Hungarian name of a historic administrative county of the Kingdom of Hungary. Its territory is presently in northern Slovakia and southern Poland...

. (226 km² (87.3 sq mi), 4,280 inhabitants, only 0.3% Poles).

Soon after Munich, 115,000 Czechs and 30,000 Germans fled to the remaining rump of Czechoslovakia. According to the Institute for Refugee Assistance, the actual count of refugee

Refugee

A refugee is a person who outside her country of origin or habitual residence because she has suffered persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or because she is a member of a persecuted 'social group'. Such a person may be referred to as an 'asylum seeker' until...

s on March 1, 1939 stood at almost 150,000.

On 4 December 1938, there were elections in Reichsgau Sudetenland, in which 97.32% of the adult population voted for NSDAP. About a half million Sudeten Germans joined the Nazi Party which was 17.34% of the German population in Sudetenland (the average NSDAP participation in Nazi Germany was 7.85%). This means the Sudetenland was the most "pro-Nazi" region in the Third Reich. Because of their knowledge of the Czech language, many Sudeten Germans were employed in the administration of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia as well as in Nazi organizations (Gestapo, etc.). The most notable was Karl Hermann Frank

Karl Hermann Frank

Karl Hermann Frank was a prominent Sudeten German Nazi official in Czechoslovakia prior to and during World War II and an SS-Obergruppenführer...

: the SS and Police general and Secretary of State in the Protectorate.

Invasion of the remainder of Czechoslovakia

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

had formulated a plan called Operation Green (Fall Grün

Fall Grün

Fall Grün was a pre-World War II German plan for an aggressive war against Czechoslovakia. The plan was first drafted late in 1937, then revised as the military situation and requirements changed...

) for the invasion of Czechoslovakia which was implemented as Operation Southeast on 15 March 1939.

On 14 March Slovakia seceded from Czechoslovakia and became a separate pro-Nazi state

Slovak Republic (1939-1945)

The Slovak Republic , also known as the First Slovak Republic or the Slovak State , was a fascist state which existed from 14 March 1939 to 8 May 1945 as a puppet state of Nazi Germany. It existed on roughly the same territory as present-day Slovakia...

. On the following day, Carpathian Ruthenia proclaimed independence as well, but after three days was completely occupied by Hungary. Czechoslovak president Emil Hácha

Emil Hácha

Emil Hácha was a Czech lawyer, the third President of Czecho-Slovakia from 1938 to 1939. From March 1939, he presided under the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.-Judicial career:...

traveled to Berlin and was forced to sign his acceptance of German occupation

German occupation of Czechoslovakia

German occupation of Czechoslovakia began with the Nazi annexation of Czechoslovakia's northern and western border regions, known collectively as the Sudetenland, under terms outlined by the Munich Agreement. Nazi leader Adolf Hitler's pretext for this effort was the alleged privations suffered by...

of the remainder of Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

and Moravia

Moravia

Moravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

. Churchill's prediction was fulfilled as German armies entered Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

and proceeded to occupy the rest of the country, which was transformed into a protectorate of the Reich

Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was the majority ethnic-Czech protectorate which Nazi Germany established in the central parts of Bohemia, Moravia and Czech Silesia in what is today the Czech Republic...

.

Meanwhile concerns arose in Great Britain that Poland (now substantially encircled by German possessions) would become the next target of Nazi expansionism, which was made apparent by the dispute over the Polish Corridor

Polish Corridor

The Polish Corridor , also known as Danzig Corridor, Corridor to the Sea or Gdańsk Corridor, was a territory located in the region of Pomerelia , which provided the Second Republic of Poland with access to the Baltic Sea, thus dividing the bulk of Germany from the province of East...

and the Free City of Danzig

Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig was a semi-autonomous city-state that existed between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig and surrounding areas....

. This resulted in the signing of an Anglo-Polish military alliance, and consequent refusal of the Polish government to German negotiation proposals over the Polish Corridor and the status of Danzig.

Prime Minister Chamberlain felt betrayed by the Nazi seizure of Czechoslovakia, realizing his policy of appeasement

Appeasement

The term appeasement is commonly understood to refer to a diplomatic policy aimed at avoiding war by making concessions to another power. Historian Paul Kennedy defines it as "the policy of settling international quarrels by admitting and satisfying grievances through rational negotiation and...

towards Hitler had failed, and began to take a much harder line against the Nazis. Among other things he immediately began to mobilize the British Empire's armed forces on a war footing. France did the same. Italy saw itself threatened by the British and French fleets and started its own invasion of Albania

Italian invasion of Albania

The Italian invasion of Albania was a brief military campaign by the Kingdom of Italy against the Albanian Kingdom. The conflict was a result of the imperialist policies of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini...

in April 1939. Although no immediate action followed, Hitler's invasion of Poland

Invasion of Poland (1939)

The Invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign or 1939 Defensive War in Poland and the Poland Campaign in Germany, was an invasion of Poland by Germany, the Soviet Union, and a small Slovak contingent that marked the start of World War II in Europe...

on September 1 officially began World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

.

Non-negligible industrial potential and military equipment of the former Czechoslovakia had been efficiently absorbed in to the Third Reich.

Quotations from key participants

- Neville Chamberlain, announcing the deal at the Heston AerodromeHeston AerodromeHeston Aerodrome was a 1930s airfield located to the west of London, UK, operational between 1929 and 1947. It was situated on the border of the Heston and Cranford areas of Hounslow, Middlesex...

:

- Chamberlain in a letter to his sister Hilda, on 2 October 1938:

- Winston ChurchillWinston ChurchillSir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

, denouncing the Agreement in the House of Commons:

Legal nullification

During the Second World War, British Prime Minister Churchill, who opposed the agreement when it was signed, became determined that the terms of the agreement shall not be upheld after the war, and that the Sudeten territories shall be returned to postwar Czechoslovakia. On August 5, 1942, Foreign Minister Anthony Eden sent the following note to Jan MasarykJan Masaryk

Jan Garrigue Masaryk was a Czech diplomat and politician and Foreign Minister of Czechoslovakia from 1940 to 1948.- Early life :...

:

To which Masaryk replied as follows:

Following Allied victory and the surrender of the Third Reich in 1945, the Sudetenland was returned to Czechoslovakia, while the German speaking majority was expelled

Expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia

The expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia after World War II was part of a series of evacuations and expulsions of Germans from Central and Eastern Europe during and after World War II....

, sometimes killed.

See also

- Appeasement of Hitler

- Neville Chamberlain's European PolicyNeville Chamberlain's European PolicyNeville Chamberlain's European Policy was based on a commitment to "peace for our time."- Commitment to peace :As with many in Europe who had witnessed the horrors of the First World War and its aftermath, Chamberlain was committed to peace...

- German occupation of CzechoslovakiaGerman occupation of CzechoslovakiaGerman occupation of Czechoslovakia began with the Nazi annexation of Czechoslovakia's northern and western border regions, known collectively as the Sudetenland, under terms outlined by the Munich Agreement. Nazi leader Adolf Hitler's pretext for this effort was the alleged privations suffered by...

- Lesson of MunichLesson of MunichIn international relations, the Lesson of Munich asserts that adversaries will interpret restraint as indicating a lack of capability or political will or both. The name refers to the appeasement of Adolf Hitler's Nazi Germany in negotiations toward the eventual Munich Agreement...

- Treaty of Prague (1973)Treaty of Prague (1973)The Treaty of Prague was a treaty signed on 11 December 1973, in Prague, by the Federal Republic of Germany and Czechoslovakia, in which the two States recognized each other diplomatically and declared the 1938 Munich Agreements to be null and void - by acknowledging the inviolability of their...

- Western betrayalWestern betrayalWestern betrayal, also called Yalta betrayal, refers to a range of critical views concerning the foreign policies of several Western countries between approximately 1919 and 1968 regarding Eastern Europe and Central Europe...

External links

- The Munich Agreement - Text of the Munich Agreement on-line

- The Munich Agreement in contemporary radio news broadcasts - Actual radio news broadcasts documenting evolution of the crisis

- The Munich Agreement Original reports from The Times

- British Pathe newsreel (includes Chamberlain's speech at Heston aerodrome) (Adobe FlashAdobe FlashAdobe Flash is a multimedia platform used to add animation, video, and interactivity to web pages. Flash is frequently used for advertisements, games and flash animations for broadcast...

) - Peace: And the Crisis Begins from a broadcast by Dorothy Thompson, October 1, 1938

- Post-blogging the Sudeten Crisis - A day by day summary of the crisis

- Text of the 1942 exchange of notes nullifying the Munich agreement

- Photocopy of The Munich Agreement from Politisches Archiv des Auswärtigen Amts in Berlin (text in German) and from The National Archives in London (map).

- Map of Europe during Munich Agreement at omniatlas