Jerauld Wright

Encyclopedia

Admiral

Jerauld Wright, USN, (June 4, 1898 – April 27, 1995) served as the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Atlantic Command

(CINCLANT) and the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANTFLT), and became the second Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic

(SACLANT) for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), from April 1, 1954 to March 1, 1960, serving longer in these three positions than anyone else in history.

Following World War I

, Wright served as a naval aide for Presidents Calvin Coolidge

and Herbert Hoover

. A recognized authority on naval gunnery, Wright served in the European

and Pacific

theaters during World War II

, developing expertise in amphibious warfare

and coalition warfare planning. After the war, Wright was involved in the evolution of the military structure of NATO as well as overseeing the modernization and readiness of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet during the Cold War

.

Upon his retirement from the U.S. Navy, Wright subsequently served on the Central Intelligence Agency

's National Board of Estimates (NBE) and as the U.S. Ambassador to the Republic of China (Taiwan)

.

Jerauld Wright was born on June 4, 1898, in Amherst, Massachusetts

Jerauld Wright was born on June 4, 1898, in Amherst, Massachusetts

, the second son of Major General

William M. Wright

, United States Army

, (1863–1943) and the former Marjorie R. Jerauld (1867–1954), who also had another son, William Mason Wright, Jr. (1893–1977), and a daughter, Marjorie Wright (1900–1985).

Life for young Jerry Wright was a succession of U.S. Army posts, such as Fort Porter

, Fort Omaha

, the Presidio

, and the Jefferson Barracks, as well as overseas tours of duty in Cuba and the Philippines

. Keeping the family together while his father pursued an active military career was his mother, nicknamed "The Field Marshal" by her husband. Jerry remembered his mother fondly: "She was a tiger with her young."

Jerry's father was a veteran of the Spanish-American War

, the Boxer Rebellion

, and World War I

, during which he commanded the 89th Division in the St. Mihiel offensive

and the Third Corps. He was a recipient of the Distinguished Service Medal

. Following the war, General Wright commanded the Ninth Corps at the Presidio

and the Department of the Philippines

. While his father was assigned to the newly-created U.S. Army General Staff before World War I, Jerry met William Howard Taft

. Later, Jerry accompanied his father on inspection tours of U.S. military installations in the Philippines. During this tour, he was deeply impressed the naval squadron visiting Manila. His growing interest in a naval career was further encouraged by this father, giving his son a very practical perspective:

Prior to going to the U.S. Naval Academy

in Annapolis, Maryland

, Jerry Wright attended the Franciscan Coligio de La Salle in Malate, California, and Shadman's School at Scott's Circle in Washington, DC.

from Congressman

Edward W. Townsend

of the Tenth Congressional District

from the State of New Jersey

. Wright entered the academy on July 31, 1914, the youngest midshipman to enter the academy since the American Civil War

. Wright graduated on June 26, 1917 as part of the Class of 1918, ranked 92nd out of 193, the youngest member in his class.

on August 5, 1917 for anti-submarine patrol and convoy duty, operating as a unit of the Patrol Force through December 21, 1918.

Lt. Wright served on , a , as a watch and division officer from December 1918 to July 1920. Dyer showed the flag in port visits to Gibraltar, La Spezia

Lt. Wright served on , a , as a watch and division officer from December 1918 to July 1920. Dyer showed the flag in port visits to Gibraltar, La Spezia

, Venice

, Trieste

, Spoleto

, Corfu

, and Constantinople

during a nine-month cruise of the Mediterranean

following the signing of the Armistice ending World War I

. Following Dyer's return August 1919, Wright supervised her overhaul at the Brooklyn Navy Yard

. Lt. Wright also briefly commanded the , a , which escorted the presidential yacht , with President

Warren G. Harding

on board, from Gardiner's Bay, New York, to the Capes

. In October 1920, Lt. Wright took command of the , anchored in reserve at Naval Station Newport

, Rhode Island

, for transfer to Charleston, South Carolina

. Later, in February 1922, Lt. Wright joined the , a slated for decommissioning

at the Mare Island Navy Yard, serving as its executive officer

.

In June 1922, Lt. Wright joined the , a , as its executive officer, with additional duties as fire control

officer and navigator

. John D. Ford set sail from the Philadelphia Navy Yard with its sister ships of Squadron 15, Division 3, for the U.S. Asiatic Fleet. The John D. Ford operated throughout the Far East

, including the South China Sea

, the Sea of Japan

, and the Philippines

, showing the flag and training with other destroyers in the fleet.

In July 1926, Lt. Wright joined the , a as the principal assistant of the ship's Gunnery Division. In November 1928, the Maryland took President-elect Herbert Hoover

on the outbound leg of his goodwill tour of Latin America. Wright also further his hands-on education of gunnery and ordnance while serving as a instructor at the Gunnery School on the battleship . Commander Wright joined the , a attached to the Scouting Force

, as its first lieutenant in August 1931 and later became the ship's gunnery officer from June 1932 to June 1934. The Salt Lake City participated in naval exercises in the Atlantic and Pacific, underwent a major overhaul and participated in the 1934 Naval Review.

.jpg) Wright's first sea command was the , a , with Wright serving as its first commanding officer from July 1937 to May 1939. The Blue completed its shakedown cruise

Wright's first sea command was the , a , with Wright serving as its first commanding officer from July 1937 to May 1939. The Blue completed its shakedown cruise

, transitted the Panama Canal

, and joined the Destroyer Division 7 (DesRon 7) as its flagship

, becoming a unit of the Battle Force based at the San Diego Naval Base, California

. The Blue participated in Fleet Problem XX exercises staged in the Caribbean Sea

.

Wright's final pre-war sea assignment was as the executive officer of the , a based at the Pearl Harbor Naval Base

in the Territory of Hawaii

, from March 1941 to May 1942. The Mississippi became a unit of Battleship Division 3 (BatDiv 3) with sister ships and . Following the Bismarck incident and the growing U-boat threat, Battleship Division 3 was secretly shifted to the newly-reconstituted U.S. Atlantic Fleet, under the command of Admiral Ernest J. King, entering the Norfolk Naval Base

in June 1941. Mississippi was present at the Atlantic Conference at Argentia

, participated in the Neutrality Patrol

, and joined the Idaho and the British battleship HMS King George V

to form an Iceland

-based fleet in being to deter the German battleship from deploying into the north Atlantic to threaten Allied convoys. After months of operations in the North Atlantic, Mississippi was en route to Norfolk for long overdue repairs two days after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor

on December 7, 1941.

Lt. Wright served as a naval aide for two Presidents of the United States, including Calvin Coolidge

Lt. Wright served as a naval aide for two Presidents of the United States, including Calvin Coolidge

from September 1924 to June 1926, with additional duties as a watch and division officer on board the presidential yacht , and Herbert Hoover

during his pre-inaugural goodwill tour of Latin America in November 1928. Wright also served as aide to Assistant Secretary of the Navy

Henry L. Roosevelt

from June 1935 to March 1936. Wright subsequently served on board during its commissioning and fitting-out period.

Wright developed an interest in gunnery and ordnance after he was turned down for naval aviation

because he had exophoria

. His first tour of duty at the Bureau of Ordnance

(BuOrd) was as a fire control section assistant, specializing in anti-aircraft equipment, from August 1929 to August 1931. Wright's second BuOrd assignment was with its supply and allowance division, involving ammunition distribution to the fleet, from June 1936 to July 1937. Bureau chief Rear Admiral Harold R. Stark

rated Wright highly.

Commander Wright served two tours at the United States Naval Academy

as the Battalion Commander for the First Battalion, from June 1934 to June 1935, and the Battalion Commander for the Second Battalion, from June 1939 to March 1941. Wright earned two nicknames at the Naval Academy. The first, Old Iron Heels because he wore steel wedges on his shoes to alert midshipmen of his approach. His second nickname, Old Stoneface originated because of his ability to elicit confessions from offending midshipmen regarding disciplinary infractions without uttering a word. Wright also served as the staff aide to the Commander Atlantic Squadron during the Midshipman's Practice Cruise in June–August 1940.

to re-assure its citizens in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor

. In March 1942, Captain Jerauld Wright was detached from the Mississippi for temporary duty on the staff of Admiral Ernest J. King, the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Fleet (COMINCH), before being assigned to Admiral Harold R. Stark's staff in London

, effective June 3, 1942. Captain Wright was subsequently assigned to the planning staff of Lieutenant General

Dwight D. Eisenhower

, who would lead the British-American invasion of North Africa (Operation Torch

). Wright's role would be to coordinate with his British counterparts regarding the Mediterranean landings in Algiers

.

One growing concern for Eisenhower and his planners was the likely reaction of local French political and military leaders toward an Allied invasion of North Africa. Strong French resistance could cause more casualties for the landing force. One issue coloring French attitudes was their deep-seated resentment toward the British for the Attack on Mers-el-Kébir in which the Royal Navy shelled the anchored French fleet in June 1940. Another issue was working with officials connected to the Vichy government which could cause serious political and security complications. Diplomat Robert D. Murphy, the U.S. consul general in Algiers, spearheaded efforts to gather pre-invasion intelligence and cultivate diplomatic contacts in French North Africa, and Wright would find himself intimately involved in his pre-invasion activities.

On October 16, 1942, Captain Jerauld Wright was summoned to Operation Torch's staff headquarters at Horfolk House in London for important meeting with General Eisenhower, alongside other senior officers. Eisenhower informed the group that the War Department

On October 16, 1942, Captain Jerauld Wright was summoned to Operation Torch's staff headquarters at Horfolk House in London for important meeting with General Eisenhower, alongside other senior officers. Eisenhower informed the group that the War Department

had forwarded an urgent cable from U.S. diplomat Robert D. Murphy requesting the immediate dispatch of a top-secret high-level group to meet with Général Charles E. Mast, the military commander of Algiers and the leader of a group of pro-Allied officials in French North Africa.

The objective of this secret mission, code-named Operation Flagpole

, was to reach an agreement through Mast and his colleagues to have Général Henri Giraud

, a key pro-Allied French army officer, step forward, take command of French military forces in North Africa, and then arrange a ceasefire with the Allied invasion force. Other alternatives, like Jean Darlan and Charles de Gaulle

, had been rejected by the British and American governments for a variety of political reasons. Clark would be Eisenhower's personal representative, with Lemnitzer as the top invasion planner, Hamblen as the invasion's logistics expert, and Holmes serving as translator. Wright would serve as the liaison with the French Navy

, with the specific objective of convincing the French to have their fleet anchored in Toulon

join the Allied cause.

The group flew in two Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses bombers to Gibraltar, and on October 19, they boarded the British submarine , Lieutenant

Norman Limbury Auchinleck "Bill" Jewell, RN

, commanding. Seraph then transported Clark's party to the small fishing village of Cherchell

, located 82 mils (132 kilometers) west of Algiers. After midnight on the evening of October 21, the Seraph surfaced and set Clark's mission ashore, where they met with Mast and Murphy. Wright met with Capitaine de vaisseau

Jean Barjot and learned that the French Navy was opposed to U.S. entry into North Africa, although the army

and air force

supported it.

On October 24, Clark's mission returned to the Seraph and later met a seaplane that flew them back to Gibraltar, arriving back in London on October 25 where Wright briefed Admiral Stark. Both Eisenhower and Clark recommended Jerauld Wright for a Distinguished Service Medal

in recognition for his role in Operation Flagpole. Wright's DSM was personally pinned by Admiral Ernest J. King, the Chief of Naval Operations

, during the Casablanca Conference.

With the preliminaries concluded during Operation Flagpole, the next task was to free Général Giraud (code-named Kingpin) whom the Vichy government had under house arrest for his anti-Nazi leanings at Toulon

in southern France. On October 26, 1942, Captain Jerauld Wright was directed to take part in the mission to extract Giraud, code-named Operation Kingpin. Because of intense anti-British sentiment among French officers, the mission would present an American face. However, because there were no American submarines operating in the Mediterranean Sea, a novel solution was conceived with Wright taking command of the British submarine Seraph

. As Captain

G. B. H. Fawkes, RN

, the commander of 8th Submarine Flotilla in the Mediterranean, noted:

The Seraph got underway on October 27 and arrived off Toulon on October 30. After several delays, Giraud and his party were brought on board, and a PBY Catalina

flying boat subsequently flew Wright, Giraud, and the others back to Gibraltar, the new Operation Torch headquarters, to confer with generals Eisenhower and Clark. Captain Jerauld Wright was awarded his first Legion of Merit

in recognition of his participation in Operation Kingpin.

D-Day for Operation Torch

D-Day for Operation Torch

, November 8, 1942, saw over 73,000 American and British troops landed at Casablanca

, Oran

, and Algiers. However, the most significant development was on the diplomatic and political front when U.S. consul general Robert D. Murphy alerted the Allied high command about unexpected presence of Admiral de la flotte

Jean Darlan, the head of the Vichy French military, who was visiting his ill son in Algiers. Darlan's presence complicated the pre-invasion arrangements with Général Henri Giraud

. Darlan pointed out to Murphy that he out-ranked Giraud whom Darlan maintained had little influence within the French military.

After a ceasefire was reached in Algiers, General Eisenhower sent a delegation to resolve the situation and broker a ceasefire with all French North African forces. Captain Jerauld Wright accompanied General Clark who concluded that Darlan could, with certain conditions, deliver the general ceasefire and oversee the post-invasion occupation, and that Giraud lacked the political ability to accomplish these goals. Eisenhower endorsed Clark's recommendation, which caused a political firestorm within the Allied governments because of Darlan's connection to Vichy. About Giraud and Darlan, Wright observed:

Admiral Harold R. Stark noted in Wright's December 1942 fitness report that:

At the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, President

Franklin D. Roosevelt

, Prime Minister

Winston Churchill

, and the Combined Chiefs of Staff

(CCS) made the decision to conduct shelve plans for Operation Sledgehammer

, and instead progress operations in Sicily

(Operation Husky) and Italy

(Operation Avalanche). Finally, Admiral Darlan was assassinated on December 24, 1942, and Charles de Gaulle

would ultimately out-maneuver and marginalize Henri Giraud

to become the sole leader of the Free French movement

.

Captain Jerauld Wright joined the staff of Vice Admiral

Captain Jerauld Wright joined the staff of Vice Admiral

H. Kent Hewitt, USN, the Commander, U.S. Naval Forces, Northwest Africa Waters (COMNAVNAW), as its assistant chief of staff.

Hewitt would command the "Western Naval Task Force", which would land U.S. Seventh Army under Lieutenant General

George S. Patton in the Gulf of Gela near Palermo

for Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily. Vice-Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay

, RN, would command the Eastern Naval Task Force, which would land the British Eighth Army under General

Sir Bernard L. Montgomery near Syracuse

. Admiral

Sir Andrew B. Cunningham, RN

, would command all Allied naval forces for Operation Husky, and General

Dwight D. Eisenhower, United States Army

, would be in overall command of the Sicily invasion.

The Western Naval Task Force consisted of three subordinated forces, Task Force 80 (code name JOSS) under the command of Rear Admiral Richard L. Conolly to land the 3rd Infantry Division, Major General Lucian Truscott

commanding, on beaches near Licata

. Task Force 82 (code name DIME) under Rear Admiral land to 1st Infantry Division, Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen commanding, on beaches near Gela

. Task Force 85 (code name CENT) under the command of Rear Admiral Alan Kirk was to land the 45th Infantry Division, Major General Troy Middleton commanding, on beaches near Scoglitti

.

Wright worked closely with his U.S. Army counterparts, and he considered Patton "a great fellow" who grew to appreciate the effectiveness of naval gun support for his landing force. However, Wright was critical of Lieutenant General Carl A. Spaatz, USAAF, and Air Vice-Marshal

Sir Arthur Coningham, RAF

, regarding the lack of cooperation on close air support from the Allied air forces. Wright did praise Air Vice-Marshal Sir Hugh Pughe Lloyd, RAF, for providing air support from Malta.

The loading of ships and landing craft of the Western Naval Task Force was completed on July 8, 1943, with Vice Admiral Hewitt and his staff embarking on the USS Monrovia, the invasion force's flagship. D-Day was July 10, and Patton's troops stormed ashore and began their history-making drive for Messina.

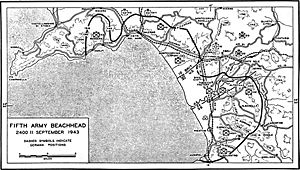

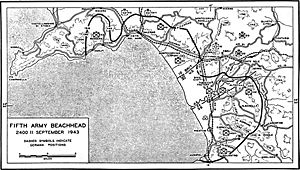

Operation Avalanche was the Allied invasion of the Italian mainland with amphibious landings at Salerno

Operation Avalanche was the Allied invasion of the Italian mainland with amphibious landings at Salerno

, with additional landing at Calabria

(Operation Baytown

) and Taranto

(Operation Slapstick

).

For the Salerno landing, Captain Jerauld Wright faced two major challenges in his capacity as the assistant chief of staff for U.S. Naval Forces, Northwest Africa Waters (NAVNAW), namely the shortage of U.S. escort vessels and a shortage of landing craft. While Wright was able to secure additional British escorts, landing craft would remain a persistent problem given the competing demands from Operation Overlord

and the Pacific Theater of Operations

, with Wright noting: "LST's don't grow on trees." On the other hand, two developments were welcomed by Wright and his fellow invasion planners, including U.S. escort aircraft carriers (CVE) would provide much needed off-shore close air support

for the landing force, and the news that Major General E. J. House would oversee tactical air support for the ground forces using aircraft from of the Northwest African Air Force.

However, Wright felt that the Army's decision to forgo pre-invasion naval gun bombardment was ill-considered, even for the sake of maintaining the element of surprise.

The invasion force got underway, with Vice Admiral

H. Kent Hewitt, Wright, and the NAVNAW staff embarked on the USS Ancon, Hewitt's flagship for Operation Avalanche. While en route, Wright heard the announcement about the Armistice with Italy by General Dwight D. Eisenhower

, the supreme allied commander, on September 9. While this removed the Italian military from the battlefield, German Army forces in Italy under Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring

were not bound by this agreement. The immediate objective for Operation Avalanche was to secure the Gulf of Salerno

and capture Naples

.

September 9, 1943 was D-Day for Operation Avalanche as the 36th Infantry Division, under the command of Major General Fred L. Walker USA, stormed ashore at Salerno under heavy fire from German tanks, artillery, and machine guns. During the landings, on the morning of September 11, Wright witnessed a radio-controlled flying bomb

severely damage the USS Savannah

, a Brooklyn-class

light cruiser

. A powerful German counter-attack on September 13 threatened to drive a wedge into the Salerno bridgehead, but it was beaten back by a powerful Allied air-land-sea assault, forcing a German retreat. With the Fifth U.S. Army under Lieutenant General Mark Clark

driving for Naples, Admiral Hewitt and Wright returned to Malta to give a full report on Operation Avalanche to General Eisenhower. Captain Jerauld Wright was awarded a second Legion of Merit

for his contributions on Operation Husky and Operation Avalanche.

In October 1943, Captain Jerauld Wright was detached from U.S. Naval Forces, Northwest Africa Waters (NAVNAW) to take command of the USS Santa Fe (CL-60)

In October 1943, Captain Jerauld Wright was detached from U.S. Naval Forces, Northwest Africa Waters (NAVNAW) to take command of the USS Santa Fe (CL-60)

, a Cleveland-class

light cruiser

, nicknamed the "Lucky Lady." Wright relieved Captain Russell Berkey on December 15, 1943. Santa Fe was the flagship

of Cruiser Division 13, Rear Admiral

Laurance T. DuBose commanding, which also included USS Birmingham (CL-62)

, USS Mobile (CL-63)

, and USS Reno (CL-96)

. During December 1943, Santa Fe underwent amphibious training off San Pedro, California.

On January 13, 1944, Santa Fe set sail from California for the Marshall Islands

, as part of the invasion force for Operation Flintlock

. Santa Fe served as an escort for the Northern Attack Force (Task Force 53), Rear Admiral Richard L. Conolly commanding, which was tasked to capture Roi-Namur and the northern half of the Kwajalein atoll

. Santa Fe joined the bombardment force (Task Group 53.5), Rear Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf

commanding, that provided naval gunfire support for U.S. Marine landing forces at Kwajalein

which was secured on February 4.

Following a lay-over at Majuro

, Santa Fe participated in air raids against Truk

and Saipan

as part of Task Force 58 during February 1944. Captain Wright received a Letter of Commendation for his actions as the commanding officer of the Santa Fe during this engagement. From March 15 through May 1, 1944, Santa Fe was part of Task Group 58.2, Rear Admiral Joseph J. Clark

commanding, which provided air support for amphibious landings at Emirau Island

and Hollandia

while also participating in air raids against Japanese garrisons on Palau

, Yap

, Wakde

, Woleai

, Sawar, Satawan

, and Ponape

,as well as major air strike against the Japanese naval base at Truk. Santa Fe also participated in the shore bombardment of Wakde and Sawar.

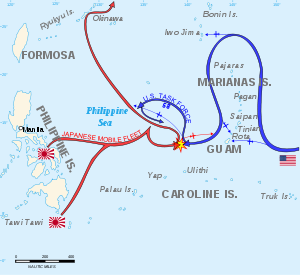

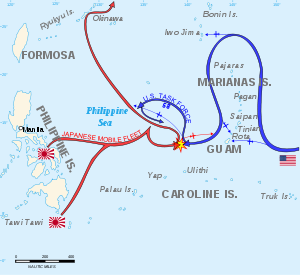

On June 15, 1944, Santa Fe participated in landings on Saipan, Guam, and Tinian

(Operation Forager) as a part of the U.S. Fifth Fleet under the overall command of Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance

. On June 19, Japanese carrier aircraft began attacking the Fifth Fleet which remained close to the beachhead on orders from Spruance. Wright concurred that this controversial decision was the correct one given the importance of protecting the landing force. During the ensuing Battle of the Philippine Sea

, Santa Fe's anti-aircraft guns helped to protect the fleet during these enemy air attacks while American naval aviators counter-attacked the Japanese fleet. Later, on June 20, Santa Fe ignored possible Japanese submarine activity when she turned on her lights to help guide returning American aircraft back to their carriers during highly hazardous night landings. After air strikes on Pagan Island

, Santa Fe returned to Eniwetok for reprovisioning.

In August, Santa Fe joined Task Group 38.3, Rear Admiral Frederick C. Sherman

commanding, for the invasion of Peleliu

and Angaur

(Operation Stalemate II) as part of the U.S. Third Fleet under the overall command of Admiral

William F. Halsey, and carrier air attacks to neutralize Japanese air bases on Babelthuap and Koro

in preparation for the upcoming Philippines campaign led by General

Douglas MacArthur

. During air raids on Formosa

in October, the heavy cruiser

Canberra

and light cruiser

Houston

were seriously damaged by aerial torpedo

es. Santa Fe was part of a covering force (Task Force 30.3), nicknamed "CripDiv 1," formed to protect the damaged cruisers as they were being towed back for Uliti for repairs. The final engagements that Wright participated in as the commanding officer of the USS Santa Fe were the invasion of Leyte

and the Battle of Leyte Gulf

. Captain Jerauld Wright received the Silver Star

in recognition of his participation in the towing of the Canberra and Houston back to Uliti.

In November 1944, Rear Admiral Jerauld Wright took command of Amphibious Group Five, a newly-created unit of the Amphibious Forces, U.S. Pacific Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner. Wright's group would be involved in the invasion of the Ryukyu Islands

In November 1944, Rear Admiral Jerauld Wright took command of Amphibious Group Five, a newly-created unit of the Amphibious Forces, U.S. Pacific Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner. Wright's group would be involved in the invasion of the Ryukyu Islands

(Operation Iceberg), the island of Okinawa being the key objective. Once taken, U.S. forces would use Okinawa as a staging area for the eventual invasion of Japan

, and a base for the B-29 Superfortress bombers

of the U.S. Seventh Air Force to attack the Japanese home islands

. Amphibious Group Five would transport the 2nd Marine Division, Major General Thomas E. Watson

, USMC

, commanding, with Wright flying his flag from the USS Ancon (AGC-4)

.

For Operation Iceberg, Wright's force was designated Demonstration Group Charlie (Task Group 51.2), whose mission was to serve as a decoy force working in conjunction with the Southern Attack Force (Task Force 55) commanded by Rear Admiral John L. Hall

while the Western Islands Group (Task Group 51.1) under Rear Admiral Ingolf N. Kiland and the 77th Infantry Division secured Kerama Retto

and other offshore islands before landing at Ie Shima. Task Group 51.2 would subsequently serve as a floating reserve for the U.S. Tenth Army (Task Force 56), commanded by Lieutenant General Simon B. Buckner

, USA

, before returning to Saipan.

Wright was ordered to Pearl Harbor

to begin planning the invasion of the Japanese home islands, which would begin with Operation Olympic, the invasion of the southern island of Kyūshū

. Wright's Amphibious Group Five would be part of the 5th Amphibious Force, commanded by Vice Admiral Harry W. Hill, which would land the V Amphibious Corps

(VAC) on the west coast in the Kaminokawa - Kushikino area. Amphibious Group Five would consist of four old battleships, ten cruisers, fourteen destroyers, and seventy-four support craft. However, Operation Olympic and the follow-up invasion of Honshū

(Operation Coronet) were cancelled following the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

. Rear Admiral Jerauld Wright was awarded a Bronze Star

, with a combat "V" devise

, for his leadership as the commander of Task Group 51.2 during Operation Iceberg.

_80-g-495711.jpg) Rear Admiral Jerauld Wright took command of Cruiser Division Six (CruDiv 6), with the USS San Francisco (CA-38)

Rear Admiral Jerauld Wright took command of Cruiser Division Six (CruDiv 6), with the USS San Francisco (CA-38)

, a New Orleans-class

heavy cruiser

, serving as his flagship. In early October 1945, CruDiv 6 was assigned to assist the post-surrender activities and general-purpose peace-keeping duties throughout the Yellow Sea

and Gulf of Bohai region as a unit of the U.S Seventh Fleet under the command of Vice Admiral

Thomas C. Kinkaid

. Wright's force showed the flag, making port visits at , Tientsin, Tsingtao, Port Arthur

, and Chinwangtao. At the final port call at Inchon, Wright acted as the senior-ranking member of the committee that accepted the surrender of Japanese naval forces throughout Korea.

(OPNAV) as the head of its Operational Readiness Division, helping to organize this newly-created organization. Other OPNAV divisions created were Plans (OP-31), Combat Intelligence (OP-32), Operations (OP-33), and Anti-submarine Warfare (OP-35) within the Chief of Naval Operations. Wright organized OP-34 into four sections, and working with his sister divisions, Wright directed the development of a host of manuals on tactical doctrine based upon experience from World War II. Wright involved civilian think tanks, such as the Operation Evaluation Group (OEG), in projects undertaken by OP-34. CNO Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz appointed Wright to chair the U.S. Navy's Air Defense Committee to help improve fleet air defenses. Wright also succeeded Rear Admiral Walter DeLaney as the chairman of the Joint Army-Navy Assessment Committee

(JANAC), an inter-service agency set up in 1943 to analyze and assess of Japanese naval

and merchant marine shipping losses caused by U.S. and Allied forces during World War II.

.jpg) On November 24, 1948, Rear Admiral Jerauld Wright assumed command of Amphibious Forces U.S. Atlantic Fleet (COMPHIBLANT), a position that he held through November 1, 1950. Based at the Norfolk Naval Station, Wright would be responsible for three major subordinate commands, Amphibious Group Two, Amphibious Group Four and the Little Creek Naval Amphibious Base. COMPHIBLANT also included Amphibious Training, an Amphibious Air Control Group, a Naval Beach Group, a Detached Group, and a Mediterranean Group. Wright's flagship

On November 24, 1948, Rear Admiral Jerauld Wright assumed command of Amphibious Forces U.S. Atlantic Fleet (COMPHIBLANT), a position that he held through November 1, 1950. Based at the Norfolk Naval Station, Wright would be responsible for three major subordinate commands, Amphibious Group Two, Amphibious Group Four and the Little Creek Naval Amphibious Base. COMPHIBLANT also included Amphibious Training, an Amphibious Air Control Group, a Naval Beach Group, a Detached Group, and a Mediterranean Group. Wright's flagship

was the USS Taconic (AGC-17)

, an Adirondack-class amphibious force command ship. The most significant accomplishment during Wright's tour of duty as COMPHIBLANT was PORTREX, a multi-service amphibious assault exercise held from February 25 to March 11, 1950. PORTREX was the largest peacetime amphibious exercise up to that time and it was staged to evaluate joint doctrine for combined operations

, test new equipment under simulated combat conditions and provide training for the defense of the Caribbean.

Over 65,000 men and 160 ships were involved, and it was climaxed by a combined amphibious and airborne

assault on Vieques Island, a first in military history. The success of PORTREX offered a prelude for future amphibious operations, including the landings at Inchon during the Korean War

. Jerauld Wright received his third star

, effective September 14, 1950, at the conclusion of his tour of duty as COMPHIBLANT.

, composed of military representatives from the United States

, Great Britain

, and France

. At the time of Wright's tour of duty, SG membership was General of the Army

Omar Bradley

, United States Army

, Air Marshal

Lord Tedder

, Royal Air Force

and Lieutenant General

Paul Ely, French Army

The Standing Group was charged with providing policy guidance and military-related information to NATO's various regional planning groups, including General Dwight D. Eisenhower

at SHAPE

headquarters. The Standing Group undertook short-term (STDP), mid-term (MTDP), and long-range (LTDP) strategic military planning for the NATO alliance, as well as making recommendations regarding NATO's unified military command structure, which included the creation of a Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT) billet.

Vice Admiral Jerauld Wright became the Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Naval Forces Eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean

Vice Admiral Jerauld Wright became the Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Naval Forces Eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean

(CINCNELM), an important U.S. Navy fleet command, effective June 14, 1952. CINCELM's area of responsibility (AOR) stretched from the eastern Atlantic through the Indian Ocean to Singapore

.

Wright's operational control over the Sixth Fleet proved to be a source of friction with Admiral

Lord Louis Mountbatten

, RN

, NATO's Commander-in-Chief Allied Forces Mediterranean (CINCAFMED). Mountbatten felt that the Sixth Fleet should be assigned to his command while Wright wanted to maintain control of the fleet, particularly its nuclear-armed aircraft carriers, pursuant to both U.S. Navy policy and Federal law

. The dispute tested the diplomatic skills of both men. CINCNELM forces participated in NATO Operation Mariner and Operation Weldfast exercises during 1953, and units of the Sixth Fleet did participate in NATO exercises while staying under U.S. control.

As CINCNELM, Wright maintained strong diplomatic ties with allies within his area of responsibility. He made a 14-day goodwill trip to the Middle East that culminated with a courtesy call with the newly-crowned King Saud bin Abdul Aziz

in Jidda, Saudi Arabia

. Later, Wright attended the coronation ceremonies of King Hussein

of Jordan

in May 1953. In June 1953, Wright served as the senior U.S. Navy representative at the coronation pageant of Queen

Elizabeth II, including flying his flag from the heavy cruiser USS Baltimore

during the Coronation Naval Review of Spithead

on June 15. Admiral Wright also made the arrangements for U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom

Winthrop Aldrich to present a bronze plaque of John Paul Jones

from the U.S. Naval Historical Center

to the British government, initiating his long-time association with the famous naval hero of the American Revolution

.

During a high-level conference in Washington

from October 20 to November 4, 1953, Wright was informed that that CINCNELM was be become a sub-ordinate command of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet reporting directly to Admiral Lynde D. McCormick

, the Commander-in-Chief U.S. Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANTFLT). Also, Wright would become the head of NATO's Eastern Atlantic Area, reporting to Admiral McCormick, the first Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic

(SACLANT). Jeruald Wright was promoted to the rank of Admiral

effective April 1, 1954.

Admiral Wright's final command assignment proved to be the most challenging undertaking in his career as he literally took on three concurrent roles, namely Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANTFLT), Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Atlantic Command (CINCLANT) and Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT) of NATO's Allied Command Atlantic (ACLANT). While his nomination to become CINCLANTFLT and CINCLANT was made by the President of the United States

Admiral Wright's final command assignment proved to be the most challenging undertaking in his career as he literally took on three concurrent roles, namely Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANTFLT), Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Atlantic Command (CINCLANT) and Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT) of NATO's Allied Command Atlantic (ACLANT). While his nomination to become CINCLANTFLT and CINCLANT was made by the President of the United States

, subject to the advice and consent of the United States Senate

, Wright's appointment to become SACLANT was subject to the approval of the North Atlantic Council

. Fortunately, Wright was a known commodity since he had served Wright had served as the deputy U.S. representative to NATO's Standing Group from November 1950 to February 1952.

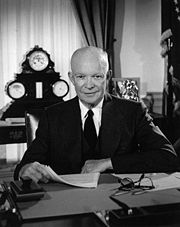

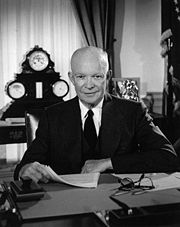

President Dwight D. Eisenhower

noted in his February 1, 1954 announcement:

Admiral Jerauld Wright assumed command of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, the U.S. Atlantic Command, and Allied Command Atlantic on April 12, 1954, relieving Admiral Lynde D. McCormick

who had been the first Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic.

Admiral Wright's command responsibilities included acting as Commander-in-Chief U.S. Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANTFLT), one of the two major fleet commands within the U.S. Navy with responsibility for all naval operations throughout the Atlantic Ocean; Commander-in-Chief U.S. Atlantic Command (CINCLANT), a unified command

responsible for U.S. military operation throughout the Atlantic Ocean geographical region; and Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic

(SACLANT), one of the two principal military commands for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), responsible for keeping the sea lanes open between the United States and Europe.

Admiral Jerauld Wright inherited a U.S. Atlantic Fleet in transition as the U.S. Navy was going through a modernization period to replace warships and aircraft built during World War II.

For Admiral Jerauld Wright, the best method to evaluate fleet readiness for the U.S. Atlantic Fleet was the staging and execution of naval exercises like Lantflex I-57. Among the high-level observers for this naval exercise were the President

For Admiral Jerauld Wright, the best method to evaluate fleet readiness for the U.S. Atlantic Fleet was the staging and execution of naval exercises like Lantflex I-57. Among the high-level observers for this naval exercise were the President

Dwight D. Eisenhower

and many other members of the US cabinet. The highlight of Lantflex I-57 was the landing of two A3D

Sky Warriors and two F8U Crusaders on board the USS Saratoga

that had been launched from the USS Bon Homme Richard operating in the Pacific

, the first carrier-to-carrier transcontinental flight in history.

Other Atlantic Fleet exercises included Operation Springboard, the annual winter naval maneuvers in the Caribbean Sea

. Units of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet and the Royal Canadian Navy participated in Operation Sweep Clear III, a bilateral mine warfare

exercise, between July and August 1958. Also, in 1960, the U.S. Atlantic Fleet initiated UNITAS, an annual multilateral series of exercises between the South Atlantic Force (SOLANTFOR) and Latin America

n navies. As SACLANT, Wright coordinated such NATO naval exercises as Operation Sea Watch, a convoy escort exercise. However, the most significant naval exercise during Admiral Wright's tour of duty was Operation Strikeback

, a ten-day exercise involving over 250,000 men, 300 ships, and 1,500 aircraft during September 1957, which was the largest naval exercise staged by NATO up to that time. Under Admiral Wright, the U.S. Atlantic Fleet also took the lead on the field of operational testing and evaluation (OT&E) of systems and tactics, particularly regarding anti-submarine warfare for the United States Navy, with the Operational Development Force (OPDEVFOR), under the command of Rear Admiral

William D. Irvin, serving as the lead agency for this effort.

Finally, in February 1959, when several transatlantic cables

off Newfoundland

were cut and the Soviet fishing trawler

MV Novorossisk operating in the vicinity at the time of the break, the radar-picket ASW destroyer USS Roy O. Hale (DER-336)

was dispatched to enforce the 1884 Convention for the Protection of Submarine Cables. On the August 26, the Hale sent a boarding party to the Novorossisk to investigate and determined that there were no indications of intentions "other than fishing." A diplomatic protest was lodged, but there were no more breaks.

Admiral Jerauld Wright stated in a Time magazine

Admiral Jerauld Wright stated in a Time magazine

article from 1958 that: "The primary mission of every combat ship in the Atlantic Fleet is antisubmarine. Everything else is secondary." Given his previous exposure to anti-submarine warfare

(ASW) doctrine at OP-34, Wright was a natural fit for overseeing the anti-submarine renaissance during his tour of duty as CINCLANTFLT. One significant innovation was the Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS

), a network of underwater hydrophones and listening posts designed to track the movement of submarines. The first operational test of SOSUS was done during the ASDevEx 1-54 exercise from April 6 to June 7, 1954.

However, 1958 news accounts about the growing threat of the Soviet snorkel

-equipped diesel-electric submarine force began to gain the attention of the American public. Central Intelligence Agency

Director Allen Dulles was reported to have said that ten missile-carrying Soviet submarines could destroy 1600 square miles (4144 km²) of the industrial-rich eastern seaboard in a sneak attack. Also, an Associated Press

dispatch, dated April 14, 1958, quoted U.S. Congressman

Carl Durham (D

-North Carolina

, who said that 184 Soviet submarines had been sighted off the U.S. Atlantic coast during 1957.

Chief of Naval Operations

(CNO) Arleigh A. Burke

had responded on April 1 by creating Task Force Alfa, a hunter-killer (HUK) flotilla under the command of Rear Admiral

John S. Thach, which would develop new ASW tactics to counter this growing Soviet submarine threat.

Admiral Wright's personal contribution provided the first look at a missile-armed Soviet submarine, a Project AV611/Zulu-V

variant armed with two R-11FM/SS-1b Scud-A ballistic missiles. Wright also spearheaded the establishment of the SACLANT ASW Research Centre

, created on May 2, 1959 in La Spezia, Italy, to serve as a clearinghouse for NATO's anti-submarine efforts. The efforts of the Atlantic Fleet to develop and implement new ASW tactics during Admiral Wright's tour of duty laid the groundwork for the success that the U.S. Navy had in locating and tracking Soviet submarines during the Cuban Missile Crisis

.

One example of soft power

One example of soft power

regarding sea power is showing the flag. In his capacity as CINCLANT/CINCLANTFLT/SACLANT, Admiral Wright and his staff participated 18 formal presentations and 62 NATO and joint military planning meetings during his six-year tour of duty in these positions.

announced on December 31, 1959, that Admiral Jerauld Wright was stepping down as CINCLANTFLT/CINCLANT/SACLANT, with President

Dwight D. Eisenhower reflect wider sentiment when he noted:

On February 29, 1960, Admiral Jerauld Wright stepped down as CINCLANTFLT/CINCLANT/SACLANT, retiring after 46 years of service in the United States Navy effective March 1, 1960. Admiral Wright received a second Distinguished Service Medal

in recognition of his six year as CINCLANTFLT/CINCLANT/SACLANT from Secretary of the Navy William B. Franke

in a special ceremony held on board the supercarrier

USS Independence (CVA-62)

.

Notes

All DOR referenced from Official U.S. Navy Biography.

Citation excerpt (1942)

Citation excerpt (1942)

Gold Star in lieu of the Second Distinguished Service Medal (1960)

Citation Excerpt (1944):

Citation Excerpt (1944):

Citation excerpt

Citation excerpt

Gold Star in lieu of a second Legion of Merit

Citation Excerpt:

Citation Excerpt:

(Fleet Clasp), European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal

, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal

, World War II Victory Medal

, National Defense Service Medal

, the Legion of Honor (with rank of Chevalier) from the Government of France, and the Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Orange-Nassau

from the Government of the Netherlands.

Jerauld Wright was recalled to active duty on January 12, 1961 to serve as the U.S. Navy representative on the Central Intelligence Agency

(CIA) Board of National Estimates (BNE), and after completing his BNE assignment, and was released from active duty effective May 13, 1963.

The Office of National Estimates (ON/E) had been created in 1950 and was responsible for issuing National Intelligence Estimate

(NIE), which "should deal with matters of wide scope relevant to the determination of basic policy, such as the assessment of a country's war potential, its preparedness for war, its strategy capabilities and intentions, its vulnerability to various forms of direct attack or indirect pressures." The ON/E Board included prominent American citizens with distinguished intelligence, academic, military, and diplomatic credentials, who would oversee NIE documents.

regarding the ambassadorship to the Republic of China

in Taiwan

. The current U.S. ambassador, retired Admiral Alan G. Kirk

, was in declining health and had recommended Wright as his replacement. After discussing it with his family, Wright accepted. Ambassador Wright presented his credentials to President

Chiang Kai-shek

on June 29, 1963. Ambassador Wright won praise for his sensitive handling of the aftermath to the assassination of John F. Kennedy

from both the embassy staff and government officials of the Republic of China. Wright also closely monitored the tense military situation between Taiwan and mainland China, particularly the potential flashpoint of Qemoy. Wright also successfully concluded a Status of Forces Agreement

with the Republic of China. On July 25, 1965, Jerauld Wright stepped down as the U.S. Ambassador of the Republic of China, closing the final chapter on his public life.

. She graduated from Miss Porter's School

and made her debut in 1924 with Janet Lee, the future mother of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

. She worked for the Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform (WONPR) in New York. In 1933, Phyllis Thompson joined the Federal Alcohol Control Administration

(FACA) in Washington, D.C.

and subsequently worked, briefly, at the Federal Housing Administration

(FHA). In 1935, she became the society editor for the Washington Evening Star. Phyllis Thompson meet Jerry Wright through his sister, Marjorie Wright Key, who had also attended Miss Porter's School. Their marriage took place at St. Andrew's Dune Church, in , on July 23, 1938, which Phyllis wrote as her last wedding notice for the Washington Evening Star as their society editor. Jerry and Phyllis Wright had two children — Marion Jerauld Wright (1941 - ) and William Mason Wright (1945 - ).

Phyllis Wright wrote about her experiences as a Navy wife and the wife of an ambassador in a Navy Wife's Log (1978) and a Taiwan Scrapbook (1992) She was a former president of the Sulgrave Club

and a member of the Metropolitan and Chevy Chase clubs. Phyllis Thompson Wright died on October 20, 2002, at the National Naval Medical Center

in Bethesda, Maryland

, from cancer

. She was survived by her two children, Marion Wright of Denver and William Wright of Arlington. She was interred with her late husband at the Arlington National Cemetery

.

. His artwork was displayed in exhibits at the Brook Club, the Knickerbocker Club

, and the Sulgrave Club

.

, serving as its president from 1959–1960 and was a frequent contributor to its Proceedings, including an insightful December 1951 article on the challenges facing the newly-created NATO. Wright's other memberships included the Alibi Club

, the Chevy Chase Club, the Metropolitan Club

, the Knickerbocker Club

, the Brook Club, Alfalfa Club

, and the United States Navy League.

(ret.), died on April 27, 1995, of pneumonia in Washington, D.C.

, at the age of 96. He was survived by his wife of 56 years, Phyllis; a son, William Mason Wright of Arlington; and a daughter, Marion Jerauld Wright of Denver. He was buried with full military honors in Section 2 of the Arlington National Cemetery

next to his father and mother, and would be joined by his wife Phyllis upon her death in 2002.

s from the Rose Polytechnic Institute

, the University of Massachusetts Amherst

, and the William and Mary College.

(74°2′S 116°50′W) is an ice-covered island 35 miles (60 km) long, lying at the north edge of Getz Ice Shelf

about midway between Carney Island

and Martin Peninsula

, on the Bakutis Coast

, Marie Byrd Land

. Delineated from air photos taken by U.S. Navy Operation Highjump in January 1947, it was named by the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names

(US-ACAN) after Admiral Jerauld Wright who was in over-all command of Operation Deep Freeze

during the International Geophysical Year

1957-58.

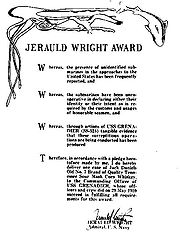

In light of the growing threat of Soviet submarine activity within his command area, as well as in retaliation for the recent aggressive depth-charging

In light of the growing threat of Soviet submarine activity within his command area, as well as in retaliation for the recent aggressive depth-charging

of the near Vladivostok

, Admiral Wright issued the following challenge:

On May 29, 1959, the , a working in conjunction with Patrol Squadron 5 (VP-5), chased a Soviet submarine near Iceland for nine hours before forcing it to surface, and its commanding officer, Lt. Commander Theodore F. Davis, received the case of whiskey from Admiral Wright and the distinction of being the first to surface a Soviet submarine by the U.S. Navy.

Admiral Wright Award would be presented, with an accompanying case of whiskey, on two other occasions:

, RN

, spearheaded the effort to restore the Scottish birthplace of John Paul Jones

back to its original 1747 condition. The cottage that houses a museum dedicated to the life and accomplishments of John Paul Jones was opened in 1993, and it is situated on the original location on the estate of Arbigland

in the Stewartry of Kirkcudbright

.

Admiral (United States)

In the United States Navy, the United States Coast Guard and the United States Public Health Service Commissioned Corps, admiral is a four-star flag officer rank, with the pay grade of O-10. Admiral ranks above vice admiral and below Fleet Admiral in the Navy; the Coast Guard and the Public Health...

Jerauld Wright, USN, (June 4, 1898 – April 27, 1995) served as the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Atlantic Command

United States Joint Forces Command

United States Joint Forces Command was a former Unified Combatant Command of the United States Armed Forces. USJFCOM was a functional command that provided specific services to the military. The last commander was Army Gen. Raymond T. Odierno...

(CINCLANT) and the Commander-in-Chief of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet (CINCLANTFLT), and became the second Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic

Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic

The Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic was one of two supreme commanders of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation , the other being the Supreme Allied Commander Europe . The SACLANT led Allied Command Atlantic, based at Norfolk, Virginia...

(SACLANT) for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), from April 1, 1954 to March 1, 1960, serving longer in these three positions than anyone else in history.

Following World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, Wright served as a naval aide for Presidents Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge

John Calvin Coolidge, Jr. was the 30th President of the United States . A Republican lawyer from Vermont, Coolidge worked his way up the ladder of Massachusetts state politics, eventually becoming governor of that state...

and Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover was the 31st President of the United States . Hoover was originally a professional mining engineer and author. As the United States Secretary of Commerce in the 1920s under Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, he promoted partnerships between government and business...

. A recognized authority on naval gunnery, Wright served in the European

European Theater of Operations

The European Theater of Operations, United States Army was a United States Army formation which directed U.S. Army operations in parts of Europe from 1942 to 1945. It referred to Army Ground Forces, United States Army Air Forces, and Army Service Forces operations north of Italy and the...

and Pacific

P.T.O.: Pacific Theater of Operations

P.T.O. , released as in Japan, is a console strategy video game released by Koei. It was originally released for the PC-88 in 1989 and had been ported to various platforms, such as the Sega Mega Drive and the Super Nintendo...

theaters during World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, developing expertise in amphibious warfare

Amphibious warfare

Amphibious warfare is the use of naval firepower, logistics and strategy to project military power ashore. In previous eras it stood as the primary method of delivering troops to non-contiguous enemy-held terrain...

and coalition warfare planning. After the war, Wright was involved in the evolution of the military structure of NATO as well as overseeing the modernization and readiness of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet during the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

.

Upon his retirement from the U.S. Navy, Wright subsequently served on the Central Intelligence Agency

Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency is a civilian intelligence agency of the United States government. It is an executive agency and reports directly to the Director of National Intelligence, responsible for providing national security intelligence assessment to senior United States policymakers...

's National Board of Estimates (NBE) and as the U.S. Ambassador to the Republic of China (Taiwan)

United States Ambassador to China

The United States Ambassador to China is the chief American diplomat to People's Republic of China . The United States has sent diplomatic representatives to China since 1844, when Caleb Cushing, as Commissioner, negotiated the Treaty of Wanghia. Commissioners represented the United States in...

.

Early years

Amherst, Massachusetts

Amherst is a town in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States in the Connecticut River valley. As of the 2010 census, the population was 37,819, making it the largest community in Hampshire County . The town is home to Amherst College, Hampshire College, and the University of Massachusetts...

, the second son of Major General

Major general (United States)

In the United States Army, United States Marine Corps, and United States Air Force, major general is a two-star general-officer rank, with the pay grade of O-8. Major general ranks above brigadier general and below lieutenant general...

William M. Wright

William M. Wright

William Mason Wright was a Lieutenant General in the United States Army.Born in Newark, New Jersey on September 24, 1863, he was the son of Army Colonel Edward H. Wright , a career officer whose service included assignments as Aide-de-Camp to Generals Winfield Scott and George B. McClellan. William M...

, United States Army

United States Army

The United States Army is the main branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is the largest and oldest established branch of the U.S. military, and is one of seven U.S. uniformed services...

, (1863–1943) and the former Marjorie R. Jerauld (1867–1954), who also had another son, William Mason Wright, Jr. (1893–1977), and a daughter, Marjorie Wright (1900–1985).

Life for young Jerry Wright was a succession of U.S. Army posts, such as Fort Porter

Fort Porter

Fort Porter was constructed between 1841 and 1844 at Buffalo in Erie County, New York and named for General Peter Buell Porter. The site was bounded by Porter Avenue, Busti Avenue and the Erie Barge Canal. It was initially a square masonry two-story redoubt, 62 feet square, with crenelated walls...

, Fort Omaha

Fort Omaha

Fort Omaha, originally known as Sherman Barracks and then Omaha Barracks, is an Indian War-era United States Army supply installation. Located at 5730 North 30th Street, with the entrance at North 30th and Fort Streets in modern-day North Omaha, Nebraska, the facility is primarily occupied by ...

, the Presidio

Presidio of Monterey, California

The Presidio of Monterey, located in Monterey, California, is an active US Army installation with historic ties to the Spanish colonial era. Currently it is the home of the Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center .-Spanish fort:...

, and the Jefferson Barracks, as well as overseas tours of duty in Cuba and the Philippines

Philippine-American War

The Philippine–American War, also known as the Philippine War of Independence or the Philippine Insurrection , was an armed conflict between a group of Filipino revolutionaries and the United States which arose from the struggle of the First Philippine Republic to gain independence following...

. Keeping the family together while his father pursued an active military career was his mother, nicknamed "The Field Marshal" by her husband. Jerry remembered his mother fondly: "She was a tiger with her young."

Jerry's father was a veteran of the Spanish-American War

Spanish-American War

The Spanish–American War was a conflict in 1898 between Spain and the United States, effectively the result of American intervention in the ongoing Cuban War of Independence...

, the Boxer Rebellion

Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also called the Boxer Uprising by some historians or the Righteous Harmony Society Movement in northern China, was a proto-nationalist movement by the "Righteous Harmony Society" , or "Righteous Fists of Harmony" or "Society of Righteous and Harmonious Fists" , in China between...

, and World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, during which he commanded the 89th Division in the St. Mihiel offensive

Battle of Saint-Mihiel

The Battle of Saint-Mihiel was a World War I battle fought between September 12–15, 1918, involving the American Expeditionary Force and 48,000 French troops under the command of U.S. general John J. Pershing against German positions...

and the Third Corps. He was a recipient of the Distinguished Service Medal

Distinguished Service Medal (United States)

The Distinguished Service Medal is the highest non-valorous military and civilian decoration of the United States military which is issued for exceptionally meritorious service to the government of the United States in either a senior government service position or as a senior officer of the United...

. Following the war, General Wright commanded the Ninth Corps at the Presidio

Presidio of San Francisco

The Presidio of San Francisco is a park on the northern tip of the San Francisco Peninsula in San Francisco, California, within the Golden Gate National Recreation Area...

and the Department of the Philippines

Philippine Department

The Philippine Department was a regular US Army unit, defeated in the Philippines, during World War II. The mission of the Philippine Department was to defend the Philippine Islands and train the Philippine Army...

. While his father was assigned to the newly-created U.S. Army General Staff before World War I, Jerry met William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft

William Howard Taft was the 27th President of the United States and later the tenth Chief Justice of the United States...

. Later, Jerry accompanied his father on inspection tours of U.S. military installations in the Philippines. During this tour, he was deeply impressed the naval squadron visiting Manila. His growing interest in a naval career was further encouraged by this father, giving his son a very practical perspective:

- Take a good look at the Navy. Soldiers have to tramp miles, sleep in the mud, eat cold rations, and live for days in wet clothes. Sailors have warm bunks, eat hot meals, and wear dry socks every day.

Prior to going to the U.S. Naval Academy

United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy is a four-year coeducational federal service academy located in Annapolis, Maryland, United States...

in Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis is the capital of the U.S. state of Maryland, as well as the county seat of Anne Arundel County. It had a population of 38,394 at the 2010 census and is situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east of Washington, D.C. Annapolis is...

, Jerry Wright attended the Franciscan Coligio de La Salle in Malate, California, and Shadman's School at Scott's Circle in Washington, DC.

United States Naval Academy

Jerauld Wright received an appointment to the United States Naval AcademyUnited States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy is a four-year coeducational federal service academy located in Annapolis, Maryland, United States...

from Congressman

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

Edward W. Townsend

Edward W. Townsend

Edward Waterman Townsend was an American Democratic Party politician who represented New Jersey's 7th congressional district in the United States House of Representatives from 1911 to 1913, and the 10th district from 1913-1915, after redistricting following the United States Census,...

of the Tenth Congressional District

New Jersey's 10th congressional district

New Jersey's Tenth Congressional District is currently represented by Democrat Donald M. Payne.-Counties and municipalities in the district:For the 108th and successive Congresses , the district contains all or portions of 3 counties and 16 municipalities.Essex County:Hudson County:Union...

from the State of New Jersey

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Northeastern and Middle Atlantic regions of the United States. , its population was 8,791,894. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York, on the southeast and south by the Atlantic Ocean, on the west by Pennsylvania and on the southwest by Delaware...

. Wright entered the academy on July 31, 1914, the youngest midshipman to enter the academy since the American Civil War

American Civil War

The American Civil War was a civil war fought in the United States of America. In response to the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States, 11 southern slave states declared their secession from the United States and formed the Confederate States of America ; the other 25...

. Wright graduated on June 26, 1917 as part of the Class of 1918, ranked 92nd out of 193, the youngest member in his class.

World War I

In July 1917, Lt. Jerauld Wright joined the gunboat , which set sail for GibraltarGibraltar

Gibraltar is a British overseas territory located on the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula at the entrance of the Mediterranean. A peninsula with an area of , it has a northern border with Andalusia, Spain. The Rock of Gibraltar is the major landmark of the region...

on August 5, 1917 for anti-submarine patrol and convoy duty, operating as a unit of the Patrol Force through December 21, 1918.

Sea duty

La Spezia

La Spezia , at the head of the Gulf of La Spezia in the Liguria region of northern Italy, is the capital city of the province of La Spezia. Located between Genoa and Pisa on the Ligurian Sea, it is one of the main Italian military and commercial harbours and hosts one of Italy's biggest military...

, Venice

Venice

Venice is a city in northern Italy which is renowned for the beauty of its setting, its architecture and its artworks. It is the capital of the Veneto region...

, Trieste

Trieste

Trieste is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is situated towards the end of a narrow strip of land lying between the Adriatic Sea and Italy's border with Slovenia, which lies almost immediately south and east of the city...

, Spoleto

Spoleto

Spoleto is an ancient city in the Italian province of Perugia in east central Umbria on a foothill of the Apennines. It is S. of Trevi, N. of Terni, SE of Perugia; SE of Florence; and N of Rome.-History:...

, Corfu

Corfu

Corfu is a Greek island in the Ionian Sea. It is the second largest of the Ionian Islands, and, including its small satellite islands, forms the edge of the northwestern frontier of Greece. The island is part of the Corfu regional unit, and is administered as a single municipality. The...

, and Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

during a nine-month cruise of the Mediterranean

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

following the signing of the Armistice ending World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. Following Dyer's return August 1919, Wright supervised her overhaul at the Brooklyn Navy Yard

Brooklyn Navy Yard

The United States Navy Yard, New York–better known as the Brooklyn Navy Yard or the New York Naval Shipyard –was an American shipyard located in Brooklyn, northeast of the Battery on the East River in Wallabout Basin, a semicircular bend of the river across from Corlear's Hook in Manhattan...

. Lt. Wright also briefly commanded the , a , which escorted the presidential yacht , with President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

Warren G. Harding

Warren G. Harding

Warren Gamaliel Harding was the 29th President of the United States . A Republican from Ohio, Harding was an influential self-made newspaper publisher. He served in the Ohio Senate , as the 28th Lieutenant Governor of Ohio and as a U.S. Senator...

on board, from Gardiner's Bay, New York, to the Capes

Capes

Capes is a role-playing game by Tony Lower-Basch, independently published by Muse of Fire Games. It is a superhero-based role-playing game played in scenes, where players choose what character to play before each new scene. The game is a competitive storytelling game without a GM...

. In October 1920, Lt. Wright took command of the , anchored in reserve at Naval Station Newport

Naval Station Newport

The Naval Station Newport is a United States Navy base located in the towns of Newport and Middletown, Rhode Island. Naval Station Newport is home to the Naval War College and the Naval Justice School...

, Rhode Island

Newport, Rhode Island

Newport is a city on Aquidneck Island in Newport County, Rhode Island, United States, about south of Providence. Known as a New England summer resort and for the famous Newport Mansions, it is the home of Salve Regina University and Naval Station Newport which houses the United States Naval War...

, for transfer to Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the second largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. It was made the county seat of Charleston County in 1901 when Charleston County was founded. The city's original name was Charles Towne in 1670, and it moved to its present location from a location on the west bank of the...

. Later, in February 1922, Lt. Wright joined the , a slated for decommissioning

Ship decommissioning

To decommission a ship is to terminate her career in service in the armed forces of her nation. A somber occasion, it has little of the elaborate ceremony of ship commissioning, but carries significant tradition....

at the Mare Island Navy Yard, serving as its executive officer

Executive officer

An executive officer is generally a person responsible for running an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization.-Administrative law:...

.

In June 1922, Lt. Wright joined the , a , as its executive officer, with additional duties as fire control

Fire-control system

A fire-control system is a number of components working together, usually a gun data computer, a director, and radar, which is designed to assist a weapon system in hitting its target. It performs the same task as a human gunner firing a weapon, but attempts to do so faster and more...

officer and navigator

Navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation. The navigator's primary responsibility is to be aware of ship or aircraft position at all times. Responsibilities include planning the journey, advising the Captain or aircraft Commander of estimated timing to...

. John D. Ford set sail from the Philadelphia Navy Yard with its sister ships of Squadron 15, Division 3, for the U.S. Asiatic Fleet. The John D. Ford operated throughout the Far East

Far East

The Far East is an English term mostly describing East Asia and Southeast Asia, with South Asia sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.The term came into use in European geopolitical discourse in the 19th century,...

, including the South China Sea

South China Sea

The South China Sea is a marginal sea that is part of the Pacific Ocean, encompassing an area from the Singapore and Malacca Straits to the Strait of Taiwan of around...

, the Sea of Japan

Sea of Japan

The Sea of Japan is a marginal sea of the western Pacific Ocean, between the Asian mainland, the Japanese archipelago and Sakhalin. It is bordered by Japan, North Korea, Russia and South Korea. Like the Mediterranean Sea, it has almost no tides due to its nearly complete enclosure from the Pacific...

, and the Philippines

Philippines

The Philippines , officially known as the Republic of the Philippines , is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam...

, showing the flag and training with other destroyers in the fleet.

In July 1926, Lt. Wright joined the , a as the principal assistant of the ship's Gunnery Division. In November 1928, the Maryland took President-elect Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover was the 31st President of the United States . Hoover was originally a professional mining engineer and author. As the United States Secretary of Commerce in the 1920s under Presidents Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge, he promoted partnerships between government and business...

on the outbound leg of his goodwill tour of Latin America. Wright also further his hands-on education of gunnery and ordnance while serving as a instructor at the Gunnery School on the battleship . Commander Wright joined the , a attached to the Scouting Force

Scouting Fleet

The Scouting Fleet was part of the United States Fleet in the United States Navy, and renamed the Scouting Force in 1930.Established in 1922, the fleet consisted mainly of older battleships and initially operated in the Atlantic...

, as its first lieutenant in August 1931 and later became the ship's gunnery officer from June 1932 to June 1934. The Salt Lake City participated in naval exercises in the Atlantic and Pacific, underwent a major overhaul and participated in the 1934 Naval Review.

.jpg)

Shakedown cruise

Shakedown cruise is a nautical term in which the performance of a ship is tested. Shakedown cruises are also used to familiarize the ship's crew with operation of the craft....

, transitted the Panama Canal

Panama Canal

The Panama Canal is a ship canal in Panama that joins the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean and is a key conduit for international maritime trade. Built from 1904 to 1914, the canal has seen annual traffic rise from about 1,000 ships early on to 14,702 vessels measuring a total of 309.6...

, and joined the Destroyer Division 7 (DesRon 7) as its flagship

Flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, reflecting the custom of its commander, characteristically a flag officer, flying a distinguishing flag...

, becoming a unit of the Battle Force based at the San Diego Naval Base, California

San Diego, California

San Diego is the eighth-largest city in the United States and second-largest city in California. The city is located on the coast of the Pacific Ocean in Southern California, immediately adjacent to the Mexican border. The birthplace of California, San Diego is known for its mild year-round...

. The Blue participated in Fleet Problem XX exercises staged in the Caribbean Sea

Caribbean Sea

The Caribbean Sea is a sea of the Atlantic Ocean located in the tropics of the Western hemisphere. It is bounded by Mexico and Central America to the west and southwest, to the north by the Greater Antilles, and to the east by the Lesser Antilles....

.

Wright's final pre-war sea assignment was as the executive officer of the , a based at the Pearl Harbor Naval Base

Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor, known to Hawaiians as Puuloa, is a lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. Much of the harbor and surrounding lands is a United States Navy deep-water naval base. It is also the headquarters of the U.S. Pacific Fleet...

in the Territory of Hawaii

Territory of Hawaii

The Territory of Hawaii or Hawaii Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 7, 1898, until August 21, 1959, when its territory, with the exception of Johnston Atoll, was admitted to the Union as the fiftieth U.S. state, the State of Hawaii.The U.S...

, from March 1941 to May 1942. The Mississippi became a unit of Battleship Division 3 (BatDiv 3) with sister ships and . Following the Bismarck incident and the growing U-boat threat, Battleship Division 3 was secretly shifted to the newly-reconstituted U.S. Atlantic Fleet, under the command of Admiral Ernest J. King, entering the Norfolk Naval Base

Naval Station Norfolk

Naval Station Norfolk, in Norfolk, Virginia, is a base of the United States Navy, supporting naval forces in the United States Fleet Forces Command, those operating in the Atlantic Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, and Indian Ocean...

in June 1941. Mississippi was present at the Atlantic Conference at Argentia

Argentia, Newfoundland and Labrador

Argentia is a community on the island of Newfoundland in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It is situated on a flat headland located along the southwest coast of the Avalon Peninsula on Placentia Bay...

, participated in the Neutrality Patrol

Neutrality Patrol