British Army during World War I

Encyclopedia

| Timeline of the British Army British Army The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England... |

| 1700–1799 Time line of the British Army 1700 - 1799 The Time line of the British Army 1700–1799 lists the conflicts and wars the British Army were involved in.*War of the Spanish Succession 1701–1714*War of the Austrian Succession 1740*Seven Years' War 1754–1763... | 1800–1899 Time line of the British Army 1800 - 1899 The Time line of the British Army 1800–1899 lists the conflicts and wars the British Army were involved in.*French Revolutionary Wars ended 1802*Second Anglo-Maratha War 1802–1805*Napoleonic Wars 1802–1813... |1900–1999 Time line of the British Army 1900 - 1999 The Time line of the British Army 1900–1999 lists the conflicts and wars the British Army were involved in.*Boxer Rebellion ended 1901*Anglo-Aro War 1901–1902*Second Boer War ended 1902*World War I 1914–1918*Third Anglo Marri War 1917... | 2000 – present Time line of the British Army since 2000 The Time line of the British Army since 2000, lists the conflicts and wars the British Army were involved in.*Yugoslav wars ended 2001*Iraq War 2003–2008*War in Afghanistan 2001–present-See also:*Timeline of the British Army 1700–1799... |

The British Army during World War I fought the largest and most costly war in its long history. Unlike the French

French Army

The French Army, officially the Armée de Terre , is the land-based and largest component of the French Armed Forces.As of 2010, the army employs 123,100 regulars, 18,350 part-time reservists and 7,700 Legionnaires. All soldiers are professionals, following the suspension of conscription, voted in...

and German

German Army

The German Army is the land component of the armed forces of the Federal Republic of Germany. Following the disbanding of the Wehrmacht after World War II, it was re-established in 1955 as the Bundesheer, part of the newly formed West German Bundeswehr along with the Navy and the Air Force...

Armies, its units were made up exclusively of volunteers—as opposed to conscripts—at the beginning of the conflict. Furthermore, the British Army was considerably smaller than its French and German counterparts.

During the war, there were three distinct British Armies. The "first" army was the small volunteer force of 400,000 soldiers, over half of which were posted overseas to garrison the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

. This total included the Regular Army and reservists in the Territorial Force

Territorial Force

The Territorial Force was the volunteer reserve component of the British Army from 1908 to 1920, when it became the Territorial Army.-Origins:...

. Together, they formed the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), which was formed for service in France and became known as the Old Contemptibles. The 'second' army was Kitchener's Army

Kitchener's Army

The New Army, often referred to as Kitchener's Army or, disparagingly, Kitchener's Mob, was an all-volunteer army formed in the United Kingdom following the outbreak of hostilities in the First World War...

, formed from the volunteers in 1914–1915 destined to go into action at the Battle of the Somme. The 'third' was formed after the introduction of conscription

Conscription

Conscription is the compulsory enlistment of people in some sort of national service, most often military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and continues in some countries to the present day under various names...

in January 1916, and by the end of 1918, the army had reached its maximum strength of 4,000,000 men and could field over 70 divisions. The vast majority of the army fought in the main theatre of war on the Western Front

Western Front (World War I)

Following the outbreak of World War I in 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by first invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The tide of the advance was dramatically turned with the Battle of the Marne...

in France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and Belgium

Belgium

Belgium , officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a federal state in Western Europe. It is a founding member of the European Union and hosts the EU's headquarters, and those of several other major international organisations such as NATO.Belgium is also a member of, or affiliated to, many...

against the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

. Some units were engaged in Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

and Salonika against the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Bulgarian Army, while other units fought in the Middle East

Middle East

The Middle East is a region that encompasses Western Asia and Northern Africa. It is often used as a synonym for Near East, in opposition to Far East...

, Africa

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

and Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a toponym for the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran.Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Bronze Age Mesopotamia included Sumer and the...

—mainly against the Ottoman Empire

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman EmpireIt was usually referred to as the "Ottoman Empire", the "Turkish Empire", the "Ottoman Caliphate" or more commonly "Turkey" by its contemporaries...

—and one battalion fought alongside the Japanese Army

Imperial Japanese Army

-Foundation:During the Meiji Restoration, the military forces loyal to the Emperor were samurai drawn primarily from the loyalist feudal domains of Satsuma and Chōshū...

in China

China

Chinese civilization may refer to:* China for more general discussion of the country.* Chinese culture* Greater China, the transnational community of ethnic Chinese.* History of China* Sinosphere, the area historically affected by Chinese culture...

during the Siege of Tsingtao.

The war also posed problems for the army commanders, given that prior to 1914, the largest formation any serving General in the BEF had commanded on operations was a division

Division (military)

A division is a large military unit or formation usually consisting of between 10,000 and 20,000 soldiers. In most armies, a division is composed of several regiments or brigades, and in turn several divisions typically make up a corps...

. The expansion of the army saw some officers promoted from brigade

Brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that is typically composed of two to five battalions, plus supporting elements depending on the era and nationality of a given army and could be perceived as an enlarged/reinforced regiment...

to corps

Corps

A corps is either a large formation, or an administrative grouping of troops within an armed force with a common function such as Artillery or Signals representing an arm of service...

commander in less than a year. Army commanders also had to cope with the new tactics and weapons that were developed. With the move from manoeuvre to trench warfare, both the infantry and the artillery had to learn how to work together. During an offensive, and when in defence, they learned how to combine forces

Combined arms

Combined arms is an approach to warfare which seeks to integrate different branches of a military to achieve mutually complementary effects...

to defend the front line. Later in the war, when the Machine Gun Corps and the Tank Corps were added to the order of battle, they were also included in the new tactical doctrine.

The men at the front had to struggle with supply problems; the shortage of food and disease was rife in the damp, rat-infested conditions. Along with enemy action, many troops had to contend with new diseases: trench foot

Trench foot

Trench foot is a medical condition caused by prolonged exposure of the feet to damp, unsanitary, and cold conditions. It is one of many immersion foot syndromes...

, trench fever

Trench fever

Trench fever is a moderately serious disease transmitted by body lice. It infected armies in Flanders, France, Poland, Galicia, Italy, Salonika, Macedonia, Mesopotamia, and Egypt in World War I Trench fever (also known as "Five day fever", "Quintan fever" (febris Quintana in Latin), "Urban trench...

and trench nephritis

Nephritis

Nephritis is inflammation of the nephrons in the kidneys. The word "nephritis" was imported from Latin, which took it from Greek: νεφρίτιδα. The word comes from the Greek νεφρός - nephro- meaning "of the kidney" and -itis meaning "inflammation"....

. When the war ended in 1918, British Army casualties, as the result of enemy action and disease, were recorded as 673,375 dead and missing, with another 1,643,469 wounded. The rush to demobilise at the end of the war substantially decreased the strength of the army, from its peak of 4,000,000 men in 1918 to 370,000 men by 1920.

Organisation

The British Army during World War I could trace its organisation to the increasing demands of imperial expansion. The framework was the voluntary system of recruitment and the regimental system, which had been defined by the CardwellCardwell Reforms

The Cardwell Reforms refer to a series of reforms of the British Army undertaken by Secretary of State for War Edward Cardwell between 1868 and 1874.-Background:...

and Childers Reforms

Childers Reforms

The Childers Reforms restructured the infantry regiments of the British army. The reforms were undertaken by Secretary of State for War Hugh Childers in 1881, and were a continuation of the earlier Cardwell reforms....

of the late 19th century. The Army had been prepared and primarily called upon for Empire matters and the ensuing colonial wars. In the last years of the 19th century, the Army was involved in a major conflict, the Second Boer War

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War was fought from 11 October 1899 until 31 May 1902 between the British Empire and the Afrikaans-speaking Dutch settlers of two independent Boer republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State...

(1899–1902), which highlighted shortcomings in its tactics, leadership and administration. The 1904 Esher Report

Esher Report

The Esher Report of 1904, chaired by Lord Esher, recommended radical reform of the British Army, such as the creation of an Army Council, a General Staff and the abolition of the office of Commander-in-Chief of the Forces and the creation of a Chief of the General Staff, laid down the character of...

recommended radical reform, such as the creation of an Army Council, a General Staff, the abolition of the office of Commander-in-Chief of the Forces, and the creation of a Chief of the General Staff. The Haldane Reforms

Haldane Reforms

The Haldane Reforms were a series of far-ranging reforms of the British Army made from 1906 to 1912, and named after the Secretary of State for War, Richard Burdon Haldane...

of 1907 formally created an Expeditionary Force of seven divisions, reorganised the volunteers into a new Territorial Force

Territorial Force

The Territorial Force was the volunteer reserve component of the British Army from 1908 to 1920, when it became the Territorial Army.-Origins:...

of fourteen cavalry

Cavalry

Cavalry or horsemen were soldiers or warriors who fought mounted on horseback. Cavalry were historically the third oldest and the most mobile of the combat arms...

brigades and fourteen infantry

Infantry

Infantrymen are soldiers who are specifically trained for the role of fighting on foot to engage the enemy face to face and have historically borne the brunt of the casualties of combat in wars. As the oldest branch of combat arms, they are the backbone of armies...

divisions, and changed the old militia

Militia (United Kingdom)

The Militia of the United Kingdom were the military reserve forces of the United Kingdom after the Union in 1801 of the former Kingdom of Great Britain and Kingdom of Ireland....

into the Special Reserve to reinforce the expeditionary force.

At the outbreak of the war in August 1914, the British regular army was a small professional force. It consisted of 247,432 regular troops organised in four Guards

Brigade of Guards

The Brigade of Guards is a historical elite unit of the British Army, which has existed sporadically since the 17th century....

and 68 line infantry regiment

Regiment

A regiment is a major tactical military unit, composed of variable numbers of batteries, squadrons or battalions, commanded by a colonel or lieutenant colonel...

s, 31 cavalry regiments, artillery and other support arms. Each infantry regiment had two regular battalion

Battalion

A battalion is a military unit of around 300–1,200 soldiers usually consisting of between two and seven companies and typically commanded by either a Lieutenant Colonel or a Colonel...

s, one of which served at home and provided drafts and reinforcements to the other which was stationed overseas, while also being prepared to be part of the Expeditionary Force. Almost half of the regular army (74 of the 157 infantry battalions and 12 of the 31 cavalry regiments), was stationed overseas in garrisons throughout the British Empire

British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom. It originated with the overseas colonies and trading posts established by England in the late 16th and early 17th centuries. At its height, it was the...

. The Royal Flying Corps

Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps was the over-land air arm of the British military during most of the First World War. During the early part of the war, the RFC's responsibilities were centred on support of the British Army, via artillery co-operation and photographic reconnaissance...

was part of the Army until 1918. At the outbreak of the war, it consisted of 84 aircraft.

The regular Army was supported by the Territorial Force

Territorial Force

The Territorial Force was the volunteer reserve component of the British Army from 1908 to 1920, when it became the Territorial Army.-Origins:...

, and by reservists. In August 1914, there were three forms of reserves. The Army Reserve of retired soldiers was 145,350 strong. They were paid 3 Shilling

Shilling

The shilling is a unit of currency used in some current and former British Commonwealth countries. The word shilling comes from scilling, an accounting term that dates back to Anglo-Saxon times where it was deemed to be the value of a cow in Kent or a sheep elsewhere. The word is thought to derive...

s and 6 pence a week (17.5 pence) and had to attend 12 training days per year. The Special Reserve had another 64,000 men and was a form of part-time soldiering, similar to the Territorial Force. A Special Reservist had an initial six months full-time training and was paid the same as a regular soldier during this period; they had three or four weeks training per year thereafter. The National Reserve had some 215,000 men, who were on a register which was maintained by Territorial Force County Associations; these men had military experience, but no other reserve obligation.

The regulars and reserves—at least on paper—totalled a mobilised force of almost 700,000 men, although only 150,000 men were immediately available to be formed into the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) that was sent to the continent. This consisted of six infantry divisions and one of cavalry. By contrast, the French Army in 1914 mobilized 1,650,000 troops and 62 infantry divisions, while the German Army mobilized 1,850,000 troops and 87 infantry divisions.

Britain, therefore, began the war with six regular and 14 reserve divisions. During the war, a further six regular, 14 Territorial, 36 Kitchener's Army

Kitchener's Army

The New Army, often referred to as Kitchener's Army or, disparagingly, Kitchener's Mob, was an all-volunteer army formed in the United Kingdom following the outbreak of hostilities in the First World War...

and six other divisions, including the Naval Division from the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

were formed.

In 1914, each British infantry division consisted of three infantry brigades each of four battalions, with two machine gun

Machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic mounted or portable firearm, usually designed to fire rounds in quick succession from an ammunition belt or large-capacity magazine, typically at a rate of several hundred rounds per minute....

s per battalion, (24 in the division). They also had three field artillery

Artillery

Originally applied to any group of infantry primarily armed with projectile weapons, artillery has over time become limited in meaning to refer only to those engines of war that operate by projection of munitions far beyond the range of effect of personal weapons...

brigades with 54 18-pounder gun

Ordnance QF 18 pounder

The Ordnance QF 18 pounder, or simply 18-pounder Gun, was the standard British Army field gun of the World War I era. It formed the backbone of the Royal Field Artillery during the war, and was produced in large numbers. It was also used by British and Commonwealth Forces in all the main theatres,...

s, one field howitzer

Howitzer

A howitzer is a type of artillery piece characterized by a relatively short barrel and the use of comparatively small propellant charges to propel projectiles at relatively high trajectories, with a steep angle of descent...

brigade with eighteen 4.5 in (114.3 mm) howitzer

QF 4.5 inch Howitzer

The Ordnance QF 4.5 inch Howitzer was the standard British Empire field howitzer of the First World War era. It replaced the BL 5 inch Howitzer and equipped some 25% of the field artillery. It entered service in 1910 and remained in service through the interwar period and was last used in...

s, one heavy artillery battery with four 60-pounder guns, two engineer

Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually just called the Royal Engineers , and commonly known as the Sappers, is one of the corps of the British Army....

field companies, one signals company, one cavalry squadron, one cyclist company, three field ambulances, four Army Service Corps

Royal Army Service Corps

The Royal Army Service Corps was a corps of the British Army. It was responsible for land, coastal and lake transport; air despatch; supply of food, water, fuel, and general domestic stores such as clothing, furniture and stationery ; administration of...

horse-drawn transport companies and divisional headquarters support detachments.

The single cavalry division assigned to the BEF in 1914 consisted of 15 cavalry regiments in five brigades. They were armed with rifles, unlike their French and German counterparts, who were only armed with the shorter range carbine

Carbine

A carbine , from French carabine, is a longarm similar to but shorter than a rifle or musket. Many carbines are shortened versions of full rifles, firing the same ammunition at a lower velocity due to a shorter barrel length....

. The cavalry division also had a high allocation of artillery compared to foreign cavalry divisions, with 24 13-pounder gun

Ordnance QF 13 pounder

The Ordnance QF 13-pounder quick-firing field gun was the standard equipment of the British Royal Horse Artillery at the outbreak of World War I.-History:...

s organised into two brigades and two machine guns for each regiment. When dismounted, the cavalry division was the equivalent of two weakened infantry brigades with less artillery than the infantry division. By 1916, there were five cavalry divisions, each of three brigades, serving in France, the 1st, 2nd

2nd Cavalry Division (United Kingdom)

The 2nd Cavalry Division was a regular British Army division that saw service in World War I. It also known as Gough's Command, after its commanding General and was part of the initial British Expeditionary Force which landed in France in September 1914....

, 3rd divisions in the Cavalry Corps

Cavalry Corps (United Kingdom)

The Cavalry Corps was a formation of the British Army during World War I. and part of the British Expeditionary Force. The corps was formed in France in October 1914, under General Sir Edmund Allenby...

and the 1st

1st Indian Cavalry Division

The 1st Indian Cavalry Division was a regular division of the British Indian Army. The division sailed for France from Bombay on October 16, 1914 , under the command of Major General H D Fanshawe. The division was re designated the 4th Cavalry Division in November 1916. During the war the Division...

and 2nd Indian Cavalry Division

2nd Indian Cavalry Division

The 2nd Indian Cavalry Division was a regular division of the British Indian Army during World War I.-History:The division sailed for France from Bombay on October 16, 1914, under the command of Major General G A Cookson. During the war the division would serve in the trenches as infantry...

s in the Indian Cavalry Corps

Indian Cavalry Corps

The Indian Cavalry Corps was a formation of the British Indian Army in World War I. It was formed in France in December 1914. It remained in France until March 1916, when it was broken up....

, each brigade in the Indian cavalry corps contained a British cavalry regiment.

Over the course of the war, the composition of the infantry division gradually changed, and there was an increased emphasis upon providing the infantry divisions with organic fire support

Organic (military)

In military terminology, organic refers to a military unit that is a permanent part of a larger unit and provides some specialized capability to that parent unit...

. By 1918, a British division consisted of three infantry brigades, each of three battalions. Each of these battalions had 36 Lewis machine guns, making a total of 324 such weapons in the division. Additionally, there was a divisional machine gun battalion, equipped with 64 Vickers machine gun

Vickers machine gun

Not to be confused with the Vickers light machine gunThe Vickers machine gun or Vickers gun is a name primarily used to refer to the water-cooled .303 inch machine gun produced by Vickers Limited, originally for the British Army...

s in four companies of 16 guns. Each brigade in the division also had a mortar battery with eight Stokes Mortar

Stokes Mortar

The Stokes mortar was a British trench mortar invented by Sir Wilfred Stokes KBE which was issued to the British Army and the Commonwealth armies during the latter half of the First World War.-History:...

s. The artillery also changed the composition of its batteries. At the start of the war, there were three batteries with six guns per brigade; they then moved to four batteries with four guns per brigade, and finally in 1917, to four batteries with six guns per brigade to economise on battery commanders. In this way, the army would change drastically over the course of the war, reacting to the various developments, from the mobile war fought in the opening weeks to the static trench warfare of 1916 and 1917. The cavalry of the BEF represented 9.28% of the army; by July 1918, it would only represent 1.65%. The infantry would decrease from 64.64% in 1914 to 51.25% of the army in 1918, while the Royal Engineers would increase from 5.91% to 11.24% in 1918.

British Expeditionary Force

Entente Cordiale

The Entente Cordiale was a series of agreements signed on 8 April 1904 between the United Kingdom and the French Republic. Beyond the immediate concerns of colonial expansion addressed by the agreement, the signing of the Entente Cordiale marked the end of almost a millennium of intermittent...

, the British Army's role in a European war was to embark soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), which consisted of six infantry divisions and five cavalry brigades that were arranged into two Army corps: I Corps, under the command of Douglas Haig

Douglas Haig

Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig was a British soldier and senior commander during World War I.Douglas Haig may also refer to:* Club Atlético Douglas Haig, a football club from Argentina* Douglas Haig , American actor...

, and II Corps, under the command of Horace Smith-Dorrien

Horace Smith-Dorrien

General Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien GCB, GCMG, DSO, ADC was a British soldier and commander of the British II Corps and Second Army of the BEF during World War I.-Early life and career:...

. At the outset of the conflict, the British Indian Army

British Indian Army

The British Indian Army, officially simply the Indian Army, was the principal army of the British Raj in India before the partition of India in 1947...

was called upon for assistance; in August 1914, 20 percent of the 9,610 British officers initially sent to France were from the Indian army, while 16 percent of the 76,450 other ranks

Other Ranks

Other Ranks in the British Army, Royal Marines and Royal Air Force are those personnel who are not commissioned officers. In the Royal Navy, these personnel are called ratings...

came from the British Indian Army.

German Emperor Kaiser Wilhelm—who was famously dismissive of the BEF—issued an order on 19 August 1914 to "exterminate...the treacherous English and walk over General French's

John French, 1st Earl of Ypres

Field Marshal John Denton Pinkstone French, 1st Earl of Ypres, KP, GCB, OM, GCVO, KCMG, ADC, PC , known as The Viscount French between 1916 and 1922, was a British and Anglo-Irish officer...

contemptible little army". Hence, in later years, the survivors of the regular army dubbed themselves "The Old Contemptibles". By the end of 1914 (after the battles of Mons

Battle of Mons

The Battle of Mons was the first major action of the British Expeditionary Force in the First World War. It was a subsidiary action of the Battle of the Frontiers, in which the Allies clashed with Germany on the French borders. At Mons, the British army attempted to hold the line of the...

, Le Cateau

Battle of Le Cateau

The Battle of Le Cateau was fought on 26 August 1914, after the British, French and Belgians retreated from the Battle of Mons and had set up defensive positions in a fighting withdrawal against the German advance at Le Cateau-Cambrésis....

, the Aisne

First Battle of the Aisne

The First Battle of the Aisne was the Allied follow-up offensive against the right wing of the German First Army & Second Army as they retreated after the First Battle of the Marne earlier in September 1914...

and Ypres

First Battle of Ypres

The First Battle of Ypres, also called the First Battle of Flanders , was a First World War battle fought for the strategic town of Ypres in western Belgium...

), the old regular British Army had been virtually wiped out; although it managed to stop the German advance.

In October 1914, the 7th Division arrived in France, forming the basis of the British III Corps; the cavalry had grown into its own corps of three divisions. By December 1914, the BEF had expanded, fielding five army corps divided between the First and the Second Armies. As the Regular Army's strength declined, the numbers were made up— first by the Territorial Force, then by the volunteers of Field Marshal Kitchener's, New Army

Kitchener's Army

The New Army, often referred to as Kitchener's Army or, disparagingly, Kitchener's Mob, was an all-volunteer army formed in the United Kingdom following the outbreak of hostilities in the First World War...

. By the end of August 1914, he had raised six new divisions; by March 1915, the number of divisions had increased to 29. The Territorial Force was also expanded, raising second and third battalions and forming eight new divisions, which supplemented its peacetime strength of 14 divisions. The Third Army was formed in July 1915 and with the influx of troops from Kitchener's volunteers and further reorganization, the Fourth Army and the Reserve Army, which became the Fifth Army were formed in 1916.

Recruitment and conscription

In August 1914, 300,000 men had signed up to fight, and another 450,000 had joined-up by the end of September. Recruitment remained fairly steady through 1914 and early 1915, but it fell dramatically during the later years, especially after the Somme campaign, which resulted in 360,000 casualties. A prominent feature of the early months of volunteering was the formation of Pals battalionPals battalion

The Pals battalions of World War I were specially constituted units of the British Army comprising men who had enlisted together in local recruiting drives, with the promise that they would be able to serve alongside their friends, neighbours and work colleagues , rather than being arbitrarily...

s. Many of these pals who had lived and worked together, joined up and trained together and were allocated to the same units. The policy of drawing recruits from amongst the local population ensured that, when the Pals battalions suffered casualties, whole towns, villages, neighbourhoods and communities back in Britain were to suffer disproportionate losses. With the introduction of conscription in January 1916, no further Pals battalions were raised. Conscription

Conscription in the United Kingdom

Conscription in the United Kingdom has existed for two periods in modern times. The first was from 1916 to 1919, the second was from 1939 to 1960, with the last conscripted soldiers leaving the service in 1963...

for single men was introduced in January 1916. Four months later, in May 1916, it was extended to all men aged 18 to 41. The Military Service Act March 1916

Military Service Act (United Kingdom)

The Military Service Act 1916 was an Act passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom during the First World War. It was the first time that legislation had been passed in British military history introducing conscription...

specified that men from the ages of 18 to 41 were liable to be called up for service in the army, unless they were married (or widowed with children), or served in one of a number of reserved occupation

Reserved occupation

A reserved occupation is an occupation considered important enough to a country that those serving in such occupations are exempt - in fact forbidden - from military service....

s, which were usually industrial but which also included clergymen and teachers. This legislation did not apply to Ireland, despite its then status as part of the United Kingdom (but see Conscription Crisis of 1918). By January 1916, when conscription was introduced, 2.6 million men had volunteered for service, a further 2.3 million were conscripted before the end of the war; by the end of 1918, the army had reached its peak strength of four million men.

Women also volunteered and served in a non-combatant role; by the end of the war, 80,000 had enlisted. They mostly served as nurses in the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (QAIMNS), the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry

First Aid Nursing Yeomanry

The First Aid Nursing Yeomanry is a British independent all-female unit and registered charity affiliated to, but not part of, the Territorial Army, formed in 1907 and active in both nursing and intelligence work during the World Wars.-Formation:It was formed as the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry in...

(FANY), the Voluntary Aid Detachment

Voluntary Aid Detachment

The Voluntary Aid Detachment was a voluntary organisation providing field nursing services, mainly in hospitals, in the United Kingdom and various other countries in the British Empire. The organisation's most important periods of operation were during World War I and World War II.The...

(VAD); and from 1917, in the Army when the Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), was founded. The WAAC was divided into four sections: cookery; mechanical; clerical and miscellaneous. Most stayed on the Home Front, but around 9,000 served in France.

Commanders

John French, 1st Earl of Ypres

Field Marshal John Denton Pinkstone French, 1st Earl of Ypres, KP, GCB, OM, GCVO, KCMG, ADC, PC , known as The Viscount French between 1916 and 1922, was a British and Anglo-Irish officer...

. His last active command had been the cavalry division in the Second Boer War.

French had remarked in 1912 that Douglas Haig

Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, KT, GCB, OM, GCVO, KCIE, ADC, was a British senior officer during World War I. He commanded the British Expeditionary Force from 1915 to the end of the War...

—the commander of the British I Corps—would be better suited to a position on the staff than a field command. Like French, Haig was a cavalryman, his last active command had been a brigade in the cavalry division during the Second Boer War. The first commander of the British II Corps was Lieutenant General James Grierson

James Grierson

Lieutenant General Sir James Moncrieff Grierson KCB, CMG, CVO, ADC was a British soldier.- Military career :Grierson was commissioned into the Royal Artillery in 1877....

, a noted tactician who died of a heart attack soon after arriving in France. French wished to appoint Lieutenant General Herbert Plumer

Herbert Plumer, 1st Viscount Plumer

Field Marshal Herbert Charles Onslow Plumer, 1st Viscount Plumer, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE was a British colonial official and soldier born in Torquay who commanded the British Second Army in World War I and later served as High Commissioner of the British Mandate for Palestine.-Military...

in his place, but against French's wishes, Kitchener instead appointed Lieutenant General Horace Smith-Dorrien

Horace Smith-Dorrien

General Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien GCB, GCMG, DSO, ADC was a British soldier and commander of the British II Corps and Second Army of the BEF during World War I.-Early life and career:...

, who had begun his military career in the Zulu War in 1879 and was one of only five officers to survive the battle of Isandlwana

Battle of Isandlwana

The Battle of Isandlwana on 22 January 1879 was the first major encounter in the Anglo-Zulu War between the British Empire and the Zulu Kingdom...

. He had built a formidable reputation as an infantry commander during the Sudan Campaign and the Second Boer War. After the Second Boer War, he was responsible for a number of reforms, notably forcing an increase in dismounted training for the cavalry. This was met with hostility by French (as a cavalryman). By 1914, French's dislike for Smith-Dorrien was well known within the army.

French was eventually replaced by Haig in 1915, who commanded the BEF for the remainder of the war. He became most famous for his role as its commander during the battle of the Somme

Battle of the Somme (1916)

The Battle of the Somme , also known as the Somme Offensive, took place during the First World War between 1 July and 14 November 1916 in the Somme department of France, on both banks of the river of the same name...

, the battle of Passchendaele, and the Hundred Days Offensive

Hundred Days Offensive

The Hundred Days Offensive was the final period of the First World War, during which the Allies launched a series of offensives against the Central Powers on the Western Front from 8 August to 11 November 1918, beginning with the Battle of Amiens. The offensive forced the German armies to retreat...

—the series of victories leading to the German surrender in 1918. Haig was succeeded in command of the First Army

British First Army

The First Army was a field army of the British Army that existed during the First and Second World Wars. Despite being a British command, the First Army also included Indian and Portuguese forces during the First World War and American and French during the Second World War.-First World War:The...

by General Charles Carmichael Monro

Charles Carmichael Monro

General Sir Charles Carmichael Monro, 1st Baronet of Bearcrofts, GCB, GCSI, GCMG, was a British Army General during World War I and Governor of Gibraltar from 1923 to 1929.-Military career:...

, who in turn was succeeded by General Henry Horne

Henry Horne, 1st Baron Horne

General Henry Sinclair Horne, 1st Baron Horne GCB, KCMG was a military officer in the British Army, most notable for his generalship during World War I. He was the only British artillery officer to command an army in the war. Until recently Horne was the unknown General of the Great War and did...

in September 1916, the only officer with an artillery background to command a British army during the war.

General Plumer was eventually appointed to command II Corps, in December 1914, he succeeded Smith-Dorrien in command of the Second Army

British Second Army

The British Second Army was active during both the First and Second World Wars. During the First World War the army was active on the Western Front and in Italy...

in 1915. He had commanded a mounted infantry detachment in the Second Boer war, where he started to build his reputation. He held command of the Ypres salient for three years and gained an overwhelming victory over the German Army at the battle of Messines

Battle of Messines

The Battle of Messines was a battle of the Western front of the First World War. It began on 7 June 1917 when the British Second Army under the command of General Herbert Plumer launched an offensive near the village of Mesen in West Flanders, Belgium...

in 1917. Plumer is generally recognised as one of the most effective of the senior British commanders on the Western Front.

Edmund Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby

Field Marshal Edmund Henry Hynman Allenby, 1st Viscount Allenby GCB, GCMG, GCVO was a British soldier and administrator most famous for his role during the First World War, in which he led the Egyptian Expeditionary Force in the conquest of Palestine and Syria in 1917 and 1918.Allenby, nicknamed...

commanded the Third Army on the western front. He had previously served in the Zulu War, the Sudan campaign, and the Second Boer war. He was commander of the cavalry division on the western front, where his leadership was noted during the retreat from Mons and the first battle of Ypres

First Battle of Ypres

The First Battle of Ypres, also called the First Battle of Flanders , was a First World War battle fought for the strategic town of Ypres in western Belgium...

. In 1917, he was given command of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force

Egyptian Expeditionary Force

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force was formed in March 1916 to command the British and British Empire military forces in Egypt during World War I. Originally known as the 'Force in Egypt' it had been commanded by General Maxwell who was recalled to England...

, where he oversaw the conquest of Palestine

Palestine

Palestine is a conventional name, among others, used to describe the geographic region between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, and various adjoining lands....

and Syria

Syria

Syria , officially the Syrian Arab Republic , is a country in Western Asia, bordering Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the West, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Israel to the southwest....

in 1917 and 1918. Allenby replaced Archibald Murray

Archibald Murray

General Sir Archibald James Murray, GCMG, KCB, CVO, DSO was a British Army officer during World War I, most famous for his commanding the Egyptian Expeditionary Force from 1916 to 1917.-Army career:...

, who had been the Chief of Staff of the British Expeditionary Force in France in 1914.

Allenby was replaced as Third Army commander by General Julian Byng

Julian Byng, 1st Viscount Byng of Vimy

Field Marshal Julian Hedworth George Byng, 1st Viscount Byng of Vimy was a British Army officer who served as Governor General of Canada, the 12th since Canadian Confederation....

, who began the war as commander of the 3rd Cavalry Division. After performing well during the First Battle of Ypres, he was given command of the Cavalry Corps. He was sent to the Dardenelles in August 1915, to command the British IX Corps. Byng planned the highly successful evacuation of 105,000 Allied troops and the majority of the equipment of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force

Mediterranean Expeditionary Force

The Mediterranean Expeditionary Force was part of the British Army during World War I, that commanded all Allied forces at Gallipoli and Salonika. This included the initial naval operation to force the straits of the Dardanelles. Its headquarters was formed in March 1915...

(MEF). The withdrawal was successfully completed in January 1916, without the loss of a single man. Byng had already returned to the western front, where he was given command of the Canadian Corps

Canadian Corps

The Canadian Corps was a World War I corps formed from the Canadian Expeditionary Force in September 1915 after the arrival of the 2nd Canadian Division in France. The corps was expanded by the addition of the 3rd Canadian Division in December 1915 and the 4th Canadian Division in August 1916...

. His most notable battle was the battle of Vimy ridge

Battle of Vimy Ridge

The Battle of Vimy Ridge was a military engagement fought primarily as part of the Battle of Arras, in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais region of France, during the First World War. The main combatants were the Canadian Corps, of four divisions, against three divisions of the German Sixth Army...

in April 1917, which was carried out by the Canadian Corps with British support.

General Henry Rawlinson

Henry Rawlinson, 1st Baron Rawlinson

General Henry Seymour Rawlinson, 1st Baron Rawlinson, GCB, GCSI, GCVO, KCMG , known as Sir Henry Rawlinson, Bt between 1895 and 1919, was a British First World War general most famous for his roles in the Battle of the Somme of 1916 and the Battle of Amiens in 1918.-Military career:Rawlinson was...

served on Kitchener's staff during the advance on Omdurman

Battle of Omdurman

At the Battle of Omdurman , an army commanded by the British Gen. Sir Herbert Kitchener defeated the army of Abdullah al-Taashi, the successor to the self-proclaimed Mahdi Muhammad Ahmad...

, in 1898, and served with distinction in the Second Boer War, where he earned a reputation as one of the most able British commanders. Rawlinson took command of the British IV Corps in 1915 and then command of the Fourth Army

British Fourth Army

The Fourth Army was a field army that formed part of the British Expeditionary Force during the First World War. The Fourth Army was formed on 5 February 1916 under the command of General Sir Henry Rawlinson to carry out the main British contribution to the Battle of the Somme.-History:The Fourth...

in 1916, as the plans for the Allied offensive on the Somme

Somme

Somme is a department of France, located in the north of the country and named after the Somme river. It is part of the Picardy region of France....

were being developed. During the war, Rawlinson was noted for his willingness to use innovative tactics

Military tactics

Military tactics, the science and art of organizing an army or an air force, are the techniques for using weapons or military units in combination for engaging and defeating an enemy in battle. Changes in philosophy and technology over time have been reflected in changes to military tactics. In...

—which he employed during the battle of Amiens—where he combined attacks by tanks with artillery.

General Hubert Gough

Hubert Gough

General Sir Hubert de la Poer Gough GCB, GCMG, KCVO was a senior officer in the British Army, who commanded the British Fifth Army from 1916 to 1918 during the First World War.-Family background:...

commanded a mounted infantry regiment with distinction during the relief of Ladysmith

Relief of Ladysmith

When the Second Boer War broke out on 11 October 1899, the Boers had a numeric superiority within Southern Africa. They quickly invaded the British territory and laid siege to Ladysmith, Kimberley and Mafeking...

, but his command was destroyed while attacking a larger Boer force in 1901. When he joined the BEF, he was in command of the 3rd Cavalry Brigade, and was promoted from a brigade to a corps command in less than a year. In September 1914, he was given command of the 2nd Cavalry Division

2nd Cavalry Division (United Kingdom)

The 2nd Cavalry Division was a regular British Army division that saw service in World War I. It also known as Gough's Command, after its commanding General and was part of the initial British Expeditionary Force which landed in France in September 1914....

; in April 1915, the 7th Division; and in July 1915, the British I Corps which he commanded during the battle of Loos

Battle of Loos

The Battle of Loos was one of the major British offensives mounted on the Western Front in 1915 during World War I. It marked the first time the British used poison gas during the war, and is also famous for the fact that it witnessed the first large-scale use of 'new' or Kitchener's Army...

. In May 1916, he was appointed commander of the Fifth Army, which suffered heavy losses at the battle of Passchendaele. The collapse of the Fifth Army was widely viewed as the reason for the German breakthrough in the Spring Offensive

Spring Offensive

The 1918 Spring Offensive or Kaiserschlacht , also known as the Ludendorff Offensive, was a series of German attacks along the Western Front during World War I, beginning on 21 March 1918, which marked the deepest advances by either side since 1914...

, and Gough was dismissed as its commander in March 1918, being succeeded by General William Birdwood

William Birdwood, 1st Baron Birdwood

Field Marshal William Riddell Birdwood, 1st Baron Birdwood, GCB, GCSI, GCMG, GCVO, GBE, CIE, DSO was a First World War British general who is best known as the commander of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps during the Gallipoli Campaign in 1915.- Youth and early career :Birdwood was born...

for the last months of the war. Birdwood had previously commanded the Australian Corps

Australian Corps

The Australian Corps was a World War I army corps that contained all five Australian infantry divisions serving on the Western Front. It was the largest corps fielded by the British Empire army in France...

, an appointment requiring a combination of tact and tactical flair.

On the Macedonian front

Macedonian front (World War I)

The Macedonian Front resulted from an attempt by the Allied Powers to aid Serbia, in the autumn of 1915, against the combined attack of Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria. The expedition came too late and in insufficient force to prevent the fall of Serbia, and was complicated by the internal...

, General George Milne

George Milne, 1st Baron Milne

Field Marshal George Francis Milne, 1st Baron Milne, GCB, GCMG, DSO , was a British military commander who served as Chief of the Imperial General Staff from 1926 to 1933.-Army career:...

commanded the British Salonika Army

British Salonika Army

The British Salonika Army was a British field army of the British Army during World War I.-First World War:The Army was formed in Salonika in May 1916 under Lieutenant General George Milne to oppose Bulgarian advances in the region as part of the Macedonian front...

, and General Ian Hamilton

Ian Standish Monteith Hamilton

General Sir Ian Standish Monteith Hamilton GCB GCMG DSO TD was a general in the British Army and is most notably for commanding the ill-fated Mediterranean Expeditionary Force during the Battle of Gallipoli....

commanded the ill-fated MEF during the Gallipoli Campaign. He had previously seen service in the First Boer War

First Boer War

The First Boer War also known as the First Anglo-Boer War or the Transvaal War, was fought from 16 December 1880 until 23 March 1881-1877 annexation:...

, the Sudan campaign, and the Second Boer War.

Back in Britain, the professional commander of the British Army—or Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS)—was General James Murray, who retained that post during the early years of the war. He was replaced as CIGS in 1916 by General William Robertson. A strong supporter of Haig, Robertson was replaced in 1918, by General Henry Hughes Wilson.

Officer selection

In August 1914, there were 28,060 officers in the British Army, of which 12,738 were regular officers, the rest were in the reserves. The number of officers in the army had increased to 164,255 by November 1918. These were survivors among the 247,061 officers who had been granted a commission during the war.Most pre-war officers came from families with military connections, the gentry

Gentry

Gentry denotes "well-born and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past....

or the peerage

Peerage

The Peerage is a legal system of largely hereditary titles in the United Kingdom, which constitute the ranks of British nobility and is part of the British honours system...

; a public school

Public School (UK)

A public school, in common British usage, is a school that is neither administered nor financed by the state or from taxpayer contributions, and is instead funded by a combination of endowments, tuition fees and charitable contributions, usually existing as a non profit-making charitable trust...

education was almost essential. In 1913, about 2% of regular officers had been promoted from the ranks. The officer corps, during the war, consisted of regular officers from the peacetime army, officers who had been granted permanent commissions during the war, officers who had been granted temporary commissions for the duration of the war, territorial army officers commissioned during peacetime, officers commissioned from the ranks of the pre-war regular and territorial army and temporary officers commissioned from the ranks for the duration of the war alone.

In September 1914, Lord Kitchener announced that he was looking for volunteers and regular NCOs to provide officers for the expanding army. Most of the volunteers came from the middle class

Middle class

The middle class is any class of people in the middle of a societal hierarchy. In Weberian socio-economic terms, the middle class is the broad group of people in contemporary society who fall socio-economically between the working class and upper class....

, with the largest group from commercial and clerical occupations (27%), followed by teachers and students (18%) and professional men (15%). In March 1915, it was discovered that 12,290 men serving in the ranks had been members of a university or public school Officers' Training Corps (OTC). Most applied for—and were granted—commissions, while others who did not apply were also commissioned. At the end of 1915, the army introduced a new system for recruiting officers that guaranteed that the vast majority had served in the ranks.

Once a candidate was selected as an officer, promotion could be rapid. A. S. Smeltzer—after serving in the Regular Army for 15 years—was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant

Second Lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces.- United Kingdom and Commonwealth :The rank second lieutenant was introduced throughout the British Army in 1871 to replace the rank of ensign , although it had long been used in the Royal Artillery, Royal...

in 1915. He rose in rank, and by the Spring of 1917 had been promoted to Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel

Lieutenant colonel is a rank of commissioned officer in the armies and most marine forces and some air forces of the world, typically ranking above a major and below a colonel. The rank of lieutenant colonel is often shortened to simply "colonel" in conversation and in unofficial correspondence...

and was commanding officer of the 6th Battalion, The Buffs (Royal East Kent Regiment).

Along with rapid promotion, the war also noticeably lowered the age of battalion commanding officers. In 1914, they were aged over 50, while the average age for a battalion commanding officer in the BEF, between 1917 and 1918, was 28. By this stage, it was official policy that men over 35 were no longer eligible to command battalions. This trend was reflected amongst the junior officers. Anthony Eden

Anthony Eden

Robert Anthony Eden, 1st Earl of Avon, KG, MC, PC was a British Conservative politician, who was Prime Minister from 1955 to 1957...

was the Adjutant

Adjutant

Adjutant is a military rank or appointment. In some armies, including most English-speaking ones, it is an officer who assists a more senior officer, while in other armies, especially Francophone ones, it is an NCO , normally corresponding roughly to a Staff Sergeant or Warrant Officer.An Adjutant...

of a battalion when aged 18, and served as the Brigade Major

Brigade Major

In the British Army, a Brigade Major was the Chief of Staff of a brigade. He held the rank of Major and was head of the brigade's "G - Operations and Intelligence" section directly and oversaw the two other branches, "A - Administration" and "Q - Quartermaster"...

in the 198th Brigade

66th (2nd East Lancashire) Division

The British 66th Division was raised as a second-line Territorial Force division in August 1914 shortly after the commencement of the First World War. It went on to serve as a full-fledged frontline division on the Western Front in 1917 and 1918...

while still only aged 20.

The war also provided opportunities for advancement onto the General Staff, especially in the early days, when many former senior officers were recalled from retirement. Some of these were found wanting, due to their advanced age, their unwillingness to serve, or a lack of competence and fitness; most were sent back into retirement before the first year of the war was over, leaving a gap that had to be filled by lower-ranking officers. Criticism of the quality of staff work in the Crimean War and the Second Boer War had led to sweeping changes under Haldane. The Staff College, Camberley

Staff College, Camberley

Staff College, Camberley, Surrey, was a staff college for the British Army from 1802 to 1997, with periods of closure during major wars. In 1997 it was merged into the new Joint Services Command and Staff College.-Origins:...

was greatly expanded and Lord Kitchener established another staff college at Quetta

Command and Staff College

The Command and Staff College was established in 1907 at Quetta, Balochistan, British Raj, now in Pakistan, and is the oldest and the most prestigious institution of the Pakistan Army. It was established in 1905 in Deolali and moved to its present location at Quetta in 1907 under the name of Quetta...

in 1904. Nonetheless, when war broke out in August 1914, there were barely enough graduates to staff the BEF. Four-month-long staff courses were introduced, and filled with regimental officers who, upon completing their training, were posted to various headquarters. As a result, staff work was again poor, until training and experience slowly remedied the situation. In 1918, staff officers who had been trained exclusively for static trench warfare were forced to adapt to the demands of semi-open warfare.

During the course of the war, 78 British and Dominion

Dominion

A dominion, often Dominion, refers to one of a group of autonomous polities that were nominally under British sovereignty, constituting the British Empire and British Commonwealth, beginning in the latter part of the 19th century. They have included Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Newfoundland,...

officers of the rank of Brigadier-General

Brigadier General

Brigadier general is a senior rank in the armed forces. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries, usually sitting between the ranks of colonel and major general. When appointed to a field command, a brigadier general is typically in command of a brigade consisting of around 4,000...

and above were killed or died during active service, while another 146 were wounded, gassed, or captured.

Doctrine

British official historian Brigadier James Edward EdmondsJames Edward Edmonds

Brigadier General James Edward Edmonds CB, CMG was a British First World War officer of the Royal Engineers who in the role of British official historian was responsible for the post-war compilation of the 28-volume History of the Great War...

recorded in 1925 that "The British Army of 1914 was the best trained, best equipped and best organized British Army ever sent to war". This was in part due to the Haldane reforms

Haldane Reforms

The Haldane Reforms were a series of far-ranging reforms of the British Army made from 1906 to 1912, and named after the Secretary of State for War, Richard Burdon Haldane...

, and the Army itself recognising the need for change and training. Training began with individual training in winter, followed by squadron, company or battery training in spring; regimental, battalion and brigade training in summer; and division or inter-divisional exercises and army manoeuvres in late summer and autumn. The common doctrine of headquarters at all levels was outlined in the Field Service Pocket Book, which Haig had introduced while serving as Director of Staff Studies at the War Office in 1906.

The Second Boer War had alerted the army to the dangers posed by fire zones that were covered by long-range, magazine-fed rifles. In the place of volley firing and frontal attacks, there was a greater emphasis on advancing in extended order, the use of available cover, the use of artillery to support the attack, flank and converging attacks and fire and movement. The Army expected units to advance as far as possible in a firing line without opening fire, both to conceal their positions and conserve ammunition, then to attack in successive waves, closing with the enemy decisively.

The cavalry practised reconnaissance and fighting dismounted more regularly, and in January 1910, the decision was made at the General Staff Conference that dismounted cavalry should be taught infantry tactics in attack and defence. They were the only cavalry from a major European power trained for both the mounted cavalry charge and dismounted action, and equipped with the same rifles as the infantry, rather than short-range carbines. The cavalry were also issued with entrenching tool

Entrenching tool

An entrenching tool or E-tool is a collapsible spade used by military forces for a variety of military purposes. Survivalists, freedivers, campers, hikers and other outdoors groups have found it to be indispensable in field use...

s prior to the outbreak of war, as a result of experience gained during the Second Boer War.

The infantry's marksmanship, and fire and movement techniques, had been inspired by Boer tactics and was established as formal doctrine by Colonel Charles Monro

Sir Charles Monro, 1st Baronet

General Sir Charles Carmichael Monro, 1st Baronet of Bearcrofts, GCB, GCSI, GCMG, was a British Army General during World War I and Governor of Gibraltar from 1923 to 1929.-Military career:...

when he was in charge of the School of Musketry at Shorncliffe

Shorncliffe Redoubt

Shorncliffe Redoubt is a British Napoleonic earthwork fort of great historic importance, as it is the birthplace of modern light infantry tactics...

. In 1914, British rifle fire was so effective that there were some reports to the effect that the Germans believed they were facing huge numbers of machine guns. The Army concentrated on rifle practice, with days spent on the ranges dedicated to improving marksmanship and obtaining a rate of fire of 15 effective rounds a minute at 300 yd (274.3 m); one sergeant set a record of 38 rounds into a 12 in (304.8 mm) target set at 300 yd (274.3 m) in 30 seconds. In their 1914 skill-at-arms meeting, the 1st Battalion Black Watch

Black Watch

The Black Watch, 3rd Battalion, Royal Regiment of Scotland is an infantry battalion of the Royal Regiment of Scotland. The unit's traditional colours were retired in 2011 in a ceremony led by Queen Elizabeth II....

recorded 184 marksmen, 263 first-class shots, 89 second-class shots and four third-class shots, at ranges from 300–600 yd (274.3–548.6 m). The infantry also practised squad and section attacks and fire from cover, often without orders from officers or NCOs

Non-commissioned officer

A non-commissioned officer , called a sub-officer in some countries, is a military officer who has not been given a commission...

, so that soldiers would be able to act on their own initiative. In the last exercise before the war, it was noted that the infantry made wonderful use of ground, advances in short rushes and always at the double and almost invariably fires from a prone position.

Weapons

The British Army was armed with the Short Magazine Lee-Enfield Mk IIILee-Enfield

The Lee-Enfield bolt-action, magazine-fed, repeating rifle was the main firearm used by the military forces of the British Empire and Commonwealth during the first half of the 20th century...

(SMLE Mk III), which featured a bolt-action and large magazine

Magazine (firearm)

A magazine is an ammunition storage and feeding device within or attached to a repeating firearm. Magazines may be integral to the firearm or removable . The magazine functions by moving the cartridges stored in the magazine into a position where they may be loaded into the chamber by the action...

capacity that enabled a trained rifleman to fire 20-30 aimed rounds a minute. World War I accounts tell of British troops repelling German attackers, who subsequently reported that they had encountered machine guns, when in fact, it was simply a group of trained riflemen armed with SMLEs. The heavy Vickers machine gun

Vickers machine gun

Not to be confused with the Vickers light machine gunThe Vickers machine gun or Vickers gun is a name primarily used to refer to the water-cooled .303 inch machine gun produced by Vickers Limited, originally for the British Army...

proved itself to be the most reliable weapon on the battlefield, with some of its feats of endurance entering military mythology. One account tells of the action by the 100th Company of the Machine Gun Corps at High Wood

High Wood

High Wood is a small forest near Bazentin le Petit in the Somme département of northern France which was the scene of intense fighting for two months from 14 July to 15 September 1916 during the Battle of the Somme.-Background:...

on 24 August 1916. This company had 10 Vickers guns; it was ordered to give sustained covering fire for 12 hours onto a selected area 2000 yd (1,828.8 m) away, in order to prevent German troops forming up there for a counter attack whilst a British attack was in progress. Two companies of infantry were allocated as ammunition, rations and water carriers for the gunners. Two men worked a belt–filling machine non–stop for 12 hours, keeping up a supply of 250-round belts. They used 100 new barrels and all of the water—including the men’s drinking water and the contents of the latrine

Latrine

A latrine is a communal facility containing one or more commonly many toilets which may be simple pit toilets or in the case of the United States Armed Forces any toilet including modern flush toilets...

buckets—to keep the guns cool. In that 12-hour period, the 10 guns fired just short of one million rounds between them. One team is reported to have fired 120,000. At the close of the operation, it is alleged that every gun was working perfectly and that not one had broken down during the whole period.

The lighter Lewis gun

Lewis Gun

The Lewis Gun is a World War I–era light machine gun of American design that was perfected and widely used by the British Empire. It was first used in combat in World War I, and continued in service with a number of armed forces through to the end of the Korean War...

was adopted for land and aircraft use in October 1915. The Lewis gun had the advantage of being about 80% faster to build than the Vickers, and far more portable. By the end of World War I, over 50,000 Lewis Guns had been produced; they were nearly ubiquitous on the Western Front, outnumbering the Vickers gun by a ratio of about 3:1.

The Stokes Mortar

Stokes Mortar

The Stokes mortar was a British trench mortar invented by Sir Wilfred Stokes KBE which was issued to the British Army and the Commonwealth armies during the latter half of the First World War.-History:...

was rapidly developed when it became clear that some type of weapon was needed to provide artillery-like fire support to the infantry. The weapon was fully man-transportable yet also capable of firing reasonably powerful shells at targets beyond the range of rifle grenades.

Finally, the Mark I tank—a British invention—was seen as the solution to the stalemate of trench warfare. The Mark I had a range of 23 mi (37 km) without refuellingl, and a speed of 3 mph (4.8 km/h); it first saw service on the Somme in September 1916.

Infantry tactics

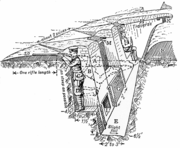

Trench warfare

Trench warfare is a form of occupied fighting lines, consisting largely of trenches, in which troops are largely immune to the enemy's small arms fire and are substantially sheltered from artillery...

, a development for which the British Army had not prepared. Expecting an offensive mobile war, the Army had not instructed the troops in defensive tactics and had failed to obtain stocks of barbed wire

Barbed wire

Barbed wire, also known as barb wire , is a type of fencing wire constructed with sharp edges or points arranged at intervals along the strand. It is used to construct inexpensive fences and is used atop walls surrounding secured property...

, hand grenades, or trench mortars

Mortar (weapon)

A mortar is an indirect fire weapon that fires explosive projectiles known as bombs at low velocities, short ranges, and high-arcing ballistic trajectories. It is typically muzzle-loading and has a barrel length less than 15 times its caliber....

. In the early years of trench warfare, the normal infantry attack formation was based on the battalion, which comprised four companies

Company (military unit)

A company is a military unit, typically consisting of 80–225 soldiers and usually commanded by a Captain, Major or Commandant. Most companies are formed of three to five platoons although the exact number may vary by country, unit type, and structure...

that were each made up of four platoon

Platoon

A platoon is a military unit typically composed of two to four sections or squads and containing 16 to 50 soldiers. Platoons are organized into a company, which typically consists of three, four or five platoons. A platoon is typically the smallest military unit led by a commissioned officer—the...

s. The battalion would form 10 waves with 100 yd (91.4 m) between each, while each company formed two waves of two platoons. The first six waves were the fighting elements from three of the battalions' companies, the seventh contained the battalion headquarters; the remaining company formed the eighth and ninth waves, which were expected to carry equipment forward, the tenth wave contained the stretcher bearers and medics. The formation was expected to move forward at a rate of 100 yd (91.4 m) every two minutes, even though each man carried his rifle, bayonet

Bayonet

A bayonet is a knife, dagger, sword, or spike-shaped weapon designed to fit in, on, over or underneath the muzzle of a rifle, musket or similar weapon, effectively turning the gun into a spear...

, gas mask, ammunition, two hand grenades, wire cutters, a spade, two empty sandbag

Sandbag

A sandbag is a sack made of hessian/burlap, polypropylene or other materials that is filled with sand or soil and used for such purposes as flood control, military fortification, shielding glass windows in war zones and ballast....

s and flares

Flare (pyrotechnic)

A flare, also sometimes called a fusee, is a type of pyrotechnic that produces a brilliant light or intense heat without an explosion. Flares are used for signalling, illumination, or defensive countermeasures in civilian and military applications...

. The carrying platoons, in addition to the above, also carried extra ammunition, barbed wire and construction materials to effect repairs to captured lines and fortifications.

By 1918, experience had led to a change in tactics; the infantry no longer advanced in rigid lines, but formed a series of flexible waves. They would move covertly, under the cover of darkness, and occupy shell holes or other cover near the German line. Skirmishers formed the first wave and followed the creeping barrage into the German front line to hunt out points of resistance. The second or main wave followed in platoons or sections in single file. The third was formed from small groups of reinforcements, the fourth wave was expected to defend the captured territory. All waves were expected to take advantage of the ground during the advance. (see below for when operating with tanks)

Each platoon now had a Lewis gun section and a section that specialised in throwing hand-grenades (then known as bombs), each section was compelled to provide two scouts to carry out reconnaissance duties. Each platoon was expected to provide mutual fire support in the attack they were to advance, without halting; but leap frogging

Leapfrogging (infantry)

In infantry tactics, leapfrogging is a technique for advancing personnel and/or equipment on or past a target area being defended by an opposing force. This technique is taught in U.S. Army Basic Training and reinforced with all unit and advanced training throughout a soldier’s career...

was accepted, with the lead platoon taking an objective and the following platoons passing through them and onto the next objective, while the Lewis gunners provided fire support. Grenades were used for clearing trenches and dugouts, each battalion carried forward two trench mortars to provide fire support.

Tank tactics

The tank was designed to break the deadlock of trench warfare. In their first use on the Somme, they were placed under command of the infantry and ordered to attack their given targets in groups or pairs. They were also assigned small groups of troops, who served as an escort while providing close defence against enemy attacks. Only nine tanks reached the German lines to engage machine gun emplacements and troop concentrations. On the way, 14 broke down or were ditched, another 10 were damaged by enemy fire.In 1917, during the battle of Cambrai, the Tank Corps

Royal Tank Regiment

The Royal Tank Regiment is an armoured regiment of the British Army. It was formerly known as the Tank Corps and the Royal Tank Corps. It is part of the Royal Armoured Corps and is made up of two operational regiments, the 1st Royal Tank Regiment and the 2nd Royal Tank Regiment...

adopted new tactics. Three tanks working together would advance in a triangle formation, with the two rear tanks providing cover for an infantry platoon. The tanks were to create gaps in the barbed wire for the accompanying infantry to pass through, then use their armament to suppress the German strong points. The effectiveness of tank–infantry cooperation was demonstrated during the battle, when Major General George Montague Harper

George Montague Harper

Lieutenant General Sir George Montague Harper KCB, DSO was a British general during the First World War.-Military career:...

of the 51st (Highland) Division refused to cooperate with the tanks, a decision that compelled them to move forward without any infantry support; the result was the destruction of more than 12 tanks by German artillery sighted behind bunkers.

The situation had changed again by 1918, when tank attacks would have one tank every 100 or 200 yd (182.9 m), with a tank company of 12-16 tanks per objective. One section

Section (military unit)

A section is a small military unit in some armies. In many armies, it is a squad of seven to twelve soldiers. However in France and armies based on the French model, it is the sub-division of a company .-Australian Army:...

of each company would be out in front, with the remainder of the company following behind and each tank providing protection for an infantry platoon, who were instructed to advance, making use of available cover and supported by machine gun fire. When the tanks came across an enemy strong point, they would engage the defenders, forcing them into shelter and leaving them to the devices of the following infantry.

Artillery tactics

Royal Horse Artillery

The regiments of the Royal Horse Artillery , dating from 1793, are part of the Royal Regiment of Artillery of the British Army...

employed the 13-pounder, while the Royal Field Artillery

Royal Field Artillery

The Royal Field Artillery of the British Army provided artillery support for the British Army. It came into being when the Royal Artillery was divided on 1 July 1899, it was reamalgamated back into the Royal Artillery in 1924....

used the 18-pounder gun. By 1918, the situation had changed; the artillery were the dominant force on the battlefield. Between 1914 and 1918, the Royal Field Artillery had increased from 45 field brigades to 173 field brigades, while the heavy and siege artillery of the Royal Garrison Artillery

Royal Garrison Artillery

The Royal Garrison Artillery was an arm of the Royal Artillery that was originally tasked with manning the guns of the British Empire's forts and fortresses, including coastal artillery batteries, the heavy gun batteries attached to each infantry division, and the guns of the siege...

had increased from 32 heavy and six siege batteries to 117 heavy and 401 siege batteries.

With this increase in the number of batteries of heavier guns, the armies needed to find a more efficient method of moving the heavier guns around. (It was proving difficult to find the number of draught horses required.) The War office

War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government, responsible for the administration of the British Army between the 17th century and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the Ministry of Defence...

ordered over 1,000 Holts caterpillar tractors

Holt tractor

The Holt tractors were a range of caterpillar tractors built by the Holt Manufacturing Company, which was named after Benjamin Holt- Military Use :...

, which transformed the mobility of the siege artillery. The army also mounted a variety of surplus naval guns on various railway platforms to provide mobile long-range heavy artillery on the Western Front.

Until 1914, artillery generally fired over open sights at visible targets, the largest unit accustomed to firing at a single target was the artillery regiment or brigade. One innovation brought about by the adoption of trench warfare was the barrage

Barrage (artillery)

A barrage is a line or barrier of exploding artillery shells, created by the co-ordinated aiming of a large number of guns firing continuously. Its purpose is to deny or hamper enemy passage through the line of the barrage, to attack a linear position such as a line of trenches or to neutralize...

—a term first used in the battle of Neuve Chapelle

Battle of Neuve Chapelle

The Battles of Neuve Chapelle and Artois was a battle in the First World War. It was a British offensive in the Artois region and broke through at Neuve-Chapelle but they were unable to exploit the advantage.The battle began on 10 March 1915...

in 1915. Trench warfare had created the need for indirect fire

Indirect fire

Indirect fire means aiming and firing a projectile in a high trajectory without relying on a direct line of sight between the gun and its target, as in the case of direct fire...