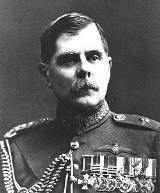

Hugh Trenchard, 1st Viscount Trenchard

Encyclopedia

Marshal of the Royal Air Force

Hugh Montague Trenchard, 1st Viscount Trenchard GCB OM

GCVO DSO

(3 February 1873 – 10 February 1956) was a British

officer who was instrumental in establishing the Royal Air Force

. He has been described as the Father of the Royal Air Force.

During his formative years Trenchard struggled academically, failing many examinations and only just succeeding in meeting the minimum standard for commissioned service in the British Army

. As a young infantry officer, Trenchard served in India and with the outbreak of the Boer War

, he volunteered for service in South Africa. Whilst fighting the Boers, Trenchard was critically wounded and as a result of his injury, he lost a lung, was partially paralysed and returned to Great Britain. On medical advice Trenchard travelled to Switzerland to recuperate and boredom saw him taking up bobsleighing. After a heavy crash, Trenchard found that his paralysis was gone and that he could walk unaided. Following further recuperation, Trenchard returned to active service in South Africa.

After the end of the Boer War, Trenchard saw service in Nigeria

where he was involved in efforts to bring the interior under settled British rule and quell inter-tribal violence. During his time in West Africa, Trenchard commanded the Southern Nigeria Regiment

for several years.

In 1912, Trenchard learned to fly and he was subsequently appointed as second in command of the Central Flying School

. He held several senior positions in the Royal Flying Corps

during World War I, serving as the commander of the Royal Flying Corps in France from 1915 to 1917. In 1918, he briefly served as the first Chief of the Air Staff before taking up command of the Independent Air Force

in France. Returning as Chief of the Air Staff under Winston Churchill

in 1919, Trenchard spent the following decade securing the future of the Royal Air Force

. He was Metropolitan Police Commissioner in the 1930s and a defender of the RAF in his later years. Trenchard is recognized today as one of the early advocates of strategic bombing

.

, England

on 3 February 1873. He was the third child and second son of Henry Montague Trenchard and his wife Georgina Louisa Catherine Tower. Trenchard's father was a captain

in the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

and his mother was the daughter of the Royal Navy

captain

John McDowall Skene. Although in the 1870s the Trenchards were living in an unremarkable fashion, their forebears had played notable roles in English history. The family claimed descent from Raoul de Trenchant, a knight and one of the close companions of William the Conqueror who fought alongside him at the Battle of Hastings

. Other notable ancestors were Sir Thomas Trenchard, a High Sheriff of Dorset in the 16th century and Sir John Trenchard

, the Secretary of State under William III

.

When Hugh Trenchard was two, the family moved to Courtlands, a farm-cum-manor house less than three miles (4 km) from the centre of Taunton. The country setting meant that the young Trenchard could enjoy an outdoor life, including spending time hunting rabbits and other small animals with the rifle he was given on his eighth birthday. It was during his junior years that Trenchard and his siblings were educated at home by a resident tutor, whom Trenchard did not respect. Unfortunately for Trenchard's education, the tutor was neither strict enough nor skillful enough to overcome the children's mischievous attempts to avoid receiving instruction. As a consequence, Trenchard did not excel academically; however, his enthusiasm for games and riding

was evident.

.jpg) At the age of 10, Trenchard was sent to board at Allens Preparatory School near Botley

At the age of 10, Trenchard was sent to board at Allens Preparatory School near Botley

in Hampshire

. Although he did well at arithmetic, he struggled with the rest of the curriculum. However, Trenchard's parents were not greatly concerned by his educational difficulties, believing that it would be no impediment to him following a military career. Georgina Trenchard wanted her son to follow her father's profession and enter the Royal Navy. In 1884, Trenchard was moved to Dover where he attended Hammond's, a cramming school

for prospective entrants to HMS Britannia

. Trenchard failed the Navy's entrance papers, and at the age of 13 he was sent to the Reverend Albert Pritchard's crammer, Hill Lands in Wargrave

, Berkshire

. Hill Lands prepared its pupils for Army commissions and although Trenchard excelled at rugby

, as before he did not apply himself to his studies.

In 1889, when Hugh Trenchard was 16 years old, his father, who had become a solicitor

, was declared bankrupt. After initially being removed from Hill Lands, the young Trenchard was only able to return thanks to the charity of his relatives. Trenchard failed the Woolwich examinations twice and was then relegated to applying for the Militia

which had lower entry standards. Even the Militia's examinations proved difficult for Trenchard and he failed in 1891 and 1892. During this time, Trenchard underwent a period of training as a probationary subaltern with the Forfar and Kincardine Artillery

. Following his return to Pritchard's, Trenchard finally achieved a bare pass in March 1893. At the age of 20, he was gazetted

as a second-lieutenant in the Second Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers

and posted to India

.

in the Punjab

. Not long after his arrival, Trenchard was called upon to make a speech at a mess

dinner night

. It was common practice for the youngest subaltern to make such a speech and Trenchard was expected to cover several highlights of the Royal Scots Fusiliers' history. Instead, he simply said "I am deeply proud to belong to this great regiment", followed by "I hope one day I shall live to command it." His 'speech' was received with hoots of incredulous laughter, although some appreciated his nerve.

Young officers stationed in India in the 1890s enjoyed many social and sporting diversions and Trenchard did little militarily. While every regiment was required to undertake a period of duty beyond the Khyber Pass

, for the most part conditions of peace and prosperity were evident and Trenchard was able to engage in various sporting activities. In early 1894 he won the All-India Rifle Championship. After his success at shooting, Trenchard set about establishing a battalion polo

team. Being of the infantry, his regiment had no history of playing polo and there were many obstacles for Trenchard to overcome. However, within six months the battalion polo team was competing and holding its own. It was during a polo match in 1896 that Trenchard first met Winston Churchill

, with whom he clashed on the field of play. Trenchard's sporting prowess saved his reputation amongst his fellow officers. In other respects he did not fit in; lacking social graces and choosing to converse little, he was nicknamed "the camel", as like the beast he neither drank nor spoke.

It was also during Trenchard's time in India that he took up reading. His first choice was for biographies, particularly of British heroes. Trenchard kept the long hours he spent reading quiet, but in so doing succeeded in providing himself with an education where the service crammers had failed. However, in military terms Trenchard was dissatisfied. He failed to see any action during his time in India, missing out on his regiment's turn at the frontier, as he was in England on sick leave for a hernia

operation.

With the outbreak of the Second Boer War

in October 1899, Trenchard applied several times to rejoin his old battalion which had been sent to the Cape

as part of the expeditionary corps. Trenchard's requests were rejected by his Colonel, and when the Viceroy Lord Curzon

, who was concerned about the drain of leaders to South Africa, banned the dispatch of any further officers, Trenchard's prospects for seeing action looked bleak. However, a year or two previously, it had so happened that Trenchard had been promised help or advice from Sir Edmond Elles

, as a gesture of thanks after Trenchard had rescued a poorly planned rifle-shooting contest from disaster. By 1900, Elles was Military Secretary to Lord Curzon and Trenchard (recently promoted to captain

) sent a priority signal to Elles requesting that he be permitted to rejoin his unit overseas. This bold move worked, and Trenchard received his orders for South Africa

several weeks later.

and in July 1900 he was ordered to raise and train a mounted company within the 2nd Battalion. The Boer

s were accomplished horsemen and the tactics of the day placed a heavy strain upon the British cavalry. Accordingly, the British sought to raise mounted infantry units and Trenchard's polo playing experiences led to him being selected to raise a mounted unit for service west of Johannesburg

. Part of Trenchard's new company consisted of a group of volunteer Australian horsemen who, thus far being under-employed, had largely been noticed for excessive drinking, gambling and debauchery.

Trenchard's company came under the command of the 6th (Fusilier) Brigade which was headquartered at Krugersdorp. During September and early October 1900 Trenchard's riders were involved in several skirmishes in the surrounding countryside. On 5 October the 6th Brigade, including Trenchard, departed Krugersdorp with the intention of drawing the Boers into battle on the plain where they might be defeated. However, before the Brigade could reach the plain it had to pass through undulating terrain which favoured the Boer guerrilla tactics

.

The Brigade travelled by night and at dawn on 9 October the Ayrshire Yeomanry, who were in the vanguard, disturbed a Boer encampment. The Boers fled on horseback and Trenchard with his Australians pursued them for 10 miles (16.1 km). The Boers, finding themselves unable to shake off Trenchard's unit, led them into a trap. The Boers rode up a steep slope and disappeared into the valley beyond. When Trenchard made the ridge he saw the Dwarsvlei farmhouse with smoke coming from the chimney. It appeared to Trenchard that the Boers thought they had got away and were eating breakfast unawares. Trenchard placed his troops on the heights around the building and after half an hour's observation, he led a patrol of four men down towards the farmhouse. The remainder of Trenchard's troops were to close in on his signal. However, when Trenchard and his patrol reached the valley floor and broke cover, the Boers opened fire from about a dozen points and bullets whistled past Trenchard and his men. Trenchard pressed forward and reached the sheltering wall of the farmhouse. As he headed for the door, Trenchard was felled by a Boer bullet to the chest. The Australians, seeing their leader fall, descended from the heights and engaged the Boers at close quarters

in and around the farmhouse. Many of the Boers were killed or wounded, a few fled and several were taken prisoner. Trenchard was critically wounded and medically evacuated to Krugersdorp.

through a tube. On the third day, Trenchard regained consciousness but spent most of that day sleeping. After three weeks, Trenchard had shown some improvement and was moved to Johannesburg where he made further progress. However when he tried to rise from his bed, Trenchard discovered that he was unable to put weight on his feet, leading him to suspect that he was partially paralysed. He was next moved to Maraisburg for convalescing and there Trenchard confirmed that he was suffering from partial paralysis below the waist. The doctors surmised that after passing through his lung, the bullet had damaged his spine.

In December 1900, Trenchard returned to England, arriving by hospital ship at Southampton

. He hobbled with the aid of sticks down the gangplank where his concerned parents met him. As a disabled soldier without independent financial means, Trenchard was now at his lowest point. He spent the next fortnight at the Mayfair

nursing home for disabled officers which was run by the Red Cross. Trenchard's case came to the attention of Lady Dudley

, by whose philanthropic efforts the Mayfair nursing home operated. Through her generosity she arranged for Trenchard to see a specialist who told Trenchard that he needed to spend several months in Switzerland

where the air was likely to be of benefit to his lung. Trenchard and his family could not afford the expense and Trenchard was too embarrassed to explain the situation. However, without asking any questions, Lady Dudley presented Trenchard with a cheque

to cover the costs.

On Sunday 30 December, Trenchard arrived in St Moritz to begin his Swiss convalescence. Boredom saw him take up bobsleigh

On Sunday 30 December, Trenchard arrived in St Moritz to begin his Swiss convalescence. Boredom saw him take up bobsleigh

ing as it did not require much use of his legs. Initially he was prone to leave the run and end up in the snow, but after some days of practice he usually managed to stay on track. It was during a heavy crash from the Cresta Run

that his spine was somehow readjusted, enabling him to walk freely immediately after regaining consciousness. Around a week later, Trenchard won the St. Moritz Tobogganing Club's Freshman and Novices' Cups for 1901; a remarkable triumph for a man who had been unable to walk unaided only a few days before.

On arriving back in England, Trenchard visited Lady Dudley to thank her and then set about engineering his return to South Africa. His lung was not fully healed, causing him pain and leaving him breathless. Furthermore, the War Office

were sceptical about Trenchard's claim to be fully fit and were disinclined to allow him to forego his remaining nine months of sick leave. Trenchard then took several months of tennis

coaching in order to strengthen his remaining lung. Early in the summer of 1901 he entered two tennis competitions, reaching the semi-finals both times and gaining favourable press coverage. He then sent the newspaper clippings to the doctors at the War Office, arguing that this tennis ability proved he was fit for active service. Not waiting for a reply, Trenchard boarded a troop ship in May 1901, passing himself off as a volunteer for a second tour of duty.

, arriving there in late July 1901. He was assigned to a company of the 12th Mounted Infantry where his patrolling duties required him to spend long days in the saddle. Trenchard's wound still caused him considerable pain and the entry and exit scars frequently bled.

Later in the year, Trenchard was summoned to see Kitchener

Later in the year, Trenchard was summoned to see Kitchener

, who was by then the Commander-in-Chief. Trenchard was tasked with reorganizing a demoralized mounted infantry company, which he completed in under a month. Kitchener then sent Trenchard to D'Aar in the Cape Colony

to expedite the training of a new corps of mounted infantry. Kitchener summoned Trenchard for the third time in October 1901, this time sending Trenchard on a mission to capture the Boer Government who were in hiding. Kitchener had received intelligence

on their location and he hoped to damage the morale of Boer commandos at large by sending a small group of men to capture the Boer Government. Trenchard was accompanied by a column of so-called loyalist Boers whose motives he suspected. Also with Trenchard were several British NCO

s and nine mixed race guides. After riding through the night, Trenchard's party were ambushed the next morning. Trenchard and his men took cover and gave fight. After Trenchard's column had suffered casualties, the ambush party withdrew. Although this last mission failed, Trenchard was praised for his efforts with a mention in dispatches

.

Trenchard spent the remainder of 1901 on patrolling duties, and in early 1902 he was appointed acting commander of the 23rd Mounted Infantry Regiment. During the last few months of the War, Trenchard only once got to lead his Regiment into action. In response to Boer cattle rustling

, Zulu raiders crossed the border into the Transvaal

and the 23rd Mounted Infantry Regiment took action. After peace terms were agreed in May 1902, Trenchard was involved in supervising the disarming of the Boers and later took leave

. In July, the 23rd Mounted Infantry was recalled to Middleburg

four hundred miles to the south and after the trek Trenchard occupied himself with polo and race

meetings. Trenchard was promoted to brevet

major in August 1902.

with the promise that he was entitled to lead all regimental expeditions. On arrival in Nigeria in December 1903, Trenchard initially had some difficulty in getting his Commanding Officer to allow him to lead the upcoming expedition and only replaced his superior by going over his head.

Once established, Trenchard spent the next six years on various expeditions to the interior patrolling, surveying and mapping an area of 10,000 square miles which later came to be known as Biafra

. In the occasional clashes with the Ibo tribesmen

, Trenchard gained decisive victories. The many tribesmen who surrendered were used to build roads and thereby cement the British control on the region. From summer 1904 to the late summer 1905, Trenchard was acting Commandant of the Southern Nigeria Regiment. He was appointed to the Distinguished Service Order in 1906 and was Commandant with the temporary rank of lieutenant colonel from 1908 onwards.

. Back in England, Trenchard did not recover quickly and probably prolonged his convalescence by over-exertion. However, by the late summer he was well enough to take his parents on holiday to the West Country

.

October 1910 saw Trenchard posted to Derry

where the Second Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers were garrisoned. Trenchard was reduced from a temporary lieutenant-colonel to major and made a company commander. As before, Trenchard occupied himself with playing polo and he took up hunting. Finding peace-time regimental life dull, Trenchard sought to expand his area of responsibility by attempting to re-organize his fellow officers' administrative procedures, which they resented. Trenchard also clashed with Colonel Stuart, his commanding officer, who told Trenchard that the town was too small for both of them and by February 1912 Trenchard had resorted to applying for employment with various colonial defence forces without success.

During his time in Ireland

During his time in Ireland

, Trenchard received a letter from Captain Eustace Loraine

, urging him to take up flying

. Trenchard and Loraine had been friends in Nigeria, and on his return to England, Loraine had learnt to fly. After some effort, Trenchard persuaded his Commanding Officer to grant him three months of paid leave so that he might train as a pilot. Trenchard arrived in London

on 6 July 1912, only to discover that Captain Loraine had been killed in a flying accident on the previous day. At the age of 39, Trenchard was just short of 40, the maximum age for military student pilots at the Central Flying School

, and so he did not postpone his plan to become an aviator.

When Trenchard arrived at Thomas Sopwith

's flying school at Brooklands

, he told Sopwith than he only had 10 days to gain his aviator's certificate. Trenchard succeeded in going solo on 31 July, gaining his Royal Aero Club

aviator's certificate (No. 270) on a Henry Farman biplane. The course had cost £75, involved a meagre two-and-a-half weeks tuition and a grand total of 64 minutes in the air. Although Copland Perry

, Trenchard's instructor, noted that teaching him to fly had been "no easy performance", Trenchard himself had been "a model pupil." Trenchard's difficulties were in some measure due to his partial blindness in one eye, a fact he kept secret.

Trenchard arrived at Upavon airfield

, where the Central Flying School was based, and was assigned to Arthur Longmore

's flight. Bad weather delayed Longmore from assessing his new pupil, and before the weather improved, the School's Commandant, Captain Godfrey Paine

RN

had co-opted Trenchard to the permanent staff. Part of Trenchard's new duties included those of School examiner, and so he set himself a paper, sat it, marked it and awarded himself his 'wings

'. Trenchard's flying ability still left much to be desired, and Longmore soon discovered his pupil's deficiencies. Over the following weeks Trenchard spent many hours improving his flying technique. After Trenchard had finished his flying course, he was officially appointed as an instructor. However, Trenchard was a poor pilot, and he did no instructing, instead becoming involved in administrative duties. As a member of the staff, Trenchard set to work organizing training and establishing procedures. He paid particular attention to ensuring that skills were acquired in practical topics such as map reading, signalling and engine mechanics. It was during his time at the Central Flying School that Trenchard earned the nickname "Boom" either for his stentorian utterances or for his low rumbling tones.

In September 1912, Trenchard acted as an air observer

during the Army Manoeuvres

. His experiences and actions developed his understanding of the military utility of flying. The following September, Trenchard was appointed Assistant Commandant and promoted to temporary lieutenant-colonel. Trenchard's paths crossed once more with Winston Churchill

, who was by then First Lord of the Admiralty, and learning to fly at Eastchurch and Upavon. Trenchard formed a distinctly unfavourable opinion of Churchill's ability as a pilot.

, Trenchard was appointed Officer Commanding the Military Wing of the Royal Flying Corps, replacing Lieutenant-Colonel Sykes

. This appointment put Trenchard in charge of the Royal Flying Corps in Great Britain, which retained one third of the Corps' total strength. Trenchard's headquarters were at Farnborough

and being disappointed about remaining in England, he applied to rejoin his old regiment in France. However, the head of the RFC, General Sir David Henderson, refused to release him. Trenchard's new duties included providing replacements and raising new squadrons for service on the continent. Trenchard initially set himself a target of 12 squadrons. However, Sefton Brancker

, the Assistant Director of Military Aeronautics, suggested that this should be raised to 30 and Lord Kitchener

later set the target at 60. In order to create these squadrons, Trenchard commandeered his old civilian training school at Brooklands and then used its aircraft and equipment as a starting point for the establishment of new training schools elsewhere.

In early October 1914, Kitchener sent for Trenchard and tasked him with providing a battle-worthy squadron forthwith. The squadron was to be used to support land and naval forces seeking to prevent the German flanking manoeuvres during the Race to the Sea

. On 7 October, only 36 hours later, No. 6 Squadron

flew to Belgium

, the first of many additional squadrons to be provided.

Later in October, detailed planning for a major reorganization of the Flying Corps' command structure took place. Henderson offered Trenchard command of the soon-to-be created First Wing

. Trenchard accepted the offer on the basis that he would not be subordinated to Sykes, whom he distrusted. The next month, the Military Wing was abolished and its units based in Great Britain were re-grouped as the Administrative Wing. Command of the Administrative Wing was given to Lieutenant Colonel E B Ashmore

.

. On his arrival Trenchard discovered that Sykes was to replace Henderson as Commander of the Royal Flying Corps in the Field, making Sykes Trenchard's immediate superior. Trenchard bore Sykes some animosity and their working relationship was troubled. Trenchard appealed to Kitchener, by then the Secretary of State for War

, threatening to resign. Trenchard's discomfort was relieved when in December 1914 Kitchener ordered that Henderson resume command of the Royal Flying Corps in the Field. Trenchard's First Wing consisted of Nos Two and Three Squadrons and flew in support of the IV Corps and the Indian Corps

. After the First Army under General Haig

came into being in December, the First Wing provided support to the First Army.

In early January 1915, Haig summoned Trenchard to explain what might be achieved in the air. During the meeting Haig brought Trenchard into his confidence regarding his plans for a March attack in the Merville/Neuve Chapelle region. After aerial photographic reconnaissance had been gathered, the Allied plans were reworked in February. During the Battle of Neuve Chapelle

in March, the RFC and especially the First Wing supported the land offensive. This was the first time that aircraft were used as bombers with explosives strapped to the wings and fuselage as opposed to being released by hand which had happened earlier in the War. However, the bombing from the air had little effect and the artillery

disregarded the information provided by the RFC's airmen. Prior to Haig's offensives at Ypres

and Aubers Ridge

in April and May, Trenchard's camera crews flew reconnaissance sorties over the German lines. Despite the detailed information this provided and the improved air-artillery cooperation during the battles, the offensives were inconclusive. At the end of this engagement Henderson offered Trenchard the position as his chief of staff. Trenchard declined the offer, citing his unsuitability for the role although his ambition for command may have been the real reason. In any case, this did not stop his promotion to full colonel in June 1915.

On Henderson's return to the War Office in the summer of 1915, Trenchard was promoted to brigadier-general and appointed Officer Commanding the RFC in France. Trenchard was to serve as the head of the RFC in the field until the early days of 1918. In late 1915 when Haig was appointed as commander of the British Expeditionary Force, Haig and Trenchard re-established their partnership, this time at a higher level. In March the following year, with the RFC expanding, Trenchard was promoted to major-general

.

Trenchard’s time in command was characterized by three priorities. First was his emphasis on support to and co-ordination with ground forces. This support started with reconnaissance and artillery co-ordination and later encompassed tactical low-level bombing of enemy ground forces. While Trenchard did not oppose the strategic bombing of Germany in principle, he opposed moves to divert his forces on to long-range bombing missions as he believed the strategic role to be less important and his resource to be too limited. Secondly, he stressed the importance of morale, not only of his own airmen, but more generally the detrimental effect that the presence of an aircraft had upon the morale of opposing ground troops. Finally, Trenchard had an unswerving belief in the importance of offensive action. Although this belief was widely held by senior British commanders, the RFC's offensive posture resulted in the loss of many men and machines and some doubted its effectiveness.

Following the Gotha raids on London

in the summer of 1917, the Government considered creating an air force by merging the RFC and the Royal Naval Air Service. Trenchard opposed this move believing that it would dilute the air support required by the ground forces in France. By October he realized that the creation of an air force was inevitable and, seeing that he was the obvious candidate to become the new Chief of the Air Staff, he attempted to bring about a scheme whereby he would retain control of the flying units on the Western Front. In this regard Trenchard was unsuccessful and he was succeeded in France by Major-General John Salmond

.

on 29 November 1917, there followed a period of political manoeuvring and speculation over who would take up the new posts of Air Minister

, Chief of the Air Staff and other senior positions within soon-to-be created Air Ministry

. Trenchard was summoned back from France, crossing the Channel on a destroyer

on the morning of 16 December. At around 3 pm, Trenchard met newspaper proprietor Lord Rothermere who had recently been appointed as Air Minister. Rothermere offered Trenchard the post of Chief of the Air Staff and before Trenchard could respond, Rothermere explained that Trenchard's support would be useful to him as he was about to launch a press campaign against Sir Douglas Haig and Sir William Robertson, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff. Trenchard flatly refused the job, being personally loyal to Haig and antipathetic to political intrigue. Rothermere and his brother Lord Northcliffe

, who was also present, then spent over 12 hours acrimoniously debating with Trenchard. The brothers pointed out that if Trenchard refused, they would use the fact to attack Haig on the false premise

that Haig had refused to release Trenchard. Trenchard defended Haig's policy of constant attack, arguing that it had been preferable to standing on the defensive and he also had maintained an offensive posture throughout the War which, like the infantry, had resulted in the Flying Corps taking dreadful casualties. In the end, the brothers wore Trenchard down and he accepted the post on the condition that he first be permitted to consult Haig. After meeting with Haig, Trenchard wrote to Rothermere, accepting the post.

The New Year saw Trenchard made a knight commander of the Order of the Bath

and appointed Chief of the Air Staff on the newly formed Air Council. Trenchard began work on 18 January and during his first month at the Air Ministry, he clashed with Rothermere over several issues. First, Rothermere's tendency to disregard his professional advisors in favour of outside experts irritated Trenchard. Secondly, Rothermere insisted that Trenchard claim as many men for the RAF as possible even if they might be better employed in the other services. Finally and most significantly, they disagreed over proper future use of air power which Trenchard judged as being vital in preventing a repeat of the strategic stalemate which had occurred along the Western Front. Also during this time Trenchard resisted pressure from several press barons to support an "air warfare scheme" which would have seen the British armies withdrawn from France and the defeat of Germany entrusted to the RAF. Despite the arguments and his differences with Rothermere, Trenchard was able to put in place planning for the merger of the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service

. However, as the weeks went on, Trenchard and Rothermere became increasingly estranged and a low point was reached in mid-March when Trenchard discovered that Rothermere had promised the Navy 4000 aircraft for anti-submarine duties. Trenchard accorded the highest priority to air operations on the Western Front and there were fewer than 400 spare aircraft in Great Britain. On 18 March, Trenchard and Rothermere exchanged letters, Trenchard expressing his dissatisfaction and Rothermere curtly replying. The following day Trenchard sent Rothermere a letter of resignation and although Rothermere called for Trenchard and asked him to remain, Trenchard only agreed to defer the date until after 1 April when the Royal Air Force

would officially come into being.

After the Germans overran the British Fifth Army on 21 March, Trenchard ordered all the available reserves of aircrew, engines and aircraft be speedily transported to France. Reports reached Trenchard on 26 March that concentrations of Flying Corps' machines were stopping German advances. On 5 April, Trenchard travelled to France, inspecting squadrons and updating his understanding of the air situation. On his return, Trenchard briefed Lloyd George and several other ministers on air activity and the general situation.

On 10 April, Rothermere informed Trenchard that the War Cabinet had accepted his resignation and Trenchard was offered his old job in France. Trenchard refused the offer saying that replacing Salmond at the height of battle would be "damnable". Three days later Major-General Frederick Sykes

replaced Trenchard as Chief of the Air Staff. On the following Monday, Trenchard was summoned to Buckingham Palace

where King George

listened to Trenchard's account of the events which caused him to resign. Trenchard then wrote to the Prime Minister stating the facts of his case and pointing out that in the course of the affair, Rothermere had stated his intention to resign also. Trenchard's letter was circulated amongst the Cabinet with a vindictive response written by Rothermere. Around the same time, the question of Rothermere's general competence as Air Minister was brought to the attention of Lloyd George. Rothermere, realizing his situation, offered his resignation which was made public on 25 April.

which was to conduct long-range bombing operations against Germany. Instead, Trenchard, seeking equal status with Sykes, argued for a reorganization of the RAF which would have seen himself appointed as the RAF's commander of fighting operations while Sykes would have been left to deal with administrative matters. Weir did not accept Trenchard's proposal and instead gave Trenchard several options. Trenchard rejected the offer of a proposed new post which would have seen him given a London-based command of the bombing operations conducted from Ochey, arguing that the responsibility was Newall's under the direction of Salmond. He also turned down the post of Grand Co-ordinator of British and American air policy and that of Inspector General of the RAF overseas. Weir then offered Trenchard command of all air force units in the Middle East or the post of Inspector General of the RAF at home but strongly encouraged him to take command of the independent long-range bombing forces in France.

Trenchard had many reasons for not accepting any of the posts which he saw as being artificially created, of little value or lacking authority. On 8 May Trenchard was sitting on a bench in Green Park

and overheard one naval officer saying to another "I don't know why the Government should pander to a man who threw in his hand at the height of a battle. If I'd my way with Trenchard I'd have him shot." After Trenchard had walked home, he wrote to Weir accepting command of the as yet unformed Independent Air Force

.

from which it was formed, carrying out intensive strategic bombing attacks on German railways, airfields and industrial centres. Initially, the French general Ferdinand Foch

refused to recognize the Independent Air Force which caused some logistical difficulties. The problems were resolved after a meeting of Trenchard and General de Castelnau

, who disregarded the concerns about the status of the Independent Air Force and did not block the much needed supplies. Trenchard also improved the links between the RAF and the American Air Service

, providing advanced tuition in bombing techniques to American aviators.

In September 1918, Trenchard's Force indirectly supported the American Air Service during the Battle of Saint-Mihiel

, bombing German airfields, supply depots and rail lines. Trenchard's close co-operation with the Americans and the French was formalized when his command was redesignated the Inter-Allied Independent Air Force in late October 1918 and placed directly under Foch

, the supreme commander. When the November armistice came, Trenchard sought and received permission from Foch to return his squadrons to British command. Trenchard was succeeded as commander of the Independent Air Force by his deputy Brigadier-General Courtney

. Trenchard departed France in mid-November and returned to Great Britain to take a holiday.

. Putting on his Army general's uniform he arrived in Southampton with a staff of two, his clerk and Maurice Baring, his aide-de-camp. Trenchard initially attempted to speak to the mutinying soldiers but was heckled and jostled. He then arranged for armed troops to be sent to Southampton and when Trenchard threatened lethal force, the mutineers surrendered, bringing matters to a close without bloodshed.

and Secretary of State for Air

. While Churchill was preoccupied with implementing post-War defence cuts and the demobilization of the Army, the Chief of the Air Staff, Major-General Frederick Sykes, submitted a paper with what were at the time unrealistic proposals for a large air force of the future. Being dissatisfied with Sykes, Churchill began to consider reinstating Trenchard whose recent performance at Southampton had once more brought him into favour with Churchill.

During the first week in February, Trenchard was summoned to London by official telegram. At the War Office, Trenchard met with Churchill, who asked him to come back as Chief of the Air Staff. Trenchard replied that he could not take up the appointment as Sykes was currently in post. After Churchill indicated that Sykes might be appointed Controller of Civil Aviation and made a knight grand cross

of the Order of the British Empire

, Trenchard agreed to consider the offer. Churchill, not wanting to leave matters hanging, asked Trenchard to provide him with a paper outlining his ideas on the re-organization of the Air Ministry. Trenchard's brief written statement of the essentials required met with Churchill's approval and he insisted that Trenchard take the appointment. Trenchard returned to the Air Ministry in mid-February and formally took up post as Chief of the Air Staff on 31 March 1919.

For most of March Trenchard was unable to do much work as he had contracted Spanish flu

. During this period he wrote to Katherine Boyle (née Salvin), the widow of his friend and fellow officer James Boyle, whom he knew from his time in Ireland. At Trenchard's request, Mrs Boyle took on the task of nursing him back to health. Once Trenchard had recovered, he proposed marriage to Katherine Boyle, who refused his offer. Trenchard remained in contact with her and when he proposed marriage again, she accepted. On 17 July 1920, Hugh Trenchard married Katherine Boyle at St. Margaret's Church

in Westminster

.

were decided upon, despite some opposition from members of the Army Council. Trenchard himself was regraded from major-general to air vice-marshal

and then promoted to air marshal

a few days later.

By the autumn of 1919, the budgetary effects of Lloyd George's Ten Year Rule

were causing Trenchard some difficulty as he sought to develop the institutions of the RAF. He had to argue against the view that the Army and Navy should provide all the support services and education, leaving the RAF only to provide flying training. Trenchard viewed this idea as a precursor to the break-up of the RAF and in spite of the costs, he wanted his own institutions which would develop airmanship

and engender the air spirit. Having convinced Churchill of his case, Trenchard oversaw the founding of the RAF (Cadet) College at Cranwell as the world's first military air academy. Later, in 1920, Trenchard inaugurated the Aircraft Apprentice

scheme which provided the RAF with specialist groundcrew for over 70 years. In 1922, the RAF Staff College

at Andover was set up to provide air force-specific training to the RAF's middle ranking officers.

Late 1919 saw Trenchard created a baronet

and granted £10,000. Although Trenchard had attained a measure of financial security, the future of the RAF was far from assured. Trenchard judged that the chief threat to his service came from the new First Sea Lord

, Admiral Beatty

. Looking to take the initiative, Trenchard arranged to see Beatty, meeting with him in early December. Trenchard, arguing that the "air is one and indivisible", put forward a case for an air force with its own strategic role which also controlled army and navy co-operation squadrons. Beatty did not accept Trenchard's argument and Trenchard resorted to asking for a 12 months amnesty to put in plans into action. The request appealed to Beatty's sense of fair play and he agreed to let Trenchard be until the end of 1920. Around this time Trenchard indicated to Beatty that control over some supporting elements of naval aviation (but not aircrew or aircraft) might be returned to the Admiralty. Trenchard also offered Beatty the option of locating the Air Ministry staff who worked in connection with naval aviation at the Admiralty. Beatty declined the offer and later, when no transfer of any naval aviation assets occurred, came to the view that Trenchard had acted in bad faith.

During the early 1920s, the continued independent existence of the RAF and its control of naval aviation were subject to a series of Government reviews. The Balfour report of 1921, the Geddes Axe

of 1922 and the Salisbury Committee of 1923 all found in favour of the RAF despite lobbying from the Admiralty and opposition in Parliament. On each occasion Trenchard and his staff officers, supported by Christopher Bullock

, worked to show that the RAF provided good value for money and was required for the long-term strategic security of the United Kingdom.

Trenchard also sought to secure the future of the RAF by finding a war-fighting role for the new Service. In 1920 he successfully argued that the RAF should take the lead during the operation to restore peace in Somaliland

. The success of this small air action then allowed Trenchard to put the case for the RAF's policing of the British Empire

and in 1922 the RAF was given control of all British Forces in Iraq

. The RAF also carried out imperial air policing over India's North-West Frontier Province

. More controversially, in early 1920, he wrote that the RAF could even suppress "industrial disturbances or risings" in Britain itself. The idea was not to Churchill's liking and he told Trenchard not to refer to this proposal again.

scheme and in 1925 the first three UAS squadrons were formed at Cambridge

, London and Oxford

.

Since the early 1920s Trenchard had supported the development of a flying bomb

Since the early 1920s Trenchard had supported the development of a flying bomb

and by 1927 a prototype, code-named "Larynx

", was successfully tested. However, development costs were not insignificant and in 1928, when Trenchard applied for further funding, the Committee of Imperial Defence

and the Cabinet discontinued the project. Following the British failure to win the Schneider Trophy

in 1925, Trenchard ensured that finances were available for an RAF team and the High Speed Flight

was formed in preparation for the 1927 race. After the British won in 1927, Trenchard continued to use Air Ministry funds to support the race, including purchasing two Supermarine S.6

aircraft which won the race in 1929. Trenchard was criticised by some in the Treasury

for wasting money.

On 1 January 1927, Trenchard was promoted from air chief marshal

to marshal of the Royal Air Force

, becoming the first person to hold the RAF's highest rank. The following year Trenchard began to feel that he had achieved all he could as Chief of the Air Staff and that he should give way to a younger man. He offered his resignation to the Cabinet in late 1928, although it was not initially accepted. Around the same time as Trenchard was considering his future, the British Legation and some European diplomatic staff based in Kabul

were cut off from the outside world as a result of the civil war in Afghanistan

. After word had reached London, the Foreign Secretary Austen Chamberlain

sent for Trenchard who informed Chamberlain that the RAF would be able to rescue the stranded civilians. The Kabul Airlift

began on Christmas Eve and took nine weeks to rescue around 600 people.

Trenchard continued as Chief of the Air Staff until 1 January 1930. Immediately after he had relinquished his appointment, Trenchard was created Baron

of Wolfeton in the County of Dorset, entering the House of Lords

and becoming the RAF's first peer. Looking back over Trenchard's time as Chief of the Air Staff, while he had successfully preserved the RAF, his emphasis on the Air Force providing defence at a comparatively low cost had led to a stagnation and even deterioration in the quality of the Service's fighting equipment.

, largely disappearing from public life. However, in March 1931, Ramsay MacDonald

asked Trenchard to take the post of Metropolitan Police Commissioner, which after initially declining, Trenchard eventually accepted in October 1931. Trenchard served as head of the Metropolitan Police

until 1935 and during his tenure he instigated several changes. These included limiting membership of the Police Federation

, introducing limited terms of employment and the creation of separate career paths for the lower and higher ranks akin to the military system of officer and non-commissioned career streams. Perhaps Trenchard's most well known achievement during his time as Commissioner was the establishment of the Hendon Police College

which originally was the institution from which Trenchard's junior inspector

s graduated before following a career in the higher ranks. Trenchard retired in November 1935 and in his final few months as Police Commissioner, he was made a knight grand cross of the Royal Victorian Order

.

, Maurice Hankey

who chaired the Committee of Imperial Defence

was angered by Trenchard's intervention. Later that year, when the Government was considering entering into an international treaty which would have banned all bomber aircraft, Trenchard wrote the Cabinet outlining his opposition to the idea. Ultimately the idea was dropped.

Trenchard developed a negative view of Hankey whom he saw as being more interested in maintaining unanimity amongst the service heads than dealing with the weaknesses in British defence arrangements. Trenchard began to speak privately against Hankey who, for his part, had no liking for Trenchard. By 1935, Trenchard privately lobbied for Hankey's removal on the grounds that the nation's security was at stake. Following his departure from the Metropolitan Police, Trenchard was free to speak publicly. In December 1935 Trenchard wrote in The Times that the Committee of Imperial Defence should be placed under the chairmanship of a politician. Hankey responded by accusing Trenchard of "trying to stab him in the back." By 1936, the idea of bolstering the Committee of Imperial Defence had become a popular point of debate and Trenchard presented his arguments in the House of Lords. In the end the Government conceded and Sir Thomas Inskip

was appointed as the Minister for Coordination of Defence

.

With Hankey and his ban on inter-service disputes gone, the Navy once again campaigned for their own air service. The idea of transferring the Fleet Air Arm

from Air Ministry to Admiralty control was raised and although Trenchard opposed the move in the Lords, in the Press and in private conversations, he lacked the influence to prevent the transfer, which took place in 1937. Outside of his political work, Trenchard took on the chairmanship of the United Africa Company

, which had sought out Trenchard because of his West African knowledge and experience. In 1936 Trenchard was upgraded from Baron to Viscount Trenchard

.

From late 1936 to 1939 Trenchard spent much of his time travelling overseas on behalf of the companies who employed him as a director. During one visit to Germany in the summer of 1937, Trenchard was hosted at a dinner by Hermann Göring

, the Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe. Although the evening started in a cordial fashion, it ended with Göring telling Trenchard that "one day German might will make the whole world tremble" and Trenchard replying to Göring that he "must be off his head". In 1937 Newall

was appointed Chief of the Air Staff and Trenchard did not hesitate in criticising the new air chief. As an ardent supporter of the bomber, Trenchard found much to disagree with in the air expansion programme and its emphasis on defensive fighter aircraft. Trenchard took to writing directly to the Cabinet and eventually Newall was reduced to imploring Trenchard to exercise some discretion. Trenchard offered his services to the Government on at least two occasions but they were not accepted.

Just after the outbreak of World War II

Just after the outbreak of World War II

, Chamberlain

summoned Trenchard and offered him the job of organizing advanced training for RAF pilots in Canada

, possibly as a pretext to remove Trenchard from England. Trenchard turned Chamberlain down, saying that the role required a younger man who had up-to-date knowledge of training matters. Trenchard then spent the remainder of 1939 arguing that the RAF should be used to strike against Germany from its bases in France. It was clear to the Government that Trenchard was dissatisfied and early in 1940 he was offered the job of co-ordinating the camouflaging of England. Trenchard flatly refused this job. Without an official role, Trenchard took it upon himself to spend the spring of 1940 visiting many RAF units, including those of the Advanced Air Striking Force in France. In April, Sir Samuel Hoare, who was once again Secretary of State for Air

, unsuccessfully attempted to get Trenchard to come back as Chief of the Air Staff.

In May 1940, after the failure of the Norwegian Campaign

, Trenchard used his position in the Lords to attack what he saw as the Government's half-hearted prosecution of the war. When Churchill replaced Chamberlain as Prime Minister, Trenchard was asked to organize the defence of aircraft factories. Trenchard declined this offer on the grounds that he was not interested in helping the general who already had the responsibility. Towards the end of the month, Churchill offered Trenchard a job that would have seen him acting as a general officer commanding

all British land, air and sea forces at home should an invasion occur. Trenchard responded by bluntly stating that in order to be effective, the officer with such responsibility would need the military powers of a generalissimo

and political power that would come from being Deputy Minister of Defence. Churchill was virtually reduced to apoplexy and did not grant Trenchard the enormous powers he sought.

Notwithstanding their disagreement, Trenchard and Churchill remained on good terms and on Churchill's 66th birthday (30 November 1940) they took lunch at Chequers

. The Battle of Britain

had recently concluded and Churchill was full of praise for Trenchard's pre-War efforts in establishing the RAF. Churchill made Trenchard his last job offer, this time as the reorganizer of Military Intelligence

. Trenchard seriously considered the offer but declined it by letter two days later, chiefly because he felt that the job required a degree of tact which he would have been unable to supply.

From mid-1940 onwards, Trenchard realized that by his rash demands in May he had excluded himself from a pivotal role in the British war effort. He then took it upon himself to act as an unofficial Inspector-General for the RAF, visiting deployed squadrons across Europe and North Africa on morale-raising visits. As a peer, a friend of Churchill's and with direct connections to the Air Staff, Trenchard championed the cause of the Air Force in the Lords, in the Press and with the Government, submitting several secret essays concerning the importance he attached to air power.

From mid-1940 onwards, Trenchard realized that by his rash demands in May he had excluded himself from a pivotal role in the British war effort. He then took it upon himself to act as an unofficial Inspector-General for the RAF, visiting deployed squadrons across Europe and North Africa on morale-raising visits. As a peer, a friend of Churchill's and with direct connections to the Air Staff, Trenchard championed the cause of the Air Force in the Lords, in the Press and with the Government, submitting several secret essays concerning the importance he attached to air power.

Trenchard also continued to exert considerable influence over the Royal Air Force. Acting with Sir John Salmond he quietly but successfully lobbied for the removal of Newall as Chief of the Air Staff and Dowding

as the Command-in-Chief of Fighter Command

. In the Autumn, Newall was replaced by Portal

and Dowding was succeeded by Douglas. Both the new commanders were Trenchard protégés.

During the war, the Trenchard family suffered tragedy. Trenchard's elder stepson John was killed in action in Italy and his younger stepson Edward was killed in a flying accident. His own first-born son, also called Hugh, was killed in North Africa. However, Trenchard's younger son Thomas

did survive the war and frequently visited his parents when he was able.

and Carl Andrew Spaatz, asked Trenchard to brief them in connection with the debate which surrounded the proposed establishment of the independent United States Air Force

. The American air leaders held Trenchard in high esteem and dubbed him the "patron saint of air power". The USAF was formed as an independent branch of the American Armed Forces in 1947.

After World War II, Trenchard continued to set out his ideas about air power. He also supported the creation of two memorials. For the first, the Battle of Britain Chapel

After World War II, Trenchard continued to set out his ideas about air power. He also supported the creation of two memorials. For the first, the Battle of Britain Chapel

in Westminster Abbey

, Trenchard headed a committee with Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding

to raise funds for the furnishing of the chapel and for the provision of a stained glass window. The second, the Anglo-American Memorial to the airmen of both nations, was erected after Trenchard's death in St Paul's Cathedral

. In the late 1940s and early 1950s Trenchard continued his involvement with the United Africa Company, holding the chairmanship until 1953 when he resigned. From 1954, during the last two years of his life, Trenchard was partially blind and physically frail.

Trenchard died one week after his 83rd birthday at his London home in Sloane Avenue on 10 February 1956. Following his funeral at Westminster Abbey on 21 February, his ashes were buried in the Battle of Britain Chapel he helped to create. Trenchard's viscountcy passed to his son Thomas.

's Trenchard Hall, and RAF Cranwell

's Trenchard Hall. Also named after Trenchard are: Trenchard Lines – one of the two sites of British Army Headquarters Land Forces, the small museum

at RAF Halton

, one of the five houses at Welbeck College

which are named after prominent military figures, and Trenchard House, which is currently used by Farnborough Air Sciences Trust

to store part of their collection. In 1977 Trenchard was invested in the International Aerospace Hall of Fame at the San Diego Aerospace Museum

.

Trenchard's work in establishing the RAF and preserving its independence have led to him being described as the Father of the Royal Air Force. For his own part, Trenchard disliked the description, believing that Sir David Henderson deserved the accolade. His obituary in The Times

considered that Trenchard's greatest gift to the RAF was the belief that mastery of the air must be gained and retained through offensive action. During his life, Trenchard strongly argued that the bomber was the key weapon of an air force and he is recognized today as one of the early advocates of strategic bombing and one of the architects of the British policy on imperial policing through air control.

|-

|-

|-

|-

|-

|-

|-

|-

|-

|-

|-

|-

|-

Marshal of the Royal Air Force

Marshal of the Royal Air Force is the highest rank in the Royal Air Force. In peacetime it was granted to RAF officers in the appointment of Chief of the Defence Staff, and to retired Chiefs of the Air Staff, who were promoted to it on their last day of service. Promotions to the rank have ceased...

Hugh Montague Trenchard, 1st Viscount Trenchard GCB OM

Order of Merit

The Order of Merit is a British dynastic order recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture...

GCVO DSO

Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, and formerly of other parts of the British Commonwealth and Empire, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, typically in actual combat.Instituted on 6 September...

(3 February 1873 – 10 February 1956) was a British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

officer who was instrumental in establishing the Royal Air Force

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

. He has been described as the Father of the Royal Air Force.

During his formative years Trenchard struggled academically, failing many examinations and only just succeeding in meeting the minimum standard for commissioned service in the British Army

British Army

The British Army is the land warfare branch of Her Majesty's Armed Forces in the United Kingdom. It came into being with the unification of the Kingdom of England and Scotland into the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1707. The new British Army incorporated Regiments that had already existed in England...

. As a young infantry officer, Trenchard served in India and with the outbreak of the Boer War

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War was fought from 11 October 1899 until 31 May 1902 between the British Empire and the Afrikaans-speaking Dutch settlers of two independent Boer republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State...

, he volunteered for service in South Africa. Whilst fighting the Boers, Trenchard was critically wounded and as a result of his injury, he lost a lung, was partially paralysed and returned to Great Britain. On medical advice Trenchard travelled to Switzerland to recuperate and boredom saw him taking up bobsleighing. After a heavy crash, Trenchard found that his paralysis was gone and that he could walk unaided. Following further recuperation, Trenchard returned to active service in South Africa.

After the end of the Boer War, Trenchard saw service in Nigeria

Nigeria

Nigeria , officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a federal constitutional republic comprising 36 states and its Federal Capital Territory, Abuja. The country is located in West Africa and shares land borders with the Republic of Benin in the west, Chad and Cameroon in the east, and Niger in...

where he was involved in efforts to bring the interior under settled British rule and quell inter-tribal violence. During his time in West Africa, Trenchard commanded the Southern Nigeria Regiment

Southern Nigeria Regiment

The Southern Nigeria Regiment was a British colonial regiment which operated in Nigeria in the early part of the 20th century.The Regiment was formed out of the Niger Coast Protectorate Force and part of the Royal Niger Constabulary...

for several years.

In 1912, Trenchard learned to fly and he was subsequently appointed as second in command of the Central Flying School

Central Flying School

The Central Flying School is the Royal Air Force's primary institution for the training of military flying instructors. Established in 1912 it is the longest existing flying training school.-History:...

. He held several senior positions in the Royal Flying Corps

Royal Flying Corps

The Royal Flying Corps was the over-land air arm of the British military during most of the First World War. During the early part of the war, the RFC's responsibilities were centred on support of the British Army, via artillery co-operation and photographic reconnaissance...

during World War I, serving as the commander of the Royal Flying Corps in France from 1915 to 1917. In 1918, he briefly served as the first Chief of the Air Staff before taking up command of the Independent Air Force

Independent Air Force

The Independent Air Force , also known as the Independent Force or the Independent Bombing Force and later known as the Inter-Allied Independent Air Force, was a World War I strategic bombing force which was part of the British Royal Air Force and used to strike against German railways, aerodromes...

in France. Returning as Chief of the Air Staff under Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

in 1919, Trenchard spent the following decade securing the future of the Royal Air Force

Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force is the aerial warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Formed on 1 April 1918, it is the oldest independent air force in the world...

. He was Metropolitan Police Commissioner in the 1930s and a defender of the RAF in his later years. Trenchard is recognized today as one of the early advocates of strategic bombing

Strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in a total war with the goal of defeating an enemy nation-state by destroying its economic ability and public will to wage war rather than destroying its land or naval forces...

.

Early life

Hugh Montague Trenchard was born at Windsor Lodge on Haines Hill in TauntonTaunton

Taunton is the county town of Somerset, England. The town, including its suburbs, had an estimated population of 61,400 in 2001. It is the largest town in the shire county of Somerset....

, England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

on 3 February 1873. He was the third child and second son of Henry Montague Trenchard and his wife Georgina Louisa Catherine Tower. Trenchard's father was a captain

Captain (British Army and Royal Marines)

Captain is a junior officer rank of the British Army and Royal Marines. It ranks above Lieutenant and below Major and has a NATO ranking code of OF-2. The rank is equivalent to a Lieutenant in the Royal Navy and to a Flight Lieutenant in the Royal Air Force...

in the King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry

The King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry was a regiment of the British Army. It officially existed from 1881 to 1968, but its predecessors go back to 1755. The regiment's traditions and history are now maintained by The Rifles.-The 51st Foot:...

and his mother was the daughter of the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

captain

Captain (Royal Navy)

Captain is a senior officer rank of the Royal Navy. It ranks above Commander and below Commodore and has a NATO ranking code of OF-5. The rank is equivalent to a Colonel in the British Army or Royal Marines and to a Group Captain in the Royal Air Force. The rank of Group Captain is based on the...

John McDowall Skene. Although in the 1870s the Trenchards were living in an unremarkable fashion, their forebears had played notable roles in English history. The family claimed descent from Raoul de Trenchant, a knight and one of the close companions of William the Conqueror who fought alongside him at the Battle of Hastings

Battle of Hastings

The Battle of Hastings occurred on 14 October 1066 during the Norman conquest of England, between the Norman-French army of Duke William II of Normandy and the English army under King Harold II...

. Other notable ancestors were Sir Thomas Trenchard, a High Sheriff of Dorset in the 16th century and Sir John Trenchard

John Trenchard (Secretary of State)

Sir John Trenchard was an English politician belonging to an old Dorset family. His father was Thomas Trenchard of Wolverton , and his grandfather was Sir Thomas Trenchard of Wolverton...

, the Secretary of State under William III

William III of England

William III & II was a sovereign Prince of Orange of the House of Orange-Nassau by birth. From 1672 he governed as Stadtholder William III of Orange over Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel of the Dutch Republic. From 1689 he reigned as William III over England and Ireland...

.

When Hugh Trenchard was two, the family moved to Courtlands, a farm-cum-manor house less than three miles (4 km) from the centre of Taunton. The country setting meant that the young Trenchard could enjoy an outdoor life, including spending time hunting rabbits and other small animals with the rifle he was given on his eighth birthday. It was during his junior years that Trenchard and his siblings were educated at home by a resident tutor, whom Trenchard did not respect. Unfortunately for Trenchard's education, the tutor was neither strict enough nor skillful enough to overcome the children's mischievous attempts to avoid receiving instruction. As a consequence, Trenchard did not excel academically; however, his enthusiasm for games and riding

Equestrianism

Equestrianism more often known as riding, horseback riding or horse riding refers to the skill of riding, driving, or vaulting with horses...

was evident.

.jpg)

Botley, Hampshire

Botley is a historic village in Hampshire, England that obtained a charter for a market from Henry III in 1267. The area has been settled since at least the 10th century....

in Hampshire

Hampshire

Hampshire is a county on the southern coast of England in the United Kingdom. The county town of Hampshire is Winchester, a historic cathedral city that was once the capital of England. Hampshire is notable for housing the original birthplaces of the Royal Navy, British Army, and Royal Air Force...

. Although he did well at arithmetic, he struggled with the rest of the curriculum. However, Trenchard's parents were not greatly concerned by his educational difficulties, believing that it would be no impediment to him following a military career. Georgina Trenchard wanted her son to follow her father's profession and enter the Royal Navy. In 1884, Trenchard was moved to Dover where he attended Hammond's, a cramming school

Cram school

Cram schools are specialized schools that train their students to meet particular goals, most commonly to pass the entrance examinations of high schools or universities...

for prospective entrants to HMS Britannia

Britannia Royal Naval College

Britannia Royal Naval College is the initial officer training establishment of the Royal Navy, located on a hill overlooking Dartmouth, Devon, England. While Royal Naval officer training has taken place in the town since 1863, the buildings which are seen today were only finished in 1905, and...

. Trenchard failed the Navy's entrance papers, and at the age of 13 he was sent to the Reverend Albert Pritchard's crammer, Hill Lands in Wargrave

Wargrave

Wargrave is a large village and civil parish in the English county of Berkshire, which encloses the confluence of the River Loddon and the River Thames. It is in the Borough of Wokingham...

, Berkshire

Berkshire

Berkshire is a historic county in the South of England. It is also often referred to as the Royal County of Berkshire because of the presence of the royal residence of Windsor Castle in the county; this usage, which dates to the 19th century at least, was recognised by the Queen in 1957, and...

. Hill Lands prepared its pupils for Army commissions and although Trenchard excelled at rugby

Rugby football

Rugby football is a style of football named after Rugby School in the United Kingdom. It is seen most prominently in two current sports, rugby league and rugby union.-History:...

, as before he did not apply himself to his studies.

In 1889, when Hugh Trenchard was 16 years old, his father, who had become a solicitor

Solicitor

Solicitors are lawyers who traditionally deal with any legal matter including conducting proceedings in courts. In the United Kingdom, a few Australian states and the Republic of Ireland, the legal profession is split between solicitors and barristers , and a lawyer will usually only hold one title...

, was declared bankrupt. After initially being removed from Hill Lands, the young Trenchard was only able to return thanks to the charity of his relatives. Trenchard failed the Woolwich examinations twice and was then relegated to applying for the Militia

Militia (United Kingdom)

The Militia of the United Kingdom were the military reserve forces of the United Kingdom after the Union in 1801 of the former Kingdom of Great Britain and Kingdom of Ireland....

which had lower entry standards. Even the Militia's examinations proved difficult for Trenchard and he failed in 1891 and 1892. During this time, Trenchard underwent a period of training as a probationary subaltern with the Forfar and Kincardine Artillery

Forfar and Kincardine Artillery

The Forfar and Kincardine Artillery was a British artillery militia regiment of the 19th century. It was based in and named after Forfarshire and Kincardineshire in Scotland....

. Following his return to Pritchard's, Trenchard finally achieved a bare pass in March 1893. At the age of 20, he was gazetted

London Gazette

The London Gazette is one of the official journals of record of the British government, and the most important among such official journals in the United Kingdom, in which certain statutory notices are required to be published...

as a second-lieutenant in the Second Battalion of the Royal Scots Fusiliers

Royal Scots Fusiliers

-The Earl of Mar's Regiment of Foot :The regiment was raised in Scotland in 1678 by Stuart loyalist Charles Erskine, de jure 5th Earl of Mar for service against the rebel covenanting forces during the Second Whig Revolt . They were used to keep the peace and put down brigands, mercenaries, and...

and posted to India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

.

India

Trenchard arrived in India in late 1893, joining his regiment at SialkotSialkot

Sialkot is a city in Pakistan situated in the north-east of the Punjab province at the foothills of snow-covered peaks of Kashmir near the Chenab river. It is the capital of Sialkot District. The city is about north-west of Lahore and only a few kilometers from Indian-controlled Jammu.The...

in the Punjab

Punjab (British India)

Punjab was a province of British India, it was one of the last areas of the Indian subcontinent to fall under British rule. With the end of British rule in 1947 the province was split between West Punjab, which went to Pakistan, and East Punjab, which went to India...

. Not long after his arrival, Trenchard was called upon to make a speech at a mess

Mess

A mess is the place where military personnel socialise, eat, and live. In some societies this military usage has extended to other disciplined services eateries such as civilian fire fighting and police forces. The root of mess is the Old French mes, "portion of food" A mess (also called a...

dinner night

Dining in

Dining in is a formal military ceremony for members of a company or other unit, which includes a dinner, drinking, and other events to foster camaraderie and esprit de corps....

. It was common practice for the youngest subaltern to make such a speech and Trenchard was expected to cover several highlights of the Royal Scots Fusiliers' history. Instead, he simply said "I am deeply proud to belong to this great regiment", followed by "I hope one day I shall live to command it." His 'speech' was received with hoots of incredulous laughter, although some appreciated his nerve.

Young officers stationed in India in the 1890s enjoyed many social and sporting diversions and Trenchard did little militarily. While every regiment was required to undertake a period of duty beyond the Khyber Pass

Khyber Pass

The Khyber Pass, is a mountain pass linking Pakistan and Afghanistan.The Pass was an integral part of the ancient Silk Road. It is mentioned in the Bible as the "Pesh Habor," and it is one of the oldest known passes in the world....

, for the most part conditions of peace and prosperity were evident and Trenchard was able to engage in various sporting activities. In early 1894 he won the All-India Rifle Championship. After his success at shooting, Trenchard set about establishing a battalion polo

Polo

Polo is a team sport played on horseback in which the objective is to score goals against an opposing team. Sometimes called, "The Sport of Kings", it was highly popularized by the British. Players score by driving a small white plastic or wooden ball into the opposing team's goal using a...

team. Being of the infantry, his regiment had no history of playing polo and there were many obstacles for Trenchard to overcome. However, within six months the battalion polo team was competing and holding its own. It was during a polo match in 1896 that Trenchard first met Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, was a predominantly Conservative British politician and statesman known for his leadership of the United Kingdom during the Second World War. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest wartime leaders of the century and served as Prime Minister twice...

, with whom he clashed on the field of play. Trenchard's sporting prowess saved his reputation amongst his fellow officers. In other respects he did not fit in; lacking social graces and choosing to converse little, he was nicknamed "the camel", as like the beast he neither drank nor spoke.

It was also during Trenchard's time in India that he took up reading. His first choice was for biographies, particularly of British heroes. Trenchard kept the long hours he spent reading quiet, but in so doing succeeded in providing himself with an education where the service crammers had failed. However, in military terms Trenchard was dissatisfied. He failed to see any action during his time in India, missing out on his regiment's turn at the frontier, as he was in England on sick leave for a hernia

Hernia

A hernia is the protrusion of an organ or the fascia of an organ through the wall of the cavity that normally contains it. A hiatal hernia occurs when the stomach protrudes into the mediastinum through the esophageal opening in the diaphragm....

operation.

With the outbreak of the Second Boer War

Second Boer War

The Second Boer War was fought from 11 October 1899 until 31 May 1902 between the British Empire and the Afrikaans-speaking Dutch settlers of two independent Boer republics, the South African Republic and the Orange Free State...

in October 1899, Trenchard applied several times to rejoin his old battalion which had been sent to the Cape

Cape Colony

The Cape Colony, part of modern South Africa, was established by the Dutch East India Company in 1652, with the founding of Cape Town. It was subsequently occupied by the British in 1795 when the Netherlands were occupied by revolutionary France, so that the French revolutionaries could not take...

as part of the expeditionary corps. Trenchard's requests were rejected by his Colonel, and when the Viceroy Lord Curzon

George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, KG, GCSI, GCIE, PC , known as The Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and as The Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman who was Viceroy of India and Foreign Secretary...

, who was concerned about the drain of leaders to South Africa, banned the dispatch of any further officers, Trenchard's prospects for seeing action looked bleak. However, a year or two previously, it had so happened that Trenchard had been promised help or advice from Sir Edmond Elles

Edmond Elles

Lieutenant-General Sir Edmond Roche Elles KCB GCIE was a British Army officer who served in Egypt and India during the late 19th century and early 20th century.-External links:*...

, as a gesture of thanks after Trenchard had rescued a poorly planned rifle-shooting contest from disaster. By 1900, Elles was Military Secretary to Lord Curzon and Trenchard (recently promoted to captain

Captain (British Army and Royal Marines)

Captain is a junior officer rank of the British Army and Royal Marines. It ranks above Lieutenant and below Major and has a NATO ranking code of OF-2. The rank is equivalent to a Lieutenant in the Royal Navy and to a Flight Lieutenant in the Royal Air Force...

) sent a priority signal to Elles requesting that he be permitted to rejoin his unit overseas. This bold move worked, and Trenchard received his orders for South Africa