Freedom of religion

Encyclopedia

Freedom of religion is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion

or belief

in teaching

, practice, worship

, and observance; the concept is generally recognized also to include the freedom to change religion

or not to follow any religion

. The freedom to leave or discontinue membership in a religion or religious group —in religious terms called "apostasy

" —is also a fundamental part of religious freedom, covered by Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

.

Freedom of religion is considered by many people and nations to be a fundamental

human right.

In a country with a state religion

, freedom of religion is generally considered to mean that the government permits religious practices of other sects besides the state religion, and does not persecute

believers in other faiths.

or the Muslim

tradition of dhimmi

s, literally "protected individuals" professing an officially tolerated non-Muslim religion.

In Antiquity

In Antiquity

a syncretic

point-of-view often allowed communities of traders to operate under their own customs. When street mobs of separate quarters clashed in a Hellenistic or Roman

city, the issue was generally perceived to be an infringement of community rights.

Cyrus the Great

established the Achaemenid Empire

ca. 550 BC, and initiated a general policy of permitting religious freedom throughout the empire, documenting this on the Cyrus Cylinder

.

Some of the historical exceptions have been in regions where one of the revealed religions has been in a position of power: Judaism

, Zoroastrianism

, Christianity

and Islam

. Others have been where the established order has felt threatened, as shown in the trial of Socrates

in 399 BC or where the ruler has been deified, as in Rome, and refusal to offer token sacrifice

was similar to refusing to take an oath of allegiance

. This was the core for resentment and the persecution of early Christian communities

.

Freedom of religious worship was established in the Buddhist Maurya Empire

of ancient India

by Asoka the Great in the 3rd century BC, which was encapsulated in the Edicts of Ashoka

.

Greek-Jewish clashes at Cyrene

in 73 AD and 117 AD and in Alexandria

in 115 AD provide examples of cosmopolitan cities as scenes of tumult.

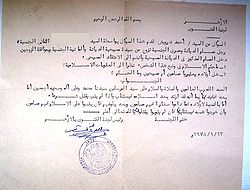

(then known as Yathrib), religious freedom for Muslim

s, Jews and pagans

was declared by Muhammad

in the Constitution of Medina

. The Islamic Caliphate

later guaranteed religious freedom under the conditions that non-Muslim communities accept dhimmi

(protected) status and their adult males pay the jizya

tax as a substitute for the zakat

paid by Muslim citizens. Jews and Christians were alternately toleratedand persecuted, the most notable examples of the latter being the conquest of Islamic Spain by fundamentalist groups from north Africa (the Almoravids

, followed by the Almohads from the mid-12th century). Persecution of non-Muslims caused the emigration of many Jews (and Christians) into the northern, Christian states.

Religious pluralism

existed in classical Islamic ethics

and Sharia

law, as the religious law

s and court

s of other religions, including Christianity

, Judaism

and Hinduism

, were usually accommodated within the Islamic legal framework, as seen in the early Caliphate

, Al-Andalus

, Indian subcontinent

, and the Ottoman Millet

system. In medieval Islamic societies, the qadi

(Islamic judges) usually could not interfere in the matters of non-Muslims unless the parties voluntarily choose to be judged according to Islamic law, thus the dhimmi communities living in Islamic state

s usually had their own laws independent from the Sharia law, such as the Jews who would have their own Halakha

courts.

Dhimmis were allowed to operate their own courts following their own legal systems in cases that did not involve other religious groups, or capital offences or threats to public order. Non-Muslims were allowed to engage in religious practices that was usually forbidden by Islamic law, such as the consumption of alcohol

and pork

, as well as religious practices which Muslims found repugnant, such as the Zoroastrian

practice of incest

uous "self-marriage" where a man could marry his mother, sister or daughter. According to the famous Islamic legal scholar Ibn Qayyim (1292–1350), non-Muslims had the right to engage in such religious practices even if it offended Muslims, under the conditions that such cases not be presented to Islamic Sharia courts and that these religious minorities believed that the practice in question is permissible according to their religion.

in other parts of the world including Christians, Jews, Bahá'i and Zoroastrians fled to India as a place of refuge to enjoy religious freedom. This had been the underlying attitude of most rulers of India

from time immemorial.

Ancient Jews

fleeing from persecution in their homeland 2,500 years ago settled in India

and never faced anti-Semitism

. Freedom of religion edicts have been found written during Ashoka the Great's reign in the 3rd century BC. Freedom to practise, preach and propagate any religion is a constitutional right in Modern India

. Most major religious festivals of the main communities are included in the list of national holidays.

India is an 80% Hindu

country, yet its prime minister

is a Sikh

(Manmohan Singh

), the chairperson of the ruling alliance

is a Catholic woman of Italian

birth (Sonia Gandhi

), and three out of the twelve presidents of India have been Muslims. Further, the current Chief Election Commissioner of India

is a Muslim,as are many successful Indians including film stars,artists,religious scholars,industrialists etc. Still, though some argue that India

's predominant religion, Hinduism

, has long been among the most tolerant of religions, others assert that tolerance only appeared in India with the emergence of the modern Republic of India as a secular nation in 1947.

The Dalai Lama

, the Tibetan leader in exile said that religious tolerance of ‘Aryabhoomi,’ a reference to India found in Mahabharata, has been in existence in this country from thousands of years. “Not only Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, Sikhism which are the native religions but also Christianity and Islam have flourished here. Religious tolerance is inherent in Indian tradition,’’ Dalai Lama said.

Freedom of religion in the Indian subcontinent

is exemplified by the reign of King Piyadasi (304 BC to 232 BC) (Asoka). One of King Asoka's main concerns was to reform governmental institutes and exercise moral principles in his attempt to create a just and humane society

. Later he promoted the principles of Buddhism

, and the creation of a just, understanding and fair society was held as an important principle for many ancient rulers of this time in the East.

The importance of freedom of worship in India was encapsulated in an inscription of Asoka:

The initial entry of Islam

into South Asia

came in the first century after the death of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad

. When around 1210 AD the Islamic Sultanates

invaded India from the north-west, gradually the principle of freedom of religion deteriorated in this part of the world. They were subsequently replaced by another Islamic invader in the form of Babur

. The Mughal

empire was founded by the Mongol leader Babur

in 1526, when he defeated Ibrahim Lodi, the last of the Delhi Sultans

at the First Battle of Panipat

. The word "Mughal" is the Indo-Iranian version of Mongol.

On the main Asian continent, the Mongols were tolerant of religions. People could worship as they wished freely and openly, though the formation of 2 nations i.e. Pakistan and Bangladesh has been on basis of religious intolerance.

After arrival of Europeans, Christians in zeal to convert local as per belief in conversion as service of God, have also been seen to fall into frivolous methods since their arrival. Though by and large there are hardly any reports of law and order disturbance from mobs with Christian beliefs except perhaps in the north eastern region of India.

The rise of the BJP political party and the emergence of Hindu nationalism

have been accompanied by the repression of Christianity and in some cases assaults on Christians and their institutions. The worst of these happened in August 2008 when 4,640 houses and 252 churches were torched in Kandhamal. 54,000 people were made homeless by the violence. Attacks continue and in November 2010 Hindutva

extremists atacked Christian homes in Peliguda, Kenduguda and Telarai villages in Orissa state: Christians say they were attacked for refusing to contribute to the local Durga Puja

celebrations. Freedom of religion in contemporary India is a fundamental right guaranteed under Article 25 of the nation's constitution. Accordingly every citizen of India has a right to profess, practice and propagate their religions peacefully. Vishwa Hindu Parishad counters this argument by saying that evangelical Christians are forcefully (or through money) converting rural, illiterate populations and they are only trying to stop this.

In September 2010, Indian state Kerala's State Election Commissioner announced that "Religious heads cannot issue calls to vote for members of a particular community or to defeat the nonbelievers". The Catholic Church comprising Latin, Syro-Malabar and Syro-Malankara rites used to give clear directions to the faithful on exercising their franchise during elections through pastoral letters issued by bishops or council of bishops. The pastoral letter issued by Kerala Catholic Bishops’ Council (KCBC) on the eve of the poll urged the faithful to shun atheists.

Even today, most Indians celebrate all religious festivals with equal enthusiasm and respect. Hindu

festivals like Deepavali and Holi

, Muslim

festivals like Mahanabi Jayanti

, Christian festivals like Christmas

and other festivals like Buddha Purnima, Mahavir Jayanti

, Gur Purab etc. are celebrated and enjoyed by all Indians

.

kept a tight rein on religious expression throughout the Middle Ages

, basing its principles on the Bible and on the Gospel. Jews were alternately tolerated and persecuted, the most notable examples of the latter being the expulsion of all Jews

from Spain in 1492. Some of those who remained and converted were tried as heretics in the Inquisition

for allegedly practicing Judaism in secret. Despite the persecution of Jews, they were the most tolerated non-Catholic faith in Europe.

However, the latter was in part a reaction to the growing movement that became the Reformation

. As early as 1380, John Wycliffe

in England denied transubstantiation

and began his translation of the Bible into English. He was condemned in a Papal Bull

in 1410, and all his books were burned.

In 1414 Jan Hus

, a Bohemia

n preacher of reformation, was given a safe conduct by the Holy Roman Emperor to attend the Council of Constance

. Not entirely trusting in his safety, he made his will before he left. His forebodings proved accurate, and he was burned at the stake on 6 July 1415. The Council also decreed that Wycliffe's remains be disinterred and cast out. This decree was not carried out until 1429.

After the fall of the city of Granada

Spain in 1492 the Muslim population was promised religious freedom by the Treaty of Granada, but that promise was short-lived. In 1501 Granada's Muslims were given an ultimatum to either convert to Christianity or to emigrate. The majority converted, but only superficially, continuing to dress and speak as they had before and to secretly practice Islam

. The Morisco

s (converts to Christianity) were ultimately expelled from Spain

between 1609 (Castile) and 1614 (rest of Spain), by Philip III.

Martin Luther

published his famous 95 Theses in Wittenberg

on 31 October 1517. His major aim was theological, summed up in the three basic dogmas of Protestantism: • The Bible only is infallible • Every Christian can interpret it • Human sins are so wrongful that no deed or merit, only God's grace, can lead to salute. In consequence, Luther hoped to stop the sale of indulgence

s and to reform the Church from within, but this could not succeed, as his doctrine meant the end of the clergy and of the Pope. In 1521 he was given the chance to recant at the Diet of Worms

before Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

, then only 19. After he refused to recant he was declared heretic. Partly for his own protection, he was sequestered on the Wartburg

in the possessions of Frederick III, Elector of Saxony

, where he translated the New Testament

into German. He was excommunicated by Papal Bull in 1521.

The Protestant movement, however, continued to gain ground in his absence and spread to Switzerland

. Huldrych Zwingli

preached reform in Zürich

from 1520 to 1523. He opposed the sale of indulgences, celibacy, pilgrimages, pictures, statues, relics, altars, and organs. This culminated in outright war between the Swiss canton

s that accepted Protestantism and the Catholics. The Catholics were victorious, and Zwingli was killed in battle in 1531. The Catholic cantons were magnanimous in victory.

Meanwhile, Luther's idea had been interpreted radically by the leaders of the German Peasants' War

, and Luther himself assisted the German princes in slaughtering these revolutionaries.

The defiance of Papal authority proved contagious, and in 1533, when Henry VIII of England

was excommunicated for his divorce and remarriage to Anne Boleyn, he promptly established a state church with bishops appointed by the crown. This was not without internal opposition, and Thomas More

, who had been his Lord Chancellor, was executed in 1535 for opposition to Henry.

In 1535 the Swiss canton of Geneva

became Protestant. In 1536 the Bernese imposed the reformation on the canton of Vaud

by conquest. They sacked the cathedral in Lausanne

and destroyed all its art and statuary. John Calvin

, who had been active in Geneva was expelled in 1538 in a power struggle, but he was invited back in 1540.

The same kind of seesaw back and forth between Protestantism and Catholicism was evident in England when Mary I of England

The same kind of seesaw back and forth between Protestantism and Catholicism was evident in England when Mary I of England

returned that country briefly to the Catholic fold in 1553 and persecuted Protestants. However, her half-sister, Elizabeth I of England

was to restore the Church of England

in 1558, this time permanently, and began to persecute Catholics again. The King James Bible commissioned by King James I of England

and published in 1611 proved a landmark for Protestant worship, with official Catholic forms of worship being banned.

In France, although peace was made between Protestants and Catholics at the Treaty of Saint Germain in 1570, persecution continued, most notably in the Massacre of Saint Bartholomew's Day on 24 August 1572, in which thousands of Protestants throughout France were killed. A few years before, at the "Michelade" of Nîmes in 1567, Protestants had massacred the local Catholic clergy.

The Norman Kingdom of Sicily

The Norman Kingdom of Sicily

under Roger II

was characterized by its multi-ethnic nature and religious tolerance. Normans, Jews, Muslim Arabs, Byzantine Greeks, Lombards and "native" Sicilians lived in harmony. Rather than exterminate the Muslims of Sicily, Roger II's grandson Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen

(1215—1250) allowed them to settle on the mainland and build mosques. Not least, he enlisted them in his — Christian — army and even into his personal bodyguards.

Bohemia (present-day Czech Republic

) enjoyed religious freedom between 1436 and 1520, and became one of the most liberal countries of the Christian world during that period of time. The so-called Basel Compacts of 1436 declared the freedom of religion and peace between Catholics and Utraquists

. In 1609 Emperor Rudolf II granted Bohemia greater religious liberty with his Letter of Majesty. The privileged position of the Catholic Church in the Czech kingdom was firmly established after the Battle of White Mountain

in 1620. Gradually freedom of religion in Bohemian lands

came to an end and Protestants fled or were expelled from the country. A devout Catholic, Emperor Ferdinand II

forcibly converted Austrian and Bohemian Protestants.

In the meantime, in Germany Philip Melanchthon drafted the Augsburg Confession

as a common confession for the Lutherans and the free territories. It was presented to Charles V in 1530.

In the Holy Roman Empire

, Charles V

agreed to tolerate Lutheranism in 1555 at the Peace of Augsburg

. Each state was to take the religion of its prince, but within those states, there was not necessarily religious tolerance. Citizens of other faiths could relocate to a more hospitable environment.

In France, from the 1550s, many attempts to reconcile Catholics and Protestants and to establish tolerance failed because the State was too weak to enforce them. It took the victory of the converted Protestant prince Henry IV of France

, and his accession to the throne, to impose religious tolerance formalized in the Edict of Nantes

in 1598. It would remain in force for over 80 years until its revocation in 1685 by Louis XIV of France

. Intolerance remained the norm until Louis XVI, who signed the Edict of Versailles (1787), then the constitutional text of 24 December 1789, granting civilian rights to Protestants. The French Revolution

then abolished state religion and confiscated all Church property, turning intolerance against Catholics.

n Diet

of Turda

declared free practice of both the Catholic

and Lutheran

religions, but prohibited Calvinism

. Ten years later, in 1568, the Diet extended the freedom to all religions, declaring that "It is not allowed to anybody to intimidate anybody with captivity or expelling for his religion". However it was more than a religious tolerance, it declared the equality of the religions. The emergence in social hierarchy wasn't depend on the religion of the person thus Transylvania had also Catholic and Protestant monarchs (Princes). The lack of state religion was very unique for centuries in Europe. Therefore the Edict of Turda is considered by mostly Hungarian historians as the first legal guarantee of religious freedom in the Christian Europe.

In the Union of Utrecht

(20 January 1579) personal freedom of religion was declared in the struggle between the Northern Netherlands and Spain. The Union of Utrecht was an important step in the establishment of the Dutch Republic (from 1581 to 1795). The establishment of a Jewish community in the Netherlands and New Amsterdam (present-day New York) during the Dutch republic is an example of the freedom of religion. When New Amsterdam surrendered to the English in 1664, the freedom of religion was guaranteed in the Articles of Capitulation.

Intolerance of dissident forms of Protestantism also continued, as evidenced by the exodus of the Pilgrims who sought refuge, first in the Netherlands

, and ultimately in America, founding the Plymouth Colony

in Massachusetts

in 1620. William Penn

, the founder of Philadelphia, was involved in a case which had a profound effect upon future American law and those of England. In a classic case of jury nullification

the jury refused to convict William Penn of preaching a Quaker sermon, which was illegal. Even though the jury was imprisoned for their acquittal, they stood by their decision and helped establish the freedom of religion.

Contrary to a common belief, Protestantism did not mean more freedom of religion. Wherever Protestants took power, they persecuted and eliminated Catholics. In early modern Europe, lasting cases of religious tolerance could be found only in parts of the Austrian empire, in France after the Edict of Nantes

, and in Poland.

Poland has a long tradition of religious freedom. The right to worship freely was a basic right given to all inhabitants of the Commonwealth throughout the 15th and early 16th century, however, complete freedom of religion was officially recognized in Poland in 1573 during the Warsaw Confederation. Poland kept religious freedom laws during an era when religious persecution was an everyday occurrence in the rest of Europe.

The General Charter of Jewish Liberties known as the Statute of Kalisz

was issued by the Duke of Greater Poland

Boleslaus the Pious on 8 September 1264 in Kalisz

. The statute served as the basis for the legal position of Jews in Poland and led to creation of the Yiddish-speaking autonomous Jewish nation until 1795. The statute granted exclusive jurisdiction of Jewish courts over Jewish matters and established a separate tribunal for matters involving Christians and Jews. Additionally, it guaranteed personal liberties and safety for Jews including freedom of religion, travel, and trade. The statute was ratified by subsequent Polish Kings: Casimir III of Poland

in 1334, Casimir IV of Poland in 1453 and Sigismund I of Poland

in 1539. The Commonwealth set a precedent by allowing Jews to become ennobled.

Most of the early colonies were generally not tolerant of dissident forms of worship, with Maryland being the only exception. For example, Roger Williams

found it necessary to found a new colony in Rhode Island

to escape persecution in the theocratically dominated colony of Massachusetts. The Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony

were the most active of the New England persecutors of Quakers, and the persecuting spirit was shared by the Plymouth Colony

and the colonies along the Connecticut river

. In 1660, one of the most notable victims of the religious intolerance was English Quaker Mary Dyer

who was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony. As one of the four executed Quakers known as the Boston martyrs

, the hanging of Dyer on the Boston gallows marked the beginning of the end of the Puritan theocracy

and New England independence from English rule, and in 1661 King Charles II

explicitly forbade Massachusetts from executing anyone for professing Quakerism.

Another notable example of religious persecution by Puritans in Massachusetts was the Salem witch trials

in 1692 and 1693. Thirty-one witchcraft trials were held, convicting twenty-nine people of the capital felony of witchcraft. Nineteen of the accused, fourteen women and five men, were hanged. One man who refused to enter a plea was crushed to death under heavy stones in an attempt to force him to do so.

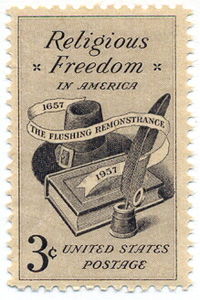

Freedom of religion was first applied as a principle of government in the founding of the colony of Maryland, founded by the Catholic Lord Baltimore

, in 1634. Fifteen years later (1649) the Maryland Toleration Act

, drafted by Lord Baltimore, provided: "No person or persons...shall from henceforth be any waies troubled, molested or discountenanced for or in respect of his or her religion nor in the free exercise thereof." The Maryland Toleration Act was repealed with the assistance of Protestant assemblymen and a new law barring Catholics from openly practicing their religion was passed. In 1657, the Catholic Lord Baltimore regained control after making a deal with the colony's Protestants, and in 1658 the Act was again passed by the colonial assembly. This time, it would last more than thirty years, until 1692, when after Maryland's Protestant Revolution of 1689, freedom of religion was again rescinded. In addition in 1704, an Act was passed "to prevent the growth of Popery in this Province", preventing Catholics from holding political office. Full religious toleration

would not be restored in Maryland until the American Revolution

, when Maryland's Charles Carroll of Carrollton

signed the American Declaration of Independence.

Reiterating Maryland's earlier colonial legislation, the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom

, written in 1779 by Thomas Jefferson

, proclaimed:

Those sentiments also found expression in the First Amendment

of the national constitution, part of the United States' Bill of Rights

:

The United States formally considers religious freedom in its foreign relations. The International Religious Freedom Act of 1998

established the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom

which investigates the records of over 200 other nations with respect to religious freedom, and makes recommendations to submit nations with egregious records to ongoing scrutiny and possible economic sanctions. Many human rights organizations have urged the United States to be still more vigorous in imposing sanctions on countries that do not permit or tolerate religious freedom.

is a constitutionally protected right, allowing believers the freedom to assemble and worship without limitation or interference.

, which bills itself as the largest association of freethinkers (atheists, agnostics and skeptics) in the United States, argue that "Freedom From Religion" is a right in the United States

that is guaranteed by the U.S. constitution

. Critics of atheism respond, "The Constitution guarantees freedom of religion, not freedom from religion."

, in his book The Wealth of Nations

, (using an argument first put forward by his friend and contemporary David Hume

) states that in the long run it is in the best interests of society as a whole and the civil magistrate

(government) in particular to allow people to freely choose their own religion as it helps prevent civil unrest and reduces intolerance

. So long as there are enough different religions and/or religious sects operating freely in a society then they are all compelled to moderate their more controversial and violent teachings, so as to be more appealing to more people and so have an easier time attracting new converts. It is this free competition amongst religious sects for converts that ensures stability and tranquillity in the long run.

Smith also points out that laws that prevent religious freedom and seek to preserve the power and believe in a particular religion will, in the long run, only serve to weaken and corrupt that religion. As its leaders and preachers become complacent, disconnected and unpractised in their ability to seek and win over new converts.

Smith also points out that laws that prevent religious freedom and seek to preserve the power and believe in a particular religion will, in the long run, only serve to weaken and corrupt that religion. As its leaders and preachers become complacent, disconnected and unpractised in their ability to seek and win over new converts.

is one of the more open-minded religions when it comes to religious freedom. It respects the right of everyone to reach God

in their own way. Hindus believe in different ways to preach attainment of God

and religion

as a philosophy

and hence respect all religions as equal. One of the famous Hindu

sayings about religion is: "Truth is one; sages call it by different names."

According to the Catholic Church in Dignitatis Humanae

According to the Catholic Church in Dignitatis Humanae

, "the human person has a right to religious freedom," which is described as "immunity from coercion in civil society." This principle of religious freedom "leaves untouched traditional Catholic doctrine on the moral duty of men and societies toward the true religion." In addition, this right "is to be recognized in the constitutional law whereby society is governed and thus it is to become a civil right."

Previous to this Vatican II message, Pope Pius IX

had written in his Syllabus of Errors

: "[It is an error to say that] Every man is free to embrace and profess that religion which, guided by the light of reason, he shall consider true" (15); "[It is an error to say that] In the present day it is no longer expedient that the Catholic religion should be held as the only religion of the State, to the exclusion of all other forms of worship" (77); "[It is an error to say that] Hence it has been wisely decided by law, in some Catholic countries, that persons coming to reside therein shall enjoy the public exercise of their own peculiar worship" (78).

Some Orthodox Christians, especially those living in democratic countries, support religious freedom for all, as evidenced by the position of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Many Protestant Christian churches, including some Baptists, Churches of Christ

, Seventh-day Adventist Church

and main line churches have a commitment to religious freedoms. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints also affirms religious freedom.

However others, such as African scholar Makau Mutua, have argued that Christian insistence on the propagation of their faith to native cultures as an element of religious freedom has resulted in a corresponding denial of religious freedom to native traditions and led to their destruction. As he states in the book produced by the Oslo Coalition on Freedom of Religion or Belief — "Imperial religions have necessarily violated individual conscience and the communal expressions of Africans and their communities by subverting African religions."

Joel Spring

writes about the Christianization of the Roman Empire

, "Christianity added a new impetus to the expansion of empire. Increasing the arrogance of the imperial project, Christians insisted that the Gospels of the Church were the only valid source of religious beliefs. By the 5th century, Christianity was thought of as co-extensive with the Imperium Romanum. This meant that to be human, as opposed to being a natural slave, was to be "civilized" and Christian. Historian Anthony Pagden

argues, 'just as the civitas; had now become coterminous with Christianity, so to be human—to be, that is, one who was "civil." and who was able to interpret correctly the law of nature—one had now also to be Christian.

"After the fifteenth century, most European colonialists

rationalized the spread of empire with the belief that they were saving a barbaric and pagan world by spreading Christian civilization."

In the Portuguese

and Spanish colonization of the Americas

the policy of Indian Reductions

and Jesuit Reductions

resulted in forced conversions of indigenous peoples of the Americas

from their long practiced spiritual

and religious traditions

and theological

beliefs. The actual population of indigenous peoples, congregations of neophytes and the untouched, plummeted from unintended consequences of missionary Christianity's contacts.

), but Muslims are forbidden to convert from Islam

to another religion (cf. Apostasy in Islam). Certain Muslim-majority countries are known for their restrictions on religious freedom, highly favoring Muslim citizens over non-Muslim citizens. Other countries, having the same restrictive laws, tend to be more liberal when imposing them. Even other Muslim-majority countries are secular and thus do not regulate religious belief.

Some Islamic theologians quote the Qur'an

( and , i.e. Sura Al-Kafirun) to show scriptural support for religious freedom.

, referring to the war against Pagans during the Battle of Badr

in Medina

, indicates that Muslims are only allowed to fight against those who intend to harm them (right of self-defense) and that if their enemies surrender, they must also stop because God does not like those who transgress limits.

In Bukhari:V9 N316, Jabir ibn 'Abdullah narrated that a Bedouin accepted Islam and then when he got a fever he demanded that Muhammad

to cancel his pledge (allow him to renounce Islam). Muhammad refused to do so. The Bedouin man repeated his demand once, but Muhammad once again refused. Then, he (the Bedouin) left Medina. Muhammad said, "Madinah is like a pair of bellows (furnace): it expels its impurities and brightens and clear its good." In this narration, there was no evidence demonstrating that Muhammad ordered the execution of the Bedouin for wanting to renounce Islam.

In addition, , which is believed to be God's final revelation to Muhammad, states that Muslims are to fear God and not those who reject Islam, and states that one is accountable only for one's own actions. Therefore, it postulates that in Islam, in the matters of practising a religion, it does not relate to a worldly punishment, but rather these actions are accountable to God in the afterlife

. Thus, this supports the argument against the execution of apostates in Islam.

However, on the other hand, some Muslims support the practice of executing apostates who leave Islam, as in Bukhari:V4 B52 N260; "The Prophet said, 'If a Muslim discards his religion, kill him.'"

In Iran

, the constitution recognizes four religions whose status is formally protected: Zoroastrianism, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

The constitution, however, also set the groundwork for the institutionalized persecution of Bahá'ís

,

who have been subjected to arrests, beatings, executions, confiscation and destruction of property, and the denial of civil rights and liberties, and the denial of access to higher education. There is no freedom of conscience in Iran, as converting from Islam to any other religion is forbidden.

In Egypt

, a 16 December 2006 judgment of the Supreme Administrative Council

created a clear demarcation between recognized religions — Islam, Christianity and Judaism — and all other religious beliefs; no other religious affiliation is officially admissible.

The ruling leaves members of other religious communities, including Bahá'ís, without the ability to obtain the necessary government documents to have rights in their country, essentially denying them of all rights of citizenship.

They cannot obtain ID cards, birth certificates, death certificates, marriage or divorce certificates, and passports; they also cannot be employed, educated, treated in public hospitals or vote, among other things. See Egyptian identification card controversy

.

), and the right to evangelize

individuals seeking to convince others to make such a change.

Other debates have centered around restricting certain kinds of missionary activity by religions. Many Islamic states, and others such as China, severely restrict missionary activities of other religions. Greece

, among European countries, has generally looked unfavorably on missionary activities of denominations others than the majority church and proselytizing is constitutionally prohibited.

A different kind of critique of the freedom to propagate religion has come from non-Abrahamic traditions such as the African and Indian. African scholar Makau Mutua criticizes religious evangelism on the ground of cultural annihilation by what he calls "proselytizing universalist faiths":

Some Indian scholars have similarly argued that the right to propagate religion is not culturally or religiously neutral.

In Sri Lanka

there have been debates regarding a bill on religious freedom that seeks to protect indigenous religious traditions from certain kinds of missionary activities. Debates have also occurred in various states of India

regarding similar laws, particularly those that restrict conversions using force, fraud or allurement.

In 2008 Christian Solidarity Worldwide

, a Christian human rights non-governmental organisation which specializes in religious freedom, launched an in-depth report on the human rights abuses faced by individuals who leave Islam for another religion. The report is the product of a year long research project in six different countries. It calls on Muslim nations, the international community, the UN and the international media to resolutely address the serious violations of human rights suffered by apostates.

In Islam, apostasy is called "ridda" ("turning back") and is considered to be a profound insult to God. A person born of Muslim parents that rejects Islam is called a "murtad fitri" (natural apostate), and a person that converted to Islam and later rejects the religion is called a "murtad milli" (apostate from the community).

In Islam, apostasy is called "ridda" ("turning back") and is considered to be a profound insult to God. A person born of Muslim parents that rejects Islam is called a "murtad fitri" (natural apostate), and a person that converted to Islam and later rejects the religion is called a "murtad milli" (apostate from the community).

In Islamic law (Sharia

), the consensus view is that a male apostate must be put to death unless he suffers from a mental disorder or converted under duress, for example, due to an imminent danger of being killed. A female apostate must be either executed, according to Shafi'i

, Maliki

, and Hanbali

schools of Sunni Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh

), or imprisoned until she reverts to Islam as advocated by the Sunni Hanafi

school and by Shi'a scholars.

Ideally, the one performing the execution of an apostate must be an imam

. At the same time, all schools of Islamic jurisprudence agree that any Muslim can kill an apostate without punishment.

is permitted in Islam it is prohibited in secular law in many countries. Does prohibiting polygamy then curtail the religious freedom of Muslims? The US

and India

, both constitutionally secular nations, have taken two different views of this. In India polygamy is permitted, but only for Muslims, under Muslim Personal Law. In the USA polygamy is prohibited for all. This was a major source of conflict between the early LDS Church and the United States until the Church amended its position on practicing polygamy.

Similar issues have also arisen in the context of the religious use of psychedelic

substances by Native American tribes in the United States as well as other Native practices.

and belief is protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

(ICCPR). This protection extends to specifically non-religious beliefs, such as humanism

. However, minority or disfavored religions still receive the spiritual injustice of persecution in many parts of the world.

provides the term of “religious majority” (Religionsmündigkeit) with a minimum age for minors

to follow their own religious beliefs even if their parents don't share those or don't approve. Children 14 and older have the unrestricted right to enter or exit any religious community. Children 12 and older cannot be compelled to change to a different belief. Children 10 and older have to be heard before their parents change their religious upbringing to a different belief. There are similar laws in Austria

and in Switzerland

.

designated fourteen nations as "countries of particular concern". The commission chairman commented that these are nations whose conduct marks them as the world’s worst religious freedom violators and human rights abusers. The fourteen nations designated were Burma, China

, Egypt

, Eritrea

, Iran

, Iraq

, Nigeria

, North Korea

, Pakistan

, Saudi Arabia

, Sudan

, Turkmenistan

, Uzbekistan

, and Vietnam

. Other nations on the commission's watchlist include Afghanistan

, Belarus

, Cuba

, India

, Indonesia

, Laos

, Russia

, Somalia

, Tajikistan

, Turkey

, and Venezuela

.

There are concerns about the persecution of religious minorities such as the banning of worn religious articles such as the Muslim veil

, Jewish skullcap

, and Christian cross

in certain European countries. Article 18 of the U.N. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

limits restrictions on freedom to manifest one's religion or beliefs to those necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others. Freedom of religion as a legal concept is related to, but not identical with, religious toleration, separation of church and state

, or secular state

(laïcité

).

Where individuals and not governments are concerned, religious toleration is generally taken to refer to an attitude of acceptance towards other people's religions. Such toleration does not require that one view other religions as equally true; rather, the assumption is that each citizen will grant that others have the right to hold and practice their own beliefs. Against this backdrop, proselytism

can be a contentious issue, as it could be regarded as an offense against the validity of others' religious beliefs, including irreligious belief.

for their religious convictions 1658-1661.. The U.S. proclaim 16 January Religious Freedom Day.

's Forum on Religion & Public Life performed a study on religious freedom in the world, for which data were gathered from 16 governmental and non-governmental organisations – including the United Nations

, the U.S. State Department and Human Rights Watch

- and representing over 99.5 percent of the world's population. According to the results, that were published in December 2009, about one-third of the countries in the world have high or very high restrictions on religion, and nearly 70 percent of the world's population lives in countries with heavy restrictions on freedom of religion. This concerns restrictions on religion originating from both national authorities and social hostilities undertaken by private individuals, organisations and social groups. Government restrictions included constitution

al limitations or other prohibitions on free speech.

Social hostilities were measured by religion-related terrorism

and violence between religious groups.

The countries in North

and South America

reportedly had some of the lowest levels of government and social restrictions on religion, while The Middle East and North Africa

were the regions with the highest.

Saudi Arabia

, Pakistan

and Iran

were the countries that top the list of countries with the overall highest levels of restriction on religion.

Of the world's 25 most populous countries, Iran, Egypt

, Indonesia

and Pakistan

had the most restrictions, while Brazil

, Japan

, the United States, Italy

, France

, South Africa

and the United Kingdom had some of the lowest levels.

While the Middle East, North Africa and the Americas exhibit either extremely high or low levels of government and social restrictions, these two variables do not always move together: Vietnam and China, for instance, had high government restrictions on religion but were in the moderate or low range when it came to social hostilities. Nigeria

and Bangladesh

follow the opposite pattern: high in social hostilities but moderate in terms of government actions.

The study found that government restrictions were relatively low in the U.S., but the levels of religious hostilities were higher than those reported in a number of other large democracies, such as Brazil and Japan.

While most countries provided for the protection of religious freedom in their constitutions or laws, only a quarter of those countries were found to fully respect these legal rights in practice.

In 75 countries - four in 10 in the world - governments limit the efforts of religious groups to proselytise and in 178 countries - 90 percent - religious groups must register with the government.

India and China, also exhibited extreme, but different restrictions on religion. China showed very high levels of government restriction but low to moderate levels of social hostilities, while India showed very high social hostilities but only low to moderate levels of government restrictions.

Israel stood out among the nations surveyed with "high scores on the social hostilities index" in comparison with other countries that are more authoritarian or less ordered.

Topping the government restrictions index were Saudi Arabia, Iran, Uzbekistan

, China, Egypt, Burma, Maldives

, Eritrea

, Malaysia and Brunei

.

At the top of the social hostilities index were Iraq

, India

, Pakistan

, Afghanistan

, Indonesia

, Bangladesh

, Somalia

, Israel

, Sri Lanka

, Sudan

and Saudi Arabia

.

Religion

Religion is a collection of cultural systems, belief systems, and worldviews that establishes symbols that relate humanity to spirituality and, sometimes, to moral values. Many religions have narratives, symbols, traditions and sacred histories that are intended to give meaning to life or to...

or belief

Belief

Belief is the psychological state in which an individual holds a proposition or premise to be true.-Belief, knowledge and epistemology:The terms belief and knowledge are used differently in philosophy....

in teaching

Religious education

In secular usage, religious education is the teaching of a particular religion and its varied aspects —its beliefs, doctrines, rituals, customs, rites, and personal roles...

, practice, worship

Worship

Worship is an act of religious devotion usually directed towards a deity. The word is derived from the Old English worthscipe, meaning worthiness or worth-ship — to give, at its simplest, worth to something, for example, Christian worship.Evelyn Underhill defines worship thus: "The absolute...

, and observance; the concept is generally recognized also to include the freedom to change religion

Religious conversion

Religious conversion is the adoption of a new religion that differs from the convert's previous religion. Changing from one denomination to another within the same religion is usually described as reaffiliation rather than conversion.People convert to a different religion for various reasons,...

or not to follow any religion

Irreligion

Irreligion is defined as an absence of religion or an indifference towards religion. Sometimes it may also be defined more narrowly as hostility towards religion. When characterized as hostility to religion, it includes antitheism, anticlericalism and antireligion. When characterized as...

. The freedom to leave or discontinue membership in a religion or religious group —in religious terms called "apostasy

Apostasy

Apostasy , 'a defection or revolt', from ἀπό, apo, 'away, apart', στάσις, stasis, 'stand, 'standing') is the formal disaffiliation from or abandonment or renunciation of a religion by a person. One who commits apostasy is known as an apostate. These terms have a pejorative implication in everyday...

" —is also a fundamental part of religious freedom, covered by Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a declaration adopted by the United Nations General Assembly . The Declaration arose directly from the experience of the Second World War and represents the first global expression of rights to which all human beings are inherently entitled...

.

Freedom of religion is considered by many people and nations to be a fundamental

Fundamental rights

Fundamental rights are a generally-regarded set of entitlements in the context of a legal system, wherein such system is itself said to be based upon this same set of basic, fundamental, or inalienable entitlements or "rights." Such rights thus belong without presumption or cost of privilege to all...

human right.

In a country with a state religion

State religion

A state religion is a religious body or creed officially endorsed by the state...

, freedom of religion is generally considered to mean that the government permits religious practices of other sects besides the state religion, and does not persecute

Religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group of individuals as a response to their religious beliefs or affiliations or lack thereof....

believers in other faiths.

History

Historically freedom of religion has been used to refer to the tolerance of different theological systems of belief, while freedom of worship has been defined as freedom of individual action. Each of these have existed to varying degrees. While many countries have accepted some form of religious freedom, this has also often been limited in practice through punitive taxation, repressive social legislation, and political disenfranchisement. Compare examples of individual freedom in ItalyItaly

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

or the Muslim

Muslim

A Muslim, also spelled Moslem, is an adherent of Islam, a monotheistic, Abrahamic religion based on the Quran, which Muslims consider the verbatim word of God as revealed to prophet Muhammad. "Muslim" is the Arabic term for "submitter" .Muslims believe that God is one and incomparable...

tradition of dhimmi

Dhimmi

A , is a non-Muslim subject of a state governed in accordance with sharia law. Linguistically, the word means "one whose responsibility has been taken". This has to be understood in the context of the definition of state in Islam...

s, literally "protected individuals" professing an officially tolerated non-Muslim religion.

Classical antiquity

Classical antiquity is a broad term for a long period of cultural history centered on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ancient Greece and ancient Rome, collectively known as the Greco-Roman world...

a syncretic

Syncretism

Syncretism is the combining of different beliefs, often while melding practices of various schools of thought. The term means "combining", but see below for the origin of the word...

point-of-view often allowed communities of traders to operate under their own customs. When street mobs of separate quarters clashed in a Hellenistic or Roman

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

city, the issue was generally perceived to be an infringement of community rights.

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia , commonly known as Cyrus the Great, also known as Cyrus the Elder, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Under his rule, the empire embraced all the previous civilized states of the ancient Near East, expanded vastly and eventually conquered most of Southwest Asia and much...

established the Achaemenid Empire

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire , sometimes known as First Persian Empire and/or Persian Empire, was founded in the 6th century BCE by Cyrus the Great who overthrew the Median confederation...

ca. 550 BC, and initiated a general policy of permitting religious freedom throughout the empire, documenting this on the Cyrus Cylinder

Cyrus cylinder

The Cyrus Cylinder is an ancient clay cylinder, now broken into several fragments, on which is written a declaration in Akkadian cuneiform script in the name of the Achaemenid king Cyrus the Great. It dates from the 6th century BC and was discovered in the ruins of Babylon in Mesopotamia in 1879...

.

Some of the historical exceptions have been in regions where one of the revealed religions has been in a position of power: Judaism

Judaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

, Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism is a religion and philosophy based on the teachings of prophet Zoroaster and was formerly among the world's largest religions. It was probably founded some time before the 6th century BCE in Greater Iran.In Zoroastrianism, the Creator Ahura Mazda is all good, and no evil...

, Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

and Islam

Islam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

. Others have been where the established order has felt threatened, as shown in the trial of Socrates

Trial of Socrates

The Trial of Socrates refers to the trial and the subsequent execution of the classical Athenian philosopher Socrates in 399 BC. Socrates was tried on the basis of two notoriously ambiguous charges: corrupting the youth and impiety...

in 399 BC or where the ruler has been deified, as in Rome, and refusal to offer token sacrifice

Sacrifice

Sacrifice is the offering of food, objects or the lives of animals or people to God or the gods as an act of propitiation or worship.While sacrifice often implies ritual killing, the term offering can be used for bloodless sacrifices of cereal food or artifacts...

was similar to refusing to take an oath of allegiance

Oath of allegiance

An oath of allegiance is an oath whereby a subject or citizen acknowledges a duty of allegiance and swears loyalty to monarch or country. In republics, modern oaths specify allegiance to the country's constitution. For example, officials in the United States, a republic, take an oath of office that...

. This was the core for resentment and the persecution of early Christian communities

Persecution of Christians

Persecution of Christians as a consequence of professing their faith can be traced both historically and in the current era. Early Christians were persecuted for their faith, at the hands of both Jews from whose religion Christianity arose, and the Roman Empire which controlled much of the land...

.

Freedom of religious worship was established in the Buddhist Maurya Empire

Maurya Empire

The Maurya Empire was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in ancient India, ruled by the Mauryan dynasty from 321 to 185 BC...

of ancient India

History of India

The history of India begins with evidence of human activity of Homo sapiens as long as 75,000 years ago, or with earlier hominids including Homo erectus from about 500,000 years ago. The Indus Valley Civilization, which spread and flourished in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent from...

by Asoka the Great in the 3rd century BC, which was encapsulated in the Edicts of Ashoka

Edicts of Ashoka

The Edicts of Ashoka are a collection of 33 inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka, as well as boulders and cave walls, made by the Emperor Ashoka of the Mauryan dynasty during his reign from 269 BCE to 231 BCE. These inscriptions are dispersed throughout the areas of modern-day Bangladesh, India,...

.

Greek-Jewish clashes at Cyrene

Cyrene, Libya

Cyrene was an ancient Greek colony and then a Roman city in present-day Shahhat, Libya, the oldest and most important of the five Greek cities in the region. It gave eastern Libya the classical name Cyrenaica that it has retained to modern times.Cyrene lies in a lush valley in the Jebel Akhdar...

in 73 AD and 117 AD and in Alexandria

Alexandria

Alexandria is the second-largest city of Egypt, with a population of 4.1 million, extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea in the north central part of the country; it is also the largest city lying directly on the Mediterranean coast. It is Egypt's largest seaport, serving...

in 115 AD provide examples of cosmopolitan cities as scenes of tumult.

Middle East

Following a period of fighting lasting around a hundred years before 620 AD which mainly involved Arab and Jewish inhabitants of MedinaMedina

Medina , or ; also transliterated as Madinah, or madinat al-nabi "the city of the prophet") is a city in the Hejaz region of western Saudi Arabia, and serves as the capital of the Al Madinah Province. It is the second holiest city in Islam, and the burial place of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, and...

(then known as Yathrib), religious freedom for Muslim

Muslim

A Muslim, also spelled Moslem, is an adherent of Islam, a monotheistic, Abrahamic religion based on the Quran, which Muslims consider the verbatim word of God as revealed to prophet Muhammad. "Muslim" is the Arabic term for "submitter" .Muslims believe that God is one and incomparable...

s, Jews and pagans

Paganism

Paganism is a blanket term, typically used to refer to non-Abrahamic, indigenous polytheistic religious traditions....

was declared by Muhammad

Muhammad

Muhammad |ligature]] at U+FDF4 ;Arabic pronunciation varies regionally; the first vowel ranges from ~~; the second and the last vowel: ~~~. There are dialects which have no stress. In Egypt, it is pronounced not in religious contexts...

in the Constitution of Medina

Constitution of Medina

The Constitution of Medina , also known as the Charter of Medina, was drafted by the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It constituted a formal agreement between Muhammad and all of the significant tribes and families of Yathrib , including Muslims, Jews, Christians and pagans. This constitution formed the...

. The Islamic Caliphate

Caliphate

The term caliphate, "dominion of a caliph " , refers to the first system of government established in Islam and represented the political unity of the Muslim Ummah...

later guaranteed religious freedom under the conditions that non-Muslim communities accept dhimmi

Dhimmi

A , is a non-Muslim subject of a state governed in accordance with sharia law. Linguistically, the word means "one whose responsibility has been taken". This has to be understood in the context of the definition of state in Islam...

(protected) status and their adult males pay the jizya

Jizya

Under Islamic law, jizya or jizyah is a per capita tax levied on a section of an Islamic state's non-Muslim citizens, who meet certain criteria...

tax as a substitute for the zakat

Zakat

Zakāt , one of the Five Pillars of Islam, is the giving of a fixed portion of one's wealth to charity, generally to the poor and needy.-History:Zakat, a practice initiated by Muhammed himself, has played an important role throughout Islamic history...

paid by Muslim citizens. Jews and Christians were alternately toleratedand persecuted, the most notable examples of the latter being the conquest of Islamic Spain by fundamentalist groups from north Africa (the Almoravids

Almoravids

The Almoravids were a Berber dynasty of Morocco, who formed an empire in the 11th-century that stretched over the western Maghreb and Al-Andalus. Their capital was Marrakesh, a city which they founded in 1062 C.E...

, followed by the Almohads from the mid-12th century). Persecution of non-Muslims caused the emigration of many Jews (and Christians) into the northern, Christian states.

Religious pluralism

Religious pluralism

Religious pluralism is a loosely defined expression concerning acceptance of various religions, and is used in a number of related ways:* As the name of the worldview according to which one's religion is not the sole and exclusive source of truth, and thus that at least some truths and true values...

existed in classical Islamic ethics

Islamic ethics

Islamic ethics , defined as "good character," historically took shape gradually from the 7th century and was finally established by the 11th century...

and Sharia

Sharia

Sharia law, is the moral code and religious law of Islam. Sharia is derived from two primary sources of Islamic law: the precepts set forth in the Quran, and the example set by the Islamic prophet Muhammad in the Sunnah. Fiqh jurisprudence interprets and extends the application of sharia to...

law, as the religious law

Religious law

In some religions, law can be thought of as the ordering principle of reality; knowledge as revealed by a God defining and governing all human affairs. Law, in the religious sense, also includes codes of ethics and morality which are upheld and required by the God...

s and court

Court

A court is a form of tribunal, often a governmental institution, with the authority to adjudicate legal disputes between parties and carry out the administration of justice in civil, criminal, and administrative matters in accordance with the rule of law...

s of other religions, including Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

, Judaism

Judaism

Judaism ) is the "religion, philosophy, and way of life" of the Jewish people...

and Hinduism

Hinduism

Hinduism is the predominant and indigenous religious tradition of the Indian Subcontinent. Hinduism is known to its followers as , amongst many other expressions...

, were usually accommodated within the Islamic legal framework, as seen in the early Caliphate

Caliphate

The term caliphate, "dominion of a caliph " , refers to the first system of government established in Islam and represented the political unity of the Muslim Ummah...

, Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus was the Arabic name given to a nation and territorial region also commonly referred to as Moorish Iberia. The name describes parts of the Iberian Peninsula and Septimania governed by Muslims , at various times in the period between 711 and 1492, although the territorial boundaries...

, Indian subcontinent

Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent

Muslim conquest in South Asia mainly took place from the 13th to the 16th centuries, though earlier Muslim conquests made limited inroads into the region, beginning during the period of the ascendancy of the Rajput Kingdoms in North India, from the 7th century onwards.However, the Himalayan...

, and the Ottoman Millet

Millet (Ottoman Empire)

Millet is a term for the confessional communities in the Ottoman Empire. It refers to the separate legal courts pertaining to "personal law" under which communities were allowed to rule themselves under their own system...

system. In medieval Islamic societies, the qadi

Qadi

Qadi is a judge ruling in accordance with Islamic religious law appointed by the ruler of a Muslim country. Because Islam makes no distinction between religious and secular domains, qadis traditionally have jurisdiction over all legal matters involving Muslims...

(Islamic judges) usually could not interfere in the matters of non-Muslims unless the parties voluntarily choose to be judged according to Islamic law, thus the dhimmi communities living in Islamic state

Islamic State

An Islamic state is a type of government, in which the primary basis for government is Islamic religious law...

s usually had their own laws independent from the Sharia law, such as the Jews who would have their own Halakha

Halakha

Halakha — also transliterated Halocho , or Halacha — is the collective body of Jewish law, including biblical law and later talmudic and rabbinic law, as well as customs and traditions.Judaism classically draws no distinction in its laws between religious and ostensibly non-religious life; Jewish...

courts.

Dhimmis were allowed to operate their own courts following their own legal systems in cases that did not involve other religious groups, or capital offences or threats to public order. Non-Muslims were allowed to engage in religious practices that was usually forbidden by Islamic law, such as the consumption of alcohol

Alcohol

In chemistry, an alcohol is an organic compound in which the hydroxy functional group is bound to a carbon atom. In particular, this carbon center should be saturated, having single bonds to three other atoms....

and pork

Pork

Pork is the culinary name for meat from the domestic pig , which is eaten in many countries. It is one of the most commonly consumed meats worldwide, with evidence of pig husbandry dating back to 5000 BC....

, as well as religious practices which Muslims found repugnant, such as the Zoroastrian

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism is a religion and philosophy based on the teachings of prophet Zoroaster and was formerly among the world's largest religions. It was probably founded some time before the 6th century BCE in Greater Iran.In Zoroastrianism, the Creator Ahura Mazda is all good, and no evil...

practice of incest

Incest

Incest is sexual intercourse between close relatives that is usually illegal in the jurisdiction where it takes place and/or is conventionally considered a taboo. The term may apply to sexual activities between: individuals of close "blood relationship"; members of the same household; step...

uous "self-marriage" where a man could marry his mother, sister or daughter. According to the famous Islamic legal scholar Ibn Qayyim (1292–1350), non-Muslims had the right to engage in such religious practices even if it offended Muslims, under the conditions that such cases not be presented to Islamic Sharia courts and that these religious minorities believed that the practice in question is permissible according to their religion.

India

Religious freedom and the right to worship freely were practices that had been appreciated and promoted by most ancient Indian dynasties. As a result, people fleeing religious persecutionReligious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group of individuals as a response to their religious beliefs or affiliations or lack thereof....

in other parts of the world including Christians, Jews, Bahá'i and Zoroastrians fled to India as a place of refuge to enjoy religious freedom. This had been the underlying attitude of most rulers of India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

from time immemorial.

Ancient Jews

Jews

The Jews , also known as the Jewish people, are a nation and ethnoreligious group originating in the Israelites or Hebrews of the Ancient Near East. The Jewish ethnicity, nationality, and religion are strongly interrelated, as Judaism is the traditional faith of the Jewish nation...

fleeing from persecution in their homeland 2,500 years ago settled in India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

and never faced anti-Semitism

Anti-Semitism

Antisemitism is suspicion of, hatred toward, or discrimination against Jews for reasons connected to their Jewish heritage. According to a 2005 U.S...

. Freedom of religion edicts have been found written during Ashoka the Great's reign in the 3rd century BC. Freedom to practise, preach and propagate any religion is a constitutional right in Modern India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

. Most major religious festivals of the main communities are included in the list of national holidays.

India is an 80% Hindu

Hindu

Hindu refers to an identity associated with the philosophical, religious and cultural systems that are indigenous to the Indian subcontinent. As used in the Constitution of India, the word "Hindu" is also attributed to all persons professing any Indian religion...

country, yet its prime minister

Prime Minister of India

The Prime Minister of India , as addressed to in the Constitution of India — Prime Minister for the Union, is the chief of government, head of the Council of Ministers and the leader of the majority party in parliament...

is a Sikh

Sikh

A Sikh is a follower of Sikhism. It primarily originated in the 15th century in the Punjab region of South Asia. The term "Sikh" has its origin in Sanskrit term शिष्य , meaning "disciple, student" or शिक्ष , meaning "instruction"...

(Manmohan Singh

Manmohan Singh

Manmohan Singh is the 13th and current Prime Minister of India. He is the only Prime Minister since Jawaharlal Nehru to return to power after completing a full five-year term. A Sikh, he is the first non-Hindu to occupy the office. Singh is also the 7th Prime Minister belonging to the Indian...

), the chairperson of the ruling alliance

United Progressive Alliance

The United Progressive Alliance is a ruling coalition of center-left political parties heading the government of India. The coalition is led by the Indian National Congress , which is currently the single largest political party in the Lok Sabha...

is a Catholic woman of Italian

Italian people

The Italian people are an ethnic group that share a common Italian culture, ancestry and speak the Italian language as a mother tongue. Within Italy, Italians are defined by citizenship, regardless of ancestry or country of residence , and are distinguished from people...

birth (Sonia Gandhi

Sonia Gandhi

Sonia Gandhi is an Italian-born Indian politician and the President of the Indian National Congress, one of the major political parties of India. She is the widow of former Prime Minister of India, Rajiv Gandhi...

), and three out of the twelve presidents of India have been Muslims. Further, the current Chief Election Commissioner of India

Chief Election Commissioner of India

The Chief Election Commissioner heads the Election Commission of India, a body constitutionally empowered to conduct free and fair elections to the national and state legislatures...

is a Muslim,as are many successful Indians including film stars,artists,religious scholars,industrialists etc. Still, though some argue that India

India

India , officially the Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by geographical area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2 billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world...

's predominant religion, Hinduism

Hinduism

Hinduism is the predominant and indigenous religious tradition of the Indian Subcontinent. Hinduism is known to its followers as , amongst many other expressions...

, has long been among the most tolerant of religions, others assert that tolerance only appeared in India with the emergence of the modern Republic of India as a secular nation in 1947.

The Dalai Lama

Dalai Lama

The Dalai Lama is a high lama in the Gelug or "Yellow Hat" branch of Tibetan Buddhism. The name is a combination of the Mongolian word далай meaning "Ocean" and the Tibetan word bla-ma meaning "teacher"...

, the Tibetan leader in exile said that religious tolerance of ‘Aryabhoomi,’ a reference to India found in Mahabharata, has been in existence in this country from thousands of years. “Not only Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, Sikhism which are the native religions but also Christianity and Islam have flourished here. Religious tolerance is inherent in Indian tradition,’’ Dalai Lama said.

Freedom of religion in the Indian subcontinent

Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent, also Indian Subcontinent, Indo-Pak Subcontinent or South Asian Subcontinent is a region of the Asian continent on the Indian tectonic plate from the Hindu Kush or Hindu Koh, Himalayas and including the Kuen Lun and Karakoram ranges, forming a land mass which extends...

is exemplified by the reign of King Piyadasi (304 BC to 232 BC) (Asoka). One of King Asoka's main concerns was to reform governmental institutes and exercise moral principles in his attempt to create a just and humane society

Edicts of Ashoka

The Edicts of Ashoka are a collection of 33 inscriptions on the Pillars of Ashoka, as well as boulders and cave walls, made by the Emperor Ashoka of the Mauryan dynasty during his reign from 269 BCE to 231 BCE. These inscriptions are dispersed throughout the areas of modern-day Bangladesh, India,...

. Later he promoted the principles of Buddhism

Buddhism

Buddhism is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha . The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th...

, and the creation of a just, understanding and fair society was held as an important principle for many ancient rulers of this time in the East.

The importance of freedom of worship in India was encapsulated in an inscription of Asoka:

The initial entry of Islam

Islam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

into South Asia

South Asia

South Asia, also known as Southern Asia, is the southern region of the Asian continent, which comprises the sub-Himalayan countries and, for some authorities , also includes the adjoining countries to the west and the east...

came in the first century after the death of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad

Muhammad

Muhammad |ligature]] at U+FDF4 ;Arabic pronunciation varies regionally; the first vowel ranges from ~~; the second and the last vowel: ~~~. There are dialects which have no stress. In Egypt, it is pronounced not in religious contexts...

. When around 1210 AD the Islamic Sultanates

Islamic empires in India

Beginning in the 12th century, several Islamic states were established in the Indian subcontinentin the course of a gradual Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent....

invaded India from the north-west, gradually the principle of freedom of religion deteriorated in this part of the world. They were subsequently replaced by another Islamic invader in the form of Babur

Babur

Babur was a Muslim conqueror from Central Asia who, following a series of setbacks, finally succeeded in laying the basis for the Mughal dynasty of South Asia. He was a direct descendant of Timur through his father, and a descendant also of Genghis Khan through his mother...

. The Mughal

Mughal Empire

The Mughal Empire , or Mogul Empire in traditional English usage, was an imperial power from the Indian Subcontinent. The Mughal emperors were descendants of the Timurids...

empire was founded by the Mongol leader Babur

Babur

Babur was a Muslim conqueror from Central Asia who, following a series of setbacks, finally succeeded in laying the basis for the Mughal dynasty of South Asia. He was a direct descendant of Timur through his father, and a descendant also of Genghis Khan through his mother...

in 1526, when he defeated Ibrahim Lodi, the last of the Delhi Sultans

Delhi Sultanate

The Delhi Sultanate is a term used to cover five short-lived, Delhi based kingdoms or sultanates, of Turkic origin in medieval India. The sultanates ruled from Delhi between 1206 and 1526, when the last was replaced by the Mughal dynasty...

at the First Battle of Panipat

First battle of Panipat

The first battle of Panipat took place in Northern India, and marked the beginning of the Mughal Empire. This was one of the earliest battles involving gunpowder firearms and field artillery.-Details:...

. The word "Mughal" is the Indo-Iranian version of Mongol.

On the main Asian continent, the Mongols were tolerant of religions. People could worship as they wished freely and openly, though the formation of 2 nations i.e. Pakistan and Bangladesh has been on basis of religious intolerance.

After arrival of Europeans, Christians in zeal to convert local as per belief in conversion as service of God, have also been seen to fall into frivolous methods since their arrival. Though by and large there are hardly any reports of law and order disturbance from mobs with Christian beliefs except perhaps in the north eastern region of India.

The rise of the BJP political party and the emergence of Hindu nationalism

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

have been accompanied by the repression of Christianity and in some cases assaults on Christians and their institutions. The worst of these happened in August 2008 when 4,640 houses and 252 churches were torched in Kandhamal. 54,000 people were made homeless by the violence. Attacks continue and in November 2010 Hindutva

Hindutva