Bricker Amendment

Encyclopedia

.jpg)

Article Five of the United States Constitution

Article Five of the United States Constitution describes the process whereby the Constitution may be altered. Altering the Constitution consists of proposing an amendment and subsequent ratification....

to the United States Constitution

United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It is the framework for the organization of the United States government and for the relationship of the federal government with the states, citizens, and all people within the United States.The first three...

considered by the United States Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

in the 1950s. These amendments would have placed restrictions on the scope and ratification of treaties

Treaty

A treaty is an express agreement under international law entered into by actors in international law, namely sovereign states and international organizations. A treaty may also be known as an agreement, protocol, covenant, convention or exchange of letters, among other terms...

and executive agreements entered into by the United States and are named for their sponsor, Senator John W. Bricker

John W. Bricker

John William Bricker was a United States Senator and the 54th Governor of Ohio. A member of the Republican Party, he was the Republican nominee for Vice President in 1944.-Early life:...

of Ohio

Ohio

Ohio is a Midwestern state in the United States. The 34th largest state by area in the U.S.,it is the 7th‑most populous with over 11.5 million residents, containing several major American cities and seven metropolitan areas with populations of 500,000 or more.The state's capital is Columbus...

, a conservative Republican

Republican Party (United States)

The Republican Party is one of the two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Democratic Party. Founded by anti-slavery expansion activists in 1854, it is often called the GOP . The party's platform generally reflects American conservatism in the U.S...

.

Non-interventionism

Non-interventionism

Nonintervention or non-interventionism is a foreign policy which holds that political rulers should avoid alliances with other nations, but still retain diplomacy, and avoid all wars not related to direct self-defense...

, the view that the United States should not become embroiled in foreign conflicts and world politics, has always been an element in American politics but was especially strong in the years following World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. American entry into World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

temporarily suppressed non-interventionist sentiments, but they returned in the post-war years in response to America's new international role, particularly as a reaction to the new United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

and its affiliated international organization

International organization

An intergovernmental organization, sometimes rendered as an international governmental organization and both abbreviated as IGO, is an organization composed primarily of sovereign states , or of other intergovernmental organizations...

s. Some feared the loss of American sovereignty

Sovereignty

Sovereignty is the quality of having supreme, independent authority over a geographic area, such as a territory. It can be found in a power to rule and make law that rests on a political fact for which no purely legal explanation can be provided...

to these transnational agencies, because of the Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

's role in the spread of international Communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

and the Cold War

Cold War

The Cold War was the continuing state from roughly 1946 to 1991 of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition between the Communist World—primarily the Soviet Union and its satellite states and allies—and the powers of the Western world, primarily the United States...

.

Frank E. Holman

Frank E. Holman

Frank Ezekiel Holman was an American attorney who after his election as president of the American Bar Association in 1948 led an effort to amend the United States Constitution to limit the power of treaties and executive agreements. Holman's work led to the Bricker Amendment.Holman was born in...

, president of the American Bar Association

American Bar Association

The American Bar Association , founded August 21, 1878, is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. The ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of academic standards for law schools, and the formulation...

(ABA), called attention to state and Federal court

United States federal courts

The United States federal courts make up the judiciary branch of federal government of the United States organized under the United States Constitution and laws of the federal government.-Categories:...

decisions, notably Missouri v. Holland

Missouri v. Holland

Missouri v. Holland, 252 U.S. 416 , the United States Supreme Court held that protection of its quasi-sovereign right to regulate the taking of game is a sufficient jurisdictional basis, apart from any pecuniary interest, for a bill by a State to enjoin enforcement of federal regulations over the...

, which he claimed could give international treaties and agreements precedence over the United States Constitution and could be used by foreigners to threaten American liberties. Senator Bricker was influenced by the ABA's work and first introduced a constitutional amendment in 1951. With substantial popular support and the election of a Republican President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

and Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

in the elections of 1952, Bricker's plan seemed destined to be sent to the individual states for ratification. The best-known version of the Bricker Amendment, considered by the Senate in 1953–54, declared that no treaty could be made by the United States that conflicted with the Constitution, was self-executing without the passage of separate enabling legislation through Congress, or which granted Congress legislative powers beyond those specified in the Constitution. It also limited the president's power to enter into executive agreements with foreign powers.

Bricker's proposal attracted broad bipartisan

Bipartisanship

Bipartisanship is a political situation, usually in the context of a two-party system such as the United States, in which opposing political parties find common ground through compromise. The adjective bipartisan can refer to any bill, act, resolution, or other political act in which both of the...

support and was a focal point of intra-party conflict between the administration of president Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

and the Old Right

Old Right (United States)

The Old Right was a conservative faction in the United States that opposed both New Deal domestic programs and U.S. entry into World War II. Many members of this faction were associated with the Republicans of the interwar years led by Robert Taft, but some were Democrats...

faction of conservative Republican senators. Despite the initial support, the Bricker Amendment was blocked through the intervention of President Eisenhower and failed in the Senate by a single vote in 1954. Three years later the Supreme Court of the United States

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

explicitly ruled in Reid v. Covert

Reid v. Covert

Reid v. Covert, , is a landmark case in which the United States Supreme Court ruled that the Constitution supersedes international treaties ratified by the United States Senate...

that the Bill of Rights

United States Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights is the collective name for the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution. These limitations serve to protect the natural rights of liberty and property. They guarantee a number of personal freedoms, limit the government's power in judicial and other proceedings, and...

cannot be abrogated by agreements with foreign powers. Nevertheless, Senator Bricker's ideas still have supporters, and new versions of his amendment have been reintroduced in Congress periodically.

American non-interventionism

Non-interventionism

Nonintervention or non-interventionism is a foreign policy which holds that political rulers should avoid alliances with other nations, but still retain diplomacy, and avoid all wars not related to direct self-defense...

, nationalism

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

, and suspicion of foreign influences that has existed from the beginnings of the American republic

Republic

A republic is a form of government in which the people, or some significant portion of them, have supreme control over the government and where offices of state are elected or chosen by elected people. In modern times, a common simplified definition of a republic is a government where the head of...

. "Non-interventionism was the considered response to foreign and domestic developments of a large, responsible, and respectable segment of the American people," wrote one historian of the movement. The pre-Revolutionary

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

cry of "no taxation without representation

No taxation without representation

"No taxation without representation" is a slogan originating during the 1750s and 1760s that summarized a primary grievance of the British colonists in the Thirteen Colonies, which was one of the major causes of the American Revolution...

!" spoke to the inability of Americans to participate in how they would be governed, a state made clear when British

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

authorities suppressed local government in colonies

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were English and later British colonies established on the Atlantic coast of North America between 1607 and 1733. They declared their independence in the American Revolution and formed the United States of America...

accustomed to home rule

Home rule

Home rule is the power of a constituent part of a state to exercise such of the state's powers of governance within its own administrative area that have been devolved to it by the central government....

, e.g. Massachusetts

Province of Massachusetts Bay

The Province of Massachusetts Bay was a crown colony in North America. It was chartered on October 7, 1691 by William and Mary, the joint monarchs of the kingdoms of England and Scotland...

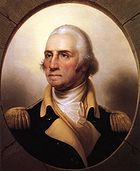

. The first President

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

, George Washington

George Washington

George Washington was the dominant military and political leader of the new United States of America from 1775 to 1799. He led the American victory over Great Britain in the American Revolutionary War as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army from 1775 to 1783, and presided over the writing of...

, warned his countrymen to observe good faith and justice towards all nations, to cultivate peace and harmony with all, excluding both "inveterate antipathies against particular nations, and passionate attachments for others",and "to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world." Under John Adams

John Adams

John Adams was an American lawyer, statesman, diplomat and political theorist. A leading champion of independence in 1776, he was the second President of the United States...

, his successor, the United States attempted to avoid the conflict

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars were a series of major conflicts, from 1792 until 1802, fought between the French Revolutionary government and several European states...

between France and Britain, and passed the Alien and Sedition Acts

Alien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts were four bills passed in 1798 by the Federalists in the 5th United States Congress in the aftermath of the French Revolution's reign of terror and during an undeclared naval war with France, later known as the Quasi-War. They were signed into law by President John Adams...

of 1798 to control foreign citizens. In his inaugural address, President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

declared that one of "the essential principles of our Government" was "peace, commerce, and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none." President James Monroe

James Monroe

James Monroe was the fifth President of the United States . Monroe was the last president who was a Founding Father of the United States, and the last president from the Virginia dynasty and the Republican Generation...

's doctrine

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a policy of the United States introduced on December 2, 1823. It stated that further efforts by European nations to colonize land or interfere with states in North or South America would be viewed as acts of aggression requiring U.S. intervention...

(1823) announced the primacy of American influence in the Western Hemisphere.

In the 20th century, America was initially neutral in World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

and avoided entering the conflict for three years. President Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

, a Democrat

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

, won reelection in 1916

United States presidential election, 1916

The United States presidential election of 1916 took place while Europe was embroiled in World War I. Public sentiment in the still neutral United States leaned towards the British and French forces, due to the harsh treatment of civilians by the German Army, which had invaded and occupied large...

with the slogan "he kept us out of war," although he subsequently led the U.S. into the conflict. Once hostilities were concluded, Republican Senators William Borah of Idaho

Idaho

Idaho is a state in the Rocky Mountain area of the United States. The state's largest city and capital is Boise. Residents are called "Idahoans". Idaho was admitted to the Union on July 3, 1890, as the 43rd state....

and Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot Lodge

Henry Cabot "Slim" Lodge was an American Republican Senator and historian from Massachusetts. He had the role of Senate Majority leader. He is best known for his positions on Meek policy, especially his battle with President Woodrow Wilson in 1919 over the Treaty of Versailles...

of Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

led like-minded colleagues in the United States Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

to reject the Treaty of Versailles

Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles was one of the peace treaties at the end of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June 1919, exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The other Central Powers on the German side of...

(1919) and to avoid joining both international agencies created by it, the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

and the World Court

Permanent Court of International Justice

The Permanent Court of International Justice, often called the World Court, was an international court attached to the League of Nations. Created in 1922 , the Court was initially met with a good reaction from states and academics alike, with many cases submitted to it for its first decade of...

, for fear of losing American sovereignty

Sovereignty

Sovereignty is the quality of having supreme, independent authority over a geographic area, such as a territory. It can be found in a power to rule and make law that rests on a political fact for which no purely legal explanation can be provided...

.

This fear of foreign control was long associated with anti-Catholicism and attendant allegations of Catholic dual loyalty

Dual loyalty

In politics, dual loyalty is loyalty to two separate interests that potentially conflict with each other.-Inherently controversial:While nearly all examples of alleged "dual loyalty" are considered highly controversial, these examples point to the inherent difficulty in distinguishing between what...

to their country and the Pope

Pope

The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle...

, stemming from America's British Protestant roots. As late as the 1960 presidential election, in which President John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald "Jack" Kennedy , often referred to by his initials JFK, was the 35th President of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963....

became America's first Catholic chief executive, there were Americans who believed Catholics' first loyalty would be to the Pope and not the United States. Previous concerns about "foreign influence" led to restrictive laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the Johnson-Reed Act

Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the National Origins Act, and Asian Exclusion Act , was a United States federal law that limited the annual number of immigrants who could be admitted from any country to 2% of the number of people from that country who were already...

of 1924, the Smith Act

Smith Act

The Alien Registration Act or Smith Act of 1940 is a United States federal statute that set criminal penalties for advocating the overthrow of the U.S...

of 1940, and numerous state laws restricting foreigners from engaging in business or owning land. Similarly, America long maintained a protectionist

Protectionism

Protectionism is the economic policy of restraining trade between states through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, restrictive quotas, and a variety of other government regulations designed to allow "fair competition" between imports and goods and services produced domestically.This...

trade

International trade

International trade is the exchange of capital, goods, and services across international borders or territories. In most countries, such trade represents a significant share of gross domestic product...

policy with high tariff

Tariff

A tariff may be either tax on imports or exports , or a list or schedule of prices for such things as rail service, bus routes, and electrical usage ....

s on foreign products, notably the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act of 1930.

In the 1930s, legislators of both parties opposed American involvement in the conflicts in Asia and Europe. Between 1934 and 1936, Senator Gerald Nye

Gerald Nye

Gerald Prentice Nye was a United States politician, representing North Dakota in the U.S. Senate from 1925-45...

held dramatic hearings

Nye Committee

The Nye Committee, officially known as the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry, was a committee of the United States Senate which studied the causes of United States' involvement in World War I...

attempting to show that America was forced into World War I by an alliance of arms merchants, bankers, and foreign influences. In response, Congress

United States Congress

The United States Congress is the bicameral legislature of the federal government of the United States, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives. The Congress meets in the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C....

passed, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

signed, Senator Nye's Neutrality Act of 1935 to preclude American involvement in another European war.

Several times after the conclusion of World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

, constitutional amendments were proposed in Congress to require a nationwide referendum on declaring war. When President Roosevelt in 1937 proposed a "quarantine" of aggressing nations such as Japan

Empire of Japan

The Empire of Japan is the name of the state of Japan that existed from the Meiji Restoration on 3 January 1868 to the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of...

, he found little support, remarking "It's a terrible thing to look over your shoulder when you are trying to lead—and find no one there." The America First Committee

America First Committee

The America First Committee was the foremost non-interventionist pressure group against the American entry into World War II. Peaking at 800,000 members, it was likely the largest anti-war organization in American history. Started in 1940, it became defunct after the attack on Pearl Harbor in...

, formed in 1940 to keep the United States out of World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, included Americans across the political spectrum from socialist Norman Thomas

Norman Thomas

Norman Mattoon Thomas was a leading American socialist, pacifist, and six-time presidential candidate for the Socialist Party of America.-Early years:...

, journalist John T. Flynn

John T. Flynn

John Thomas Flynn was an American journalist best known for his opposition to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and to American entry into World War II.-Career:...

of The New Republic

The New Republic

The magazine has also published two articles concerning income inequality, largely criticizing conservative economists for their attempts to deny the existence or negative effect increasing income inequality is having on the United States...

, and Senator Burton K. Wheeler

Burton K. Wheeler

Burton Kendall Wheeler was an American politician of the Democratic Party and a United States Senator from 1923 until 1947.-Early life:...

of Montana

Montana

Montana is a state in the Western United States. The western third of Montana contains numerous mountain ranges. Smaller, "island ranges" are found in the central third of the state, for a total of 77 named ranges of the Rocky Mountains. This geographical fact is reflected in the state's name,...

on the left to Chicago Tribune

Chicago Tribune

The Chicago Tribune is a major daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, and the flagship publication of the Tribune Company. Formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" , it remains the most read daily newspaper of the Chicago metropolitan area and the Great Lakes region and is...

publisher Colonel Robert R. McCormick

Robert R. McCormick

Robert Rutherford "Colonel" McCormick was a member of the McCormick family of Chicago who became owner and publisher of the Chicago Tribune newspaper...

, Sears, Roebuck chairman General Robert E. Wood

Robert E. Wood

Robert Elkington Wood was a U.S. Army Brigadier General and businessman best known for his leadership of Sears, Roebuck and Company.- Early life :...

, and Senator Nye on the right. Prior to America's entry into World War II, President Roosevelt proposed helping the United Kingdom against Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany , also known as the Third Reich , but officially called German Reich from 1933 to 1943 and Greater German Reich from 26 June 1943 onward, is the name commonly used to refer to the state of Germany from 1933 to 1945, when it was a totalitarian dictatorship ruled by...

; in response, Senator Wheeler famously declared "the lend-lease-give program

Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease was the program under which the United States of America supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, China, Free France, and other Allied nations with materiel between 1941 and 1945. It was signed into law on March 11, 1941, a year and a half after the outbreak of war in Europe in...

is the New Deal

New Deal

The New Deal was a series of economic programs implemented in the United States between 1933 and 1936. They were passed by the U.S. Congress during the first term of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The programs were Roosevelt's responses to the Great Depression, and focused on what historians call...

's triple-A

Agricultural Adjustment Act

The Agricultural Adjustment Act was a United States federal law of the New Deal era which restricted agricultural production by paying farmers subsidies not to plant part of their land and to kill off excess livestock...

foreign policy; it will plow under every fourth American boy." Senator Wheeler was even thought to have leaked the United States's war plan Rainbow 5 (which superseded Orange

War Plan Orange

War Plan Orange refers to a series of United States Joint Army and Navy Board war plans for dealing with a possible war with Japan during the years between the First and Second World Wars....

) only days before the attack on Pearl Harbor

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941...

on December 7, 1941. Typical of American sentiment was the title of an anti-interventionist book, Why Meddle in Europe? Even Bainbridge Colby

Bainbridge Colby

Bainbridge Colby was an American lawyer, a founder of the United States Progressive Party and Woodrow Wilson's last Secretary of State.-Life:...

, Secretary of State

United States Secretary of State

The United States Secretary of State is the head of the United States Department of State, concerned with foreign affairs. The Secretary is a member of the Cabinet and the highest-ranking cabinet secretary both in line of succession and order of precedence...

under Woodrow Wilson

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th President of the United States, from 1913 to 1921. A leader of the Progressive Movement, he served as President of Princeton University from 1902 to 1910, and then as the Governor of New Jersey from 1911 to 1913...

, testified to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee

United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the United States Senate. It is charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. The Foreign Relations Committee is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid programs as...

in 1939 that entering World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

had been a mistake and the United States would have been better off even if Germany had won that conflict.

Fears return after World War II

Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike conducted by the Imperial Japanese Navy against the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on the morning of December 7, 1941...

temporarily silenced American non-interventionism; the America First Committee

America First Committee

The America First Committee was the foremost non-interventionist pressure group against the American entry into World War II. Peaking at 800,000 members, it was likely the largest anti-war organization in American history. Started in 1940, it became defunct after the attack on Pearl Harbor in...

disbanded within days. However, in the final days of World War II, non-interventionism began its resurgence— non-interventionists had spoken against ratification of the United Nations Charter

United Nations Charter

The Charter of the United Nations is the foundational treaty of the international organization called the United Nations. It was signed at the San Francisco War Memorial and Performing Arts Center in San Francisco, United States, on 26 June 1945, by 50 of the 51 original member countries...

but were unsuccessful in preventing the United States from becoming a founding member of the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

. Suspicions of the U.N. and its associated international organization

International organization

An intergovernmental organization, sometimes rendered as an international governmental organization and both abbreviated as IGO, is an organization composed primarily of sovereign states , or of other intergovernmental organizations...

s were fanned by conservatives, most notably by Frank E. Holman

Frank E. Holman

Frank Ezekiel Holman was an American attorney who after his election as president of the American Bar Association in 1948 led an effort to amend the United States Constitution to limit the power of treaties and executive agreements. Holman's work led to the Bricker Amendment.Holman was born in...

, an attorney from Seattle, Washington in what has been called a "crusade."

Holman, a Utah

Utah

Utah is a state in the Western United States. It was the 45th state to join the Union, on January 4, 1896. Approximately 80% of Utah's 2,763,885 people live along the Wasatch Front, centering on Salt Lake City. This leaves vast expanses of the state nearly uninhabited, making the population the...

native and Rhodes scholar

Rhodes Scholarship

The Rhodes Scholarship, named after Cecil Rhodes, is an international postgraduate award for study at the University of Oxford. It was the first large-scale programme of international scholarships, and is widely considered the "world's most prestigious scholarship" by many public sources such as...

, was elected president of the American Bar Association

American Bar Association

The American Bar Association , founded August 21, 1878, is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. The ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of academic standards for law schools, and the formulation...

in 1947 and dedicated his term as president to warning Americans of the dangers of "treaty law." While Article II of the United Nations Charter stated "Nothing contained in the present Charter shall authorize the United Nations to intervene in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state," an international analogue to the Tenth Amendment

Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which is part of the Bill of Rights, was ratified on December 15, 1791...

, Holman saw the work of the U.N. on the proposed Genocide Convention

Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on 9 December 1948 as General Assembly Resolution 260. The Convention entered into force on 12 January 1951. It defines genocide in legal terms, and is the culmination of...

and Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights is a declaration adopted by the United Nations General Assembly . The Declaration arose directly from the experience of the Second World War and represents the first global expression of rights to which all human beings are inherently entitled...

and numerous proposals of the International Labor Organization, a body created under the League of Nations

League of Nations

The League of Nations was an intergovernmental organization founded as a result of the Paris Peace Conference that ended the First World War. It was the first permanent international organization whose principal mission was to maintain world peace...

, as being far outside the UN's powers and an invasion against American liberties.

Holman cautioned the Genocide

Genocide

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

Convention would subject Americans to the jurisdiction of foreign courts with unfamiliar procedures and without the protections afforded under the Bill of Rights

United States Bill of Rights

The Bill of Rights is the collective name for the first ten amendments to the United States Constitution. These limitations serve to protect the natural rights of liberty and property. They guarantee a number of personal freedoms, limit the government's power in judicial and other proceedings, and...

. He said the Convention's language was sweeping and vague and offered a scenario where a white motorist who struck and killed a black child could be extradited to The Hague

The Hague

The Hague is the capital city of the province of South Holland in the Netherlands. With a population of 500,000 inhabitants , it is the third largest city of the Netherlands, after Amsterdam and Rotterdam...

on genocide charges. Holman's critics claimed the language was no more sweeping or vague than the state and Federal statutes that American courts interpreted every day. Duane Tananbaum, the leading historian of the Bricker Amendment, wrote "most of ABA's objections to the Genocide Convention had no basis whatsoever in reality" and his example of a car accident becoming an international incident was not possible. Eisenhower's Attorney General

United States Attorney General

The United States Attorney General is the head of the United States Department of Justice concerned with legal affairs and is the chief law enforcement officer of the United States government. The attorney general is considered to be the chief lawyer of the U.S. government...

Herbert Brownell

Herbert Brownell, Jr.

Herbert Brownell, Jr. was the Attorney General of the United States in President Eisenhower's cabinet from 1953 to 1957.-Early life:...

called this scenario "outlandish".

But Holman's hypothetical especially alarmed Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the American South. In the 19th century, they were the definitive pro-slavery wing of the party, opposed to both the anti-slavery Republicans and the more liberal Northern Democrats.Eventually "Redemption" was finalized in...

who had gone to great lengths to obstruct Federal action targeted at ending the Jim Crow

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws in the United States enacted between 1876 and 1965. They mandated de jure racial segregation in all public facilities, with a supposedly "separate but equal" status for black Americans...

system of racial segregation

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

in the American South. They feared that, if ratified, the Genocide Convention could be used in conjunction with the Constitution's Necessary and Proper Clause to pass a Federal civil rights law (despite the conservative view that such a law would go beyond the enumerated powers

Enumerated powers

The enumerated powers are a list of items found in Article I, section 8 of the US Constitution that set forth the authoritative capacity of the United States Congress. In summary, Congress may exercise the powers that the Constitution grants it, subject to explicit restrictions in the Bill of...

of Article I, Section 8.) President Eisenhower's aide Arthur Larson

Arthur Larson

Lewis Arthur Larson was an American lawyer, law professor, United States Under Secretary of Labor from 1954 to 1956, director of the United States Information Agency from 1956 to 1957, and Executive Assistant to the President for Speeches from 1957 to 1958.Lewis Arthur Larson was born in Sioux...

said Holman's warnings were part of "all kinds of preposterous and legally lunatic scares [that] were raised," including "that the International Court

International Court of Justice

The International Court of Justice is the primary judicial organ of the United Nations. It is based in the Peace Palace in The Hague, Netherlands...

would take over our tariff and immigration controls, and then our education, post offices, military and welfare activities." In Holman's own book advancing the Bricker Amendment he wrote the U.N. Charter meant the Federal government could:

control and regulate all education, including public and parochial schools, it could control and regulate all matters affecting civil rights, marriage, divorce, etc; it could control all our sources of production of foods and the products of the farms and factories; . . . it could regiment labor and conditions of employment.

Legal background

The United States ConstitutionUnited States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It is the framework for the organization of the United States government and for the relationship of the federal government with the states, citizens, and all people within the United States.The first three...

, effective in 1789, gave the Federal government

Federal government of the United States

The federal government of the United States is the national government of the constitutional republic of fifty states that is the United States of America. The federal government comprises three distinct branches of government: a legislative, an executive and a judiciary. These branches and...

power over foreign affairs and restricted the individual States' authority in this realm. Article I

Article One of the United States Constitution

Article One of the United States Constitution describes the powers of Congress, the legislative branch of the federal government. The Article establishes the powers of and limitations on the Congress, consisting of a House of Representatives composed of Representatives, with each state gaining or...

, section ten provides, "no State shall enter into any Treaty, Alliance, or Confederation" and that "no State shall, without the Consent of the Congress . . . enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State or with a foreign Power." The Federal government's primacy was made clear in the Supremacy Clause

Supremacy Clause

Article VI, Clause 2 of the United States Constitution, known as the Supremacy Clause, establishes the U.S. Constitution, U.S. Treaties, and Federal Statutes as "the supreme law of the land." The text decrees these to be the highest form of law in the U.S...

of Article VI

Article Six of the United States Constitution

Article Six of the United States Constitution establishes the Constitution and the laws and treaties of the United States made in accordance with it as the supreme law of the land, forbids a religious test as a requirement for holding a governmental position and holds the United States under the...

, which declares, "This Constitution, and the laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the Supreme Law of the land; and the Judges in every state shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding." While executive agreements were not mentioned in the Constitution, Congress authorized them for delivery of the mail as early as 1792.

Early precedents

Constitutional scholars note that the supremacy clause was designed to protect the only significant treaty into which the infant United States had entered: the Treaty of ParisTreaty of Paris (1783)

The Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783, ended the American Revolutionary War between Great Britain on the one hand and the United States of America and its allies on the other. The other combatant nations, France, Spain and the Dutch Republic had separate agreements; for details of...

of 1783, which ended the Revolutionary War

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

and under which Great Britain

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

recognized the thirteen former colonies as thirteen independent and fully sovereign states. Nonetheless, its wording ignited fear of the potential abuse of the treaty power from the beginning. For example, the North Carolina

North Carolina

North Carolina is a state located in the southeastern United States. The state borders South Carolina and Georgia to the south, Tennessee to the west and Virginia to the north. North Carolina contains 100 counties. Its capital is Raleigh, and its largest city is Charlotte...

ratifying convention that approved the Constitution did so with a reservation asking for a constitutional amendment that

No treaties which shall be directly opposed to the existing laws of the United States in Congress assembled shall be valid until such laws shall be repealed, or made conformable to such treaty; nor shall any treaty be valid which is contradictory to the Constitution of the United States.

Early legal precedents striking down State laws that conflicted with Federally-negotiated international treaties arose from the peace treaty with Britain, but subsequent treaties were found to trump city ordinances, state laws on escheat

Escheat

Escheat is a common law doctrine which transfers the property of a person who dies without heirs to the crown or state. It serves to ensure that property is not left in limbo without recognised ownership...

of land owned by foreigners and, in the 20th Century, state laws regarding tort claims. Subsequently, in a case involving a treaty concluded with the Cherokee

Cherokee

The Cherokee are a Native American people historically settled in the Southeastern United States . Linguistically, they are part of the Iroquoian language family...

Indians, the Supreme Court declared "It need hardly be said that a treaty cannot change the Constitution or be held valid if it be in violation of that instrument. This results from the nature and fundamental principles of our government. The effect of treaties and acts of Congress, when in conflict, is not settled by the Constitution. But the question is not involved in any doubt as to its proper solution. A treaty may supersede a prior act of Congress, and an act of Congress may supersede a prior treaty."

Likewise, in a case regarding ownership of land by foreign nationals, the Court wrote "The treaty power, as expressed in the constitution, is in terms unlimited, except by those restraints which are found in that instrument against the action of the government, or of its departments, and those arising from the nature of the government itself, and of that of the states. It would not be contended that it extends so far as to authorize what the constitution forbids, or a change in the character of the government, or in that of one of the states, or a cession of any portion of the territory of the latter, without its consent. But, with these exceptions, it is not perceived that there is any limit to the questions which can be adjusted touching any matter which is properly the subject of negotiation with a foreign country." Justice Stephen Johnson Field

Stephen Johnson Field

Stephen Johnson Field was an American jurist. He was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court of the United States Supreme Court from May 20, 1863, to December 1, 1897...

, dissenting in an 1898 immigration case, wrote, "that statutes enacted by Congress, as well as treaties made by the president and senate, must yield to the paramount and supreme law of the constitution."

However, these prior statements seemed to be overruled by the Court's 1920 decision in Missouri v. Holland

Missouri v. Holland

Missouri v. Holland, 252 U.S. 416 , the United States Supreme Court held that protection of its quasi-sovereign right to regulate the taking of game is a sufficient jurisdictional basis, apart from any pecuniary interest, for a bill by a State to enjoin enforcement of federal regulations over the...

.

Missouri v. Holland

Bird migration

Bird migration is the regular seasonal journey undertaken by many species of birds. Bird movements include those made in response to changes in food availability, habitat or weather. Sometimes, journeys are not termed "true migration" because they are irregular or in only one direction...

by statute, but federal and state courts declared the law unconstitutional

Constitutionality

Constitutionality is the condition of acting in accordance with an applicable constitution. Acts that are not in accordance with the rules laid down in the constitution are deemed to be ultra vires.-See also:*ultra vires*Company law*Constitutional law...

. The United States subsequently negotiated and ratified a treaty with Canada to achieve the same purpose, Congress then passed the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918

Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 , codified at , is a United States federal law, at first enacted in 1916 in order to implement the convention for the protection of migratory birds between the United States and Great Britain...

to enforce it. In Missouri v. Holland, the United States Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

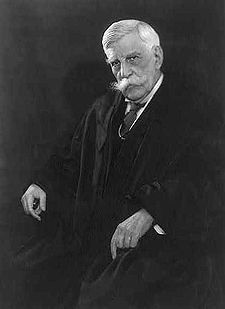

upheld the constitutionality of the new law. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1902 to 1932...

, writing for the Court, declared:

Acts of Congress are the supreme law of the land only when made in pursuance of the Constitution, while treaties are declared to be so when made under the authority of the United States. It is open to question whether the authority of the United States means more than the formal acts prescribed to make the convention. We do not mean to imply that there are no qualifications to the treaty-making power; but they must be ascertained in a different way. It is obvious that there may be matters of the sharpest exigency for the national well being that an act of Congress could not deal with but that a treaty followed by such an act could, and it is not lightly to be assumed that, in matters requiring national action, 'a power which must belong to and somewhere reside in every civilized government' is not to be found.

Proponents of the Bricker Amendment said this language made it essential to add to the Constitution explicit limitations on the treaty-making power. Raymond Moley

Raymond Moley

Raymond Charles Moley was a leading New Dealer who became its bitter opponent before the end of the Great Depression....

wrote in 1953 that Holland meant "the protection of an international duck takes precedence over the constitutional protections of American citizens." In response, legal scholars such as Professor Edward Samuel Corwin

Edward Samuel Corwin

Edward Samuel Corwin was president of the American Political Science Association.-Biography:He was born in Plymouth, Michigan on January 19, 1878. He received his undergraduate degree from the University of Michigan in 1900; and his Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in 1905...

of Princeton University

Princeton University

Princeton University is a private research university located in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. The school is one of the eight universities of the Ivy League, and is one of the nine Colonial Colleges founded before the American Revolution....

said the language of the Constitution regarding treaties—"under the authority of the United States"—was misunderstood by Holmes, and was written to protect the 1783 peace treaty with Britain; this became "in part the source of Senator Bricker's agitation." Professor Zechariah Chafee

Zechariah Chafee

Zechariah Chafee, Jr. was an American judicial philosopher and civil libertarian. An advocate for free speech, he was described by Senator Joseph McCarthy as "dangerous" to the United States...

, of Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School is one of the professional graduate schools of Harvard University. Located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, it is the oldest continually-operating law school in the United States and is home to the largest academic law library in the world. The school is routinely ranked by the U.S...

wrote "the Framers

Founding Fathers of the United States

The Founding Fathers of the United States of America were political leaders and statesmen who participated in the American Revolution by signing the United States Declaration of Independence, taking part in the American Revolutionary War, establishing the United States Constitution, or by some...

never talked about having treaties on the same level as the Constitution. What they did want was to make sure a state could no longer flout any lawful action taken by the nation." "Supreme", as used in Article VI, Chafee claimed, "means simply supreme over the states."

Pink and Belmont

Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

's recognition of the Soviet

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

government in 1933. In the course of recognizing the USSR, letters were exchanged with the Soviet Union's foreign minister, Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Litvinov

Maxim Maximovich Litvinov was a Russian revolutionary and prominent Soviet diplomat.- Early life and first exile :...

, to settle claims between the two countries, in an agreement neither sent to the Senate nor ratified by it. In Belmont v. United States the constitutionality of executive agreements was tested in the Supreme Court. Justice George Sutherland

George Sutherland

Alexander George Sutherland was an English-born U.S. jurist and political figure. One of four appointments to the Supreme Court by President Warren G. Harding, he served as an Associate Justice of the U.S...

, writing for the majority, upheld the power of the president, finding:

That the negotiations, acceptance of the assignment and agreements and understandings in respect thereof were within the competence of the President may not be doubted. Governmental power over external affairs is not distributed, but is vested exclusively in the national government. And in respect of what was done here, the Executive had authority to speak as the sole organ of that government. The assignment and the agreements in connection therewith did not, as in the case of treaties, as that term is used in the treaty making clause of the Constitution (article 2, 2), require the advice and consent of the Senate.

A second case from the Litvinov agreement, United States v. Pink, also went to the Supreme Court. In Pink, the New York State Superintendent of Insurance was ordered to turn over assets belonging to a Russian insurance company pursuant to the Litvinov assignment. The United States sued New York to claim the money held by the Insurance Superintendent, and lost in lower courts. However, the Supreme Court held New York was interfering with the President's exclusive power over foreign affairs, independent of any language in the Constitution—a doctrine it enunciated in United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp.

United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp.

United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp., 299 U.S. 304 , was a United States Supreme Court case involving principles of both governmental regulation of business and the supremacy of the executive branch of the federal government to conduct foreign affairs.-The Facts:In Curtiss-Wright, the...

—and ordered New York to pay the money to the Federal Government. The Court declared, "the Fifth Amendment

Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which is part of the Bill of Rights, protects against abuse of government authority in a legal procedure. Its guarantees stem from English common law which traces back to the Magna Carta in 1215...

does not stand in the way of giving full force and effect to the Litvinov Assignment" and

The powers of the President in the conduct of foreign relations included the power, without consent of the Senate, to determine the public policy of the United States with respect to the Russian nationalization decrees. What government is to be regarded here as representative of a foreign sovereign state is a political rather than a judicial question, and is to be determined by the political department of the government. That authority is not limited to a determination of the government to be recognized. It includes the power to determine the policy which is to govern the question of recognition. Objections to the underlying policy as well as objections to recognition are to be addressed to the political department and not to the courts.

Rulings during Congressional debate

Unlike in Pink and Belmont, an executive agreement on potatoPotato

The potato is a starchy, tuberous crop from the perennial Solanum tuberosum of the Solanaceae family . The word potato may refer to the plant itself as well as the edible tuber. In the region of the Andes, there are some other closely related cultivated potato species...

imports from Canada, litigated in United States v. Guy W. Capps, Inc., another oft cited case, the courts declared an agreement unenforceable. In Capps the courts found that the agreement, which directly contradicted a statute passed by Congress, could not be enforced.

But the dissent of Chief Justice

Chief Justice of the United States

The Chief Justice of the United States is the head of the United States federal court system and the chief judge of the Supreme Court of the United States. The Chief Justice is one of nine Supreme Court justices; the other eight are the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States...

Fred M. Vinson

Fred M. Vinson

Frederick Moore Vinson served the United States in all three branches of government and was the most prominent member of the Vinson political family. In the legislative branch, he was an elected member of the United States House of Representatives from Louisa, Kentucky, for twelve years...

in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer

Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, , also commonly referred to as The Steel Seizure Case, was a United States Supreme Court decision that limited the power of the President of the United States to seize private property in the absence of either specifically enumerated authority under Article...

(commonly referred to as the "steel seizure case") alarmed conservatives. President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

had nationalize

Nationalization

Nationalisation, also spelled nationalization, is the process of taking an industry or assets into government ownership by a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to private assets, but may also mean assets owned by lower levels of government, such as municipalities, being...

d the American Steel

Steel

Steel is an alloy that consists mostly of iron and has a carbon content between 0.2% and 2.1% by weight, depending on the grade. Carbon is the most common alloying material for iron, but various other alloying elements are used, such as manganese, chromium, vanadium, and tungsten...

industry to prevent a strike

Strike action

Strike action, also called labour strike, on strike, greve , or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became important during the industrial revolution, when mass labour became...

he claimed would interfere with the prosecution of the Korean War

Korean War

The Korean War was a conventional war between South Korea, supported by the United Nations, and North Korea, supported by the People's Republic of China , with military material aid from the Soviet Union...

. Though the United States Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

found this illegal, Vinson's defense of this sweeping exercise of executive authority was used to justify the Bricker Amendment. Those warning of "treaty law" claimed that in the future, Americans could be endangered with the use of the executive powers Vinson supported.

State precedents

Some state courts issued rulings in the 1940s and 1950s that relied on the United Nations CharterUnited Nations Charter

The Charter of the United Nations is the foundational treaty of the international organization called the United Nations. It was signed at the San Francisco War Memorial and Performing Arts Center in San Francisco, United States, on 26 June 1945, by 50 of the 51 original member countries...

, much to the alarm of Holman and others. In Fujii v. California, a California law restricting the ownership of land by aliens was ruled by a state appeals court to be a violation of the U.N. Charter. In Fujii, the Court declared "The Charter has become 'the supreme Law of the Land . . . any Thing in the Constitution of Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.' The position of this country in the family of nations forbids trafficking innocuous generalities but demands that every State in the Union accept and act upon the Charter according to its plain language and its unmistakable purpose and intent." However, the California Supreme Court

Supreme Court of California

The Supreme Court of California is the highest state court in California. It is headquartered in San Francisco and regularly holds sessions in Los Angeles and Sacramento. Its decisions are binding on all other California state courts.-Composition:...

overruled, declaring that while the Charter was "entitled to respectful consideration by the courts and Legislatures of every member nation," it was "not intended to supersede existing domestic legislation." Similarly, a New York trial court refused to consider the U.N. Charter in an effort to strike down racially restrictive covenants

Restrictive covenant

A restrictive covenant is a type of real covenant, a legal obligation imposed in a deed by the seller upon the buyer of real estate to do or not to do something. Such restrictions frequently "run with the land" and are enforceable on subsequent buyers of the property...

in housing, declaring "these treaties have nothing to do with domestic matters," citing Article 2, Section 7 of the Charter. In another covenant case, the Michigan Supreme Court

Michigan Supreme Court

The Michigan Supreme Court is the highest court in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is known as Michigan's "court of last resort" and consists of seven justices who are elected to eight-year terms. Candidates are nominated by political parties and are elected on a nonpartisan ballot...

discounted efforts to use the Charter, saying "these pronouncements are merely indicative of a desirable social trend and an objective devoutly to be desired by all well-thinking peoples." These words were quoted with approval by the Iowa Supreme Court

Iowa Supreme Court

The Iowa Supreme Court is the highest court in the U.S. state of Iowa. As constitutional head of the Iowa Judicial Branch, the Court is composed of a Chief Justice and six Associate Justices....

in overturning a lower court decision that relied on the Charter, noting the Charter's principles "do not have the force or effect of superseding our laws."

Internationalization and the United Nations

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, various treaties were proposed under the aegis of the United Nations, in the spirit of collective security

Collective security

Collective security can be understood as a security arrangement, regional or global, in which each state in the system accepts that the security of one is the concern of all, and agrees to join in a collective response to threats to, and breaches of, the peace...

and internationalism that followed the global conflict of the preceding years. In particular, the Genocide Convention, which made a crime of "causing serious mental harm" to "a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group" and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which contained sweeping language about health care

Health care

Health care is the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease, illness, injury, and other physical and mental impairments in humans. Health care is delivered by practitioners in medicine, chiropractic, dentistry, nursing, pharmacy, allied health, and other care providers...

, employment

Employment

Employment is a contract between two parties, one being the employer and the other being the employee. An employee may be defined as:- Employee :...

, vacations

Annual leave

Annual leave is paid time off work granted by employers to employees to be used for whatever the employee wishes. Depending on the employer's policies, differing number of days may be offered, and the employee may be required to give a certain amount of advance notice, may have to coordinate with...

, and other subjects outside the traditional scope of treaties, were considered problematic by non-interventionists and advocates of limited government

Limited government

Limited government is a government which anything more than minimal governmental intervention in personal liberties and the economy is generally disallowed by law, usually in a written constitution. It is written in the United States Constitution in Article 1, Section 8...

. Historian Stephen Ambrose

Stephen Ambrose

Stephen Edward Ambrose was an American historian and biographer of U.S. Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower and Richard Nixon. He was a long time professor of history at the University of New Orleans and the author of many best selling volumes of American popular history...

described the suspicions of Americans: "Southern leaders feared that the U.N. commitment to human rights would imperil segregation; the American Medical Association

American Medical Association

The American Medical Association , founded in 1847 and incorporated in 1897, is the largest association of medical doctors and medical students in the United States.-Scope and operations:...

feared it would bring about socialized medicine

Socialized medicine

Socialized medicine is a term used to describe a system for providing medical and hospital care for all at a nominal cost by means of government regulation of health services and subsidies derived from taxation. It is used primarily and usually pejoratively in United States political debates...

." It was, the American Bar Association

American Bar Association

The American Bar Association , founded August 21, 1878, is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. The ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of academic standards for law schools, and the formulation...

declared, "one of the greatest constitutional crises the country has ever faced."

Conservatives were worried that these treaties could be used to expand the power of the Federal government at the expense of the people and the states. In a speech to the American Bar Association

American Bar Association

The American Bar Association , founded August 21, 1878, is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. The ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of academic standards for law schools, and the formulation...

's regional meeting at Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the largest city in the U.S. state of Kentucky, and the county seat of Jefferson County. Since 2003, the city's borders have been coterminous with those of the county because of a city-county merger. The city's population at the 2010 census was 741,096...

on April 11, 1952, John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles

John Foster Dulles served as U.S. Secretary of State under President Dwight D. Eisenhower from 1953 to 1959. He was a significant figure in the early Cold War era, advocating an aggressive stance against communism throughout the world...

, an American delegate to the United Nations

United Nations

The United Nations is an international organization whose stated aims are facilitating cooperation in international law, international security, economic development, social progress, human rights, and achievement of world peace...

, said, "Treaties make international law and they also make domestic law. Under our Constitution, treaties become the Supreme Law of the Land. They are indeed more supreme than ordinary laws, for Congressional laws are invalid if they do not conform to the Constitution, whereas treaty laws can override the Constitution." Dulles said the power to make treaties "is an extraordinary power liable to abuse." Senator Everett Dirksen

Everett Dirksen

Everett McKinley Dirksen was an American politician of the Republican Party. He represented Illinois in the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate...

, a Republican of Illinois

Illinois

Illinois is the fifth-most populous state of the United States of America, and is often noted for being a microcosm of the entire country. With Chicago in the northeast, small industrial cities and great agricultural productivity in central and northern Illinois, and natural resources like coal,...

, declared, "we are in a new era of international organizations. They are grinding out treaties like so many eager beavers which will have effects on the rights of American citizens." Eisenhower's Attorney General

United States Attorney General

The United States Attorney General is the head of the United States Department of Justice concerned with legal affairs and is the chief law enforcement officer of the United States government. The attorney general is considered to be the chief lawyer of the U.S. government...

Herbert Brownell

Herbert Brownell, Jr.

Herbert Brownell, Jr. was the Attorney General of the United States in President Eisenhower's cabinet from 1953 to 1957.-Early life:...

admitted executive agreements "had sometimes been abused in the past." Frank E. Holman wrote Secretary of State

United States Secretary of State

The United States Secretary of State is the head of the United States Department of State, concerned with foreign affairs. The Secretary is a member of the Cabinet and the highest-ranking cabinet secretary both in line of succession and order of precedence...

George Marshall

George Marshall

George Catlett Marshall was an American military leader, Chief of Staff of the Army, Secretary of State, and the third Secretary of Defense...

in November 1948 regarding the dangers of the Human Rights Declaration, receiving the dismissive reply that the agreement was "merely declaratory in character" and had no legal effect. The conservative ABA called for a Constitutional amendment to address what they perceived to be a potential abuse of executive power. Holman described the threat:

More or less coincident with the organization of the United Nations a new form of internationalism arose which undertook to enlarge the historical concept of international law and treaties to have them include and deal with the domestic affairs and internal laws of independent nations.

Senator Bricker thought the "one world" movement

Transnational progressivism

Transnational progressivism is a term coined by Hudson Institute Fellow John Fonte in 2001 to describe an ideology that endorses a concept of postnational global citizenship and promotes the authority of international institutions over the sovereignty of individual nation-states.-Overview:Fonte...

advocated by those such as Wendell Willkie

Wendell Willkie

Wendell Lewis Willkie was a corporate lawyer in the United States and a dark horse who became the Republican Party nominee for the president in 1940. A member of the liberal wing of the GOP, he crusaded against those domestic policies of the New Deal that he thought were inefficient and...

, Roosevelt's Republican challenger in the 1940 election

United States presidential election, 1940

The United States presidential election of 1940 was fought in the shadow of World War II as the United States was emerging from the Great Depression. Incumbent President Franklin D. Roosevelt , a Democrat, broke with tradition and ran for a third term, which became a major issue...

, would attempt to use treaties to undermine American liberties. Conservatives cited as evidence the statement of John P. Humphrey, the first director of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights

United Nations Commission on Human Rights

The United Nations Commission on Human Rights was a functional commission within the overall framework of the United Nations from 1946 until it was replaced by the United Nations Human Rights Council in 2006...

:

What the United Nations is trying to do is revolutionary in character. Human rightsHuman rightsHuman rights are "commonly understood as inalienable fundamental rights to which a person is inherently entitled simply because she or he is a human being." Human rights are thus conceived as universal and egalitarian . These rights may exist as natural rights or as legal rights, in both national...