Fred M. Vinson

Encyclopedia

Frederick Moore Vinson (January 22, 1890 – September 8, 1953) served the United States

in all three branches of government and was the most prominent member of the Vinson political family. In the legislative branch, he was an elected member of the United States House of Representatives

from Louisa, Kentucky

, for twelve years. In the executive branch, he was the Secretary of Treasury under President Harry S. Truman

. In the judicial branch, he was the 13th Chief Justice of the United States

, appointed by President Truman.

jail, Louisa

, Kentucky

, where his father served as the Lawrence County Jailer. As a child he would help his father in the jail and even made friends with prisoners who would remember his kindness when he later ran for public office. Vinson worked odd jobs while in school. He graduated from Kentucky Normal School in 1908 and enrolled at Centre College

, where he graduated at the top of his class. While at Centre, he was a member of the Kentucky Alpha Delta chapter of Phi Delta Theta

fraternity. He became a lawyer

in Louisa

, a small town of 2,500 residents. He first ran for, and was elected to, office as the City Attorney of Louisa.

He joined the Army during World War I

. Following the war, he was elected as the Commonwealth's Attorney

for the Thirty-Second Judicial District of Kentucky.

resigned to become the governor of Kentucky

. Vinson was elected as a Democrat and then was reelected twice before losing in 1928. His loss was attributed to his refusal to dissociate his campaign from Alfred E. Smith

's presidential campaign. However, Vinson came back to win re-election in 1930, and he served in Congress through 1937.

While he was in Congress he befriended Missouri

Senator Harry S. Truman

, a friendship that would last throughout his life. He soon became a close advisor, confidante, card player, and dear friend to Truman. After Truman decided against running for another term as president in the early 1950s, he tried to convince a skeptical Vinson to seek the Democratic Party nomination, but Vinson turned down the President's offer. After being equally unsuccessful in enlisting General Dwight D. Eisenhower

, President Truman eventually landed on Governor of Illinois

Adlai Stevenson as his preferred successor in the 1952 presidential election.

on November 26, 1937, to the federal bench. Roosevelt wanted him to fill a seat vacated by Charles H. Robb on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit

. While he was there, he was designated by Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone

on March 2, 1942, as chief judge of the United States Emergency Court of Appeals. He served here until his resignation on May 27, 1943.

He resigned from the bench to become Director of the Office of Economic Stabilization

He resigned from the bench to become Director of the Office of Economic Stabilization

, an executive agency charged with fighting inflation

. He also spent time as Federal Loan Administrator (March 6 to April 3, 1945) and director of War Mobilization and Reconversion (April 4 to July 22, 1945). He was appointed United States Secretary of the Treasury

by President Truman and served from July 23, 1945, to June 23, 1946.

His mission as Secretary of the Treasury was to stabilize the American economy during the last months of the war and to adapt the United States financial position to the drastically changed circumstances of the postwar world. Before the war ended, Vinson directed the last of the great war-bond

drives.

At the end of the war, he negotiated payment of the British Loan of 1946, the largest loan made by the United States to another country ($3.75 billion), and the lend-lease

settlements of economic and military aid given to the allies during the war. In order to encourage private investment in postwar America, he promoted a tax cut in the Revenue Act of 1945

. He also supervised the inauguration of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development

and the International Monetary Fund

, both created at the Bretton Woods Conference

of 1944, acting as the first chairman of their respective boards. In 1946, Vinson resigned from the Treasury to be appointed Chief Justice of the United States

by Truman; the Senate

confirmed him by voice vote on June 20 of that year (E. H. Moore

had expressed opposition but was not present for the vote).

died. See Harry S. Truman Supreme Court candidates

. His appointment came at a time when the Supreme Court

was deeply fractured, both intellectually and personally. One faction was led by Justice Hugo Black

, the other by Justice Felix Frankfurter

. Some of the justices would not even speak to one another. Vinson was credited with patching this fracture, at least on a personal level.

In his time on the Supreme Court, he wrote 77 opinions for the court and 13 dissents

In his time on the Supreme Court, he wrote 77 opinions for the court and 13 dissents

. His most dramatic dissent was when the court voided President Truman's seizure of the steel industry during a strike in a June 3, 1952 decision, Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer. His final public appearance at the court was when he read the decision not to review the conviction and death sentence of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

. After Justice William O. Douglas

granted a stay of execution to the Rosenbergs at the last moment, Chief Justice Vinson sent special flights out to bring vacationing justices back to Washington in order to ensure the execution of the Rosenbergs. The Vinson court also gained infamy for its refusal to hear the appeal of the Hollywood Ten in their 1947 contempt of congress charge. As a result, all ten would serve a year in jail for invoking their First Amendment right of free association before J. Parnell Thomas and the House Un-American Activities Committee

(HUAC). During his tenure as Chief Justice, one of his law clerk

s was future Associate Justice Byron White

.

The major issues his court dealt with included racial segregation

, labor unions, communism

and loyalty oath

s. On racial segregation, he wrote that states practicing the separate but equal

doctrine must provide facilities that were truly equal, in Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents. The case of Briggs et al v. Clarendon County School District was before the Court at the time of his death. Vinson, not wanting a 5-4 decision, had ordered a second hearing of the case. He died before the case could be reheard, and his vote may have been pivotal. See Felix Frankfurter

. Upon his death Earl Warren

was appointed to the Court and the case was heard again.

As Chief Justice, he swore in Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower

as Presidents.

As of 2011, Vinson is the last Chief Justice to be appointed by a Democratic President, namely Harry Truman. His successors, Earl Warren

, Warren Burger, William Rehnquist

and John Roberts were all appointed by Republican presidents (Dwight D. Eisenhower

, Richard Nixon

, Ronald Reagan

, and George W. Bush

, respectively).

came under fire from congressional Republicans for being "soft on communism" at the end of 1950 Vinson was briefly mentioned as the new Secretary of State and Dean Acheson as the new Chief Justice. This speculation died down when President Truman retained Acheson at the State Department.

, in 1924. They had two sons: Frederick Vinson, Jr. and James Vinson. Frederick Vinson Jr. married Nell Morrison and they had two children named Frederick Vinson III and Carolyn Pharr Vinson. James Vinson married Margaret Russell and they had four children named James Robert, Margaret, Michael Arthur and Matthew Dixon.

early on the morning of September 8, 1953; his body is interred in Pinehill Cemetery, Louisa, Kentucky

.

An extensive collection of Vinson's personal and judicial papers is archived at the University of Kentucky

in Lexington

, where they are available for research.

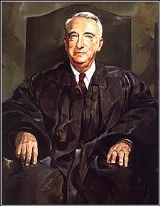

A portrait of Vinson hangs in the hallway of the chapter house of the Kentucky Alpha-Delta chapter of Phi Delta Theta

(ΦΔΘ) international fraternity

, at Centre College. Vinson was a member of the chapter in his years at Centre. Affectionately known as "Dead Fred", the portrait is taken by fraternity members to Centre football and basketball games and other events.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

in all three branches of government and was the most prominent member of the Vinson political family. In the legislative branch, he was an elected member of the United States House of Representatives

United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is one of the two Houses of the United States Congress, the bicameral legislature which also includes the Senate.The composition and powers of the House are established in Article One of the Constitution...

from Louisa, Kentucky

Louisa, Kentucky

Louisa is a city in Lawrence County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 2,018 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Lawrence County. The Levisa Fork River and Tug Fork River join at Louisa to form the Big Sandy River...

, for twelve years. In the executive branch, he was the Secretary of Treasury under President Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

. In the judicial branch, he was the 13th Chief Justice of the United States

Chief Justice of the United States

The Chief Justice of the United States is the head of the United States federal court system and the chief judge of the Supreme Court of the United States. The Chief Justice is one of nine Supreme Court justices; the other eight are the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States...

, appointed by President Truman.

Early years

Frederick Vinson, known universally as "Fred", was born in the newly built, eight-room, red brick house in front of the Lawrence CountyLawrence County, Kentucky

Lawrence County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of 2000, the population was 15,569. Its county seat is Louisa. The county is named for James Lawrence, and co-founded by Isaac Bolt, who served as a Lawrence County Commissioner and Justice of the Peace. It is the home of...

jail, Louisa

Louisa, Kentucky

Louisa is a city in Lawrence County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 2,018 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Lawrence County. The Levisa Fork River and Tug Fork River join at Louisa to form the Big Sandy River...

, Kentucky

Kentucky

The Commonwealth of Kentucky is a state located in the East Central United States of America. As classified by the United States Census Bureau, Kentucky is a Southern state, more specifically in the East South Central region. Kentucky is one of four U.S. states constituted as a commonwealth...

, where his father served as the Lawrence County Jailer. As a child he would help his father in the jail and even made friends with prisoners who would remember his kindness when he later ran for public office. Vinson worked odd jobs while in school. He graduated from Kentucky Normal School in 1908 and enrolled at Centre College

Centre College

Centre College is a private liberal arts college in Danville, Kentucky, USA, a community of approximately 16,000 in Boyle County south of Lexington, KY. Centre is an exclusively undergraduate four-year institution. Centre was founded by Presbyterian leaders, with whom it maintains a loose...

, where he graduated at the top of his class. While at Centre, he was a member of the Kentucky Alpha Delta chapter of Phi Delta Theta

Phi Delta Theta

Phi Delta Theta , also known as Phi Delt, is an international fraternity founded at Miami University in 1848 and headquartered in Oxford, Ohio. Phi Delta Theta, Beta Theta Pi, and Sigma Chi form the Miami Triad. The fraternity has about 169 active chapters and colonies in over 43 U.S...

fraternity. He became a lawyer

Lawyer

A lawyer, according to Black's Law Dictionary, is "a person learned in the law; as an attorney, counsel or solicitor; a person who is practicing law." Law is the system of rules of conduct established by the sovereign government of a society to correct wrongs, maintain the stability of political...

in Louisa

Louisa, Kentucky

Louisa is a city in Lawrence County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 2,018 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Lawrence County. The Levisa Fork River and Tug Fork River join at Louisa to form the Big Sandy River...

, a small town of 2,500 residents. He first ran for, and was elected to, office as the City Attorney of Louisa.

He joined the Army during World War I

World War I

World War I , which was predominantly called the World War or the Great War from its occurrence until 1939, and the First World War or World War I thereafter, was a major war centred in Europe that began on 28 July 1914 and lasted until 11 November 1918...

. Following the war, he was elected as the Commonwealth's Attorney

Commonwealth's Attorney

Commonwealth's Attorney is the title given to the elected prosecutor of felony crimes in Kentucky and Virginia. Other states refer to similar prosecutors as District Attorney or State's Attorney....

for the Thirty-Second Judicial District of Kentucky.

U.S. Representative from Kentucky

In 1924, he ran in a special election for his district's seat in Congress after William J. FieldsWilliam J. Fields

William Jason Fields was a politician from the U.S. state of Kentucky. Known as "Honest Bill from Olive Hill", he represented Kentucky's Ninth District in the U.S...

resigned to become the governor of Kentucky

Governor of Kentucky

The Governor of the Commonwealth of Kentucky is the head of the executive branch of government in the U.S. state of Kentucky. Fifty-six men and one woman have served as Governor of Kentucky. The governor's term is four years in length; since 1992, incumbents have been able to seek re-election once...

. Vinson was elected as a Democrat and then was reelected twice before losing in 1928. His loss was attributed to his refusal to dissociate his campaign from Alfred E. Smith

Al Smith

Alfred Emanuel Smith. , known in private and public life as Al Smith, was an American statesman who was elected the 42nd Governor of New York three times, and was the Democratic U.S. presidential candidate in 1928...

's presidential campaign. However, Vinson came back to win re-election in 1930, and he served in Congress through 1937.

While he was in Congress he befriended Missouri

Missouri

Missouri is a US state located in the Midwestern United States, bordered by Iowa, Illinois, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska. With a 2010 population of 5,988,927, Missouri is the 18th most populous state in the nation and the fifth most populous in the Midwest. It...

Senator Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman

Harry S. Truman was the 33rd President of the United States . As President Franklin D. Roosevelt's third vice president and the 34th Vice President of the United States , he succeeded to the presidency on April 12, 1945, when President Roosevelt died less than three months after beginning his...

, a friendship that would last throughout his life. He soon became a close advisor, confidante, card player, and dear friend to Truman. After Truman decided against running for another term as president in the early 1950s, he tried to convince a skeptical Vinson to seek the Democratic Party nomination, but Vinson turned down the President's offer. After being equally unsuccessful in enlisting General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

, President Truman eventually landed on Governor of Illinois

Governor of Illinois

The Governor of Illinois is the chief executive of the State of Illinois and the various agencies and departments over which the officer has jurisdiction, as prescribed in the state constitution. It is a directly elected position, votes being cast by popular suffrage of residents of the state....

Adlai Stevenson as his preferred successor in the 1952 presidential election.

U.S. Court of Appeals

Vinson's Congressional service ended after he was nominated by Franklin D. RooseveltFranklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt , also known by his initials, FDR, was the 32nd President of the United States and a central figure in world events during the mid-20th century, leading the United States during a time of worldwide economic crisis and world war...

on November 26, 1937, to the federal bench. Roosevelt wanted him to fill a seat vacated by Charles H. Robb on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit

United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit known informally as the D.C. Circuit, is the federal appellate court for the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. Appeals from the D.C. Circuit, as with all the U.S. Courts of Appeals, are heard on a...

. While he was there, he was designated by Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone

Harlan Fiske Stone

Harlan Fiske Stone was an American lawyer and jurist. A native of New Hampshire, he served as the dean of Columbia Law School, his alma mater, in the early 20th century. As a member of the Republican Party, he was appointed as the 52nd Attorney General of the United States before becoming an...

on March 2, 1942, as chief judge of the United States Emergency Court of Appeals. He served here until his resignation on May 27, 1943.

Secretary of Treasury

Office of Economic Stabilization

The Office of Economic Stabilization was established within the United States Office for Emergency Management on October 3, 1942, pursuant to the Stabilization Act of 1942, as a means to control inflation during World War II through regulations on price, wage, and salary increases.-Directors:*...

, an executive agency charged with fighting inflation

Inflation

In economics, inflation is a rise in the general level of prices of goods and services in an economy over a period of time.When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services. Consequently, inflation also reflects an erosion in the purchasing power of money – a...

. He also spent time as Federal Loan Administrator (March 6 to April 3, 1945) and director of War Mobilization and Reconversion (April 4 to July 22, 1945). He was appointed United States Secretary of the Treasury

United States Secretary of the Treasury

The Secretary of the Treasury of the United States is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, which is concerned with financial and monetary matters, and, until 2003, also with some issues of national security and defense. This position in the Federal Government of the United...

by President Truman and served from July 23, 1945, to June 23, 1946.

His mission as Secretary of the Treasury was to stabilize the American economy during the last months of the war and to adapt the United States financial position to the drastically changed circumstances of the postwar world. Before the war ended, Vinson directed the last of the great war-bond

War bond

War bonds are debt securities issued by a government for the purpose of financing military operations during times of war. War bonds generate capital for the government and make civilians feel involved in their national militaries...

drives.

At the end of the war, he negotiated payment of the British Loan of 1946, the largest loan made by the United States to another country ($3.75 billion), and the lend-lease

Lend-Lease

Lend-Lease was the program under which the United States of America supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, China, Free France, and other Allied nations with materiel between 1941 and 1945. It was signed into law on March 11, 1941, a year and a half after the outbreak of war in Europe in...

settlements of economic and military aid given to the allies during the war. In order to encourage private investment in postwar America, he promoted a tax cut in the Revenue Act of 1945

Revenue Act of 1945

The United States Revenue Act of 1945 repealed the excess profits tax, reduced individual income tax rates , and reduced corporate tax rates ....

. He also supervised the inauguration of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development

The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development is one of five institutions that compose the World Bank Group. The IBRD is an international organization whose original mission was to finance the reconstruction of nations devastated by World War II. Now, its mission has expanded to fight...

and the International Monetary Fund

International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund is an organization of 187 countries, working to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty around the world...

, both created at the Bretton Woods Conference

United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference

The United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, commonly known as the Bretton Woods conference, was a gathering of 730 delegates from all 44 Allied nations at the Mount Washington Hotel, situated in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, to regulate the international monetary and financial order after...

of 1944, acting as the first chairman of their respective boards. In 1946, Vinson resigned from the Treasury to be appointed Chief Justice of the United States

Chief Justice of the United States

The Chief Justice of the United States is the head of the United States federal court system and the chief judge of the Supreme Court of the United States. The Chief Justice is one of nine Supreme Court justices; the other eight are the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States...

by Truman; the Senate

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper house of the bicameral legislature of the United States, and together with the United States House of Representatives comprises the United States Congress. The composition and powers of the Senate are established in Article One of the U.S. Constitution. Each...

confirmed him by voice vote on June 20 of that year (E. H. Moore

Edward H. Moore

Edward Hall Moore was a United States Senator from Oklahoma. Born on a farm near Maryville, Missouri, he attended the public schools and Chillicothe Normal School. He taught school in Nodaway, Atchinson, and Jackson Counties, and graduated from the Kansas City School of Law in 1900...

had expressed opposition but was not present for the vote).

Chief Justice

Vinson took the oath of office as Chief Justice on June 24, 1946. President Truman had nominated his old friend after Harlan Fiske StoneHarlan Fiske Stone

Harlan Fiske Stone was an American lawyer and jurist. A native of New Hampshire, he served as the dean of Columbia Law School, his alma mater, in the early 20th century. As a member of the Republican Party, he was appointed as the 52nd Attorney General of the United States before becoming an...

died. See Harry S. Truman Supreme Court candidates

Harry S. Truman Supreme Court candidates

During his two terms in office, President Harry S. Truman appointed four members of the Supreme Court of the United States: Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson, and Associate Justices Harold Burton, Tom C. Clark, and Sherman Minton.-Harold Burton nomination:...

. His appointment came at a time when the Supreme Court

Supreme Court of the United States

The Supreme Court of the United States is the highest court in the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all state and federal courts, and original jurisdiction over a small range of cases...

was deeply fractured, both intellectually and personally. One faction was led by Justice Hugo Black

Hugo Black

Hugo Lafayette Black was an American politician and jurist. A member of the Democratic Party, Black represented Alabama in the United States Senate from 1927 to 1937, and served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1937 to 1971. Black was nominated to the Supreme...

, the other by Justice Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.-Early life:Frankfurter was born into a Jewish family on November 15, 1882, in Vienna, Austria, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Europe. He was the third of six children of Leopold and Emma Frankfurter...

. Some of the justices would not even speak to one another. Vinson was credited with patching this fracture, at least on a personal level.

Dissenting opinion

A dissenting opinion is an opinion in a legal case written by one or more judges expressing disagreement with the majority opinion of the court which gives rise to its judgment....

. His most dramatic dissent was when the court voided President Truman's seizure of the steel industry during a strike in a June 3, 1952 decision, Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer. His final public appearance at the court was when he read the decision not to review the conviction and death sentence of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

Julius and Ethel Rosenberg

Ethel Greenglass Rosenberg and Julius Rosenberg were American communists who were convicted and executed in 1953 for conspiracy to commit espionage during a time of war. The charges related to their passing information about the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union...

. After Justice William O. Douglas

William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court. With a term lasting 36 years and 209 days, he is the longest-serving justice in the history of the Supreme Court...

granted a stay of execution to the Rosenbergs at the last moment, Chief Justice Vinson sent special flights out to bring vacationing justices back to Washington in order to ensure the execution of the Rosenbergs. The Vinson court also gained infamy for its refusal to hear the appeal of the Hollywood Ten in their 1947 contempt of congress charge. As a result, all ten would serve a year in jail for invoking their First Amendment right of free association before J. Parnell Thomas and the House Un-American Activities Committee

House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities or House Un-American Activities Committee was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives. In 1969, the House changed the committee's name to "House Committee on Internal Security"...

(HUAC). During his tenure as Chief Justice, one of his law clerk

Law clerk

A law clerk or a judicial clerk is a person who provides assistance to a judge in researching issues before the court and in writing opinions. Law clerks are not court clerks or courtroom deputies, who are administrative staff for the court. Most law clerks are recent law school graduates who...

s was future Associate Justice Byron White

Byron White

Byron Raymond "Whizzer" White won fame both as a football halfback and as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Appointed to the court by President John F. Kennedy in 1962, he served until his retirement in 1993...

.

The major issues his court dealt with included racial segregation

Racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of humans into racial groups in daily life. It may apply to activities such as eating in a restaurant, drinking from a water fountain, using a public toilet, attending school, going to the movies, or in the rental or purchase of a home...

, labor unions, communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

and loyalty oath

Loyalty oath

A loyalty oath is an oath of loyalty to an organization, institution, or state of which an individual is a member.In this context, a loyalty oath is distinct from pledge or oath of allegiance...

s. On racial segregation, he wrote that states practicing the separate but equal

Separate but equal

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law that justified systems of segregation. Under this doctrine, services, facilities and public accommodations were allowed to be separated by race, on the condition that the quality of each group's public facilities was to...

doctrine must provide facilities that were truly equal, in Sweatt v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents. The case of Briggs et al v. Clarendon County School District was before the Court at the time of his death. Vinson, not wanting a 5-4 decision, had ordered a second hearing of the case. He died before the case could be reheard, and his vote may have been pivotal. See Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.-Early life:Frankfurter was born into a Jewish family on November 15, 1882, in Vienna, Austria, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in Europe. He was the third of six children of Leopold and Emma Frankfurter...

. Upon his death Earl Warren

Earl Warren

Earl Warren was the 14th Chief Justice of the United States.He is known for the sweeping decisions of the Warren Court, which ended school segregation and transformed many areas of American law, especially regarding the rights of the accused, ending public-school-sponsored prayer, and requiring...

was appointed to the Court and the case was heard again.

As Chief Justice, he swore in Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

as Presidents.

As of 2011, Vinson is the last Chief Justice to be appointed by a Democratic President, namely Harry Truman. His successors, Earl Warren

Earl Warren

Earl Warren was the 14th Chief Justice of the United States.He is known for the sweeping decisions of the Warren Court, which ended school segregation and transformed many areas of American law, especially regarding the rights of the accused, ending public-school-sponsored prayer, and requiring...

, Warren Burger, William Rehnquist

William Rehnquist

William Hubbs Rehnquist was an American lawyer, jurist, and political figure who served as an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court of the United States and later as the 16th Chief Justice of the United States...

and John Roberts were all appointed by Republican presidents (Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, from 1953 until 1961. He was a five-star general in the United States Army...

, Richard Nixon

Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon was the 37th President of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. The only president to resign the office, Nixon had previously served as a US representative and senator from California and as the 36th Vice President of the United States from 1953 to 1961 under...

, Ronald Reagan

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan was the 40th President of the United States , the 33rd Governor of California and, prior to that, a radio, film and television actor....

, and George W. Bush

George W. Bush

George Walker Bush is an American politician who served as the 43rd President of the United States, from 2001 to 2009. Before that, he was the 46th Governor of Texas, having served from 1995 to 2000....

, respectively).

Potential cabinet position

When Secretary of State Dean AchesonDean Acheson

Dean Gooderham Acheson was an American statesman and lawyer. As United States Secretary of State in the administration of President Harry S. Truman from 1949 to 1953, he played a central role in defining American foreign policy during the Cold War...

came under fire from congressional Republicans for being "soft on communism" at the end of 1950 Vinson was briefly mentioned as the new Secretary of State and Dean Acheson as the new Chief Justice. This speculation died down when President Truman retained Acheson at the State Department.

Family

Frederick M. Vinson married Roberta Dixon of Ashland, KentuckyAshland, Kentucky

Ashland, formerly known as Poage Settlement, is a city in Boyd County, Kentucky, United States, nestled along the banks of the Ohio River. The population was 21,981 at the 2000 census. Ashland is a part of the Huntington-Ashland, WV-KY-OH, Metropolitan Statistical Area . As of the 2000 census, the...

, in 1924. They had two sons: Frederick Vinson, Jr. and James Vinson. Frederick Vinson Jr. married Nell Morrison and they had two children named Frederick Vinson III and Carolyn Pharr Vinson. James Vinson married Margaret Russell and they had four children named James Robert, Margaret, Michael Arthur and Matthew Dixon.

Death and legacy

Frederick M. Vinson died suddenly and unexpectedly from a heart attackMyocardial infarction

Myocardial infarction or acute myocardial infarction , commonly known as a heart attack, results from the interruption of blood supply to a part of the heart, causing heart cells to die...

early on the morning of September 8, 1953; his body is interred in Pinehill Cemetery, Louisa, Kentucky

Louisa, Kentucky

Louisa is a city in Lawrence County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 2,018 at the 2000 census. It is the county seat of Lawrence County. The Levisa Fork River and Tug Fork River join at Louisa to form the Big Sandy River...

.

An extensive collection of Vinson's personal and judicial papers is archived at the University of Kentucky

University of Kentucky

The University of Kentucky, also known as UK, is a public co-educational university and is one of the state's two land-grant universities, located in Lexington, Kentucky...

in Lexington

Lexington, Kentucky

Lexington is the second-largest city in Kentucky and the 63rd largest in the US. Known as the "Thoroughbred City" and the "Horse Capital of the World", it is located in the heart of Kentucky's Bluegrass region...

, where they are available for research.

A portrait of Vinson hangs in the hallway of the chapter house of the Kentucky Alpha-Delta chapter of Phi Delta Theta

Phi Delta Theta

Phi Delta Theta , also known as Phi Delt, is an international fraternity founded at Miami University in 1848 and headquartered in Oxford, Ohio. Phi Delta Theta, Beta Theta Pi, and Sigma Chi form the Miami Triad. The fraternity has about 169 active chapters and colonies in over 43 U.S...

(ΦΔΘ) international fraternity

Fraternities and sororities

Fraternities and sororities are fraternal social organizations for undergraduate students. In Latin, the term refers mainly to such organizations at colleges and universities in the United States, although it is also applied to analogous European groups also known as corporations...

, at Centre College. Vinson was a member of the chapter in his years at Centre. Affectionately known as "Dead Fred", the portrait is taken by fraternity members to Centre football and basketball games and other events.

See also

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United StatesDemographics of the Supreme Court of the United StatesThe demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States encompass the gender, ethnic, religious, geographic, and economic backgrounds of the 112 justices appointed to the Supreme Court. Certain of these characteristics have been raised as an issue since the Court was established in 1789. For its...

- List of Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Chief Justices by time in office

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- United States Supreme Court cases during the Vinson Court

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J., Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court. 3d. ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992). ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare, The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies,1789-1995 (2nd ed.) (Supreme Court Historical Society), (Congressional Quarterly Books, 2001) ISBN 1-56802-126-7; ISBN 978-1-56802-126-3.

- Frank, John P., The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions (Leon Friedman and Fred L. Israel, editors) (Chelsea House Publishers: 1995) ISBN 0-7910-1377-4, ISBN 978-0-7910-1377-9.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-19-505835-6; ISBN 978-0-19-505835-2.

- Martin, Fenton S. and Goehlert, Robert U., The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography, (Congressional Quarterly Books, 1990). ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Pritchett, C. Herman , Civil Liberties and the Vinson Court. (The University of ChicagoUniversity of ChicagoThe University of Chicago is a private research university in Chicago, Illinois, USA. It was founded by the American Baptist Education Society with a donation from oil magnate and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller and incorporated in 1890...

Press, 1969) ISBN 978-0-226-68443-7; ISBN 0-226-68443-1. - St. Clair, James E., and Gugin, Linda C., Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson of Kentucky: A Political Biography (University Press of KentuckyUniversity Press of KentuckyThe University Press of Kentucky is the scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth of Kentucky, and was organized in 1969 as successor to the University of Kentucky Press. The university had sponsored scholarly publication since 1943. In 1949 the press was established as a separate academic agency...

: 2002) ISBN 0-8131-2247-3; ISBN 978-0-8131-2247-2. - Symposium, In Memoriam: Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson, 49 Northwestern University Law ReviewNorthwestern University Law ReviewThe Northwestern University Law Review is a scholarly legal publication and student organization at Northwestern University School of Law. The Law Review's primary purpose is to publish a journal of broad legal scholarship. The Law Review publishes four issues each year...

1–75, (1954). - Urofsky, Melvin I., Division and Discord: The Supreme Court under Stone and Vinson, 1941-1953 (University of South Carolina Press, 1997) ISBN 1-57003-120-7.

- Urofsky, Melvin I., The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary (New York: Garland Publishing 1994). 590590Year 590 was a common year starting on Sunday of the Julian calendar. The denomination 590 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.- Byzantine Empire :* Summer – Maurice agrees to...

pp. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1; ISBN 978-0-8153-1176-8.