List of Christian thinkers in science

Encyclopedia

This list is about the relationship between religion and science

, but is specific to Christian history. This is only supplementary to the issue as lists are by themselves not equipped to answer questions on this topic. The purpose is to act as a guide: the names, annotations, and links are provided for use in further study on this topic.

The list is non-exhaustive and limited to scientist

s who also contributed to Christian theology

or religious thinking. There are two specific groups of Christians in science not covered in this list. Activities of Catholic scientists who are members of the Society of Jesus

are presented in the List of Jesuit scientists. Scientists who are members of the Religious Society of Friends

are presented in Quakers in science

. This is due space constraints, otherwise the list would become even larger. Both groups made significant contributions to science.

ended Christian persecution in the Roman Empire

. Although this is not the start of Christianity it may well be the start of Christians' recorded achievements in many pursuits, including science.

This period was marked by the process which brought the end of the Roman Empire

. Within the Greek East

half, the ancient schools and institutions

that had been host to natural philosophy dwindled away or were closed. Meanwhile, the Latin West was left with even greater difficulties that affected the continent's intellectual production dramatically. Apart from depopulation and other factors, most scientific treatises of Classical Antiquity

, written in Greek

, had became unavailable, leaving only simplified summaries and compilations.

remained a backwater compared to other world regions: while the population in Constantinople exceeded 300,000, Rome had mere 35,000 inhabitants and Paris only 20,000. This new period, however, saw prosperity and rapidly increasing population

, which brought about great social and political change.

During the Renaissance of the 12th century

, interest in the study of nature was revitalized through an intense translation movement aimed at Greek and Arabic scientific texts. Monastic

and cathedral school

s took a leading role in studying these texts and theorizing over the new insights they brought. At the same time, an important new kind of higher learning institution was being developed: the university

.

were rapidly spreading through Europe and providing a new infrastructure for scientific communities

. They became the main institutions in which the new texts were studied and elaborated. In fact, the medieval university curriculum

laid much more emphasis on scientific knowledge than does its modern descendent. This all lead to innovative scientific work being done, especially in the 14th century.

and other disasters

sealed a sudden end to the previous period of massive philosophic and scientific development. Even during the initial portion of the Renaissance

, the amount of scientific activity remained depressed.

Yet, developments such as the printing press

and the dissemination of algebra

would soon have important consequences. From around 1475 scientific inquiry resumed and later reached levels previously unseen. It was a period of great upheaval: the Fall of Constantinople

; the discovery of the Americas; the Protestant Reformation

and the Catholic Counter-Reformation

presaged large social and political changes. Indeed, the publication of Copernicus' heliocentric model of the cosmos (1543) is seen by many as marking the beginning of a scientific revolution

.

started in the 16th century, it was now in full operation. New ideas in physics, astronomy, biology, human anatomy, chemistry, and other sciences were posing a challenge for many conceptions about nature that had prevailed starting in Ancient Greece

and continuing through the Middle Ages

. This eventually led to the rejection of the old views and established a new framework for the study of nature. The period culminated with the publication of the Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica in 1687 by Isaac Newton

, representative of the unprecedented growth of scientific publications

throughout Europe. Newton is presented in the next section of the list, since he died in 1720.

. It was not a single movement or school of thought, it was less a set of ideas than it was a set of values. At its core was a critical questioning of traditional institution

s, custom

s, and moral

s, and a strong belief in rationality

and science. The end of the century saw the French Revolution

which led to the first major de-Christianization attempts in Europe to occur in many centuries. This culminated in the Cult of the Supreme Being

. The period thus saw Christianity in transition and eventually conflict.

of the scientific enterprise. By then, religious thinkers who expressed themselves on scientific subjects were increasingly treated as "trespassers". This was also the first century that saw actual discussions of the "relationship between science and religion". In previous ages there was occasional concern about tension between faith and reason, but religion and science were not presented as two opposing forces. This ethos gave birth to the conflict thesis

. At the end of the century it was common the view that science and religion "had been in a state of constant conflict". This notion is still very popular, although it is not endorsed by current research on the history of science

.

Relationship between religion and science

The relationship between religion and science has been a focus of the demarcation problem. Somewhat related is the claim that science and religion may pursue knowledge using different methodologies. Whereas the scientific method basically relies on reason and empiricism, religion also seeks to...

, but is specific to Christian history. This is only supplementary to the issue as lists are by themselves not equipped to answer questions on this topic. The purpose is to act as a guide: the names, annotations, and links are provided for use in further study on this topic.

The list is non-exhaustive and limited to scientist

Scientist

A scientist in a broad sense is one engaging in a systematic activity to acquire knowledge. In a more restricted sense, a scientist is an individual who uses the scientific method. The person may be an expert in one or more areas of science. This article focuses on the more restricted use of the word...

s who also contributed to Christian theology

Theology

Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo...

or religious thinking. There are two specific groups of Christians in science not covered in this list. Activities of Catholic scientists who are members of the Society of Jesus

Society of Jesus

The Society of Jesus is a Catholic male religious order that follows the teachings of the Catholic Church. The members are called Jesuits, and are also known colloquially as "God's Army" and as "The Company," these being references to founder Ignatius of Loyola's military background and a...

are presented in the List of Jesuit scientists. Scientists who are members of the Religious Society of Friends

Religious Society of Friends

The Religious Society of Friends, or Friends Church, is a Christian movement which stresses the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers. Members are known as Friends, or popularly as Quakers. It is made of independent organisations, which have split from one another due to doctrinal differences...

are presented in Quakers in science

Quakers in science

The Religious Society of Friends encouraged some values which may have been conducive to encouraging scientific talents. A theory suggested by David Hackett Fischer in his book Albion's Seed indicated early Quakers in the US preferred "practical study" to the more traditional studies of Greek or...

. This is due space constraints, otherwise the list would become even larger. Both groups made significant contributions to science.

Color code

A sense of denomination of each scientist is listed by color, but uncertainty can be acknowledged, hence the "other or unspecified" option.| Key: | Roman or Eastern-rite Catholic Roman Catholic Church The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity... |

Eastern Christianity (either Eastern Orthodox or Oriental Orthodox Oriental Orthodoxy Oriental Orthodoxy is the faith of those Eastern Christian Churches that recognize only three ecumenical councils — the First Council of Nicaea, the First Council of Constantinople and the First Council of Ephesus. They rejected the dogmatic definitions of the Council of Chalcedon... ) |

Anglicanism Anglicanism Anglicanism is a tradition within Christianity comprising churches with historical connections to the Church of England or similar beliefs, worship and church structures. The word Anglican originates in ecclesia anglicana, a medieval Latin phrase dating to at least 1246 that means the English... |

Protestantism | Other or Unspecified |

|---|

313–1000 (4th–10th centuries)

In 313 the Edict of MilanEdict of Milan

The Edict of Milan was a letter signed by emperors Constantine I and Licinius that proclaimed religious toleration in the Roman Empire...

ended Christian persecution in the Roman Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

. Although this is not the start of Christianity it may well be the start of Christians' recorded achievements in many pursuits, including science.

This period was marked by the process which brought the end of the Roman Empire

Decline of the Roman Empire

The decline of the Roman Empire refers to the gradual societal collapse of the Western Roman Empire. Many theories of causality prevail, but most concern the disintegration of political, economic, military, and other social institutions, in tandem with foreign invasions and usurpers from within the...

. Within the Greek East

Greek East

"Greek East" and "Latin West" are terms used to distinguish between the two parts of the Greco-Roman world, specifically the eastern regions where Greek was the lingua franca, and the western parts where Latin filled this role...

half, the ancient schools and institutions

Ancient higher-learning institutions

Ancient higher-learning institutions which give learning an institutional framework date back to ancient times and can be found in many cultures. These ancient centres were typically institutions of philosophical education and religious instruction...

that had been host to natural philosophy dwindled away or were closed. Meanwhile, the Latin West was left with even greater difficulties that affected the continent's intellectual production dramatically. Apart from depopulation and other factors, most scientific treatises of Classical Antiquity

History of science in Classical Antiquity

The history of science in classical antiquity encompasses both those inquiries into the workings of the universe aimed at such practical goals as establishing a reliable calendar or determining how to cure a variety of illnesses and those abstract investigations known as natural philosophy...

, written in Greek

Greek language

Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages. Native to the southern Balkans, it has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning 34 centuries of written records. Its writing system has been the Greek alphabet for the majority of its history;...

, had became unavailable, leaving only simplified summaries and compilations.

| Name | Image | Reason for inclusion |

|---|---|---|

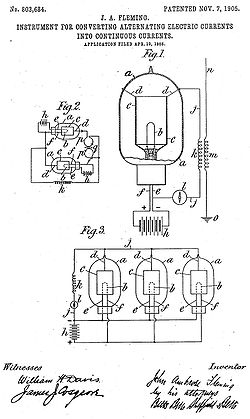

| John Philoponus John Philoponus John Philoponus , also known as John the Grammarian or John of Alexandria, was a Christian and Aristotelian commentator and the author of a considerable number of philosophical treatises and theological works... (c.490–c.570) |

|

He was a figure in the Monophysitism Monophysitism Monophysitism , or Monophysiticism, is the Christological position that Jesus Christ has only one nature, his humanity being absorbed by his Deity... minority of Eastern Christianity. His criticism of Aristotelian physics Aristotelian physics Aristotelian Physics the natural sciences, are described in the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle . In the Physics, Aristotle established general principles of change that govern all natural bodies; both living and inanimate, celestial and terrestrial—including all motion, change in respect... was important to Medieval science. He also theorized about the nature of light and the stars. As a theologian he rejected the Council of Chalcedon Council of Chalcedon The Council of Chalcedon was a church council held from 8 October to 1 November, 451 AD, at Chalcedon , on the Asian side of the Bosporus. The council marked a significant turning point in the Christological debates that led to the separation of the church of the Eastern Roman Empire in the 5th... and his major Christological work is Arbiter.He was also called John of Alexandria, hence the picture. |

| Bede, the Venerable Bede Bede , also referred to as Saint Bede or the Venerable Bede , was a monk at the Northumbrian monastery of Saint Peter at Monkwearmouth, today part of Sunderland, England, and of its companion monastery, Saint Paul's, in modern Jarrow , both in the Kingdom of Northumbria... (c.672–735) |

|

Catholic monk Monk A monk is a person who practices religious asceticism, living either alone or with any number of monks, while always maintaining some degree of physical separation from those not sharing the same purpose... , venerated as a saint Saint A saint is a holy person. In various religions, saints are people who are believed to have exceptional holiness.In Christian usage, "saint" refers to any believer who is "in Christ", and in whom Christ dwells, whether in heaven or in earth... and Doctor of the Church Doctor of the Church Doctor of the Church is a title given by a variety of Christian churches to individuals whom they recognize as having been of particular importance, particularly regarding their contribution to theology or doctrine.-Catholic Church:In the Catholic Church, this name is given to a saint from whose... . He was an influence for early medieval knowledge of nature. He wrote two works on "Time and its Reckoning." This primarily concerned how to date Easter, but contained a new recognition of the "progress wave-like" nature of tides. |

| Rabanus Maurus Rabanus Maurus Rabanus Maurus Magnentius , also known as Hrabanus or Rhabanus, was a Frankish Benedictine monk, the archbishop of Mainz in Germany and a theologian. He was the author of the encyclopaedia De rerum naturis . He also wrote treatises on education and grammar and commentaries on the Bible... (c.780–856) |

|

Benedictine Benedictine Benedictine refers to the spirituality and consecrated life in accordance with the Rule of St Benedict, written by Benedict of Nursia in the sixth century for the cenobitic communities he founded in central Italy. The most notable of these is Monte Cassino, the first monastery founded by Benedict... monk and teacher, he later became archbishop of Mainz and is venerated as blessed in the Catholic Church. He wrote a treatise on Computus Computus Computus is the calculation of the date of Easter in the Christian calendar. The name has been used for this procedure since the early Middle Ages, as it was one of the most important computations of the age.... and the encyclopedic work De universo. His teaching earned him the accolade of Praeceptor Germaniae, or "the teacher of Germany." |

| Leo the Mathematician Leo the Mathematician Leo the Mathematician or the Philosopher was a Byzantine philosopher and logician associated with the Macedonian Renaissance and the end of Iconoclasm. His only preserved writings are some notes contained in manuscripts of Plato's dialogues. He has been called a "true Renaissance man" and "the... (c.790–a.869) |

_by_florentine_cartographer_cristoforo_buondelmonte.jpg) |

Archbishop Archbishop An archbishop is a bishop of higher rank, but not of higher sacramental order above that of the three orders of deacon, priest , and bishop... of Thessalonica, he later became the head of the Magnaura School Magnaura The Magnaura was a large building in Constantinople. It is equated by scholars with the building that housed the Senate, and which was located east of the Augustaion, close to the Hagia Sophia and next to the Chalke gate of the Great Palace... of philosophy in Constantinople Constantinople Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:... , where he taught Aristotelian logic Organon The Organon is the name given by Aristotle's followers, the Peripatetics, to the standard collection of his six works on logic:* Categories* On Interpretation* Prior Analytics* Posterior Analytics... . Leo also composed his own medical encyclopaedia. He has been called a "true Renaissance man" and "the cleverest man in Byzantium in the 9th century". |

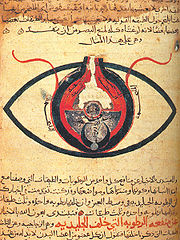

| Hunayn ibn Ishaq Hunayn ibn Ishaq Hunayn ibn Ishaq was a famous and influential Assyrian Nestorian Christian scholar, physician, and scientist, known for his work in translating Greek scientific and medical works into Arabic and Syriac during the heyday of the Islamic Abbasid Caliphate.Ḥunayn ibn Isḥaq was the most productive... (c.809–873) |

|

Assyrian Christian physician Physician A physician is a health care provider who practices the profession of medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring human health through the study, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, injury and other physical and mental impairments... known for translations of Greek scientific works and as author of "Ten Treatises on Ophthalmology." The image shows a picture inspired by his anatomical descriptions of the eye. He also wrote "How to Grasp Religion", which involved the apologetics for his faith. |

1001–1200 (11th and 12th centuries)

Even by the year 1000, western EuropeWestern Europe

Western Europe is a loose term for the collection of countries in the western most region of the European continents, though this definition is context-dependent and carries cultural and political connotations. One definition describes Western Europe as a geographic entity—the region lying in the...

remained a backwater compared to other world regions: while the population in Constantinople exceeded 300,000, Rome had mere 35,000 inhabitants and Paris only 20,000. This new period, however, saw prosperity and rapidly increasing population

Medieval demography

This article discusses human demography in Europe during the Middle Ages, including population trends and movements. Demographic changes helped to shape and define the Middle Ages...

, which brought about great social and political change.

During the Renaissance of the 12th century

Renaissance of the 12th century

The Renaissance of the 12th century was a period of many changes at the outset of the High Middle Ages. It included social, political and economic transformations, and an intellectual revitalization of Western Europe with strong philosophical and scientific roots...

, interest in the study of nature was revitalized through an intense translation movement aimed at Greek and Arabic scientific texts. Monastic

Monastic school

Monastic schools were, along with cathedral schools, the most important institutions of higher learning in the Latin West from the early Middle Ages until the 12th century. Since Cassiodorus's educational program, the standard curriculum incorporated religious studies, the Trivium, and the...

and cathedral school

Cathedral school

Cathedral schools began in the Early Middle Ages as centers of advanced education, some of them ultimately evolving into medieval universities. Throughout the Middle Ages and beyond, they were complemented by the monastic schools...

s took a leading role in studying these texts and theorizing over the new insights they brought. At the same time, an important new kind of higher learning institution was being developed: the university

Medieval university

Medieval university is an institution of higher learning which was established during High Middle Ages period and is a corporation.The first institutions generally considered to be universities were established in Italy, France, and England in the late 11th and the 12th centuries for the study of...

.

| Name | Image | Reason for inclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Pope Sylvester II (c.950–1003) | Benedictine monk, scientist, teacher, and later Pope Pope The Pope is the Bishop of Rome, a position that makes him the leader of the worldwide Catholic Church . In the Catholic Church, the Pope is regarded as the successor of Saint Peter, the Apostle... ; he promoted such knowledge as mathematics Mathematics Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity... and astronomy Astronomy Astronomy is a natural science that deals with the study of celestial objects and phenomena that originate outside the atmosphere of Earth... in Europe. As professor of the cathedral school at Rheims, he raised it to the height of prosperity. He also reintroduced the abacus Abacus The abacus, also called a counting frame, is a calculating tool used primarily in parts of Asia for performing arithmetic processes. Today, abaci are often constructed as a bamboo frame with beads sliding on wires, but originally they were beans or stones moved in grooves in sand or on tablets of... and armillary sphere Armillary sphere An armillary sphere is a model of objects in the sky , consisting of a spherical framework of rings, centred on Earth, that represent lines of celestial longitude and latitude and other astronomically important features such as the ecliptic... to Europe, which had been lost to the continent since the end of the Greco-Roman era. |

|

| Hermann of Reichenau Hermann of Reichenau Hermann of Reichenau , also called Hermannus Contractus or Hermannus Augiensis or Herman the Cripple, was an 11th century scholar, composer, music theorist, mathematician, and astronomer. He composed the Marian prayer Alma Redemptoris Mater... (1013–1054) |

Crippled by a paralytic disease from early childhood, he was a Benedictine monk who composed famous Marian antiphons and was beatified. As a scientist, he wrote on topics such as geometry Geometry Geometry arose as the field of knowledge dealing with spatial relationships. Geometry was one of the two fields of pre-modern mathematics, the other being the study of numbers .... , mathematics, and the astrolabe Astrolabe An astrolabe is an elaborate inclinometer, historically used by astronomers, navigators, and astrologers. Its many uses include locating and predicting the positions of the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars, determining local time given local latitude and longitude, surveying, triangulation, and to... (pictured). |

|

| Hugh of Saint Victor(c.1096–1141) | Influential mystic and philosopher who embraced science as a tool for approaching God. He was master of the monastic school of Saint Victor. His work presents knowledge of reality as redemptive Redemption (theology) Redemption is a concept common to several theologies. It is generally associated with the efforts of people within a faith to overcome their shortcomings and achieve the moral positions exemplified in their faith.- In Buddhism :... of fallen man Original sin Original sin is, according to a Christian theological doctrine, humanity's state of sin resulting from the Fall of Man. This condition has been characterized in many ways, ranging from something as insignificant as a slight deficiency, or a tendency toward sin yet without collective guilt, referred... ; and technology Technology Technology is the making, usage, and knowledge of tools, machines, techniques, crafts, systems or methods of organization in order to solve a problem or perform a specific function. It can also refer to the collection of such tools, machinery, and procedures. The word technology comes ;... as source of physical relief and able to help reunite man with divine wisdom. "Learn everything," he urged; "later you will see that nothing is superfluous." |

|

| William of Conches William of Conches William of Conches was a French scholastic philosopher who sought to expand the bounds of Christian humanism by studying secular works of the classics and fostering empirical science. He was a prominent member of the School of Chartres... (c.1090–a.1154) |

Scholastic Scholasticism Scholasticism is a method of critical thought which dominated teaching by the academics of medieval universities in Europe from about 1100–1500, and a program of employing that method in articulating and defending orthodoxy in an increasingly pluralistic context... philosopher who sought to expand Christian humanism Christian humanism Christian humanism is the position that universal human dignity and individual freedom are essential and principal components of, or are at least compatible with, Christian doctrine and practice. It is a philosophical union of Christian and humanist principles.- Origins :Christian humanism may have... by studying secular works of the classics and fostering empirical science. He held an atomistic Atomism Atomism is a natural philosophy that developed in several ancient traditions. The atomists theorized that the natural world consists of two fundamental parts: indivisible atoms and empty void.According to Aristotle, atoms are indestructible and immutable and there are an infinite variety of shapes... explanation of nature, and his hexameron Hexameron The term Hexameron refers either to the genre of theological treatise that describes God's work on the six days of creation or to the six days of creation themselves. Most often these theological works take the form of commentaries on Genesis 1... is a notable example of the naturalism Naturalism (philosophy) Naturalism commonly refers to the philosophical viewpoint that the natural universe and its natural laws and forces operate in the universe, and that nothing exists beyond the natural universe or, if it does, it does not affect the natural universe that we know... that came to characterize later medieval accounts of the six days of creation. He was a leading member of the cathedral school at Chartres School of Chartres During the High Middle Ages, Chartres Cathedral operated a famous and influential cathedral school, an important center of scholarship. It developed and reached its apex in the 11th and 12th centuries... . |

|

| Hildegard of Bingen Hildegard of Bingen Blessed Hildegard of Bingen , also known as Saint Hildegard, and Sibyl of the Rhine, was a German writer, composer, philosopher, Christian mystic, Benedictine abbess, visionary, and polymath. Elected a magistra by her fellow nuns in 1136, she founded the monasteries of Rupertsberg in 1150 and... (1098–1179) |

Benedictine abbess Abbess An abbess is the female superior, or mother superior, of a community of nuns, often an abbey.... , writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary Visionary Defined broadly, a visionary, is one who can envision the future. For some groups this can involve the supernatural or drugs.The visionary state is achieved via meditation, drugs, lucid dreams, daydreams, or art. One example is Hildegard of Bingen, a 12th century artist/visionary and Catholic saint... , polymath Polymath A polymath is a person whose expertise spans a significant number of different subject areas. In less formal terms, a polymath may simply be someone who is very knowledgeable... and Germany's first female physician Physician A physician is a health care provider who practices the profession of medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring human health through the study, diagnosis, and treatment of disease, injury and other physical and mental impairments... . She conducted and published comprehensive studies of natural science and medicine. Hildegard was well known in her own century as "the female prophet" and is venerated as a Catholic saint. |

1201–1400 (13th and 14th centuries)

The translation of scientific texts continued. By 1200, there were reasonably accurate Latin versions of the main classical works. Meanwhile, the new universitiesMedieval university

Medieval university is an institution of higher learning which was established during High Middle Ages period and is a corporation.The first institutions generally considered to be universities were established in Italy, France, and England in the late 11th and the 12th centuries for the study of...

were rapidly spreading through Europe and providing a new infrastructure for scientific communities

Scientific community

The scientific community consists of the total body of scientists, its relationships and interactions. It is normally divided into "sub-communities" each working on a particular field within science. Objectivity is expected to be achieved by the scientific method...

. They became the main institutions in which the new texts were studied and elaborated. In fact, the medieval university curriculum

Curriculum

See also Syllabus.In formal education, a curriculum is the set of courses, and their content, offered at a school or university. As an idea, curriculum stems from the Latin word for race course, referring to the course of deeds and experiences through which children grow to become mature adults...

laid much more emphasis on scientific knowledge than does its modern descendent. This all lead to innovative scientific work being done, especially in the 14th century.

| Name | Image | Reason for inclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Robert Grosseteste Robert Grosseteste Robert Grosseteste or Grossetete was an English statesman, scholastic philosopher, theologian and Bishop of Lincoln. He was born of humble parents at Stradbroke in Suffolk. A.C... (c.1175–1253) |

Bishop of Lincoln Bishop of Lincoln The Bishop of Lincoln is the Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Lincoln in the Province of Canterbury.The present diocese covers the county of Lincolnshire and the unitary authority areas of North Lincolnshire and North East Lincolnshire. The Bishop's seat is located in the Cathedral... , he was the central character of the English intellectual movement in the first half of the 13th century and is considered the founder of scientific thought in Oxford Oxford The city of Oxford is the county town of Oxfordshire, England. The city, made prominent by its medieval university, has a population of just under 165,000, with 153,900 living within the district boundary. It lies about 50 miles north-west of London. The rivers Cherwell and Thames run through... . He had a great interest in the natural world and wrote texts on the mathematical sciences of optics Optics Optics is the branch of physics which involves the behavior and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behavior of visible, ultraviolet, and infrared light... , astronomy Astronomy Astronomy is a natural science that deals with the study of celestial objects and phenomena that originate outside the atmosphere of Earth... and geometry Geometry Geometry arose as the field of knowledge dealing with spatial relationships. Geometry was one of the two fields of pre-modern mathematics, the other being the study of numbers .... . He affirmed that experiments should be used in order to verify a theory, testing its consequences. |

|

| Pope John XXI Pope John XXI Pope John XXI, , born Pedro Julião Pope John XXI, , born Pedro Julião Pope John XXI, , born Pedro Julião (Latin, Petrus Iulianus (c. 1215 – May 20, 1277), a Portuguese also called Pedro Hispano (Latin, Petrus Hispanus; English, Peter of Spain), was Pope from 1276 until his death about eight... (c.1215–1277) |

He wrote the widely used medical text Thesaurus pauperum before becoming Pope. When he took office as pope in 1277, he immediately cracked down on heterodoxy including Averroes Averroes ' , better known just as Ibn Rushd , and in European literature as Averroes , was a Muslim polymath; a master of Aristotelian philosophy, Islamic philosophy, Islamic theology, Maliki law and jurisprudence, logic, psychology, politics, Arabic music theory, and the sciences of medicine, astronomy,... works and teachings on Aristotle. |

|

| Albertus Magnus Albertus Magnus Albertus Magnus, O.P. , also known as Albert the Great and Albert of Cologne, is a Catholic saint. He was a German Dominican friar and a bishop, who achieved fame for his comprehensive knowledge of and advocacy for the peaceful coexistence of science and religion. Those such as James A. Weisheipl... (c.1193–1280) |

Patron saint Patron saint A patron saint is a saint who is regarded as the intercessor and advocate in heaven of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, family, or person... of scientists in Catholicism who may have been the first to isolate arsenic Arsenic Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As, atomic number 33 and relative atomic mass 74.92. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in conjunction with sulfur and metals, and also as a pure elemental crystal. It was first documented by Albertus Magnus in 1250.Arsenic is a metalloid... . He wrote that: "Natural science does not consist in ratifying what others have said, but in seeking the causes of phenomena." Yet he rejected elements of Aristotelianism that conflicted with Catholicism and drew on his faith as well as Neo-Platonic ideas to "balance" "troubling" Aristotelian elements.In 1252 he helped appoint Thomas Aquinas to a Dominican theological chair in Paris to lead the suppression of these dangerous ideas. |

|

| Roger Bacon Roger Bacon Roger Bacon, O.F.M. , also known as Doctor Mirabilis , was an English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through empirical methods... (c.1214–1294) |

He was an English philosopher who emphasized empiricism Empiricism Empiricism is a theory of knowledge that asserts that knowledge comes only or primarily via sensory experience. One of several views of epistemology, the study of human knowledge, along with rationalism, idealism and historicism, empiricism emphasizes the role of experience and evidence,... and has been presented as one of the earliest advocates of the modern scientific method Scientific method Scientific method refers to a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge. To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry must be based on gathering empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of... . He joined the Franciscan Order around 1240, where he was influenced by Grosseteste. Bacon was responsible for making the concept of "laws of nature" widespread, and contributed in such areas as mechanics Mechanics Mechanics is the branch of physics concerned with the behavior of physical bodies when subjected to forces or displacements, and the subsequent effects of the bodies on their environment.... , geography Geography Geography is the science that studies the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. A literal translation would be "to describe or write about the Earth". The first person to use the word "geography" was Eratosthenes... and, most of all, optics. It is said that he was imprisoned by the church for many years because of his scientific teachings, although this is disputed. |

|

| Theodoric of Freiberg Theodoric of Freiberg Theodoric of Freiberg was a German member of the Dominican order and a theologian and physicist... (c.1250–c.1310) |

Dominican Dominican Order The Order of Preachers , after the 15th century more commonly known as the Dominican Order or Dominicans, is a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Dominic and approved by Pope Honorius III on 22 December 1216 in France... who is believed to have given the first correct explanation for the rainbow in De iride et radialibus impressionibus or On the Rainbow. In theology he disagreed with Thomas Aquinas Thomas Aquinas Thomas Aquinas, O.P. , also Thomas of Aquin or Aquino, was an Italian Dominican priest of the Catholic Church, and an immensely influential philosopher and theologian in the tradition of scholasticism, known as Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Communis, or Doctor Universalis... on metaphysical positions and tended towards a more Neoplatonic outlook than Aquinas. |

|

| Thomas Bradwardine Thomas Bradwardine Thomas Bradwardine was an English scholar, scientist, courtier and, very briefly, Archbishop of Canterbury. As a celebrated scholastic philosopher and doctor of theology, he is often called Doctor Profundus, .-Life:He was born either at Hartfield in Sussex or at Chichester, where his family were... (c.1290–1349) |

He was an English archbishop Archbishop An archbishop is a bishop of higher rank, but not of higher sacramental order above that of the three orders of deacon, priest , and bishop... , often called "the Profound Doctor". He developed studies as one of the Oxford Calculators Oxford Calculators The Oxford Calculators were a group of 14th-century thinkers, almost all associated with Merton College, Oxford, who took a strikingly logico-mathematical approach to philosophical problems.... of Merton College, Oxford University. These studies would lead to important developments in mechanics Mechanics Mechanics is the branch of physics concerned with the behavior of physical bodies when subjected to forces or displacements, and the subsequent effects of the bodies on their environment.... . |

|

| William of Ockham William of Ockham William of Ockham was an English Franciscan friar and scholastic philosopher, who is believed to have been born in Ockham, a small village in Surrey. He is considered to be one of the major figures of medieval thought and was at the centre of the major intellectual and political controversies of... (c.1285–c.1350) |

He was an English England England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental... Franciscan Franciscan Most Franciscans are members of Roman Catholic religious orders founded by Saint Francis of Assisi. Besides Roman Catholic communities, there are also Old Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, ecumenical and Non-denominational Franciscan communities.... friar Friar A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders.-Friars and monks:... and scholastic Scholasticism Scholasticism is a method of critical thought which dominated teaching by the academics of medieval universities in Europe from about 1100–1500, and a program of employing that method in articulating and defending orthodoxy in an increasingly pluralistic context... philosopher. He is a major figure of medieval thought and was at the center of the major intellectual and political controversies of his time. Commonly known for Occam's razor Occam's razor Occam's razor, also known as Ockham's razor, and sometimes expressed in Latin as lex parsimoniae , is a principle that generally recommends from among competing hypotheses selecting the one that makes the fewest new assumptions.-Overview:The principle is often summarized as "simpler explanations... , the scientific/methodological principle that bears his name, he also produced significant works on logic Logic In philosophy, Logic is the formal systematic study of the principles of valid inference and correct reasoning. Logic is used in most intellectual activities, but is studied primarily in the disciplines of philosophy, mathematics, semantics, and computer science... , physics Physics Physics is a natural science that involves the study of matter and its motion through spacetime, along with related concepts such as energy and force. More broadly, it is the general analysis of nature, conducted in order to understand how the universe behaves.Physics is one of the oldest academic... , and theology Theology Theology is the systematic and rational study of religion and its influences and of the nature of religious truths, or the learned profession acquired by completing specialized training in religious studies, usually at a university or school of divinity or seminary.-Definition:Augustine of Hippo... . |

|

| Jean Buridan Jean Buridan Jean Buridan was a French priest who sowed the seeds of the Copernican revolution in Europe. Although he was one of the most famous and influential philosophers of the late Middle Ages, he is today among the least well known... (c.1300–c.1358) |

He was a Catholic priest and one of the most influential philosophers of the later Middle Ages Middle Ages The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern... . He developed the theory of impetus Impetus Impetus may refer to:* Impetus , a re-release of the EP Passive Restraints* Impetus , a concept very similar to momentum* Jean Buridan#Impetus Theory, middle-ages treatment on impetus and its originator Jean Buridan... , which was an important step toward the modern concept of inertia Inertia Inertia is the resistance of any physical object to a change in its state of motion or rest, or the tendency of an object to resist any change in its motion. It is proportional to an object's mass. The principle of inertia is one of the fundamental principles of classical physics which are used to... . |

|

| Nicole Oresme (c.1323–1382) |  |

Theologian and bishop of Lisieux, he was one of the early founders and popularizers of modern sciences. One of his many scientific contributions is the discovery of the curvature of light through atmospheric refraction Refraction Refraction is the change in direction of a wave due to a change in its speed. It is essentially a surface phenomenon . The phenomenon is mainly in governance to the law of conservation of energy. The proper explanation would be that due to change of medium, the phase velocity of the wave is changed... . |

1401–1600 (15th and 16th centuries)

Around 1350, the Black DeathBlack Death

The Black Death was one of the most devastating pandemics in human history, peaking in Europe between 1348 and 1350. Of several competing theories, the dominant explanation for the Black Death is the plague theory, which attributes the outbreak to the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Thought to have...

and other disasters

Crisis of the Late Middle Ages

The Crisis of the Late Middle Ages refers to a series of events in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries that brought centuries of European prosperity and growth to a halt...

sealed a sudden end to the previous period of massive philosophic and scientific development. Even during the initial portion of the Renaissance

Renaissance

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that spanned roughly the 14th to the 17th century, beginning in Italy in the Late Middle Ages and later spreading to the rest of Europe. The term is also used more loosely to refer to the historical era, but since the changes of the Renaissance were not...

, the amount of scientific activity remained depressed.

Yet, developments such as the printing press

Printing press

A printing press is a device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium , thereby transferring the ink...

and the dissemination of algebra

Algebra

Algebra is the branch of mathematics concerning the study of the rules of operations and relations, and the constructions and concepts arising from them, including terms, polynomials, equations and algebraic structures...

would soon have important consequences. From around 1475 scientific inquiry resumed and later reached levels previously unseen. It was a period of great upheaval: the Fall of Constantinople

Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire, which occurred after a siege by the Ottoman Empire, under the command of Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II, against the defending army commanded by Byzantine Emperor Constantine XI...

; the discovery of the Americas; the Protestant Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

and the Catholic Counter-Reformation

Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation was the period of Catholic revival beginning with the Council of Trent and ending at the close of the Thirty Years' War, 1648 as a response to the Protestant Reformation.The Counter-Reformation was a comprehensive effort, composed of four major elements:#Ecclesiastical or...

presaged large social and political changes. Indeed, the publication of Copernicus' heliocentric model of the cosmos (1543) is seen by many as marking the beginning of a scientific revolution

Scientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution is an era associated primarily with the 16th and 17th centuries during which new ideas and knowledge in physics, astronomy, biology, medicine and chemistry transformed medieval and ancient views of nature and laid the foundations for modern science...

.

| Name | Image | Reason for inclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Nicholas of Cusa (1401–1464) |  |

Catholic cardinal Cardinal (Catholicism) A cardinal is a senior ecclesiastical official, usually an ordained bishop, and ecclesiastical prince of the Catholic Church. They are collectively known as the College of Cardinals, which as a body elects a new pope. The duties of the cardinals include attending the meetings of the College and... and theologian who made contributions to the field of mathematics by developing the concepts of the infinitesimal and of relative motion. His philosophical speculations also anticipated Copernicus Nicolaus Copernicus Nicolaus Copernicus was a Renaissance astronomer and the first person to formulate a comprehensive heliocentric cosmology which displaced the Earth from the center of the universe.... ’ heliocentric Heliocentrism Heliocentrism, or heliocentricism, is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around a stationary Sun at the center of the universe. The word comes from the Greek . Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at the center... world-view. |

| Otto Brunfels Otto Brunfels Otto Brunfels was a German theologian and botanist... (1488–1534) |

|

A theologian and botanist from Mainz Mainz Mainz under the Holy Roman Empire, and previously was a Roman fort city which commanded the west bank of the Rhine and formed part of the northernmost frontier of the Roman Empire... , Germany. His Catalogi virorum illustrium is considered to be the first book on the history of evangelical sects that had broken away from the Catholic Church. In botany his Herbarum vivae icones helped earn him acclaim as one of the "fathers of botany". |

| Nicolaus Copernicus Nicolaus Copernicus Nicolaus Copernicus was a Renaissance astronomer and the first person to formulate a comprehensive heliocentric cosmology which displaced the Earth from the center of the universe.... (1473–1543) |

|

Catholic canon Canon (priest) A canon is a priest or minister who is a member of certain bodies of the Christian clergy subject to an ecclesiastical rule .... who introduced a heliocentric world view. In 1616, in connection with the Galileo affair Galileo affair The Galileo affair was a sequence of events, beginning around 1610, during which Galileo Galilei came into conflict with the Aristotelian scientific view of the universe , over his support of Copernican astronomy.... , this work was forbidden by the Church "until corrected". Nine sentences representing heliocentricism as certain had to be either omitted or changed. This done, the reading of the book was allowed. Only in 1835 the original uncensored version was dropped from the Index of Prohibited Books Index Librorum Prohibitorum The Index Librorum Prohibitorum was a list of publications prohibited by the Catholic Church. A first version was promulgated by Pope Paul IV in 1559, and a revised and somewhat relaxed form was authorized at the Council of Trent... . |

| Michael Servetus Michael Servetus Michael Servetus was a Spanish theologian, physician, cartographer, and humanist. He was the first European to correctly describe the function of pulmonary circulation... (1511–1553) |

|

Nontrinitarian who was condemned and imprisoned by Catholics before being burned at the stake by Calvinists in Protestant-run Geneva. In science wrote on astronomy and his theological work "Christianismi Restitutio" contained the first European description of the function of pulmonary circulation Pulmonary circulation Pulmonary circulation is the half portion of the cardiovascular system which carries Oxygen-depleted Blood away from the heart, to the Lungs, and returns oxygenated blood back to the heart. Encyclopedic description and discovery of the pulmonary circulation is widely attributed to Doctor Ibn... . |

| Michael Stifel Michael Stifel Michael Stifel or Styfel was a German monk and mathematician. He was an Augustinian who became an early supporter of Martin Luther. Stifel was later appointed professor of mathematics at Jena University... (c.1486–1567) |

Augustinian monk and mathematician who became an early supporter of Martin Luther Martin Luther Martin Luther was a German priest, professor of theology and iconic figure of the Protestant Reformation. He strongly disputed the claim that freedom from God's punishment for sin could be purchased with money. He confronted indulgence salesman Johann Tetzel with his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517... . His Arithmetica integra (pictured) contained important innovations in mathematical notation and a table of integers and powers of 2 that some have considered to be an early version of a logarithm Logarithm The logarithm of a number is the exponent by which another fixed value, the base, has to be raised to produce that number. For example, the logarithm of 1000 to base 10 is 3, because 1000 is 10 to the power 3: More generally, if x = by, then y is the logarithm of x to base b, and is written... ic table. He also wrote on Biblical prophecies. |

|

| William Turner (c.1508–1568) | He is sometimes called the "father of English botany" and was also an ornithologist. Religiously he was arrested for preaching in favor of the Reformation. He later became a Dean of Wells Cathedral Wells Cathedral Wells Cathedral is a Church of England cathedral in Wells, Somerset, England. It is the seat of the Bishop of Bath and Wells, who lives at the adjacent Bishop's Palace.... , pictured, but was expelled for nonconformity. |

|

| Ignazio Danti Ignazio Danti Ignazio Danti , born Pellegrino Rainaldi Danti, was an Italian priest, mathematician, astronomer, and cosmographer.-Biography:Danti was born in Perugia to a family rich in artists and scientists... (1536–1586) |

As bishop of Alatri he convoked a diocesan synod to deal with abuses. He was also a mathematician who wrote on Euclid Euclid Euclid , fl. 300 BC, also known as Euclid of Alexandria, was a Greek mathematician, often referred to as the "Father of Geometry". He was active in Alexandria during the reign of Ptolemy I... , an astronomer, and a designer of mechanical devices. |

|

| Giordano Bruno Giordano Bruno Giordano Bruno , born Filippo Bruno, was an Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, mathematician and astronomer. His cosmological theories went beyond the Copernican model in proposing that the Sun was essentially a star, and moreover, that the universe contained an infinite number of inhabited... (1548–1600) |

|

Italian philosopher, priest, cosmologist, and occultist, known for espousing the idea the that Earth revolves around the Sun and that many other worlds revolve around other suns. For his many heretical views, including his denial of the divinity of Christ, he was tried by the Roman Inquisition and burned at the stake. The Catholic Encyclopedia labels his system of beliefs "an incoherent materialistic pantheism." |

1601–1700 (17th century)

If the scientific revolutionScientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution is an era associated primarily with the 16th and 17th centuries during which new ideas and knowledge in physics, astronomy, biology, medicine and chemistry transformed medieval and ancient views of nature and laid the foundations for modern science...

started in the 16th century, it was now in full operation. New ideas in physics, astronomy, biology, human anatomy, chemistry, and other sciences were posing a challenge for many conceptions about nature that had prevailed starting in Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece is a civilization belonging to a period of Greek history that lasted from the Archaic period of the 8th to 6th centuries BC to the end of antiquity. Immediately following this period was the beginning of the Early Middle Ages and the Byzantine era. Included in Ancient Greece is the...

and continuing through the Middle Ages

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages is a periodization of European history from the 5th century to the 15th century. The Middle Ages follows the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 and precedes the Early Modern Era. It is the middle period of a three-period division of Western history: Classic, Medieval and Modern...

. This eventually led to the rejection of the old views and established a new framework for the study of nature. The period culminated with the publication of the Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica in 1687 by Isaac Newton

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."...

, representative of the unprecedented growth of scientific publications

Antiquarian science book

Antiquarian science books are original works that are at least roughly 100 years old, concerning science, mathematics and sometimes engineering...

throughout Europe. Newton is presented in the next section of the list, since he died in 1720.

| Name | Image | Reason for inclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Bartholomaeus Pitiscus Bartholomaeus Pitiscus Bartholomaeus Pitiscus was a 16th century German trigonometrist, astronomer and theologian who first coined the word Trigonometry.... (1561–1613) |

|

He may have introduced the word trigonometry into English and French. He was also a Calvinist theologian who acted as court preacher at the town then called Breslau, hence the image of their town square. |

| John Napier John Napier John Napier of Merchiston – also signed as Neper, Nepair – named Marvellous Merchiston, was a Scottish mathematician, physicist, astronomer & astrologer, and also the 8th Laird of Merchistoun. He was the son of Sir Archibald Napier of Merchiston. John Napier is most renowned as the discoverer... (1550–1617) |

|

Scottish mathematician known for inventing logarithm Logarithm The logarithm of a number is the exponent by which another fixed value, the base, has to be raised to produce that number. For example, the logarithm of 1000 to base 10 is 3, because 1000 is 10 to the power 3: More generally, if x = by, then y is the logarithm of x to base b, and is written... s, Napier's bones Napier's bones Napier's bones is an abacus created by John Napier for calculation of products and quotients of numbers that was based on Arab mathematics and lattice multiplication used by Matrakci Nasuh in the Umdet-ul Hisab and Fibonacci writing in the Liber Abaci. Also called Rabdology... , and being the popularizer of the use of decimals. He also was a staunch Protestant who wrote on the Book of Revelation Book of Revelation The Book of Revelation is the final book of the New Testament. The title came into usage from the first word of the book in Koine Greek: apokalupsis, meaning "unveiling" or "revelation"... . |

| Johannes Kepler Johannes Kepler Johannes Kepler was a German mathematician, astronomer and astrologer. A key figure in the 17th century scientific revolution, he is best known for his eponymous laws of planetary motion, codified by later astronomers, based on his works Astronomia nova, Harmonices Mundi, and Epitome of Copernican... (1571–1630) |

|

His model of the cosmos based on nesting Platonic solids was explicitly driven by religious ideas; his later and most famous scientific contribution, the Kepler's laws of planetary motion Kepler's laws of planetary motion In astronomy, Kepler's laws give a description of the motion of planets around the Sun.Kepler's laws are:#The orbit of every planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the two foci.... , was based on empirical data that he obtained from Tycho Brahe Tycho Brahe Tycho Brahe , born Tyge Ottesen Brahe, was a Danish nobleman known for his accurate and comprehensive astronomical and planetary observations... 's meticulous astronomical observations, after Tycho died of mercury poisoning. He had wanted to be a theologian at one time and his Harmonice Mundi Harmonice Mundi Harmonices Mundi is a book by Johannes Kepler. In the work Kepler discusses harmony and congruence in geometrical forms and physical phenomena... discusses Christ at points. |

| Galileo Galilei Galileo Galilei Galileo Galilei , was an Italian physicist, mathematician, astronomer, and philosopher who played a major role in the Scientific Revolution. His achievements include improvements to the telescope and consequent astronomical observations and support for Copernicanism... (1564–1642) |

|

Scientist who had many problems with the Inquisition Inquisition The Inquisition, Inquisitio Haereticae Pravitatis , was the "fight against heretics" by several institutions within the justice-system of the Roman Catholic Church. It started in the 12th century, with the introduction of torture in the persecution of heresy... for defending heliocentrism Heliocentrism Heliocentrism, or heliocentricism, is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around a stationary Sun at the center of the universe. The word comes from the Greek . Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at the center... in the convoluted period brought about by the Reformation Protestant Reformation The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led... and Counter-Reformation Counter-Reformation The Counter-Reformation was the period of Catholic revival beginning with the Council of Trent and ending at the close of the Thirty Years' War, 1648 as a response to the Protestant Reformation.The Counter-Reformation was a comprehensive effort, composed of four major elements:#Ecclesiastical or... . In regard to Scripture, he took Augustine's Augustine of Hippo Augustine of Hippo , also known as Augustine, St. Augustine, St. Austin, St. Augoustinos, Blessed Augustine, or St. Augustine the Blessed, was Bishop of Hippo Regius . He was a Latin-speaking philosopher and theologian who lived in the Roman Africa Province... position: not to take every passage too literally, particularly when the scripture in question is a book of poetry and songs, not a book of instructions or history. |

| Laurentius Gothus Laurentius Paulinus Gothus Laurentius Paulinus Gothus was a Swedish theologian, astronomer and Archbishop of Uppsala .-Life:In 1588 Gothus travelled to Germany and studied in the Rostock University for three years... (1565–1646) |

|

A professor of astronomy and Archbishop of Uppsala Archbishop of Uppsala The Archbishop of Uppsala has been the primate in Sweden in an unbroken succession since 1164, first during the Catholic era, and from the 1530s and onward under the Lutheran church.- Historical overview :... . He wrote on astronomy and theology. |

| Marin Mersenne Marin Mersenne Marin Mersenne, Marin Mersennus or le Père Mersenne was a French theologian, philosopher, mathematician and music theorist, often referred to as the "father of acoustics"... (1588–1648) |

For four years he devoted himself to theology writing Quaestiones celeberrimae in Genesim (1623) and L'Impieté des déistes (1624). These were theological essays against atheism and deism. He is more remembered for the work he did corresponding with mathematicians and concerning Mersenne prime Mersenne prime In mathematics, a Mersenne number, named after Marin Mersenne , is a positive integer that is one less than a power of two: M_p=2^p-1.\,... s. |

|

| René Descartes René Descartes René Descartes ; was a French philosopher and writer who spent most of his adult life in the Dutch Republic. He has been dubbed the 'Father of Modern Philosophy', and much subsequent Western philosophy is a response to his writings, which are studied closely to this day... (1596–1650) |

|

He was a key thinker of the Scientific Revolution. He is also honoured by having the Cartesian coordinate system used in plane geometry and algebra named after him. He did important work on invariants and geometry Geometry Geometry arose as the field of knowledge dealing with spatial relationships. Geometry was one of the two fields of pre-modern mathematics, the other being the study of numbers .... . His Meditations on First Philosophy partially concerns theology and he was devoted to reconciling his ideas with the dogmas of Catholic Faith to which he was loyal.This attempt was, and is, considered unsuccessful by the Catholic Church so his philosophy is still considered erroneous in it. |

| Pierre Gassendi Pierre Gassendi Pierre Gassendi was a French philosopher, priest, scientist, astronomer, and mathematician. With a church position in south-east France, he also spent much time in Paris, where he was a leader of a group of free-thinking intellectuals. He was also an active observational scientist, publishing the... (1592–1655) |

Catholic priest who tried to reconcile Atomism Atomism Atomism is a natural philosophy that developed in several ancient traditions. The atomists theorized that the natural world consists of two fundamental parts: indivisible atoms and empty void.According to Aristotle, atoms are indestructible and immutable and there are an infinite variety of shapes... with Christianity. He also published the first work on the Transit of Mercury Transit of Mercury A transit of Mercury across the Sun takes place when the planet Mercury comes between the Sun and the Earth, and Mercury is seen as a small black dot moving across the face of the Sun.... and corrected the geographical coordinates of the Mediterranean Sea. |

|

| Anton Maria of Rheita Anton Maria Schyrleus of Rheita Anton Maria Schyrleus of Rheita was an astronomer and optician. He developed several inverting and erecting eyepieces, and was the maker of Kepler’s telescope... (1597–1660) |

Capuchin Order of Friars Minor Capuchin The Order of Friars Minor Capuchin is an Order of friars in the Catholic Church, among the chief offshoots of the Franciscans. The worldwide head of the Order, called the Minister General, is currently Father Mauro Jöhri.-Origins :... astronomer. He dedicated one of his astronomy books to Jesus Christ, a "theo-astronomy" work was dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, and he wondered if beings on other planets were "cursed by original sin Original sin Original sin is, according to a Christian theological doctrine, humanity's state of sin resulting from the Fall of Man. This condition has been characterized in many ways, ranging from something as insignificant as a slight deficiency, or a tendency toward sin yet without collective guilt, referred... like humans are." |

|

| Blaise Pascal Blaise Pascal Blaise Pascal , was a French mathematician, physicist, inventor, writer and Catholic philosopher. He was a child prodigy who was educated by his father, a tax collector in Rouen... (1623–1662) |

|

Jansenist Jansenism Jansenism was a Christian theological movement, primarily in France, that emphasized original sin, human depravity, the necessity of divine grace, and predestination. The movement originated from the posthumously published work of the Dutch theologian Cornelius Otto Jansen, who died in 1638... thinker;Although Jansenism was a movement within Roman Catholicism, it was generally opposed by the Catholic hierarchy and was eventually condemned as heretical. well known for Pascal's law Pascal's law In the physical sciences, Pascal's law or the Principle of transmission of fluid-pressure states that "pressure exerted anywhere in a confined incompressible fluid is transmitted equally in all directions throughout the fluid such that the pressure ratio remains the same." The law was established... (physics), Pascal's theorem Pascal's theorem In projective geometry, Pascal's theorem states that if an arbitrary hexagon is inscribed in any conic section, and pairs of opposite sides are extended until they meet, the three intersection points will lie on a straight line, the Pascal line of that configuration.- Related results :This theorem... (math), and Pascal's Wager Pascal's Wager Pascal's Wager, also known as Pascal's Gambit, is a suggestion posed by the French philosopher, mathematician, and physicist Blaise Pascal that even if the existence of God could not be determined through reason, a rational person should wager as though God exists, because one living life... (theology). |

| Isaac Barrow Isaac Barrow Isaac Barrow was an English Christian theologian, and mathematician who is generally given credit for his early role in the development of infinitesimal calculus; in particular, for the discovery of the fundamental theorem of calculus. His work centered on the properties of the tangent; Barrow was... (1630–1677) |

|

English divine, scientist, and mathematician. He wrote Expositions of the Creed, The Lord's Prayer, Decalogue, and Sacraments and Lectiones Opticae et Geometricae. |

| Juan Lobkowitz Juan Caramuel y Lobkowitz Juan Caramuel y Lobkowitz was a Spanish Catholic scholastic philosopher, ecclesiastic, mathematician and writer.-Life:... (1606–1682) |

Cistercian monk who did work on Combinatorics Combinatorics Combinatorics is a branch of mathematics concerning the study of finite or countable discrete structures. Aspects of combinatorics include counting the structures of a given kind and size , deciding when certain criteria can be met, and constructing and analyzing objects meeting the criteria ,... and published astronomy tables at age 10. He also did works of theology and sermons. |

|

| Nicolas Steno Nicolas Steno Nicolas Steno |Latinized]] to Nicolaus Steno -gen. Nicolai Stenonis-, Italian Niccolo' Stenone) was a Danish pioneer in both anatomy and geology. Already in 1659 he decided not to accept anything simply written in a book, instead resolving to do research himself. He is considered the father of... (1638–1686) |

|

Lutheran convert to Catholicism, his beatification Beatification Beatification is a recognition accorded by the Catholic Church of a dead person's entrance into Heaven and capacity to intercede on behalf of individuals who pray in his or her name . Beatification is the third of the four steps in the canonization process... in that faith occurred in 1987. As a scientist he is considered a pioneer in both anatomy and geology, but largely abandoned science after his religious conversion. |

| Seth Ward Seth Ward (bishop) Seth Ward was an English mathematician, astronomer, and bishop.-Early life:He was born in Hertfordshire, and educated at Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, where he graduated B.A. in 1636 and M.A. in 1640, becoming a Fellow in that year... (1617–1689) |

.jpg) |

Anglican Bishop of Salisbury Bishop of Salisbury The Bishop of Salisbury is the ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of Salisbury in the Province of Canterbury.The diocese covers much of the counties of Wiltshire and Dorset... and Savilian Chair of Astronomy Savilian Chair of Astronomy The Savilian Chair of Astronomy at the University of Oxford in England was founded in 1619 and is named after Sir Henry Savile. The Professor is a Fellow of New College.... from 1649–1661. He wrote Ismaelis Bullialdi astro-nomiae philolaicae fundamenta inquisitio brevis and Astronomia geometrica. He also had a theological/philosophical dispute with Thomas Hobbes Thomas Hobbes Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury , in some older texts Thomas Hobbs of Malmsbury, was an English philosopher, best known today for his work on political philosophy... and as a bishop was severe toward nonconformists Nonconformism Nonconformity is the refusal to "conform" to, or follow, the governance and usages of the Church of England by the Protestant Christians of England and Wales.- Origins and use:... . |

| Robert Boyle Robert Boyle Robert Boyle FRS was a 17th century natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, and inventor, also noted for his writings in theology. He has been variously described as English, Irish, or Anglo-Irish, his father having come to Ireland from England during the time of the English plantations of... (1627–1691) |

|

Scientist and theologian who argued that the study of science could improve glorification of God. |

1701–1800 (18th century)

The 18th century is considered the zenith of the EnlightenmentAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment was an elite cultural movement of intellectuals in 18th century Europe that sought to mobilize the power of reason in order to reform society and advance knowledge. It promoted intellectual interchange and opposed intolerance and abuses in church and state...

. It was not a single movement or school of thought, it was less a set of ideas than it was a set of values. At its core was a critical questioning of traditional institution

Institution

An institution is any structure or mechanism of social order and cooperation governing the behavior of a set of individuals within a given human community...

s, custom

Custom

Custom may refer to:* Convention , a set of agreed, stipulated or generally accepted rules, norms, standards or criteria, often taking the form of a custom* Customization , anything made or modified to personal taste...

s, and moral

Moral

A moral is a message conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim...

s, and a strong belief in rationality

Rationality

In philosophy, rationality is the exercise of reason. It is the manner in which people derive conclusions when considering things deliberately. It also refers to the conformity of one's beliefs with one's reasons for belief, or with one's actions with one's reasons for action...

and science. The end of the century saw the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

which led to the first major de-Christianization attempts in Europe to occur in many centuries. This culminated in the Cult of the Supreme Being

Cult of the Supreme Being

The Cult of the Supreme Being was a form of deism established in France by Maximilien Robespierre during the French Revolution. It was intended to become the state religion of the new French Republic.- Origins :...

. The period thus saw Christianity in transition and eventually conflict.

| Name | Image | Reason for inclusion |

|---|---|---|

| John Wallis (1616–1703) |  |

As a mathematician he wrote Arithmetica Infinitorumis, introduced the term Continued fraction Continued fraction In mathematics, a continued fraction is an expression obtained through an iterative process of representing a number as the sum of its integer part and the reciprocal of another number, then writing this other number as the sum of its integer part and another reciprocal, and so on... , worked on cryptography, helped develop calculus, and is further known for the Wallis product. He also devised a system for teaching the non-speaking deaf Deaf culture Deaf culture describes the social beliefs, behaviors, art, literary traditions, history, values and shared institutions of communities that are affected by deafness and which use sign languages as the main means of communication. When used as a cultural label, the word deaf is often written with a... . He was also a Calvinist inclined chaplain who was active in theological debate. |

| John Ray John Ray John Ray was an English naturalist, sometimes referred to as the father of English natural history. Until 1670, he wrote his name as John Wray. From then on, he used 'Ray', after "having ascertained that such had been the practice of his family before him".He published important works on botany,... (1627–1705) |

|

English botanist who wrote The Wisdom of God manifested in the Works of the Creation. (1691) The John Ray Initiative of Environment and Christianity is also named for him. |

| Gottfried Leibniz Gottfried Leibniz Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was a German philosopher and mathematician. He wrote in different languages, primarily in Latin , French and German .... (1646–1716) |

|

Polymath Polymath A polymath is a person whose expertise spans a significant number of different subject areas. In less formal terms, a polymath may simply be someone who is very knowledgeable... who worked on determinants, a calculating machine Calculating machine A calculating machine is a machine designed to come up with calculations or, in other words, computations. One noted machine was the Victorian British scientist Charles Babbage's Difference Engine , designed in the 1840s but never completed in the inventor's lifetime... , He was a Lutheran who worked with convert to Catholicism John Frederick, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg John Frederick, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg John Frederick was duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and ruled over the Principality of Calenberg, a subdivision of the duchy, from 1665 until his death.... in hopes of a reunification between Catholicism and Lutheranism. He also wrote Vindication of the Justice of God. |

| Isaac Newton Isaac Newton Sir Isaac Newton PRS was an English physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist, and theologian, who has been "considered by many to be the greatest and most influential scientist who ever lived."... (1643–1727) |

|

He is regarded as one of the greatest scientists and mathematicians in history. Newton's study of the Bible and of the early Church Fathers Church Fathers The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were early and influential theologians, eminent Christian teachers and great bishops. Their scholarly works were used as a precedent for centuries to come... were among his greatest passions, though he consistently refused to swear his allegiance to the church. He wrote Observations upon the Prophecies of Daniel and the Apocalypse of St. John (Nontrinitarianism Nontrinitarianism Nontrinitarianism includes all Christian belief systems that disagree with the doctrine of the Trinity, namely, the teaching that God is three distinct hypostases and yet co-eternal, co-equal, and indivisibly united in one essence or ousia... ). |

| Colin Maclaurin Colin Maclaurin Colin Maclaurin was a Scottish mathematician who made important contributions to geometry and algebra. The Maclaurin series, a special case of the Taylor series, are named after him.... (1698–1746) |

|