Timeline of chemistry

Encyclopedia

Chemistry

Chemistry is the science of matter, especially its chemical reactions, but also its composition, structure and properties. Chemistry is concerned with atoms and their interactions with other atoms, and particularly with the properties of chemical bonds....

, defined as the scientific study of the composition of matter and of its interactions. The history of chemistry

History of chemistry

By 1000 BC, ancient civilizations used technologies that would eventually form the basis of the various branches of chemistry. Examples include extracting metals from ores, making pottery and glazes, fermenting beer and wine, making pigments for cosmetics and painting, extracting chemicals from...

in its modern form arguably began with the English scientist Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle FRS was a 17th century natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, and inventor, also noted for his writings in theology. He has been variously described as English, Irish, or Anglo-Irish, his father having come to Ireland from England during the time of the English plantations of...

, though its roots can be traced back to the earliest recorded history.

Early ideas that later became incorporated into the modern science of chemistry come from two main sources. Natural philosophers

Natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or the philosophy of nature , is a term applied to the study of nature and the physical universe that was dominant before the development of modern science...

(such as Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

and Democritus

Democritus

Democritus was an Ancient Greek philosopher born in Abdera, Thrace, Greece. He was an influential pre-Socratic philosopher and pupil of Leucippus, who formulated an atomic theory for the cosmos....

) used deductive reasoning

Deductive reasoning

Deductive reasoning, also called deductive logic, is reasoning which constructs or evaluates deductive arguments. Deductive arguments are attempts to show that a conclusion necessarily follows from a set of premises or hypothesis...

in an attempt to explain the behavior of the world around them. Alchemists

Alchemy

Alchemy is an influential philosophical tradition whose early practitioners’ claims to profound powers were known from antiquity. The defining objectives of alchemy are varied; these include the creation of the fabled philosopher's stone possessing powers including the capability of turning base...

(such as Geber

Geber

Abu Musa Jābir ibn Hayyān, often known simply as Geber, was a prominent polymath: a chemist and alchemist, astronomer and astrologer, engineer, geologist, philosopher, physicist, and pharmacist and physician. Born and educated in Tus, he later traveled to Kufa...

and Rhazes) were people who used experimental techniques in an attempt to extend the life or perform material conversions, such as turning base metals into gold.

In the 17th century, a synthesis of the ideas of these two disciplines, that is the deductive and the experimental, leads to the development of a process of thinking known as the scientific method

Scientific method

Scientific method refers to a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge. To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry must be based on gathering empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of...

. With the introduction of the scientific method, the modern science of chemistry was born.

Known as "the central science

The central science

Chemistry is often called the central science because of its role in connecting the physical sciences, which include chemistry, with the life sciences and applied sciences such as medicine and engineering. The nature of this relationship is one of the main topics in the philosophy of chemistry and...

", the study of chemistry is strongly influenced by, and exerts a strong influence on, many other scientific and technological fields. Many events considered central to our modern understanding of chemistry are also considered key discoveries in such fields as physics, biology, astronomy, geology, and materials science to name a few.

Pre-17th century

Scientific method

Scientific method refers to a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge. To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry must be based on gathering empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of...

and its application to the field of chemistry, it is somewhat controversial to consider many of the people listed below as "chemists" in the modern sense of the word. However, the ideas of certain great thinkers, either for their prescience, or for their wide and long-term acceptance, bear listing here.

c. 3000 BCE: Egyptians

Egyptians

Egyptians are nation an ethnic group made up of Mediterranean North Africans, the indigenous people of Egypt.Egyptian identity is closely tied to geography. The population of Egypt is concentrated in the lower Nile Valley, the small strip of cultivable land stretching from the First Cataract to...

formulate the theory of the Ogdoad

Ogdoad

In Egyptian mythology, the Ogdoad were eight deities worshipped in Hermopolis during what is called the Old Kingdom, the third through sixth dynasties, dated between 2686 to 2134 BC...

, or the “primordial forces”, from which all was formed. These were the elements of chaos

Chaos (cosmogony)

Chaos refers to the formless or void state preceding the creation of the universe or cosmos in the Greek creation myths, more specifically the initial "gap" created by the original separation of heaven and earth....

, numbered in eight, that existed before the creation of the sun.

c. 1900 BCE: Hermes Trismegistus

Hermes Trismegistus

Hermes Trismegistus is the eponymous author of the Hermetic Corpus, a sacred text belonging to the genre of divine revelation.-Origin and identity:...

, semi-mythical ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt was an ancient civilization of Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh...

ian adept king, is thought to have founded the art of alchemy

Alchemy

Alchemy is an influential philosophical tradition whose early practitioners’ claims to profound powers were known from antiquity. The defining objectives of alchemy are varied; these include the creation of the fabled philosopher's stone possessing powers including the capability of turning base...

.

c. 1200 BCE: Tapputi-Belatikallim

Tapputi

Tapputi, also referred to as Tapputi-Belatekallim, is considered to be the world’s first chemist, a perfume-maker mentioned in a cuneiform tablet from the second millennium BC in Mesopotamia. She used flowers, oil, and calamus along with cyperus, myrrh, and balsam. She added water then distilled...

, a perfume-maker and early chemist, was mentioned in a cuneiform

Cuneiform

Cuneiform can refer to:*Cuneiform script, an ancient writing system originating in Mesopotamia in the 4th millennium BC*Cuneiform , three bones in the human foot*Cuneiform Records, a music record label...

tablet in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a toponym for the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran.Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Bronze Age Mesopotamia included Sumer and the...

.

c. 450 BCE: Empedocles

Empedocles

Empedocles was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a citizen of Agrigentum, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for being the originator of the cosmogenic theory of the four Classical elements...

asserts that all things are composed of four primal elements

Chemical element

A chemical element is a pure chemical substance consisting of one type of atom distinguished by its atomic number, which is the number of protons in its nucleus. Familiar examples of elements include carbon, oxygen, aluminum, iron, copper, gold, mercury, and lead.As of November 2011, 118 elements...

: earth, air, fire, and water, whereby two active and opposing force

Force

In physics, a force is any influence that causes an object to undergo a change in speed, a change in direction, or a change in shape. In other words, a force is that which can cause an object with mass to change its velocity , i.e., to accelerate, or which can cause a flexible object to deform...

s, love and hate, or affinity and antipathy, act upon these elements, combining and separating them into infinitely varied forms.

c. 440 BCE: Leucippus

Leucippus

Leucippus or Leukippos was one of the earliest Greeks to develop the theory of atomism — the idea that everything is composed entirely of various imperishable, indivisible elements called atoms — which was elaborated in greater detail by his pupil and successor, Democritus...

and Democritus

Democritus

Democritus was an Ancient Greek philosopher born in Abdera, Thrace, Greece. He was an influential pre-Socratic philosopher and pupil of Leucippus, who formulated an atomic theory for the cosmos....

propose the idea of the atom, an indivisible particle that all matter is made of. This idea is largely rejected by natural philosophers in favor of the Aristotlean view.

c. 360 BCE: Plato

Plato

Plato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

coins term ‘elements

Classical element

Many philosophies and worldviews have a set of classical elements believed to reflect the simplest essential parts and principles of which anything consists or upon which the constitution and fundamental powers of anything are based. Most frequently, classical elements refer to ancient beliefs...

’ (stoicheia) and in his dialogue Timaeus

Timaeus (dialogue)

Timaeus is one of Plato's dialogues, mostly in the form of a long monologue given by the title character, written circa 360 BC. The work puts forward speculation on the nature of the physical world and human beings. It is followed by the dialogue Critias.Speakers of the dialogue are Socrates,...

, which includes a discussion of the composition of inorganic and organic bodies and is a rudimentary treatise on chemistry, assumes that the minute particle of each element had a special geometric shape: tetrahedron

Tetrahedron

In geometry, a tetrahedron is a polyhedron composed of four triangular faces, three of which meet at each vertex. A regular tetrahedron is one in which the four triangles are regular, or "equilateral", and is one of the Platonic solids...

(fire), octahedron

Octahedron

In geometry, an octahedron is a polyhedron with eight faces. A regular octahedron is a Platonic solid composed of eight equilateral triangles, four of which meet at each vertex....

(air), icosahedron

Icosahedron

In geometry, an icosahedron is a regular polyhedron with 20 identical equilateral triangular faces, 30 edges and 12 vertices. It is one of the five Platonic solids....

(water), and cube

Cube

In geometry, a cube is a three-dimensional solid object bounded by six square faces, facets or sides, with three meeting at each vertex. The cube can also be called a regular hexahedron and is one of the five Platonic solids. It is a special kind of square prism, of rectangular parallelepiped and...

(earth).

c. 350 BCE: Aristotle

Aristotle

Aristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

, expanding on Empedocles, proposes idea of a substance as a combination of matter and form. Describes theory of the Five Elements

Five elements

Five elements may refer to: In philosophy: *Five elements *Mahabhuta*Pancha Tattva *Five elements In science:*Boron, element 5*Group 5 element*Period 5 element-See also:...

, fire, water, earth, air, and aether. This theory is largely accepted throughout the western world for over 1000 years.

c. 50 BCE: Lucretius

Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is an epic philosophical poem laying out the beliefs of Epicureanism, De rerum natura, translated into English as On the Nature of Things or "On the Nature of the Universe".Virtually no details have come down concerning...

publishes De Rerum Natura

On the Nature of Things

De rerum natura is a 1st century BC didactic poem by the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius with the goal of explaining Epicurean philosophy to a Roman audience. The poem, written in some 7,400 dactylic hexameters, is divided into six untitled books, and explores Epicurean physics through richly...

, a poetic description of the ideas of Atomism

Atomism

Atomism is a natural philosophy that developed in several ancient traditions. The atomists theorized that the natural world consists of two fundamental parts: indivisible atoms and empty void.According to Aristotle, atoms are indestructible and immutable and there are an infinite variety of shapes...

.

c. 300: Zosimos of Panopolis

Zosimos of Panopolis

Zosimos of Panopolis was an Egyptian or Greek alchemist and Gnostic mystic from the end of the 3rd and beginning of the 4th century AD. He was born in Panopolis, present day Akhmim in the south of Egypt, ca. 300. He wrote the oldest known books on alchemy, of which quotations in the Greek language...

writes some of the oldest known books on alchemy

Alchemy

Alchemy is an influential philosophical tradition whose early practitioners’ claims to profound powers were known from antiquity. The defining objectives of alchemy are varied; these include the creation of the fabled philosopher's stone possessing powers including the capability of turning base...

, which he defines as the study of the composition of waters, movement, growth, embodying and disembodying, drawing the spirits from bodies and bonding the spirits within bodies.

c. 770: Abu Musa Jabir ibn Hayyan

Geber

Abu Musa Jābir ibn Hayyān, often known simply as Geber, was a prominent polymath: a chemist and alchemist, astronomer and astrologer, engineer, geologist, philosopher, physicist, and pharmacist and physician. Born and educated in Tus, he later traveled to Kufa...

(aka Geber), an Arab/Persian alchemist who is "considered by many to be the father of chemistry", develops an early experimental method

Scientific method

Scientific method refers to a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge. To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry must be based on gathering empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of...

for chemistry, and isolates numerous acid

Acid

An acid is a substance which reacts with a base. Commonly, acids can be identified as tasting sour, reacting with metals such as calcium, and bases like sodium carbonate. Aqueous acids have a pH of less than 7, where an acid of lower pH is typically stronger, and turn blue litmus paper red...

s, including hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid is a solution of hydrogen chloride in water, that is a highly corrosive, strong mineral acid with many industrial uses. It is found naturally in gastric acid....

, nitric acid

Nitric acid

Nitric acid , also known as aqua fortis and spirit of nitre, is a highly corrosive and toxic strong acid.Colorless when pure, older samples tend to acquire a yellow cast due to the accumulation of oxides of nitrogen. If the solution contains more than 86% nitric acid, it is referred to as fuming...

, citric acid

Citric acid

Citric acid is a weak organic acid. It is a natural preservative/conservative and is also used to add an acidic, or sour, taste to foods and soft drinks...

, acetic acid

Acetic acid

Acetic acid is an organic compound with the chemical formula CH3CO2H . It is a colourless liquid that when undiluted is also called glacial acetic acid. Acetic acid is the main component of vinegar , and has a distinctive sour taste and pungent smell...

, tartaric acid

Tartaric acid

Tartaric acid is a white crystalline diprotic organic acid. It occurs naturally in many plants, particularly grapes, bananas, and tamarinds; is commonly combined with baking soda to function as a leavening agent in recipes, and is one of the main acids found in wine. It is added to other foods to...

, and aqua regia

Aqua regia

Aqua regia or aqua regis is a highly corrosive mixture of acids, fuming yellow or red solution, also called nitro-hydrochloric acid. The mixture is formed by freshly mixing concentrated nitric acid and hydrochloric acid, usually in a volume ratio of 1:3, respectively...

.

c. 1000: Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī and Avicenna

Avicenna

Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Sīnā , commonly known as Ibn Sīnā or by his Latinized name Avicenna, was a Persian polymath, who wrote almost 450 treatises on a wide range of subjects, of which around 240 have survived...

, both Persian chemists, refute the practice of alchemy

Alchemy

Alchemy is an influential philosophical tradition whose early practitioners’ claims to profound powers were known from antiquity. The defining objectives of alchemy are varied; these include the creation of the fabled philosopher's stone possessing powers including the capability of turning base...

and the theory of the transmutation of metals

Philosopher's stone

The philosopher's stone is a legendary alchemical substance said to be capable of turning base metals into gold or silver. It was also sometimes believed to be an elixir of life, useful for rejuvenation and possibly for achieving immortality. For many centuries, it was the most sought-after goal...

.

c. 1167: Alchemists in the School of Salerno make the first references to the distillation of wine.

c. 1220: Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste

Robert Grosseteste or Grossetete was an English statesman, scholastic philosopher, theologian and Bishop of Lincoln. He was born of humble parents at Stradbroke in Suffolk. A.C...

publishes several Aristotelian commentaries where he lays out an early framework for the scientific method

Scientific method

Scientific method refers to a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge. To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry must be based on gathering empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of...

.

c 1250:Tadeo Alderotti develops Fractional distillation

Fractional distillation

Fractional distillation is the separation of a mixture into its component parts, or fractions, such as in separating chemical compounds by their boiling point by heating them to a temperature at which several fractions of the compound will evaporate. It is a special type of distillation...

, which is much more effective than its predecessors.

c 1260: St Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus

Albertus Magnus, O.P. , also known as Albert the Great and Albert of Cologne, is a Catholic saint. He was a German Dominican friar and a bishop, who achieved fame for his comprehensive knowledge of and advocacy for the peaceful coexistence of science and religion. Those such as James A. Weisheipl...

discovers Arsenic

Arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element with the symbol As, atomic number 33 and relative atomic mass 74.92. Arsenic occurs in many minerals, usually in conjunction with sulfur and metals, and also as a pure elemental crystal. It was first documented by Albertus Magnus in 1250.Arsenic is a metalloid...

and Silver nitrate

Silver nitrate

Silver nitrate is an inorganic compound with chemical formula . This compound is a versatile precursor to many other silver compounds, such as those used in photography. It is far less sensitive to light than the halides...

. He also made one of the first references to sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid is a strong mineral acid with the molecular formula . Its historical name is oil of vitriol. Pure sulfuric acid is a highly corrosive, colorless, viscous liquid. The salts of sulfuric acid are called sulfates...

.

c. 1267: Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon, O.F.M. , also known as Doctor Mirabilis , was an English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through empirical methods...

publishes Opus Maius, which among other things, proposes an early form of the scientific method, and contains results of his experiments with gunpowder

Gunpowder

Gunpowder, also known since in the late 19th century as black powder, was the first chemical explosive and the only one known until the mid 1800s. It is a mixture of sulfur, charcoal, and potassium nitrate - with the sulfur and charcoal acting as fuels, while the saltpeter works as an oxidizer...

.

c. 1310: Pseudo-Geber

Pseudo-Geber

Pseudo-Geber is the name assigned by modern scholars to an anonymous European alchemist born in the 13th century, sometimes identified with Paul of Taranto, who wrote books on alchemy and metallurgy, in Latin, under the pen name of "Geber". "Geber" is the shortened and Latinised form of the name...

, an anonymous Spanish alchemist who wrote under the name of Geber, publishes several books that establish the long-held theory that all metals were composed of various proportions of sulfur

Sulfur

Sulfur or sulphur is the chemical element with atomic number 16. In the periodic table it is represented by the symbol S. It is an abundant, multivalent non-metal. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with chemical formula S8. Elemental sulfur is a bright yellow...

and mercury

Mercury (element)

Mercury is a chemical element with the symbol Hg and atomic number 80. It is also known as quicksilver or hydrargyrum...

. He is one of the first to describe nitric acid

Nitric acid

Nitric acid , also known as aqua fortis and spirit of nitre, is a highly corrosive and toxic strong acid.Colorless when pure, older samples tend to acquire a yellow cast due to the accumulation of oxides of nitrogen. If the solution contains more than 86% nitric acid, it is referred to as fuming...

, aqua regia

Aqua regia

Aqua regia or aqua regis is a highly corrosive mixture of acids, fuming yellow or red solution, also called nitro-hydrochloric acid. The mixture is formed by freshly mixing concentrated nitric acid and hydrochloric acid, usually in a volume ratio of 1:3, respectively...

, and aqua fortis

Aqua fortis

Aqua fortis, or "strong water," in alchemy, is a solution of nitric acid in water. Being highly corrosive, the solution was used in alchemy for dissolving silver and most other metals with the notable exception of gold, which can only be dissolved using aqua regia...

.

c. 1530: Paracelsus

Paracelsus

Paracelsus was a German-Swiss Renaissance physician, botanist, alchemist, astrologer, and general occultist....

develops the study of iatrochemistry

Iatrochemistry

Iatrochemistry is a branch of both chemistry and medicine. Having its roots in alchemy, iatrochemistry seeks to provide chemical solutions to diseases and medical ailments....

, a subdiscipline of alchemy dedicated to extending the life, thus being the roots of the modern pharmaceutical industry. It is also claimed that he is the first to use the word "chemistry".

1597: Andreas Libavius

Andreas Libavius

Andreas Libavius was a German doctor and chemist.-Life:Libavius was born in Halle, Germany, as Andreas Libau. In Halle he attended the gymnasium and studied from the year 1576 in University of Wittenberg. From 1577 on he studied in the University of Jena in the faculties of philosophy and history...

publishes Alchemia, a prototype chemistry

Chemistry

Chemistry is the science of matter, especially its chemical reactions, but also its composition, structure and properties. Chemistry is concerned with atoms and their interactions with other atoms, and particularly with the properties of chemical bonds....

textbook.

17th and 18th centuries

1605:Sir Francis Bacon publishes The Proficience and Advancement of Learning, which contains a description of what would later be known as the scientific methodScientific method

Scientific method refers to a body of techniques for investigating phenomena, acquiring new knowledge, or correcting and integrating previous knowledge. To be termed scientific, a method of inquiry must be based on gathering empirical and measurable evidence subject to specific principles of...

.

1605:Michal Sedziwój

Michal Sedziwój

Michał Sędziwój of Ostoja coat of arms was a Polish alchemist, philosopher, and medical doctor....

publishes the alchemical treatise A New Light of Alchemy which proposed the existence of the "food of life" within air, much later recognized as oxygen

Oxygen

Oxygen is the element with atomic number 8 and represented by the symbol O. Its name derives from the Greek roots ὀξύς and -γενής , because at the time of naming, it was mistakenly thought that all acids required oxygen in their composition...

.

1615:Jean Beguin

Jean Beguin

Jean Beguin was an iatrochemist noted for his 1610 Tyrocinium Chymicum , which many consider to be one of the first chemistry textbooks. In the 1615 edition of his textbook, Beguin made the first-ever chemical equation or rudimentary reaction diagrams, showing the results of reactions in which...

publishes the Tyrocinium Chymicum

Tyrocinium Chymicum

Tyrocinium Chymicum was a published set of chemistry lecture notes started by Jean Beguin in 1610 in Paris, France. It has been suggested that it was the first chemistry text book...

, an early chemistry textbook, and in it draws the first-ever chemical equation

Chemical equation

A chemical equation is the symbolic representation of a chemical reaction where the reactant entities are given on the left hand side and the product entities on the right hand side. The coefficients next to the symbols and formulae of entities are the absolute values of the stoichiometric numbers...

.

1637:René Descartes

René Descartes

René Descartes ; was a French philosopher and writer who spent most of his adult life in the Dutch Republic. He has been dubbed the 'Father of Modern Philosophy', and much subsequent Western philosophy is a response to his writings, which are studied closely to this day...

publishes Discours de la méthode, which contains an outline of the scientific method.

1648:Posthumous publication of the book Ortus medicinae by Jan Baptist van Helmont

Jan Baptist van Helmont

Jan Baptist van Helmont was an early modern period Flemish chemist, physiologist, and physician. He worked during the years just after Paracelsus and iatrochemistry, and is sometimes considered to be "the founder of pneumatic chemistry"...

, which is cited by some as a major transitional work between alchemy and chemistry, and as an important influence on Robert Boyle. The book contains the results of numerous experiments and establishes an early version of the Law of conservation of mass.

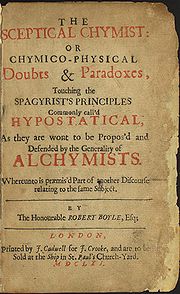

Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle FRS was a 17th century natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, and inventor, also noted for his writings in theology. He has been variously described as English, Irish, or Anglo-Irish, his father having come to Ireland from England during the time of the English plantations of...

publishes The Sceptical Chymist

The Sceptical Chymist

The Sceptical Chymist: or Chymico-Physical Doubts & Paradoxes is the title of Robert Boyle's masterpiece of scientific literature, published in London in 1661. In the form of a dialogue, the Sceptical Chymist presented Boyle's hypothesis that matter consisted of atoms and clusters of atoms in...

, a treatise on the distinction between chemistry and alchemy

Alchemy

Alchemy is an influential philosophical tradition whose early practitioners’ claims to profound powers were known from antiquity. The defining objectives of alchemy are varied; these include the creation of the fabled philosopher's stone possessing powers including the capability of turning base...

. It contains some of the earliest modern ideas of atom

Atom

The atom is a basic unit of matter that consists of a dense central nucleus surrounded by a cloud of negatively charged electrons. The atomic nucleus contains a mix of positively charged protons and electrically neutral neutrons...

s, molecule

Molecule

A molecule is an electrically neutral group of at least two atoms held together by covalent chemical bonds. Molecules are distinguished from ions by their electrical charge...

s, and chemical reaction

Chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. Chemical reactions can be either spontaneous, requiring no input of energy, or non-spontaneous, typically following the input of some type of energy, such as heat, light or electricity...

, and marks the beginning of the history of modern chemistry.

1662:Robert Boyle proposes Boyle's Law

Boyle's law

Boyle's law is one of many gas laws and a special case of the ideal gas law. Boyle's law describes the inversely proportional relationship between the absolute pressure and volume of a gas, if the temperature is kept constant within a closed system...

, an experimentally based description of the behavior of gas

Gas

Gas is one of the three classical states of matter . Near absolute zero, a substance exists as a solid. As heat is added to this substance it melts into a liquid at its melting point , boils into a gas at its boiling point, and if heated high enough would enter a plasma state in which the electrons...

es, specifically the relationship between pressure

Pressure

Pressure is the force per unit area applied in a direction perpendicular to the surface of an object. Gauge pressure is the pressure relative to the local atmospheric or ambient pressure.- Definition :...

and volume

Volume

Volume is the quantity of three-dimensional space enclosed by some closed boundary, for example, the space that a substance or shape occupies or contains....

.

1735:Swedish chemist Georg Brandt

Georg Brandt

-External links:** by Uno Boklund in: Charles C. Gillispie, ed., Dictionary of Scientific Biography , vol. 2, pages 421-422....

analyzes a dark blue pigment found in copper ore. Brandt demonstrated that the pigment contained a new element, later named cobalt

Cobalt

Cobalt is a chemical element with symbol Co and atomic number 27. It is found naturally only in chemically combined form. The free element, produced by reductive smelting, is a hard, lustrous, silver-gray metal....

.

1754:Joseph Black

Joseph Black

Joseph Black FRSE FRCPE FPSG was a Scottish physician and chemist, known for his discoveries of latent heat, specific heat, and carbon dioxide. He was professor of Medicine at University of Glasgow . James Watt, who was appointed as philosophical instrument maker at the same university...

isolates carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a naturally occurring chemical compound composed of two oxygen atoms covalently bonded to a single carbon atom...

, which he called "fixed air".

1757:Louis Claude Cadet de Gassicourt

Louis Claude Cadet de Gassicourt

Louis Claude Cadet de Gassicourt was a French chemist who synthesised the first organometalic compound.He obtained a red liquid by the reaction of potassium acetate with arsenic trioxide...

, while investigating arsenic compounds, creates Cadet's fuming liquid

Cadet's fuming liquid

Cadet's fuming liquid was the first organometallic compound to be synthesized. In 1760, the French chemist Louis Claude Cadet de Gassicourt synthesized a red liquid by the reaction of potassium acetate with arsenic trioxide....

, later discovered to be Cacodyl oxide

Cacodyl oxide

Cacodyl oxide is a chemical compound of the formula [2As]2O. This organoarsenic compound is primarily of historical significance as it is sometimes considered to be the first organometallic compound synthesized in relatively pure form....

, considered to be the first synthetic organometallic compound.

1758:Joseph Black formulates the concept of latent heat

Latent heat

Latent heat is the heat released or absorbed by a chemical substance or a thermodynamic system during a process that occurs without a change in temperature. A typical example is a change of state of matter, meaning a phase transition such as the melting of ice or the boiling of water. The term was...

to explain the thermochemistry

Thermochemistry

Thermochemistry is the study of the energy and heat associated with chemical reactions and/or physical transformations. A reaction may release or absorb energy, and a phase change may do the same, such as in melting and boiling. Thermochemistry focuses on these energy changes, particularly on the...

of phase changes.

1766:Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish FRS was a British scientist noted for his discovery of hydrogen or what he called "inflammable air". He described the density of inflammable air, which formed water on combustion, in a 1766 paper "On Factitious Airs". Antoine Lavoisier later reproduced Cavendish's experiment and...

discovers hydrogen

Hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with atomic number 1. It is represented by the symbol H. With an average atomic weight of , hydrogen is the lightest and most abundant chemical element, constituting roughly 75% of the Universe's chemical elemental mass. Stars in the main sequence are mainly...

as a colorless, odourless gas that burns and can form an explosive mixture with air.

1773–1774: Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele

Carl Wilhelm Scheele was a German-Swedish pharmaceutical chemist. Isaac Asimov called him "hard-luck Scheele" because he made a number of chemical discoveries before others who are generally given the credit...

and Joseph Priestly independently isolate oxygen, called by Priestly "dephlogisticated air" and Scheele "fire air".

Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier , the "father of modern chemistry", was a French nobleman prominent in the histories of chemistry and biology...

, considered "The father of modern chemistry", recognizes and names oxygen, and recognizes its importance and role in combustion.

1787:Antoine Lavoisier publishes Méthode de nomenclature chimique, the first modern system of chemical nomenclature.

1787:Jacques Charles

Jacques Charles

Jacques Alexandre César Charles was a French inventor, scientist, mathematician, and balloonist.Charles and the Robert brothers launched the world's first hydrogen-filled balloon in August 1783, then in December 1783, Charles and his co-pilot Nicolas-Louis Robert ascended to a height of about...

proposes Charles's Law

Charles's law

Charles' law is an experimental gas law which describes how gases tend to expand when heated. It was first published by French natural philosopher Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac in 1802, although he credited the discovery to unpublished work from the 1780s by Jacques Charles...

, a corollary of Boyle's Law, describes relationship between temperature

Temperature

Temperature is a physical property of matter that quantitatively expresses the common notions of hot and cold. Objects of low temperature are cold, while various degrees of higher temperatures are referred to as warm or hot...

and volume of a gas.

1789:Antoine Lavoisier publishes Traité Élémentaire de Chimie

Traité Élémentaire de Chimie

Traité élémentaire de chimie is an influential textbook written by Antoine Lavoisier published in 1789 and translated into English by Robert Kerr in 1790.The book is considered to be the first modern chemical textbook...

, the first modern chemistry textbook. It is a complete survey of (at that time) modern chemistry, including the first concise definition of the law of conservation of mass, and thus also represents the founding of the discipline of stoichiometry

Stoichiometry

Stoichiometry is a branch of chemistry that deals with the relative quantities of reactants and products in chemical reactions. In a balanced chemical reaction, the relations among quantities of reactants and products typically form a ratio of whole numbers...

or quantitative chemical analysis.

1797:Joseph Proust

Joseph Proust

Joseph Louis Proust was a French chemist.-Life:Joseph L. Proust was born on September 26, 1754 in Angers, France. His father served as an apothecary in Angers. Joseph studied chemistry in his father’s shop and later came to Paris where he gained the appointment of apothecary in chief to the...

proposes the law of definite proportions

Law of definite proportions

In chemistry, the law of definite proportions, sometimes called Proust's Law, states that a chemical compound always contains exactly the same proportion of elements by mass. An equivalent statement is the law of constant composition, which states that all samples of a given chemical compound have...

, which states that elements always combine in small, whole number ratios to form compounds.

1800:Alessandro Volta

Alessandro Volta

Count Alessandro Giuseppe Antonio Anastasio Gerolamo Umberto Volta was a Lombard physicist known especially for the invention of the battery in 1800.-Early life and works:...

devises the first chemical battery

Voltaic pile

A voltaic pile is a set of individual Galvanic cells placed in series. The voltaic pile, invented by Alessandro Volta in 1800, was the first electric battery...

, thereby founding the discipline of electrochemistry

Electrochemistry

Electrochemistry is a branch of chemistry that studies chemical reactions which take place in a solution at the interface of an electron conductor and an ionic conductor , and which involve electron transfer between the electrode and the electrolyte or species in solution.If a chemical reaction is...

.

19th century

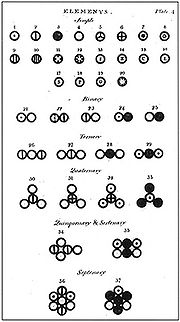

John Dalton

John Dalton FRS was an English chemist, meteorologist and physicist. He is best known for his pioneering work in the development of modern atomic theory, and his research into colour blindness .-Early life:John Dalton was born into a Quaker family at Eaglesfield, near Cockermouth, Cumberland,...

proposes Dalton's Law

Dalton's law

In chemistry and physics, Dalton's law states that the total pressure exerted by a gaseous mixture is equal to the sum of the partial pressures of each individual component in a gas mixture...

, which describes relationship between the components in a mixture of gases and the relative pressure each contributes to that of the overall mixture.

1805:Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac

Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac

- External links :* from the American Chemical Society* from the Encyclopædia Britannica, 10th Edition * , Paris...

discovers that water is composed of two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen by volume.

1808:Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac collects and discovers several chemical and physical properties of air and of other gases, including experimental proofs of Boyle's and Charles's laws, and of relationships between density and composition of gases.

1808:John Dalton publishes New System of Chemical Philosophy, which contains first modern scientific description of the atomic theory

Atomic theory

In chemistry and physics, atomic theory is a theory of the nature of matter, which states that matter is composed of discrete units called atoms, as opposed to the obsolete notion that matter could be divided into any arbitrarily small quantity...

, and clear description of the law of multiple proportions

Law of multiple proportions

In chemistry, the law of multiple proportions is one of the basic laws of stoichiometry, alongside the law of definite proportions. It is sometimes called Dalton's Law after its discoverer, the English chemist John Dalton.The statement of the law is:...

.

1808:Jöns Jakob Berzelius

Jöns Jakob Berzelius

Jöns Jacob Berzelius was a Swedish chemist. He worked out the modern technique of chemical formula notation, and is together with John Dalton, Antoine Lavoisier, and Robert Boyle considered a father of modern chemistry...

publishes Lärbok i Kemien in which he proposes modern chemical symbols and notation, and of the concept of relative atomic weight

Atomic weight

Atomic weight is a dimensionless physical quantity, the ratio of the average mass of atoms of an element to 1/12 of the mass of an atom of carbon-12...

.

1811:Amedeo Avogadro

Amedeo Avogadro

Lorenzo Romano Amedeo Carlo Avogadro di Quaregna e di Cerreto, Count of Quaregna and Cerreto was an Italian savant. He is most noted for his contributions to molecular theory, including what is known as Avogadro's law...

proposes Avogadro's law

Avogadro's law

Avogadro's law is a gas law named after Amedeo Avogadro who, in 1811, hypothesized that two given samples of an ideal gas, at the same temperature, pressure and volume, contain the same number of molecules...

, that equal volumes of gases under constant temperature and pressure contain equal number of molecules.

Friedrich Wöhler

Friedrich Wöhler was a German chemist, best known for his synthesis of urea, but also the first to isolate several chemical elements.-Biography:He was born in Eschersheim, which belonged to aau...

and Justus von Liebig

Justus von Liebig

Justus von Liebig was a German chemist who made major contributions to agricultural and biological chemistry, and worked on the organization of organic chemistry. As a professor, he devised the modern laboratory-oriented teaching method, and for such innovations, he is regarded as one of the...

perform the first confirmed discovery and explanation of isomers, earlier named by Berzelius. Working with cyanic acid and fulminic acid, they correctly deduce that isomerism was caused by differing arrangements of atoms within a molecular structure.

1827:William Prout classifies biomolecules into their modern groupings: carbohydrates, proteins and lipids.

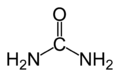

1828:Friedrich Wöhler synthesizes urea

Urea

Urea or carbamide is an organic compound with the chemical formula CO2. The molecule has two —NH2 groups joined by a carbonyl functional group....

, thereby establishing that organic compounds could be produced from inorganic starting materials, disproving the theory of vitalism

Vitalism

Vitalism, as defined by the Merriam-Webster dictionary, is#a doctrine that the functions of a living organism are due to a vital principle distinct from biochemical reactions...

.

1832:Friedrich Wöhler and Justus von Liebig discover and explain functional group

Functional group

In organic chemistry, functional groups are specific groups of atoms within molecules that are responsible for the characteristic chemical reactions of those molecules. The same functional group will undergo the same or similar chemical reaction regardless of the size of the molecule it is a part of...

s and radicals

Radical (chemistry)

Radicals are atoms, molecules, or ions with unpaired electrons on an open shell configuration. Free radicals may have positive, negative, or zero charge...

in relation to organic chemistry.

1840:Germain Hess proposes Hess's Law

Hess's law

Hess' law is a relationship in physical chemistry named for Germain Hess, a Swiss-born Russian chemist and physician.The law states that the enthalpy change for a reaction that is carried out in a series of steps is equal to the sum of the enthalpy changes for the individual steps.The law is an...

, an early statement of the Law of conservation of energy, which establishes that energy changes in a chemical process depend only on the states of the starting and product materials and not on the specific pathway taken between the two states.

1847:Hermann Kolbe obtains acetic acid

Acetic acid

Acetic acid is an organic compound with the chemical formula CH3CO2H . It is a colourless liquid that when undiluted is also called glacial acetic acid. Acetic acid is the main component of vinegar , and has a distinctive sour taste and pungent smell...

from completely inorganic sources, further disproving vitalism.

1848:Lord Kelvin establishes concept of absolute zero

Absolute zero

Absolute zero is the theoretical temperature at which entropy reaches its minimum value. The laws of thermodynamics state that absolute zero cannot be reached using only thermodynamic means....

, the temperature at which all molecular motion ceases.

1849:Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur was a French chemist and microbiologist born in Dole. He is remembered for his remarkable breakthroughs in the causes and preventions of diseases. His discoveries reduced mortality from puerperal fever, and he created the first vaccine for rabies and anthrax. His experiments...

discovers that the racemic

Racemic

In chemistry, a racemic mixture, or racemate , is one that has equal amounts of left- and right-handed enantiomers of a chiral molecule. The first known racemic mixture was "racemic acid", which Louis Pasteur found to be a mixture of the two enantiomeric isomers of tartaric acid.- Nomenclature :A...

form of tartaric acid

Tartaric acid

Tartaric acid is a white crystalline diprotic organic acid. It occurs naturally in many plants, particularly grapes, bananas, and tamarinds; is commonly combined with baking soda to function as a leavening agent in recipes, and is one of the main acids found in wine. It is added to other foods to...

is a mixture of the levorotatory and dextrotatory forms, thus clarifying the nature of optical rotation

Optical rotation

Optical rotation is the turning of the plane of linearly polarized light about the direction of motion as the light travels through certain materials. It occurs in solutions of chiral molecules such as sucrose , solids with rotated crystal planes such as quartz, and spin-polarized gases of atoms...

and advancing the field of stereochemistry

Stereochemistry

Stereochemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, involves the study of the relative spatial arrangement of atoms within molecules. An important branch of stereochemistry is the study of chiral molecules....

.

1852:August Beer

August Beer

August Beer was a German physicist and mathematician. Beer was born in Trier, where he studied mathematics and natural sciences. He worked for Julius Plücker in Bonn afterwards, where he earned a Ph.D. in 1848 and became a lecturer in 1850. In 1854, Beer published his book Einleitung in die höhere...

proposes Beer's law, which explains the relationship between the composition of a mixture and the amount of light it will absorb. Based partly on earlier work by Pierre Bouguer

Pierre Bouguer

Pierre Bouguer was a French mathematician, geophysicist, geodesist, and astronomer. He is also known as "the father of naval architecture"....

and Johann Heinrich Lambert

Johann Heinrich Lambert

Johann Heinrich Lambert was a Swiss mathematician, physicist, philosopher and astronomer.Asteroid 187 Lamberta was named in his honour.-Biography:...

, it establishes the analytical

Analytical chemistry

Analytical chemistry is the study of the separation, identification, and quantification of the chemical components of natural and artificial materials. Qualitative analysis gives an indication of the identity of the chemical species in the sample and quantitative analysis determines the amount of...

technique known as spectrophotometry

Spectrophotometry

In chemistry, spectrophotometry is the quantitative measurement of the reflection or transmission properties of a material as a function of wavelength...

.

1855:Benjamin Silliman, Jr. pioneers methods of petroleum cracking, which makes the entire modern petrochemical

Petrochemical

Petrochemicals are chemical products derived from petroleum. Some chemical compounds made from petroleum are also obtained from other fossil fuels, such as coal or natural gas, or renewable sources such as corn or sugar cane....

industry possible.

1856:William Henry Perkin synthesizes Perkin's mauve, the first synthetic dye. Created as an accidental byproduct of an attempt to create quinine

Quinine

Quinine is a natural white crystalline alkaloid having antipyretic , antimalarial, analgesic , anti-inflammatory properties and a bitter taste. It is a stereoisomer of quinidine which, unlike quinine, is an anti-arrhythmic...

from coal tar

Coal tar

Coal tar is a brown or black liquid of extremely high viscosity, which smells of naphthalene and aromatic hydrocarbons. Coal tar is among the by-products when coal iscarbonized to make coke or gasified to make coal gas...

. This discovery is the foundation of the dye synthesis industry, one of the earliest successful chemical industries.

1857:Friedrich August Kekulé von Stradonitz

Friedrich August Kekulé von Stradonitz

Friedrich August Kekule von Stradonitz was a German organic chemist. From the 1850s until his death, Kekule was one of the most prominent chemists in Europe, especially in theoretical chemistry...

proposes that carbon

Carbon

Carbon is the chemical element with symbol C and atomic number 6. As a member of group 14 on the periodic table, it is nonmetallic and tetravalent—making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds...

is tetravalent, or forms exactly four chemical bonds.

1859–1860: Gustav Kirchhoff

Gustav Kirchhoff

Gustav Robert Kirchhoff was a German physicist who contributed to the fundamental understanding of electrical circuits, spectroscopy, and the emission of black-body radiation by heated objects...

and Robert Bunsen

Robert Bunsen

Robert Wilhelm Eberhard Bunsen was a German chemist. He investigated emission spectra of heated elements, and discovered caesium and rubidium with Gustav Kirchhoff. Bunsen developed several gas-analytical methods, was a pioneer in photochemistry, and did early work in the field of organoarsenic...

lay the foundations of spectroscopy

Spectroscopy

Spectroscopy is the study of the interaction between matter and radiated energy. Historically, spectroscopy originated through the study of visible light dispersed according to its wavelength, e.g., by a prism. Later the concept was expanded greatly to comprise any interaction with radiative...

as a means of chemical analysis, which lead them to the discovery of caesium

Caesium

Caesium or cesium is the chemical element with the symbol Cs and atomic number 55. It is a soft, silvery-gold alkali metal with a melting point of 28 °C , which makes it one of only five elemental metals that are liquid at room temperature...

and rubidium

Rubidium

Rubidium is a chemical element with the symbol Rb and atomic number 37. Rubidium is a soft, silvery-white metallic element of the alkali metal group. Its atomic mass is 85.4678. Elemental rubidium is highly reactive, with properties similar to those of other elements in group 1, such as very rapid...

. Other workers soon used the same technique to discover indium

Indium

Indium is a chemical element with the symbol In and atomic number 49. This rare, very soft, malleable and easily fusible post-transition metal is chemically similar to gallium and thallium, and shows the intermediate properties between these two...

, thalium, and helium

Helium

Helium is the chemical element with atomic number 2 and an atomic weight of 4.002602, which is represented by the symbol He. It is a colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, inert, monatomic gas that heads the noble gas group in the periodic table...

.

1860:Stanislao Cannizzaro

Stanislao Cannizzaro

Stanislao Cannizzaro, FRS was an Italian chemist. He is remembered today largely for the Cannizzaro reaction and for his influential role in the atomic-weight deliberations of the Karlsruhe Congress in 1860.-Biography:...

, resurrecting Avogadro's ideas regarding diatomic molecules, compiles a table of atomic weight

Atomic weight

Atomic weight is a dimensionless physical quantity, the ratio of the average mass of atoms of an element to 1/12 of the mass of an atom of carbon-12...

s and presents it at the 1860 Karlsruhe Congress

Karlsruhe Congress

The Karlsruhe Congress was an international meeting of chemists held in Karlsruhe, Germany from 3 to 5 September, 1860. It was the first international conference of chemistry worldwide.- The meeting :...

, ending decades of conflicting atomic weights and molecular formulas, and leading to Mendeleev's discovery of the periodic law.

1862:Alexander Parkes

Alexander Parkes

Alexander Parkes was a metallurgist and inventor from Birmingham, England. He created Parkesine, the first man-made plastic.-Biography:...

exhibits Parkesine

Parkesine

Parkesine is the trademark for the first man-made plastic. It was patented by Alexander Parkes in 1856. In 1866 Parkes formed the Parkesine Company to mass produce the material. The company, however, failed due to poor product quality as Parkes tried to reduce costs...

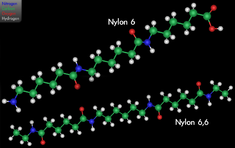

, one of the earliest synthetic polymer

Synthetic polymer

Synthetic polymers are often referred to as "plastics", such as the well-known polyethylene and nylon. However, most of them can be classified in at least three main categories: thermoplastics, thermosets and elastomers....

s, at the International Exhibition in London. This discovery formed the foundation of the modern plastics industry.

1862:Alexandre-Emile Béguyer de Chancourtois

Alexandre-Emile Béguyer de Chancourtois

Alexandre-Emile Béguyer de Chancourtois was a French geologist and mineralogist who was the first to arrange the chemical elements in order of atomic weights, doing so in 1862. De Chancourtois only published his paper, but did not publish his actual graph with the proposed arrangement...

publishes the telluric helix, an early, three-dimensional version of the Periodic Table of the Elements

Periodic table

The periodic table of the chemical elements is a tabular display of the 118 known chemical elements organized by selected properties of their atomic structures. Elements are presented by increasing atomic number, the number of protons in an atom's atomic nucleus...

.

1864:John Newlands

John Alexander Reina Newlands

John Alexander Reina Newlands was an English chemist who invented the Periodic Table.Newlands was born in London and was the son of a scottish Presbyterian minister and his Italian wife....

proposes the law of octaves, a precursor to the Periodic Law.

1864:Lothar Meyer develops an early version of the periodic table, with 28 elements organized by valence

Valence (chemistry)

In chemistry, valence, also known as valency or valence number, is a measure of the number of bonds formed by an atom of a given element. "Valence" can be defined as the number of valence bonds...

.

1864:Cato Maximilian Guldberg

Cato Maximilian Guldberg

Cato Maximilian Guldberg was a Norwegian mathematician and chemist.-Career:Guldberg worked at the Royal Frederick University. Together with his brother-in-law, Peter Waage, he proposed the law of mass action...

and Peter Waage

Peter Waage

Peter Waage , the son of a ship's captain, was a significant Norwegian chemist and professor at the Royal Frederick University. Along with his brother-in-law Cato Maximilian Guldberg, he co-discovered and developed the law of mass action between 1864 and 1879.He grew up in Hidra...

, building on Claude Louis Berthollet’s ideas, proposed the Law of Mass Action.

1865:Johann Josef Loschmidt

Johann Josef Loschmidt

Jan or Johann Josef Loschmidt , who referred to himself mostly as 'Josef' , was a notable Austrian scientist who performed groundbreaking work in chemistry, physics , and crystal forms.Born in Carlsbad, a town located in the Austrian Empire , Loschmidt...

determines exact number of molecules in a mole

Mole (unit)

The mole is a unit of measurement used in chemistry to express amounts of a chemical substance, defined as an amount of a substance that contains as many elementary entities as there are atoms in 12 grams of pure carbon-12 , the isotope of carbon with atomic weight 12. This corresponds to a value...

, later named Avogadro's Number

Avogadro's number

In chemistry and physics, the Avogadro constant is defined as the ratio of the number of constituent particles N in a sample to the amount of substance n through the relationship NA = N/n. Thus, it is the proportionality factor that relates the molar mass of an entity, i.e...

.

1865:Friedrich August Kekulé von Stradonitz, based partially on the work of Loschmidt and others, establishes structure of benzene as a six carbon ring with alternating single and double bonds.

1865:Adolf von Baeyer

Adolf von Baeyer

Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Adolf von Baeyer was a German chemist who synthesized indigo, and was the 1905 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Born in Berlin, he initially studied mathematics and physics at Berlin University before moving to Heidelberg to study chemistry with Robert Bunsen...

begins work on indigo dye

Indigo dye

Indigo dye is an organic compound with a distinctive blue color . Historically, indigo was a natural dye extracted from plants, and this process was important economically because blue dyes were once rare. Nearly all indigo dye produced today — several thousand tons each year — is synthetic...

, a milestone in modern industrial organic chemistry which revolutionizes the dye industry.

Dmitri Mendeleev

Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev , was a Russian chemist and inventor. He is credited as being the creator of the first version of the periodic table of elements...

publishes the first modern periodic table, with the 66 known elements organized by atomic weights. The strength of his table was its ability to accurately predict the properties of as-yet unknown elements.

1873:Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff

Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff

Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff, Jr. was a Dutch physical and organic chemist and the first winner of the Nobel Prize in chemistry. He is best known for his discoveries in chemical kinetics, chemical equilibrium, osmotic pressure, and stereochemistry...

and Joseph Achille Le Bel

Joseph Achille Le Bel

Joseph Achille Le Bel was a French chemist. He is best known for his work in stereochemistry. Le Bel was educated at the École Polytechnique in Paris. In 1874 he announced his theory outlining the relationship between molecular structure and optical activity...

, working independently, develop a model of chemical bonding that explains the chirality experiments of Pasteur and provides a physical cause for optical activity in chiral compounds.

1876:Josiah Willard Gibbs

Josiah Willard Gibbs

Josiah Willard Gibbs was an American theoretical physicist, chemist, and mathematician. He devised much of the theoretical foundation for chemical thermodynamics as well as physical chemistry. As a mathematician, he invented vector analysis . Yale University awarded Gibbs the first American Ph.D...

publishes On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances

On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances

In the history of thermodynamics, On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances is a 300-page paper written by American mathematical-engineer Willard Gibbs...

, a compilation of his work on thermodynamics and physical chemistry

Physical chemistry

Physical chemistry is the study of macroscopic, atomic, subatomic, and particulate phenomena in chemical systems in terms of physical laws and concepts...

which lays out the concept of free energy

Thermodynamic free energy

The thermodynamic free energy is the amount of work that a thermodynamic system can perform. The concept is useful in the thermodynamics of chemical or thermal processes in engineering and science. The free energy is the internal energy of a system less the amount of energy that cannot be used to...

to explain the physical basis of chemical equilibria.

1877:Ludwig Boltzmann

Ludwig Boltzmann

Ludwig Eduard Boltzmann was an Austrian physicist famous for his founding contributions in the fields of statistical mechanics and statistical thermodynamics...

establishes statistical derivations of many important physical and chemical concepts, including entropy

Entropy

Entropy is a thermodynamic property that can be used to determine the energy available for useful work in a thermodynamic process, such as in energy conversion devices, engines, or machines. Such devices can only be driven by convertible energy, and have a theoretical maximum efficiency when...

, and distributions of molecular velocities in the gas phase.

1883:Svante Arrhenius

Svante Arrhenius

Svante August Arrhenius was a Swedish scientist, originally a physicist, but often referred to as a chemist, and one of the founders of the science of physical chemistry...

develops ion

Ion

An ion is an atom or molecule in which the total number of electrons is not equal to the total number of protons, giving it a net positive or negative electrical charge. The name was given by physicist Michael Faraday for the substances that allow a current to pass between electrodes in a...

theory to explain conductivity in electrolyte

Electrolyte

In chemistry, an electrolyte is any substance containing free ions that make the substance electrically conductive. The most typical electrolyte is an ionic solution, but molten electrolytes and solid electrolytes are also possible....

s.

1884:Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff publishes Études de Dynamique chimique, a seminal study on chemical kinetics

Chemical kinetics

Chemical kinetics, also known as reaction kinetics, is the study of rates of chemical processes. Chemical kinetics includes investigations of how different experimental conditions can influence the speed of a chemical reaction and yield information about the reaction's mechanism and transition...

.

1884:Hermann Emil Fischer

Hermann Emil Fischer

Hermann Emil Fischer, Emil Fischer was a German chemist and 1902 recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. He discovered the Fischer esterification. He developed the Fischer projection, a symbolic way of drawing asymmetric carbon atoms.-Early years:Fischer was born in Euskirchen, near Cologne,...

proposes structure of purine

Purine

A purine is a heterocyclic aromatic organic compound, consisting of a pyrimidine ring fused to an imidazole ring. Purines, including substituted purines and their tautomers, are the most widely distributed kind of nitrogen-containing heterocycle in nature....

, a key structure in many biomolecules, which he later synthesized in 1898. Also begins work on the chemistry of glucose

Glucose

Glucose is a simple sugar and an important carbohydrate in biology. Cells use it as the primary source of energy and a metabolic intermediate...

and related sugar

Sugar

Sugar is a class of edible crystalline carbohydrates, mainly sucrose, lactose, and fructose, characterized by a sweet flavor.Sucrose in its refined form primarily comes from sugar cane and sugar beet...

s.

1884:Henry Louis Le Chatelier develops Le Chatelier's principle

Le Châtelier's principle

In chemistry, Le Chatelier's principle, also called the Chatelier's principle, can be used to predict the effect of a change in conditions on a chemical equilibrium. The principle is named after Henry Louis Le Chatelier and sometimes Karl Ferdinand Braun who discovered it independently...

, which explains the response of dynamic chemical equilibria

Chemical equilibrium

In a chemical reaction, chemical equilibrium is the state in which the concentrations of the reactants and products have not yet changed with time. It occurs only in reversible reactions, and not in irreversible reactions. Usually, this state results when the forward reaction proceeds at the same...

to external stresses.

1885:Eugene Goldstein names the cathode ray

Cathode ray

Cathode rays are streams of electrons observed in vacuum tubes. If an evacuated glass tube is equipped with two electrodes and a voltage is applied, the glass opposite of the negative electrode is observed to glow, due to electrons emitted from and travelling perpendicular to the cathode Cathode...

, later discovered to be composed of electrons, and the canal ray, later discovered to be positive hydrogen ions that had been stripped of their electrons in a cathode ray tube

Cathode ray tube

The cathode ray tube is a vacuum tube containing an electron gun and a fluorescent screen used to view images. It has a means to accelerate and deflect the electron beam onto the fluorescent screen to create the images. The image may represent electrical waveforms , pictures , radar targets and...

. These would later be named proton

Proton

The proton is a subatomic particle with the symbol or and a positive electric charge of 1 elementary charge. One or more protons are present in the nucleus of each atom, along with neutrons. The number of protons in each atom is its atomic number....

s.

1893:Alfred Werner

Alfred Werner

Alfred Werner was a Swiss chemist who was a student at ETH Zurich and a professor at the University of Zurich. He won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1913 for proposing the octahedral configuration of transition metal complexes. Werner developed the basis for modern coordination chemistry...

discovers the octahedral structure of cobalt complexes, thus establishing the field of coordination chemistry.

1894–1898: William Ramsay

William Ramsay

Sir William Ramsay was a Scottish chemist who discovered the noble gases and received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1904 "in recognition of his services in the discovery of the inert gaseous elements in air" .-Early years:Ramsay was born in Glasgow on 2...

discovers the noble gases, which fill a large and unexpected gap in the periodic table and led to models of chemical bonding.

1897:J. J. Thomson

J. J. Thomson

Sir Joseph John "J. J." Thomson, OM, FRS was a British physicist and Nobel laureate. He is credited for the discovery of the electron and of isotopes, and the invention of the mass spectrometer...

discovers the electron

Electron

The electron is a subatomic particle with a negative elementary electric charge. It has no known components or substructure; in other words, it is generally thought to be an elementary particle. An electron has a mass that is approximately 1/1836 that of the proton...

using the cathode ray tube

Cathode ray tube

The cathode ray tube is a vacuum tube containing an electron gun and a fluorescent screen used to view images. It has a means to accelerate and deflect the electron beam onto the fluorescent screen to create the images. The image may represent electrical waveforms , pictures , radar targets and...

.

1898:Wilhelm Wien

Wilhelm Wien

Wilhelm Carl Werner Otto Fritz Franz Wien was a German physicist who, in 1893, used theories about heat and electromagnetism to deduce Wien's displacement law, which calculates the emission of a blackbody at any temperature from the emission at any one reference temperature.He also formulated an...

demonstrates that canal rays (streams of positive ions) can be deflected by magnetic fields, and that the amount of deflection is proportional to the mass-to-charge ratio

Mass-to-charge ratio

The mass-to-charge ratio ratio is a physical quantity that is widely used in the electrodynamics of charged particles, e.g. in electron optics and ion optics. It appears in the scientific fields of lithography, electron microscopy, cathode ray tubes, accelerator physics, nuclear physics, Auger...

. This discovery would lead to the analytical

Analytical chemistry

Analytical chemistry is the study of the separation, identification, and quantification of the chemical components of natural and artificial materials. Qualitative analysis gives an indication of the identity of the chemical species in the sample and quantitative analysis determines the amount of...

technique known as mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry is an analytical technique that measures the mass-to-charge ratio of charged particles.It is used for determining masses of particles, for determining the elemental composition of a sample or molecule, and for elucidating the chemical structures of molecules, such as peptides and...

.

1898:Maria Sklodowska-Curie and Pierre Curie

Pierre Curie

Pierre Curie was a French physicist, a pioneer in crystallography, magnetism, piezoelectricity and radioactivity, and Nobel laureate. He was the son of Dr. Eugène Curie and Sophie-Claire Depouilly Curie ...

isolate radium

Radium

Radium is a chemical element with atomic number 88, represented by the symbol Ra. Radium is an almost pure-white alkaline earth metal, but it readily oxidizes on exposure to air, becoming black in color. All isotopes of radium are highly radioactive, with the most stable isotope being radium-226,...

and polonium

Polonium

Polonium is a chemical element with the symbol Po and atomic number 84, discovered in 1898 by Marie Skłodowska-Curie and Pierre Curie. A rare and highly radioactive element, polonium is chemically similar to bismuth and tellurium, and it occurs in uranium ores. Polonium has been studied for...

from pitchblende.

c. 1900: Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson OM, FRS was a New Zealand-born British chemist and physicist who became known as the father of nuclear physics...

discovers the source of radioactivity as decaying atoms; coins terms for various types of radiation.

20th century

1903:Mikhail Semyonovich Tsvet invents chromatographyChromatography

Chromatography is the collective term for a set of laboratory techniques for the separation of mixtures....

, an important analytic technique.

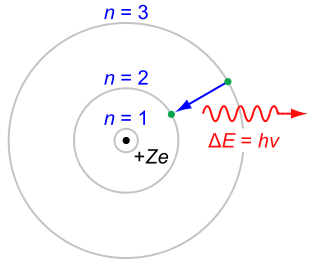

1904:Hantaro Nagaoka proposes an early nuclear model

Bohr model

In atomic physics, the Bohr model, introduced by Niels Bohr in 1913, depicts the atom as a small, positively charged nucleus surrounded by electrons that travel in circular orbits around the nucleus—similar in structure to the solar system, but with electrostatic forces providing attraction,...

of the atom, where electrons orbit a dense massive nucleus.

1905:Fritz Haber

Fritz Haber

Fritz Haber was a German chemist, who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1918 for his development for synthesizing ammonia, important for fertilizers and explosives. Haber, along with Max Born, proposed the Born–Haber cycle as a method for evaluating the lattice energy of an ionic solid...

and Carl Bosch

Carl Bosch

Carl Bosch was a German chemist and engineer and Nobel laureate in chemistry. He was a pioneer in the field of high-pressure industrial chemistry and founder of IG Farben, at one point the world's largest chemical company....

develop the Haber process

Haber process

The Haber process, also called the Haber–Bosch process, is the nitrogen fixation reaction of nitrogen gas and hydrogen gas, over an enriched iron or ruthenium catalyst, which is used to industrially produce ammonia....

for making ammonia

Ammonia

Ammonia is a compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . It is a colourless gas with a characteristic pungent odour. Ammonia contributes significantly to the nutritional needs of terrestrial organisms by serving as a precursor to food and fertilizers. Ammonia, either directly or...

from its elements, a milestone in industrial chemistry with deep consequences in agriculture.

1905:Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein was a German-born theoretical physicist who developed the theory of general relativity, effecting a revolution in physics. For this achievement, Einstein is often regarded as the father of modern physics and one of the most prolific intellects in human history...

explains Brownian motion

Brownian motion

Brownian motion or pedesis is the presumably random drifting of particles suspended in a fluid or the mathematical model used to describe such random movements, which is often called a particle theory.The mathematical model of Brownian motion has several real-world applications...

in a way that definitively proves atomic theory.

1907:Leo Hendrik Baekeland invents bakelite, one of the first commercially successful plastic

Plastic

A plastic material is any of a wide range of synthetic or semi-synthetic organic solids used in the manufacture of industrial products. Plastics are typically polymers of high molecular mass, and may contain other substances to improve performance and/or reduce production costs...

s.

Robert Millikan

Robert A. Millikan was an American experimental physicist, and Nobel laureate in physics for his measurement of the charge on the electron and for his work on the photoelectric effect. He served as president of Caltech from 1921 to 1945...

measures the charge of individual electrons with unprecedented accuracy through the oil drop experiment, confirming that all electrons have the same charge and mass.

1909:S. P. L. Sørensen

S. P. L. Sørensen

Søren Peder Lauritz Sørensen was a Danish chemist, famous for the introduction of the concept of pH, a scale for measuring acidity and basicity. He was born in Havrebjerg, Denmark....

invents the pH

PH

In chemistry, pH is a measure of the acidity or basicity of an aqueous solution. Pure water is said to be neutral, with a pH close to 7.0 at . Solutions with a pH less than 7 are said to be acidic and solutions with a pH greater than 7 are basic or alkaline...

concept and develops methods for measuring acidity.

1911:Antonius Van den Broek

Antonius Van den Broek

Antonius Johannes van den Broek was a Dutch amateur physicist notable for being the first who realized that the number of an element in the periodic table corresponds to the charge of its atomic nucleus....

proposes the idea that the elements on the periodic table are more properly organized by positive nuclear charge rather than atomic weight.

1911:The first Solvay Conference

Solvay Conference

The International Solvay Institutes for Physics and Chemistry, located in Brussels, were founded by the Belgian industrialist Ernest Solvay in 1912, following the historic invitation-only 1911 Conseil Solvay, the turning point in world physics...

is held in Brussels

Brussels

Brussels , officially the Brussels Region or Brussels-Capital Region , is the capital of Belgium and the de facto capital of the European Union...

, bringing together most of the most prominent scientists of the day. Conferences in physics and chemistry continue to be held periodically to this day.

1911:Ernest Rutherford, Hans Geiger, and Ernest Marsden

Ernest Marsden

Sir Ernest Marsden was an English-New Zealand physicist. He was born in East Lancashire, living in Rishton and educated at Queen Elizabeth's Grammar School, Blackburn, where an inter-house trophy rewarding academic excellence bears his name.He met Ernest Rutherford at the University of Manchester...

perform the Gold foil experiment

Geiger-Marsden experiment

The Geiger–Marsden experiment was an experiment to probe the structure of the atom performed by Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden in 1909, under the direction of Ernest Rutherford at the Physical Laboratories of the University of Manchester...

, which proves the nuclear model of the atom, with a small, dense, positive nucleus surrounded by a diffuse electron cloud.

1912:William Henry Bragg

William Henry Bragg