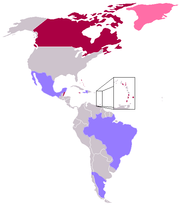

Monarchies in the Americas

Encyclopedia

Self-governance

Self-governance is an abstract concept that refers to several scales of organization.It may refer to personal conduct or family units but more commonly refers to larger scale activities, i.e., professions, industry bodies, religions and political units , up to and including autonomous regions and...

states and territories in North

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

and South America

South America

South America is a continent situated in the Western Hemisphere, mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere. The continent is also considered a subcontinent of the Americas. It is bordered on the west by the Pacific Ocean and on the north and east...

where supreme power resides with an individual, who is recognised as the head of state

Head of State

A head of state is the individual that serves as the chief public representative of a monarchy, republic, federation, commonwealth or other kind of state. His or her role generally includes legitimizing the state and exercising the political powers, functions, and duties granted to the head of...

. Each is a constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy is a form of government in which a monarch acts as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, whether it be a written, uncodified or blended constitution...

, wherein the sovereign inherits his or her office, usually keeps it until death or abdication

Abdication

Abdication occurs when a monarch, such as a king or emperor, renounces his office.-Terminology:The word abdication comes derives from the Latin abdicatio. meaning to disown or renounce...

, and is bound by laws and customs in the exercise of their powers. Ten of these monarchies are independent states, and equally share Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom

Elizabeth II is the constitutional monarch of 16 sovereign states known as the Commonwealth realms: the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Jamaica, Barbados, the Bahamas, Grenada, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Belize,...

– who resides primarily in the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

– as their respective sovereign, making them part of a global grouping known informally as the Commonwealth realm

Commonwealth Realm

A Commonwealth realm is a sovereign state within the Commonwealth of Nations that has Elizabeth II as its monarch and head of state. The sixteen current realms have a combined land area of 18.8 million km² , and a population of 134 million, of which all, except about two million, live in the six...

s, while the remaining three are dependencies

Dependent territory

A dependent territory, dependent area or dependency is a territory that does not possess full political independence or sovereignty as a State, and remains politically outside of the controlling state's integral area....

of European monarchies. As such, none of the monarchies in the Americas has a resident monarch.

These crowns continue a history of monarchy in the Americas that reaches back to before European colonisation

European colonization of the Americas

The start of the European colonization of the Americas is typically dated to 1492. The first Europeans to reach the Americas were the Vikings during the 11th century, who established several colonies in Greenland and one short-lived settlement in present day Newfoundland...

. Both tribal and more complex pre-Columbian

Pre-Columbian

The pre-Columbian era incorporates all period subdivisions in the history and prehistory of the Americas before the appearance of significant European influences on the American continents, spanning the time of the original settlement in the Upper Paleolithic period to European colonization during...

societies existed under monarchical forms of government, with some expanding to form vast empire

Empire

The term empire derives from the Latin imperium . Politically, an empire is a geographically extensive group of states and peoples united and ruled either by a monarch or an oligarchy....

s under a central king

Monarch

A monarch is the person who heads a monarchy. This is a form of government in which a state or polity is ruled or controlled by an individual who typically inherits the throne by birth and occasionally rules for life or until abdication...

figure, while others did the same with a decentralised collection of tribal regions under a hereditary chieftain

Tribal chief

A tribal chief is the leader of a tribal society or chiefdom. Tribal societies with social stratification under a single leader emerged in the Neolithic period out of earlier tribal structures with little stratification, and they remained prevalent throughout the Iron Age.In the case of ...

. None of the contemporary monarchies, however, are descended from those pre-colonial royal systems, instead either having their historical roots in, or still being a part of, the current European monarchies that spread their reach across the Atlantic Ocean

Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's oceanic divisions. With a total area of about , it covers approximately 20% of the Earth's surface and about 26% of its water surface area...

, beginning in the mid 14th century.

From that date on, through the Age of Discovery

Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery, also known as the Age of Exploration and the Great Navigations , was a period in history starting in the early 15th century and continuing into the early 17th century during which Europeans engaged in intensive exploration of the world, establishing direct contacts with...

, European colonisation brought extensive American territory under the control of Europe's monarchs, though the majority of these colonies subsequently gained independence from their rulers. Some did so via armed conflict with their mother countries, as in the American Revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

and the Latin American wars of independence, usually severing all ties to the overseas monarchies in the process. Others gained full sovereignty by legislative paths, such as Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

's patriation

Patriation

Patriation is a non-legal term used in Canada to describe a process of constitutional change also known as "homecoming" of the constitution. Up until 1982, Canada was governed by a constitution that was a British law and could be changed only by an Act of the British Parliament...

of its constitution from the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

. A certain number of former colonies became republic

Republic

A republic is a form of government in which the people, or some significant portion of them, have supreme control over the government and where offices of state are elected or chosen by elected people. In modern times, a common simplified definition of a republic is a government where the head of...

s immediately upon achieving self-governance. The remainder continued with endemic constitutional monarchies– in the cases of Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

, Brazil

Brazil

Brazil , officially the Federative Republic of Brazil , is the largest country in South America. It is the world's fifth largest country, both by geographical area and by population with over 192 million people...

, and Haiti

Haiti

Haiti , officially the Republic of Haiti , is a Caribbean country. It occupies the western, smaller portion of the island of Hispaniola, in the Greater Antillean archipelago, which it shares with the Dominican Republic. Ayiti was the indigenous Taíno or Amerindian name for the island...

– with their own resident monarch, and for places such as Canada and some island states in the Caribbean

Caribbean

The Caribbean is a crescent-shaped group of islands more than 2,000 miles long separating the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, to the west and south, from the Atlantic Ocean, to the east and north...

sharing their monarch with their former metropole

Metropole

The metropole, from the Greek Metropolis 'mother city' was the name given to the British metropolitan centre of the British Empire, i.e. the United Kingdom itself...

, the most recently created being that of Belize

Monarchy of Belize

The monarchy of Belize is a system of government in which a hereditary monarch is the sovereign of Belize, holding the position of head of state; the incumbent is Elizabeth II, officially called Queen of Belize, who has reigned since September 21, 1981...

in 1981. There is currently no major campaign to abolish the monarchy in any of the ten states, although there is a minority of republicans in some.

American monarchies

While the one monarch of each of the American monarchies resides predominantly in Europe, each of the states are sovereignSovereignty

Sovereignty is the quality of having supreme, independent authority over a geographic area, such as a territory. It can be found in a power to rule and make law that rests on a political fact for which no purely legal explanation can be provided...

, and thus have distinct local monarchies seated

Seat (legal entity)

In strict legal language, the term seat defines the seat of a corporation or organisation as a legal entity, indicating where the headquarters of this entity are located...

in their respective capitals, with the monarch's day-to-day governmental and ceremonial duties generally carried out by an appointed local viceroy

Viceroy

A viceroy is a royal official who runs a country, colony, or province in the name of and as representative of the monarch. The term derives from the Latin prefix vice-, meaning "in the place of" and the French word roi, meaning king. A viceroy's province or larger territory is called a viceroyalty...

.

Antigua and Barbuda

The monarchy of Antigua and BarbudaAntigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda is a twin-island nation lying between the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. It consists of two major inhabited islands, Antigua and Barbuda, and a number of smaller islands...

has its roots in the Spanish monarchy, under the authority of which the islands were first colonised in the late 15th century, and later the British monarchy

Monarchy of the United Kingdom

The monarchy of the United Kingdom is the constitutional monarchy of the United Kingdom and its overseas territories. The present monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, has reigned since 6 February 1952. She and her immediate family undertake various official, ceremonial and representational duties...

, as a Crown colony

Crown colony

A Crown colony, also known in the 17th century as royal colony, was a type of colonial administration of the English and later British Empire....

. On 10 June 1973, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Antigua and Barbuda. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Antigua and Barbuda, presently Dame Louise Lake-Tack

Louise Lake-Tack

Dame Louise Agnetha Lake-Tack, GCMG, DStJ is the current Governor-General of Antigua and Barbuda.-Background and earlier career:...

.

Elizabeth and her royal consort

Prince consort

A prince consort is the husband of a queen regnant who is not himself a king in his own right.Current examples include the Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh , and Prince Henrik of Denmark .In recognition of his status, a prince consort may be given a formal...

, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh is the husband of Elizabeth II. He is the United Kingdom's longest-serving consort and the oldest serving spouse of a reigning British monarch....

, included Antigua and Barbuda in their 1966 Caribbean

Caribbean

The Caribbean is a crescent-shaped group of islands more than 2,000 miles long separating the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, to the west and south, from the Atlantic Ocean, to the east and north...

tour, and again in the Queen's Silver Jubilee

Silver Jubilee of Elizabeth II

The Silver Jubilee of Elizabeth II marked the 25th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II's accession to the throne of the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and other Commonwealth realms...

tour of October 1977. Elizabeth returned once more in 1985. For the country's 25th anniversary of independence, on 30 October 2006, Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex

Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex

Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex KG GCVO is the third son and fourth child of Elizabeth II and The Duke of Edinburgh...

, opened Antigua and Barbuda's new parliament building, reading a message from his mother, the Queen. HRH The Duke of York visited Antigua and Barbuda in January 2001.

The Bahamas

The monarchy of The BahamasThe Bahamas

The Bahamas , officially the Commonwealth of the Bahamas, is a nation consisting of 29 islands, 661 cays, and 2,387 islets . It is located in the Atlantic Ocean north of Cuba and Hispaniola , northwest of the Turks and Caicos Islands, and southeast of the United States...

has its roots in the Spanish monarchy, under the authority of which the islands were first colonised in the late 15th century, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony, after 1717. On 10 July 1973, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly formed monarchy of The Bahamas. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of the Bahamas, presently Sir Arthur Foulkes

Arthur Foulkes

Sir Arthur Alexander Foulkes, GCMG is the Governor-General of the Bahamas.Foulkes was elected to the House of Assembly in 1967 and served in the government of Lynden Pindling as Minister of Communications and Minister of Tourism...

.

Barbados

The monarchy of Barbados has its roots in the English monarchy, under the authority of which the island was claimed in 1625 and first colonised in 1627, and later the British monarchy. By the 18th century, Barbados became one of the main seats of the British Crown's authority in the British West IndiesBritish West Indies

The British West Indies was a term used to describe the islands in and around the Caribbean that were part of the British Empire The term was sometimes used to include British Honduras and British Guiana, even though these territories are not geographically part of the Caribbean...

, and then, after an attempt in 1958 at a federation with other West Indian colonies

West Indies Federation

The West Indies Federation, also known as the Federation of the West Indies, was a short-lived Caribbean federation that existed from January 3, 1958, to May 31, 1962. It consisted of several Caribbean colonies of the United Kingdom...

, continued as a self-governing colony

Self-governing colony

A self-governing colony is a colony with an elected legislature, in which politicians are able to make most decisions without reference to the colonial power with formal or nominal control of the colony...

until, on 30 November 1966, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly formed monarchy of Barbados. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Barbados, who for the past fifteen years has been Sir Clifford Husbands

Clifford Husbands

Sir Clifford Straughn Husbands, GCMG, KA, QC was the Governor-General of Barbados. He held this office from 1996, when he was appointed after the death of Dame Nita Barrow, until he retired on 31 October 2011.-External links:*...

. On 31 October 2011 Sir Clifford stepped down due to retirement. On 1 November 2011 Eliot Belgrove was selected to be Barbados' acting Governor-General.

In 1966, Elizabeth's cousin, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

Prince Edward, Duke of Kent

The Duke of Kent graduated from the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst on 29 July 1955 as a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Scots Greys, the beginning of a military career that would last over 20 years. He was promoted to captain on 29 July 1961. The Duke of Kent saw service in Hong Kong from 1962–63...

, opened the second session of the first parliament of the newly established country, before the Queen herself, along with Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, toured Barbados. Elizabeth returned for her Silver Jubilee in 1977, and again in 1989, to mark the 350th anniversary of the establishment of the Barbadian parliament.

Former Prime Minister

Prime Minister of Barbados

The Prime Minister of Barbados is a very influential position as head of government of Barbados. According to Barbados Constitution, the Prime Minister must always be a member of Parliament, and is appointed by the Governor-General who is responsible for conducting parliamentary elections, and for...

Owen Arthur

Owen Arthur

Owen Seymour Arthur, MP was the fifth Prime Minister of Barbados who was in office from 1994 to 2008 and is the current Leader of Opposition in Barbados. To date, he is the longest serving Barbadian Prime Minister....

called for a referendum on Barbados becoming a republic to be held in 2005, though the vote was then pushed back to "at least 2006" in order to speed up Barbados' integration in the CARICOM Single Market and Economy

CARICOM Single Market and Economy

The CARICOM Single Market and Economy, also known as the Caribbean Single Market and Economy , is an integrated development strategy envisioned at the 10th Meeting of the Conference of Heads of Government of the Caribbean Community which took place in July 1989 in Grand Anse, Grenada...

. It was announced on 26 November 2007 that the referendum

Barbadian republic referendum

-History:In 1979, a commission of inquiry known as the Cox Commission on the Constitution was constituted and under the auspices of looking at the republic issue. The Cox Commission came to the conclusion that Barbadians preferred to maintain the constitutional monarchy. The proposal to move to a...

would be held in 2008, together with the general election that year

Barbadian general election, 2008

A general election was held in Barbados on 15 January 2008. A concurrent referendum to determine whether or not to become a republic was initially planned but that vote was postponed....

. The vote was, however, postponed again to a later point, due to administrative concerns.

Belize

Belize was, until the 15th century, a part of the Mayan EmpireMaya civilization

The Maya is a Mesoamerican civilization, noted for the only known fully developed written language of the pre-Columbian Americas, as well as for its art, architecture, and mathematical and astronomical systems. Initially established during the Pre-Classic period The Maya is a Mesoamerican...

, containing smaller states headed by a hereditary ruler known as an ajaw

Ajaw

Ajaw is a political rulership title attested from the epigraphic inscriptions of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization, with a meaning variously interpreted as "lord", "ruler", "king" or "leader". It denoted any of the leading class of nobles in a particular polity and was not limited to a single...

(later k’uhul ajaw). The present monarchy of Belize has its roots in the Spanish monarchy, under the authority of which the area was first colonised in the 16th century, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 21 September 1981, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly formed monarchy of Belize. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Belize, presently Sir Colville Young

Colville Young

Sir Colville Norbert Young, GCMG, MBE is the Governor General of Belize, and also patron of the Scout Association of Belize. He was appointed Governor-General in 1993, taking office on 17 November of that year, and was knighted in 1994....

.

Canada

Aboriginal peoples in Canada

Aboriginal peoples in Canada comprise the First Nations, Inuit and Métis. The descriptors "Indian" and "Eskimo" have fallen into disuse in Canada and are commonly considered pejorative....

had systems of governance organised in a fashion similar to the Occidental

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West and the Occident , is a term referring to the countries of Western Europe , the countries of the Americas, as well all countries of Northern and Central Europe, Australia and New Zealand...

concept of monarchy; European explorers often referred to hereditary leaders of tribes as kings. The present monarchy of Canada has its roots in the French and English monarchies, under the authority of which the area was colonised in the 16th-18th centuries, and later the British monarchy. The country became a self-governing federation on 1 July 1867, recognised as a kingdom in its own right, but did not have full legislative autonomy from the British Crown until the passage of the Statute of Westminster

Statute of Westminster 1931

The Statute of Westminster 1931 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Passed on 11 December 1931, the Act established legislative equality for the self-governing dominions of the British Empire with the United Kingdom...

on 11 December 1931, retaining the then reigning monarch, George V

George V of the United Kingdom

George V was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 through the First World War until his death in 1936....

, as monarch of the newly formed monarchy of Canada. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor General of Canada

Governor General of Canada

The Governor General of Canada is the federal viceregal representative of the Canadian monarch, Queen Elizabeth II...

, presently David Lloyd Johnston

David Lloyd Johnston

David Lloyd Johnston is a Canadian academic, author and statesman who is the current Governor General of Canada, the 28th since Canadian Confederation....

, and in each of the provinces by a lieutenant governor.

Grenada

The monarchy of GrenadaGrenada

Grenada is an island country and Commonwealth Realm consisting of the island of Grenada and six smaller islands at the southern end of the Grenadines in the southeastern Caribbean Sea...

has its roots in the French monarchy, under the authority of which the islands were first colonised in the mid 17th century, and later the English and then British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 7 February 1974, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Grenada. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Grenada, presently Carlyle Glean

Carlyle Glean

Sir Carlyle Arnold Glean, GCMG is a Grenadian politician, currently serving as Governor-General of Grenada. He was the Minister of Education in the government of Nicholas Brathwaite from 1990 to 1995, after which he retired from politics. He was appointed Governor-General in November...

.

Jamaica

Jamaica

Jamaica is an island nation of the Greater Antilles, in length, up to in width and 10,990 square kilometres in area. It is situated in the Caribbean Sea, about south of Cuba, and west of Hispaniola, the island harbouring the nation-states Haiti and the Dominican Republic...

has its roots in the Spanish monarchy, under the authority of which the islands were first colonised in the late 16th century, and later the English and then British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 6 August 1962, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Jamaica. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Jamaica

Governor-General of Jamaica

The Governor-General of Jamaica represents the Jamaican monarch, and head of state, who holds the title of King or Queen of Jamaica ....

, presently Sir Patrick Allen (Jamaica).

In 1966, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, accompanied by his son, Charles, Prince of Wales

Charles, Prince of Wales

Prince Charles, Prince of Wales is the heir apparent and eldest son of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. Since 1958 his major title has been His Royal Highness The Prince of Wales. In Scotland he is additionally known as The Duke of Rothesay...

, toured Jamaica as part of his visit to open that year's Commonwealth Games

1966 British Empire and Commonwealth Games

The 1966 British Empire and Commonwealth Games were held in Kingston, Jamaica from 4 August to 13 August 1966. This was the first time that the Games had been held outside the so-called White Dominions....

. The Queen herself visited Jamaica in 2002; despite some republican sentiments in the country, she was enthusiastically welcomed. However, in September of the following year, the former Prime Minister of Jamaica

Prime Minister of Jamaica

The Prime Minister of Jamaica is Jamaica's head of government, currently Andrew Holness. Andrew Holness was elected as the new leader of the governing Jamaica Labour Party and succeeded Bruce Golding to become Jamaica's ninth Prime Minister on 23 October 2011...

, P.J. Patterson, advocated making Jamaica into a republic

Republic

A republic is a form of government in which the people, or some significant portion of them, have supreme control over the government and where offices of state are elected or chosen by elected people. In modern times, a common simplified definition of a republic is a government where the head of...

by 2007.

Saint Kitts and Nevis

The monarchy of Saint Kitts and NevisSaint Kitts and Nevis

The Federation of Saint Kitts and Nevis , located in the Leeward Islands, is a federal two-island nation in the West Indies. It is the smallest sovereign state in the Americas, in both area and population....

has its roots in the English and French monarchies, under the authority of which the islands were first colonised in the early 17th century, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 10 June 1973, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Antigua and Barbuda. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Saint Kitts and Nevis, presently Sir Cuthbert Sebastian

Cuthbert Sebastian

Sir Cuthbert Montraville Sebastian, GCMG, OBE , is the Governor-General of St. Kitts and Nevis. He was appointed Governor-General in 1995 and was sworn in on 1 January 1996....

.

Saint Lucia

The Caribs who occupied the island of Saint LuciaSaint Lucia

Saint Lucia is an island country in the eastern Caribbean Sea on the boundary with the Atlantic Ocean. Part of the Lesser Antilles, it is located north/northeast of the island of Saint Vincent, northwest of Barbados and south of Martinique. It covers a land area of 620 km2 and has an...

in pre-Columbian times had a complex society, with hereditary kings and shamans. The present monarchy has its roots in the Dutch

Monarchy of the Netherlands

The Netherlands has been an independent monarchy since 16 March 1815, and has been governed by members of the House of Orange-Nassau since.-Constitutional role and position of the monarch:...

, French, and English monarchies, under the authority of which the island was first colonised in 1605, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 22 February 1979, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Saint Lucia. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Saint Lucia, presently Dame Pearlette Louisy

Pearlette Louisy

Dame Pearlette Louisy, GCMG is the Governor-General of Saint Lucia. She is the first woman to hold this office, which she was sworn into on 19 September 1997....

.

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

The present monarchy of Saint Vincent and the GrenadinesSaint Vincent and the Grenadines

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines is an island country in the Lesser Antilles chain, namely in the southern portion of the Windward Islands, which lie at the southern end of the eastern border of the Caribbean Sea where the latter meets the Atlantic Ocean....

has its roots in the French monarchy, under the authority of which the island was first colonised in 1719, and later the British monarchy, as a Crown colony. On 27 October 1979, the country gained independence from the United Kingdom, retaining the then reigning monarch, Elizabeth II, as monarch of the newly created monarchy of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. The monarch is represented in the country by the Governor-General of Vincent and the Grenadines, presently Sir Frederick Ballantyne

Frederick Ballantyne

Sir Frederick Nathaniel Ballantyne, GCMG is the Governor-General of St. Vincent and the Grenadines. He has been in this office since 2 September 2002, and was knighted in November. He replaced Monica Dacon who had been interim Governor General after the death of Charles Antrobus.-External links:*...

.

Denmark

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous country within the Kingdom of Denmark, located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Though physiographically a part of the continent of North America, Greenland has been politically and culturally associated with Europe for...

is one of the three constituent countries

Constituent country

Constituent country is a phrase sometimes used in contexts in which a country makes up a part of a larger entity. The term constituent country does not have any defined legal meaning, and is used simply to refer to a country which is a part Constituent country is a phrase sometimes used in contexts...

of the Kingdom of Denmark

Kingdom of Denmark

The Kingdom of Denmark or the Danish Realm , is a constitutional monarchy and sovereign state consisting of Denmark proper in northern Europe and two autonomous constituent countries, the Faroe Islands in the North Atlantic and Greenland in North America. Denmark is the hegemonial part, where the...

, with Queen Margrethe II

Margrethe II of Denmark

Margrethe II is the Queen regnant of the Kingdom of Denmark. In 1972 she became the first female monarch of Denmark since Margaret I, ruler of the Scandinavian countries in 1375-1412 during the Kalmar Union.-Early life:...

as the reigning sovereign. The territory first came under monarchical rule in 1261, when the populace accepted the overlordship of the King of Norway; by 1360, Norway had entered into a personal union

Personal union

A personal union is the combination by which two or more different states have the same monarch while their boundaries, their laws and their interests remain distinct. It should not be confused with a federation which is internationally considered a single state...

with the Kingdom of Denmark, which became more entrenched with the union of the kingdoms into Denmark–Norway

Denmark–Norway

Denmark–Norway is the historiographical name for a former political entity consisting of the kingdoms of Denmark and Norway, including the originally Norwegian dependencies of Iceland, Greenland and the Faroe Islands...

in 1536. After the dissolution of this arrangement in 1814, Greenland remained as a Danish colony, and, after its role in World War II

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

, was granted its special status within the Kingdom of Denmark in 1953. The monarch is represented in the territory by the Rigsombudsmand (High Commissioner

High Commissioner

High Commissioner is the title of various high-ranking, special executive positions held by a commission of appointment.The English term is also used to render various equivalent titles in other languages.-Bilateral diplomacy:...

), presently Mikaela Engell

Mikaela Engell

Mikaela Engell is the current Danish High Commissioner of Greenland, a post she has held since April 1, 2011. Previously she had work in the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs as first a Permanent Secretary and later as a counsellor. As High Commisoner she ex-officio holds the post as a member of...

.

Netherlands

ArubaAruba

Aruba is a 33 km-long island of the Lesser Antilles in the southern Caribbean Sea, located 27 km north of the coast of Venezuela and 130 km east of Guajira Peninsula...

, Curaçao

Curaçao

Curaçao is an island in the southern Caribbean Sea, off the Venezuelan coast. The Country of Curaçao , which includes the main island plus the small, uninhabited island of Klein Curaçao , is a constituent country of the Kingdom of the Netherlands...

and Sint Maarten are constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Netherlands

Kingdom of the Netherlands

The Kingdom of the Netherlands is a sovereign state and constitutional monarchy with territory in Western Europe and in the Caribbean. The four parts of the Kingdom—Aruba, Curaçao, the Netherlands, and Sint Maarten—are referred to as "countries", and participate on a basis of equality...

, and thus have Queen Beatrix

Beatrix of the Netherlands

Beatrix is the Queen regnant of the Kingdom of the Netherlands comprising the Netherlands, Curaçao, Sint Maarten, and Aruba. She is the first daughter of Queen Juliana of the Netherlands and Prince Bernhard of Lippe-Biesterfeld. She studied law at Leiden University...

as their sovereign, as well as the remaining islands forming the Caribbean Netherlands. Aruba was first settled under the authority of the Spanish Crown circa 1499, but was acquired by the Dutch in 1634, under whose control the island has remained, save for an interval between 1805 and 1816, when Aruba was captured by the Royal Navy

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy is the naval warfare service branch of the British Armed Forces. Founded in the 16th century, it is the oldest service branch and is known as the Senior Service...

of King George III

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

. The former Netherlands Antilles

Netherlands Antilles

The Netherlands Antilles , also referred to informally as the Dutch Antilles, was an autonomous Caribbean country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, consisting of two groups of islands in the Lesser Antilles: Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao , in Leeward Antilles just off the Venezuelan coast; and Sint...

were originally discovered by explorers sent in the 1490s by the King of Spain, but were eventually conquered by the Dutch West India Company

Dutch West India Company

Dutch West India Company was a chartered company of Dutch merchants. Among its founding fathers was Willem Usselincx...

in the 17th century, whereafter the islands remained under the control of the Dutch Crown as colonial territories. The Netherlands Antilles achieved the status of an autonomous country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1954, from which Aruba was split in 1986 as a separate constituent country of the larger kingdom. The former Netherlands Antilles again split as three areas in 2010. The monarch is represented in each region by the Governor of Aruba

Governor of Aruba

The Governor of Aruba is the representative on Aruba of the Dutch head of state . The governors duties are twofold: he represents and guards the general interests of the Kingdom and is head of the Aruban Government. He is accountable to the Government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. As the head...

, presently Fredis Refunjol

Fredis Refunjol

Fredis Jose Refunjol is an Aruban politician serving as the current Governor of Aruba. Originally a teacher, he has served as a government official for the past twenty years, starting as a Member of the Estates of Aruba....

, the Governor of Curaçao

Governor of Curaçao

The Governor of Curaçao is the representative on Curaçao of the Dutch head of state . The governor's duties are twofold: he represents and guards the general interests of the Kingdom and is head of the government of Curaçao. He is accountable to the government of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. As...

, presently Frits Goedgedrag

Frits Goedgedrag

Frits M. de los Santos Goedgedrag is the current and first Governor of Curaçao. From 1 July 2002 to 9 October 2010, Goedgedrag was the Governor of the Netherlands Antilles. From 1992 to 1998, he was Administrator of Bonaire....

, and the Governor of Sint Maarten

Governor of Sint Maarten

The Governor of Sint Maarten is the representative on Sint Maarten of the Dutch head of state . The governors duties are twofold: he represents and guards the general interests of the Kingdom and is head of the government of Sint Maarten. He is accountable to the government of the Kingdom of the...

, presently Eugene Holiday

Eugene Holiday

Eugene Holiday is the first Governor of Sint Maarten, which became an constituent country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands on 10 October 2010. He was installed by the Council of Ministers of the Kingdom of the Netherlands on 7 September 2010. He was president of Princess Juliana International...

.

United Kingdom

The British CrownMonarchy of the United Kingdom

The monarchy of the United Kingdom is the constitutional monarchy of the United Kingdom and its overseas territories. The present monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, has reigned since 6 February 1952. She and her immediate family undertake various official, ceremonial and representational duties...

possesses a number of overseas territories

British overseas territories

The British Overseas Territories are fourteen territories of the United Kingdom which, although they do not form part of the United Kingdom itself, fall under its jurisdiction. They are remnants of the British Empire that have not acquired independence or have voted to remain British territories...

in the Americas, for whom Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom

Elizabeth II is the constitutional monarch of 16 sovereign states known as the Commonwealth realms: the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Jamaica, Barbados, the Bahamas, Grenada, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Tuvalu, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Belize,...

is monarch. In North America are Anguilla

Anguilla

Anguilla is a British overseas territory and overseas territory of the European Union in the Caribbean. It is one of the most northerly of the Leeward Islands in the Lesser Antilles, lying east of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands and directly north of Saint Martin...

, Bermuda

Bermuda

Bermuda is a British overseas territory in the North Atlantic Ocean. Located off the east coast of the United States, its nearest landmass is Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, about to the west-northwest. It is about south of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, and northeast of Miami, Florida...

, the British Virgin Islands

British Virgin Islands

The Virgin Islands, often called the British Virgin Islands , is a British overseas territory and overseas territory of the European Union, located in the Caribbean to the east of Puerto Rico. The islands make up part of the Virgin Islands archipelago, the remaining islands constituting the U.S...

, the Cayman Islands

Cayman Islands

The Cayman Islands is a British Overseas Territory and overseas territory of the European Union located in the western Caribbean Sea. The territory comprises the three islands of Grand Cayman, Cayman Brac, and Little Cayman, located south of Cuba and northwest of Jamaica...

, Montserrat

Montserrat

Montserrat is a British overseas territory located in the Leeward Islands, part of the chain of islands called the Lesser Antilles in the West Indies. This island measures approximately long and wide, giving of coastline...

, and the Turks and Caicos Islands

Turks and Caicos Islands

The Turks and Caicos Islands are a British Overseas Territory and overseas territory of the European Union consisting of two groups of tropical islands in the Caribbean, the larger Caicos Islands and the smaller Turks Islands, known for tourism and as an offshore financial centre.The Turks and...

, while the Falkland Islands

Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands are an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean, located about from the coast of mainland South America. The archipelago consists of East Falkland, West Falkland and 776 lesser islands. The capital, Stanley, is on East Falkland...

, and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands is a British overseas territory and overseas territory of the European Union in the southern Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote and inhospitable collection of islands, consisting of South Georgia and a chain of smaller islands, known as the South Sandwich...

are located in South America. The Caribbean

Caribbean

The Caribbean is a crescent-shaped group of islands more than 2,000 miles long separating the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea, to the west and south, from the Atlantic Ocean, to the east and north...

islands were colonised under the authority or the direct instruction of a number of European monarchs, mostly English, Dutch

Monarchy of the Netherlands

The Netherlands has been an independent monarchy since 16 March 1815, and has been governed by members of the House of Orange-Nassau since.-Constitutional role and position of the monarch:...

, or Spanish, throughout the first half of the 17th century. By 1681, however, when the Turks and Caicos Islands were settled by Britons, all of the above mentioned islands were under the control of Charles II of England, Scotland, France and Ireland

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

. Colonies were merged and split through various reorganizations of the Crown's Caribbean regions, until 19 December 1980, the date that Anguilla became a British Crown territory in its own right. The monarch is represented in these jurisdictions by: the Governor of Anguilla

Governor of Anguilla

The Governor of Anguilla is the representative of the British monarch in the United Kingdom's overseas territory of Anguilla. The Governor is appointed by the monarch on the advice of the British government...

, presently Andrew George

Andrew George (governor)

Andrew Neil George is a British diplomat. George served as the Governor and Commander-in-Chief of Anguilla from July 2006 to March 2009...

; the Governor of Bermuda

Governor of Bermuda

The Governor of Bermuda is the representative of the British monarch in the British overseas territory of Bermuda. The Governor is appointed by the monarch on the advice of the British government...

, presently Richard Gozney

Richard Gozney

Sir Richard Hugh Turton Gozney KCMG CVO KStJ is a British career diplomat. He has been Governor and Commander in Chief of Bermuda since 12 December 2007.-Background and education:...

; the Governor of the British Virgin Islands

Governor of the British Virgin Islands

The Governor of the British Virgin Islands is the representative of the British monarch in the United Kingdom's overseas territory of British Virgin Islands. The Governor is appointed by the monarch on the advice of the British government...

, presently David Pearey

David Pearey

David Pearey was the Governor of the British Virgin Islands from 18 April 2006 to 5 August 2010. He was appointed by Queen Elizabeth II on the advice of the British government, to represent the Queen in the territory, and to act as the de facto head of state.Prior to his appointment as Governor,...

; the Governor of the Cayman Islands

Governor of the Cayman Islands

The Governor of the Cayman Islands is the representative of the British monarch in the United Kingdom's overseas territory of the Cayman Islands. The Governor is appointed by the monarch on the advice of the British government...

, presently Stuart Jack

Stuart Jack

Stuart Duncan Macdonald Jack, CVO is a British diplomat and a former Governor of the Cayman Islands. He joined the United Kingdom Foreign and Commonwealth Office in 1972...

; the Governor of Montserrat

Governor of Montserrat

The Governor of Montserrat is the representative of the British monarch in the United Kingdom's overseas territory of Montserrat. The Governor is appointed by the monarch on the advice of the British government...

, presently Adrian Davis

Adrian Davis (governor)

Adrian Derek Davis is a British economist and civil servant, and is the current Governor of Montserrat.Since 1989 he has worked for the Department for International Development, and before that its predecessor, the Overseas Development Administration....

; and the Governor of the Turks and Caicos Islands

Governor of the Turks and Caicos Islands

The Governor of the Turks and Caicos Islands is the representative of the British monarch in the United Kingdom's overseas territory of Turks and Caicos Islands. The Governor is appointed by the monarch on the advice of the British government...

, presently Ric Todd.

The Falkland Islands, off the south coast of Argentina

Argentina

Argentina , officially the Argentine Republic , is the second largest country in South America by land area, after Brazil. It is constituted as a federation of 23 provinces and an autonomous city, Buenos Aires...

, were simultaneously claimed for Louis XV of France

Louis XV of France

Louis XV was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and of Navarre from 1 September 1715 until his death. He succeeded his great-grandfather at the age of five, his first cousin Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, served as Regent of the kingdom until Louis's majority in 1723...

, in 1764, and George III of the United Kingdom

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

, in 1765, though the French colony was ceded to Charles III of Spain

Charles III of Spain

Charles III was the King of Spain and the Spanish Indies from 1759 to 1788. He was the eldest son of Philip V of Spain and his second wife, the Princess Elisabeth Farnese...

in 1767. By 1833, however, the islands were under full British control. The South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands were discovered by Captain James Cook

James Cook

Captain James Cook, FRS, RN was a British explorer, navigator and cartographer who ultimately rose to the rank of captain in the Royal Navy...

for George III in January 1775, and from 1843 were governed by the British Crown-in-Council through the Falkland Islands, an arrangement that stood until the South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands were incorporated as a distinct British overseas territory in 1985. The monarch is represented in these regions by Nigel Haywood

Nigel Haywood

Nigel Robert Haywood CVO is a British diplomat, the former British ambassador to Estonia and the current Governor of the Falkland Islands....

, who is both the Governor of the Falkland Islands

Governor of the Falkland Islands

The Governor of the Falkland Islands is the representative of the British Crown in the Falkland Islands, acting "in Her Majesty's name and on Her Majesty's behalf" as the islands' de facto head of state in the absence of the British monarch...

and the Commissioner for South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

Commissioner for South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

The Commissioner for South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands is the representative of the British monarch in the United Kingdom's overseas territory of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands...

.

Succession laws

Primogeniture

Primogeniture is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn to inherit the entire estate, to the exclusion of younger siblings . Historically, the term implied male primogeniture, to the exclusion of females...

. Most states and regions, including those Commonwealth realms in the Americas, as well as those American territories under the British crown, adhere to male primogeniture, whereby sons have precedence over daughters in the order of succession. For the Commonwealth realms, this line is governed by provisions of the Act of Settlement

Act of Settlement 1701

The Act of Settlement is an act of the Parliament of England that was passed in 1701 to settle the succession to the English throne on the Electress Sophia of Hanover and her Protestant heirs. The act was later extended to Scotland, as a result of the Treaty of Union , enacted in the Acts of Union...

and the English Bill of Rights, whether by willing deference to the act as a British statute or as a patriated

Patriation

Patriation is a non-legal term used in Canada to describe a process of constitutional change also known as "homecoming" of the constitution. Up until 1982, Canada was governed by a constitution that was a British law and could be changed only by an Act of the British Parliament...

part of the particular realm's constitution. Those possessions under the Danish and Dutch crowns adhere to equal primogeniture, whereby the eldest child inherits the throne, regardless of gender.

Suggestions of change have been raised in the Commonwealth realms in regards to the order of succession; however, as these states share one monarch with other countries, all with legislative independence and/or independent regulations regarding the order of succession, any change would have to be made simultaneously in all of the Commonwealth realms to maintain the shared monarchy. With no imminent need for change– with males in the first four places in the line of succession– proposals are repeatedly postponed to a later time. For Greenland, however, the 2005 elected

Danish parliamentary election, 2005

Parliamentary elections were held in Denmark on 8 February 2005. Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen's Venstre retained the largest number of seats in parliament. The governing coalition between the Venstre and the Conservative People's Party remained intact, with the Danish People's Party...

Danish parliament passed a law altering the line of succession to the throne of Denmark (and thus Greenland as well), and, after the 13 November 2007 election

Danish parliamentary election, 2007

The 66th Folketing election in Denmark was held on 13 November 2007. The election allowed prime minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen to continue for a third term in a coalition government consisting of the Liberals and the Conservative People's Party with parliamentary support from the Danish People's...

, the parliament

Folketing

The Folketing , is the national parliament of Denmark. The name literally means "People's thing"—that is, the people's governing assembly. It is located in Christiansborg Palace, on the islet of Slotsholmen in central Copenhagen....

had passed the law again in January 2009, whereby in June 2009, it was confirmed in the referendum.

Former monarchies

European colonization of the Americas

The start of the European colonization of the Americas is typically dated to 1492. The first Europeans to reach the Americas were the Vikings during the 11th century, who established several colonies in Greenland and one short-lived settlement in present day Newfoundland...

in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, however, many of these civilizations had ceased to function, due to various natural and artificial causes. Those that remained up to that period were eventually defeated by the agents of European monarchical powers, who, while they remained on the European continent, thereafter established new American administrations overseen by delegated viceroy

Viceroy

A viceroy is a royal official who runs a country, colony, or province in the name of and as representative of the monarch. The term derives from the Latin prefix vice-, meaning "in the place of" and the French word roi, meaning king. A viceroy's province or larger territory is called a viceroyalty...

s. Some of these colonies were, in turn, replaced by either republican states or locally founded monarchies, ultimately overtaking the entire American holdings of some European monarchs; those crowns that once held or claim territory in the Americas include the Spanish, Portuguese, French, Swedish, and Russian, and even Baltic Courland

Duchy of Courland and Semigallia

The Duchy of Courland and Semigallia is the name of a duchy in the Baltic region that existed from 1562 to 1569 as a vassal state of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and from 1569...

, Holy Roman, Prussian and Norwegian. Certain of the locally established monarchies were themselves also overthrown through revolution

Revolution

A revolution is a fundamental change in power or organizational structures that takes place in a relatively short period of time.Aristotle described two types of political revolution:...

, leaving five current pretenders to American thrones.

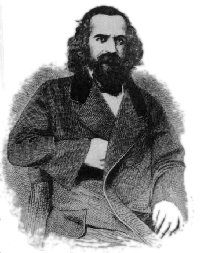

Araucania and Patagonia

Kingdom of Araucania and Patagonia

The Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia was the name of a state and kingdom created in the 19th century by a French lawyer and adventurer named Orélie-Antoine de Tounens. Orélie-Antoine de Tounens claimed the regions of Araucanía and eastern Patagonia hence the name of kingdom...

was a short-lived constitutional monarchy founded by French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

lawyer Orelie-Antoine de Tounens in 1860, encompassing the lower half of present-day Argentina

Argentina

Argentina , officially the Argentine Republic , is the second largest country in South America by land area, after Brazil. It is constituted as a federation of 23 provinces and an autonomous city, Buenos Aires...

and a small segment of Chile

Chile

Chile ,officially the Republic of Chile , is a country in South America occupying a long, narrow coastal strip between the Andes mountains to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west. It borders Peru to the north, Bolivia to the northeast, Argentina to the east, and the Drake Passage in the far...

, where Mapuche

Mapuche

The Mapuche are a group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern Argentina. They constitute a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who shared a common social, religious and economic structure, as well as a common linguistic heritage. Their influence extended...

were fighting to maintain their sovereignty against the advancing Chilean and Argentine authorities. Orelie-Antoine, who felt that the indigenous peoples would be better served in negotiations with the surrounding powers by a European leader, was elected by the Mapuche to be their king. His efforts to gain international recognition prompted the Chileans to occupy Araucanía

Occupation of the Araucanía

The Occupation of Araucanía was a series of military campaigns, agreements and penetrations by the Chilean army and settlers which led to the incorporation of Araucanía into Chilean national territory...

between 1861 and 1883, and King Orelie-Antoine was captured in 1862, to be imprisoned in an asylum in Chile. His descendant, Prince Felipe

Philippe Boiry

Philippe Paul Alexander Henry Boiry is the current pretender to the throne of the unrecognized Kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia. Phillippe became the current pretender after Antoine III abdicated in favor of him in 1951.-Life:...

, lives in France and, while the Mapuche Nation continues to recognise the Araucanian monarchy, he has renounced his claim to the Araucanian and Patagonian throne.

Aztec

The AztecAztec

The Aztec people were certain ethnic groups of central Mexico, particularly those groups who spoke the Nahuatl language and who dominated large parts of Mesoamerica in the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, a period referred to as the late post-classic period in Mesoamerican chronology.Aztec is the...

Empire

Empire

The term empire derives from the Latin imperium . Politically, an empire is a geographically extensive group of states and peoples united and ruled either by a monarch or an oligarchy....

existed in the central Mexican

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

region between c. 1325 and 1521, and was formed by the triple alliance

Aztec Triple Alliance

The Aztec Triple Alliance, or Aztec Empire began as an alliance of three Nahua city-states or "altepeme": Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan...

of the tlatoque

Tlatoani

Tlatoani is the Nahuatl term for the ruler of an altepetl, a pre-Hispanic state. The word literally means "speaker", but may be translated into English as "king". A is a female ruler, or queen regnant....

(the Nahuatl

Nahuatl

Nahuatl is thought to mean "a good, clear sound" This language name has several spellings, among them náhuatl , Naoatl, Nauatl, Nahuatl, Nawatl. In a back formation from the name of the language, the ethnic group of Nahuatl speakers are called Nahua...

term for "speaker", also translated in English

English language

English is a West Germanic language that arose in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and spread into what was to become south-east Scotland under the influence of the Anglian medieval kingdom of Northumbria...

as "king") of three city-state

City-state

A city-state is an independent or autonomous entity whose territory consists of a city which is not administered as a part of another local government.-Historical city-states:...

s: Tlacopan

Tlacopan

Tlacopan , also called Tacuba, was a Pre-Columbian Mesoamerican city-state situated on the western shore of Lake Texcoco.Founded by Tlacomatzin, Tlacopan was a Tepanec kingdom subordinate to nearby Azcapotzalco...

, Texcoco, and the capital of the empire, Tenochtitlan. While the lineage of Tenochtitlan's kings continued after the city's fall to the Spanish on 13 August 1521, they reigned as puppet rulers

Puppet state

A puppet state is a nominal sovereign of a state who is de facto controlled by a foreign power. The term refers to a government controlled by the government of another country like a puppeteer controls the strings of a marionette...

of the King of Spain until the death of the last dynastic tlatoani, Luis de Santa María Nanacacipactzin

Luis de Santa María Nanacacipactzin

Don Luis de Santa María Nanacacipactzin was the last tlatoani of the Nahua altepetl of Tenochtitlan, as well as its governor under the colonial Spanish system of government...

, on 27 December 1565.

Brazil

John VI of Portugal

John VI John VI John VI (full name: João Maria José Francisco Xavier de Paula Luís António Domingos Rafael; (13 May 1767 – 10 March 1826) was King of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves (later changed to just King of Portugal and the Algarves, after Brazil was recognized...

, Prince of Brazil, who was then acting as regent

Regent

A regent, from the Latin regens "one who reigns", is a person selected to act as head of state because the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. Currently there are only two ruling Regencies in the world, sovereign Liechtenstein and the Malaysian constitutive state of Terengganu...

for his ailing mother, Queen Maria

Maria I of Portugal

Maria I was Queen regnant of Portugal and the Algarves from 1777 until her death. Known as Maria the Pious , or Maria the Mad , she was the first undisputed Queen regnant of Portugal...

, elevated the colony to a constituent country

Constituent country

Constituent country is a phrase sometimes used in contexts in which a country makes up a part of a larger entity. The term constituent country does not have any defined legal meaning, and is used simply to refer to a country which is a part Constituent country is a phrase sometimes used in contexts...

of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves. While the royal court was still based in Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro

Rio de Janeiro , commonly referred to simply as Rio, is the capital city of the State of Rio de Janeiro, the second largest city of Brazil, and the third largest metropolitan area and agglomeration in South America, boasting approximately 6.3 million people within the city proper, making it the 6th...

, João ascended as king of the united kingdom the following year, and returned to Portugal in 1821, leaving his son, Prince Pedro, Prince of Brazil, as his regent in the Kingdom of Brazil. In September of that same year, the Portuguese parliament threatened to diminish Brazil back to the status of a colony, dismantle all the royal agencies in Rio de Janeiro, and demanded Pedro return to Lisbon

Lisbon

Lisbon is the capital city and largest city of Portugal with a population of 545,245 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Lisbon extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of 3 million on an area of , making it the 9th most populous urban...

. The Prince, however, feared these moves would trigger separatist movements and refused to comply; instead, at the urging of his father, he declared Brazil an independent constitutional monarchy

Brazilian Declaration of Independence

The Brazilian Independence comprised a series of political events occurred in 1821–1823, most of which involved disputes between Brazil and Portugal regarding the call for independence presented by the Brazilian Kingdom...

on 12 October 1822, and he was crowned emperor on 1 December as Pedro I. After Pedro abdicated

Abdication

Abdication occurs when a monarch, such as a king or emperor, renounces his office.-Terminology:The word abdication comes derives from the Latin abdicatio. meaning to disown or renounce...

the throne on 7 April 1831, the Brazilian empire saw only one additional monarch: Pedro II

Pedro II of Brazil

Dom Pedro II , nicknamed "the Magnanimous", was the second and last ruler of the Empire of Brazil, reigning for over 58 years. Born in Rio de Janeiro, he was the seventh child of Emperor Dom Pedro I of Brazil and Empress Dona Maria Leopoldina and thus a member of the Brazilian branch of...

, who reigned for 58 years before a coup d'état

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

overthrew the monarchy on 15 November 1889. There are presently two pretenders to the defunct Brazilian throne: Prince Luís of Orléans-Braganza

Prince Luís of Orléans-Braganza

Prince Luís of Orléans-Braganza is one of the two claimants to the defunct Brazilian throne, and head of the Vassouras branch of the Brazilian Imperial House...

, head of the Vassouras branch of the Brazilian Imperial Family, and, according to legitimist claims, de jure Emperor of Brazil; and Prince Pedro Carlos of Orléans-Braganza

Prince Pedro Carlos of Orléans-Braganza

Prince Pedro Carlos of Orléans-Braganza is one of two claimants to the defunct Brazilian throne, and head of the Petrópolis branch of the Brazilian Imperial House.-Life:...

, head of the Petrópolis

Petrópolis

Petrópolis , also known as The Imperial City of Brazil, is a town in the state of Rio de Janeiro, about 65 km from the city of Rio de Janeiro....

line of the Brazilian Imperial Family, and heir to the Brazilian throne according to royalists.

The Brazilian Constitution of 1988 called for a general vote on the restoration of the monarchy, which was held in 1993. The Royalists went to the polls divided, with the press indicating there were actually two princes aspiring to the Brazilian Royal throne (Dom Luiz de Orleans e Bragança and Dom João Henrique); this created some confusion among the voters. Voting tickets further divided the electorate by placing one box for a presidential republic on the ballot and four for the monarchy. Additional anti-monarchial sentiment was generated by several aggressive TV commercials claiming that a vote for monarchy would be a vote for the return of slavery for blacks, together with Brazil's recent return to democracy after decades of military dictatorship; this resulted in a disastrous performance for the Monarchists at the polls. The referendum of 1993 was the last attempt (as of 2011) at restoring the monarchy in Brazil.

Haiti

The entire island of HispaniolaHispaniola

Hispaniola is a major island in the Caribbean, containing the two sovereign states of the Dominican Republic and Haiti. The island is located between the islands of Cuba to the west and Puerto Rico to the east, within the hurricane belt...

was first claimed on 5 December 1492, by Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the...

, for Queen Isabella

Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I was Queen of Castile and León. She and her husband Ferdinand II of Aragon brought stability to both kingdoms that became the basis for the unification of Spain. Later the two laid the foundations for the political unification of Spain under their grandson, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor...

, and attempts were immediately made at establishing colonies. However, in 1664, King Louis XIV

Louis XIV of France

Louis XIV , known as Louis the Great or the Sun King , was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and Navarre. His reign, from 1643 to his death in 1715, began at the age of four and lasted seventy-two years, three months, and eighteen days...

formally claimed the western half of Hispaniola, and established the first French settlement in 1670, with the colony administered by a governor-general representing the French crown, an arrangement that stood until the French Revolution

French Revolution

The French Revolution , sometimes distinguished as the 'Great French Revolution' , was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France and Europe. The absolute monarchy that had ruled France for centuries collapsed in three years...

toppled the monarchy of France on 21 September 1792. Though the French government retained control over the region of Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue

The labour for these plantations was provided by an estimated 790,000 African slaves . Between 1764 and 1771, the average annual importation of slaves varied between 10,000-15,000; by 1786 it was about 28,000, and from 1787 onward, the colony received more than 40,000 slaves a year...

, on 22 September 1804, Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Jean-Jacques Dessalines

Jean-Jacques Dessalines was a leader of the Haitian Revolution and the first ruler of an independent Haiti under the 1801 constitution. Initially regarded as Governor-General, Dessalines later named himself Emperor Jacques I of Haiti...

, who had served as Governor-General of Saint-Domingue since 30 November 1803, declared himself as head of an independent Empire of Haiti, with his coronation as Emperor Jacques I taking place on 6 October that year. After his assassination on 17 October 1806, the country was split in half, the northern portion eventually becoming the Kingdom of Haiti

Kingdom of Haiti

The Kingdom of Haiti was the state established by Henri Christophe on March 28, 1811 when he was proclaimed King Henri I having previously ruled as president. This was Haiti's second attempt at monarchal rule as Jean-Jacques Dessalines had previously ruled over the Empire of Haiti...

on 28 March 1811, with Henri Christophe

Henri Christophe

Henri Christophe was a key leader in the Haitian Revolution, winning independence from France in 1804. On 17 February 1807, after the creation of a separate nation in the north, Christophe was elected President of the State of Haiti...

installed as King Henri I. When King Henri committed suicide on 8 October 1820, and his son, Jacques-Victor Henry, Prince Royal of Haiti

Jacques-Victor Henry, Prince Royal of Haiti

Prince Jacques-Victor Henry was the heir apparent to the throne of the Kingdom of Haiti.He was the youngest child of Henri Christophe, then a general in the Haitian Army, by his wife Marie-Louise Coidavid. His father became President of the state of Haiti in 1807, and on March 26, 1811 he was...

, was murdered by revolutionaries ten days later, the kingdom was merged into the southern Republic of Haiti, of which Faustin-Élie Soulouque

Faustin I of Haiti

Faustin I was born Faustin-Élie Soulouque. He was a career officer and general in the Haïtian army when he was elected President of Haïti in 1847. In 1849 he was proclaimed Emperor of Haïti under the name of Faustin I...

was elected president

President of Haiti

The President of the Republic of Haiti is the head of state of Haiti. Executive power in Haiti is divided between the president and the government headed by the Prime Minister of Haiti...

on 2 March 1847. Two years later, on 26 August 1849, the Haitian national assembly

National Assembly of Haïti

The Parliament of Haiti is the legislature of the Republic of Haiti. It sits at the Haitian capital, Port-au-Prince. The Parliament is bicameral, the upper house being the Senate of Haiti and the lower house being the Chamber of Deputies of Haiti....

declared the president as Emperor Faustin I, thereby re-establishing the Empire of Haiti. But this monarchical reincarnation was to be short lived as well, as a revolution broke out in the kingdom in 1858, resulting in Faustin abdicating the throne on 18 January 1859.

Inca

Inca civilization

The Andean civilizations made up a loose patchwork of different cultures that developed from the highlands of Colombia to the Atacama Desert. The Andean civilizations are mainly based on the cultures of Ancient Peru and some others such as Tiahuanaco. The Inca Empire was the last sovereign...

spread across the north western parts of South America between 1200 and 1573, ruled over by a monarch addressed as the Sapa Inca, Sapa, or Apu. The civilization emerged in the Kingdom of Cusco

Kingdom of Cusco

The Kingdom of Cusco was a small kingdom in the Andes that began as a small city-state founded by the Incas around the 12th century...

, and expanded to become the Ttahuantin-suyu, or "land of the four sections", each ruled by a governor or viceroy called Apu-cuna, under the leadership of the central Sapa Inca. The empire eventually fell to the Spanish in 1533, when the last king, Atahualpa

Atahualpa

Atahualpa, Atahuallpa, Atabalipa, or Atawallpa , was the last Sapa Inca or sovereign emperor of the Tahuantinsuyu, or the Inca Empire, prior to the Spanish conquest of Peru...

, was captured and executed on 29 August. The conquerors installed other Incan kings– beginning with Atahualpa's brother, Túpac Huallpa

Tupac Huallpa

Túpac Huallpa , original name Auqui Huallpa Túpac, was a puppet Inca Emperor of the conquistadors in 1533, during the Spanish conquest of the Inca Empire led by Francisco Pizarro.-Life:...

– and the line continued in this manner until the death of Túpac Amaru

Túpac Amaru

Túpac Amaru, also called Thupa Amaro , was the last indigenous leader of the Inca state in Peru.-Accession:...

in 1572.

Maya

The Mayan Empire was located on the Yucatán PeninsulaYucatán Peninsula

The Yucatán Peninsula, in southeastern Mexico, separates the Caribbean Sea from the Gulf of Mexico, with the northern coastline on the Yucatán Channel...

and into the isthmian

Isthmus

An isthmus is a narrow strip of land connecting two larger land areas usually with waterforms on either side.Canals are often built through isthmuses where they may be particularly advantageous to create a shortcut for marine transportation...

portion of North America, and Northern portion of Central America (Guatemala and Honduras) was formed of a number of ajawil, ajawlel, or ajawlil– hierarchical polities headed by an hereditary ruler known as a kuhul ajaw

Ajaw

Ajaw is a political rulership title attested from the epigraphic inscriptions of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization, with a meaning variously interpreted as "lord", "ruler", "king" or "leader". It denoted any of the leading class of nobles in a particular polity and was not limited to a single...

(the Mayan

Mayan languages

The Mayan languages form a language family spoken in Mesoamerica and northern Central America. Mayan languages are spoken by at least 6 million indigenous Maya, primarily in Guatemala, Mexico, Belize and Honduras...