History of Christianity in the United States

Encyclopedia

Christianity was introduced to North America

as it was colonized by Europeans

beginning in the 16th

and 17th centuries

. The Spanish

, French

, and British

brought Roman Catholicism to the colonies of New Spain

, New France

and Maryland respectively, while Northern European peoples introduced Protestantism

to Massachusetts Bay Colony

, New Netherland

, Virginia colony, Carolina Colony, Newfoundland and Labrador

, and Lower Canada

. Among Protestants, adherents to Anglicanism

, the Baptist Church, Congregationalism

, Presbyterianism

, Lutheranism

, Quakerism, Mennonite

and Moravian Church were the first to settle to the US, spreading their faith in the new country.

Today most Christians in the United States

are Mainline Protestant, Evangelical

, or Roman Catholic.

, such as St. Augustine, Florida

in 1565, the earliest Christians in the territory which would eventually become the United States were Roman Catholics. However, the territory that would become the Thirteen Colonies

in 1776 was largely populated by Protestants due to Protestant settlers seeking religious freedom from the Church of England

(est. 1534). These settlers were primarily Puritans from East Anglia

, especially just before the English Civil War

(1641–1651); there were also some Anglicans and Catholics but these were far fewer in number. Because of the predominance of Protestants among those coming from England, the English colonies

became almost entirely Protestant by the time of the American Revolution

.

Catholicism first came to the territories now forming the United States just before the Protestant Reformation

Catholicism first came to the territories now forming the United States just before the Protestant Reformation

(1517) with the Spanish conquistadors and settlers in present-day Florida

(1513) and the southwest. The first Christian worship service held in the current United States was a Catholic Mass celebrated in Pensacola, Florida.(St. Michael records) The Spanish spread Roman Catholicism through Spanish Florida

by way of its mission system

; these missions extended into Georgia

and the Carolinas

. Eventually, Spain established missions in what are now Texas

, New Mexico

, Arizona

, and California

. Junípero Serra

(d.1784) founded a series of missions in California which became important economic, political, and religious institutions. Overland routes were established from New Mexico that resulted in the colonization of San Francisco

in 1776 and Los Angeles

in 1781.

In the French territories, Catholicism was ushered in with the establishment of colonies and forts in Detroit, St. Louis, Mobile

In the French territories, Catholicism was ushered in with the establishment of colonies and forts in Detroit, St. Louis, Mobile

, Biloxi, Baton Rouge, and New Orleans. In the late 17th century, French expeditions, which included sovereign, religious and commercial aims, established a foothold on the Mississippi River

and Gulf Coast. With its first settlements, France lay claim to a vast region of North America and set out to establish a commercial empire and French nation stretching from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada.

The French colony of Louisiana

originally claimed all the land on both sides of the Mississippi River and the lands that drained into it. The following present day states were part of the then vast tract of Louisiana: Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota.

, refused to compromise passionately held religious convictions (largely stemming from the Protestant Reformation

which began c. 1517) and fled Europe.

settled the Plymouth Colony

in Plymouth, Massachusetts

in 1620, seeking refuge from conflicts in England which led up to the English Civil War

.

The Puritans, a much larger group than the Pilgrims, established the Massachusetts Bay Colony

in 1629 with 400 settlers. Puritans were English Protestants who wished to reform and purify the Church of England

in the New World of what they considered to be unacceptable residues of Roman Catholicism. Within two years, an additional 2,000 settlers arrived. Beginning in 1630, as many as 20,000 Puritans emigrated to America from England to gain the liberty to worship as they chose. Most settled in New England, but some went as far as the West Indies. Theologically, the Puritans were "non-separating Congregationalist

s". The Puritans created a deeply religious, socially tight-knit and politically innovative culture that is still present in the modern United States. They hoped this new land would serve as a "redeemer nation

".

The Salem witch trials

were a series of hearings before local magistrates followed by county court trial

s to prosecute people accused of witchcraft

in Essex

, Suffolk

and Middlesex

counties of colonial Massachusetts, between February 1692 and May 1693. Over 150 people were arrested and imprisoned, with even more accused but not formally pursued by the authorities. The two courts convicted twenty-nine people of the capital felony

of witchcraft. Nineteen of the accused, fourteen women and five men, were hanged. One man (Giles Corey

) who refused to enter a plea was crushed to death under heavy stones in an attempt to force him to do so. At least five more of the accused died in prison.

of London, who wanted to get rich. They also wanted the Church to flourish in their colony and kept it well supplied with ministers. Some early governors sent by the Virginia Company acted in the spirit of crusaders. During governor Thomas Dale

's tenure, religion was spread at the point of the sword. Everyone was required to attend church and be catechized by a minister. Those who refused could be executed or sent to the galleys.

When a popular assembly, the House of Burgesses

, was established in 1619, it enacted religious laws that "were a match for anything to be found in the Puritan societies." Unlike the colonies to the north, where the Church of England was regarded with suspicion throughout the colonial period, Virginia was a bastion of Anglicanism

.

The Church in Virginia faced problems unlike those confronted in other colonies—such as enormous parishes, some sixty miles long, and the inability to ordain ministers locally due to the lack of a bishop — but it continued to command the loyalty and affection of the colonists.

, who preached religious tolerance, separation of church and state, and a complete break with the Church of England, was banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony

and founded Rhode Island Colony, which became a haven for other religious refugees from the Puritan community. Some migrants who came to Colonial America were in search of the freedom to practice forms of Christianity which were prohibited and persecuted in Europe. Since there was no state religion

, in fact there was not yet a state

, and since Protestantism had no central authority, religious practice in the colonies became diverse.

The Religious Society of Friends

formed in England in 1652 around leader George Fox

. Quakers were severely persecuted in England for daring to deviate so far from Anglicanism

. This reign of terror impelled Friends to seek refuge in New Jersey

in the 1670s, formally part of New Netherland

, where they soon became well entrenched. In 1681, when Quaker leader William Penn

parlayed a debt owed by Charles II

to his father into a charter for the Province of Pennsylvania

, many more Quakers were prepared to grasp the opportunity to live in a land where they might worship freely. By 1685, as many as 8,000 Quakers had come to Pennsylvania. Although the Quakers may have resembled the Puritans in some religious beliefs and practices, they differed with them over the necessity of compelling religious uniformity in society.

Pennsylvania Germans are inaccurately known as Pennsylvania Dutch

from a misunderstanding of "Pennsylvania Deutsch", the group's German language

name. The first group of Germans

to settle in Pennsylvania arrived in Philadelphia in 1683 from Krefeld, Germany, and included Mennonite

s and possibly some Dutch Quakers.

The efforts of the founding fathers

to find a proper role for their support of religion—and the degree to which religion can be supported by public officials without being inconsistent with the revolutionary imperative of freedom of religion

for all citizens—is a question that is still debated in the country today.

by Jesuit

settlers from England

in 1634. Maryland was one of the few regions among the English colonies in North America that was predominantly Catholic.

However, the 1646 defeat of the Royalists

in the English Civil War

led to stringent laws against Catholic education and the extradition of known Jesuits from the colony, including Andrew White

, and the destruction of their school at Calverton Manor. During the greater part of the Maryland colonial period, Jesuits continued to conduct Catholic schools clandestinely.

Maryland was a rare example of religious toleration

in a fairly intolerant age, particularly amongst other English colonies which frequently exhibited a quite militant Protestantism

. The Maryland Toleration Act

, issued in 1649, was one of the first laws that explicitly defined tolerance of varieties of religion (as long as it was Christian

). It has been considered a precursor to the First Amendment

.

Although the Stuart

kings of England did not hate the Roman Catholic Church, their subjects did, causing Catholics to be harassed and persecuted in England throughout the 17th century. Driven by the "duty of finding a refuge for his Roman Catholic brethren," George Calvert obtained a Maryland charter from Charles I in 1632 for the territory between Pennsylvania and Virginia. In 1634, two ships, the Ark and the Dove, brought the first settlers to Maryland. Aboard were approximately two hundred people.

Roman Catholic fortunes fluctuated in Maryland during the rest of the 17th century, as they became an increasingly smaller minority of the population. After the Glorious Revolution of 1689 in England, penal laws deprived Roman Catholics of the right to vote, hold office, educate their children or worship publicly. Until the American Revolution

, Roman Catholics in Maryland were dissenters in their own country, but keeping loyal to their convictions. At the time of the Revolution, Roman Catholics formed less than 1% of the population of the thirteen colonies, in 2007, Roman Catholics comprised 24% of US population.

. Because the Reformation was based on an effort to correct what it perceived to be errors and excesses of the Catholic Church, it formed strong positions against the Roman clerical hierarchy and the Papacy in particular. These positions were brought to the New World by British colonists who were predominantly Protestant, and who opposed not only the Roman Catholic Church but also the Church of England which, due to its perpetuation of Catholic doctrine and practices, was deemed to be insufficiently reformed, see also Ritualism. Because many of the British colonists, such as the Puritan

s, were fleeing religious persecution by the Church of England, early American religious culture exhibited a more extreme anti-Catholic bias of these Protestant denominations.

Monsignor Ellis wrote that a universal anti-Catholic bias was "vigorously cultivated in all the thirteen colonies from Massachusetts

to Georgia

" and that Colonial charters and laws contained specific proscriptions against Roman Catholics. Ellis also wrote that a common hatred of the Roman Catholic Church could unite Anglican clerics and Puritan

ministers despite their differences and conflicts.

was celebrated on board a Russian ship off the Alaskan coast. In 1794, the Russian Orthodox Church

sent missionaries—among them Saint Herman of Alaska

-- to establish a formal mission in Alaska

. Their missionary endeavors contributed to the conversion of many Alaskan natives to the Orthodox faith. A diocese was established, whose first bishop was Saint Innocent of Alaska

.

By 1780 the percentage of adult colonists who adhered to a church was between 10-30%, not counting slaves or Native Americans. North Carolina had the lowest percentage at about 4%, while New Hampshire and South Carolina were tied for the highest, at about 16%.

Evangelicalism is difficult to date and to define. Scholars have argued that, as a self-conscious movement, evangelicalism did not arise until the mid-17th century, perhaps not until the Great Awakening itself. The fundamental premise of evangelicalism is the conversion of individuals from a state of sin to a "new birth" through preaching of the Word. The Great Awakening

Evangelicalism is difficult to date and to define. Scholars have argued that, as a self-conscious movement, evangelicalism did not arise until the mid-17th century, perhaps not until the Great Awakening itself. The fundamental premise of evangelicalism is the conversion of individuals from a state of sin to a "new birth" through preaching of the Word. The Great Awakening

refers to a northeastern Protestant revival movement that took place in the 1730s and 1740s.

The first generation of New England Puritans required that church members undergo a conversion experience that they could describe publicly. Their successors were not as successful in reaping harvests of redeemed souls. The movement began with Jonathan Edwards, a Massachusetts preacher who sought to return to the Pilgrims' strict Calvinist roots. British preacher George Whitefield

and other itinerant preachers continued the movement, traveling across the colonies and preaching in a dramatic and emotional style. Followers of Edwards and other preachers of similar religiosity called themselves the "New Lights," as contrasted with the "Old Lights," who disapproved of their movement. To promote their viewpoints, the two sides established academies and colleges, including Princeton

and Williams College

. The Great Awakening has been called the first truly American event.

The supporters of the Awakening and its evangelical thrust—Presbyterians, Baptists and Methodists—became the largest American Protestant denominations by the first decades of the 19th century. By the 1770s, the Baptists were growing rapidly both in the north (where they founded Brown University

), and in the South. Opponents of the Awakening or those split by it—Anglicans, Quakers, and Congregationalists—were left behind.

s. Religious practice suffered in certain places because of the absence of ministers and the destruction of churches, but in other areas, religion flourished.

The American Revolution inflicted deeper wounds on the Church of England in America than on any other denomination because the King of England was the head of the church. The Book of Common Prayer

offered prayers for the monarch, beseeching God "to be his defender and keeper, giving him victory over all his enemies," who in 1776 were American soldiers as well as friends and neighbors of American Anglicans. Loyalty to the church and to its head could be construed as treason to the American cause. Patriotic American Anglicans, loathing to discard so fundamental a component of their faith as The Book of Common Prayer, revised it to conform to the political realities.

Another result of this was that the first constitution of an independent Anglican Church in the country bent over backwards to distance itself from Rome by calling itself the Protestant Episcopal Church, incorporating in its name the term, Protestant, that Anglicans elsewhere had shown some care in using too prominently due to their own reservations about the nature of the Church of England, and other Anglican bodies, vis-à-vis later radical reformers who were happier to use the term Protestant.

s establishing how each would be governed. For three years, from 1778 to 1780, the political energies of Massachusetts were absorbed in drafting a charter of government that the voters would accept.

One of the most contentious issues was whether the state would support the church financially. Advocating such a policy were the ministers and most members of the Congregational Church, which had been established, and hence had received public financial support, during the colonial period. The Baptists, who had grown strong since the Great Awakening, tenaciously adhered to their ancient conviction that churches should receive no support from the state.

The Constitutional Convention chose to support the church and Article Three authorized a general religious tax to be directed to the church of a taxpayers' choice. Despite substantial doubt that Article Three had been approved by the required two thirds of the voters, in 1780 Massachusetts authorities declared it and the rest of the state constitution to have been duly adopted. Such tax laws also took effect in Connecticut

and New Hampshire

.

In 1788, John Jay

urged the New York Legislature

to require office-holders to renounce foreign authorities "in all matters ecclesiastical as well as civil.".

Christianity grew and took root in new areas, along with new Protestant denominations such as Adventism, the Restoration Movement

, and groups such as Jehovah's Witnesses

and Mormonism

. While the First Great Awakening

was centered on reviving the spirituality of established congregations, the Second Great Awakening

(1800–1830s), unlike the first, focused on the unchurched and sought to instill in them a deep sense of personal salvation as experienced in revival meetings.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, Bishop

Francis Asbury

led the American Methodist movement as one of the most prominent religious leaders of the young republic. Traveling throughout the eastern seaboard, Methodism

grew quickly under Asbury's leadership into one of the nation's largest and most influential denominations.

The principal innovation produced by the revivals was the camp meeting

. The revivals were organized by Presbyterian ministers who modeled them after the extended outdoor "communion seasons," used by the Presbyterian Church in Scotland, which frequently produced emotional, demonstrative displays of religious conviction. In Kentucky, the pioneers loaded their families and provisions into their wagons and drove to the Presbyterian meetings, where they pitched tents and settled in for several days.

When assembled in a field or at the edge of a forest for a prolonged religious meeting, the participants transformed the site into a camp meeting. The religious revivals that swept the Kentucky camp meetings were so intense and created such gusts of emotion that their original sponsors, the Presbyterians, soon repudiated them. The Methodists, however, adopted and eventually domesticated camp meetings and introduced them into the eastern United States, where for decades they were one of the evangelical signatures of the denomination.

of the early 19th century. The movement sought to reform the church and unite Christians. Barton W. Stone

and Alexander Campbell

each independently developed similar approaches to the Christian faith, seeking to restore the whole Christian church, on the pattern set forth in the New Testament

. Both groups believed that creeds kept Christianity divided. They joined in fellowship in 1832 with a handshake.

They were united, among other things, in the belief that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, that churches celebrate the Lord's Supper

on the first day of each week

, and that baptism of adult believers

, by immersion in water, is a necessary condition for Salvation

.

The Restoration Movement began as two separate threads, each of which initially developed without the knowledge of the other, during the Second Great Awakening

in the early 19th century. The first, led by Barton W. Stone

began at Cane Ridge, Bourbon County, Kentucky. The group called themselves simply Christians. The second, began in western Pennsylvania and Virginia (now West Virginia), led by Thomas Campbell and his son, Alexander Campbell. Because the founders wanted to abandon all denominational labels, they used the biblical names for the followers of Jesus that they found in the Bible. Both groups promoted a return to the purposes of the 1st century churches as described in the New Testament. One historian of the movement has argued that it was primarily a unity movement, with the restoration motif playing a subordinate role.

The Restoration Movement has seen several divisions, resulting in multiple separate groups. Three modern groups claim the Stone Campbell movement as their roots: Churches of Christ, Christian churches and churches of Christ, and the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)

. Some see divisions in the movement as the result of the tension between the goals of restoration and ecumenism, with the Churches of Christ and Christian churches and churches of Christ resolving the tension by stressing restoration while the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)

resolved the tension by stressing ecumenism.

follow teachings

of Joseph Smith, Jr., and is strongly restorationist in outlook. The movement's history

is characterized by intense controversy and persecution in reaction to some of the its unique

doctrines and practices.

The Latter Day Saint movement

traces their origins to the Burned-over district

of western New York

, where Joseph Smith, Jr., reported seeing God the Father

and Jesus Christ, eventually leading him to doctrines that, he said, were lost after the apostles were killed. Joseph Smith gained a small following in the late 1820s as he was dictating the Book of Mormon

, which he said was a translation of words found on a set of golden plates

that had been buried near his home by an indigenous American

prophet. After publishing of the Book of Mormon in 1830, the church rapidly gained a following. It first moved to Kirtland, Ohio

, then to Missouri

in 1838, where the 1838 Mormon War with other settlers ensued, culminating in adherents being expelled under an "extermination order" signed by the governor of Missouri. Smith built the city of Nauvoo, Illinois

, where he was assassinated

.

After Smith's death, a succession crisis ensued, and the majority accepted Brigham Young

as the church's leader. Young governed his followers

as a theocratic

leader serving in both political and religious positions. After continued difficulties and persecution in Illinois, Young left Nauvoo in 1846 and led his followers, the Mormon pioneers, to the Great Salt Lake Valley

in what is today Utah

.

began to study the Bible with a group of Millerist Adventist

s, including George Storrs

and George Stetson

, and beginning in 1877 Russell jointly edited a religious journal, Herald of the Morning, with Nelson H. Barbour

. In July 1879, after separating from Barbour, Russell began publishing the magazine Zion's Watch Tower and Herald of Christ's Presence

, highlighting his interpretations of biblical chronology, with particular attention to his belief that the world was in "the last days". In 1881, Zion's Watch Tower Tract Society was formed in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

, to disseminate tracts, papers, doctrinal treatises and bibles; three years later, on December 15, 1884, Russell became the president of the Society when it was legally incorporated in Pennsylvania

.

Russell's group split into several rival organisations after his death in 1916. One of those groups retained control of Russell's magazine, Zion's Watch Tower and Herald of Christ's Presence, and his legal corporation, the Watch Tower Bible & Tract Society of Pennsylvania and adopted the name Jehovah's witnesses

in 1931. Substantial organizational and doctrinal changes occurred between 1917 and the 1950s. The religion's history has consisted of four distinct phases linked with the successive presidencies of Charles Taze Russell

, Joseph Rutherford

, Nathan Knorr

and Frederick Franz

.

In his January 1, 1802 reply to the Danbury Baptist Association Jefferson summed up the First Amendment's original intent, and used for the first time anywhere a now-familiar phrase in today's political and judicial circles: the amendment established a "wall of separation between church and state." Largely unknown in its day, this phrase has since become a major Constitutional issue. The first time the U.S. Supreme Court cited that phrase from Jefferson was in 1878, 76 years later.

that many white Baptists and Methodists had advocated immediately after the American Revolution.

When their discontent could not be contained, forceful black leaders followed what was becoming an American habit—they formed new denominations. In 1787, Richard Allen

and his colleagues in Philadelphia broke away from the Methodist Church and in 1815 founded the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church

, which, along with independent black Baptist congregations, flourished as the century progressed.

descent in Germantown, Pennsylvania

(now part of Philadelphia) wrote a two-page condemnation of the practice and sent it to the governing bodies of their Quaker church, the Society of Friends. Though the Quaker establishment took no immediate action, the 1688 Germantown Quaker Petition Against Slavery

, was an unusually early, clear and forceful argument against slavery and initiated the process of banning slavery in the Society of Friends (1776) and Pennsylvania

(1780).

The Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage

was the first American abolition society, formed 14 April 1775, in Philadelphia, primarily by Quakers who had strong religious objections to slavery.

After the American Revolutionary War

, Quaker and Moravian advocates helped persuade numerous slaveholders in the Upper South to free their slaves. Theodore Weld, an evangelical minister, and Robert Purvis

, a free African American, joined Garrison in 1833 to form the Anti-Slavery Society (Faragher 381). The following year Weld encouraged a group of students at Lane Theological Seminary to form an anti-slavery society. After the president, Lyman Beecher

, attempted to suppress it, the students moved to Oberlin College

. Due to the students' anti-slavery position, Oberlin soon became one of the most liberal colleges and accepted African American students. Along with Garrison, were Northcutt and Collins as proponents of immediate abolition. These two ardent abolitionists felt very strongly that it could not wait and that action needed to be taken right away.

After 1840 "abolition" usually referred to positions like Garrison's; it was largely an ideological movement led by about 3000 people, including free blacks and people of color, many of whom, such as Frederick Douglass

, and Robert Purvis

and James Forten

in Philadelphia, played prominent leadership roles. Abolitionism had a strong religious base including Quakers, and people converted by the revivalist fervor of the Second Great Awakening

, led by Charles Finney in the North in the 1830s. Belief in abolition contributed to the breaking away of some small denominations, such as the Free Methodist Church

.

Evangelical

abolitionists founded some colleges, most notably Bates College

in Maine

and Oberlin College

in Ohio

. The well-established colleges, such as Harvard

, Yale

and Princeton

, generally opposed abolition, although the movement did attract such figures as Yale president Noah Porter

and Harvard president Thomas Hill

.

Daniel O'Connell

, the Roman Catholic leader of the Irish in Ireland, supported the abolition of slavery in the British Empire and in America. O'Connell had played a leading role in securing Catholic Emancipation

(the removal of the civil and political disabilities of Roman Catholics in Great Britain and Ireland) and he was one of William Lloyd Garrison

's models. Garrison recruited him to the cause of American abolitionism. O'Connell, the black abolitionist Charles Lenox Remond

, and the temperance priest Theobold Mayhew organized a petition with 60,000 signatures urging the Irish of the United States to support abolition. O'Connell also spoke in the United States for abolition.

The Catholic Church in America had long ties in slaveholding Maryland and Louisiana. Despite a firm stand for the spiritual equality of black people, and the resounding condemnation of slavery by Pope Gregory XVI in his bull In Supremo Apostolatus

issued in 1839, the American church continued in deeds, if not in public discourse, to support slaveholding interests. The Bishop of New York denounced O'Connell's petition as a forgery, and if genuine, an unwarranted foreign interference. The Bishop of Charleston declared that, while Catholic tradition opposed slave trading, it had nothing against slavery. No American bishop supported abolition before the Civil War. While the war went on, they continued to allow slave-owners to take communion.

One historian observed that ritualist churches separated themselves from heretics rather than sinners; he observed that Episcopalians and Lutherans also accommodated themselves to slavery. (Indeed, one southern Episcopal bishop was a Confederate general.) There were more reasons than religious tradition, however, as the Anglican Church had been the established church in the South during the colonial period. It was linked to the traditions of landed gentry and the wealthier and educated planter classes, and the Southern traditions longer than any other church. In addition, while the Protestant missionaries of the Great Awakening initially opposed slavery in the South, by the early decades of the 19th century, Baptist and Methodist preachers in the South had come to an accommodation with it in order to evangelize with farmers and artisans. By the Civil War, the Baptist and Methodist churches split into regional associations because of slavery.

After O'Connell's failure, the American Repeal Associations broke up; but the Garrisonians rarely relapsed into the "bitter hostility" of American Protestants towards the Roman Church. Some antislavery men joined the Know Nothings in the collapse of the parties; but Edmund Quincy ridiculed it as a mushroom growth, a distraction from the real issues. Although the Know-Nothing legislature of Massachusetts honored Garrison, he continued to oppose them as violators of fundamental rights to freedom of worship.

mage:Uncle toms cabin first edition.jpg|thumb|right|150px|First edition Uncle Tom's Cabin

, 1852, USA edition; published simultaneously on both sides of the Atlantic by American author

The abolitionist movement was strengthened by the activities of free African-Americans, especially in the black church, who argued that the old Biblical justifications for slavery contradicted the New Testament

. African-American activists and their writings were rarely heard outside the black community; however, they were tremendously influential to some sympathetic white people, most prominently the first white activist to reach prominence, William Lloyd Garrison

, who was its most effective propagandist. Garrison's efforts to recruit eloquent spokesmen led to the discovery of ex-slave Frederick Douglass

, who eventually became a prominent activist in his own right.

, the politically powerful Roman Catholic Archbishop

of Saint Paul, Minnesota

; and Alexis Toth, an influential Ruthenian Catholic

priest. Archbishop Ireland's refusal to accept Fr. Toth's credentials as a priest induced Fr. Toth to return to the Orthodox Church of his ancestors, and further resulted in the return of tens of thousands of other Uniate Catholics in North America to the Orthodox Church, under his guidance and inspiration. For this reason, Ireland is sometimes ironically remembered as the "Father of the Orthodox Church in America." These Uniates were received into Orthodoxy into the existing North American diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church. At the same time large numbers of Greeks and other Orthodox Christians were also immigrating to America. At this time all Orthodox Christians in North America were united under the omophorion

(Church authority and protection) of the Patriarch of Moscow, through the Russian Church's North American diocese. The unity was not merely theoretical, but was a reality, since there was then no other diocese on the continent. Under the aegis of this diocese, which at the turn of the 20th century was ruled by Bishop (and future Patriarch) Tikhon

, Orthodox Christians of various ethnic backgrounds were ministered to, both non-Russian and Russian; a Syro-Arab mission was established in the episcopal leadership of Saint Raphael of Brooklyn

, who was the first Orthodox bishop to be consecrated in America.

. In the United States, religious observance is much higher than in Europe, and the United States' culture leans conservative in comparison to other western nations, in part due to the Christian element.

Liberal Christianity

, exemplified by some theologians, sought to bring to churches new critical approaches to the Bible. Sometimes called liberal theology, liberal Christianity is an umbrella term covering movements and ideas within 19th and 20th century Christianity. New attitudes became evident, and the practice of questioning the nearly universally accepted Christian orthodoxy began to come to the forefront.

In the post–World War I era, Liberalism

In the post–World War I era, Liberalism

was the faster growing sector of the American church. Liberal wings of denominations were on the rise, and a considerable number of seminaries held and taught from a liberal perspective as well. In the post–World war II era, the trend began to swing back towards the conservative camp in America's seminaries and church structures.

and source criticism in modern Christianity. In reaction to liberal Protestant groups that denied doctrines considered fundamental to these conservative groups, they sought to establish tenets necessary to maintaining a Christian identity, the "fundamentals," hence the term fundamentalist.

Especially targeting critical approaches to the interpretation of the Bible, and trying to blockade the inroads made into their churches by secular scientific assumptions, the fundamentalists grew in various denominations as independent movements of resistance to the drift away from historic Christianity.

Especially targeting critical approaches to the interpretation of the Bible, and trying to blockade the inroads made into their churches by secular scientific assumptions, the fundamentalists grew in various denominations as independent movements of resistance to the drift away from historic Christianity.

Over time, the movement divided, with the label Fundamentalist being retained by the smaller and more hard-line group(s). Evangelical

has become the main identifier of the groups holding to the movement's moderate and earliest ideas.

, Southern Germany, Italy, Poland and Eastern Europe

. This influx would eventually bring increased political power for the Roman Catholic Church and a greater cultural presence, led at the same time to a growing fear of the Catholic "menace." As the 19th century wore on animosity waned, Protestant Americans realized that Roman Catholics were not trying to seize control of the government. Nonetheless, fears continued into the 20th century that there was too much "Catholic influence" on the government.

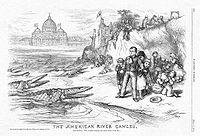

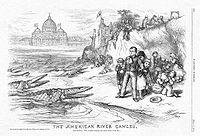

Anti-Catholic animus in the United States reached a peak in the 19th century when the Protestant population became alarmed by the influx of Catholic immigrants. Fearing the end of time, some American Protestants who believed they were God's chosen people

Anti-Catholic animus in the United States reached a peak in the 19th century when the Protestant population became alarmed by the influx of Catholic immigrants. Fearing the end of time, some American Protestants who believed they were God's chosen people

, went so far as to claim that the Catholic Church was the Whore of Babylon

in the Book of Revelation

.

The resulting "nativist" movement, which achieved prominence in the 1840s, was whipped into a frenzy of anti-Catholicism that led to mob violence, the burning of Catholic property, and the killing of Catholics.

This violence was fed by claims that Catholics were destroying the culture of the United States. Irish Catholic immigrants were blamed for raising the taxes of the country as well as for spreading violence and disease.

The nativist movement found expression in a national political movement called the Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s, which (unsuccessfully) ran former president Millard Fillmore

as its presidential candidate in 1856.

The Catholic parochial school system developed in the early-to-mid-19th century partly in response to what was seen as anti-Catholic bias in American public schools. The recent wave of newly established Protestant schools is sometimes similarly attributed to the teaching of evolution (as opposed to creationism) in public schools.

Most states passed a constitutional amendment, called "Blaine Amendments, forbidding tax money be used to fund parochial schools, a possible outcome with heavy immigration from Catholic Ireland after the 1840s. In 2002, the United States Supreme Court partially vitiated these amendments, in theory, when they ruled that vouchers were constitutional if tax dollars followed a child to a school, even if it were religious. However, no state school system had, by 2009, changed its laws to allow this.

The Knights of Labor

was the earliest labor organization in the United States, and in the 1880s, the was the largest labor union in the United States. and it is estimated that at least half its membership was Catholic (including Terence Powderly, its president from 1881 onward).

In Rerum Novarum

(1891), Leo criticized the concentration of wealth and power, spoke out against the abuses that workers faced and demanded that workers should be granted certain rights and safety regulations. He upheld the right of voluntary association, specifically commending labor unions. At the same time, he reiterated the Church’s defense of private property, condemned socialism, and emphasized the need for Catholics to form and join unions that were not compromised by secular and revolutionary ideologies.

Rerum Novarum provided new impetus for Catholics to become active in the labor movement, even if its exhortation to form specifically Catholic labor unions was widely interpreted as irrelevant to the pluralist context of the United States. While atheism underpinned many European unions and stimulated Catholic unionists to form separate labor federations, the religious neutrality of unions in the U.S. provided no such impetus. American Catholics seldom dominated unions, but they exerted influence across organized labor. Catholic union members and leaders played important roles in steering American unions away from socialism.

legal case

that tested the Butler Act

, which made it unlawful, in any state-funded educational establishment in Tennessee

, "to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation

of man as taught in the Bible

, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals." This is often interpreted as meaning that the law forbade the teaching of any aspect of the theory of evolution

. The case was a critical turning point in the United States' creation-evolution controversy

.

After the passage of the Butler Act, the American Civil Liberties Union

financed a test case, where a Dayton, Tennessee

high school teacher named John Scopes intentionally violated the Act. Scopes was charged on May 5, 1925 with teaching evolution from a chapter in a textbook which showed ideas developed from those set out in Charles Darwin's book On the Origin of Species. The trial pitted two of the pre-eminent legal minds of the time against one another; three-time presidential candidate, Congressman and former Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan

headed up the prosecution and prominent trial attorney Clarence Darrow

spoke for the defense. The famous trial was made infamous by the fictionalized accounts given in the 1955 play Inherit the Wind

, the 1960 film adaptation

, and the 1965

, 1988

, and 1999

television films of the same title.

wing of Protestant denominations, especially those that are more exclusively evangelical, and a corresponding decline in the mainstream liberal churches.

The 1950s saw a boom in the Evangelical church in America. The post–World War II prosperity experienced in the U.S. also had its effects on the church. Church buildings were erected in large numbers, and the Evangelical church's activities grew along with this expansive physical growth. In the southern U.S., the Evangelicals, represented by leaders such as Billy Graham

, have experienced a notable surge displacing the caricature of the pulpit pounding country preachers of fundamentalism. The stereotypes have gradually shifted.

Evangelicals are as diverse as the names that appear: Billy Graham

, Chuck Colson, J. Vernon McGee, or Jimmy Carter

— or even Evangelical institutions such as Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary (Boston) or Trinity Evangelical Divinity School

(Chicago). Although there exists a diversity in the Evangelical community worldwide, the ties that bind all Evangelicals are still apparent: a "high view" of Scripture, belief in the Deity of Christ, the Trinity, salvation by grace through faith, and the bodily resurrection of Christ, to mention a few.

arose and developmented in 20th-century Christianity

. The Pentecostal movement had its roots in the Pietism

and the Holiness movement

, and arose out of the meetings in 1906 at an urban mission on Azusa Street Revival in Los Angeles

, California

The Azusa Street Revival

and was led by William J. Seymour

, an African American

preacher and began with a meeting on April 14, 1906 at the African Methodist Episcopal Church

and continued until roughly 1915. The revival was characterized by ecstatic spiritual experiences accompanied by speaking in tongues

, dramatic worship services, and inter-racial mingling. It was the primary catalyst for the rise of Pentecostalism

, and as spread by those who experienced what they believed to be miraculous moves of God there.

Many Pentecostals embrace the term Evangelical

, while others prefer "Restorationist". Within classical Pentecostalism there are three major orientations: Wesleyan

-Holiness

, Higher Life

, and Oneness.

Pentecostalism would later birth the Charismatic movement

within already established denominations; some Pentecostals use the two terms interchangeably. Pentecostalism claims more than 250 million adherents worldwide. When Charismatics are added with Pentecostals the number increases to nearly a quarter of the world's 2 billion Christians.

, Poland, and Latin America

, especially from Mexico. This multiculturalism

and diversity has greatly impacted the flavor of Catholicism in the United States. For example, many dioceses serve in both the English language

and the Spanish language

.

Many of the Orthodox church movements in the West are fragmented under what is called jurisdictionalism. This is where the groups are divided up by ethnicity as the unifying character to each movement. As the older ethnic laity become aged and die off more and more of the churches are opening to new converts. Ten years or so ago, these converts would have faced a daunting task in having to learn the language and culture of the respective Orthodox group in order to properly convert to Orthodoxy. In recent times many of the churches now perform their services in modern English or Spanish or Portuguese (depending on the Metropolitan

or district).

issued an ukase

(decree) that dioceses of the Church of Russia that were cut off from the governance of the highest Church authority (i.e. the Holy Synod and the Patriarch) should be managed independently until such time as normal relations with the highest Church authority could be resumed; and on this basis, the North American diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church (known as the "Metropolia") continued to exist in a de facto autonomous mode of self-governance. The financial hardship that beset the North American diocese as the result of the Russian Revolution resulted in a degree of administrative chaos, with the result that other national Orthodox communities in North America turned to the Churches in their respective homelands for pastoral care and governance.

A group of bishops who had left Russia in the wake of the Russian Civil War

gathered in Sremski-Karlovci

, Yugoslavia

, and adopted a pro-monarchist stand. The group further claimed to speak as a synod for the entire "free" Russian church. This group, which to this day includes a sizable portion of the Russian emigration, was formally dissolved in 1922 by Patriarch Tikhon, who then appointed metropolitans Platon and Evlogy as ruling bishops in America and Europe, respectively. Both of these metropolitans continued to entertain relations intermittently with the synod in Karlovci.

Between the World Wars the Metropolia coexisted and at times cooperated with an independent synod

later known as Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia

(ROCOR), sometimes also called the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad. The two groups eventually went their separate ways. ROCOR, which moved its headquarters to North America after the Second World War, claimed but failed to establish jurisdiction over all parishes of Russian origin in North America. The Metropolia, as a former diocese of the Russian Church, looked to the latter as its highest church authority, albeit one from which it was temporarily cut off under the conditions of the communist regime in Russia.

After World War II the Patriarchate of Moscow made unsuccessful attempts to regain control over these groups. After resuming communication with Moscow in early 1960s, and being granted autocephaly

in 1970, the Metropolia became known as the Orthodox Church in America

. However, recognition of this autocephalous status is not universal, as the Ecumenical Patriarch (under whom is the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America

) and some other jurisdictions have not officially accepted it. Nevertheless the Ecumenical Patriarch, the Patriarch of Moscow, and the other jurisdictions are in communion

the OCA

and ROCOR. The Patriarchate of Moscow thereby renounced its former canonical claims in the United States and Canada.

In 1950, the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA (usually identified as National Council of Churches

, or NCC) represented a dramatic expansion in the development of ecumenical cooperation. It was a merger of the Federal Council of Churches, the International Council of Religious Education, and several other interchurch ministries. Today, the NCC is a joint venture of 35 Christian

denominations in the United States with 100,000 local congregations and 45,000,000 adherents. Its member communions include Mainline Protestant, Orthodox

, African-American, Evangelical and historic Peace churches. The NCC took a prominent role in the Civil Rights movement, and fostered the publication of the widely-used Revised Standard Version of the Bible, followed by an updated New Revised Standard Version, the first translation to benefit from the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. The organization is headquartered in New York City, with a public policy office in Washington, DC. The NCC is related fraternally to hundreds of local and regional councils of churches, to other national councils across the globe, and to the World Council of Churches

. All of these bodies are independently governed.

Carl McIntire led in organizing the American Council of Christian Churches

(ACCC), now with 7 member bodies, in September 1941. It was a more militant and fundamentalist organization set up in opposition to what became the National Council of Churches. The organization is headquartered in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. The ACCC is related fraternally to the International Council of Christian Churches. McIntire invited the Evangelicals for United Action to join with them, but those who met in St. Louis declined the offer.

First meeting in Chicago, Illinois in 1941, a committee was formed with Wright as chairman.A national conference for United Action Among Evangelicals was called to meet in April 1942. The National Association of Evangelicals

was formed by a group of 147 people who met in St. Louis, Missouri on April 7–9, 1942. The organization was called the National Association of Evangelicals for United Action, soon shortened to the National Association of Evangelicals

(NEA). There are currently 60 denominations with about 45,000 churches in the organization. The organization is headquartered in Washington, D.C. The NEA is related fraternally the World Evangelical Fellowship.

In 1922, the Masonic Grand Lodge of Oregon sponsored a bill to require all school-age children to attend public schools. With support of the Klan and Democratic Governor Walter M. Pierce

, endorsed by the Klan, the Compulsory Education Act was passed by a vote of 115,506 to 103,685. Its primary purpose was to shut down Catholic schools in Oregon, but it also affected other private and military schools. The constitutionality of the law was challenged in court and ultimately struck down by the Supreme Court in Pierce v. Society of Sisters

(1925) before it went into effect.

The law caused outraged Catholics to organize locally and nationally for the right to send their children to Catholic schools. In Pierce v. Society of Sisters

(1925), the United States Supreme Court declared the Oregon's Compulsory Education Act unconstitutional in a ruling that that has been called "the Magna Carta of the parochial school system."

Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. was but one of many notable Black ministers involved in the movement. He helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

(1957), serving as its first president. King received the Nobel Peace Prize

for his efforts to end segregation

and racial discrimination

through non-violent

civil disobedience

. He was assassinated

in 1968.

Ralph David Abernathy, Bernard Lee

, Fred Shuttlesworth

, C.T. Vivian and Jesse Jackson

are among the many notable minister-activists. They were especially important during the later years of the movement in the 1950s and 1960s.

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

as it was colonized by Europeans

European colonization of the Americas

The start of the European colonization of the Americas is typically dated to 1492. The first Europeans to reach the Americas were the Vikings during the 11th century, who established several colonies in Greenland and one short-lived settlement in present day Newfoundland...

beginning in the 16th

Christianity in the 16th century

- Age of Discovery :During the Age of Discovery, the Roman Catholic Church established a number of Missions in the Americas and other colonies in order to spread Christianity in the New World and to convert the indigenous peoples...

and 17th centuries

Christianity in the 17th century

The history of Christianity in the 17th century showed both deep conflict and new tolerance. The Enlightenment grew to challenge Christianity as a whole, generally elevated human reason above divine revelation, and down-graded religious authorities such as the Papacy based on it...

. The Spanish

Spanish people

The Spanish are citizens of the Kingdom of Spain. Within Spain, there are also a number of vigorous nationalisms and regionalisms, reflecting the country's complex history....

, French

French people

The French are a nation that share a common French culture and speak the French language as a mother tongue. Historically, the French population are descended from peoples of Celtic, Latin and Germanic origin, and are today a mixture of several ethnic groups...

, and British

British people

The British are citizens of the United Kingdom, of the Isle of Man, any of the Channel Islands, or of any of the British overseas territories, and their descendants...

brought Roman Catholicism to the colonies of New Spain

New Spain

New Spain, formally called the Viceroyalty of New Spain , was a viceroyalty of the Spanish colonial empire, comprising primarily territories in what was known then as 'América Septentrional' or North America. Its capital was Mexico City, formerly Tenochtitlan, capital of the Aztec Empire...

, New France

New France

New France was the area colonized by France in North America during a period beginning with the exploration of the Saint Lawrence River by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Spain and Great Britain in 1763...

and Maryland respectively, while Northern European peoples introduced Protestantism

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

to Massachusetts Bay Colony

Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was an English settlement on the east coast of North America in the 17th century, in New England, situated around the present-day cities of Salem and Boston. The territory administered by the colony included much of present-day central New England, including portions...

, New Netherland

New Netherland

New Netherland, or Nieuw-Nederland in Dutch, was the 17th-century colonial province of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands on the East Coast of North America. The claimed territories were the lands from the Delmarva Peninsula to extreme southwestern Cape Cod...

, Virginia colony, Carolina Colony, Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada. Situated in the country's Atlantic region, it incorporates the island of Newfoundland and mainland Labrador with a combined area of . As of April 2011, the province's estimated population is 508,400...

, and Lower Canada

Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence...

. Among Protestants, adherents to Anglicanism

Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a tradition within Christianity comprising churches with historical connections to the Church of England or similar beliefs, worship and church structures. The word Anglican originates in ecclesia anglicana, a medieval Latin phrase dating to at least 1246 that means the English...

, the Baptist Church, Congregationalism

Congregational church

Congregational churches are Protestant Christian churches practicing Congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its own affairs....

, Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism

Presbyterianism refers to a number of Christian churches adhering to the Calvinist theological tradition within Protestantism, which are organized according to a characteristic Presbyterian polity. Presbyterian theology typically emphasizes the sovereignty of God, the authority of the Scriptures,...

, Lutheranism

Lutheranism

Lutheranism is a major branch of Western Christianity that identifies with the theology of Martin Luther, a German reformer. Luther's efforts to reform the theology and practice of the church launched the Protestant Reformation...

, Quakerism, Mennonite

Mennonite

The Mennonites are a group of Christian Anabaptist denominations named after the Frisian Menno Simons , who, through his writings, articulated and thereby formalized the teachings of earlier Swiss founders...

and Moravian Church were the first to settle to the US, spreading their faith in the new country.

Today most Christians in the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

are Mainline Protestant, Evangelical

Evangelicalism

Evangelicalism is a Protestant Christian movement which began in Great Britain in the 1730s and gained popularity in the United States during the series of Great Awakenings of the 18th and 19th century.Its key commitments are:...

, or Roman Catholic.

Early Colonial era

Because the Spanish were the first Europeans to establish settlements on the mainland of North AmericaSpanish colonization of the Americas

Colonial expansion under the Spanish Empire was initiated by the Spanish conquistadores and developed by the Monarchy of Spain through its administrators and missionaries. The motivations for colonial expansion were trade and the spread of the Christian faith through indigenous conversions...

, such as St. Augustine, Florida

St. Augustine, Florida

St. Augustine is a city in the northeast section of Florida and the county seat of St. Johns County, Florida, United States. Founded in 1565 by Spanish explorer and admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, it is the oldest continuously occupied European-established city and port in the continental United...

in 1565, the earliest Christians in the territory which would eventually become the United States were Roman Catholics. However, the territory that would become the Thirteen Colonies

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies were English and later British colonies established on the Atlantic coast of North America between 1607 and 1733. They declared their independence in the American Revolution and formed the United States of America...

in 1776 was largely populated by Protestants due to Protestant settlers seeking religious freedom from the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

(est. 1534). These settlers were primarily Puritans from East Anglia

East Anglia

East Anglia is a traditional name for a region of eastern England, named after an ancient Anglo-Saxon kingdom, the Kingdom of the East Angles. The Angles took their name from their homeland Angeln, in northern Germany. East Anglia initially consisted of Norfolk and Suffolk, but upon the marriage of...

, especially just before the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

(1641–1651); there were also some Anglicans and Catholics but these were far fewer in number. Because of the predominance of Protestants among those coming from England, the English colonies

British colonization of the Americas

British colonization of the Americas began in 1607 in Jamestown, Virginia and reached its peak when colonies had been established throughout the Americas...

became almost entirely Protestant by the time of the American Revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

.

Spanish missions

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

(1517) with the Spanish conquistadors and settlers in present-day Florida

Florida

Florida is a state in the southeastern United States, located on the nation's Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the north by Alabama and Georgia and to the east by the Atlantic Ocean. With a population of 18,801,310 as measured by the 2010 census, it...

(1513) and the southwest. The first Christian worship service held in the current United States was a Catholic Mass celebrated in Pensacola, Florida.(St. Michael records) The Spanish spread Roman Catholicism through Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida

Spanish Florida refers to the Spanish territory of Florida, which formed part of the Captaincy General of Cuba, the Viceroyalty of New Spain, and the Spanish Empire. Originally extending over what is now the southeastern United States, but with no defined boundaries, la Florida was a component of...

by way of its mission system

Spanish missions in Florida

Beginning in the second half of the 16th century, the Kingdom of Spain established a number of missions throughout la Florida in order to convert the Indians to Christianity, to facilitate control of the area, and to prevent its colonization by other countries, in particular, England and France...

; these missions extended into Georgia

Spanish missions in Georgia

The Spanish missions in Georgia comprise a series of religious outposts established by Spanish Catholics in order to spread the Christian doctrine among the local Native Americans. The Spanish chapter of Georgia's earliest colonial history is dominated by the lengthy mission era, extending from...

and the Carolinas

Spanish missions in the Carolinas

The Spanish missions in the Carolinas were part of a series of religious outposts established by Spanish Catholics in order to spread the Christian doctrine among the local Native Americans...

. Eventually, Spain established missions in what are now Texas

Spanish missions in Texas

The Spanish Missions in Texas comprise a series of religious outposts established by Spanish Catholic Dominicans, Jesuits, and Franciscans to spread the Christian doctrine among the local Native Americans, but with the added benefit of giving Spain a toehold in the frontier land. The missions...

, New Mexico

Spanish missions in New Mexico

The Spanish Missions in New Mexico were a series of religious outposts established by Franciscan friars under charter from the governments of Spain and New Spain to convert the local Pueblo, Navajo and Apache Indians to Christianity. The missions also aimed to pacify and Hispanicize the natives...

, Arizona

Spanish missions in Arizona

Beginning in 1493, the Kingdom of Spain maintained a number of missions throughout Nueva España in order to facilitate colonization of these lands....

, and California

Spanish missions in California

The Spanish missions in California comprise a series of religious and military outposts established by Spanish Catholics of the Franciscan Order between 1769 and 1823 to spread the Christian faith among the local Native Americans. The missions represented the first major effort by Europeans to...

. Junípero Serra

Junípero Serra

Blessed Junípero Serra, O.F.M., , known as Fra Juníper Serra in Catalan, his mother tongue was a Majorcan Franciscan friar who founded the mission chain in Alta California of the Las Californias Province in New Spain—present day California, United States. Fr...

(d.1784) founded a series of missions in California which became important economic, political, and religious institutions. Overland routes were established from New Mexico that resulted in the colonization of San Francisco

San Francisco, California

San Francisco , officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the financial, cultural, and transportation center of the San Francisco Bay Area, a region of 7.15 million people which includes San Jose and Oakland...

in 1776 and Los Angeles

Los Angeles, California

Los Angeles , with a population at the 2010 United States Census of 3,792,621, is the most populous city in California, USA and the second most populous in the United States, after New York City. It has an area of , and is located in Southern California...

in 1781.

French territories

Mobile, Alabama

Mobile is the third most populous city in the Southern US state of Alabama and is the county seat of Mobile County. It is located on the Mobile River and the central Gulf Coast of the United States. The population within the city limits was 195,111 during the 2010 census. It is the largest...

, Biloxi, Baton Rouge, and New Orleans. In the late 17th century, French expeditions, which included sovereign, religious and commercial aims, established a foothold on the Mississippi River

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the largest river system in North America. Flowing entirely in the United States, this river rises in western Minnesota and meanders slowly southwards for to the Mississippi River Delta at the Gulf of Mexico. With its many tributaries, the Mississippi's watershed drains...

and Gulf Coast. With its first settlements, France lay claim to a vast region of North America and set out to establish a commercial empire and French nation stretching from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada.

The French colony of Louisiana

Louisiana (New France)

Louisiana or French Louisiana was an administrative district of New France. Under French control from 1682–1763 and 1800–03, the area was named in honor of Louis XIV, by French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle...

originally claimed all the land on both sides of the Mississippi River and the lands that drained into it. The following present day states were part of the then vast tract of Louisiana: Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota.

British colonies

Many of the British North American colonies that eventually formed the United States of America were settled in the 17th century by men and women, who, in the face of European religious persecutionReligious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group of individuals as a response to their religious beliefs or affiliations or lack thereof....

, refused to compromise passionately held religious convictions (largely stemming from the Protestant Reformation

Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation was a 16th-century split within Western Christianity initiated by Martin Luther, John Calvin and other early Protestants. The efforts of the self-described "reformers", who objected to the doctrines, rituals and ecclesiastical structure of the Roman Catholic Church, led...

which began c. 1517) and fled Europe.

New England

A group which later became known as the PilgrimsPilgrims

Pilgrims , or Pilgrim Fathers , is a name commonly applied to early settlers of the Plymouth Colony in present-day Plymouth, Massachusetts, United States...

settled the Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony was an English colonial venture in North America from 1620 to 1691. The first settlement of the Plymouth Colony was at New Plymouth, a location previously surveyed and named by Captain John Smith. The settlement, which served as the capital of the colony, is today the modern town...

in Plymouth, Massachusetts

Massachusetts

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts is a state in the New England region of the northeastern United States of America. It is bordered by Rhode Island and Connecticut to the south, New York to the west, and Vermont and New Hampshire to the north; at its east lies the Atlantic Ocean. As of the 2010...

in 1620, seeking refuge from conflicts in England which led up to the English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

.

The Puritans, a much larger group than the Pilgrims, established the Massachusetts Bay Colony

Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was an English settlement on the east coast of North America in the 17th century, in New England, situated around the present-day cities of Salem and Boston. The territory administered by the colony included much of present-day central New England, including portions...

in 1629 with 400 settlers. Puritans were English Protestants who wished to reform and purify the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

in the New World of what they considered to be unacceptable residues of Roman Catholicism. Within two years, an additional 2,000 settlers arrived. Beginning in 1630, as many as 20,000 Puritans emigrated to America from England to gain the liberty to worship as they chose. Most settled in New England, but some went as far as the West Indies. Theologically, the Puritans were "non-separating Congregationalist

Congregational church

Congregational churches are Protestant Christian churches practicing Congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its own affairs....

s". The Puritans created a deeply religious, socially tight-knit and politically innovative culture that is still present in the modern United States. They hoped this new land would serve as a "redeemer nation

Exceptionalism

Exceptionalism is the perception that a country, society, institution, movement, or time period is "exceptional" in some way and thus does not need to conform to normal rules or general principles...

".

The Salem witch trials

Salem witch trials

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings before county court trials to prosecute people accused of witchcraft in the counties of Essex, Suffolk, and Middlesex in colonial Massachusetts, between February 1692 and May 1693...

were a series of hearings before local magistrates followed by county court trial

Trial

A trial is, in the most general sense, a test, usually a test to see whether something does or does not meet a given standard.It may refer to:*Trial , the presentation of information in a formal setting, usually a court...

s to prosecute people accused of witchcraft

Witchcraft

Witchcraft, in historical, anthropological, religious, and mythological contexts, is the alleged use of supernatural or magical powers. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft...

in Essex

Essex County, Massachusetts

-National protected areas:* Parker River National Wildlife Refuge* Salem Maritime National Historic Site* Saugus Iron Works National Historic Site* Thacher Island National Wildlife Refuge-Demographics:...

, Suffolk

Suffolk County, Massachusetts

Suffolk County has no land border with Plymouth County to its southeast, but the two counties share a water boundary in the middle of Massachusetts Bay.-National protected areas:*Boston African American National Historic Site...

and Middlesex

Middlesex County, Massachusetts

-National protected areas:* Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge* Great Meadows National Wildlife Refuge* Longfellow National Historic Site* Lowell National Historical Park* Minute Man National Historical Park* Oxbow National Wildlife Refuge...

counties of colonial Massachusetts, between February 1692 and May 1693. Over 150 people were arrested and imprisoned, with even more accused but not formally pursued by the authorities. The two courts convicted twenty-nine people of the capital felony

Felony

A felony is a serious crime in the common law countries. The term originates from English common law where felonies were originally crimes which involved the confiscation of a convicted person's land and goods; other crimes were called misdemeanors...

of witchcraft. Nineteen of the accused, fourteen women and five men, were hanged. One man (Giles Corey

Giles Corey

Giles Corey was a prosperous farmer and full member of the church in early colonial America who died under judicial torture during the Salem witch trials. Corey refused to enter a plea, and was crushed to death by stone weights in an attempt to force him to do so...

) who refused to enter a plea was crushed to death under heavy stones in an attempt to force him to do so. At least five more of the accused died in prison.

Virginia

Virginia was settled by businessmen operating through a joint-stock company, the Virginia CompanyVirginia Company

The Virginia Company refers collectively to a pair of English joint stock companies chartered by James I on 10 April1606 with the purposes of establishing settlements on the coast of North America...

of London, who wanted to get rich. They also wanted the Church to flourish in their colony and kept it well supplied with ministers. Some early governors sent by the Virginia Company acted in the spirit of crusaders. During governor Thomas Dale

Thomas Dale

Sir Thomas Dale was an English naval commander and deputy-governor of the Virginia Colony in 1611 and from 1614 to 1616. Governor Dale is best remembered for the energy and the extreme rigour of his administration in Virginia, which established order and in various ways seems to have benefited the...

's tenure, religion was spread at the point of the sword. Everyone was required to attend church and be catechized by a minister. Those who refused could be executed or sent to the galleys.

When a popular assembly, the House of Burgesses

House of Burgesses

The House of Burgesses was the first assembly of elected representatives of English colonists in North America. The House was established by the Virginia Company, who created the body as part of an effort to encourage English craftsmen to settle in North America...

, was established in 1619, it enacted religious laws that "were a match for anything to be found in the Puritan societies." Unlike the colonies to the north, where the Church of England was regarded with suspicion throughout the colonial period, Virginia was a bastion of Anglicanism

Anglicanism

Anglicanism is a tradition within Christianity comprising churches with historical connections to the Church of England or similar beliefs, worship and church structures. The word Anglican originates in ecclesia anglicana, a medieval Latin phrase dating to at least 1246 that means the English...

.

The Church in Virginia faced problems unlike those confronted in other colonies—such as enormous parishes, some sixty miles long, and the inability to ordain ministers locally due to the lack of a bishop — but it continued to command the loyalty and affection of the colonists.

Tolerance in Rhode Island and Pennsylvania

Roger WilliamsRoger Williams (theologian)

Roger Williams was an English Protestant theologian who was an early proponent of religious freedom and the separation of church and state. In 1636, he began the colony of Providence Plantation, which provided a refuge for religious minorities. Williams started the first Baptist church in America,...

, who preached religious tolerance, separation of church and state, and a complete break with the Church of England, was banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony

Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was an English settlement on the east coast of North America in the 17th century, in New England, situated around the present-day cities of Salem and Boston. The territory administered by the colony included much of present-day central New England, including portions...

and founded Rhode Island Colony, which became a haven for other religious refugees from the Puritan community. Some migrants who came to Colonial America were in search of the freedom to practice forms of Christianity which were prohibited and persecuted in Europe. Since there was no state religion

State religion

A state religion is a religious body or creed officially endorsed by the state...

, in fact there was not yet a state

Sovereign state

A sovereign state, or simply, state, is a state with a defined territory on which it exercises internal and external sovereignty, a permanent population, a government, and the capacity to enter into relations with other sovereign states. It is also normally understood to be a state which is neither...

, and since Protestantism had no central authority, religious practice in the colonies became diverse.

The Religious Society of Friends

Religious Society of Friends