Timeline of zoology

Encyclopedia

A timeline

of the history of zoology.

.

Timeline

A timeline is a way of displaying a list of events in chronological order, sometimes described as a project artifact . It is typically a graphic design showing a long bar labeled with dates alongside itself and events labeled on points where they would have happened.-Uses of timelines:Timelines...

of the history of zoology.

Ancient world

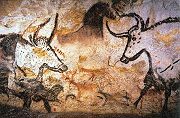

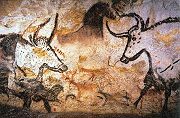

- 28000 BC. Cave painting (e.g. Chauvet CaveChauvet CaveThe Chauvet-Pont-d'Arc Cave is a cave in the Ardèche department of southern France that contains the earliest known cave paintings, as well as other evidence of Upper Paleolithic life. It is located near the commune of Vallon-Pont-d'Arc on a limestone cliff above the former bed of the Ardèche River...

) in Europe, especially Spain, depict animals in a stylized fashion. Can these paintings, showing animals as strong and important, be interpreted as veneration? MammothMammothA mammoth is any species of the extinct genus Mammuthus. These proboscideans are members of Elephantidae, the family of elephants and mammoths, and close relatives of modern elephants. They were often equipped with long curved tusks and, in northern species, a covering of long hair...

s (the same species later to be seen thawing from ice in Siberia) were depicted in these European cave paintings.

- 10000 BC. Man (Homo sapiens) domesticatedDomesticationDomestication or taming is the process whereby a population of animals or plants, through a process of selection, becomes accustomed to human provision and control. In the Convention on Biological Diversity a domesticated species is defined as a 'species in which the evolutionary process has been...

dogDogThe domestic dog is a domesticated form of the gray wolf, a member of the Canidae family of the order Carnivora. The term is used for both feral and pet varieties. The dog may have been the first animal to be domesticated, and has been the most widely kept working, hunting, and companion animal in...

s, pigPigA pig is any of the animals in the genus Sus, within the Suidae family of even-toed ungulates. Pigs include the domestic pig, its ancestor the wild boar, and several other wild relatives...

s, sheep, goatGoatThe domestic goat is a subspecies of goat domesticated from the wild goat of southwest Asia and Eastern Europe. The goat is a member of the Bovidae family and is closely related to the sheep as both are in the goat-antelope subfamily Caprinae. There are over three hundred distinct breeds of...

s, fowlFowlFowl is a word for birds in general but usually refers to birds belonging to one of two biological orders, namely the gamefowl or landfowl and the waterfowl...

, and other animals in Europe, northern Africa and the Near East.

- 6500 BC. The aurochsAurochsThe aurochs , the ancestor of domestic cattle, were a type of large wild cattle which inhabited Europe, Asia and North Africa, but is now extinct; it survived in Europe until 1627....

, ancestor of domestic cattleCattleCattle are the most common type of large domesticated ungulates. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae, are the most widespread species of the genus Bos, and are most commonly classified collectively as Bos primigenius...

, would be domesticated in the next two centuries if not earlier (Obre I, Yugoslavia). This fierce beast was the last major food animal to be tamed for use as a source of milk, meat, power, and leather in the Old WorldOld WorldThe Old World consists of those parts of the world known to classical antiquity and the European Middle Ages. It is used in the context of, and contrast with, the "New World" ....

.

- 3500 BC. SumerSumerSumer was a civilization and historical region in southern Mesopotamia, modern Iraq during the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age....

ian animal-drawn wheeled vehicles and plows are developed in MesopotamiaMesopotamiaMesopotamia is a toponym for the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, largely corresponding to modern-day Iraq, northeastern Syria, southeastern Turkey and southwestern Iran.Widely considered to be the cradle of civilization, Bronze Age Mesopotamia included Sumer and the...

, the region called the "Fertile CrescentFertile CrescentThe Fertile Crescent, nicknamed "The Cradle of Civilization" for the fact the first civilizations started there, is a crescent-shaped region containing the comparatively moist and fertile land of otherwise arid and semi-arid Western Asia. The term was first used by University of Chicago...

" by U.S. archaeologist James Henry BreastedJames Henry BreastedJames Henry Breasted was an American archaeologist and historian. After completing his PhD at the University of Berlin in 1894, he joined the faculty of the University of Chicago. In 1901 he became director of the Haskell Oriental Museum at the University of Chicago, where he continued to...

(1865–1935). IrrigationIrrigationIrrigation may be defined as the science of artificial application of water to the land or soil. It is used to assist in the growing of agricultural crops, maintenance of landscapes, and revegetation of disturbed soils in dry areas and during periods of inadequate rainfall...

may also have used animal power. By increasing the area under cultivation and reducing the number of people required to raise food, society will permit a few people to become priests, artisans, scholars, and merchants. Since Sumeria had no natural defenses, armies with mounted cavalryCavalryCavalry or horsemen were soldiers or warriors who fought mounted on horseback. Cavalry were historically the third oldest and the most mobile of the combat arms...

and chariotChariotThe chariot is a type of horse carriage used in both peace and war as the chief vehicle of many ancient peoples. Ox carts, proto-chariots, were built by the Proto-Indo-Europeans and also built in Mesopotamia as early as 3000 BC. The original horse chariot was a fast, light, open, two wheeled...

s became imperative and were a scourge upon the land they purported to protect. Civilization was thus built on the backs of equines (horseHorseThe horse is one of two extant subspecies of Equus ferus, or the wild horse. It is a single-hooved mammal belonging to the taxonomic family Equidae. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million years from a small multi-toed creature into the large, single-toed animal of today...

s and assDonkeyThe donkey or ass, Equus africanus asinus, is a domesticated member of the Equidae or horse family. The wild ancestor of the donkey is the African Wild Ass, E...

es).

- 2000 BC. Domestication of the silkworm in China.

- 1100 BC. Won Chang (China), first of the ChouZhou DynastyThe Zhou Dynasty was a Chinese dynasty that followed the Shang Dynasty and preceded the Qin Dynasty. Although the Zhou Dynasty lasted longer than any other dynasty in Chinese history, the actual political and military control of China by the Ji family lasted only until 771 BC, a period known as...

emperors, stocked his imperial zoological gardenZooA zoological garden, zoological park, menagerie, or zoo is a facility in which animals are confined within enclosures, displayed to the public, and in which they may also be bred....

with deer, goats, birds and fish from many parts of the world. Like zoos today, the animals may have been seen as exotic, alien, and possibly threatening. The emperor also enjoyed sporting events with the use of animals.

- 850 BC. HomerHomerIn the Western classical tradition Homer , is the author of the Iliad and the Odyssey, and is revered as the greatest ancient Greek epic poet. These epics lie at the beginning of the Western canon of literature, and have had an enormous influence on the history of literature.When he lived is...

(GreekGreeksThe Greeks, also known as the Hellenes , are a nation and ethnic group native to Greece, Cyprus and neighboring regions. They also form a significant diaspora, with Greek communities established around the world....

), reputedly a blind poet, wrote the epics IliadIliadThe Iliad is an epic poem in dactylic hexameters, traditionally attributed to Homer. Set during the Trojan War, the ten-year siege of the city of Troy by a coalition of Greek states, it tells of the battles and events during the weeks of a quarrel between King Agamemnon and the warrior Achilles...

and OdysseyOdysseyThe Odyssey is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is, in part, a sequel to the Iliad, the other work ascribed to Homer. The poem is fundamental to the modern Western canon, and is the second—the Iliad being the first—extant work of Western literature...

. Both contain animals as monsterMonsterA monster is any fictional creature, usually found in legends or horror fiction, that is somewhat hideous and may produce physical harm or mental fear by either its appearance or its actions...

s and metaphorMetaphorA metaphor is a literary figure of speech that uses an image, story or tangible thing to represent a less tangible thing or some intangible quality or idea; e.g., "Her eyes were glistening jewels." Metaphor may also be used for any rhetorical figures of speech that achieve their effects via...

s (gross soldiers turned into pigs by the witch CirceCirceIn Greek mythology, Circe is a minor goddess of magic , described in Homer's Odyssey as "The loveliest of all immortals", living on the island of Aeaea, famous for her part in the adventures of Odysseus.By most accounts, Circe was the daughter of Helios, the god of the sun, and Perse, an Oceanid...

), but also some correct observations on bees and fly maggots. Both epics make reference to muleMuleA mule is the offspring of a male donkey and a female horse. Horses and donkeys are different species, with different numbers of chromosomes. Of the two F1 hybrids between these two species, a mule is easier to obtain than a hinny...

s. The ancient Greeks considered horses so highly that they "hybridized" them with humans, to form boisterous centaurCentaurIn Greek mythology, a centaur or hippocentaur is a member of a composite race of creatures, part human and part horse...

s. At any rate, animals are used as metaphors and moral symbols by Homer to make a timeless story.

- 610 BC. AnaximanderAnaximanderAnaximander was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher who lived in Miletus, a city of Ionia; Milet in modern Turkey. He belonged to the Milesian school and learned the teachings of his master Thales...

(Greek, 610 BC–545 BC) was a student of Thales of Miletus. The first life, he taught, was formed by spontaneous generationSpontaneous generationSpontaneous generation or Equivocal generation is an obsolete principle regarding the origin of life from inanimate matter, which held that this process was a commonplace and everyday occurrence, as distinguished from univocal generation, or reproduction from parent...

in the mud. Later animals came into being by transmutations, left the water, and reached dry land. Man was derived from lower animals, probably aquatic. His writings, especially his poem On Nature, were read and cited by AristotleAristotleAristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

and other later philosophers, but are lost.

- 563? BC. BuddhaGautama BuddhaSiddhārtha Gautama was a spiritual teacher from the Indian subcontinent, on whose teachings Buddhism was founded. In most Buddhist traditions, he is regarded as the Supreme Buddha Siddhārtha Gautama (Sanskrit: सिद्धार्थ गौतम; Pali: Siddhattha Gotama) was a spiritual teacher from the Indian...

(Indian, 563?–483 BC) had gentle ideas on the treatment of animals. Animals are held to have intrinsic worth, not just the values they derive from their usefulness to man.

- 500 BC. EmpedoclesEmpedoclesEmpedocles was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a citizen of Agrigentum, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for being the originator of the cosmogenic theory of the four Classical elements...

of Agrigentum (Greek, 504–433 BC) reportedly rid a town of malariaMalariaMalaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease of humans and other animals caused by eukaryotic protists of the genus Plasmodium. The disease results from the multiplication of Plasmodium parasites within red blood cells, causing symptoms that typically include fever and headache, in severe cases...

by draining nearby swamps. He proposed the theory of the four humors and a natural origin of living things.

- 500 BC. AlcmaeonAlcmaeon of CrotonAlcmaeon of Croton was one of the most eminent natural philosophers and medical theorists of antiquity. His father's name was Peirithus . He is said by some to have been a pupil of Pythagoras, and he may have been born around 510 BC...

(Greek, ca. 500 BC) performed human dissections. He identified the optic nerve, distinguished between veins and arteries, and showed that the nose was not connected to the brain. He made much of the tongue and explained how it functioned. He also gave an explanation for semen and for sleep.

- 500 BC. XenophanesXenophanesof Colophon was a Greek philosopher, theologian, poet, and social and religious critic. Xenophanes life was one of travel, having left Ionia at the age of 25 he continued to travel throughout the Greek world for another 67 years. Some scholars say he lived in exile in Siciliy...

(Greek, 576–460 BC), a disciple of PythagorasPythagorasPythagoras of Samos was an Ionian Greek philosopher, mathematician, and founder of the religious movement called Pythagoreanism. Most of the information about Pythagoras was written down centuries after he lived, so very little reliable information is known about him...

(?–497 BC), first recognized fossils as animal remains and inferred that their presence on mountains indicated the latter had once been beneath the sea. "If horses or oxen had hands and could draw or make statues, horses would represent the forms of gods as horses, oxen as oxen." GalenGalenAelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus , better known as Galen of Pergamon , was a prominent Roman physician, surgeon and philosopher...

(130?–201?) revived interest in fossils that had been rejected by Aristotle, and the speculations of Xenophanes were again viewed with favor.

- 470 BC. DemocritusDemocritusDemocritus was an Ancient Greek philosopher born in Abdera, Thrace, Greece. He was an influential pre-Socratic philosopher and pupil of Leucippus, who formulated an atomic theory for the cosmos....

of Abdera (Greek, 470–370 BC) made dissections of many animals and humans. He was the first Greek philosopher-scientist to propose a classification of animals, dividing them into blooded animals (Vertebrata) and bloodless animals (Evertebrata). He also held that lower animals had perfected organs and that the brain was the seat of thought.

- 460 BC. HippocratesHippocratesHippocrates of Cos or Hippokrates of Kos was an ancient Greek physician of the Age of Pericles , and is considered one of the most outstanding figures in the history of medicine...

(Greek, 460?–377? BC), the "Father of Medicine", used animal dissections to advance human anatomy. Fifty books attributed to him were assembled in Alexandria in the Third Century BC. These probably represent the works of several authors, but the treatments given are usually conservative.

- 440 BC. HerodotusHerodotusHerodotus was an ancient Greek historian who was born in Halicarnassus, Caria and lived in the 5th century BC . He has been called the "Father of History", and was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a...

of Halikarnassos (Greek, 484–425 BC) treated exotic fauna in his Historia, but his accounts are often based on tall tales. He explored the Nile, but much of ancient Egyptian civilization was already lost to living memory by his time.

- 384 BC. AristotleAristotleAristotle was a Greek philosopher and polymath, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. His writings cover many subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry, theater, music, logic, rhetoric, linguistics, politics, government, ethics, biology, and zoology...

(Greek, 384–322 BC) studied under PlatoPlatoPlato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

, but he was not reluctant to disagree with the master. His books Historia Animalium (9 books), , and set the zoological stage for centuries. He emphasized the value of direst observation, recognized law and order in biological phenomena, and derived conclusions inductively from observed facts. He believed that there was a natural scale that ran from simple to complex. He made advances in the area of marine biology, basing his writings on keen observation and rational interpretation as well as conversations with local Lesbos fishermen for two years, beginning in 344 BC. His account of male protection of eggs by the barking catfish was scorned for centuries until Louis Agassiz confirmed Aristotle's description. Aristotle's botanical works are lost, but those of his botanical student Theophrastos of Eresos (372–288 BC) are still available (Inquiry into Plants).

- 340 BC. PlatoPlatoPlato , was a Classical Greek philosopher, mathematician, student of Socrates, writer of philosophical dialogues, and founder of the Academy in Athens, the first institution of higher learning in the Western world. Along with his mentor, Socrates, and his student, Aristotle, Plato helped to lay the...

(Greek, 427–347 BC) held that animals existed to serve man, but they should not be mistreated because this would lead people to mistreat other people. Others who have echoed this opinion are St. Thomas AquinasThomas AquinasThomas Aquinas, O.P. , also Thomas of Aquin or Aquino, was an Italian Dominican priest of the Catholic Church, and an immensely influential philosopher and theologian in the tradition of scholasticism, known as Doctor Angelicus, Doctor Communis, or Doctor Universalis...

, Immanuel KantImmanuel KantImmanuel Kant was a German philosopher from Königsberg , researching, lecturing and writing on philosophy and anthropology at the end of the 18th Century Enlightenment....

, and Albert SchweitzerAlbert SchweitzerAlbert Schweitzer OM was a German theologian, organist, philosopher, physician, and medical missionary. He was born in Kaysersberg in the province of Alsace-Lorraine, at that time part of the German Empire...

.

- 323 BC. Alexander the Great (Macedonian, 356–323 BC) collected animals, some perhaps for his old teacher Aristotle, when he was not busy conquering the known world. He is credited with the introduction of the peacock into Europe. Aside from its decorative tail feathers, the peacock (a pheasant) was eaten regularly by Europeans until the arrival of the turkey. (CharlemagneCharlemagneCharlemagne was King of the Franks from 768 and Emperor of the Romans from 800 to his death in 814. He expanded the Frankish kingdom into an empire that incorporated much of Western and Central Europe. During his reign, he conquered Italy and was crowned by Pope Leo III on 25 December 800...

is said to have served thousands at a single bash.)

- 95 BC. LucretiusLucretiusTitus Lucretius Carus was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is an epic philosophical poem laying out the beliefs of Epicureanism, De rerum natura, translated into English as On the Nature of Things or "On the Nature of the Universe".Virtually no details have come down concerning...

(Titus Lucretius Carus) (Roman, 96?–55 BC) spent his whole life writing one poem (still unfinished), called De Rerum Natura, with a version of the atomic theory, a theory of heredity, etc.

- 70 BC. Publius Vergilius Maro (VirgilVirgilPublius Vergilius Maro, usually called Virgil or Vergil in English , was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He is known for three major works of Latin literature, the Eclogues , the Georgics, and the epic Aeneid...

) (70–19 BC) was a famous Roman poet. His poems Bucolics (42–37 BC) and Georgics (37–30 BC) hold much information on animal husbandry and farm life. His Aeneid (published posthumously) has many references to the zoology of his time.

- 36 BC. Marcus Terentius VarroVarroVarro was a Roman cognomen carried by:*Marcus Terentius Varro, sometimes known as Varro Reatinus, the scholar*Publius Terentius Varro or Varro Atacinus, the poet*Gaius Terentius Varro, the consul defeated at the battle of Cannae...

(116–27 BC) wrote , a treatise that includes apiculture. He also treated the problem of sterility in the mule and recorded a rare instance in which a fertile mule was bred.

- 50. Lucius Annaeus SenecaSeneca the YoungerLucius Annaeus Seneca was a Roman Stoic philosopher, statesman, dramatist, and in one work humorist, of the Silver Age of Latin literature. He was tutor and later advisor to emperor Nero...

(Roman, 4 BC–AD 65), tutor to Roman emperor NeroNeroNero , was Roman Emperor from 54 to 68, and the last in the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Nero was adopted by his great-uncle Claudius to become his heir and successor, and succeeded to the throne in 54 following Claudius' death....

, maintained that animals have no reason, just instinct, a "stoic" position. He remarked on the ability of glass globes filled with water to magnify small objects.

- 77. Pliny the ElderPliny the ElderGaius Plinius Secundus , better known as Pliny the Elder, was a Roman author, naturalist, and natural philosopher, as well as naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and personal friend of the emperor Vespasian...

(Roman, 23–79) wrote his in 37 volumes. This work is a catch-all of zoological folklore, superstitions, and some good observations.

- 79. Pliny the YoungerPliny the YoungerGaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus, born Gaius Caecilius or Gaius Caecilius Cilo , better known as Pliny the Younger, was a lawyer, author, and magistrate of Ancient Rome. Pliny's uncle, Pliny the Elder, helped raise and educate him...

(Roman, 62–113), nephew of Pliny the Elder, inherited his uncle's notes and wrote on beekeeping.

- 100. PlutarchPlutarchPlutarch then named, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus , c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia...

(Roman, 46?–120) stated that animals' behavior is motivated by reason and understanding. Life of the ant mirrors the virtues of friendship, sociability, endurance, courage, moderation, prudence, and justice.

- 131. GalenGalenAelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus , better known as Galen of Pergamon , was a prominent Roman physician, surgeon and philosopher...

of Pergamum (Greek, 131?–201?), physician to Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, wrote on human anatomy from dissections of animals. His texts were used for hundreds of years, gaining the reputation of infallibility.

- 200 ca. Various compilers in post-classical and medieval times added to the (or, more popularly, the Bestiary), the major book on animals for hundreds of years. Animals were believed to exist in order to serve man, if not as food or slaves then as moral examples.

Middle Ages

- 600 ca. Isidorus Hispalensis (Spanish bishop of Seville) (560–636) wrote , a compendium on animals that served until the rediscovery of Aristotle and Pliny. Full of errors, it nevertheless was influential for hundreds of years. He also wrote .

- 781. Al-JahizAl-JahizAl-Jāḥiẓ was an Arabic prose writer and author of works of literature, Mu'tazili theology, and politico-religious polemics.In biology, Al-Jahiz introduced the concept of food chains and also proposed a scheme of animal evolution that entailed...

(Afro-Arab, 781–868/869), a scholar at BasraBasraBasra is the capital of Basra Governorate, in southern Iraq near Kuwait and Iran. It had an estimated population of two million as of 2009...

, wrote on the influence of environment on animals.

- 901. HorseHorseThe horse is one of two extant subspecies of Equus ferus, or the wild horse. It is a single-hooved mammal belonging to the taxonomic family Equidae. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million years from a small multi-toed creature into the large, single-toed animal of today...

s came into wider use in those parts of Europe where the three-field system produces grain surpluses for feed, but hay-fed oxOxAn ox , also known as a bullock in Australia, New Zealand and India, is a bovine trained as a draft animal. Oxen are commonly castrated adult male cattle; castration makes the animals more tractable...

en were more economical, if less efficient, in terms of time and labor and remained almost the sole source of animal power in southern Europe, where most farmers continued to use the two-field system.

- 1114. Gerard of CremonaGerard of CremonaGerard of Cremona was an Italian translator of Arabic scientific works found in the abandoned Arab libraries of Toledo, Spain....

(1114–1187), after the capture of ToledoToledo, SpainToledo's Alcázar became renowned in the 19th and 20th centuries as a military academy. At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936 its garrison was famously besieged by Republican forces.-Economy:...

and its libraries from the Moors, translated Ptolemy, Aristotle, Euclid, Hippocrates, Galen, Pliny and many other classical authors from the Arabic.

- 1244–1248. Frederick IIFrederick II, Holy Roman EmperorFrederick II , was one of the most powerful Holy Roman Emperors of the Middle Ages and head of the House of Hohenstaufen. His political and cultural ambitions, based in Sicily and stretching through Italy to Germany, and even to Jerusalem, were enormous...

von Hohenstaufen (Holy Roman Emperor) (1194–1250) wrote (The Art of Hunting with Birds) as a practical guide to ornithology. Hawking was the sport for royalty in those days.

- 1244. Vincentius Bellovacensis (Vincent of BeauvaisVincent of BeauvaisThe Dominican friar Vincent of Beauvais wrote the Speculum Maius, the main encyclopedia that was used in the Middle Ages.-Early life:...

) (?–1264) wrote (1244–1254), a major encyclopedia of the 13th century. This work comprises three huge volumes, of 80 books and 9,885 chapters.

- 1248. Thomas of CantimpréThomas of CantimpréThomas of Cantimpré was a Roman Catholic medieval writer, preacher, and theologian.-Biography:...

‚ (Fleming, 1204?–1275?) wrote , a major 13th century encyclopedia.

- 1254–1323. Marco PoloMarco PoloMarco Polo was a Venetian merchant traveler from the Venetian Republic whose travels are recorded in Il Milione, a book which did much to introduce Europeans to Central Asia and China. He learned about trading whilst his father and uncle, Niccolò and Maffeo, travelled through Asia and apparently...

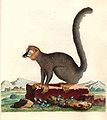

(Italian, 1254–1323) provided information on Asiatic fauna, revealing new animals to Europeans. "Unicorns" (rhinos?) were reported from southern China, but fantastic animals were otherwise not included.

- 1255–1270. Albertus MagnusAlbertus MagnusAlbertus Magnus, O.P. , also known as Albert the Great and Albert of Cologne, is a Catholic saint. He was a German Dominican friar and a bishop, who achieved fame for his comprehensive knowledge of and advocacy for the peaceful coexistence of science and religion. Those such as James A. Weisheipl...

of Cologne (Bavarian, 1206?–1280) (Albert von Bollstaedt or St. Albert) wrote . He promoted Aristotle but also included new material on the perfection and intelligence of animals, especially bees.

- 1304–1309. Petrus de CrescentiiPietro CrescenziPietro de' Crescenzi was an Italian jurist from Bologna, now known as a writer on agriculture. Educated at the University of Bologna in logic, medicine, the natural sciences and law, Crescenzi practiced as a lawyer and judge from about 1269 until 1299...

wrote , a practical manual for agriculture with many accurate observations on insects and other animals. Apiculture was discussed at length.

- 1453. The fall of ConstantinopleConstantinopleConstantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

to the Turks ended the Byzantine EmpireByzantine EmpireThe Byzantine Empire was the Eastern Roman Empire during the periods of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, centred on the capital of Constantinople. Known simply as the Roman Empire or Romania to its inhabitants and neighbours, the Empire was the direct continuation of the Ancient Roman State...

. Greek manuscripts became known in Europe, including books by Aristotle and Theophrastos that were translated into Latin by Theodore Gaza (Greek, ?–1478).

- 1492–1555. Edward Wotton (English, 1492–1555) wrote , a well thought-out work that influenced Gesner.

- 1492. Christopher ColumbusChristopher ColumbusChristopher Columbus was an explorer, colonizer, and navigator, born in the Republic of Genoa, in northwestern Italy. Under the auspices of the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, he completed four voyages across the Atlantic Ocean that led to general European awareness of the American continents in the...

(Italian) arrives in the New World. New animals soon begin to overload European zoology. Columbus is said to have introduced cattle, horses, and eight pigs from the Canary Islands to Hispaniola in 1493, giving rise to virtual devastation of that and other islands. Pigs were often set ashore by sailors to provide food on the ship's later return. Feral populations of hogs were often dangerous to humans.

- 1500 ca. ParacelsusParacelsusParacelsus was a German-Swiss Renaissance physician, botanist, alchemist, astrologer, and general occultist....

(Theophrastus Bambastus von Hohenheim) (Swiss or German?, 1493–1541), alchemist, wrote that poisons should be used against disease: he recommended mercury for treating syphilis.

- 1519–1520. Bernal Diaz del Castillo (Spanish, 1450?–1500), chronicler of Cortez's conquest of Mexico, commented on the zoological gardens of Aztec ruler MontezumaMoctezuma IIMoctezuma , also known by a number of variant spellings including Montezuma, Moteuczoma, Motecuhzoma and referred to in full by early Nahuatl texts as Motecuhzoma Xocoyotzin, was the ninth tlatoani or ruler of Tenochtitlan, reigning from 1502 to 1520...

(1466–1520), a marvel with parrots, rattlesnakes, etc.

- 1523. Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés(Spanish, 1478–1557), appointed official historiographer of the Indies in 1523, wrote Sumario de la Natural Historia delas Indias (Toledo, 1527). He was the first to describe many New World animals, such as the tapir, opossum, manatee, iguana, armadillo, ant-eaters, sloth, pelican, humming birds, etc.

Modern world

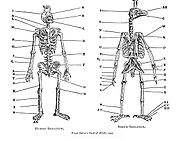

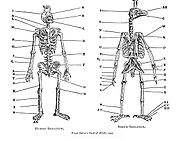

- 1551–1555. Pierre Belon (French, 1517–1564) wrote (1551) and (1555). This latter work included 110 animal species and offered many new observations and corrections to Herodotus. (1555) was his picture book, with improved animal classification and accurate anatomical drawings. In this he published a man's and a bird's skeleton side by side to show the resemblance. He discovered an armadillo shell in a market in Syria, showing how Islam was distributing the finds from the New World.

- 1551. Conrad GessnerConrad GessnerConrad Gessner was a Swiss naturalist and bibliographer. His five-volume Historiae animalium is considered the beginning of modern zoology, and the flowering plant genus Gesneria is named after him...

(Swiss, 1516–1565) wrote (Tiguri, 4 vols., 1551–1558, last volume published in 1587) and gained renown. This work, although uncritically compiled in places, was consulted for over 200 years. He also wrote (1553) and (1563).

- 1554–1555. Guillaume RondeletGuillaume RondeletGuillaume Rondelet , known also as Rondeletus , was Regus Professor of medicine at the University of Montpellier in southern France and Chancellor of the University between 1556 and his death in 1566. He achieved renown as an anatomist and a naturalist with a particular interest in botany and zoology...

(French, 1507–1566) wrote (1554) and (1555). He gathered vernacular names in hope of being able to identify the animal in question. He did go to print with discoveries that disagreed with Aristotle.

- 1574. Johannes FaberGiovanni FaberGiovanni Faber was a German papal doctor, botanist and art collector, originally from Bamberg in Bavaria, who lived in Rome from 1598. He was curator of the Vatican botanical garden, a member and the secretary of the Accademia dei Lincei. He acted throughout his career as a political broker...

(1576–1629), an early entomologist and member of the Accademia dei LinceiAccademia dei LinceiThe Accademia dei Lincei, , is an Italian science academy, located at the Palazzo Corsini on the Via della Lungara in Rome, Italy....

in Rome, gave the microscopeMicroscopeA microscope is an instrument used to see objects that are too small for the naked eye. The science of investigating small objects using such an instrument is called microscopy...

its name.

- 1578. Jean de LeryJean de LéryJean de Léry was an explorer, writer and Reformed Pastor born in Lamargelle, Côte-d'Or, France. Little is known of his early life; and he might have remained unknown had he not accompanied a group of Protestants to their new colony on an island in the Bay of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil...

(French, 1534–1611) was a member of the French colony at Rio de Janeiro. He published (1578) with observations on the local fauna.

- 1585. Thomas HarriotThomas HarriotThomas Harriot was an English astronomer, mathematician, ethnographer, and translator. Some sources give his surname as Harriott or Hariot or Heriot. He is sometimes credited with the introduction of the potato to Great Britain and Ireland...

(English, 1560–1621) was a naturalist with the first attempted English colony in North America, on Roanoke Island, North Carolina. His Brief and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia (1590) describes the black bearAmerican black bearThe American black bear is a medium-sized bear native to North America. It is the continent's smallest and most common bear species. Black bears are omnivores, with their diets varying greatly depending on season and location. They typically live in largely forested areas, but do leave forests in...

, gray squirrelEastern Gray SquirrelThe eastern gray squirrel is a tree squirrel in the genus Sciurus native to the eastern and midwestern United States, and to the southerly portions of the eastern provinces of Canada...

, hare, otter, opossum, raccoonRaccoonProcyon is a genus of nocturnal mammals, comprising three species commonly known as raccoons, in the family Procyonidae. The most familiar species, the common raccoon , is often known simply as "the" raccoon, as the two other raccoon species in the genus are native only to the tropics and are...

, skunkSkunkSkunks are mammals best known for their ability to secrete a liquid with a strong, foul odor. General appearance varies from species to species, from black-and-white to brown or cream colored. Skunks belong to the family Mephitidae and to the order Carnivora...

, Virginia and mule deerMule DeerThe mule deer is a deer indigenous to western North America. The Mule Deer gets its name from its large mule-like ears. There are believed to be several subspecies, including the black-tailed deer...

, turkeysTurkey (bird)A turkey is a large bird in the genus Meleagris. One species, Meleagris gallopavo, commonly known as the Wild Turkey, is native to the forests of North America. The domestic turkey is a descendant of this species...

, horseshoe crabHorseshoe crabThe Atlantic horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus, is a marine chelicerate arthropod. Despite its name, it is more closely related to spiders, ticks, and scorpions than to crabs. Horseshoe crabs are most commonly found in the Gulf of Mexico and along the northern Atlantic coast of North America...

(Limulus), etc.

- 1589. José de AcostaJosé de AcostaJosé de Acosta was a Spanish 16th-century Jesuit missionary and naturalist in Latin America.-Life:...

(Spanish, 1539–1600) wrote (1589) and (1590), describing many previously unknown animals from the New World.

- 1600. In Italy a spider scare lead to hysteria and the tarantellaTarantellaThe term tarantella groups a number of different southern Italian couple folk dances characterized by a fast upbeat tempo, usually in 6/8 time , accompanied by tambourines. It is among the most recognized of traditional Italian music. The specific dance name varies with every region, for instance...

dance by which the body cures itself through physical exertions.

- 1602. Ulysses Aldrovandi (Italian, 1522–1605) wrote . This and his other works include much nonsense, but he used wing and leg morphology to construct his classification of insects. He is more highly regarded for his ornithological contributions.

- 1604–1614. Francisco Hernández de ToledoFrancisco Hernández de ToledoFrancisco Hernández de Toledo was a naturalist and court physician to the King of Spain....

(Spanish) was sent to study Mexican biota in 1593–1600, by Philip II of SpainPhilip II of SpainPhilip II was King of Spain, Portugal, Naples, Sicily, and, while married to Mary I, King of England and Ireland. He was lord of the Seventeen Provinces from 1556 until 1581, holding various titles for the individual territories such as duke or count....

. His notes were published in Mexico in 1604 and 1614, describing many animals for the first time: coyote, buffalo, axolotl, porcupine, pronghorn antelope, horned lizard, bison, peccary and the toucan. He also figured many animals for the first time: ocelot, rattlesnake, manatee, alligator, armadillo, and the pelican.

- 1607 (1612?). Captain John Smith (English), head of the Jamestown colony, wrote A Map of Virginia in which he describes the physical features of the country, its climate, plants and animals, and inhabitants. He describes the raccoon, muskrat, flying squirrel, as well as a score of animals, all well identifiable. (In 1609 the Jamestown, Virginia, colony was almost lost when settlers found that their stores had been devoured by rats from English ships.)

- 1617. Garcilasso de la Vega (Peruvian Spanish, 1539–1617) wrote Royal Commentaries of Peru, containing descriptions of the condorCondorCondor is the name for two species of New World vultures, each in a monotypic genus. They are the largest flying land birds in the Western Hemisphere.They are:* The Andean Condor which inhabits the Andean mountains....

, ocelotOcelotThe ocelot , pronounced /ˈɒsəˌlɒt/, also known as the dwarf leopard or McKenney's wildcat is a wild cat distributed over South and Central America and Mexico, but has been reported as far north as Texas and in Trinidad, in the Caribbean...

s, puma, viscachaViscachaViscachas or vizcachas are rodents of two genera in the family Chinchillidae. They are closely related to chinchillas, and look similar to rabbits...

, tapirTapirA Tapir is a large browsing mammal, similar in shape to a pig, with a short, prehensile snout. Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South America, Central America, and Southeast Asia. There are four species of Tapirs: the Brazilian Tapir, the Malayan Tapir, Baird's Tapir and the Mountain...

, rheaRhea (bird)The rheas are ratites in the genus Rhea, native to South America. There are two existing species: the Greater or American Rhea and the Lesser or Darwin's Rhea. The genus name was given in 1752 by Paul Möhring and adopted as the English common name. Möhring's reason for choosing this name, from the...

, skunkSkunkSkunks are mammals best known for their ability to secrete a liquid with a strong, foul odor. General appearance varies from species to species, from black-and-white to brown or cream colored. Skunks belong to the family Mephitidae and to the order Carnivora...

, llamaLlamaThe llama is a South American camelid, widely used as a meat and pack animal by Andean cultures since pre-Hispanic times....

, huanaco, pacaPacaThe Lowland Paca , also known as the Spotted Paca, is a large rodent found in tropical and sub-tropical America, from East-Central Mexico to Northern Argentina...

, and vicuñaVicuñaThe vicuña or vicugna is one of two wild South American camelids, along with the guanaco, which live in the high alpine areas of the Andes. It is a relative of the llama, and is now believed to share a wild ancestor with domesticated alpacas, which are raised for their fibre...

.

- 1620? North American colonists probably introduced the European honeybee, Apis mellifera, into Virginia. By the 1640s these insects were also in Massachusetts. They became feral and advanced through eastern North America before the settlers.

- 1628. William HarveyWilliam HarveyWilliam Harvey was an English physician who was the first person to describe completely and in detail the systemic circulation and properties of blood being pumped to the body by the heart...

(English, 1578–1657) published (1628) with the doctrine of the circulation of blood (an inference made by him in about 1616).

- 1634. William Wood (English) wrote New England Prospect (1634) in which he describes New England's fauna.

- 1637. Thomas Morton (English, c. 1579–1647) wrote New English Canaan (1637) with treatments of 26 species of mammals, 32 birds, 20 fishes and 8 marine invertebrates.

- 1648. Georg MarcgraveGeorg MarcgraveGeorg Marcgrave was a German naturalist and astronomer.- Life :Born in Liebstadt in the Electorate of Saxony, Marcgrave studied botany, astronomy, mathematics, and medicine in Germany and Switzerland until 1636 when he journeyed to Leiden in the Netherlands.In 1637, he was appointed astronomer of...

(?–1644) was a German astronomer working for Johann Moritz, Count Maurice of Nassau, in the Dutch colony set up in northeastern Brazil. His (1648) contains the best early descriptions of many Brazilian animals. Marcgrave used TupiTupian languagesThe Tupi or Tupian language family comprises some 70 languages spoken in South America, of which the best known are Tupi proper and Guarani.-History, members and classification:...

names that were later Latinized by Linnaeus in the 13th edition of the Systema Naturae. The biological and linguistic data could have come from Moraes, a Brazilian Jesuit priest turned apostate.

- 1651. William HarveyWilliam HarveyWilliam Harvey was an English physician who was the first person to describe completely and in detail the systemic circulation and properties of blood being pumped to the body by the heart...

published (1651) with the aphorism on the title page.

- 1661. Marcello MalpighiMarcello MalpighiMarcello Malpighi was an Italian doctor, who gave his name to several physiological features, like the Malpighian tubule system.-Early years:...

(Italian, 1628–1694) discovered capillaries (1661), structures predicted to exist by Harvey some thirty years earlier. Malpighi was the founder of microanatomy. He studied, among other things, the anatomy of the silkworm (1669) and the development of the chick (1672).

- 1662. John GrauntJohn GrauntJohn Graunt was one of the first demographers, though by profession he was a haberdasher. Born in London, the eldest of seven or eight children of Henry and Mary Graunt. His father was a draper who had moved to London from Hampshire...

(English) provided the beginnings of demography with his Natural and Political Observations ... made upon the Bills of Mortality (1662). His speculations on Adam's and Eve's descendants and their growth rates showed an understanding of geometrical population increase. He found that more males than females were born, a fact considered by Sir Matthew Hale as providential for the "needs of warfare".

- 1665. Robert HookeRobert HookeRobert Hooke FRS was an English natural philosopher, architect and polymath.His adult life comprised three distinct periods: as a scientific inquirer lacking money; achieving great wealth and standing through his reputation for hard work and scrupulous honesty following the great fire of 1666, but...

(English, 1635–1703) wrote Micrographia (1665, 88 plates), with his early microscopic studies. He coined the term "cell".

- 1668. Francesco RediFrancesco RediFrancesco Redi was an Italian physician, naturalist, and poet.-Biography:The son of Gregorio Redi and Cecilia de Ghinci was born in Arezzo on February 18, 1626. After schooling with the Jesuits, he attended the University of Pisa...

(Italian, 1621–1697) wrote (1668) and (1708). His refutation of spontaneous generation in flies is still considered a model in experimentation.

- 1669. Jan SwammerdamJan SwammerdamJan Swammerdam was a Dutch biologist and microscopist. His work on insects demonstrated that the various phases during the life of an insect—egg, larva, pupa, and adult—are different forms of the same animal. As part of his anatomical research, he carried out experiments on muscle contraction...

(Dutch, 1637–1680) wrote (1669) describing metamorphosis in insects and supporting the performation doctrine. He was a pioneer in microscopic studies. He gave the first description of red blood corpuscles and discovered the valves of lymph vessels. His work was unknown and unacknowledged until after his death.

- 1672. Regnier de GraafRegnier de GraafRegnier de Graaf, Dutch spelling Reinier de Graaf or latinized Reijnerus de Graeff was a Dutch physician and anatomist who made key discoveries in reproductive biology. His first name is often spelled Reinier or Reynier.-Biography:De Graaf was born in Schoonhoven and perhaps a relative to the De...

(1641–1673) reported that he had traced the human egg from the ovary down the fallopian tube to the uterus. What he really saw was the follicle.

- 1675–1722. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (Dutch, 1632–1723) wrote , a treatise with early observations made with microscopes. He discovered blood corpuscles, striated muscles, human spermatozoa (1677), protozoa (1674), bacteria (1683), rotifers, etc.

- 1691. John RayJohn RayJohn Ray was an English naturalist, sometimes referred to as the father of English natural history. Until 1670, he wrote his name as John Wray. From then on, he used 'Ray', after "having ascertained that such had been the practice of his family before him".He published important works on botany,...

(English, 1627–1705) wrote (1693), (1710), and The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation (1691). He tried to classify different animal species into groups largely according to their toes and teeth.

- 1699. Edward TysonEdward TysonEdward Tyson was a British scientist and physician, commonly regarded as the founder of modern comparative anatomy, which compares the anatomy between species....

(English, 1650–1708) wrote (or Anatomy of a Pygmie Compared with that of a Monkey, an Ape and a Man) (1699), his anatomical study of the primate. This was the first detailed and accurate study of the higher apes. Other studies by Tyson include the female porpoisePorpoisePorpoises are small cetaceans of the family Phocoenidae; they are related to whales and dolphins. They are distinct from dolphins, although the word "porpoise" has been used to refer to any small dolphin, especially by sailors and fishermen...

, male rattlesnakeRattlesnakeRattlesnakes are a group of venomous snakes of the genera Crotalus and Sistrurus of the subfamily Crotalinae . There are 32 known species of rattlesnake, with between 65-70 subspecies, all native to the Americas, ranging from southern Alberta and southern British Columbia in Canada to Central...

, tapeworm, roundworm (Ascaris), peccaryPeccaryA peccary is a medium-sized mammal of the family Tayassuidae, or New World Pigs. Peccaries are members of the artiodactyl suborder Suina, as are the pig family and possibly the hippopotamus family...

and opossum.

- 1700? Discovery of the platypusPlatypusThe platypus is a semi-aquatic mammal endemic to eastern Australia, including Tasmania. Together with the four species of echidna, it is one of the five extant species of monotremes, the only mammals that lay eggs instead of giving birth to live young...

in Australia.

- 1700. Félix de AzaraFélix de AzaraFélix Manuel de Azara was a Spanish military officer, naturalist and engineer. He was born in Barbunales, Aragon....

(Spanish) estimated the feral herds of cattle on the South American pampas at 48 million animals. These animals probably descended from herds introduced by the Jesuits some 100 years earlier. (North America and Australia were to follow in this pattern, where feral herds of cattle and mustangs would explode, become pests, and reform the frontier areas.)

- 1705. Maria Sybilla Merian (German, 1647–1717) wrote and beautifully illustrated her () (1705). In this book she stated that Fulgora lanternaria was luminous.

- 1730? Sir Hans SloaneHans SloaneSir Hans Sloane, 1st Baronet, PRS was an Ulster-Scot physician and collector, notable for bequeathing his collection to the British nation which became the foundation of the British Museum...

(English (born Ireland), 1660–1753) was a founder of the British MuseumBritish MuseumThe British Museum is a museum of human history and culture in London. Its collections, which number more than seven million objects, are amongst the largest and most comprehensive in the world and originate from all continents, illustrating and documenting the story of human culture from its...

.

- 1734–1742. René Antoine Ferchault de RéaumurRené Antoine Ferchault de RéaumurRené Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur was a French scientist who contributed to many different fields, especially the study of insects.-Life:Réaumur was born in a prominent La Rochelle family and educated in Paris...

(French, 1683–1756) was an early entomologist. His (6 volumes) shows the best of zoological observation at the time. He invented the glass-fronted bee hive.

- 1740. Abraham TrembleyAbraham TrembleyAbraham Trembley was a Swiss naturalist. He is best known for being the first to study freshwater polyps or hydra and for being among the first to develop experimental zoology...

, Swiss naturalist, discovered the hydraHydra (genus)Hydra is a genus of simple fresh-water animal possessing radial symmetry. Hydras are predatory animals belonging to the phylum Cnidaria and the class Hydrozoa. They can be found in most unpolluted fresh-water ponds, lakes, and streams in the temperate and tropical regions and can be found by...

which he considered to combine both animal and plant characteristics. His (1744) showed that freshwater polyps of Hydra could be sectioned or mutilated and still reform. Regeneration soon became a topic of inquiry among Réaumur, Bonnet, Spallanzini and others.

- 1745. Charles BonnetCharles BonnetCharles Bonnet , Swiss naturalist and philosophical writer, was born at Geneva, of a French family driven into Switzerland by the religious persecution in the 16th century.-Life and work:Bonnet's life was uneventful...

(French-Swiss, 1720–1793) wrote (1745) and (1732). He confirmed parthenogenesisParthenogenesisParthenogenesis is a form of asexual reproduction found in females, where growth and development of embryos occur without fertilization by a male...

of aphidAphidAphids, also known as plant lice and in Britain and the Commonwealth as greenflies, blackflies or whiteflies, are small sap sucking insects, and members of the superfamily Aphidoidea. Aphids are among the most destructive insect pests on cultivated plants in temperate regions...

s.

- 1745. Pierre Louis M. de Maupertius (French, 1698–1759) went to Lapland to measure the arc of the meridian (1736–1737). Maupertuis was a Newtonian. He generated family trees for inheritable characteristics (e.g., haemophilia in European royal families) and showed inheritance through both the male and female lines. He was an early evolutionist and head of the Berlin Academy of Sciences. In 1744 he proposed the theory that molecules from all parts of the body were gathered into the gonads (later called "pangenesis"). was published anonymously in 1745. Maupertuis wrote in which he suggests a survival of the fittest concept: "Could not one say that since, in the accidental combination of Nature's productions, only those could survive which found themselves provided with certain appropriate relationships, it is no wonder that these relationships are present in all the species that actually exist? These species which we see today are only the smallest part of those which a blind destiny produced."

- 1748. John Tuberville NeedhamJohn NeedhamJohn Turberville Needham FRS was an English biologist and Roman Catholic priest.He was first exposed to natural philosophy while in seminary school and later published a paper which, while the subject was mostly about geology, described the mechanics of pollen and won recognition in the botany...

, an English naturalist, wrote Observations upon the Generation, Composition, and Decomposition of Animal and Vegetable Substances in which he offers "proof" of spontaneous generation. Needham found flasks of broth teeming with "little animals" after having boiled them and sealed them, but his experimental techniques were faulty.

- 1748–1751. Peter Kalm (Swede) was a naturalist and student of Linnaeus. He traveled in North America (1748–1751).

.

- 1749–1804. Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de BuffonGeorges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de BuffonGeorges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon was a French naturalist, mathematician, cosmologist, and encyclopedic author.His works influenced the next two generations of naturalists, including Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and Georges Cuvier...

(French, 1707–1788) wrote (1749–1804 in 44 vols.) that had a great impact on zoology. He asserted that species were mutable. Buffon also drew attention to vestigial organs. He held that spermatozoa were "living organic molecules" that multiplied in the semen.

- 1758. Albrecht von HallerAlbrecht von HallerAlbrecht von Haller was a Swiss anatomist, physiologist, naturalist and poet.-Early life:He was born of an old Swiss family at Bern. Prevented by long-continued ill-health from taking part in boyish sports, he had the more opportunity for the development of his precocious mind...

(Swiss, 1708–1777) was one of the founders of modern physiology. His work on the nervous system was revolutionary. He championed animal physiology, along with human physiology. See his textbook (1758).

- 1758. Carl Linnaeus (Swedish, 1707–1778) published the whose tenth edition10th edition of Systema NaturaeThe 10th edition of Systema Naturae was a book written by Carl Linnaeus and published in two volumes in 1758 and 1759, which marks the starting point of zoological nomenclature...

(1758) is the starting point of binomial nomenclatureBinomial nomenclatureBinomial nomenclature is a formal system of naming species of living things by giving each a name composed of two parts, both of which use Latin grammatical forms, although they can be based on words from other languages...

for zoology.

- 1759. Caspar Friedrich WolffCaspar Friedrich WolffCaspar Friedrich Wolff was a German physiologist and one of the founders of embryology.-Life:Wolff was born in Berlin, Brandenburg. In 1230 he graduated as an M.D...

(1733–1794) wrote (1759) that disagreed with the idea of preformationPreformationismIn the history of biology, preformationism is either the specific contention that all organisms were created at the same time, and that succeeding generations grow from homunculi, animalcules, or other fully formed but miniature versions of themselves that have existed since the beginning of...

. He supported the doctrine of epigenesisEpigenesis (biology)In biology, epigenesis has at least two distinct meanings:* the unfolding development in an organism, and in particular the development of a plant or animal from an egg or spore through a sequence of steps in which cells differentiate and organs form;...

. A youthful follower of the German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm von LiebnitzGottfried LeibnizGottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was a German philosopher and mathematician. He wrote in different languages, primarily in Latin , French and German ....

(1646–1716), Wolff sought to resolve the problem of hybrids (mule, hinny, apemen) in his epigenesis, since these could not be well explained by performation.

- 1768. Sir Joseph BanksJoseph BanksSir Joseph Banks, 1st Baronet, GCB, PRS was an English naturalist, botanist and patron of the natural sciences. He took part in Captain James Cook's first great voyage . Banks is credited with the introduction to the Western world of eucalyptus, acacia, mimosa and the genus named after him,...

(1743–1820) and Daniel SolanderDaniel SolanderDaniel Carlsson Solander or Daniel Charles Solander was a Swedish naturalist and an apostle of Carl Linnaeus. Solander was the first university educated scientist to set foot on Australian soil.-Biography:...

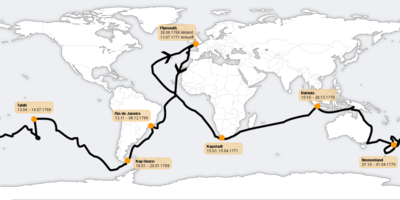

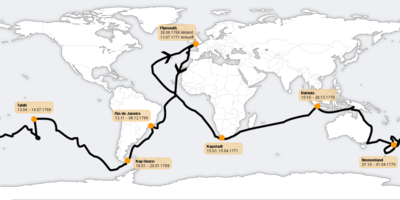

(1733–1782) sailed with Captain James Cook (English, 1728–1779) on the H.M.S. Endeavour for the South Seas (Tahiti), until 1771.

- 1769. Edward BancroftEdward BancroftEdward Bancroft was an American physician and double-agent spy during the American Revolution.He worked as a spy for Benjamin Franklin in Britain before the Revolution, and also while serving as secretary to the American Commission in Paris...

(English) wrote An Essay on the Natural History of Guyana in South America (1769) and advanced the theory that flies transmit disease.

- 1771. Johann Reinhold ForsterJohann Reinhold ForsterJohann Reinhold Forster was a German Lutheran pastor and naturalist of partial Scottish descent who made contributions to the early ornithology of Europe and North America...

(German, 1729–1798) was the naturalist on Cook's second voyage around the world (1772–1775). He published a Catalogue of the Animals of North America (1771) as an addendum to Kalm's Travels. He also studied the birds of Hudson Bay.

- 1774. Gilbert WhiteGilbert WhiteGilbert White FRS was a pioneering English naturalist and ornithologist.-Life:White was born in his grandfather's vicarage at Selborne in Hampshire. He was educated at the Holy Ghost School and by a private tutor in Basingstoke before going to Oriel College, Oxford...

(English) wrote The natural history and antiquities of Selborne, in the county of Southampton (1774) with fine ornithological observations on migration, territoriality and flocking.

- 1775. Johan Christian FabriciusJohan Christian FabriciusJohan Christian Fabricius was a Danish zoologist, specialising in "Insecta", which at that time included all arthropods: insects, arachnids, crustaceans and others...

(Danish, 1745–1808) wrote (1775), (1776), (1778), (1792–1794, in six vols.), and later publications (to 1805), to make Fabricius one of the world's greatest entomologists.

- 1776. René DutrochetHenri DutrochetRené Joachim Henri Dutrochet was a French physician, botanist and physiologist. He is best known for his investigation into osmosis.-Early Career:...

(French, 1776–1832) proposed an early version of the cell theory.

- 1780. Lazaro Spallanzani (Italian, 1729–1799) performed artificial fertilization in the frog, silkmoth and dog. He concluded from filtration experiments that spermatozoa were necessary for fertilization. In 1783 he showed that human digestion was a chemical process since gastric juices in and outside the body liquefied food (meat). He used himself as the experimental animal. His work to disprove spontaneous generation in microbes was resisted by John NeedhamJohn NeedhamJohn Turberville Needham FRS was an English biologist and Roman Catholic priest.He was first exposed to natural philosophy while in seminary school and later published a paper which, while the subject was mostly about geology, described the mechanics of pollen and won recognition in the botany...

(English priest, 1713–1781).

- 1780. Antoine LavoisierAntoine LavoisierAntoine-Laurent de Lavoisier , the "father of modern chemistry", was a French nobleman prominent in the histories of chemistry and biology...

(French, 1743–1794) and Pierre Laplace (French, 1749–1827) wrote Memoir on heat. Animal respiration was a form of combustion, a conclusion reached by this discoverer of Oxygen.

- 1783–1792. Alexandre Rodrigues FerreiraAlexandre Rodrigues FerreiraAlexandre Rodrigues Ferreira was a naturalist born in the Portuguese colony of Brazil. He undertook an extensive journey which crossed the interior of the Amazon Basin to Mato Grosso, between 1783 and 1792. During this journey, he described the agriculture, flora, fauna, and native inhabitants...

(Brazilian) undertook biological exploration. He wrote . His specimens were taken by Saint-HilaireÉtienne Geoffroy Saint-HilaireÉtienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire was a French naturalist who established the principle of "unity of composition". He was a colleague of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and expanded and defended Lamarck's evolutionary theories...

from LisbonLisbonLisbon is the capital city and largest city of Portugal with a population of 545,245 within its administrative limits on a land area of . The urban area of Lisbon extends beyond the administrative city limits with a population of 3 million on an area of , making it the 9th most populous urban...

to the Paris Museum during the Napoleonic invasion of Portugal. He is considered the "Brazilian Humboldt".

- 1784. Johann Wolfgang von GoetheJohann Wolfgang von GoetheJohann Wolfgang von Goethe was a German writer, pictorial artist, biologist, theoretical physicist, and polymath. He is considered the supreme genius of modern German literature. His works span the fields of poetry, drama, prose, philosophy, and science. His Faust has been called the greatest long...

(German) wrote (1795) that promoted the idea of archetypes to which animals should be compared. Vitalist and romantic, his zoology mostly follows Lorenz Oken.

- 1784. Thomas JeffersonThomas JeffersonThomas Jefferson was the principal author of the United States Declaration of Independence and the Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom , the third President of the United States and founder of the University of Virginia...

(American) wrote Notes on the State of Virginia (1784) that refuted some of Buffon's mistakes about the New World fauna. As U.S. President, he dispatched the Lewis and Clark expeditionLewis and Clark ExpeditionThe Lewis and Clark Expedition, or ″Corps of Discovery Expedition" was the first transcontinental expedition to the Pacific Coast by the United States. Commissioned by President Thomas Jefferson and led by two Virginia-born veterans of Indian wars in the Ohio Valley, Meriwether Lewis and William...

to the American West (1804).

- 1789? Guillaume Antoine Olivier (French, 1756–1814) wrote , or (1789).

- 1789. George ShawGeorge ShawGeorge Shaw was an English botanist and zoologist.Shaw was born at Bierton, Buckinghamshire and was educated at Magdalen Hall, Oxford, receiving his M.A. in 1772. He took up the profession of medical practitioner. In 1786 he became the assistant lecturer in botany at Oxford University...

& Frederick Polydore NodderFrederick Polydore NodderFrederick Polydore Nodder was an English flora and fauna illustrator.Nodder illustrated George Shaw's periodical The Naturalist's Miscellany. He also helped Joseph Banks prepare the Banks' Florilegium and converted most of Sydney Parkinson's Australian plant drawings into paintings and helped...

published The Naturalist's Miscellany: or coloured figures of natural objects drawn and described immediately from nature (1789–1813) in 24 volumes with hundreds of color plates.

- 1792. François HuberFrançois HuberFrançois Huber was a Swiss naturalist.He was born at Geneva, of a family which had already made its mark in the literary and scientific world: his great-aunt, Marie Huber, was known as a voluminous writer on religious and theological subjects, and as the translator and epitomizer of The Spectator...

made original observations on honeybees. In his (1792) he noted that the first eggs laid by queen bees develop into drones if her nuptial flight had been delayed and that her last eggs would also give rise to drones. He also noted that rare worker eggs develop into drones. This anticipated by over 50 years the discovery by Jan DzierżonJan DzierzonJohann Dzierzon, in Polish Jan Dzierżon or Dzierżoń , also John Dzierzon , was a pioneering apiarist who discovered the phenomenon of parthenogenesis in bees and designed the first successful movable-frame beehive.Dzierzon came from a Polish family in Silesia...

that drones come from unfertilized eggs and queen and worker bees come from fertilized eggs.

- 1793. Lazaro Spallanzani (Italian, 1729–1799) conducted experiments on the orientation of bats and owls in the dark.

- 1793. Christian Konrad SprengelChristian Konrad SprengelChristian Konrad Sprengel was a German theologist, teacher and, most importantly, a naturalist. He is most famously known for his research into plant sexuality....

(1750–1816) wrote (1793) that was a major work on insect pollination of flowers, previously discovered in 1721 by Philip MillerPhilip MillerPhilip Miller FRS was a Scottish botanist.Miller was chief gardener at the Chelsea Physic Garden from 1722 until he was pressured to retire shortly before his death...

(1694–1771), the head gardener at Chelsea and author of the famous Gardener's Dictionary (1731–1804).

- 1794. Erasmus DarwinErasmus DarwinErasmus Darwin was an English physician who turned down George III's invitation to be a physician to the King. One of the key thinkers of the Midlands Enlightenment, he was also a natural philosopher, physiologist, slave trade abolitionist,inventor and poet...

(English, grandfather of Charles DarwinCharles DarwinCharles Robert Darwin FRS was an English naturalist. He established that all species of life have descended over time from common ancestry, and proposed the scientific theory that this branching pattern of evolution resulted from a process that he called natural selection.He published his theory...

) wrote Zoönomia, or the Laws of Organic Life (1794) in which he advanced the idea that environmental influences could transform species.

- 1795. James HuttonJames HuttonJames Hutton was a Scottish physician, geologist, naturalist, chemical manufacturer and experimental agriculturalist. He is considered the father of modern geology...

(English) wrote Theory of the Earth (1795) in which he interpreted certain geological strata as former sea beds.

- 1796–1829. Pierre André LatreillePierre André LatreillePierre André Latreille was a French zoologist, specialising in arthropods. Having trained as a Roman Catholic priest before the French Revolution, Latreille was imprisoned, and only regained his freedom after recognising a rare species he found in the prison, Necrobia ruficollis...

(French, 1762–1833) sought to provide a "natural" system for the classification of animals, in his many monographs on invertebrates. (1811) was devoted to insects collected by Humboldt and BonplandAimé BonplandAimé Jacques Alexandre Bonpland was a French explorer and botanist.Bonpland's real name was Goujaud, and he was born in La Rochelle, a coastal city in France. After serving as a surgeon in the French army, and studying under J. N...

.

- 1798. Thomas Robert Malthus (English, 1766–1834) wrote Essay on the Principle of Population (1798), a book that was important to both Darwin and Wallace.

- 1799. George ShawGeorge ShawGeorge Shaw was an English botanist and zoologist.Shaw was born at Bierton, Buckinghamshire and was educated at Magdalen Hall, Oxford, receiving his M.A. in 1772. He took up the profession of medical practitioner. In 1786 he became the assistant lecturer in botany at Oxford University...

(English) provided the first description of the duck-billed platypus. Everard HomeEverard HomeSir Everard Home, 1st Baronet FRS was a British physician.Home was born in Kingston-upon-Hull and educated at Westminster School. He gained a schoalrship to Trinity College, Cambridge, but decided instead to become a pupil of his brother-in-law, John Hunter, at St. George's Hospital...

(1802) provided the first complete description.

- 1799–1803. Alexander von HumboldtAlexander von HumboldtFriedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander Freiherr von Humboldt was a German naturalist and explorer, and the younger brother of the Prussian minister, philosopher and linguist Wilhelm von Humboldt...

(German, 1769–1859) and Aimé Jacques Alexandre Goujaud BonplandAimé BonplandAimé Jacques Alexandre Bonpland was a French explorer and botanist.Bonpland's real name was Goujaud, and he was born in La Rochelle, a coastal city in France. After serving as a surgeon in the French army, and studying under J. N...

(French) arrived in Venezuela in 1799. Humboldt's Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America during the years 1799–1803 and Kosmos were very influential in his time and since.

- 1799. Georges CuvierGeorges CuvierGeorges Chrétien Léopold Dagobert Cuvier or Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier , known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist...

(French, 1769–1832) established comparative anatomy as a field of study. He also founded the science of paleontology. He wrote (1801–1805), (1816), (1812–1813). He believed in the fixity of species and the Biblical Flood. His early (1798) was influential, but it did not include Cuvier's major contributions to animal classification.

- 1799. American hunters killed the last bisonBisonMembers of the genus Bison are large, even-toed ungulates within the subfamily Bovinae. Two extant and four extinct species are recognized...

in the American East, in Pennsylvania.

Nineteenth century

- 1802. Jean-Baptiste de Lamarck (French, 1744–1829) wrote and (1809). He was an early evolutionist and organized invertebrate paleontology. While Lamarck's contributions to science include work in meteorology, botany, chemistry, geology, and paleontology, he is best known for his work in invertebrate zoology and his theoretical work on evolution. He published an impressive seven-volume work, ("Natural history of animals without backbones"; 1815–1822).

- 1813–1818. William Charles WellsWilliam Charles WellsWilliam Charles Wells MD FRS FRSEd , was a Scottish-American physician and printer. He lived a life of extraordinary variety, did some notable medical research, and made the first clear statement about natural selection. He applied the idea to the origin of different skin colours in human races,...

(Scottish-American, 1757–1817) was the first to recognise the principle of natural selectionNatural selectionNatural selection is the nonrandom process by which biologic traits become either more or less common in a population as a function of differential reproduction of their bearers. It is a key mechanism of evolution....

. He read a paper to the Royal SocietyRoyal SocietyThe Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

in 1813 (but not published until 1818) which used the idea to explain differences between human races. The application was limited to the question of how different skin colours arose.

- 1815. William Kirby and William SpenceWilliam SpenceWilliam Guthrie Spence , Australian trade union leader and politician, played a leading role in the formation of both Australia's largest union, the Australian Workers Union, and the Australian Labor Party.-Early life:...

(English) wrote An Introduction to Entomology (first edition in 1815). This was the first modern entomology text.

- 1817. Georges CuvierGeorges CuvierGeorges Chrétien Léopold Dagobert Cuvier or Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric Cuvier , known as Georges Cuvier, was a French naturalist and zoologist...

wrote Le Règne Animal (Paris).

- 1817–1820. Johann Baptist von SpixJohann Baptist von SpixDr. Johann Baptist Ritter von Spix was a German naturalist.Spix was born in Höchstadt, Middle Franconia, as the seventh of eleven children. His boyhood home is the site of the Spix Museum , opened to the public in 2004...

(German, 1781–1826) and Carl Friedrich Philipp von MartiusCarl Friedrich Philipp von MartiusCarl Friedrich Philipp von Martius was a German botanist and explorer.Martius was born at Erlangen, where he graduated M.D. in 1814, publishing as his thesis a critical catalogue of plants in the botanic garden of the university...

(German) conducted Brazilian zoological and botanical explorations (1817–1820). See their (3 vols., 1823–1831).

- 1817. William SmithWilliam Smith (geologist)William 'Strata' Smith was an English geologist, credited with creating the first nationwide geological map. He is known as the "Father of English Geology" for collating the geological history of England and Wales into a single record, although recognition was very slow in coming...

, in his Strategraphical System of Organized Fossils (1817) showed that certain strata have characteristic series of fossils.

- 1817. Thomas SayThomas SayThomas Say was an American naturalist, entomologist, malacologist, herpetologist and carcinologist. A taxonomist, he is often considered to be the father of descriptive entomology in the United States. He described more than 1,000 new species of beetles and over 400 species of insects of other...

(American, 1787–1834) was a brilliant young systematic zoologist until he moved to the utopian community at New Harmony, Indiana, in 1825. Luckily, most of his insect collections have been recovered.

- William Lawrence (English, 1783–1867) published a book of his lectures to the Royal College of Surgeons in 1819. The book contains a remarkably clear rejection of LamarckismLamarckismLamarckism is the idea that an organism can pass on characteristics that it acquired during its lifetime to its offspring . It is named after the French biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck , who incorporated the action of soft inheritance into his evolutionary theories...

(soft inheritanceSoft inheritanceSoft inheritance is the term coined by Ernst Mayr to include such ideas as Lamarckism, that an organism can pass on characteristics that it acquired during its lifetime to its offspring. It contrasts with modern ideas of inheritance, which Mayr called hard inheritance...

), proto-evolutionary ideas about the origin of mankind, and a forthright denial of the 'Jewish scriptures' (= Old TestamentOld TestamentThe Old Testament, of which Christians hold different views, is a Christian term for the religious writings of ancient Israel held sacred and inspired by Christians which overlaps with the 24-book canon of the Masoretic Text of Judaism...

). He was forced to suppress the book after the Lord Chancellor refused copyright and other powerful men made threatening remarks. His subsequent life was highly successful.

- 1824. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) is founded at London.

- 1825. Gideon MantellGideon MantellGideon Algernon Mantell MRCS FRS was an English obstetrician, geologist and palaeontologist...

(English) wrote "Notice on the Iguanodon, a newly discovered fossil reptile, from the sandstone of Tilgate Forest, in Sussex" (Phil. Trans. Roy, Soc. Lond., 115: 179–186) is the first paper on dinosaurs. The name dinosaur was coined by anatomist Richard OwenRichard OwenSir Richard Owen, FRS KCB was an English biologist, comparative anatomist and palaeontologist.Owen is probably best remembered today for coining the word Dinosauria and for his outspoken opposition to Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection...

.

- 1826. The Zoological Gardens in Regent's Park is founded by the Zoological Society of LondonZoological Society of LondonThe Zoological Society of London is a charity devoted to the worldwide conservation of animals and their habitats...

with help from Sir Thomas Raffles. It opened its "zoo" to the public for two days a week beginning April 27, 1828, with the first hippopotamus to be seen in Europe since the ancient Romans showed one at the Coliseum. The Society will help save bird and animal species from extinction.

- 1826–1839. John James AudubonJohn James AudubonJohn James Audubon was a French-American ornithologist, naturalist, and painter. He was notable for his expansive studies to document all types of American birds and for his detailed illustrations that depicted the birds in their natural habitats...

(Haitian-born American, 1785–1851) wrote Birds of America (1826–1839), with North American bird portraits and studies. See also his posthumously published volume on North American. Quadrupeds, written with his sons and the naturalist John Bachman, The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America (1845–1854) with 150 folio plates.

- 1827. Karl Ernst von BaerKarl Ernst von BaerKarl Ernst Ritter von Baer, Edler von Huthorn also known in Russia as Karl Maksimovich Baer was an Estonian naturalist, biologist, geologist, meteorologist, geographer, a founding father of embryology, explorer of European Russia and Scandinavia, a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, a...

(Russian embryologist, 1792–1876) was the founder of comparative embryology. He demonstrated the existence of the mammalian ovum, and he proposed the germ-layer theory. His major works include (1827) and (1828; 1837).

- 1829. James Smithson (English, 1765–1829) donated seed money in his will for the founding of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington.