Foreign relations of Libya

Encyclopedia

The foreign relations of Libya under Gaddafi (1969–2011) underwent much fluctuation and change. They were marked by severe tension with the West

(especially the United States

, although relations were normalized in the early 21st century prior to the 2011 Libyan civil war

) and by Gaddafi's activist policies in the Middle East

and Africa

, including his financial and military support for numerous paramilitary and rebel groups.

Muammar Gaddafi

has determined Libya

's foreign policy. His principal foreign policy goals have been Arab unity, elimination of Israel

, advancement of Islam

, support for Palestinians

, elimination of outside—particularly Western—influence in the Middle East

and Africa

, and support for a range of "revolutionary" causes.

After the 1969 coup

, U.S.-Libyan relations became increasingly strained because of Libya's foreign policies supporting international terrorism

and subversion against moderate Arab and African governments. Gaddafi closed American

and British

bases on Libyan territory and partially nationalized

all foreign oil and commercial interests in Libya.

controls on military

equipment and civil aircraft

were imposed during the 1970s.

On 11 June 1972, Gaddafi announced that any Arab wishing to volunteer for Palestinian armed groups "can register his name at any Libyan embassy will be given adequate training for combat". He also promised financial support for attacks. In response, the United States withdrew its ambassador

. On 7 October 1972, Gaddafi praised the Lod Airport massacre

, carried out by the Japanese Red Army

, and demanded Palestinian terrorist groups to carry out similar attacks.

Gaddafi played a key role in promoting the use of oil embargo

es as a political weapon for challenging the West, hoping that an oil price rise and embargo in 1973 would persuade the West—especially the United States—to end support for Israel. Gaddafi rejected both Soviet communism

and Western capitalism

and claimed he was charting a middle course for his government.

In 1973 the Irish Naval Service intercepted the vessel Claudia in Irish territorial waters, which carried Soviet arms from Libya to the Provisional IRA.

In 1976 after a series of terror attacks by the Provisional IRA, Gaddafi announced that "the bombs which are convulsing Britain and breaking its spirit are the bombs of Libyan people. We have sent them to the Irish revolutionaries so that the British will pay the price for their past deeds".

Together with Fidel Castro

and other Communist leaders, Gaddafi supported Soviet

protege Haile Mariam Mengistu, the military ruler of Ethiopia

, who was later convicted for a genocide

that killed thousands.

In October 1978, Gaddafi sent Libyan troops to aid Idi Amin

in the Uganda-Tanzania War

when Amin tried to annex the northern Tanzania

n province of Kagera

, and Tanzania counterattacked. Amin lost the battle and later fled to exile in Libya, where he remained for almost a year.

Libya also was one of the main supporters of the Polisario Front

in the former Spanish Sahara

– a nationalist

group dedicated to ending Spanish colonialism

in the region. The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic

(SADR) was proclaimed by Polisario on 28 February 1976, and Libya began to recognize the SADR

as the legitimate government of Western Sahara

starting 15 April 1980. It is still common for Sahrawi students to attend their schooling in Libya.

Gaddafi also aided Jean-Bedel Bokassa

, the self-proclaimed emperor of the short-lived Central African Empire

.

U.S. embassy

staff members were withdrawn from Tripoli after a mob attacked and set fire to the embassy in December 1979. The U.S. government

declared Libya a "state sponsor of terrorism

" on 29 December 1979.

In August 1981, in the first incident

of the Gulf of Sidra

, two Libyan jets fired on U.S. aircraft participating in a routine naval exercise over international waters

of the Mediterranean Sea

claimed by Libya. The U.S. planes returned fire and shot down the attacking Libyan aircraft. 11 On December 1981, the State Department

invalidated U.S. passport

s for travel to Libya (a de facto

travel ban) and, for purposes of safety, advised all U.S. citizens in Libya to leave. In March 1982, the U.S. government prohibited imports of Libyan crude oil into the United States

and expanded the controls on U.S.-origin goods intended for export to Libya. Licenses were required for all transactions, except food and medicine. In March 1984, U.S. export controls were expanded to prohibit future exports to the Ra's Lanuf petrochemical complex. In April 1985, all Export-Import Bank

financing was prohibited.

In October 1981, Egypt

ian President Anwar Sadat

was assassinated. Gaddafi applauded the murder and remarked that it was a "punishment" for Sadat's signing of the Camp David Accords

with the United States and Israel

.

In April 1984, Libyan refugees in London protested against execution of two dissidents. Libyan diplomats shot at 11 people and killed Yvonne Fletcher

In April 1984, Libyan refugees in London protested against execution of two dissidents. Libyan diplomats shot at 11 people and killed Yvonne Fletcher

, a British policewoman. The incident led to the breaking off of diplomatic relations

between the United Kingdom and Libya for over a decade. Two months later, Gaddafi asserted that he wanted his agents to assassinate dissident refugees, even if they were just on pilgrimage in the holy city of Mecca

—in August 1984, a Libyan plot in Mecca was thwarted by Saudi Arabian police.

After the December 1985 Rome and Vienna airport attacks

, which killed 19 and wounded around 140, Gaddafi indicated that he would continue to support the Red Army Faction, the Red Brigades, and the Irish Republican Army as long as European countries support anti-Gaddafi Libyans.

The Foreign Minister of Libya also called the massacres "heroic acts".

In 1986 Libyan state television announced that Libya was training suicide squads to attack American and European interests.

Gaddafi claimed the Gulf of Sidra

as his territorial water and his navy was involved in a conflict from January to March 1986.

On 5 April 1986, Libyan agents bombed "La Belle" nightclub in West Berlin

, killing three people and injuring 229 people who were spending the evening there. Gaddafi's plan was intercepted by Western intelligence. More detailed information was retrieved years later when Stasi

archives were investigated by the reunited Germany. Libyan agents who had carried out the operation from the Libyan embassy in East Germany were prosecuted by reunited Germany in the 1990s.

Germany and the United States learned that the bombing in West Berlin had been ordered from Tripoli. On 14 April 1986, the United States carried out Operation El Dorado Canyon

against Gaddafi and members of his regime. Air defenses, three army bases, and two airfields in Tripoli

and Benghazi

were bombed. The surgical strikes failed to kill Gaddafi but he lost a few dozen military officers.

Gaddafi announced that he had won a spectacular military victory over the United States

and the country was officially renamed the "Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriyah". However, his speech appeared devoid passion and even the "victory" celebrations appeared unusual. Criticism of Gaddafi by ordinary Libyan citizens became more bold, such as defacing of Gaddafi posters. The raids against Gaddafi had brought the regime to its the weakest point in 17 years.

The Chadian–Libyan conflict (1978–1987) ended in disaster for Libya in 1987 with the Toyota War

. France supported Chad in this conflict and two years later on 19 September 1989, a French airliner, UTA Flight 772

, was destroyed by an in-flight explosion for which Libyan agents were convicted in absentia. The incident bore close similarities to the destruction of Pan Am Flight 103

(the Lockerbie Bombing) a year earlier. The downing of these two airliners along with the 1986 Berlin discotheque bombing

seemed to establish a pattern of reprisal

attacks—in the form of terrorist bombings—by Libya or at least Libyan agents. The United Nations imposed sanctions on Libya for these two acts (with UN Security Council Resolutions 731

, 748

and 883

). The UN eventually lifted these sanctions (with Resolution 1506

) in 2003 when Libya "accepted responsibility for the actions of its officials, renounced terrorism and arranged for payment of appropriate compensation for the families of the victims." In 2008 Libya established a fund to compensate victims of these three terrorist acts (and the 1986 US bombing of Tripoli and Benghazi).

Gaddafi fueled a number of Islamist and communist terrorist groups in the Philippines

, as well as paramilitaries in Oceania

. He attempted to radicalize New Zealand

's Maori people in a failed effort to destabilise the U.S. ally. In Australia

, he financed trade unions and some politicians who opposed the ANZUS

alliance with the United States. In May 1987, Australia deported diplomats and broke off relations with Libya because of its activities in Oceania.

In late 1987 French authorities stopped a merchant vessel, the MV Eksund, which was delivering a 150 ton Libyan arms shipment to European terrorist groups.

In 1988, Libya was found to be in the process of constructing a chemical weapons plant at Rabta, a plant which became the largest such facility in the Third World

.

Libya's relationship with the former Soviet Union

involved massive Libyan arms purchases from the Soviet bloc

and the presence of thousands of east bloc advisers. Libya's use—and heavy loss—of Soviet-supplied weaponry in its war with Chad

was a notable breach of an apparent Soviet-Libyan understanding not to use the weapons for activities inconsistent with Soviet objectives. As a result, Soviet-Libyan relations reached a nadir in mid-1987.

In January 1989, there was another encounter

over the Gulf of Sidra between U.S. and Libyan aircraft which resulted in the downing of two Libyan jets.

. Six other Libyans were put on trial in absentia for the 1989 bombing of UTA Flight 772

over Chad

and Niger

. The UN Security Council demanded that Libya surrender the suspects, cooperate with the Pan Am 103 and UTA 772 investigations, pay compensation to the victims' families, and cease all support for terrorism. Libya's refusal to comply led to the approval of Security Council Resolution 748

on 31 March 1992, imposing international sanctions

on the state designed to bring about Libyan compliance. Continued Libyan defiance led to further sanctions by the UN against Libya in November 1993.

After the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact

and the Soviet Union, Libya concentrated on expanding diplomatic ties with Third World

countries and increasing its commercial links with Europe

and East Asia

. Following the imposition of U.N. sanctions in 1992, these ties significantly diminished. Following a 1998 Arab League meeting in which fellow Arab states decided not to challenge U.N. sanctions, Gaddafi announced that he was turning his back on pan-Arab ideas, one of the fundamental tenets of his philosophy.

Instead, Libya pursued closer bilateral ties, particularly with Egypt

and Northwest African nations Tunisia

and Morocco

. It also has sought to develop its relations with Sub-Saharan Africa

, leading to Libyan involvement in several internal African disputes in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan

, Somalia

, Central African Republic

, Eritrea

, and Ethiopia

. Libya also has sought to expand its influence in Africa through financial assistance, ranging from aid donations to impoverished neighbors such as Niger

to oil subsidies to Zimbabwe

. Gaddafi has proposed a borderless "United States of Africa

" to transform the continent into a single nation-state ruled by a single government. This plan has been moderately well received, although more powerful would-be participants such as Nigeria

and South Africa

are skeptical.

Gaddafi also trained and supported Charles Taylor, who was indicted by the Special Court for Sierra Leone

for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed during the conflict in Sierra Leone.

Libya had close ties with Slobodan Milošević

's regime in Yugoslavia

. Gaddafi aligned himself with the Orthodox Serbs against Bosnia and Herzegovina

's Muslims

and Kosovo

's Albanians. Gaddafi supported Milošević even when Milošević was charged with large-scale ethnic cleansing against Albanians in Kosovo

.

In 1996, the Iran and Libya Sanctions Act

(ILSA) was enacted, seeking to penalize non-U.S. companies which invest more than $40 million in Libya's oil and gasoline sector in any one year. ILSA was renewed in 2001, and the investment cap lowered to $20 million.

In 1999, less than a decade after the UN sanctions were put in place, Libya began to make dramatic policy changes in regard to the Western world, including turning over the Lockerbie suspects for trial. This diplomatic breakthrough followed years of negotiation, including a visit by UN Secretary General Kofi Annan to Libya in December 1998, and personal appeals by Nelson Mandela. Eventually UK Foreign Secretary Robin Cook persuaded the Americans to accept a trial of the suspects in the Netherlands under Scottish law, with the UN Security Council agreeing to suspend sanctions as soon as the suspects arrived in the Netherlands for trial. Libya also paid compensation in 1999 for the death of British policewoman Yvonne Fletcher

, a move that preceded the reopening of the British embassy in Tripoli and the appointment of ambassador Sir Richard Dalton, after a 17-year break in diplomatic relations.

As of January 2002, Libya was constructing another chemical weapons production facility at Tarhuna. Citing Libya's support for terrorism and its past regional aggressions the United States voiced concern over this development. In cooperation with like-minded countries, the United States has since sought to bring a halt to the foreign technical assistance deemed essential to the completion of this facility. See Chemical weapon proliferation#Libya.

As of January 2002, Libya was constructing another chemical weapons production facility at Tarhuna. Citing Libya's support for terrorism and its past regional aggressions the United States voiced concern over this development. In cooperation with like-minded countries, the United States has since sought to bring a halt to the foreign technical assistance deemed essential to the completion of this facility. See Chemical weapon proliferation#Libya.

Following the fall of Saddam Hussein

's regime in 2003, Gaddafi decided to abandon his weapons of mass destruction

programs and pay almost 3 billion euros in compensation to the families of Pan Am Flight 103 and UTA Flight 772. The decision was welcomed by many western nations and was seen as an important step toward Libya rejoining the international community. Since 2003 the country has made efforts to normalize its ties with the European Union

and the United States and has even coined the catchphrase, 'The Libya Model', an example intended to show the world what can be achieved through negotiation, rather than force, when there is goodwill on both sides. By 2004 George W. Bush

had lifted the economic sanctions and official relations resumed with the United States. Libya opened a liaison office in Washington

, and the United States opened an office in Tripoli

. In January 2004, Congressman Tom Lantos

led the first official Congressional delegation visit to Libya.

Libya has supported Sudan's President Omar al-Bashir

despite charges of a genocide in Darfur

.

The release, in 2007, of five Bulgarian nurses and a Palestinian doctor

, who had been held since 1999, charged with conspiring to deliberately infect over 400 children with HIV, was seen as marking a new stage in Libyan-Western relations.

The United States removed Gaddafi's regime, after 27 years, from its list of states sponsoring terrorism.

On 16 October 2007, Libya was elected to serve on the United Nations Security Council

for two years starting in January 2008.

In August 2008 Italian Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi

signed an agreement to pay Libya $5 billion over 25 years – this was a "complete and moral acknowledgement of the damage inflicted on Libya by Italy during the colonial era", the Italian prime minister said. In September 2008, US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice

met with Gaddafi and announced that US-Libya relations have entered a 'new phase'.

Libyan-Swiss relations strongly suffered after the arrest of Hannibal Gaddafi

for beating up his domestic servants in Geneva

in 2008. In response, Gaddafi removed all his money held in Swiss banks and asked the United Nations to vote to abolish Switzerland

as a sovereign nation.

In February 2009, Gaddafi was selected to be chairman of the African Union

for one year. The same year, the United Kingdom and Libya signed a prisoner-exchange agreement and then Libya requested the transfer of the convicted Lockerbie bomber, who finally returned home in August 2009.

On 23 September 2009, Colonel Gaddafi addressed the 64th session of the UN General Assembly in New York, his first visit to the United States

On 23 September 2009, Colonel Gaddafi addressed the 64th session of the UN General Assembly in New York, his first visit to the United States

.

As of 25 October 2009, Canadian

visa requests were being denied and Canadian travelers were told they were not welcome in Libya. Specifically, Harper's government was planning to publicly criticize Gaddafi for praising the convicted Lockerbie bomber.

The sincerity of the good faith efforts of the Libyan government may be questionable since Moroccan Foreign Minister Taieb Fassi Fihri, told a U.S. diplomat in 2009 that the Libyans were willing to host wounded Guinean junta leader Captain Moussa Dadis Camara

after a failed assassination attempt in 2009. Libya also still provided bounties for heads of refugees who criticized Gaddafi, including 1 million dollars for Ashur Shamis, a Libyan-British journalist.

, Gaddafi condemned the Tunisian revolution

in January 2011, saying protesters were misled by WikiLeaks

and voicing solidarity with ousted President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali

.

The progress made by Gaddafi's government in improving relations with the Western world

was swiftly set back by the regime's authoritarian crackdown on protests

that began the following month. Many Western countries, including the United Kingdom

, the United States

, and eventually Italy

condemned Libya for the brutal crackdown on the disidents. Peru

became the first of several countries to sever diplomatic relations with Tripoli

on 22 February 2011, followed closely by African Union

member state Botswana

the following day.

Libya was suspended from Arab League

proceedings on 22 February 2011, the same day Peru terminated bilateral relations. In response, Gaddafi declared that in the view of his government, "The Arab League is finished. There is no such thing as the Arab League."

On 10 March 2011, France

became the first country to not just break off relations with the jamahiriya

, but transfer diplomatic recognition to the rebel National Transitional Council

established in Benghazi

, declaring it to be "the sole legitimate representative of the Libyan people". As of 20th September 2011, a total of 98 countries have taken this step.

On 19 March 2011, a coalition of United Nations

member states led by France, the United Kingdom, and the United States began military operations

in Libyan airspace and territorial waters after the United Nations Security Council

approved UNSCR 1973

, ostensibly to prevent further attacks on civilians as loyalist forces closed in on Benghazi, the rebel headquarters. In response, Gaddafi declared that a state of "war with no limits" existed between Libya and the members of the coalition. Despite this, he sent a three-page letter to US President Barack Obama

imploring him to "annul a wrong and mistaken action" and stop striking Libyan targets, repeatedly referring to him as "our son" and blaming the uprising on the terrorist

group al Qaeda.

In 2003 Libya began to make policy changes with the open intention of pursuing a Western-Libyan détente

In 2003 Libya began to make policy changes with the open intention of pursuing a Western-Libyan détente

. The Libyan government announced its decision to abandon its weapons of mass destruction

programs and pay almost $3 billion dollars in compensation to the families of Pan Am Flight 103 and UTA Flight 772.

Starting in 2003, the Libyan government restored normal diplomatic ties with the European Union

and the United States and has even coined the catchphrase, "The Libya Model", an example intended to show the world what can be achieved through negotiation rather than force when there is goodwill on both sides.

On 31 October 2008, Libya paid $1.5 billion, sought through donations from private businesses, to a fund that would be used to compensate both US victims of the 1988 bombing of Pan Am flight 103 and the 1986 bombing of the La Belle disco in Germany. In addition, Libyan victims of US airstrikes that followed the Berlin attack will also be compensated with $300 million from the fund. US state department spokesman, Sean McCormack

called the move a "laudable milestone ... clearing the way for continued and expanding US-Libyan partnership." This final payment under the US-Libya Claims Settlement Agreement was seen as a major step towards improving ties between the two, which had begun easing after Tripoli halted its arms programmes. George Bush

also signed an executive order restoring Libya's immunity from terror-related lawsuits and dismissing pending compensation cases.

On 17 November, 2008, FCO

minister Bill Rammell

signed five agreements with Libya. Rammell said: "I will today sign four bilateral agreements with my Libyan counterpart, Abdulatti al-Obidi

, which will strengthen our judicial ties, as agreed during Tony Blair

's visit to Libya in May last year. In addition, we are signing today a Double Taxation Convention which will bring benefits to British business in Libya and Libyan investors in the UK – benefits in terms of certainty, clarity and transparency and reducing tax compliance burdens. We are also in the final stages of negotiating an agreement to protect and promote investment."

"UK/Libya relations have significantly improved in recent years, following Libya's voluntary renunciation of WMD. Today we are partners in the UN Security Council. We also wish to assist Libya to establish closer relations with the European Union

to continue and strengthen the reintegration of Libya within the international community. We therefore support the commencement of negotiations between Libya and the EU on a framework agreement which should cover a range of issues including political, social, economic, commercial and cultural relations between the EU and Libya."

On 21 November 2008, the US Senate confirmed the appointment of Gene Cretz

to be the first US ambassador to Libya since 1972.

During the 2011 Libyan civil war

, all European Union

and NATO member states withdrew diplomatic staff from Tripoli

and shut their embassies in the Libyan capital. Several foreign embassies and UN offices were badly damaged by vandals on 1 May 2011, drawing condemnation from the United Kingdom

and Italy

. The UK also expelled the Libyan ambassador in London

from the country.

On 1 July 2011, Gaddafi threatened to sponsor attacks against civilians and businesses in Europe

in what would be a resumption of his policies of the 1970s and 1980s.

On 30 August 2008, Gaddafi and Italian

Prime Minister

Silvio Berlusconi

signed a historic cooperation

treaty

in Benghazi

. Under its terms, Italy will pay $5 billion to Libya as compensation for its former military occupation

. In exchange, Libya will take measures to combat illegal immigration

coming from its shores and boost investment

s in Italian companies. The treaty was ratified by Italy in 6 February 2009, and by Libya on 2 March, during a visit to Tripoli

by Berlusconi. In June, Gaddafi made his first visit to Rome

, where he met Prime Minister Berlusconi, President

Giorgio Napolitano

, Senate President

Renato Schifani

, and Chamber President

Gianfranco Fini

, among others. The Democratic Party

and Italy of Values

opposed the visit, and many protests were staged throughout Italy by human rights

organizations

and the Radical Party

. Gaddafi also took part in the G8

summit

in L'Aquila

in July as Chairman of the African Union

.

In the 2005-2009 period, Italy has been the first EU arms exporter towards Libya, with a total value of €276.7m, of which one third only in the last 2008-2009 years. Italian exports cover one third of total EU arms exports towards Libya, and include mainly military aircraft

but also missiles and electronic equipments.

During the 2011 Libyan civil war

, Italy terminated relations with Tripoli

and recognized the rebel authority

in Benghazi

as Libya's legitimate representative, effectively starting relations with the Libyan Republic. The Italian government has urged the international community to follow suit.

court found four persons, including a former employee of the Libyan embassy in East Berlin

, guilty in connection with the 1986 Berlin discotheque bombing

, in which 229 people were injured and two U.S. servicemen were killed. The court also established a connection to the Libyan government. The German government

has demanded that Libya accept responsibility for the La Belle bombing and pay appropriate compensation.

, Abdelbaset al-Megrahi and Lamin Khalifah Fhimah

, were charged with the December 1988 Lockerbie bombing. Libya refused to extradite the two accused to the U.S. or to Scotland

. As a result, United Nations Security Council Resolution 748

was approved on 31 March 1992, requiring Libya to surrender the suspects, cooperate with the Pan Am Flight 103

and UTA Flight 772

investigations, pay compensation to the victims' families, and cease all support for terrorism. The UN imposed further sanctions with Resolution 883, a limited assets freeze and an embargo on selected oil equipment, in November 1993. In 1999, six other Libyans who had been accused of the September 1989 bombing of Union Air Transport Flight 772

were put on trial in their absence by a Paris

court. They were found guilty and sentenced to life imprisonment

.

The Libyan government eventually surrendered the two Lockerbie bombing suspects in 1999 for trial at the Scottish Court in the Netherlands

and UN sanctions were suspended. On 31 January 2001, at the end of the Pan Am Flight 103 bombing trial

, Megrahi was convicted of murder and sentenced to 27 years in prison. Fhimah was found not guilty and was freed to return to Libya. Megrahi appealed against his conviction but this was rejected in February 2002. In 2003, Libya wrote to the UN Security Council admitting "responsibility for the actions of its officials" in relation to the Lockerbie bombing, renouncing terrorism and agreeing to pay compensation to the relatives of the 270 victims. The previously suspended UN sanctions were then cancelled.

In June 2007, the Scottish Criminal Cases Review Commission

decided that there may have been a miscarriage of justice

and referred Megrahi's case back to Court of Criminal Appeal

in Edinburgh

for a second appeal. Expected to last for a year, the appeal began in April 2009 and was adjourned in May 2009. Having been diagnosed with terminal cancer, Megrahi dropped the appeal and on 20 August 2009, was granted compassionate release from jail and repatriated to Libya. In an interview with the Wall Street Journal on 24 September 2009, the day after his address to the UN General Assembly in New York, Colonel Gaddafi said: "As a case, the Lockerbie question: I would say it's come to an end, legally, politically, financially, it is all over."

children's hospital

was the site of an outbreak

of HIV

infection that spread to over 400 patients. Libya blamed the outbreak on five Bulgarian nurses and a Palestinian doctor, who were arrested and eventually sentenced to death (eventually overturned and a new trial ordered). The international view is that Libya has used the medics as scapegoat

s for poor hygiene conditions, and Bulgaria

and other countries including the European Union

and the United States

repeatedly called on Tripoli to release them. A new trial began 11 May 2006, in Tripoli. On 6 December a study was released showing that some children had been infected before the six arrived in Libya, but it was too late for inclusion as evidence. On 19 December 2006, the six were again convicted and sentenced to death. They were finally released in June 2007, after mediation of French president Nicolas Sarkozy

, in exchange for a variety of agreements with the EU, and they were returned to Bulgaria safely.

, Switzerland

and then released on bail on 17 July. Hannibal Gaddafi has a history of violent and aggressive behaviour having been charged with battery by his later wife and having attacked Italian police officers.

The government of Libya subsequently put a boycott on Swiss imports, reduced flights between Libya and Switzerland, stopped issuing visas to Swiss citizens, recalled diplomats from Bern, and forced all Swiss companies such as ABB and Nestlé

to close offices. General National Maritime Transport Company, which owns a large refinery in Switzerland, also halted oil shipments to Switzerland.

Two Swiss businessmen, Rachid Hamdani and Max Göldi, Libya head of ABB, who were in Libya at the time were denied permission to leave the country and were forced to take shelter at the Swiss embassy in Tripoli. Both were initially sentenced to 6 months in prison for immigration offenses, but Hamdani was cleared on appeal and Göldi's sentence was reduced to four months. Göldi surrendered to Libyan authorities on 22 February 2010, while Hamdani returned to Switzerland on 24 February.

At the 35th G8 summit

in July 2009, Muammar Gaddafi called Switzerland a "world mafia" and called for the country to be split between France, Germany and Italy.

In August 2009 Swiss President Hans-Rudolf Merz

visited Tripoli

and issued a public apology to Libya for the arrest of Hannibal Gaddafi and his wife. Geneva's prosecutor dropped the case against the Gaddafis when the employees withdrew their formal complaint after reaching an undisclosed settlement.

to nationals of any of the countries within the Schengen Area

, of which Switzerland is a part. This action was apparently taken in retaliation for Switzerland blacklisting 188 high-ranking officials from Libya, although there has been no official confirmation from Libya itself about why they have taken this action.

As a result of the ban, foreign nationals from certain countries were not permitted entry into Libya at Tripoli airport

, including 22 Italians

and eight Maltese

citizens, one of whom was forced to wait for 20 hours before he was able to return home. Three Italians, nine Portuguese nationals, a Frenchman and a European citizen who arrived from Cairo

were repatriated. In addition to citizens of Schengen Area countries being refused entry, it has been reported that several Irish citizens have been turned away, despite Ireland

not being a member of the Schengen agreement

. An unnamed Libyan official at the airport asked to confirm the ban told Reuters: "This is right. This decision has been taken. No visas for Europeans, except Britain."

In response, the European Commission

criticised the actions, describing them as "unilateral and disproportionate", although no immediate 'tit-for-tat

' response was announced.

, with some having a socialist

ideology; while others hold a more conservative

and Islam

ic fundamentalist

ideology.

Paramilitaries supported by Libya past and present include:

and part of southeastern Algeria

. In addition, it is involved in a maritime boundary

dispute with Tunisia

.

As with all other African countries, Libya is a member of the Non-Aligned Movement

. As with most international organizations to which Tripoli

is a party, NAM recognizes it under the name Libyan Arab Jamahiriya.

in the Western Sahara

facilitated early post independence Algerian relations with Libya. Libyan inclinations for full-scale political union, however, have obstructed formal political collaboration because Algeria

has consistently backed away from such cooperation with its unpredictable neighbour.

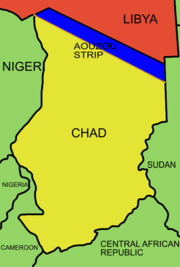

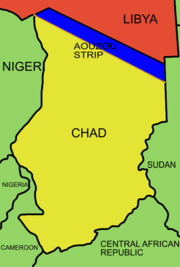

Libya long claimed the Aouzou Strip, a strip of land in northern Chad

Libya long claimed the Aouzou Strip, a strip of land in northern Chad

rich with uranium

deposits that was intensely involved in Chad's civil war in the 1970s and 1980s.

In 1973, Libya engaged in military operations in the Aouzou Strip to gain access to minerals and to use it as a base of influence in Chadian politics. Libya argued that the territory was inhabited by indigenous people who owed allegiance to the Senussi Order and subsequently to the Ottoman Empire

, and that this title had been inherited by Libya. It also supported its claim with an unratified 1935 treaty between France

and Italy

, the colonial powers

of Chad and Libya, respectively. After consolidating its hold on the strip, Libya annexed

it in 1976. Chadian forces were able to force the Libyans

to retreat from the Aouzou Strip in 1987.

A cease-fire between Chad and Libya held from 1987 to 1988, followed by unsuccessful negotiations over the next several years, leading finally to the 1994 International Court of Justice

decision granting Chad sovereignty over the Aouzou Strip, which ended Libyan occupation

.

Chadian-Libyan relations were ameliorated when Libyan-supported Idriss Déby

unseated Habré on 2 December. Gaddafi was the first head of state to recognize the new regime, and he also signed treaties of friendship and cooperation on various levels; but regarding the Aouzou Strip Déby followed his predecessor, declaring that if necessary he would fight to keep the strip out of Libya's hands.

The Aouzou dispute was concluded for good on 3 February 1994, when the judges of the ICJ by a majority of 16 to 1 decided that the Aouzou Strip belonged to Chad. The court's judgement was implemented without delay, the two parties signing as early as 4 April an agreement concerning the practical modalities for the implementation of the judgement. Monitored by international observers, the withdrawal of Libyan troops from the Strip began on 15 April and was completed by 10 May. The formal and final transfer of the Strip from Libya to Chad took place on 30 May, when the sides signed a joint declaration stating that the Libyan withdrawal had been effected.

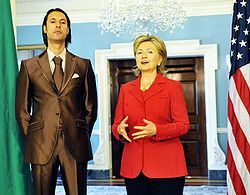

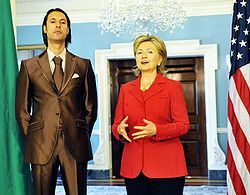

During the 2011 Libyan civil war

, after meeting with high-level representatives of the Chadian government, United States

Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton

announced that N'Djamena

opposes Gaddafi and has reached out to the rival National Transitional Council

in rebel-held Benghazi

. This claim was disputed by at least one foreign policy

analyst, who brought up previous remarks made by Ambassador Daoussa Déby, the Chadian president's half-brother, and said, "Déby's words seem to echo Gaddafi's claims that the terrorist group al-Qaeda

masterminded the national uprising in Libya."

and Libya both gained independence in the early 1950s, relations were initially cooperative. Libya assisted Egypt in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War. Later, tensions arose due to Egypt's rapprochement with the west. Following the 1977 Libyan–Egyptian War, relations were suspended for twelve years. However, since 1989 relations have steadily improved. With the progressive lifting of UN and US sanctions from 2003 to 2008, the two countries have been working together to jointly develop their oil and natural gas industries.

On 15 May 2006 David Welch

, Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs

, announced that the U.S. had decided, after a 45-day comment period, to renew full diplomatic relations with Libya and remove Libya from the U.S. list of countries that foster terrorism.

During this announcement, it was also said that the U.S. has the intention of upgrading the U.S. liaison office in Tripoli into an embassy. The U.S. embassy in Tripoli opened in May, a product of gradual normalization of international relations after Libya accepted responsibility for the Pan Am 103 bombing. Libya's dismantling of its weapons of mass destruction was a major step towards this announcement.

The United States suspended its relations with Gaddafi's government indefinitely on 10 March 2011, when it announced it would begin treating the National Transitional Council

in Benghazi

as legitimate negotiating parties for the country's future.

On 15 July 2011, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton

announced that America would now recognize the National Transitional Council

as the legitimate government of Libya, thus severing any and all recognition of Gaddafi's government as legitimate.

, and to strengthen its policy of non-alignment

by establishing relations with a notable country not aligned with the Western Bloc

.

, as have all international organisations to which Libya is a member. Only the 8 countries of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas and the African countries of Namibia

and Zimbabwe

have explicitly continued to denounce the NTC and insist on Gaddafi's legitimacy.

Western world

The Western world, also known as the West and the Occident , is a term referring to the countries of Western Europe , the countries of the Americas, as well all countries of Northern and Central Europe, Australia and New Zealand...

(especially the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, although relations were normalized in the early 21st century prior to the 2011 Libyan civil war

2011 Libyan civil war

The 2011 Libyan civil war was an armed conflict in the North African state of Libya, fought between forces loyal to Colonel Muammar Gaddafi and those seeking to oust his government. The war was preceded by protests in Benghazi beginning on 15 February 2011, which led to clashes with security...

) and by Gaddafi's activist policies in the Middle East

Middle East

The Middle East is a region that encompasses Western Asia and Northern Africa. It is often used as a synonym for Near East, in opposition to Far East...

and Africa

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

, including his financial and military support for numerous paramilitary and rebel groups.

Timeline

Since 1969, ColonelColonel

Colonel , abbreviated Col or COL, is a military rank of a senior commissioned officer. It or a corresponding rank exists in most armies and in many air forces; the naval equivalent rank is generally "Captain". It is also used in some police forces and other paramilitary rank structures...

Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar Gaddafi or "September 1942" 20 October 2011), commonly known as Muammar Gaddafi or Colonel Gaddafi, was the official ruler of the Libyan Arab Republic from 1969 to 1977 and then the "Brother Leader" of the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya from 1977 to 2011.He seized power in a...

has determined Libya

Libya

Libya is an African country in the Maghreb region of North Africa bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad and Niger to the south, and Algeria and Tunisia to the west....

's foreign policy. His principal foreign policy goals have been Arab unity, elimination of Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

, advancement of Islam

Islam

Islam . The most common are and . : Arabic pronunciation varies regionally. The first vowel ranges from ~~. The second vowel ranges from ~~~...

, support for Palestinians

Palestinian people

The Palestinian people, also referred to as Palestinians or Palestinian Arabs , are an Arabic-speaking people with origins in Palestine. Despite various wars and exoduses, roughly one third of the world's Palestinian population continues to reside in the area encompassing the West Bank, the Gaza...

, elimination of outside—particularly Western—influence in the Middle East

Middle East

The Middle East is a region that encompasses Western Asia and Northern Africa. It is often used as a synonym for Near East, in opposition to Far East...

and Africa

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

, and support for a range of "revolutionary" causes.

After the 1969 coup

Coup d'état

A coup d'état state, literally: strike/blow of state)—also known as a coup, putsch, and overthrow—is the sudden, extrajudicial deposition of a government, usually by a small group of the existing state establishment—typically the military—to replace the deposed government with another body; either...

, U.S.-Libyan relations became increasingly strained because of Libya's foreign policies supporting international terrorism

Terrorism

Terrorism is the systematic use of terror, especially as a means of coercion. In the international community, however, terrorism has no universally agreed, legally binding, criminal law definition...

and subversion against moderate Arab and African governments. Gaddafi closed American

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

and British

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

bases on Libyan territory and partially nationalized

Nationalization

Nationalisation, also spelled nationalization, is the process of taking an industry or assets into government ownership by a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to private assets, but may also mean assets owned by lower levels of government, such as municipalities, being...

all foreign oil and commercial interests in Libya.

1970s

ExportExport

The term export is derived from the conceptual meaning as to ship the goods and services out of the port of a country. The seller of such goods and services is referred to as an "exporter" who is based in the country of export whereas the overseas based buyer is referred to as an "importer"...

controls on military

Military

A military is an organization authorized by its greater society to use lethal force, usually including use of weapons, in defending its country by combating actual or perceived threats. The military may have additional functions of use to its greater society, such as advancing a political agenda e.g...

equipment and civil aircraft

Civil aviation

Civil aviation is one of two major categories of flying, representing all non-military aviation, both private and commercial. Most of the countries in the world are members of the International Civil Aviation Organization and work together to establish common standards and recommended practices...

were imposed during the 1970s.

On 11 June 1972, Gaddafi announced that any Arab wishing to volunteer for Palestinian armed groups "can register his name at any Libyan embassy will be given adequate training for combat". He also promised financial support for attacks. In response, the United States withdrew its ambassador

Ambassadors from the United States

This is a list of ambassadors of the United States to individual nations of the world, to international organizations, to past nations, and ambassadors-at-large.Ambassadors are nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate...

. On 7 October 1972, Gaddafi praised the Lod Airport massacre

Lod Airport massacre

The Lod Airport massacre was a terrorist attack that occurred on May 30, 1972, in which three members of the Japanese Red Army, on behalf of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine , killed 26 people and injured 80 others at Tel Aviv's Lod airport...

, carried out by the Japanese Red Army

Japanese Red Army

The was a Communist terrorist group founded by Fusako Shigenobu early in 1971 in Lebanon. It sometimes called itself Arab-JRA after the Lod airport massacre...

, and demanded Palestinian terrorist groups to carry out similar attacks.

Gaddafi played a key role in promoting the use of oil embargo

Embargo

An embargo is the partial or complete prohibition of commerce and trade with a particular country, in order to isolate it. Embargoes are considered strong diplomatic measures imposed in an effort, by the imposing country, to elicit a given national-interest result from the country on which it is...

es as a political weapon for challenging the West, hoping that an oil price rise and embargo in 1973 would persuade the West—especially the United States—to end support for Israel. Gaddafi rejected both Soviet communism

Communism

Communism is a social, political and economic ideology that aims at the establishment of a classless, moneyless, revolutionary and stateless socialist society structured upon common ownership of the means of production...

and Western capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

and claimed he was charting a middle course for his government.

In 1973 the Irish Naval Service intercepted the vessel Claudia in Irish territorial waters, which carried Soviet arms from Libya to the Provisional IRA.

In 1976 after a series of terror attacks by the Provisional IRA, Gaddafi announced that "the bombs which are convulsing Britain and breaking its spirit are the bombs of Libyan people. We have sent them to the Irish revolutionaries so that the British will pay the price for their past deeds".

Together with Fidel Castro

Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz is a Cuban revolutionary and politician, having held the position of Prime Minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976, and then President from 1976 to 2008. He also served as the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba from the party's foundation in 1961 until 2011...

and other Communist leaders, Gaddafi supported Soviet

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

protege Haile Mariam Mengistu, the military ruler of Ethiopia

Ethiopia

Ethiopia , officially known as the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a country located in the Horn of Africa. It is the second-most populous nation in Africa, with over 82 million inhabitants, and the tenth-largest by area, occupying 1,100,000 km2...

, who was later convicted for a genocide

Genocide

Genocide is defined as "the deliberate and systematic destruction, in whole or in part, of an ethnic, racial, religious, or national group", though what constitutes enough of a "part" to qualify as genocide has been subject to much debate by legal scholars...

that killed thousands.

In October 1978, Gaddafi sent Libyan troops to aid Idi Amin

Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada was a military leader and President of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. Amin joined the British colonial regiment, the King's African Rifles in 1946. Eventually he held the rank of Major General in the post-colonial Ugandan Army and became its Commander before seizing power in the military...

in the Uganda-Tanzania War

Uganda-Tanzania War

The Uganda–Tanzania War was fought between Uganda and Tanzania in 1978–1979, and led to the overthrow of Idi Amin's regime...

when Amin tried to annex the northern Tanzania

Tanzania

The United Republic of Tanzania is a country in East Africa bordered by Kenya and Uganda to the north, Rwanda, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo to the west, and Zambia, Malawi, and Mozambique to the south. The country's eastern borders lie on the Indian Ocean.Tanzania is a state...

n province of Kagera

Kagera Region

Kagera Region is located in the northwestern corner of Tanzania. Bukoba, Kagera Region's capital, is a fast growing town situated on the shore of Lake Victoria. Bukoba lies only 1 degree south of the Equator and is Tanzania's second largest port on the lake. The region neighbors Uganda, Rwanda and...

, and Tanzania counterattacked. Amin lost the battle and later fled to exile in Libya, where he remained for almost a year.

Libya also was one of the main supporters of the Polisario Front

Polisario Front

The POLISARIO, Polisario Front, or Frente Polisario, from the Spanish abbreviation of Frente Popular de Liberación de Saguía el Hamra y Río de Oro is a Sahrawi rebel national liberation movement working for the independence of Western Sahara from Morocco...

in the former Spanish Sahara

Spanish Sahara

Spanish Sahara was the name used for the modern territory of Western Sahara when it was ruled as a territory by Spain between 1884 and 1975...

– a nationalist

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

group dedicated to ending Spanish colonialism

Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire comprised territories and colonies administered directly by Spain in Europe, in America, Africa, Asia and Oceania. It originated during the Age of Exploration and was therefore one of the first global empires. At the time of Habsburgs, Spain reached the peak of its world power....

in the region. The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic

Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic

The Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic is a partially recognised state that claims sovereignty over the entire territory of Western Sahara, a former Spanish colony. SADR was proclaimed by the Polisario Front on February 27, 1976, in Bir Lehlu, Western Sahara. The SADR government controls about...

(SADR) was proclaimed by Polisario on 28 February 1976, and Libya began to recognize the SADR

Foreign relations of Western Sahara

Western Sahara, formerly the Spanish colony of Spanish Sahara, is a disputed territory claimed by both the Kingdom of Morocco and the Polisario Front...

as the legitimate government of Western Sahara

Western Sahara

Western Sahara is a disputed territory in North Africa, bordered by Morocco to the north, Algeria to the northeast, Mauritania to the east and south, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. Its surface area amounts to . It is one of the most sparsely populated territories in the world, mainly...

starting 15 April 1980. It is still common for Sahrawi students to attend their schooling in Libya.

Gaddafi also aided Jean-Bedel Bokassa

Jean-Bédel Bokassa

Jean-Bédel Bokassa , a military officer, was the head of state of the Central African Republic and its successor state, the Central African Empire, from his coup d'état on 1 January 1966 until 20 September 1979...

, the self-proclaimed emperor of the short-lived Central African Empire

Central African Empire

The Central African Empire was a short-lived, self-declared autocratic monarchy that replaced the Central African Republic and was, in turn, replaced by the restoration of the republic. The empire was formed when Jean-Bédel Bokassa, President of the republic, declared himself Emperor Bokassa I on...

.

U.S. embassy

Diplomatic mission

A diplomatic mission is a group of people from one state or an international inter-governmental organisation present in another state to represent the sending state/organisation in the receiving state...

staff members were withdrawn from Tripoli after a mob attacked and set fire to the embassy in December 1979. The U.S. government

Federal government of the United States

The federal government of the United States is the national government of the constitutional republic of fifty states that is the United States of America. The federal government comprises three distinct branches of government: a legislative, an executive and a judiciary. These branches and...

declared Libya a "state sponsor of terrorism

State-sponsored terrorism

State-sponsored terrorism is a term used to describe terrorism sponsored by nation-states. As with terrorism, the precise definition, and the identification of particular examples, are subjects of heated political dispute...

" on 29 December 1979.

1980s

In May 1981, the U.S. government closed the Libyan "people's bureau" (embassy) in Washington, D.C. and expelled the Libyan staff in response their conduct generally violating internationally accepted standards of diplomatic behavior.In August 1981, in the first incident

Gulf of Sidra incident (1981)

In the first Gulf of Sidra incident, 19 August 1981, two Libyan Su-22 Fitter attack aircraft were shot down by two American F-14 Tomcats off of the Libyan coast.-Background:...

of the Gulf of Sidra

Gulf of Sidra

Gulf of Sidra is a body of water in the Mediterranean Sea on the northern coast of Libya; it is also known as Gulf of Sirte or the Great Sirte or Greater Syrtis .- Geography :The Gulf of Sidra has been a major centre for tuna fishing in the Mediterranean for centuries...

, two Libyan jets fired on U.S. aircraft participating in a routine naval exercise over international waters

International waters

The terms international waters or trans-boundary waters apply where any of the following types of bodies of water transcend international boundaries: oceans, large marine ecosystems, enclosed or semi-enclosed regional seas and estuaries, rivers, lakes, groundwater systems , and wetlands.Oceans,...

of the Mediterranean Sea

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean surrounded by the Mediterranean region and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Anatolia and Europe, on the south by North Africa, and on the east by the Levant...

claimed by Libya. The U.S. planes returned fire and shot down the attacking Libyan aircraft. 11 On December 1981, the State Department

United States Department of State

The United States Department of State , is the United States federal executive department responsible for international relations of the United States, equivalent to the foreign ministries of other countries...

invalidated U.S. passport

Passport

A passport is a document, issued by a national government, which certifies, for the purpose of international travel, the identity and nationality of its holder. The elements of identity are name, date of birth, sex, and place of birth....

s for travel to Libya (a de facto

De facto

De facto is a Latin expression that means "concerning fact." In law, it often means "in practice but not necessarily ordained by law" or "in practice or actuality, but not officially established." It is commonly used in contrast to de jure when referring to matters of law, governance, or...

travel ban) and, for purposes of safety, advised all U.S. citizens in Libya to leave. In March 1982, the U.S. government prohibited imports of Libyan crude oil into the United States

and expanded the controls on U.S.-origin goods intended for export to Libya. Licenses were required for all transactions, except food and medicine. In March 1984, U.S. export controls were expanded to prohibit future exports to the Ra's Lanuf petrochemical complex. In April 1985, all Export-Import Bank

Export-Import Bank of the United States

The Export-Import Bank of the United States is the official export credit agency of the United States federal government. It was established in 1934 by an executive order, and made an independent agency in the Executive branch by Congress in 1945, for the purposes of financing and insuring...

financing was prohibited.

In October 1981, Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

ian President Anwar Sadat

Anwar Sadat

Muhammad Anwar al-Sadat was the third President of Egypt, serving from 15 October 1970 until his assassination by fundamentalist army officers on 6 October 1981...

was assassinated. Gaddafi applauded the murder and remarked that it was a "punishment" for Sadat's signing of the Camp David Accords

Camp David Accords

The Camp David Accords were signed by Egyptian President Anwar El Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin on September 17, 1978, following thirteen days of secret negotiations at Camp David. The two framework agreements were signed at the White House, and were witnessed by United States...

with the United States and Israel

Israel

The State of Israel is a parliamentary republic located in the Middle East, along the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea...

.

Yvonne Fletcher

WPC Yvonne Joyce Fletcher was a British police officer fatally shot during a protest outside the Libyan embassy at St. James's Square, London, in 1984. Fletcher, who had been on duty and deployed to police the protest, died shortly afterwards at Westminster Hospital...

, a British policewoman. The incident led to the breaking off of diplomatic relations

Diplomacy

Diplomacy is the art and practice of conducting negotiations between representatives of groups or states...

between the United Kingdom and Libya for over a decade. Two months later, Gaddafi asserted that he wanted his agents to assassinate dissident refugees, even if they were just on pilgrimage in the holy city of Mecca

Mecca

Mecca is a city in the Hijaz and the capital of Makkah province in Saudi Arabia. The city is located inland from Jeddah in a narrow valley at a height of above sea level...

—in August 1984, a Libyan plot in Mecca was thwarted by Saudi Arabian police.

After the December 1985 Rome and Vienna airport attacks

Rome and Vienna airport attacks

The Rome and Vienna airport attacks were two major terrorist strikes carried out on December 27, 1985.- The attacks :At 08:15 GMT, four gunmen walked to the shared ticket counter for Israel's El Al Airlines and Trans World Airlines at Leonardo da Vinci-Fiumicino Airport outside Rome, Italy, fired...

, which killed 19 and wounded around 140, Gaddafi indicated that he would continue to support the Red Army Faction, the Red Brigades, and the Irish Republican Army as long as European countries support anti-Gaddafi Libyans.

The Foreign Minister of Libya also called the massacres "heroic acts".

In 1986 Libyan state television announced that Libya was training suicide squads to attack American and European interests.

Gaddafi claimed the Gulf of Sidra

Gulf of Sidra

Gulf of Sidra is a body of water in the Mediterranean Sea on the northern coast of Libya; it is also known as Gulf of Sirte or the Great Sirte or Greater Syrtis .- Geography :The Gulf of Sidra has been a major centre for tuna fishing in the Mediterranean for centuries...

as his territorial water and his navy was involved in a conflict from January to March 1986.

On 5 April 1986, Libyan agents bombed "La Belle" nightclub in West Berlin

1986 Berlin discotheque bombing

The 1986 Berlin discotheque bombing was a terrorist attack on the La Belle discothèque in West Berlin, Germany, an entertainment venue that was commonly frequented by United States soldiers...

, killing three people and injuring 229 people who were spending the evening there. Gaddafi's plan was intercepted by Western intelligence. More detailed information was retrieved years later when Stasi

Stasi

The Ministry for State Security The Ministry for State Security The Ministry for State Security (German: Ministerium für Staatssicherheit (MfS), commonly known as the Stasi (abbreviation , literally State Security), was the official state security service of East Germany. The MfS was headquartered...

archives were investigated by the reunited Germany. Libyan agents who had carried out the operation from the Libyan embassy in East Germany were prosecuted by reunited Germany in the 1990s.

Germany and the United States learned that the bombing in West Berlin had been ordered from Tripoli. On 14 April 1986, the United States carried out Operation El Dorado Canyon

Operation El Dorado Canyon

The 1986 United States bombing of Libya, code-named Operation El Dorado Canyon, comprised the joint United States Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps air-strikes against Libya on April 15, 1986. The attack was carried out in response to the 1986 Berlin discotheque bombing.-Origins:Shortly after his...

against Gaddafi and members of his regime. Air defenses, three army bases, and two airfields in Tripoli

Tripoli

Tripoli is the capital and largest city in Libya. It is also known as Western Tripoli , to distinguish it from Tripoli, Lebanon. It is affectionately called The Mermaid of the Mediterranean , describing its turquoise waters and its whitewashed buildings. Tripoli is a Greek name that means "Three...

and Benghazi

Benghazi

Benghazi is the second largest city in Libya, the main city of the Cyrenaica region , and the former provisional capital of the National Transitional Council. The wider metropolitan area is also a district of Libya...

were bombed. The surgical strikes failed to kill Gaddafi but he lost a few dozen military officers.

Gaddafi announced that he had won a spectacular military victory over the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

and the country was officially renamed the "Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriyah". However, his speech appeared devoid passion and even the "victory" celebrations appeared unusual. Criticism of Gaddafi by ordinary Libyan citizens became more bold, such as defacing of Gaddafi posters. The raids against Gaddafi had brought the regime to its the weakest point in 17 years.

The Chadian–Libyan conflict (1978–1987) ended in disaster for Libya in 1987 with the Toyota War

Toyota War

The Toyota War is the name commonly given to the last phase of the Chadian–Libyan conflict, which took place in 1987 in Northern Chad and on the Libyan-Chadian border. It takes its name from the Toyota pickup trucks used as technicals to provide mobility for the Chadian troops as they fought...

. France supported Chad in this conflict and two years later on 19 September 1989, a French airliner, UTA Flight 772

UTA Flight 772

UTA Flight 772 of the French airline Union des Transports Aériens was a scheduled flight operating from Brazzaville in the Republic of Congo, via N'Djamena in Chad, to Paris CDG airport in France....

, was destroyed by an in-flight explosion for which Libyan agents were convicted in absentia. The incident bore close similarities to the destruction of Pan Am Flight 103

Pan Am Flight 103

Pan Am Flight 103 was Pan American World Airways' third daily scheduled transatlantic flight from London Heathrow Airport to New York's John F. Kennedy International Airport...

(the Lockerbie Bombing) a year earlier. The downing of these two airliners along with the 1986 Berlin discotheque bombing

1986 Berlin discotheque bombing

The 1986 Berlin discotheque bombing was a terrorist attack on the La Belle discothèque in West Berlin, Germany, an entertainment venue that was commonly frequented by United States soldiers...

seemed to establish a pattern of reprisal

Reprisal

In international law, a reprisal is a limited and deliberate violation of international law to punish another sovereign state that has already broken them. Reprisals in the laws of war are extremely limited, as they commonly breached the rights of civilians, an action outlawed by the Geneva...

attacks—in the form of terrorist bombings—by Libya or at least Libyan agents. The United Nations imposed sanctions on Libya for these two acts (with UN Security Council Resolutions 731

United Nations Security Council Resolution 731

UN Security Council Resolution 731, adopted unanimously on 21 January 1992, after recalling resolutions 286 and 635 which condemned acts of terrorism, the Council expressed its concern over the results of invesigations into the destruction of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland, and UTA...

, 748

United Nations Security Council Resolution 748

UN Security Council Resolution 748, adopted unanimously on 31 March 1992, after reaffirming Resolution 731 , the Council decided, under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter, that the Government of Libya must now comply with requests from investigations relating to the destruction of Pan Am...

and 883

United Nations Security Council Resolution 883

UN Security Council Resolution 883, adopted on 11 November 1993, after reaffirming resolutions 731 and 748 , the Council noted that, twenty months later, Libya had not complied with previous Security Council resolutions and as a consequence imposed further international sanctions on the...

). The UN eventually lifted these sanctions (with Resolution 1506

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1506

United Nations Security Council Resolution 1506, adopted on September 12, 2003, after recalling resolutions 731 , 748 , 883 and 1192 concerning the destruction of Pan Am Flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland in 1988 and UTA Flight 772 over Niger in 1989, the Council lifted sanctions against Libya...

) in 2003 when Libya "accepted responsibility for the actions of its officials, renounced terrorism and arranged for payment of appropriate compensation for the families of the victims." In 2008 Libya established a fund to compensate victims of these three terrorist acts (and the 1986 US bombing of Tripoli and Benghazi).

Gaddafi fueled a number of Islamist and communist terrorist groups in the Philippines

Philippines

The Philippines , officially known as the Republic of the Philippines , is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam...

, as well as paramilitaries in Oceania

Oceania

Oceania is a region centered on the islands of the tropical Pacific Ocean. Conceptions of what constitutes Oceania range from the coral atolls and volcanic islands of the South Pacific to the entire insular region between Asia and the Americas, including Australasia and the Malay Archipelago...

. He attempted to radicalize New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

's Maori people in a failed effort to destabilise the U.S. ally. In Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

, he financed trade unions and some politicians who opposed the ANZUS

ANZUS

The Australia, New Zealand, United States Security Treaty is the military alliance which binds Australia and New Zealand and, separately, Australia and the United States to cooperate on defence matters in the Pacific Ocean area, though today the treaty is understood to relate to attacks...

alliance with the United States. In May 1987, Australia deported diplomats and broke off relations with Libya because of its activities in Oceania.

In late 1987 French authorities stopped a merchant vessel, the MV Eksund, which was delivering a 150 ton Libyan arms shipment to European terrorist groups.

In 1988, Libya was found to be in the process of constructing a chemical weapons plant at Rabta, a plant which became the largest such facility in the Third World

Third World

The term Third World arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either capitalism and NATO , or communism and the Soviet Union...

.

Libya's relationship with the former Soviet Union

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union , officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics , was a constitutionally socialist state that existed in Eurasia between 1922 and 1991....

involved massive Libyan arms purchases from the Soviet bloc

Eastern bloc

The term Eastern Bloc or Communist Bloc refers to the former communist states of Eastern and Central Europe, generally the Soviet Union and the countries of the Warsaw Pact...

and the presence of thousands of east bloc advisers. Libya's use—and heavy loss—of Soviet-supplied weaponry in its war with Chad

Chad

Chad , officially known as the Republic of Chad, is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to the north, Sudan to the east, the Central African Republic to the south, Cameroon and Nigeria to the southwest, and Niger to the west...

was a notable breach of an apparent Soviet-Libyan understanding not to use the weapons for activities inconsistent with Soviet objectives. As a result, Soviet-Libyan relations reached a nadir in mid-1987.

In January 1989, there was another encounter

Gulf of Sidra incident (1989)

The second Gulf of Sidra incident occurred on 4 January 1989 when two US F-14 Tomcats shot down two Libyan MiG-23 Flogger-Es that gave all appearances of attempting to engage them, as had happened seven years prior in the first Gulf of Sidra incident ....

over the Gulf of Sidra between U.S. and Libyan aircraft which resulted in the downing of two Libyan jets.

1990s

In 1991, two Libyan intelligence agents were indicted by prosecutors in the United States and United Kingdom for their involvement in the December 1988 bombing of Pan Am Flight 103Pan Am Flight 103

Pan Am Flight 103 was Pan American World Airways' third daily scheduled transatlantic flight from London Heathrow Airport to New York's John F. Kennedy International Airport...

. Six other Libyans were put on trial in absentia for the 1989 bombing of UTA Flight 772

UTA Flight 772

UTA Flight 772 of the French airline Union des Transports Aériens was a scheduled flight operating from Brazzaville in the Republic of Congo, via N'Djamena in Chad, to Paris CDG airport in France....

over Chad

Chad

Chad , officially known as the Republic of Chad, is a landlocked country in Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to the north, Sudan to the east, the Central African Republic to the south, Cameroon and Nigeria to the southwest, and Niger to the west...

and Niger

Niger

Niger , officially named the Republic of Niger, is a landlocked country in Western Africa, named after the Niger River. It borders Nigeria and Benin to the south, Burkina Faso and Mali to the west, Algeria and Libya to the north and Chad to the east...

. The UN Security Council demanded that Libya surrender the suspects, cooperate with the Pan Am 103 and UTA 772 investigations, pay compensation to the victims' families, and cease all support for terrorism. Libya's refusal to comply led to the approval of Security Council Resolution 748

United Nations Security Council Resolution 748

UN Security Council Resolution 748, adopted unanimously on 31 March 1992, after reaffirming Resolution 731 , the Council decided, under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter, that the Government of Libya must now comply with requests from investigations relating to the destruction of Pan Am...

on 31 March 1992, imposing international sanctions

International sanctions

International sanctions are actions taken by countries against others for political reasons, either unilaterally or multilaterally.There are several types of sanctions....

on the state designed to bring about Libyan compliance. Continued Libyan defiance led to further sanctions by the UN against Libya in November 1993.

After the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact

Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Treaty Organization of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance , or more commonly referred to as the Warsaw Pact, was a mutual defense treaty subscribed to by eight communist states in Eastern Europe...

and the Soviet Union, Libya concentrated on expanding diplomatic ties with Third World

Third World

The term Third World arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either capitalism and NATO , or communism and the Soviet Union...

countries and increasing its commercial links with Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

and East Asia

East Asia

East Asia or Eastern Asia is a subregion of Asia that can be defined in either geographical or cultural terms...

. Following the imposition of U.N. sanctions in 1992, these ties significantly diminished. Following a 1998 Arab League meeting in which fellow Arab states decided not to challenge U.N. sanctions, Gaddafi announced that he was turning his back on pan-Arab ideas, one of the fundamental tenets of his philosophy.

Instead, Libya pursued closer bilateral ties, particularly with Egypt

Egypt

Egypt , officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, Arabic: , is a country mainly in North Africa, with the Sinai Peninsula forming a land bridge in Southwest Asia. Egypt is thus a transcontinental country, and a major power in Africa, the Mediterranean Basin, the Middle East and the Muslim world...

and Northwest African nations Tunisia

Tunisia

Tunisia , officially the Tunisian RepublicThe long name of Tunisia in other languages used in the country is: , is the northernmost country in Africa. It is a Maghreb country and is bordered by Algeria to the west, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Its area...

and Morocco

Morocco

Morocco , officially the Kingdom of Morocco , is a country located in North Africa. It has a population of more than 32 million and an area of 710,850 km², and also primarily administers the disputed region of the Western Sahara...

. It also has sought to develop its relations with Sub-Saharan Africa

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

, leading to Libyan involvement in several internal African disputes in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Sudan

Sudan

Sudan , officially the Republic of the Sudan , is a country in North Africa, sometimes considered part of the Middle East politically. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the...

, Somalia

Somalia