Collaboration during World War II

Encyclopedia

Within nations occupied by the Axis Powers

, some citizens, driven by nationalism

, ethnic hatred

, anti-communism

, anti-Semitism

or opportunism

, knowingly engaged in collaboration with the Axis Powers during World War II. Some of these collaborationists committed the worst crimes and atrocities of the Holocaust.

Collaboration ranged from urging the civilian population to remain calm and accept foreign occupation without conflict, organizing trade, production, financial and economic support to joining various branches of the armed forces of the Axis powers

or special "national" military units fighting under their command.

.

The Jews were considered to be worst of all nations and thus unfit for cooperation, although some were used in concentration camps as Kapos

to report on other prisoners and enforce order. Others governed ghettos and helped organize deportation

s to extermination camps (Jewish Ghetto Police

).

created the 21st Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Skanderbeg (1st Albanian)

manned by Albanian

and Kosovar Albanian volunteers . By June 1944, the military value was deemed low in lieu of partisan aggression and by November 1944 it was disbanded. The remaining cadre, now called Kampfgruppe Skanderbeg, was transferred to the Prinz Eugen Division where they successfully participated in actions against Tito's partisans in December 1944. The emblem of the division was a black Albanian eagle.

battalion

of Wehrmacht

, manned by Walloon Belgians, took part in anti-guerrilla actions in the occupied territory of the USSR from August 1941-February 1942. In May 1943, the battalion was transformed into the 5th SS Volunteer Sturmbrigade Wallonien and sent to the Eastern Front

. In the autumn, the brigade had been transformed into 28th SS Volunteer Grenadier Division Wallonien. Its remnants surrendered to British troops in the final days of war. Flemish Belgian collaborators were organized first into the 6th SS Volunteer Brigade

and later the 27th SS Infantry (Grenadier) Division. Belgians served in the German forces from mid-1941 until the end of the war.

in 1932, followed by the East Hebei Autonomous Council

in 1935. Similar to Manchukuo

in its supposed ethnic identity, Mengjiang

(Mengkukuo) was set up in late 1936. Wang Kemin

's collaborationist Provisional Government of the Republic of China was set up in Beiping in 1937 following the start of full-scale military operations between China and Japan

, another puppet regime was the Reformed Government of the Republic of China, setup in Nanjing

in 1938. The Wang Jingwei

collaborationist government, established in 1940, "consolidated" these regimes, though in reality neither Wang's government nor the constituent governments had any autonomy, although the military of the Wang Jingwei Government

was equipped by the Japanese with planes, cannons, tanks, boats, and German-style stahlhelm

(already widely used by the National Revolutionary Army

, the "official" army of the Republic of China

).

The military forces of these puppet regimes, known collectively as the Collaborationist Chinese Army

, numbered more than a million at their height, with some estimates that the number exceeded 2 million conscripts. Great number of collaborationist troops were men originally serving in warlord forces within the National Revolutionary Army who had defected when facing both Communists and Japanese as enemies. Although its manpower was very large, the soldiers were very ineffective compared to NRA soldiers due to low morale for being considered as "Hanjian

". Although certain collaborationist forces had limited battlefield presence during the Second Sino-Japanese War

, most were relegated to behind-the-line duties.

The Wang Jingwei government was disbanded after Japanese surrender to Allies in 1945, and Manchukuo and Mengjiang were destroyed by Soviet troops in the invasion of Manchuria.

Denmark, in direct violation of a German-Danish treaty of non-aggression signed the previous year. After two hours the Danish government surrendered

, believing that resistance was useless and hoping to work out an advantageous agreement with Germany.

As a result of the cooperative attitude of the Danish authorities, German officials claimed that they would "respect Danish sovereignty and territorial integrity, as well as neutrality." The German authorities were inclined towards lenient terms with Denmark for several reasons. These factors allowed Denmark a very favorable relationship with Nazi Germany. The government remained intact and the parliament

continued to function more or less as it had before. They were able to maintain much of their former control over domestic policy. Danish public opinion generally backed the new government, particularly after the fall of France in June 1940. There was a general feeling that the unpleasant reality of German occupation must be confronted in the most realistic way possible, given the international situation. Newspaper articles and news reports "which might jeopardize German-Danish relations" were outlawed. After the assault on the Soviet Union, Operation Barbarossa

, Denmark joined the Anti-Comintern Pact

, together with the fellow Nordic

state of Finland

; the Communist Party

was banned in Denmark. Industrial production

and trade was, partly due to geopolitical reality and economic necessity, redirected toward Germany. Many government officials saw expanded trade with Germany as vital to maintaining social order in Denmark. Increased unemployment

and poverty was feared to lead to more of open revolt within the country, since Danes tended to blame all negative developments on the Germans. It was feared that any revolt would result in a crackdown by the German authorities.

In return for these concessions, the Danish cabinet rejected German demands for legislation discriminating against Denmark's Jewish minority. Demands to introduce the death penalty were likewise rebuffed and so were German demands to allow German military courts jurisdiction over Danish citizens. Denmark also rejected demands for the transfer of Danish army units to German military use. Throughout the years of its hold on power, the government consistently refused to accept German demands regarding the Jews. The authorities would not enact special laws concerning Jews, and their civil rights remained equal with those of the rest of the population. German authorities became increasingly exasperated with this position but concluded that any attempt to remove or mistreat Jews would be "politically unacceptable." Even the Gestapo

officer Dr. Werner Best

, plenipotentiary in Denmark from November 1942, believed that any attempt to remove the Jews would be enormously disruptive to the relationship between the two governments and recommended against any action concerning the Jews of Denmark.

On 29 June 1941, days after the invasion of the USSR

, Frikorps Danmark

(Free Corps Denmark) was founded as a corps of Danish volunteers to fight against the Soviet Union. Frikorps Danmark was set up at the initiative of the SS and DNSAP who approached Lieutenant-Colonel C.P. Kryssing of the Danish army shortly after the invasion of the USSR had begun. The Nazi paper Fædrelandet proclaimed the creation of the corps on 29 June 1941. According to Danish law, it was not illegal to join a foreign army, but active recruiting on Danish soil was illegal. The SS disregarded this law and began recruiting efforts — predominantly recruiting Danish Nazis and members of the German-speaking minority.

did not have complete freedom of action, it exercised a significant measure of autonomy, within the framework of German policy, political, racial and economic. Thus, the Directors exercised their powers pursuant to the laws and regulations of the Republic of Estonia, but only to the extent that these had not been repealed or amended by the German military command. The Director's position was voluntary. The Self-Administration’s autonomy enabled it to maintain police structures that

cooperated with the Germans in rounding up and

killing Jews and Roma, and in seeking out

and killing Estonians deemed to be opponents of the

occupiers, and which were ultimately incorporated

into the Estonian Security Police and SD

. It also extended to the

unlawful conscription

of Estonians for forced labor

or for military service

under German command.

The Estonian Security Police and SD, the 286th, 287th and 288th Estonian Auxiliary Police

Battalions, and 2.5–3% of Estonian Omakaitse

(Home Guard) militia

units (approximately between 1000 and 1200 men) were directly involved in criminal acts, taking part in the round-up, guarding or killing of 400–1000 Roma people and 6000 Jews in the concentration camps of Pskov region in Russia and the Jägala

, Vaivara, Klooga

, and Lagedi

camps in Estonia. Guarded by the above listed formations, 15,000 Soviet POW died in Estonia, part of them because of neglect and mistreatment and part executed.

The Vichy government, headed by Marshall Philippe Pétain

The Vichy government, headed by Marshall Philippe Pétain

and Pierre Laval

, actively collaborated in the extermination of the European Jews. It also participated in Porrajmos, the extermination of Rom people, and in the extermination of other "undesirables." Vichy opened up a series of concentration camps in France where it interned Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, political opponents, etc. Directed by René Bousquet

, the French police helped in the deportation of 76,000 Jews to the extermination camps. In 1995, President Jacques Chirac

officially recognized the responsibility of the French state for the deportation of Jews during the war, in particular the more than 13,000 victims the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup of July 1942, during which Laval decided, by his own, to deport children along with their parents. Only 2,500 of the deported Jews survived the war. The 1943 Battle of Marseille

was another event during which the French police assisted the Gestapo in a massive raid, which included an urban reshaping plan involving the destruction of a whole neighbourhood in the popular Old Port. Some few collaborators were tried in the 1980s for crimes against humanity (Paul Touvier

, etc.), while Maurice Papon

, who had become after the war prefect of police of Paris (a function in which he illustrated himself during the 1961 Paris massacre) was convicted in 1998 for crimes against humanity. He had been Budget Minister under President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing

. Other collaborators, such as Emile Dewoitine

, managed to have important functions after the war (Dewoitine was eventually named head of Aérospatiale

, the firm which created the Concorde plane). Debates concerning state collaboration remain, in 2008, very strong in France.

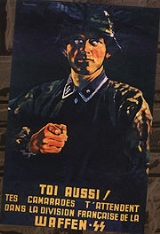

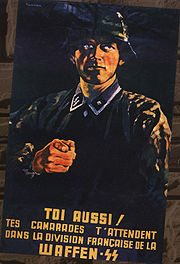

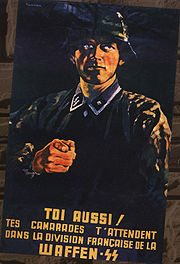

The French volunteers formed the Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism

and the Legion Imperiale

, in 1945 the 33rd Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Charlemagne (1st French)

, which was among the final defenders of Berlin

.

and François Debeauvais

had longstanding links with Nazi Germany because of the their fascist and Nordicist ideologies, linked to the belief that the Bretons were a "pure" Celtic branch of the Aryan-Nordic race. At the outbreak of the war they left France and declared support for Germany. After 1940, they returned and their supporters such as Célestin Lainé

and Yann Goulet

organized militias that worked in collaboration with the Germans. Lainé and Goulet later took refuge in Ireland.

invasion of Greece, a Nazi-held government was put in place. All three quisling

prime ministers, (Georgios Tsolakoglou

, Konstantinos Logothetopoulos

and Ioannis Rallis

), cooperated with the Axis authorities. Although their administrations did not directly assist the occupation forces, they did instigate suppressive measures, the most significant of which was the encouragement and, with the consent of the German forces, the creation of armed "anti-communist" and "anti-gangster" paramilitary organisations such as X

, the Security Battalions

and others. Moreover, small but active Greek National-Socialist parties, like the Greek National Socialist Party, or openly anti-semitic organisations, like the National Union of Greece

, helped German authorities fight the Resistance

, and identify and deport

Greek Jews.

About one thousand Greeks from Greece and more from the Soviet Union, ostensibly avenging their ethnic persecution from Soviet authorities, joined the Waffen-SS, mostly in Ukrainian divisions. A special case was that of the infamous Ukrainian-Greek Sevastianos Foulidis, a fanatical anti-communist who had been recruited by the Abwehr

as early as 1938 and became an official of the Wehrmacht, with extensive action in intelligence and agitation work in the Eastern front.

During the Axis occupation, a number of Cham Albanians

set up their own administration and militia in Thesprotia

, Greece, subservient to the fascist Balli Kombetar

organization, and actively collaborated first with the Italian and, subsequently, the German occupation forces, committing a number of atrocities. In one incident, on 29 September 1943, Nuri and Mazzar Dino, Albanian paramilitary leaders, instigated the mass execution of all Greek officials and notables

of Paramythia

.

was a war ally and then puppet state of Nazi Germany. The Hungarians played an active role in the murder of about 23,600 Jews (14,000–18,000 of whom were from Hungary) in Kamenets-Podolsk in late August 1941. and in the 1942 raid in Novi Sad

.

Radical Hungarian governments—mainly the puppet government of Döme Sztójay

, appointed after the German occupation—actively participated in the Holocaust.

The Arrow Cross Party

was a Hungarian Nazi party led by Ferenc Szálasi

which ruled Hungary from 15 October 1944-January 1945 following the German SS coup

in Budapest

. During its short rule, 80,000 Jews were deported from Hungary to their deaths. Out of 825,000 Hungarian Jews before the war, only 260,000 survived.

, captured by the Axis

in North Africa

. Many, if not most, of the Indian volunteers who switched sides to fight with the German Army and against the British were strongly nationalistic supporters of the exiled, anti-British, former president of the Indian National Congress

, Netaji (the Leader) Subhash Chandra Bose

. A Japanese supported sovereign

and autonomous state- the Azad Hind (Free India)

was also established with the Indian National Army

as its military force. See also the Tiger Legion.

in November 1943 were Sukarno

and Mohammad Hatta

. Sukarno

actively recruited and organised Indonesian Romusha

forced labour. They succeeded respectively to become the founding President of the Republic of Indonesia and Vice President of the Republic of Indonesia in August 1945.

of Nazi Germany

led by the "Leader of the Nation" (Duce) and "Minister of Foreign Affairs" Benito Mussolini

. The RSI exercised official sovereignty

in northern Italy

but was largely dependent on the German Army (Wehrmacht Heer) to maintain control. The state was informally known as the "Salò Republic" (Repubblica di Salò) because the RSI's Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Mussolini) was headquartered in Salò

, a small town on Lake Garda

. The Italian Social Republic was the second and last incarnation of a Fascist Italian state.

in summer 1941, German command, capitalizing on Latvian anti-Soviet sentiments, created the local voluntary troops (Schutzmannschaft or Schuma), to fight the Soviet partisans and serve as guards in concentration camps for Jews and Soviet

prisoners of war

. The group of the Latvian auxiliary police

known as Arājs Commando

murdered about 26,000 Jews, mainly in November and December 1941.

and in exile believed Germany would grant the country autonomy along the lines of the status of the Slovakia protectorate. German intelligence Abwehr

believed it had control of the Lithuanian Activist Front

, a pro-German organization based in the Lithuanian embassy in Berlin

. The German Nazis allowed Lithuanians to form the Provisional Government

, but did not recognize it diplomatically and did not allow Lithuanian ambassador Kazys Škirpa

to become the Prime Minister. Once German military rule in Lithuania was replaced by a German civil authority, the Provisional Government was disbanded.

Rogue

units organised by Algirdas Klimaitis

and led by SS Brigadeführer

Walter Stahlecker started pogrom

s in and around Kaunas

on June 25, 1941. Lithuanian collaborators would become involved in the murders of hundreds of thousands of Jews and Poles.

In 1941, the Lithuanian Security Police

(Lietuvos saugumo policija), subordinate to Nazi Germany's Security Police and Nazi Germany's Criminal Police, was created. Of the 26 local police battalions formed, 10 were involved in systematic extermination of Jews known as the Holocaust

. The Special SD and German Security Police Squad

in Vilnius

killed tens of thousands of Jews and ethnic Poles in Paneriai

(see Ponary massacre

) and other places. In Minsk, the 2nd Battalion shot about 9,000 Soviet prisoners of war, in Slutsk it massacred 5,000 Jews. In March 1942 in Poland, the 2nd Lithuanian Battalion carried out guard duty in the Majdanek

extermination camp. In July 1942, the 2nd Battalion participated in the deportation of Jews from the Warsaw ghetto

to a death camp. In August–October 1942, the police battalions formed from Lithuanians were in Ukraine: the 3rd in Molodechno, the 4th in Donetsk

, the 7th-в in Vinnitsa, the 11th in Korosten

, the 16th in Dnepropetrovsk, the 254th in Poltava

and the 255th in Mogilyov (Belarus). One of the battalions was also used to put down the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

in 1943.

; LTDF has self disbanded after it was ordered to act under Nazi command. Shortly before it was disbanded, LTDF suffered a major defeat from Polish partisans in the battle of Murowana Oszmianka

.

The participation of the local populace was a key factor in the Holocaust in Nazi-occupied Lithuania

which resulted in the near total destruction of Lithuanian Jews

living in the Nazi-controlled Lithuanian territories that would, from July 17, 1941, become the Generalbezirk Litauen of Reichskommissariat Ostland

. Out of approximately 210,000 Jews, (208,000 according to the Lithuanian pre-war statistical data) an estimated 195,000–196,000 perished before the end of World War II

(wider estimates are sometimes published); most from June to December 1941. The events that took place in the western regions of the USSR occupied by Nazi Germany

in the first weeks after the German invasion

(including Lithuania - see map) marked the sharp intensification of The Holocaust

.

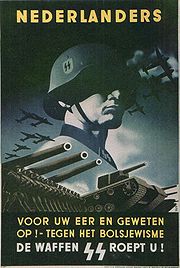

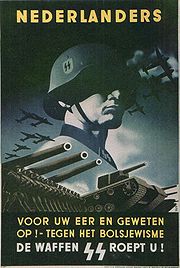

Thousands of Dutch volunteers joined the 11th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division Nordland

Thousands of Dutch volunteers joined the 11th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division Nordland

(created in February 1943). The division participated in fighting against the Soviet army and was crushed in the Battle of Berlin

in April–May 1945.

This was also the case for the 5th SS Panzergrenadier Division Wiking. It was involved in several major battles on the Eastern Front

.

SS-Freiwilligen Legion Niederlande, manned by Dutch volunteers and German officers, battled the Soviet army from 1941. In December 1943, it gained brigade status after fighting on the front around Leningrad. It was at Leningrad that the first European volunteer, a Dutchman, earned the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross

: Gerardus Mooyman

. In December 1944, it was transformed into the 23rd SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division Nederland and fought in Courland

and Pomerania

. It found its end scattered across Germany. 49. SS-Freiwilligen-Panzergrenadier-Regiment "de Ruyter" fought at the Oder and surrendered on 3 May 1945 to the Americans. 48. SS-Freiwilligen-Panzergrenadier-Regiment "General Seyffardt" however was split up into two groups. The first of these fought with Kampfgruppe Vieweger and went under in the fighting near Halbe

. The few remaining survivors were captured by the Soviets. The other half of "General Seyffart" fought with Korpsgruppe Tettau

and surrendered to the western Allies.

During the war famous actor and singer Johannes Heesters

made his career in Nazi-Germany, befriending high-ranking Nazis such as Joseph Goebbels

and living in houses stolen from wealthy Jews.

, the national government

, headed by Vidkun Quisling

, was installed by the Germans as a puppet regime during the occupation

, while king Haakon VII

and the previous government were in exile. He encouraged Norwegians

to serve as volunteers in the Waffen-SS

, collaborating in the deportation of Jews, and was responsible for the executions of Norwegian patriots

.

About 45,000 Norwegian collaborators joined the pro-Nazi party Nasjonal Samling (National Union), and some police units helped arrest many of Norway's Jews. It had very little support among the population at large and Norway was one of few countries where resistance during World War II

was widespread before the turning point of the war in 1942/43. After the war, Quisling and other collaborators were executed

. Quisling's name has become an international eponym

for traitor.

Arab nationalist

and a Muslim

religious leader, the Grand Mufti

of Jerusalem Mohammad Amin al-Husayni

worked for the Nazi Germany as a propagandist and a recruiter of Muslim volunteers for the Waffen SS and other units.

On November 28, 1941, Hitler officially received al-Husayni in Berlin. Hitler made a declaration that after "...the last traces of the Jewish-Communist European hegemony had been obliterated... the German army would... gain the southern exit of Caucasus... the Führer would offer the Arab world his personal assurance that the hour of liberation had struck. Thereafter, Germany's only remaining objective in the region would be limited to the Vernichtung des... Judentums ['destruction of the Jewish element', sometimes taken to be a euphemism for 'annihilation of the Jews'] living under British protection in Arab lands.."

The Mufti spent the remainder of the war assisting with the formation of Muslim Waffen SS units in the Balkans

and the formation of schools and training centers for imam

s and mullah

s who would accompany the Muslim SS and Wehrmacht units. Beginning in 1943, al-Husayni was involved in the organization and recruitment of Bosnian Muslims

into several divisions. The largest of which was the 13th "Handschar" division

of 21,065 men.

In 1944, al-Husayni sponsored an unsuccessful chemical warfare

assault on the Jewish community in Palestine. Five parachutists were supplied with maps of Tel Aviv

, canisters of a German–manufactured "fine white powder," and instructions from the Mufti to dump chemicals into the Tel Aviv water system

. District police commander Fayiz Bey Idrissi later recalled, "The laboratory report stated that each container held enough poison to kill 25,000 people, and there were at least ten containers."

The German Zionist organization concluded an economic agreement called the Haavara (Transfer in Hebrew) Agreement with Nazi Germany in 1933. The Haavara agreement

would last by most accounts until 1941. PBS states: "Haavara (Transfer) was a company established in 1935 as the result of an agreement between the Jewish Agency (the official Jewish executive in Palestine) and the Nazi regime. The agreement was designed to facilitate Jewish emigration to Palestine. Though the Nazis had ordered Jewish emigrants to surrender most of their property before leaving Germany, the Ha'avara agreement

let them retain some of their assets by transferring them to Palestine as German export goods. Approximately 50,000 Jews emigrated to Palestine under this arrangement." The Nazi German official Baron von Mildenstein was a guest of Jews in Palestine in 1933 and a commemorative medal was struck marking the occasion for the Nazi propaganda publication "Der Angriff"; wherein one side of the medal coin featured the Nazi swastika and other side featured the Star of David.

In 1940, Lehi

, a militant Zionist

group founded by Avraham ("Yair") Stern

, proposed intervening in World War II on the side of Nazi Germany. It offered assistance in transferring the Jews of Europe to Palestine, in return for Germany's help in expelling Britain from Mandatory Palestine. Late in 1940, Lehi representative Naftali Lubenchik went to Beirut

to meet German official Werner Otto von Hentig

(who also was involved with the Haavara or Transfer Agreement

, which had been transferring German Jews and their funds to Palestine since 1933). Lubenchik told von Hentig that Lehi had not yet revealed its full power and that they were capable of organizing a whole range of anti-British operations. This proposed alliance with Nazi Germany cost Lehi and Stern much support.

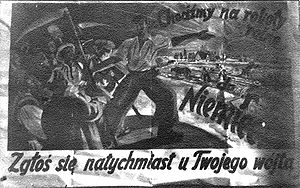

Unlike in most European countries occupied by Nazi Germany

Unlike in most European countries occupied by Nazi Germany

where the Germans sought and found true collaborators among the localsin occupied Poland there was no official collaboration either at the political or at the economic level. Poland also never officially surrendered to the Germans. Under German occupation, the Polish army continued to fight underground, as Armia Krajowa

and forest partisans – Leśni

. The Polish resistance movement in World War II

in German-occupied Poland was the largest resistance movement in all of occupied Europe. As a result, Polish citizens were unlikely to be given positions of any significant authority. The vast majority of the pre-war citizenry collaborating with the Nazis was the German minority in Poland

which was offered one of several possible grades of the German citizenship. In 1939, before the German invasion of Poland, 800,000 people declared themselves as members of the German minority in Poland mostly in Pomerania

and Western Silesia

. During the war there were about 3 million former Polish citizens of German origin who signed the official list of Volksdeutsche

. People who became Volksdeutsche were treated by Poles with special contempt, and the fact of them having signed the Volksliste

constituted high treason according to the Polish underground law.

There is a general consensus among historians that there was very little collaboration with the Nazis among the Polish nation as a whole, compared to other German-occupied countries. Depending on a definition of collaboration (and of a Polish citizen, based on ethnicity and minority status), scholars estimate number of "Polish collaborators" at around several thousand in a population of about 35 million (that number is supported by the Israeli War Crimes Commission). The estimate is based primarily on the number of death sentences for treason

by the Special Courts

of the Polish Underground State. Some estimates are higher, counting in all members of the German minority in Poland and any former Polish citizens declaring their German ethnicity (Volksdeutsche

), as well as conscripted members of the Blue Police

, low-ranking Polish bureaucrats employed in German occupational administration, and even workers in forced labor camps (ex. Zivilarbeiter

and Baudienst

). Most of the Blue Police

were forcibly drafted into service; nevertheless, a significant number acted as spies for Polish resistance movement Armia Krajowa

. John Connelly quoted a Polish historian (Leszek Gondek) calling the phenomenon of Polish collaboration "marginal" and wrote that "only relatively small percentage of Polish population engaged in activities that may be described as collaboration when seen against the backdrop of European and world history".

The anti-Jewish actions of szmalcownicy

were very harmful to the Polish Jews as well as the gentile Poles aiding them. Anti-Jewish collaboration of Poles was particularly widespread and effective in the rural areas. It is estimated that some 200 thousand hiding Jews died in 1942-1945 in direct result of this collaboration. The collaboration by some Polish Jews, who belonged to Żagiew

, was also harmful to both Jewish and ethnic Polish Underground.

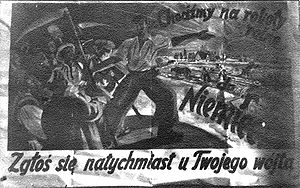

In October 1939, the Nazis ordered the mobilization

of the pre-war Polish police to the service of the occupational authorities. The policemen were to report for duty or face death penalty. Blue Police

was formed. At its peak in 1943, it numbered around 16,000. Its primary task was to act as a regular police

force and to deal with criminal activities, but were also used by the Germans in combating smuggling, resistance, and in measures against the Polish (and Polish Jewish) population: for example, it was present in łapankas (rounding up random civilians for labor duties) and patrolling for Jewish escapees from the ghetto

s. Nonetheless many individuals in the Blue Police followed German orders reluctantly, often disobeyed German orders or even risked death acting against them. Many members of the Blue Police were in fact double agent

s for the Polish resistance. Some of its officers were ultimately awarded the Righteous among the Nations

awards for saving Jews.

Following Nazi Germany's attack on the Soviet Union

in June 1941, German forces quickly overran the territory of Poland controlled by the Soviets since their joint invasion of Poland in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact

. A number of people collaborating with the Soviets before Operation Barbarossa

were killed by local people. Belief in the Żydokomuna

stereotype, combined with the German Nazi encouragement for expression of anti-Semitic attitudes, was a principal cause of massacres of Jews by gentile Poles in Poland's northeastern Łomża province in the summer of 1941, including the massacre at Jedwabne

.

In 1944 Germans clandestinely armed a few regional Armia Krajowa

(AK) units operating in the area of Vilnius

in order to encourage them to act against the Soviet partisans

in the region; in Nowogrodek district and to a lesser degree in Vilnius district (AK turned these weapons against the Nazis during Operation Ostra Brama). Such arrangements were purely tactical and did not evidence the type of ideological collaboration as shown by Vichy regime in France or Quisling regime

in Norway. The Poles main motivation was to gain intelligence on German morale and preparedness and to acquire much needed equipment. There are no known joint Polish-German actions, and the Germans were unsuccessful in their attempt to turn the Poles toward fighting exclusively against Soviet partisans. Further, most of such collaboration of local commanders with the Germans was condemned by AK headquarters. Tadeusz Piotrowski

quotes Joseph Rothschild

saying "The Polish Home Army was by and large untainted by collaboration" and adds that "the honor of AK as a whole is beyond reproach".

One partisan unit of Polish right-wing National Armed Forces, the Holy Cross Mountains Brigade

, decided to tacitly cooperate with the Germans in late 1944. It ceased hostile actions against the Germans for a few months, accepted logistic help and withdrew from Poland into Czechoslovakia with German approval (where they resumed hostilities against the Germans) in late stages of the war in order to avoid capture by the Soviets.

of Nazi Germany

. The Slovak Republic existed on roughly the same territory as present-day Slovakia

(with the exception of the southern and eastern parts of present-day Slovakia). The Republic bordered Germany, the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

, Poland

, and Hungary

.

and Vyacheslav Molotov

with its invasion of the Soviet Union at 3:15 am on June 22, 1941. Large areas of the European part of the Soviet Union

would be placed under German occupation between 1941 and 1944. Soviet collaborators included numerous Russians and members of other ethnic groups.

The Germans attempted to recruit Soviet citizens (and to a lesser extent other Eastern Europeans) voluntarily for the OST-Arbeiter

or Eastern worker program; originally this worked, but the news of the terrible conditions they faced dried up the volunteers and the program became forcible.

villagers. Many of these collaborators retreated with German forces in the wake of the Red Army

advance, and in January 1945, formed the 30th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Belarussian).

, Turkic and Caucasian forces deployed by the Nazis consisted primarily of Red Army POWs, assembled into ill-trained legions. Among these battalions were 18,000 Armenians, 13,000 Azerbaidjanis, 14,000 Georgians and 10,000 men from the "North Caucasus." American historian Alexander Dallin notes that Armenian Legion and Georgian battalions were sent to the Netherlands as a result of Hitler's distrust for them, many of which deserted

. According to military historian Christopher Ailsby, the Turkic and Caucasian forces formed by the Germans were "poorly armed, trained, and motivated," and were "unreliable and next to useless."

Armenian Revolutionary Federation (The Dashnaks) was conquered by the Russian Bolshevik

s in 1920, and ceased to exist. During World War II, some of the Dashnaks saw an opportunity in the collaboration with the Germans to regain those territories. The legion participated in the occupation of the Crimea

n Peninsula and the Caucasus

. On December 15, 1942, the Armenian National Council was granted official recognition by Alfred Rosenberg

, the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories

. The president of Council was Professor Ardasher Abeghian, its vice-president Abraham Guilkhandanian and it numbered among its members Garegin Nzhdeh and Vahan Papazian. Until the end of 1944 it published a weekly journal, Armenian, edited by Viken Shantn who also broadcast on Radio Berlin with the aid of Dr. Paul Rohrbach

.

proper, ethnic Russians were allowed to govern the Lokot Republic

, an autonomous sector in Nazi-occupied Russia. Military groups under Nazi command were formed, such as the notorious Kaminski Brigade, infamous because of its involvement in atrocities in Belarus and Poland, and the 30th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (2nd Russian)

.

Ethnic Russians also enlisted in large numbers into the many German auxiliary police units. Local civilians and Russian POWs, as well as Red Army

defectors were encouraged to join the Wehrmacht as "hilfswillige

". Some of them also served in so-called Ost battalions which, in particular, defended the French coastline against the expected Allied invasion.

The Kalmykian Voluntary Cavalry Corps

was a unit of about 5,000 Kalmyk

Mongol volunteers who chose to join the Wehrmacht in 1942 rather than remain in Kalmykia

as the German Army retreated before the Red Army

.

In May 1943, German General Helmuth von Pannwitz

was given authorization to create a Cossack

Division consisting of two brigades primarily from Don

and Kuban Cossacks

, including former exiled White Army commanders such as Pyotr Krasnov

and Andrei Shkuro

. The division however was then not sent to fight the Red Army, but was ordered, in September 1943, to proceed to Yugoslavia

and fight Josip Broz Tito

's partisans

. In the summer of 1944, the two brigades were upgraded to become the 1st Cossack Cavalry Division

and 2nd Cossack Cavalry Division. From the beginning of 1945, these divisions were combined to become XVth SS Cossack Cavalry Corps

.

Pro-German Russian forces also included the anti-communist Russian Liberation Army

(ROA), which saw action as a part of the Wehrmacht

. On May 1, 1945, however, ROA turned against the SS and fought on the side of Czech insurgents

during the Prague Uprising

.

was divided primarily between the Ukrainian SSR

of the Soviet Union

and the Second Polish Republic

. Smaller regions were administered by Romania

and Czechoslovakia

. Only the Soviet Union recognised Ukrainian autonomy, and large numbers of Ukrainians, particularly from the East, fought in the Red Army

.

The negative impact of Soviet policies implemented in the 1930s were still fresh in the memory of Ukrainians. These included the Holodomor

of 1933, the Great Terror, the persecution of intellectuals during the Great Purge

of 1937-38, the massacre of Ukrainian intellectuals after the annexation of Western Ukraine

from Poland in 1939, the introduction and implementation of Collectivisation.

As a result, the population of whole towns, cities and villages, greeted the Germans as liberators which helps explain the unprecedented rapid progress of the German forces in the occupation of Ukraine.

Even before the German invasion, the Nachtigall

and Roland

battalions were set up and trained as Ukrainian battalions in the Wehrmacht, and were part of the initial invading force.

With the change in regime ethnic, Ukrainians were allowed and encouraged to work in administrative positions. These included and the auxiliary police, post office, and other government structures; taking the place of Poles, Russians and Jews.

Soviet citizens had a page in their internal passport

s with information regarding their ethnicity, party status, military rank, service in the Soviet Army reserve, and information as to where they were to assemble in case of war. This document also contained markings regarding a citizens social status and reliability, (i.e. son of a kulak

, party or Komsomol

membership. Soviet POWs who were able to demonstrate Soviet unreliability i.e. non membership in the CPSU

, Komsomol or be of a discriminated class were quickly released from the POW camps. Often they were offered administrative and clerical positions or encouraged to join local police units. Some were trained as camp guards, while others were encouraged (in some cases forced) to enlist to fight in anti-Soviet military divisions.

During the period of occupation, Nazi-controlled Ukrainian newspaper Volhyn wrote that "The element that settled our cities (Jews)... must disappear completely from our cities. The Jewish problem is already in the process of being solved.

There is evidence of some Ukrainian participation in the Holocaust. The auxiliary police in Kiev participated in rounding up of Jews who were directed to the Babi Yar

massacre.

Ukrainians participated in crushing the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

of 1943 and the Warsaw Uprising

of 1944 where a mixed force of German SS troops, Russians, Cossacks, Azeris and Ukrainians, backed by German regular army units — killed up to 40,000 civilians.

In Zhytomyr

on September 18, 1941, 3,145 Jews were murdered with the assistance of Ukrainian militia (Operational Report 106) and Korosten

where Ukrainian militia rounded up 238 Jews for liquidation (Operational Report 80). At times the assistance was more active. Operational Report 88, for example, reports that on September 6, 1941, 1,107 Jewish adults were shot while the Ukrainian militia unit assisting them liquidated 561 Jewish children and youths.

On April 28, 1943 German Command anounced the estblishment of the SS-Freiwilligen-Schützen-Division «Galizien». It has been accounted that approximately 83,000 people volunteered for service in the Division. The Division, was used in Anti-partisan operations in Poland

, Czechoslovakia

and Yugoslavia

. During the Brody offensive and Vienna Offensive

to fight the Soviet forces. Those that survived surrendered to the Allies and the bulk emigrated to the West, primarily England, Australia and Canada.

, the Yugoslav government was working on forging a pact with Germany. That pact was rejected by Yugoslav antifascists, who guided by general Dušan Simović

demonstrated on March 26, 1941, and forced the government to withdraw. Angered by what he perceived as treason, Hitler invaded Kingdom of Yugoslavia

without warning on April 6, 1941. Eleven days later Yugoslavia capitulated.

and Croats

, but commanded by German officers, was created in February 1943. The division participated in anti-guerrilla operations in Yugoslavia. The division operated until 1945 with considerable strength, although by that time many tried to leave Bosnia along with the SS Prinz Eugen, Ustase, Serbian Volunteer Corps, Serbian State Guard, and Chetniks. They were massacred at Bleiburg all together.

's Croatian puppet state was an ally of Nazi Germany. The Croatian extreme nationalists, Ustaše

, killed 700 thousands of Serbs and other victims in the Jasenovac concentration camp

.

The 13th Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Handschar (1st Croatian), created in February 1943, and the 23rd Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Kama

, created in January 1944, were manned by Croats and Bosniaks as well as local Germans.

(party militia of the extreme right-wing Yugoslav National Movement "Zbor"

had a few thousand members and helped guard and run concentration camps.

created 21st Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Skanderbeg (1st Albanian)

manned by Albanian

and Kosovar Albanian volunteers. By June 1944, the military value was deemed low in lieu of partisan aggression and by November 1944 it was disbanded. The remaining cadre, now called Kampfgruppe Skanderbeg, was transferred to the Prinz Eugen Division where they successfully participated in actions against Tito's partisans in December 1944. The emblem of the division was a black Albanian eagle. Balli Kombëtar

was an Albanian

nationalist and anti-communist organization which collaborated with the Axis Powers

during their occupation of Greece and Yugoslavia

. Their agenda was the creation of "Great Albania."

(then a part of Yugoslavia

). An individual member was a Domobranec, the plural of which was Domobranci. The SD functioned like most collaborationist forces in Axis-occupied Europe during World War II, but had limited autonomy, and at first functioned as an auxiliary police force that assisted the Germans in anti-Partisan

actions. Later, it gained more autonomy and conducted most of the anti-partisan operations in the Province of Ljubljana

. Much of the SD equipment was Italian

(confiscated when Italy dropped out of the war in 1943), although German weapons and equipment were used as well, especially later in the war. Similar, but much smaller units were also formed in Littoral

(Primorska) and Upper Carniola

(Gorenjska).

were the only British territory

in Europe occupied by Nazi Germany during World War II. The policy of the Island governments, acting under instructions from the British government communicated before the occupation, was one of passive co-operation, although this has been criticised, particularly in the treatment of Jews in the islands. These measures were administered by the Bailiff and the Aliens Office. "In Britain the administrators and the police in the Channel Islands who had helped with the deportation of Jews continued to work in their old positions, and some of them even received the Order of the British Empire

for the bravery they had shown in the war years."

Following the liberation of 1945 allegations against those accused of collaborating with the occupying authorities were investigated. By November 1946, the UK Home Secretary was in a position to inform the UK House of Commons that most of the allegations lacked substance and only 12 cases of collaboration were considered for prosecution, but the Director of Public Prosecutions

had ruled out prosecutions on insufficient grounds. In particular, it was decided that there were no legal grounds for proceeding against those alleged to have informed to the occupying authorities against their fellow-citizens.

In Jersey

and Guernsey

, laws were passed to retrospectively confiscate the financial gains made by war profiteers and black marketeers, although these measures also affected those who had made legitimate profits during the years of military occupation.

During the occupation, cases of women fraternising with German soldiers had aroused indignation among some citizens. In the hours following the liberation, members of the British liberating forces were obliged to intervene to prevent revenge attacks.

countries (British Free Corps

). Overall, almost 600,000 of Waffen-SS members were non-German http://www.scrapbookpages.com/DachauScrapbook/DachauLiberation/BuechnerAccount.html with some countries as Belgium and the Netherlands contributing thousands of volunteers.

Various collaborationalist parties in occupied France

and the Vichy

government assisted in establishing the Légion des volontaires français contre le bolchevisme (LVF)

. This volunteer army initially counted some 10,000 volunteers and would later become the 33rd Waffen SS division and one of the first SS divisions comprising mostly foreigners.

Following is a list of the 18 largest Waffen SS division composed mostly or totally of foreign volunteers (note that there were other foreign Waffen SS divisions composed mostly of forced conscripts).

Apart from frontline units volunteers played another important role notably in the large Schutzmannschaft units in the German occupied territories in Eastern Europe. After Operation Barbarossa

recruitment of local forces began almost immediately mostly by initiative of Himmler. These forces were not members of the regular armed forces and were not intended for frontline duty but were instead used for rear echelon activities including maintaining peace, fighting partisans

, acting as police and organizing supplies for the front lines. In the later years of the war, these units numbered almost 200,000.

By the end of World War II, 60% of the Waffen SS was made up of non-German volunteers from occupied countries. The predominantly Scandinavian 11th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division Nordland division along with remnants of French

, Italian

, Spanish

and Dutch

volunteers were last defenders of the Reichstag

in Berlin

.

The Nuremberg Trials

, in declaring the Waffen SS a criminal organisation, explicitly excluded conscripts, who had committed no crimes. In 1950, The U.S. High Commission in Germany and the U.S. Displaced Persons Commission clarified the U.S. position on the Baltic Waffen SS Units, considering them distinct from the German SS in purpose, ideology, activities and qualifications for membership.

of the Balkans

. Albania

, having an Italian puppet state, declared war on the Allies along with the Kingdom of Italy

in 1940, although the resistance movements and the peoples were against this. Later that year Slovakia

declared war on Great Britain

and the United States

. Slovakian, Croatian and Albanian collaborators fought with the German forces against the Soviet Union

on the eastern front throughout the war. Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and Soviet invasion of Poland

in 1939 should also be mentioned.

However, significant support was also given by many countries initially at war with Germany but which subsequently elected to adopt a policy of co-operation.

The Vichy

government in France is one of the best known and most significant examples of collaboration between former enemies of Germany and Germany itself. When the French Vichy government emerged at the same time of the Free French in London

there was much confusion regarding the loyalty of French overseas colonies and more importantly their overseas armies and naval fleet. The reluctance of Vichy France to either disarm or surrender their naval fleet resulted in the British destruction of the French Fleet at Mers-el-Kebir

on 3 July 1940. Later in the war French colonies were frequently used as staging areas for invasions or airbases for the Axis powers both in Indo China and Syria

. This resulted in the invasion of Syria and Lebanon

with the capture of Damascus

on June 17 and later the Battle of Madagascar

against Vichy French forces which lasted for seven months until November the same year.

Many other countries cooperated to some extent and in different ways. Denmark's government cooperated with the German occupiers until 1943 and actively helped recruit members for the Nordland and Wiking Waffen SS divisions and helped organize trade and sale of industrial and agricultural products to Germany. In Greece, the three quisling prime ministers (Georgios Tsolakoglou

, Konstantinos Logothetopoulos

and Ioannis Rallis

) cooperated with the Axis authorities. Agricultural products (especially tobacco) were sent to Germany, Greek "volunteers" were sent to work to German factories, and special armed forces (such as the Security Battalions

were created to fight along German soldiers against the Allies and the Resistance movement. In Norway the government successfully managed to escape to London

but Vidkun Quisling

established a puppet regime in its absence—albeit with little support from the local population.

Axis Powers

The Axis powers , also known as the Axis alliance, Axis nations, Axis countries, or just the Axis, was an alignment of great powers during the mid-20th century that fought World War II against the Allies. It began in 1936 with treaties of friendship between Germany and Italy and between Germany and...

, some citizens, driven by nationalism

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

, ethnic hatred

Ethnic hatred

Ethnic hatred, inter-ethnic hatred, racial hatred, or ethnic tension refers to feelings and acts of prejudice and hostility towards an ethnic group in various degrees. See list of anti-ethnic and anti-national terms for specific cases....

, anti-communism

Anti-communism

Anti-communism is opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed in reaction to the rise of communism, especially after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia and the beginning of the Cold War in 1947.-Objections to communist theory:...

, anti-Semitism

Anti-Semitism

Antisemitism is suspicion of, hatred toward, or discrimination against Jews for reasons connected to their Jewish heritage. According to a 2005 U.S...

or opportunism

Opportunism

-General definition:Opportunism is the conscious policy and practice of taking selfish advantage of circumstances, with little regard for principles. Opportunist actions are expedient actions guided primarily by self-interested motives. The term can be applied to individuals, groups,...

, knowingly engaged in collaboration with the Axis Powers during World War II. Some of these collaborationists committed the worst crimes and atrocities of the Holocaust.

Collaboration ranged from urging the civilian population to remain calm and accept foreign occupation without conflict, organizing trade, production, financial and economic support to joining various branches of the armed forces of the Axis powers

Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also the Three-Power Pact, Axis Pact, Three-way Pact or Tripartite Treaty was a pact signed in Berlin, Germany on September 27, 1940, which established the Axis Powers of World War II...

or special "national" military units fighting under their command.

Requirements for collaboration

The Nazis did not consider everyone equally fit for cooperation. Even people from closely related nations were often valued differently in accordance with Nazi racial theoriesRacial policy of Nazi Germany

The racial policy of Nazi Germany was a set of policies and laws implemented by Nazi Germany, asserting the superiority of the "Aryan race", and based on a specific racist doctrine which claimed scientific legitimacy...

.

The Jews were considered to be worst of all nations and thus unfit for cooperation, although some were used in concentration camps as Kapos

Kapo (concentration camp)

A kapo was a prisoner who worked inside German Nazi concentration camps during World War II in any of certain lower administrative positions. The official Nazi word was Funktionshäftling, or "prisoner functionary", but the Nazis commonly referred to them as kapos.- Etymology :The origin of "kapo"...

to report on other prisoners and enforce order. Others governed ghettos and helped organize deportation

Deportation

Deportation means the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. Today it often refers to the expulsion of foreign nationals whereas the expulsion of nationals is called banishment, exile, or penal transportation...

s to extermination camps (Jewish Ghetto Police

Jewish Ghetto Police

Jewish Ghetto Police , also known as the Jewish Police Service and referred to by the Jews as the Jewish Police, were the auxiliary police units organized in the Jewish ghettos of Europe by local Judenrat councils under orders of occupying German Nazis.Members of the did not have official...

).

Albania

In April 1943, Reichsfuhrer-SS Heinrich HimmlerHeinrich Himmler

Heinrich Luitpold Himmler was Reichsführer of the SS, a military commander, and a leading member of the Nazi Party. As Chief of the German Police and the Minister of the Interior from 1943, Himmler oversaw all internal and external police and security forces, including the Gestapo...

created the 21st Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Skanderbeg (1st Albanian)

21st Waffen Mountain Division of the SS Skanderbeg (1st Albanian)

The 21st Division of the SS Skanderbeg was a Mountain division of the SS set up by Heinrich Himmler in March 1944, officially under the title of the 21. Waffen-Gebirgs Division der SS Skanderbeg...

manned by Albanian

Albanians

Albanians are a nation and ethnic group native to Albania and neighbouring countries. They speak the Albanian language. More than half of all Albanians live in Albania and Kosovo...

and Kosovar Albanian volunteers . By June 1944, the military value was deemed low in lieu of partisan aggression and by November 1944 it was disbanded. The remaining cadre, now called Kampfgruppe Skanderbeg, was transferred to the Prinz Eugen Division where they successfully participated in actions against Tito's partisans in December 1944. The emblem of the division was a black Albanian eagle.

Belgium

The 373rd infantryInfantry

Infantrymen are soldiers who are specifically trained for the role of fighting on foot to engage the enemy face to face and have historically borne the brunt of the casualties of combat in wars. As the oldest branch of combat arms, they are the backbone of armies...

battalion

Battalion

A battalion is a military unit of around 300–1,200 soldiers usually consisting of between two and seven companies and typically commanded by either a Lieutenant Colonel or a Colonel...

of Wehrmacht

Wehrmacht

The Wehrmacht – from , to defend and , the might/power) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the Heer , the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe .-Origin and use of the term:...

, manned by Walloon Belgians, took part in anti-guerrilla actions in the occupied territory of the USSR from August 1941-February 1942. In May 1943, the battalion was transformed into the 5th SS Volunteer Sturmbrigade Wallonien and sent to the Eastern Front

Eastern Front (World War II)

The Eastern Front of World War II was a theatre of World War II between the European Axis powers and co-belligerent Finland against the Soviet Union, Poland, and some other Allies which encompassed Northern, Southern and Eastern Europe from 22 June 1941 to 9 May 1945...

. In the autumn, the brigade had been transformed into 28th SS Volunteer Grenadier Division Wallonien. Its remnants surrendered to British troops in the final days of war. Flemish Belgian collaborators were organized first into the 6th SS Volunteer Brigade

6th SS Volunteer Sturmbrigade Langemarck

The 27th SS Volunteer Division Langemarck was a German Waffen-SS volunteer division comprising volunteers of Flemish background. It saw action on the Eastern Front during World War II....

and later the 27th SS Infantry (Grenadier) Division. Belgians served in the German forces from mid-1941 until the end of the war.

China

The Japanese set up several puppet regimes in occupied Chinese territories. The first of which was ManchukuoManchukuo

Manchukuo or Manshū-koku was a puppet state in Manchuria and eastern Inner Mongolia, governed under a form of constitutional monarchy. The region was the historical homeland of the Manchus, who founded the Qing Empire in China...

in 1932, followed by the East Hebei Autonomous Council

East Hebei Autonomous Council

The East Hebei Autonomous Council also known as the East Ji Autonomous Council and the East Hopei Autonomous Anti-Communist Council, was a short-lived Japanese puppet state in northern China in the late 1930s.-History:...

in 1935. Similar to Manchukuo

Manchukuo

Manchukuo or Manshū-koku was a puppet state in Manchuria and eastern Inner Mongolia, governed under a form of constitutional monarchy. The region was the historical homeland of the Manchus, who founded the Qing Empire in China...

in its supposed ethnic identity, Mengjiang

Mengjiang

Mengjiang , also known in English as Mongol Border Land, was an autonomous area in Inner Mongolia, operating under nominal Chinese sovereignty and Japanese control. It consisted of the then-Chinese provinces of Chahar and Suiyuan, corresponding to the central part of modern Inner Mongolia...

(Mengkukuo) was set up in late 1936. Wang Kemin

Wang Kemin

Wang Kemin was a leading official in the Chinese republican movement and early Beiyang government, later noted for his role as in the collaborationist Provisional Government of the Republic of China and Nanjing Nationalist Government during World War II....

's collaborationist Provisional Government of the Republic of China was set up in Beiping in 1937 following the start of full-scale military operations between China and Japan

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was a military conflict fought primarily between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. From 1937 to 1941, China fought Japan with some economic help from Germany , the Soviet Union and the United States...

, another puppet regime was the Reformed Government of the Republic of China, setup in Nanjing

Nanjing

' is the capital of Jiangsu province in China and has a prominent place in Chinese history and culture, having been the capital of China on several occasions...

in 1938. The Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei

Wang Jingwei , alternate name Wang Zhaoming, was a Chinese politician. He was initially known as a member of the left wing of the Kuomintang , but later became increasingly anti-Communist after his efforts to collaborate with the CCP ended in political failure...

collaborationist government, established in 1940, "consolidated" these regimes, though in reality neither Wang's government nor the constituent governments had any autonomy, although the military of the Wang Jingwei Government

Wang Jingwei Government

In March 1940 a puppet government led by Wang Jingwei was established in the Republic of China under the protection of the Empire of Japan. The regime officially called itself the Republic of China and its government the Reorganized National Government of China...

was equipped by the Japanese with planes, cannons, tanks, boats, and German-style stahlhelm

Stahlhelm

Stahlhelm is German for "steel helmet". The Imperial German Army began to replace the traditional boiled-leather Pickelhaube with the Stahlhelm during World War I in 1916...

(already widely used by the National Revolutionary Army

National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army , pre-1928 sometimes shortened to 革命軍 or Revolutionary Army and between 1928-1947 as 國軍 or National Army was the Military Arm of the Kuomintang from 1925 until 1947, as well as the national army of the Republic of China during the KMT's period of party rule...

, the "official" army of the Republic of China

Republic of China (1912–1949)

In 1911, after over two thousand years of imperial rule, a republic was established in China and the monarchy overthrown by a group of revolutionaries. The Qing Dynasty, having just experienced a century of instability, suffered from both internal rebellion and foreign imperialism...

).

The military forces of these puppet regimes, known collectively as the Collaborationist Chinese Army

Collaborationist Chinese Army

The Collaborationist Chinese Army in the Second Sino-Japanese War went under different names at different times depending on which collaborationist leader or puppet regime it was organized under....

, numbered more than a million at their height, with some estimates that the number exceeded 2 million conscripts. Great number of collaborationist troops were men originally serving in warlord forces within the National Revolutionary Army who had defected when facing both Communists and Japanese as enemies. Although its manpower was very large, the soldiers were very ineffective compared to NRA soldiers due to low morale for being considered as "Hanjian

Hanjian

In Chinese culture, a Hanjian is a derogatory and pejorative term for a race traitor to the Han Chinese nation or state, and to a lesser extent, Han ethnicity. The word Hanjian is distinct from the general word for traitor, which could be used for any race or country...

". Although certain collaborationist forces had limited battlefield presence during the Second Sino-Japanese War

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was a military conflict fought primarily between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. From 1937 to 1941, China fought Japan with some economic help from Germany , the Soviet Union and the United States...

, most were relegated to behind-the-line duties.

The Wang Jingwei government was disbanded after Japanese surrender to Allies in 1945, and Manchukuo and Mengjiang were destroyed by Soviet troops in the invasion of Manchuria.

Denmark

At 04:15 on 9 April 1940 (Danish standard time), German forces crossed the border into neutralNeutral country

A neutral power in a particular war is a sovereign state which declares itself to be neutral towards the belligerents. A non-belligerent state does not need to be neutral. The rights and duties of a neutral power are defined in Sections 5 and 13 of the Hague Convention of 1907...

Denmark, in direct violation of a German-Danish treaty of non-aggression signed the previous year. After two hours the Danish government surrendered

Surrender (military)

Surrender is when soldiers, nations or other combatants stop fighting and eventually become prisoners of war, either as individuals or when ordered to by their officers. A white flag is a common symbol of surrender, as is the gesture of raising one's hands empty and open above one's head.When the...

, believing that resistance was useless and hoping to work out an advantageous agreement with Germany.

As a result of the cooperative attitude of the Danish authorities, German officials claimed that they would "respect Danish sovereignty and territorial integrity, as well as neutrality." The German authorities were inclined towards lenient terms with Denmark for several reasons. These factors allowed Denmark a very favorable relationship with Nazi Germany. The government remained intact and the parliament

Parliament

A parliament is a legislature, especially in those countries whose system of government is based on the Westminster system modeled after that of the United Kingdom. The name is derived from the French , the action of parler : a parlement is a discussion. The term came to mean a meeting at which...

continued to function more or less as it had before. They were able to maintain much of their former control over domestic policy. Danish public opinion generally backed the new government, particularly after the fall of France in June 1940. There was a general feeling that the unpleasant reality of German occupation must be confronted in the most realistic way possible, given the international situation. Newspaper articles and news reports "which might jeopardize German-Danish relations" were outlawed. After the assault on the Soviet Union, Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the code name for Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II that began on 22 June 1941. Over 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invaded the USSR along a front., the largest invasion in the history of warfare...

, Denmark joined the Anti-Comintern Pact

Anti-Comintern Pact

The Anti-Comintern Pact was an Anti-Communist pact concluded between Nazi Germany and the Empire of Japan on November 25, 1936 and was directed against the Communist International ....

, together with the fellow Nordic

Nordic countries

The Nordic countries make up a region in Northern Europe and the North Atlantic which consists of Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden and their associated territories, the Faroe Islands, Greenland and Åland...

state of Finland

Finland

Finland , officially the Republic of Finland, is a Nordic country situated in the Fennoscandian region of Northern Europe. It is bordered by Sweden in the west, Norway in the north and Russia in the east, while Estonia lies to its south across the Gulf of Finland.Around 5.4 million people reside...

; the Communist Party

Communist party

A political party described as a Communist party includes those that advocate the application of the social principles of communism through a communist form of government...

was banned in Denmark. Industrial production

Industry

Industry refers to the production of an economic good or service within an economy.-Industrial sectors:There are four key industrial economic sectors: the primary sector, largely raw material extraction industries such as mining and farming; the secondary sector, involving refining, construction,...

and trade was, partly due to geopolitical reality and economic necessity, redirected toward Germany. Many government officials saw expanded trade with Germany as vital to maintaining social order in Denmark. Increased unemployment

Unemployment

Unemployment , as defined by the International Labour Organization, occurs when people are without jobs and they have actively sought work within the past four weeks...

and poverty was feared to lead to more of open revolt within the country, since Danes tended to blame all negative developments on the Germans. It was feared that any revolt would result in a crackdown by the German authorities.

In return for these concessions, the Danish cabinet rejected German demands for legislation discriminating against Denmark's Jewish minority. Demands to introduce the death penalty were likewise rebuffed and so were German demands to allow German military courts jurisdiction over Danish citizens. Denmark also rejected demands for the transfer of Danish army units to German military use. Throughout the years of its hold on power, the government consistently refused to accept German demands regarding the Jews. The authorities would not enact special laws concerning Jews, and their civil rights remained equal with those of the rest of the population. German authorities became increasingly exasperated with this position but concluded that any attempt to remove or mistreat Jews would be "politically unacceptable." Even the Gestapo

Gestapo

The Gestapo was the official secret police of Nazi Germany. Beginning on 20 April 1934, it was under the administration of the SS leader Heinrich Himmler in his position as Chief of German Police...

officer Dr. Werner Best

Werner Best

Dr. Werner Best was a German Nazi, jurist, police chief, SS-Obergruppenführer and Nazi Party leader from Darmstadt, Hesse. He studied law and in 1927 obtained his doctorate degree at Heidelberg...

, plenipotentiary in Denmark from November 1942, believed that any attempt to remove the Jews would be enormously disruptive to the relationship between the two governments and recommended against any action concerning the Jews of Denmark.

On 29 June 1941, days after the invasion of the USSR

Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the code name for Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union during World War II that began on 22 June 1941. Over 4.5 million troops of the Axis powers invaded the USSR along a front., the largest invasion in the history of warfare...

, Frikorps Danmark

Frikorps Danmark

Free Corps Denmark was a Danish volunteer free corps created by the Danish Nazi Party in cooperation with Germany, to fight the Soviet Union during the Second World War. On June 29, 1941, days after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, the DNSAP's newspaper Fædrelandet proclaimed the creation...

(Free Corps Denmark) was founded as a corps of Danish volunteers to fight against the Soviet Union. Frikorps Danmark was set up at the initiative of the SS and DNSAP who approached Lieutenant-Colonel C.P. Kryssing of the Danish army shortly after the invasion of the USSR had begun. The Nazi paper Fædrelandet proclaimed the creation of the corps on 29 June 1941. According to Danish law, it was not illegal to join a foreign army, but active recruiting on Danish soil was illegal. The SS disregarded this law and began recruiting efforts — predominantly recruiting Danish Nazis and members of the German-speaking minority.

Estonia

Although the Estonian Self-AdministrationEstonian Self-Administration

Estonian Self-Administration , also known as the Directorate, was the puppet government set up in Estonia during occupation of Estonia by Nazi Germany...

did not have complete freedom of action, it exercised a significant measure of autonomy, within the framework of German policy, political, racial and economic. Thus, the Directors exercised their powers pursuant to the laws and regulations of the Republic of Estonia, but only to the extent that these had not been repealed or amended by the German military command. The Director's position was voluntary. The Self-Administration’s autonomy enabled it to maintain police structures that

cooperated with the Germans in rounding up and

killing Jews and Roma, and in seeking out

and killing Estonians deemed to be opponents of the

occupiers, and which were ultimately incorporated

into the Estonian Security Police and SD

Estonian Security Police and SD

The Estonian Security Police and SD , or Sipo, was a security police force created by the Germans in 1942 that integrated both Germans and Estonians within a unique structure mirroring the German Sicherheitspolizei....

. It also extended to the

unlawful conscription

Conscription

Conscription is the compulsory enlistment of people in some sort of national service, most often military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and continues in some countries to the present day under various names...

of Estonians for forced labor

or for military service

Military service

Military service, in its simplest sense, is service by an individual or group in an army or other militia, whether as a chosen job or as a result of an involuntary draft . Some nations require a specific amount of military service from every citizen...

under German command.

The Estonian Security Police and SD, the 286th, 287th and 288th Estonian Auxiliary Police

Estonian Auxiliary Police

Estonian Auxiliary Police were Estonian units that fought in World War II under command of Germany. Estonian regular units allied with Nazi Germany began to be established on 25 August 1941, when under the order of Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb, commander of the Army Group North,...

Battalions, and 2.5–3% of Estonian Omakaitse

Omakaitse

The Omakaitse was a militia organisation in Estonia. It was founded in 1917 following the Russian Revolution. On the eve of the Occupation of Estonia by the German Empire the Omakaitse units took over major towns in the country allowing the Salvation Committee of the Estonian Provincial Assembly...

(Home Guard) militia

Militia

The term militia is commonly used today to refer to a military force composed of ordinary citizens to provide defense, emergency law enforcement, or paramilitary service, in times of emergency without being paid a regular salary or committed to a fixed term of service. It is a polyseme with...

units (approximately between 1000 and 1200 men) were directly involved in criminal acts, taking part in the round-up, guarding or killing of 400–1000 Roma people and 6000 Jews in the concentration camps of Pskov region in Russia and the Jägala

Jägala

Jägala is a village in Jõelähtme Parish, Harju County, Estonia. It had 139 inhabitants in 2007.-See also:*Jägala River*Jägala Waterfall*Jägala concentration camp*Jägala Army Base*Jägala Airfield-External links:* *...

, Vaivara, Klooga

Klooga concentration camp

Klooga was a Nazi labor subcamp of the Vaivara concentration camp complex established in September 1943 in Harju County, during World War II, in German-occupied Estonia near the northern Estonian village Klooga...

, and Lagedi

Lagedi

Lagedi is a small borough in Rae Parish, Harju County, northern Estonia. It has a population of 847 .-External links:*...

camps in Estonia. Guarded by the above listed formations, 15,000 Soviet POW died in Estonia, part of them because of neglect and mistreatment and part executed.

France

Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Joseph Pétain , generally known as Philippe Pétain or Marshal Pétain , was a French general who reached the distinction of Marshal of France, and was later Chief of State of Vichy France , from 1940 to 1944...

and Pierre Laval

Pierre Laval

Pierre Laval was a French politician. He was four times President of the council of ministers of the Third Republic, twice consecutively. Following France's Armistice with Germany in 1940, he served twice in the Vichy Regime as head of government, signing orders permitting the deportation of...

, actively collaborated in the extermination of the European Jews. It also participated in Porrajmos, the extermination of Rom people, and in the extermination of other "undesirables." Vichy opened up a series of concentration camps in France where it interned Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, political opponents, etc. Directed by René Bousquet

René Bousquet

René Bousquet was a high-ranking French civil servant, who served as secretary general to the Vichy regime police from May 1942 to 31 December 1943.-Biography:...

, the French police helped in the deportation of 76,000 Jews to the extermination camps. In 1995, President Jacques Chirac

Jacques Chirac

Jacques René Chirac is a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. He previously served as Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and from 1986 to 1988 , and as Mayor of Paris from 1977 to 1995.After completing his studies of the DEA's degree at the...

officially recognized the responsibility of the French state for the deportation of Jews during the war, in particular the more than 13,000 victims the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup of July 1942, during which Laval decided, by his own, to deport children along with their parents. Only 2,500 of the deported Jews survived the war. The 1943 Battle of Marseille

Battle of Marseille

The Marseille´s Roundup took place in the Old Port of Marseille, under the Vichy regime, on 22, 23 and 24 January 1943. Assisted by the French police, which was directed by René Bousquet, the Nazis organized a raid to arrest Jewish people...

was another event during which the French police assisted the Gestapo in a massive raid, which included an urban reshaping plan involving the destruction of a whole neighbourhood in the popular Old Port. Some few collaborators were tried in the 1980s for crimes against humanity (Paul Touvier

Paul Touvier

Paul Touvier was a French Nazi collaborator. In 1994, he was the first Frenchman convicted of crimes against humanity for his actions in Vichy France.- Early life :...

, etc.), while Maurice Papon

Maurice Papon

Maurice Papon was a French civil servant, industrial leader and Gaullist politician, who was convicted for crimes against humanity for his participation in the deportation of over 1600 Jews during World War II when he was secretary general for police of the Prefecture of Bordeaux.Papon also...