Unification of Germany

Encyclopedia

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

into a politically and administratively integrated nation state officially occurred on 18 January 1871 at the Versailles Palace

Palace of Versailles

The Palace of Versailles , or simply Versailles, is a royal château in Versailles in the Île-de-France region of France. In French it is the Château de Versailles....

's Hall of Mirrors

Hall of Mirrors (Palace of Versailles)

The Hall of Mirrors is the central gallery of the Palace of Versailles and is renowned as being one of the most famous rooms in the world.As the principal and most remarkable feature of King Louis XIV of France's third building campaign of the Palace of Versailles , construction of the Hall of...

in France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

. Princes of the German states gathered there to proclaim Wilhelm of Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

as Emperor Wilhelm of the German Empire

German Empire

The German Empire refers to Germany during the "Second Reich" period from the unification of Germany and proclamation of Wilhelm I as German Emperor on 18 January 1871, to 1918, when it became a federal republic after defeat in World War I and the abdication of the Emperor, Wilhelm II.The German...

after the French capitulation in the Franco-Prussian War

Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the 1870 War was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia. Prussia was aided by the North German Confederation, of which it was a member, and the South German states of Baden, Württemberg and...

. Unofficially, the transition of most of the German-speaking populations into a federated organization of states occurred over nearly a century of experimentation. Unification exposed several glaring religious, linguistic, social, and cultural differences between and among the inhabitants of the new nation, suggesting that 1871 only represents one moment in a continuum of the larger unification processes.

The Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

, which had included more than 300 independent states, was effectively dissolved when Emperor Francis II

Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor

Francis II was the last Holy Roman Emperor, ruling from 1792 until 6 August 1806, when he dissolved the Empire after the disastrous defeat of the Third Coalition by Napoleon at the Battle of Austerlitz...

abdicated (6 August 1806) during the War of the Third Coalition. Despite the legal, administrative, and political disruption associated with the end of the Empire, the people of the German-speaking areas of the old Empire had a common linguistic, cultural and legal tradition further enhanced by their shared experience in the French Revolutionary Wars

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars were a series of major conflicts, from 1792 until 1802, fought between the French Revolutionary government and several European states...

and Napoleonic Wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

. European liberalism offered an intellectual basis for unification by challenging dynastic and absolutist

Absolutism (European history)

Absolutism or The Age of Absolutism is a historiographical term used to describe a form of monarchical power that is unrestrained by all other institutions, such as churches, legislatures, or social elites...

models of social and political organization; its German manifestation emphasized the importance of tradition, education, and linguistic unity of peoples in a geographic region. Economically, the creation of the Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

n Zollverein

Zollverein

thumb|upright=1.2|The German Zollverein 1834–1919blue = Prussia in 1834 grey= Included region until 1866yellow= Excluded after 1866red = Borders of the German Union of 1828 pink= Relevant others until 1834...

(customs union) in 1818, and its subsequent expansion to include other states of the German Confederation

German Confederation

The German Confederation was the loose association of Central European states created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to coordinate the economies of separate German-speaking countries. It acted as a buffer between the powerful states of Austria and Prussia...

, reduced competition between and within states. Emerging modes of transportation facilitated business and recreational travel, leading to contact and sometimes conflict between and among German-speakers from throughout Central Europe.

The model of diplomatic spheres of influence resulting from the Congress of Vienna

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna was a conference of ambassadors of European states chaired by Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, and held in Vienna from September, 1814 to June, 1815. The objective of the Congress was to settle the many issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars,...

in 1814–15 after the Napoleonic Wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

endorsed Austrian

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

dominance in Central Europe. However, the negotiators at Vienna took no account of Prussia's growing strength within and among the German states, failing to foresee that Prussia would challenge Austria for leadership within the German states. This German dualism

German dualism

Austria and Prussia had a long running conflict and rivalry for supremacy in Central Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries, called in Germany. While wars were a part of the rivalry, it was also a race for prestige to be seen as the legitimate political force of the German-speaking peoples...

presented two solutions to the problem of unification: Kleindeutsche Lösung, the small Germany solution (Germany without Austria), or Großdeutsche Lösung

German question

The German question was a debate in the 19th century, especially during the Revolutions of 1848, over the best way to achieve the Unification of Germany. From 1815–1871, a number of 37 independent German-speaking states existed within the German Confederation...

, greater Germany solution (Germany with Austria).

Historians debate whether or not Otto von Bismarck

Otto von Bismarck

Otto Eduard Leopold, Prince of Bismarck, Duke of Lauenburg , simply known as Otto von Bismarck, was a Prussian-German statesman whose actions unified Germany, made it a major player in world affairs, and created a balance of power that kept Europe at peace after 1871.As Minister President of...

, the Minister President of Prussia, had a master plan to expand the North German Confederation

North German Confederation

The North German Confederation 1866–71, was a federation of 22 independent states of northern Germany. It was formed by a constitution accepted by the member states in 1867 and controlled military and foreign policy. It included the new Reichstag, a parliament elected by universal manhood...

of 1866 to include the remaining independent German states into a single entity, or whether he simply sought to expand the power

Power in international relations

Power in international relations is defined in several different ways. Political scientists, historians, and practitioners of international relations have used the following concepts of political power:...

of the Kingdom of Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

. They conclude that factors in addition to the strength of Bismarck's Realpolitik

Realpolitik

Realpolitik refers to politics or diplomacy based primarily on power and on practical and material factors and considerations, rather than ideological notions or moralistic or ethical premises...

led a collection of early modern polities to reorganize political, economic, military and diplomatic relationships in the 19th century. Reaction to Danish and French nationalism

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

provided foci for expressions of German unity. Military successes—especially Prussian ones—in three regional wars generated enthusiasm and pride that politicians could harness to promote unification. This experience echoed the memory of mutual accomplishment in the Napoleonic Wars, particularly in the War of Liberation

War of the Sixth Coalition

In the War of the Sixth Coalition , a coalition of Austria, Prussia, Russia, the United Kingdom, Portugal, Sweden, Spain and a number of German States finally defeated France and drove Napoleon Bonaparte into exile on Elba. After Napoleon's disastrous invasion of Russia, the continental powers...

of 1813–14. By establishing a Germany without Austria, the political and administrative unification in 1871 at least temporarily solved the problem of dualism.

German-speaking Central Europe in the early nineteenth century

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

or the extensive Habsburg hereditary dominions. They ranged in size from the small and complex territories of the princely Hohenlohe

Hohenlohe

Hohenlohe is the name of a German princely family and the name of their principality.At first rulers of a county, its two branches were raised to the rank of principalities of the Holy Roman Empire in 1744 and 1764 respectively; in 1806 they lost their independence and their lands formed part of...

family branches to the sizable, well defined territories as the Kingdom of Bavaria

Kingdom of Bavaria

The Kingdom of Bavaria was a German state that existed from 1806 to 1918. The Bavarian Elector Maximilian IV Joseph of the House of Wittelsbach became the first King of Bavaria in 1806 as Maximilian I Joseph. The monarchy would remain held by the Wittelsbachs until the kingdom's dissolution in 1918...

and the Kingdom of Prussia

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

. Their governance varied: they included free imperial cities

Free Imperial City

In the Holy Roman Empire, a free imperial city was a city formally ruled by the emperor only — as opposed to the majority of cities in the Empire, which were governed by one of the many princes of the Empire, such as dukes or prince-bishops...

, also of different sizes, such as the powerful Augsburg

Augsburg

Augsburg is a city in the south-west of Bavaria, Germany. It is a university town and home of the Regierungsbezirk Schwaben and the Bezirk Schwaben. Augsburg is an urban district and home to the institutions of the Landkreis Augsburg. It is, as of 2008, the third-largest city in Bavaria with a...

and the minuscule Weil der Stadt

Weil der Stadt

Weil der Stadt is a small town of about 19,000 inhabitants, located in the Stuttgart Region of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is about west of Stuttgart city center, and is often called "Gate to the Black Forest"...

; ecclesiastical territories, also of varying sizes and influence, such as the wealthy Abbey of Reichenau and the powerful Archbishopric of Cologne

Archbishopric of Cologne

The Electorate of Cologne was an ecclesiastical principality of the Holy Roman Empire and existed from the 10th to the early 19th century. It consisted of the temporal possessions of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cologne . It was ruled by the Archbishop in his function as prince-elector of...

; and dynastic states such as Württemberg. These lands (or parts of them—both the Habsburg

Habsburg Monarchy

The Habsburg Monarchy covered the territories ruled by the junior Austrian branch of the House of Habsburg , and then by the successor House of Habsburg-Lorraine , between 1526 and 1867/1918. The Imperial capital was Vienna, except from 1583 to 1611, when it was moved to Prague...

domains and Hohenzollern Prussia also included territories outside the Empire structures) made up the territory of the Holy Roman Empire, which at times included more than 1,000 entities. Since the 15th century, with few exceptions, the Empire's Prince-elector

Prince-elector

The Prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire were the members of the electoral college of the Holy Roman Empire, having the function of electing the Roman king or, from the middle of the 16th century onwards, directly the Holy Roman Emperor.The heir-apparent to a prince-elector was known as an...

s had chosen successive heads of the House of Habsburg to hold the title of Holy Roman Emperor

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor is a term used by historians to denote a medieval ruler who, as German King, had also received the title of "Emperor of the Romans" from the Pope...

. Among the German-speaking states, the Holy Roman Empire administrative and legal mechanisms provided a venue to resolve disputes between peasants and landlords, and between and within separate jurisdictions. Through the organization of imperial circles (Reichskreise), groups of states consolidated resources and promoted regional and organizational interests, including economic cooperation and military protection.

The War of the Second Coalition

War of the Second Coalition

The "Second Coalition" was the second attempt by European monarchs, led by the Habsburg Monarchy of Austria and the Russian Empire, to contain or eliminate Revolutionary France. They formed a new alliance and attempted to roll back France's previous military conquests...

(1799–1802) resulted in the defeat of the imperial and allied forces by Napoleon Bonaparte; the treaties of Lunéville

Treaty of Lunéville

The Treaty of Lunéville was signed on 9 February 1801 between the French Republic and the Holy Roman Emperor Francis II, negotiating both on behalf of his own domains and of the Holy Roman Empire...

(1801) and Amiens

Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens temporarily ended hostilities between the French Republic and the United Kingdom during the French Revolutionary Wars. It was signed in the city of Amiens on 25 March 1802 , by Joseph Bonaparte and the Marquess Cornwallis as a "Definitive Treaty of Peace"...

(1802) and the Mediatization of 1803 transferred large portions of the Holy Roman Empire to the dynastic states; secularized ecclesiastical territories and most of the imperial cities disappeared from the political and legal landscape and the populations living in these territories acquired new allegiances to dukes and kings. This transfer particularly enhanced the territories of Württemberg

Kingdom of Württemberg

The Kingdom of Württemberg was a state that existed from 1806 to 1918, located in present-day Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It was a continuation of the Duchy of Württemberg, which came into existence in 1495...

and Baden

Grand Duchy of Baden

The Grand Duchy of Baden was a historical state in the southwest of Germany, on the east bank of the Rhine. It existed between 1806 and 1918.-History:...

. In 1806, after a successful invasion of Prussia and the defeat of Prussia and Russia at the joint battles of Jena-Auerstedt

Battle of Jena-Auerstedt

The twin battles of Jena and Auerstedt were fought on 14 October 1806 on the plateau west of the river Saale in today's Germany, between the forces of Napoleon I of France and Frederick William III of Prussia...

, Napoleon dictated the Treaty of Pressburg

Peace of Pressburg

The Peace of Pressburg refers to four peace treaties concluded in Pressburg . The fourth Peace of Pressburg of 1805 during the Napoleonic Wars is the best-known.-First:...

, in which the Emperor dissolved the Holy Roman Empire.

Rise of German nationalism under the Napoleonic System

Under the hegemonyHegemony

Hegemony is an indirect form of imperial dominance in which the hegemon rules sub-ordinate states by the implied means of power rather than direct military force. In Ancient Greece , hegemony denoted the politico–military dominance of a city-state over other city-states...

of the French Empire

First French Empire

The First French Empire , also known as the Greater French Empire or Napoleonic Empire, was the empire of Napoleon I of France...

(1804–1814), popular German nationalism thrived in the reorganized German states. Due in part to the shared experience (albeit under French dominance), various justifications emerged to identify "Germany" as a single state. For the German philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte was a German philosopher. He was one of the founding figures of the philosophical movement known as German idealism, a movement that developed from the theoretical and ethical writings of Immanuel Kant...

,

The first, original, and truly natural boundaries of states are beyond doubt their internal boundaries. Those who speak the same language are joined to each other by a multitude of invisible bonds by nature herself, long before any human art begins; they understand each other and have the power of continuing to make themselves understood more and more clearly; they belong together and are by nature one and an inseparable whole.

A common language may have been seen to serve as the basis of a nation, but, as contemporary historians of 19th century Germany noted, it took more than linguistic similarity to unify these several hundred polities. The experience of German-speaking Central Europe during the years of French hegemony contributed to a sense of common cause to remove the French invaders and reassert control over their own lands. The exigencies of Napoleon's campaigns in Poland

War of the Fourth Coalition

The Fourth Coalition against Napoleon's French Empire was defeated in a war spanning 1806–1807. Coalition partners included Prussia, Russia, Saxony, Sweden, and the United Kingdom....

(1806–07), the Iberian Peninsula

Peninsular War

The Peninsular War was a war between France and the allied powers of Spain, the United Kingdom, and Portugal for control of the Iberian Peninsula during the Napoleonic Wars. The war began when French and Spanish armies crossed Spain and invaded Portugal in 1807. Then, in 1808, France turned on its...

, western Germany, and his disastrous invasion of Russia

French invasion of Russia

The French invasion of Russia of 1812 was a turning point in the Napoleonic Wars. It reduced the French and allied invasion forces to a tiny fraction of their initial strength and triggered a major shift in European politics as it dramatically weakened French hegemony in Europe...

in 1812 disillusioned many Germans, princes and peasants alike. Napoleon's Continental System

Continental System

The Continental System or Continental Blockade was the foreign policy of Napoleon I of France in his struggle against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland during the Napoleonic Wars. It was a large-scale embargo against British trade, which began on November 21, 1806...

nearly ruined the Central European economy. The invasion of Russia included nearly 125,000 troops from German lands, and the loss of that army encouraged many Germans, both high- and low-born, to envision a Central Europe free of Napoleon's influence. The creation of such student militias as the Lützow Free Corps

Lützow Free Corps

Lützow Free Corps was a voluntary force of the Prussian army during the Napoleonic Wars. It was named after its commander, Ludwig Adolf Wilhelm von Lützow. They were also widely known as "Lützower Jäger" or "Schwarze Jäger" .-Origins:...

exemplified this tendency.

War of the Sixth Coalition

In the War of the Sixth Coalition , a coalition of Austria, Prussia, Russia, the United Kingdom, Portugal, Sweden, Spain and a number of German States finally defeated France and drove Napoleon Bonaparte into exile on Elba. After Napoleon's disastrous invasion of Russia, the continental powers...

culminated in the great battle of Leipzig

Battle of Leipzig

The Battle of Leipzig or Battle of the Nations, on 16–19 October 1813, was fought by the coalition armies of Russia, Prussia, Austria and Sweden against the French army of Napoleon. Napoleon's army also contained Polish and Italian troops as well as Germans from the Confederation of the Rhine...

, also known as the Battle of Nations. In October, 1813, more than 500,000 combatants engaged in ferocious fighting over three days, making it the largest European land-battle of the 19th century. The engagement resulted in a decisive victory for the Coalition of Austria, Russia, Prussia, Sweden and Saxony, and it ended French power east of the Rhine. Success encouraged the Coalition forces to pursue Napoleon across the Rhine; his army and his government collapsed, and the victorious Coalition incarcerated Napoleon on Elba

Elba

Elba is a Mediterranean island in Tuscany, Italy, from the coastal town of Piombino. The largest island of the Tuscan Archipelago, Elba is also part of the National Park of the Tuscan Archipelago and the third largest island in Italy after Sicily and Sardinia...

. During the brief Napoleonic restoration known as the 100 Days

Hundred Days

The Hundred Days, sometimes known as the Hundred Days of Napoleon or Napoleon's Hundred Days for specificity, marked the period between Emperor Napoleon I of France's return from exile on Elba to Paris on 20 March 1815 and the second restoration of King Louis XVIII on 8 July 1815...

of 1815, forces of the Seventh Coalition, including an Anglo-Allied army under the command of the Duke of Wellington

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

Field Marshal Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, KG, GCB, GCH, PC, FRS , was an Irish-born British soldier and statesman, and one of the leading military and political figures of the 19th century...

and a Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

n army under the command of Gebhard von Blücher

Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher

Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher, Fürst von Wahlstatt , Graf , later elevated to Fürst von Wahlstatt, was a Prussian Generalfeldmarschall who led his army against Napoleon I at the Battle of the Nations at Leipzig in 1813 and at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 with the Duke of Wellington.He is...

, were victorious at Waterloo

Battle of Waterloo

The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815 near Waterloo in present-day Belgium, then part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands...

(18 June 1815). The critical role played by Blücher's troops, especially after having to retreat from the field at Ligny

Battle of Ligny

The Battle of Ligny was the last victory of the military career of Napoleon I. In this battle, French troops of the Armée du Nord under Napoleon's command, defeated a Prussian army under Field Marshal Blücher, near Ligny in present-day Belgium. The bulk of the Prussian army survived, however, and...

the day before, helped to turn the tide of combat against the French. The Prussian cavalry pursued the defeated French in the evening of 18 June, sealing the allied victory. From the German perspective, the actions of Blücher's troops at Waterloo, and the combined efforts at Leipzig, offered a rallying point of pride and enthusiasm. This interpretation became a key building block of the Borussian myth

Borussian myth

The Borussian Myth or Borussian legend is the name given by 20th century historians of German history to the earlier idea that German unification was inevitable, and that it was Prussia's destiny to accomplish it. The Borussian myth is an example of a teleological argument...

expounded by the pro-Prussian nationalist historians later in the 19th century.

Reorganization of Central Europe and the rise of German dualism

Congress of Vienna

The Congress of Vienna was a conference of ambassadors of European states chaired by Klemens Wenzel von Metternich, and held in Vienna from September, 1814 to June, 1815. The objective of the Congress was to settle the many issues arising from the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars,...

established a new European political-diplomatic system based on the balance of power

Balance of power in international relations

In international relations, a balance of power exists when there is parity or stability between competing forces. The concept describes a state of affairs in the international system and explains the behavior of states in that system...

. This system reorganized Europe into spheres of influence

Sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence is a spatial region or conceptual division over which a state or organization has significant cultural, economic, military or political influence....

which, in some cases, suppressed the aspirations of the various nationalities, including the Germans and Italians. Generally, an enlarged Prussia and the 38 other states consolidated from the mediatized territories of 1803 were confederated within the Austrian Empire

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

's sphere of influence. The Congress established a loose German Confederation

German Confederation

The German Confederation was the loose association of Central European states created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to coordinate the economies of separate German-speaking countries. It acted as a buffer between the powerful states of Austria and Prussia...

(1815–1866), headed by Austria, with a "Federal Diet

Diet (assembly)

In politics, a diet is a formal deliberative assembly. The term is mainly used historically for the Imperial Diet, the general assembly of the Imperial Estates of the Holy Roman Empire, and for the legislative bodies of certain countries.-Etymology:...

" (called the Bundestag or Bundesversammlung

Bundesversammlung (German Confederation)

The Federal Assembly was the only central institution of the German Confederation from 1815 until 1848, and from 1850 until 1866. The Federal Assembly had its seat in the palais Thurn und Taxis in Frankfurt...

, an assembly of appointed leaders) which met in the city of Frankfurt am Main. In recognition of the imperial position traditionally held by the Habsburgs, the emperors of Austria became the titular presidents of this parliament. Problematically, the built-in Austrian dominance failed to take into account Prussia's 18th century emergence in Imperial politics. Ever since the Prince-Elector

Prince-elector

The Prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire were the members of the electoral college of the Holy Roman Empire, having the function of electing the Roman king or, from the middle of the 16th century onwards, directly the Holy Roman Emperor.The heir-apparent to a prince-elector was known as an...

of Brandenburg

Brandenburg

Brandenburg is one of the sixteen federal-states of Germany. It lies in the east of the country and is one of the new federal states that were re-created in 1990 upon the reunification of the former West Germany and East Germany. The capital is Potsdam...

had created himself King in Prussia

King in Prussia

King in Prussia was a title used by the Electors of Brandenburg from 1701 to 1772. Subsequently they used the title King of Prussia....

at the beginning of that century, their domains had steadily increased through war and inheritance. Prussia's consolidated strength became especially apparent during the War of the Austrian Succession

War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession – including King George's War in North America, the Anglo-Spanish War of Jenkins' Ear, and two of the three Silesian wars – involved most of the powers of Europe over the question of Maria Theresa's succession to the realms of the House of Habsburg.The...

and the Seven Years War under Frederick the Great. As Maria Theresa and Joseph

Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor

Joseph II was Holy Roman Emperor from 1765 to 1790 and ruler of the Habsburg lands from 1780 to 1790. He was the eldest son of Empress Maria Theresa and her husband, Francis I...

tried to restore Habsburg hegemony in the Holy Roman Empire, Frederick countered with the creation of the Fürstenbund

Fürstenbund

The Fürstenbund was a union of German minor princes in the Holy Roman Empire. It was formed in 1785 under the leadership of Frederick II of Prussia, to oppose the ambition of Emperor Joseph II to add Bavaria to the Habsburg domains....

(Union of Princes) in 1785. Austrian-Prussian dualism

German dualism

Austria and Prussia had a long running conflict and rivalry for supremacy in Central Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries, called in Germany. While wars were a part of the rivalry, it was also a race for prestige to be seen as the legitimate political force of the German-speaking peoples...

lay firmly rooted in old Imperial politics. Those balance of power manoeuvres were epitomised by the War of the Bavarian Succession, or "Potato War" among common folk. Even after the end of the Holy Roman Empire, this competition influenced the growth and development of nationalist movements in the 19th century.

Problems of reorganization

Despite the nomenclature of Diet (Assembly or Parliament), this institution should in no way be construed as a broadly, or popularly, elected group of representatives. Many of the states did not have constitutions, and those that did, such as the Duchy of BadenGrand Duchy of Baden

The Grand Duchy of Baden was a historical state in the southwest of Germany, on the east bank of the Rhine. It existed between 1806 and 1918.-History:...

, based suffrage

Suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply the franchise, distinct from mere voting rights, is the civil right to vote gained through the democratic process...

on strict property requirements which effectively limited suffrage to a small portion of the male population. Furthermore, this impractical solution did not reflect the new status of Prussia in the overall scheme. Although the Prussian army had been dramatically defeated in the 1806 battle of Jena-Auerstedt

Battle of Jena-Auerstedt

The twin battles of Jena and Auerstedt were fought on 14 October 1806 on the plateau west of the river Saale in today's Germany, between the forces of Napoleon I of France and Frederick William III of Prussia...

, it had made a spectacular come-back at Waterloo. Consequently, Prussian leaders expected to play a pivotal role in German politics.

Nationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

, stimulated by the experience of Germans in the Napoleonic period and initially allied with liberalism

Liberalism

Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,...

, shifted political, social and cultural relationships within the German states. In this context, one can detect its roots in the experience of Germans in the Napoleonic period. The Burschenschaft

Burschenschaft

German Burschenschaften are a special type of Studentenverbindungen . Burschenschaften were founded in the 19th century as associations of university students inspired by liberal and nationalistic ideas.-History:-Beginnings 1815–c...

student organizations and popular demonstrations such as those held at Wartburg

Wartburg

The Wartburg is a castle overlooking the town of Eisenach, Germany.Wartburg may also refer to:* Wartburgkreis, a district in Germany named after the Wartburg* Wartburg , former East German brand of automobiles, manufactured in Eisenach...

Castle in October 1817 contributed to a growing sense of unity among German speakers of Central Europe. Furthermore, implicit and sometimes explicit promises made during the War of Liberation

War of liberation

A War of liberation is a conflict which is primarily intended to bring freedom or independence to a nation or group. Examples might include a war to overthrow a colonial power, or to remove a dictator from power. Such wars are often unconventional...

engendered an expectation of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty or the sovereignty of the people is the political principle that the legitimacy of the state is created and sustained by the will or consent of its people, who are the source of all political power. It is closely associated with Republicanism and the social contract...

and widespread participation in the political process, promises which largely went unfulfilled once peace had been achieved. Agitation by student organizations led such conservative leaders as Klemens Wenzel, Prince von Metternich, to fear the rise of national sentiment; the assassination of German dramatist August von Kotzebue

August von Kotzebue

August Friedrich Ferdinand von Kotzebue was a German dramatist.One of Kotzebue's books was burned during the Wartburg festival in 1817. He was murdered in 1819 by Karl Ludwig Sand, a militant member of the Burschenschaften...

in March 1819 by a radical student seeking unification was followed on 20 September 1819 by the proclamation of the Carlsbad Decrees

Carlsbad Decrees

The Carlsbad Decrees were a set of reactionary restrictions introduced in the states of the German Confederation by resolution of the Bundesversammlung on 20 September 1819 after a conference held in the spa town of Carlsbad, Bohemia...

, which hampered intellectual leadership of the nationalist movement. Metternich was able to harness conservative outrage at the assassination to consolidate legislation that would further limit the press and constrain the rising liberal and nationalist movements. Consequently, these decrees drove the Burschenschaften underground, restricted the publication of nationalist materials, expanded censorship of the press and private correspondence, and limited academic speech by prohibiting university professors from encouraging nationalist discussion. The decrees were the subject of Johann Joseph von Görres'

Johann Joseph von Görres

Johann Joseph von Görres was a German writer and journalist.-Early life:Görres was born at Koblenz. His father was moderately well off, and sent his son to a Latin college under the direction of the Roman Catholic clergy...

pamphlet Teutschland [archaic: Deutschland] und die Revolution (Germany and the Revolution) (1820), in which he concluded that it was both impossible and undesirable to repress the free utterance of public opinion by reactionary measures.

Economic collaboration: the customs union

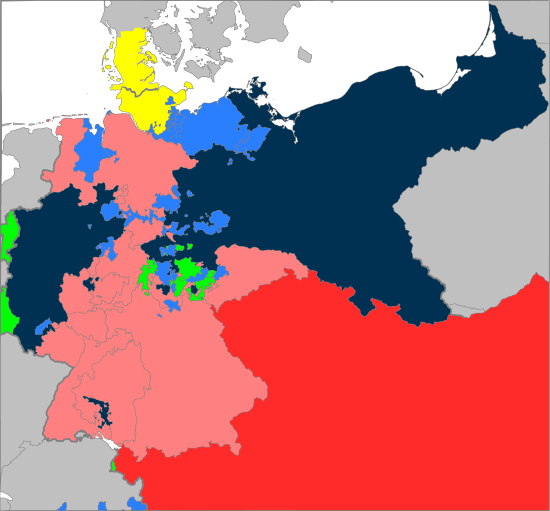

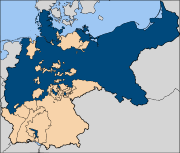

Another institution key to unifying the German states, the ZollvereinZollverein

thumb|upright=1.2|The German Zollverein 1834–1919blue = Prussia in 1834 grey= Included region until 1866yellow= Excluded after 1866red = Borders of the German Union of 1828 pink= Relevant others until 1834...

, helped to create a larger sense of economic unification. Initially conceived by the Prussian Finance Minister Hans, Count von Bülow

Hans, Count von Bülow

Ludwig Friedrich Victor Hans, Count von Bülow was a Westphalian and Prussian statesman....

, as a Prussian customs union

Customs union

A customs union is a type of trade bloc which is composed of a free trade area with a common external tariff. The participant countries set up common external trade policy, but in some cases they use different import quotas...

in 1818, the Zollverein linked the many Prussian and Hohenzollern territories. Over the ensuing thirty years (and more) other German states joined. The Union helped to reduce protectionist barriers among the German states, especially improving the transport of raw materials and finished goods, making it both easier to move goods across territorial borders, and less costly to buy, transport and sell raw materials. This was particularly important for the emerging industrial centers, most of which were located in the Rhineland

Rhineland

Historically, the Rhinelands refers to a loosely-defined region embracing the land on either bank of the River Rhine in central Europe....

, the Saar

Saar River

The Saar is a river in northeastern France and western Germany, and a right tributary of the Moselle. It rises in the Vosges mountains on the border of Alsace and Lorraine and flows northwards into the Moselle near Trier. It has two headstreams , that both start near Mont Donon, the highest peak...

, and the Ruhr valleys.

Roads and railroads

Macadam

Macadam is a type of road construction pioneered by the Scotsman John Loudon McAdam in around 1820. The method simplified what had been considered state-of-the-art at that point...

. By 1835, Heinrich von Gagern

Heinrich von Gagern

Heinrich Wilhelm August Freiherr von Gagern was a statesman who argued for the unification of Germany.The third son of Hans Christoph Ernst, Baron von Gagern, a liberal statesman from Hesse, Heinrich von Gagern was born at Bayreuth, educated at the military academy at Munich, and, as an officer in...

wrote that roads were the "veins and arteries of the body politic..." and predicted that they would promote freedom, independence and prosperity. As people moved around, they came into contact with others, on trains, at hotels, in restaurants, and, for some, at fashionable resorts such as the spa in Baden-Baden

Kurhaus (Baden-Baden)

The Kurhaus is a spa resort, casino, and conference complex in Baden-Baden, Germany in the outskirts of the Black Forest .-History:...

. Water transportation also improved. The blockades on the Rhine had been removed by Napoleon's orders, but by the 1820s, steam engines freed riverboats from the cumbersome system of men and animals that towed them upstream. By 1846, 180 steamers plied German rivers and Lake Constance

Lake Constance

Lake Constance is a lake on the Rhine at the northern foot of the Alps, and consists of three bodies of water: the Obersee , the Untersee , and a connecting stretch of the Rhine, called the Seerhein.The lake is situated in Germany, Switzerland and Austria near the Alps...

and a network of canals extended from the Danube

Danube

The Danube is a river in the Central Europe and the Europe's second longest river after the Volga. It is classified as an international waterway....

, the Weser and the Elbe

Elbe

The Elbe is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Krkonoše Mountains of the northwestern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia , then Germany and flowing into the North Sea at Cuxhaven, 110 km northwest of Hamburg...

rivers.

As important as these improvements were, they could not compete with the impact of the railroad. German economist Friedrich List

Friedrich List

Georg Friedrich List was a leading 19th century German economist who developed the "National System" or what some would call today the National System of Innovation...

called the railroads and the Customs Union "Siamese Twins", emphasizing their important relationship to one another. He was not alone: the poet August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben

August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben

' , who used Hoffmann von Fallersleben as his pen name, was a German poet. He is best known for writing "Das Lied der Deutschen", its third stanza now being the national anthem of Germany, and a number of popular children's songs.- Biography :Hoffmann was born in Fallersleben , Brunswick-Lüneburg,...

wrote a poem in which he extolled the virtues of the Zollverein, which he began with a list of commodities that had contributed more to German unity than politics or diplomacy. Historians of the Second Empire later regarded the railways as the first indicator of a unified state; the patriotic novelist, Wilhelm Raabe

Wilhelm Raabe

Wilhelm Raabe , German novelist, whose early works were published under the pseudonym of Jakob Corvinus, was born in Eschershausen ....

, wrote: "The German empire was founded with the construction of the first railway..." Not everyone greeted the iron monster with enthusiasm. The Prussian king Frederick William III saw no advantage in traveling from Berlin to Potsdam

Potsdam

Potsdam is the capital city of the German federal state of Brandenburg and part of the Berlin/Brandenburg Metropolitan Region. It is situated on the River Havel, southwest of Berlin city centre....

a few hours faster and Metternich refused to ride in one at all. Others wondered if the railways were an "evil" that threatened the landscape: Nikolaus Lenau

Nikolaus Lenau

Nikolaus Lenau was the nom de plume of Nikolaus Franz Niembsch Edler von Strehlenau , was a German language Austrian poet.-Biography:...

's 1838 poem An den Frühling (To Spring) bemoaned the way trains destroyed the pristine quietude of German forests.

The Bavarian Ludwig Railway, which was the first passenger or freight rail line in the German lands, connected Nuremberg

Nuremberg

Nuremberg[p] is a city in the German state of Bavaria, in the administrative region of Middle Franconia. Situated on the Pegnitz river and the Rhine–Main–Danube Canal, it is located about north of Munich and is Franconia's largest city. The population is 505,664...

and Fürth

Fürth

The city of Fürth is located in northern Bavaria, Germany in the administrative region of Middle Franconia. It is now contiguous with the larger city of Nuremberg, the centres of the two cities being only 7 km apart....

in 1835; it was 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) long, and operated only in daylight, but it proved both profitable and popular. Within three years, 141 kilometres (87.6 mi) of track had been laid; by 1840, 462 kilometres (287.1 mi) and by 1860, 11157 kilometres (6,932.7 mi). Lacking a geographically central organizing feature (such as a national capital), the rails were laid in webs, linking towns and markets within regions, regions within larger regions, and so on. As the rail network expanded, it became cheaper to transport goods: in 1840, 18 Pfennig

Pfennig

The Pfennig , plural Pfennige, is an old German coin or note, which existed from the 9th century until the introduction of the euro in 2002....

s per ton per kilometer and in 1870, five Pfennigs. The effects of the railway were immediate. For example, raw materials could travel up and down the Ruhr

Ruhr

The Ruhr is a medium-size river in western Germany , a right tributary of the Rhine.-Description:The source of the Ruhr is near the town of Winterberg in the mountainous Sauerland region, at an elevation of approximately 2,200 feet...

Valley, without having to unload and reload. Railway lines encouraged economic activity by creating demand for commodities and by facilitating commerce. In 1850, inland shipping carried three times more freight than railroads; by 1870, the situation was reversed, and railroads carried four times more. Railroads also changed how cities looked, how people traveled, and their impact reached throughout the social order: from the highest born to the lowest, the rails influenced everyone. Although some of the far-flung provinces were not connected to the rail system until the 1890s, by mid-century, certainly by 1865, the majority of population, manufacturing and production centers had been linked by rail.

Geography, patriotism and language

As travel became easier, faster, and less expensive, Germans started to see unity in factors other than their language. The Brothers GrimmBrothers Grimm

The Brothers Grimm , Jacob Grimm and Wilhelm Grimm , were German academics, linguists, cultural researchers, and authors who collected folklore and published several collections of it as Grimm's Fairy Tales, which became very popular...

, who compiled a massive dictionary known as The Grimm, also assembled a compendium of folk tales and fables, which highlighted the story-telling parallels between different regions. Karl Baedeker

Karl Baedeker

Karl Baedeker was a German publisher whose company Baedeker set the standard for authoritative guidebooks for tourists.- Biography :...

wrote guidebooks to different cities and regions of Central Europe, indicating places to stay, sites to visit, and giving a short history of castles, battlefields, famous buildings, and famous people. His guides also included distances, roads to avoid, and hiking paths to follow.

The words of August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben

August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben

' , who used Hoffmann von Fallersleben as his pen name, was a German poet. He is best known for writing "Das Lied der Deutschen", its third stanza now being the national anthem of Germany, and a number of popular children's songs.- Biography :Hoffmann was born in Fallersleben , Brunswick-Lüneburg,...

expressed not only the linguistic unity of the German people, but their geographic unity as well. In Deutschland, Deutschland über Alles, officially called Das Lied der Deutschen

Das Lied der Deutschen

The "'" , has been used wholly or partially as the national anthem of Germany since 1922. The music was written by Joseph Haydn in 1797 as an anthem for the birthday of the Austrian Emperor Francis II of the Holy Roman Empire...

(The Song of the Germans), Fallersleben called upon sovereigns throughout the German states to recognize the unifying characteristics of the German people. Such other patriotic songs as Die Wacht am Rhein

Die Wacht am Rhein

"Die Wacht am Rhein" is a German patriotic anthem. The song's origins are rooted in historical conflicts with France, and it was particularly popular in Germany during the Franco-Prussian War and the First World War....

(The Watch on the Rhine) by Max Schneckenburger

Max Schneckenburger

Max Schneckenburger was a German poet. The patriotic hymn "Die Wacht am Rhein" uses the text of a poem Schneckenburger wrote in 1840.Schneckenburger was born in Talheim near Tuttlingen, Württemberg...

began to focus attention on geographic space, not limiting "German-ness" to a common language. Schneckenburger wrote The Watch on the Rhine in a specific patriotic response to French assertions that the Rhine was France's "natural" eastern boundary. In the refrain, Dear Fatherland, Dear Fatherland, put your mind to Rest/The Watch stands true on the Rhine, and such other patriotic poetry as Nicholaus Becker's Das Rheinlied (the Song of the Rhine) called upon Germans to defend their territorial homeland. In 1807, Alexander von Humboldt

Alexander von Humboldt

Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander Freiherr von Humboldt was a German naturalist and explorer, and the younger brother of the Prussian minister, philosopher and linguist Wilhelm von Humboldt...

argued that national character reflected geographic influence, linking landscape to peoples. Concurrent with this idea, movements to preserve old fortresses and historic sites emerged, and these particularly focused on the Rhineland, the site of so many confrontations with France and Spain.

Vormärz and nineteenth century liberalism

The period of Austrian and Prussian police-states and vast censorship before the Revolutions of 1848 in Germany later became widely known as the VormärzVormärz

' is the time period leading up to the failed March 1848 revolution in the German Confederation. Also known as the Age of Metternich, it was a period of Austrian and Prussian police states and vast censorship in response to calls for liberalism...

, the "before March", referring to March 1848. During this period, European liberalism gained momentum; the agenda included economic, social, and political issues. Most European liberals in the Vormärz sought unification under nationalist principles, promoted the transition to capitalism, sought the expansion of male suffrage, among other issues. Their "radicalness" depended upon where they stood on the spectrum of male suffrage

Universal suffrage

Universal suffrage consists of the extension of the right to vote to adult citizens as a whole, though it may also mean extending said right to minors and non-citizens...

: the wider the definition of suffrage, the more radical.

Hambach Festival: liberal nationalism and conservative response

Despite considerable conservative reaction, ideas of unity joined with notions of popular sovereignty in German-speaking lands. The Hambach FestivalHambacher Fest

The Hambacher Fest was a German national democratic festival—disguised as a non-political county fair—that was celebrated from 27 May to 30 May 1832 at Hambach Castle near Neustadt an der Weinstraße ....

in May 1832 was attended by a crowd of more than 30,000. Promoted as a county fair

County Fair

"County Fair" is a song written by Brian Wilson and Gary Usher for the American rock band The Beach Boys. It was originally released as the second track on their 1962 album Surfin' Safari. On November 26th of that year, it was released as the B-side to The Beach Boys' third single, "Ten Little...

, its participants celebrated fraternity, liberty, and national unity. Celebrants gathered in the town below and marched to the ruins of Hambach Castle

Hambach Castle

Hambach Castle near the urban district Hambach of Neustadt an der Weinstraße in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, is considered to be the symbol of the German democracy movement because of the Hambacher Fest which occurred here in 1832.- Location :...

on the heights above the small town of Hambach, in the Palatinate province of Bavaria. Carrying flags, beating drums, and singing, the participants took the better part of the morning and mid-day to arrive at the castle grounds, where they listened to speeches by nationalist orators from across the conservative to radical political spectrum. The overall content of the speeches suggested a fundamental difference between the German nationalism of the 1830s and the French nationalism of the July Revolution

July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution or in French, saw the overthrow of King Charles X of France, the French Bourbon monarch, and the ascent of his cousin Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, who himself, after 18 precarious years on the throne, would in turn be overthrown...

: the focus of German nationalism lay in the education of the people; once the populace was educated as to what was needed, they would accomplish it. The Hambach rhetoric emphasized the overall peaceable nature of German nationalism: the point was not to build barricades, a very "French" form of nationalism, but to build emotional bridges between groups.

As he had done in 1819, after the Kotzebue

August von Kotzebue

August Friedrich Ferdinand von Kotzebue was a German dramatist.One of Kotzebue's books was burned during the Wartburg festival in 1817. He was murdered in 1819 by Karl Ludwig Sand, a militant member of the Burschenschaften...

assassination, Metternich used the popular demonstration at Hambach to push conservative social policy. The "Six Articles" of 28 June 1832, primarily reaffirmed the principle of monarchical authority. On 5 July, the Frankfurt Diet voted for an additional 10 articles, which reiterated existing rules on censorship, restricted political organizations, and limited other public activity. Furthermore, the member states agreed to send military assistance to any government threatened by unrest. Prince Wrede

Karl Philipp von Wrede

Karl Philipp Josef Wrede, Freiherr von Wrede, 1st Fürst von Wrede , Bavarian field-marshal, was born at Heidelberg, the youngest of three children of Ferdinand Josef Wrede , created in 1791 1st Freiherr von Wrede, and wife, married on 21 March 1746, Anna Katharina Jünger , by whom he had two more...

led half of the Bavarian army to the Palatinate to "subdue" the province. Several hapless Hambach speakers were arrested, tried and imprisoned; one, Karl Heinrich Brüggemann (1810–1887), a law student and representative of the secretive Burschenschaft, was sent to Prussia, where he was first condemned to death, but later pardoned.

Liberalism and the response to economic problems

Several other factors complicated the rise of nationalismNationalism

Nationalism is a political ideology that involves a strong identification of a group of individuals with a political entity defined in national terms, i.e. a nation. In the 'modernist' image of the nation, it is nationalism that creates national identity. There are various definitions for what...

in the German states. The man-made factors included political rivalries between members of the German confederation, particularly between the Austrians and the Prussians, and socio-economic competition among the commercial and merchant interests and the old land-owning and aristocratic interests. Natural factors included widespread drought in the early 1830s, and again in the 1840s, and a food crisis in the 1840s. Further complications emerged as a result of a shift in industrialization and manufacturing; as people sought jobs, they left their villages and small towns to work during the week in the cities, returning for a day and a half on weekends.

The economic, social and cultural dislocation of ordinary people, the economic hardship of an economy in transition, and the pressures of meteorological disasters all contributed to growing problems in Central Europe. The failure of most of the governments to deal with the food crisis of the mid-1840s, caused by the potato blight

Phytophthora infestans

Phytophthora infestans is an oomycete that causes the serious potato disease known as late blight or potato blight. . Late blight was a major culprit in the 1840s European, the 1845 Irish and 1846 Highland potato famines...

(related to the Great Irish Famine) and several seasons of bad weather, encouraged many to think that the rich and powerful had no interest in their problems. Those in authority were concerned about the growing unrest, political and social agitation among the working classes, and the disaffection of the intelligentsia

Intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a social class of people engaged in complex, mental and creative labor directed to the development and dissemination of culture, encompassing intellectuals and social groups close to them...

. No amount of censorship, fines, imprisonment, or banishment, it seemed, could stem the criticism. Furthermore, it was becoming increasingly clear that both Austria and Prussia wanted to be the leaders in any resulting unification; each would inhibit the drive of the other to achieve unification.

First efforts at unification

Crucially, both the Wartburg rally in 1817 and the Hambach Festival in 1832 had lacked any clear-cut program of unification. At Hambach, the positions of the many speakers illustrated their disparate agendas. Held together only by the idea of unification, their notions of how to achieve this did not include specific plans, but rested on the nebulous idea that the Volk (the people), if properly educated, would bring about unification on their own. Grand speeches, flags, exuberant students, and picnic lunches did not translate into a new political, bureaucratic and administrative apparatus; no constitution miraculously appeared, although there was indeed plenty of talk of constitutions. In 1848, nationalists sought to remedy that problem.German revolutions of 1848 and the Frankfurt Parliament

The widespread German revolutions of 1848–1849 targeted unification and a single German constitution. The revolutionaries pressured various state governments, particularly strong in the RhinelandRhineland

Historically, the Rhinelands refers to a loosely-defined region embracing the land on either bank of the River Rhine in central Europe....

, for a parliamentary assembly which would have the responsibility to draft constitution. Ultimately, many of the left-wing revolutionaries hoped this constitution would establish universal male suffrage

Universal suffrage

Universal suffrage consists of the extension of the right to vote to adult citizens as a whole, though it may also mean extending said right to minors and non-citizens...

, a permanent national parliament, and a unified Germany, possibly under the leadership of the Prussian king, who appeared to be the most logical candidate: Prussia was the largest state in size, and also the strongest. Generally, revolutionaries to the right-of-center sought some kind of expanded suffrage within their states and, potentially, a form of loose unification. Their pressure resulted in a variety of elections, based on different voting qualifications, such as the Prussian three-class franchise

Prussian three-class franchise

After the 1848 revolutions in the German states, the Prussian three-class franchise system was introduced in 1849 by the Prussian king Friedrich Wilhelm IV for the election of the Lower House of the Prussian state parliament. It was completely abolished only in 1918...

, which granted to some electoral groups, chiefly the wealthier, landed ones, greater representative power.

Frankfurt Parliament

The Frankfurt Assembly was the first freely elected parliament for all of Germany. Session was held from May 18, 1848 to May 31, 1849 in the Paulskirche at Frankfurt am Main...

passed the Paulskirchenverfassung

Paulskirchenverfassung

The Constitution of the German Empire of 1849, more commonly known as the Frankfurt Constitution or Paulskirchenverfassung , was an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to created a unified German state under an Emperor...

(Constitution of St. Paul's Church) and in April 1849 it offered the title of Kaiser (Emperor) to the Prussian king, Frederick William IV. He refused for a variety of reasons. Publicly, he replied that he could not accept a crown without the consent of the actual states, by which he meant the princes. Privately, he feared the opposition of the other German princes and the military intervention of Austria and Russia; he also held a fundamental distaste for the idea of accepting a crown from a popularly elected parliament: he could not accept a crown of "clay", he said. Despite franchise requirements that often perpetuated many of the problems of sovereignty and political participation liberals sought to overcome, the Frankfurt Parliament did manage to draft a constitution, and reach agreement on the kleindeutsch solution. The Frankfurt Parliament ended in partial failure: while the liberals did not achieve the unification they sought, they did manage to work through many constitutional issues and collaborative reforms with the German princes.

1848 and the Frankfurt Parliament in retrospective analysis

The successes and failures of the Frankfurt Parliament have occasioned decades of debate among historians of the German past and contribute to the historiographical explanations of German nation building. One school of thought, which emerged after 1918 and gained momentum in the aftermath of World War II, maintained that the so-called failure of the German liberals in the Frankfurt Parliament led to the bourgeoisie'sBourgeoisie

In sociology and political science, bourgeoisie describes a range of groups across history. In the Western world, between the late 18th century and the present day, the bourgeoisie is a social class "characterized by their ownership of capital and their related culture." A member of the...

compromise with the conservatives, especially conservative Prussian landholders (Junker

Junker

A Junker was a member of the landed nobility of Prussia and eastern Germany. These families were mostly part of the German Uradel and carried on the colonization and Christianization of the northeastern European territories during the medieval Ostsiedlung. The abbreviation of Junker is Jkr...

s), and subsequently, to Germany's so-called Sonderweg

Sonderweg

Sonderweg is a controversial theory in German historiography that considers the German-speaking lands, or the country Germany, to have followed a unique course from aristocracy into democracy, distinct from other European countries...

(distinctive path) in the 20th century. Failure to achieve unification in 1848, this argument holds, resulted in the late formation of the nation-state in 1871, which in turn delayed the development of positive national values. Furthermore, this argument maintains, the "failure" of 1848 reaffirmed latent aristocratic longings among the German middle class; consequently, this group never developed a self-conscious program of modernization.

More recent scholarship has opposed this idea, claiming that Germany did not have an actual Sonderweg, any more than any nation's history takes its own distinctive path, an historiographic idea known as exceptionalism

Exceptionalism

Exceptionalism is the perception that a country, society, institution, movement, or time period is "exceptional" in some way and thus does not need to conform to normal rules or general principles...

. Instead, this new group of historians claims 1848 marked specific achievements by the liberal politicians; many of their ideas and programs later were incorporated into Bismarck's social programs (for example, social insurance, education programs, and wider definitions of suffrage). In addition, the notion of a unique path relies upon the fact that some other nation's path (in this case, Britain's) is the accepted norm. This new argument further challenges the norms of the British model, and recent studies of national development in Britain and other "normal" states (for example, France and the United States) have suggested that even in these states, the modern nation did not develop evenly, or particularly early, but was largely a mid-to-late-19th-century proposition. By the end of the 1990s, this latter view became the accepted view, although some historians still find the Sonderweg analysis helpful in understanding the period of National Socialism.

.jpg)

Problem of spheres of influence: The Erfurt Union and the Punctation of Olmütz

After the Frankfurt Parliament disbanded, Frederick William IV, under the influence of General Joseph Maria von RadowitzJoseph von Radowitz

Joseph Maria Ernst Christian Wilhelm von Radowitz was a conservative Prussian statesman and general famous for his proposal to unify Germany under Prussian leadership by means of a negotiated agreement among the reigning German princes.-Early years:Radowitz was born to Roman Catholic nobility on ...

, supported the establishment of the Erfurt Union

Erfurt Union

The Erfurt Union was a short-lived union of German states under a federation, proposed by the Kingdom of Prussia at Erfurt, for which the Erfurt Union Parliament , lasting from March 20 to April 29, 1850, was opened...

, a federation of German states, excluding Austria, by the free agreement of the German princes. This limited union under Prussia would have almost entirely eliminated the Austrian influence among the other German states. Combined diplomatic pressure from Austria and from Russia (a guarantor of the 1815 agreements that established European spheres of influence) forced Prussia to relinquish the idea of the Erfurt Union at a meeting in the small town of Olmütz

Olomouc

Olomouc is a city in Moravia, in the east of the Czech Republic. The city is located on the Morava river and is the ecclesiastical metropolis and historical capital city of Moravia. Nowadays, it is an administrative centre of the Olomouc Region and sixth largest city in the Czech Republic...

in Moravia. In November 1850 the Prussians, specifically Radowitz and Frederick William, agreed to the restoration of the German Confederation under Austrian leadership. This became known as the Punctation of Olmütz

Punctation of Olmütz

The Punctation of Olmütz , also called the Agreement of Olmütz, was a treaty between Prussia and Austria, dated 29 November 1850, by which Prussia abandoned the Erfurt Union and accepted the revival of the German Confederation under Austrian leadership....

, also known to the Prussians as the "Humiliation of Olmütz."

Although seemingly minor events, the Erfurt Union proposal and the Punctation of Olmütz bring the problems of influence in the German states into sharp focus. The question of unification became not a matter of if, but when, and when was contingent upon strength. One of the former Frankfurt Parliament members, Johann Gustav Droysen

Johann Gustav Droysen

Johann Gustav Droysen was a German historian. His history of Alexander the Great was the first work representing a new school of German historical thought that idealized power held by so-called "great" men...

, summed up the problem succinctly:

We cannot conceal the fact that the whole German questionGerman questionThe German question was a debate in the 19th century, especially during the Revolutions of 1848, over the best way to achieve the Unification of Germany. From 1815–1871, a number of 37 independent German-speaking states existed within the German Confederation...

is a simple alternative between Prussia and Austria. In these states, German life has its positive and negative poles—in the former, all the interests which are national and reformative, in the latter, all that are dynastic and destructive. The German question is not a constitutional question, but a question of power; and the Prussian monarchy is now wholly German, while that of Austria cannot be.

Unification under these conditions raised a basic diplomatic problem. The possibility of German unification (and indeed Italian unification

Italian unification

Italian unification was the political and social movement that agglomerated different states of the Italian peninsula into the single state of Italy in the 19th century...

) challenged the fundamental precepts of balance laid out in 1815; unification of these groups of states would overturn the principles of overlapping spheres of influence

Sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence is a spatial region or conceptual division over which a state or organization has significant cultural, economic, military or political influence....

. Metternich, Castlereagh

Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh

Robert Stewart, 2nd Marquess of Londonderry, KG, GCH, PC, PC , usually known as Lord CastlereaghThe name Castlereagh derives from the baronies of Castlereagh and Ards, in which the manors of Newtownards and Comber were located...

and Tsar Alexander

Alexander I of Russia

Alexander I of Russia , served as Emperor of Russia from 23 March 1801 to 1 December 1825 and the first Russian King of Poland from 1815 to 1825. He was also the first Russian Grand Duke of Finland and Lithuania....

(and his foreign secretary Count Karl Nesselrode

Karl Nesselrode

Baltic-German Count Karl Robert Nesselrode, also known as Charles de Nesselrode, was a Russian diplomat and a leading European conservative statesman of the Holy Alliance...

), the principal architects of this convention, had conceived of and organized a Europe (and indeed a world) balanced by and guaranteed by four powers: Great Britain, France, Russia, and Austria. Each power had its geographic sphere of influence; for France, this sphere included the Iberian peninsula and shared influence in the Italian states; for the Russians, the eastern regions of Central Europe, and balancing influence in the Balkans; for the Austrians, this sphere included much of the Central European territories of the old Reich (Holy Roman Empire); and for the British, the rest of the world, especially the seas.

The system of spheres of influence in Europe depended upon the fragmentation of the German and Italian states, not their consolidation. Consequently, a German nation united under one banner presented significant questions: Who were the Germans? Where was Germany?, but also, Who was in charge?, and, importantly, Who could best defend "Germany", whoever, whatever, and wherever it was? Different groups offered different solutions to this problem. In the Kleindeutschland (little, or "lesser", Germany) solution, the German states would be united under the leadership of Prussia; in the Grossdeutschland (Greater Germany) solution, the German states would be united under the leadership of the Austrian state. This controversy, the latest phase of the German dualism

German dualism

Austria and Prussia had a long running conflict and rivalry for supremacy in Central Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries, called in Germany. While wars were a part of the rivalry, it was also a race for prestige to be seen as the legitimate political force of the German-speaking peoples...

that had dominated the politics of the German states and Austro-Prussian diplomacy since the creation of the Kingdom of Prussia

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

in 1701, came to a head during the next twenty years.

External expectations of a unified Germany

Other nationalists had high hopes for the movement of German unification, and the frustration of lasting German unification after 1850 seemed to set the national movement back. Revolutionaries associated national unification with progress. As Giuseppe GaribaldiGiuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Garibaldi was an Italian military and political figure. In his twenties, he joined the Carbonari Italian patriot revolutionaries, and fled Italy after a failed insurrection. Garibaldi took part in the War of the Farrapos and the Uruguayan Civil War leading the Italian Legion, and...

wrote to German revolutionary Karl Blind

Karl Blind

Karl Blind was a German revolutionist and journalist. He was born in Mannheim on 4 September 1826 and died in London on 31 May 1907.Blind took part in the risings of 1848. He was sentenced to prison in consequence of a pamphlet he wrote entitled "German Hunger and German Princes," but he was...

on 10 April 1865, "The progress of humanity seems to have come to a halt, and you with your superior intelligence will know why. The reason is that the world lacks a nation which possesses true leadership. Such leadership, of course, is required not to dominate other peoples, but to lead them along the path of duty, to lead them toward the brotherhood of nations where all the barriers erected by egoism will be destroyed." Garibaldi looked to Germany for the "kind of leadership which, in the true tradition of medieval chivalry, would devote itself to redressing wrongs, supporting the weak, sacrificing momentary gains and material advantage for the much finer and more satisfying achievement of relieving the suffering of our fellow men. We need a nation courageous enough to give us a lead in this direction. It would rally to its cause all those who are suffering wrong or who aspire to a better life, and all those who are now enduring foreign oppression."

German unification had also been viewed as a prerequisite for the creation of a European federation, which Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini

Giuseppe Mazzini , nicknamed Soul of Italy, was an Italian politician, journalist and activist for the unification of Italy. His efforts helped bring about the independent and unified Italy in place of the several separate states, many dominated by foreign powers, that existed until the 19th century...

and other European patriots had been promoting for more than three decades.

In the Spring of 1834, while at BerneBerneThe city of Bern or Berne is the Bundesstadt of Switzerland, and, with a population of , the fourth most populous city in Switzerland. The Bern agglomeration, which includes 43 municipalities, has a population of 349,000. The metropolitan area had a population of 660,000 in 2000...

, Mazzini and a dozen refugees from Italy, Poland and Germany founded a new association with the grandiose name of Young Europe. Its basic, and equally grandiose idea, was that, as the French Revolution of 1789 had enlarged the concept of individual liberty, another revolution would now be needed for national liberty; and his vision went further because he hoped that in the no doubt distant future free nations might combine to form a loosely federal Europe with some kind of federal assembly to regulate their common interests. [...] His intention was nothing less than to overturn the European settlement agreed in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna, which had reestablished an oppressive hegemony of a few great powers and blocked the emergence of smaller nations. [...] Mazzini hoped, but without much confidence, that his vision of a league or society of independent nations would be realized in his own lifetime. In practice Young Europe lacked the money and popular support for more than a short-term existence. Nevertheless he always remained faithful to the ideal of a united continent for which the creation of individual nations would be an indispensable preliminary.

Prussia's growing strength: Realpolitik

Helmuth von Moltke the Elder

Helmuth Karl Bernhard Graf von Moltke was a German Field Marshal. The chief of staff of the Prussian Army for thirty years, he is regarded as one of the great strategists of the latter 19th century, and the creator of a new, more modern method of directing armies in the field...

held the position of chief of the Prussian General Staff and Albrecht von Roon, that of the Prussian Minister of War

Prussian Minister of War

The Prussian War Ministry was gradually established between 1808 and 1809 as part of a series of reforms initiated by the Military Reorganization Commission created after the disastrous Treaty of Paris. The War Ministry was to help bring the army under constitutional control, and, along with the...

. Von Roon and Wilhelm (who took an active interest in such things) reorganized the Prussian army and Moltke redesigned the strategic defense of Prussia, streamlining operational command. Army reforms (and how to pay for them) caused a constitutional crisis

Constitutional crisis