War of the Austrian Succession

Encyclopedia

The War of the Austrian Succession (1740–48) – including King George's War

in North America, the Anglo-Spanish

War of Jenkins' Ear

, and two of the three Silesian wars

– involved most of the powers

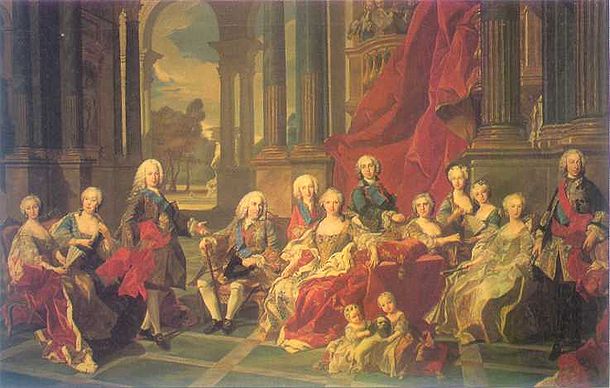

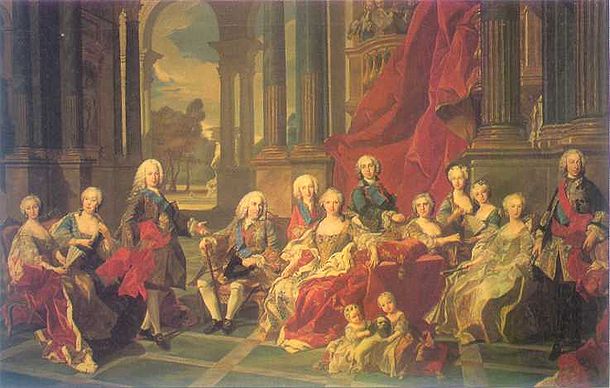

of Europe over the question of Maria Theresa's

succession to the realms of the House of Habsburg.

The war began under the pretext that Maria Theresa was ineligible to succeed to the Habsburg thrones of her father, Charles VI

, because Salic law

precluded royal inheritance by a woman—though in reality this was a convenient excuse put forward by Prussia

and France

to challenge Habsburg power. Austria was supported by Great Britain

and the Dutch Republic

, the traditional enemies of France, as well as the Kingdom of Sardinia

and Saxony

. France and Prussia were allied with the Electorate of Bavaria

.

Spain entered the war to reestablish its influence in northern Italy, further reversing an Austrian dominance over the Italian peninsula that had been achieved at Spain's expense as a consequence of that country's own war of succession

earlier in the 18th century.

The war ended with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle

in 1748. The most enduring military historical interest and importance of the war lies in the struggle of Prussia

and the Habsburg

monarchs for the region of Silesia

.

In 1740, after the death of her father, Charles VI

In 1740, after the death of her father, Charles VI

, Maria Theresa succeeded him as Queen of Hungary, Croatia

and Bohemia, Archduchess of Austria and Duchess of Parma. Her father had been Holy Roman Emperor, but Maria Theresa was not a candidate for that title, which had never been held by a woman; the plan was for her to succeed to the hereditary domains, and her husband, Francis Stephen

, to be elected Holy Roman Emperor. The complications involved in a female Habsburg ruler had been long foreseen, and Charles VI had persuaded most of the states of Germany to agree to the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713

.

Problems began when King Frederick II of Prussia

violated the Pragmatic Sanction and invaded Silesia

on 16 December 1740, using the Treaty of Brieg of 1537 under which the Hohenzollerns

of Brandenburg

were to inherit the Duchy of Brieg as a pretext. Maria Theresa, as a woman, was perceived as weak, and other rulers (such as Charles Albert of Bavaria

) put forward their own competing claims to the crown

as male heirs with a clear genealogical basis to inherit the elected dignities

of the great Imperial title.

Prussia in 1740 was a small and thoroughly organized emerging international power

with a brand new well educated king, Frederick II of Prussia

, desiring to unify the disparate and scattered crown holdings by gathering intervening lands into a unified contiguous state. When the Holy Roman Emperor died, distracting the Habsburg Monarchy to the south east, Frederick turned opportunist using a questionable interpretation of a treaty (1537) between the Hohenzollerns and the Piasts of Brieg as pretext (reversing Prussia's position in the War of the Polish Succession

, concluded the year 1738, just two years before) to invade and snap up territories in Silesia. Meanwhile, as expected, the other princes of Europe prepared to exploit an opportunity to acquire Habsburg possessions and humble and diminish the power of the great house that an election of the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire

represented. Archduchess of Austria and Queen of Hungary she may be, but salic law

guaranteed the next Emperor was not going to be Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria.

While the only recent war experience of its army had been in the War of the Polish Succession

(Rhine campaign of 1733–1735) her forces hadn't fought there, since Frederick William was not trusted by Austria. It therefore had an uninspiring reputation and was counted as one of the many minor armies of the princes of Europe, of which there were plenty (See the 1800 plus states of the Holy Roman Empire

).

Only few thought that it could rival the larger modern forces of Austria and France. But King Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia had drilled it to a perfection previously unknown in Europe's military experience, and the Prussian infantry

soldier was so well-trained and well-equipped that he could fire 3 shots a minute to an Austrian's 1.Prussian cavalry

and artillery

were comparatively less efficient, but they were still of better quality than average.

The initial advantage of Frederick's army was that, undisturbed by wars, it had developed the professional standing-army

concept to full maturity and effect. While the Austrians had to wait for conscription to complete the field forces, Prussian regiments took the field at once, and thus Frederick was able to overrun Silesia almost unopposed.

In any event, his army had massed quietly along the Oder River during early December, and on 16 December 1740, without declaration of war, it crossed the frontier into Silesia. The extant forces available to the local Austrian generals could do no more than garrison

a few fortresses

, and they necessarily fell back to the mountain frontier of Bohemia

and Moravia

with only a small remnant of their available forces left in the garrisons.

On their new territory, the organized Prussian army was soon able to go into winter quarters, holding all Silesia and investing the strong places of Glogau, Brieg

and Neisse

. In one step, Prussia had effectively doubled its population and made huge gains in its industrial productivity for the minor cost of fair treatment of the people in the occupied territory—an atypical factor and effect in a day when relatively undisciplined mercenary

forces were the rule rather than the exception with their habitual raping, looting, and abuse of the various populations around themselves – which were generally forced to provide quarters.

Nationalism as we know it today, was not a factor, but an evolving concept just coming into its early years. Prussia benefited greatly from the apolitical nature of the society of the era, as the masses in central Germany would correspondingly suffer as the contending armies rampaged through their plains yet again.

and advanced towards Vienna

, but the objective was suddenly changed, and after many countermarches the anti-Austrian allies advanced, in three widely separated corps

, on Prague

. A French corps moved via Amberg

and Pilsen. The Elector marched on Budweis, and the Saxons (who had now joined the allies) invaded Bohemia

by the Elbe

valley. The Austrians could at first offer little resistance, but before long a considerable force intervened at Tábor

between the Danube and the allies, and the Austrian general Wilhelm Reinhard von Neipperg

was now on the march from Neisse to join in the campaign

. He had made with Frederick the curious agreement of Klein Schnellendorf (9 October 1741), by which Neisse was surrendered after a mock siege, and the Austrians undertook to leave Frederick unmolested in return for his releasing Neipperg's army for service elsewhere. At the same time the Hungarians

, moved to enthusiasm by the personal appeal of Maria Theresia, had put into the field a levée en masse, or "insurrection," which furnished the regular army with an invaluable force of light troops. A fresh army was collected under Field Marshal Khevenhüller at Vienna, and the Austrians planned an offensive winter campaign against the Franco-Bavarian forces in Bohemia and the small Bavarian army that remained on the Danube to defend the electorate.

The French in the meantime had stormed Prague on 26 November 1741, Francis Stephen

, husband of Maria Theresa, who commanded the Austrians in Bohemia, moving too slowly to save the fortress. The Elector of Bavaria, who now styled himself Archduke of Austria, was crowned King of Bohemia (9 December 1741) and elected to the imperial throne as Charles VII

(24 January 1742), but no active measures were undertaken.

In Bohemia the month of December was occupied in mere skirmishes. On the Danube, Khevenhüller, the best general in the Austrian service, advanced on 27 December, swiftly drove back the allies, shut them up in Linz

, and pressed on into Bavaria. Munich

itself surrendered to the Austrians on the coronation

day of Charles VII.

At the close of this first act of the campaign the French, under the old Marshal de Broglie

, maintained a precarious foothold in central Bohemia, menaced by the main army of the Austrians, and Khevenhüller was ranging unopposed in Bavaria. Frederick made a secret truce with Austria and thus, lay inactive in Silesia.

Frederick had hoped by the truce to secure Silesia, for which alone he was fighting. But with the successes of Khevenhüller and the enthusiastic "insurrection" of Hungary, Maria Theresa's opposition became firmer, and she divulged the provisions of the truce

Frederick had hoped by the truce to secure Silesia, for which alone he was fighting. But with the successes of Khevenhüller and the enthusiastic "insurrection" of Hungary, Maria Theresa's opposition became firmer, and she divulged the provisions of the truce

, in order to compromise Frederick with his allies. The war recommenced. Frederick had not rested on his laurels. In the uneventful summer campaign of 1741 he had found time to begin that reorganization of his cavalry which was before long to make it even more efficient than his infantry. The Emperor Charles VII, whose territories were overrun by the Austrians, asked him to create a diversion by invading Moravia. In December 1741, therefore, the Prussian general field marshal Kurt Christoph Graf von Schwerin

had crossed the border and captured Olmutz. Glatz also was invested

, and the Prussian army was concentrated about Olomouc in January 1742. A combined plan of operations

was made by the French, Saxons and Prussians for the rescue of Linz. But Linz soon fell. Broglie on the Vltava

, weakened by the departure of the Bavarians to oppose Khevenhüller, and of the Saxons to join forces with Frederick, was in no condition to take the offensive, and large forces under Prince Charles of Lorraine

lay in his front from Budweis to Jihlava

(Iglau). Frederick's march was made towards Iglau in the first place. Brno

was invested about the same time (February), but the direction of the march was changed, and instead of moving against Prince Charles, Frederick pushed on southwards by Znojmo

and Mikulov

. The extreme outposts of the Prussians appeared before Vienna. But Frederick's advance was a mere foray, and Prince Charles, leaving a screen of troops in front of Broglie, marched to cut off the Prussians from Silesia, while the Hungarian levies

poured into Upper Silesia

by the Jablunkov Pass

. The Saxons, discontented and demoralized, soon marched off to their own country, and Frederick with his Prussians fell back by Svitavy

and Litomyšl

to Kutná Hora

in Bohemia, where he was in touch with Broglie on the one hand and (Glatz having now surrendered) with Silesia on the other. No defence of Olomouc was attempted, and the small Prussian corps remaining in Moravia fell back towards Upper Silesia.

Prince Charles, in pursuit of the king, marched by Jihlava and Teutsch (Deutsch) Brod on Kutná Hora, and on 17 May was fought the Battle of Chotusitz

, in which after a severe struggle the king was victorious. His cavalry on this occasion retrieved its previous failure, and its conduct gave an earnest of its future glory not only by its charges

on the battlefield, but by its vigorous pursuit of the defeated Austrians. Almost at the same time Broglie fell upon a part of the Austrians left on the Vltava and won a small, but morally and politically important, success in the action of Sahay

, near Budweis (24 May 1742). Frederick did not propose another combined movement. His victory and that of Broglie disposed Maria Theresa to cede Silesia in order to make good her position elsewhere, and the separate peace between Prussia and Austria, signed at Breslau on 11 June, closed the First Silesian War, but the War of the Austrian Succession continued.

1743 opened disastrously for the emperor. The French and Bavarian armies were not working well together, and Broglie actually quarreled with the Bavarian field marshal Friedrich Heinrich von Seckendorff. No connected resistance was offered to the converging march of Prince Charles's army along the Danube, Khevenhüller from Salzburg towards southern Bavaria, and Prince Lobkowitz from Bohemia towards the Naab

1743 opened disastrously for the emperor. The French and Bavarian armies were not working well together, and Broglie actually quarreled with the Bavarian field marshal Friedrich Heinrich von Seckendorff. No connected resistance was offered to the converging march of Prince Charles's army along the Danube, Khevenhüller from Salzburg towards southern Bavaria, and Prince Lobkowitz from Bohemia towards the Naab

. The Bavarians suffered a severe reverse near Braunau

(9 May 1743), and now an Anglo-allied army commanded by King George II

, which had been formed on the lower Rhine on the withdrawal of Maillebois, was advancing southward to the Main and Neckar

country. A French army, under Marshal Noailles, was being collected on the middle Rhine to deal with this new force. But Broglie was now in full retreat, and the strong places of Bavaria surrendered one after the other to Prince Charles. The French and Bavarians had been driven almost to the Rhine when Noailles and the king came to battle. George, completely outmaneuvered by his veteran antagonist, was in a position of the greatest danger between Aschaffenburg

and Hanau

in the defile

formed by the Spessart

Hills and the river Main. Noailles blocked the outlet and had posts all around, but the allied troops forced their way through and inflicted heavy losses on the French, and the Battle of Dettingen

is justly reckoned as a notable victory of Anglo-Austrian-Hanovarian arms (27 June).

Broglie, worn out by age and exertions, was soon replaced by Marshal Coigny. Both Broglie and Noailles were now on the strict defensive behind the Rhine. Not a single French soldier remained in Germany, and Prince Charles prepared to force the passage of the great river in the Breisgau

while the King of Britain moved forward via Mainz to co-operate by drawing upon himself the attention of both the French marshals. The Anglo-allied army took Worms

, but after several unsuccessful attempts to cross, Prince Charles went into winter quarters. The king followed his example, drawing in his troops to the northward, to deal, if necessary, with the army which the French were collecting on the frontier of the Southern Netherlands

. Austria, Britain, Holland and Sardinia were now allied. Saxony changed sides, and Sweden and Russia neutralized each other (Peace of Åbo, August 1743). Frederick was still quiescent. France, Spain and Bavaria actively continued the struggle against Maria Theresa.

With 1744 began the Second Silesian War. Frederick of Prussia, disquieted by the universal success of the Austrians, secretly concluded a fresh alliance with Louis XV of France

With 1744 began the Second Silesian War. Frederick of Prussia, disquieted by the universal success of the Austrians, secretly concluded a fresh alliance with Louis XV of France

. France had posed hitherto as an auxiliary, its officers in Germany had worn the Bavarian cockade

, and only with Britain was it officially at war. France now declared war directly upon Austria and Sardinia (April 1744). An army was assembled at Dunkirk to support the cause of James Stuart

in an invasion of Great Britain

. However violent storms wrecked the crossing attempt, and the planned invasion was abandoned. Meanwhile, Louis XV in person, with 90,000 men, prepared to invade the Austrian Netherlands, and took Menin

and Ypres

. His presumed opponent was the allied army previously under King George II and now composed of British, Dutch, Germans and Austrians. On the Rhine, Coigny was up against Prince Charles, and a fresh army under the Prince de Conti

was to assist the Spaniards in Piedmont and Lombardy. This plan was, however, at once dislocated by the advance of Charles, who, assisted by the veteran marshal Traun, skillfully manoeuvred his army over the Rhine near Philippsburg

(1 July), captured the lines of Weissenburg

, and cut off Coigny from Alsace

. Coigny, however, cut his way through the enemy at Weissenburg and posted himself near Strasbourg

. Louis XV now abandoned the invasion of the Southern Netherlands

, and his army moved down to take a decisive part in the war in Alsace and Lorraine

. At the same time Frederick crossed the Austrian frontier (August).

The attention and resources of Austria were fully occupied, and the Prussians were almost unopposed. One column passed through Saxony, another through Lusatia

, while a third advanced from Silesia. Prague, the objective, was reached on 2 September. Six days later the Austrian garrison was compelled to surrender, and the Prussians advanced to Budweis. Maria Theresa once again rose to the emergency, a new "insurrection" took the field in Hungary, and a corps of regulars was assembled to cover Vienna, while the diplomats won over Saxony to the Austrian side. Prince Charles withdrew from Alsace, unmolested by the French, who had been thrown into confusion by the sudden and dangerous illness of Louis XV at Metz

. Only Seckendorf with the Bavarians pursued him. No move was made by the French, and Frederick thus found himself isolated and exposed to the combined attack of the Austrians and Saxons. Marshal Traun, summoned from the Rhine, held the king in check in Bohemia, the Hungarian irregulars inflicted numerous minor reverses on the Prussians, and finally Prince Charles arrived with the main army. The campaign resembled that of 1742: the Prussian retreat was closely watched, and the rearguard pressed hard. Prague fell, and Frederick, completely outmanoeuvred by the united forces of Prince Charles and Traun, retreated to Silesia with heavy losses. At the same time, the Austrians gained no foothold in Silesia itself. On the Rhine, Louis XV, now recovered, had besieged and taken Freiburg

, after which the forces left in the north were reinforced and besieged the strong places of Southern Netherlands

. There was also a slight war of manoeuvre on the middle Rhine.

The year 1745 saw three of the greatest battles of the war: Hohenfriedberg

The year 1745 saw three of the greatest battles of the war: Hohenfriedberg

, Kesselsdorf

and Fontenoy

. The first event of the year was the Quadruple Alliance

of Britain, Austria, Holland and Saxony, concluded at Warsaw

on 8 January 1745 (Treaty of Warsaw

). Twelve days later, the death of Charles VII submitted the imperial title to a new election, and his successor in Bavaria was not a candidate. The Bavarian army was again unfortunate. Caught in its scattered winter quarters (action of Amberg, 7 Jan.), it was driven from point to point, defeated at the Battle of Pfaffenhofen

and the young elector Maximilian III Joseph had to abandon Munich once more. The Peace of Füssen

followed on 22 April, by which he secured his hereditary states on condition of supporting the candidature of the Grand-Duke Francis, consort of Maria Theresa. The "imperial" army ceased ipso facto to exist, and Frederick was again isolated. No help was to be expected from France, whose efforts this year were centred on the Flanders campaign. Indeed, on 10 May, before Frederick took the field, Louis XV and the Marshal of France Maurice de Saxe had besieged Tournay

, and inflicted upon the relieving army of the Duke of Cumberland the great defeat of Fontenoy

.

In Silesia the customary small war had been going on for some time, and the concentration of the Prussian army was not effected without severe fighting. At the end of May, Frederick, with about 65,000 men, lay in the camp of Frankenstein

, between Glatz

and Neisse, while behind the Krkonoše (Giant Mountains) about Landeshut Prince Charles had 85,000 Austrians and Saxons. On 4 June was fought the Battle of Hohenfriedberg

or Striegau, the greatest victory as yet of Frederick's career, and, of all his battles, excelled perhaps by Leuthen

and Rossbach

only. Prince Charles suffered a complete defeat and withdrew through the mountains as he had come. Frederick's pursuit was methodical, for the country was difficult and barren, and he did not know the extent to which the enemy was demoralised.

The manoeuvres of both leaders on the upper Elbe occupied all the summer, while the political questions of the imperial election and of an understanding between Prussia and Britain were pending. The chief efforts of Austria were directed towards the valleys of the Main and Lahn

and Frankfurt

, where the French and Austrian armies manoeuvred for a position from which to overawe the electoral body. Marshal Traun was successful, and Francis was elected Holy Roman Emperor on 13 September. Frederick agreed with Britain to recognise the election a few days later, but Maria Theresa would not conform to the Treaty of Breslau without a further appeal to the fortune of war. Saxony joined in this last attempt. A new advance of Prince Charles quickly brought on the Battle of Soor

, fought on ground destined to be famous in the war of 1866

. Frederick was at first in a position of great peril, but his army changed front in the face of the advancing enemy and by its boldness and tenacity won a remarkable victory (30 Sept.).

But the campaign was not ended. An Austrian contingent from the Main joined the Saxons under Field Marshal Rutowsky (1702–1764), and a combined movement was made in the direction of Berlin by Rutowsky from Saxony and Prince Charles from Bohemia. The danger was very great. Frederick hurried up his forces from Silesia and marched as rapidly as possible on Dresden

, winning the actions of Katholisch-Hennersdorf (24 Nov.) and Görlitz

(25 Nov.). Prince Charles was thereby forced back, and now a second Prussian army under the Old Dessauer

advanced up the Elbe from Magdeburg

to meet Rutowsky. The latter took up a strong position at Kesselsdorf

between Meissen

and Dresden

, but the veteran Leopold attacked him directly and without hesitation (14 Dec.). The Saxons and their allies were completely rout

ed after a hard struggle, and Maria Theresa at last gave way. In the Peace of Dresden

(25 Dec.) Frederick recognized the imperial election, and retained Silesia, as at the Peace of Breslau.

In central Italy

In central Italy

an army of Spaniards and Neapolitans

was collected for the purpose of conquering the Milan

ese. In 1741, the allied Spaniards and Neapolitans had advanced towards Modena

, the Duke of which state had allied himself with them, but the vigilant Austrian commander, Count Otto Ferdinand von Traun had out-marched them, captured Modena and forced the Duke to make a separate peace.

In 1742, Traun held his own with ease against the Spanish and Neapolitans. Naples was forced by a British Squadron

to withdraw her troops for home defence, and Spain, now too weak to advance in the Po valley

, sent a second army to Italy via France. Sardinia had allied herself with Austria in the Convention of Turin

and at the same time neither state was at war with France and this led to curious complications, combats being fought in the Isère valley between the troops of Sardinia and of Spain, in which the French took no part.

In 1743, the Spanish on the Panaro

had achieved a victory over Traun at Campo Santo

(8 February 1743), but the next six months were wasted in inaction and Georg Christian, Fürst von Lobkowitz

, joining Traun with reinforcements from Germany, drove back the enemy to Rimini

. Observing from Venice

, Rousseau

hailed the Spanish retreat as "the finest military manoeuvre of the whole century." The Spanish-Piedmont

ese War in the Alps

continued without much result, the only incident of note being the first Battle of Casteldelfino (7–10 October 1743), when an initial French offensive was beaten off.

In 1744 the Italian war became serious. A grandiose plan of campaign was formed and the Spanish and French generals at the front were hampered by the orders of their respective governments. The object was to unite the army in Dauphiné

with that on the lower Po. The support of Genoa

allowed a road into central Italy. But Lobkowitz had already taken the offensive and driven back the Spanish army of the Count de Gages towards the Neapolitan frontier, so the King of Naples

(the future Charles III of Spain

) had to assist the Spaniards. A combined army was formed at the Battle of Velletri (1744) and defeated Lobkowitz there on 11 August. The crisis past, Lobkowitz then went to Piedmont to assist the king against the Prince of Conti

, the King of Naples returned home and the Count de Gages followed the Austrians with a weak force.

The war in the Alps and the Apennines

had already been keenly contested. Villefranche and Montalban

were stormed by Conti on 20 April, a desperate fight took place at Peyre-Longue on 18 July (second Battle of Casteldelfino

) and the King of Sardinia

was defeated in a great Battle at Madonna dell'Olmo

(30 September) near Coni (Cuneo

). Conti did not, however, succeed in taking this fortress and had to retire into Dauphiné for his winter quarters. The two armies had, therefore, failed in their attempt to combine and the Austro-Sardinians still lay between them.

The campaign in Italy this year was also no mere war of posts. In March 1745 a secret treaty allied the Genoese Republic

with France, Spain and Naples. A change in the command of the Austrians favoured the first move of the allies. De Gages moved from Modena towards Lucca

, the Spaniards and French in the Alps under Marshal Maillebois

advanced through the Italian Riviera

to the Tanaro

and in the middle of July the two armies were at last concentrated between the Scrivia

and the Tanaro, to the unusually large number of 80,000. A swift march on Piacenza

drew the Austrian commander thither and in his absence the allies fell upon and completely defeated the Sardinians at Bassignano

(27 September), a victory which was quickly followed by the capture of Alessandria

, Valenza

and Casale Monferrato

. Jomini calls the concentration of forces which effected the victory "Le plus remarquable de toute la Guerre".

The complicated politics of Italy, however, brought it about that Maillebois was ultimately unable to turn his victory to account. Indeed, early in 1746, Austrian troops, freed by the peace with Frederick, passed through the Tyrol

The complicated politics of Italy, however, brought it about that Maillebois was ultimately unable to turn his victory to account. Indeed, early in 1746, Austrian troops, freed by the peace with Frederick, passed through the Tyrol

into Italy. The Franco-Spanish winter quarters were brusquely attacked and a French garrison of 6,000 men at Asti

was forced to capitulate. At the same time Maximilian Ulysses Count Browne with an Austrian corps struck at the allies on the Lower Po, and cut off their communication with the main body in Piedmont. A series of minor actions thus completely destroyed the great concentration. The allies separated, Maillebois covering Liguria

, the Spaniards marching against Browne. The latter was promptly and heavily reinforced and all that the Spaniards could do was to entrench themselves at Piacenza, Philip, the Spanish Infante as supreme commander calling up Maillebois to his aid. The French, skillfully conducted and marching rapidly, joined forces once more, but their situation was critical, for only two marches behind them the army of the King of Sardinia was in pursuit, and before them lay the principal army of the Austrians. The pitched Battle of Piacenza

(16 June) was hard fought and Maillebois had nearly achieved a victory when orders from the Infante compelled him to retire. That the army escaped at all was in the highest degree creditable to Maillebois and to his son and chief of staff, under whose leadership it eluded both the Austrians and the Sardinians, defeated an Austrian corps in the Battle of Rottofreddo

(12 August), and made good its retreat on Genoa.

It was, however, a mere remnant of the allied army which returned, and the Austrians were soon masters of north Italy, including the Republic of Genoa

(September). But they met with no success in their forays towards the Alps. Soon Genoa revolted from the oppressive rule of the victors, rose and drove out the Austrians (5–11 December) as an Allied invasion of Provence

stalled, and the French, now commanded by Charles Louis Auguste Fouquet, Duc de Belle-Isle, took the offensive (1747). Genoa held out against a second Austrian siege and after the plan of campaign had as usual been referred to Paris and Madrid, it was relieved, though a picked corps of the French army under the Chevalier de Belle-Isle (1684–1747), brother of the marshal, was defeated in the almost impossible attempt (10 July) to storm the entrenched pass of Exilles

(Colle dell'Assietta

), the chevalier, and with him much of the elite of the French nobility, being killed at the barricades. Before the steady advance of Marshal Belle-Isle the Austrians retired into Lombardy

and a desultory campaign was waged up to the conclusion of peace.

in February 1746. In September the British launched a Raid on Lorient

in an attempt to provide a diversion for the Allied forces in the Netherlands. The Battle of Roucoux (or Raucourt) near Liège, fought on 11 October between the allies under Prince Charles of Lorraine and the French under Saxe, resulted in a victory for the latter. Holland itself was now in danger, and when in April 1747 Saxe's army, which had now conquered the Austrian Netherlands up to the Meuse, turned its attention to the United Provinces

. The old fortresses on the frontier offered but slight resistance. Since August 1746 talks had been ongoing at the Congress of Breda

to try and agree a peace settlement, but up to this point they had met with little success.

The Prince of Orange William IV

and the Duke of Cumberland suffered a severe defeat at Lauffeld

(Lawfeld, also called Val) on 2 July 1747, and Saxe, after his victory, promptly and secretly despatched a corps under Marshal Lowendahl (1700–1755) to besiege Bergen op Zoom

. On 18 September Bergen op Zoom was stormed by the French

, and in the last year of the war Maastricht

, attacked by the entire forces of Saxe and Lowendahl, surrendered on 7 May 1748

. A large Russian army arrived to join the allies, but too late to be of use. The quarrel of Russia and Sweden had been settled by the Peace of Åbo in 1743, and in 1746 Russia had allied herself with Austria. Eventually a large army marched from Moscow to the Rhine, an event which was not without military significance, and in a manner preluded the great invasions of 1813–1814 and 1815. The general Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen

) was signed on 18 October 1748.

. Maria Theresa and Austria survived status quo ante bellum

, sacrificing only the territory of Silesia, which Austria conceded to Prussia. The end of the war also sparked the beginning of the German dualism

between Prussia and Austria, which would ultimately fuel German nationalism and the drive to unify Germany as a single entity.

Despite his victories, Louis XV of France, who wanted to appear as an arbiter and not as a conqueror, gave all his conquests back to the defeated enemies with chivalry, arguing that he was "king of France, not a shopkeeper." This decision, largely misunderstood by his generals and by the French people, made the king unpopular. The French obtained so little of what they fought for that they adopted the expressions Bête comme la paix ("Stupid as peace") and Travailler pour le roi de Prusse ("To work for the king of Prussia", i.e. working for nothing). However his generosity was saluted in Europe and France increased its political influence on the continent.

The war, like other conflicts of the time, featured an extraordinary disparity between the end and the means. The political schemes to be executed by the French and other armies were as grandiose as any of modern times. Their execution, under the then conditions of time and space, invariably fell short of expectations, and the history of the war proves, as that of the Seven Years' War

was to prove, that the small standing army of the 18th century could conquer by degrees, but could not deliver a decisive blow. Frederick alone, with a definite end and proportionate means to achieve it, succeeded completely. Even less was to be expected when the armies were composed of allied contingents, sent to the war each for a different object. The allied national armies of 1813 (at the Battle of Leipzig

) co-operated loyally, for they had much at stake and worked for a common object. Those of 1741 represented the divergent private interests of the several dynasties, and achieved nothing.

as King George's War

, and did not begin until after formal war declarations of France and Britain reached the colonies in May 1744. The frontiers between New France

and the British colonies of New England

, New York

, and Nova Scotia

were the site of frequent small scale raids, primarily by French colonial troops and their Indian allies against British targets, although several attempts were made by British colonists to organize expeditions against New France. The most significant incident was the capture

of the French Fortress Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island

(Île Royale) by an expedition (29 April – 16 June 1745) of colonial militia organized by Massachusetts

Governor William Shirley

, commanded by William Pepperrell

of Maine

(then part of Massachusetts), and assisted by a Royal Navy fleet. A French expedition

to recover Louisbourg in 1746 failed due to bad weather, disease, and the death of its commander. Louisbourg was returned to France in exchange for Madras, generating much anger among the British colonists, who felt they had eliminated a nest of privateers with its capture.

.svg.png) The war marked the beginning of the power struggle between Britain and France in India and of European military ascendancy and political intervention in the subcontinent. Major hostilities began with the arrival of a naval squadron under Mahé de la Bourdonnais

The war marked the beginning of the power struggle between Britain and France in India and of European military ascendancy and political intervention in the subcontinent. Major hostilities began with the arrival of a naval squadron under Mahé de la Bourdonnais

, carrying troops from France. In September 1746 Bourdonnais landed his troops near Madras

and laid siege to the port. Although it was the main British settlement in the Carnatic

, Madras was weakly fortified and had only a small garrison, reflecting the thoroughly commercial nature of the European presence in India hitherto. On 10 September, only six days after the arrival of the French force, Madras surrendered. The terms of the surrender agreed by Bourdonnais provided for the settlement to be ransomed back for a cash payment by the British East India Company

. However, this concession was opposed by Dupleix

, the governor general of the Indian possessions of the Compagnie des Indes

. When Bourdonnais was forced to leave India in October after the devastation of his squadron by a cyclone Dupleix reneged on the agreement. The Nawab of the Carnatic

Anwaruddin Muhammed Khan

intervened in support of the British and advanced to retake Madras, but despite vast superiority in numbers his army was easily and bloodily crushed by the French, in the first demonstration of the gap in quality that had opened up between European and Indian armies.

The French now turned to the remaining British settlement in the Carnatic, Fort St David

at Cuddalore

, which was dangerously close to the main French settlement of Pondicherry. The first French force sent against Cuddalore was surprised and defeated nearby by the forces of the Nawab and the British garrison in December 1746. Early in 1747 a second expedition laid siege to Fort St David but withdrew on the arrival of a British naval squadron in March. A final attempt in June 1748 avoided the fort and attacked the weakly fortified town of Cuddalore itself, but was routed by the British garrison.

With the arrival of a naval squadron under Admiral Boscawen

, carrying troops and artillery, the British went on the offensive, laying siege to Pondicherry. They enjoyed a considerable superiority in numbers over the defenders, but the settlement had been heavily fortified by Dupleix and after two months the siege was abandoned.

The peace settlement brought the return of Madras to the British company, exchanged for Louisbourg in Canada. However, the conflict between the two companies continued by proxy during the interval before the outbreak of the Seven Years War, with British and French forces fighting on behalf of rival claimants to the thrones of Hyderabad

and the Carnatic

.

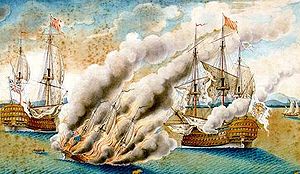

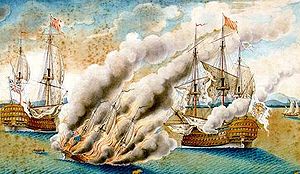

, which broke out in 1739 in consequence of the long disputes between Britain and Spain over their conflicting claims in America. The British navy was at its lowest point of energy and efficiency after the long administration of Sir Robert Walpole

, while the French and Spanish were even weaker and the naval struggle produced little in the way of concrete results.

The war was remarkable for the prominence of privateering on both sides. It was carried on by the Spaniards in the West Indies with great success, and actively at home. The French were no less active in all seas. Mahé de la Bourdonnais's attack on Madras partook largely of the nature of a privateering venture. The British retaliated with vigour. The total number of captures by French and Spanish corsair

s was in all probability larger than the list of British – as the French wit Voltaire

drolly put it upon hearing his government's boast, namely, that more British merchants were taken because there were many more British merchant ships to take; but partly also because the British government had not yet begun to enforce the use of convoy

so strictly as it did in later times.

War on Spain was declared by Great Britain on 23 October 1739, which has become known as the War of Jenkins' Ear

War on Spain was declared by Great Britain on 23 October 1739, which has become known as the War of Jenkins' Ear

. A plan was laid for combined operations against the Spanish colonies from east and west. One force, military and naval, was to assault them from the West Indies under Admiral Edward Vernon

. Another, to be commanded by Commodore George Anson

, afterwards Lord Anson, was to round Cape Horn

and to fall upon the Pacific coast of Latin America. Delays, bad preparations, dockyard corruption, and the squabbles of the naval and military officers concerned caused the failure of a hopeful scheme. On 21 November 1739 Admiral Vernon did however succeed in capturing the ill-defended Spanish harbour of Porto Bello in present-day Panama

. When Vernon had been joined by Sir Chaloner Ogle

with naval reinforcements and a strong body of troops, an attack was made on Cartagena

in what is now Colombia

(9 March – 24 April 1741). The delay had given the Spanish admiral, Don Blas de Lezo

(1687–1741), time to prepare, and the siege failed with a dreadful loss of life to the assailants mostly due to disease.

The war in the West Indies, after two other unsuccessful attacks had been made on Spanish territory, died down and did not revive till 1748. The expedition under Anson sailed late, was very ill-provided, and less strong than had been intended. It consisted of six ships and left Britain on 18 September 1740. Anson returned alone with his flagship

the Centurion

on 15 June 1744. The other vessels had either failed to round the Horn or had been lost. But Anson had harried the coast of Chile

and Peru

and had captured a Spanish galleon of immense value near the Philippines

. His cruise was a great feat of resolution and endurance.

The last naval operations of the war took place in the West Indies, where the Spaniards, who had for a time been treated as a negligible quantity, were attacked on the coast of Cuba

by a British squadron under Sir Charles Knowles. They had a naval force under Admiral Reggio

at Havana

. Each side was at once anxious to cover its own trade, and to intercept that of the other. Capture was rendered particularly desirable to the British by the fact that the Spanish homeward-bound convoy would be laden with the bullion sent from the American mines. In the course of the movement of each to protect its trade, the two squadrons met on 1 October 1748 in the Bahama Channel

. The action was indecisive when compared with the successes of British fleets in later days, but the advantage lay with Sir Charles Knowles. He was prevented from following it up by the speedy receipt of the news that peace had been made in Europe by the powers, who were all in various degrees exhausted.

While Anson was pursuing his voyage round the world

While Anson was pursuing his voyage round the world

, Spain was mainly intent on the Italian policy of the king. A squadron was fitted out at Cádiz

to convey troops to Italy. It was watched by the British admiral Nicholas Haddock

. When the blockading squadron was forced off by want of provisions, the Spanish admiral Don Juan José Navarro

put to sea. He was followed, but when the British force came in sight of him Navarro had been joined by a French squadron under Claude-Elisée de La Bruyère de Court (December 1741). The French admiral announced that he would support the Spaniards if they were attacked and Haddock retired. France and Great Britain were not yet openly at war, but both were engaged in the struggle in Germany—Great Britain as the ally of the Queen of Hungary, Maria Theresa; France as the supporter of the Bavarian claimant of the empire. Navarro and de Court went on to Toulon

, where they remained till February 1744. A British fleet watched them, under the command of Admiral Richard Lestock

, till Sir Thomas Mathews

was sent out as commander-in-chief and as Minister to the Court of Turin

.

Sporadic manifestations of hostility between the French and British took place in different seas, but avowed war did not begin till the French government issued its declaration of 30 March, to which Great Britain replied on 31 March. This formality had been preceded by French preparations for the invasion of England, and by the Battle of Toulon between the British and a Franco-Spanish fleet. On 11 February a most confused battle was fought, in which the van and centre of the British fleet was engaged with the Spanish rear and centre of the allies. Lestock, who was on the worst possible terms with his superior, took no part in the action. Mathews fought with spirit but in a disorderly way, breaking the formation of his fleet, and showing no power of direction. The mismanagement of the British fleet in the battle, by arousing deep anger among the people, led to a drastic reform of the British navy which bore its first fruits before the war ended.

leaders, and soldiers were to be transported from Dunkirk. In February 1744, a French fleet of twenty sail of the line entered the English Channel

under Jacques Aymar, comte de Roquefeuil

, before the British force under Admiral John Norris was ready to oppose him. But the French force was ill-equipped, the admiral was nervous, his mind dwelt on all the misfortunes which might possibly happen, and the weather was bad. De Roquefeuil came up almost as far as The Downs

, where he learnt that Sir John Norris was at hand with twenty-five sail of the line, and thereupon precipitately retreated. The military expedition prepared at Dunkirk to cross under cover of De Roquefeuil's fleet naturally did not start. The utter weakness of the French at sea, due to long neglect of the fleet and the bankrupt state of the treasury, was shown during the Jacobite rising of 1745, when France made no attempt to profit by the distress of the British government.

The Dutch, having by this time joined Great Britain, made a serious addition to the naval power opposed to France, though Holland was compelled by the necessity for maintaining an army in Flanders to play a very subordinate part at sea. Not being stimulated by formidable attack, and having immediate interests both at home and in Germany, the British government was slow to make use of its latest naval strength. Spain, which could do nothing of an offensive character, was almost neglected. During 1745 the New England

expedition which took Louisburg (30 April – June 16) was covered by a British naval force, but little else was accomplished by the naval efforts of any of the belligerents.

In 1746 a British combined naval and military expedition to the coast of France – the first of a long series of similar ventures which in the end were derided as "breaking windows with guineas" – was carried out during August and October. The aim was the capture of the French East India Company

's dockyard at L'Orient, but it was not attained.

From 1747 until the close of the war in October 1748 the naval policy of the British government, without reaching a high level, was more energetic and coherent. A closer watch was kept on the French coast, and effectual means were taken to intercept communication between France and her American possessions. In the spring information was obtained that an important convoy for the East and West Indies

was to sail from L'Orient. The convoy was intercepted by Anson on 3 May, and in the first Battle of Cape Finisterre

his fourteen ships of the line wiped out the French escort of six ships of the line and three armed Indiamen, although in the meantime the merchant ships escaped.

On 14 October another French convoy, protected by a strong squadron, was intercepted by a well-appointed and well-directed squadron of superior numbers – the squadrons were respectively eight French and fourteen British – in the Bay of Biscay

. In the second Battle of Cape Finisterre

which followed, the French admiral, Henri-François des Herbiers-l'Étenduère (1681–1750), succeeded in covering the escape of most of the merchant ships, but Hawke's British squadron took six of his warships. Most of the merchantmen were later intercepted and captured in the West Indies. This disaster convinced the French government of its helplessness at sea, and it made no further effort.

. After an inconclusive clash off Negapatnam in June 1746, Edward Peyton

, Barnett's successor, withdrew to Bengal, leaving Bourdonnais unopposed on the Coromandel Coast

. He landed troops near Madras

and besieged the port by land and sea, forcing it to surrender on 10 September 1746. In October the French squadron was devastated by a cyclone, losing four ships of the line and suffering heavy damage to four more, and the surviving ships withdrew. French land forces went on to besiege the British settlement at Cuddalore

, but the eventual replacement of the negligent Peyton by Thomas Griffin resulted in the British squadron's belated return to action and the raising of the siege in March 1747. Despite the appearance of another French squadron, the arrival of British reinforcements under Edward Boscawen

gave the British overwhelming dominance at sea, but the ensuing siege of Pondicherry organised by Bosccawen was unsuccessful.

King George's War

King George's War is the name given to the operations in North America that formed part of the War of the Austrian Succession . It was the third of the four French and Indian Wars. It took place primarily in the British provinces of New York, Massachusetts Bay, New Hampshire, and Nova Scotia...

in North America, the Anglo-Spanish

Anglo-Spanish War

Anglo-Spanish War may refer to:* The Anglo-Spanish War of 1585–1604 was part of the Eighty Years' War* The Anglo-Spanish War of 1625–1630 was part of the Thirty Years' War...

War of Jenkins' Ear

War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear was a conflict between Great Britain and Spain that lasted from 1739 to 1748, with major operations largely ended by 1742. Its unusual name, coined by Thomas Carlyle in 1858, relates to Robert Jenkins, captain of a British merchant ship, who exhibited his severed ear in...

, and two of the three Silesian wars

Silesian Wars

The Silesian Wars were a series of wars between Prussia and Austria for control of Silesia. They formed parts of the larger War of the Austrian Succession and Seven Years' War. They eventually ended with Silesia being incorporated into Prussia, and Austrian recognition of this...

– involved most of the powers

Power in international relations

Power in international relations is defined in several different ways. Political scientists, historians, and practitioners of international relations have used the following concepts of political power:...

of Europe over the question of Maria Theresa's

Maria Theresa of Austria

Maria Theresa Walburga Amalia Christina was the only female ruler of the Habsburg dominions and the last of the House of Habsburg. She was the sovereign of Austria, Hungary, Croatia, Bohemia, Mantua, Milan, Lodomeria and Galicia, the Austrian Netherlands and Parma...

succession to the realms of the House of Habsburg.

The war began under the pretext that Maria Theresa was ineligible to succeed to the Habsburg thrones of her father, Charles VI

Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles VI was the penultimate Habsburg sovereign of the Habsburg Empire. He succeeded his elder brother, Joseph I, as Holy Roman Emperor, King of Bohemia , Hungary and Croatia , Archduke of Austria, etc., in 1711...

, because Salic law

Salic law

Salic law was a body of traditional law codified for governing the Salian Franks in the early Middle Ages during the reign of King Clovis I in the 6th century...

precluded royal inheritance by a woman—though in reality this was a convenient excuse put forward by Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

and France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

to challenge Habsburg power. Austria was supported by Great Britain

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

and the Dutch Republic

Dutch Republic

The Dutch Republic — officially known as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands , the Republic of the United Netherlands, or the Republic of the Seven United Provinces — was a republic in Europe existing from 1581 to 1795, preceding the Batavian Republic and ultimately...

, the traditional enemies of France, as well as the Kingdom of Sardinia

Kingdom of Sardinia

The Kingdom of Sardinia consisted of the island of Sardinia first as a part of the Crown of Aragon and subsequently the Spanish Empire , and second as a part of the composite state of the House of Savoy . Its capital was originally Cagliari, in the south of the island, and later Turin, on the...

and Saxony

Electorate of Saxony

The Electorate of Saxony , sometimes referred to as Upper Saxony, was a State of the Holy Roman Empire. It was established when Emperor Charles IV raised the Ascanian duchy of Saxe-Wittenberg to the status of an Electorate by the Golden Bull of 1356...

. France and Prussia were allied with the Electorate of Bavaria

Electorate of Bavaria

The Electorate of Bavaria was an independent hereditary electorate of the Holy Roman Empire from 1623 to 1806, when it was succeeded by the Kingdom of Bavaria....

.

Spain entered the war to reestablish its influence in northern Italy, further reversing an Austrian dominance over the Italian peninsula that had been achieved at Spain's expense as a consequence of that country's own war of succession

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was fought among several European powers, including a divided Spain, over the possible unification of the Kingdoms of Spain and France under one Bourbon monarch. As France and Spain were among the most powerful states of Europe, such a unification would have...

earlier in the 18th century.

The war ended with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle

Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle (1748)

The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle of 1748 ended the War of the Austrian Succession following a congress assembled at the Imperial Free City of Aachen—Aix-la-Chapelle in French—in the west of the Holy Roman Empire, on 24 April 1748...

in 1748. The most enduring military historical interest and importance of the war lies in the struggle of Prussia

Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia was a German kingdom from 1701 to 1918. Until the defeat of Germany in World War I, it comprised almost two-thirds of the area of the German Empire...

and the Habsburg

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg , also found as Hapsburg, and also known as House of Austria is one of the most important royal houses of Europe and is best known for being an origin of all of the formally elected Holy Roman Emperors between 1438 and 1740, as well as rulers of the Austrian Empire and...

monarchs for the region of Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

.

Background

Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles VI was the penultimate Habsburg sovereign of the Habsburg Empire. He succeeded his elder brother, Joseph I, as Holy Roman Emperor, King of Bohemia , Hungary and Croatia , Archduke of Austria, etc., in 1711...

, Maria Theresa succeeded him as Queen of Hungary, Croatia

Kingdom of Croatia (Habsburg)

The Kingdom of Croatia was an administrative division that existed between 1527 and 1868 within the Habsburg Monarchy . The Kingdom was a part of the Lands of the Crown of St. Stephen, but was subject to direct Imperial Austrian rule for significant periods of time, including its final years...

and Bohemia, Archduchess of Austria and Duchess of Parma. Her father had been Holy Roman Emperor, but Maria Theresa was not a candidate for that title, which had never been held by a woman; the plan was for her to succeed to the hereditary domains, and her husband, Francis Stephen

Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor

Francis I was Holy Roman Emperor and Grand Duke of Tuscany, though his wife effectively executed the real power of those positions. With his wife, Maria Theresa, he was the founder of the Habsburg-Lorraine dynasty...

, to be elected Holy Roman Emperor. The complications involved in a female Habsburg ruler had been long foreseen, and Charles VI had persuaded most of the states of Germany to agree to the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713

Pragmatic Sanction of 1713

The Pragmatic Sanction of 1713 was an edict issued by Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI to ensure that the throne of the Archduchy of Austria could be inherited by a daughter....

.

Problems began when King Frederick II of Prussia

Frederick II of Prussia

Frederick II was a King in Prussia and a King of Prussia from the Hohenzollern dynasty. In his role as a prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire, he was also Elector of Brandenburg. He was in personal union the sovereign prince of the Principality of Neuchâtel...

violated the Pragmatic Sanction and invaded Silesia

Silesia

Silesia is a historical region of Central Europe located mostly in Poland, with smaller parts also in the Czech Republic, and Germany.Silesia is rich in mineral and natural resources, and includes several important industrial areas. Silesia's largest city and historical capital is Wrocław...

on 16 December 1740, using the Treaty of Brieg of 1537 under which the Hohenzollerns

House of Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern is a noble family and royal dynasty of electors, kings and emperors of Prussia, Germany and Romania. It originated in the area around the town of Hechingen in Swabia during the 11th century. They took their name from their ancestral home, the Burg Hohenzollern castle near...

of Brandenburg

Brandenburg

Brandenburg is one of the sixteen federal-states of Germany. It lies in the east of the country and is one of the new federal states that were re-created in 1990 upon the reunification of the former West Germany and East Germany. The capital is Potsdam...

were to inherit the Duchy of Brieg as a pretext. Maria Theresa, as a woman, was perceived as weak, and other rulers (such as Charles Albert of Bavaria

Charles VII, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles VII Albert a member of the Wittelsbach family, was Prince-elector of Bavaria from 1726 and Holy Roman Emperor from 24 January 1742 until his death in 1745...

) put forward their own competing claims to the crown

Order of succession

An order of succession is a formula or algorithm that determines who inherits an office upon the death, resignation, or removal of its current occupant.-Monarchies and nobility:...

as male heirs with a clear genealogical basis to inherit the elected dignities

Prince-elector

The Prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire were the members of the electoral college of the Holy Roman Empire, having the function of electing the Roman king or, from the middle of the 16th century onwards, directly the Holy Roman Emperor.The heir-apparent to a prince-elector was known as an...

of the great Imperial title.

Silesian Campaign of 1740

Prussia in 1740 was a small and thoroughly organized emerging international power

Power in international relations

Power in international relations is defined in several different ways. Political scientists, historians, and practitioners of international relations have used the following concepts of political power:...

with a brand new well educated king, Frederick II of Prussia

Frederick II of Prussia

Frederick II was a King in Prussia and a King of Prussia from the Hohenzollern dynasty. In his role as a prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire, he was also Elector of Brandenburg. He was in personal union the sovereign prince of the Principality of Neuchâtel...

, desiring to unify the disparate and scattered crown holdings by gathering intervening lands into a unified contiguous state. When the Holy Roman Emperor died, distracting the Habsburg Monarchy to the south east, Frederick turned opportunist using a questionable interpretation of a treaty (1537) between the Hohenzollerns and the Piasts of Brieg as pretext (reversing Prussia's position in the War of the Polish Succession

War of the Polish Succession

The War of the Polish Succession was a major European war for princes' possessions sparked by a Polish civil war over the succession to Augustus II, King of Poland that other European powers widened in pursuit of their own national interests...

, concluded the year 1738, just two years before) to invade and snap up territories in Silesia. Meanwhile, as expected, the other princes of Europe prepared to exploit an opportunity to acquire Habsburg possessions and humble and diminish the power of the great house that an election of the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire

Prince-elector

The Prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire were the members of the electoral college of the Holy Roman Empire, having the function of electing the Roman king or, from the middle of the 16th century onwards, directly the Holy Roman Emperor.The heir-apparent to a prince-elector was known as an...

represented. Archduchess of Austria and Queen of Hungary she may be, but salic law

Salic law

Salic law was a body of traditional law codified for governing the Salian Franks in the early Middle Ages during the reign of King Clovis I in the 6th century...

guaranteed the next Emperor was not going to be Archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria.

While the only recent war experience of its army had been in the War of the Polish Succession

War of the Polish Succession

The War of the Polish Succession was a major European war for princes' possessions sparked by a Polish civil war over the succession to Augustus II, King of Poland that other European powers widened in pursuit of their own national interests...

(Rhine campaign of 1733–1735) her forces hadn't fought there, since Frederick William was not trusted by Austria. It therefore had an uninspiring reputation and was counted as one of the many minor armies of the princes of Europe, of which there were plenty (See the 1800 plus states of the Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

).

Only few thought that it could rival the larger modern forces of Austria and France. But King Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia had drilled it to a perfection previously unknown in Europe's military experience, and the Prussian infantry

Infantry

Infantrymen are soldiers who are specifically trained for the role of fighting on foot to engage the enemy face to face and have historically borne the brunt of the casualties of combat in wars. As the oldest branch of combat arms, they are the backbone of armies...

soldier was so well-trained and well-equipped that he could fire 3 shots a minute to an Austrian's 1.Prussian cavalry

Cavalry

Cavalry or horsemen were soldiers or warriors who fought mounted on horseback. Cavalry were historically the third oldest and the most mobile of the combat arms...

and artillery

Artillery

Originally applied to any group of infantry primarily armed with projectile weapons, artillery has over time become limited in meaning to refer only to those engines of war that operate by projection of munitions far beyond the range of effect of personal weapons...

were comparatively less efficient, but they were still of better quality than average.

The initial advantage of Frederick's army was that, undisturbed by wars, it had developed the professional standing-army

Standing army

A standing army is a professional permanent army. It is composed of full-time career soldiers and is not disbanded during times of peace. It differs from army reserves, who are activated only during wars or natural disasters...

concept to full maturity and effect. While the Austrians had to wait for conscription to complete the field forces, Prussian regiments took the field at once, and thus Frederick was able to overrun Silesia almost unopposed.

In any event, his army had massed quietly along the Oder River during early December, and on 16 December 1740, without declaration of war, it crossed the frontier into Silesia. The extant forces available to the local Austrian generals could do no more than garrison

Garrison

Garrison is the collective term for a body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it, but now often simply using it as a home base....

a few fortresses

Fortification

Fortifications are military constructions and buildings designed for defence in warfare and military bases. Humans have constructed defensive works for many thousands of years, in a variety of increasingly complex designs...

, and they necessarily fell back to the mountain frontier of Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

and Moravia

Moravia

Moravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

with only a small remnant of their available forces left in the garrisons.

On their new territory, the organized Prussian army was soon able to go into winter quarters, holding all Silesia and investing the strong places of Glogau, Brieg

Brzeg

Brzeg is a town in southwestern Poland with 38,496 inhabitants , situated in Silesia in the Opole Voivodeship on the left bank of the Oder...

and Neisse

Nysa, Poland

Nysa is a town in southwestern Poland on the Nysa Kłodzka river with 47,545 inhabitants , situated in the Opole Voivodeship. It is the capital of Nysa County. It comprises the urban portion of the surrounding Gmina Nysa, a mixed urban-rural commune with a total population of 60,123 inhabitants...

. In one step, Prussia had effectively doubled its population and made huge gains in its industrial productivity for the minor cost of fair treatment of the people in the occupied territory—an atypical factor and effect in a day when relatively undisciplined mercenary

Mercenary

A mercenary, is a person who takes part in an armed conflict based on the promise of material compensation rather than having a direct interest in, or a legal obligation to, the conflict itself. A non-conscript professional member of a regular army is not considered to be a mercenary although he...

forces were the rule rather than the exception with their habitual raping, looting, and abuse of the various populations around themselves – which were generally forced to provide quarters.

Nationalism as we know it today, was not a factor, but an evolving concept just coming into its early years. Prussia benefited greatly from the apolitical nature of the society of the era, as the masses in central Germany would correspondingly suffer as the contending armies rampaged through their plains yet again.

Allies in Bohemia 1741

The French duly joined the Bavarian Elector's forces on the DanubeDanube

The Danube is a river in the Central Europe and the Europe's second longest river after the Volga. It is classified as an international waterway....

and advanced towards Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

, but the objective was suddenly changed, and after many countermarches the anti-Austrian allies advanced, in three widely separated corps

Corps

A corps is either a large formation, or an administrative grouping of troops within an armed force with a common function such as Artillery or Signals representing an arm of service...

, on Prague

Prague

Prague is the capital and largest city of the Czech Republic. Situated in the north-west of the country on the Vltava river, the city is home to about 1.3 million people, while its metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of over 2.3 million...

. A French corps moved via Amberg

Amberg

Amberg is a town in Bavaria, Germany. It is located in the Upper Palatinate, roughly halfway between Regensburg and Bayreuth. Population: 44,756 .- History :...

and Pilsen. The Elector marched on Budweis, and the Saxons (who had now joined the allies) invaded Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

by the Elbe

Elbe

The Elbe is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Krkonoše Mountains of the northwestern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia , then Germany and flowing into the North Sea at Cuxhaven, 110 km northwest of Hamburg...

valley. The Austrians could at first offer little resistance, but before long a considerable force intervened at Tábor

Tábor

Tábor is a city of the Czech Republic, in the South Bohemian Region. It is named after Mount Tabor, which is believed by many to be the place of the Transfiguration of Christ; however, the name became popular and nowadays translates to "camp" or "encampment" in the Czech language.The town was...

between the Danube and the allies, and the Austrian general Wilhelm Reinhard von Neipperg

Wilhelm Reinhard von Neipperg

Count Wilhelm Reinhard von Neipperg was an Austrian general.Born in Schwaigern, he descended from an ancient comital family from Swabia, his father Count Eberhard Friedrich von Neipperg having been an Imperial field marshal. He spent his boyhood in Vienna and in 1702 joined the Imperial service...

was now on the march from Neisse to join in the campaign

Military campaign

In the military sciences, the term military campaign applies to large scale, long duration, significant military strategy plan incorporating a series of inter-related military operations or battles forming a distinct part of a larger conflict often called a war...

. He had made with Frederick the curious agreement of Klein Schnellendorf (9 October 1741), by which Neisse was surrendered after a mock siege, and the Austrians undertook to leave Frederick unmolested in return for his releasing Neipperg's army for service elsewhere. At the same time the Hungarians

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

, moved to enthusiasm by the personal appeal of Maria Theresia, had put into the field a levée en masse, or "insurrection," which furnished the regular army with an invaluable force of light troops. A fresh army was collected under Field Marshal Khevenhüller at Vienna, and the Austrians planned an offensive winter campaign against the Franco-Bavarian forces in Bohemia and the small Bavarian army that remained on the Danube to defend the electorate.

The French in the meantime had stormed Prague on 26 November 1741, Francis Stephen

Francis I, Holy Roman Emperor

Francis I was Holy Roman Emperor and Grand Duke of Tuscany, though his wife effectively executed the real power of those positions. With his wife, Maria Theresa, he was the founder of the Habsburg-Lorraine dynasty...

, husband of Maria Theresa, who commanded the Austrians in Bohemia, moving too slowly to save the fortress. The Elector of Bavaria, who now styled himself Archduke of Austria, was crowned King of Bohemia (9 December 1741) and elected to the imperial throne as Charles VII

Charles VII, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles VII Albert a member of the Wittelsbach family, was Prince-elector of Bavaria from 1726 and Holy Roman Emperor from 24 January 1742 until his death in 1745...

(24 January 1742), but no active measures were undertaken.

In Bohemia the month of December was occupied in mere skirmishes. On the Danube, Khevenhüller, the best general in the Austrian service, advanced on 27 December, swiftly drove back the allies, shut them up in Linz

Linz

Linz is the third-largest city of Austria and capital of the state of Upper Austria . It is located in the north centre of Austria, approximately south of the Czech border, on both sides of the river Danube. The population of the city is , and that of the Greater Linz conurbation is about...

, and pressed on into Bavaria. Munich

Munich

Munich The city's motto is "" . Before 2006, it was "Weltstadt mit Herz" . Its native name, , is derived from the Old High German Munichen, meaning "by the monks' place". The city's name derives from the monks of the Benedictine order who founded the city; hence the monk depicted on the city's coat...

itself surrendered to the Austrians on the coronation

Coronation

A coronation is a ceremony marking the formal investiture of a monarch and/or their consort with regal power, usually involving the placement of a crown upon their head and the presentation of other items of regalia...

day of Charles VII.

At the close of this first act of the campaign the French, under the old Marshal de Broglie

François-Marie, 1st duc de Broglie

François-Marie de Broglie, 1er duc de Broglie was a French military leader.-Early years:Francois Marie de Broglie was the third son of Victor Maurice de Broglie, comte de Broglie, named for his grandfather, François Marie...

, maintained a precarious foothold in central Bohemia, menaced by the main army of the Austrians, and Khevenhüller was ranging unopposed in Bavaria. Frederick made a secret truce with Austria and thus, lay inactive in Silesia.

Campaigns of 1742

Armistice

An armistice is a situation in a war where the warring parties agree to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, but may be just a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace...

, in order to compromise Frederick with his allies. The war recommenced. Frederick had not rested on his laurels. In the uneventful summer campaign of 1741 he had found time to begin that reorganization of his cavalry which was before long to make it even more efficient than his infantry. The Emperor Charles VII, whose territories were overrun by the Austrians, asked him to create a diversion by invading Moravia. In December 1741, therefore, the Prussian general field marshal Kurt Christoph Graf von Schwerin

Kurt Christoph Graf von Schwerin

Kurt Christoph Graf von Schwerin was a Prussian Generalfeldmarschall, one of the leading commanders under Frederick the Great.-Biography:...

had crossed the border and captured Olmutz. Glatz also was invested

Siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city or fortress with the intent of conquering by attrition or assault. The term derives from sedere, Latin for "to sit". Generally speaking, siege warfare is a form of constant, low intensity conflict characterized by one party holding a strong, static...

, and the Prussian army was concentrated about Olomouc in January 1742. A combined plan of operations

Military strategy

Military strategy is a set of ideas implemented by military organizations to pursue desired strategic goals. Derived from the Greek strategos, strategy when it appeared in use during the 18th century, was seen in its narrow sense as the "art of the general", 'the art of arrangement' of troops...

was made by the French, Saxons and Prussians for the rescue of Linz. But Linz soon fell. Broglie on the Vltava

Vltava

The Vltava is the longest river in the Czech Republic, running north from its source in Šumava through Český Krumlov, České Budějovice, and Prague, merging with the Elbe at Mělník...

, weakened by the departure of the Bavarians to oppose Khevenhüller, and of the Saxons to join forces with Frederick, was in no condition to take the offensive, and large forces under Prince Charles of Lorraine

Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine

Prince Charles Alexander of Lorraine was a Lorraine-born Austrian soldier.-Background:Charles was the son of Leopold Joseph, Duke of Lorraine and Élisabeth Charlotte d'Orléans...

lay in his front from Budweis to Jihlava

Jihlava

Jihlava is a city in the Czech Republic. Jihlava is a centre of the Vysočina Region, situated on the Jihlava river on the ancient frontier between Moravia and Bohemia, and is the oldest mining town in the Czech Republic, ca. 50 years older than Kutná Hora.Among the principal buildings are the...

(Iglau). Frederick's march was made towards Iglau in the first place. Brno

Brno

Brno by population and area is the second largest city in the Czech Republic, the largest Moravian city, and the historical capital city of the Margraviate of Moravia. Brno is the administrative centre of the South Moravian Region where it forms a separate district Brno-City District...

was invested about the same time (February), but the direction of the march was changed, and instead of moving against Prince Charles, Frederick pushed on southwards by Znojmo

Znojmo