Frankfurt Parliament

Encyclopedia

.jpg)

Parliament

A parliament is a legislature, especially in those countries whose system of government is based on the Westminster system modeled after that of the United Kingdom. The name is derived from the French , the action of parler : a parlement is a discussion. The term came to mean a meeting at which...

for all of Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

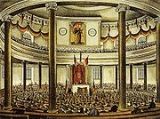

. Session was held from May 18, 1848 to May 31, 1849 in the Paulskirche at Frankfurt am Main. Its existence was both part of and the result of the "March Revolution"

Revolutions of 1848 in the German states

The Revolutions of 1848 in the German states, also called the March Revolution – part of the Revolutions of 1848 that broke out in many countries of Europe – were a series of loosely coordinated protests and rebellions in the states of the German Confederation, including the Austrian Empire...

in the states of the German Confederation

German Confederation

The German Confederation was the loose association of Central European states created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to coordinate the economies of separate German-speaking countries. It acted as a buffer between the powerful states of Austria and Prussia...

.

After long and controversial debates, the assembly produced the so-called Frankfurt Constitution (Paulskirchenverfassung or Paulskirche Constitution, actually Verfassung des Deutschen Reiches) which proclaimed a German Empire based on the principles of parliamentary democracy. This constitution

Constitution

A constitution is a set of fundamental principles or established precedents according to which a state or other organization is governed. These rules together make up, i.e. constitute, what the entity is...

fulfilled the main demands of the liberal

Liberalism

Liberalism is the belief in the importance of liberty and equal rights. Liberals espouse a wide array of views depending on their understanding of these principles, but generally, liberals support ideas such as constitutionalism, liberal democracy, free and fair elections, human rights,...

and nationalist

Nation-state

The nation state is a state that self-identifies as deriving its political legitimacy from serving as a sovereign entity for a nation as a sovereign territorial unit. The state is a political and geopolitical entity; the nation is a cultural and/or ethnic entity...

movements

Social movement

Social movements are a type of group action. They are large informal groupings of individuals or organizations focused on specific political or social issues, in other words, on carrying out, resisting or undoing a social change....

of the Vormärz

Vormärz

' is the time period leading up to the failed March 1848 revolution in the German Confederation. Also known as the Age of Metternich, it was a period of Austrian and Prussian police states and vast censorship in response to calls for liberalism...

and provided a foundation of basic rights, both of which stood in opposition

Opposition (politics)

In politics, the opposition comprises one or more political parties or other organized groups that are opposed to the government , party or group in political control of a city, region, state or country...

to Metternich's system

Carlsbad Decrees

The Carlsbad Decrees were a set of reactionary restrictions introduced in the states of the German Confederation by resolution of the Bundesversammlung on 20 September 1819 after a conference held in the spa town of Carlsbad, Bohemia...

of Restoration. The parliament also proposed a constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy is a form of government in which a monarch acts as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, whether it be a written, uncodified or blended constitution...

headed by a hereditary emperor

Hereditary monarchy

A hereditary monarchy is the most common type of monarchy and is the form that is used by almost all of the world's existing monarchies.Under a hereditary monarchy, all the monarchs come from the same family, and the crown is passed down from one member to another member of the family...

(Kaiser). The Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

n king Friedrich Wilhelm IV refused to accept the office of emperor when it was offered to him on the grounds that such a constitution and such an offer were an abridgment of the rights of the princes of the individual German states. In the 20th century, however, major elements of the Frankfurt constitution became models for the Weimar Constitution

Weimar constitution

The Constitution of the German Reich , usually known as the Weimar Constitution was the constitution that governed Germany during the Weimar Republic...

of 1919 and the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany

Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany

The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany is the constitution of Germany. It was formally approved on 8 May 1949, and, with the signature of the Allies of World War II on 12 May, came into effect on 23 May, as the constitution of those states of West Germany that were initially included...

of 1949.

Napoleonic upheavals and German Confederation

Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor is a term used by historians to denote a medieval ruler who, as German King, had also received the title of "Emperor of the Romans" from the Pope...

, Francis II

Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor

Francis II was the last Holy Roman Emperor, ruling from 1792 until 6 August 1806, when he dissolved the Empire after the disastrous defeat of the Third Coalition by Napoleon at the Battle of Austerlitz...

had relinquished the crown

Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire

The Imperial Crown , is the hoop crown of the King of the Romans, the rulers of the German Kingdom, since the High Middle Ages. Most of the kings were crowned with it. It was made probably somewhere in Western Germany, either under Otto I , by Conrad II or Conrad III during the late 10th and early...

of the Holy Roman Empire

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a realm that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe.It was ruled by the Holy Roman Emperor. Its character changed during the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, when the power of the emperor gradually weakened in favour of the princes...

and dissolved the Empire. This was the result of the Napoleonic Wars

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars were a series of wars declared against Napoleon's French Empire by opposing coalitions that ran from 1803 to 1815. As a continuation of the wars sparked by the French Revolution of 1789, they revolutionised European armies and played out on an unprecedented scale, mainly due to...

and of direct military pressure from Napoléon Bonaparte.

After the victory of Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

, the United Kingdom

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern IrelandIn the United Kingdom and Dependencies, other languages have been officially recognised as legitimate autochthonous languages under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages...

, Russia

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was a state that existed from 1721 until the Russian Revolution of 1917. It was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union...

and other states over Napoléon in 1816, the Vienna Congress created the German Confederation

German Confederation

The German Confederation was the loose association of Central European states created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 to coordinate the economies of separate German-speaking countries. It acted as a buffer between the powerful states of Austria and Prussia...

(Deutscher Bund). Austria

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire was a modern era successor empire, which was centered on what is today's Austria and which officially lasted from 1804 to 1867. It was followed by the Empire of Austria-Hungary, whose proclamation was a diplomatic move that elevated Hungary's status within the Austrian Empire...

dominated this system of loosely connected, independent states, but the system failed to account for the rising influence of Prussia

Prussia

Prussia was a German kingdom and historic state originating out of the Duchy of Prussia and the Margraviate of Brandenburg. For centuries, the House of Hohenzollern ruled Prussia, successfully expanding its size by way of an unusually well-organized and effective army. Prussia shaped the history...

. After the so-called "Wars of Liberation" (Befreiungskriege, the German term for the German part of the War of the Sixth Coalition), many contemporaries had expected a nation-state solution and thus considered the subdivision of Germany as unsatisfactory.

Apart from this nationalist component, calls for civic rights influenced political discourse. The Napoleonic Code Civil had led to the introduction of civic rights in some German states in the early 19th century. Furthermore, some German states had adopted constitutions after the foundation of the German Confederacy. Between 1819 and 1830, the Carlsbad Decrees

Carlsbad Decrees

The Carlsbad Decrees were a set of reactionary restrictions introduced in the states of the German Confederation by resolution of the Bundesversammlung on 20 September 1819 after a conference held in the spa town of Carlsbad, Bohemia...

and other instances of Restoration politics limited such developments. The unrest that resulted from the 1830 French

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

July Revolution

July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution or in French, saw the overthrow of King Charles X of France, the French Bourbon monarch, and the ascent of his cousin Louis-Philippe, Duke of Orléans, who himself, after 18 precarious years on the throne, would in turn be overthrown...

led to a temporary reversal of that trend, but after the demonstration for civic rights and national unity at the 1832 Hambach Festival, and the abortive attempt at an armed rising in the 1833 Frankfurter Wachensturm

Frankfurter Wachensturm

The Frankfurter Wachensturm on April 3rd 1833 was a failed attempt to start a revolution in Germany.-Events:...

, the pressure on representatives of constitutional or democratic ideas was raised through measures such as censorship

Censorship

thumb|[[Book burning]] following the [[1973 Chilean coup d'état|1973 coup]] that installed the [[Military government of Chile |Pinochet regime]] in Chile...

and bans on public assemblies.

The 1840s

In the mid-1840s saw an increase of the frequency of internal crises. This was partially the result of large-scale political developments, such as the escalation of the future of the duchies of Schleswig and HolsteinSchleswig-Holstein Question

The Schleswig-Holstein Question was a complex of diplomatic and other issues arising in the 19th century from the relations of two duchies, Schleswig and Holstein , to the Danish crown and to the German Confederation....

and the erection of Bundesfestungen (large scale fortifications controlled by the German Confederation) at Rastatt

Rastatt

Rastatt is a city and baroque residence in the District of Rastatt, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is located on the Murg river, above its junction with the Rhine and has a population of around 50'000...

and Ulm

Ulm

Ulm is a city in the federal German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the River Danube. The city, whose population is estimated at 120,000 , forms an urban district of its own and is the administrative seat of the Alb-Donau district. Ulm, founded around 850, is rich in history and...

. Additionally, a series of bad harvest

Harvest

Harvest is the process of gathering mature crops from the fields. Reaping is the cutting of grain or pulse for harvest, typically using a scythe, sickle, or reaper...

s in parts of Germany, notably the southwest, led to widely spread famine-related unrest. The changes caused by the beginnings of industrialisation

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period from the 18th to the 19th century where major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, mining, transportation, and technology had a profound effect on the social, economic and cultural conditions of the times...

exacerbated social and economic tensions considerably.

Meanwhile, in the reform-oriented states, such as Baden

Baden

Baden is a historical state on the east bank of the Rhine in the southwest of Germany, now the western part of the Baden-Württemberg of Germany....

, the development of a lively scene of Vereine (club

Club

A club is an association of two or more people united by a common interest or goal. A service club, for example, exists for voluntary or charitable activities; there are clubs devoted to hobbies and sports, social activities clubs, political and religious clubs, and so forth.- History...

s or voluntary association

Voluntary association

A voluntary association or union is a group of individuals who enter into an agreement as volunteers to form a body to accomplish a purpose.Strictly speaking, in many jurisdictions no formalities are necessary to start an association...

s) provided an organisational framework for democratic, or popular, opposition. Especially in south west Germany, censorship could not effectively suppress the press. At such rallies by as the Offenburg Popular Assembly of September 1847, radical democrats called to overthrow the status quo. At the same time, the bourgeois (here used to describe the Middle Class

Middle class

The middle class is any class of people in the middle of a societal hierarchy. In Weberian socio-economic terms, the middle class is the broad group of people in contemporary society who fall socio-economically between the working class and upper class....

) opposition had increased its networking activities and began coordinating its activities in the individual chamber parliaments

Bicameralism

In the government, bicameralism is the practice of having two legislative or parliamentary chambers. Thus, a bicameral parliament or bicameral legislature is a legislature which consists of two chambers or houses....

more and more confidently. Thus, at the Heppenheim Conference on 10 October 1847, eighteen liberal members from a variety of German states met to discuss common motions for a German nation-state.

In 1847 and 1848, broader European developments

Revolutions of 1848

The European Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Spring of Nations, Springtime of the Peoples or the Year of Revolution, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe in 1848. It was the first Europe-wide collapse of traditional authority, but within a year reactionary...

aggravated this tension. In France, revolutionary workers and students deposed the Citizen King Louis-Philippe

Louis-Philippe of France

Louis Philippe I was King of the French from 1830 to 1848 in what was known as the July Monarchy. His father was a duke who supported the French Revolution but was nevertheless guillotined. Louis Philippe fled France as a young man and spent 21 years in exile, including considerable time in the...

in the February Revolution

February Revolution

The February Revolution of 1917 was the first of two revolutions in Russia in 1917. Centered around the then capital Petrograd in March . Its immediate result was the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II, the end of the Romanov dynasty, and the end of the Russian Empire...

; their action resulted in the declaration of the Second Republic

French Second Republic

The French Second Republic was the republican government of France between the 1848 Revolution and the coup by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte which initiated the Second Empire. It officially adopted the motto Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité...

. In many European states, the resistance against Restoration policies increased and led to revolutionary unrest. In several parts of the Austrian Empire

Revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas

From March 1848 through July 1849, the Habsburg Austrian Empire was threatened by revolutionary movements. Much of the revolutionary activity was of a nationalist character: the empire, ruled from Vienna, included Austrian Germans, Hungarians, Slovenes, Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Ruthenians,...

, namely in Hungary

Hungarian Revolution of 1848

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848 was one of many of the European Revolutions of 1848 and closely linked to other revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas...

, Bohemia

Bohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

, Romania

Wallachian Revolution of 1848

The Wallachian Revolution of 1848 was a Romanian liberal and Romantic nationalist uprising in the Principality of Wallachia. Part of the Revolutions of 1848, and closely connected with the unsuccessful revolt in the Principality of Moldavia, it sought to overturn the administration imposed by...

, and throughout Italy, in particular in Sicily

Sicilian revolution of independence of 1848

The Sicilian revolution of independence of 1848 occurred in a year replete with revolutions and popular revolts. It commenced on 12 January 1848, and therefore was one of the first of the numerous revolutions to occur that year...

, Rome

Roman Republic (19th century)

The Roman Republic was a state declared on February 9, 1849, when the government of Papal States was temporarily substituted by a republican government due to Pope Pius IX's flight to Gaeta. The republic was led by Carlo Armellini, Giuseppe Mazzini and Aurelio Saffi...

, and Northern Italy

Revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states

The 1848 revolutions in the Italian states were organized revolts in the states of Italy led by intellectuals and agitators who desired a liberal government. As Italian nationalists they sought to eliminate reactionary Austrian control...

, there were bloody revolts, replete with calls for local or regional autonomy and even for national independence

Independence

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state in which its residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory....

.

Friedrich Daniel Bassermann

Friedrich Daniel Bassermann

Friedrich Daniel Bassermann was a German liberal politician who is best known for calling for a pan-German Parliament at the Frankfurt Parliament...

, a liberal deputy in the second chamber of the parliament of Baden

Baden

Baden is a historical state on the east bank of the Rhine in the southwest of Germany, now the western part of the Baden-Württemberg of Germany....

, helped to trigger the final impulse for the election of a pan-German assembly (or parliament). On 12 February 1848, referring to his own motion (Motion Bassermann) in 1844 and a comparable one by Carl Theodor Welcker

Carl Theodor Welcker

-Biography:He was a member of the Baden legislature, and a colleague of Karl von Rotteck's in the editing of The Independent . He also joined Rotteck in writing the Staatslexikon . He was a member of the Frankfurt Parliament of 1848....

in 1831, he called for a representation, elected by the people, at the Bundestag

Bundesversammlung (German Confederation)

The Federal Assembly was the only central institution of the German Confederation from 1815 until 1848, and from 1850 until 1866. The Federal Assembly had its seat in the palais Thurn und Taxis in Frankfurt...

in Frankfurt am Main. The Bundestag (or Bundesversammlung), made up of representatives of the individual princes, was the only institution representing the whole confederation. Two weeks later, news of the successful coup in France fanned the flames of the revolutionary mood. The revolution on German soil began in Baden, with the occupation of the Ständehaus at Karlsruhe

Karlsruhe

The City of Karlsruhe is a city in the southwest of Germany, in the state of Baden-Württemberg, located near the French-German border.Karlsruhe was founded in 1715 as Karlsruhe Palace, when Germany was a series of principalities and city states...

. This was followed in April by the Heckerzug (named after its leader, Friedrich Hecker), the first of three revolutionary risings in the Grand Duchy. Within a few days and weeks, the revolts spread to the other German principalities

Principality

A principality is a monarchical feudatory or sovereign state, ruled or reigned over by a monarch with the title of prince or princess, or by a monarch with another title within the generic use of the term prince....

.

The March Revolution

The central demands of the German opposition(s) were the granting of basic and civic rights regardless of property requirements, the appointment of liberal governments in the individual states and most importantly the creation of a German nation-state, with a pan-German constitution and a popular assembly. On 5 March 1848, opposition politicians and state deputies met at the Heidelberg Assembly to discuss these issues. They resolved to form a Vorparlament (a pre-parliament), which was to prepare the elections for a national constitutional assembly. They also elected a "Committee of Seven" (Siebenerausschuss), which proceeded to invite 500 individuals to Frankfurt.This development was accompanied and supported since early March by protest rallies and risings in many German states, including Baden, the Kingdom of Bavaria

Kingdom of Bavaria

The Kingdom of Bavaria was a German state that existed from 1806 to 1918. The Bavarian Elector Maximilian IV Joseph of the House of Wittelsbach became the first King of Bavaria in 1806 as Maximilian I Joseph. The monarchy would remain held by the Wittelsbachs until the kingdom's dissolution in 1918...

, the Kingdom of Saxony

Kingdom of Saxony

The Kingdom of Saxony , lasting between 1806 and 1918, was an independent member of a number of historical confederacies in Napoleonic through post-Napoleonic Germany. From 1871 it was part of the German Empire. It became a Free state in the era of Weimar Republic in 1918 after the end of World War...

, the Kingdom of Württemberg

Kingdom of Württemberg

The Kingdom of Württemberg was a state that existed from 1806 to 1918, located in present-day Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It was a continuation of the Duchy of Württemberg, which came into existence in 1495...

, Austria and Prussia. Under such pressure, the individual princes recalled the existing conservative governments and replaced them with more liberal committees, the so-called "March Governments" (Märzregierungen). On 10 March 1848, the Bundestag of the German Confederation appointed a "Committee of Seventeen" (Siebzehnerausschuss) to prepare a draft constitution; on 20 March, the Bundestag urged the states of the confederation to call elections for a constitutional assembly. After bloody street fights (Barrikadenaufstand) in Prussia, a Prussian National Assembly was also convened, with the task of preparing a constitution for that kingdom.

The Vorparlament was in session at the Paulskirche (St. Paul's Church) in Frankfurt from 31 March to 3 April, chaired by Carl Joseph Anton Mittermaier

Carl Joseph Anton Mittermaier

Carl Joseph Anton Mittermaier was a German jurist.-Biography:He was born in Munich, and educated at the universities of Landshut and Heidelberg...

. With the support of the moderate liberals, and against the opposition of the radical democrats, it decided to cooperate with the Bundestag

Bundesversammlung (German Confederation)

The Federal Assembly was the only central institution of the German Confederation from 1815 until 1848, and from 1850 until 1866. The Federal Assembly had its seat in the palais Thurn und Taxis in Frankfurt...

, to form a national constitutional assembly which would write a new constitution. For the transitional period until the actual formation of that assembly, the Vorparlament formed the Committee of Fifty (Fünfzigerausschuss), as a representation to face the German Confederation.

The electoral law for the new national assembly was up to the individual states of the confederation, who chose different solutions. Württemberg, Holstein, the Electorate

Prince-elector

The Prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire were the members of the electoral college of the Holy Roman Empire, having the function of electing the Roman king or, from the middle of the 16th century onwards, directly the Holy Roman Emperor.The heir-apparent to a prince-elector was known as an...

of Hesse-Kassel

Hesse-Kassel

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel or Hesse-Cassel was a state in the Holy Roman Empire under Imperial immediacy that came into existence when the Landgraviate of Hesse was divided in 1567 upon the death of Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse. His eldest son William IV inherited the northern half and the...

(Hesse-Cassel) and the four remaining free cities

Free Imperial City

In the Holy Roman Empire, a free imperial city was a city formally ruled by the emperor only — as opposed to the majority of cities in the Empire, which were governed by one of the many princes of the Empire, such as dukes or prince-bishops...

(Hamburg

Hamburg

-History:The first historic name for the city was, according to Claudius Ptolemy's reports, Treva.But the city takes its modern name, Hamburg, from the first permanent building on the site, a castle whose construction was ordered by the Emperor Charlemagne in AD 808...

, Lübeck

Lübeck

The Hanseatic City of Lübeck is the second-largest city in Schleswig-Holstein, in northern Germany, and one of the major ports of Germany. It was for several centuries the "capital" of the Hanseatic League and, because of its Brick Gothic architectural heritage, is listed by UNESCO as a World...

, Bremen

Bremen

The City Municipality of Bremen is a Hanseatic city in northwestern Germany. A commercial and industrial city with a major port on the river Weser, Bremen is part of the Bremen-Oldenburg metropolitan area . Bremen is the second most populous city in North Germany and tenth in Germany.Bremen is...

and Frankfurt) held direct elections. Most states chose an indirect procedure, usually involving a first round, voting to constitute an Electoral college

Electoral college

An electoral college is a set of electors who are selected to elect a candidate to a particular office. Often these represent different organizations or entities, with each organization or entity represented by a particular number of electors or with votes weighted in a particular way...

which chose the actual deputies in a second round. There also were different arrangements regarding the right to vote, as the Frankfurt guidelines only stipulated that voters should be independent (selbständig) adult males. The definition of independence was handled differently from state to state and was frequently the subject of vociferous protests. Usually, it was interpreted to exclude the recipients of any poverty-related support, but in some areas it also barred any person who did not have a household of their own, including apprentices living at their masters' homes. Even with restrictions, however, it is estimated that about 85% of the male population could vote. In Prussia, the definition used would have pushed this up to 90%, whereas the laws were much more restrictive in Saxony, Baden and Hanover

Kingdom of Hanover

The Kingdom of Hanover was established in October 1814 by the Congress of Vienna, with the restoration of George III to his Hanoverian territories after the Napoleonic era. It succeeded the former Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg , and joined with 38 other sovereign states in the German...

. Originally, 649 electoral districts had been agreed upon, but eventually only approximately 585 members were elected. Boycott

Boycott

A boycott is an act of voluntarily abstaining from using, buying, or dealing with a person, organization, or country as an expression of protest, usually for political reasons...

s in several Austrian constituencies with non-German populations, and complications in Tiengen

Waldshut-Tiengen

Waldshut-Tiengen is a city in southwestern Baden-Württemberg right at the Swiss border. It is the district seat and at the same time the biggest city in Waldshut district and a "middle centre" in the area of the "high centre" Lörrach/Weil am Rhein to whose middle area most towns and communities in...

(Baden), (where the leader of the Heckerzug rebellion, Freidrich Hecker, in exile in Switzerland

Switzerland

Switzerland name of one of the Swiss cantons. ; ; ; or ), in its full name the Swiss Confederation , is a federal republic consisting of 26 cantons, with Bern as the seat of the federal authorities. The country is situated in Western Europe,Or Central Europe depending on the definition....

, was elected in two rounds) caused the discrepancy.

Social background of the deputies

The social make-up of the total of 809 or 812 (replacements included) members of the Frankfurt National Assembly (see list on German wikipedia) was very homogeneous throughout the session. The parliament mostly represented the educated bourgeoisie (Middle Class). 95 % of deputies had the abiturAbitur

Abitur is a designation used in Germany, Finland and Estonia for final exams that pupils take at the end of their secondary education, usually after 12 or 13 years of schooling, see also for Germany Abitur after twelve years.The Zeugnis der Allgemeinen Hochschulreife, often referred to as...

, more than three quarters had been to university, half of which had studied jurisprudence

Jurisprudence

Jurisprudence is the theory and philosophy of law. Scholars of jurisprudence, or legal theorists , hope to obtain a deeper understanding of the nature of law, of legal reasoning, legal systems and of legal institutions...

. A considerable number of deputies were members of a Corps

German Student Corps

Corps are the oldest still-existing kind of Studentenverbindung, Germany's traditional university corporations; their roots date back to the 15th century. The oldest corps still existing today was founded in 1789...

or a Burschenschaft

Burschenschaft

German Burschenschaften are a special type of Studentenverbindungen . Burschenschaften were founded in the 19th century as associations of university students inspired by liberal and nationalistic ideas.-History:-Beginnings 1815–c...

. In terms of profession, upper-level civil servants formed the majority: this group included a total of 436 deputies, including 49 university lecturers or professors, 110 judges or prosecutors, and 115 high administrative clerks and district administrators (Landräte). Due to their oppositional views, many of them had already been in conflict with their princes for several years, including professors such as Jacob Grimm

Jacob Grimm

Jacob Ludwig Carl Grimm was a German philologist, jurist and mythologist. He is best known as the discoverer of Grimm's Law, the author of the monumental Deutsches Wörterbuch, the author of Deutsche Mythologie and, more popularly, as one of the Brothers Grimm, as the editor of Grimm's Fairy...

, Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann

Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann

Friedrich Christoph Dahlmann was a German historian and politician.He came of an old Hanseatic family of Wismar, then controlled by Sweden...

, Georg Gottfried Gervinus

Georg Gottfried Gervinus

Georg Gottfried Gervinus was a German literary and political historian.-Biography:Gervinus was born in Darmstadt. He was educated at the gymnasium of the town, and intended for a commercial career, but in 1825 he became a student of the university of Giessen...

and Wilhelm Eduard Albrecht

Wilhelm Eduard Albrecht

Wilhelm Eduard Albrecht was a German constitutional lawyer, jurist, and docent. Albrecht was most notable as a member of the Göttingen Seven, a group of academics who in 1837 protested the abrogation of the constitution of the Kingdom of Hanover by Ernest Augustus I.Albrecht was born in Elbing ,...

(all counted among the Göttingen Seven

Göttingen Seven

The Göttingen Seven were a group of seven professors from Göttingen. In 1837 they protested against the abolition or alteration of the constitution of the Kingdom of Hanover by Ernest Augustus and refused to swear an oath to the new king of Hanover...

, and politicians such as Welcker and Itzstein who had been champions of constitutional rights for two decades. Among the professors, besides lawyers, experts in German Studies

German studies

German studies is the field of humanities that researches, documents, and disseminates German language and literature in both its historic and present forms. Academic departments of German studies often include classes on German culture, German history, and German politics in addition to the...

and historians

Historiography

Historiography refers either to the study of the history and methodology of history as a discipline, or to a body of historical work on a specialized topic...

were especially common, due to the fact that under the sway of restoration politics, academic meetings in such disciplines, e.g. the Germanisten-Tage of 1846 and 1847, were often the only occasions where national themes could be discussed freely. Apart from those mentioned above, the academic Ernst Moritz Arndt

Ernst Moritz Arndt

Ernst Moritz Arndt was a German nationalistic and antisemitic author and poet. Early in his life, he fought for the abolition of serfdom, later against Napoleonic dominance over Germany, and had to flee to Sweden for some time due to his anti-French positions...

, Johann Gustav Droysen

Johann Gustav Droysen

Johann Gustav Droysen was a German historian. His history of Alexander the Great was the first work representing a new school of German historical thought that idealized power held by so-called "great" men...

, Carl Jaup, Friedrich Theodor Vischer

Friedrich Theodor Vischer

Friedrich Theodor Vischer was a German writer on the philosophy of art.Born at Ludwigsburg as the son of a clergyman, Vischer was educated at Tübinger Stift, and began life in his father's profession...

and Georg Waitz

Georg Waitz

Georg Waitz was a German historian and politician.He was born at Flensburg, in the duchy of Schleswig and educated at the Flensburg gymnasium and the universities of Kiel and Berlin...

are especially notable.

Because of this composition, the National Assembly was later often dismissively dubbed the Professorenparlament ("Professors' parliament") and ridiculed with verses such as „Dreimal 100 Advokaten – Vaterland, du bist verraten; dreimal 100 Professoren – Vaterland, du bist verloren!“ ("Three times 100 advocates - Fatherland, you are betrayed; three times 100 professors - Fatherland, you are doomed".

149 deputies were self-employed bourgeois

Middle class

The middle class is any class of people in the middle of a societal hierarchy. In Weberian socio-economic terms, the middle class is the broad group of people in contemporary society who fall socio-economically between the working class and upper class....

professionals, such as lawyers, doctors, journalists or clergymen, including well-known politicians such as Alexander von Soiron, Johann Jacoby

Johann Jacoby

Johann Jacoby was a Left-wing Prussian Jewish politician.- Biography :The son of a merchant, Jacoby studied medicine and in 1830 started practicing in his native city, but soon became involved in political activities in a liberal interest, which involved him in prosecutions and made him well-known...

, Karl Mathy

Karl Mathy

Karl Mathy , was a Badensian statesman.He was born at Mannheim. He studied law and politics at Heidelberg, and entered the Baden government department of finance in 1829...

, Johann Gustav Heckscher, Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler and Wilhelm Murschel.

The economically active Middle Class was represented by only about 60 deputies, including many publishers, including Bassermann and Georg Friedrich Kolb, but also businessmen, industrialists and bankers, such as Hermann Henrich Meier, Ernst Merck

Ernst Merck

Freiherr Ernst Merck was a German businessman and politician.Merck, born in Hamburg, was a member of the Frankfurt Parliament for a year from 1848 to 1849....

, Hermann von Beckerath

Hermann von Beckerath

Hermann von Beckerath was a banker and Prussian statesman.-Biography:He was born at Krefeld, in Rhenish Prussia. His youth was spent in learning the business of banking, after which he became the head of a banking firm which had considerable influence in German financing, especially in the Rhenish...

, Gustav Mevissen

Gustav von Mevissen

Gustav Mevissen, after 1884 Gustav von Mevissen was a German businessman and politician.Mevissen was born in Dülken, Rhine Province. He started by investing in textile industry and later in railway construction and heavy industry. He founded numerous banks, including the Darmstädter Bank, and...

and Carl Mez.

Tradesmen and representatives of agriculture were very poorly represented - the latter were mostly represented by big landowners from east of the Elbe

Elbe

The Elbe is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Krkonoše Mountains of the northwestern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia , then Germany and flowing into the North Sea at Cuxhaven, 110 km northwest of Hamburg...

, accompanied by only three farmers. Craftsmen like Robert Blum

Robert Blum

thumb|Painting by August Hunger of Robert Blum between 1845 and 1848Robert Blum was a German democratic politician, publicist, poet, publisher, revolutionist and member of the National Assembly of 1848. In his fight for a strong, unified Germany he opposed ethnocentrism and it was his strong...

or Wilhelm Wolff

Wilhelm Wolff

Wilhelm Friedrich Wolff, nicknamed Lupus was a German schoolmaster from Tarnau , Galicia. In 1831 he became active as a radical student organization member, something he was imprisoned for between 1834 and 1838...

were associated almost exclusively with the radical democratic Left

Left-wing politics

In politics, Left, left-wing and leftist generally refer to support for social change to create a more egalitarian society...

, as they knew the social problems of the underprivileged classes from personal observations. A few of them, e.g.. Wolff, already saw themselves as explicit socialists

Socialism

Socialism is an economic system characterized by social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the economy; or a political philosophy advocating such a system. "Social ownership" may refer to any one of, or a combination of, the following: cooperative enterprises,...

.

A further striking aspect is the large number of well-known writers among the deputies, including Anastasius Grün

Anton Alexander Graf von Auersperg

Count Anton Alexander von Auersperg, also known under the pen name Anastasius Grün , was an Austrian poet and liberal politician from Carniola.-Biography:...

, Johann Ludwig Uhland, Heinrich Laube

Heinrich Laube

Heinrich Laube , German dramatist, novelist and theatre-director, was born at Sprottau in Prussian Silesia.-Life:He studied theology at Halle and Breslau , and settled in Leipzig in 1832...

and Victor Scheffel.

On 18 May 1848, circa 330 deputies assembled in the Kaisersaal and walked solemnly to the Paulskirche to hold the first session of the German national assembly, under its chairman (by seniority) Friedrich Lang

Friedrich Lang

Major Friedrich Lang was a German World War II Luftwaffe Stuka ace.For a list of Luftwaffe ground attack aces see List of German World War II Ground Attack aces He was also a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords...

. Heinrich von Gagern

Heinrich von Gagern

Heinrich Wilhelm August Freiherr von Gagern was a statesman who argued for the unification of Germany.The third son of Hans Christoph Ernst, Baron von Gagern, a liberal statesman from Hesse, Heinrich von Gagern was born at Bayreuth, educated at the military academy at Munich, and, as an officer in...

, one of the best-known liberals throughout Germany, was elected president of the parliament.

Factions and committees

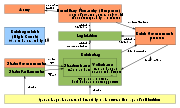

While the opening session had generally been quite chaotic, with the deputies seated haphazardly, independent of their political affiliations, ordered parliamentary procedures developed quickly. Soon, deputies started assembling in Klubs (clubs), which served as discussion groups for kindred spirits and led to the development of Fraktionen (Parliamentary groups or factions), a necessary prerequisite for the development of political majorities. These Fraktionen were perceived as clubs and thus usually named after the location of their meetings; generally, they were quite unstable. According to their stances, especially on the constitution, on the powers of parliament and on central government as opposed to individual states, they are broadly divided into three basic camps:

- The democratic left (demokratische Linke) - also called the "Ganzen" ("the whole ones") in contemporary jargon - consisting of the extreme and the moderate left (the Deutscher Hof group and its later split-offs Donnersberg, Nürnberger Hof and Westendhall).

- The liberal centre - the so-called "Halben" ("Halves"), consisting of the left and right centre (the right-wing liberal CasinoCasino-FraktionThe Casino faction was a moderate liberal faction within the Frankfurt Parliament formed on June 25, 1848. Like most of the factions in the parliament, its name was a reference to the usual meeting place of its members in Frankfurt am Main. Casino was the largest and most influential fraction at...

and the left-wing liberal Württemberger Hof, and the later split-offs Augsburger Hof, Landsberg and Pariser Hof). - The conservative right, composed of Protestants and conservatives (first Steinernes Haus, later Café Milani).

The largest groupings in numerical terms were the Casino, the Württemberger Hof and beginning in 1849 the combined left, appearing as the Centralmärzverein ("Central March Club").

In his memoirs, the deputy Robert Mohl

Robert von Mohl

Robert von Mohl was a German jurist. Father of diplomat Ottmar von Mohl. Brother of Hugo von Mohl and Julius von Mohl....

wrote about the formation and functioning of the Clubs:

- "that originally there were four different clubs, based on the basic political orientations [...] That in regard to the most important major questions, for example about Austria's participation and about the election of emperors, the usual club-based divisions could be abandoned temporarily to create larger overall groups, as the United Left, the Greater Germans in Hotel Schröder, the Imperials in Hotel Weidenbusch.

- "These party meetings were indeed an important part of political life in Frankfurt, significant for positive, but clearly also for negative, results. A club offered a get-together with politically kindred spirits, some of whom became true friends, comparably rapid decisions and, as a result, perhaps success in the overall assembly.".

Presidents of the National Assembly

- Friedrich LangFriedrich LangMajor Friedrich Lang was a German World War II Luftwaffe Stuka ace.For a list of Luftwaffe ground attack aces see List of German World War II Ground Attack aces He was also a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords...

as president by seniority (18 May 1848 until 19 May 1848) - Heinrich von GagernHeinrich von GagernHeinrich Wilhelm August Freiherr von Gagern was a statesman who argued for the unification of Germany.The third son of Hans Christoph Ernst, Baron von Gagern, a liberal statesman from Hesse, Heinrich von Gagern was born at Bayreuth, educated at the military academy at Munich, and, as an officer in...

(19 May 1848 until 16 December 1848) - Eduard Simson (18 December 1848 until 11 May 1849)

- Theodor Reh (12 May 1849 until 30 May 1849)

- Friedrich Wilhelm LöweWilhelm LoeweWilhelm Loewe was a German physician and Liberal politician, also called Wilhelm Loewe-Kalbe or Wilhelm Loewe von Kalbe....

as president of the StuttgartStuttgartStuttgart is the capital of the state of Baden-Württemberg in southern Germany. The sixth-largest city in Germany, Stuttgart has a population of 600,038 while the metropolitan area has a population of 5.3 million ....

rump parliament (6 June 1849 until 18 June 1849)

Provisional central power

While the left demanded to solve this situation by creating a revolutionary parliamentary government, on 24 June 1848, the Paulskirche parliament voted, with a 450 votes against 100, for a so-called Provisional Central Power (Provisorische Zentralgewalt). This newly created provisional government was headed by Archduke Johann of Austria

Archduke Johann of Austria

Archduke John of Austria was a member of the Habsburg dynasty, an Austrian field marshal and German Imperial regent .-Biography:...

as regent

Regent

A regent, from the Latin regens "one who reigns", is a person selected to act as head of state because the ruler is a minor, not present, or debilitated. Currently there are only two ruling Regencies in the world, sovereign Liechtenstein and the Malaysian constitutive state of Terengganu...

(Reichsverweser), i.e., as a temporary head of state

Head of State

A head of state is the individual that serves as the chief public representative of a monarchy, republic, federation, commonwealth or other kind of state. His or her role generally includes legitimizing the state and exercising the political powers, functions, and duties granted to the head of...

. Johann named as August von Jochmus

August Giacomo Jochmus

August Giacomo Jochmus Freiherr von Cotignola was an Austrian lieutenant field marshal, and minister of the German Confederation...

as Foreign Minister and Navy minister

Reichsflotte

The Reichsflotte was the first all-German Navy. It was founded on 14 June 1848 during the Revolutions of 1848 in the German states by the Frankfurt Parliament to provide a naval force in the First Schleswig War against Denmark.-History:...

. The practical task of government was performed by a cabinet, consisting of a college of ministers under the leadership of a prime minister (Ministerpräsident). At the same time, the Provisional Central Power built a government apparatus, made up of specialised ministries and special envoys, employing, for financial reasons, mainly deputies of the assembly. After the Bundesversammlung of the German Confederation had declared the end of its work and delegated its responsibilities to the provisional government on 12 July 1848, Archduke Johann appointed his first government, under Ministerpräsident Prince Karl zu Leiningen, on 15 July.

Ministerpräsidenten of the Imperial Government

- Karl zu LeiningenCarl, 3rd Prince of LeiningenCarl Friedrich Wilhelm Emich, Prince of Leiningen was a German nobleman and the elder half-brother of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom.-Biography:...

(15 July 1848 until 5 September 1848) - Anton von Schmerling (24 September 1848 until 15 December 1848)

- Heinrich von GagernHeinrich von GagernHeinrich Wilhelm August Freiherr von Gagern was a statesman who argued for the unification of Germany.The third son of Hans Christoph Ernst, Baron von Gagern, a liberal statesman from Hesse, Heinrich von Gagern was born at Bayreuth, educated at the military academy at Munich, and, as an officer in...

(17 December 1848 until 10 May 1849)

Schleswig-Holstein Question and development of political camps

Influenced by the general nationalist atmosphere, the political situation in Schleswig and Holstein became especially explosive. According to the 1460 Treaty of RibeTreaty of Ribe

The Treaty of Ribe was a proclamation at Ribe made by King Christian I of Denmark to a number of German nobles enabling himself to become Count of Holstein and regain control of Denmark's lost Duchy of Schleswig...

, the two duchies were to remain eternally undivided and stood in personal union

Personal union

A personal union is the combination by which two or more different states have the same monarch while their boundaries, their laws and their interests remain distinct. It should not be confused with a federation which is internationally considered a single state...

with Denmark

Denmark

Denmark is a Scandinavian country in Northern Europe. The countries of Denmark and Greenland, as well as the Faroe Islands, constitute the Kingdom of Denmark . It is the southernmost of the Nordic countries, southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark...

. Nonetheless, only Holstein was part of the German Confederation, whereas Schleswig, with a mixed population of German-speakers and Danish speakers, formed a Danish fiefdom

Fiefdom

A fee was the central element of feudalism and consisted of heritable lands granted under one of several varieties of feudal tenure by an overlord to a vassal who held it in fealty in return for a form of feudal allegiance and service, usually given by the...

. German national liberals and the left demanded that Schleswig be admitted to the German Confederation and be represented at the national assembly, while Danish national liberals wanted to incorporate Schleswig into a new Danish national state.

The Danish Navy started a blockade of German harbours, which the parliament tried to counter by founding a German Reichsflotte

Reichsflotte

The Reichsflotte was the first all-German Navy. It was founded on 14 June 1848 during the Revolutions of 1848 in the German states by the Frankfurt Parliament to provide a naval force in the First Schleswig War against Denmark.-History:...

Navy on 14 June 1848. Then, under orders from the German Confederation, Prussian troops

Prussian Army

The Royal Prussian Army was the army of the Kingdom of Prussia. It was vital to the development of Brandenburg-Prussia as a European power.The Prussian Army had its roots in the meager mercenary forces of Brandenburg during the Thirty Years' War...

occupied Schleswig-Holstein. On 26 August Prussia and Denmark, under pressure from Britain, Russia and France, signed a ceasefire

Ceasefire

A ceasefire is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be declared as part of a formal treaty, but they have also been called as part of an informal understanding between opposing forces...

in Malmö

Malmö

Malmö , in the southernmost province of Scania, is the third most populous city in Sweden, after Stockholm and Gothenburg.Malmö is the seat of Malmö Municipality and the capital of Skåne County...

(Sweden

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

). Its terms included the withdrawal of all soldiers from Schleswig-Holstein and a shared administration of the land.

On 5 September 1848, at Dahlmann's instigation, the Frankfurt Assembly initially rejected the Malmö Treaty, which had been signed without consulting the assembly. It was defeated with 238 against 221 votes. After that, Leiningen resigned as Ministerpräsident. As Dahlmann was unable to form a new government, Anton von Schmerling succeeded Leiningen.

In a second vote, on 16 September 1848, the Assembly accepted the de facto position and accepted the Treaty with a narrow majority. In Frankfurt this led to the Septemberunruhen ("September unrest"), a popular rising that entailed the murder of parliamentarians from the Casino faction, Lichnowsky

Felix Lichnowsky

Felix Lichnowsky, fully Felix Maria Vincenz Andreas Fürst von Lichnowsky, Graf von Werdenberg was a son of the historian Eduard Lichnowsky who had written a history of the Habsburg family....

and Auerswald

Hans Adolf Erdmann von Auerswald

Hans Adolf Erdmann von Auerswald was a Prussian general and politician.-Biography:Auerswald was born in Faulen, West Prussia where the family possessed the estates of Plauth and Tromnau....

. The National Assembly was forced to call for the support of Prussian and Austrian troops serving the Confederation at the confederate fortification of Mainz

Mainz

Mainz under the Holy Roman Empire, and previously was a Roman fort city which commanded the west bank of the Rhine and formed part of the northernmost frontier of the Roman Empire...

.

Henceforth, the radical democrats, whose views were both leftist and nationalist, ceased to accept their representation through the National Assembly. In several states of the German Confederation, they resorted to individual revolutionary activities. For example, on 21 September, Gustav Struve

Gustav Struve

Gustav Struve, known as Gustav von Struve until he gave up his title, , was a German politician, lawyer and publicist, and a revolutionary during the German revolution of 1848-1849 in Baden...

declared a German republic at Lörrach

Lörrach

Lörrach is a city in southwest Germany, in the valley of the Wiese, close to the French and the Swiss border. It is the capital of the district of Lörrach in Baden-Württemberg. The biggest industry is the chocolate factory Milka...

, thus starting the second democratic rising in Baden. The nationalist unrest in Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

spread to Vienna

Vienna

Vienna is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Austria and one of the nine states of Austria. Vienna is Austria's primary city, with a population of about 1.723 million , and is by far the largest city in Austria, as well as its cultural, economic, and political centre...

in early October, leading to a third revolutionary wave, the Wiener Oktoberaufstand ("Vienna October rising"), which further impeded the work of the Assembly.

Thus, the acceptance of the Treaty of Malmö marks the latest possible date of the final breach of cooperation between the liberal and the radical democratic camps. Radical democratic politicians saw it as final confirmation that the bourgeois politicians, as Hecker had said in spring 1848, "negotiate with the princes" instead of "acting in the name of the sovereign people", thus becoming traitors to the cause of the people. In contrast, the bourgeois liberals saw the unrests as further proof for what they saw as the short-sighted and irresponsible stance of the left, and of the dangers of a "left-wing mob" spreading anarchy

Anarchy

Anarchy , has more than one colloquial definition. In the United States, the term "anarchy" typically is meant to refer to a society which lacks publicly recognized government or violently enforced political authority...

and murder. This early divide of its main components was of major importance for the later failure of the National Assembly, as it caused lasting damage not only to the esteem and acceptance of the parliament, but also to the cooperation among its factions.

Oktoberaufstand and execution of Blum

After the October Rising at Vienna had escalated, forcing the Austrian government to flee the city, the National Assembly, instigated by left-wing deputies, attempted to mediate between the Austrian government and the revolting revolutionaries. In the meantime, the Austrian government violently suppressed the rising. In the course of events, the deputy Robert BlumRobert Blum

thumb|Painting by August Hunger of Robert Blum between 1845 and 1848Robert Blum was a German democratic politician, publicist, poet, publisher, revolutionist and member of the National Assembly of 1848. In his fight for a strong, unified Germany he opposed ethnocentrism and it was his strong...

, one of the figureheads of the democratic left was arrested, court-martialled and executed by shooting on 9 November, ignoring his parliamentary immunity

Parliamentary immunity

Parliamentary immunity, also known as legislative immunity, is a system in which members of the parliament or legislature are granted partial immunity from prosecution. Before prosecuting, it is necessary that the immunity be removed, usually by a superior court of justice or by the parliament itself...

. This highlighted the powerlessness of the National Assembly and its dependence on the goodwill of the governments of the individual states of the German Confederation. In Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany

Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany

Revolution and Counter-Revolution in Germany is a book by Friedrich Engels, with contributions by Karl Marx. The book was written as a "series of articles about Germany from 1848 onwards." The project was first suggested to Karl Marx by Charles Dana, one of the editors of the New York Daily...

(1852), Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels was a German industrialist, social scientist, author, political theorist, philosopher, and father of Marxist theory, alongside Karl Marx. In 1845 he published The Condition of the Working Class in England, based on personal observations and research...

wrote:

- "The fact that fate of the revolution was decided in Vienna and Berlin, that the key issues of life were dealt with in both those capitals without taking the slightest notice of the Frankfurt assembly - that fact alone is sufficient to prove that the institution was a mere debating club, consisting of an accumulation of gullible wretches who alowed themselves to be abused as puppets by the governments, so as to provide a show to amuse the shopkeepers and tradesmen of small states and towns, as long as it was considered necessary to distract their attention."

The execution also indicated that the force of the March Revolution was beginning to flag by the autumn of 1848. This did not apply only to Austria. The power of the governments appointed in March was eroding. In Prussia, the Prussian National Assembly was disbanded and its draft constitution rejected.

Greater German or Smaller German solution

The definition of the national unity of German was a major difficulty for the Frankfurt National Assembly. Schleswig's natural affiliation was a smaller problem. The biggest problem was that large portions of the two most powerful states in the German Confederacy, Prussia and especially Austria, had large possessions outside the confederation with non-German populations. Incorporating such areas into a German nation-state did not only raise questions regarding the national identity of their inhabitants, but also regarding power politics between the German states. On the other hand, BohemiaBohemia

Bohemia is a historical region in central Europe, occupying the western two-thirds of the traditional Czech Lands. It is located in the contemporary Czech Republic with its capital in Prague...

and Moravia

Moravia

Moravia is a historical region in Central Europe in the east of the Czech Republic, and one of the former Czech lands, together with Bohemia and Silesia. It takes its name from the Morava River which rises in the northwest of the region...

were to remain within the confederation, in spite of large non-German populations and Czech efforts to the opposite. Similarly, the delegates decided to incorporate the Prussian Province of Posen

Province of Posen

The Province of Posen was a province of Prussia from 1848–1918 and as such part of the German Empire from 1871 to 1918. The area was about 29,000 km2....

, against the wishes of the Polish

Poles

thumb|right|180px|The state flag of [[Poland]] as used by Polish government and diplomatic authoritiesThe Polish people, or Poles , are a nation indigenous to Poland. They are united by the Polish language, which belongs to the historical Lechitic subgroup of West Slavic languages of Central Europe...

population.

The borders of the future German nation-state had only two possibilities: The Kleindeutsche Lösung ("Smaller German Solution") aimed for a Germany under the leadership of Prussia and excluding imperial Austria, so as to avoid becoming embroiled in the problems of that multi-cultural state. The supporters of the Großdeutsche Lösung ("Greater German Solution"), however, supported Austria's incorporation. Some of those deputies expected the integration of all the Habsburg monarchy

Habsburg Monarchy

The Habsburg Monarchy covered the territories ruled by the junior Austrian branch of the House of Habsburg , and then by the successor House of Habsburg-Lorraine , between 1526 and 1867/1918. The Imperial capital was Vienna, except from 1583 to 1611, when it was moved to Prague...

's territories, while other Greater German supporters called for a variant only including areas settled by Germans within a German state.

While the majority of the radical left voted for the Greater German variant, accepting the possibility, as formulated by Carl Vogt of a "holy war for western culture against the barbarism of the East", i.e., against Poland and Hungary, whereas the liberal centre supported a more pragmatic stance. On 27 October 1848, the National Assembly voted for a Greater German Solution, but incorporating only "Austria's German lands".

The Austrian emperor Ferdinand I

Ferdinand I of Austria

Ferdinand I was Emperor of Austria, President of the German Confederation, King of Hungary and Bohemia , as well as associated dominions from the death of his father, Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor, until his abdication after the Revolutions of 1848.He married Maria Anna of Savoy, the sixth child...

was, however, not willing to break up his state. On 27 November 1848, only a few days before the coronation of his successor, Franz Joseph I

Franz Joseph I of Austria

Franz Joseph I or Francis Joseph I was Emperor of Austria, King of Bohemia, King of Croatia, Apostolic King of Hungary, King of Galicia and Lodomeria and Grand Duke of Cracow from 1848 until his death in 1916.In the December of 1848, Emperor Ferdinand I of Austria abdicated the throne as part of...

, he had his Prime Minister Schwarzenberg declare the indivisibility of Austria. Thus, it became clear that, at most, the National Assembly could achieve national unity within the smaller German solution, with Prussia as the sole major power. Although Schwarzenberg demanded the incorporation of the whole of Austria into the new state once more in March 1849, the dice had fallen in favour of a Smaller German Empire by December 1848, when the irreconcilable differences between the position of Austria and that of the National Assembly had forced the Austrian, Schmerling, to resign from his role as Ministerpräsident of the provisional government. He was succeeded by Heinrich von Gagern.

Nonetheless, the Paulskirche Constitution was designed to allow a later accession of Austria, by referring to the territories of the German Confederation and formulating special arrangements for states with German and non-German areas. The allocation of votes in the Staatenhaus (§ 87 ) also allowed for a later Austrian entry.

Imperial constitution and basic rights

Paulskirchenverfassung

The Constitution of the German Empire of 1849, more commonly known as the Frankfurt Constitution or Paulskirchenverfassung , was an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to created a unified German state under an Emperor...

("Imperial Constitution

Imperial Constitution

Imperial Constitution can refer to:* Germany's Paulskirchenverfassung* Japan's Meiji Constitution...

"). It could make use of the preparatory work done by the Committee of Seventeen appointed earlier by the Bundesversammlung.

On December 28, the Assembly's press organ, the Reichsgesetzblatt published the Reichsgesetz betreffend die Grundrechte des deutschen Volkes ("Imperial law regarding the basic rights of the German people") of 27 December 1848, declaring the basic rights as immediately applicable.

The catalogue of basic rights included Freedom of Movement

Freedom of movement

Freedom of movement, mobility rights or the right to travel is a human right concept that the constitutions of numerous states respect...

, Equal Treatment

Egalitarianism

Egalitarianism is a trend of thought that favors equality of some sort among moral agents, whether persons or animals. Emphasis is placed upon the fact that equality contains the idea of equity of quality...

for all Germans in all of Germany, the abolishment of class-based privileges and medieval burdens, Freedom of Religion

Freedom of religion

Freedom of religion is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance; the concept is generally recognized also to include the freedom to change religion or not to follow any...

, Freedom of Conscience, the abolishment of capital punishment

Capital punishment

Capital punishment, the death penalty, or execution is the sentence of death upon a person by the state as a punishment for an offence. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally...

, Freedom of Research and Education

Academic freedom

Academic freedom is the belief that the freedom of inquiry by students and faculty members is essential to the mission of the academy, and that scholars should have freedom to teach or communicate ideas or facts without being targeted for repression, job loss, or imprisonment.Academic freedom is a...

, Freedom of Assembly

Freedom of assembly

Freedom of assembly, sometimes used interchangeably with the freedom of association, is the individual right to come together and collectively express, promote, pursue and defend common interests...

, basic rights in regard to police activity and judicial proceedings, the inviolability of the home, Freedom of the Press

Freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the freedom of communication and expression through vehicles including various electronic media and published materials...

, independence of judges, Freedom of Trade

Free trade

Under a free trade policy, prices emerge from supply and demand, and are the sole determinant of resource allocation. 'Free' trade differs from other forms of trade policy where the allocation of goods and services among trading countries are determined by price strategies that may differ from...

and Freedom of establishment.

After long and controversial negotiations, the parliament passed the complete Imperial Constitution on March 28, 1849. It was carried narrowly, by 267 against 263 votes. The version passed included the creation of a hereditary emperor

Hereditary monarchy

A hereditary monarchy is the most common type of monarchy and is the form that is used by almost all of the world's existing monarchies.Under a hereditary monarchy, all the monarchs come from the same family, and the crown is passed down from one member to another member of the family...

(Erbkaisertum), which had been favoured mainly by the erbkaiserliche group around Gagern, with the reluctant support of the Westendhall group around Heinrich Simon. On the first reading, such a solution had been dismissed. The change of mind came about because all alternative suggestions, such as an elective monarchy

Elective monarchy

An elective monarchy is a monarchy ruled by an elected rather than hereditary monarch. The manner of election, the nature of the candidacy and the electors vary from case to case...

, or a Directory government

Directory (political)

A Directorial Republic is a country ruled by a College of several people which jointly exercise the powers of Head of State. This system of government is in contrast both with presidential republics and parliamentary republics. In political history, the term Directory, in French Directoire, applies...

under an alternating chair were even less practicable and unable to find broad support, as was the radical left's demand for a republic

Republic

A republic is a form of government in which the people, or some significant portion of them, have supreme control over the government and where offices of state are elected or chosen by elected people. In modern times, a common simplified definition of a republic is a government where the head of...

, modelled on the United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

.

The people were to be represented by a bicameral parliament, with a directly elected Volkshaus and a Staatenhaus of representatives sent by the individual confederated states. Half of each Staatenhaus delegation was to be appointed by the respective state government, the other by the state parliament.

Head of state and Kaiserdeputation

As the near-inevitable result of having chosen the Smaller German Solution and the constitutional monarchy as form of government, the Prussian king was elected as hereditary head of state on March 28, 1849. The vote was carried by 290 votes against 248 abstentions, embodying resistance primarily by all left-wing, southern German and Austrian deputies. The deputies knew that Frederick William IVFrederick William IV of Prussia

|align=right|Upon his accession, he toned down the reactionary policies enacted by his father, easing press censorship and promising to enact a constitution at some point, but he refused to enact a popular legislative assembly, preferring to work with the aristocracy through "united committees" of...

held strong prejudices against the work of the Frankfurt Parliament, but on January 23, the Prussian government had informed the states of the German Confederation that Prussia would accept the idea of a hereditary emperor.

Further, Prussia, unlike Bavaria, Württemberg, Saxony and Hanover, had indicated its support of the draft constitution in a statement made after the first reading. Additionally, the representatives of the provisional government had attempted through innumerable meetings and talks to build an alliance with the Prussian government, especially by creating a common front against the radical left and by arguing that the monarchy could only survive if it accepted a constitutional-parliamentary system. The November 1848 discussion of Bassermann and Hergenhahn with Friedrich Wilhelm IV were also aiming in the same direction.

On April 3, 1849, the Kaiserdeputation ("Emperor Deputation"), a group of deputies chosen by the National Assembly, offered Friedrich Wilhelm the office of emperor. He declined, arguing that he could not accept the crown without the agreement of the princes and Free Cities. In reality, Friedrich Wilhelm insisted in the principle of the Divine Right of Kings

Divine Right of Kings

The divine right of kings or divine-right theory of kingship is a political and religious doctrine of royal and political legitimacy. It asserts that a monarch is subject to no earthly authority, deriving his right to rule directly from the will of God...

and thus did not want to accept a crown touched by "the hussy smell of revolution". This spelled the final failure of the Frankfurt Parliament's constitution and thus of the German March revolution. The rejection of the crown was understood by the other princes as a signal that the political scales had tipped against the liberals. Mainly smaller states accepted the constitution reluctantly, Württemberg was the only kingdom to do so after much hesitation.

Rump parliament and dissolution

On April 5, 1849, all Austrian deputies left Frankfurt. On the 14th of May, the Prussian parliamentarians also resigned their mandates. The new elections called for by von Gagern did not take place, further weakening the assembly. In the following week, nearly all conservative and bourgeois-liberal deputies left the parliament. The remaining left-wing forces insisted that 28 states had accepted the Frankfurt Constitution and began the Reichsverfassungskampagne, an all-out call for resistance against the existing governments, escalating the political situation. The supporters of the campaign did not consider themselves revolutionaries. From their perspective, they represented a legitimate national executive power acting against states that had breached the constitution. Nonetheless, only the radical democratic left was willing to use force to support the constitution, notwithstanding their original reservations against it. In view of their failure, the bourgeoisie and the leading liberal politicians of the faction of the Halbe ("half ones") rejected a renewed revolution and withdrew - most of them disappointed - from their hard work in the Frankfurt Parliament.

In the meantime, the Reichsverfassungskampagne had not achieved any success regarding acceptance of the constitution, but had managed to mobilize those elements of the population that were willing to support a revolution. In Saxony, this led to the May Uprising in Dresden

May Uprising in Dresden

The May Uprising took place in Dresden, Germany in 1849; it was one of the last of the series of events known as the Revolutions of 1848.-Events leading to the May Uprising:...

, in the Bavarian part of the Rhenish Palatinate to the Pfälzer Aufstand, a rising during which revolutionaries gained the de facto governmental power. On May 14, the Grandduke of Baden, Leopold

Leopold, Grand Duke of Baden

Leopold I, Grand Duke of Baden succeeded in 1830 as the fourth Grand Duke of Baden....

had to flee the country after a mutiny of the Rastatt garrison. The insurrectionists declared a Baden Republic and formed a revolutionary government headed by the Paulskirche deputy Lorenz Brentano. Together with Baden soldiers that had joined their side, they formed an army under the leadership of the Polish general Mieroslawski. While the Prussian military, under orders from the German Confederation, began to crush the revolutionary troops, the Prussian government prepared the expulsion of the remaining deputies from the Free City of Frankfurt

Free City of Frankfurt

For almost five centuries, the German city of Frankfurt am Main was a city-state within two major Germanic states:*The Holy Roman Empire as the Free Imperial City of Frankfurt...

in late May. Further deputies that were not willing to align with radical democratic left resigned their mandates or gave them up when asked to by their home governments. On May 26, the Frankfurt National Assembly had to lower its quorum

Quorum

A quorum is the minimum number of members of a deliberative assembly necessary to conduct the business of that group...

to a mere hundred due to the enduring low presence of deputies. The remaining deputies decided to escape the Prussian sphere of influence by moving the parliament to Stuttgart

Stuttgart

Stuttgart is the capital of the state of Baden-Württemberg in southern Germany. The sixth-largest city in Germany, Stuttgart has a population of 600,038 while the metropolitan area has a population of 5.3 million ....

in Württemberg on May 31. This had been suggested by the deputy Friedrich Römer, who was also prime minister and minister of justice of the Württemberg government. Essentially, the Frankfurt National Assembly was dissolved at this point. From June 6, 1849 onwards, the remaining 154 deputies met at Stuttgart. This convention was dismissively called the Rumpfparlament ("rump parliament

Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament is the name of the English Parliament after Colonel Pride purged the Long Parliament on 6 December 1648 of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason....

").