History of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1648)

Encyclopedia

History of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1648) covers a period in the history of Poland

and Lithuania

, before their joint state was subjected to devastating wars in the middle of the 17th century. The Union of Lublin

of 1569 established the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a more closely unified

federal state, replacing the previously existing personal union

of the two countries. The Union was largely run by the Polish and Polonized

Lithuanian and Ruthenia

n nobility

, through the system of the central parliament

and local assemblies

, but from 1573 led by elected kings

.

The beginning of the Commonwealth coincided with the period of Poland's great power, civilizational advancement and prosperity. The Polish–Lithuanian Union had become an influential player in Europe and a vital cultural entity, spreading the Western culture

eastward. In the second half of the 16th and the first half of the 17th century, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was a huge state in central-eastern Europe, with an area approaching one million square kilometers.

Following the Reformation

gains (the Warsaw Confederation

of 1573 was the culmination of the unique in Europe religious toleration

processes), the Catholic Church embarked on an ideological counter-offensive and Counter-Reformation

claimed many converts from Protestant

circles. The disagreements over and the difficulties with the assimilation of the eastern Ruthenian populations of the Commonwealth had become clearly discernible. At an earlier stage (from the late 16th century), they manifested themselves in the religious Union of Brest

, which split the Eastern Christians

of the Commonwealth, and on the military front, in a series of Cossack uprisings

.

The Commonwealth, assertive militarily under King Stephen Báthory, suffered from dynastic distractions during the reigns of the Vasa

kings Sigismund III

and Władysław IV

. It had also become a playground of internal conflicts, in which the kings, powerful magnates and factions of nobility were the main actors. The Commonwealth fought wars with Russia

, Sweden and the Ottoman Empire

. At the Commonwealth's height, some of its powerful neighbors experienced difficulties of their own and the Polish-Lithuanian state sought domination in Eastern Europe, in particular over Russia

. Allied with the Habsburg Monarchy

, it did not directly participate in the Thirty Years' War

.

Tsar Ivan IV of Russia undertook in 1577 hostilities in the Livonia

n region, which resulted in his takeover of most of the area and caused the Polish-Lithuanian involvement in the Livonian War

. The successful counter-offensive led by King Báthory and Jan Zamoyski

resulted in the peace of 1582 and the retaking of much of the territory contested with Russia, with the Swedish forces establishing themselves in the far north (Estonia

). Estonia was declared a part of the Commonwealth by Sigismund III in 1600, which gave rise to a war with Sweden

over Livonia; the war lasted until 1611 without producing a definite outcome.

In 1600, as Russia was entering a period of instability

, the Commonwealth proposed a union with the Russian state. This failed move was followed by many other similarly unsuccessful, often adventurous attempts, some involving military invasions, other dynastic and diplomatic manipulations and scheming. While the differences between the two societies and empires proved in the end too formidable to overcome, the Polish-Lithuanian state ended up in 1619, after the Truce of Deulino

, with the greatest ever expansion of its territory. At the same time it was weakened by the huge military effort made.

In 1620 the Ottoman Empire under Sultan

Osman II

declared a war against the Commonwealth. At the disastrous Battle of Ţuţora

Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski was killed and the Commonwealth's situation in respect to the Turkish-Tatar

invasion forces became very precarious. A mobilization in Poland-Lithuania followed and when Hetman Jan Karol Chodkiewicz

's army withstood fierce enemy assaults at the Battle of Khotyn (1621)

, the situation improved on the southeastern front. More warfare with the Ottomans followed in 1633–1634 and vast expanses of the Commonwealth had been subjected to Tatar incursions and slave-taking expeditions throughout the period.

War with Sweden, now under Gustavus Adolphus

, resumed in 1621 with his attack on Riga

, followed by the Swedish occupation of much of Livonia, control of Baltic Sea

coast up to Puck

and the blockade of Danzig. The Commonwealth, exhausted by the warfare that had taken place elsewhere, in 1626–1627 mustered a response

, utilizing the military talents of Hetman Stanisław Koniecpolski and help from Austria

. Under pressure from several European powers, the campaign was stopped and ended in the Truce of Altmark

, leaving in Swedish hands much of what Gustavus Adolphus had conquered.

Another war with Russia

followed in 1632 and was concluded without much change in the status quo. King Władysław IV

then proceeded to recover the lands lost to Sweden. At the conclusion of the hostilities, Sweden evacuated the cities and ports of Royal Prussia

but kept most of Livonia. Courland

, which had remained with the Commonwealth, assumed the servicing of Lithuania's Baltic trade. After Frederick William's last Prussian homage

before the Polish king

in 1641, the Commonwealth's position in regard to Prussia and its Hohenzollern

rulers kept getting weaker.

At the outset of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, in the second half of the 16th century, Poland-Lithuania became an elective monarchy

At the outset of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, in the second half of the 16th century, Poland-Lithuania became an elective monarchy

, in which the king was elected by the hereditary nobility

. This king would serve as the monarch until he died, at which time the country would have another election.

In 1572, Sigismund II Augustus

, the last king of the Jagiellon dynasty

, died without any heirs. The political system was not prepared for this eventuality, as there was no method of choosing a new king. After much debate it was determined that the entire nobility of Poland and Lithuania would decide who the king was to be. The nobility were to gather at Wola, near Warsaw, to vote in the royal election.

The election of Polish kings lasted until the Partitions of Poland

. The elected kings in chronological order were: Henry of Valois

, Anna Jagiellon

, Stephen Báthory, Sigismund III Vasa

, Władysław IV

, John II Casimir

, Michael Korybut Wiśniowiecki, John III Sobieski

, Augustus II the Strong

, Stanisław Leszczyński, Augustus III

and Stanisław August Poniatowski.

The first Polish royal election was held in 1573. The four men running for the office were Henry of Valois

The first Polish royal election was held in 1573. The four men running for the office were Henry of Valois

, who was the brother of King Charles IX of France

, Tsar

Ivan IV of Russia

, Archduke Ernest of Austria

, and King John III of Sweden

. Henry of Valois ended up a winner. But after serving as the Polish king for only four months, he received the news that his brother, the King of France, had died. Henry of Valois then abandoned his Polish post and went back to France, where he succeeded to the throne as Henry III of France

.

A few of the elected kings left a lasting mark in the Commonwealth. Stephen Báthory was determined to reassert the deteriorated royal prerogative, at the cost of alienating the powerful noble families. Sigismund III, Władysław IV and John Casimir were all of the Swedish

House of Vasa

; preoccupation with foreign and dynastic affairs prevented them from making a major contribution to the stability of Poland-Lithuania. John III Sobieski

commanded the allied Relief of Vienna

operation in 1683, which turned out to be the last great victory of the "Republic of Both Nations". Stanisław August Poniatowski, the last of the Polish kings, was a controversial figure. On the one hand he was a driving force behind the substantial and constructive reforms belatedly undertaken by the Commonwealth. On the other, by his weakness and lack of resolve, especially in dealing with imperial Russia

, he doomed the reforms together with the country they were supposed to help.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, following the Union of Lublin

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, following the Union of Lublin

, became a counterpoint to the absolute monarchies

gaining power in Europe. Its quasi-democratic political system of Golden Liberty

, albeit limited to nobility, was mostly unprecedented in the history of Europe

. In itself, it constituted a fundamental precedent for the later development of European constitutional monarchies.

However the series of power struggles between the lesser nobility (szlachta

), the higher nobility (magnate

s), and elected kings, undermined citizenship values and gradually eroded the government's authority, ability to function and provide for national defense. The infamous liberum veto

procedure was used to paralyze parliamentary proceedings beginning in the second half of the 17th century. After the series of devastating wars in the middle of the 17th century (most notably the Chmielnicki Uprising and the Deluge), Poland-Lithuania stopped being an influential player in the politics of Europe. During the wars the Commonwealth lost an estimated 1/3 of its population (higher losses than during World War II). Its economy and growth were further damaged by the nobility's reliance on agriculture

and serfdom

, which, combined with the weakness of the urban burgher

class, delayed the industrialization of the country.

By the beginning of the 18th century, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, one of the largest and most populous European states, was little more than a pawn of its neighbors (the Russian Empire

, Prussia

and Austria

), who interfered in its domestic politics almost at will. In the second half of the 18th century, the Commonwealth was repeatedly partitioned

by the neighboring powers and ceased to exist.

, initially present in Western Europe. The negative consequences of this process on folwark

economies of the East

had reached its culmination in the second half of the 17th century. Further economic aggravation resulted from Europe-wide devaluation

of the currency around 1620, caused by the influx of silver from the Western Hemisphere

. At that time however massive amounts of Polish grain were still exported through Danzig (Gdańsk)

. The Commonwealth nobility took a variety of steps to combat the crisis and keep up high production levels, burdening in particular the serfs

with further heavy obligations. The nobles were also forcibly buying or taking over properties of the more affluent thus far peasant categories, a phenomenon especially pronounced from the mid 17th century.

Capital

and energy of urban enterprisers

affected the development of mining and metallurgy during the earlier Commonwealth period. There were several hundred hammersmith

shops at the turn of the 17th century. Great ironworks

furnaces were built in the first half of that century. Mining and metallurgy of silver, copper and lead had also been developed. Expansion of salt production was taking place in Wieliczka

, Bochnia

and elsewhere. After about 1700 some of the industrial enterprises were increasingly being taken over by land owners who used serf labor, which led to their neglect and decline in the second half of the 17th century.

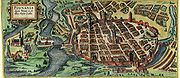

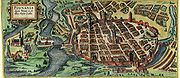

Danzig had remained practically autonomous and adamant about protecting its status and foreign trade monopoly. The Karnkowski Statutes of 1570 gave Polish kings the control over maritime commerce, but not even Stephen Báthory, who resorted to an armed intervention against the city, was able to enforce them. Other Polish cities held steady and prosperous through the first half of the 17th century. War disasters in the middle of that century devastated the urban classes.

A rigid social separation legal system, intended to prevent any inter-class mobility, matured around the first half of the 17th century. But the nobility's goal of becoming self-contained and impermeable to newcomers had never been fully realized, as in practice even peasants on occasions acquired the noble status. Later numerous Polish szlachta

clans had had such "illegitimate" beginnings. Szlachta found justification for their self-appointed dominant role in a peculiar set of attitudes, known as sarmatism

, that they had adopted.

The Union of Lublin

The Union of Lublin

accelerated the process of massive Polonization

of Lithuanian and Rus'

elites and general nobility in Lithuania and the eastern borderlands, the process that retarded national development of local populations there. In 1563 Sigismund Augustus

belatedly allowed the Eastern Orthodox

Lithuanian nobility access to highest offices in the Duchy

, but by that time the act was of little practical consequence, as there were few Orthodox nobles of any standing left and the encroaching Catholic Counter-Reformation

would soon nullify the gains. Many magnate families of the East were of Ruthenia

n origin; their inclusion in the enlarged Crown made the magnate class much stronger politically and economically. Regular szlachta, increasingly dominated by the great land owners, lacked the will to align themselves with Cossack settlers in Ukraine

to counterbalance the magnate power, and in the area of Cossack acceptance, integration and rights resorted to delayed and ineffective half-measures. The peasantry was being subjected to heavier burdens and more oppression. For those reasons, the way in which the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth expansion took place and developed had caused an aggravation of both the social and national tensions, introduced a fundamental instability into the system, and ultimately resulted in the future crises of the "Republic of Nobles".

minorities

) szlachta

of the Commonwealth for the most part returned to the Roman Catholic religion, or if already Catholic remained Catholic, in the course of the 17th century.

Already the Sandomierz Agreement

of 1570, which was an early expression of Protestant

irenicism

later prominent in Europe and Poland, had a self-defensive character, because of the intensification of Counter-Reformation

pressure at that time. The agreement strengthened the Protestant position and made the Warsaw Confederation

religious freedom guarantees in 1573 possible.

At the heyday of Reformation in the Commonwealth, at the end of the 16th century, there were about one thousand Protestant congregations

, nearly half of them Calvinist

. A half century later only 50% of them had survived, with the burgher Lutheranism

suffering lesser losses, the szlachta dominated Calvinism and Nontrinitarianism

(Polish Brethren

) the greatest. The closing of the Brethren Racovian Academy

and a printing facility in Raków on charges of blasphemy

in 1638 forewarned of more trouble to come.

This Counter-Reformation offensive happened somewhat mysteriously in a country, where there were no religious wars and the state had not cooperated with the Catholic Church in eradicating or limiting competing denominations. Among the factors responsible, the low Protestant involvement among the masses, especially of peasantry, the pro-Catholic position of the kings, the low level of involvement of the nobility once the religious emancipation had been accomplished, the internal divisions of the Protestant movement, and the rising intensity of the Catholic Church propaganda, have been listed.

This Counter-Reformation offensive happened somewhat mysteriously in a country, where there were no religious wars and the state had not cooperated with the Catholic Church in eradicating or limiting competing denominations. Among the factors responsible, the low Protestant involvement among the masses, especially of peasantry, the pro-Catholic position of the kings, the low level of involvement of the nobility once the religious emancipation had been accomplished, the internal divisions of the Protestant movement, and the rising intensity of the Catholic Church propaganda, have been listed.

The ideological war between the Protestant and Catholic camps at first enriched the intellectual life of the Commonwealth. The Catholic Church responded to the challenges with internal reform, following the directions of the Council of Trent

, officially accepted by the Polish Church in 1577, but implemented not until after 1589 and throughout the 17th century. There were earlier efforts of reform, originating from the lower clergy, and from about 1551 by Bishop Stanisław Hozjusz

of Warmia

, a lone at that time among the Church hierarchy, but ardent reformer. At the turn of the 17th century a number of Rome educated bishops took over the Church administration at the diocese

level, clergy discipline was implemented and rapid intensification of Counter-Reformation activities took place.

Hozjusz brought to Poland the Jesuits

Hozjusz brought to Poland the Jesuits

and founded for them a college

in Braniewo

in 1564. Numerous Jesuit educational institutions and residencies were established in the following decades, most often in the vicinity of centers of Protestant activity. Jesuit priests were carefully selected, well educated, of both noble and urban origins. They had soon become highly influential with the royal court, while working hard within all segments of the society. The Jesuit educational programs and Counter-Reformation propaganda utilized many innovative media techniques, often custom-tailored for a particular audience on hand, as well as time-tried methods of humanist

instruction. Preacher Piotr Skarga

and Bible translator Jakub Wujek

count among prominent Jesuit personalities.

Catholic efforts to win the population countered the Protestant idea of a national church with Polonization, or nationalization of the Catholic Church in the Commonwealth, introducing a variety of native elements to make it more accessible and attractive to the masses. The Church hierarchy went along with the notion. The changes that took place during the 17th century defined the character of Polish Catholicism for centuries to come.

The apex of the Counter-Reformation activity had fallen on the turn of the 17th century, the earlier years of the reign of Sigismund III Vasa

(Zygmunt III Waza), who in cooperation with the Jesuits and some other Church circles attempted to strengthen the power of his monarchy. The King tried to limit access to higher offices to Catholics. Anti-Protestant riots took place in some cities. During the Sandomierz Rebellion of 1606 the Protestants supported the anti-King opposition in large numbers. Nevertheless the massive wave of szlachta's return to Catholicism could not have been stopped.

Although attempts were made during common Protestant-Orthodox congregations in Toruń

in 1595 and in Vilnius

in 1599, the failure of the Protestant movement to form an alliance with the Eastern Orthodox

Christians, the inhabitants of the eastern portion of the Commonwealth, contributed to the Protestants' downfall. The Polish Catholic establishment would not miss the opportunity to form a union with the Orthodox, although their goal was rather the subjugation of the Eastern Rite Christians to the pope (the papacy solicited help in bringing the "schism

" under control) and the Commonwealth's Catholic centers of power. The Orthodox establishment was perceived as a security threat, because of the Eastern Rite bishops dependence on the Patriarchate of Constantinople

at the time of an aggravating conflict with the Ottoman Empire

, and because of the recent development, the establishment in 1589 of the Moscow Patriarchate

. The Patriarchate of Moscow then claimed ecclesiastical jurisdiction over the Orthodox Christians of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which to many of them was a worrisome development, motivating them to accept the alternate option of union with the West

. The union idea had the support of King Sigismund III

and the Polish nobility in the east; opinions were divided among the church and lay leaders of the Eastern Orthodox faith.

The Union of Brest

act was negotiated and solemnly concluded in 1595–1596. It had not merged the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox denominations, but led to the establishment of the Slavic Rite Uniate Church

, which was to become an Eastern Catholic Church, one of the Greek Catholic Church

es (Ukrainian Greek Catholic

). The new church, of the Byzantine Rite

, accepted papal supremacy, while it retained in most respects its Eastern Rite

character. The compromise union was flawed from the beginning, as despite the initial agreement the Greek-Catholic bishops were not, like their Roman Catholic counterparts, seated in the Senate, and to their disappointment the Eastern Rite participants of the union had not been granted full equality in general.

The Union of Brest increased antagonisms among the Belarusian

The Union of Brest increased antagonisms among the Belarusian

and Ukrainian

communities of the Commonwealth, within which the Orthodox Church had remained the most potent religious force. It added to the already prominent ethnic and class fragmentation and became one more reason for internal infighting that was to impair the Republic. The Eastern Orthodox nobility, branded "Disuniates" and deprived of legal standing, led by Konstanty Ostrogski

commenced a fight for their rights. Prince Ostrogski had been a leader of an Orthodox intellectual revival in Polish Ukraine. In 1576 he founded an elite liberal arts secondary and academic school, the Ostroh Academy

, with trilingual instruction; in 1581 he and his academy were instrumental in the publication of the Ostroh Bible

, the Bible's first scholarly Orthodox Church Slavonic edition. A a result of the efforts, parliamentary statutes of 1607, 1609 and 1635 recognized the Orthodox religion again, as one of the two equal Eastern churches. The restoration of Orthodox hierarchy and administrative structure proved difficult (most bishops had become Uniates, and their Orthodox replacements of 1620 and 1621 were not recognized by the Commonwealth) and was officially done during the reign of Władysław IV

. By that time many of the Orthodox nobles had become Catholics, and the Orthodox leadership fell into the hands of townspeople and lesser nobility organized into church brotherhoods, and the new power in the East, the Cossack warrior class. Metropolitan

Peter Mogila of Kiev

, who organized an influential academy there, contributed greatly to the rebuilding and reform of the Orthodox Church.

The Baroque

The Baroque

style dominated the Polish culture from the 1580s, building on the achievements of the Renaissance

and for a while coexisting with it, to the mid 18th century. Initially Baroque artists and intellectuals, torn between the two competing views of the world, enjoyed wide latitude and freedom of expression. Soon however the Counter-Reformation

instituted a binding point of view that invoked the medieval

tradition, imposed censorship in education and elsewhere (the index

of prohibited books in Poland from 1617), and straightened out their convoluted ways. By the middle of the 17th century the doctrine had been firmly reestablished, sarmatism

and religious zealotry had become the norm. Artistic tastes of the epoch were often acquiring an increasingly Orient

al character. In contrast with the integrative tendencies of the previous period, the burgher and nobility cultural spheres went their separate ways. Renaissance publicist Stanisław Orzechowski had already provided the foundations for Baroque szlachta's political thinking.

At that time there were about forty Jesuit

colleges (secondary schools) scattered throughout the Commonwealth. They were educating mostly szlachta

, burgher sons to a lesser degree. Jan Zamoyski

, Chancellor

of the Crown, who built the town of Zamość

, established an academy

there in 1594; it had functioned as a gymnasium

only after Zamoyski's death. The first two Vasa

kings were well known for patronizing both the arts and sciences. After that the Commonwealth's science experienced general decline, which paralleled the wartime decline of the burgher class.

By the mid 16th century Poland's university, the Academy of Kraków

By the mid 16th century Poland's university, the Academy of Kraków

, entered a crisis stage, and by the early 17th century regressed into Counter-reformation

al conformism. The Jesuits took advantage of the infighting and established in 1579 a university college in Vilnius

, but their efforts aimed at taking over the Academy were unsuccessful. Under the circumstances many elected to pursue their studies abroad. Jan Brożek

, a rector of the Kraków University, was a multidisciplinary scholar who worked on number theory

and promoted Copernicus

' work. He was banned by the Church in 1616 and his anti-Jesuit pamphlet was publicly burned. Brożek's co-worker, Stanisław Pudłowski, worked on a system of measurement

s based on physical phenomena.

Michał Sędziwój (Sendivogius Polonus) was a famous in Europe alchemist

, who wrote a number of treatises in several languages, beginning with Novum Lumen Chymicum (1604, with over fifty editions and translations in the 17th and 18th centuries). A member of Emperor Rudolph II

's circle of scientists and sages, he is believed by some authorities to have been a pioneer chemist

and a discoverer of oxygen

, long before Lavoisier

(Sendivogius' works were studied by leading scientists, including Isaac Newton

).

The early Baroque period produced a number of noted poets. Sebastian Grabowiecki wrote metaphysical

and mystical

religious poetry representing the passive current of Quietism

. Another szlachta poet Samuel Twardowski

participated in military and other historic events; among the genres he pursued was epic poetry

. Urban poetry was quite vital until the middle of the 17th century; the plebeian poets criticized the existing social order and continued within the ambiance of elements of the Renaissance style. The creations of John of Kijany contained a hearty dose of social radicalism. The moralist Sebastian Klonowic

wrote a symbolic poem Flis using the setting of Vistula river craft floating work. Szymon Szymonowic

in his Pastorals portrayed, without embellishments, the hardships of serf life. Maciej Sarbiewski

, a Jesuit, was highly appreciated throughout Europe for the Latin

poetry he wrote.

The preeminent prose of the period was written by Piotr Skarga

The preeminent prose of the period was written by Piotr Skarga

, the preacher-orator. In his Sejm Sermons Skarga severely criticized the nobility and the state, while expressing his support for a system based on strong monarchy. Writing of memoirs had become most highly developed in the 17th century. Peregrination to the Holy Land by Mikołaj Radziwiłł and Beginning and Progress of the Muscovy War written by Stanisław Żółkiewski, one of the greatest Polish military commanders, are the best known examples.

One form of art particularly apt for Baroque purposes was the theater. Various theatrical shows were most often staged in conjunction with religious occasions and moralizing, and commonly utilized folk stylization. School theaters had become common among both the Protestant and Catholic secondary schools. A permanent court theater with an orchestra was established by Władysław IV

at the Royal Castle

in Warsaw

in 1637; the actor troupe, dominated by Italians, performed primarily Italian opera and ballet repertoire.

Music, both sacral and secular, kept developing during the Baroque period. High quality church pipe organ

s were built in churches from the 17th century; a fine specimen has been preserved in Leżajsk

. Sigismund III

supported an internationally renowned ensemble of sixty musicians. Working with that orchestra were Adam Jarzębski

and his contemporary Marcin Mielczewski

, chief composers of the courts of Sigismund III and Władysław IV. Jan Aleksander Gorczyn, a royal secretary, published in 1647 a popular music tutorial for beginners.

Martin Kober, a court painter from Wrocław, worked for Stephen Báthory and Sigismund III; he produced a number of well-known royal portraits.

Between 1580 and 1600 Jan Zamoyski

commissioned the Venetian architect Bernardo Morando

to build the city of Zamość

. The town and its fortifications were designed to consistently implement the Renaissance and Mannerism

aesthetic paradigms.

Mannerism is the name sometimes given to the period in art history during which the late Renaissance coexisted with the early Baroque, in Poland the last quarter of the 16th century and the first quarter of the 17th century. Polish art remained influenced by the Italian centers, increasingly Rome, and increasingly by the art of the Netherlands

. As a fusion of imported and local elements, it evolved into an original Polish form of the Baroque.

The Baroque art was developing to a great extent under the patronage of the Catholic Church, which utilized the art to facilitate religious influence, allocating for this purpose the very substantial financial resources at its disposal. The most important in this context art form was architecture, with features rather austere at first, accompanied in due time by progressively more elaborate and lavish facade and interior design concepts.

Beginning in the 1580s, a number of churches patterned after the Church of the Gesù

Beginning in the 1580s, a number of churches patterned after the Church of the Gesù

in Rome had been built. Gothic

and other older churches were increasingly being supplemented with Baroque style architectural additions, sculptures, wall paintings and other ornaments, which is conspicuous in many Polish churches today. The Royal Castle in Warsaw

, after 1596 the main residence of the monarchs, was enlarged and rebuilt around 1611. The Ujazdów Castle

(1620s) of the Polish kings turned out to be architecturally more influential, its design having been followed by a number of Baroque magnate residencies.

The role of Baroque sculpture was usually subordinate, as decorative elements of exteriors and interiors, and on tombstones. A famous exception is the Sigismund's Column

of Sigismund III Vasa

(1644) in front of Warsaw's Royal Castle.

Realistic religious painting, sometimes entire series of related works, served its didactic purpose. Nudity and mythological

themes were banned, but other than that fancy collection of Western paintings were in vogue. Sigismund III brought from Venice

Tommaso Dolabella

. A prolific painter, he was to spend the rest of his life in Kraków

and give rise to a school of Polish painters working under his influence. Danzig (Gdańsk)

was also a center for graphic

arts; painters Herman Han and Bartholomäus Strobel worked there, and so did Willem Hondius

and Jeremias Falck

, who were engravers

.

During the first half of the 17th century Poland was still a leading Central European power in the area of culture. As compared with the previous century, even wider circles of the society participated in cultural activities, but Catholic Counter-Reformation pressure resulted in diminished diversity. Catastrophic wars in the middle of the century greatly weakened the Commonwealth's cultural development and influence in the region.

After the Union of Lublin

After the Union of Lublin

, the Senate

of the General Sejm

of the Commonwealth became augmented by Lithuanian high officials; the position of the lay and ecclesiastical lords, who served for life as members of the Senate was strengthened, as the already outnumbered middle szlachta

high office holders had now proportionally fewer representatives in the upper chamber. The Senate could also be convened separately by the king in its traditional capacity of the royal council, apart from any sejm's formal deliberations, and szlachta's attempts to limit the upper chamber's role had not been successful. After the formal union and the addition of deputies from the Grand Duchy

, and Royal Prussia

, also more fully integrated with the Crown in 1569, there were about 170 regional deputies in the lower chamber (referred to as the Sejm) and 140 senators.

Sejm deputies doing legislative work were generally not able to act as they pleased. Regional szlachta assemblies, the sejmik

s, were summoned before sessions of the General Sejm; there the local nobility provided their representatives with copious instructions on how to proceed and protect the interests of the area involved. Another sejmik was called after the General Sejm's conclusion. At that time the deputies would report to their constituency on what had been accomplished.

Sejmiks had become an important part of the Commonwealth's parliamentary life, complementing the role of the General Sejm. They sometimes provided detailed implementations for general proclamations of the sejms, or made legislative decisions during periods when the sejm was not in session, at times communicating directly with the monarch.

There was little significant parliamentary representation for the burgher class, and none for the peasants. The Jewish communities sent representatives to their own Va'ad, or Council of Four Lands

. The narrow social base of the Commonwealth's parliamentary system was detrimental to its future development and the future of the Polish-Lithuanian statehood.

From 1573 an "ordinary" General Sejm was to be convened every two years, for a period of six weeks. A king could summon an "extraordinary" sejm for two weeks, as necessitated by circumstances; an extraordinary sejm could be prolonged if the parliamentarians assented. After the Union the Sejm of the Republic deliberated in more centrally located Warsaw, except that Kraków had remained the location of Coronation Sejms. The turn of the 17th century brought also a permanent migration of the royal court from Kraków to Warsaw.

The order of sejm proceedings was formalized in the 17th century. The lower chamber would do most of the statute preparation work. The last several days were spent working together with the Senate and the king, when the final versions were agreed upon and decisions made; the finished legislative product had to have the consent of all three legislating estates of the realm, the Sejm, the Senate, and the monarch. The lower chamber's rule of unanimity had not been rigorously enforced during the first half of the 17th century.

The order of sejm proceedings was formalized in the 17th century. The lower chamber would do most of the statute preparation work. The last several days were spent working together with the Senate and the king, when the final versions were agreed upon and decisions made; the finished legislative product had to have the consent of all three legislating estates of the realm, the Sejm, the Senate, and the monarch. The lower chamber's rule of unanimity had not been rigorously enforced during the first half of the 17th century.

General Sejm was the highest organ of collective and consensus-based state power. The sejm's supreme court, presided over by the king, decided the most serious of legal cases. During the second half of the 17th century, for a variety of reasons, including abuse of the unanimity rule (liberum veto

), General Sejm's effectiveness had declined, and the void was being increasingly filled by the sejmiks, where in practice the bulk of government's work was getting done.

The system of noble democracy became more firmly rooted during the first interregnum

The system of noble democracy became more firmly rooted during the first interregnum

, after the death of Sigismund II Augustus

, who following the Union of Lublin wanted to reassert his personal power, rather than become an executor of szlachta's will. A lack of agreement concerning the method and timing of the election of his successor was one of the casualties of the situation, and the conflict strengthened the Senate-magnate camp. After the monarch's 1572 death, to protect its common interests, szlachta moved to establish territorial confederations

(kapturs) as provincial governments, through which public order was protected and basic court system provided. The magnates were able to push through their candidacy for the interrex

or regent

to hold the office until a new king is sworn, in the person of the primate

, Jakub Uchański

. The Senate took over the election preparations. The establishment's proposition of universal szlachta participation (rather than election by the Sejm) appeared at that time to be the right idea to most szlachta factions; in reality, during this first as well as subsequent elections, the magnates subordinated and directed, especially the poorer of szlachta.

During the interregnum the szlachta prepared a set of rules and limitations for the future monarch to obey as a safeguard to ensure that the new king, who was going to be a foreigner, complied with the peculiarities of the Commonwealth's political system and respected the privileges of the nobility. As Henry of Valois

During the interregnum the szlachta prepared a set of rules and limitations for the future monarch to obey as a safeguard to ensure that the new king, who was going to be a foreigner, complied with the peculiarities of the Commonwealth's political system and respected the privileges of the nobility. As Henry of Valois

was the first one to sign the rules, they became known as the Henrician Articles

. The articles also specified the wolna elekcja (free election) as the only way for any monarch's successor to assume the office, thus precluding any possibility of hereditary monarchy in the future. The Henrician Articles summarized the accumulated rights of Polish nobility, including religious freedom guarantees, and introduced further restrictions on the elective king; as if that were not enough, Henry also signed the so-called pacta conventa

, through which he accepted additional specific obligations. Newly crowned Henry soon embarked on a course of action intended to free him from all the encumbrances imposed, but the outcome of this power struggle was never to be determined. One year after the election, in June 1574, upon learning of his brother's

death, Henry secretly left for France.

In 1575 the nobility commenced a new election process. The magnates tried to force the candidacy of Emperor Maximilian II

In 1575 the nobility commenced a new election process. The magnates tried to force the candidacy of Emperor Maximilian II

, and on 12 December Archbishop Uchański even announced his election. This effort was thwarted by the execution movement

szlachta party led by Mikołaj Sienicki and Jan Zamoyski

; their choice was Stephen Báthory, Prince of Transylvania

. Sienicki quickly arranged for a 15 December proclamation of Anna Jagiellon

, sister of Sigismund Augustus, as the reigning queen, with Stefan Batory added as her husband and king jure uxoris

. Szlachta's pospolite ruszenie

supported the selection with their arms. Batory took over Kraków, where the couple's crowning ceremony took place on 1 May 1576.

Stephen Báthory's reign marks the end of szlachta's reform movement. The foreign king was skeptical of the Polish parliamentary system and had little appreciation for what the execution movement activists had been trying to accomplish. Batory's relations with Sienicki soon deteriorated, while other szlachta leaders had advanced within the nobility ranks, becoming senators or being otherwise preoccupied with their own careers. The reformers managed to move in 1578 in Poland and in 1581 in Lithuania the out-of-date appellate court system from the monarch's domain to the Crown and Lithuanian Tribunals run by the nobility. The cumbersome sejm and sejmiks system, the ad hoc confederations

, and the lack of efficient mechanisms for the implementation of the laws escaped the reformers' attention or will to persevere. Many thought that the glorified nobility rule had approached perfection.

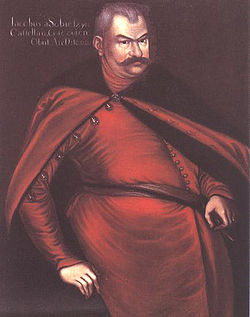

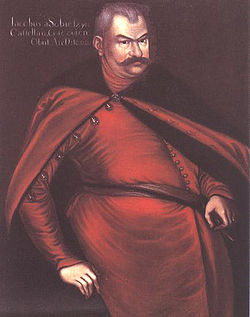

Jan Zamoyski

Jan Zamoyski

, one of the most distinguished personalities of the period, became the king's principal adviser and manager. A highly educated and cultivated individual, talented military chief and accomplished politician, he had often promoted himself as a tribune of his fellow szlachta. In fact in a typical magnate manner, Zamoyski accumulated multiple offices and royal land grants, removing himself far from the reform movement ideals he professed earlier.

The king himself was a great military leader and far-sighted politician. Of Batory's confrontations with members of the nobility, the famous case involved the Zborowski brothers: Samuel

was executed on Zamoyski's orders, Krzysztof was sentenced to banishment

and property confiscation by the sejm court. A Hungarian, like other foreign rulers of Poland, Batory was concerned with the affairs of the country of his origin. Batory failed to enforce the Karnkowski's Statutes and therefore was unable to control the foreign trade through Danzig (Gdańsk)

, which was to have highly negative economic and political consequences for the Republic. In cooperation with his chancellor

and later hetman

Jan Zamoyski, he was largely successful in the Livonia

n war. At that time the Commonwealth was able to increase the magnitude of its military effort: The combined for a campaign armed forces from several sources available could be up to 60,000 men strong. King Batory initiated the creation of piechota wybraniecka

, an important peasant infantry military formation.

In 1577 Batory agreed to George Frederick

of Brandenburg

becoming a custodian for the mentally ill Albert Frederick

, Duke of Prussia, which brought the two German polities closer together, to the detriment of the Commonwealth's long-term interests.

King Sigismund Augustus'

King Sigismund Augustus'

Dominium Maris Baltici program, aimed at securing Poland's access to and control over the portion of the Baltic

region and ports that the country had vital interests in protecting, led to the Commonwealth's participation in the Livonian conflict

, which had also become another stage in the series of Lithuania's and Poland's confrontations with Russia. In 1563 Ivan IV

took Polotsk. After the Stettin peace of 1570 (which involved several powers, including Sweden and Denmark) the Commonwealth remained in control of the main part of Livonia, including Riga

and Pernau

. In 1577 Ivan undertook a great expedition, taking over for himself, or his vassal

Magnus, Duke of Holstein most of Livonia, except for the coastal areas of Riga and Reval

. A success of the Polish-Lithuanian counter-offensive became possible as Batory was able to secure the necessary funding from the nobility.

The Polish forces recovered Dünaburg

and most of middle Livonia. The King and Zamoyski then opted for attacking directly the inland Russian territory necessary for keeping Russian communication lines to Livonia open and functioning. Polotsk was retaken in 1579 and the Velikiye Łuki fortress fell in 1580. The take-over of Pskov

was attempted in 1581, but Ivan Petrovich Shuisky

was able to defend the city despite a several months long siege. An armistice was arranged in 1582 by the papal legate

Antonio Possevino

. The Russians evacuated all the Livonian castles they had captured, gave up the Polotsk area and left Velizh

in Lithuanian hands. The Swedish forces, which took over Narva

and most of Estonia

, contributed to the victory. The Commonwealth ended up with the possession of the continuous Baltic coast from Puck

to Pernau

.

There were several candidates for the Commonwealth crown considered after the death of Stephen Báthory, including Archduke Maximilian of Austria. Anna Jagiellon

There were several candidates for the Commonwealth crown considered after the death of Stephen Báthory, including Archduke Maximilian of Austria. Anna Jagiellon

proposed and pushed for the election of her nephew Sigismund Vasa

, son of John III, King of Sweden

and Catherine Jagellon and the Swedish heir apparent

. The Zamoyski

faction supported Sigismund, the faction led by the Zborowski family wanted Maximilian; two separate elections took place and a civil war resulted. The Habsburg's army entered Poland and attacked Kraków, but was repulsed there and then, while retreating in Silesia

, crushed by the forces organized by Jan Zamoyski at the Battle of Byczyna

(1588), where Maximilian was taken prisoner.

In the meantime Sigismund also arrived and was crowned in Kraków, which initiated his long in the Commonwealth (1587–1632) reign as Zygmunt III Waza

. The prospect of a personal union

with Sweden raised for the Polish and Lithuanian ruling circles political and economic hopes, including favorable Baltic

trade conditions and a common front against Russia's

expansion. However concerning the latter, the control of Estonia

had soon become the bone of contention. Sigismund's ultra-Catholicism appeared threatening to the Swedish Protestant

establishment and contributed to his dethronement in Sweden in 1599.

Inclined to form an alliance with the Habsburgs (and even give up the Polish crown to pursue his ambitions in Sweden), Sigismund conducted secret negotiations with them and married Archduchess Anna. Accused by Zamoyski of breaking his covenants, Sigismund III was humiliated during the sejm

of 1592, which deepened his resentment of szlachta

. Sigismund was bent on strengthening the power of the monarchy and Counter-Reformation

al promotion of the Catholic Church (Piotr Skarga

was among his supporters). Indifferent to the increasingly common breaches of the Warsaw Confederation

religious protections and instances of violence against the Protestants

, the King was opposed by religious minorities.

1605–1607 brought fruitless confrontation between King Sigismund with his supporters and the coalition of opposition nobility. During the sejm of 1605 the royal court proposed a fundamental reform of the body itself, an adoption of the majority rule instead of the traditional practice of unanimous acclamation by all deputies present. Jan Zamoyski

in his last public address reduced himself to a defense of szlachta prerogatives, thus setting the stage for the demagoguery that was to dominate the Commonwealth's political culture for many decades.

For the sejm of 1606 the royal faction, hoping to take advantage of the glorious Battle of Kircholm

victory and other successes, submitted a more comprehensive constructive reform program. Instead the sejm had become preoccupied with the dissident

postulate of prosecuting instigators of religious disturbances directed against non-Catholics; advised by Skarga

, the King refused his assent to the proposed statute.

The nobility opposition, suspecting an attempt against their liberties, called for a rokosz

, or an armed confederation

. Tens of thousands of disaffected szlachta, led by the ultra-Catholic Mikołaj Zebrzydowski and Calvinist

Janusz Radziwiłł, congregated in August near Sandomierz

, giving rise to the so-called Zebrzydowski Rebellion.

The Sandomierz articles produced by the rebels were concerned mostly with placing further limitations on the monarch's power. Threatened by royal forces under Stanisław Żółkiewski, the confederates entered into an agreement with Sigismund, but then backed out of it and demanded the King's deposition. The ensuing civil war was resolved at the Battle of Guzów

, where the szlachta was defeated in 1607. Afterwards however magnate leaders of the pro-King faction made sure that Sigismund's position would remain precarious, leaving arbitration powers within the Senate's competence. Whatever was left of the execution movement

had become thwarted together with the obstructionist szlachta elements, and a compromise solution to the crisis of authority was arrived at. But the victorious lords of the council had at their disposal no effective political machinery necessary to propagate the well-being of the Commonwealth, still in its Golden Age

(or as some prefer Silver Age now), much further.

In 1611 John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg

was allowed by the Commonwealth sejm to inherit the Duchy of Prussia fief

, after the death of Albert Frederick

, the last duke of the Prussian Hohenzollern

line. The Brandenburg Hohenzollern branch led the Duchy from 1618.

The reforms of the execution movement had clearly established the sejm as the central and dominant organ of state power. But this situation in reality had not lasted very long, as various destructive decentralizing tendencies, steps taken by the szlachta and the kings, were progressively undermining and eroding the functionality and primacy of the central legislative organ. The resulting void was being filled during the late 16th and 17th centuries by the increasingly active and assertive territorial sejmik

The reforms of the execution movement had clearly established the sejm as the central and dominant organ of state power. But this situation in reality had not lasted very long, as various destructive decentralizing tendencies, steps taken by the szlachta and the kings, were progressively undermining and eroding the functionality and primacy of the central legislative organ. The resulting void was being filled during the late 16th and 17th centuries by the increasingly active and assertive territorial sejmik

s, which provided a more accessible and direct forum for szlachta activists to promote their narrowly conceived local interests. The sejmiks established effective controls, in practice limiting the sejm's authority; themselves they were taking on an ever broader range of state matters and local issues.

In addition to the destabilizing to the central authority role of the over 70 sejmiks, during the same period, the often unpaid army had begun establishing their own "confederations", or rebellions. By plunder and terror they attempted to recover their compensation and pursue other, sometimes political aims.

Some reforms were being pursued by the more enlightened szlachta, who wanted to expand the role of the sejm at the monarch's and magnate faction's expense, and by the elected kings. Sigismund III during the later part of his rule constructively cooperated with the sejm, making sure that between 1616 and 1632 each session of the body produced the badly needed statutes. The increased efforts in the areas of taxation and maintenance of the military forces made possible the positive outcomes of some of the armed conflicts that took place during Sigismund's reign.

had become incorporated into the Polish armed forces already around that time. During the reign of Sigismund III Vasa

the Cossack problem was beginning to play its role as Rzeczpospolita's preeminent internal challenge of the 17th century.

The Cossacks were first semi-nomadic, then also settled Slavic

people of the Dnieper River

area, who practiced brigandage and plunder, and, renowned for their fighting prowess, early in their history assumed a military organization. Many of them were or originated from run-away peasants from eastern and other areas of the Commonwealth or from Russia

; other significant elements were townspeople and even nobility, who came from the region or migrated into Ukraine

. The Cossacks considered themselves free and independent of any bondage and followed their own elected leaders, who originated from the more affluent strata of their society. There were tens of thousands of Cossacks already early in the 17th century. They had frequently clashed with the neighboring Turks

and Tatars

and raided their Black Sea

coastal settlements.

Many Cossacks were being hired

to participate in wars waged by the Commonwealth. This status resulted in privileges and often constituted a form of social upward mobility

; the Cossacks resented the periodic reductions in their enrollment. The Cossack rebellions or uprisings typically assumed the form of huge plebeian

social movements.

The Ottoman Empire

demanded a total liquidation of the Cossack power. The Commonwealth however needed the Cossacks in the south-east, where they provided an effective buffer against Crimean Tatars

incursions. The other way to quell the Cossack unrest would be to grant nobility status to a substantial portion of their population and thus assimilate them into the Commonwealth's power structure. This solution was being rejected by the magnates and szlachta for political, economic and cultural reasons when there was still time for reform, before disasters struck. The Polish-Lithuanian establishment had instead shifted unsteadily between compromising with the Cossacks, allowing limited numbers, the so-called Cossack register

(500 in 1582, 8000 in the 1630s), to serve with the Commonwealth army (the rest were to be converted into serfdom

, to help the magnates in colonizing the Dnieper area), and brutally using military force in an attempt to subdue them.

Efforts to subjugate and exploit economically the Cossack territories and population in Zaporizhia region

resulted in a series of Cossack uprisings

, of which the early ones could have served as a warning for the szlachta

legislators.

In 1591 the bloodily suppressed Kosiński Uprising

was led by Krzysztof Kosiński

. New fighting took place already in 1594, when the Nalyvaiko Uprising

engulfed large portions of Ukraine and Belarus

. Hetman

Stanisław Żółkiewski defeated the Cossack units in 1596 and Severyn Nalyvaiko

was executed. A temporary pacification of relations followed in the early 17th century, when the many wars fought by the Commonwealth necessitated greater involvement by registered Cossacks

. The Union of Brest

however resulted in new tensions, as the Cossacks had become dedicated adherents and defenders of the Eastern Orthodoxy.

The uprising of Marko Zhmailo of 1625 was confronted by Stanisław Koniecpolski and concluded with Mykhailo Doroshenko

signing the Treaty of Kurukove

. More fighting soon erupted and culminated in the "Taras night" of 1630, when the Cossack rebels under Taras Fedorovych

turned against army units and noble estates. The Fedorovych Uprising

was put under control by Hetman Koniecpolski. These events were followed by an increase in the Cossack registry (Treaty of Pereyaslav

), but then rejection of demands by Cossack elders during the convocation sejm of 1632, who wanted to participate in free elections as members of the Commonwealth and have religious rights of the "disuniate

" Eastern Christians restored. The 1635 sejm

voted instead further restrictions and authorized the construction of the Dnieper Kodak Fortress

, to facilitate more effective control over the Cossack territories. Another round of fighting, the Pavluk Uprising

followed in 1637–1638. It was defeated and its leader Pavel Mikhnovych

executed. Upon new anti-Cossack limitations and sejm statutes imposing serfdom on most Cossacks, the Cossacks rose up again in 1638 under Jakiv Ostryanin and Dmytro Hunia

. The uprising was cruelly suppressed and the existing Cossack land properties were taken over by the magnates. The harsh measures restored relative calm for a short period, while the Cossack affair, perceived as a weak spot of the Commonwealth, was increasingly becoming an issue in international politics.

Władysław IV Vasa

Władysław IV Vasa

, son of Sigismund III, ruled the Commonwealth during 1632–1648. Born and raised in Poland, prepared for the office from the early years, popular, educated, free of his father's religious prejudices, he seemed a promising chief executive candidate. Władysław however, like his father, had the life ambition of attaining the Swedish

throne by using his royal status and power in Poland and Lithuania, which, to serve his purpose, he attempted to strengthen. Władysław ruled with the help of several prominent magnates, among them Jerzy Ossoliński

, Chancellor of the Crown

, Hetman

Stanisław Koniecpolski, and Jakub Sobieski

, the middle szlachta

leader. Władysław IV was unable to attract a wider szlachta following, and many of his plans had foundered because of lack of support in the increasingly ineffectual sejm

. Because of his tolerance for non-Catholics, Władysław was also opposed by the Catholic clergy and the papacy.

Toward the last years of his reign Władysław IV sought to enhance his position and assure his son's succession by waging a war on the Ottoman Empire

, for which he prepared, despite the lack of nobility support. To secure this end the King worked on forming an alliance with the Cossacks, whom he encouraged to improve their military readiness and intended to use against the Turks, moving in that direction of cooperation further than his predecessors. The war never took place, and the King had to explain his offensive war designs during the "inquisition" sejm of 1646. Władysław's son Zygmunt Kazimierz died in 1647, and the King, weakened, resigned and disappointed, in 1648.

The turn of the 16th and 17th centuries brought changes that, for the time being, weakened the Commonwealth's powerful neighbors (The Tsardom of Russia

The turn of the 16th and 17th centuries brought changes that, for the time being, weakened the Commonwealth's powerful neighbors (The Tsardom of Russia

, The Austrian Habsburg Monarchy

and the Ottoman Empire

). The resulting opportunity for the Polish-Lithuanian state to improve its position depended on its ability to overcome internal distractions, such as the isolationist and pacifist tendencies that prevailed among the szlachta

ruling class, or the rivalry between nobility leaders and elected kings, often intent on circumventing restrictions on their authority, such as the Henrician Articles

.

The nearly continuous wars of the first three decades of the new century resulted in modernization, if not (because of the treasury limitations) enlargement, of the Commonwealth's army. The total military forces available ranged from a few thousands at the Battle of Kircholm

, to the over fifty thousands plus pospolite ruszenie

mobilized for the Khotyn (Chocim) campaign

of 1621. The remarkable during the first half of the 17th century development of artillery

resulted in the 1650 publication in Amsterdam

of the Artis Magnae Artilleriae pars prima book by Kazimierz Siemienowicz

, a pioneer also in the science of rocket

ry. Despite the superior quality of the Commonwealth's heavy (hussar

) and light (Cossack) cavalry, the increasing proportions of the infantry (peasant, mercenary and Cossack formations) and of the contingent of foreign troops resulted in an army, in which these respective components were heavily represented. During the reigns of the first two Vasas

a war fleet was developed and fought successful naval battles (1609 against Sweden). As usual, fiscal difficulties impaired the effectiveness of the military, and the treasury's ability to pay the soldiers.

As a continuation of the earlier plans for an anti-Turkish offensive, that had not materialized because of the death of Stefan Batory, Jan Zamoyski

As a continuation of the earlier plans for an anti-Turkish offensive, that had not materialized because of the death of Stefan Batory, Jan Zamoyski

intervened in Moldavia

in 1595. With the backing of the Commonwealth army Ieremia Movilă

assumed the hospodar

's throne as the Commonwealth's vassal

. Zamoyski's army repelled the subsequent assault by the Ottoman Empire

forces at Ţuţora. The next confrontation in the area took place in 1600, when Zamoyski and Stanisław Żółkiewski acted against Michael the Brave, hospodar of Wallachia

and Transylvania

. First Ieremia Movilă, who in the meantime had been removed by Michael in Moldavia, was reimposed, and then Michael was defeated in Wallachia at the Battle of Bucov

. Ieremia's brother Simion Movilă

became the new hospodar there and for a brief period the entire region up to the Danube

had become the Commonwealth's dependency. Turkey soon reasserted its role, in 1601 in Wallachia and in 1606 in Transylvania. Zamoyski's politics and actions, which constituted the earlier stage of the Moldavian magnate wars

, only prolonged Poland's influence in Moldavia and interfered effectively with the simultaneous Habsburg

plans and ambitions in this part of Europe. Further military involvement at the southern frontiers ceased being feasible, as the forces were needed more urgently in the north.

crowning in Sweden took place in 1594 amid tensions and instability caused by religious controversies. As Sigismund returned to Poland, his uncle Charles

, the regent

, took the lead of the anti-Sigismund Swedish opposition. In 1598 Sigismund attempted to resolve the matter militarily

, but the expedition to the country of his origin was defeated at the Battle of Linköping

; Sigismund was taken prisoner and had to agree to the harsh conditions imposed. After his return to Poland, in 1599 the Riksdag of the Estates

deposed him in Sweden, and Charles led the Swedish forces into Estonia

. Sigismund in 1600 proclaimed the incorporation of Estonia into the Commonwealth, which was tantamount to a declaration of war on Sweden

, at the height of Rzeczpospolita's involvement in Moldavia region.

Jürgen von Farensbach

Jürgen von Farensbach

, given the command of the Commonwealth forces, was overpowered by the much larger army brought to the area by Charles, whose quick offensive resulted in the 1600 take-over of most of Livonia

up to the Daugava River, except for Riga

. The Swedes were welcomed by much of the local population, by that time increasingly dissatisfied with the Polish-Lithuanian rule. in 1601 Krzysztof Radziwiłł succeeded at the Battle of Kokenhausen

, but the Swedish advances had been reversed up to (not including) Reval

, only after Jan Zamoyski brought in a more substantial force. Much of this army, having been unpaid, returned to Poland. The clearing action was continued by Jan Karol Chodkiewicz

, who, with a small contingent of troops left, defeated the Swedish incursion at Paide

(Biały Kamień) in 1604.

In 1605 Charles, now Charles IX

, the King of Sweden, launched a new offensive, but his efforts were crossed by Chodkiewicz's victories at Kircholm

and elsewhere and the Polish naval successes, while the war continued without a decisive resolution being produced. In the armistice of 1611 the Commonwealth was able to keep the majority of the contested areas, as a variety of internal and foreign difficulties, including the inability to pay the mercenary soldiers and the Union's new involvement in Russia, precluded a comprehensive victory.

After the deaths of Ivan IV

After the deaths of Ivan IV

and in 1598 of his son Feodor

, the last tsar

s of the Rurik Dynasty

, Russia

entered a period of severe dynastic, economic and social crisis and instability

. As Boris Godunov

encountered resistance from both the peasant masses and the boyar

opposition, in the Commonwealth the ideas of turning Russia into a subordinated ally, either through a union, or an imposition of a ruler dependent on the Polish-Lithuanian establishment, were rapidly coming into play.

In 1600 Lew Sapieha

led a Commonwealth mission to Moscow to propose a union with the Russian state, patterned after the Polish-Lithuanian Union

, with the boyars granted rights comparable with those of the Commonwealth's nobility. A decision on a single monarch was to be postponed until the death of the current king or tsar. Boris Godunov, at that time also engaged in negotiations with Charles

of Sweden, wasn't interested in that close a relationship and only a twenty-year truce was agreed upon.

In order to continue their efforts, the magnates took advantage of the death of Tsarevich Dmitry under mysterious circumstances and of the appearance of False Dmitriy I

, a pretender-impostor claiming to be the tsarevich. False Dmitriy was able to secure the cooperation and help of the Wiśniowiecki family and of Jerzy Mniszech

, Voivode of Sandomierz

, whom he promised vast Russian estates and a marriage with the voivode's daughter Marina

. Dmitriy became a Catholic and leading an army of adventurers raised in the Commonwealth, with the tacit support of Sigismund III

entered in 1604 the Russian state. After the death of Boris Godunov and the murder of his son Feodor

, False Dmitriy I became the Tsar of Russia, and remained in that capacity until killed during a popular turmoil in 1606.

Russia under the new tsar Vasili Shuisky

remained unstable. A new false Dmitriy materialized and Tsaritsa Marina

had even "recognized" in him her thought-to-be-dead husband. With a new army provided largely by the magnates of the Commonwealth, False Dmitriy II approached Moscow and made futile attempts to take the city. Tsar Vasili IV

, seeking help from King Charles IX of Sweden

, agreed to territorial concessions in Sweden's favor and in 1609 the Russo-Swedish anti-Dmitriy and anti-Commonwealth alliance was able to remove the threat from Moscow and strengthen Vasili. The alliance and the Swedish involvement in Russian affairs caused a direct military intervention on the part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, instigated and led by King Sigismund III.

The Polish army commenced a siege of Smolensk

and the Russo-Swedish relief expedition was defeated in 1610 by Hetman Żółkiewski at the Battle of Klushino

. The victory strengthened the position of the compromise-oriented Russian boyar

faction, which had already been interested in offering the Moscow throne to Władysław Vasa

, son of Sigismund III. Under arrangements negotiated by Żółkiewski, the boyars deposed Tsar Vasili

and accepted Władysław in return for peace, no annexation of Russia into the Commonwealth, the Prince's conversion to the Orthodox

religion, and privileges, including exclusive rights to high offices in the Tsardom

granted to the Russian nobility. After the agreement was signed the Commonwealth forces entered the Kremlin

.

Sigismund III subsequently rejected the compromise solution and demanded the tsar's throne for himself, which would mean complete subjugation of Russia, and as such was rejected by the bulk of the Russian society. Sigismund's refusal and demands only intensified the chaos, as the Swedes proposed their own candidate and took over Veliki Novgorod. The result was the 1611 popular Russian anti-Polish uprising and a siege of the Polish garrison occupying the Kremlin.

In the meantime the Commonwealth forces after a long siege stormed and took Smolensk

in 1611. At the Kremlin the situation of the Poles had been worsening despite occasional reinforcements, and the massive national and religious uprising was spreading all over Russia. A new rescue operation attempted by Hetman Chodkiewicz

failed and a capitulation of the Polish and Lithuanian forces at the Kremlin became necessary. Mikhail Romanov, son of the imprisoned in Poland Patriarch Filaret

, became the new tsar in 1613.

The war effort, debilitated by a rebellious confederation established by the unpaid military, was continued. Turkey

The war effort, debilitated by a rebellious confederation established by the unpaid military, was continued. Turkey

, threatened by the Polish territorial gains became involved at the frontiers, and a peace between Russia and Sweden was agreed to in 1617. Fearing the new alliance the Commonwealth undertook one more major expedition, which took over Vyazma

and arrived at the walls of Moscow, in an attempt to impose the rule of Władysław Vasa

again. The city would not open its gates and not enough military strength was brought in to attempt a forced take-over.

Despite the disappointment, the Commonwealth was able to take advantage of the Russian weakness and through the territorial advances accomplished to reverse the eastern losses suffered in the earlier decades. In the Truce of Deulino

of 1619 the Rzeczpospolita was granted the Smolensk

, Chernihiv

and Novhorod-Siverskyi

regions.

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth attained its greatest geographic extent, but the attempted union with Russia could not have been achieved, as the systemic, cultural and religious incompatibilities between the two empires proved to be insurmountable. The territorial annexations and the ruthlessly conducted wars left a legacy of injustice suffered and desire for revenge on the part of the Russian ruling classes and people. The huge military effort weakened the Commonwealth and the painful consequences of the adventurous policies of the Vasa court and its allied magnates were soon to be felt.

In 1613 Sigismund III Vasa

In 1613 Sigismund III Vasa

reached an understanding with Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor

, based on which both sides agreed to cooperate and mutually provide assistance in suppressing internal rebellions. The pact neutralized the Habsburg Monarchy

in regard to the Commonwealth's war with Russia, but had resulted in more serious consequences after the Bohemian Revolt

gave rise to the Thirty Years' War

in 1618.

The Czech events weakened the position of the Habsburgs in Silesia

, where there were large concentrations of ethnically

Polish inhabitants, whose ties and interests at that time placed them within the Protestant

camp. Numerous Polish Lutheran

parishes, with schools and centers of cultural activity, had been established in the heavily Polish areas around Opole

and Cieszyn

in eastern Silesia, as well as in numerous cities and towns throughout the region and beyond, including Breslau (Wrocław) and Grünberg (Zielona Góra)

. The threat posed by a potentially resurgent Habsburg monarchy to the situation of Polish Silesians was keenly felt, and there were voices within King Sigismund's circle, including Stanisław Łubieński and Jerzy Zbaraski

, who brought to his attention Poland's historic rights and options in the area. The King, an ardent Catholic, advised by many not to involve the Commonwealth on the Catholic-Habsburg side, decided in the end to act in their support, but unofficially.

The ten thousand men strong Lisowczycy

mercenary division, a highly effective military force, had just returned from the Moscow campaign, and having become a major nuisance for the szlachta

, was available for another assignment abroad; Sigismund sent them south to assist Emperor Ferdinand II

. Sigismund court's intervention greatly influenced the first phase of the war, helping save the position of the Habsburg Monarchy at a critical moment.

The Lisowczycy entered northern Hungary (now Slovakia

) and in 1619 defeated the Transylvania

n forces at the Battle of Humenné

. Prince Bethlen Gábor

of Transylvania, who together with the Czechs had laid siege to Vienna

, had to hurry back to his country and make peace with Ferdinand, which seriously compromised the situation of the Czech insurgents. Afterwards the Lisowczycy ruthlessly fought to suppress the Emperor's opponents in Glatz (Kłodzko) region and elsewhere in Silesia, in Bohemia and Germany.

After the breakdown of the Bohemian Revolt the residents of Silesia, including the Polish gentry in Upper Silesia

, were subjected to severe repressions and Counter-Reformation

al activities, including forced expulsions of thousands of Silesians, many of whom ended up in Poland. Later during the war years the province was repeatedly ravaged in the course of military campaigns crossing its territory, and at one point a Protestant leader, Piast

Duke John Christian of Brieg

, appealed to Władysław IV Vasa

for assuming supremacy over Silesia. King Władysław, although a tolerant ruler including in matters of religion, was like his father

disinclined to involve the Commonwealth in the Thirty Years' War. He ended up getting as fiefs

from the Emperor

the duchies of Opole

and Racibórz

in 1646, twenty years later reclaimed by the Empire. The Peace of Westphalia

allowed the Habsburgs to do as they pleased in Silesia, already completely ruined by the war, which had resulted in intense persecution of Protestants, including the Polish Lower Silesia

communities, forced to emigrate or subjected to Germanization

.

Although the Rzeczpospolita had not formally participated directly in the Thirty Years' War

Although the Rzeczpospolita had not formally participated directly in the Thirty Years' War

, the alliance with the Habsburg Monarchy

contributed to getting Poland involved in new wars with the Ottoman Empire

, Sweden and Russia

, and therefore led to significant Commonwealth influence over the course of the Thirty Years' War. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth also had its own intrinsic reasons for the continuation of struggles with the above powers.

From the 16th century the Commonwealth suffered a series of Tatar invasions. In the 16th century Cossack raids began descending on the Black Sea

area Turkish

settlements and Tatar lands. In retaliation the Ottoman Empire

directed their vassal

Tatar

forces, based in Crimea

or Budjak

areas, against the Commonwealth regions of Podolia

and Red Ruthenia

. The borderland area to the south-east was in a state of semi-permanent warfare until the 18th century. Some researchers estimate that altogether more than 3 million people had been captured and enslaved during the time of the Crimean Khanate

.

The greatest intensity of Cossack raids, reaching as far as Sinop

in Turkey, fell on the 1613–1620 period. The Ukrainian

magnates on their part continued their traditional involvement

in Moldavia

, where they kept trying to install their relatives (the Movileşti family) on the hospodar

's throne (Stefan Potocki in 1607 and 1612, Samuel Korecki

and Michał Wiśniowiecki in 1615). Ottoman chief Iskender Pasha

destroyed the magnate forces in Moldavia and compelled Stanisław Żółkiewski in 1617 to consent to the Treaty of Busza

at Poland's border, in which the Commonwealth obliged not to get involved in matters concerning Wallachia

and Transylvania

.

Turkish unease about Poland's influence in Russia, the consequences of the Lisowczycy

expedition against Transylvania, an Ottoman fief in 1619 and the burning of Varna

by the Cossacks in 1620 caused the Empire under the young Sultan

Osman II

to declare a war against the Commonwealth, with the aim of breaking and conquering the Polish-Lithuanian state.

The actual hostilities, which were to bring the demise of Stanisław Żółkiewski, were initiated by the old Polish hetman

The actual hostilities, which were to bring the demise of Stanisław Żółkiewski, were initiated by the old Polish hetman

. Żółkiewski with Koniecpolski and a rather small force entered Moldavia, hoping for military reinforcements from Moldavian Hospodar Gaspar Graziani

and the Cossacks. The aid had not materialized and the hetmans faced a superior Turkish and Tatar force led by Iskender Pasha. In the aftermath of the failed Battle of Ţuţora (1620)

Żółkiewski was killed, Koniecpolski captured, and the Commonwealth left opened defenseless, but disagreements between the Turkish and Tatar commanders prevented the Ottoman army from immediately waging an effective follow-up.

The sejm

was convened in Warsaw, the royal court was blamed for endangering the country, but high taxes for a sixty thousand men army were agreed to and the number of registered Cossacks

was allowed to reach forty thousand. The Commonwealth forces, led by Jan Karol Chodkiewicz

, were helped by Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny and his Cossacks, who raised against the Turks and Tatars and participated in the upcoming campaign. In practice about 30,000 regular army and 25,000 Cossacks faced at Khotyn

a much larger Ottoman force under Osman II. Fierce Turkish attacks

against the fortified Commonwealth positions lasted throughout September 1621 and were repelled. The exhaustion and depletion of its forces made the Ottoman Empire sign the Treaty of Khotyn

, which had kept the old territorial status quo of Sigismund II

(Dniester

River border between the Commonwealth and Ottoman combatants), a favorable for the Polish side outcome. After Osman II was killed in a coup, ratification of the treaty was obtained from his successor Mustafa I

.