The Canadian Crown and First Nations, Inuit and Métis

Encyclopedia

The association between the Canadian Crown and Aboriginal peoples of Canada

stretches back to the first interactions

between North American indigenous peoples

and Europe

an colonialists and, over centuries of interface, treaties

were established concerning the monarch and aboriginal tribes. Canada's First Nations

, Inuit

, and Métis

peoples now have a unique relationship with the reigning monarch and, like the Māori and the Treaty of Waitangi

in New Zealand

, generally view the affiliation as being not between them and the ever-changing Cabinet

, but instead with the continuous Crown of Canada, as embodied in the reigning sovereign. These agreements with the Crown are administered by Canadian Aboriginal law

and overseen by the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development.

and the Canadian Crown is both statutory and traditional, the treaties being seen by the first peoples both as legal contracts and as perpetual and personal promises by successive reigning kings and queens to protect Aboriginal welfare, define their rights, and reconcile their sovereignty with that of the monarch in Canada. The agreements are formed with the Crown because the monarchy is thought to have inherent stability and continuity, as opposed to the transitory nature of populist whims that rule the political government, meaning the link between monarch and Aboriginals will theoretically last for "as long as the sun shines, grass grows and rivers flow."

The relationship has thus been described as mutual "cooperation will be a cornerstone for partnership between Canada and First Nations, wherein Canada is the short-form reference to Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada" and "special," having a strong sense of "kinship" and possessing familial aspects. Constitutional scholars have observed that First Nations are "strongly supportive of the monarchy

," even if not necessarily regarding the monarch as supreme. The nature of the legal interaction between Canadian sovereign and First Nations has similarly not always been supported.

are those in Canada, which date to the beginning of the 18th century. Today, the main guide for relations between the monarchy and Canadian First Nations is King George III's

Royal Proclamation of 1763

; while not a treaty, it is regarded by First Nations as their Magna Carta

or "Indian Bill of Rights", binding on not only the British Crown

, but the Canadian one as well, as the document remains a part of the Canadian constitution

. The proclamation set parts of the King's North America

n realm aside for colonists and reserved others for the First Nations

, thereby affirming native title to their lands and making clear that, though under the sovereignty

of the Crown, the aboriginal bands were autonomous political units in a "nation-to-nation" association with non-native governments, with the monarch as the intermediary. This created not only a "constitutional and moral basis of alliance" between indigenous Canadians and the Canadian state as personified in the monarch, but also a fiduciary affiliation in which the Crown is constitutionally charged with providing certain guarantees to the First Nations, as affirmed in Sparrow v. The Queen

, meaning that the "honour of the Crown" is at stake in dealings between it and First Nations leaders.

Given the "divided" nature of the Crown

, the sovereign may be party to relations with aboriginal Canadians distinctly within a provincial jurisdiction. This has at times lead to a lack of clarity regarding which of the monarch's jurisdictions should administer his or her duties towards indigenous peoples.

s or other types of ceremony held to mark the anniversary of a particular treaty sometimes with the participation of the monarch, another member of the Canadian Royal Family, or one of the sovereign's representatives or simply an occasion mounted to coincide with the presence of a member of the Royal Family on a royal tour, Aboriginals having always been a part of such tours of Canada. Gifts have been frequently exchanged such as when the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh people's Capilano Indian Community Club of North Vancouver in 1953 gave the Duke of Edinburgh a walking stick

in the form of a totem pole

and Aboriginal titles have been bestowed upon royal and viceroyal figures since the earliest days of contact with the Crown: The Ojibwa

referred to George III as the Great Father and Queen Victoria was later dubbed as the Great White Mother. Queen Elizabeth II was named Mother of all People by the Salish nation

in 1959 and her son, Prince Charles, was in 1976 given by the Inuit the title of Attaniout Ikeneego, meaning Son of the Big Boss. Charles was further honoured in 1986, when Cree

and Ojibwa

students in Winnipeg

named Charles Leading Star, and again in 2001, during the Prince's first visit to Saskatchewan

, when he was named Pisimwa Kamiwohkitahpamikohk, or The Sun Looks at Him in a Good Way, by an elder in a ceremony at Wanuskewin Heritage Park

.

Since as early as 1710, Aboriginal leaders have met to discuss treaty business with Royal Family members or viceroys in private audience and many continue to use their connection to the Crown to further their political aims. The above mentioned pageants and celebrations have, for instance, been employed as a public platform on which to present complaints to the monarch or members of her family. It has been said that Aboriginal people in Canada cherish this ability to do this before the witness of national and international cameras; Innu leader Mary Pia Benuen said in 1997: "The way I see it, she is everybody's queen. It's nice for her to know who the Innu are and why we're fighting for our land claim and self-government all the time."

Since as early as 1710, Aboriginal leaders have met to discuss treaty business with Royal Family members or viceroys in private audience and many continue to use their connection to the Crown to further their political aims. The above mentioned pageants and celebrations have, for instance, been employed as a public platform on which to present complaints to the monarch or members of her family. It has been said that Aboriginal people in Canada cherish this ability to do this before the witness of national and international cameras; Innu leader Mary Pia Benuen said in 1997: "The way I see it, she is everybody's queen. It's nice for her to know who the Innu are and why we're fighting for our land claim and self-government all the time."

Explorers commissioned by French

Explorers commissioned by French

and English

monarchs made contact with North American aboriginals in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. These interactions were generally peaceful the agents of each sovereign seeking the Indians' alliance in wresting territories away from the other monarch and the partnerships were typically secured through treaties, the first signed in 1676. However, the English also used friendly gestures as a vehicle for establishing Crown dealings with aboriginal inhabitants, while simultaneously expanding their domain: as fur trade

rs and outposts of the Hudson's Bay Company

(HBC), a crown corporation founded in 1670, spread westward across the continent, they introduced the concept of a just, paternal monarch to "guide and animate their exertions," to inspire loyalty, and promote peaceful relations. They also brought with them images of the English monarch, such as the medal that bore the effigy

of King Charles II

(founder of the HBC) and which was presented to native chiefs as a mark of distinction; these medallions were passed down through the generations of the chiefs' descendants and those who wore them received particular honour and recognition at HBC posts.

The Great Peace of Montreal

was in 1701 signed by the Governor of New France

, representing King Louis XIV

, and the chiefs of 39 First Nations. Then, in 1710, aboriginal leaders were visiting personally with the British monarch; in that year, Queen Anne

held audience at St. James' Palace

with three Mohawk Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow of the Bear Clan (called Peter Brant, King of Maguas), Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row of the Wolf Clan (called King John of Canojaharie), and Tee Yee Ho Ga Row, or "Double Life", of the Wolf Clan (called King Hendrick

Peters) and one Mahicanin Chief Etow Oh Koam of the Turtle Clan (called Emperor of the Six Nations). The four, dubbed the Four Mohawk Kings, were received in London

as diplomats, being transported through the streets in royal carriages and visiting the Tower of London

and St. Paul's Cathedral. But, their business was to request military aid for defence against the French, as well as missionaries for spiritual guidance. The latter request was passed by Anne to the Archbishop of Canterbury

, Thomas Tenison

, and a chapel was eventually built in 1711 at Fort Hunter, near present day Johnstown, New York

, along with the gift of a reed organ and a set of silver chalice

s in 1712.

Both British and French monarchs viewed their lands in North America as being held by them in totality, including those occupied by First Nations. Typically, the treaties established delineations between territory reserved for colonial settlement and that distinctly for aboriginal use. The French kings, though they did not admit claims by aboriginals to lands in New France, granted the natives reserves for their exclusive use; for instance, from 1716 onwards, land north and west of the manorials

on the Saint Lawrence River

were designated as the pays d'enhaut (upper country), or "Indian country", and were forbidden to settlement and clearing of land without the expressed authorisation of the King. The same was done by the kings of Great Britain; for example, the Treaty of 1725, establishing a relationship between King George III and the "Maeganumbe... tribes Inhabiting His Majesty's Territories," acknowledged the King's title to the provinces of Nova Scotia

and Acadia

in exchange for the guarantee that the indigenous people "not be molested in their persons... by His Majesty's subjects."

The sovereigns also sought alliances with the First Nations; the Iroquois

siding with Georges II and III and the Algonquin with Louis XIV and XV. These arrangements left questions about the treatment of aboriginals in the French territories once the latter were ceded in 1760 to George III. Article 40 of the Capitulation of Montreal

, signed on 8 September 1760, inferred that First Nations peoples who had been subjects of King Louis XV

would then become the same of King George: "The Savages or Indian allies of his most Christian Majesty, shall be maintained in the Lands they inhabit; if they chose to remain there; they shall not be molested on any pretence whatsoever, for having carried arms, and served his most Christian Majesty; they shall have, as well as the French, liberty of religion, and shall keep their missionaries..." Yet, two days before, the Algonquin, along with the Hurons of Lorette and eight other tribes, had already ratified a treaty at Fort Lévis

, making them allied with, and subjects of, the British king, who instructed General the Lord Amherst

to treat the First Nations "upon the same principals of humanity and proper indulgence" as the French, and to "cultivate the best possible harmony and Friendship with the Chiefs of the Indian Tribes." The retention of civil code

in Quebec, though, caused the relations between the Crown and First Nations in that jurisdiction to be viewed as dissimilar to those that existed in the other Canadian colonies.

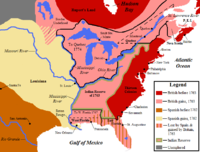

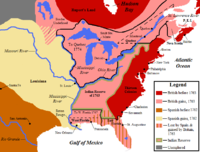

In 1763, George III issued a Royal Proclamation

that acknowledged the First Nations as autonomous political units and affirmed their title to their lands; it became the main document governing the parameters of the relationship between the sovereign and his aboriginal subjects in North America. The King thereafter ordered Sir William Johnson to make the proclamation known to the aboriginal nations under the King's sovereignty and, by 1766, its provisions were already put into practical use: In that year, the Imperial Privy Council endorsed a grant of 20000 acres (80.9 km²) to Joseph Marie Philibot at a location of his choosing, but Philibot's request for land on the Restigouche River

was denied by the Governor of Quebec on the grounds that "the lands so prayed to be assigned are, or are claimed to be, the property of the Indians and as such by His Majesty's express command as set forth in his proclamation in 1763, not within their power to grant." In the prelude to the American Revolution

, native leader Joseph Brant

took the King up on this offer of protection and voyaged to London between 1775 and 1776 to meet with George III in person and discuss the aggressive expansionist policies of the American colonists.

During the course of the American Revolution, First Nations assisted King George III's North American forces, who ultimately lost the conflict. As a result of the Treaty of Paris

During the course of the American Revolution, First Nations assisted King George III's North American forces, who ultimately lost the conflict. As a result of the Treaty of Paris

, signed in 1783 between King George and the American Congress of the Confederation

, British North America was divided into the sovereign United States

(US) and the still British Canadas

, creating a new international border through some of those lands that had been set apart by the Crown for First Nations and completely immersing others within the new republic. As a result, some aboriginal tribes felt betrayed by the King and their service to the monarch was detailed in oratories that called on the Crown to keep its promises, especially after nations that had allied themselves with the British sovereign were driven from their lands by Americans. New treaties were drafted and those indigenous nations that had lost their territories in the United States, or simply wished to not live under the US government, were granted new land in Canada by the King.

The Mohawk Nation

was one such group, which abandoned its Mohawk Valley

territory, in present day New York State, after Americans destroyed the natives' settlement, including the chapel donated by Queen Anne following the visit to London of the Four Mohawk Kings. As compensation, George III promised land in Canada to the Six Nations and, in 1784, some Mohawks settled in what is now the Bay of Quinte

and the Grand River Valley

, where North America's only two Chapels Royal

Christ Church Royal Chapel of the Mohawks

and Her Majesty's Chapel of the Mohawks

were built to symbolise the connection between the Mohawk people and the Crown. Thereafter, the treaties with aboriginals across southern Ontario were dubbed the Covenant Chain

and ensured the preservation of First Nations' rights not provided elsewhere in the Americas.

This treatment encouraged the loyalty of the aboriginal peoples to the sovereign and, as allies of the King, they aided in defending his North American territories, especially during the War of 1812

This treatment encouraged the loyalty of the aboriginal peoples to the sovereign and, as allies of the King, they aided in defending his North American territories, especially during the War of 1812

.

In 1860, during one of the first true royal tours of Canada

, First Nations put on displays, expressed their loyalty to Queen Victoria

and presented concerns about misconduct on the part of the Indian Department to the Queen's son, Prince Albert Edward, Prince of Wales

, when he was in Upper Canada

. In that same year, Nahnebahwequay of the Ojibwa

secured an audience with the Queen. When Governor General the Marquess of Lorne

and his wife, Princess Louise

, a daughter of Queen Victoria, visited British Columbia

in 1882, they were greeted upon arrival in New Westminster by a floatilla of local Aboriginals in canoes who sang songs of welcome before the royal couple landed and proceeded through a ceremonial arch built by Aboriginals, which was hung with a banner reading "Clahowya Queenastenass", Chinookian

for "Welcome Queen." The following day, the Duke and Duchess gave their presence to an event attended by thousands of First Nations people and at least 40 chiefs. One presented the Princess with baskets, a bracelet, and a ring of Aboriginal make and Louise said in response that, when she returned to the United Kingdom, she would show these items to the Queen.

Once the Dominion Crown purchased what remained of Rupert's Land

from the Hudson's Bay Company and colonial settlement expanded westwards, more treaties were signed between 1871 and 1921, wherein the Crown brokered land exchanges that granted the aboriginal societies reserves and other compensation, such as livestock, ammunition, education, health care, and certain rights to hunt and fish. This situation under the Crown was regarded by the First Nations as better than that which had befallen their brethren in the United States. The treaties did not ensure peace: as evidenced by the North-West Rebellion

of 1885, sparked by Métis people's

concerns over their survival and discontent on the part of Cree

people over perceived unfairness in the treaties signed with Queen Victoria.

and Queen Elizabeth

an event intended to express the new independence of Canada and its monarchy First Nations journeyed to city centres like Regina, Saskatchewan

, and Calgary

, Alberta

, to meet with the King and present gifts and other displays of loyalty. In the course of the Second World War

that followed soon after George's tour, more than 3,000 aboriginal and Métis Canadians fought for the Canadian Crown and country, some receiving personal recognition from the King, such as Tommy Prince

, who was presented with the Military Medal

and, on behalf of the President of the United States

, the Silver Star

by the King at Buckingham Palace.

Squamish Nation Chief Joe Mathias was amongst the Canadian dignitaries who were invited to attend the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in London in 1953.

When George's daughter, Queen Elizabeth II, toured Canada twenty years later, similar interactions took place: In Labrador

, Elizabeth was greeted by the Chief of the Montagnais and given a pair of beaded moose-hide jackets; at Gaspé, Quebec

, the Queen and her husband were presented with deerskin coats by two local aboriginal people; and in Ottawa, a man from the Kahnawake Mohawk Territory passed to officials a 200 year old wampum

as a gift for Elizabeth. It was during that journey that the Queen became the first member of the Royal Family to meet with Inuit representatives, doing so in Stratford, Ontario

, and the royal train stopped in Brantford, Ontario

, so that the Queen could sign the Six Nations Queen Anne Bible in the presence of Six Nations leaders. Across the prairies

, First Nations were present on the welcoming platforms in numerous cities and towns, and at the Calgary Stampede

, more than 300 Blackfoot

, Tsuu T'ina

, and Nakoda

performed a war dance

and erected approximately 30 teepees, amongst which the Queen and Duke of Edinburgh walked, meeting with various chiefs. In Nanaimo, British Columbia

, a longer meeting took place between Elizabeth and the Salish

, wherein the latter conferred on the former the title of Mother of all People, and, following a dance of welcome, the Queen and her consort spent 45 minutes 20 more than allotted touring a replica First Nations village and chatting with some 200 people.

In 1970, Elizabeth II's presence at The Pas, Manitoba

, provided an opportunity for the Opaskwayak Cree Nation

to publicly express their perceptions of injustice meted out by the government; three years later, the Queen assured native chiefs in Alberta that "her government recognized the importance of full compliance with the spirit and intent of treaties".

During a royal tour by the Queen in 1973, Harold Cardinal

delivered a politically charged speech to the monarch and the Queen responded; the whole exchange having been pre-approved between the two.

Still, at the same time, aboriginal people were not always granted the personal time with the Queen that they desired; the meetings with First Nations and Inuit tended to be purely ceremonial affairs wherein treaty issues were not officially discussed. For instance, when Queen Elizabeth arrived in Stoney Creek, Ontario

, five chiefs in full feathered headdress

and a cortege of 20 braves and their consorts came to present to her a letter outlining their grievances, but were prevented by officials from meeting with the sovereign.

and Cree chief Ralph Steinhauer

, held audience with the monarch there in 1976.

In the prelude to the patriation

of the Canadian constitution

in 1982, First Nations leaders campaigned for and against the proposed move, many asserting that the federal ministers of the Crown

at that time had no right to advise the Queen that she sever, without consent from the First Nations, the treaty rights she and her ancestors had long granted to aboriginal Canadians. Worrying to them was the fact that their relationship with the monarch had, over the preceding century, come to be interpreted by Indian Affairs officials as one of subordination to the government a misreading on the part of non-aboriginals of the terms Great White Mother and her Indian Children. Indeed, First Nations representatives were locked out of constitutional conferences in the late 1970s, leading the National Indian Brotherhood

(NIB) to make plans to petition the Queen directly. The Liberal

Cabinet at the time, not wishing to be embarrassed by having the monarch intervene, extended to the NIB an invitation to talks at the ministerial level, though not the first ministers' meetings. But the invite came just before the election in May 1979

, which put the Progressive Conservative Party

into Cabinet and the new ministers of the Crown decided to advise the Queen not to meet with the NIB delegation, while telling the NIB that the Queen had no power. The ministers of the Crown eventually reversed their position and offered a similar invitation to constitutional talks, but the NIB party, consisting of over 200 people, had already departed for London.

No meeting with the Queen took place, but the indigenous Canadians' position was confirmed by Master of the Rolls

the Lord Denning

, who ruled that the relationship was indeed one between sovereign and First Nations directly, clarifying further that, since the Statute of Westminster was passed in 1931, the Canadian Crown had come to be distinct from the British Crown

, though the two were still held by the same monarch, leaving the treaties sound. Upon their return to Canada, the NIB was granted access to first ministers' meetings and the ability to address the premiers.

Some 15 years later, Governor General-in-Council

, per the Inquiry Act and on the advice of Prime Minister Brian Mulroney

, established the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples

to address a number of concerns surrounding the relationship between aboriginal and non-aboriginal people in Canada. After 178 days of public hearings, visits by 96 communities, and numerous reviews and reports, the central conclusion reached was that "the main policy direction, pursued for more than 150 years, first by colonial then by Canadian governments, has been wrong," focusing on the previous attempts at cultural assimilation

. It was recommended that the nation-to-nation relationship of mutual respect be re-established between the Crown and First Nations, specifically calling for the monarch to "announce the establishment of a new era of respect for the treaties" and renew the treaty process through the issuance of a new royal proclamation as supplement to the Royal Proclamation of 1763. It was argued by Tony Hall, a professor of Native American studies at the University of Lethbridge

, that the friendly relations between monarch and indigenous Canadians must continue as a means to exercise Canadian sovereignty

.

In 1994, while the Queen and her then Prime Minister

, Jean Chrétien

, were attending an aboriginal cultural festival in Yellowknife, the Dene

community of the Northwest Territories

presented a list of grievances over stalled land claim negotiations. Similarly, the Queen and Chrétien visited in 1997 the community of Sheshatshiu

in Newfoundland and Labrador

, where the Innu

people of Quebec and Labrador

presented a letter of grievance over stagnant land claim talks. On both occasions, instead of giving the documents to the Prime Minister, as he was not party to the treaty agreements, they were handed by the Chiefs to the Queen, who, after speaking with the them, then passed the list and letter to Chrétien for he and the other ministers of the Crown

to address and advise

the Queen or her viceroy

on how to proceed.

Still, as recently as 2005, First Nations were complaining that, during the visit of Queen Elizabeth II to Alberta and Saskatchewan that year, they were relegated to a merely ceremonial role, being denied by federal and provincial ministers any access to the Queen in private audience. First Nations leaders have also raised concerns about what they see as a crumbling relationship between their people and the Crown, fuelled by the failure of the federal and provincial cabinets to resolve land claim disputes, as well as a perceived intervention of the Crown into aboriginal affairs. Formal relations have also not yet been founded between the monarchy and a number of First Nations around Canada; such as those in British Columbia

who are still engaged in the process of treaty making

.

Portraits of the Four Mohawk Kings that had been commissioned while the aboriginal leaders were in London had then hung at Kensington Palace

for nearly 270 years, until Queen Elizabeth II in 1977 donated them to the Canadian Collection at the National Archives of Canada

, unveiling them personally in Ottawa. That same year, the Queen's son, Prince Charles, Prince of Wales

, visited Alberta to attend celebrations marking the 100th anniversary of the signing of Treaty 7

, when he was made a Kainai

chieftain, and, as a bicentennial gift in 1984, Elizabeth II gave to the Christ Church Royal Chapel

of the Mohawks a silver chalice to replace that which was lost from the 1712 Queen Anne set during the American Revolution

. In 2003, Elizabeth's other son, Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex

, opened the Regina, Saskatchewan

, campus of the First Nations University of Canada

, where the Queen made her first stop during her 2005 tour of Saskatchewan and Alberta and presented the university with a commemorative granite plaque.

A similar scene took place at British Columbia's Government House

, when in 2009 Shawn Atleo

, the National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations

, presented Prince Charles, Prince of Wales

, with a letter of complaint about the Crown's fulfillment of its treaty duties, and requested a meeting with the Queen.

Prince Charles in 2009 added another dimension to the relationship between the Crown and First Nations when, in a speech in Vancouver

, he drew a connection between his own personal interests and concerns in environmentalism

and the cultural practices and traditions of Canada's First Nations.

On 4 July 2010, Queen Elizabeth II presented to Her Majesty's Royal Chapel of the Mohawks

and Christ Church Royal Chapel

sets of handbell

s, to symbolise the councils and treaties between the Iroquois Confederacy and the Crown.

As the representatives in Canada and the provinces of the reigning monarch, governors, both general and lieutenant, have been closely associated with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. This dates back to the colonial era, when the sovereign did not travel from Europe to Canada, and so dealt with aboriginal societies through his viceroy

As the representatives in Canada and the provinces of the reigning monarch, governors, both general and lieutenant, have been closely associated with First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. This dates back to the colonial era, when the sovereign did not travel from Europe to Canada, and so dealt with aboriginal societies through his viceroy

. After the American Revolution, a tradition was initiated in eastern Canada of appealing to the viceregal representatives for redress of grievances, and later, after returning from a cross-country tour in 1901, during which he met with First Nations in the Yukon

, Governor General

The Earl of Minto

urged his ministers to redress the wrongs he had witnessed in the north and to preserve native heritage and folklore.

Federal and provincial viceroys also met with First Nations leaders for more ceremonial occasions, such as when in 1867 Canada's first Governor General, The Viscount Monk, met with a native chief, in full feathers, amongst some of the first guests at Rideau Hall

. The Marguess of Lansdowne

smoked a calumet

with aboriginal people in the Prairies

, The Marquess of Lorne

was there named Great Brother-in-Law, and The Lord Tweedsmuir

was honoured by the Kainai Nation

through being made a chief of the Blood Indians and met with Grey Owl

in Saskatchewan. The Earl Alexander of Tunis

was presented with a totem pole

by Kwakiutl

carver Mungo Martin

, which Alexander erected on the grounds of Rideau Hall

, where it stands today with the inukshuk

by artist Kananginak Pootoogook that was commissioned in 1997 by Governor General Roméo LeBlanc

to commemorate the second National Aboriginal Day

. Governor General The Viscount Byng of Vimy

undertook a far-reaching tour of the north in 1925, during which the he met with First Nations and heard their grievances at Fort Providence

and Fort Simpson

. Later, Governor General Edward Schreyer

was in 1984 made an honorary member of the Kainai Chieftainship, as was one his viceregal successors, Adrienne Clarkson

, who was made such on 23 July 2005, along with being adopted into the Blood Tribe with the name Grandmother of Many Nations. Clarkson was an avid supporter of Canada's north and Inuit culture, employing students from Nunavut Arctic College

to assist in designing the Clarkson Cup

and creating the Governor General's Northern Medal

.

Five persons from First Nations have been appointed as the monarch's representative, all in the provincial spheres. Ralph Steinhauer

Five persons from First Nations have been appointed as the monarch's representative, all in the provincial spheres. Ralph Steinhauer

was the first, having been made Lieutenant Governor of Alberta

on 2 July 1974; Steinhauer was from the Cree

nation. W. Yvon Dumont

was of Métis

heritage and served as Lieutenant Governor of Manitoba

between 1993 and 1999. The first Lieutenant Governor of Ontario

of aboriginal heritage was James Bartleman, who was appointed to the position on 7 March 2002. A member of the Mnjikaning First Nation, Bartlemen listed the encouragement of indigenous young people as one of his key priorities, and, during his time in the Queen's service, launched several initiatives to promote literacy and social bridge building, travelling to remote native communities in northern Ontario, pairing native and non-native schools, and creating the Lieutenant Governor's Book Program, which collected 1.4 million books that were flown into the province's north to stock shelves of First Nations community libraries. On 1 October 2007, Steven Point

, from the Skowkale First Nation

, was installed as Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia

, and Graydon Nicholas

, born on the Tobique Indian Reserve

, was made Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick

on 30 September 2009.

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

stretches back to the first interactions

Timeline of colonization of North America

This is a chronology of the colonization of North America, with founding dates of European settlements. See also European colonization of the Americas.-Before Columbus:* 6th Century: Brendan The Navigator possibly reaches North America.* 874: Norse reach Iceland...

between North American indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples of the Americas

The indigenous peoples of the Americas are the pre-Columbian inhabitants of North and South America, their descendants and other ethnic groups who are identified with those peoples. Indigenous peoples are known in Canada as Aboriginal peoples, and in the United States as Native Americans...

and Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

an colonialists and, over centuries of interface, treaties

Treaty

A treaty is an express agreement under international law entered into by actors in international law, namely sovereign states and international organizations. A treaty may also be known as an agreement, protocol, covenant, convention or exchange of letters, among other terms...

were established concerning the monarch and aboriginal tribes. Canada's First Nations

First Nations

First Nations is a term that collectively refers to various Aboriginal peoples in Canada who are neither Inuit nor Métis. There are currently over 630 recognised First Nations governments or bands spread across Canada, roughly half of which are in the provinces of Ontario and British Columbia. The...

, Inuit

Inuit

The Inuit are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic regions of Canada , Denmark , Russia and the United States . Inuit means “the people” in the Inuktitut language...

, and Métis

Métis people (Canada)

The Métis are one of the Aboriginal peoples in Canada who trace their descent to mixed First Nations parentage. The term was historically a catch-all describing the offspring of any such union, but within generations the culture syncretised into what is today a distinct aboriginal group, with...

peoples now have a unique relationship with the reigning monarch and, like the Māori and the Treaty of Waitangi

Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi is a treaty first signed on 6 February 1840 by representatives of the British Crown and various Māori chiefs from the North Island of New Zealand....

in New Zealand

New Zealand

New Zealand is an island country in the south-western Pacific Ocean comprising two main landmasses and numerous smaller islands. The country is situated some east of Australia across the Tasman Sea, and roughly south of the Pacific island nations of New Caledonia, Fiji, and Tonga...

, generally view the affiliation as being not between them and the ever-changing Cabinet

Cabinet of Canada

The Cabinet of Canada is a body of ministers of the Crown that, along with the Canadian monarch, and within the tenets of the Westminster system, forms the government of Canada...

, but instead with the continuous Crown of Canada, as embodied in the reigning sovereign. These agreements with the Crown are administered by Canadian Aboriginal law

Canadian Aboriginal law

Canadian Aboriginal law is the body of Canadian law that concerns a variety of issues related to aboriginal peoples in Canada. Aboriginal law provides certain rights to land and traditional practices...

and overseen by the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development.

Relations

The association between Canada's AboriginalsAboriginal peoples in Canada

Aboriginal peoples in Canada comprise the First Nations, Inuit and Métis. The descriptors "Indian" and "Eskimo" have fallen into disuse in Canada and are commonly considered pejorative....

and the Canadian Crown is both statutory and traditional, the treaties being seen by the first peoples both as legal contracts and as perpetual and personal promises by successive reigning kings and queens to protect Aboriginal welfare, define their rights, and reconcile their sovereignty with that of the monarch in Canada. The agreements are formed with the Crown because the monarchy is thought to have inherent stability and continuity, as opposed to the transitory nature of populist whims that rule the political government, meaning the link between monarch and Aboriginals will theoretically last for "as long as the sun shines, grass grows and rivers flow."

The relationship has thus been described as mutual "cooperation will be a cornerstone for partnership between Canada and First Nations, wherein Canada is the short-form reference to Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada" and "special," having a strong sense of "kinship" and possessing familial aspects. Constitutional scholars have observed that First Nations are "strongly supportive of the monarchy

Monarchism in Canada

Canadian monarchism is the appreciation amongst Canadians for, and thus also advocacy for the retention of, their distinct system of constitutional monarchy, countering anti-monarchical reform as being generally revisionist, idealistic, and ultimately impracticable...

," even if not necessarily regarding the monarch as supreme. The nature of the legal interaction between Canadian sovereign and First Nations has similarly not always been supported.

Definition

While treaties were signed between European monarchs and First Nations in North America as far back as 1676, the only ones that survived the American RevolutionAmerican Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

are those in Canada, which date to the beginning of the 18th century. Today, the main guide for relations between the monarchy and Canadian First Nations is King George III's

George III of the United Kingdom

George III was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of these two countries on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland until his death...

Royal Proclamation of 1763

Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued October 7, 1763, by King George III following Great Britain's acquisition of French territory in North America after the end of the French and Indian War/Seven Years' War...

; while not a treaty, it is regarded by First Nations as their Magna Carta

Magna Carta

Magna Carta is an English charter, originally issued in the year 1215 and reissued later in the 13th century in modified versions, which included the most direct challenges to the monarch's authority to date. The charter first passed into law in 1225...

or "Indian Bill of Rights", binding on not only the British Crown

Monarchy of the United Kingdom

The monarchy of the United Kingdom is the constitutional monarchy of the United Kingdom and its overseas territories. The present monarch, Queen Elizabeth II, has reigned since 6 February 1952. She and her immediate family undertake various official, ceremonial and representational duties...

, but the Canadian one as well, as the document remains a part of the Canadian constitution

Constitution of Canada

The Constitution of Canada is the supreme law in Canada; the country's constitution is an amalgamation of codified acts and uncodified traditions and conventions. It outlines Canada's system of government, as well as the civil rights of all Canadian citizens and those in Canada...

. The proclamation set parts of the King's North America

North America

North America is a continent wholly within the Northern Hemisphere and almost wholly within the Western Hemisphere. It is also considered a northern subcontinent of the Americas...

n realm aside for colonists and reserved others for the First Nations

Indian reserve

In Canada, an Indian reserve is specified by the Indian Act as a "tract of land, the legal title to which is vested in Her Majesty, that has been set apart by Her Majesty for the use and benefit of a band." The Act also specifies that land reserved for the use and benefit of a band which is not...

, thereby affirming native title to their lands and making clear that, though under the sovereignty

Sovereignty

Sovereignty is the quality of having supreme, independent authority over a geographic area, such as a territory. It can be found in a power to rule and make law that rests on a political fact for which no purely legal explanation can be provided...

of the Crown, the aboriginal bands were autonomous political units in a "nation-to-nation" association with non-native governments, with the monarch as the intermediary. This created not only a "constitutional and moral basis of alliance" between indigenous Canadians and the Canadian state as personified in the monarch, but also a fiduciary affiliation in which the Crown is constitutionally charged with providing certain guarantees to the First Nations, as affirmed in Sparrow v. The Queen

R. v. Sparrow

R. v. Sparrow, [1990] 1 S.C.R. 1075 was an important decision of the Supreme Court of Canada concerning the application of Aboriginal rights under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982...

, meaning that the "honour of the Crown" is at stake in dealings between it and First Nations leaders.

Given the "divided" nature of the Crown

Monarchy in the Canadian provinces

The monarchy of Canada forms the core of each Canadian provincial jurisdiction's Westminster-style parliamentary democracy, being the foundation of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government in each province...

, the sovereign may be party to relations with aboriginal Canadians distinctly within a provincial jurisdiction. This has at times lead to a lack of clarity regarding which of the monarch's jurisdictions should administer his or her duties towards indigenous peoples.

Expressions

From time to time, the link between crown and Aboriginal peoples will be symbolically expressed, through pow-wowPow-wow

A pow-wow is a gathering of North America's Native people. The word derives from the Narragansett word powwaw, meaning "spiritual leader". A modern pow-wow is a specific type of event where both Native American and non-Native American people meet to dance, sing, socialize, and honor American...

s or other types of ceremony held to mark the anniversary of a particular treaty sometimes with the participation of the monarch, another member of the Canadian Royal Family, or one of the sovereign's representatives or simply an occasion mounted to coincide with the presence of a member of the Royal Family on a royal tour, Aboriginals having always been a part of such tours of Canada. Gifts have been frequently exchanged such as when the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh people's Capilano Indian Community Club of North Vancouver in 1953 gave the Duke of Edinburgh a walking stick

Walking stick

A walking stick is a device used by many people to facilitate balancing while walking.Walking sticks come in many shapes and sizes, and can be sought by collectors. Some kinds of walking stick may be used by people with disabilities as a crutch...

in the form of a totem pole

Totem pole

Totem poles are monumental sculptures carved from large trees, mostly Western Red Cedar, by cultures of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast of North America...

and Aboriginal titles have been bestowed upon royal and viceroyal figures since the earliest days of contact with the Crown: The Ojibwa

Ojibwa

The Ojibwe or Chippewa are among the largest groups of Native Americans–First Nations north of Mexico. They are divided between Canada and the United States. In Canada, they are the third-largest population among First Nations, surpassed only by Cree and Inuit...

referred to George III as the Great Father and Queen Victoria was later dubbed as the Great White Mother. Queen Elizabeth II was named Mother of all People by the Salish nation

Bitterroot Salish (tribe)

The Bitterroot Salish are one of three tribes of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation in Montana. The Flathead Reservation is home to the Kootenai and Pend d'Oreilles tribes also.-Language:...

in 1959 and her son, Prince Charles, was in 1976 given by the Inuit the title of Attaniout Ikeneego, meaning Son of the Big Boss. Charles was further honoured in 1986, when Cree

Cree

The Cree are one of the largest groups of First Nations / Native Americans in North America, with 200,000 members living in Canada. In Canada, the major proportion of Cree live north and west of Lake Superior, in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and the Northwest Territories, although...

and Ojibwa

Ojibwa

The Ojibwe or Chippewa are among the largest groups of Native Americans–First Nations north of Mexico. They are divided between Canada and the United States. In Canada, they are the third-largest population among First Nations, surpassed only by Cree and Inuit...

students in Winnipeg

Winnipeg

Winnipeg is the capital and largest city of Manitoba, Canada, and is the primary municipality of the Winnipeg Capital Region, with more than half of Manitoba's population. It is located near the longitudinal centre of North America, at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine Rivers .The name...

named Charles Leading Star, and again in 2001, during the Prince's first visit to Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan is a prairie province in Canada, which has an area of . Saskatchewan is bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, and on the south by the U.S. states of Montana and North Dakota....

, when he was named Pisimwa Kamiwohkitahpamikohk, or The Sun Looks at Him in a Good Way, by an elder in a ceremony at Wanuskewin Heritage Park

Wanuskewin Heritage Park

Wanuskewin Heritage Park is a non-profit internationally-recognized award-winning interpretive centre that reflects First Nations culture, history, and values...

.

French and British crowns

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

and English

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

monarchs made contact with North American aboriginals in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. These interactions were generally peaceful the agents of each sovereign seeking the Indians' alliance in wresting territories away from the other monarch and the partnerships were typically secured through treaties, the first signed in 1676. However, the English also used friendly gestures as a vehicle for establishing Crown dealings with aboriginal inhabitants, while simultaneously expanding their domain: as fur trade

Fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of world market for in the early modern period furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the most valued...

rs and outposts of the Hudson's Bay Company

Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company , abbreviated HBC, or "The Bay" is the oldest commercial corporation in North America and one of the oldest in the world. A fur trading business for much of its existence, today Hudson's Bay Company owns and operates retail stores throughout Canada...

(HBC), a crown corporation founded in 1670, spread westward across the continent, they introduced the concept of a just, paternal monarch to "guide and animate their exertions," to inspire loyalty, and promote peaceful relations. They also brought with them images of the English monarch, such as the medal that bore the effigy

Effigy

An effigy is a representation of a person, especially in the form of sculpture or some other three-dimensional form.The term is usually associated with full-length figures of a deceased person depicted in stone or wood on church monuments. These most often lie supine with hands together in prayer,...

of King Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

(founder of the HBC) and which was presented to native chiefs as a mark of distinction; these medallions were passed down through the generations of the chiefs' descendants and those who wore them received particular honour and recognition at HBC posts.

The Great Peace of Montreal

Great Peace of Montreal

The Great Peace of Montreal was a peace treaty between New France and 40 First Nations of North America. It was signed on August 4, 1701, by Louis-Hector de Callière, governor of New France, and 1300 representatives of 40 aboriginal nations of the North East of North America...

was in 1701 signed by the Governor of New France

Governor of New France

The Governor of New France was the viceroy of the King of France in North America. A French noble, he was appointed to govern the colonies of New France, which included Canada, Acadia and Louisiana. The residence of the Governor was at the Château St-Louis in the capital of Quebec City...

, representing King Louis XIV

Louis XIV of France

Louis XIV , known as Louis the Great or the Sun King , was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and Navarre. His reign, from 1643 to his death in 1715, began at the age of four and lasted seventy-two years, three months, and eighteen days...

, and the chiefs of 39 First Nations. Then, in 1710, aboriginal leaders were visiting personally with the British monarch; in that year, Queen Anne

Anne of Great Britain

Anne ascended the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland on 8 March 1702. On 1 May 1707, under the Act of Union, two of her realms, England and Scotland, were united as a single sovereign state, the Kingdom of Great Britain.Anne's Catholic father, James II and VII, was deposed during the...

held audience at St. James' Palace

St. James's Palace

St. James's Palace is one of London's oldest palaces. It is situated in Pall Mall, just north of St. James's Park. Although no sovereign has resided there for almost two centuries, it has remained the official residence of the Sovereign and the most senior royal palace in the UK...

with three Mohawk Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow of the Bear Clan (called Peter Brant, King of Maguas), Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row of the Wolf Clan (called King John of Canojaharie), and Tee Yee Ho Ga Row, or "Double Life", of the Wolf Clan (called King Hendrick

King Hendrick

Hendrick Theyanoguin , whose name had several spelling variations, was an important Mohawk leader and member of the Bear Clan who was located at Canajoharie or the Upper Mohawk Castle in colonial New York.. He was a speaker for the Mohawk Council...

Peters) and one Mahicanin Chief Etow Oh Koam of the Turtle Clan (called Emperor of the Six Nations). The four, dubbed the Four Mohawk Kings, were received in London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

as diplomats, being transported through the streets in royal carriages and visiting the Tower of London

Tower of London

Her Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress, more commonly known as the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London, England. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, separated from the eastern edge of the City of London by the open space...

and St. Paul's Cathedral. But, their business was to request military aid for defence against the French, as well as missionaries for spiritual guidance. The latter request was passed by Anne to the Archbishop of Canterbury

Archbishop of Canterbury

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group...

, Thomas Tenison

Thomas Tenison

Thomas Tenison was an English church leader, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1694 until his death. During his primacy, he crowned two British monarchs.-Life:...

, and a chapel was eventually built in 1711 at Fort Hunter, near present day Johnstown, New York

Johnstown (town), New York

Johnstown is a town located in Fulton County, New York, United States. As of the 2000 U.S. Census, the town had a population of 7,166. The name of the town is from landowner William Johnson....

, along with the gift of a reed organ and a set of silver chalice

Chalice (cup)

A chalice is a goblet or footed cup intended to hold a drink. In general religious terms, it is intended for drinking during a ceremony.-Christian:...

s in 1712.

Both British and French monarchs viewed their lands in North America as being held by them in totality, including those occupied by First Nations. Typically, the treaties established delineations between territory reserved for colonial settlement and that distinctly for aboriginal use. The French kings, though they did not admit claims by aboriginals to lands in New France, granted the natives reserves for their exclusive use; for instance, from 1716 onwards, land north and west of the manorials

Manorialism

Manorialism, an essential element of feudal society, was the organizing principle of rural economy that originated in the villa system of the Late Roman Empire, was widely practiced in medieval western and parts of central Europe, and was slowly replaced by the advent of a money-based market...

on the Saint Lawrence River

Saint Lawrence River

The Saint Lawrence is a large river flowing approximately from southwest to northeast in the middle latitudes of North America, connecting the Great Lakes with the Atlantic Ocean. It is the primary drainage conveyor of the Great Lakes Basin...

were designated as the pays d'enhaut (upper country), or "Indian country", and were forbidden to settlement and clearing of land without the expressed authorisation of the King. The same was done by the kings of Great Britain; for example, the Treaty of 1725, establishing a relationship between King George III and the "Maeganumbe... tribes Inhabiting His Majesty's Territories," acknowledged the King's title to the provinces of Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is one of Canada's three Maritime provinces and is the most populous province in Atlantic Canada. The name of the province is Latin for "New Scotland," but "Nova Scotia" is the recognized, English-language name of the province. The provincial capital is Halifax. Nova Scotia is the...

and Acadia

Acadia

Acadia was the name given to lands in a portion of the French colonial empire of New France, in northeastern North America that included parts of eastern Quebec, the Maritime provinces, and modern-day Maine. At the end of the 16th century, France claimed territory stretching as far south as...

in exchange for the guarantee that the indigenous people "not be molested in their persons... by His Majesty's subjects."

The sovereigns also sought alliances with the First Nations; the Iroquois

Iroquois

The Iroquois , also known as the Haudenosaunee or the "People of the Longhouse", are an association of several tribes of indigenous people of North America...

siding with Georges II and III and the Algonquin with Louis XIV and XV. These arrangements left questions about the treatment of aboriginals in the French territories once the latter were ceded in 1760 to George III. Article 40 of the Capitulation of Montreal

Montreal

Montreal is a city in Canada. It is the largest city in the province of Quebec, the second-largest city in Canada and the seventh largest in North America...

, signed on 8 September 1760, inferred that First Nations peoples who had been subjects of King Louis XV

Louis XV of France

Louis XV was a Bourbon monarch who ruled as King of France and of Navarre from 1 September 1715 until his death. He succeeded his great-grandfather at the age of five, his first cousin Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, served as Regent of the kingdom until Louis's majority in 1723...

would then become the same of King George: "The Savages or Indian allies of his most Christian Majesty, shall be maintained in the Lands they inhabit; if they chose to remain there; they shall not be molested on any pretence whatsoever, for having carried arms, and served his most Christian Majesty; they shall have, as well as the French, liberty of religion, and shall keep their missionaries..." Yet, two days before, the Algonquin, along with the Hurons of Lorette and eight other tribes, had already ratified a treaty at Fort Lévis

Fort Lévis

Fort Lévis, a fortification on the St. Lawrence River, was built in 1759 by the French. They had decided that Fort de La Présentation was insufficient to defend the St. Lawrence against the British. Named for François Gaston de Lévis, Duc de Lévis, the fort was constructed on Isle Royale, three...

, making them allied with, and subjects of, the British king, who instructed General the Lord Amherst

Jeffrey Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst

Field Marshal Jeffery Amherst, 1st Baron Amherst KCB served as an officer in the British Army and as Commander-in-Chief of the Forces.Amherst is best known as one of the victors of the French and Indian War, when he conquered Louisbourg, Quebec City and...

to treat the First Nations "upon the same principals of humanity and proper indulgence" as the French, and to "cultivate the best possible harmony and Friendship with the Chiefs of the Indian Tribes." The retention of civil code

Civil law (legal system)

Civil law is a legal system inspired by Roman law and whose primary feature is that laws are codified into collections, as compared to common law systems that gives great precedential weight to common law on the principle that it is unfair to treat similar facts differently on different...

in Quebec, though, caused the relations between the Crown and First Nations in that jurisdiction to be viewed as dissimilar to those that existed in the other Canadian colonies.

In 1763, George III issued a Royal Proclamation

Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued October 7, 1763, by King George III following Great Britain's acquisition of French territory in North America after the end of the French and Indian War/Seven Years' War...

that acknowledged the First Nations as autonomous political units and affirmed their title to their lands; it became the main document governing the parameters of the relationship between the sovereign and his aboriginal subjects in North America. The King thereafter ordered Sir William Johnson to make the proclamation known to the aboriginal nations under the King's sovereignty and, by 1766, its provisions were already put into practical use: In that year, the Imperial Privy Council endorsed a grant of 20000 acres (80.9 km²) to Joseph Marie Philibot at a location of his choosing, but Philibot's request for land on the Restigouche River

Restigouche River

The Restigouche River is a river that flows across the northwestern part of the province of New Brunswick and the southeastern part of Quebec....

was denied by the Governor of Quebec on the grounds that "the lands so prayed to be assigned are, or are claimed to be, the property of the Indians and as such by His Majesty's express command as set forth in his proclamation in 1763, not within their power to grant." In the prelude to the American Revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

, native leader Joseph Brant

Joseph Brant

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant was a Mohawk military and political leader, based in present-day New York, who was closely associated with Great Britain during and after the American Revolution. He was perhaps the most well-known American Indian of his generation...

took the King up on this offer of protection and voyaged to London between 1775 and 1776 to meet with George III in person and discuss the aggressive expansionist policies of the American colonists.

After the American Revolution

Treaty of Paris (1783)

The Treaty of Paris, signed on September 3, 1783, ended the American Revolutionary War between Great Britain on the one hand and the United States of America and its allies on the other. The other combatant nations, France, Spain and the Dutch Republic had separate agreements; for details of...

, signed in 1783 between King George and the American Congress of the Confederation

Congress of the Confederation

The Congress of the Confederation or the United States in Congress Assembled was the governing body of the United States of America that existed from March 1, 1781, to March 4, 1789. It comprised delegates appointed by the legislatures of the states. It was the immediate successor to the Second...

, British North America was divided into the sovereign United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

(US) and the still British Canadas

The Canadas

The Canadas is the collective name for Upper Canada and Lower Canada, two British colonies in Canada. They were both created by the Constitutional Act of 1791 and abolished in 1841 with the union of Upper and Lower Canada....

, creating a new international border through some of those lands that had been set apart by the Crown for First Nations and completely immersing others within the new republic. As a result, some aboriginal tribes felt betrayed by the King and their service to the monarch was detailed in oratories that called on the Crown to keep its promises, especially after nations that had allied themselves with the British sovereign were driven from their lands by Americans. New treaties were drafted and those indigenous nations that had lost their territories in the United States, or simply wished to not live under the US government, were granted new land in Canada by the King.

The Mohawk Nation

Mohawk nation

Mohawk are the most easterly tribe of the Iroquois confederation. They call themselves Kanien'gehaga, people of the place of the flint...

was one such group, which abandoned its Mohawk Valley

Mohawk Valley

The Mohawk Valley region of the U.S. state of New York is the area surrounding the Mohawk River, sandwiched between the Adirondack Mountains and Catskill Mountains....

territory, in present day New York State, after Americans destroyed the natives' settlement, including the chapel donated by Queen Anne following the visit to London of the Four Mohawk Kings. As compensation, George III promised land in Canada to the Six Nations and, in 1784, some Mohawks settled in what is now the Bay of Quinte

Bay of Quinte

The Bay of Quinte is a long, narrow bay shaped like the letter "Z" on the northern shore of Lake Ontario in the province of Ontario, Canada. It is just west of the head of the Saint Lawrence River that drains the Great Lakes into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence...

and the Grand River Valley

Six Nations 40, Ontario

Six Nations is the largest First Nation in Canada with a total of 23,902 band members. 11,865 are reported living in the territory. It is the only territory in North America that has the six Iroquois nations living together. These nations are the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and...

, where North America's only two Chapels Royal

Chapel Royal

A Chapel Royal is a body of priests and singers who serve the spiritual needs of their sovereign wherever they are called upon to do so.-Austria:...

Christ Church Royal Chapel of the Mohawks

Christ Church Royal Chapel

Christ Church, Her Majesty's Chapel Royal of the Mohawk is located near Deseronto, Ontario, and is one of only six Royal chapels outside of the United Kingdom, and one of two in Canada...

and Her Majesty's Chapel of the Mohawks

Mohawk Chapel

Her Majesty's Royal Chapel of the Mohawks, the oldest building in Ontario, is one of six Chapels Royal outside of the United Kingdom, and one of two in Canada, the other being Christ Church Royal Chapel near Deseronto, Ontario. It was elevated to a Chapel Royal by Edward VII in 1904...

were built to symbolise the connection between the Mohawk people and the Crown. Thereafter, the treaties with aboriginals across southern Ontario were dubbed the Covenant Chain

Covenant Chain

The Covenant Chain was a series of alliances and treaties involving the Iroquois Confederacy , the British colonies of North America, and a number of other Indian tribes...

and ensured the preservation of First Nations' rights not provided elsewhere in the Americas.

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was a military conflict fought between the forces of the United States of America and those of the British Empire. The Americans declared war in 1812 for several reasons, including trade restrictions because of Britain's ongoing war with France, impressment of American merchant...

.

In 1860, during one of the first true royal tours of Canada

Royal tours of Canada

Canadian royal tours have been taking place since 1786, and continue into the 21st century, either as an official tour, a working tour, a vacation, or a period of military service by a member of the Canadian Royal Family...

, First Nations put on displays, expressed their loyalty to Queen Victoria

Victoria of the United Kingdom

Victoria was the monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death. From 1 May 1876, she used the additional title of Empress of India....

and presented concerns about misconduct on the part of the Indian Department to the Queen's son, Prince Albert Edward, Prince of Wales

Edward VII of the United Kingdom

Edward VII was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions and Emperor of India from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910...

, when he was in Upper Canada

Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada was a political division in British Canada established in 1791 by the British Empire to govern the central third of the lands in British North America and to accommodate Loyalist refugees from the United States of America after the American Revolution...

. In that same year, Nahnebahwequay of the Ojibwa

Ojibwa

The Ojibwe or Chippewa are among the largest groups of Native Americans–First Nations north of Mexico. They are divided between Canada and the United States. In Canada, they are the third-largest population among First Nations, surpassed only by Cree and Inuit...

secured an audience with the Queen. When Governor General the Marquess of Lorne

John Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll

John George Edward Henry Douglas Sutherland Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll KG, KT, GCMG, GCVO, VD, PC , usually better known by the courtesy title Marquess of Lorne, by which he was known between 1847 and 1900, was a British nobleman and was the fourth Governor General of Canada from 1878 to 1883...

and his wife, Princess Louise

Princess Louise, Duchess of Argyll

The Princess Louise was a member of the British Royal Family, the sixth child and fourth daughter of Queen Victoria and her husband, Albert, Prince Consort.Louise's early life was spent moving between the various royal residences in the...

, a daughter of Queen Victoria, visited British Columbia

British Columbia

British Columbia is the westernmost of Canada's provinces and is known for its natural beauty, as reflected in its Latin motto, Splendor sine occasu . Its name was chosen by Queen Victoria in 1858...

in 1882, they were greeted upon arrival in New Westminster by a floatilla of local Aboriginals in canoes who sang songs of welcome before the royal couple landed and proceeded through a ceremonial arch built by Aboriginals, which was hung with a banner reading "Clahowya Queenastenass", Chinookian

Chinookan languages

Chinookan is a small family of languages spoken in Oregon and Washington along the Columbia River by Chinook peoples.-Family division:Chinookan languages consists of three languages with multiple varieties. There is some dispute over classification, and there are two ISO 639-3 codes assigned: and...

for "Welcome Queen." The following day, the Duke and Duchess gave their presence to an event attended by thousands of First Nations people and at least 40 chiefs. One presented the Princess with baskets, a bracelet, and a ring of Aboriginal make and Louise said in response that, when she returned to the United Kingdom, she would show these items to the Queen.

Once the Dominion Crown purchased what remained of Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land, or Prince Rupert's Land, was a territory in British North America, consisting of the Hudson Bay drainage basin that was nominally owned by the Hudson's Bay Company for 200 years from 1670 to 1870, although numerous aboriginal groups lived in the same territory and disputed the...

from the Hudson's Bay Company and colonial settlement expanded westwards, more treaties were signed between 1871 and 1921, wherein the Crown brokered land exchanges that granted the aboriginal societies reserves and other compensation, such as livestock, ammunition, education, health care, and certain rights to hunt and fish. This situation under the Crown was regarded by the First Nations as better than that which had befallen their brethren in the United States. The treaties did not ensure peace: as evidenced by the North-West Rebellion

North-West Rebellion

The North-West Rebellion of 1885 was a brief and unsuccessful uprising by the Métis people of the District of Saskatchewan under Louis Riel against the Dominion of Canada...

of 1885, sparked by Métis people's

Métis people (Canada)

The Métis are one of the Aboriginal peoples in Canada who trace their descent to mixed First Nations parentage. The term was historically a catch-all describing the offspring of any such union, but within generations the culture syncretised into what is today a distinct aboriginal group, with...

concerns over their survival and discontent on the part of Cree

Cree

The Cree are one of the largest groups of First Nations / Native Americans in North America, with 200,000 members living in Canada. In Canada, the major proportion of Cree live north and west of Lake Superior, in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and the Northwest Territories, although...

people over perceived unfairness in the treaties signed with Queen Victoria.

Independent Canada

Following Canada's legislative independence from the United Kingdom codified by the Statute of Westminster, 1931 relations both statutory and ceremonial between sovereign and First Nations continued unaffected as the British Crown in Canada morphed into a distinctly Canadian monarchy. Indeed, during the 1939 tour of Canada by King George VIGeorge VI of the United Kingdom

George VI was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death...

and Queen Elizabeth

Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon

Elizabeth Angela Marguerite Bowes-Lyon was the queen consort of King George VI from 1936 until her husband's death in 1952, after which she was known as Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, to avoid confusion with her daughter, Queen Elizabeth II...

an event intended to express the new independence of Canada and its monarchy First Nations journeyed to city centres like Regina, Saskatchewan

Regina, Saskatchewan

Regina is the capital city of the Canadian province of Saskatchewan. The city is the second-largest in the province and a cultural and commercial centre for southern Saskatchewan. It is governed by Regina City Council. Regina is the cathedral city of the Roman Catholic and Romanian Orthodox...

, and Calgary

Calgary

Calgary is a city in the Province of Alberta, Canada. It is located in the south of the province, in an area of foothills and prairie, approximately east of the front ranges of the Canadian Rockies...

, Alberta

Alberta

Alberta is a province of Canada. It had an estimated population of 3.7 million in 2010 making it the most populous of Canada's three prairie provinces...

, to meet with the King and present gifts and other displays of loyalty. In the course of the Second World War

World War II

World War II, or the Second World War , was a global conflict lasting from 1939 to 1945, involving most of the world's nations—including all of the great powers—eventually forming two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis...

that followed soon after George's tour, more than 3,000 aboriginal and Métis Canadians fought for the Canadian Crown and country, some receiving personal recognition from the King, such as Tommy Prince

Tommy Prince

Thomas George "Tommy" Prince, MM was one of Canada's most decorated First Nations soldiers, serving in World War II and the Korean War.-Early life:...

, who was presented with the Military Medal

Military Medal

The Military Medal was a military decoration awarded to personnel of the British Army and other services, and formerly also to personnel of other Commonwealth countries, below commissioned rank, for bravery in battle on land....

and, on behalf of the President of the United States

President of the United States

The President of the United States of America is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president leads the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United States Armed Forces....

, the Silver Star

Silver Star

The Silver Star is the third-highest combat military decoration that can be awarded to a member of any branch of the United States armed forces for valor in the face of the enemy....

by the King at Buckingham Palace.

Squamish Nation Chief Joe Mathias was amongst the Canadian dignitaries who were invited to attend the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in London in 1953.

When George's daughter, Queen Elizabeth II, toured Canada twenty years later, similar interactions took place: In Labrador

Labrador

Labrador is the distinct, northerly region of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It comprises the mainland portion of the province, separated from the island of Newfoundland by the Strait of Belle Isle...

, Elizabeth was greeted by the Chief of the Montagnais and given a pair of beaded moose-hide jackets; at Gaspé, Quebec

Gaspé, Quebec

Gaspé is a city at the tip of the Gaspé Peninsula in the Gaspésie–Îles-de-la-Madeleine region of eastern Quebec, Canada. As of the 2006 census, the city had a total population of 14,819....

, the Queen and her husband were presented with deerskin coats by two local aboriginal people; and in Ottawa, a man from the Kahnawake Mohawk Territory passed to officials a 200 year old wampum

Wampum

Wampum are traditional, sacred shell beads of the Eastern Woodlands tribes of the indigenous people of North America. Wampum include the white shell beads fashioned from the North Atlantic channeled whelk shell; and the white and purple beads made from the quahog, or Western North Atlantic...

as a gift for Elizabeth. It was during that journey that the Queen became the first member of the Royal Family to meet with Inuit representatives, doing so in Stratford, Ontario

Stratford, Ontario

Stratford is a city on the Avon River in Perth County in southwestern Ontario, Canada with a population of 32,000.When the area was first settled by Europeans in 1832, the townsite and the river were named after Stratford-upon-Avon, England. It is the seat of Perth County. Stratford was...

, and the royal train stopped in Brantford, Ontario

Brantford, Ontario