Augustan literature

Encyclopedia

- For the period of Latin literature for which the English style is named, see Augustan literature (ancient Rome)Augustan literature (ancient Rome)Augustan literature is the period of Latin literature written during the reign of Augustus , the first Roman emperor. In literary histories of the first part of the 20th century and earlier, Augustan literature was regarded along with that of the Late Republic as constituting the Golden Age of...

.

Augustan literature (sometimes referred to misleadingly as Georgian literature) is a style

Literary genre

A literary genre is a category of literary composition. Genres may be determined by literary technique, tone, content, or even length. Genre should not be confused with age category, by which literature may be classified as either adult, young-adult, or children's. They also must not be confused...

of English literature

English literature

English literature is the literature written in the English language, including literature composed in English by writers not necessarily from England; for example, Robert Burns was Scottish, James Joyce was Irish, Joseph Conrad was Polish, Dylan Thomas was Welsh, Edgar Allan Poe was American, J....

produced during the reigns of Queen Anne

Anne of Great Britain

Anne ascended the thrones of England, Scotland and Ireland on 8 March 1702. On 1 May 1707, under the Act of Union, two of her realms, England and Scotland, were united as a single sovereign state, the Kingdom of Great Britain.Anne's Catholic father, James II and VII, was deposed during the...

, King George I

George I of Great Britain

George I was King of Great Britain and Ireland from 1 August 1714 until his death, and ruler of the Duchy and Electorate of Brunswick-Lüneburg in the Holy Roman Empire from 1698....

, and George II

George II of Great Britain

George II was King of Great Britain and Ireland, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg and Archtreasurer and Prince-elector of the Holy Roman Empire from 11 June 1727 until his death.George was the last British monarch born outside Great Britain. He was born and brought up in Northern Germany...

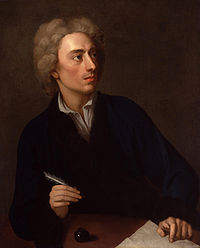

on the 1740s with the deaths of Pope

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope was an 18th-century English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer. He is the third-most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, after Shakespeare and Tennyson...

and Swift

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift was an Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer , poet and cleric who became Dean of St...

(1744 and 1745, respectively). It is a literary epoch

Calendar era

A calendar era is the year numbering system used by a calendar. For example, the Gregorian calendar numbers its years in the Western Christian era . The instant, date, or year from which time is marked is called the epoch of the era...

that featured the rapid development of the novel

Novel

A novel is a book of long narrative in literary prose. The genre has historical roots both in the fields of the medieval and early modern romance and in the tradition of the novella. The latter supplied the present generic term in the late 18th century....

, an explosion in satire

Satire

Satire is primarily a literary genre or form, although in practice it can also be found in the graphic and performing arts. In satire, vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, ideally with the intent of shaming individuals, and society itself, into improvement...

, the mutation of drama

Drama

Drama is the specific mode of fiction represented in performance. The term comes from a Greek word meaning "action" , which is derived from "to do","to act" . The enactment of drama in theatre, performed by actors on a stage before an audience, presupposes collaborative modes of production and a...

from political satire

Political satire

Political satire is a significant part of satire that specializes in gaining entertainment from politics; it has also been used with subversive intent where political speech and dissent are forbidden by a regime, as a method of advancing political arguments where such arguments are expressly...

into melodrama

Melodrama

The term melodrama refers to a dramatic work that exaggerates plot and characters in order to appeal to the emotions. It may also refer to the genre which includes such works, or to language, behavior, or events which resemble them...

, and an evolution toward poetry

Poetry

Poetry is a form of literary art in which language is used for its aesthetic and evocative qualities in addition to, or in lieu of, its apparent meaning...

of personal exploration. In philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

, it was an age increasingly dominated by empiricism

Empiricism

Empiricism is a theory of knowledge that asserts that knowledge comes only or primarily via sensory experience. One of several views of epistemology, the study of human knowledge, along with rationalism, idealism and historicism, empiricism emphasizes the role of experience and evidence,...

, while in the writings of political-economy

Political economy

Political economy originally was the term for studying production, buying, and selling, and their relations with law, custom, and government, as well as with the distribution of national income and wealth, including through the budget process. Political economy originated in moral philosophy...

it marked the evolution of mercantilism

Mercantilism

Mercantilism is the economic doctrine in which government control of foreign trade is of paramount importance for ensuring the prosperity and security of the state. In particular, it demands a positive balance of trade. Mercantilism dominated Western European economic policy and discourse from...

as a formal philosophy, the development of capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

, and the triumph of trade

Trade

Trade is the transfer of ownership of goods and services from one person or entity to another. Trade is sometimes loosely called commerce or financial transaction or barter. A network that allows trade is called a market. The original form of trade was barter, the direct exchange of goods and...

.

The chronological boundary points of the era are generally vague, largely since the label's origin in contemporary 18th century criticism has made it a shorthand designation for a somewhat nebulous age of satire. This new Augustan period

Augustus

Augustus ;23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14) is considered the first emperor of the Roman Empire, which he ruled alone from 27 BC until his death in 14 AD.The dates of his rule are contemporary dates; Augustus lived under two calendars, the Roman Republican until 45 BC, and the Julian...

exhibited exceptionally bold political writings in all genre

Genre

Genre , Greek: genos, γένος) is the term for any category of literature or other forms of art or culture, e.g. music, and in general, any type of discourse, whether written or spoken, audial or visual, based on some set of stylistic criteria. Genres are formed by conventions that change over time...

s, with the satires of the age marked by an arch, ironic pose, full of nuance, and a superficial air of dignified calm that hid sharp criticisms beneath.

As literacy

Literacy

Literacy has traditionally been described as the ability to read for knowledge, write coherently and think critically about printed material.Literacy represents the lifelong, intellectual process of gaining meaning from print...

(and London's population, especially) grew, literature began to appear from all over the kingdom

Kingdom of Great Britain

The former Kingdom of Great Britain, sometimes described as the 'United Kingdom of Great Britain', That the Two Kingdoms of Scotland and England, shall upon the 1st May next ensuing the date hereof, and forever after, be United into One Kingdom by the Name of GREAT BRITAIN. was a sovereign...

. Authors gradually began to accept literature that went in unique directions rather than the formerly monolithic conventions and, through this, slowly began to honor and recreate various folk

Folklore

Folklore consists of legends, music, oral history, proverbs, jokes, popular beliefs, fairy tales and customs that are the traditions of a culture, subculture, or group. It is also the set of practices through which those expressive genres are shared. The study of folklore is sometimes called...

compositions. Beneath the appearance of a placid and highly regulated series of writing modes, many developments of the later Romantic era were beginning to take place—while politically, philosophically, and literarily, modern

Modernism

Modernism, in its broadest definition, is modern thought, character, or practice. More specifically, the term describes the modernist movement, its set of cultural tendencies and array of associated cultural movements, originally arising from wide-scale and far-reaching changes to Western society...

consciousness

Consciousness

Consciousness is a term that refers to the relationship between the mind and the world with which it interacts. It has been defined as: subjectivity, awareness, the ability to experience or to feel, wakefulness, having a sense of selfhood, and the executive control system of the mind...

emerged from hitherto feudal and courtly

Nobility

Nobility is a social class which possesses more acknowledged privileges or eminence than members of most other classes in a society, membership therein typically being hereditary. The privileges associated with nobility may constitute substantial advantages over or relative to non-nobles, or may be...

notions.

Enlightenment? The historical context

"Augustan" derives from George I's wishing to be seen as Augustus Caesar. Alexander PopeAlexander Pope

Alexander Pope was an 18th-century English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer. He is the third-most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, after Shakespeare and Tennyson...

, who had been imitating Horace

Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus , known in the English-speaking world as Horace, was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus.-Life:...

, wrote an Epistle to Augustus that was to George II and seemingly endorsed the notion of his age being like that of Augustus, when poetry became more mannered, political and satirical than in the era of Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire....

(Thornton 275). Later, Voltaire

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet , better known by the pen name Voltaire , was a French Enlightenment writer, historian and philosopher famous for his wit and for his advocacy of civil liberties, including freedom of religion, free trade and separation of church and state...

and Oliver Goldsmith

Oliver Goldsmith

Oliver Goldsmith was an Irish writer, poet and physician known for his novel The Vicar of Wakefield , his pastoral poem The Deserted Village , and his plays The Good-Natur'd Man and She Stoops to Conquer...

(in his History of Literature in 1764) used the term "Augustan" to refer to the literature of the 1720s and '30s. Outside of poetry, however, the Augustan era is generally known by other names. Partially because of the rise of empiricism

Empiricism

Empiricism is a theory of knowledge that asserts that knowledge comes only or primarily via sensory experience. One of several views of epistemology, the study of human knowledge, along with rationalism, idealism and historicism, empiricism emphasizes the role of experience and evidence,...

and partially due to the self-conscious naming of the age in terms of ancient Rome

Ancient Rome

Ancient Rome was a thriving civilization that grew on the Italian Peninsula as early as the 8th century BC. Located along the Mediterranean Sea and centered on the city of Rome, it expanded to one of the largest empires in the ancient world....

, two imprecise labels have been affixed to the age. One is that it is the age of neoclassicism

Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism is the name given to Western movements in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that draw inspiration from the "classical" art and culture of Ancient Greece or Ancient Rome...

. The other is that it is the Age of Reason

Age of reason

Age of reason may refer to:* 17th-century philosophy, as a successor of the Renaissance and a predecessor to the Age of Enlightenment* Age of Enlightenment in its long form of 1600-1800* The Age of Reason, a book by Thomas Paine...

. Both terms have some usefulness, but both also obscure much. While neoclassical criticism from France was imported to English letters, the English had abandoned their strictures in all but name by the 1720s. As for whether the era was "the Enlightenment" or not, the critic Donald Greene

Donald Greene

Donald Johnson Greene was a literary critic, English professor, and scholar of British literature, particularly the eighteenth-century period. Known especially for his work on Samuel Johnson, he also wrote on later authors such as Jane Austen, Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, and Donald Davie.Greene...

wrote vigorously against its being so, arguing persuasively that the age should be known as "The Age of Exuberance," while T. H. White

T. H. White

Terence Hanbury White was an English author best known for his sequence of Arthurian novels, The Once and Future King, first published together in 1958.-Biography:...

made a case for "The Age of Scandal". More recently, Roy Porter

Roy Porter

Roy Sydney Porter was a British historian noted for his prolific work on the history of medicine.-Life:...

attempted again to argue for the developments of science dominating all other areas of endeavour in the age, unmistakably making it the Enlightenment.

Bartholomew Fair

Bartholomew Fayre: A Comedy is a comedy in five acts by Ben Jonson, the last written of his four great comedies. It was first staged on October 31, 1614 at the Hope Theatre by the Lady Elizabeth's Men...

and other fairs. Additionally, a brisk trade in chapbook

Chapbook

A chapbook is a pocket-sized booklet. The term chap-book was formalized by bibliophiles of the 19th century, as a variety of ephemera , popular or folk literature. It includes many kinds of printed material such as pamphlets, political and religious tracts, nursery rhymes, poetry, folk tales,...

s and broadsheet

Broadsheet

Broadsheet is the largest of the various newspaper formats and is characterized by long vertical pages . The term derives from types of popular prints usually just of a single sheet, sold on the streets and containing various types of material, from ballads to political satire. The first broadsheet...

s carried London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

trends and information out to the farthest reaches of the kingdom. This was only furthered with the establishment of periodicals, including The Gentleman's Magazine and the London Magazine. Not only, therefore, were people in York

York

York is a walled city, situated at the confluence of the Rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. The city has a rich heritage and has provided the backdrop to major political events throughout much of its two millennia of existence...

aware of the happenings of Parliament

Parliament

A parliament is a legislature, especially in those countries whose system of government is based on the Westminster system modeled after that of the United Kingdom. The name is derived from the French , the action of parler : a parlement is a discussion. The term came to mean a meeting at which...

and the court, but people in London were more aware than before of the happenings of York. Furthermore, in this age before copyright

Copyright

Copyright is a legal concept, enacted by most governments, giving the creator of an original work exclusive rights to it, usually for a limited time...

, pirate editions were commonplace, especially in areas without frequent contact with London. Pirate editions thereby encouraged booksellers to increase their shipments to outlying centers like Dublin, which increased, again, awareness across the whole realm. This was compounded by the end of the Press Restriction Act in 1693, which allowed for provincial printing presses to be established, creating a printing structure that was no longer under government control. (Clair 158-176)

All types of literature were spread quickly in all directions. Newspapers not only began, but they multiplied. Furthermore, the newspapers were immediately compromised, as the political factions created their own newspapers, planted stories, and bribed journalists. Leading clerics had their sermon collections printed, and these were top selling books. Since dissenting, Establishment, and Independent divines were in print, the constant movement of these works helped defuse any one region's religious homogeneity and fostered emergent latitudinarianism. Periodicals were exceedingly popular, and the art of essay writing was at nearly its apex. Furthermore, the happenings of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

were published regularly, and these events were digested and explained or celebrated in more popular presses. The latest books of scholarship had "keys" and "indexes" and "digests" made of them that could popularize, summarize, and explain them to a wide audience. The cross-index, now commonplace, was a novelty in the 18th century, and several persons created indexes for older books of learning, allowing anyone to find what an author had to say about a given topic at a moment's notice. Books of etiquette, of correspondence, and of moral instruction and hygiene multiplied. Economics

Economics

Economics is the social science that analyzes the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. The term economics comes from the Ancient Greek from + , hence "rules of the house"...

began as a serious discipline, but it did so in the form of numerous "projects" for solving England's (and Ireland's, and Scotland's) ills. Sermon collections, dissertations on religious controversy, and prophecies, both new and old and explained, cropped up in endless variety. In short, readers in the 18th century were overwhelmed by competing voices. True and false sat side by side on the shelves, and anyone could be a published author, just as anyone could quickly pretend to be a scholar by using indexes and digests (Clair 45, 158-187).

The positive side of the explosion in information was that the 18th century was markedly more generally educated than the centuries before. Education was less confined to the upper classes than it had been in prior centuries, and consequently contributions to science, philosophy, economics, and literature came from all parts of the newly United Kingdom. It was the first time when literacy and a library were all that stood between a person and education. It was an age of "enlightenment" in the sense that the insistence and drive for reasonable explanations of nature and mankind was a rage. It was an "age of reason" in that it was an age that accepted clear, rational methods as superior to tradition. However, there was a dark side to such literacy as well, a dark side which authors of the 18th century felt at every turn, and that was that nonsense and insanity were also getting more adherents than ever before. Charlatan

Charlatan

A charlatan is a person practicing quackery or some similar confidence trick in order to obtain money, fame or other advantages via some form of pretense or deception....

s and mountebanks were fooling more, just as sages were educating more, and alluring and lurid apocalypses

Apocalyptic literature

Apocalyptic literature is a genre of prophetical writing that developed in post-Exilic Jewish culture and was popular among millennialist early Christians....

vied with sober philosophy on the shelves. As with the world-wide web in the 21st century, the democratization of publishing meant that older systems for determining value and uniformity of view were both in shambles. Thus, it was increasingly difficult to trust books in the 18th century, because books were increasingly easy to make and buy.

Political and religious historical context

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also called the Revolution of 1688, is the overthrow of King James II of England by a union of English Parliamentarians with the Dutch stadtholder William III of Orange-Nassau...

, where Parliament set up a new rule for succession to the British throne

Succession to the British Throne

Succession to the British throne is governed both by common law and statute. Under common law the crown is currently passed on by male-preference primogeniture. In other words, succession passes first to an individual's sons, in order of birth, and subsequently to daughters, again in order of birth....

that would always favor Protestantism

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

over sanguinity. This had brought William and Mary

William and Mary

The phrase William and Mary usually refers to the coregency over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, of King William III & II and Queen Mary II...

to the throne instead of James II

James II of England

James II & VII was King of England and King of Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII, from 6 February 1685. He was the last Catholic monarch to reign over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland...

, and was codified in the Act of Settlement 1701

Act of Settlement 1701

The Act of Settlement is an act of the Parliament of England that was passed in 1701 to settle the succession to the English throne on the Electress Sophia of Hanover and her Protestant heirs. The act was later extended to Scotland, as a result of the Treaty of Union , enacted in the Acts of Union...

. James had fled to France from where his son James Francis Edward Stuart

James Francis Edward Stuart

James Francis Edward, Prince of Wales was the son of the deposed James II of England...

launched an attempt to retake the throne in 1715. Another attempt was launched by the latter's son Charles Edward Stuart

Charles Edward Stuart

Prince Charles Edward Louis John Casimir Sylvester Severino Maria Stuart commonly known as Bonnie Prince Charlie or The Young Pretender was the second Jacobite pretender to the thrones of Great Britain , and Ireland...

in 1745. The attempted invasions are often referred to as "the 15" and "the 45". When William died, Anne Stuart came to the throne. Anne was reportedly immoderately stupid: Thomas Babington Macaulay would say of Anne that "when in good humour, [she] was meekly stupid and, when in bad humour, was sulkily stupid." Anne's reign saw two wars and great triumphs by John Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough. Marlborough's wife, Sarah Churchill

Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough

Sarah Churchill , Duchess of Marlborough rose to be one of the most influential women in British history as a result of her close friendship with Queen Anne of Great Britain.Sarah's friendship and influence with Princess Anne was widely known, and leading public figures...

, was Anne's best friend, and many supposed that she secretly controlled the Queen in every respect. With a weak ruler and the belief that true power rested in the hands of the leading ministers, the two factions of politics stepped up their opposition to each other, and Whig

British Whig Party

The Whigs were a party in the Parliament of England, Parliament of Great Britain, and Parliament of the United Kingdom, who contested power with the rival Tories from the 1680s to the 1850s. The Whigs' origin lay in constitutional monarchism and opposition to absolute rule...

and Tory

Tory

Toryism is a traditionalist and conservative political philosophy which grew out of the Cavalier faction in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It is a prominent ideology in the politics of the United Kingdom, but also features in parts of The Commonwealth, particularly in Canada...

were at each others' throats. This weakness at the throne would lead quickly to the expansion of the powers of the party leader in Parliament and the establishment in all but name of the Prime Minister

Prime minister

A prime minister is the most senior minister of cabinet in the executive branch of government in a parliamentary system. In many systems, the prime minister selects and may dismiss other members of the cabinet, and allocates posts to members within the government. In most systems, the prime...

office in the form of Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, KG, KB, PC , known before 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British statesman who is generally regarded as having been the first Prime Minister of Great Britain....

. When Anne died without issue, George I, Elector of Hanover, came to the throne. George I never bothered to learn the English language, and his isolation from the English people was instrumental in keeping his power relatively irrelevant. His son, George II, on the other hand, spoke some English and some more French, and his was the first full Hanoverian rule in England. By that time, the powers of Parliament had silently expanded, and George II's power was perhaps equal only to that of Parliament.

London's population exploded spectacularly. During the Restoration, it grew from around 350,000 to 600,000 in 1700 (Old Bailey) (Millwall history). By 1800, it had reached 950,000. Not all of these residents were prosperous. The Enclosure Acts had destroyed lower-class farming in the countryside, and rural areas experienced painful poverty. When the Black Act

Black Act

The Black Act , was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain passed in 1723 during the reign King George I of Great Britain in response to the Waltham deer poachers and a group of bandits known as the "Wokingham Blacks". It made it a felony to appear armed in a park or warren, or to hunt or steal...

was expanded to cover all protestors to enclosure, the communities of the country poor were forced to migrate or suffer (see Thompson, Whigs). Therefore, young people from the country often moved to London with hopes of achieving success, and this swelled the ranks of the urban poor and cheap labor for city employers. It also meant an increase in numbers of criminals, prostitutes and beggars. The fears of property crime, rape, and starvation found in Augustan literature should be kept in the context of London's growth, as well as the depopulation of the countryside.

Jonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild was perhaps the most infamous criminal of London — and possibly Great Britain — during the 18th century, both because of his own actions and the uses novelists, playwrights, and political satirists made of them...

invented new schemes for stealing, and the newspapers were eager to report crime. Biographies of the daring criminals became popular, and these spawned fictional biographies of fictional criminals. Cautionary tales of country women abused by sophisticated rakes

Rake (character)

A rake, short for rakehell, is a historic term applied to a man who is habituated to immoral conduct, frequently a heartless womanizer. Often a rake was a man who wasted his fortune on gambling, wine, women and song, incurring lavish debts in the process...

(such as Anne Bond) and libertines in the city were popular fare, and these prompted fictional accounts of exemplary women abused (or narrowly escaping abuse).

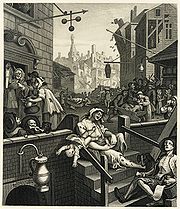

The population pressure also meant that urban discontent was never particularly difficult to find for political opportunists, and London suffered a number of riots, most of them against supposed Roman Catholic

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

agent provocateurs. When highly potent, inexpensive distilled spirits were introduced, matters worsened, and authors and artists protested the innovation of gin

Gin

Gin is a spirit which derives its predominant flavour from juniper berries . Although several different styles of gin have existed since its origins, it is broadly differentiated into two basic legal categories...

(see, e.g. William Hogarth

William Hogarth

William Hogarth was an English painter, printmaker, pictorial satirist, social critic and editorial cartoonist who has been credited with pioneering western sequential art. His work ranged from realistic portraiture to comic strip-like series of pictures called "modern moral subjects"...

's Gin Lane). From 1710, the government encouraged distilling as a source of revenue and trade goods, and there were no licenses required for the manufacturing or selling of gin. There were documented instances of women drowning their infants to sell the child's clothes for gin, and so these facilities created both the fodder for riots and the conditions against which riots would occur (Loughrey and Treadwell, 14). Dissenters (those radical Protestants who would not join with the Church of England

Church of England

The Church of England is the officially established Christian church in England and the Mother Church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church considers itself within the tradition of Western Christianity and dates its formal establishment principally to the mission to England by St...

) recruited and preached to the poor of the city, and various offshoots of the Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

and "Independent" (Baptist

Baptist

Baptists comprise a group of Christian denominations and churches that subscribe to a doctrine that baptism should be performed only for professing believers , and that it must be done by immersion...

) movements increased their numbers substantially. One theme of these ministers was the danger of the Roman Catholic Church, which they frequently saw as the Whore of Babylon

Whore of Babylon

The Whore of Babylon or "Babylon the great" is a Christian allegorical figure of evil mentioned in the Book of Revelation in the Bible. Her full title is given as "Babylon the Great, the Mother of Prostitutes and Abominations of the Earth." -Symbolism:...

. While Anne was high church

High church

The term "High Church" refers to beliefs and practices of ecclesiology, liturgy and theology, generally with an emphasis on formality, and resistance to "modernization." Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term has traditionally been principally associated with the...

, George I came from a far more Protestant

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

nation than England. The convocation

Convocation

A Convocation is a group of people formally assembled for a special purpose.- University use :....

was effectively disbanded by George I (who was struggling with the House of Lords

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

), and George II was pleased to keep it in abeyance. Additionally, both of the first two Hanoverians were concerned with James Francis Edward Stuart

James Francis Edward Stuart

James Francis Edward, Prince of Wales was the son of the deposed James II of England...

and Charles Edward Stuart

Charles Edward Stuart

Prince Charles Edward Louis John Casimir Sylvester Severino Maria Stuart commonly known as Bonnie Prince Charlie or The Young Pretender was the second Jacobite pretender to the thrones of Great Britain , and Ireland...

who had considerable support in Scotland and Ireland, and anyone too high church was suspected of being a closet Jacobite

Jacobitism

Jacobitism was the political movement in Britain dedicated to the restoration of the Stuart kings to the thrones of England, Scotland, later the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the Kingdom of Ireland...

, thanks in no small part to Walpole's inflating fears of Stuart sympathizers among any group that did not support him.

History and literature

The literature of the 18th century—particularly the early 18th century, which is what "Augustan" most commonly indicates—is explicitly political in ways that few others are. Because the professional author was still not distinguishable from the hack-writer, those who wrote poetry, novels, and plays were frequently either politically active or politically funded. At the same time, an aesthetic of artistic detachment from the everyday world had yet to develop, and the aristocratic ideal of an author so noble as to be above political concerns was largely archaic and irrelevant. The period may be an "Age of Scandal," for it is an age when authors dealt specifically with the crimes and vices of their world.Satire, both in prose, drama, and poetry, was the genre that attracted the most energetic and voluminous writing. The satires produced during the Augustan period were occasionally gentle and non-specific—commentaries on the comically flawed human condition—but they were at least as frequently specific critiques of specific policies, actions, and persons. Even those works studiously non-topical were, in fact, transparently political statements in the 18th century. Consequently, readers of 18th-century literature today need to understand the history of the period more than most readers of other literature do. The authors were writing for an informed audience and only secondarily for posterity. Even the authors who criticized writing that lived for only a day (e.g. Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift was an Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer , poet and cleric who became Dean of St...

and Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope was an 18th-century English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer. He is the third-most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, after Shakespeare and Tennyson...

, in The Dedication to Prince Posterity of A Tale of a Tub

A Tale of a Tub

A Tale of a Tub was the first major work written by Jonathan Swift, composed between 1694 and 1697 and published in 1704. It is arguably his most difficult satire, and perhaps his most masterly...

and Dunciad, among other pieces) were criticizing specific authors who are unknown without historical knowledge of the period. 18th-century poetry of all forms was in constant dialog: each author was responding and commenting upon the others. 18th-century novels were written against other 18th-century novels (e.g. the battles between Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding was an English novelist and dramatist known for his rich earthy humour and satirical prowess, and as the author of the novel Tom Jones....

and Samuel Richardson

Samuel Richardson

Samuel Richardson was an 18th-century English writer and printer. He is best known for his three epistolary novels: Pamela: Or, Virtue Rewarded , Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady and The History of Sir Charles Grandison...

and between Laurence Sterne

Laurence Sterne

Laurence Sterne was an Irish novelist and an Anglican clergyman. He is best known for his novels The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, and A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy; but he also published many sermons, wrote memoirs, and was involved in local politics...

and Tobias Smollett

Tobias Smollett

Tobias George Smollett was a Scottish poet and author. He was best known for his picaresque novels, such as The Adventures of Roderick Random and The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle , which influenced later novelists such as Charles Dickens.-Life:Smollett was born at Dalquhurn, now part of Renton,...

). Plays were written to make fun of plays, or to counter the success of plays (e.g. the reaction against and for Cato and, later, Fielding's The Author's Farce

The Author's Farce

The Author's Farce and the Pleasures of the Town is a play by the English playwright and novelist Henry Fielding, first performed on 30 March 1730 at the Little Theatre, Haymarket. Written in response to the Theatre Royal's rejection of his earlier plays, The Author's Farce was Fielding's...

). Therefore, history and literature are linked in a way rarely seen at other times. On the one hand, this metropolitan and political writing can seem like coterie or salon work, but, on the other, it was the literature of people deeply committed to sorting out a new type of government, new technologies, and newly vexatious challenges to philosophical and religious certainty.

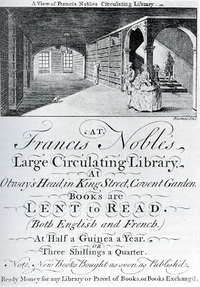

Prose

Essay

An essay is a piece of writing which is often written from an author's personal point of view. Essays can consist of a number of elements, including: literary criticism, political manifestos, learned arguments, observations of daily life, recollections, and reflections of the author. The definition...

, satire, and dialogue

Dialogue

Dialogue is a literary and theatrical form consisting of a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people....

(in philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

and religion) thrived in the age, and the English novel

English novel

The English novel is an important part of English literature.-Early novels in English:A number of works of literature have each been claimed as the first novel in English. See the article First novel in English.-Romantic novel:...

was truly begun as a serious art form. Literacy in the early 18th century passed into the working classes, as well as the middle and upper classes (Thompson, Class). Furthermore, literacy was not confined to men, though rates of female literacy are very difficult to establish. For those who were literate, circulating libraries

Library

In a traditional sense, a library is a large collection of books, and can refer to the place in which the collection is housed. Today, the term can refer to any collection, including digital sources, resources, and services...

in England began in the Augustan period. Libraries were open to all, but they were mainly associated with female patronage and novel reading.

The essay/journalism

English essayists were aware of Continental models, but they developed their form independently from that tradition, and periodical literature grew between 1692 and 1712. Periodicals were inexpensive to produce, quick to read, and a viable way of influencing public opinion, and consequently there were many broadsheet periodicals headed by a single author and staffed by hirelings (so-called "Grub Street" authors). One periodical outsold and dominated all others, however, and that was The SpectatorThe Spectator (1711)

The Spectator was a daily publication of 1711–12, founded by Joseph Addison and Richard Steele in England after they met at Charterhouse School. Eustace Budgell, a cousin of Addison's, also contributed to the publication. Each 'paper', or 'number', was approximately 2,500 words long, and the...

, written by Joseph Addison

Joseph Addison

Joseph Addison was an English essayist, poet, playwright and politician. He was a man of letters, eldest son of Lancelot Addison...

and Richard Steele

Richard Steele

Sir Richard Steele was an Irish writer and politician, remembered as co-founder, with his friend Joseph Addison, of the magazine The Spectator....

(with occasional contributions from their friends). The Spectator developed a number of pseudonymous characters, including "Mr. Spectator," Roger de Coverley

Roger de Coverley

Roger de Coverley is the name of an English country dance and a Scottish country dance . An early version was published in The Dancing Master, 9th edition . The Virginia Reel is probably related to it...

, and "Isaac Bickerstaff

Isaac Bickerstaff

Isaac Bickerstaff Esq was a pseudonym used by Jonathan Swift as part of a hoax to predict the death of then famous Almanac–maker and astrologer John Partridge....

", and both Addison and Steele created fictions to surround their narrators. The dispassionate view of the world (the pose of a spectator, rather than participant) was essential for the development of the English essay, as it set out a ground wherein Addison and Steele could comment and meditate upon manners and events. Rather than being philosophers like Montesquieu

Charles de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu

Charles-Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu , generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French social commentator and political thinker who lived during the Enlightenment...

, the English essayist could be an honest observer and his reader's peer. After the success of The Spectator, more political periodicals of comment appeared. However, the political factions and coalitions of politicians very quickly realized the power of this type of press, and they began funding newspapers to spread rumors. The Tory ministry of Robert Harley

Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Mortimer

Robert Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer KG was a British politician and statesman of the late Stuart and early Georgian periods. He began his career as a Whig, before defecting to a new Tory Ministry. Between 1711 and 1714 he served as First Lord of the Treasury, effectively Queen...

(1710–1714) reportedly spent over 50,000 pounds sterling on creating and bribing the press (Butt); we know this figure because their successors publicized it, but they (the Walpole government) were suspected of spending even more. Politicians wrote papers, wrote into papers, and supported papers, and it was well known that some of the periodicals, like Mist's Journal, were party mouthpieces.

Philosophy and religious writing

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

writing: Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe , born Daniel Foe, was an English trader, writer, journalist, and pamphleteer, who gained fame for his novel Robinson Crusoe. Defoe is notable for being one of the earliest proponents of the novel, as he helped to popularise the form in Britain and along with others such as Richardson,...

. After the coronation of Anne, dissenter hopes of reversing the Restoration were at an ebb, and dissenter literature moved from the offensive to the defensive, from revolutionary to conservative. Defoe's infamous volley in the struggle between high and low church came in the form of The Shortest Way with the Dissenters; Or, Proposals for the Establishment of the Church. The work is satirical, attacking all of the worries of Establishment figures over the challenges of dissenters. It is, in other words, defensive. Later still, the most majestic work of the era, and the one most quoted and read, was William Law

William Law

William Law was an English cleric, divine and theological writer.-Early life:Law was born at Kings Cliffe, Northamptonshire in 1686. In 1705 he entered as a sizar at Emmanuel College, Cambridge; in 1711 he was elected fellow of his college and was ordained...

's A Serious Call to a Devout and Holy Life (1728). The Meditations of Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle FRS was a 17th century natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, and inventor, also noted for his writings in theology. He has been variously described as English, Irish, or Anglo-Irish, his father having come to Ireland from England during the time of the English plantations of...

remained popular as well. Both Law and Boyle called for revivalism, and they set the stage for the later development of Methodism

Methodism

Methodism is a movement of Protestant Christianity represented by a number of denominations and organizations, claiming a total of approximately seventy million adherents worldwide. The movement traces its roots to John Wesley's evangelistic revival movement within Anglicanism. His younger brother...

and George Whitefield

George Whitefield

George Whitefield , also known as George Whitfield, was an English Anglican priest who helped spread the Great Awakening in Britain, and especially in the British North American colonies. He was one of the founders of Methodism and of the evangelical movement generally...

's sermon style. However, their works aimed at the individual, rather than the community. The age of revolutionary divines and militant evangelists in literature was over for a considerable time.

Also in contrast to the Restoration, when philosophy in England was fully dominated by John Locke

John Locke

John Locke FRS , widely known as the Father of Liberalism, was an English philosopher and physician regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers. Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, following the tradition of Francis Bacon, he is equally important to social...

, the 18th century had a vigorous competition among followers of Locke. Bishop Berkeley

George Berkeley

George Berkeley , also known as Bishop Berkeley , was an Irish philosopher whose primary achievement was the advancement of a theory he called "immaterialism"...

extended Locke's emphasis on perception to argue that perception entirely solves the Cartesian

René Descartes

René Descartes ; was a French philosopher and writer who spent most of his adult life in the Dutch Republic. He has been dubbed the 'Father of Modern Philosophy', and much subsequent Western philosophy is a response to his writings, which are studied closely to this day...

problem of subjective and objective knowledge by saying "to be is to be perceived." Only, Berkeley argued, those things that are perceived by a consciousness are real. For Berkeley, the persistence of matter rests in the fact that God

God

God is the English name given to a singular being in theistic and deistic religions who is either the sole deity in monotheism, or a single deity in polytheism....

perceives those things that humans are not, that a living and continually aware, attentive, and involved God is the only rational explanation for the existence of objective matter. In essence, then, Berkeley's skepticism leads to faith. David Hume

David Hume

David Hume was a Scottish philosopher, historian, economist, and essayist, known especially for his philosophical empiricism and skepticism. He was one of the most important figures in the history of Western philosophy and the Scottish Enlightenment...

, on the other hand, took empiricist skepticism to its extremes, and he was the most radically empiricist philosopher of the period. He attacked surmise and unexamined premises wherever he found them, and his skepticism pointed out metaphysics

Metaphysics

Metaphysics is a branch of philosophy concerned with explaining the fundamental nature of being and the world, although the term is not easily defined. Traditionally, metaphysics attempts to answer two basic questions in the broadest possible terms:...

in areas that other empiricists had assumed were material. Hume doggedly refused to enter into questions of his personal faith in the divine, but his assault on the logic and assumptions of theodicy

Theodicy

Theodicy is a theological and philosophical study which attempts to prove God's intrinsic or foundational nature of omnibenevolence , omniscience , and omnipotence . Theodicy is usually concerned with the God of the Abrahamic religions Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, due to the relevant...

and cosmogeny was devastating, and he concentrated on the provable and empirical in a way that would lead to utilitarianism

Utilitarianism

Utilitarianism is an ethical theory holding that the proper course of action is the one that maximizes the overall "happiness", by whatever means necessary. It is thus a form of consequentialism, meaning that the moral worth of an action is determined only by its resulting outcome, and that one can...

and naturalism

Humanistic naturalism

Humanistic naturalism is the branch of philosophical naturalism wherein human beings are best able to control and understand the world through use of the scientific method. Concepts of spirituality, intuition, and metaphysics are not pursued because they are unfalsifiable, and therefore can never...

later.

In social and political philosophy, economics underlies much of the debate. Bernard de Mandeville's The Fable of the Bees (1714) became a center point of controversy regarding trade, morality, and social ethics. Mandeville argued that wastefulness, lust, pride, and all the other "private" vices were good for the society at large, for each led the individual to employ others, to spend freely, and to free capital to flow through the economy. Mandeville's work is full of paradox and is meant, at least partially, to problematize what he saw as the naive philosophy of human progress and inherent virtue. However, Mandeville's arguments, initially an attack on graft of the War of the Spanish Succession

War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was fought among several European powers, including a divided Spain, over the possible unification of the Kingdoms of Spain and France under one Bourbon monarch. As France and Spain were among the most powerful states of Europe, such a unification would have...

, would be quoted often by economists who wished to strip morality away from questions of trade.

Adam Smith is remembered by lay persons as the father of capitalism

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system that became dominant in the Western world following the demise of feudalism. There is no consensus on the precise definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category...

, but his Theory of Moral Sentiments of 1759 also attempted to strike out a new ground for moral action. His emphasis on "sentiment" was in keeping with the era, as he emphasized the need for "sympathy" between individuals as the basis of fit action. These ideas, and the psychology of David Hartley

David Hartley

David Hartley may refer to:*David Hartley , English philosopher*David Hartley , son of the philosopher, and signatory to the Treaty of Paris*David Hartley...

, were influential on the sentimental novel

Sentimental novel

The sentimental novel or the novel of sensibility is an 18th century literary genre which celebrates the emotional and intellectual concepts of sentiment, sentimentalism, and sensibility...

and even the nascent Methodist movement. If sympathetic sentiment communicated morality, would it not be possible to induce morality by providing sympathetic circumstances? Smith's greatest work was An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations in 1776. What it held in common with de Mandeville, Hume, and Locke was that it began by analytically examining the history of material exchange, without reflection on morality. Instead of deducing from the ideal or moral to the real, it examined the real and tried to formulate inductive rules.

The novel

The ground for the novel had been laid by journalism, drama and satire. Long prose satires like Swift's Gulliver's TravelsGulliver's Travels

Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships, better known simply as Gulliver's Travels , is a novel by Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan Swift that is both a satire on human nature and a parody of...

(1726) had a central character who goes through adventures and may (or may not) learn lessons. However, the most important single satirical source for the writing of novels came from Cervantes

Cervantes

-People:*Alfonso J. Cervantes , mayor of St. Louis, Missouri*Francisco Cervantes de Salazar, 16th-century man of letters*Ignacio Cervantes, Cuban composer*Jorge Cervantes, a world-renowned expert on indoor, outdoor, and greenhouse cannabis cultivation...

's Don Quixote (1605, 1615). In general, one can see these three axes, drama, journalism, and satire, as blending in and giving rise to three different types of novel.

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe , born Daniel Foe, was an English trader, writer, journalist, and pamphleteer, who gained fame for his novel Robinson Crusoe. Defoe is notable for being one of the earliest proponents of the novel, as he helped to popularise the form in Britain and along with others such as Richardson,...

's Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe is a novel by Daniel Defoe that was first published in 1719. Epistolary, confessional, and didactic in form, the book is a fictional autobiography of the title character—a castaway who spends 28 years on a remote tropical island near Trinidad, encountering cannibals, captives, and...

(1719) was the first major novel of the new century and was published in more editions than any other works besides Gulliver's Travels (Mullan 252). Defoe worked as a journalist during and after its composition, and therefore he encountered the memoirs of Alexander Selkirk

Alexander Selkirk

Alexander Selkirk was a Scottish sailor who spent four years as a castaway when he was marooned on an uninhabited island. It is probable that his travels provided the inspiration for Daniel Defoe's novel Robinson Crusoe....

, who had been stranded in South America on an island for some years. Defoe took aspects of the actual life and, from that, generated a fictional life, satisfying an essentially journalistic market with his fictio (Hunter 331-338). In the 1720s, Defoe interviewed famed criminals and produced accounts of their lives. In particular, he investigated Jack Sheppard

Jack Sheppard

Jack Sheppard was a notorious English robber, burglar and thief of early 18th-century London. Born into a poor family, he was apprenticed as a carpenter but took to theft and burglary in 1723, with little more than a year of his training to complete...

and Jonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild

Jonathan Wild was perhaps the most infamous criminal of London — and possibly Great Britain — during the 18th century, both because of his own actions and the uses novelists, playwrights, and political satirists made of them...

and wrote True Accounts of the former's escapes (and fate) and the latter's life. From his reportage on the prostitutes and criminals, Defoe may have become familiar with the real-life Mary Mollineaux, who may have been the model for Moll in Moll Flanders (1722). In the same year, Defoe produced A Journal of the Plague Year (1722), which summoned up the horrors and tribulations of 1665 for a journalistic market for memoirs, and an attempted tale of a working-class male rise in Colonel Jack (1722). His last novel returned to the theme of fallen women in Roxana (1724). Thematically, Defoe's works are consistently Puritan. They all involve a fall, a degradation of the spirit, a conversion, and an ecstatic elevation. This religious structure necessarily involved a bildungsroman

Bildungsroman

In literary criticism, bildungsroman or coming-of-age story is a literary genre which focuses on the psychological and moral growth of the protagonist from youth to adulthood , and in which character change is thus extremely important...

, for each character had to learn a lesson about him or herself and emerge the wiser.

Samuel Richardson

Samuel Richardson was an 18th-century English writer and printer. He is best known for his three epistolary novels: Pamela: Or, Virtue Rewarded , Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady and The History of Sir Charles Grandison...

's Pamela, or, Virtue Rewarded (1740) is the next landmark development in the English novel. Richardson's generic models were quite distinct from those of Defoe. Instead of working from the journalistic biography

Biography

A biography is a detailed description or account of someone's life. More than a list of basic facts , biography also portrays the subject's experience of those events...

, Richardson had in mind the books of improvement that were popular at the time. Pamela Andrews enters the employ of a "Mr. B." As a dutiful girl, she writes to her mother constantly, and as a Christian girl, she is always on guard for her "virtue" (i.e. her virginity), for Mr. B lusts after her. The novel ends with her marriage to her employer and her rising to the position of lady

Lady

The word lady is a polite term for a woman, specifically the female equivalent to, or spouse of, a lord or gentleman, and in many contexts a term for any adult woman...

. Pamela, like its author, presents a dissenter's and a Whig's view of the rise of the classes. The work drew a nearly instantaneous set of satires, of which Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding

Henry Fielding was an English novelist and dramatist known for his rich earthy humour and satirical prowess, and as the author of the novel Tom Jones....

's Shamela, or an Apology for the Life of Miss Shamela Andrews (1742) is the most memorable. Fielding continued to bait Richardson with Joseph Andrews

Joseph Andrews

Joseph Andrews, or The History of the Adventures of Joseph Andrews and of his Friend Mr. Abraham Adams, was the first published full-length novel of the English author and magistrate Henry Fielding, and indeed among the first novels in the English language...

(1742), the tale of Shamela's brother, Joseph, who goes through his life trying to protect his own virginity, thus reversing the sexual predation of Richardson and satirizing the idea of sleeping one's way to rank. However, Joseph Andrews is not a parody of Richardson, for Fielding proposed his belief in "good nature," which is a quality of inherent virtue that is independent of class and which can always prevail. Joseph's friend Parson Adams, although not a fool, is a naïf and possessing good nature. His own basic good nature blinds him to the wickedness of the world, and the incidents on the road (for most of the novel is a travel story) allow Fielding to satirize conditions for the clergy, rural poverty (and squires), and the viciousness of businessmen.

In 1747 through 1748, Samuel Richardson published Clarissa

Clarissa

Clarissa, or, the History of a Young Lady is an epistolary novel by Samuel Richardson, published in 1748. It tells the tragic story of a heroine whose quest for virtue is continually thwarted by her family, and is the longest real novelA completed work that has been released by a publisher in...

in serial form. Unlike Pamela, it is not a tale of virtue rewarded. Instead, it is a highly tragic and affecting account of a young girl whose parents try to force her into an uncongenial marriage, thus pushing her into the arms of a scheming rake

Rake (character)

A rake, short for rakehell, is a historic term applied to a man who is habituated to immoral conduct, frequently a heartless womanizer. Often a rake was a man who wasted his fortune on gambling, wine, women and song, incurring lavish debts in the process...

named Lovelace. In the end, Clarissa dies by her own will. The novel is a masterpiece of psychological realism

Psychological novel

A psychological novel, also called psychological realism, is a work of prose fiction which places more than the usual amount of emphasis on interior characterization, and on the motives, circumstances, and internal action which springs from, and develops, external action...

and emotional effect, and when Richardson was drawing to a close in the serial publication, even Henry Fielding wrote to him, begging him not to kill Clarissa. As with Pamela, Richardson emphasized the individual over the social and the personal over the class. Even as Fielding was reading and enjoying Clarissa, he was also writing a counter to its messages. His Tom Jones

The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling

The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling, often known simply as Tom Jones, is a comic novel by the English playwright and novelist Henry Fielding. First published on 28 February 1749, Tom Jones is among the earliest English prose works describable as a novel...

of 1749 offers up the other side of the argument from Clarissa. Tom Jones agrees substantially in the power of the individual to be more or less than his or her birth would indicate, but it again emphasizes the place of the individual in society and the social ramifications of individual choices. Fielding answers Richardson by featuring a similar plot device (whether a girl can choose her own mate) but showing how family and village can complicate and expedite matches and felicity.

Laurence Sterne

Laurence Sterne was an Irish novelist and an Anglican clergyman. He is best known for his novels The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, and A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy; but he also published many sermons, wrote memoirs, and was involved in local politics...

's and Tobias Smollett

Tobias Smollett

Tobias George Smollett was a Scottish poet and author. He was best known for his picaresque novels, such as The Adventures of Roderick Random and The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle , which influenced later novelists such as Charles Dickens.-Life:Smollett was born at Dalquhurn, now part of Renton,...

's works offered up oppositional views of the self in society and the method of the novel. The clergyman Laurence Sterne consciously set out to imitate Jonathan Swift with his Tristram Shandy (1759–1767). Tristram seeks to write his autobiography

Autobiography

An autobiography is a book about the life of a person, written by that person.-Origin of the term:...

, but like Swift's narrator in A Tale of a Tub

A Tale of a Tub

A Tale of a Tub was the first major work written by Jonathan Swift, composed between 1694 and 1697 and published in 1704. It is arguably his most difficult satire, and perhaps his most masterly...

, he worries that nothing in his life can be understood without understanding its context. For example, he tells the reader that at the very moment he was conceived, his mother was saying, "Did you wind the clock?" To explain how he knows this, he explains that his father took care of winding the clock and "other family business" on one day a month. To explain why the clock had to be wound then, he has to explain his father. In other words, the biography moves backward rather than forward in time, only to then jump forward years, hit another knot, and move backward again. It is a novel of exceptional energy, of multi-layered digression

Digression

Digression is a section of a composition or speech that is an intentional change of subject. In Classical rhetoric since Corax of Syracuse, especially in Institutio Oratoria of Quintilian, the digression was a regular part of any oration or composition...

s, of multiple satires, and of frequent parodies. Journalist, translator, and historian Tobias Smollett

Tobias Smollett

Tobias George Smollett was a Scottish poet and author. He was best known for his picaresque novels, such as The Adventures of Roderick Random and The Adventures of Peregrine Pickle , which influenced later novelists such as Charles Dickens.-Life:Smollett was born at Dalquhurn, now part of Renton,...

, on the other hand, wrote more seemingly traditional novels. He concentrated on the picaresque novel, where a low-born character would go through a practically endless series of adventures. Sterne thought that Smollett's novels always paid undue attention to the basest and most common elements of life, that they emphasized the dirt. Although this is a superficial complaint, it points to an important difference between the two as authors. Sterne came to the novel from a satirical background, while Smollett approached it from journalism. In the 19th century, novelists would have plots much nearer to Smollett's than either Fielding's or Sterne's or Richardson's, and his sprawling, linear development of action would prove most successful.

In the midst of this development of the novel, other trends were taking place. The novel of sentiment was beginning in the 1760s and would experience a brief period of dominance. This type of novel emphasized sympathy. In keeping with the theories of Adam Smith and David Hartley (see above), the sentimental novel

Sentiment

Sentiment can refer to activity of five material senses mistaking them as transcendental:*Feelings and emotions...

concentrated on emotionally labile characters capable of extraordinary empathy. Sarah Fielding

Sarah Fielding

Sarah Fielding was a British author and sister of the novelist Henry Fielding. She was the author of The Governess, or The Little Female Academy , which was the first novel in English written especially for children , and had earlier achieved success with her novel The Adventures of David Simple...

's David Simple outsold her brother Henry Fielding's Joseph Andrews and took the theory of "good nature" to be a sentimental nature. Other women were also writing novels and moving away from the old romance plots that had dominated before the Restoration. There were utopian novels, like Sarah Scott

Sarah Scott

Sarah Scott was an English novelist, translator, and social reformer. Her father, Matthew Robinson, and her mother, Elizabeth Robinson, were both from distinguished families, and Sarah was one of nine children who survived to adulthood...

's Millennium Hall (1762), autobiographical women's novels like Frances Burney's works, female adaptations of older, male motifs, such as Charlotte Lennox

Charlotte Lennox

Charlotte Lennox was an English author and poet. She is most famous now as the author of The Female Quixote and for her association with Samuel Johnson, Joshua Reynolds, and Samuel Richardson, but she had a long career and wrote poetry, prose, and drama.-Life:Charlotte Lennox was born in Gibraltar...

's The Female Quixote (1752) and many others. These novels do not generally follow a strict line of development or influence. However, they were popular works that were celebrated by both male and female readers and critics.

Historians of the novel

Ian WattIan Watt

Ian Watt was a literary critic, literary historian and professor of English at Stanford University. His Rise of the Novel: Studies in Defoe, Richardson and Fielding is an important work in the history of the genre...

's The Rise of the Novel (1957) still dominates attempts at writing a history of the novel. Watt's view is that the critical feature of the 18th-century novel is the creation of psychological realism. This feature, he argued, would continue on and influence the novel as it has been known in the 20th century. Michael McKeon brought a Marxist

Marxism

Marxism is an economic and sociopolitical worldview and method of socioeconomic inquiry that centers upon a materialist interpretation of history, a dialectical view of social change, and an analysis and critique of the development of capitalism. Marxism was pioneered in the early to mid 19th...

approach to the history of the novel in his 1986 The Origins of the English Novel. McKeon viewed the novel as emerging as a constant battleground between two developments of two sets of world view that corresponded to Whig/Tory, Dissenter/Establishment, and Capitalist/Persistent Feudalist.

Satire (unclassified)

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift was an Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer , poet and cleric who became Dean of St...

. Swift wrote poetry as well as prose, and his satires range over all topics. Critically, Swift's satire marked the development of prose parody away from simple satire or burlesque. A burlesque or lampoon in prose would imitate a despised author and quickly move to reductio ad absurdum

Reductio ad absurdum

In logic, proof by contradiction is a form of proof that establishes the truth or validity of a proposition by showing that the proposition's being false would imply a contradiction...

by having the victim say things coarse or idiotic. On the other hand, other satires would argue against a habit, practice, or policy by making fun of its reach or composition or methods. What Swift did was to combine parody

Parody

A parody , in current usage, is an imitative work created to mock, comment on, or trivialise an original work, its subject, author, style, or some other target, by means of humorous, satiric or ironic imitation...

, with its imitation of form and style of another, and satire in prose. Swift's works would pretend to speak in the voice of an opponent and imitate the style of the opponent and have the parodic work itself be the satire. Swift's first major satire was A Tale of a Tub

A Tale of a Tub

A Tale of a Tub was the first major work written by Jonathan Swift, composed between 1694 and 1697 and published in 1704. It is arguably his most difficult satire, and perhaps his most masterly...

(1703–1705), which introduced an ancients/moderns division that would serve as a distinction between the old and new conception of value. The "moderns" sought trade, empirical science, the individual's reason above the society's, while the "ancients" believed in inherent and immanent value of birth, and the society over the individual's determinations of the good. In Swift's satire, the moderns come out looking insane and proud of their insanity, and dismissive of the value of history. In Swift's most significant satire, Gulliver's Travels

Gulliver's Travels

Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships, better known simply as Gulliver's Travels , is a novel by Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan Swift that is both a satire on human nature and a parody of...

(1726), autobiography, allegory, and philosophy mix together in the travels. Thematically, Gulliver's Travels is a critique of human vanity, of pride. Book one, the journey to Liliput, begins with the world as it is. Book two shows that the idealized nation of Brobdingnag with a philosopher king

Philosopher king

Philosopher kings are the rulers, or Guardians, of Plato's Utopian Kallipolis. If his ideal city-state is to ever come into being, "philosophers [must] become kings…or those now called kings [must]…genuinely and adequately philosophize" .-In Book VI of The Republic:Plato defined a philosopher...

is no home for a contemporary Englishman. Book four depicts the land of the Houyhnhnms, a society of horses ruled by pure reason, where humanity itself is portrayed as a group of "yahoos" covered in filth and dominated by base desires. It shows that, indeed, the very desire for reason may be undesirable, and humans must struggle to be neither Yahoos nor Houyhnhnms, for book three shows what happens when reason is unleashed without any consideration of morality or utility (i.e. madness, ruin, and starvation).

There were other satirists who worked in a less virulent way, who took a bemused pose and only made lighthearted fun. Tom Brown

Tom Brown (satirist)

Tom Brown was an English translator and writer of satire, largely forgotten today save for a four-line gibe he wrote concerning Dr John Fell....

, Ned Ward

Ned Ward

Ned Ward , also known as Edward Ward, was a satirical writer and publican in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century based in London, England. His most famous work is The London Spy. Published in 18 monthly instalments starting in November 1698 it was described as a "complete survey" of...

, and Tom D'Urfey were all satirists in prose and poetry whose works appeared in the early part of the Augustan age. Tom Brown's most famous work in this vein was Amusements Serious and Comical, Calculated for the Meridian of London (1700). Ned Ward's most memorable work was The London Spy (1704–1706). The London Spy, before The Spectator, took up the position of an observer and uncomprehendingly reporting back. Tom D'Urfey's Wit and Mirth: or Pills to Purge Melancholy (1719) was another satire that attempted to offer entertainment, rather than a specific bit of political action, in the form of coarse and catchy songs.

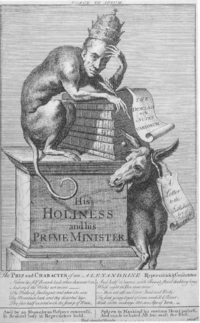

Particularly after Swift's success, parodic satire had an attraction for authors throughout the 18th century. A variety of factors created a rise in political writing and political satire, and Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford, KG, KB, PC , known before 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British statesman who is generally regarded as having been the first Prime Minister of Great Britain....

's success and domination of House of Commons

British House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which also comprises the Sovereign and the House of Lords . Both Commons and Lords meet in the Palace of Westminster. The Commons is a democratically elected body, consisting of 650 members , who are known as Members...

was a very effective proximal cause for polarized literature and thereby the rise of parodic satire. The parodic satire takes apart the cases and plans of policy without necessarily contrasting a normative or positive set of values. Therefore, it was an ideal method of attack for ironists and conservatives—those who would not be able to enunciate a set of values to change toward but could condemn present changes as ill-considered. Satire was present in all genres during the Augustan period. Perhaps primarily, satire was a part of political and religious debate. Every significant politician and political act had satires to attack it. Few of these were parodic satires, but parodic satires, too, emerged in political and religious debate. So omnipresent and powerful was satire in the Augustan age that more than one literary history has referred to it as the "Age of satire" in literature.

Poetry

In the Augustan era, poets wrote in direct counterpoint and direct expansion of one another, with each poet writing satire when in opposition. There was a great struggle over the nature and role of the pastoralPastoral

The adjective pastoral refers to the lifestyle of pastoralists, such as shepherds herding livestock around open areas of land according to seasons and the changing availability of water and pasturage. It also refers to a genre in literature, art or music that depicts such shepherd life in an...

in the early part of the century, reflecting two simultaneous movements: the invention of the subjective self as a worthy topic, with the emergence of a priority on individual psychology, against the insistence on all acts of art being performance and public gesture designed for the benefit of society at large. The development seemingly agreed upon by both sides was a gradual adaptation of all forms of poetry from their older uses. Ode

Ode

Ode is a type of lyrical verse. A classic ode is structured in three major parts: the strophe, the antistrophe, and the epode. Different forms such as the homostrophic ode and the irregular ode also exist...