Restoration literature

Encyclopedia

English literature

English literature is the literature written in the English language, including literature composed in English by writers not necessarily from England; for example, Robert Burns was Scottish, James Joyce was Irish, Joseph Conrad was Polish, Dylan Thomas was Welsh, Edgar Allan Poe was American, J....

written during the historical period commonly referred to as the English Restoration (1660–1689), which corresponds to the last years of the direct Stuart

House of Stuart

The House of Stuart is a European royal house. Founded by Robert II of Scotland, the Stewarts first became monarchs of the Kingdom of Scotland during the late 14th century, and subsequently held the position of the Kings of Great Britain and Ireland...

reign in England, Scotland, Wales

Wales

Wales is a country that is part of the United Kingdom and the island of Great Britain, bordered by England to its east and the Atlantic Ocean and Irish Sea to its west. It has a population of three million, and a total area of 20,779 km²...

, and Ireland. In general, the term is used to denote roughly homogeneous styles of literature that center on a celebration of or reaction to the restored court of Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

. It is a literature that includes extremes, for it encompasses both Paradise Lost

Paradise Lost

Paradise Lost is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton. It was originally published in 1667 in ten books, with a total of over ten thousand individual lines of verse...

and the Earl of Rochester

John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester

John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester , styled Viscount Wilmot between 1652 and 1658, was an English Libertine poet, a friend of King Charles II, and the writer of much satirical and bawdy poetry. He was the toast of the Restoration court and a patron of the arts...

's Sodom

Sodom, or the Quintessence of Debauchery

Sodom is an obscene Restoration closet drama, published in 1684. The work has been attributed to John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester., though its authorship is disputed...

, the high-spirited sexual comedy

Sex comedy

Sex comedy is a term for comedy movies with sexual content usually referring to those made in the United Kingdom in the mid 1970s. They may range from comic pornographic films like the Confessions series to relatively innocent comedies that include jokes about sex and other sexual related humour,...

of The Country Wife

The Country Wife

The Country Wife is a Restoration comedy written in 1675 by William Wycherley. A product of the tolerant early Restoration period, the play reflects an aristocratic and anti-Puritan ideology, and was controversial for its sexual explicitness even in its own time. The title itself contains a lewd pun...

and the moral wisdom of The Pilgrim's Progress

The Pilgrim's Progress

The Pilgrim's Progress from This World to That Which Is to Come is a Christian allegory written by John Bunyan and published in February, 1678. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of religious English literature, has been translated into more than 200 languages, and has never been...

. It saw Locke

John Locke

John Locke FRS , widely known as the Father of Liberalism, was an English philosopher and physician regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers. Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, following the tradition of Francis Bacon, he is equally important to social...

's Treatises of Government

Two Treatises of Government

The Two Treatises of Government is a work of political philosophy published anonymously in 1689 by John Locke...

, the founding of the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

, the experiments and holy meditations of Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle FRS was a 17th century natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, and inventor, also noted for his writings in theology. He has been variously described as English, Irish, or Anglo-Irish, his father having come to Ireland from England during the time of the English plantations of...

, the hysterical attacks on theaters from Jeremy Collier

Jeremy Collier

Jeremy Collier was an English theatre critic, non-juror bishop and theologian.-Life:Born in Stow cum Quy, Cambridgeshire, Collier was educated at Caius College, University of Cambridge, receiving the BA and MA . A supporter of James II, he refused to take the oath of allegiance to William and...

, and the pioneering of literary criticism

Literary criticism

Literary criticism is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often informed by literary theory, which is the philosophical discussion of its methods and goals...

from John Dryden

John Dryden

John Dryden was an influential English poet, literary critic, translator, and playwright who dominated the literary life of Restoration England to such a point that the period came to be known in literary circles as the Age of Dryden.Walter Scott called him "Glorious John." He was made Poet...

and John Dennis. The period witnessed news become a commodity, the essay

Essay

An essay is a piece of writing which is often written from an author's personal point of view. Essays can consist of a number of elements, including: literary criticism, political manifestos, learned arguments, observations of daily life, recollections, and reflections of the author. The definition...

develop into a periodical art form, and the beginnings of textual criticism

Textual criticism

Textual criticism is a branch of literary criticism that is concerned with the identification and removal of transcription errors in the texts of manuscripts...

.

The dates for Restoration literature are a matter of convention, and they differ markedly from genre

Literary genre

A literary genre is a category of literary composition. Genres may be determined by literary technique, tone, content, or even length. Genre should not be confused with age category, by which literature may be classified as either adult, young-adult, or children's. They also must not be confused...

to genre. Thus, the "Restoration" in drama

English drama

Drama was introduced to England from Europe by the Romans, and auditoriums were constructed across the country for this purpose. By the medieval period, the mummers' plays had developed, a form of early street theatre associated with the Morris dance, concentrating on themes such as Saint George...

may last until 1700, while in poetry

English poetry

The history of English poetry stretches from the middle of the 7th century to the present day. Over this period, English poets have written some of the most enduring poems in Western culture, and the language and its poetry have spread around the globe. Consequently, the term English poetry is...

it may last only until 1666 (see 1666 in poetry

1666 in poetry

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature .-Events:* In Denmark, Anders Bording begins publishing Den Danske Meercurius , a monthly newspaper in rhyme, using alexandrine verse, single-handedly published by the author from this year to 1677-Works...

) and the annus mirabilis

Annus mirabilis

Annus mirabilis is a Latin phrase meaning "wonderful year" or "year of wonders" . It was used originally to refer to the year 1666, but is today also used to refer to different years with events of major importance...

; and in prose it might end in 1688, with the increasing tensions over succession and the corresponding rise in journalism

Journalism

Journalism is the practice of investigation and reporting of events, issues and trends to a broad audience in a timely fashion. Though there are many variations of journalism, the ideal is to inform the intended audience. Along with covering organizations and institutions such as government and...

and periodicals

Magazine

Magazines, periodicals, glossies or serials are publications, generally published on a regular schedule, containing a variety of articles. They are generally financed by advertising, by a purchase price, by pre-paid magazine subscriptions, or all three...

, or not until 1700, when those periodicals grew more stabilized. In general, scholars use the term "Restoration" to denote the literature that began and flourished under Charles II, whether that literature was the laudatory ode

Ode

Ode is a type of lyrical verse. A classic ode is structured in three major parts: the strophe, the antistrophe, and the epode. Different forms such as the homostrophic ode and the irregular ode also exist...

that gained a new life with restored aristocracy, the eschatological

Eschatology

Eschatology is a part of theology, philosophy, and futurology concerned with what are believed to be the final events in history, or the ultimate destiny of humanity, commonly referred to as the end of the world or the World to Come...

literature that showed an increasing despair among Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

s, or the literature of rapid communication and trade that followed in the wake of England's mercantile empire.

Historical context

During the InterregnumEnglish Interregnum

The English Interregnum was the period of parliamentary and military rule by the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell under the Commonwealth of England after the English Civil War...

, England had been dominated by Puritan

Puritan

The Puritans were a significant grouping of English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries. Puritanism in this sense was founded by some Marian exiles from the clergy shortly after the accession of Elizabeth I of England in 1558, as an activist movement within the Church of England...

literature and the intermittent presence of official censorship

Censorship

thumb|[[Book burning]] following the [[1973 Chilean coup d'état|1973 coup]] that installed the [[Military government of Chile |Pinochet regime]] in Chile...

(for example, Milton

John Milton

John Milton was an English poet, polemicist, a scholarly man of letters, and a civil servant for the Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell...

's Areopagitica

Areopagitica

Areopagitica: A speech of Mr. John Milton for the liberty of unlicensed printing to the Parliament of England is a 1644 prose polemical tract by English author John Milton against censorship...

and his later retraction of that statement). While some of the Puritan ministers of Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell was an English military and political leader who overthrew the English monarchy and temporarily turned England into a republican Commonwealth, and served as Lord Protector of England, Scotland, and Ireland....

wrote poetry that was elaborate and carnal (such as Andrew Marvell

Andrew Marvell

Andrew Marvell was an English metaphysical poet, Parliamentarian, and the son of a Church of England clergyman . As a metaphysical poet, he is associated with John Donne and George Herbert...

's poem, "To His Coy Mistress

To His Coy Mistress

To His Coy Mistress is a metaphysical poem written by the British author and statesman Andrew Marvell either during or just before the Interregnum....

"), such poetry was not published. Similarly, some of the poets who published with the Restoration produced their poetry during the Interregnum. The official break in literary culture caused by censorship and radically moralist

Morality

Morality is the differentiation among intentions, decisions, and actions between those that are good and bad . A moral code is a system of morality and a moral is any one practice or teaching within a moral code...

standards effectively created a gap in literary tradition. At the time of the Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations between Parliamentarians and Royalists...

, poetry had been dominated by metaphysical poetry

Metaphysical poets

The metaphysical poets is a term coined by the poet and critic Samuel Johnson to describe a loose group of British lyric poets of the 17th century, who shared an interest in metaphysical concerns and a common way of investigating them, and whose work was characterized by inventiveness of metaphor...

of the John Donne

John Donne

John Donne 31 March 1631), English poet, satirist, lawyer, and priest, is now considered the preeminent representative of the metaphysical poets. His works are notable for their strong and sensual style and include sonnets, love poetry, religious poems, Latin translations, epigrams, elegies, songs,...

, George Herbert

George Herbert

George Herbert was a Welsh born English poet, orator and Anglican priest.Being born into an artistic and wealthy family, he received a good education that led to his holding prominent positions at Cambridge University and Parliament. As a student at Trinity College, Cambridge, Herbert excelled in...

, and Richard Lovelace

Richard Lovelace

Richard Lovelace was an English poet in the seventeenth century. He was a cavalier poet who fought on behalf of the king during the Civil war. His best known works are To Althea, from Prison, and To Lucasta, Going to the Warres....

sort. Drama had developed the late Elizabethan theatre

English Renaissance theatre

English Renaissance theatre, also known as early modern English theatre, refers to the theatre of England, largely based in London, which occurred between the Reformation and the closure of the theatres in 1642...

traditions and had begun to mount increasingly topical and political plays (for example, the drama of Thomas Middleton

Thomas Middleton

Thomas Middleton was an English Jacobean playwright and poet. Middleton stands with John Fletcher and Ben Jonson as among the most successful and prolific of playwrights who wrote their best plays during the Jacobean period. He was one of the few Renaissance dramatists to achieve equal success in...

). The Interregnum put a stop, or at least a caesura

Caesura

thumb|100px|An example of a caesura in modern western music notation.In meter, a caesura is a complete pause in a line of poetry or in a musical composition. The plural form of caesura is caesuras or caesurae...

, to these lines of influence and allowed a seemingly fresh start for all forms of literature after the Restoration.

The last years of the Interregnum were turbulent, as were the last years of the Restoration period, and those who did not go into exile were called upon to change their religious beliefs more than once. With each religious preference came a different sort of literature, both in prose and poetry (the theatres were closed during the Interregnum). When Cromwell died and his son, Richard Cromwell

Richard Cromwell

At the same time, the officers of the New Model Army became increasingly wary about the government's commitment to the military cause. The fact that Richard Cromwell lacked military credentials grated with men who had fought on the battlefields of the English Civil War to secure their nation's...

, threatened to become Lord Protector

Lord Protector

Lord Protector is a title used in British constitutional law for certain heads of state at different periods of history. It is also a particular title for the British Heads of State in respect to the established church...

, politicians and public figures scrambled to show themselves as allies or enemies of the new regime. Printed literature was dominated by ode

Ode

Ode is a type of lyrical verse. A classic ode is structured in three major parts: the strophe, the antistrophe, and the epode. Different forms such as the homostrophic ode and the irregular ode also exist...

s in poetry, and religious writing in prose. The industry of religious tract writing, despite official efforts, did not reduce its output. Figures such as the founder of the Society of Friends

Religious Society of Friends

The Religious Society of Friends, or Friends Church, is a Christian movement which stresses the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers. Members are known as Friends, or popularly as Quakers. It is made of independent organisations, which have split from one another due to doctrinal differences...

, George Fox

George Fox

George Fox was an English Dissenter and a founder of the Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as the Quakers or Friends.The son of a Leicestershire weaver, Fox lived in a time of great social upheaval and war...

, were jailed by the Cromwellian authorities and published at their own peril.

During the Interregnum, the royalist forces attached to the court of Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

went into exile with the twenty-year-old Charles II

Charles II of England

Charles II was monarch of the three kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland.Charles II's father, King Charles I, was executed at Whitehall on 30 January 1649, at the climax of the English Civil War...

and conducted a brisk business in intelligence and fund-raising for an eventual return to England. Some of the royalist ladies

Lady

The word lady is a polite term for a woman, specifically the female equivalent to, or spouse of, a lord or gentleman, and in many contexts a term for any adult woman...

installed themselves in convent

Convent

A convent is either a community of priests, religious brothers, religious sisters, or nuns, or the building used by the community, particularly in the Roman Catholic Church and in the Anglican Communion...

s in Holland and France that offered safe haven for indigent and travelling nobles and allies. The men similarly stationed themselves in Holland and France, with the court-in-exile being established in The Hague

The Hague

The Hague is the capital city of the province of South Holland in the Netherlands. With a population of 500,000 inhabitants , it is the third largest city of the Netherlands, after Amsterdam and Rotterdam...

before setting up more permanently in Paris

Paris

Paris is the capital and largest city in France, situated on the river Seine, in northern France, at the heart of the Île-de-France region...

. The nobility who travelled with (and later travelled to) Charles II were therefore lodged for more than a decade in the midst of the continent's literary scene. As Holland and France in the 17th century were little alike, so the influences picked up by courtiers in exile and the travellers who sent intelligence and money to them were not monolithic. Charles spent his time attending plays in France, and he developed a taste for Spanish plays. Those nobles living in Holland began to learn about mercantile exchange as well as the tolerant, rationalist

Rationalism

In epistemology and in its modern sense, rationalism is "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification" . In more technical terms, it is a method or a theory "in which the criterion of the truth is not sensory but intellectual and deductive"...

prose debates that circulated in that officially tolerant nation. John Bramhall

John Bramhall

John Bramhall was an Archbishop of Armagh, and an Anglican theologian and apologist. He was a noted controversialist who doggedly defended the English Church from both Puritan and Roman Catholic accusations, as well as the materialism of Thomas Hobbes.-Early life:Bramhall was born in Pontefract,...

, for example, had been a strongly high church

High church

The term "High Church" refers to beliefs and practices of ecclesiology, liturgy and theology, generally with an emphasis on formality, and resistance to "modernization." Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term has traditionally been principally associated with the...

theologian

Christian theology

- Divisions of Christian theology :There are many methods of categorizing different approaches to Christian theology. For a historical analysis, see the main article on the History of Christian theology.- Sub-disciplines :...

, and yet, in exile, he debated willingly with Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury , in some older texts Thomas Hobbs of Malmsbury, was an English philosopher, best known today for his work on political philosophy...

and came into the Restored church as tolerant in practice as he was severe in argument. Courtiers also received an exposure to the Roman Catholic Church

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the world's largest Christian church, with over a billion members. Led by the Pope, it defines its mission as spreading the gospel of Jesus Christ, administering the sacraments and exercising charity...

and its liturgy and pageants, as well as, to a lesser extent, Italian poetry

Italian poetry

-Important Italian poets:* Giacomo da Lentini a 13th Century poet who is believed to have invented the sonnet.* Guido Cavalcanti Tuscan poet, and a key figure in the Dolce Stil Novo movement....

.

Initial reaction

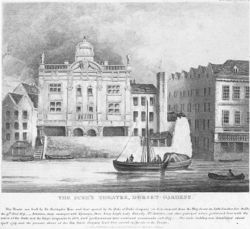

Letters patent

Letters patent are a type of legal instrument in the form of a published written order issued by a monarch or president, generally granting an office, right, monopoly, title, or status to a person or corporation...

giving mandates for the theatre owners and managers. Thomas Killigrew

Thomas Killigrew

Thomas Killigrew was an English dramatist and theatre manager. He was a witty, dissolute figure at the court of King Charles II of England.-Life and work:...

received one of the patents, establishing the King's Company

King's Company

The King's Company was one of two enterprises granted the rights to mount theatrical productions in London at the start of the English Restoration. It existed from 1660 to 1682.-History:...

and opening the first patent theatre

Patent theatre

The patent theatres were the theatres that were licensed to perform "spoken drama" after the English Restoration of Charles II in 1660. Other theatres were prohibited from performing such "serious" drama, but were permitted to show comedy, pantomime or melodrama...

at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

Theatre Royal, Drury Lane

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane is a West End theatre in Covent Garden, in the City of Westminster, a borough of London. The building faces Catherine Street and backs onto Drury Lane. The building standing today is the most recent in a line of four theatres at the same location dating back to 1663,...

; Sir William Davenant

William Davenant

Sir William Davenant , also spelled D'Avenant, was an English poet and playwright. Along with Thomas Killigrew, Davenant was one of the rare figures in English Renaissance theatre whose career spanned both the Caroline and Restoration eras and who was active both before and after the English Civil...

received the other, establishing the Duke of York's theatre company and opening his patent theatre in Lincoln's Inn Fields

Lincoln's Inn Fields

Lincoln's Inn Fields is the largest public square in London, UK. It was laid out in the 1630s under the initiative of the speculative builder and contractor William Newton, "the first in a long series of entrepreneurs who took a hand in developing London", as Sir Nikolaus Pevsner observes...

. Drama was public and a matter of royal concern, and therefore both theatres were charged with producing a certain number of old plays, and Davenant was charged with presenting material that would be morally uplifting. Additionally, the position of Poet Laureate

Poet Laureate

A poet laureate is a poet officially appointed by a government and is often expected to compose poems for state occasions and other government events...

was recreated, complete with payment by a barrel of "sack" (Spanish white wine

Spanish wine

Spanish wines are wines produced in the southwestern European country of Spain. Located on the Iberian Peninsula, Spain has over 2.9 million acres planted—making it the most widely planted wine producing nation but it is the third largest producer of wine in the world, the largest...

), and the requirement for birthday odes.

Charles II was a man who prided himself on his wit

Wit

Wit is a form of intellectual humour, and a wit is someone skilled in making witty remarks. Forms of wit include the quip and repartee.-Forms of wit:...

and his worldliness. He was well known as a philanderer as well. Highly witty, playful, and sexually wise poetry thus had court sanction. Charles and his brother James

James II of England

James II & VII was King of England and King of Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII, from 6 February 1685. He was the last Catholic monarch to reign over the Kingdoms of England, Scotland, and Ireland...

, the Duke of York

Duke of York

The Duke of York is a title of nobility in the British peerage. Since the 15th century, it has, when granted, usually been given to the second son of the British monarch. The title has been created a remarkable eleven times, eight as "Duke of York" and three as the double-barreled "Duke of York and...

and future King of England, also sponsored mathematics

Mathematics

Mathematics is the study of quantity, space, structure, and change. Mathematicians seek out patterns and formulate new conjectures. Mathematicians resolve the truth or falsity of conjectures by mathematical proofs, which are arguments sufficient to convince other mathematicians of their validity...

and natural philosophy

Natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or the philosophy of nature , is a term applied to the study of nature and the physical universe that was dominant before the development of modern science...

, and so spirited scepticism and investigation into nature were favoured by the court. Charles II sponsored the Royal Society

Royal Society

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, known simply as the Royal Society, is a learned society for science, and is possibly the oldest such society in existence. Founded in November 1660, it was granted a Royal Charter by King Charles II as the "Royal Society of London"...

, which courtiers were eager to join (for example, the noted diarist Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys FRS, MP, JP, was an English naval administrator and Member of Parliament who is now most famous for the diary he kept for a decade while still a relatively young man...

was a member), just as Royal Society members moved in court. Charles and his court had also learned the lessons of exile. Charles was High Church

High church

The term "High Church" refers to beliefs and practices of ecclesiology, liturgy and theology, generally with an emphasis on formality, and resistance to "modernization." Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term has traditionally been principally associated with the...

(and secretly vowed to convert to Roman Catholicism on his death) and James was crypto-Catholic, but royal policy was generally tolerant of religious and political dissenters. While Charles II did have his own version of the Test Act

Test Act

The Test Acts were a series of English penal laws that served as a religious test for public office and imposed various civil disabilities on Roman Catholics and Nonconformists...

, he was slow to jail or persecute Puritans, preferring merely to keep them from public office (and therefore to try to rob them of their Parliamentary positions). As a consequence, the prose literature of dissent, political theory, and economics

Economics

Economics is the social science that analyzes the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. The term economics comes from the Ancient Greek from + , hence "rules of the house"...

increased in Charles II's reign.

Authors moved in two directions in reaction to Charles's return. On the one hand, there was an attempt at recovering the English literature of the Jacobean period, as if there had been no disruption; but, on the other, there was a powerful sense of novelty, and authors approached Gallic models

French literature

French literature is, generally speaking, literature written in the French language, particularly by citizens of France; it may also refer to literature written by people living in France who speak traditional languages of France other than French. Literature written in French language, by citizens...

of literature and elevated the literature of wit (particularly satire

Satire

Satire is primarily a literary genre or form, although in practice it can also be found in the graphic and performing arts. In satire, vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, ideally with the intent of shaming individuals, and society itself, into improvement...

and parody

Parody

A parody , in current usage, is an imitative work created to mock, comment on, or trivialise an original work, its subject, author, style, or some other target, by means of humorous, satiric or ironic imitation...

). The novelty would show in the literature of sceptical inquiry, and the Gallicism would show in the introduction of Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism is the name given to Western movements in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that draw inspiration from the "classical" art and culture of Ancient Greece or Ancient Rome...

into English writing and criticism.

Top-down history

The Restoration is an unusual historical period, as its literature is bounded by a specific political event: the restoration of the Stuart monarchy. It is unusual in another way, as well, for it is a time when the influence of that king's presence and personality permeated literary society to such an extent that, almost uniquely, literature reflects the court. The adversaries of the restoration, the Puritans and democrats and republicans, similarly respond to the peculiarities of the king and the king's personality. Therefore, a top-down view of the literary history of the Restoration has more validity than that of most literary epochs. "The Restoration" as a critical concept covers the duration of the effect of Charles and Charles's manner. This effect extended beyond his death, in some instances, and not as long as his life, in others.Poetry

The Restoration was an age of poetry. Not only was poetry the most popular form of literature, but it was also the most significant form of literature, as poems affected political events and immediately reflected the times. It was, to its own people, an age dominated only by the king, and not by any single genius. Throughout the period, the lyric, ariel, historical, and epic poem was being developed.The English epic

Even without the introduction of Neo-classical criticism, English poets were aware that they had no national epicEpic poetry

An epic is a lengthy narrative poem, ordinarily concerning a serious subject containing details of heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation. Oral poetry may qualify as an epic, and Albert Lord and Milman Parry have argued that classical epics were fundamentally an oral poetic form...

. Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser was an English poet best known for The Faerie Queene, an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognised as one of the premier craftsmen of Modern English verse in its infancy, and one of the greatest poets in the English...

's Faerie Queene was well known, but England, unlike France with The Song of Roland

The Song of Roland

The Song of Roland is the oldest surviving major work of French literature. It exists in various manuscript versions which testify to its enormous and enduring popularity in the 12th to 14th centuries...

or Spain with the Cantar de Mio Cid

Cantar de Mio Cid

El Cantar de Myo Çid , also known in English as The Lay of the Cid and The Poem of the Cid is the oldest preserved Spanish epic poem...

or, most of all, Italy with the Aeneid

Aeneid

The Aeneid is a Latin epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Trojan who travelled to Italy, where he became the ancestor of the Romans. It is composed of roughly 10,000 lines in dactylic hexameter...

, had no epic poem of national origins. Several poets attempted to supply this void.

William Davenant

Sir William Davenant , also spelled D'Avenant, was an English poet and playwright. Along with Thomas Killigrew, Davenant was one of the rare figures in English Renaissance theatre whose career spanned both the Caroline and Restoration eras and who was active both before and after the English Civil...

was the first Restoration poet to attempt an epic. His unfinished Gondibert was of epic length, and it was admired by Hobbes. However, it also used the ballad

Ballad

A ballad is a form of verse, often a narrative set to music. Ballads were particularly characteristic of British and Irish popular poetry and song from the later medieval period until the 19th century and used extensively across Europe and later the Americas, Australia and North Africa. Many...

form, and other poets, as well as critics, were very quick to condemn this rhyme scheme as unflattering and unheroic (Dryden Epic). The prefaces to Gondibert show the struggle for a formal epic structure, as well as how the early Restoration saw themselves in relation to Classical literature

Classics

Classics is the branch of the Humanities comprising the languages, literature, philosophy, history, art, archaeology and other culture of the ancient Mediterranean world ; especially Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome during Classical Antiquity Classics (sometimes encompassing Classical Studies or...

.

Although today he is studied separately from the Restoration period, John Milton's Paradise Lost

Paradise Lost

Paradise Lost is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton. It was originally published in 1667 in ten books, with a total of over ten thousand individual lines of verse...

was published during that time. Milton no less than Davenant wished to write the English epic, and chose blank verse

Blank verse

Blank verse is poetry written in unrhymed iambic pentameter. It has been described as "probably the most common and influential form that English poetry has taken since the sixteenth century" and Paul Fussell has claimed that "about three-quarters of all English poetry is in blank verse."The first...

as his form. Milton rejected the cause of English exceptionalism: his Paradise Lost seeks to tell the story of all mankind, and his pride is in Christianity

Christianity

Christianity is a monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus as presented in canonical gospels and other New Testament writings...

rather than Englishness.

Significantly, Milton began with an attempt at writing an epic on King Arthur

King Arthur

King Arthur is a legendary British leader of the late 5th and early 6th centuries, who, according to Medieval histories and romances, led the defence of Britain against Saxon invaders in the early 6th century. The details of Arthur's story are mainly composed of folklore and literary invention, and...

, for that was the matter of English national founding. While Milton rejected that subject, in the end, others made the attempt. Richard Blackmore

Richard Blackmore

Sir Richard Blackmore , English poet and physician, is remembered primarily as the object of satire and as an example of a dull poet. He was, however, a respected physician and religious writer....

wrote both a Prince Arthur and King Arthur. Both attempts were long, soporific, and failed both critically and popularly. Indeed, the poetry was so slow that the author became known as "Never-ending Blackmore" (see Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope was an 18th-century English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer. He is the third-most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, after Shakespeare and Tennyson...

's lambasting of Blackmore in The Dunciad

The Dunciad

The Dunciad is a landmark literary satire by Alexander Pope published in three different versions at different times. The first version was published in 1728 anonymously. The second version, the Dunciad Variorum was published anonymously in 1729. The New Dunciad, in four books and with a...

).

The Restoration period ended without an English epic. Beowulf

Beowulf

Beowulf , but modern scholars agree in naming it after the hero whose life is its subject." of an Old English heroic epic poem consisting of 3182 alliterative long lines, set in Scandinavia, commonly cited as one of the most important works of Anglo-Saxon literature.It survives in a single...

may now be called the English epic, but the work was unknown to Restoration authors, and Old English

Old English language

Old English or Anglo-Saxon is an early form of the English language that was spoken and written by the Anglo-Saxons and their descendants in parts of what are now England and southeastern Scotland between at least the mid-5th century and the mid-12th century...

was incomprehensible to them.

Poetry, verse, and odes

Lyric poetryLyric poetry

Lyric poetry is a genre of poetry that expresses personal and emotional feelings. In the ancient world, lyric poems were those which were sung to the lyre. Lyric poems do not have to rhyme, and today do not need to be set to music or a beat...

, in which the poet speaks of his or her own feelings in the first person

Grammatical person

Grammatical person, in linguistics, is deictic reference to a participant in an event; such as the speaker, the addressee, or others. Grammatical person typically defines a language's set of personal pronouns...

and expresses a mood, was not especially common in the Restoration period. Poets expressed their points of view in other forms, usually public or formally disguised poetic forms such as odes, pastoral poetry, and ariel verse. One of the characteristics of the period is its devaluation of individual sentiment and psychology in favour of public utterance and philosophy

Philosophy

Philosophy is the study of general and fundamental problems, such as those connected with existence, knowledge, values, reason, mind, and language. Philosophy is distinguished from other ways of addressing such problems by its critical, generally systematic approach and its reliance on rational...

. The sorts of lyric poetry found later in the Churchyard Poets would, in the Restoration, only exist as pastorals.

Formally, the Restoration period had a preferred rhyme scheme. Rhyming

Rhyme

A rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds in two or more words and is most often used in poetry and songs. The word "rhyme" may also refer to a short poem, such as a rhyming couplet or other brief rhyming poem such as nursery rhymes.-Etymology:...

couplet

Couplet

A couplet is a pair of lines of meter in poetry. It usually consists of two lines that rhyme and have the same meter.While traditionally couplets rhyme, not all do. A poem may use white space to mark out couplets if they do not rhyme. Couplets with a meter of iambic pentameter are called heroic...

s in iambic pentameter

Iambic pentameter

Iambic pentameter is a commonly used metrical line in traditional verse and verse drama. The term describes the particular rhythm that the words establish in that line. That rhythm is measured in small groups of syllables; these small groups of syllables are called "feet"...

was by far the most popular structure for poetry of all types. Neo-Classicism meant that poets attempted adaptations of Classical meter

Latin poetry

The history of Latin poetry can be understood as the adaptation of Greek models. The verse comedies of Plautus are the earliest Latin literature that has survived, composed around 205-184 BC, yet the start of Latin literature is conventionally dated to the first performance of a play in verse by a...

s, but the rhyming couplet in iambic pentameter held a near monopoly. According to Dryden ("Preface to The Conquest of Grenada"), the rhyming couplet in iambic pentameter has the right restraint and dignity for a lofty subject, and its rhyme allowed for a complete, coherent statement to be made. Dryden was struggling with the issue of what later critics in the Augustan period

Augustan literature

Augustan literature is a style of English literature produced during the reigns of Queen Anne, King George I, and George II on the 1740s with the deaths of Pope and Swift...

would call "decorum": the fitness of form to subject (q.v. Dryden Epic). It is the same struggle that Davenant faced in his Gondibert. Dryden's solution was a closed couplet

Closed couplet

In poetics, closed couplets are two line units of verse that do not extend their sense beyond the line's end. Furthermore, the lines are usually rhymed. When the lines are in iambic pentameter, they are referred to as heroic verse. However, Samuel Butler also used closed couplets in his iambic...

in iambic pentameter that would have a minimum of enjambment

Enjambment

Enjambment or enjambement is the breaking of a syntactic unit by the end of a line or between two verses. It is to be contrasted with end-stopping, where each linguistic unit corresponds with a single line, and caesura, in which the linguistic unit ends mid-line...

. This form was called the "heroic couplet," because it was suitable for heroic subjects. Additionally, the age also developed the mock-heroic couplet. After 1672 and Samuel Butler's Hudibras

Hudibras

Hudibras is an English mock heroic narrative poem from the 17th century written by Samuel Butler.-Purpose:The work is a satirical polemic upon Roundheads, Puritans, Presbyterians and many of the other factions involved in the English Civil War...

, iambic tetrameter couplets with unusual or unexpected rhymes became known as Hudibrastic verse

Hudibrastic

Hudibrastic is a type of English verse named for Samuel Butler's Hudibras, published in parts from 1663 to 1678. For the poem, Butler invented a mock-heroic verse structure. Instead of pentameter, the lines were written in iambic tetrameter...

. It was a formal parody

Parody

A parody , in current usage, is an imitative work created to mock, comment on, or trivialise an original work, its subject, author, style, or some other target, by means of humorous, satiric or ironic imitation...

of heroic verse, and it was primarily used for satire. Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift was an Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer , poet and cleric who became Dean of St...

would use the Hudibrastic form almost exclusively for his poetry.

Although Dryden's reputation is greater today, contemporaries saw the 1670s and 1680s as the age of courtier poets in general, and Edmund Waller

Edmund Waller

Edmund Waller, FRS was an English poet and politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1624 and 1679.- Early life :...

was as praised as any. Dryden, Rochester

John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester

John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester , styled Viscount Wilmot between 1652 and 1658, was an English Libertine poet, a friend of King Charles II, and the writer of much satirical and bawdy poetry. He was the toast of the Restoration court and a patron of the arts...

, Buckingham

George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, 20th Baron de Ros of Helmsley, KG, PC, FRS was an English statesman and poet.- Upbringing and education :...

, and Dorset

Charles Sackville, 6th Earl of Dorset

Charles Sackville, 6th Earl of Dorset and 1st Earl of Middlesex was an English poet and courtier.-Early Life:He was son of Richard Sackville, 5th Earl of Dorset...

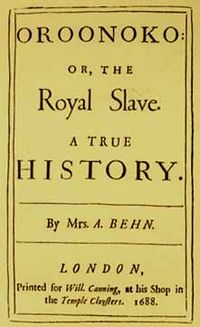

dominated verse, and all were attached to the court of Charles. Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn

Aphra Behn was a prolific dramatist of the English Restoration and was one of the first English professional female writers. Her writing contributed to the amatory fiction genre of British literature.-Early life:...

, Matthew Prior

Matthew Prior

Matthew Prior was an English poet and diplomat.Prior was the son of a Nonconformist joiner at Wimborne Minster, East Dorset. His father moved to London, and sent him to Westminster School, under Dr. Busby. On his father's death, he left school, and was cared for by his uncle, a vintner in Channel...

, and Robert Gould

Robert Gould

Robert Gould was a significant voice in Restoration poetry in England.He was born in the lower classes and orphaned when he was thirteen. It is possible that he had a sister, but her name and fate are unknown. Gould entered into domestic service...

, by contrast, were outsiders who were profoundly royalist. The court poets follow no one particular style, except that they all show sexual awareness, a willingness to satirise, and a dependence upon wit to dominate their opponents. Each of these poets wrote for the stage as well as the page. Of these, Behn, Dryden, Rochester, and Gould deserve some separate mention.

Walter Raleigh

Sir Walter Raleigh was an English aristocrat, writer, poet, soldier, courtier, spy, and explorer. He is also well known for popularising tobacco in England....

and Philip Sidney

Philip Sidney

Sir Philip Sidney was an English poet, courtier and soldier, and is remembered as one of the most prominent figures of the Elizabethan Age...

, but his greatest successes and fame came from his attempts at apologetics

Apologetics

Apologetics is the discipline of defending a position through the systematic use of reason. Early Christian writers Apologetics (from Greek ἀπολογία, "speaking in defense") is the discipline of defending a position (often religious) through the systematic use of reason. Early Christian writers...

for the restored court and the Established Church. His Absalom and Achitophel

Absalom and Achitophel

Absalom and Achitophel is a landmark poetic political satire by John Dryden. The poem exists in two parts. The first part, of 1681, is undoubtedly by Dryden...

and Religio Laici both served the King directly by making controversial royal actions seem reasonable. He also pioneered the mock-heroic

Mock-heroic

Mock-heroic, mock-epic or heroi-comic works are typically satires or parodies that mock common Classical stereotypes of heroes and heroic literature...

. Although Samuel Butler had invented the mock-heroic in English with Hudibras (written during the Interregnum but published in the Restoration), Dryden's MacFlecknoe

MacFlecknoe

Mac Flecknoe is a verse mock-heroic satire written by John Dryden. It is a direct attack on Thomas Shadwell, another prominent poet of the time...

set up the satirical parody. Dryden was himself not of noble blood, and he was never awarded the honours that he had been promised by the King (nor was he repaid the loans he had made to the King), but he did as much as any peer to serve Charles II. Even when James II came to the throne and Roman Catholicism was on the rise, Dryden attempted to serve the court, and his The Hind and the Panther

The Hind and the Panther

The Hind and the Panther: A Poem, in Three Parts is an allegory in heroic couplets by John Dryden. At some 2600 lines it is much the longest of Dryden's poems, translations excepted, and perhaps the most controversial...

praised the Roman church above all others. After that point, Dryden suffered for his conversions, and he was the victim of many satires.

St. James's Park

St. James's Park is a 23 hectare park in the City of Westminster, central London - the oldest of the Royal Parks of London. The park lies at the southernmost tip of the St. James's area, which was named after a leper hospital dedicated to St. James the Less.- Geographical location :St. James's...

", which is about the dangers of darkness for a man intent on copulation and the historical compulsion of that plot of ground as a place for fornication), several mock odes ("To Signore Dildo," concerning the public burning of a crate of "contraband" from France on the London

London

London is the capital city of :England and the :United Kingdom, the largest metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, and the largest urban zone in the European Union by most measures. Located on the River Thames, London has been a major settlement for two millennia, its history going back to its...

docks), and mock pastorals. Rochester's interest was in inversion, disruption, and the superiority of wit as much as it was in hedonism

Hedonism

Hedonism is a school of thought which argues that pleasure is the only intrinsic good. In very simple terms, a hedonist strives to maximize net pleasure .-Etymology:The name derives from the Greek word for "delight" ....

. Rochester's venality led to an early death, and he was later frequently invoked as the exemplar of a Restoration rake

Rake (character)

A rake, short for rakehell, is a historic term applied to a man who is habituated to immoral conduct, frequently a heartless womanizer. Often a rake was a man who wasted his fortune on gambling, wine, women and song, incurring lavish debts in the process...

.

Kent

Kent is a county in southeast England, and is one of the home counties. It borders East Sussex, Surrey and Greater London and has a defined boundary with Essex in the middle of the Thames Estuary. The ceremonial county boundaries of Kent include the shire county of Kent and the unitary borough of...

ish, she is remarkable for her success in moving in the same circles as the King himself. As Janet Todd

Janet Todd

Janet Margaret Todd is a Welsh-born academic and a well-respected author of many books on women in literature. Todd was educated at Cambridge University and the University of Florida, where she undertook a doctorate on the poet John Clare...

and others have shown, she was likely a spy for the Royalist side during the Interregnum. She was certainly a spy for Charles II in the Second Anglo-Dutch War

Second Anglo-Dutch War

The Second Anglo–Dutch War was part of a series of four Anglo–Dutch Wars fought between the English and the Dutch in the 17th and 18th centuries for control over the seas and trade routes....

, but found her services unrewarded (in fact, she may have spent time in debtor's prison

Debtor's prison

A debtors' prison is a prison for those who are unable to pay a debt.Prior to the mid 19th century debtors' prisons were a common way to deal with unpaid debt.-Debt bondage in ancient Greece and Rome:...

) and turned to writing to support herself. Her ability to write poetry that stands among the best of the age gives some lie to the notion that the Restoration was an age of female illiteracy and verse composed and read only by peers.

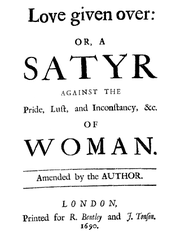

Robert Gould

Robert Gould was a significant voice in Restoration poetry in England.He was born in the lower classes and orphaned when he was thirteen. It is possible that he had a sister, but her name and fate are unknown. Gould entered into domestic service...

breaks that rule altogether. Gould was born of a common family and orphan

Orphan

An orphan is a child permanently bereaved of or abandoned by his or her parents. In common usage, only a child who has lost both parents is called an orphan...

ed at the age of thirteen. He had no schooling at all and worked as a domestic servant, first as a footman

Footman

A footman is a male servant, notably as domestic staff.-Word history:The name derives from the attendants who ran beside or behind the carriages of aristocrats, many of whom were chosen for their physical attributes. They ran alongside the coach to make sure it was not overturned by such obstacles...

and then, probably, in the pantry

Pantry

A pantry is a room where food, provisions or dishes are stored and served in an ancillary capacity to the kitchen. The derivation of the word is from the same source as the Old French term paneterie; that is from pain, the French form of the Latin panis for bread.In a late medieval hall, there were...

. However, he was attached to the Earl of Dorset's household, and Gould somehow learned to read and write, as well as possibly to read and write Latin

Latin

Latin is an Italic language originally spoken in Latium and Ancient Rome. It, along with most European languages, is a descendant of the ancient Proto-Indo-European language. Although it is considered a dead language, a number of scholars and members of the Christian clergy speak it fluently, and...

. In the 1680s and 1690s, Gould's poetry was very popular. He attempted to write odes for money, but his great success came with Love Given O'er, or A Satyr Upon ... Woman in 1692. It was a partial adaptation of a satire by Juvenal, but with an immense amount of explicit invective against women. The misogyny

Misogyny

Misogyny is the hatred or dislike of women or girls. Philogyny, meaning fondness, love or admiration towards women, is the antonym of misogyny. The term misandry is the term for men that is parallel to misogyny...

in this poem is some of the harshest and most visceral in English poetry: the poem sold out all editions. Gould also wrote a Satyr on the Play House (reprinted in Montagu Sommers's The London Stage) with detailed descriptions of the actions and actors involved in the Restoration stage. He followed the success of Love Given O'er with a series of misogynistic poems, all of which have specific, graphic, and witty denunciations of female behaviour. His poetry has "virgin" brides who, upon their wedding nights, have "the straight gate so wide/ It's been leapt by all mankind," noblewomen who have money but prefer to pay the coachman with oral sex

Oral sex

Oral sex is sexual activity involving the stimulation of the genitalia of a sex partner by the use of the mouth, tongue, teeth or throat. Cunnilingus refers to oral sex performed on females while fellatio refer to oral sex performed on males. Anilingus refers to oral stimulation of a person's anus...

, and noblewomen having sex in their coaches and having the cobblestone

Cobblestone

Cobblestones are stones that were frequently used in the pavement of early streets. "Cobblestone" is derived from the very old English word "cob", which had a wide range of meanings, one of which was "rounded lump" with overtones of large size...

s heighten their pleasures. Gould's career was brief, but his success was not a novelty of subliterary misogyny. After Dryden's conversion to Roman Catholicism, Gould even engaged in a poison pen

Poison Pen

Poison Pen is the third studio album by Chino XL, an American hip hop musician. Fans anticipated this release ever since Chino XL's Poison Pen: The Lost Tapes, which featured the tracks "Beastin'", "Our Time", and "Wordsmith". Poison Pen was released as a 2-disc special collector's edition. Every...

battle with the Laureate. His "Jack Squab" (the Laureate getting paid with squab as well as sack and implying that Dryden would sell his soul for a dinner) attacked Dryden's faithlessness viciously, and Dryden and his friends replied. That a footman even could conduct a verse war is remarkable. That he did so without, apparently, any prompting from his patron is astonishing.

Translations and controversialists

Roger L'EstrangeRoger L'Estrange

Sir Roger L'Estrange was an English pamphleteer and author, and staunch defender of royalist claims. L'Estrange was involved in political controversy throughout his life...

(per above) was a significant translator, and he also produced verse translations. Others, such as Richard Blackmore

Richard Blackmore

Sir Richard Blackmore , English poet and physician, is remembered primarily as the object of satire and as an example of a dull poet. He was, however, a respected physician and religious writer....

, were admired for their "sentence" (declamation and sentiment) but have not been remembered. Also, Elkannah Settle was, in the Restoration, a lively and promising political satirist, though his reputation has not fared well since his day. After booksellers began hiring authors and sponsoring specific translations, the shops filled quickly with poetry from hirelings. Similarly, as periodical literature began to assert itself as a political force, a number of now anonymous poets produced topical, specifically occasional verse.

The largest and most important form of incunabula of the era was satire. There were great dangers in being associated with satire and its publication was generally done anonymously. To begin with, defamation

Slander and libel

Defamation—also called calumny, vilification, traducement, slander , and libel —is the communication of a statement that makes a claim, expressly stated or implied to be factual, that may give an individual, business, product, group, government, or nation a negative image...

law cast a wide net, and it was difficult for a satirist to avoid prosecution if he were proven to have written a piece that seemed to criticise a noble. More dangerously, wealthy individuals would often respond to satire by having the suspected poet physically attacked by ruffians. The Earl of Rochester hired such thugs to attack John Dryden suspected of having writtenAn Essay on Satire. A consequence of this anonymity is that a great many poems, some of them of merit, are unpublished and largely unknown. Political satires against The Cabal

Cabal

A cabal is a group of people united in some close design together, usually to promote their private views and/or interests in a church, state, or other community, often by intrigue...

, against Sunderland's government, and, most especially, against James II's rumoured conversion to Roman Catholicism, are uncollected. However, such poetry was a vital part of the vigorous Restoration scene, and it was an age of energetic and voluminous satire.

Prose genres

Prose in the Restoration period is dominated by Christian religious writingChristian literature

Christian Literature is writing that deals with Christian themes and incorporates the Christian world view. This constitutes a huge body of extremely varied writing.-Scripture:...

, but the Restoration also saw the beginnings of two genres that would dominate later periods: fiction

Fiction

Fiction is the form of any narrative or informative work that deals, in part or in whole, with information or events that are not factual, but rather, imaginary—that is, invented by the author. Although fiction describes a major branch of literary work, it may also refer to theatrical,...

and journalism. Religious writing often strayed into political and economic writing, just as political and economic writing implied or directly addressed religion.

Philosophical writing

The Restoration saw the publication of a number of significant pieces of political and philosophical writing that had been spurred by the actions of the Interregnum. Additionally, the court's adoption of Neo-classicism and empiricalEmpiricism

Empiricism is a theory of knowledge that asserts that knowledge comes only or primarily via sensory experience. One of several views of epistemology, the study of human knowledge, along with rationalism, idealism and historicism, empiricism emphasizes the role of experience and evidence,...

science led to a receptiveness toward significant philosophical works.

Thomas Sprat

Thomas Sprat , English divine, was born at Beaminster, Dorset, and educated at Wadham College, Oxford, where he held a fellowship from 1657 to 1670.Having taken orders he became a prebendary of Lincoln Cathedral in 1660...

wrote his History of the Royal Society in 1667 and set forth, in a single document, the goals of empirical science ever after. He expressed grave suspicions of adjective

Adjective

In grammar, an adjective is a 'describing' word; the main syntactic role of which is to qualify a noun or noun phrase, giving more information about the object signified....

s, nebulous terminology, and all language that might be subjective. He praised a spare, clean, and precise vocabulary for science and explanations that are as comprehensible as possible. In Sprat's account, the Royal Society explicitly rejected anything that seemed like scholasticism

Scholasticism

Scholasticism is a method of critical thought which dominated teaching by the academics of medieval universities in Europe from about 1100–1500, and a program of employing that method in articulating and defending orthodoxy in an increasingly pluralistic context...

. For Sprat, as for a number of the founders of the Royal Society, science was Protestant

Protestantism

Protestantism is one of the three major groupings within Christianity. It is a movement that began in Germany in the early 16th century as a reaction against medieval Roman Catholic doctrines and practices, especially in regards to salvation, justification, and ecclesiology.The doctrines of the...

: its reasons and explanations had to be comprehensible to all. There would be no priest

Priest

A priest is a person authorized to perform the sacred rites of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particular, rites of sacrifice to, and propitiation of, a deity or deities...

s in science, and anyone could reproduce the experiments and hear their lessons. Similarly, he emphasised the need for conciseness in description, as well as reproducibility of experiments.

Secretary of State (United Kingdom)

In the United Kingdom, a Secretary of State is a Cabinet Minister in charge of a Government Department ....

, wrote several bucolic prose works in praise of retirement, contemplation, and direct observation of nature. He also brought the Ancients and Moderns quarrel into English with his Reflections on Ancient and Modern Learning. The debates that followed in the wake of this quarrel would inspire many of the major authors of the first half of the 18th century (most notably Swift and Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope was an 18th-century English poet, best known for his satirical verse and for his translation of Homer. He is the third-most frequently quoted writer in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations, after Shakespeare and Tennyson...

).

The Restoration was also the time when John Locke

John Locke

John Locke FRS , widely known as the Father of Liberalism, was an English philosopher and physician regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers. Considered one of the first of the British empiricists, following the tradition of Francis Bacon, he is equally important to social...

wrote many of his philosophical works. Locke's empiricism was an attempt at understanding the basis of human understanding itself and thereby devising a proper manner for making sound decisions. These same scientific methods led Locke to his Two Treatises of Government

Two Treatises of Government

The Two Treatises of Government is a work of political philosophy published anonymously in 1689 by John Locke...

, which later inspired the thinkers in the American Revolution

American Revolution

The American Revolution was the political upheaval during the last half of the 18th century in which thirteen colonies in North America joined together to break free from the British Empire, combining to become the United States of America...

. As with his work on understanding, Locke moves from the most basic units of society toward the more elaborate, and, like Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury , in some older texts Thomas Hobbs of Malmsbury, was an English philosopher, best known today for his work on political philosophy...

, he emphasises the plastic nature of the social contract

Social contract

The social contract is an intellectual device intended to explain the appropriate relationship between individuals and their governments. Social contract arguments assert that individuals unite into political societies by a process of mutual consent, agreeing to abide by common rules and accept...

. For an age that had seen absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy

Absolute monarchy is a monarchical form of government in which the monarch exercises ultimate governing authority as head of state and head of government, his or her power not being limited by a constitution or by the law. An absolute monarch thus wields unrestricted political power over the...

overthrown, democracy

Democracy

Democracy is generally defined as a form of government in which all adult citizens have an equal say in the decisions that affect their lives. Ideally, this includes equal participation in the proposal, development and passage of legislation into law...

attempted, democracy corrupted, and limited monarchy

Constitutional monarchy

Constitutional monarchy is a form of government in which a monarch acts as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, whether it be a written, uncodified or blended constitution...

restored; only a flexible basis for government could be satisfying.

Religious writing

The Restoration moderated most of the more strident sectarian writing, but radicalism persisted after the Restoration. Puritan authors such as John MiltonJohn Milton

John Milton was an English poet, polemicist, a scholarly man of letters, and a civil servant for the Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell...

were forced to retire from public life or adapt, and those Diggers, Fifth Monarchist, Leveller

Levellers

The Levellers were a political movement during the English Civil Wars which emphasised popular sovereignty, extended suffrage, equality before the law, and religious tolerance, all of which were expressed in the manifesto "Agreement of the People". They came to prominence at the end of the First...

, Quaker

Religious Society of Friends

The Religious Society of Friends, or Friends Church, is a Christian movement which stresses the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers. Members are known as Friends, or popularly as Quakers. It is made of independent organisations, which have split from one another due to doctrinal differences...

, and Anabaptist

Anabaptist

Anabaptists are Protestant Christians of the Radical Reformation of 16th-century Europe, and their direct descendants, particularly the Amish, Brethren, Hutterites, and Mennonites....

authors who had preached against monarchy and who had participated directly in the regicide

Regicide

The broad definition of regicide is the deliberate killing of a monarch, or the person responsible for the killing of a monarch. In a narrower sense, in the British tradition, it refers to the judicial execution of a king after a trial...

of Charles I

Charles I of England

Charles I was King of England, King of Scotland, and King of Ireland from 27 March 1625 until his execution in 1649. Charles engaged in a struggle for power with the Parliament of England, attempting to obtain royal revenue whilst Parliament sought to curb his Royal prerogative which Charles...

were partially suppressed. Consequently, violent writings were forced underground, and many of those who had served in the Interregnum attenuated their positions in the Restoration.

Fox, and William Penn

William Penn

William Penn was an English real estate entrepreneur, philosopher, and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, the English North American colony and the future Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. He was an early champion of democracy and religious freedom, notable for his good relations and successful...

, made public vows of pacifism

Pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition to war and violence. The term "pacifism" was coined by the French peace campaignerÉmile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress inGlasgow in 1901.- Definition :...

and preached a new theology of peace and love. Other Puritans contented themselves with being able to meet freely and act on local parishes. They distanced themselves from the harshest sides of their religion that had led to the abuses of Cromwell's reign. Two religious authors stand out beyond the others in this time: John Bunyan

John Bunyan

John Bunyan was an English Christian writer and preacher, famous for writing The Pilgrim's Progress. Though he was a Reformed Baptist, in the Church of England he is remembered with a Lesser Festival on 30 August, and on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church on 29 August.-Life:In 1628,...

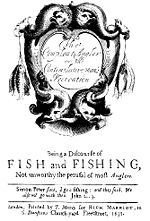

and Izaak Walton

Izaak Walton

Izaak Walton was an English writer. Best known as the author of The Compleat Angler, he also wrote a number of short biographies which have been collected under the title of Walton's Lives.-Biography:...

.

Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress

The Pilgrim's Progress

The Pilgrim's Progress from This World to That Which Is to Come is a Christian allegory written by John Bunyan and published in February, 1678. It is regarded as one of the most significant works of religious English literature, has been translated into more than 200 languages, and has never been...

is an allegory

Allegory

Allegory is a demonstrative form of representation explaining meaning other than the words that are spoken. Allegory communicates its message by means of symbolic figures, actions or symbolic representation...

of personal salvation

Salvation

Within religion salvation is the phenomenon of being saved from the undesirable condition of bondage or suffering experienced by the psyche or soul that has arisen as a result of unskillful or immoral actions generically referred to as sins. Salvation may also be called "deliverance" or...

and a guide to the Christian life. Instead of any focus on eschatology

Eschatology

Eschatology is a part of theology, philosophy, and futurology concerned with what are believed to be the final events in history, or the ultimate destiny of humanity, commonly referred to as the end of the world or the World to Come...

or divine retribution, Bunyan instead writes about how the individual saint

Saint

A saint is a holy person. In various religions, saints are people who are believed to have exceptional holiness.In Christian usage, "saint" refers to any believer who is "in Christ", and in whom Christ dwells, whether in heaven or in earth...

can prevail against the temptations of mind and body that threaten damnation. The book is written in a straightforward narrative and shows influence from both drama and biography

Biography

A biography is a detailed description or account of someone's life. More than a list of basic facts , biography also portrays the subject's experience of those events...

, and yet it also shows an awareness of the allegorical tradition found in Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser

Edmund Spenser was an English poet best known for The Faerie Queene, an epic poem and fantastical allegory celebrating the Tudor dynasty and Elizabeth I. He is recognised as one of the premier craftsmen of Modern English verse in its infancy, and one of the greatest poets in the English...

.

Angling

Angling is a method of fishing by means of an "angle" . The hook is usually attached to a fishing line and the line is often attached to a fishing rod. Fishing rods are usually fitted with a fishing reel that functions as a mechanism for storing, retrieving and paying out the line. The hook itself...

, but readers treasured its contents for their descriptions of nature and serenity. There are few analogues to this prose work. On the surface, it appears to be in the tradition of other guide books (several of which appeared in the Restoration, including Charles Cotton

Charles Cotton

Charles Cotton was an English poet and writer, best known for translating the work of Michel de Montaigne from the French, for his contributions to The Compleat Angler, and for the highly influential The Compleat Gamester which has been attributed to him.-Early life:He was born at Beresford Hall...

's The Compleat Gamester, which is one of the earliest attempts at settling the rules of card game

Card game

A card game is any game using playing cards as the primary device with which the game is played, be they traditional or game-specific. Countless card games exist, including families of related games...

s), but, like Pilgrim's Progress, its main business is guiding the individual.

More court-oriented religious prose included sermon collections and a great literature of debate over the convocation

Convocation

A Convocation is a group of people formally assembled for a special purpose.- University use :....

and issues before the House of Lords

House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster....

. The Act of First Fruits and Fifths, the Test Act

Test Act

The Test Acts were a series of English penal laws that served as a religious test for public office and imposed various civil disabilities on Roman Catholics and Nonconformists...

, the Act of Uniformity 1662

Act of Uniformity 1662

The Act of Uniformity was an Act of the Parliament of England, 13&14 Ch.2 c. 4 ,The '16 Charles II c. 2' nomenclature is reference to the statute book of the numbered year of the reign of the named King in the stated chapter...

, and others engaged the leading divines of the day. Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle FRS was a 17th century natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, and inventor, also noted for his writings in theology. He has been variously described as English, Irish, or Anglo-Irish, his father having come to Ireland from England during the time of the English plantations of...

, notable as a scientist, also wrote his Meditations on God

God

God is the English name given to a singular being in theistic and deistic religions who is either the sole deity in monotheism, or a single deity in polytheism....

, and this work was immensely popular as devotional literature well beyond the Restoration. (Indeed, it is today perhaps most famous for Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift was an Irish satirist, essayist, political pamphleteer , poet and cleric who became Dean of St...

's parody of it in Meditation Upon a Broomstick

Meditation Upon a Broomstick

thumb|right|A Meditation Upon a Broomstick is a satire and parody written by Jonathan Swift in 1701. Edmund Curll, in an attempt to antagonize and siphon off money from Swift, published it in 1710 from a manuscript stolen from Swift , but the satire's origins lie in Swift's time...

.) Devotional literature in general sold well and attests a wide literacy rate among the English middle classes.

Journalism

During the Restoration period, the most common manner of getting news would have been a broadsheetBroadsheet

Broadsheet is the largest of the various newspaper formats and is characterized by long vertical pages . The term derives from types of popular prints usually just of a single sheet, sold on the streets and containing various types of material, from ballads to political satire. The first broadsheet...

publication. A single, large sheet of paper might have a written, usually partisan, account of an event. However, the period saw the beginnings of the first professional and periodical (meaning that the publication was regular) journalism

Journalism

Journalism is the practice of investigation and reporting of events, issues and trends to a broad audience in a timely fashion. Though there are many variations of journalism, the ideal is to inform the intended audience. Along with covering organizations and institutions such as government and...

in England. Journalism develops late, generally around the time of William of Orange

William III of England