LaRouche movement

Encyclopedia

The LaRouche movement is an international political and cultural network that promotes Lyndon LaRouche

and his ideas. It has included scores of organizations and companies around the world. Their activities include campaigning, private intelligence gathering, and publishing numerous periodicals, pamphlets, books, and online content. It characterizes itself as a Platonist Whig movement which favors re-industrialization and classical culture, and which opposes what it sees as the genocidal conspiracies of Aristotelian oligarchies such as the British Empire. Outsiders characterize it as a fringe movement and it has been criticized from across the political spectrum.

The movement had its origins in radical leftist student politics of the 1960s, but is now generally seen as a right-wing, fascist or unclassifiable group. It is known for its unusual theories and its confrontational behavior. In the 1970s members allegedly engaged in street violence. In the 1970s and 1980s hundreds of candidates, some with only limited knowledge of LaRouche or the movement, ran as Democrats

on the LaRouche platform. None were elected to significant public office.

In 1988, LaRouche and 25 associates were convicted on fraud charges related to fund-raising, prosecutions which the movement alleged were politically motivated and which were followed by a decline in the group's influence which lasted for several years. The movement was rejuvenated in the 2000s by the creation of a youth cadre, the LaRouche Youth Movement, and by their prominent opposition to the Bush/Cheney administration and the Obama health care reform plan.

LaRouche's wife, Helga Zepp-LaRouche

, heads political and cultural groups in Germany connected with her husband's movement. There are also parties in France, Sweden, and other European countries, and branches or affiliates in Australia, Canada, the Philippines, and several Latin American countries. Estimates of the movement range from five hundred to one thousand members in the United States, spread across more than a dozen cities, and about the same number abroad. Members engage in political organizing, fund-raising, cultural events, research and writing, and internal meetings. It has been categorized as a political cult by some journalists. According to reporters, members believe they are solely responsible for the protection of civilization and some work long hours for little pay to further their mission. The LaRouche movement has been accused of repeatedly harassing public officials, politicians, journalists, ex-members, and critics. The movement has had a number of notable collaborators and members.

LaRouche-affiliated political parties have nominated many hundreds of candidates for national and regional offices in the U.S.

, Canada

, Sweden

, Denmark

, Germany

, Australia

and France

, for almost thirty years. In countries outside the U.S., the LaRouche movement maintains its own minor parties, and they have had no significant electoral success to date. In the U.S., however, they are active in the Democratic Party, and individuals associated with the movement have successfully sought party office in some elections, particularly Democratic County Central Committee posts.

and the International Caucus of Labor Committees (ICLC) are international organizations that mobilize on behalf of the LaRouche Movement. Schiller Institute conferences have been held across the world. The ICLC is affiliated to political parties in France

, Italy

, Germany

, Poland

, Hungary

, Russia

, Denmark

, Sweden

, Mexico

, the Philippines

, and several South American countries. Lyndon LaRouche, who is based in Loudoun County, Virginia

, United States

, and his wife, Helga Zepp-LaRouche

, based in Wiesbaden

, Germany, regularly attend these international conferences and have met foreign politicians, bureaucrats, and academics.

LaRouche himself has been a candidate for U.S. president eight times, running in every presidential election from 1976 to 2004. The first was with his own party, the U.S. Labor Party

LaRouche himself has been a candidate for U.S. president eight times, running in every presidential election from 1976 to 2004. The first was with his own party, the U.S. Labor Party

. In the next seven campaigns he campaigned for the Democratic Party

nomination. In support of those efforts he has created campaign committees and a PAC

, and has attempted to gain entrance to caucus

es, debates, and conventions

for himself and supporters. He was a successful fundraiser

in 2004 by some measures, and received federal matching funds

. See Lyndon LaRouche U.S. Presidential campaigns

.

In 1986 the LaRouche movement placed its AIDS

initiative, Proposition 64

, on the California

ballot, which lost by a 4-1 margin. It was re-introduced in 1988 and lost again by the same margin. Federal and state officials raided movement offices in 1986. In the ensuing trials, leaders of the movement received prison terms for conspiracy to commit fraud, mail fraud, and tax evasion. See LaRouche criminal trials.

In 1986, LaRouche movement members Janice Hart

and Mark J. Fairchild won the Democratic Primary elections for the offices of Illinois Secretary of State and Illinois Lieutenant Governor

respectively. Up until the day following the election, major media outlets were reporting that George Sangmeister, Fairchild's primary opponent, was running unopposed. 21 years later Fairchild asked, “how is it possible that the major media, with all of their access to information, could possibly be mistaken in that way?” Democratic gubernatorial candidate Adlai Stevenson III

was favored to win this election, having lost the previous election by a narrow margin amid allegations of vote fraud. However, he refused to run on the same slate with Hart and Fairchild. Instead, Stevenson formed the Solidarity Party

and ran with Jane Spirgel as the Secretary of State nominee. Hart and Spirgel's opponent, Republican incumbent Jim Edgar

, won the election by the largest margin in any state-wide election in Illinois history, with 1.574 million votes.

After the Illinois primary Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-NY) blasted his own party for pursuing a policy of ignoring the "infiltration by the neo-Nazi elements of Lyndon H. LaRouche," and worried that too often, especially in the media, "the LaRouchites" are "dismissed as kooks." "In an age of ideology, in an age of totalitarianism, it will not suffice for a political party to be indifferent to and ignorant about such a movement," said Moynihan. Moynihan had previously faced a primary challenge in 1982 from Mel Klenetsky, a Jewish associate of LaRouche, and had called Klenetsky "anti-Semitic."

In 1988, Claude Jones won the chairmanship of the Harris County

Democratic Party in Houston, only to be stripped of his authority by the county executive committee before he could take office. He was removed from office by the state party chairman a few months later, in February 1989, because of Jones's alleged opposition to the Democratic presidential candidate, Michael Dukakis

, in favor of LaRouche.

The LaRouche movement is reported by multiple sources, including journalists Jason Berry

and George Johnson

, to have had close ties to the Iraqi Ba'ath Party of Saddam Hussein

. It was a leading opponent of the UN sanctions

against Iraq in 1991 and the subsequent Gulf War

in 1992. Supporters formed the "Committee to Save the Children in Iraq". LaRouche blamed the sanctions and war on "Israeli-controlled Moslem fundamentalist groups" and the "Ariel Sharon-dominated government of Israel" whose policies were "dictated by Kissinger and company, through the Hollinger Corporation, which has taken over The Jerusalem Post for that purpose." Left-wing anti-war groups were divided over the LaRouche movement's involvement.

In 2000, the Democratic nominee in Wyoming for the Senate, Mel Logan, was a LaRouche follower; the Republican incumbent, Craig Thomas, won in a 76%-23% landslide. In 2001, a "national citizen-candidates' movement" was created, advancing candidates for a number of elective offices across the country.

In 2006, LaRouche Youth Movement activist and Los Angeles County Democratic Central Committee member Cody Jones was honored as "Democrat of the Year" for the 43rd Assembly District of California, by the Los Angeles County Democratic Party. At the April 2007 California State Democratic Convention, LYM activist Quincy O'Neal was elected vice-chairman of the California State Democratic Black Caucus, and Wynneal Innocentes was elected corresponding secretary of the Filipino Caucus.

In November 2007, Mark Fairchild returned to Illinois to promote legislation authored by LaRouche, called the Homeowners and Bank Protection Act of 2007, that would establish a moratorium on home foreclosure

s and establish a new federal agency to oversee all federal and state banks. He also promoted LaRouche's plan to build a high-speed railroad to connect Russia and the United States, including a tunnel under the Bering Strait

.

In 2009, the LaRouche movement printed pamphlets showing President Barack Obama

and Hitler laughing together, and posters of Obama wearing a Hitler-style mustache. In Seattle, police have been called twice in response to people threatening to tear the posters apart, or to assault the LaRouche supporters holding them. At one widely reported event, Congressman Barney Frank

referred to the posters as "vile, contemptible nonsense."

In March 2010, LaRouche Youth leader Kesha Rogers won the Democratic congressional primary in Houston, Texas' 22nd District. The following day, a spokeswoman for the Texas Democratic Party stated that "La Rouche members are not Democrats. I guarantee her campaign will not receive a single dollar from anyone on our staff."

The harassing of individuals and organizations is reportedly systematic and strategic. Some of the targets are prominent individuals, while others are common citizens speaking out against the movement. The group itself refers to these methods as "psywar techniques," and defends them as necessary to shake people up; George Johnson

has written that, believing the general population to be hopelessly indoctrinated by the mass media, they "fight back with words that stick in one's mind like shards of glass." He quotes movement member Paul Goldstein saying: "We're not very nice, so we're hated. Why be nice? It's a cruel world. We're in a war and the human race is up for grabs."

In the 1960s and 1970s, LaRouche were accused of fomenting violence at anti-war rallies with a small band of followers. According to LaRouche's autobiography, it was in 1969 that violent altercations began between his members and New Left

groups. He wrote that Mark Rudd

's faction began assaulting LaRouche's faction at Columbia University. "Other organized physical attacks against my friends would follow, inside the United States and abroad," he wrote. "Communist Party goon-squad attacks began in Chicago, in summer 1972, and continued sporadically up to the concerted assault launched during March 1973. During 1972, there was also a goon-attack on associates of mine by the SWP

."

According to the Village Voice and the Washington Post the National Caucus of Labor Committees

(NCLC), an organization founded and controlled by LaRouche, became embroiled in the early 1970s in conflicts with other leftist groups, culminating in "Operation Mop-Up" which consisted of a series of physical attacks on members of rival left wing groups.

During "Operation Mop-Up," LaRouche's New Solidarity reported NCLC confrontations with members of the Communist Party and Socialist Workers Party. One incident took place April 23, 1973 at a debate featuring Labor Committee mayoral candidate Tony Chaitkin

. The meeting erupted in a brawl, with chairs flying. Six people were treated for injuries at a local hospital. In Buffalo, two NCLC organizers were arrested and charged with 2nd degree felonious assault after an attack that left one person with a broken leg and another with a broken arm. Dennis King writes that LaRouche halted the operation when police arrested several of his followers on assault charges, and after the groups under attack formed joint defense teams.

In the mid-1973 the movement formed a Revolutionary Youth Movement to recruit and politicize members of street gangs in New York City and other eastern cities. In September 1973 ten members of the NCLC were arrested for causing a melee at a Newark City Council meeting that involved 100 demonstrators, reported to be the third incident that week. The NCLC reportedly trained some members in terrorist and guerilla warfare. Topics included weapons handling, explosives and demolition, close order drills, small unit tactics, and military history.

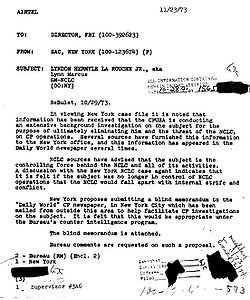

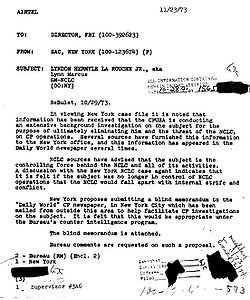

In November 1973, the FBI issued an internal memorandum that was later released under the Freedom of Information Act. Jeffrey Steinberg, the NCLC "director of counterintelligence", described it as the "COINTELPRO

In November 1973, the FBI issued an internal memorandum that was later released under the Freedom of Information Act. Jeffrey Steinberg, the NCLC "director of counterintelligence", described it as the "COINTELPRO

memo", which he says showed "that the FBI was considering supporting an assassination attempt against LaRouche by the Communist Party USA." LaRouche wrote in 1998:

The FBI was concerned that the movement might try to take power by force. FBI Director Clarence Kelly testified in 1976 about the LaRouche movement:

The LaRouche movement is reported to have harassed and threatened various federal agents from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s, in some cases reportedly directed by the security unit run by Jeffrey and Michelle Steinberg. Two young followers, Abi Steinberg and Andrea Konviser, told of calling FBI agents in the middle of the night to tell them dirty jokes in 1974, and such calls were reported again in 1978.

In the later 1970s, the U.S. Labor Party came into contact with Roy Frankhouser

, a convicted felon and government informant who had infiltrated a variety of extremist groups. The LaRouche organization believed Frankhouser to be a federal agent who had been assigned to infiltrate right-wing and left-wing groups, and that he had evidence that these groups were actually being manipulated or controlled by the FBI and other agencies. Frankhouser introduced LaRouche to Mitchell WerBell III

, a former Office of Strategic Services

operative, paramilitary trainer, and arms dealer. Some members allegedly took a six-day "anti-terrorist" course a training camp operated by WerBell in Powder Springs, Georgia. LaRouche denied in 1979 that the training sessions took place. WerBell introduced LaRouche to covert operations specialist General John K. Singlaub

, who later alleged that members of the movement implied in discussions with him that the military might help "lead the country out of its problems", a view which he rejected. WerBell also introduced LaRouche to Larry Cooper, a Powder Springs, Georgia

police captain. Cooper, Frankhouser and an associate of Frankhouser named Forrest Lee Fick later made allegations about LaRouche. Cooper said in an NBC broadcast interview in 1984 that LaRouche had proposed the assassination of Jimmy Carter

, Zbigniew Brzezinski

, Joseph Luns

, and David Rockefeller

. Frankhouser made numerous allegations about LaRouche, including that he said prosecutor William Weld

"does not deserve to live. He should get a bullet between the eyes." A spokesman for the movement "denied LaRouche had ever made such a statement". In 1984, LaRouche said that he had employed WerBell as a security consultant, but that the allegations coming from Werbell's circle were fabrications that originated with operatives of the FBI and other agencies.

In 1974 and 1975, the NCLC targeted the United Auto Workers

(UAW), United Farm Workers

(UFW), and other trade unionists. They declared open war and dubbed their campaign "Operation Mop Up Woodcock", a reference to their violent anti-communist campaign of 1973 and to UAW president Leonard Woodcock

. The movement staged demonstrations that turned violent. They issued pamphlets attacking the leadership as corrupt and perverted. The UAW said that members had received dozens of calls a day accusing their relatives of homosexuality, reportedly at the direction of NCLC "security staff". Leaflets called an Ohio local president a "Woodcocksucker". The leadership of the AFL-CIO

was also attacked. During the same period, the LaRouche movement was closely associated with the Teamsters

union which was in a jurisdictional dispute with the UFW.

LaRouche put substantial effort into his first Democratic Primary, held February 1980 in New Hampshire

. Reporters, campaign workers, and party officials received calls from people impersonating reporters or ADL staff members, inquiring what "bad news" they had heard about LaRouche. LaRouche acknowledged that his campaign workers used impersonation to collect information on political opponents. Governor Hugh Gallen

, State Attorney General Thomas Rath and other officials received harassing phone calls. Their names appeared on a photocopied "New Hampshire Target List" acquired by Associated Press

, found in a LaRouche campaign worker's hotel room; the list stated, "these are the criminals to burn – we want calls coming in to these fellows day and night". LaRouche spokesman Ted Andromidas said, "We did choose to target those people for political pressure hopefully to prevent them from carrying out the kind of fraud that occurred in Tuesday's election." A New Hampshire journalist, Jon Prestage, had a tense interview with LaRouche and several of his associates, and was threatened if he used the interview in his story. A LaRouche associate denied responsibility for the dead cats.

In the mid-1980s LaRouche moved his headquarters from New York City to Leesburg, Virginia

. The movement invested in real estate, opened offices, started a newspaper, bought a radio station, and opened a bookstore. Hundreds of followers settled in the area. The newspaper, The Loudoun County News, ran advertisements for local merchants without their authorization to give the impression of community support, and claimed harassment when challenged. Residents, including Agnes Harrison and Leesburg Mayor Robert Sevila, reported that armed guards quickly appeared and pointed guns at people who stopped along the road outside LaRouche's estate. Local critics reported receiving threatening phone calls. LaRouche followers handed out leaflets in front of a church which said that five local residents had "allied themselves knowingly with persons and organizations which are part of the international drug lobby."

A Leesburg businessman who told a reporter about rumors of injuries to animals, including a horse who was poisoned and a dog who had been skinned, was sued for $2 million, and when the suit was dismissed by a district judge the LaRouche movement appealed it to the Virginia Supreme Court. The Leesburg Garden Club was singled out for attention. LaRouche called it a "nest of Soviet fellow travellers," whose members were "cacking busybodies in this Soviet jellyfish front, sitting here in Leesburg oozing out their funny little propaganda and making nuisances of themselves." Warren J. Hammerman, chairman of the National Democratic Policy Committee, said "Because the drug-running threat is Soviet-backed and the Garden Club is fighting LaRouche on drugs, they are serving as Soviet agents."

According to courtroom testimony by FBI agent Richard Egan, Jeffrey and Michelle Steinberg, the heads of LaRouche's security unit, boasted of placing harassing phone calls all through the night to the general counsel of the Federal Elections Commission (FEC) when the FEC was investigating LaRouche's political contributions.

During the grand jury hearings followers picketed the courthouse, chanted "Weld is a fag", distributed leaflets accusing Weld of involvement in drug dealing, and "sang a jingle advocating that he be hanged in public".

The Schiller Institute

sent a team of ten people, headed by James Bevel

, to Omaha, Nebraska

, to pursue the Franklin child prostitution ring allegations

in 1990. Among the charges investigated by the grand jury was that the Omaha Police Chief Robert Wadman and other men had sex with a 15-year old woman at a party held by the bank's owner. The LaRouche groups insisted there was a coverup. They distributed copies of the Schiller Institute's New Federalist newspaper that contained accusations about leading Omaha citizens, especially Wadman. They went door-to-door in Wadman's neighborhood telling residents that their neighbor was a child molester. When Wadman took a job with the police department in Aurora, Illinois

, LaRouche followers went there to demand that he be fired, and after he left there they followed him to a third city to make accusations.

In the 1970s, Nelson Rockefeller

was a central figure in the conspiracy theories espoused by LaRouche. An FBI file described the LaRouche movement as "clandestinely oriented group of political schizophrenics who have a paranoid preoccupation with Nelson Rockefeller and the CIA." Rockefeller's nomination for U.S. Vice President was strongly opposed by the LaRouche movement, and its members heckled his appearances. Federal authorities were reported to be concerned that the movement's hatred of Rockefeller would turn violent.

A special target of LaRouche's attention is Henry Kissinger

. LaRouche called Kissinger a "faggot", a "British agent", a "Soviet agent of influence", a "traitor", a "Nazi", and a "murderer", and linked him to the murder of Aldo Moro

. His followers heckled and disrupted Kissinger's appearances. The same year a member of LaRouche's Fusion Energy Foundation

, Ellen Kaplan, shouted "Is it true that you sleep with young boys at the Carlyle Hotel?" at Kissinger on an airport terminal while he and his wife, Nancy, were on their way to a heart operation. In response, Nancy Kissinger grabbed the woman by the throat. Kaplan pressed charges and the case went to trial. In 1986 Janice Hart held a press conference to say that Kissinger was part of the international "drug mafia". Asked whether Jews were behind drug trafficking Hart replied, "That's totally nonsense. I don't consider Henry Kissinger a Jew. I consider Henry Kissinger a homosexual."

A LaRouche organization distributed almost-pornographic posters of Illinois politician Jane Byrne

, and called other female politicians "prostitutes" and their husbands "pimps", according to Mike Royko

. In 1986, two LaRouche candidates, Janice Hart

and Mark Fairchild, won surprise victories in the Democratic primaries for two statewide positions in Illinois, Secretary of State and Lieutenant Governor. Campaign appearances by democratic gubernatorial candidate Adlai Stevenson III

, who refused to share the ticket with them and shifted instead to the "Solidarity Party" formed for the purpose, were interrupted by a trio of singers that included Fairchild and Chicago Mayoral candidate Sheila Jones. Illinois Attorney General Neil Hartigan

's home was visited late at night by a group of LaRouche followers who chanted, sang, and used a bullhorn "to exorcise the demons out of Neil Hartigan's soul". Hart and an associate were charged with disorderly conduct when they handed a piece of raw liver to the Roman Catholic Archbishop Rembert Weakland

of Milwaukee who was addressing a synagogue in Glencoe

, saying that it represented the "pound of flesh extracted by Hitler" during the Holocaust. Before the primaries a group of LaRouche supporters reportedly stormed the campaign offices of Hart's opponent and demanded that a worker "take an AIDS test".

In 1984 a reporter for a LaRouche publication buttonholed President Ronald Reagan

as he was leaving a White House

press conference, demanding to know why LaRouche was not receiving Secret Service

protection. As a result, future press conferences in the East Room

were arranged with the door behind the president so he can leave without passing through the reporters. In 1992, a follower shook hands with President George H.W. Bush at a campaign visit to a shopping center. The follower would not let go, demanding to know, "When are you going to let LaRouche out of jail?" The Secret Service had to intervene.

During the 1988 presidential campaign, LaRouche activists spread a rumor that the Democratic candidate, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis

, had received professional treatment for two episodes of mental despression. Media sources did not report the rumor initially to avoid validating it. However at a press conference a reporter for a LaRouche publication, Nicholas Benton, asked President Reagan whether Dukakis should release his medical records. Reagan replied "Look, I'm not going to pick on an invalid." Within an hour after the press conference Reagan apologized for the joke. The question received wide publicity, and was later analyzed as an example of how journalists should handle rumors. Republican candidate Vice President George H.W. Bush's aides got involved in sustaining the story, and Dukakis was obliged to deny having had depression. To avoid the negative backlash on his own campaign, Bush made a statement urging Congress to pass the Americans with Disabilities Act, which he signed upon gaining office and which became one of his proudest legacies.

At a 2003 Democratic primary debate repeatedly interrupted by hecklers, Joe Lieberman

quoted John McCain

, "no one's been elected since 1972 that Lyndon LaRouche and his people have not protested". The first reported incidence of heckling by LaRouche followers was at the Watergate hearings in 1973. Since then, LaRouche followers have interrupted events featuring J. Bowyer Bell

, Andrew Bernstein

, Julian Bond

, Jerry Brown

, Richard R. Burt, George H.W. Bush, George W. Bush

, Jimmy Carter

, Wesley K. Clark, Howard Dean

, John Edwards

, Bob Kerrey

, John Kerry

, Lawrence Klein

, Richard Lamm

, Joseph Lieberman, Sir Robert Mark

, Paul Martin

, Walter Mondale

, Ralph Nader

, Oliver North

, Ross Perot

, Rick Santorum

, Sergio Sarmiento, Paul A. Volcker, and Leonard Woodcock

. LaRouche followers have disrupted political debates, college classes, meetings of a United Nations

development study group and of Ayn Rand

supporters on university campuses, and even a Columbus Day parade in New York City.

Joe Klein

writes that Boston's The Real Paper

decided to write an article about the LaRouche movement as a result of the violence in 1973. One reporter who attended a NCLC meeting was thrown against a wall. LaRouche called Klein "a liar and a degenerate", and Klein's family began receiving threatening calls. Journalist Charles Fager says that his article on LaRouche for the paper was spiked because of legal and physical threats.

Chicago Tribune

columnist Mike Royko

wrote several times of being harassed by the LaRouche movement, which he had covered since at least 1979. He once traced to the LaRouche movement leaflets which claimed that he had undergone a sex-change operation. (He wrote that it did not bother him as he had evidence to the contrary.) Royko wrote that, after writing about a LaRouche front group called "Citizens for Chicago", his assistant found a note attached to her apartment door that had a bullseye and a threat to kill her cat. LaRouche followers denied the allegation. In 1986, LaRouche followers picketed Royko's newspaper offices calling him a "degenerate drug pusher" and demanding that he take an AIDS test. When LaRouche was imprisoned in 1989, Royko wrote a column to inform LaRouche's fellow inmates about the history of cat killing and suggested that "any cat-lovers among them do whatever they feel is appropriate." LaRouche sought an injunction to prevent the column, which the suit said used "fighting words", from being printed in the paper near his jail but his request was rejected by the Circuit Court.

Dennis King began covering LaRouche in the 1970s, publishing a twelve-part series in a weekly Manhattan newspaper, Our Town, and later writing or cowriting articles about LaRouche in New Republic

, High Times, Columbia Journalism Review

, and other periodicals, culminating in a full length biography published in 1989. King describes numerous instances of harassment and threats. Leaflets accusing King, a news paper publisher, and the newspaper's lawyer of being criminals, homosexuals, or drug pushers. One leaflet included King's home address and phone number. He says that in 1980 he received a phone call threatening him with rape and murder, one of an estimated 500 abusive or hang-up calls he received by 1985. In 1984 a LaRouche newspaper, New Solidarity, published an article titled "Will Dennis King Come out of the Closet?", copies of which were distributed in his apartment building. His family also received calls that included threats to murder King. Jeffrey Steinberg denied the movement had harassed King. LaRouche said that King had been "monitored" since 1979, "We have watched this little scoundrel because he is a major security threat to my life."

In 1984, Patricia Lynch was a co-produceer of an NBC news piece and a TV documentary on LaRouche. She was then impersonated by LaRouche followers who interfered with her reporting. LaRouche sued Lynch and NBC for libel, and NBC countersued. During the trial followers picketed the NBC's offices with signs that said "Lynch Pat Lynch", and the NBC switchboard received a death threat. A LaRouche spokesman said they had no knowledge of the death threat. In later years LaRouche accused NBC or its reporters of various charges. At a press conference in 1986 he refused to take questions from the NBC reporter, saying "How could I talk to a drug pusher like you." In addition to charge of drug dealing, LaRouche publications also accused NBC of plotting his assassination.

The state editor of the Centre Daily Times in State College, Pennsylvania

reported that a LaRouche TV crew led by Stanley Ezrol talked their way into his house in 1985 implying they were with NBC, then accused him of harassing LaRouche and interrogated him about why he had written what they alleged were negative stories about LaRouche. At the end of the interview" Ezrol asked "Have you ever feared for your personal safety?", which the editor found to be "chilling". Another LaRouche group, including Janice Hart

, forced their way into the office of The Des Moines Registers editor in 1987, then harangued him over his papers's coverage of LaRouche and demanded that certain editorials be retracted because the paper's "economic policies stink".

From the 1970s to the 2000s, LaRouche followers have staffed card tables in airports and in front of post offices, state offices, college quads, and grocery stores. The tables have typically carried posters with topical slogans. LaRouche followers have been noted for using a confrontational style of interactions. In 1986, the New York state elections board received dozens of complaints about people collecting signatures on nomination petitions, including allegations of misrepresentation and abusive language used towards those who would not sign.

From the 1970s to the 2000s, LaRouche followers have staffed card tables in airports and in front of post offices, state offices, college quads, and grocery stores. The tables have typically carried posters with topical slogans. LaRouche followers have been noted for using a confrontational style of interactions. In 1986, the New York state elections board received dozens of complaints about people collecting signatures on nomination petitions, including allegations of misrepresentation and abusive language used towards those who would not sign.

In the mid-80s, the Secretary of State of California, March Fong Eu

, received numerous complaints from the public about harassment by people gathering signatures to qualify the "LaRouche AIDS Initiative

" for the state ballot. She warned initiative sponsors that permission to circulate the petitions could be revoked unless the "offensive activities" stopped. An altercation in 1987 between a LaRouche activist and an AIDS worker resulted in battery charges filed against the latter, who was outraged by the content of some of the material on display; she was found not guilty.

In California in 2009, several grocery chains sought restraining orders, damages and injunctions against LaRouche PAC activists displaying materials related to Obama's health care plan in front of their stores, citing customer complaints. In Edmonds, Washington

, a 70-year old man from Armenia

grew irate at the comparisons of Obama and Hitler. He grabbed fliers and tussled with LaRouche supporters, resulting in assault charges against him.

(NALP) nominated candidates in federal elections in the 1970s. Its candidates only had 297 votes nationwide in 1979. LaRouche himself offered a draft constitution for the commonwealth of Canada in 1981. The NALP later became the Party for the Commonwealth of Canada

and that ran candidates in the 1984, 1988 and 1993 elections. Those were more successful, gaining as many as 7,502 votes in 1993, but no seats. The Parti pour la république du Canada (Québec)

nominated candidates for provincial elections in the 1980s under various party titles. The LaRouche affiliate now operates as the Committee for the Republic of Canada.

's Party for Rebuilding of National Order (PRONA) is described as a "LaRouche friend" and one of its members has been quoted in the Executive Intelligence Review as saying "We associate ourselves with the wave of ideas which flow from Mr. LaRouche's prodigious mind". PRONA gained six seats in the Chamber of Deputies in 2002. However there is no independent evidence that the PRONA or its leaders recognize LaRouche as an influence on their policies, and it has been described as being part of the right-wing Catholic integralist political tradition.

The Ibero-American Solidarity Movement (MSIA) has been described as an offshoot of LaRouche's Labor Party in Mexico. During peace talks to resolve the Chiapas conflict

, the Mexican Labor Party and the Ibero-American Solidarity Movement (MSIA) attacked the peace process and one of the leading negotiators, Bishop Samuel Ruiz Garcia, who it accused of formenting the violence and of being controlled by foreigners. Posters caricaturing Ruiz as a rattlesnake appeared across the country.

The movement strongly opposes perceived manifestations of neo-colonialism, including the International Monetary Fund

, the Falklands/Malvinas War

, etc., and are advocates of the Monroe Doctrine

.

LaRouche supporters gained control of the formerly far-right Citizens Electoral Council

LaRouche supporters gained control of the formerly far-right Citizens Electoral Council

(CEC) in the mid-1990s. The CEC publishes an irregular newspaper, The New Citizen. Craig Isherwood and his spouse Noelene Isherwood are the leaders of the party. The CEC has opposed politician Michael Danby

and the 2004 Australian anti-terrorism legislation

. For the 2004 federal election, it nominated people for ninety-five seats, collected millions of dollars in contributions, and earned 34,177 votes.

The CEC is particularly concerned with Hamiltonian

economics and development ideas for Australia. It has been critical of Queen Elizabeth II

's ownership of an Australian zinc mine and believes that she exerts control over Australian politics through the use of prerogative power. It has been in an antagonistic relationship with the B'nai B'rith

's Anti-Defamation Commission, which has been critical of the CEC for perceived anti-semitism. It has asserted that the Liberal Party

is a descendant of the New Guard

and other purported fascists such as Sir Wilfrid Kent Hughes

and Sir Robert Menzies

. The CEC also claims to be fighting for "real" Labor policies (from the 1930-40s republican leanings of the Australian Labor Party

).

(BüSo) (Civil Rights Movement Solidarity) political party is headed by Helga Zepp-LaRouche

, LaRouche's wife. It has nominated candidates for elective office and publishes the Neue Solidarität newspaper. Zepp-LaRouche is also the head of the German-based Schiller Institute

. In 1986 Zepp-LaRouche formed the "Patriots for Germany" party, and reportedly ran a full slate of 100 candidates. The party received 0.2 percent of the 4 million votes. In Germany, the leader of the Green Party, Petra Kelly

, reported receiving harassing phone calls that she attributed to BüSo supporters. Her speeches were picketed and disrupted by LaRouche followers for years.

Jeremiah Duggan

, a Jewish student from the UK attending a conference organized by the Schiller Institute and LaRouche Youth Movement in 2003, died in Wiesbaden, Germany, after he ran down a busy road and was hit by several cars. The German police said it appeared to be suicide. A British court ruled out suicide and decided that Duggan had died while "in a state of terror." Duggan's mother believes he died in connection with an attempt to recruit him; a spokesman for the German public prosecution service said the mother simply cannot accept that her son committed suicide. The High Court in London ordered a second inquest in May 2010, which was opened and adjourned.

Solidarité et Progrès, headed by Jacques Cheminade

, is the LaRouche party in France

. Its newspaper is Nouvelle Solidarité. The French LaRouche Youth Movement is headed by Elodie Viennot. Viennot supported the candidacy of Daniel Buchmann for the position of mayor of Berlin.

Sweden has an office of the Schiller Institute: Schillerinstitutet/EAP in Sweden, and the political party European Worker's Party (EAP). The former leader of the EAP, Ulf Sandmark (replaced by Hussein Askary in 2007) started out as a member of the Swedish Social Democratic Youth League

Sweden has an office of the Schiller Institute: Schillerinstitutet/EAP in Sweden, and the political party European Worker's Party (EAP). The former leader of the EAP, Ulf Sandmark (replaced by Hussein Askary in 2007) started out as a member of the Swedish Social Democratic Youth League

(SSU), and was assigned to investigate (some would say infiltrate

) the EAP and the left-posturing ELC. During this time, he was recruited to EAP and had his membership in SSU revoked. Following the Olof Palme assassination

on February 28, 1986, the Swedish branch of the EAP came under scrutiny as literature published by the party was found in the apartment of the initial suspect, Victor Gunnarsson

. Also, the attacks against Olof Palme

run by the LaRouche movement since the beginning of the 1970s made the party a target for investigation. Within weeks of the assassination, NBC

television in the U.S. broadcast a story alleging that LaRouche was somehow responsible. Later, the suspect was released.

In Denmark

, four candidates for parliament on the LaRouche platform (Tom Gillesberg, Feride Istogu Gillesberg, Hans Schultz and Janus Kramer Møller) won 197 votes in the 2007 election (at least 32,000 votes are needed for a local mandate). The Danish LaRouche Movement (Schiller Instituttet) have recently published their first newspaper, distributing 50,000 around Copenhagen and Aarhus

.

The Movimento Solidarietà - Associazione di LaRouche in Italia (MSA) is an Italian

political party headed by Paolo Raimondi that supports the LaRouche platform.

Ortrun Cramer of the Schiller Institute became a delegate of the Austria

n International Progress Organization

in the 1990s, but there is no sign of ongoing relationship.

Polish newspapers have reported that Andrzej Lepper

, who leads the populist Samoobrona party, was trained at the Schiller Institute and has received funding from LaRouche, though both Lepper and LaRouche deny the connection.

In February 2008, the LaRouche movement throughout Europe began a campaign to prevent the ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon

, which according to the U.S.-based LaRouche Political Action Committee "empowers a supranational financial elite to take over the right of taxation and war making, and even restore the death penalty, abolished in most nations of Western Europe." LaRouche press releases suggest that the treaty has an underlying fascist agenda, based on the ideas of Sir Oswald Mosley

.

LaRouche Society calls for fixed exchange rate

s, US/Philippine withdrawal from Iraq, denunciation of former US Vice President Dick Cheney

, and withdrawal of U.S. military advisor

s from Mindanao

. In 2008 it also issued calls for the freezing of foreign debt payments, the operation of the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant, and the immediate implementation of a national food production program. It has an office in Manila

, operates a radio show and says on its website, "Lyndon LaRouche is our civilization's last chance at world peace and development. May God help us." On the matter of internal politics, LaRouche operative Mike Billington

wrote in 2004, "The Philippines Catholic Church, too, is divided at the top over the crisis. The Church under Jaime Cardinal Sin

, who is now retired, had given its full support to the 'people's power' charade for the overthrow of Marcos

and Estrada

, but other voices are heard today." Later that year, he wrote that

According to Billington, representatives of LaRouche's Executive Intelligence Review

and Schiller Institute

had met with Marcos in 1985, at which time LaRouche was warning that Marcos would be the target of a coup, inspired by George Shultz and neoconservatives in the Reagan administration, because of Marcos' opposition to the policies of the International Monetary Fund

. In 1986, LaRouche asserted that Marcos was ousted because he hadn't listened to LaRouche's advice: "he was opposed to me and he fell as a result."

The LaRouche movement is reported to have had close ties to the Ba'ath Party of Iraq

.

The LaRouche movement, and the Schiller Institute in particular, were reported in 1997 to have campaigned aggressively in support of the National Islamic Front

government in Sudan

. They organized trips to Sudan for state legislators, which according to the Christian Science Monitor was part of a campaign directed at African Americans.

, as "one of the best private intelligence services in the world."

According to its masthead, EIR maintains international bureaus in Bogotá

, Berlin

, Copenhagen

, Lima

, Melbourne

, Mexico City

, New Delhi

, Paris

, and Wiesbaden

, in addition to various cities in the U.S. EIR staffers have provided testimony to various congressional committees, and an archive of EIR is maintained by the British Library of Political and Economic Science.

In 1996, EIR published the list of MI-6 agents provided by former MI-6 officer Richard Tomlinson

.

One element of EIR was the Biological Holocaust Task Force, formed in 1973 to study and anticipate the effects of IMF Conditionalities

on the populations of the Third World

, particularly in Africa

. It was headed by Dr. John Grauerholz.

The president of EIR News Service is Linda de Hoyos.

, a low-powered AM radio station that covered western Maryland, northern Virginia, and parts of West Virginia. It was sold in 1991.

In 1991, the LaRouche movement began producing The LaRouche Connection, a Public-access television

cable TV program. Within ten months it was being carried in six states. Dana Scanlon, the producer, said that "We've done shows on the JFK assassination, the 'October Surprise' and shows on economic and cultural affairs". Scanlon won an award for producing more than 30 segments.

s every 1–2 months. These were public meetings, broadcast in video, where LaRouche gave a speech, followed by 1–2 hours of Q and A over the internet. In his January 3, 2001 webcast, shortly before the inauguration of George W. Bush

, LaRouche warned that the incoming Bush administration would attempt to govern by crisis management

, "...in other words, just like the Reichstag fire

in Germany."

(ADL) was sued by the U.S. Labor Party

, the National Caucus of Labor Committees

, and several individuals including Konstandinos Kalimtgis, Jeffrey Steinberg, and David Goldman

, who claimed libel, slander, invasion of privacy, and assault on account of the ADL's accusations of anti-Semitism. A New York State Supreme Court judge ruled that it was "fair comment

" to describe them as anti-Semites

.

United States v. Kokinda was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1990. The case concerned the First Amendment rights of LaRouche movement members on Post Office property. The Deputy Solicitor General arguing the government's case was future Supreme Court Chief Justice John G. Roberts. The Court confirmed the convictions of Marsha Kokinda and Kevin Pearl, volunteers for the National Democratic Policy Committee, finding that the Postal Service's regulation of solicitors was reasonable.

, the movement is based on a commitment to "a just new world economic order," specifically "the urgency of affording what have been sometimes termed 'Third World nations,' their full rights to perfect national sovereignty, and to access to the improvement of their educational systems and economies through employment of the most advanced science and technology."

The LaRouche movement has attracted devoted followers and developed some specific and elaborate policy initiatives, but has also been referred to variously as Marxist, fascist, anti-Semitic, a political cult

, a personality cult, and a criminal enterprise. In 1984, LaRouche's research staff was described by Norman Bailey, a former senior staffer of the United States National Security Council

, as "one of the best private intelligence services in the world". The Heritage Foundation

calls it "one of the strangest political groups in American history", and The Washington Monthly

calls it a "vast and bizarre vanity press".

The LaRouche movement is seen as a fringe political cult

.

Journalist and John Birch Society

activist John Rees

wrote in his Information Digest that the movement has "taken on the characteristics more of a political cult than a political party", and that LaRouche is given "blind obedience" by his followers. He has also called the movement a "cult of personality

". In rebuttal, LaRouche called the accusations of being a cult figure "garbage", and denied having control over any of the groups affiliated with him.

According to longtime critics Chip Berlet

and Matthew N. Lyons:

In the summer of 2009, LaRouche followers came under criticism from both Democrats and Republicans for comparing President Barack Obama to Hitler. Media figures as politically widespread as Rush Limbaugh and Jon Stewart criticized the comparison.

According to the Washington Post, LaRouche has told his followers that they are "golden souls", a term from The Republic of Plato

. In his 1979 autobiography he contrasted the "golden souls" to "the poor donkeys, the poor sheep, whose consciousness is dominated by the infantile world-outlook of individual sensuous life". According to Dennis King, LaRouche believed that cadres "must be intellectually of a superior breed—a philosophical elite as well as a political vanguard". In 1986, LaRouche said during an interview, "What I represent is a growing movement. The movement is becoming stronger all the time..."

During the criminal trials of the late 1980s, LaRouche called upon his followers to be martyrs, saying that their "honorable deeds shall be legendary in the tales told to future generations". Senior members refused plea agreements that involved guilty pleas as those would have been black marks on the movement.

Former members report that life within the LaRouche movement is highly regulated. A former member of the security staff wrote in 1979 that members could be expelled for masturbating or using marijuana. Members who failed to achieve their fundraising quotas or otherwise showed signs as disloyal behavior were subjected to "ego stripping" sessions. Members, even spouses, were encouraged to inform on each other, according to an ex-member. Although LaRouche was officially opposed to abortion, a former member testified that women were encouraged to have abortions because "you can't have children during a revolution." Another source said some group leaders coerced members into having abortions. John Judis

, writing in The National Review, stated that LaRouche followers worked 16-hour days for little wages.

Former members have reported receiving harassing calls or indirect death threats. They say they have been called traitors. New Solidarity ran obituaries for three living former members. Internal memos have reportedly contained a variety of dismissive terms for ex-followers. One former member said that becoming a follower of LaRouche is "like entering the Bizarro World of the Superman comic books" which makes sense so long as one remains inside the movement.

In 1992, the father of Lewis du Pont Smith, an adult member of the Du Pont family

who had joined the LaRouche movement, was indicted along with four associates for planning to have his son and daughter-in-law abducted and "deprogrammed

". The incident resulted in serious legal repercussions but no criminal convictions for those indicted, including private investigator Galen Kelly

. The father also successfully had his son declared "incompetent" to manage his financial affairs in order to block him from possibly turning over his inheritance to the LaRouche organization.

Kenneth Kronberg

, who had been a leading member of the movement, committed suicide in 2007, reportedly because of financial issues concerning the movement. His widow, Marielle (Molly) Kronberg, had also been a longtime member. She gave an interview to Chip Berlet

in 2007 in which she made critical comments about the LaRouche movement. She was quoted as saying, "I'm worried that the organization may be in danger of becoming a killing machine." In 2004 and 2005, Kronberg made contributions of $1,501 to the Republican National Committee

and the election campaign of George W. Bush

, despite the LaRouche movement's opposition to the Bush administration. According to journalist Avi Klein, LaRouche felt that this "foreshadowed her treachery to the movement." Kronberg had been a member of the movement's governing National Committee since 1982 and was convicted of fraud during the LaRouche criminal trials.

Lyndon LaRouche

Lyndon Hermyle LaRouche, Jr. is an American political activist and founder of a network of political committees, parties, and publications known collectively as the LaRouche movement...

and his ideas. It has included scores of organizations and companies around the world. Their activities include campaigning, private intelligence gathering, and publishing numerous periodicals, pamphlets, books, and online content. It characterizes itself as a Platonist Whig movement which favors re-industrialization and classical culture, and which opposes what it sees as the genocidal conspiracies of Aristotelian oligarchies such as the British Empire. Outsiders characterize it as a fringe movement and it has been criticized from across the political spectrum.

The movement had its origins in radical leftist student politics of the 1960s, but is now generally seen as a right-wing, fascist or unclassifiable group. It is known for its unusual theories and its confrontational behavior. In the 1970s members allegedly engaged in street violence. In the 1970s and 1980s hundreds of candidates, some with only limited knowledge of LaRouche or the movement, ran as Democrats

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

on the LaRouche platform. None were elected to significant public office.

In 1988, LaRouche and 25 associates were convicted on fraud charges related to fund-raising, prosecutions which the movement alleged were politically motivated and which were followed by a decline in the group's influence which lasted for several years. The movement was rejuvenated in the 2000s by the creation of a youth cadre, the LaRouche Youth Movement, and by their prominent opposition to the Bush/Cheney administration and the Obama health care reform plan.

LaRouche's wife, Helga Zepp-LaRouche

Helga Zepp-LaRouche

Helga Zepp-LaRouche is a German political activist, wife of American political activist Lyndon LaRouche, and founder of the LaRouche movement's Schiller Institute and the German Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität party .She has run for political office several times in Germany, representing small...

, heads political and cultural groups in Germany connected with her husband's movement. There are also parties in France, Sweden, and other European countries, and branches or affiliates in Australia, Canada, the Philippines, and several Latin American countries. Estimates of the movement range from five hundred to one thousand members in the United States, spread across more than a dozen cities, and about the same number abroad. Members engage in political organizing, fund-raising, cultural events, research and writing, and internal meetings. It has been categorized as a political cult by some journalists. According to reporters, members believe they are solely responsible for the protection of civilization and some work long hours for little pay to further their mission. The LaRouche movement has been accused of repeatedly harassing public officials, politicians, journalists, ex-members, and critics. The movement has had a number of notable collaborators and members.

Political organizations

In 1986, LaRouche testified that there is "no such thing as a LaRouche organization". A spokesman said LaRouche was like the "guiding light" of a variety of "separate organizations".LaRouche-affiliated political parties have nominated many hundreds of candidates for national and regional offices in the U.S.

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, Canada

Canada

Canada is a North American country consisting of ten provinces and three territories. Located in the northern part of the continent, it extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the east to the Pacific Ocean in the west, and northward into the Arctic Ocean...

, Sweden

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

, Denmark

Denmark

Denmark is a Scandinavian country in Northern Europe. The countries of Denmark and Greenland, as well as the Faroe Islands, constitute the Kingdom of Denmark . It is the southernmost of the Nordic countries, southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark...

, Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, Australia

Australia

Australia , officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country in the Southern Hemisphere comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous smaller islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It is the world's sixth-largest country by total area...

and France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, for almost thirty years. In countries outside the U.S., the LaRouche movement maintains its own minor parties, and they have had no significant electoral success to date. In the U.S., however, they are active in the Democratic Party, and individuals associated with the movement have successfully sought party office in some elections, particularly Democratic County Central Committee posts.

International

The Schiller InstituteSchiller Institute

The Schiller Institute is an international political and economic thinktank, one of the primary organizations of the LaRouche movement, with headquarters in Germany and the United States, and supporters in Australia, Canada, Russia, and South America, among others, according to its website.The...

and the International Caucus of Labor Committees (ICLC) are international organizations that mobilize on behalf of the LaRouche Movement. Schiller Institute conferences have been held across the world. The ICLC is affiliated to political parties in France

France

The French Republic , The French Republic , The French Republic , (commonly known as France , is a unitary semi-presidential republic in Western Europe with several overseas territories and islands located on other continents and in the Indian, Pacific, and Atlantic oceans. Metropolitan France...

, Italy

Italy

Italy , officially the Italian Republic languages]] under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. In each of these, Italy's official name is as follows:;;;;;;;;), is a unitary parliamentary republic in South-Central Europe. To the north it borders France, Switzerland, Austria and...

, Germany

Germany

Germany , officially the Federal Republic of Germany , is a federal parliamentary republic in Europe. The country consists of 16 states while the capital and largest city is Berlin. Germany covers an area of 357,021 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate...

, Poland

Poland

Poland , officially the Republic of Poland , is a country in Central Europe bordered by Germany to the west; the Czech Republic and Slovakia to the south; Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania to the east; and the Baltic Sea and Kaliningrad Oblast, a Russian exclave, to the north...

, Hungary

Hungary

Hungary , officially the Republic of Hungary , is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is situated in the Carpathian Basin and is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine and Romania to the east, Serbia and Croatia to the south, Slovenia to the southwest and Austria to the west. The...

, Russia

Russia

Russia or , officially known as both Russia and the Russian Federation , is a country in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects...

, Denmark

Denmark

Denmark is a Scandinavian country in Northern Europe. The countries of Denmark and Greenland, as well as the Faroe Islands, constitute the Kingdom of Denmark . It is the southernmost of the Nordic countries, southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark...

, Sweden

Sweden

Sweden , officially the Kingdom of Sweden , is a Nordic country on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. Sweden borders with Norway and Finland and is connected to Denmark by a bridge-tunnel across the Öresund....

, Mexico

Mexico

The United Mexican States , commonly known as Mexico , is a federal constitutional republic in North America. It is bordered on the north by the United States; on the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; on the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and on the east by the Gulf of...

, the Philippines

Philippines

The Philippines , officially known as the Republic of the Philippines , is a country in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean. To its north across the Luzon Strait lies Taiwan. West across the South China Sea sits Vietnam...

, and several South American countries. Lyndon LaRouche, who is based in Loudoun County, Virginia

Loudoun County, Virginia

Loudoun County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia, and is part of the Washington Metropolitan Area. As of the 2010 U.S. Census, the county is estimated to be home to 312,311 people, an 84 percent increase over the 2000 figure of 169,599. That increase makes the county the fourth...

, United States

United States

The United States of America is a federal constitutional republic comprising fifty states and a federal district...

, and his wife, Helga Zepp-LaRouche

Helga Zepp-LaRouche

Helga Zepp-LaRouche is a German political activist, wife of American political activist Lyndon LaRouche, and founder of the LaRouche movement's Schiller Institute and the German Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität party .She has run for political office several times in Germany, representing small...

, based in Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden is a city in southwest Germany and the capital of the federal state of Hesse. It has about 275,400 inhabitants, plus approximately 10,000 United States citizens...

, Germany, regularly attend these international conferences and have met foreign politicians, bureaucrats, and academics.

Political activities

U.S. Labor Party

The U.S. Labor Party was a political party formed in 1973 by the National Caucus of Labor Committees . It served as a vehicle for Lyndon LaRouche to run for President of the United States in 1976, but it also sponsored many candidates for local offices and Congressional and Senate seats between...

. In the next seven campaigns he campaigned for the Democratic Party

Democratic Party (United States)

The Democratic Party is one of two major contemporary political parties in the United States, along with the Republican Party. The party's socially liberal and progressive platform is largely considered center-left in the U.S. political spectrum. The party has the lengthiest record of continuous...

nomination. In support of those efforts he has created campaign committees and a PAC

Political action committee

In the United States, a political action committee, or PAC, is the name commonly given to a private group, regardless of size, organized to elect political candidates or to advance the outcome of a political issue or legislation. Legally, what constitutes a "PAC" for purposes of regulation is a...

, and has attempted to gain entrance to caucus

Caucus

A caucus is a meeting of supporters or members of a political party or movement, especially in the United States and Canada. As the use of the term has been expanded the exact definition has come to vary among political cultures.-Origin of the term:...

es, debates, and conventions

Political convention

In politics, a political convention is a meeting of a political party, typically to select party candidates.In the United States, a political convention usually refers to a presidential nominating convention, but it can also refer to state, county, or congressional district nominating conventions...

for himself and supporters. He was a successful fundraiser

Fundraiser

A fundraiser is an event or campaign whose primary purpose is to raise money for a cause. See also: fundraising. A fundraiser can also be an individual or company whose primary job is to raise money for a specific charity or non-profit organization...

in 2004 by some measures, and received federal matching funds

Matching funds

Matching funds, a term used to describe the requirement or condition that a generally minimal amount of money or services-in-kind originate from the beneficiaries of financial amounts, usually for a purpose of charitable or public good.-Charitable causes:...

. See Lyndon LaRouche U.S. Presidential campaigns

Lyndon LaRouche U.S. Presidential campaigns

Lyndon LaRouche's U.S. Presidential campaigns were a staple of American politics between 1976 and 2004. LaRouche ran for president on eight consecutive occasions, a record for any candidate, and has tied Harold Stassen's record as a perennial candidate. LaRouche ran for the Democratic nomination...

.

In 1986 the LaRouche movement placed its AIDS

AIDS

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome is a disease of the human immune system caused by the human immunodeficiency virus...

initiative, Proposition 64

California Proposition 64 (1986)

Proposition 64 was a proposition in the state of California on the November 4, 1986 ballot. It was an initiative statute that would have restored Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome to the list of communicable diseases...

, on the California

California

California is a state located on the West Coast of the United States. It is by far the most populous U.S. state, and the third-largest by land area...

ballot, which lost by a 4-1 margin. It was re-introduced in 1988 and lost again by the same margin. Federal and state officials raided movement offices in 1986. In the ensuing trials, leaders of the movement received prison terms for conspiracy to commit fraud, mail fraud, and tax evasion. See LaRouche criminal trials.

In 1986, LaRouche movement members Janice Hart

Janice Hart

Janice Hart was an unsuccessful candidate for the office of Illinois Secretary of State in 1986.Hart, a political unknown and a LaRouche movement activist since the age of 17, unexpectedly won the Democratic Party's nomination. Her opponent, Aurelia Pucinski, came from a politically-prominent...

and Mark J. Fairchild won the Democratic Primary elections for the offices of Illinois Secretary of State and Illinois Lieutenant Governor

Lieutenant Governor of Illinois

The Lieutenant Governor of Illinois is the second highest executive of the State of Illinois. In Illinois, the lieutenant governor and governor run on a joint ticket, and are directly elected by popular vote. Candidates for lieutenant governor run separately in the primary from candidates for...

respectively. Up until the day following the election, major media outlets were reporting that George Sangmeister, Fairchild's primary opponent, was running unopposed. 21 years later Fairchild asked, “how is it possible that the major media, with all of their access to information, could possibly be mistaken in that way?” Democratic gubernatorial candidate Adlai Stevenson III

Adlai Stevenson III

Adlai Ewing Stevenson III is an American politician of the Democratic Party. He represented the state of Illinois in the United States Senate from 1970 until 1981.-Education, military service, and early career:...

was favored to win this election, having lost the previous election by a narrow margin amid allegations of vote fraud. However, he refused to run on the same slate with Hart and Fairchild. Instead, Stevenson formed the Solidarity Party

Solidarity Party

The Solidarity Party was an American political party in the state of Illinois. It was named after Lech Wałęsa's Solidarity movement in Poland, which was widely-admired in Illinois at the time .The party was founded in 1986 by Senator Adlai Stevenson III in reaction to the Democratic Party's...

and ran with Jane Spirgel as the Secretary of State nominee. Hart and Spirgel's opponent, Republican incumbent Jim Edgar

Jim Edgar

James Edgar is an American politician who was the 38th Governor of Illinois from 1991 to 1999 and Illinois Secretary of State from 1981 to 1991. As a moderate Republican in a largely blue-leaning state, Edgar was a popular and successful governor, leaving office with high approval ratings...

, won the election by the largest margin in any state-wide election in Illinois history, with 1.574 million votes.

After the Illinois primary Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-NY) blasted his own party for pursuing a policy of ignoring the "infiltration by the neo-Nazi elements of Lyndon H. LaRouche," and worried that too often, especially in the media, "the LaRouchites" are "dismissed as kooks." "In an age of ideology, in an age of totalitarianism, it will not suffice for a political party to be indifferent to and ignorant about such a movement," said Moynihan. Moynihan had previously faced a primary challenge in 1982 from Mel Klenetsky, a Jewish associate of LaRouche, and had called Klenetsky "anti-Semitic."

In 1988, Claude Jones won the chairmanship of the Harris County

Harris County, Texas

As of the 2010 Census, the population of the county was 4,092,459, White Americans made up 56.6% of Harris County's population; non-Hispanic whites represented 33.0% of the population. Black Americans made up 18.9% of the population. Native Americans made up 0.7% of Harris County's population...

Democratic Party in Houston, only to be stripped of his authority by the county executive committee before he could take office. He was removed from office by the state party chairman a few months later, in February 1989, because of Jones's alleged opposition to the Democratic presidential candidate, Michael Dukakis

Michael Dukakis

Michael Stanley Dukakis served as the 65th and 67th Governor of Massachusetts from 1975–1979 and from 1983–1991, and was the Democratic presidential nominee in 1988. He was born to Greek immigrants in Brookline, Massachusetts, also the birthplace of John F. Kennedy, and was the longest serving...

, in favor of LaRouche.

The LaRouche movement is reported by multiple sources, including journalists Jason Berry

Jason Berry

Jason Berry is an investigative reporter in New Orleans, an American author and film director. He is renowned for pioneering investigative reporting on sexual abuse in the priesthood of the Catholic Church....

and George Johnson

George Johnson (writer)

George Johnson is an American journalist and science writer. He is the author of a number of books, including The Ten Most Beautiful Experiments and Strange Beauty: Murray Gell-Mann and the Revolution in 20th-Century Physics , and writes for a number of publications, including The New York...

, to have had close ties to the Iraqi Ba'ath Party of Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein

Saddam Hussein Abd al-Majid al-Tikriti was the fifth President of Iraq, serving in this capacity from 16 July 1979 until 9 April 2003...

. It was a leading opponent of the UN sanctions

United Nations Security Council Resolution 661

In United Nations Security Council Resolution 661, adopted on August 6, 1990, reaffirming Resolution 660 and noting Iraq's refusal to comply with it and Kuwait's right of self-defence, the Council took steps to implement international sanctions on Iraq under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter...

against Iraq in 1991 and the subsequent Gulf War

Gulf War

The Persian Gulf War , commonly referred to as simply the Gulf War, was a war waged by a U.N.-authorized coalition force from 34 nations led by the United States, against Iraq in response to Iraq's invasion and annexation of Kuwait.The war is also known under other names, such as the First Gulf...

in 1992. Supporters formed the "Committee to Save the Children in Iraq". LaRouche blamed the sanctions and war on "Israeli-controlled Moslem fundamentalist groups" and the "Ariel Sharon-dominated government of Israel" whose policies were "dictated by Kissinger and company, through the Hollinger Corporation, which has taken over The Jerusalem Post for that purpose." Left-wing anti-war groups were divided over the LaRouche movement's involvement.

In 2000, the Democratic nominee in Wyoming for the Senate, Mel Logan, was a LaRouche follower; the Republican incumbent, Craig Thomas, won in a 76%-23% landslide. In 2001, a "national citizen-candidates' movement" was created, advancing candidates for a number of elective offices across the country.

In 2006, LaRouche Youth Movement activist and Los Angeles County Democratic Central Committee member Cody Jones was honored as "Democrat of the Year" for the 43rd Assembly District of California, by the Los Angeles County Democratic Party. At the April 2007 California State Democratic Convention, LYM activist Quincy O'Neal was elected vice-chairman of the California State Democratic Black Caucus, and Wynneal Innocentes was elected corresponding secretary of the Filipino Caucus.

In November 2007, Mark Fairchild returned to Illinois to promote legislation authored by LaRouche, called the Homeowners and Bank Protection Act of 2007, that would establish a moratorium on home foreclosure

Foreclosure

Foreclosure is the legal process by which a mortgage lender , or other lien holder, obtains a termination of a mortgage borrower 's equitable right of redemption, either by court order or by operation of law...

s and establish a new federal agency to oversee all federal and state banks. He also promoted LaRouche's plan to build a high-speed railroad to connect Russia and the United States, including a tunnel under the Bering Strait

Bering Strait

The Bering Strait , known to natives as Imakpik, is a sea strait between Cape Dezhnev, Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia, the easternmost point of the Asian continent and Cape Prince of Wales, Alaska, USA, the westernmost point of the North American continent, with latitude of about 65°40'N,...

.

In 2009, the LaRouche movement printed pamphlets showing President Barack Obama

Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II is the 44th and current President of the United States. He is the first African American to hold the office. Obama previously served as a United States Senator from Illinois, from January 2005 until he resigned following his victory in the 2008 presidential election.Born in...

and Hitler laughing together, and posters of Obama wearing a Hitler-style mustache. In Seattle, police have been called twice in response to people threatening to tear the posters apart, or to assault the LaRouche supporters holding them. At one widely reported event, Congressman Barney Frank

Barney Frank

Barney Frank is the U.S. Representative for . A member of the Democratic Party, he is the former chairman of the House Financial Services Committee and is considered the most prominent gay politician in the United States.Born and raised in New Jersey, Frank graduated from Harvard College and...

referred to the posters as "vile, contemptible nonsense."

In March 2010, LaRouche Youth leader Kesha Rogers won the Democratic congressional primary in Houston, Texas' 22nd District. The following day, a spokeswoman for the Texas Democratic Party stated that "La Rouche members are not Democrats. I guarantee her campaign will not receive a single dollar from anyone on our staff."

Alleged violence and harassment

The LaRouche movement members have had a reputation for engaging in violence, harassment, and heckling since the 1970s. While LaRouche repeatedly repudiated violence, followers were reported in the 1970s and 1980s to have been charged with possession of weapons and explosives along with a number of violent crimes, including kidnapping and assault. However there were few, if any, convictions on these charges.The harassing of individuals and organizations is reportedly systematic and strategic. Some of the targets are prominent individuals, while others are common citizens speaking out against the movement. The group itself refers to these methods as "psywar techniques," and defends them as necessary to shake people up; George Johnson

George Johnson (writer)

George Johnson is an American journalist and science writer. He is the author of a number of books, including The Ten Most Beautiful Experiments and Strange Beauty: Murray Gell-Mann and the Revolution in 20th-Century Physics , and writes for a number of publications, including The New York...

has written that, believing the general population to be hopelessly indoctrinated by the mass media, they "fight back with words that stick in one's mind like shards of glass." He quotes movement member Paul Goldstein saying: "We're not very nice, so we're hated. Why be nice? It's a cruel world. We're in a war and the human race is up for grabs."

1960s and Operation Mop-Up

In the 1960s and 1970s, LaRouche were accused of fomenting violence at anti-war rallies with a small band of followers. According to LaRouche's autobiography, it was in 1969 that violent altercations began between his members and New Left

New Left

The New Left was a term used mainly in the United Kingdom and United States in reference to activists, educators, agitators and others in the 1960s and 1970s who sought to implement a broad range of reforms, in contrast to earlier leftist or Marxist movements that had taken a more vanguardist...

groups. He wrote that Mark Rudd

Mark Rudd

Mark William Rudd is a political organizer, mathematics instructor, and anti-war activist, most well known for his involvement with the Weather Underground. Rudd became a member of the Columbia University chapter of Students for a Democratic Society in 1963. By 1968, he had emerged as a leader...