History of Sussex

Encyclopedia

Sussex from the Old English 'Sūþsēaxe' ('South Saxons'), was a county in the south east

of England

. The foundation of the Kingdom of Sussex is recorded by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

for the year AD 477, saying that Ælle arrived at a place called Cymenshore

in three ships with his three sons and killed or put to flight the local inhabitants.

The foundation story is regarded as somewhat of a myth by most historians, although the archaeology suggests that Saxons did start to settle in the area in the late 5th century. The Kingdom of Sussex became the county of Sussex; then after the coming of Christianity; the see originally founded in Selsey, was moved to Chichester in the 11th century. The See of Chichester was coterminous with the county borders. In the 12th century the see was split into two archdeaconries centred at Chichester and Lewes.

After the Reform Act of 1832 Sussex was divided into the eastern division and the western division, these divisions were coterminous with the two archdeaconries of Chichester and Lewes. Sussex ceased to exist as a political entity in 1974, when, under an act of parliament, its eastern division became the county of East Sussex and the western division the county of West Sussex. There are several organisations that still operate within the ancient borders of Sussex although it is now the two counties of East and West Sussex, some examples being the Diocese of Chichester

, Sussex Police

and Sussex Archaeological Society

.

Although the name Sussex is derived from the Saxon period between AD 477 to 1066, the history of human habitation in Sussex goes back to the Old Stone (Paleolithic

) Age. Sussex has been occupied since those times and although it has been an industrious county it has succumbed to various persecutions, wars, invasions, political unrest and migrations throughout its long history.

.

Boxgrove man apparently lived in a temperate stage immediately prior to the Anglian glaciation

, in the Lower Paleolithic period between 524,000 and 478,000 years ago.

In 1900 Upper Palaeolithic flintwork was found at a site in the Beedings. Then in 2007–08 Early Upper Palaeolithic archaeology was found at the same site. The archaeology at the Beedings spans a crucial cultural transition in the European Palaeolithic and therefore provides an important new dataset for the analysis of late Neanderthal groups in northern Europe and their replacement by modern human populations.

It is believed that during the Mesolithic

Age nomadic hunters arrived in Sussex from Europe. At the time (8000 BC), Britain was still connected to the continent, however the ice sheets over northern Europe were melting rapidly and causing the gradual rising of sea levels, which eventually led to the forming of the Straits of Dover, effectively cutting off the Mesolithic people of Sussex from the continent. There have been archaeological finds from these people, mostly in the central wealden

area to the north of the Downs. Large amounts of knives, scrapers, arrow heads and other tools have been found.

Close to the River Ouse

near Sharpsbridge, a polished axe, polished axe fragments, a chisel and other examples of Neolithic

flintwork have been found. The fact that these implements were found close to the River Ouse suggests that some land clearance may have taken place in the river valley during the Neolithic period.

From about 4300 BC to about 3400 BC the mining of flint for use locally and also for wider trade was a major activity in Neolithic Sussex. There was also a Neolithic pottery industry, with styles of pot reminiscent of finds elsewhere, such as Hembury and Grimston/ Lyle Hill.

in Sussex is marked by the appearance of Beaker pottery. There have been several finds including some in Beaker settlements, a significant settlement was one discovered near Beachy Head

, in 1909. The site was partially excavated in 1970 and the finds included pottery,flints, post settings, shallow pits and a midden

. The presence of Beaker pottery provides the first evidence of the migration of people from northern Europe since the early Neolithic period. Although some pre-historians now doubt the existence of the Beaker people as migrants and suggest that it was possible that the Beaker culture may have just been a new development of the local neolithic people.

From the Bronze Age

(about 1400-1100BC) settlements and burial sites have left their mark throughout Sussex.

Cissbury Ring

. A small number of agricultural settlements, or farmsteads, have been excavated on a large scale. The results of these excavations have provided a picture of the economy, based on mixed farming. Artefacts such as iron ploughshares and sickles were excavated.

The presence of animal bones, particularly cattle and sheep, attests to the pastoral element to their economy.

Various items have been found that indicate that they used to spin and weave the wool they produced.

The Sussex Iron Age dweller supplemented their diet with marine shellfish, the remains of which have been found on

several sites.

Towards the end of the Iron Age in 75BC, people from the Atrebates

one of the tribes of the Belgae

, a mix of Celtic and German stock, started invading and

occupying southern Britain. This was followed by an invasion by

the Roman army under Julius Caesar

that temporarily occupied the south-east in 55BC.

Then soon after the first Roman invasion had ended, the Celtic Regnenses

tribe under, their leader Commius

occupied the Manhood Peninsula

.

Tincomarus

and then Cogidubnus followed Commius as rulers of the Regnenses.

At the time of the Roman conquest in AD43 there was an oppidum

in the southern part of their territory, probably in the Selsey region.

(Chichester).

There are a variety of remains in the county from Roman times, coin hoards and decorated pottery have been found.

There are examples of Roman roads such as:

Also a variety of buildings, the best known being:

The coast of Roman Britain had a series of defensive forts on them, and towards the end of the Roman occupation the coast was subject to raids by Saxons

. Additional forts

were built against the Saxon threat, an example in Sussex being Anderitum

(Pevensey Castle

). The coastal defences were supervised by the Count of the Saxon Shore

. There is some suggestion that around the beginning of the fourth century the Roman authorities recruited mercenaries from the German homelands to defend the southern and eastern coasts of Britain. The area they defended was known as the Saxon Shore. It is possible that these mercenaries remained after the departure of the Roman army and merged with the eventual Anglo-Saxon invaders.

On Friday 13 October 1066, Harold Godwinson

and his English army arrived at Senlac Hill

just outside Hastings, to face William of Normandy and his invading army. On the 14th October 1066, during the ensuing battle, Harold was killed and the English defeated. It is likely that all the fighting men of Sussex were at the battle, as the county's thanes were decimated and any that survived had their lands confiscated. William built Battle Abbey

at the site of the battle, and the exact spot where Harold fell was marked by the high altar.

Norman influence was already strong in Sussex before the Conquest: the abbey of Fécamp had interest in the harbours of Hastings

, Rye, Winchelsea and Steyning; while the estate of Bosham

was held by a Norman chaplain to Edward the Confessor

. After the Norman conquest the 387 manors, that had been in Saxon hands, were replaced by just 16 heads of manors.

The 16 people, in charge of the manors, were known as the Tenentes in capite

in other words the chief tenants who held their land directly from the crown. The list includes nine ecclesiasticals although the portion of their landholding is quite small and was virtually no different to that under Edward the Confessor, and it is possible that two of the lords may have been Saxon. This means that 353 of the 387 manors in Sussex would have been wrested from their Saxon owners and given to Norman Lords by William the Conqueror

The county was of great importance to the Normans; Hastings and Pevensey being on the most direct route for Normandy. Because of this the county was divided into five new baronies, called rapes, each with at least one town and a castle. This enabled the ruling group of Normans to control the manorial revenues and thus the greater part of the county's wealth.

William, the Conqueror gave these rapes to five of his most trusted Barons:

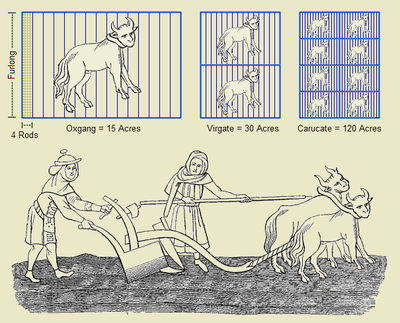

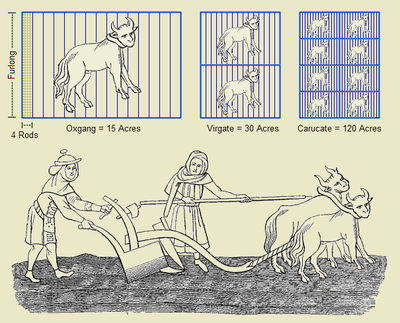

Historically the land holdings of each Saxon lord had been scattered, but now the lords lands were determined by the borders of the rape. The unit of land, known as the hide

, in Sussex had eight instead of the usual four virgate

s,(a virgate being equal to the amount of land two oxen can plough in a season).

The county boundary was long and somewhat indeterminate on the north, owing to the dense forest of Andredsweald. Evidence of this is seen in Domesday Book

by the survey of Worth and Lodsworth under Surrey

, and also by the fact that as late as 1834 the present parishes of north and south Amersham

in Sussex were part of Hampshire

.

At the time of the Domesday Survey, Sussex contained fifty nine hundreds. This eventually increased to sixty-three hundreds and remained unchanged till the 19th century, with thirty eight retaining their original names. The reason why the remainder had their names changed was probably due to the meeting-place of the hundred court being altered. These courts were in private hands in Sussex; either of the Church, or of great barons and local lords.

Independent from the hundreds were the boroughs.

The county court had been held at Lewes and Shoreham until 1086, when it was moved to Chichester. After several changes the act of 1504, during the reign of Henry VII, arranged for it to be held alternately at Lewes and Chichester.

The county court had been held at Lewes and Shoreham until 1086, when it was moved to Chichester. After several changes the act of 1504, during the reign of Henry VII, arranged for it to be held alternately at Lewes and Chichester.

In 1107-9 there was construction of a county gaol, in Chichester Castle

, however the castle was demolished in around 1217 and another gaol built on the same site. That gaol is known to have been used until 1269, when the site of the prison was given to the Greyfriars

to build a priory. In 1242 the counties of Surrey and Sussex were formerly united, and a sharing of prison accommodation resulted almost immediately. Sussex men were imprisoned in Guildford gaol. There were requests for the provision of a county gaol in both Chichester and Lewes at various times to no avail. However the national gaol system became overloaded during the Peasants' Revolt

of 1381, and the earl of Arundel was obliged to imprison people in his castles at Arundel and Lewes. Thus Sussex managed to get a county gaol again at Lewes in 1487 and there it remained until it was moved to Horsham in 1541 for a period.

In the middle of the 16th century the assizes were usually held at Horsham or East Grinstead. In the middle of the 17th century a gaol was built in Horsham, then in 1775 a new gaol was built to replace it. In 1788 an additional gaol was built at Petworth, known as the Petworth House of Correction. There were further Houses of Correction built at Lewes and Battle.

It is believed that the last case of someone being executed by being pressed to death (peine forte et dure), in the country, was carried out in 1735 at Horsham. At the assizes a man who pretended to be dumb and lame, was indicted for murder and robbery. When he was brought to the bar, he would not speak or plead. Witnesses told the court, that they had heard him speak so he was taken back to Horsham gaol. As he would not plead they laid 100 pounds (45.4 kg) weight on him, then as he still would not plead, they added 100 pounds (45.4 kg) more, and a further 100 pounds (45.4 kg) making a total of 300 pounds (136.1 kg) weight, still he would not speak; so 50 pounds (22.7 kg) more was added, when he was nearly dead, the executioner, who weighed about 16 stone or 17 stone, laid down upon the board which was over him, and killed him in an instant.

In 1824 there were 109 prisoners in Horsham Gaol, 233 in Petworth House of Correction, 591 in Lewes House of Correction and 91 in Battle House of Correction. The last public hanging in Sussex was at Horsham in 1844, a year before the gaol finally closed.

The sheriff

's function was to be responsible for the civil justice within the county. Surrey and Sussex shared one sheriff until 1567 when the function was split. Then in 1571 the two counties again shared one sheriff, finally each county was given their own sheriff in 1636. The office of High Sheriff for Sussex then continued until 1974 when it was ended by the local government re-organisation that split Sussex into the two counties of East and West Sussex.

During time of internal unrest or foreign invasions it was usual for the monarch to appoint a lieutenant of the county. The policy of appointing temporary lieutenants continued till the reign of Henry VIII, when Lords Lieutenant were introduced as standing representatives of the crown. The first Lord Lieutenant of the County of Sussex was Sir Richard Sackville

in 1550, the Lord Lieutenant was usually also the custos rotulorum

of the county and Sackville had been given that the year before. The main duties of the Lords Lieutenant was to oversee the military in the county; in Sussex this was the Militia and the Sussex Yeomanry.

As with the Sheriff, the post of Lord Lieutenant of Sussex was ended, in 1974, by the local government re-organisation. There are now separate Sheriffs and Lords Lieutenant for East and West Sussex and the modern day role is largely ceremonial.

Private jurisdictions, both ecclesiastical and lay, played a large part in the county. The chief ecclesiastical franchises were those of the Archbishop of Canterbury, the bishop of Chichester

and also that of Battle Abbey which was founded by William the Conqueror. The main lay francises were those of the Cinque Ports

and the Honour of Pevensey. The Cinque Ports were a group of coastal towns in Kent and Sussex that were given ancient rights and privileges. The main rights were the exemption of taxes and duties and the right to enforce the laws in their juristriction. In return for these privileges they were duty bound to provide ships and men in the time of war for the crown. Traditionally when a collection of lands owned by the Crown is held in tenancy then the tenant is known as the tenant-in-chief and the lands held in such a way was called an honour. The Honour of Pevensey was a collection of estates in Sussex. The Honour of Pevensey was also known as the Lordship of Pevensey Castle or the Honour of The Eagle after the lords of L'Aigle who invariably were the tenant-in-chief. The name L'Aigle (French for eagle) supposedly being derived from a town in Normandy that was named after an eagle that had built its nest in the area.

There have been finds across Europe that suggest that people believed in some sort of afterlife, but whether this represented a religion is not certain. The number of Palaeolithic graves found across Europe has been small and all those in the British region show signs of having been buried in a ritual way.

The Neolithic people of Sussex built causewayed enclosure

s, including those at Whitehawk Camp, Combe Hill

and The Trundle

.Hutton. Pagan Religions. pp. 44-51. There is an hypothesis that there was a ritual element in the construction of these sites, possibly to consecrate the enclosure. Important burials were in long mounds, known as barrows

and several have been found in Sussex, they contained cremated remains in pottery vessels. One of the better known long barrows in Sussex is that of Solomon’s or Baverse’s (Bevis’s) Thumb near Compton, it measures 150 feet (45.7 m) in length by 20 feet (6.1 m) wide.

The general way of life in the Bronze Age in Sussex was not too different to that of the Neolithic and this way of life continued for about one thousand years, until the arrival of the Celts from the south east.

Formal cemeteries and ritual centres have been found at Westhampnett and Lancing Down dating from the late Iron Age.

. There is not much known about the ancient Celtic religion and a lot of what we do know is based on the writings of ancient Greek and Roman scholars and archaeology. The Celtic religion was polytheistic

, and consisted of both god

s and goddess

es, some of which were venerated only in a small, local area, but others whose worship had a wider geographical distribution. Julius Caesar observed that some of the Celtic gods were similar to that of the Roman gods.

The first written account of Christianity in Britain comes from the early Christian Berber

author, Tertullian

, writing in the third century, who said that "Christianity could even be found in Britain." Emperor Constantine

(AD 306-337), granted official tolerance to Christianity with the Edict of Milan

in AD 313. Then, in the reign of Emperor Theodosius "the Great"

(AD 378-395), Christianity was made the official religion of the Roman Empire

.

When Roman rule eventually ceased, Christianity was probably confined to urban communities.

, the exiled Bishop of York, landed at Selsey and is credited with evangilising the locals and founding the church in Sussex, and accordng to Bede

, it was the last area of the country to be converted.Bede.HE.IV.13

of 1075 decreed that sees should be centred in cities rather than vill

s.

Bishop Ralph Luffa

is credited with the foundation of the current Chichester Cathedral

.

The original structure that had been built by Stigand was largely destroyed by fire in 1114.

The archdeacon

ries of Chichester and Lewes were created in the 12th century under Ralph Luffa.

01.jpg)

Like the rest of the country the Church of Englands split with Rome during the reign of Henry VIII

, was felt in Sussex. In 1535, the vicar-general Sir Thomas Cromwell visited the monasteries in the county and the following year an act was passed that decreed the dissolution of most of them. Sussex did not do too badly compared to the rest of the country, as it only had one person in 500, who was a member of a religious order, compared to the national average of one in 256.

In 1538 there was a royal order for the demolition of the shrine of Saint Richard, in Chichester Cathedral. Thomas Cromwell saying that there was a certain kind of idolatry about the shrine.

Richard Sampson

, the Bishop of Chichester incurred the displeasure of Cromwell and ended up imprisoned in the Tower of London

at the end of 1539. Sampson was released, after the fall from favour and execution of Cromwell in 1540. Sampson then continued at the see of Chichester for a further two years. Sampson was succeeded as Bishop of Chichester by George Day

. Day opposed the changes, and incurred the displeasure of the royal commissioners who promptly suspended him as Bishop and allowed him only preach in his cathedral church.

Henry VIII died in 1547, his son Edward VI

continued on the path that his father had set. However his reign was only short-lived as he died after only six years.

The bishops of Chichester had not been for the Reformation until the appointment of John Scory

, to the episcopate, who replaced Day in 1552. During Henry VIII's reign two of the canons of Chichester cathedral had been executed for their opposition to the Reformation and during his sons Edward VI reign George Day ultimately had been imprisoned for his opposition to the reforms.

There had been twenty years of religious reform, when the catholic, Mary Tudor

succeeded to the throne of England in 1553. Mary expected her clergy to be unmarried, so Bishop Scory thought it prudent to retire as he was a married man, and George Day was released and restored to the see of Chichester.

Marys persecution of Protestants earned her the nickname Bloody Mary. The national figure for those Protestants burnt at the stake, during her reign, was around 288 and included 41 in Sussex. Most of the executions in Sussex were at Lewes. Of the total of 41 burnings, 36 can be identified to have come from specific parishes and the place of execution is known for 27 of them; this is because the details of the executions were recorded in the Book of Martyrs by John Foxe

, published in 1563. There are Bonfire Societies

in Sussex that still remember the 17 Protestant martyrs that burned in Lewes High Street, and in Lewes itself they have a procession of martyrs crosses during the bonfire night celebration.

In 1558 Mary died and her Protestant sister Elizabeth I

replaced her.

Elizabeth re-established the break with Rome when she passed the 1559 Acts of Supremacy and Uniformity, the clergy were expected to take statutory oaths and those that did not were deprived of their living. In the county nearly half the cathedral and about 40% of the parish clergy had to be replaced, although some of the vacancies were due to ill health or death.

There were no battles of national significance, in Sussex, during the 1642–1651 English civil war, however there were small sieges at Chichester and Arundel. The west of the county was generally for the king although Chichester was for parliament and the east of the county, with some exceptions, was also for parliament. A few churches were damaged particularly in the Arundel area. Also, after the surrender of Chichester, the Cathedral was sacked by Sir William Wallers parliamentary troops. Bruno Ryves

, Dean of Chichester Cathedral said of the troops that they deface and mangle (the monuments) with their swords as high as they could reach.

About a quarter of the incumbents were forced from their parishes and replaced with Puritans. Many people turned away from the traditional churches and in 1655 George Fox

founded the Society of Friends at Horsham.

The Parliamentary

history of the county began in the 13th century. In 1290, the first year for which a return of knights of the shire is available, Henry Hussey and William de Etchingham were elected.

In 1801 the Members of Parliament(MPs) for the counties on the south coast of England were elected to a third of all the seats in parliament, although they represented only about 15% of the nations population. The way that the countrys electoral system worked had changed little since the first parliament in 1295. The counties each returned two MPs and each borough designated by Royal charter also returned two MPs. This produced the situation where some of the towns of the north that had grown large during the industrial revolution

had no representation whereas smaller towns in the south, that had been important in medieval times, were still able to have two MPs.

Although there had been various proposals to reform the system from 1770, it was not till 1830 when a series of factors saw the Reform Act 1832

introduced. The larger industrial towns of the north were enfranchised for the first time and smaller English boroughs (known as Rotten Boroughs) were disenfranchised,including Bramber

, East Grinstead

, Seaford

, Steyning

and Winchelsea

in Sussex. The Representation of the People Act 1884

and the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885

(together known as the Third Reform Act) were responsible for redistributing 160 seats and extending suffrage.

After the Reform Act of 1832 Sussex was divided into the eastern division and the western division and two representatives were elected for each division. In June 1832 the Honorable C.C. Cavendish and H.B.Curteis Esquire were elected in the eastern division and the Earl of Surrey and Lord John George Lennox were elected for the western division. There was a total of 3478 votes cast in the eastern division and 2365 votes in the western division.

Before the 1832 reform two members each had been returned by Arundel

, Chichester, Hastings, Horsham

, Lewes, Midhurst

, New Shoreham (with the rape of Bramber) and Rye

. Arundel, Horsham, Midhurst and Rye were each deprived of a member in 1832, Chichester and Lewes in 1867, and Hastings in 1885. Arundel was disfranchised in 1868, and Chichester, Horsham, Midhurst, New Shoreham and Rye in 1885.

Under the new system the constituencies were based on unit numbers rather than historic towns. The reforms of the 19th century made the electoral system more representative, but it was not till 1928 there was universal suffrage.

In 1264 there was a civil war in England, between the forces of a group of barons, led by Simon de Montfort

, against the royalist forces, led by Prince Edward

, in the name of Henry III

, known as the Second Barons' War

. On the 12 May 1264, Simon de Montfort forces occupied a hill known as 'Offam Hill' outside Lewes, the royalist forces tried to storm the hill but ultimately were defeated by the barons'. The actual site, of what became known as the Battle of Lewes

, is somewhere between the town and the hill, the battle was bitterly fought for over five hours. In the 19th century, when a railway was being constructed in the area of the battle, navvies discovered a mass grave with around 2000 bodies in it.

During the Middle Ages the Wealden peasants rose up in revolt on two ocaasions, the Peasants' Revolt in 1381 under Watt Tyler, and in Jack Cade

's rebellion of 1450. Cade's rebellion was not just supported by the peasant class, many gentlemen, craftspeople and artisans also the Abbot of Battle and Prior of Lewes flocked to his standard in revolt against the corrupt government of Henry VI

. Jack Cade was fatally wounded in a skirmish at Heathfield

in 1450.

At the time of the English Civil War the counties sympathies were divided , Arundel supported the king, Chichester, Lewes and the Cinque Ports were for parliament. Most of the west of the county were for the king and included a powerful group with the bishop of Chichester and Sir Edward Ford, sheriff of Sussex, in their number. Exceptionally, Chichester was for parliament largely due to an influential brewer named William Cawley

. However the group of royalists led by Edward Ford managed to get a force together to capture Chichester, in 1642, for the king and imprisoned 200 parliamentarians.

The roundhead

army under Sir William Waller besieged Arundel and after its fall marched on Chichester and restored it to parliament. A military governor, Algernon Sidney was appointed in 1645. Chichester was then demilitarised, in 1647-1648 and remained in parliaments hands for the rest of the civil war. The brewer William Cawley became a MP for Chichester in 1647 and was one of the signatories on King Charles I

death warrant.

At the beginning of the 19th century agricultural labourers conditions took a turn for the worse with an increasing amount of them becoming unemployed, those in work faced their wages being forced down. Conditions became so bad that it was even reported to the House of Lords

At the beginning of the 19th century agricultural labourers conditions took a turn for the worse with an increasing amount of them becoming unemployed, those in work faced their wages being forced down. Conditions became so bad that it was even reported to the House of Lords

in 1830 that four harvest labourers (seasonal workers) had been found dead of starvation. The deteriorating conditions of work for the agricultural labourer eventually triggered off riots in Kent during the summer of 1830. Similar action spread across the county border to Sussex where the riots lasted for several weeks, although the unrest continued until 1832 and were known as the Swing Riots

.

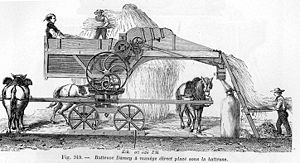

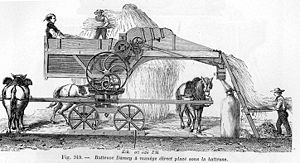

The Swing riots were accompanied by action against local farmers and land owners. Typically, what would happen is a threatening letter would be sent to a local farmer or leader demanding that automated equipment such as threshing machine

s should be withdrawn from service, wages should be increased and there would be a threat of consequences if this did not happen, the letter would be signed by a mythical Captain Swing

. This would be followed up by the destruction of farm equipment and occasionally arson.

Eventually the army was mobilised to contain the situation in the eastern part of the county, whereas in the west the Duke of Richmond

took action against the protesters by the use of the yeomanry and special constables. The Sussex Yeomanry

were subsequently disparagingly nicknamed the workhouse guards. The protesters faced charges of arson, robbery, riot, machine breaking and assault. Those convicted faced imprisonment, transportation

or ultimately execution.

The grievances continued encouraging a wider demand for political reform, culminating in the introduction of the Reform Act 1832.

One of the main grievances of the Swing protesters had been what they saw as inadequate Poor Law

benefits, Sussex had the highest poor-relief costs during the agricultural depression of 1815 to the 1830s and its workhouses were full. The general unrest, particularly about the state of the workhouses, was instrumental in the introduction of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834

.

and Napoleonic wars

(1793–1815), a European coalition was formed, that included Britain, with the intention of crushing the newly founded French Republic, so defensive measures were taken in Sussex.

In 1793 at Brighton

In 1793 at Brighton

two batteries

were built on the towns east and west cliffs (replacing older installations). The Sussex Yeomanry was founded in 1794, and numbers of gentlemen and yeomanry volunteered to join the part time cavalry regiment to serve in case of invasion by Bonaparte

. Between 1805 and 1808 a series of defensive towers known as Martello tower

s were erected along the Sussex and Kent coasts, and later on the east coast. The Admiralty

commissioned a visual signalling system to allow communications between ships and the shore and from there to the Admiralty in London; Sussex had a total of 16 signalling stations on its coast. A central fort and supply base for the towers, the Eastbourne Redoubt

at Eastbourne

was constructed between 1804-1810. It is now home to the Royal Sussex Regiment Museum. In the 1860s, possible wars

with France prompted more defence building, including the fort at Newhaven

.

At the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, the landowners of the county employed their local leadership roles to recruit volunteers for the nations forces. The owner of Herstmonceux Castle, a Claude Lowther

, recruited enough men for three Southdown Battalians who were known as Lowthers Lambs. The Royal Sussex Regiment fielded a total of 23 battalions in the Great War. After the war, St Georges Chapel, in Chichester Cathedral, was restored and furnished as a memorial to the fallen of the Royal Sussex Regiment. Nearly 7,000 of the regiment lost their lives, in the First World War, and their names are recorded on the panels that are attached to the walls of the chapel.

With the declaration of the Second World War, on 3 September 1939, Sussex found itself part of the country's frontline with its airfields playing a key role in the Battle of Britain

and with its towns being some of the most frequently bombed.

The first line of defence was the coastal crust consisting of pillboxes, machine-gun posts, trenches, rifle posts, anti-tank obstacles plus scaffolding, mines and barbed wire. As the Sussex regiments were serving overseas for large parts of the war, the defence of the county was undertaken by units of the Home Guard with help between 1941 to early 1944 from the First Canadian Army

.

During the war every part of Sussex was affected. Army camps of both the tented and also the more permanent variety sprang up everywhere. Sussex played host to many servicemen and women, including the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division

, the 4th Armoured Brigade, the 30th US Division, the 27th Armoured Brigade and the 15th Scottish Division. Besides airmen and women from the British Commonwealth, fighter squadrons from the Free French

, Free Czechs

, Free Polish

were regularly based at airfields around Sussex.

During the lead up to the D-Day

landings, the people of Sussex were witness to the build up of military personnel and materials, including the assembly of landing crafts and construction of Mulberry harbour

s off the countys coast. Five new airfields were built to provide additional support for the D-Day landings, four near Chichester and one near Billingshurst.

A legacy of the D-Day landings are the sections of Mulberry harbour that lay broken and abandoned on the sea floor 2 miles off the coast, of Selsey Bill, having missed the invasion.

Iron Age wrought iron was produced by means of a bloomery

Iron Age wrought iron was produced by means of a bloomery

followed by reheating and hammering. With the type that was common in Sussex a round shallow hearth was dug out, clay hard-packed to line it, then layers of hammered ore and charcoal were put down and the whole lot covered by a clay beehive structure, with holes at the side for the insertion of foot or hand bellows. The material inside the beehive furnace was then ignited and it took two to three days for the process to complete, leaving semi-molten lumps of iron, known as blooms on the hearth. The output from these types of furnace, was very small as everything had to cool down before the iron could be retrieved. The iron so retrieved could then be worked by using the heat and beat technique to form wrought iron implements such as weapons or tools. Around a dozen pre-Roman sites have been found in eastern Sussex, the westernmost being at Crawley.

The Romans made full use of this resource, continuing and intensifying native methods, and iron slag was widely used as paving material on the Roman roads of the area. The Roman iron industry was mainly in East Sussex with the largest sites in the Hastings area. The industry is thought to have been organised by the Classis Britannica

, the Roman navy.

Little evidence has been found of iron production after the Romans left until the ninth century when a primitive bloomery, of a continental style, was built at Millbrook on Ashdown Forest

, with a small hearth for reheating the blooms nearby. Production based on bloomeries then continued till the end of the 15th century when a new technique was imported from northern France that allowed the production of cast iron

. A permanent blast furnace was constructed; into the furnace chamber was inserted a pipe fed by bellows that could be operated by a wheel; the wheel was rotated by the use of water power, oxen or horses. Pairs of bellows continuously forced air into the furnace chamber, producing higher temperatures such that the iron completely melted and could be could be run off from the base of the chamber and into moulds. This allowed a continuous process that usually ran during the winter and spring seasons, ceasing when water supplies to drive the bellows dwindled in the summer.

Henry VIII, urgently needed cannon for his new coastal forts, but casting these in the traditional bronze would have been very expensive. Previously iron cannons had been made by building up bands of iron bound together with iron hoops; such cannons had been used at Bannockburn

in 1314. There had also been some cast cannons made in the Weald but with separate barrels and breeches.

In Buxted the local vicar, the Reverend William Levett

, was also a gun-founder, he recruited a Ralf Hogge

to help him produce cannon and in 1543 his employee cast an iron muzzle-loading cannon. It was cast in one piece, using a pattern based on the latest bronze ordnance. The navy, complained that the new guns were too heavy but bronze was ten times more costly, so in fortifications and for arming merchant ships iron guns were preferred. Gradually, owing to their toughness and validiti, an important export trade in wealden guns built up and they remained dominant internationally until displaced by Swedish guns around 1620. Both men made a lot of money out of the trade, and Hogge built a house on the road to Levetts church. Hogge put a rebus, on his house, with a hog on it as a pun for his name.

The large supply of wood in the county made it a favourable centre for the industry, all smelting

being done with charcoal

till the middle of the 18th century.

then to Alfold, Ewhurst, Billinghurst and Lurgashall. Many of the artisans in the industry were immigrants from France and Germany. The manufacturing process used timber for fuel, sand and potash(which served as flux).

Glass production in the English midlands using coal for the smelting process, plus opposition to the use of timber in Sussex, led to the collapse of the Sussex glass making industry in 1612.

The first real description of the forest that, at the time, covered the Sussex Weald was provided by, the annal commissioned in the 9th century by King Alfred, the Anglo Saxon Chronicle, which says that the forest was 120 miles wide and 30 miles deep (although probaby closer to 90 miles wide). The forest was so dense that even the Domesday Book did not record some of its settlements.

The Weald was not the only area of Sussex that was forested in Saxon times, for example at the western end of Sussex is the Manhood Peninsula, which these days is largely deforested, however the name is probably derived from the Old English maene-wudu meaning "men's wood" or "common wood" indicating that it was once woodland.

During and before the reign of Henry VIII, England imported a lot of the wood for its naval ships from the Hanseatic league

. Henry wanted to source the materials for his army and navy domestically. So it was largely the forests of Sussex that met this demand for wood, Sussex oak

being considered the finest shipbuilding

timber. Vast amounts of wood were consumed to build ships and produce charcoal for the foundry furnaces. Faced with diminishing stocks of wood due to the large consumption from the ship, iron and glass making industries, parliament introduced bills to manage the stocks more efficiently however the parliamentary bills were never past, with the result that the countys forests were decimated. The poet Michael Drayton

in his poem Poly-Olbion

, published in the early 17th century, made the trees denounce the iron trade:

However despite parliaments efforts the forests, of Sussex, continued to be consumed until 1760, when an Abraham Darby

discovered how to replace charcoal with coke in his blast furnaces, this resulted in production being moved to the parts of the country, nearer the coal mines. By that time the forests had been completely devastated and the roads ruined by the transport of ore and pig iron.

The High Weald still has about 35905 hectares (138.6 sq mi) of woodland, including areas of ancient woodland

equivalent to about 7% of the stock for all England. When the Anglo Saxon Chronicle was compiled in the 9th century there was thought to be about 2700 square miles (699,296.8 ha) of forest in the Sussex Weald.

commanded that his Chancellor should sit on the woolsack in council as a symbol of the pre-eminence of the wool trade at the time. In 1341 the greatest wool production in Sussex was in the eastern part of the county, and in the west of the county, the port of Chichester was extended along the whole coast from Southampton to Seaford for the collection of customs on wool. Also Chichester, despite its geographical disadvantages ranked as the seventh port in the kingdom and was one of the wool ports named in the Statute of the Staple

of 1353.

In the early 15th century most production of wool was within 15 miles of Lewes.

In the 16th century weavers were to be found in nearly every parish as were fullers

and dyers. Chichester was an early centre of the weaving

of cloth and also for the spinning of linen.

In 1566 an act that prohibited the export of "unwrought or unfinished cloths" led to the demise of the industry in Sussex, and by the beginning of the 18th century it had virtually collapsed; Daniel Defoe

commented, in 1724, that the "..whole counties of Kent, Sussex, Surrey and Hampshire, are not employ'd in any considerable Woolen Manufacture;".

Other turnpike acts followed with the roads being built and maintained by local trusts and parishes. The majority of the roads were maintained by a toll levied on each passenger (who usually would have been transported by stage coach), a few roads were still maintained by the parishes with no toll levied. There were 152 Acts of Parliament by the mid 19th century, for the formation, renewel and amendment of the turnpikes in the county. A report on the county's turnpike trusts, published in 1857, said that there were fifty-one trusts covering 640 miles of road, with 238 toll gates or bars, giving an average of one toll gate every 2.5 miles.

The last turnpike to be constructed in the county was between Cripps Corner and Hawkhurst

in 1841.

The system of turnpikes, coaches and coaching inns collapsed in the face of competition from the railways. By 1870 most of the county's Turnpike Trusts were wound up putting hundreds of coachmen and coachbuilders out of business. The conditions of the county's roads then deteriorated until the creation of the new county council in 1889, who assumed responsibility for the maintenance of the county's roads.

At the beginning of the 20th century, nearly all the first class roads had been turnpikes in 1850. During the course of the 20th century, the car and the lorry challenged the supremacy of the railways.

The two counties of East and West Sussex only have a total of 12 kilometre of motorway and relatively small amounts of dual carriageway. Two of the "A" roads that traverse Sussex from east to west are the A27

and the A259

, a combination of the these two roads provide the major route across Sussex, the route is only dual-carriageway for part of its length; both roads run parallel to the Sussex coast. The main north south road, that connects the coast to the London orbital M25

, is the M23

/ A23

. According to the Highways Agency

the removal of most of the east/ west bottlenecks, for example improvements to the Chichester by-pass, will not occur for some time to come.

s that were constructed in Sussex, can be described as navigations, in that their purpose was to make the lower reaches of the county's rivers navigable. The rivers had suffered from centuries of neglect, which had made navigation, even for small craft, difficult.

Examples of navigations in Sussex are:

Eventually, true canals were also built, examples being:

When the railways arrived, in Sussex, they provided an alternative to the canals and waterways, the canal companies revenue quickly dropped resulting in most of them closing for business by the beginning of World War I.

, a Cornish engineer, built the first steam locomotive for a railway. His seven-tonne locomotive hauled 10 tonnes of iron and 70 passengers on a 9 miles (14.5 km) journey from the Penydarren Ironworks near Merthyr Tydfil to the Glamorganshire Canal at Abercynon, reaching a top speed of almost 5 miles per hour (8 km/h).

George Stephenson

built the engine Locomotion

for the Stockton and Darlington railway

, which was opened in 1825 for both passenger and goods traffic; Locomotion pulled thirty-six wagons containing coal, grain and 500 paassengers a distance of 9 miles at a top speed of 15 miles per hour (24.1 km/h).

The Manchester to Liverpool railway of 1830 was the first to convey passengers and goods entirely by mechanical traction. Stephenson's Rocket

The Manchester to Liverpool railway of 1830 was the first to convey passengers and goods entirely by mechanical traction. Stephenson's Rocket

, which won the famous Rainhill trials in 1829, was the first steam locomotive designed to pull passenger traffic quickly.

Brightons proximity to London made it an ideal place to provide short holidays for Londoners. In the 1830s, during the summer, the London Brighton road would see around 40 coaches a day plus a number of private carriages taking visitors to the coast. The road was in a poor condition so proposals to build a railway was suggested as early as 1806. However, it was not till 1823 that a serious scheme was mooted. There followed years of discussion and argument with various groups proposing different routes, then finally in 1837 the London and Brighton Railway Bill with branches to Shoreham and Newhaven received Royal assent. In 1838 the directors of the London and Brighton Railway Company (L&BR) stated that the railroad would be different to the rest of the country in that it would be a passenger only railway.

In the 18th century Brighton had been a town in terminal decline until two things happened:

These two events increased the amount of visitors to the town, however in 1841 when the L&BR opened for business, of Brighton's 8,137 stock of houses, 1,095 stood empty. But within 40 years of the railways arrival Brighton's resident population had doubled.

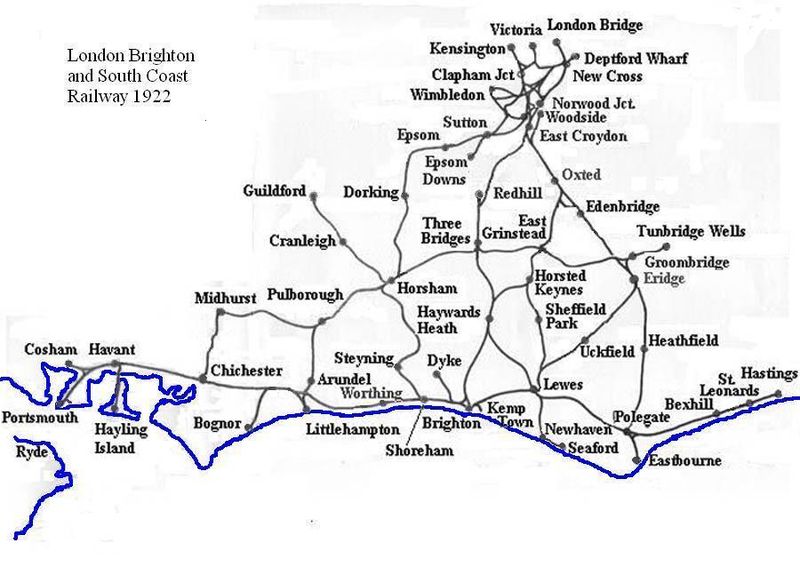

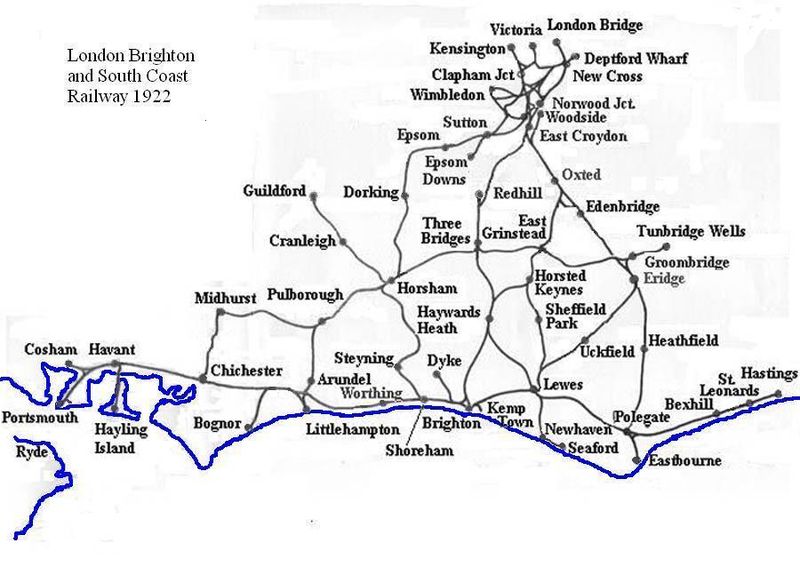

After the opening of the Brighton line, within a few years branches were made to Chichester on the west and Hastings and Eastbourne to the east. In 1846 the L&BR merged with the London and Croydon Railway

After the opening of the Brighton line, within a few years branches were made to Chichester on the west and Hastings and Eastbourne to the east. In 1846 the L&BR merged with the London and Croydon Railway

(L&CR), the Brighton and Chichester Railway

and the Brighton, Lewes and Hastings Railway to form the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway

(LB&SCR). The LB&SCR continued as an independent entity until the Railways Act 1921

, which saw the merger of various rail companies, in the south and south east, into the Southern Railway Company

(SR); formed on 1 January 1923. Two railway companies in the county, that were not absorbed by the SR, was Volk's Electric Railway

the world's first electric railway, that runs along the front at Brighton and opened in 1883, and the West Sussex Railway

, a light railway between Chichester and Selsey, opened in 1897.

SR was the smallest of four groups that were brought together by the Railways Act 1921. The LB&SCR had partly electrified their network before World War I, however that had been an overhead system

, SR decided to electrify their network using the third rail

DC system.

During World War II the SR was heavily involved with transporting armed services traffic and was bombed on many occasions. After the war SR was nationalised in 1948, and became the Southern Region of British Railways.

Following John Major

's victory in the 1992 General Election

, the conservative government

published a white paper

, indicating their intention to privatise the railways.

The government went ahead with their plans and franchises were awarded to train operating companies

(TOC).

Currently the main TOCs in Sussex are Southern Railway

, for the southcoast and services to Victoria and London Bridge

; First Capital Connect

for services from Brighton to Bedford

via London and the London and South Eastern Railway

for services between eastern Sussex and London.

, opened in 1579, and at Shoreham

opened in 1760. Other ports such as Pevensey, Winchelsea, and Rye now lie stranded from the current coastline. Other harbours that existed such as Fishbourne

, Steyning, Old Shoreham, Meeching and Bulverhythe are long since silted up and have been built over.

South East England

South East England is one of the nine official regions of England, designated in 1994 and adopted for statistical purposes in 1999. It consists of Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, East Sussex, Hampshire, Isle of Wight, Kent, Oxfordshire, Surrey and West Sussex...

of England

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west; the Irish Sea is to the north west, the Celtic Sea to the south west, with the North Sea to the east and the English Channel to the south separating it from continental...

. The foundation of the Kingdom of Sussex is recorded by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great...

for the year AD 477, saying that Ælle arrived at a place called Cymenshore

Cymenshore

Cymenshore is the place in Southern England where according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Ælle of Sussex landed in 477 AD and battled the Welsh with his three sons Cymen, Wlencing and Cissa.-Historical context:The account of Ælle and his three sons landing at Cymenshore, in the Anglo Saxon...

in three ships with his three sons and killed or put to flight the local inhabitants.

The foundation story is regarded as somewhat of a myth by most historians, although the archaeology suggests that Saxons did start to settle in the area in the late 5th century. The Kingdom of Sussex became the county of Sussex; then after the coming of Christianity; the see originally founded in Selsey, was moved to Chichester in the 11th century. The See of Chichester was coterminous with the county borders. In the 12th century the see was split into two archdeaconries centred at Chichester and Lewes.

After the Reform Act of 1832 Sussex was divided into the eastern division and the western division, these divisions were coterminous with the two archdeaconries of Chichester and Lewes. Sussex ceased to exist as a political entity in 1974, when, under an act of parliament, its eastern division became the county of East Sussex and the western division the county of West Sussex. There are several organisations that still operate within the ancient borders of Sussex although it is now the two counties of East and West Sussex, some examples being the Diocese of Chichester

Diocese of Chichester

The Diocese of Chichester is a Church of England diocese based in Chichester, covering Sussex. It was created in 1075 to replace the old Diocese of Selsey, which was based at Selsey Abbey from 681. The cathedral is Chichester Cathedral and the bishop is the Bishop of Chichester...

, Sussex Police

Sussex Police

Sussex Police is the territorial police force responsible for policing East Sussex, West Sussex and City of Brighton and Hove in southern England. Its head office is in Lewes, Lewes District, East Sussex.-History:...

and Sussex Archaeological Society

Sussex Archaeological Society

The Sussex Archaeological Society, founded in 1846, is the largest county-based archaeological society in the UK. Its headquarters are in Lewes, Sussex...

.

Although the name Sussex is derived from the Saxon period between AD 477 to 1066, the history of human habitation in Sussex goes back to the Old Stone (Paleolithic

Lower Paleolithic

The Lower Paleolithic is the earliest subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. It spans the time from around 2.5 million years ago when the first evidence of craft and use of stone tools by hominids appears in the current archaeological record, until around 300,000 years ago, spanning the...

) Age. Sussex has been occupied since those times and although it has been an industrious county it has succumbed to various persecutions, wars, invasions, political unrest and migrations throughout its long history.

Stone Age

In 1993 a human-like tibia was found at Boxgrove near Chichester. Then in 1996 further hominid remains were found: two incisor teeth from a single individual recovered from the lower freshwater deposits at the site. The remains came to be known as "Boxgrove man" and are thought to be a species known as Homo HeidelbergensisHomo heidelbergensis

Homo heidelbergensis is an extinct species of the genus Homo which may be the direct ancestor of both Homo neanderthalensis in Europe and Homo sapiens. The best evidence found for these hominins date between 600,000 and 400,000 years ago. H...

.

Boxgrove man apparently lived in a temperate stage immediately prior to the Anglian glaciation

Anglian glaciation

The Anglian Stage is the name for a middle Pleistocene stage used in the British Isles. It precedes the Hoxnian Stage and follows the Cromerian Stage in the British Isles. The Anglian Stage is equivalent to the Elsterian Stage of northern Continental Europe, the Mindel Stage in the Alps and Marine...

, in the Lower Paleolithic period between 524,000 and 478,000 years ago.

In 1900 Upper Palaeolithic flintwork was found at a site in the Beedings. Then in 2007–08 Early Upper Palaeolithic archaeology was found at the same site. The archaeology at the Beedings spans a crucial cultural transition in the European Palaeolithic and therefore provides an important new dataset for the analysis of late Neanderthal groups in northern Europe and their replacement by modern human populations.

It is believed that during the Mesolithic

Mesolithic

The Mesolithic is an archaeological concept used to refer to certain groups of archaeological cultures defined as falling between the Paleolithic and the Neolithic....

Age nomadic hunters arrived in Sussex from Europe. At the time (8000 BC), Britain was still connected to the continent, however the ice sheets over northern Europe were melting rapidly and causing the gradual rising of sea levels, which eventually led to the forming of the Straits of Dover, effectively cutting off the Mesolithic people of Sussex from the continent. There have been archaeological finds from these people, mostly in the central wealden

Weald

The Weald is the name given to an area in South East England situated between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs. It should be regarded as three separate parts: the sandstone "High Weald" in the centre; the clay "Low Weald" periphery; and the Greensand Ridge which...

area to the north of the Downs. Large amounts of knives, scrapers, arrow heads and other tools have been found.

Close to the River Ouse

River Ouse, Sussex

The River Ouse is a river in the counties of West and East Sussex in England.-Course:The river rises near Lower Beeding and runs eastwards into East Sussex, meandering narrowly and turning slowly southward...

near Sharpsbridge, a polished axe, polished axe fragments, a chisel and other examples of Neolithic

Neolithic

The Neolithic Age, Era, or Period, or New Stone Age, was a period in the development of human technology, beginning about 9500 BC in some parts of the Middle East, and later in other parts of the world. It is traditionally considered as the last part of the Stone Age...

flintwork have been found. The fact that these implements were found close to the River Ouse suggests that some land clearance may have taken place in the river valley during the Neolithic period.

From about 4300 BC to about 3400 BC the mining of flint for use locally and also for wider trade was a major activity in Neolithic Sussex. There was also a Neolithic pottery industry, with styles of pot reminiscent of finds elsewhere, such as Hembury and Grimston/ Lyle Hill.

Bronze Age

The transition from the late neolithic to the Early Bronze AgeBronze Age Britain

Bronze Age Britain refers to the period of British history that spanned from c. 2,500 until c. 800 BC. Lasting for approximately 1700 years, it was preceded by the era of Neolithic Britain and was in turn followed by the era of Iron Age Britain...

in Sussex is marked by the appearance of Beaker pottery. There have been several finds including some in Beaker settlements, a significant settlement was one discovered near Beachy Head

Beachy Head

Beachy Head is a chalk headland on the south coast of England, close to the town of Eastbourne in the county of East Sussex, immediately east of the Seven Sisters. The cliff there is the highest chalk sea cliff in Britain, rising to 162 m above sea level. The peak allows views of the south...

, in 1909. The site was partially excavated in 1970 and the finds included pottery,flints, post settings, shallow pits and a midden

Midden

A midden, is an old dump for domestic waste which may consist of animal bone, human excrement, botanical material, vermin, shells, sherds, lithics , and other artifacts and ecofacts associated with past human occupation...

. The presence of Beaker pottery provides the first evidence of the migration of people from northern Europe since the early Neolithic period. Although some pre-historians now doubt the existence of the Beaker people as migrants and suggest that it was possible that the Beaker culture may have just been a new development of the local neolithic people.

From the Bronze Age

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

(about 1400-1100BC) settlements and burial sites have left their mark throughout Sussex.

Iron Age

There are over fifty Iron Age sites that are known throughout the Sussex Downs. Probably the best known are the hill-forts such asCissbury Ring

Cissbury Ring

Cissbury Ring is a hill fort on the South Downs, in the borough of Worthing, and about from its town centre, in the English county of West Sussex.-Hill fort:...

. A small number of agricultural settlements, or farmsteads, have been excavated on a large scale. The results of these excavations have provided a picture of the economy, based on mixed farming. Artefacts such as iron ploughshares and sickles were excavated.

The presence of animal bones, particularly cattle and sheep, attests to the pastoral element to their economy.

Various items have been found that indicate that they used to spin and weave the wool they produced.

The Sussex Iron Age dweller supplemented their diet with marine shellfish, the remains of which have been found on

several sites.

Towards the end of the Iron Age in 75BC, people from the Atrebates

Atrebates

The Atrebates were a Belgic tribe of Gaul and Britain before the Roman conquests.- Name of the tribe :Cognate with Old Irish aittrebaid meaning 'inhabitant', Atrebates comes from proto-Celtic *ad-treb-a-t-es, 'inhabitants'. The Celtic root is treb- 'building', 'home' The Atrebates (singular...

one of the tribes of the Belgae

Belgae

The Belgae were a group of tribes living in northern Gaul, on the west bank of the Rhine, in the 3rd century BC, and later also in Britain, and possibly even Ireland...

, a mix of Celtic and German stock, started invading and

occupying southern Britain. This was followed by an invasion by

the Roman army under Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman and a distinguished writer of Latin prose. He played a critical role in the gradual transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire....

that temporarily occupied the south-east in 55BC.

Then soon after the first Roman invasion had ended, the Celtic Regnenses

Regnenses

The Regnenses, Regni or Regini were a British Celtic kingdom and later a civitas of Roman Britain. Their capital was Noviomagus Reginorum, known today as Chichester in modern West Sussex....

tribe under, their leader Commius

Commius

Commius was a historical king of the Belgic nation of the Atrebates, initially in Gaul, then in Britain, in the 1st century BC.-Ally of Caesar:...

occupied the Manhood Peninsula

Manhood Peninsula

The Manhood Peninsula is the southernmost part of Sussex in England. It has the English channel to its south and Chichester to the north.The peninsula is bordered to its west by Chichester Harbour and to its east by Pagham Harbour, its southern headland being Selsey Bill.-Name:The name Manhood has...

.

Tincomarus

Tincomarus

Tincomarus was a king of the Iron Age Belgic tribe of the Atrebates who lived in southern central Britain shortly before the Roman invasion...

and then Cogidubnus followed Commius as rulers of the Regnenses.

At the time of the Roman conquest in AD43 there was an oppidum

Oppidum

Oppidum is a Latin word meaning the main settlement in any administrative area of ancient Rome. The word is derived from the earlier Latin ob-pedum, "enclosed space," possibly from the Proto-Indo-European *pedóm-, "occupied space" or "footprint."Julius Caesar described the larger Celtic Iron Age...

in the southern part of their territory, probably in the Selsey region.

Roman Sussex

After the Roman invasion Cogidubnus was placed or confirmed by the Romans as ruler of the Regnenses and he took the name Tiberius Claudius Cogidubnus and claimed to be ‘'rex magnus Britanniae'’. His name is mentioned on two exceptionally early Roman inscriptions in his capital of Noviomagus ReginorumNoviomagus Reginorum

Noviomagus Reginorum was the Roman town which is today called Chichester, situated in the modern English county of West Sussex. Alternative versions of the name include Noviomagus Regnorum, Regnentium and Regentium..-Development:...

(Chichester).

There are a variety of remains in the county from Roman times, coin hoards and decorated pottery have been found.

There are examples of Roman roads such as:

- Chichester to Silchester WayChichester to Silchester WayThe Chichester to Silchester Way is a Roman Road between Chichester in South-East England, which as Noviomagus was capital of the Regnenses, and Silchester or Calleva Atrebatum, capital of the Atrebates. The road had been entirely lost and forgotten, leaving no Saxon place names as clues to its...

- Chichester to London Stane Street

Also a variety of buildings, the best known being:

- Bignor Roman VillaBignor Roman VillaBignor Roman Villa is a large Roman courtyard villa which has been excavated and put on public display on the Bignor estate in the English county of West Sussex...

- Fishbourne Roman PalaceFishbourne Roman PalaceFishbourne Roman Palace is in the village of Fishbourne in West Sussex. The large palace was built in the 1st century AD, around thirty years after the Roman conquest of Britain on the site of a Roman army supply base established at the Claudian invasion in 43 AD. The rectangular palace surrounded...

The coast of Roman Britain had a series of defensive forts on them, and towards the end of the Roman occupation the coast was subject to raids by Saxons

Saxons

The Saxons were a confederation of Germanic tribes originating on the North German plain. The Saxons earliest known area of settlement is Northern Albingia, an area approximately that of modern Holstein...

. Additional forts

Saxon Shore

Saxon Shore could refer to one of the following:* Saxon Shore, a military command of the Late Roman Empire, encompassing southern Britain and the coasts of northern France...

were built against the Saxon threat, an example in Sussex being Anderitum

Anderitum

Anderitum is a commonly cited spelling of a Saxon Shore Fort actually spelled Anderidos, in the Roman province of Britannia. It is located at in eastern Pevensey in the English county of East Sussex and was later converted into a medieval castle known as Pevensey Castle.-Roman fort:It was built by...

(Pevensey Castle

Pevensey Castle

Pevensey Castle is a medieval castle and former Roman fort at Pevensey in the English county of East Sussex. The site is a Scheduled Monument in the care of English Heritage and is open to visitors.-Roman fort:...

). The coastal defences were supervised by the Count of the Saxon Shore

Count of the Saxon Shore

The Count of the Saxon Shore for Britain was the head of the "Saxon Shore" military command of the later Roman Empire.The post was possibly created during the reign of Constantine I and was probably existent by AD 367 when Nectaridus is elliptically referred to as one by Ammianus...

. There is some suggestion that around the beginning of the fourth century the Roman authorities recruited mercenaries from the German homelands to defend the southern and eastern coasts of Britain. The area they defended was known as the Saxon Shore. It is possible that these mercenaries remained after the departure of the Roman army and merged with the eventual Anglo-Saxon invaders.

Norman Sussex

On Friday 13 October 1066, Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson

Harold Godwinson was the last Anglo-Saxon King of England.It could be argued that Edgar the Atheling, who was proclaimed as king by the witan but never crowned, was really the last Anglo-Saxon king...

and his English army arrived at Senlac Hill

Senlac Hill

Senlac Hill , was the ridge on which Harold Godwinson deployed his army for the Battle of Hastings on October 14, 1066. The high ground the hill offered gave the English a great advantage over the Normans, who made repeated charges up the hill but to no avail. Only when the Normans feigned retreat...

just outside Hastings, to face William of Normandy and his invading army. On the 14th October 1066, during the ensuing battle, Harold was killed and the English defeated. It is likely that all the fighting men of Sussex were at the battle, as the county's thanes were decimated and any that survived had their lands confiscated. William built Battle Abbey

Battle Abbey

Battle Abbey is a partially ruined abbey complex in the small town of Battle in East Sussex, England. The abbey was built on the scene of the Battle of Hastings and dedicated to St...

at the site of the battle, and the exact spot where Harold fell was marked by the high altar.

Norman influence was already strong in Sussex before the Conquest: the abbey of Fécamp had interest in the harbours of Hastings

Hastings

Hastings is a town and borough in the county of East Sussex on the south coast of England. The town is located east of the county town of Lewes and south east of London, and has an estimated population of 86,900....

, Rye, Winchelsea and Steyning; while the estate of Bosham

Bosham

Bosham is a small coastal village and civil parish in the Chichester District of West Sussex, England, about ) west of Chichester on an inlet of Chichester Harbour....

was held by a Norman chaplain to Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor

Edward the Confessor also known as St. Edward the Confessor , son of Æthelred the Unready and Emma of Normandy, was one of the last Anglo-Saxon kings of England and is usually regarded as the last king of the House of Wessex, ruling from 1042 to 1066....

. After the Norman conquest the 387 manors, that had been in Saxon hands, were replaced by just 16 heads of manors.

| The owners of Sussex post 1066 | Number of manors | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | William I | 2 |

| 2 | Lanfranc Lanfranc Lanfranc was Archbishop of Canterbury, and a Lombard by birth.-Early life:Lanfranc was born in the early years of the 11th century at Pavia, where later tradition held that his father, Hanbald, held a rank broadly equivalent to magistrate... , Archbishop of Canterbury Archbishop of Canterbury The Archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and principal leader of the Church of England, the symbolic head of the worldwide Anglican Communion, and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. In his role as head of the Anglican Communion, the archbishop leads the third largest group... |

8 |

| 3 | Stigand, Bishop of Selsey* Stigand of Selsey Stigand was the last Bishop of Selsey, and first Bishop of Chichester.-Life:Shortly after the Norman Conquest of 1066, there was a purge of the English episcopate, Archbishop Stigand was deposed in 1070 along with four other bishops, including Æthelric II of Selsey, probably because of his... |

9 |

| 4 | Gilbert, Abbot of Westminster | 1 |

| 5 | Abbot of Fécamp | 3 |

| 6 | Osborn, Bishop of Exeter | 4 |

| 7 | Abbot of Winchester | 2 |

| 8 | Gauspert, Abbot of Battle | 2 |

| 9 | Abbot of St Edward's | 1 |

| 10 | Odo** | 1 |

| 11 | Eldred** | 1 |

| 12 | William son of Robert, Count of Eu | 108 |

| 13 | Robert, Count of Mortain Robert, Count of Mortain Robert, Count of Mortain, 1st Earl of Cornwall was a Norman nobleman and the half-brother of William I of England. Robert was the son of Herluin de Conteville and Herleva of Falaise and was full brother to Odo of Bayeux. The exact year of Robert's birth is unknown Robert, Count of Mortain, 1st... |

81 |

| 14 | William de Warenne William de Warenne, 1st Earl of Surrey William de Warenne, 1st Earl of Surrey, Seigneur de Varennes is one of the very few proven Companions of William the Conqueror known to have fought at the Battle of Hastings in 1066... |

43 |

| 15 | William de Braose William de Braose, 1st Lord of Bramber William de Braose , First Lord of Bramber was previously lord of Briouze, Normandy. He was granted lands in England by William the Conqueror soon after he and his followers had invaded and controlled Saxon England.- Norman victor :De Braose was given extensive lands in Sussex by 1073... |

38 |

| 16 | Roger, Earl of Montgomery | 83 |

| |align="right"| Total | 387 | |

| Notes: * The See was moved from Selsey to Chichester during Stigands tenure. ** Odo and Eldred may have been Saxon Lords. |

||

The 16 people, in charge of the manors, were known as the Tenentes in capite

Tenant-in-chief

In medieval and early modern European society the term tenant-in-chief, sometimes vassal-in-chief, denoted the nobles who held their lands as tenants directly from king or territorial prince to whom they did homage, as opposed to holding them from another nobleman or senior member of the clergy....

in other words the chief tenants who held their land directly from the crown. The list includes nine ecclesiasticals although the portion of their landholding is quite small and was virtually no different to that under Edward the Confessor, and it is possible that two of the lords may have been Saxon. This means that 353 of the 387 manors in Sussex would have been wrested from their Saxon owners and given to Norman Lords by William the Conqueror

The county was of great importance to the Normans; Hastings and Pevensey being on the most direct route for Normandy. Because of this the county was divided into five new baronies, called rapes, each with at least one town and a castle. This enabled the ruling group of Normans to control the manorial revenues and thus the greater part of the county's wealth.

William, the Conqueror gave these rapes to five of his most trusted Barons:

- Roger of Montgomery - the combined Rapes of Chichester and Arundel.

- William de Braose - Rape of BramberRape of BramberThe Rape of Bramber is one of the rapes, the traditional sub-divisions unique to the historic county of Sussex in England. Bramber is a former barony, originally based around the castle of Bramber and its village, overlooking the river Adur.-History:...

. - William de Warenne - Rape of Lewes

- Robert, Count of Mortain - Rape of Pevensey

- Robert, Count of Eu - Rape of Hastings

Historically the land holdings of each Saxon lord had been scattered, but now the lords lands were determined by the borders of the rape. The unit of land, known as the hide

Hide (unit)

The hide was originally an amount of land sufficient to support a household, but later in Anglo-Saxon England became a unit used in assessing land for liability to "geld", or land tax. The geld would be collected at a stated rate per hide...

, in Sussex had eight instead of the usual four virgate

Virgate

The virgate or yardland was a unit of land area measurement used in medieval England, typically outside the Danelaw, and was held to be the amount of land that a team of two oxen could plough in a single annual season. It was equivalent to a quarter of a hide, so was nominally thirty acres...

s,(a virgate being equal to the amount of land two oxen can plough in a season).

The county boundary was long and somewhat indeterminate on the north, owing to the dense forest of Andredsweald. Evidence of this is seen in Domesday Book

Domesday Book

Domesday Book , now held at The National Archives, Kew, Richmond upon Thames in South West London, is the record of the great survey of much of England and parts of Wales completed in 1086...

by the survey of Worth and Lodsworth under Surrey

Surrey

Surrey is a county in the South East of England and is one of the Home Counties. The county borders Greater London, Kent, East Sussex, West Sussex, Hampshire and Berkshire. The historic county town is Guildford. Surrey County Council sits at Kingston upon Thames, although this has been part of...

, and also by the fact that as late as 1834 the present parishes of north and south Amersham

Amersham

Amersham is a market town and civil parish within Chiltern district in Buckinghamshire, England, 27 miles north west of London, in the Chiltern Hills. It is part of the London commuter belt....

in Sussex were part of Hampshire

Hampshire

Hampshire is a county on the southern coast of England in the United Kingdom. The county town of Hampshire is Winchester, a historic cathedral city that was once the capital of England. Hampshire is notable for housing the original birthplaces of the Royal Navy, British Army, and Royal Air Force...

.

Jurisdiction

The system of hundreds had been introduced during the time of the Saxons. In the 7th century Sussex has been estimated to have contained 7,000 families or hides. The creation of the rapes by the Normans introduced boundaries that divided some of the hundreds (and also some of the manors) causing a certain amount of fragmentation. The Arundel Rape covered nearly all of what is now West Sussex until about 1250 when it was split into two rapes, the Arundel Rape and the Chichester Rape. Ultimately Sussex was divided into six rapes; Chichester, Arundel, Bramber, Lewes, Pevensey and Hastings.At the time of the Domesday Survey, Sussex contained fifty nine hundreds. This eventually increased to sixty-three hundreds and remained unchanged till the 19th century, with thirty eight retaining their original names. The reason why the remainder had their names changed was probably due to the meeting-place of the hundred court being altered. These courts were in private hands in Sussex; either of the Church, or of great barons and local lords.

Independent from the hundreds were the boroughs.

In 1107-9 there was construction of a county gaol, in Chichester Castle

Chichester Castle

Chichester Castle stood in the city of the same name in West Sussex . Shortly after the Norman Conquest of England, Roger de Montgomerie, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury, ordered the construction of a castle at Chichester. The castle at Chichester was one of 11 fortified sites to be established in Sussex...

, however the castle was demolished in around 1217 and another gaol built on the same site. That gaol is known to have been used until 1269, when the site of the prison was given to the Greyfriars

Franciscan

Most Franciscans are members of Roman Catholic religious orders founded by Saint Francis of Assisi. Besides Roman Catholic communities, there are also Old Catholic, Anglican, Lutheran, ecumenical and Non-denominational Franciscan communities....

to build a priory. In 1242 the counties of Surrey and Sussex were formerly united, and a sharing of prison accommodation resulted almost immediately. Sussex men were imprisoned in Guildford gaol. There were requests for the provision of a county gaol in both Chichester and Lewes at various times to no avail. However the national gaol system became overloaded during the Peasants' Revolt

Peasants' Revolt

The Peasants' Revolt, Wat Tyler's Rebellion, or the Great Rising of 1381 was one of a number of popular revolts in late medieval Europe and is a major event in the history of England. Tyler's Rebellion was not only the most extreme and widespread insurrection in English history but also the...

of 1381, and the earl of Arundel was obliged to imprison people in his castles at Arundel and Lewes. Thus Sussex managed to get a county gaol again at Lewes in 1487 and there it remained until it was moved to Horsham in 1541 for a period.

In the middle of the 16th century the assizes were usually held at Horsham or East Grinstead. In the middle of the 17th century a gaol was built in Horsham, then in 1775 a new gaol was built to replace it. In 1788 an additional gaol was built at Petworth, known as the Petworth House of Correction. There were further Houses of Correction built at Lewes and Battle.