Power: A New Social Analysis

Encyclopedia

Power: A New Social Analysis (1st imp. London 1938, Allen & Unwin

, 328 pp.) is a work in social philosophy

written by Bertrand Russell

. Power, for Russell, is one's ability to achieve goals. In particular, Russell has in mind social power

, that is, power over people.

The volume contains a number of arguments. However, four themes have a central role in the overall work. The first theme given treatment in the analysis is that the lust

for power is a part of human nature. Second, the work emphasizes that there are different forms of social power, and that these forms are substantially interrelated. Third, Power insists that organizations are usually connected with certain kinds of individual

s. Finally, the work ends by arguing that arbitrary

rulership can and should be subdued.

Throughout the work, Russell's ambition is to develop a new method of conceiving the social sciences

as a whole. For him, all topics in the social sciences are merely examinations of the different forms of power — chiefly the economic

, military

, cultural

, and civil

forms (Russell 1938:4). Eventually, he hoped that social science would be robust enough to capture the laws of social dynamics

, which would describe how and when one form of power changes into another. (Russell 1938:4–6) As a secondary goal of the work, Russell is at pains to reject single-cause accounts of social power, such as the economic determinism

he attributes to Karl Marx

. (Russell 1938:4, 95)

of power.

, is somewhat pessimistic

. By Russell's account, the desire to empower oneself is unique to human nature. No other animal besides Homo sapiens

, he argues, is capable of being so unsatisfied with their lot, that they should try to accumulate more goods

than meet their need

s. The "impulse to power", as he calls it, does not arise unless one's basic desire

s have been sated. (Russell 1938:3) Then the imagination

stirs, motivating the actor to gain more power. In Russell's view, the love of power is nearly universal among people, although it takes on different guises from person to person. A person with great ambitions may become the next Caesar

, but others may be content to merely dominate the home

. (Russell 1938:9)

This impulse to power is not only explicitly present in leaders, but also sometimes implicitly in those who follow. It is clear that a leader may pursue and profit from enacting their own agenda

This impulse to power is not only explicitly present in leaders, but also sometimes implicitly in those who follow. It is clear that a leader may pursue and profit from enacting their own agenda

, but in a "genuinely cooperative enterprise", the followers seem to gain vicariously from the achievements of the leader. (Russell 1938:7–8)

In stressing this point, Russell is explicitly rebutting Friedrich Nietzsche

's infamous "master-slave morality

" argument. Russell explains:

The existence of implicit power, he explains, is why people are capable of tolerating social inequality for an extended period of time (Russell 1938:8).

However, Russell is quick to note that the invocation of human nature

should not come at the cost of ignoring the exceptional personal temperament

s of power-seekers. Following Adler (1927) — and to an extent echoing Nietzsche — he separates individuals into two classes: those who are imperious in a particular situation, and those who are not. The love of power, Russell tells us, is probably not motivated by Freudian

complexes, (i.e., resentment of one's father, lust for one's mother

, drives towards Eros and Thantatos (Love and Death drives, which constitute the basis of all human drives, etc.,) but rather by a sense of entitlement which arises from exceptional and deep-rooted self-confidence. (Russell 1938:11)

The imperious person is successful due to both mental and social factors. For instance, the imperious tend to have an internal confidence

in their own competence

and decisiveness which is relatively lacking in those who follow. (Russell 1938:13) In reality, the imperious may or may not actually be possessed of genuine skill

; rather, the source of their power may also arise out of their hereditary or religious role

. (Russell 1938:11)

Non-imperious persons include those who submit to a ruler, and those who withdraw entirely from the situation. A confident and competent candidate for leadership may withdraw from a situation when they lack the courage to challenge a particular authority, are timid

by temperament, simply do not have the means to acquire power by the usual methods, are entirely indifferent to matters of power, and/or are moderated by a well-developed sense of duty

. (Russell 1938:13–17)

Accordingly, while the imperious orator will tend to prefer a passionate crowd

over a sympathetic one, the timid orator (or subject) will have the opposite preferences. The imperious orator is interested mostly in a mob that is more given to rash emotion than to reflection. (Russell 1938:18) The orator will try to engineer

two 'layers' of belief in his crowd: "a superficial layer, in which the power of the enemy is magnified so as to make great courage seem necessary, and a deeper layer, in which there is a firm conviction of victory" (Russell 1938:18). By contrast, the timid will seek a sense of belonging, and "the reassurance which is felt in being one of a crowd who all feel alike" (Russell 1938:17).

When any given person has a crisis in confidence, and is placed in a terrifying situation, they will tend to behave in a predictable way: first, they submit to the rule of those who seem to have greater competence in the most relevant task, and second, they will surround themselves with that mass of persons who share a similarly low level of confidence. Thus, people submit to the rule of the leader in a kind of emergency solidarity. (Russell 1938:9–10)

In order to understand how organizations operate, Russell explains, we must first understand the basic methods by which they can exercise power at all — that is, we must understand the manner in which individuals are persuaded to follow

some authority. Russell breaks the forms of influence down into three very general categories: the power of force and coercion

; the power of inducement

s, such as operant conditioning

and group conformity

; and the power of propaganda

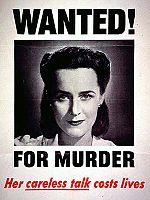

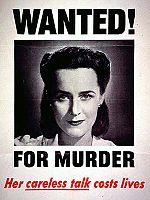

and/or habit (Russell 1938:24).

To explain each form, Russell provides illustrations. The power of mere force is like the tying of a rope around a pig's belly and lifting it up to a ship while ignoring its cries. The power of inducements is likened to two things: either conditioning, as exemplified by circus animals which have been trained to perform this-or-that trick for an audience

, or group acquiescence, as when the leader among sheep is dragged along by chains in order to get the rest of the flock to follow. Finally, the power of propaganda is akin to the use of carrot and stick to influence the behavior of a donkey, in the sense that the donkey is being persuaded that making certain actions (following the carrot, avoiding the stick) would be more or less to their benefit. (Russell 1938:24)

Russell makes a distinction between tradition

al, revolution

ary, and naked forms of psychological influence. (Russell 1938:27) These psychological types overlap with the forms of influence in some respects: for instance, naked power can be reduced to coercion alone. (Russell 1938:63) But the other types are distinct units of analysis, and require separate treatments.

. In all cases, the sources of naked power are the fear

s of the powerless and the ambitions of the powerful (Russell 1938:127). As an example of naked power, Russell recalls the story of Agathocles

, the son of a potter who became the tyrant

of Syracuse. (Russell 1938:69–72)

Russell argues that naked power arises within a government

under certain social conditions: when two or more fanatical creed

s are contending for governance, and when all traditional beliefs have decayed

. A period of naked power may end by foreign conquest

, the creation of stability, and/or the rise of a new religion

(Russell 1938:74).

The process by which an organization achieves sufficient prominence that it is able to exercise naked power can be described as the rule of three phases (Russell 1938:63). According to this rule, what begins as fanaticism

on the part of some crowd eventually produces conquest by means of naked power. Eventually, the acquiescence of the outlying population transforms naked power into traditional power. Finally, once a traditional power has taken hold, it engages in the suppression of dissent

by the use of naked power.

For Russell, economic power is parallel to the power of conditioning. (Russell 1938:25) However, unlike Marx, he emphasizes that economic power is not primary, but rather, derives from a combination of the forms of power. By his account, economics is dependent largely upon the functioning of law, and especially, property law; and law is to a large degree a function of the power over opinion, which cannot be entirely explained by wage, labor, and trade. (Russell 1938:95)

Ultimately, Russell argues that economic power is attained through the ability to defend one's territory (and to conquer other lands), to possess the materials

for the cultivation of one's resources, and to be able to satisfy the demand

s of others on the market. (Russell 1938:97–101, 107)

is impotent unless it is generally respected." (Russell 1938:109) Still, he admits that military force may cause opinion, and (with few exceptions) be the thing that imbues opinion with power in the first place:

Thus, although the power over opinion may occur with or without force, the power of a creed arises only after a powerful and persuasive minority has willingly adopted the creed.

The exception here is the case of Western science, which seemingly rose in cultural appeal despite being unpopular with establishment forces. Russell explains the popularity of science is not grounded on a general respect for reason

, but rather is grounded entirely on the fact that science produces technology

, and technology produces things that people desire. Similarly, religion, advertising

, and propaganda all have power because of their connections with the desires of their audiences. Russell's conclusion is that reason has very limited, though specific, sway over the opinions of persons. For reason is only effective when it appeals to desire. (Russell 1938:111–112)

Russell then inquires into the power that reason has over a community

, as contrasted with fanatic

ism. It would seem that the power of reason is that it is able to increase the odds of success in practical matters by way of technical efficiency

. The cost of allowing for reasoned inquiry is the tolerance of intellectual disagreement, which in turn provokes skepticism

and dims the power of fanaticism. Conversely, it would seem that a community is stronger and more cohesive if there is widespread agreement within it over certain creeds, and reasoned debate is rare. If these two opposing conditions are both to be fully exploited for short-term gains, then it would demand two things: first, that some creed be held both by the majority opinion (through force and propaganda), and second, that the majority of intellectual class concurs (through reasoned discussion). In the long-term, however, creeds tend to provoke weariness, light skepticism, outright disbelief, and finally, apathy. (Russell 1938:123–125)

Russell is acutely aware that power tends to coalesce in the hands of a minority, and no less so when it comes to power over opinion. The result is systematic propaganda, or the monopoly over propaganda by the state. Perhaps surprisingly, Russell avers that the consequences of systematic propaganda are not as dire as one might expect. (Russell 1938:114–115) A true monopoly over opinion leads to careless arrogance among leaders, as well as to indifference to the well-being

Russell is acutely aware that power tends to coalesce in the hands of a minority, and no less so when it comes to power over opinion. The result is systematic propaganda, or the monopoly over propaganda by the state. Perhaps surprisingly, Russell avers that the consequences of systematic propaganda are not as dire as one might expect. (Russell 1938:114–115) A true monopoly over opinion leads to careless arrogance among leaders, as well as to indifference to the well-being

of the governed, and a lack of credulity on behalf of the governed towards the state. In the long-term, the net result is:

By contrast, the shrewd propagandist of the contemporary state will allow for disagreement, so that false established opinions will have something to react to. In Russell's words: "Lies need competition if they are to retain their vigour." (Russell 1938:115)

By "traditional power", Russell has in mind the ways in which people will appeal to the force of habit

in order to justify a political regime. It is in this sense that traditional power is psychological and not historical

; since traditional power is not entirely based on a commitment to some linear historical creed, but rather, on mere habit. Moreover, traditional power need not be based on actual history, but rather be based on imagined or fabricated history. Thus he writes that "Both religious and secular innovators — at any rate those who have had most lasting success — have appealed, as far as they could, to tradition, and have done whatever lay in their power to minimise the elements of novelty in their system." (Russell 1938:40)

The two clearest examples of traditional power are the cases of kingly power and priestly power. Russell traces both back historically to certain roles which served some function in early societies. The priest is akin to the medicine man

of a tribe, who is thought to have unique powers of cursing and healing at their disposal (Russell 1938:36). In most contemporary cases, priests rely on religious social movement

s grounded in charismatic authority, which have been more effective at usurping power than those religions that lack icon

ic founders (Russell 1938:39–40). The history of the king is more difficult to examine, and the researcher can only speculate on their origins. At the very least, the power of kingship seems to be advanced by war

, even if warmaking was not the king's original function (Russell 1938:56).

When the forms of traditional power come to an end, there tends to be a corresponding change in creeds. If the traditional creeds are doubted without any alternative, then the traditional authority relies more and more on the use of naked power. And where the traditional creeds are wholly replaced with alternative ones, traditional power gives rise to revolutionary power (Russell 1938:82).

"Revolutionary power" contrasts with traditional power in that it appeals to popular assent

to some creed, and not merely popular acquiescence or habit. Thus, for the revolutionary, power is a means to an end, and the end is some creed or other. Whatever its intentions, the power of the revolutionary tends to either devolve back into naked power over time, or else to transform into traditional power (Russell 1938:82).

The revolutionary faces at least two special problems. First, the transformation back into naked power occurs when revolutionary power has been around for a long period without achieving a resolution to its key conflict. At some point, the original goal of the creed

tends to be forgotten, and consequently, the fanatics of the movement change their goals and aspire toward mere domination (Russell 1938:92). Second, the revolutionary must always deal with the threat of counter-revolutionaries, and is hence faced with a dilemma: because revolutionary power must by definition think that the original revolution was justified, it "cannot, logically, contend that all subsequent revolutions must be wicked" (Russell 1938:87).

A transition into traditional power is also possible. Just as there are two kinds of traditional power — the priestly and the kingly — there are two kinds of revolutionary power, namely, the soldier of fortune and the divine conqueror. Russell classes Benito Mussolini

and Napoleon Bonaparte

as soldiers of fortune, and Adolf Hitler

, Oliver Cromwell

, and Vladimir Lenin

as divine conquerors (Russell 1938:12). Nonetheless, the traditional forms bear only an imperfect relationship, if any, to the revolutionary forms.

s. The purpose of discussing organizations is that they seem to be one of the most common sources of social power. By an "organization", Russell means a set of people who share some activities, and directed at common goals, which is typified by a redistribution of power (Russell 1938:128). Organizations differ in size and type, though common to them all is the tendency for inequality of power to increase as membership increases.

An exhaustive list of the types of organization would be impossible, since the list would be as long as a list of human reasons to organize themselves in groups. However, Russell takes interest in only a small sample of organizations. The army

and police, economic organizations, educational organizations, organizations of law, political parties, and churches

are all recognized as societal entities. (Russell 1938:29–34,128,138-140)

The researcher might also measure the organization by its use of communication

, transport

ation, size, and distribution of power relative to the population. (Russell 1938:130,132-134) Improved abilities to communicate and transport tend to stabilize larger organizations and disrupt smaller ones.

Any given organization cannot be easily reduced to a particular form of power. For instance, the police

and army are quite obviously instruments of force and coercion, but it would be facile to say that they have power simply because of their ability to physically coerce. Rather, the police are regarded as instruments of a legitimate institution by some population, and the organization depends upon propaganda and habit to maintain popular deference to their authority. Similarly, economic organizations operate by the use of conditioning, in the form of money; but the strength of an economy arguably depends in large part on the functional operation of law enforcement which makes commerce possible, by the regulation of peace

and property right

s. (Russell 1938:25,95)

The general effect of an organization, Russell believes, is either to increase the well-being of persons, or to aid the survival of the organization itself: "[I]n the main, the effects of organisations, apart from those resulting from governmental self-preservation, are such as to increase individual happiness and well-being." (Russell 1938:170)

Of those whose wills are facilitated by an organization, kinds include the gentleman, the sage, the economic magnate, the political statesman, and the covert manager (or political wire-puller). Each beneficiary of power is parasitic upon certain kinds of organizations, and has certain key traits which uniquely put them at advantage (Russell 1938:29–34):

Thus, a political wire-puller such as Grigori Rasputin

enjoys power best when playing off another person's hereditary power, or when the organization benefits largely from an air of mystery. By contrast, the wirepuller suffers a wane in power when the organizational élite is made up of competent individuals

(Russell 1938:34).

Of those whose wills may be suppressed, we may include customer

s, voluntary members, involuntary members, and enemies (in order of ascending severity). Each form of membership is paired with typical forms of suppression. The will of the customer may be thwarted through fraud

or deception

, but this at least may be beneficial in providing the customer with the symbolic pleasure of some material goods. Voluntary organizations are able to threaten sanctions, such as expulsion, on its members. Voluntary organizations serve the positive function of providing relatively benign outlets for the human passion for drama

, and for the impulse to power. Involuntary membership abandons all pretense to the benign. The clearest example of this kind of organization, for Russell, is the State. (Russell 1938:171–173)

Organizations may also be directed specifically at influencing persons at some stage of life. Thus, we have midwives and doctor

s who are legally obliged to deliver the baby; as the child grows, the school

, parent

s, and mass media

come to the fore; as they reach working age, various economic organizations pull for the agent's attention; the church and the institution of marriage impact the actor in obvious ways; and finally, the State may provide a pension

to the elderly (Russell 1938:166–168).

, oligarchies

, and democracies

. In these ways, any organization — be it economic, or political — is able to seek out its goals.

Each form of government has its own merits and failings:

However, monarchies have severe problems. Contra Hobbes, no monarchy can be said to arise from a social

contract within the wide population. Moreover, if a monarchy is hereditary, then the royal offspring will likely

have no skill at governance; and if not, then civil war will ensue to determine the next in line. Finally, and

perhaps most obviously, the monarch is not necessarily compelled to have any regard for the well-being of his or her

subjects (Russell 1938:150–151).

There is a distinction between positive and private forms of morality. Positive morality tends to be associated with traditional power and following ancient principles with a narrow focus; for example, the norm

s and taboo

s of marital law

. Personal morality is associated with revolutionary power and the following of one's own conscience

. (Russell 1938:186–206)

The dominant social system will have some impact on the reigning positive moral codes of the population. In a system where filial piety is dominant, there will be greater emphasis in a culture upon the wisdom of the elderly. (Russell 1938:188–189) In a monarchy, the culture will be encouraged to believe in a morality of submission, with cultural taboos placed upon use of the imagination; both of which increase social cohesion by encouraging the self-censorship of dissent. (Russell 1938:190–191) Priestly power is not as impressive, even when it is in full bloom. At its peak, priestly power depends on not being opposed by kingly power and not being usurped by a morality of conscience; and even then, it faces the threat of wide skepticism. (Russell 1938:192–193) Still, some moral convictions do not seem to have any source at all in the power elite: for example, the treatment of homosexuality

in the early twentieth century does not seem to be tied to the success of a particular rulership. (Russell 1938:194)

Russell wonders whether some other basis for ethics can be found besides positive morality. Russell associates positive morality with conservatism

, and understands it as a way of acting which stifles the spirit of peace and fails to curb strife. (Russell 1938:197) Meanwhile, personal morality is the ultimate source of positive morality, and is more grounded in the intellect

. (Russell 1938:198–199) However, personal morality is so deeply connected with the desires of individuals that, if it were left to be the sole guide to moral conduct, it would lead to the social chaos of the "anarchic rebel". (Russell 1938:206)

Advocating a compromise between positive and private morality, Russell first emphasizes that there is such a thing as moral progress, a progress which may occur through revolutions. (Russell 1938:199) Second, he provides a method by which we can test whether a particular sort of private morality is a form of progress:

Some of those who have attempted to find an escape from the impulse to power have resorted to forms of quietism or pacifism

. One major proponent of such approaches was the philosopher Laozi

. From Russell's perspective, such views are incoherent, since they only deny themselves coercive power, but retain an interest in persuading others to their cause; and persuasion is a form of power, for Russell. Moreover, he argues that the love of power can actually be a good thing. For instance, if one feels a certain duty towards their neighbors, they may attempt to attain power in order to help those neighbors (Russell 1938:215–216). In sum, the focus of any policy should not be on a ban on kinds of power, but rather, on certain kinds of use of power (Russell 1938:221).

Other thinkers have emphasized the pursuit of power as a virtue. Some philosophies are rooted in the love of power because philosophies tend to be coherent unification in the pursuit of some goal or desire. Just as a philosophy may strive for truth, it may also strive for happiness, virtue

, salvation, or, finally, power. Among those philosophies which Russell condemns as rooted in love of power: all forms of idealism

and anti-realism

, such as Johann Gottlieb Fichte

's solipsism; certain forms of Pragmatism

; Henri Bergson

's doctrine of Creative evolution

; and the works of Friedrich Nietzsche (Russell 1938:209–214).

According to Russell's outlook on power, there are four conditions under which power ought to be pursued with moral conviction. First, it must be pursued only as a means to some end, and not as an end in itself; moreover, if it is an end in itself, then it must be of comparatively lower value

than one's other goals. Second, the ultimate goal must be to help satisfy the desires of others. Third, the means by which one pursues one's goal must not be egregious or malign, such that they outweigh the value of the end; as (for instance) the gassing of children for the sake of future democracy (Russell 1938:201). Fourth, moral doctrines should aim toward truth and honesty, not the manipulation of others (Russell 1938:216–218).

In order to enact these views, Russell advises the reader to discourage cruel temperaments which arise out of a lack of opportunities. Moreover, the reader should encourage the growth of constructive skills, which provide the person with an alternative to easier and more destructive alternatives. Finally, they should encourage cooperative feeling, and curb competitive desires (Russell 1938:219–220, 222).

.

In order to succeed in the taming of arbitrary political rule, Russell says, a community's goal ought to be to encourage democracy. Russell insists that the beginning of all ameliorative reforms to government must presuppose democracy as a rule. Even lip service to oligarchies – for example, support for purportedly benevolent dictators – must be dismissed as fantastic. (Russell 1938:226)

Moreover, democracy must be infused with a respect for the autonomy of persons, so that the political body does not collapse into the tyranny of the majority

. In order to prevent this result, people must have a well-developed sense of separation between acquiescence to the collective will, and respect for the discretion of the individual. (Russell 1938:227)

Collective action should be restricted to two domains. First, it should be used to treat problems that are primarily "geographical", which include issues of sanitation, transportation, electricity

, and external threats. Second, it ought to be used when a kind of individual freedom poses a major threat to public order; for instance, speech that incites the breaking of law (Russell 1938:227–228). The exception to this rule is when there is a minority which densely populates a certain well-defined area, in which case, political devolution

is preferable.

In formulating his outlook on the preferable size of government, Russell encounters a dilemma. He notes that, the smaller the democracy, the more empowerment the citizen feels; yet the larger the democracy, the more the citizen's passions and interests are inflamed. In both situations, the result is voter fatigue

. (Russell 1938:229) There are two possible solutions to this problem: to organize political life according to vocational interests, as with unionization

; or to organize it according to interest groups. (Russell 1938:229–230)

A federal government is only sensible, for Russell, when it has limited but well-defined powers. Russell advocates the creation of a world government

made up of sovereign nation-states (Russell 1938:197, 230–31). On his view, the function of a world government should only be to ensure the avoidance of war and the pursuit of peace (Russell 1938:230-31). On the world stage, democracy would be impossible, because of the negligible power any particular individual could have in comparison with the entire human race.

One final suggestion for political policy reform is the notion that there ought to be a political balance in every branch of public service. Lack of balance in public institutions creates havens for reactionary forces, which in turn undermine democracy. Russell emphasizes two conditions necessary for the achievement of balance. He advocates, first, the abolition of the legal standing of confession

s as evidence, to remove the incentive for extraction of confession under torture

by the police (Russell 1938:232). Second, the creation of dual branches of police to investigate particular crimes: one which presumes the innocence of the accused, the other presuming guilt

(Russell 1938:233).

"Competition

", for Russell, is a word that may have many uses. Although most often meant to refer to competition between companies, it may also be used to speak of competition between states, between ideologues, between classes, rivals, trusts, workers, etc. On this topic, Russell ultimately wishes to answer two questions: "First, in what kinds of cases is competition technically wasteful? Secondly, in what cases is it desirable on non-technical grounds?" (Russell 1938:176). In asking these questions, he has two concerns directly in mind: economic competition, and the competition of propaganda.

The question of whether or not economic competition is defensible requires an examination from two perspectives: the moral point of view and the technical point of view.

From the view of the technician, certain goods and services can only be provided efficiently by a centralized authority. For Russell, it seems to be an economic fact that bigger organizations were capable of producing items at a certain standard

, and best suited to fill needs that are geographical in nature, such as railway

s and water treatment

. By contrast, smaller organizations (like businesses) are best suited to create products that are customized and local. (Russell 1938:176–177;234)

From the view of the ethicist, competition between states is on the same moral plane as competition between modern businesses (Russell 1938:177). Indeed, by Russell's account, economic power and political power are both capable of devastation:

Since they are morally equivalent, perhaps it is not surprising that the cure for political injustices is identical to the cure for economic ones: namely, the institution of democracy in both economic and political spheres (Russell 1938:234).

By 'economic democracy', Russell means a kind of democratic socialism

, which at the very least involves the nationalization

of select industries (railways, water, television). In order for this to operate effectively, he argues that the social system must be such that power is distributed across a society of highly autonomous persons. (Russell 1938:238–240)

Russell is careful to indicate that his support for nationalization rests on the assumption that it can be accomplished under the auspices of a robust democracy, and that it may be safeguarded against statist tyranny. If either condition fail, then nationalization is undesirable. In delivering this warning, Russell emphasizes the distinction between ownership

and control

. He points out that nationalization — which would allow the citizens to collectively own

an industry — would not guarantee any of them control over the industry. In the same way, shareholders own parts of companies, but the control of the company ultimately rests with the CEO (Russell 1938:235).

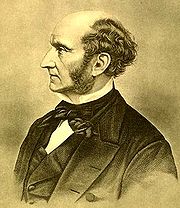

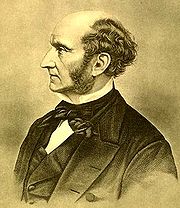

Control over propaganda is another matter. When forming his argument here, Russell specifically targets the doctrines of John Stuart Mill

Control over propaganda is another matter. When forming his argument here, Russell specifically targets the doctrines of John Stuart Mill

. Russell argues that Mill's argument for the freedom of speech

is too weak, so long as it is balanced against the harm principle

; for any speech worth protecting for political reasons is likely to cause somebody harm. For example, the citizen ought to have the opportunity to impeach malicious governors, but that would surely harm the governor, at the very least (Russell 1938:179).

Russell replaces Mill's analysis with an examination of the issue from four perspectives: the perspective of the governor

, the citizen

, the innovator

, and the philosopher

. The rational governor is always threatened by revolutionary activities, and can always be expected to ban speech which calls for assassination. Yet the governor would be advised to allow freedom of speech in order to prevent and diminish discontent among the subjects, and has no reason to suppress ideas which are unrelated to his governance, for instance the Copernican

doctrine of heliocentrism

. Relatedly, the citizen mainly understands free speech as an extension of the right to do peaceably that which could only otherwise be done through violence

(Russell 1938:179–182).

The innovator does not tend to care much about free speech, since they engage in innovation despite social resistance. Innovators may be separated into three categories: the hard millenarian

s, who believe in their doctrine to the exclusion of all others, and who only seek to protect the dissemination of their own creeds; the virtuous millenarians, who emphasize that revolutionary transitions must begin through rational persuasion and the guidance of sages, and so are supportive of free speech; and the progressive

s, who cannot foresee the direction of future progress, but recognize that the free exchange of ideas is a prerequisite to it. For the philosopher, free speech allows people to engage in rational doubt, and to grow in their prudential duties. (Russell 1938:182–185)

In any case, the citizen's right to dissent and to decide their governor is sacrosanct for Russell. He believes that a true public square could be operated by state-run media outlets, like the BBC

, which would be charged with the duty to provide a wide range of points of view on political matters. For certain other topics, like art and science, the fullest and freest competition between ideas must be guaranteed. (Russell 1938:185)

The final discussion in the work is concerned with Russell's views on education

. (Russell 1938:242–251) Citizens of a healthy democracy must have two virtues, for Russell: the sense of self-reliance and confidence necessary for autonomous action; and the humility required to submit to the will of the majority when it has spoken. (Russell 1938:244) The last chapter of Power: A New Social Analysis concentrates significantly on the question of how to inspire confidence in students, from an educator's point of view.

Two major conditions are necessary. First, the citizen/student must be free from hatred, fear, and the impulse to submit. (Russell 1938:244–245) Economic opportunities will have some impact on the student's temperament in this regard, and so, economic reform

s need to be made to create more opportunities. But reform to the education system is also necessary, in particular, to foster in the student a kindness

, curiosity

, and intellectual commitment to science. The common trait of students with the scientific mind is a sense of balance between dogmatism and skepticism. (Russell 1938:246)

Moreover, the student must have good instructors, who emphasize reason over rhetoric. Russell indicates that the critical mind is an essential feature of the healthy citizen of a democracy, since collective hysteria

is one of the greatest threats to democracy (Russell 1938:248). In order to foster a critical mind, he suggests, the teacher ought to show the students the consequences of pursuing one's feelings over one's thoughts. For example, the teacher might allow students to choose a field trip between two different locations: one fantastic place which is given a dull overview, and a shabby place which is recommended by impressive advertisements. In teaching history, the teacher might examine a particular event from a multitude of different perspectives, and allow the students to use their critical faculties to make assessments of each. (Russell 1938:247) In all cases, the object would be to encourage self-growth

, a willingness to be tentative in judgment, and responsiveness to evidence. (Russell 1938:250)

The work ends with the following words:

, and contains more than one pointed reference to the dictatorships of Nazi Germany

and fascist

Italy

, and one reference to the persecution

of German Czechoslovakia

ns. (Russell 1938:147) When his remarks treat of current affairs, they are often pessimistic. "Although men hate one another, exploit one another, and torture one another, they have, until recently, given their reverence to those who preached a different way of life." (Russell 1938: 204; emphasis added) As Kirk Willis remarked on Russell's outlook during the 1930s, "the foreign and domestic policies of successive national governments repelled him, as did the triumph of totalitarian regimes on the continent and the seemingly inexorable march to war brought in their wake... Despairing that war could be avoided and convinced that such a European-wide conflict would herald a new dark age of barbarism and bigotry, Russell gave voice to his despondency in Which Way to Peace? (1936) – not so much a reasoned defence of appeasement as an expression of defeatism". (Russell 1938:xxii-xxiii)

Ultimately, with his new analysis in hand, Russell hoped to instruct others on how to tame arbitrary power. He hoped that a stable world government

composed of sovereign

nation-states would eventually arise which would dissuade nations from engaging in war. In context, this argument was made years after the dissolution of the League of Nations

(and years before the creation of the United Nations

). Also, at many times during the work, Russell also mentions his desire to see a kind of socialism

take root. This was true to his convictions of the time, during a phase in his career where he was convinced in the plausibility of guild socialism

. (Sledd 1994; Russell 1918)

ian and epistemologist, had many side-interests in history, politics

, and social philosophy

. The paradigmatic public intellectual, Russell wrote prolifically in the latter topics to a wide and receptive audience. As one scholar writes, "Russell's prolific output spanned the whole range of philosophical and political thought, and he has probably been more widely read in his own lifetime than any other philosopher in history". (Griffin:129)

However, his writings in political philosophy have been relatively neglected by those working in the social sciences. From the point of view of many commentators, Power: A New Social Analysis has proven itself to be no exception to that trend. Russell would later comment that his work "fell rather flat" (Russell 1969). Both Samuel Brittan

and Kirk Willis, who wrote the preface and introduction to the 2004 edition (respectively), both observed the relative lack of success of the work (Russell 1938:viii, xxiv–xxv).

One reason why Power might be more obscure than competing texts in political philosophy is that it is written in a historical style which is not in keeping with its own theoretical goals. Willis remarked that, with hindsight, "Some of the responsibility for its tepid reception... rests with the book itself. A work of political sociology rather than of political theory, it does not in fact either offer a comprehensive new social analysis or fashion new tools of social investigation applicable to the study of power in all times or places." (Russell 1938:xxv)

Willis's review, written more than half a century past the original writing of the volume, is in some respects a gentler way of phrasing the work's immediate reception. One of Russell's contemporaries wrote: "As a contribution to social science... or to the study of government, the volume is very disappointing... In this pretentious volume, Russell shows only the most superficial familiarity with progress made in the study of social phenomena or in any special field of social research, either with techniques of inquiry, or with materials assembled, or with interpretations developed... it seems doubtful that the author knows what is going on in the world of social science." (Merriam, 1939) Indeed, the very preface of the work candidly states: "As usual, those who look in Russell's pronouncements for dotty opinions will be able to find a few". (Russell 1938:x) Still, some scholars, like Edward Hallet Carr, found the work of some use. (Carr 2001:131)

Russell is routinely praised for his analytic treatment of philosophical issues. One commentator, quoted in (Griffin:202), observes that "In the forty-five years preceding publication of Strawson's 'On Referring', Russell's theory was practically immune from criticism. There is not a similar phenomenon in contemporary analytic philosophy". Yet Power, along with many of his later works in social philosophy, is not obviously analytic. Rather, it takes the form of a series of examinations of semi-related topics, with a narrative dominated by historical illustrations. Nevertheless, Brittan emphasized the strengths of the treatise by remarking that it can be understood as "an enjoyable romp through history, in part anticipating some of the 1945 History of Western Philosophy

, but ranging wider" (Russell 1938:vii).

Allen & Unwin

Allen & Unwin, formerly a major British publishing house, is now an independent book publisher and distributor based in Australia. The Australian directors have been the sole owners of the Allen & Unwin name since effecting a management buy out at the time the UK parent company, Unwin Hyman, was...

, 328 pp.) is a work in social philosophy

Social philosophy

Social philosophy is the philosophical study of questions about social behavior . Social philosophy addresses a wide range of subjects, from individual meanings to legitimacy of laws, from the social contract to criteria for revolution, from the functions of everyday actions to the effects of...

written by Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, OM, FRS was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, and social critic. At various points in his life he considered himself a liberal, a socialist, and a pacifist, but he also admitted that he had never been any of these things...

. Power, for Russell, is one's ability to achieve goals. In particular, Russell has in mind social power

Power (sociology)

Power is a measurement of an entity's ability to control its environment, including the behavior of other entities. The term authority is often used for power perceived as legitimate by the social structure. Power can be seen as evil or unjust, but the exercise of power is accepted as endemic to...

, that is, power over people.

The volume contains a number of arguments. However, four themes have a central role in the overall work. The first theme given treatment in the analysis is that the lust

Lust

Lust is an emotional force that is directly associated with the thinking or fantasizing about one's desire, usually in a sexual way.-Etymology:The word lust is phonetically similar to the ancient Roman lustrum, which literally meant "purification"...

for power is a part of human nature. Second, the work emphasizes that there are different forms of social power, and that these forms are substantially interrelated. Third, Power insists that organizations are usually connected with certain kinds of individual

Individual

An individual is a person or any specific object or thing in a collection. Individuality is the state or quality of being an individual; a person separate from other persons and possessing his or her own needs, goals, and desires. Being self expressive...

s. Finally, the work ends by arguing that arbitrary

Arbitrary

Arbitrariness is a term given to choices and actions subject to individual will, judgment or preference, based solely upon an individual's opinion or discretion.Arbitrary decisions are not necessarily the same as random decisions...

rulership can and should be subdued.

Throughout the work, Russell's ambition is to develop a new method of conceiving the social sciences

Social sciences

Social science is the field of study concerned with society. "Social science" is commonly used as an umbrella term to refer to a plurality of fields outside of the natural sciences usually exclusive of the administrative or managerial sciences...

as a whole. For him, all topics in the social sciences are merely examinations of the different forms of power — chiefly the economic

Economics

Economics is the social science that analyzes the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. The term economics comes from the Ancient Greek from + , hence "rules of the house"...

, military

Military

A military is an organization authorized by its greater society to use lethal force, usually including use of weapons, in defending its country by combating actual or perceived threats. The military may have additional functions of use to its greater society, such as advancing a political agenda e.g...

, cultural

Culture

Culture is a term that has many different inter-related meanings. For example, in 1952, Alfred Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn compiled a list of 164 definitions of "culture" in Culture: A Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions...

, and civil

Civil law (legal system)

Civil law is a legal system inspired by Roman law and whose primary feature is that laws are codified into collections, as compared to common law systems that gives great precedential weight to common law on the principle that it is unfair to treat similar facts differently on different...

forms (Russell 1938:4). Eventually, he hoped that social science would be robust enough to capture the laws of social dynamics

Social dynamics

Social dynamics can refer to the behavior of groups that results from the interactions of individual group members as well to the study of the relationship between individual interactions and group level behaviors...

, which would describe how and when one form of power changes into another. (Russell 1938:4–6) As a secondary goal of the work, Russell is at pains to reject single-cause accounts of social power, such as the economic determinism

Economic determinism

Economic determinism is the theory which attributes primacy to the economic structure over politics in the development of human history. It is usually associated with the theories of Karl Marx, although many Marxist thinkers have dismissed plain and unilateral economic determinism as a form of...

he attributes to Karl Marx

Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx was a German philosopher, economist, sociologist, historian, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. His ideas played a significant role in the development of social science and the socialist political movement...

. (Russell 1938:4, 95)

The work

The new social analysis examines at least four general topics: the nature of power, the forms of power, the structure of organizations, and the ethicsEthics

Ethics, also known as moral philosophy, is a branch of philosophy that addresses questions about morality—that is, concepts such as good and evil, right and wrong, virtue and vice, justice and crime, etc.Major branches of ethics include:...

of power.

Nature of power

Russell's view of human nature, like that of Thomas HobbesThomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury , in some older texts Thomas Hobbs of Malmsbury, was an English philosopher, best known today for his work on political philosophy...

, is somewhat pessimistic

Pessimism

Pessimism, from the Latin word pessimus , is a state of mind in which one perceives life negatively. Value judgments may vary dramatically between individuals, even when judgments of fact are undisputed. The most common example of this phenomenon is the "Is the glass half empty or half full?"...

. By Russell's account, the desire to empower oneself is unique to human nature. No other animal besides Homo sapiens

Human

Humans are the only living species in the Homo genus...

, he argues, is capable of being so unsatisfied with their lot, that they should try to accumulate more goods

Good (economics and accounting)

In economics, a good is something that is intended to satisfy some wants or needs of a consumer and thus has economic utility. It is normally used in the plural form—goods—to denote tangible commodities such as products and materials....

than meet their need

Need

A need is something that is necessary for organisms to live a healthy life. Needs are distinguished from wants because a deficiency would cause a clear negative outcome, such as dysfunction or death. Needs can be objective and physical, such as food, or they can be subjective and psychological,...

s. The "impulse to power", as he calls it, does not arise unless one's basic desire

Preference

-Definitions in different disciplines:The term “preferences” is used in a variety of related, but not identical, ways in the scientific literature. This makes it necessary to make explicit the sense in which the term is used in different social sciences....

s have been sated. (Russell 1938:3) Then the imagination

Imagination

Imagination, also called the faculty of imagining, is the ability of forming mental images, sensations and concepts, in a moment when they are not perceived through sight, hearing or other senses...

stirs, motivating the actor to gain more power. In Russell's view, the love of power is nearly universal among people, although it takes on different guises from person to person. A person with great ambitions may become the next Caesar

Caesar (title)

Caesar is a title of imperial character. It derives from the cognomen of Julius Caesar, the Roman dictator...

, but others may be content to merely dominate the home

Domestic violence

Domestic violence, also known as domestic abuse, spousal abuse, battering, family violence, and intimate partner violence , is broadly defined as a pattern of abusive behaviors by one or both partners in an intimate relationship such as marriage, dating, family, or cohabitation...

. (Russell 1938:9)

Political agenda

A political agenda is a set of issues and policies laid out by an executive or cabinet in government that tries to influence current and near-future political news and debate....

, but in a "genuinely cooperative enterprise", the followers seem to gain vicariously from the achievements of the leader. (Russell 1938:7–8)

In stressing this point, Russell is explicitly rebutting Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche was a 19th-century German philosopher, poet, composer and classical philologist...

's infamous "master-slave morality

Master-slave morality

Master-slave morality is a central theme of Friedrich Nietzsche's works, in particular the first essay of On the Genealogy of Morality. Nietzsche argued that there were two fundamental types of morality: 'Master morality' and 'slave morality'...

" argument. Russell explains:

- "Most men do not feel in themselves the competence required for leading their group to victory, and therefore seek out a captain who appears to possess the courage and sagacity necessary for the achievement of supremacy... Nietzsche accused Christianity of inculcating a slave-morality, but ultimate triumph was always the goal. 'Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth. '" (Russell 1938:9, emphasis his).

The existence of implicit power, he explains, is why people are capable of tolerating social inequality for an extended period of time (Russell 1938:8).

However, Russell is quick to note that the invocation of human nature

Human nature

Human nature refers to the distinguishing characteristics, including ways of thinking, feeling and acting, that humans tend to have naturally....

should not come at the cost of ignoring the exceptional personal temperament

Temperament

In psychology, temperament refers to those aspects of an individual's personality, such as introversion or extroversion, that are often regarded as innate rather than learned...

s of power-seekers. Following Adler (1927) — and to an extent echoing Nietzsche — he separates individuals into two classes: those who are imperious in a particular situation, and those who are not. The love of power, Russell tells us, is probably not motivated by Freudian

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud , born Sigismund Schlomo Freud , was an Austrian neurologist who founded the discipline of psychoanalysis...

complexes, (i.e., resentment of one's father, lust for one's mother

Oedipus complex

In psychoanalytic theory, the term Oedipus complex denotes the emotions and ideas that the mind keeps in the unconscious, via dynamic repression, that concentrate upon a boy’s desire to sexually possess his mother, and kill his father...

, drives towards Eros and Thantatos (Love and Death drives, which constitute the basis of all human drives, etc.,) but rather by a sense of entitlement which arises from exceptional and deep-rooted self-confidence. (Russell 1938:11)

The imperious person is successful due to both mental and social factors. For instance, the imperious tend to have an internal confidence

Confidence

Confidence is generally described as a state of being certain either that a hypothesis or prediction is correct or that a chosen course of action is the best or most effective. Self-confidence is having confidence in oneself. Arrogance or hubris in this comparison, is having unmerited...

in their own competence

Skill

A skill is the learned capacity to carry out pre-determined results often with the minimum outlay of time, energy, or both. Skills can often be divided into domain-general and domain-specific skills...

and decisiveness which is relatively lacking in those who follow. (Russell 1938:13) In reality, the imperious may or may not actually be possessed of genuine skill

Skill

A skill is the learned capacity to carry out pre-determined results often with the minimum outlay of time, energy, or both. Skills can often be divided into domain-general and domain-specific skills...

; rather, the source of their power may also arise out of their hereditary or religious role

Role

A role or a social role is a set of connected behaviours, rights and obligations as conceptualised by actors in a social situation. It is an expected or free or continuously changing behaviour and may have a given individual social status or social position...

. (Russell 1938:11)

| "I greatly doubt whether the men who become pirate chiefs are those who are filled with retrospective terror of their fathers, or whether Napoleon, at Austerlitz, really felt that he was getting even with Madame Mère. I know nothing of the mother of Attila, but I rather suspect that she spoilt the little darling, who subsequently found the world irritating because it sometimes resisted his whims." |

| Bertrand Russell (1938:11) |

Non-imperious persons include those who submit to a ruler, and those who withdraw entirely from the situation. A confident and competent candidate for leadership may withdraw from a situation when they lack the courage to challenge a particular authority, are timid

Shyness

In humans, shyness is a social psychology term used to describe the feeling of apprehension, lack of comfort, or awkwardness experienced when a person is in proximity to, approaching, or being approached by other people, especially in new situations or with unfamiliar people...

by temperament, simply do not have the means to acquire power by the usual methods, are entirely indifferent to matters of power, and/or are moderated by a well-developed sense of duty

Duty

Duty is a term that conveys a sense of moral commitment to someone or something. The moral commitment is the sort that results in action and it is not a matter of passive feeling or mere recognition...

. (Russell 1938:13–17)

Accordingly, while the imperious orator will tend to prefer a passionate crowd

Crowd

A crowd is a large and definable group of people, while "the crowd" is referred to as the so-called lower orders of people in general...

over a sympathetic one, the timid orator (or subject) will have the opposite preferences. The imperious orator is interested mostly in a mob that is more given to rash emotion than to reflection. (Russell 1938:18) The orator will try to engineer

Rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of discourse, an art that aims to improve the facility of speakers or writers who attempt to inform, persuade, or motivate particular audiences in specific situations. As a subject of formal study and a productive civic practice, rhetoric has played a central role in the Western...

two 'layers' of belief in his crowd: "a superficial layer, in which the power of the enemy is magnified so as to make great courage seem necessary, and a deeper layer, in which there is a firm conviction of victory" (Russell 1938:18). By contrast, the timid will seek a sense of belonging, and "the reassurance which is felt in being one of a crowd who all feel alike" (Russell 1938:17).

When any given person has a crisis in confidence, and is placed in a terrifying situation, they will tend to behave in a predictable way: first, they submit to the rule of those who seem to have greater competence in the most relevant task, and second, they will surround themselves with that mass of persons who share a similarly low level of confidence. Thus, people submit to the rule of the leader in a kind of emergency solidarity. (Russell 1938:9–10)

Forms of power

To begin with, Russell is interested in classifying the different ways in which one human being may have power over another — what he calls the forms of power. The forms may be subdivided into two: influence over persons, and the psychological types of influence. (Russell 1938:24,27)In order to understand how organizations operate, Russell explains, we must first understand the basic methods by which they can exercise power at all — that is, we must understand the manner in which individuals are persuaded to follow

Obedience (human behavior)

In human behavior, obedience is the quality of being obedient, which describes the act of carrying-out commands or being actuated. Obedience differs from compliance, which is behavior influenced by peers, and from conformity, which is behavior intended to match that of the majority. Obedience can...

some authority. Russell breaks the forms of influence down into three very general categories: the power of force and coercion

Coercion

Coercion is the practice of forcing another party to behave in an involuntary manner by use of threats or intimidation or some other form of pressure or force. In law, coercion is codified as the duress crime. Such actions are used as leverage, to force the victim to act in the desired way...

; the power of inducement

Reinforcement

Reinforcement is a term in operant conditioning and behavior analysis for the process of increasing the rate or probability of a behavior in the form of a "response" by the delivery or emergence of a stimulus Reinforcement is a term in operant conditioning and behavior analysis for the process of...

s, such as operant conditioning

Operant conditioning

Operant conditioning is a form of psychological learning during which an individual modifies the occurrence and form of its own behavior due to the association of the behavior with a stimulus...

and group conformity

Conformity

Conformity is the process by which an individual's attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors are influenced by other people.Conformity may also refer to:*Conformity: A Tale, a novel by Charlotte Elizabeth Tonna...

; and the power of propaganda

Propaganda

Propaganda is a form of communication that is aimed at influencing the attitude of a community toward some cause or position so as to benefit oneself or one's group....

and/or habit (Russell 1938:24).

To explain each form, Russell provides illustrations. The power of mere force is like the tying of a rope around a pig's belly and lifting it up to a ship while ignoring its cries. The power of inducements is likened to two things: either conditioning, as exemplified by circus animals which have been trained to perform this-or-that trick for an audience

Audience

An audience is a group of people who participate in a show or encounter a work of art, literature , theatre, music or academics in any medium...

, or group acquiescence, as when the leader among sheep is dragged along by chains in order to get the rest of the flock to follow. Finally, the power of propaganda is akin to the use of carrot and stick to influence the behavior of a donkey, in the sense that the donkey is being persuaded that making certain actions (following the carrot, avoiding the stick) would be more or less to their benefit. (Russell 1938:24)

Russell makes a distinction between tradition

Tradition

A tradition is a ritual, belief or object passed down within a society, still maintained in the present, with origins in the past. Common examples include holidays or impractical but socially meaningful clothes , but the idea has also been applied to social norms such as greetings...

al, revolution

Revolution

A revolution is a fundamental change in power or organizational structures that takes place in a relatively short period of time.Aristotle described two types of political revolution:...

ary, and naked forms of psychological influence. (Russell 1938:27) These psychological types overlap with the forms of influence in some respects: for instance, naked power can be reduced to coercion alone. (Russell 1938:63) But the other types are distinct units of analysis, and require separate treatments.

Naked and economic power

When force is used in the absence of other forms, it is called "naked power". In other words, naked power is the ruthless exertion of force without the desire for, or attempt at, consentConsent

Consent refers to the provision of approval or agreement, particularly and especially after thoughtful consideration.- Types of consent :*Implied consent is a controversial form of consent which is not expressly granted by a person, but rather inferred from a person's actions and the facts and...

. In all cases, the sources of naked power are the fear

Fear

Fear is a distressing negative sensation induced by a perceived threat. It is a basic survival mechanism occurring in response to a specific stimulus, such as pain or the threat of danger...

s of the powerless and the ambitions of the powerful (Russell 1938:127). As an example of naked power, Russell recalls the story of Agathocles

Agathocles

Agathocles , , was tyrant of Syracuse and king of Sicily .-Biography:...

, the son of a potter who became the tyrant

Tyrant

A tyrant was originally one who illegally seized and controlled a governmental power in a polis. Tyrants were a group of individuals who took over many Greek poleis during the uprising of the middle classes in the sixth and seventh centuries BC, ousting the aristocratic governments.Plato and...

of Syracuse. (Russell 1938:69–72)

Russell argues that naked power arises within a government

Government

Government refers to the legislators, administrators, and arbitrators in the administrative bureaucracy who control a state at a given time, and to the system of government by which they are organized...

under certain social conditions: when two or more fanatical creed

Creed

A creed is a statement of belief—usually a statement of faith that describes the beliefs shared by a religious community—and is often recited as part of a religious service. When the statement of faith is longer and polemical, as well as didactic, it is not called a creed but a Confession of faith...

s are contending for governance, and when all traditional beliefs have decayed

Anomie

Anomie is a term meaning "without Law" to describe a lack of social norms; "normlessness". It describes the breakdown of social bonds between an individual and their community ties, with fragmentation of social identity and rejection of self-regulatory values. It was popularized by French...

. A period of naked power may end by foreign conquest

Invasion

An invasion is a military offensive consisting of all, or large parts of the armed forces of one geopolitical entity aggressively entering territory controlled by another such entity, generally with the objective of either conquering, liberating or re-establishing control or authority over a...

, the creation of stability, and/or the rise of a new religion

Religion

Religion is a collection of cultural systems, belief systems, and worldviews that establishes symbols that relate humanity to spirituality and, sometimes, to moral values. Many religions have narratives, symbols, traditions and sacred histories that are intended to give meaning to life or to...

(Russell 1938:74).

The process by which an organization achieves sufficient prominence that it is able to exercise naked power can be described as the rule of three phases (Russell 1938:63). According to this rule, what begins as fanaticism

Fanaticism

Fanaticism is a belief or behavior involving uncritical zeal, particularly for an extreme religious or political cause or in some cases sports, or with an obsessive enthusiasm for a pastime or hobby...

on the part of some crowd eventually produces conquest by means of naked power. Eventually, the acquiescence of the outlying population transforms naked power into traditional power. Finally, once a traditional power has taken hold, it engages in the suppression of dissent

Dissent

Dissent is a sentiment or philosophy of non-agreement or opposition to a prevailing idea or an entity...

by the use of naked power.

For Russell, economic power is parallel to the power of conditioning. (Russell 1938:25) However, unlike Marx, he emphasizes that economic power is not primary, but rather, derives from a combination of the forms of power. By his account, economics is dependent largely upon the functioning of law, and especially, property law; and law is to a large degree a function of the power over opinion, which cannot be entirely explained by wage, labor, and trade. (Russell 1938:95)

Ultimately, Russell argues that economic power is attained through the ability to defend one's territory (and to conquer other lands), to possess the materials

Means of production

Means of production refers to physical, non-human inputs used in production—the factories, machines, and tools used to produce wealth — along with both infrastructural capital and natural capital. This includes the classical factors of production minus financial capital and minus human capital...

for the cultivation of one's resources, and to be able to satisfy the demand

Supply and demand

Supply and demand is an economic model of price determination in a market. It concludes that in a competitive market, the unit price for a particular good will vary until it settles at a point where the quantity demanded by consumers will equal the quantity supplied by producers , resulting in an...

s of others on the market. (Russell 1938:97–101, 107)

The power of (and over) opinion

In Russell's model, power over the creeds and habits of persons is easy to miscalculate. He claims that, on the one hand, the economic determinists had underestimated the power of opinion. However, on the other hand, he argues that the case is easy to make that all power is power over opinion: for "Armies are useless unless the soldiers believe in the cause for which they are fighting... LawLaw

Law is a system of rules and guidelines which are enforced through social institutions to govern behavior, wherever possible. It shapes politics, economics and society in numerous ways and serves as a social mediator of relations between people. Contract law regulates everything from buying a bus...

is impotent unless it is generally respected." (Russell 1938:109) Still, he admits that military force may cause opinion, and (with few exceptions) be the thing that imbues opinion with power in the first place:

- "We thus have a kind of see-saw: first, pure persuasionPersuasionPersuasion is a form of social influence. It is the process of guiding or bringing oneself or another toward the adoption of an idea, attitude, or action by rational and symbolic means.- Methods :...

leading to the conversion of a minority; then force exerted to secure that the rest of the community shall be exposed to the right propaganda; and finally a genuine belief on the part of the great majority, which makes the use of force again unnecessary." (Russell 1938:110)

| "It is not altogether true that persuasion is one thing and force is another. Many forms of persuasion—even many of which everybody approves-- are really a kind of force. Consider what we do to our children. We do not say to them: 'Some people think the earth is round, and others think it is flat; when you grow up, you can, if you like, examine the evidence and form your own conclusion.' Instead of this we say: 'The earth is round.' By the time our children are old enough to examine the evidence, our propaganda has closed their minds..." |

| Bertrand Russell (1938:221) |

Thus, although the power over opinion may occur with or without force, the power of a creed arises only after a powerful and persuasive minority has willingly adopted the creed.

The exception here is the case of Western science, which seemingly rose in cultural appeal despite being unpopular with establishment forces. Russell explains the popularity of science is not grounded on a general respect for reason

Reason

Reason is a term that refers to the capacity human beings have to make sense of things, to establish and verify facts, and to change or justify practices, institutions, and beliefs. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, language, ...

, but rather is grounded entirely on the fact that science produces technology

Technology

Technology is the making, usage, and knowledge of tools, machines, techniques, crafts, systems or methods of organization in order to solve a problem or perform a specific function. It can also refer to the collection of such tools, machinery, and procedures. The word technology comes ;...

, and technology produces things that people desire. Similarly, religion, advertising

Advertising

Advertising is a form of communication used to persuade an audience to take some action with respect to products, ideas, or services. Most commonly, the desired result is to drive consumer behavior with respect to a commercial offering, although political and ideological advertising is also common...

, and propaganda all have power because of their connections with the desires of their audiences. Russell's conclusion is that reason has very limited, though specific, sway over the opinions of persons. For reason is only effective when it appeals to desire. (Russell 1938:111–112)

Russell then inquires into the power that reason has over a community

Community

The term community has two distinct meanings:*a group of interacting people, possibly living in close proximity, and often refers to a group that shares some common values, and is attributed with social cohesion within a shared geographical location, generally in social units larger than a household...

, as contrasted with fanatic

Fanaticism

Fanaticism is a belief or behavior involving uncritical zeal, particularly for an extreme religious or political cause or in some cases sports, or with an obsessive enthusiasm for a pastime or hobby...

ism. It would seem that the power of reason is that it is able to increase the odds of success in practical matters by way of technical efficiency

Efficiency (economics)

In economics, the term economic efficiency refers to the use of resources so as to maximize the production of goods and services. An economic system is said to be more efficient than another if it can provide more goods and services for society without using more resources...

. The cost of allowing for reasoned inquiry is the tolerance of intellectual disagreement, which in turn provokes skepticism

Skepticism

Skepticism has many definitions, but generally refers to any questioning attitude towards knowledge, facts, or opinions/beliefs stated as facts, or doubt regarding claims that are taken for granted elsewhere...

and dims the power of fanaticism. Conversely, it would seem that a community is stronger and more cohesive if there is widespread agreement within it over certain creeds, and reasoned debate is rare. If these two opposing conditions are both to be fully exploited for short-term gains, then it would demand two things: first, that some creed be held both by the majority opinion (through force and propaganda), and second, that the majority of intellectual class concurs (through reasoned discussion). In the long-term, however, creeds tend to provoke weariness, light skepticism, outright disbelief, and finally, apathy. (Russell 1938:123–125)

Quality of life

The term quality of life is used to evaluate the general well-being of individuals and societies. The term is used in a wide range of contexts, including the fields of international development, healthcare, and politics. Quality of life should not be confused with the concept of standard of...

of the governed, and a lack of credulity on behalf of the governed towards the state. In the long-term, the net result is:

"[to] delay revolution, but to make it more violent when it comes. When only one doctrine is officially allowed, men get no practice in thinking or in weighing alternatives; only a great wave of passionate revolt can dethrone orthodoxy; and in order to make the opposition sufficiently whole-hearted and violent to achieve success, it will seem necessary to deny even what was true in governmental dogma" (Russell 1938:115).

By contrast, the shrewd propagandist of the contemporary state will allow for disagreement, so that false established opinions will have something to react to. In Russell's words: "Lies need competition if they are to retain their vigour." (Russell 1938:115)

Revolutionary versus traditional power

Among the psychological types of influence, we have a distinction between traditional, naked, and revolutionary power. (Naked power, as noted earlier, is the use of coercion without any pretense to legitimacy.)By "traditional power", Russell has in mind the ways in which people will appeal to the force of habit

Habituation

Habituation can be defined as a process or as a procedure. As a process it is defined as a decrease in an elicited behavior resulting from the repeated presentation of an eliciting stimulus...

in order to justify a political regime. It is in this sense that traditional power is psychological and not historical

History

History is the discovery, collection, organization, and presentation of information about past events. History can also mean the period of time after writing was invented. Scholars who write about history are called historians...

; since traditional power is not entirely based on a commitment to some linear historical creed, but rather, on mere habit. Moreover, traditional power need not be based on actual history, but rather be based on imagined or fabricated history. Thus he writes that "Both religious and secular innovators — at any rate those who have had most lasting success — have appealed, as far as they could, to tradition, and have done whatever lay in their power to minimise the elements of novelty in their system." (Russell 1938:40)

The two clearest examples of traditional power are the cases of kingly power and priestly power. Russell traces both back historically to certain roles which served some function in early societies. The priest is akin to the medicine man

Medicine man

"Medicine man" or "Medicine woman" are English terms used to describe traditional healers and spiritual leaders among Native American and other indigenous or aboriginal peoples...

of a tribe, who is thought to have unique powers of cursing and healing at their disposal (Russell 1938:36). In most contemporary cases, priests rely on religious social movement

Social movement