History of the Cyclades

Encyclopedia

Cyclades

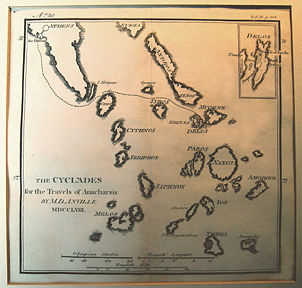

The Cyclades is a Greek island group in the Aegean Sea, south-east of the mainland of Greece; and a former administrative prefecture of Greece. They are one of the island groups which constitute the Aegean archipelago. The name refers to the islands around the sacred island of Delos...

(Greek

Greek language

Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages. Native to the southern Balkans, it has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning 34 centuries of written records. Its writing system has been the Greek alphabet for the majority of its history;...

: Κυκλάδες / Kykládes) are Greek

Greece

Greece , officially the Hellenic Republic , and historically Hellas or the Republic of Greece in English, is a country in southeastern Europe....

islands located in the southern part of the Aegean Sea

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea[p] is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea located between the southern Balkan and Anatolian peninsulas, i.e., between the mainlands of Greece and Turkey. In the north, it is connected to the Marmara Sea and Black Sea by the Dardanelles and Bosporus...

. The archipelago

Archipelago

An archipelago , sometimes called an island group, is a chain or cluster of islands. The word archipelago is derived from the Greek ἄρχι- – arkhi- and πέλαγος – pélagos through the Italian arcipelago...

contains some 2,200 islands, islets and rocks; just 33 islands are inhabited. For the ancients, they formed a circle (κύκλος / kyklos in Greek

Greek language

Greek is an independent branch of the Indo-European family of languages. Native to the southern Balkans, it has the longest documented history of any Indo-European language, spanning 34 centuries of written records. Its writing system has been the Greek alphabet for the majority of its history;...

) around the sacred island of Delos

Delos

The island of Delos , isolated in the centre of the roughly circular ring of islands called the Cyclades, near Mykonos, is one of the most important mythological, historical and archaeological sites in Greece...

, hence the name of the archipelago. The best-known are, from north to south and from east to west: Andros

Andros

Andros, or Andro is the northernmost island of the Greek Cyclades archipelago, approximately south east of Euboea, and about north of Tinos. It is nearly long, and its greatest breadth is . Its surface is for the most part mountainous, with many fruitful and well-watered valleys. The area is...

, Tinos

Tinos

Tinos is a Greek island situated in the Aegean Sea. It is located in the Cyclades archipelago. In antiquity, Tinos was also known as Ophiussa and Hydroessa . The closest islands are Andros, Delos, and Mykonos...

, Mykonos

Mykonos

Mykonos is a Greek island, part of the Cyclades, lying between Tinos, Syros, Paros and Naxos. The island spans an area of and rises to an elevation of at its highest point. There are 9,320 inhabitants most of whom live in the largest town, Mykonos, which lies on the west coast. The town is also...

, Naxos, Amorgos

Amorgos

Amorgos is the easternmost island of the Greek Cyclades island group, and the nearest island to the neighboring Dodecanese island group. Along with several neighboring islets, the largest of which is Nikouria Island, it comprises the municipality of Amorgos, which has a land area of...

, Syros

Syros

Syros , or Siros or Syra is a Greek island in the Cyclades, in the Aegean Sea. It is located south-east of Athens. The area of the island is . The largest towns are Ermoupoli, Ano Syros, and Vari. Ermoupoli is the capital of the island and the Cyclades...

, Paros

Paros

Paros is an island of Greece in the central Aegean Sea. One of the Cyclades island group, it lies to the west of Naxos, from which it is separated by a channel about wide. It lies approximately south-east of Piraeus. The Municipality of Paros includes numerous uninhabited offshore islets...

and Antiparos

Antiparos

Antiparos is a small inhabited island in the southern Aegean, at the heart of the Cyclades, which is less than one nautical mile from Paros, the port to which it is connected with a local ferry...

, Ios, Santorini

Santorini

Santorini , officially Thira , is an island located in the southern Aegean Sea, about southeast from Greece's mainland. It is the largest island of a small, circular archipelago which bears the same name and is the remnant of a volcanic caldera...

, Anafi

Anafi

Anafi is a Greek island community in the Cyclades. In 2001, it had a population of 273 inhabitants. Its land area is 40.370 km². It lies east of the island of Thíra...

, Kea

Kea (island)

Kea , also known as Gia or Tzia , Zea, and, in Antiquity, Keos , is an island of the Cyclades archipelago, in the Aegean Sea, in Greece. Kea is part of the Kea-Kythnos peripheral unit. Its capital, Ioulis, is inland at a high altitude and is considered quite picturesque...

, Kythnos

Kythnos

Kythnos is a Greek island and municipality in the Western Cyclades between Kea and Serifos. It is from the harbor of Piraeus. Kythnos is in area and has a coastline of about . It has more than 70 beaches, many of which are still inaccessible by road...

, Serifos

Serifos

Serifos is a Greek island municipality in the Aegean Sea, located in the western Cyclades, south of Kythnos and northwest of Sifnos. It is part of the Milos peripheral unit. The area is 75.207 km² and the population was 1,414 at the 2001 census. It is located about ESE of Piraeus...

, Sifnos

Sifnos

Sifnos is an island municipality in the Cyclades island group in Greece. The main town, near the center, is known as Apollonia home of the island's folklore museum and library. The town's name is thought to come from an ancient temple of Apollo on the site of the church of Panayia Yeraniofora...

, Folegandros

Folegandros

Folegandros is a small Greek island in the Aegean Sea which, together with Sikinos, Ios, Anafi and Santorini, forms the southern part of the Cyclades. Its surface area is about and it has 667 inhabitants....

and Sikinos

Sikinos

Sikinos is a Greek island and municipality in the Cyclades. It is located midway between the islands of Ios and Folegandros. Sikinos is part of the Santorini peripheral unit....

, Milos

Milos

Milos , is a volcanic Greek island in the Aegean Sea, just north of the Sea of Crete...

and Kimolos

Kimolos

Kimolos is a Greek island in the Aegean Sea, belonging to the islands group of Cyclades, located on the SW tip of them, near the bigger island of Milos. It is considered as a middle class, rural island, not included in the tourist hotspots, thus, ferry connection is sometimes of bad quality...

; to these can be added the little Cyclades: Irakleia

Irakleia, Cyclades

Irakleia is an island and a former community in the Cyclades, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Naxos and Lesser Cyclades, of which it is a municipal unit. Its population was officially 151 inhabitants at the 2001 census, and its land area 17.795 km². It...

, Schoinoussa

Schoinoussa

Schoinoussa is an island and a former community in the Cyclades, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Naxos and Lesser Cyclades, of which it is a municipal unit. It lies south of the island of Naxos, in the Small Cyclades group, between the island...

, Koufonisi

Koufonisi

Koufonisia is a former community in the Cyclades, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Naxos and Lesser Cyclades, of which it is a municipal unit. It consists of three main islands.-History:...

, Keros

Keros

Keros is an uninhabited Greek island in the Cyclades about southeast of Naxos. Administratively it is part of the community of Koufonisi. It has an area of and its highest point is...

and Donoussa

Donoussa

Donousa is an island and a former community in the Cyclades, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Naxos and Lesser Cyclades, of which it is a municipal unit...

, as well as Makronisos

Makronisos

Makronisos is an island in the Aegean sea, in Greece and is located close to the coast of Attica, facing the port of Lavrio. It has an elongated shape and its terrain is arid and rocky. In ancient times the island was called Helena. It is part of the prefecture of the Cyclades but it is not part...

between Kea and Attica

Attica

Attica is a historical region of Greece, containing Athens, the current capital of Greece. The historical region is centered on the Attic peninsula, which projects into the Aegean Sea...

, Gyaros

Gyaros

Gyaros is an arid and unpopulated Greek island of the northern Cyclades near in the islands Andros and Tinos, with an area of 23 square kilometres. It is a part of the municipality of Ano Syros, which lies primarily on the island of Syros. This and other small islands of the Aegean Sea served as...

, which lies before Andros, and Polyaigos

Polyaigos

Polýaigos is an uninhabited Greek island in the Cyclades near Milos and Kimolos. It is part of the community of Kimolos . Its name means "many goats", since it is inhabited only by goats....

to the east of Kimolos and Thirassia, before Santorini. At times they were also called by the generic name of Archipelago.

The islands are located at the crossroads between Europe

Europe

Europe is, by convention, one of the world's seven continents. Comprising the westernmost peninsula of Eurasia, Europe is generally 'divided' from Asia to its east by the watershed divides of the Ural and Caucasus Mountains, the Ural River, the Caspian and Black Seas, and the waterways connecting...

and Asia Minor

Asia Minor

Asia Minor is a geographical location at the westernmost protrusion of Asia, also called Anatolia, and corresponds to the western two thirds of the Asian part of Turkey...

and the Near East

Near East

The Near East is a geographical term that covers different countries for geographers, archeologists, and historians, on the one hand, and for political scientists, economists, and journalists, on the other...

as well as between Europe and Africa

Africa

Africa is the world's second largest and second most populous continent, after Asia. At about 30.2 million km² including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of the Earth's total surface area and 20.4% of the total land area...

. In antiquity, when navigation consisted only of cabotage

Cabotage

Cabotage is the transport of goods or passengers between two points in the same country by a vessel or an aircraft registered in another country. Originally starting with shipping, cabotage now also covers aviation, railways and road transport...

and sailors sought never to lose sight of land, they played an essential role as a stopover. Into the 20th century, this situation made their fortune (trade was one of their chief activities) and their misfortune (control of the Cyclades allowed for control of the commercial and strategic routes in the Aegean).

Numerous authors considered, or still consider them as a sole entity, a unit. The insular group is indeed rather homogeneous from a geomorphological point of view; moreover, the islands are visible from each other's shores while being distinctly separate from the continents that surround them. The dryness of the climate and of the soil also suggests unity. Although these physical facts are undeniable, other components of this unity are more subjective. Thus, one can read certain authors who say that the islands’ population is, of all the regions of Greece, the only original one, and has not been subjected to external admixtures. However, the Cyclades have very often known different destinies.

Their natural resources and their potential role as trade-route stopovers has allowed them to be peopled since the Neolithic

Neolithic

The Neolithic Age, Era, or Period, or New Stone Age, was a period in the development of human technology, beginning about 9500 BC in some parts of the Middle East, and later in other parts of the world. It is traditionally considered as the last part of the Stone Age...

. Thanks to these assets, they experienced a brilliant cultural flowering in the 3rd millennium BC: the Cycladic civilisation. The proto-historical powers, the Minoans and then the Mycenaeans, made their influence known there. The Cyclades had a new zenith in the Archaic period (8th – 6th century BC). The Persians tried to take them during their attempts to conquer Greece. Then they entered into Athens' orbit with the Delian Leagues. The Hellenistic kingdoms disputed their status while Delos became a great commercial power.

Commercial activities were pursued during the Roman and Byzantine Empires, yet they were sufficiently prosperous as to attract pirates' attention. The participants of the Fourth Crusade

Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade was originally intended to conquer Muslim-controlled Jerusalem by means of an invasion through Egypt. Instead, in April 1204, the Crusaders of Western Europe invaded and conquered the Christian city of Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman Empire...

divided the Byzantine Empire among themselves and the Cyclades entered the Venetian orbit. Western feudal lords created a certain number of fiefs, of which the Duchy of Naxos was the most important. The Duchy was conquered by the Ottoman Empire, which allowed the islands a certain administrative and fiscal autonomy. Economic prosperity continued despite the pirates. The archipelago had an ambiguous attitude towards the war of independence. Having become Greek in the 1830s, the Cyclades have shared the history of Greece since that time. At first they went through a period of commercial prosperity, still due to their geographic position, before the trade routes and modes of transport changed. After suffering a rural exodus, renewal began with the influx of tourists. However, tourism is not the Cyclades' only resource today.

.jpg)

Neolithic era

Argolis

Argolis is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the region of Peloponnese. It is situated in the eastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula.-Geography:...

, in Franchthi Cave

Franchthi Cave

Franchthi cave in the Peloponnese, in the southeastern Argolid, is a cave overlooking the Argolic Gulf opposite the Greek village of Koilada....

. Research there uncovered, in a layer dating to the 11th millennium BC, obsidian

Obsidian

Obsidian is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed as an extrusive igneous rock.It is produced when felsic lava extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimum crystal growth...

originating from Milos

Milos

Milos , is a volcanic Greek island in the Aegean Sea, just north of the Sea of Crete...

. The volcanic island was thus exploited and inhabited, not necessarily in permanent fashion, and its inhabitants were capable of navigating and trading across a distance of at least 150 km.

A permanent settlement on the islands could only be established by a sedentary population that had at its disposal methods of agriculture and animal husbandry that could exploit the few fertile plains. Hunter-gatherers would have had much greater difficulties. At the Maroula site on Kythnos a bone fragment has been uncovered and dated, using Carbon-14

Carbon-14

Carbon-14, 14C, or radiocarbon, is a radioactive isotope of carbon with a nucleus containing 6 protons and 8 neutrons. Its presence in organic materials is the basis of the radiocarbon dating method pioneered by Willard Libby and colleagues , to date archaeological, geological, and hydrogeological...

, to 7,500-6,500 BC. The oldest inhabited places are the islet of Saliango between Paros and Antiparos, Kephala on Kea, and perhaps the oldest strata are those at Grotta on Naxos. They date back to the 5th millennium BC.

On Saliango (at that time connected to its two neighbours, Paros and Antiparos), houses of stone without mortar have been found, as well as Cycladic statuettes. Estimates based on excavations in the cemetery of Kephala put the number of inhabitants at between forty-five and eighty. Studies of skulls have revealed bone deformations, especially in the vertebrae. They have been attributed to arthritic conditions, which afflict sedentary societies. Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis is a disease of bones that leads to an increased risk of fracture. In osteoporosis the bone mineral density is reduced, bone microarchitecture is deteriorating, and the amount and variety of proteins in bone is altered...

, another sign of a sedentary lifestyle, is present, but more rarely than on the continent in the same period. Life expectancy has been estimated at twenty years, with maximum ages reaching twenty-eight to thirty. Women tended to live less than men.

Cist

A cist from ) is a small stone-built coffin-like box or ossuary used to hold the bodies of the dead. Examples can be found across Europe and in the Middle East....

s are those belonging to men. Pottery was made without a lathe, judging by the hand-modelled clay balls; pictures were applied to the pottery using brushes, while incisions were made with the fingernails. The vases were then baked in a pit or a grinding wheel—kilns were not used and only low temperatures of 700˚-800˚C were reached. Small-sized metal objects have been found on Naxos. The operation of silver mines on Siphnos may also date to this period.

Cycladic civilisation

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a period characterized by the use of copper and its alloy bronze as the chief hard materials in the manufacture of some implements and weapons. Chronologically, it stands between the Stone Age and Iron Age...

. It is famous for its marble idols, found as far as Portugal

Portugal

Portugal , officially the Portuguese Republic is a country situated in southwestern Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Portugal is the westernmost country of Europe, and is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the West and South and by Spain to the North and East. The Atlantic archipelagos of the...

and the mouth of the Danube

Danube

The Danube is a river in the Central Europe and the Europe's second longest river after the Volga. It is classified as an international waterway....

, which proves its dynamism.

It is slightly older than the Minoan civilisation of Crete

Crete

Crete is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, and one of the thirteen administrative regions of Greece. It forms a significant part of the economy and cultural heritage of Greece while retaining its own local cultural traits...

. The beginnings of the Minoan civilisation were influenced by the Cycladic civilisation: Cycladic statuettes were imported into Crete and local artisans imitated Cycladic techniques; archaeological evidence supporting this notion has been found at Aghia Photia, Knossos

Knossos

Knossos , also known as Labyrinth, or Knossos Palace, is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and probably the ceremonial and political centre of the Minoan civilization and culture. The palace appears as a maze of workrooms, living spaces, and store rooms close to a central square...

and Archanes. At the same time, excavations in the cemetery of Aghios Kosmas in Attica

Attica

Attica is a historical region of Greece, containing Athens, the current capital of Greece. The historical region is centered on the Attic peninsula, which projects into the Aegean Sea...

have uncovered objects proving a strong Cycladic influence, due either to a high percentage of the population being Cycladic or to an actual colony originating in the islands.

Three great periods have traditionally been designated (equivalent to those that divide the Helladic on the continent and the Minoan in Crete):

- Early Cycladic I (EC I; 3200-2800 BC), also called the Grotta-Pelos Culture

- Early Cycladic II (EC II; 2800-2300 BC), also called the Keros-Syros Culture and often considered the apogee of Cycladic civilisation

- Early Cycladic III (EC III; 2300-2000 BC), also called the Phylakopi Culture

The study of skeletons found in tombs, always in cists, shows an evolution from the Neolithic. Osteoporosis was less prevalent although arthritic diseases continued to be present. Thus, diet had improved. Life expectancy progressed: men lived up to forty or forty-five years, but women only thirty. The sexual division of labour remained the same as that identified for the Early Neolithic: women busied themselves with small domestic and agricultural tasks, while men took care of larger duties and crafts. Agriculture, as elsewhere in the Mediterranean basin, was based on grain (mainly barley, which needs less water than wheat), grapevines and olive trees. Animal husbandry was already primarily concerned with goats and sheep, as well as a few hogs, but very few bovines, the raising of which is still poorly developed on the islands. Fishing completed the diet base, due for example to the regular migration of tuna

Tuna

Tuna is a salt water fish from the family Scombridae, mostly in the genus Thunnus. Tuna are fast swimmers, and some species are capable of speeds of . Unlike most fish, which have white flesh, the muscle tissue of tuna ranges from pink to dark red. The red coloration derives from myoglobin, an...

. At the time, wood was more abundant than today, allowing for the construction of house frames and boats.

The inhabitants of these islands, who lived mainly near the shore, were remarkable sailors and merchants, thanks to their islands’ geographic position. It seems that at the time, the Cyclades exported more merchandise than they imported, a rather unique circumstance during their history. The ceramics found at various Cycladic sites (Phylakopi on Milos, Aghia Irini on Kea and Akrotiri on Santorini) prove the existence of commercial routes going from continental Greece to Crete while mainly passing by the Western Cyclades, up until the Late Cycladic. Excavations at these three sites have uncovered vases produced on the continent or on Crete and imported onto the islands.

It is known that there were specialised artisans: founders, blacksmiths, potters and sculptors, but it is impossible to say if they made a living off their work. Obsidian from Milos remained the dominant material for the production of tools, even after the development of metallurgy, for it was less expensive. Tools have been found that were made of a primitive bronze, an alloy of copper and arsenic. The copper came from Kythnos and already contained a high volume of arsenic. Tin, the provenance of which has not been determined, was only later introduced into the islands, after the end of the Cycladic civilisation. The oldest bronze containing tin was found at Kastri on Tinos (dating to the time of the Phylakopi Culture) and their composition proves they came from Troad, either as raw materials or as finished products. Therefore, commercial exchanges between the Troad and the Cyclades existed.

These tools were used to work marble, above all coming from Naxos and Paros, either for the celebrated Cycladic idols, or for marble vases. It appears that marble was not then, like today, extracted from mines, but was quarried in great quantities. The emery of Naxos also furnished material for polishing. Finally, the pumice stone of Santorini allowed for a perfect finish.

The pigments that can be found on statuettes, as well as in tombs, also originated on the islands, as well as the azurite for blue and the iron ore for red.

Eventually, the inhabitants left the seashore and moved toward the islands’ summits within fortified enclosures rounded out by round towers at the corners. It was at this time that piracy might first have made an appearance in the archipelago.

Minoans and Mycenaeans

Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean Greece was a cultural period of Bronze Age Greece taking its name from the archaeological site of Mycenae in northeastern Argolis, in the Peloponnese of southern Greece. Athens, Pylos, Thebes, and Tiryns are also important Mycenaean sites...

from 1450 BC and the Dorians from 1100 BC. The islands, due to their relatively small size, could not fight against these highly centralised powers.

Literary sources

ThucydidesThucydides

Thucydides was a Greek historian and author from Alimos. His History of the Peloponnesian War recounts the 5th century BC war between Sparta and Athens to the year 411 BC...

writes that Minos

Minos

In Greek mythology, Minos was a king of Crete, son of Zeus and Europa. Every year he made King Aegeus pick seven men and seven women to go to Daedalus' creation, the labyrinth, to be eaten by The Minotaur. After his death, Minos became a judge of the dead in Hades. The Minoan civilization of Crete...

expelled the archipelago’s first inhabitants, the Carians

Carians

The Carians were the ancient inhabitants of Caria in southwest Anatolia.-Historical accounts:It is not clear when the Carians enter into history. The definition is dependent on corresponding Caria and the Carians to the "Karkiya" or "Karkisa" mentioned in the Hittite records...

, whose tombs were numerous on Delos. Herodotus

Herodotus

Herodotus was an ancient Greek historian who was born in Halicarnassus, Caria and lived in the 5th century BC . He has been called the "Father of History", and was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a...

specifies that the Carians, who bore a relation to the Leleges

Leleges

The Leleges were one of the aboriginal peoples of southwest Anatolia , who were already there when the Indo-European Hellenes emerged. The distinction between the Leleges and the Carians is unclear. According to Homer the Leleges were a distinct Anatolian tribe Homer...

, arrived from the continent. They were completely independent (“they paid no tribute”), but supplied sailors for Minos’ ships.

According to Herodotus, the Carians were the best warriors of their time and taught the Greeks to place plumes on their helmets, to represent insignia on their shields and to use straps to hold these.

Later, the Dorians would expel the Carians from the Cyclades; the former were followed by the Ionians, who turned the island of Delos into a great religious centre.

Cretan influence

The Cyclades also underwent a cultural differentiation. One group in the north around Kea and Syros tended to approach the Northeast Aegean from a cultural point of view, while the Southern Cyclades seem to have been closer to the Cretan civilisation. Ancient tradition speaks of a Minoan maritime empire, a sweeping image that demands some nuance, but it is nevertheless undeniable that Crete ended up having influence over the entire Aegean. This began to be felt more strongly beginning with the Late Cycladic, or the Late Minoan (from 1700/1600 BC), especially with regard to influence by Knossos

Knossos

Knossos , also known as Labyrinth, or Knossos Palace, is the largest Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete and probably the ceremonial and political centre of the Minoan civilization and culture. The palace appears as a maze of workrooms, living spaces, and store rooms close to a central square...

and Cydonia.

During the Late Minoan, important contacts are attested at Kea, Milos and Santorini; Minoan pottery and architectural elements (polythyra, skylights, frescoes) as well as signs of Linear A

Linear A

Linear A is one of two scripts used in ancient Crete before Mycenaean Greek Linear B; Cretan hieroglyphs is the second script. In Minoan times, before the Mycenaean Greek dominion, Linear A was the official script for the palaces and religious activities, and hieroglyphs were mainly used on seals....

have been found. The shards found on the other Cyclades appear to have arrived there indirectly from these three islands. It is difficult to determine the nature of the Minoan presence on the Cyclades: settler colonies, protectorate or trading post. For a time it was proposed that the great buildings at Akrotiri

Akrotiri (Santorini)

Akrotiri is the name of an excavation site of a Minoan Bronze Age settlement on the Greek island of Santorini, associated with the Minoan civilization due to inscriptions in Linear A, and close similarities in artifact and fresco styles. The excavation is named for a modern Greek village situated...

on Santorini (the West House) or at Phylakopi might be the palaces of foreign governors, but no formal proof exists that could back up this hypothesis. Likewise, too few archaeological proofs exist of an exclusively Cretan district, as would be typical for a settler colony. It seems that Crete defended her interests in the region through agents who could play a more or less important political role. In this way the Minoan civilisation protected its commercial routes. This would also explain why the Cretan influence was stronger on the three islands of Kea, Milos and Santorini. The Cyclades were a very active trading zone. The western axis of these three was of paramount importance. Kea was the first stop off the continent, being closest, near the mines of Laurium

Laurium

Laurium or Lavrio is a town in southeastern part of Attica, Greece. It is the seat of the municipality of Lavreotiki...

; Milos redistributed to the rest of the archipelago and remained the principal source of obsidian; and Santorini played for Crete the same role Kea did for Attica.

The great majority of bronze continued to be made with arsenic; tin progressed very slowly in the Cyclades, beginning in the northeast of the archipelago.

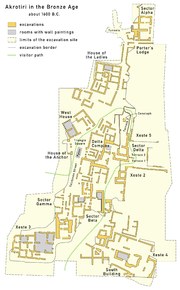

The explosion at Santorini (between the Late Minoan IA and the Late Minoan IB) buried and preserved an example of a habitat: Akrotiri.

Excavations since 1967 have uncovered a built-up area covering one hectare, not counting the defensive wall. The layout ran in a straight line, with a more or less orthogonal network of paved streets fitted with drains. The buildings had two to three floors and lacked skylights and courtyards; openings onto the street provided air and light. The ground floor contained the staircase and rooms serving as stores or workshops; the rooms on the next floor, slightly larger, had a central pillar and were decorated with frescoes. The houses had terraced roofs placed on beams that had not been squared, covered up with a vegetable layer (seaweed or leaves) and then several layers of clay soil, a practice that continues in traditional societies to this day.

From the beginning of excavations in 1967, the Greek archaeologist Spiridon Marinatos noted that the city had undergone a first destruction, due to an earthquake, before the eruption, as some of the buried objects were ruins, whereas a volcano alone may have left them intact. At almost the same time, the site of Aghia Irini on Kea was also destroyed by an earthquake. One thing is certain: after the eruption, Minoan imports stopped coming into Aghia Irini (VIII), to be replaced by Mycenaean imports.

Late Cycladic: Mycenaean domination

Beehive tomb

A beehive tomb, also known as a tholos tomb , is a burial structure characterized by its false dome created by the superposition of successively smaller rings of mudbricks or, more often, stones...

, characteristic of continental Mycenaean tombs, has been found on Mykonos. The Cyclades were continuously occupied until the Mycenaean civilisation began to decline.

Ionian arrival

The Ionians came from the continent around the 10th century BC, setting up the great religious sanctuary of Delos around three centuries later. The Homeric Hymn to ApolloApollo

Apollo is one of the most important and complex of the Olympian deities in Greek and Roman mythology...

(the first part of which may date to the 7th century BC) alludes to Ionian panegyric

Panegyric

A panegyric is a formal public speech, or written verse, delivered in high praise of a person or thing, a generally highly studied and discriminating eulogy, not expected to be critical. It is derived from the Greek πανηγυρικός meaning "a speech fit for a general assembly"...

s (which included athletic competitions, songs and dances). Archaeological excavations have shown that a religious centre was built on the ruins of a settlement dating to the Middle Cycladic.

It was between the 12th and the 8th centuries BC that the first Cycladic cities were built, including four on Kea (Ioulis, Korissia, Piessa and Karthaia) and Zagora on Andros, the houses of which were surrounded by a wall dated by archaeologists to 850 BC. Ceramics indicate the diversity of local production, and thus the differences between the islands. Hence, it seems that Naxos, the islet of Donoussa and above all Andros had links with Euboea

Euboea

Euboea is the second largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. The narrow Euripus Strait separates it from Boeotia in mainland Greece. In general outline it is a long and narrow, seahorse-shaped island; it is about long, and varies in breadth from to...

, while Milos and Santorini were in the Doric sphere of influence.

Schist

The schists constitute a group of medium-grade metamorphic rocks, chiefly notable for the preponderance of lamellar minerals such as micas, chlorite, talc, hornblende, graphite, and others. Quartz often occurs in drawn-out grains to such an extent that a particular form called quartz schist is...

slabs covered up with clay and truncated corners designed to allow beasts of burden to pass by more easily.

A new apogee

From the 8th century BC, the Cyclades experienced an apogee linked in great part to their natural riches (obsidian from Milos and Sifnos, silver from Syros, pumice stone from Santorini and marble, chiefly from Paros). This prosperity can also be seen from the relatively weak participation of the islands in the movement of Greek colonisationColonies in antiquity

Colonies in antiquity were city-states founded from a mother-city—its "metropolis"—, not from a territory-at-large. Bonds between a colony and its metropolis remained often close, and took specific forms...

, other than Santorini’s establishment of Cyrene

Cyrene, Libya

Cyrene was an ancient Greek colony and then a Roman city in present-day Shahhat, Libya, the oldest and most important of the five Greek cities in the region. It gave eastern Libya the classical name Cyrenaica that it has retained to modern times.Cyrene lies in a lush valley in the Jebel Akhdar...

. Cycladic cities celebrated their prosperity through great sanctuaries: the treasury of Sifnos, the Naxian column at Delphi or the terrace of lions offered by Naxos to Delos.

Classical Era

The wealth of the Cycladic cities thus attracted the interest of their neighbours. Shortly after the treasury of Sifnos at Delphi was built, forces from SamosSamos Island

Samos is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of Asia Minor, from which it is separated by the -wide Mycale Strait. It is also a separate regional unit of the North Aegean region, and the only municipality of the regional...

pillaged the island in 524 BC. At the end of the 6th century BC, Lygdamis

Lygdamis of Naxos

Lygdamis was the tyrant of Naxos, an island in the Cyclades, during the third quarter of the 6th Century BCE.He was initially a member of the oligarchy which ruled Naxos...

, tyrant of Naxos, ruled some of the other islands for a time.

The Persians tried to take the Cyclades near the end of the 5th century BC. Aristagoras

Aristagoras

Aristagoras was the leader of Miletus in the late 6th century BC and early 5th century BC.- Background :Aristagoras served as deputy governor of Miletus, a polis on the western coast of Anatolia around 500 BC. He was the son of Molpagoras, and son-in-law of Histiaeus, whom the Persians had set up...

, nephew of Histiaeus, tyrant of Miletus

Miletus

Miletus was an ancient Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia , near the mouth of the Maeander River in ancient Caria...

, launched an expedition with Artaphernes, satrap of Lydia

Lydia

Lydia was an Iron Age kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the modern Turkish provinces of Manisa and inland İzmir. Its population spoke an Anatolian language known as Lydian....

, against Naxos. He hoped to control the entire archipelago after taking this island. On the way there, Aristagoras quarreled with the admiral Megabetes, who betrayed the force by informing Naxos of the fleet’s approach. The Persians temporarily renounced their ambitions in the Cyclades due to the Ionian revolt.

Median Wars

When DariusDarius I of Persia

Darius I , also known as Darius the Great, was the third king of kings of the Achaemenid Empire...

launched his expedition against Greece

Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire of Persia and city-states of the Hellenic world that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the Greeks and the enormous empire of the Persians began when Cyrus...

, he ordered Datis

Datis

For other uses of the word Dati, see Dati .Datis or Datus was a Median admiral who served the Persian Empire, under Darius the Great...

and Artaphernes

Artaphernes

Artaphernes , was the brother of the king of Persia, Darius I of Persia, and satrap of Sardis.In 497 BC, Artaphernes received an embassy from Athens, probably sent by Cleisthenes, and subsequently advised the Athenians that they should receive back the tyrant Hippias.Subsequently he took an...

to take the Cyclades. They sacked Naxos, Delos was spared for religious reasons while Sifnos, Serifos and Milos preferred to submit and give up hostages. Thus the islands passed under Persian control. After Marathon

Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC, during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. It was the culmination of the first attempt by Persia, under King Darius I, to subjugate...

, Miltiades

Miltiades the Younger

Miltiades the Younger or Miltiades IV was the son of one Cimon, a renowned Olympic chariot-racer. Miltiades considered himself a member of the Aeacidae, and is known mostly for his role in the Battle of Marathon; as well as his rather tragic downfall afterwards. His son Cimon was a major Athenian...

set out to reconquer the archipelago, but he failed before Paros. The islanders provided the Persian fleet with sixty-seven ships, but on the eve of the Battle of Salamis

Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis was fought between an Alliance of Greek city-states and the Persian Empire in September 480 BCE, in the straits between the mainland and Salamis, an island in the Saronic Gulf near Athens...

, six or seven Cycladic ships (from Naxos, Kea, Kythnos, Serifos, Sifnos and Milos) would pass from the Greek side. Thus the islands won the right to appear on the tripod consecrated at Delphi.

Themistocles

Themistocles

Themistocles ; c. 524–459 BC, was an Athenian politician and a general. He was one of a new breed of politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy, along with his great rival Aristides...

, pursuing the Persian fleet across the archipelago, also sought to punish the islands most compromised with regard to the Persians, a prelude to Athenian domination.

In 479 BC, certain Cycladic cities (on Kea, Milos, Tinos, Naxos and Kythnos) were present beside other Greeks at the Battle of Plataea

Battle of Plataea

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479 BC near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between an alliance of the Greek city-states, including Sparta, Athens, Corinth and Megara, and the Persian Empire of Xerxes...

, as attested by the pedestal of the statue consecrated to Zeus the Olympian, described by Pausanias

Pausanias (geographer)

Pausanias was a Greek traveler and geographer of the 2nd century AD, who lived in the times of Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. He is famous for his Description of Greece , a lengthy work that describes ancient Greece from firsthand observations, and is a crucial link between classical...

.

Delian Leagues

When the MedianAchaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire , sometimes known as First Persian Empire and/or Persian Empire, was founded in the 6th century BCE by Cyrus the Great who overthrew the Median confederation...

danger had been beaten back from the territory of continental Greece and combat was taking place in the islands and in Ionia (Asia Minor

Anatolia

Anatolia is a geographic and historical term denoting the westernmost protrusion of Asia, comprising the majority of the Republic of Turkey...

), the Cyclades entered into an alliance that would avenge Greece and pay back the damages caused by the Persians’ pillages of their possessions. This alliance was organised by Athens and is commonly called the first Delian League

Delian League

The Delian League, founded in circa 477 BC, was an association of Greek city-states, members numbering between 150 to 173, under the leadership of Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Persian Empire after the Greek victory in the Battle of Plataea at the end of the Greco–Persian Wars...

. From 478-477 BC, the cities in coalition provided either ships (for example Naxos) or especially a tribute of silver. The amount of treasure owed was fixed at four hundred talents, which were deposited in the sanctuary of Apollo on the sacred island of Delos.

Rather quickly, Athens began to behave in an authoritarian manner toward its allies, before bringing them under its total domination. Naxos revolted in 469 BC and became the first allied city to be transformed into a subject state by Athens, following a siege. The treasury was transferred from Delos to the Acropolis of Athens

Acropolis of Athens

The Acropolis of Athens or Citadel of Athens is the best known acropolis in the world. Although there are many other acropoleis in Greece, the significance of the Acropolis of Athens is such that it is commonly known as The Acropolis without qualification...

around 454 BC. Thus the Cyclades entered the “district” of the islands (along with Imbros

Imbros

Imbros or Imroz, officially referred to as Gökçeada since July 29, 1970 , is an island in the Aegean Sea and the largest island of Turkey, part of Çanakkale Province. It is located at the entrance of Saros Bay and is also the westernmost point of Turkey...

, Lesbos and Skyros

Skyros

Skyros is an island in Greece, the southernmost of the Sporades, an archipelago in the Aegean Sea. Around the 2nd millennium BC and slightly later, the island was known as The Island of the Magnetes where the Magnetes used to live and later Pelasgia and Dolopia and later Skyros...

) and no longer contributed to the League except through installments of silver, the amount of which was set by the Athenian Assembly. The tribute was not too burdensome, except after a revolt, when it was increased as punishment. Apparently, Athenian domination sometimes took the form of cleruchies

Cleruchy

A cleruchy in Hellenic Greece, was a specialized type of colony established by Athens. The term comes from the Greek word , klērouchos, literally "lot-holder"....

(for example on Naxos and Andros).

At the beginning of the Peloponnesian War

Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War, 431 to 404 BC, was an ancient Greek war fought by Athens and its empire against the Peloponnesian League led by Sparta. Historians have traditionally divided the war into three phases...

, all the Cyclades except Milos and Santorini were subjects of Athens. Thus, Thucydides writes that soldiers from Kea, Andros and Tinos participated in the Sicilian Expedition

Sicilian Expedition

The Sicilian Expedition was an Athenian expedition to Sicily from 415 BC to 413 BC, during the Peloponnesian War. The expedition was hampered from the outset by uncertainty in its purpose and command structure—political maneuvering in Athens swelled a lightweight force of twenty ships into a...

and that these islands were “tributary subjects”.

The Cyclades paid a tribute until 404 BC. After that, they experienced a relative period of autonomy before entering the second Delian League and passing under Athenian control once again.

According to Quintus Curtius Rufus

Quintus Curtius Rufus

Quintus Curtius Rufus was a Roman historian, writing probably during the reign of the Emperor Claudius or Vespasian. His only surviving work, Historiae Alexandri Magni, is a biography of Alexander the Great in Latin in ten books, of which the first two are lost, and the remaining eight are...

, after (or at the same time as) the Battle of Issus

Battle of Issus

The Battle of Issus occurred in southern Anatolia, in November 333 BC. The invading troops, led by the young Alexander of Macedonia, defeated the army personally led by Darius III of Achaemenid Persia in the second great battle for primacy in Asia...

, a Persian counter-attack led by Pharnabazus led to an occupation of Andros and Sifnos.

Hellenistic Era

An archipelago disputed among the Hellenistic kingdoms

According to Demosthenes and Diodorus of Siculus, the Thessalian tyrant Alexander of PheraeAlexander of Pherae

Alexander was tagus or despot of Pherae in Thessaly, and ruled from 369 BC to 358 BC.-Reign:The accounts of how he came to power vary somewhat in minor points. Diodorus Siculus tells us that upon the assassination of the tyrant Jason of Pherae, in 370 BC, his brother Polydorus ruled for a year,...

led pirate expeditions in the Cyclades around 362-360 BC. His ships appear to have taken over several ships from the islands, among them Tinos, and brought back a large number of slaves. The Cyclades revolted during the Third Sacred War

Third Sacred War

The Third Sacred War was fought between the forces of the Delphic Amphictyonic League, principally represented by Thebes, and latterly by Philip II of Macedon, and the Phocians...

(357-355 BC), which saw the intervention of Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon "friend" + ἵππος "horse" — transliterated ; 382 – 336 BC), was a king of Macedon from 359 BC until his assassination in 336 BC. He was the father of Alexander the Great and Philip III.-Biography:...

against Phocis

Phocis

Phocis is one of the regional units of Greece. It is part of the administrative region of Central Greece. It stretches from the western mountainsides of Parnassus on the east to the mountain range of Vardousia on the west, upon the Gulf of Corinth...

, allied with Pherae. Thus they began to pass into the orbit of Macedonia.

In their struggle for influence, the leaders of the Hellenistic kingdoms often proclaimed their desire to maintain the “liberty” of the Greek cities, in reality controlled by them and often occupied by garrisons.

Thus in 314 BC, Antigonus I Monophthalmus

Antigonus I Monophthalmus

Antigonus I Monophthalmus , son of Philip from Elimeia, was a Macedonian nobleman, general, and satrap under Alexander the Great. During his early life he served under Philip II, and he was a major figure in the Wars of the Diadochi after Alexander's death, declaring himself king in 306 BC and...

created the Nesiotic League around Tinos and its renowned sanctuary of Poseidon

Poseidon

Poseidon was the god of the sea, and, as "Earth-Shaker," of the earthquakes in Greek mythology. The name of the sea-god Nethuns in Etruscan was adopted in Latin for Neptune in Roman mythology: both were sea gods analogous to Poseidon...

and Amphitrite

Amphitrite

In ancient Greek mythology, Amphitrite was a sea-goddess and wife of Poseidon. Under the influence of the Olympian pantheon, she became merely the consort of Poseidon, and was further diminished by poets to a symbolic representation of the sea...

, less affected by politics than the Apollo’s sanctuary on Delos. Around 308 BC, the Egyptian fleet of Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter

Ptolemy I Soter I , also known as Ptolemy Lagides, c. 367 BC – c. 283 BC, was a Macedonian general under Alexander the Great, who became ruler of Egypt and founder of both the Ptolemaic Kingdom and the Ptolemaic Dynasty...

sailed around the archipelago during an expedition in the Peloponnese and “liberated” Andros. The Nesiotic League would slowly be raised to the level of a federal state in the service of the Antigonids

Antigonid dynasty

The Antigonid dynasty was a dynasty of Hellenistic kings descended from Alexander the Great's general Antigonus I Monophthalmus .-History:...

, and Demetrius I

Demetrius I of Macedon

Demetrius I , called Poliorcetes , son of Antigonus I Monophthalmus and Stratonice, was a king of Macedon...

relied on it during his naval campaigns.

The islands then passed under Ptolemaic

Ptolemaic dynasty

The Ptolemaic dynasty, was a Macedonian Greek royal family which ruled the Ptolemaic Empire in Egypt during the Hellenistic period. Their rule lasted for 275 years, from 305 BC to 30 BC...

domination. During the Chremonidean War

Chremonidean War

The Chremonidean War was fought by a coalition of Greek city-states against Macedonian domination.The origins of the war lie in the continuing desire of many Greek states, most notably Athens and Sparta, for a restoration of their former independence along with the Ptolemaic desire to stir up...

, mercenary garrisons had been set up on certain islands, among them Santorini, Andros and Kea. But, defeated on Andros sometime between 258 and 245 BC, the Ptolemies ceded them to Macedon, then ruled by Antigonus II Gonatas

Antigonus II Gonatas

Antigonus II Gonatas was a powerful ruler who firmly established the Antigonid dynasty in Macedonia and acquired fame for his victory over the Gauls who had invaded the Balkans.-Birth and family:...

. However, because of the revolt of Alexander, son of Craterus

Craterus

Craterus was a Macedonian general under Alexander the Great and one of the Diadochi.He was the son of a Macedonian nobleman named Alexander from Orestis and brother of admiral Amphoterus. Craterus commanded the phalanx and all infantry on the left wing in Battle of Issus...

, the Macedonians were not able to exercise complete control over the archipelago, which entered a period of instability. Antigonus III Doson

Antigonus III Doson

Antigonus III Doson was king of Macedon from 229 BC to 221 BC. He belonged to the Antigonid dynasty.-Family Background:He was a grandson of Demetrius Poliorcetes and cousin of Demetrius II, who after the latter died in battle and rescued Macedonia and restored Antigonid control of Greece...

put the islands under control once again when he attacked Caria

Caria

Caria was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joined the Carian population in forming Greek-dominated states there...

or when he destroyed the Spartan forces at Sellasia

Battle of Sellasia

The Battle of Sellasia took place during the summer of 222 BC between the armies of Macedon and the Achaean League, led by Antigonus III Doson, and Sparta under the command of King Cleomenes III...

in 222 BC. Demetrius of Pharos

Demetrius of Pharos

Demetrius of Pharos was a ruler of Pharos involved in the First Illyrian War, after which he ruled a portion of the Illyrian Adriatic coast on behalf of the Romans, as a Client king....

then ravaged the archipelago and was driven away from it by the Rhodians.

Philip V of Macedon

Philip V of Macedon

Philip V was King of Macedon from 221 BC to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of Rome. Philip was attractive and charismatic as a young man...

, after the Second Punic War

Second Punic War

The Second Punic War, also referred to as The Hannibalic War and The War Against Hannibal, lasted from 218 to 201 BC and involved combatants in the western and eastern Mediterranean. This was the second major war between Carthage and the Roman Republic, with the participation of the Berbers on...

, turned his attention to the Cyclades, which he ordered the Aetolian pirate Dicearchus to ravage before taking control and installing garrisons on Andros, Paros and Kythnos.

After the Battle of Cynoscephalae

Battle of Cynoscephalae

The Battle of Cynoscephalae was an encounter battle fought in Thessaly in 197 BC between the Roman army, led by Titus Quinctius Flamininus, and the Antigonid dynasty of Macedon, led by Philip V.- Prelude :...

, the islands passed to Rhodes

Rhodes

Rhodes is an island in Greece, located in the eastern Aegean Sea. It is the largest of the Dodecanese islands in terms of both land area and population, with a population of 117,007, and also the island group's historical capital. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within...

and then to the Romans. Rhodes would give new momentum to the Nesiotic League.

Hellenistic society

In his work on Tinos, Roland Étienne evokes a society dominated by an agrarian and patriarchal “aristocracy” marked by strong endogamyEndogamy

Endogamy is the practice of marrying within a specific ethnic group, class, or social group, rejecting others on such basis as being unsuitable for marriage or other close personal relationships. A Greek Orthodox Christian endogamist, for example, would require that a marriage be only with another...

. These few families had many children and derived part of their resources from a financial exploitation of the land (sales, rents, etc.), characterised by Étienne as “rural racketeering”. This “real estate market” was dynamic due to the number of heirs and the division of inheritances at the time they were handed down. Only the purchase and sale of land could build up coherent holdings. Part of these financial resources could also be invested in commercial activities.

This endogamy might take place at the level of social class, but also at that of the entire body of citizens. It is known that the inhabitants of Delos, although living in a city with numerous foreigners—who sometimes outnumbered citizens—practiced a very strong form of civic endogamy throughout the Hellenistic period. Although it is not possible to say whether this phenomenon occurred systematically in all the Cyclades, Delos remains a good indicator of how society may have functioned on the other islands. In fact, populations circulated more widely in the Hellenistic period than in previous eras: of 128 soldiers quartered in the garrison at Santorini by the Ptolemies, the great majority came from Asia Minor; at the end of the 1st century BC, Milos had a large Jewish population. Whether the status of citizen should be maintained was debated.

The Hellenistic era left an imposing legacy for certain of the Cyclades: towers in large numbers—on Amorgos; on Sifnos, where 66 were counted in 1991; and on Kea, where 27 were identified in 1956. Not all could have been observation towers, as is often conjectured. Then great number of them on Sifnos was associated with the island’s mineral riches, but this quality did not exist on Kea or Amorgos, which instead had other resources, such as agricultural products. Thus the towers appear to have reflected the islands’ prosperity during the Hellenistic era.

The commercial power of Delos

Corinth

Corinth is a city and former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Corinth, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit...

. Foreign merchants from throughout the Mediterranean set up business there, as indicated by the terrace of foreign gods. Additionally, a synagogue is attested on Delos as of the middle of the 2nd century BC. It is estimated that in the 2nd century BC, Delos had a population of about 25,000.

The notorious “agora of the Italians” was an immense slave market. The wars between Hellenistic kingdoms were the main source of slaves, as well as pirates (who assumed the status of merchants when entering the port of Delos). When Strabo

Strabo

Strabo, also written Strabon was a Greek historian, geographer and philosopher.-Life:Strabo was born to an affluent family from Amaseia in Pontus , a city which he said was situated the approximate equivalent of 75 km from the Black Sea...

(XIV, 5, 2) refers to ten thousand slaves being sold each day, it is necessary to add nuance to this claim, as the number could be the author’s way of saying “many”. Moreover, a number of these “slaves” were sometimes prisoners of war (or people kidnapped by pirates) whose ransom was immediately paid upon disembarking.

This prosperity provoked jealousy and new forms of “economic exchanges”: in 298 BC, Delos transferred at least 5,000 drachmae

Greek drachma

Drachma, pl. drachmas or drachmae was the currency used in Greece during several periods in its history:...

to Rhodes for its “protection against pirates”; in the middle of the 2nd century BC, Aetolian pirates launched an appeal for bids to the Aegean world to negotiate the fee to be paid in exchange for protection against their exactions.

The Cyclades in Rome’s orbit

The reasons for Rome’s intervention in Greece from the 3rd century BC are many: a call for help from the cities of IllyriaIllyria

In classical antiquity, Illyria was a region in the western part of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by the Illyrians....

; the fight against Philip V of Macedon

Philip V of Macedon

Philip V was King of Macedon from 221 BC to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by an unsuccessful struggle with the emerging power of Rome. Philip was attractive and charismatic as a young man...

, whose naval policy troubled Rome and who had been an ally of Hannibal’s; or assistance to Macedon’s adversaries in the region (Pergamon

Pergamon

Pergamon , or Pergamum, was an ancient Greek city in modern-day Turkey, in Mysia, today located from the Aegean Sea on a promontory on the north side of the river Caicus , that became the capital of the Kingdom of Pergamon during the Hellenistic period, under the Attalid dynasty, 281–133 BC...

, Rhodes

Rhodes

Rhodes is an island in Greece, located in the eastern Aegean Sea. It is the largest of the Dodecanese islands in terms of both land area and population, with a population of 117,007, and also the island group's historical capital. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within...

and the Achaean League

Achaean League

The Achaean League was a Hellenistic era confederation of Greek city states on the northern and central Peloponnese, which existed between 280 BC and 146 BC...

). After his victory at Battle of Cynoscephalae

Battle of Cynoscephalae

The Battle of Cynoscephalae was an encounter battle fought in Thessaly in 197 BC between the Roman army, led by Titus Quinctius Flamininus, and the Antigonid dynasty of Macedon, led by Philip V.- Prelude :...

, Flaminius

Titus Quinctius Flamininus

Titus Quinctius Flamininus was a Roman politician and general instrumental in the Roman conquest of Greece.Member of the gens Quinctia, and brother to Lucius Quinctius Flamininus, he served as a military tribune in the Second Punic war and in 205 BC he was appointed propraetor in Tarentum...

proclaimed the “liberation” of Greece. Neither were commercial interests absent as a factor in Rome’s involvement. Delos became a free port under the Roman Republic’s protection in 167 BC. Thus Italian merchants grew wealthier, more or less at the expense of Rhodes and Corinth (finally destroyed the same year as Carthage). The political system of the Greek city, on the continent and on the islands, was maintained, indeed developed, during the 1st centuries of the Empire

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire was the post-Republican period of the ancient Roman civilization, characterised by an autocratic form of government and large territorial holdings in Europe and around the Mediterranean....

.

According to certain historians, the Cyclades were included in the Roman province of Asia around 133-129 BC; others place them in the province of Achaea

Achaea (Roman province)

Achaea, or Achaia, was a province of the Roman Empire, consisting of the Peloponnese, eastern Central Greece and parts of Thessaly. It bordered on the north by the provinces of Epirus vetus and Macedonia...

; at least, they were not divided between these two provinces. Definitive proof does not place the Cyclades in the province of Asia until the time of Vespasian

Vespasian

Vespasian , was Roman Emperor from 69 AD to 79 AD. Vespasian was the founder of the Flavian dynasty, which ruled the Empire for a quarter century. Vespasian was descended from a family of equestrians, who rose into the senatorial rank under the Emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty...

and Domitian

Domitian

Domitian was Roman Emperor from 81 to 96. Domitian was the third and last emperor of the Flavian dynasty.Domitian's youth and early career were largely spent in the shadow of his brother Titus, who gained military renown during the First Jewish-Roman War...

.

In 88 BC, Mithridates

Mithridates VI of Pontus

Mithridates VI or Mithradates VI Mithradates , from Old Persian Mithradatha, "gift of Mithra"; 134 BC – 63 BC, also known as Mithradates the Great and Eupator Dionysius, was king of Pontus and Armenia Minor in northern Anatolia from about 120 BC to 63 BC...

, after expelling the Romans from Asia, took an interest in the Aegean. His general Archelaus

Archelaus (general)

Archelaus was a leading military general of the King Mithridates VI of Pontus. Archelaus was the greatest general that had served under Mithridates VI and was also his favorite general....

took Delos and most of the Cyclades, which he entrusted to Athens, which had declared itself in favour of Mithridates. Delos managed to return to the Roman fold. As a punishment, the island was devastated by Mithridates’ troops. Twenty years later, it was destroyed once again, raided by pirates taking advantage of regional instability. The Cyclades then experienced a difficult period. The defeat of Mithridates by Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix , known commonly as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He had the rare distinction of holding the office of consul twice, as well as that of dictator...

, Lucullus

Lucullus

Lucius Licinius Lucullus , was an optimate politician of the late Roman Republic, closely connected with Sulla Felix...

and then Pompey

Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, also known as Pompey or Pompey the Great , was a military and political leader of the late Roman Republic...

returned the archipelago to Rome. In 67 BC, Pompey caused piracy, which had arisen during various conflicts, to disappear from the region. He divided the Mediterranean into different sectors led by lieutenants. Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus

Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus

Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus , younger brother of the more famous Lucius Licinius Lucullus, was a supporter of Lucius Cornelius Sulla and consul of ancient Rome in 73 BC. As proconsul of Macedonia in 72 BC, he defeated the Bessi in Thrace and advanced to the Danube and the west coast of the...

was put in charge of the Cyclades. Thus, Pompey brought back the possibility of a prosperous trade for the archipelago. However, it appears that a high cost of living, social inequalities and the concentration of wealth (and power) were the rule for the Cyclades during the Roman era, with their stream of abuse and discontentment.

Augustus

Augustus

Augustus ;23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14) is considered the first emperor of the Roman Empire, which he ruled alone from 27 BC until his death in 14 AD.The dates of his rule are contemporary dates; Augustus lived under two calendars, the Roman Republican until 45 BC, and the Julian...

, having decided that those whom he exiled could only reside on islands more than 400 stadia

Stadion (unit of length)

The stadion, Latinized as stadium and anglicized as stade, is an ancient Greek unit of length. According to Herodotus, one stade is equal to 600 feet. However, there were several different lengths of “feet”, depending on the country of origin....

(50 km) from the continent, the Cyclades became places of exile, chiefly Gyaros, Amorgos and Serifos.

Vespasian organised the Cycladic archipelago into a Roman province. Under Diocletian

Diocletian

Diocletian |latinized]] upon his accession to Diocletian . c. 22 December 244 – 3 December 311), was a Roman Emperor from 284 to 305....

, there existed a “province of the islands” that included the Cyclades.

Christianisation

Christianization

The historical phenomenon of Christianization is the conversion of individuals to Christianity or the conversion of entire peoples at once...

seems to have occurred very early in the Cyclades. The catacombs at Trypiti on Milos, unique in the Aegean and in Greece, of very simple workmanship, as well as the very close baptismal fonts, confirms that a Christian community existed on the island at least from the 3rd or 4th century AD.

From the 4th century, the Cyclades again experienced the ravages of war. In 376, the Goths

Goths

The Goths were an East Germanic tribe of Scandinavian origin whose two branches, the Visigoths and the Ostrogoths, played an important role in the fall of the Roman Empire and the emergence of Medieval Europe....

pillaged the archipelago.

Administrative organisation

When the Roman Empire was divided, control over the Cyclades passed to the Byzantine EmpireByzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire was the Eastern Roman Empire during the periods of Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, centred on the capital of Constantinople. Known simply as the Roman Empire or Romania to its inhabitants and neighbours, the Empire was the direct continuation of the Ancient Roman State...

, which retained them until the 13th century.

At first, administrative organisation was based on small provinces. During the rule of Justinian I

Justinian I

Justinian I ; , ; 483– 13 or 14 November 565), commonly known as Justinian the Great, was Byzantine Emperor from 527 to 565. During his reign, Justinian sought to revive the Empire's greatness and reconquer the lost western half of the classical Roman Empire.One of the most important figures of...

, the Cyclades, Cyprus

Cyprus

Cyprus , officially the Republic of Cyprus , is a Eurasian island country, member of the European Union, in the Eastern Mediterranean, east of Greece, south of Turkey, west of Syria and north of Egypt. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.The earliest known human activity on the...

and Caria

Caria

Caria was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia south to Lycia and east to Phrygia. The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joined the Carian population in forming Greek-dominated states there...

, together with Moesia Secunda

Moesia

Moesia was an ancient region and later Roman province situated in the Balkans, along the south bank of the Danube River. It included territories of modern-day Southern Serbia , Northern Republic of Macedonia, Northern Bulgaria, Romanian Dobrudja, Southern Moldova, and Budjak .-History:In ancient...

(present-day Bulgaria

Bulgaria

Bulgaria , officially the Republic of Bulgaria , is a parliamentary democracy within a unitary constitutional republic in Southeast Europe. The country borders Romania to the north, Serbia and Macedonia to the west, Greece and Turkey to the south, as well as the Black Sea to the east...

) and Scythia

Scythia

In antiquity, Scythian or Scyths were terms used by the Greeks to refer to certain Iranian groups of horse-riding nomadic pastoralists who dwelt on the Pontic-Caspian steppe...

(the portion now in Bessarabia

Bessarabia

Bessarabia is a historical term for the geographic region in Eastern Europe bounded by the Dniester River on the east and the Prut River on the west....

), were brought together under the authority of a Quaestor set up at Odessus (now Varna

Varna

Varna is the largest city and seaside resort on the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast and third-largest in Bulgaria after Sofia and Plovdiv, with a population of 334,870 inhabitants according to Census 2011...

). Little by little, themes were put into place, starting with the reign of Heraclius

Heraclius

Heraclius was Byzantine Emperor from 610 to 641.He was responsible for introducing Greek as the empire's official language. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Africa, successfully led a revolt against the unpopular usurper Phocas.Heraclius'...

at the beginning of the 7th century. In the 10th century an Aegean theme (tò théma toû Aiyaíou Pelágous) headed by an admiral (dhrungarios) was established; it included the Cyclades, the Sporades

Sporades

The Sporades are an archipelago along the east coast of Greece, northeast of the island of Euboea, in the Aegean Sea. It consists of 24 islands, of which four are permanently inhabited: Alonnisos, Skiathos, Skopelos and Skyros.-Administration:...

, Chios

Chios

Chios is the fifth largest of the Greek islands, situated in the Aegean Sea, seven kilometres off the Asia Minor coast. The island is separated from Turkey by the Chios Strait. The island is noted for its strong merchant shipping community, its unique mastic gum and its medieval villages...

, Lesbos and Lemnos

Lemnos

Lemnos is an island of Greece in the northern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos peripheral unit, which is part of the North Aegean Periphery. The principal town of the island and seat of the municipality is Myrina...

. In fact, the Aegean theme rather than an army supplied sailors to the imperial navy. It seems that later on, central government control over the little isolated entities that were the islands slowly diminished: defence and tax collection became increasingly difficult. At the beginning of the 12th century, they had become impossible; Constantinople

Constantinople

Constantinople was the capital of the Roman, Eastern Roman, Byzantine, Latin, and Ottoman Empires. Throughout most of the Middle Ages, Constantinople was Europe's largest and wealthiest city.-Names:...

had thus given up on maintaining them.

Conflicts and migrations among the islands

In 727, the islands revolted against the iconoclastic Emperor Leo the IsaurianLeo III the Isaurian

Leo III the Isaurian or the Syrian , was Byzantine emperor from 717 until his death in 741...

. Cosmas, placed at the head of the rebellion, was proclaimed emperor, but perished during the siege of Constantinople. Leo brutally re-established his authority over the Cyclades by sending a fleet that used Greek fire

Greek fire

Greek fire was an incendiary weapon used by the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantines typically used it in naval battles to great effect as it could continue burning while floating on water....

.

In 769, the islands were devastated by the Slavs

Slavic peoples

The Slavic people are an Indo-European panethnicity living in Eastern Europe, Southeast Europe, North Asia and Central Asia. The term Slavic represents a broad ethno-linguistic group of people, who speak languages belonging to the Slavic language family and share, to varying degrees, certain...

.

At the beginning of the 9th century, the Saracen

Saracen

Saracen was a term used by the ancient Romans to refer to a people who lived in desert areas in and around the Roman province of Arabia, and who were distinguished from Arabs. In Europe during the Middle Ages the term was expanded to include Arabs, and then all who professed the religion of Islam...

s, who controlled Crete from 829, threatened the Cyclades and sent raids there for more than a century. Naxos had to pay them a tribute (phoroi). The islands were therefore partly depopulated: the Life of Saint Theoktistus of Lesbos says that Paros was deserted in the 9th century and that one only encountered hunters there. The Saracen pirates of Crete, having taken it during a raid on Lesbos in 837, would stop at Paros on the return journey and there attempt to pillage the church of Panaghia Ekatontopiliani; Nicetas, in the service of Leo VI the Wise

Leo VI the Wise

Leo VI, surnamed the Wise or the Philosopher , was Byzantine emperor from 886 to 912. The second ruler of the Macedonian dynasty , he was very well-read, leading to his surname...

, recorded the damages. In 904, Andros, Naxos and others of the Cyclades were pillaged by an Arab fleet returning from Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki , historically also known as Thessalonica, Salonika or Salonica, is the second-largest city in Greece and the capital of the region of Central Macedonia as well as the capital of the Decentralized Administration of Macedonia and Thrace...

, which it had just sacked.

It was during this period of the Byzantine Empire that the villages left the edge of the sea to higher ground in the mountains: Lefkes rather than Paroikia on Paros or the plateau of Traghea on Naxos. This movement, due to a danger at the base, also had positive effects. On the largest islands, the interior plains were fertile and suitable for new development. Thus it was during the 11th century, when Paleopoli was abandoned in favour of the plain of Messaria on Andros, that the breeding of silkworms

Bombyx mori

The silkworm is the larva or caterpillar of the domesticated silkmoth, Bombyx mori . It is an economically important insect, being a primary producer of silk...

, which ensured the island’s wealth until the 19th century, was introduced.

Duchy of Naxos

Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade was originally intended to conquer Muslim-controlled Jerusalem by means of an invasion through Egypt. Instead, in April 1204, the Crusaders of Western Europe invaded and conquered the Christian city of Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman Empire...

took Constantinople, and the conquerors divided the Byzantine Empire amongst themselves. Nominal sovereignty over the Cyclades fell to the Venetians

Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice or Venetian Republic was a state originating from the city of Venice in Northeastern Italy. It existed for over a millennium, from the late 7th century until 1797. It was formally known as the Most Serene Republic of Venice and is often referred to as La Serenissima, in...

, who announced that they would leave the islands’ administration to whoever was capable of managing it on their behalf. In effect, the Most Serene Republic was unable to handle the expense of a new expedition. This piece of news stirred excitement. Numerous adventurers armed fleets at their own expense, among them a wealthy Venetian residing in Constantinople, Marco Sanudo, nephew of the Doge

Doge of Venice

The Doge of Venice , often mistranslated Duke was the chief magistrate and leader of the Most Serene Republic of Venice for over a thousand years. Doges of Venice were elected for life by the city-state's aristocracy. Commonly the person selected as Doge was the shrewdest elder in the city...

Enrico Dandolo

Enrico Dandolo

Enrico Dandolo — anglicised as Henry Dandolo and Latinized as Henricus Dandulus — was the 41st Doge of Venice from 1195 until his death...

. Without any difficulty, he took Naxos in 1205 and by 1207, he controlled the Cyclades, together with his comrades and relatives. His cousin Marino Dandolo became lord of Andros; other relatives, the brothers Andrea and Geremia Ghisi (or Ghizzi) became masters of Tinos and Mykonos, and had fiefs on Kea and Serifos; the Pisani family took Kea; Santorini went to Jaccopo Barozzi; Leonardo Foscolo received Anafi; Pietro Guistianini and Domenico Michieli shared Serifos and held fiefs on Kea; the Quirini family governed Amorgos. Marco Sanudo founded the Duchy of Naxos

Duchy of the Archipelago

The Duchy of the Archipelago or also Duchy of Naxos or Duchy of the Aegean was a maritime state created by Venetian interests in the Cyclades archipelago in the Aegean Sea, in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade, centered on the islands of Naxos and Paros.-Background and establishment of the...

with the main islands such as Naxos, Paros, Antiparos, Milos, Sifnos, Kythnos and Syros. The Dukes of Naxos became vassals of the Latin Emperor of Constantinople

Latin Empire