Miltiades the Younger

Encyclopedia

Aeacidae

Aeacidae refers to the descendants of Aeacus, most notably Peleus, son of Aeacus, and Achilles, grandson of Aeacus. Neoptolemus was the son of Achilles and the princess Deidamea. The kings of Epirus and Olympias, mother to Alexander the Great, claimed to be members of this lineage.Aeacus of Greek...

, and is known mostly for his role in the Battle of Marathon

Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC, during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. It was the culmination of the first attempt by Persia, under King Darius I, to subjugate...

; as well as his rather tragic downfall

Downfall

Downfall is a rapid deterioration, as in status or wealth. It may also refer to:- Film and television :* Downfall , 2004 German film about the last days of Adolf Hitler* Downfall, a Korean movie starring Shin Eun-gyeong...

afterwards. His son Cimon was a major Athenian figure of the 470s and 460s BCE. His daughter Elpinice

Elpinice

Elpinice was a noble woman of classical Athens.She was the daughter of Miltiades, tyrant of the Greek colonies on the Thracian Chersonese, and half sister of Cimon, an important Athenian political figure...

is remembered for her confrontations with Pericles

Pericles

Pericles was a prominent and influential statesman, orator, and general of Athens during the city's Golden Age—specifically, the time between the Persian and Peloponnesian wars...

, as recorded by Plutarch

Plutarch

Plutarch then named, on his becoming a Roman citizen, Lucius Mestrius Plutarchus , c. 46 – 120 AD, was a Greek historian, biographer, essayist, and Middle Platonist known primarily for his Parallel Lives and Moralia...

.

Thracian Chersonese

Miltiades made himself the tyrantTyrant

A tyrant was originally one who illegally seized and controlled a governmental power in a polis. Tyrants were a group of individuals who took over many Greek poleis during the uprising of the middle classes in the sixth and seventh centuries BC, ousting the aristocratic governments.Plato and...

of the Greek

Greeks

The Greeks, also known as the Hellenes , are a nation and ethnic group native to Greece, Cyprus and neighboring regions. They also form a significant diaspora, with Greek communities established around the world....

colonies on the Thracian Chersonese

Thracian Chersonese

The Thracian Chersonese was the ancient name of the Gallipoli peninsula, in the part of historic Thrace that is now part of modern Turkey.The peninsula runs in a south-westerly direction into the Aegean Sea, between the Hellespont and the bay of Melas . Near Agora it was protected by a wall...

, forcibly seizing it from his rivals and imprisoning them. His step-uncle Miltiades the Elder

Miltiades the Elder

Miltiades the Elder was a member of an immensely wealthy Athenian noble family, the Philaids. He is said to have opposed the tyrant Peisistratus, which may explain why he left Athens around 550 BC to found a colony in the Thracian Chersonese . The colony was semi-independent of Athens and was...

, and his brother Stesagoras, had been the ruler before him. When Stesagoras had died, Miltiades was sent to rule the Chersonese, around 482 BCE. His brother's reign had been tumultuous, full of war

War

War is a state of organized, armed, and often prolonged conflict carried on between states, nations, or other parties typified by extreme aggression, social disruption, and usually high mortality. War should be understood as an actual, intentional and widespread armed conflict between political...

and revolt. Wishing for a tighter reign than his brother, he feigned mourning

Mourning

Mourning is, in the simplest sense, synonymous with grief over the death of someone. The word is also used to describe a cultural complex of behaviours in which the bereaved participate or are expected to participate...

for his brother's death. When men of rank from the Chersonese came to console him, he imprisoned them. He then assured his power by taking in 500 troops. He also married Hegesipyle, the daughter of king Olorus

Olorus

Olorus was the name of a king of Thrace. His daughter Hegesipyle married the Athenian statesman and general Miltiades, who defeated the Persians at the battle of Marathon in 490 BC. Olorus was also the name of the father of the 5th century BC Athenian historian Thucydides, the author of the History...

of Thrace

Thrace

Thrace is a historical and geographic area in southeast Europe. As a geographical concept, Thrace designates a region bounded by the Balkan Mountains on the north, Rhodope Mountains and the Aegean Sea on the south, and by the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara on the east...

.

Thracian Chersonese was forced to submit to Persian

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire , sometimes known as First Persian Empire and/or Persian Empire, was founded in the 6th century BCE by Cyrus the Great who overthrew the Median confederation...

rule. Miltiades became a vassal

Vassal

A vassal or feudatory is a person who has entered into a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. The obligations often included military support and mutual protection, in exchange for certain privileges, usually including the grant of land held...

of Darius I

Darius I of Persia

Darius I , also known as Darius the Great, was the third king of kings of the Achaemenid Empire...

of Persia, joining Darius' expedition against the Scythians around 513 BCE. Miltiades had suggested destroying the bridge across the Danube

Danube

The Danube is a river in the Central Europe and the Europe's second longest river after the Volga. It is classified as an international waterway....

which Darius used to cross into Scythia

Scythia

In antiquity, Scythian or Scyths were terms used by the Greeks to refer to certain Iranian groups of horse-riding nomadic pastoralists who dwelt on the Pontic-Caspian steppe...

, leaving Darius to die. The others were afraid to do this, and so it never happened, but Darius was aware of Miltiades' scheming; and so his rule in the Chersonese was a perilous affair since this point. He joined the Ionian Revolt

Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 BC to 493 BC...

of 499 BCE against Persian rule, establishing friendly relations with Athens and capturing the islands of Lemnos

Lemnos

Lemnos is an island of Greece in the northern part of the Aegean Sea. Administratively the island forms a separate municipality within the Lemnos peripheral unit, which is part of the North Aegean Periphery. The principal town of the island and seat of the municipality is Myrina...

and Imbros

Imbros

Imbros or Imroz, officially referred to as Gökçeada since July 29, 1970 , is an island in the Aegean Sea and the largest island of Turkey, part of Çanakkale Province. It is located at the entrance of Saros Bay and is also the westernmost point of Turkey...

, which he eventually ceded to Athens, who had ancient claims to these lands. However, the revolt collapsed in 494 BCE and in 492 BCE Miltiades fled to Athens to escape a retaliatory Persian invasion. His son Metiochos was captured by the Persian fleet

Fleet

-Vehicles:A fleet is a collection of ships or vehicles, with many specific connotations:*Fleet vehicles, two or more vehicles*Fishing fleet*Naval fleet, substantial group of warships*A group of small ships or flotilla...

and made a lifelong prisoner, but was nonetheless treated honorably as a de facto

De facto

De facto is a Latin expression that means "concerning fact." In law, it often means "in practice but not necessarily ordained by law" or "in practice or actuality, but not officially established." It is commonly used in contrast to de jure when referring to matters of law, governance, or...

member of the Persian nobility. Arriving in Athens, Miltiades initially faced a hostile reception for his tyrannical rule in the Thracian Chersonese. Having spent three years in prison he was sentenced to death for the crime of tyranny. However, he successfully presented himself as a defender of Greek freedom

Freedom

-Philosophy:* Free will, the ability to make choices* Political freedom, in the context of the relationship of the individual to the state* Economic freedom-Computing:...

s against Persian despotism

Despotism

Despotism is a form of government in which a single entity rules with absolute power. That entity may be an individual, as in an autocracy, or it may be a group, as in an oligarchy...

and escaped punishment.

Battle of Marathon

Battle of Marathon

The Battle of Marathon took place in 490 BC, during the first Persian invasion of Greece. It was fought between the citizens of Athens, aided by Plataea, and a Persian force commanded by Datis and Artaphernes. It was the culmination of the first attempt by Persia, under King Darius I, to subjugate...

. Miltiades was elected to serve as one of the ten generals (strategoi

Strategos

Strategos, plural strategoi, is used in Greek to mean "general". In the Hellenistic and Byzantine Empires the term was also used to describe a military governor...

) for 490 BCE. In addition to the ten generals, there was one 'war-ruler' (polemarch

Polemarch

A polemarch was a senior military title in various ancient Greek city states . The title is composed out of the polemos and archon and translates as "warleader" or "warlord", one of the nine archontes appointed annually in Athens...

), Callimachus

Callimachus

Callimachus was a native of the Greek colony of Cyrene, Libya. He was a noted poet, critic and scholar at the Library of Alexandria and enjoyed the patronage of the Egyptian–Greek Pharaohs Ptolemy II Philadelphus and Ptolemy III Euergetes...

, who had been left with a decision of great importance. The ten generals were split, five to five, on whether to attack the Persians at Marathon

Marathon, Greece

Marathon is a town in Greece, the site of the battle of Marathon in 490 BC, in which the heavily outnumbered Athenian army defeated the Persians. The tumulus or burial mound for the 192 Athenian dead that was erected near the battlefield remains a feature of the coastal plain...

now, or later. Miltiades was firm in insisting now, and convinced this decisive vote of Callimachus for the necessity of a swift attack.

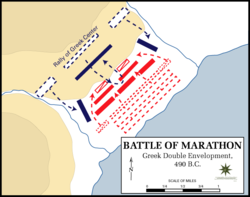

He also convinced the generals of the necessity of not using the customary tactics, as hoplites usually marched in an evenly distributed phalanx

Phalanx formation

The phalanx is a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar weapons...

of shields

Shields

-United Kingdom:* North Shields, Tyneside, England* South Shields, Tyneside, England* Shields Road subway station, an underground station in Glasgow, Scotland-United States:* Shields, Indiana, an unincorporated community...

and spears, a standard with no other instance of deviation until Epaminondas

Epaminondas

Epaminondas , or Epameinondas, was a Theban general and statesman of the 4th century BC who transformed the Ancient Greek city-state of Thebes, leading it out of Spartan subjugation into a preeminent position in Greek politics...

. Miltiades feared the cavalry

Cavalry

Cavalry or horsemen were soldiers or warriors who fought mounted on horseback. Cavalry were historically the third oldest and the most mobile of the combat arms...

of the Persians attacking the flanks, and asked for the flanks to have more hoplites than the center. Miltiades also had his men run, something like a mile

Mile

A mile is a unit of length, most commonly 5,280 feet . The mile of 5,280 feet is sometimes called the statute mile or land mile to distinguish it from the nautical mile...

, in full armor to resist any swift attack of the Persians. This was very successful in defeating the Persians, who then tried to sail around the Cape Sounion and attack Attica

Attica

Attica is a historical region of Greece, containing Athens, the current capital of Greece. The historical region is centered on the Attic peninsula, which projects into the Aegean Sea...

from the west. Miltiades got his men to quickly run to the western side of Attica overnight, causing Datis

Datis

For other uses of the word Dati, see Dati .Datis or Datus was a Median admiral who served the Persian Empire, under Darius the Great...

to flee at the sight of the soldiers who had just defeated him the previous evening.

Expedition at Paros

The following year, 489 BCE, Miltiades led an Athenian expedition of seventy ships against the Greek-inhabited islands that were deemed to have supported the Persians. The expedition was not a success. His true motivations were to attack ParosParos

Paros is an island of Greece in the central Aegean Sea. One of the Cyclades island group, it lies to the west of Naxos, from which it is separated by a channel about wide. It lies approximately south-east of Piraeus. The Municipality of Paros includes numerous uninhabited offshore islets...

, feeling he had been slighted by them in the past. The fleet attacked the island, which had been conquered by the Persians, but failed to take it. Miltiades suffered a bad leg wound during the campaign and became incapacitated. His failure prompted an outcry on his return to Athens

Athens

Athens , is the capital and largest city of Greece. Athens dominates the Attica region and is one of the world's oldest cities, as its recorded history spans around 3,400 years. Classical Athens was a powerful city-state...

, enabling his political rivals to exploit his fall from grace. Charged with treason

Treason

In law, treason is the crime that covers some of the more extreme acts against one's sovereign or nation. Historically, treason also covered the murder of specific social superiors, such as the murder of a husband by his wife. Treason against the king was known as high treason and treason against a...

, he was sentenced to death, but the sentence was converted to a fine of fifty talents

Talent (weight)

The "talent" was one of several ancient units of mass, as well as corresponding units of value equivalent to these masses of a precious metal. It was approximately the mass of water required to fill an amphora. A Greek, or Attic talent, was , a Roman talent was , an Egyptian talent was , and a...

. He was sent to prison where he died, probably of gangrene

Gangrene

Gangrene is a serious and potentially life-threatening condition that arises when a considerable mass of body tissue dies . This may occur after an injury or infection, or in people suffering from any chronic health problem affecting blood circulation. The primary cause of gangrene is reduced blood...

from his wound. The debt was paid by his son Cimon. Pheidias later erected a statue

Statue

A statue is a sculpture in the round representing a person or persons, an animal, an idea or an event, normally full-length, as opposed to a bust, and at least close to life-size, or larger...

in Miltiades' honor of Nemesis

Nemesis (mythology)

In Greek mythology, Nemesis , also called Rhamnousia/Rhamnusia at her sanctuary at Rhamnous, north of Marathon, was the spirit of divine retribution against those who succumb to hubris . The Greeks personified vengeful fate as a remorseless goddess: the goddess of revenge...

, the deity

Deity

A deity is a recognized preternatural or supernatural immortal being, who may be thought of as holy, divine, or sacred, held in high regard, and respected by believers....

whose job it was to bring sudden misfortune to those who had experienced an excess of fortune, in the temple of the goddess at Rhamnus

Rhamnous

The site of Rhamnous , the remote northernmost deme of Attica, lies 39 km NE of Athens and 12.4 km NNE of Marathon, Greece overlooking the Euboean Strait. Rhamnous was strategically significant enough to be fortified and receive an Athenian garrison of ephebes...

. The statue was said to be made of marble provided by Datis for a memorial

Memorial

A memorial is an object which serves as a focus for memory of something, usually a person or an event. Popular forms of memorials include landmark objects or art objects such as sculptures, statues or fountains, and even entire parks....

to the Persians' expected victory.

Sources

- Creasy, Edward Shepherd. The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World: from Marathon to Waterloo. New York: Crowell, 1880. ISBN 1-60-620952-3

- Hammond, N.G.L., Scullard, H.H. eds. Oxford Classical Dictionary, Second Edition; Oxford University Press 1970; ISBN 0-19-869117-3

- HerodotusHerodotusHerodotus was an ancient Greek historian who was born in Halicarnassus, Caria and lived in the 5th century BC . He has been called the "Father of History", and was the first historian known to collect his materials systematically, test their accuracy to a certain extent and arrange them in a...

Histories ISBN 0-19-282425-2

External links

- Photo essay of Miltiades helmet

- Livius, Miltiades by Jona Lendering.